Philosophy in Malta on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Philosophy in Malta refers to the philosophy of Maltese nationals or those of Maltese descent, whether living in

Philosophy in Malta refers to the philosophy of Maltese nationals or those of Maltese descent, whether living in

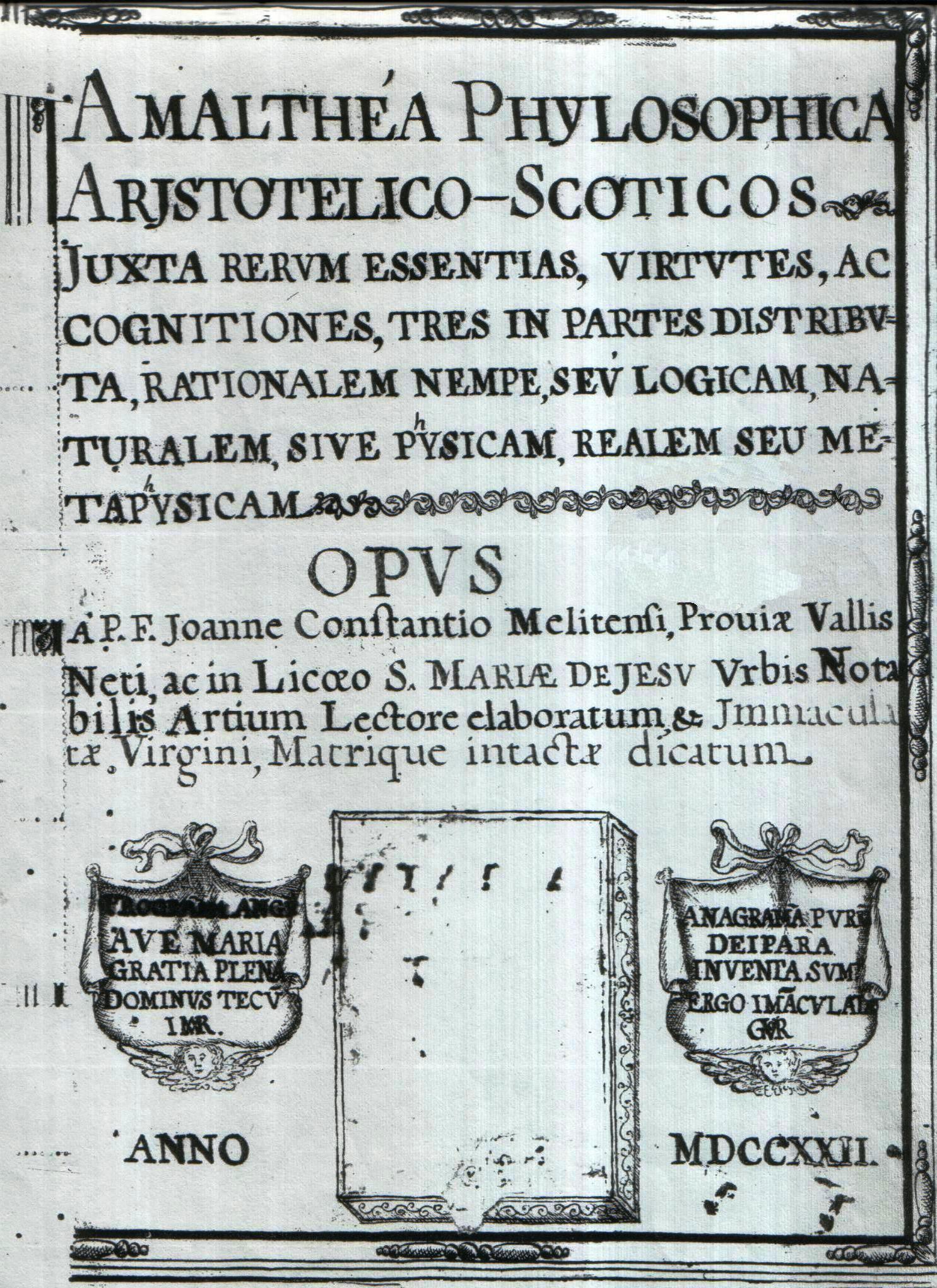

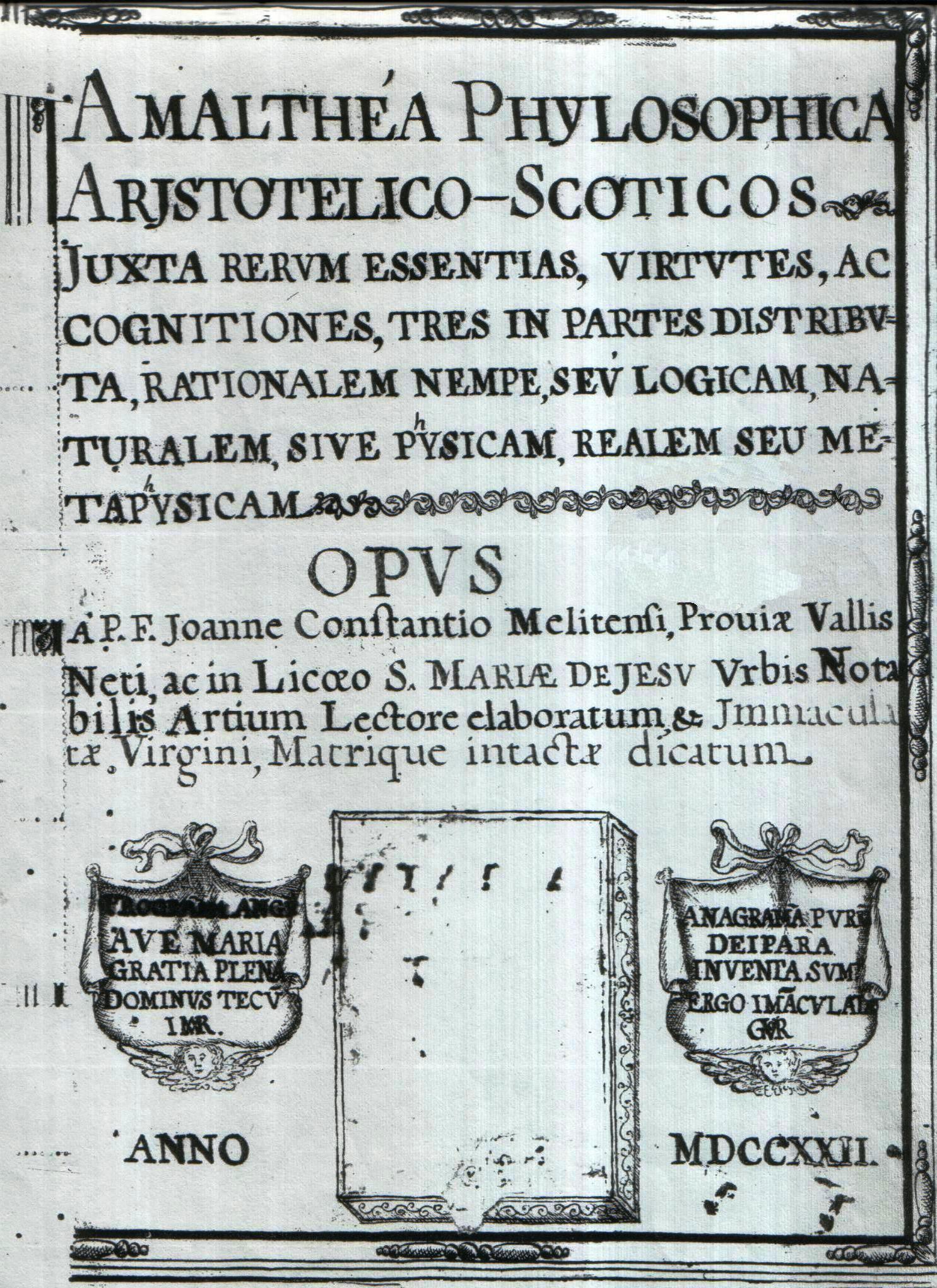

Though philosophy continued to be mainly viewed as the ''hand-maid'' of theology, some intellectuals had an interest in cautiously branching out along some pathways of their own. Though the philosophical contributions of these masters are fascinating in themselves, prevalent control and restrictions on intellectual activity hardly ever left them room for originality and innovation.

During this period intellectual circles were practically all part of the great movement of Scholasticism, almost giving godlike status to

Though philosophy continued to be mainly viewed as the ''hand-maid'' of theology, some intellectuals had an interest in cautiously branching out along some pathways of their own. Though the philosophical contributions of these masters are fascinating in themselves, prevalent control and restrictions on intellectual activity hardly ever left them room for originality and innovation.

