Phillis Wheatley on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Phillis Wheatley Peters, also spelled Phyllis and Wheatly ( – December 5, 1784) was an American author who is considered the first African-American author of a published book of poetry. Gates, Henry Louis, ''Trials of Phillis Wheatley: America's First Black Poet and Her Encounters with the Founding Fathers'', Basic Civitas Books, 2010, p. 5. Born in

Many colonists found it difficult to believe that an African slave was writing "excellent" poetry. Wheatley had to defend her authorship of her poetry in court in 1772.Henry Louis Gates and Anthony Appiah (eds), ''Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience,'' Basic Civitas Books, 1999, p. 1171. She was examined by a group of Boston luminaries, including John Erving, Reverend Charles Chauncey,

Many colonists found it difficult to believe that an African slave was writing "excellent" poetry. Wheatley had to defend her authorship of her poetry in court in 1772.Henry Louis Gates and Anthony Appiah (eds), ''Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience,'' Basic Civitas Books, 1999, p. 1171. She was examined by a group of Boston luminaries, including John Erving, Reverend Charles Chauncey,

Phillis Wheatley's Use of Classicism"

, ''American Literature'' 52.1 (1980): 97–111. Retrieved November 2, 2009, p. 101. John C. Shields, noting that her poetry did not simply reflect the literature she read but was based on her personal ideas and beliefs, writes:

"Phillis Wheatley's Use of Classicism"

, ''American Literature'' 52.1 (1980), p. 100. Shields sums up her writing as being "contemplative and reflective rather than brilliant and shimmering." She repeated three primary elements: Christianity, classicism, and hierophantic solar worship.Shields

"Phillis Wheatley's Use of Classicism"

, ''American Literature'' 52.1 (1980), p. 103. The hierophantic solar worship was part of what she brought with her from Africa; the worship of sun gods is expressed as part of her African culture, which may be why she used so many different words for the sun. For instance, she uses Aurora eight times, "Apollo seven, Phoebus twelve, and Sol twice." Shields believes that the word "light" is significant to her as it marks her African history, a past that she has left physically behind. He notes that Sun is a homonym for Son, and that Wheatley intended a double reference to Christ. Wheatley also refers to "heav'nly muse" in two of her poems: "To a Clergy Man on the Death of his Lady" and "Isaiah LXIII," signifying her idea of the Christian deity. Classical allusions are prominent in Wheatley's poetry, which Shields argues set her work apart from that of her contemporaries: "Wheatley's use of classicism distinguishes her work as original and unique and deserves extended treatment." Particularly extended engagement with the Classics can be found in the poem "To Maecenas", where Wheatley uses references to

"Students meet literary world at Greenwich Book Festival"

News, University of Greenwich, June 14, 2018.

online

* Engberg, Kathrynn Seidler, ''The Right to Write: The Literary Politics of Anne Bradstreet and Phillis Wheatley''. Washington, D.C.: University Press of America, 2009. * Langley, April C. E. (2008). ''The Black Aesthetic Unbound: Theorizing the Dilemma of Eighteenth-century African American Literature''. Columbus: Ohio State University Press. * Ogude, S. E. (1983). ''Genius in Bondage: A Study of the Origins of African Literature in English''. Ile-Ife, Nigeria: University of Ife Press. * Reising, Russel J. (1996). ''Loose Ends: Closure and Crisis in the American Social Text''. Durham: Duke University Press. * Robinson, William Henry (1981). ''Phillis Wheatley: A Bio-bibliography''. Boston: GK Hall. * Robinson, William Henry (1982). ''Critical Essays on Phillis Wheatley''. Boston: GK Hall. * Robinson, William Henry (1984). ''Phillis Wheatley and Her Writings''. New York: Garland. * Shockley, Ann Allen (1988). ''Afro-American Women Writers, 1746–1933: An Anthology and Critical Guide''. Boston: GK Hall. * Waldstreicher, David. "The Wheatleyan Moment." ''Early American Studies'' (2011): 522–551

online

* Waldstreicher, David. "Ancients, Moderns, and Africans: Phillis Wheatley and the Politics of Empire and Slavery in the American Revolution." ''Journal of the Early Republic'' 37.4 (2017): 701–733

online

* Zuck, Rochelle Raineri. "Poetic Economics: Phillis Wheatley and the Production of the Black Artist in the Early Atlantic World." ''Ethnic Studies Review'' 33.2 (2010): 143–16

online

; Poetry (inspired by Wheatley) * Clarke, Alison (2020). ''Phillis''. University of Calgary Press. * Jeffers, Honorée Fanonne (2020). ''The Age of Phillis''.