During this period intellectual circles were practically all part of the great movement of Scholasticism, almost giving godlike status to

Most of the other philosophers became somewhat more adventurous, exploring spheres which were to some extent inaccessible during the British (and much less the Hospitaller) period. In terms of the development of doing philosophy in Malta, Peter Serracino Inglott stands out as all-important, especially from the late 1960s onwards.

Some other Maltese philosophers worked abroad. Though they retained their limited contact with Malta, they of course had a different frame of mind. Their influence on young Maltese philosophers was negligible.

Most of the other philosophers became somewhat more adventurous, exploring spheres which were to some extent inaccessible during the British (and much less the Hospitaller) period. In terms of the development of doing philosophy in Malta, Peter Serracino Inglott stands out as all-important, especially from the late 1960s onwards.

Some other Maltese philosophers worked abroad. Though they retained their limited contact with Malta, they of course had a different frame of mind. Their influence on young Maltese philosophers was negligible.

Since the 16th century, philosophy has contributed to the academic and, sometimes, the intellectual and cultural life of Maltese intelligentsia. In most cases it functioned as a tool of the establishment—including the

Since the 16th century, philosophy has contributed to the academic and, sometimes, the intellectual and cultural life of Maltese intelligentsia. In most cases it functioned as a tool of the establishment—including the

15th century

:* Peter Caxaro (''c.'' 1400–1485)

17th century

:* Maximilian Balzan (1637–1711)

:* John Matthew Rispoli (1582–1639)

:*

15th century

:* Peter Caxaro (''c.'' 1400–1485)

17th century

:* Maximilian Balzan (1637–1711)

:* John Matthew Rispoli (1582–1639)

:*  :* Peter Paul Borg (1843-1934)

:*

:* Peter Paul Borg (1843-1934)

:*

Further reading

Department of Philosophy, University of Malta

Philosophy – Junior College

School of Practical Philosophy

The Augustinian Institute

Philosophy Sharing Foundation

{{Malta topics

Philosophy in Malta refers to the philosophy of Maltese nationals or those of Maltese descent, whether living in

Philosophy in Malta refers to the philosophy of Maltese nationals or those of Maltese descent, whether living in Malta

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

or abroad, whether writing in their native Maltese language

Maltese ( mt, Malti, links=no, also ''L-Ilsien Malti'' or '), is a Semitic language derived from late medieval Sicilian Arabic with Romance superstrata spoken by the Maltese people. It is the national language of Malta and the only offic ...

or in a foreign language. Though Malta is not more than a tiny Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a subcontinent of Eurasia and it is located entirel ...

an island in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the ...

, for the last six centuries its very small population happened to come in close contact with some of Europe's main political

Politics (from , ) is the set of activities that are associated with making decisions in groups, or other forms of power relations among individuals, such as the distribution of resources or status. The branch of social science that stud ...

, academic

An academy (Attic Greek: Ἀκαδήμεια; Koine Greek Ἀκαδημία) is an institution of secondary or tertiary higher learning (and generally also research or honorary membership). The name traces back to Plato's school of philosophy, ...

and intellectual

An intellectual is a person who engages in critical thinking, research, and reflection about the reality of society, and who proposes solutions for the normative problems of society. Coming from the world of culture, either as a creator or a ...

movements. Philosophy was among the interests fostered by its academics

An academy (Attic Greek: Ἀκαδήμεια; Koine Greek Ἀκαδημία) is an institution of secondary or tertiary higher learning (and generally also research or honorary membership). The name traces back to Plato's school of philosophy, ...

and intellectuals.

For the greater part of its history, in Malta philosophy was simply studied as part of a basic institutional programme which mainly prepared candidates to become priests, lawyers

A lawyer is a person who practices law. The role of a lawyer varies greatly across different legal jurisdictions. A lawyer can be classified as an advocate, attorney, barrister, canon lawyer, civil law notary, counsel, counselor, solicitor, ...

or physicians. It was only during the latter part of the 20th century that philosophy began to acquire an ever-growing importance of its own. Nevertheless, throughout the years a few Maltese academics and intellectuals have stood out for their philosophical prowess and acumen. Despite their limitations, they gave their modest share for the understanding of philosophy and some of the areas it covers.

Though, from the mid-16th century onwards, in Malta philosophy was taught at various institutions of higher education, from the latter part of the 18th century onwards the main academic body which promoted philosophical activity and research was the University of Malta

The University of Malta (, UM, formerly UOM) is a higher education institution in Malta. It offers undergraduate bachelor's degrees, postgraduate master's degrees and postgraduate doctorates. It is a member of the European University Association ...

. Today, mainly due to easier access to data sources and to enhanced communication networks, such philosophical inquiries and pursuits are more extensive in prevalence as in content.

Short history

Pre-Knights Period (pre-1530)

Before the advent of theKnights Hospitaller

The Order of Knights of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem ( la, Ordo Fratrum Hospitalis Sancti Ioannis Hierosolymitani), commonly known as the Knights Hospitaller (), was a medieval and early modern Catholic military order. It was headq ...

to Malta in the first half of the 16th century, the Maltese Islands

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

were a forlorn place with little, if any, political importance. The few intellectuals who lived here grew within or around the Catholic religious order

In the Catholic Church, a religious order is a community of consecrated life

Consecrated life (also known as religious life) is a state of life in the Catholic Church lived by those faithful who are called to follow Jesus Christ in a more ex ...

s that were present. Their cultural ties were mostly with nearby Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

. Philosophy was mainly studied as a stepping stone to theology. Back then, Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

was a celebrated and thriving academic, intellectual and cultural centre, and all local professionals studied there. At the time, the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history

The history of Europe is traditionally divided into four time periods: prehistoric Europe (prior to about 800 BC), classical antiquity (800 BC to AD ...

was in full bloom. Though the Counter-Reformation played an important part in every academic and intellectual institution, literature issued by the major Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

educationalists, including Martin Luther

Martin Luther (; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, theologian, author, hymnwriter, and professor, and Augustinian friar. He is the seminal figure of the Protestant Reformation and the namesake of Lutherani ...

, were available and read extensively.

Hospitaller rule (1530–1798)

TheKnights Hospitaller

The Order of Knights of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem ( la, Ordo Fratrum Hospitalis Sancti Ioannis Hierosolymitani), commonly known as the Knights Hospitaller (), was a medieval and early modern Catholic military order. It was headq ...

made Malta their island-home in 1530 and remained sovereign rulers of the islands until they were expelled by Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

in 1798. As a rule, they cared about education and cultivation as much as their military campaigns and their economic welfare. Though they encouraged higher learning by giving protection to the various colleges and universities that were established (especially by Catholic religious order

In the Catholic Church, a religious order is a community of consecrated life

Consecrated life (also known as religious life) is a state of life in the Catholic Church lived by those faithful who are called to follow Jesus Christ in a more ex ...

s), they also kept a very strict surveillance on all aspects of scholarship. They certainly did not like being picked on by the Inquisition

The Inquisition was a group of institutions within the Catholic Church whose aim was to combat heresy, conducting trials of suspected heretics. Studies of the records have found that the overwhelming majority of sentences consisted of penances, ...

, which could make them look bad with the Pope

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

in Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

.

Though philosophy continued to be mainly viewed as the ''hand-maid'' of theology, some intellectuals had an interest in cautiously branching out along some pathways of their own. Though the philosophical contributions of these masters are fascinating in themselves, prevalent control and restrictions on intellectual activity hardly ever left them room for originality and innovation.

During this period intellectual circles were practically all part of the great movement of Scholasticism, almost giving godlike status to

Though philosophy continued to be mainly viewed as the ''hand-maid'' of theology, some intellectuals had an interest in cautiously branching out along some pathways of their own. Though the philosophical contributions of these masters are fascinating in themselves, prevalent control and restrictions on intellectual activity hardly ever left them room for originality and innovation.

During this period intellectual circles were practically all part of the great movement of Scholasticism, almost giving godlike status to Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ph ...

. Nonetheless, they were divided into two intellectually opposing camps: the larger group which read the great Stagirite through the eyes of Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas, OP (; it, Tommaso d'Aquino, lit=Thomas of Aquino; 1225 – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican friar and priest who was an influential philosopher, theologian and jurist in the tradition of scholasticism; he is known wit ...

, and the others who read him through the eyes of John Duns Scotus

John Duns Scotus ( – 8 November 1308), commonly called Duns Scotus ( ; ; "Duns the Scot"), was a Scottish Catholic priest and Franciscan friar, university professor, philosopher, and theologian. He is one of the four most important ...