"Phillis Wheatley"

National Women's History Museum

Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library

Emory University

Phillis Wheatley collection, 1757–1773

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Wheatley, Phillis 1753 births 1784 deaths Deaths in childbirth American women poets American people of Senegalese descent American people of Gambian descent American Congregationalists Cultural history of Boston Writers from Boston People of colonial Massachusetts People of Massachusetts in the American Revolution African-American women writers African-American poets Colonial American poets 18th-century American poets People from colonial Boston African-American Christians 18th-century American women writers Free Negroes Black Patriots 18th-century African-American women Literate American slaves Colonial American expatriates in Great Britain

West Africa

West Africa or Western Africa is the westernmost region of Africa. The United Nations defines Western Africa as the 16 countries of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Mali, Maurit ...

, she was kidnapped and subsequently sold into enslavement at the age of seven or eight and transported to North America, where she was bought by the Wheatley family of Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

. After she learned to read and write, they encouraged her poetry when they saw her talent.

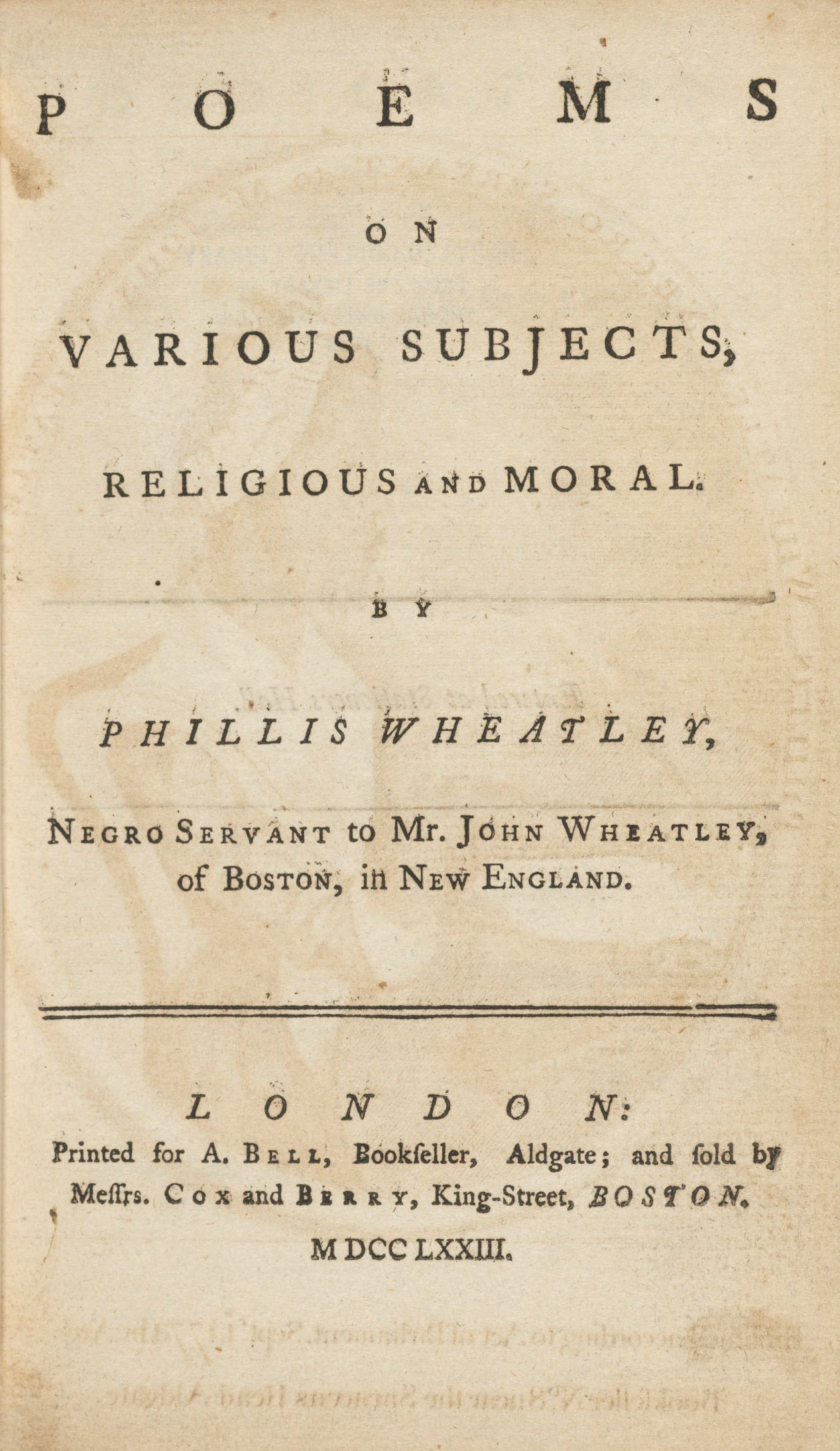

On a 1773 trip to London with her enslaver's son, seeking publication of her work, Wheatley met prominent people who became patrons. The publication in London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

of her '' Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral'' on September 1, 1773, brought her fame both in England and the American colonies. Figures such as George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of th ...

praised her work. A few years later, African-American poet Jupiter Hammon praised her work in a poem of his own.

Wheatley was emancipated

Emancipation generally means to free a person from a previous restraint or legal disability. More broadly, it is also used for efforts to procure economic and social rights, political rights or equality, often for a specifically disenfranchis ...