. All of these academics and intellectuals produced large numbers of commentaries, either on Aristotle or on their respective mentor. Their creativity was largely expressed strictly within the confines of their particular school of thought, and this severely restricted their novelty.

During the 18th-century part of the period of the Knights Hospitaller, science and the scientific method began to make head-way over the trenches of the Scholastics. This line of thought was generally not pursued by ecclesiastics, on whom control was more stern, but by lay professionals, especially doctors. These, however, usually had no sway over students registered with academic institutions, which were still rigorously controlled by members of religious orders

A religious order is a lineage of communities and organizations of people who live in some way set apart from society in accordance with their specific religious devotion, usually characterized by the principles of its founder's religious pract ...

.

Interregnum Period (1798–1813)

Towards the end of the period of the Hospitallers in Malta, ideas which had been explosive through theFrench Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in coup of 18 Brumaire, November 1799. Many of its ...

of 1789 began to make way into some intellectual circles susceptible to them. They came to full fruition around 1798, when Napoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader wh ...

invaded Malta and expelled the Hospitallers. However, they were already making the rounds during the decade preceding Napoleon. Of course, these ideas were much influenced by Illuminist philosophies, especially in France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

.

British Colonial Period (1813–1964)

During this period, the higher schools resumed their business very much as was done during Hospitaller rule. Again Scholasticism came to the fore and flourished. However, this time around, it was theThomist

Thomism is the philosophical and theological school that arose as a legacy of the work and thought of Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274), the Dominican philosopher, theologian, and Doctor of the Church. In philosophy, Aquinas' disputed questions a ...

version which prevailed almost exclusively, even if circumstances, along two centuries and a half of British rule, changed drastically over the years. As in former years, the larger part of the philosophers of this period were ecclesiastics, predominantly members of religious orders

A religious order is a lineage of communities and organizations of people who live in some way set apart from society in accordance with their specific religious devotion, usually characterized by the principles of its founder's religious pract ...

. Again, due to censor and control, they hardly ever ventured to propose anything philosophically bold or imaginative. An outstanding exception to all of these was Manuel Dimech

Manwel Dimech, also known as Manuel Dimech (25 December 1860 – 17 April 1921) was a Maltese socialist, philosopher, journalist, writer, poet and social revolutionary. Born in Valletta and brought up in extreme poverty and illiteracy, Dimech sp ...

, who lived and worked during the first decade of the 20th century. He not only did not adhere to any form of Scholasticism but, furthermore, was a surprisingly innovative and original philosopher and social reformer.

Post-Independence Period (since 1964)

By the time of Malta's independence Scholasticism had waned and slowly faded away. Very few continued to uncritically adhere to its tenets, and these were restricted to small religious (particularly Catholic) circles.Chair of Philosophy at the University of Malta

The following is the list of professors who held the Chair of Philosophy at theUniversity of Malta

The University of Malta (, UM, formerly UOM) is a higher education institution in Malta. It offers undergraduate bachelor's degrees, postgraduate master's degrees and postgraduate doctorates. It is a member of the European University Association ...

, Malta's highest academic philosophy institution. The dates refer to their period of tenure. The chair of philosophy was established in 1771 by the Grand Master of the Knights Hospitaller, Manuel Pinto da Fonseca

Manuel Pinto da Fonseca (also ''Emmanuel Pinto de Fonseca''; 24 May 1681 – 23 January 1773) was a Portuguese nobleman, the 68th Grand Master of the Order of Saint John, from 1741 until his death.

He undertook many building projects, introduc ...

, when he transformed the '' Collegium Melitense'' (Maltese College) of the Jesuits

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders = ...

into the University of Malta

The University of Malta (, UM, formerly UOM) is a higher education institution in Malta. It offers undergraduate bachelor's degrees, postgraduate master's degrees and postgraduate doctorates. It is a member of the European University Association ...

.