by her enslavers shortly after the publication of her book.Smith, Hilda L. (2000), ''Women's Political and Social Thought: An Anthology'', Indiana University Press, p. 123. They soon died, and she married John Peters, a poor grocer. They lost three children, who died young. Wheatley-Peters died in poverty and obscurity at the age of 31.

Early life

Although the date and place of her birth are not documented, scholars believe that Phillis Wheatley was born in 1753 inWest Africa

West Africa or Western Africa is the westernmost region of Africa. The United Nations defines Western Africa as the 16 countries of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Mali, Maurit ...

, most likely in present-day Gambia

The Gambia,, ff, Gammbi, ar, غامبيا officially the Republic of The Gambia, is a country in West Africa. It is the smallest country within mainland AfricaHoare, Ben. (2002) ''The Kingfisher A-Z Encyclopedia'', Kingfisher Publicatio ...

or Senegal

Senegal,; Wolof: ''Senegaal''; Pulaar: 𞤅𞤫𞤲𞤫𞤺𞤢𞥄𞤤𞤭 (Senegaali); Arabic: السنغال ''As-Sinighal'') officially the Republic of Senegal,; Wolof: ''Réewum Senegaal''; Pulaar : 𞤈𞤫𞤲𞤣𞤢𞥄𞤲𞤣𞤭 � ...

. She was sold by a local chief to a visiting trader, who took her to Boston in the British Colony of Massachusetts

The Massachusetts Bay Colony (1630–1691), more formally the Colony of Massachusetts Bay, was an English settlement on the east coast of North America around the Massachusetts Bay, the northernmost of the several colonies later reorganized as th ...

, on July 11, 1761, on a slave ship

Slave ships were large cargo ships specially built or converted from the 17th to the 19th century for transporting slaves. Such ships were also known as "Guineamen" because the trade involved human trafficking to and from the Guinea coast ...

called ''The Phillis''.Doak, Robin S. ''Phillis Wheatley: Slave and Poet,'' Minneapolis: Compass Point Books, 2007. It was owned by Timothy Fitch and captained by Peter Gwinn.

On arrival in Boston, she was bought by the wealthy Boston merchant and tailor John Wheatley as a slave for his wife Susanna. John and Susanna Wheatley named her Phillis, after the ship that had transported her to America. She was given their last name of Wheatley, as was a common custom if any surname was used for enslaved people.