:

Growing awareness

Research

Since the 1990s there has been an effort to aptly recognise and duly honour the modest share of philosophy in Malta. The necessity arose for two main reasons. One, because the Maltese ''themselves'', mostly due to a dearth of required research, did not acknowledge, much less appreciate, any local philosophical tradition; and, secondly, because any activity that was being carried out in the philosophical field—whether it was teaching, writing or simply discussing—was done as if the Maltese themselves had, at most, a present without a past. Archival work revealed names and manuscripts and personalities,P. Serracino Inglott, 'Presentation', ''20th Century Philosophy in Malta'', M. Montebello, Agius & Agius Publications, Malta, 2009, p.11. text-books were published (1995; 2001) and courses were read at theUniversity of Malta

The University of Malta (, UM, formerly UOM) is a higher education institution in Malta. It offers undergraduate bachelor's degrees, postgraduate master's degrees and postgraduate doctorates. It is a member of the European University Association ...

(1996/97; 2012/13; 2013/14) and at other institutions of higher education. A first public conference on ‘Maltese’ philosophy was also organised (1996). A further step was taken by the establishment of Philosophy Sharing Foundation (2012).

Appreciation

Since the 16th century, philosophy has contributed to the academic and, sometimes, the intellectual and cultural life of Maltese intelligentsia. In most cases it functioned as a tool of the establishment—including the

Since the 16th century, philosophy has contributed to the academic and, sometimes, the intellectual and cultural life of Maltese intelligentsia. In most cases it functioned as a tool of the establishment—including the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

―to conserve and perpetuate orthodox and official doctrines. In other cases it offered alternative and imaginative routes of thinking. Despite its relatively long philosophical tradition, however, Malta has no particular philosophy associated to its name. Though sometimes innovative and creative, in their large majority Maltese philosophers have always worked with imported ideas and, but for very rare cases (like in the case of Manuel Dimech

Manwel Dimech, also known as Manuel Dimech (25 December 1860 – 17 April 1921) was a Maltese socialist, philosopher, journalist, writer, poet and social revolutionary. Born in Valletta and brought up in extreme poverty and illiteracy, Dimech sp ...

), seldom did break new ground in the philosophical field. Although the philosophy of many of them did not affect social or political life, some interacted lively with current affairs and sometimes even stimulated societal change. Throughout the ages, Maltese philosophers did not adhere to just one philosophical tradition. The larger part pertains to the Aristotelico-Thomistic school. Every now and then, however, other trends appear along the way, especially during the last quarter of the 20th century, such as humanism, empiricism, pragmatism, existentialism, linguistic analysis and some others. But for unique, rather than rare, exceptions, theism has been a constant trait throughout the whole Maltese philosophical tradition.

During the last thirty years or so philosophy in Malta took an unprecedented twist. Peter Serracino Inglott gave it an extraordinary new breath of life by widening its horizon, diversifying its interests and firmly propelling it into social and political action. This style then was taken up by others who continued this trend.

Some Maltese Philosophers

The following list includes some of Malta's best and most representative philosophers through the ages. Most of the philosophical contributions made by these scholars have lasting significance since they go beyond reflections which are merely descriptive, comparative or contextual. Some of them also appeal for their creativity and style. Others in the list are minor philosophers who contributed to different areas of philosophy. 15th century

:* Peter Caxaro (''c.'' 1400–1485)

17th century

:* Maximilian Balzan (1637–1711)

:* John Matthew Rispoli (1582–1639)

:*

15th century

:* Peter Caxaro (''c.'' 1400–1485)

17th century

:* Maximilian Balzan (1637–1711)

:* John Matthew Rispoli (1582–1639)

:* Dominic Borg Dominic Borg (17th century) was a minor Maltese philosopher who specialised in logic and rhetoric.

Life

He probably lectured at the '' Collegium Melitense'' in Valletta. The extant works of Borg reveal practically nothing in terms of biographical ...

(birthdate unknown)

:* Saverius Pace (birthdate unknown)

18th century

:* George Sagnani (1667-1732)

:* Constance Vella (1687–1759)

:* John Constance Parnis (1695–1735)

:* Joseph Demarco

Joseph is a common male given name, derived from the Hebrew Yosef (יוֹסֵף). "Joseph" is used, along with "Josef", mostly in English, French and partially German languages. This spelling is also found as a variant in the languages of the mo ...