The Wheatleys' 18-year-old daughter, Mary, was Phillis's first tutor in reading and writing. Their son, Nathaniel, also helped her. John Wheatley was known as a progressive throughout New England; his family afforded Phillis an unprecedented education for an enslaved person, and one unusual for a woman of any race. By the age of 12, she was reading Greek and Latin classics in their original languages, as well as difficult passages from the Bible. At the age of 14, she wrote her first poem, "To the University of Cambridge arvard in New England". Recognizing her literary ability, the Wheatley family supported Phillis's education and left household labor to their other domestic enslaved workers. The Wheatleys often showed off her abilities to friends and family. Strongly influenced by her readings of the works of Alexander Pope

Alexander Pope (21 May 1688 O.S. – 30 May 1744) was an English poet, translator, and satirist of the Enlightenment era who is considered one of the most prominent English poets of the early 18th century. An exponent of Augustan literature, ...

, John Milton

John Milton (9 December 1608 – 8 November 1674) was an English poet and intellectual. His 1667 epic poem '' Paradise Lost'', written in blank verse and including over ten chapters, was written in a time of immense religious flux and political ...

, Homer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

, Horace

Quintus Horatius Flaccus (; 8 December 65 – 27 November 8 BC), known in the English-speaking world as Horace (), was the leading Roman lyric poet during the time of Augustus (also known as Octavian). The rhetorician Quintilian regarded his ' ...

, and Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; traditional dates 15 October 7021 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Roman poet of the Augustan period. He composed three of the most famous poems in Latin literature: t ...

, Phillis began to write poetry.

Later life

In 1773, at the age of 20, Phillis accompanied Nathaniel Wheatley to London in part for her health (she suffered from chronic asthma), but largely because Susanna believed Phillis would have a better chance of publishing her book of poems there. She had an audience withFrederick Bull

Frederick George Bull, born at Hackney, London on 2 April 1875 and found drowned at St Annes-on-Sea, Lancashire, on 16 September 1910, was an English first-class cricketer who played for Essex.

Bull was a lower-order right-hand batsman and an ...

, who was the Lord Mayor of London

The Lord Mayor of London is the mayor of the City of London and the leader of the City of London Corporation. Within the City, the Lord Mayor is accorded precedence over all individuals except the sovereign and retains various traditional powe ...

, and other significant members of British society. (An audience with King George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of the two kingdoms on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Br ...

was arranged, but Phillis returned to Boston before it could take place.) Selina Hastings, Countess of Huntingdon

Selina Hastings, Countess of Huntingdon (24 August 1707 – 17 June 1791) was an English religious leader who played a prominent part in the religious revival of the 18th century and the Methodist movement in England and Wales. She founded an ...

, became interested in the talented young African woman and subsidized the publication of Wheatley's volume of poems, which appeared in London in the summer of 1773. As Hastings was ill, she and Phillis never met.

After her book was published, by November 1773, the Wheatleys emancipated Phillis. Her former enslaver Susanna died in the spring of 1774, and John in 1778. Shortly after, Wheatley met and married John Peters, a free black grocer. They lived in poor conditions and two of their babies died.

John was improvident and was imprisoned for debt in 1784. With a sickly infant son to provide for, Phillis became a scullery maid at a boarding house, work she had not done before. She died on December 5, 1784, at the age of 31. Her infant son died soon after.

Other writings

Phillis Wheatley wrote a letter to ReverendSamson Occom

Samson Occom (1723 – July 14, 1792; also misspelled as Occum and Alcom) was a member of the Mohegan nation, from near New London, Connecticut, who became a Presbyterian cleric. Occom was the second Native American to publish his writings in Eng ...

, commending him on his ideas and beliefs stating that enslaved people should be given their natural-born rights in America. Wheatley also exchanged letters with the British philanthropist John Thornton, who discussed Wheatley and her poetry in correspondence with John Newton

John Newton (; – 21 December 1807) was an English evangelical Anglican cleric and slavery abolitionist. He had previously been a captain of slave ships and an investor in the slave trade. He served as a sailor in the Royal Navy (after forc ...

. Along with her poetry, she was able to express her thoughts, comments and concerns to others.