(1723–1789)

:* Saviour Bernard (1724–1806)

:* John Nicholas Muscat (1735–''c.'' 1800)

:* Dominic Bezzina (born ''c.'' mid-18th century)

:* Fortunatus Victor Costa (birthdate unknown)

:* Gaetanus Matthew Perez (birthdate unknown)

:* Henry Regnand (birthdate unknown)

19th century

:* Michael Anthony Vassalli (1764–1829)

:* Jerome Inglott (1776–1835)

:* Nicholas Zammit

Nicholas Zammit (1815–1899) was a Maltese medical doctor, an architect, an artistic designer, and a major philosopher. His area of specialisation in philosophy was chiefly ethics. Throughout his philosophical career he did not adhere to just on ...

(1815–1899)

:* Aloisio Galea (1851-1905)

20th century

:* Peter Paul Borg (1843-1934)

:*

:* Peter Paul Borg (1843-1934)

:* Manuel Dimech

Manwel Dimech, also known as Manuel Dimech (25 December 1860 – 17 April 1921) was a Maltese socialist, philosopher, journalist, writer, poet and social revolutionary. Born in Valletta and brought up in extreme poverty and illiteracy, Dimech sp ...

(1860–1921)

:* John Formosa (1869-1941)

:* Anastasio Cuschieri (1872–1962)

:* Albert Busuttil (1891-1956)

:* Angelo Pirotta (1894–1956)

:* Nazzareno Camilleri (1906–1973)

:* John Micallef (1923–2003)

:* Edward De Bono (b. 1933-2021)

:* Peter Serracino Inglott (1936–2012)

:* Kenneth Wain (b. 1943)

:* Joe Friggieri (b. 1946)

:* Oliver Friggieri

Oliver Friggieri (27 March 194721 November 2020) was a Maltese poet, novelist, literary critic, and philosopher. He led the establishment of literary history and criticism in Maltese while teaching at the University of Malta, studying the work ...

(1947–2020)

:* Tarcisio Zarb (b. 1952)

:* Sandra Dingli (b. 1952)

:* Mario Vella

Mario Vella (born 1953 in Tripoli) is a Maltese philosopher, economist and politician. He was Governor of the Central Bank of Malta from 2016 to 2020.

Biography Studies and academic career

Vella was born to a Maltese family in Tripoli, Libya ...

(b. 1953)

:* John Peter Portelli (b. 1954)

:* Emmanuel Agius

Emmanuel Agius (born 1954) is a Maltese minor philosopher mostly specialised and interested in ethics.

Education

Agius was born at Mqabba, Malta, in 1954. He studied at the University of Malta from where he acquired a Bachelor’s degree and a ...

(b. 1954)

:* Anthony Abela (1954–2006)

:* Michael Zammit

Michael Zammit (born 1954) is a Maltese philosopher, specialised in Ancient and Eastern philosophy.

Life

Zammit was born at Valletta in 1954. He studied Philosophy at the University of Malta, acquiring a Bachelor of Philosophy in 1976, and a ...

(b. 1954)

:* Joseph Giordmaina (b. 1963)

:* John Baldacchino (b. 1964)

:* Mark Montebello

Mark Montebello (Mtarfa, Malta, 7 February 1964) is a Maltese philosopher and author. He is mostly known for his controversies with Catholic Church authorities but also for his classic biographies of Manuel Dimech and Dom Mintoff.

Private lif ...

(b. 1964)

:* Nicky Doublet (1968-2002)

:* Colette Sciberras (b. 1976)

References

Main sources

* J. Friggieri, ‘Philosophy today’, ''The Malta Year Book 1977'', ed. by H.A. Clews, De La Salle Brothers Publications, Malta 1977, pp. 465–470. * P. Serracino Inglott and C. Mangion, 'Il-Filosofija f'Malta' (Philosophy in Malta), ''Oqsma tal-Kultura Maltija'' (Areas of Maltese Culture), ed. by T. Cortis, Ministry of Education and the Interior, Malta 1991, pp. 263–271. * M. Montebello, ''Il-Ktieb tal-Filosofija f’Malta'' (''A Source Book of Philosophy in Malta''), two volumes, PIN Publications, Malta 2001. * J. Friggieri, ‘Letter from Malta’, ''The Philosophers’ Magazine'', 55, 4th quarter, England 2011, pp. 48–51. * M. Montebello, ''Malta's Philosophy & Philosophers'', PIN Publications, Malta 2011.External links

Further reading

Department of Philosophy, University of Malta

Philosophy – Junior College

School of Practical Philosophy

The Augustinian Institute

Philosophy Sharing Foundation

{{Malta topics