In 1775, she sent a copy of a poem entitled "To His Excellency, George Washington" to the then-military general. The following year, Washington invited Wheatley to visit him at his headquarters in Cambridge, Massachusetts

Cambridge ( ) is a city in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, United States. As part of the Boston metropolitan area, the cities population of the 2020 U.S. census was 118,403, making it the fourth most populous city in the state, behind Boston, ...

, which she did in March 1776. Thomas Paine

Thomas Paine (born Thomas Pain; – In the contemporary record as noted by Conway, Paine's birth date is given as January 29, 1736–37. Common practice was to use a dash or a slash to separate the old-style year from the new-style year. In th ...

republished the poem in the ''Pennsylvania Gazette

''The Pennsylvania Gazette'' was one of the United States' most prominent newspapers from 1728 until 1800. In the several years leading up to the American Revolution the paper served as a voice for colonial opposition to British colonial rule, ...

'' in April 1776.

In 1779 Wheatley issued a proposal for a second volume of poems but was unable to publish it because she had lost her patrons after her emancipation; publication of books was often based on gaining subscriptions for guaranteed sales beforehand. The American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

(1775–1783) was also a factor. However, some of her poems that were to be included in the second volume were later published in pamphlets and newspapers.

Poetry

In 1768, Wheatley wrote "To the King's Most Excellent Majesty", in which she praised King George III for repealing the Stamp Act. As theAmerican Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revolut ...

gained strength, Wheatley's writing turned to themes that expressed ideas of the rebellious colonists.

In 1770 Wheatley wrote a poetic tribute to the evangelist George Whitefield

George Whitefield (; 30 September 1770), also known as George Whitfield, was an Anglican cleric and evangelist who was one of the founders of Methodism and the evangelical movement.

Born in Gloucester, he matriculated at Pembroke College at th ...

. Her poetry expressed Christian themes, and many poems were dedicated to famous figures. Over one-third consist of elegies

An elegy is a poem of serious reflection, and in English literature usually a lament for the dead. However, according to ''The Oxford Handbook of the Elegy'', "for all of its pervasiveness ... the 'elegy' remains remarkably ill defined: sometime ...

, the remainder being on religious, classical, and abstract themes. She seldom referred to her own life in her poems. One example of a poem on slavery is "On being brought from Africa to America":

Many colonists found it difficult to believe that an African slave was writing "excellent" poetry. Wheatley had to defend her authorship of her poetry in court in 1772.Henry Louis Gates and Anthony Appiah (eds), ''Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience,'' Basic Civitas Books, 1999, p. 1171. She was examined by a group of Boston luminaries, including John Erving, Reverend Charles Chauncey,

Many colonists found it difficult to believe that an African slave was writing "excellent" poetry. Wheatley had to defend her authorship of her poetry in court in 1772.Henry Louis Gates and Anthony Appiah (eds), ''Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience,'' Basic Civitas Books, 1999, p. 1171. She was examined by a group of Boston luminaries, including John Erving, Reverend Charles Chauncey, John Hancock

John Hancock ( – October 8, 1793) was an American Founding Father, merchant, statesman, and prominent Patriot of the American Revolution. He served as president of the Second Continental Congress and was the first and third Governor of the ...

, Thomas Hutchinson, the governor of Massachusetts, and his lieutenant governor Andrew Oliver. They concluded she had written the poems ascribed to her and signed an attestation, which was included in the preface of her book of collected works: '' Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral,'' published in London in 1773. Publishers in Boston had declined to publish it, but her work was of great interest to influential people in London.

There, Selina, Countess of Huntingdon

Selina Hastings, Countess of Huntingdon (24 August 1707 – 17 June 1791) was an English religious leader who played a prominent part in the religious revival of the 18th century and the Methodist movement in England and Wales. She founded an ...

, and the Earl of Dartmouth acted as patrons to help Wheatley gain publication. Her poetry received comment in ''The London Magazine

''The London Magazine'' is the title of six different publications that have appeared in succession since 1732. All six have focused on the arts, literature and miscellaneous topics.

1732–1785

''The London Magazine, or, Gentleman's Monthly I ...

'' in 1773, which published her poem "Hymn to the Morning" as a specimen of her work, writing: " ese poems display no astonishing power of genius; but when we consider them as the productions of a young untutored African, who wrote them after six months casual study of the English language and of writing, we cannot suppress our admiration of talents so vigorous and lively." ''Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral'' was printed in 11 editions until 1816.

In 1778, the African-American poet Jupiter Hammon wrote an ode

An ode (from grc, ᾠδή, ōdḗ) is a type of lyric poetry. Odes are elaborately structured poems praising or glorifying an event or individual, describing nature intellectually as well as emotionally. A classic ode is structured in three majo ...

to Wheatley ("An Address to Miss Phillis Wheatley"). His master Lloyd had temporarily moved with his slaves to Hartford, Connecticut

Hartford is the capital city of the U.S. state of Connecticut. It was the seat of Hartford County until Connecticut disbanded county government in 1960. It is the core city in the Greater Hartford metropolitan area. Census estimates since the ...

, during the Revolutionary War. Hammon thought that Wheatley had succumbed to what he believed were pagan influences in her writing, and so his "Address" consisted of 21 rhyming quatrains, each accompanied by a related Bible verse, that he thought would compel Wheatley to return to a Christian path in life.

In 1838 Boston-based publisher and abolitionist Isaac Knapp

Isaac Knapp (January 11, 1804 – September 14, 1843) was an American abolitionist printer, publisher, and bookseller in Boston, Massachusetts. He is remembered primarily for his collaboration with William Lloyd Garrison in printing and publ ...

published a collection of Wheatley's poetry, along with that of enslaved North Carolina poet George Moses Horton, under the title ''Memoir and Poems of Phillis Wheatley, A Native African and a Slave. Also, Poems by a Slave''. Wheatley's memoir was earlier published in 1834 by Geo W. Light but did not include poems by Horton.

Thomas Jefferson, in his book ''Notes on the State of Virginia

''Notes on the State of Virginia'' (1785) is a book written by the American statesman, philosopher, and planter Thomas Jefferson. He completed the first version in 1781 and updated and enlarged the book in 1782 and 1783. It originated in Jeffers ...

,'' was unwilling to acknowledge the value of her work or the work of any black poet. He wrote:Misery is often the parent of the most affecting touches in poetry. Among the blacks is misery enough, God knows, but no poetry. Love is the peculiar oestrum of the poet. Their love is ardent, but it kindles the senses only, not the imagination. Religion indeed has produced a Phyllis Whately but it could not produce a poet. The compositions published under her name are below the dignity of criticism.

Style, structure, and influences on poetry

Wheatley believed that the power of poetry was immeasurable.Shields, John C.Phillis Wheatley's Use of Classicism"

, ''American Literature'' 52.1 (1980): 97–111. Retrieved November 2, 2009, p. 101. John C. Shields, noting that her poetry did not simply reflect the literature she read but was based on her personal ideas and beliefs, writes:

"Wheatley had more in mind than simple conformity. It will be shown later that her allusions to the sun god and to the goddess of the morn, always appearing as they do here in close association with her quest for poetic inspiration, are of central importance to her."This poem is arranged into three stanzas of four lines in

iambic tetrameter Iambic tetrameter is a poetic meter in ancient Greek and Latin poetry; as the name of ''a rhythm'', iambic tetrameter consists of four metra, each metron being of the form , x – u – , , consisting of a spondee and an iamb, or two iambs. Ther ...

, followed by a concluding couplet in iambic pentameter

Iambic pentameter () is a type of metric line used in traditional English poetry and verse drama. The term describes the rhythm, or meter, established by the words in that line; rhythm is measured in small groups of syllables called " feet". "Iam ...

. The rhyme scheme

A rhyme scheme is the pattern of rhymes at the end of each line of a poem or song. It is usually referred to by using letters to indicate which lines rhyme; lines designated with the same letter all rhyme with each other.

An example of the ABAB r ...

is ABABCC.Shields"Phillis Wheatley's Use of Classicism"

, ''American Literature'' 52.1 (1980), p. 100. Shields sums up her writing as being "contemplative and reflective rather than brilliant and shimmering." She repeated three primary elements: Christianity, classicism, and hierophantic solar worship.Shields

"Phillis Wheatley's Use of Classicism"

, ''American Literature'' 52.1 (1980), p. 103. The hierophantic solar worship was part of what she brought with her from Africa; the worship of sun gods is expressed as part of her African culture, which may be why she used so many different words for the sun. For instance, she uses Aurora eight times, "Apollo seven, Phoebus twelve, and Sol twice." Shields believes that the word "light" is significant to her as it marks her African history, a past that she has left physically behind. He notes that Sun is a homonym for Son, and that Wheatley intended a double reference to Christ. Wheatley also refers to "heav'nly muse" in two of her poems: "To a Clergy Man on the Death of his Lady" and "Isaiah LXIII," signifying her idea of the Christian deity. Classical allusions are prominent in Wheatley's poetry, which Shields argues set her work apart from that of her contemporaries: "Wheatley's use of classicism distinguishes her work as original and unique and deserves extended treatment." Particularly extended engagement with the Classics can be found in the poem "To Maecenas", where Wheatley uses references to

Maecenas

Gaius Cilnius Maecenas ( – 8 BC) was a friend and political advisor to Octavian (who later reigned as emperor Augustus). He was also an important patron for the new generation of Augustan poets, including both Horace and Virgil. During the re ...

to depict the relationship between her and her own patrons, as well as making reference to Achilles

In Greek mythology, Achilles ( ) or Achilleus ( grc-gre, Ἀχιλλεύς) was a hero of the Trojan War, the greatest of all the Greek warriors, and the central character of Homer's ''Iliad''. He was the son of the Nereid Thetis and Peleus, k ...

and Patroclus

In Greek mythology, as recorded in Homer's ''Iliad'', Patroclus (pronunciation variable but generally ; grc, Πάτροκλος, Pátroklos, glory of the father) was a childhood friend, close wartime companion, and the presumed (by some later a ...

, Homer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

and Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; traditional dates 15 October 7021 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Roman poet of the Augustan period. He composed three of the most famous poems in Latin literature: t ...

. At the same time, Wheatley indicates to the complexity of her relationship with Classical texts by pointing to the sole example of Terence

Publius Terentius Afer (; – ), better known in English as Terence (), was a Roman African playwright during the Roman Republic. His comedies were performed for the first time around 166–160 BC. Terentius Lucanus, a Roman senator, brought ...

as an ancestor for her works:

The happier Terence all the choir inspir'd,While some scholars have argued that Wheatley's allusions to classical material are based on the reading of other neoclassical poetry (such as the works of

His soul replenish'd, and his bosom fir'd;

But say, ye Muses, why this partial grace,

To one alone of Afric's sable race;

Alexander Pope

Alexander Pope (21 May 1688 O.S. – 30 May 1744) was an English poet, translator, and satirist of the Enlightenment era who is considered one of the most prominent English poets of the early 18th century. An exponent of Augustan literature, ...

), Emily Greenwood

Emily Greenwood is Professor of the Classics and of Comparative Literature at Harvard University. She was formerly professor of Classics and the University Center for Human Values at Princeton University and John M. Musser Professor of Classics a ...

has demonstrated that Wheatley's work demonstrates persistent linguistic engagement with Latin texts, suggesting good familiarity with the ancient works themselves. Both Shields and Greenwood have argued that Wheatley's use of classical imagery and ideas was designed to deliver "subversive" messages to her educated, majority white audience, and argue for the freedom of Wheatley herself and other enslaved people.

Scholarly critique

Black literary scholars from the 1960s to the present in critiquing Wheatley's writing have noted the absence in it of her sense of identity as a black enslaved person. A number of black literary scholars have viewed her work—and its widespread admiration—as a barrier to the development of black people during her time and as a prime example ofUncle Tom syndrome

Uncle Tom syndrome is a theory in multicultural psychology referring to a coping skill in which individuals use passivity and submissiveness when confronted with a threat, leading to subservient behaviour and appeasement, while concealing their t ...

, believing that Wheatley's lack of awareness of her condition of enslavement furthers this syndrome among descendants of Africans in the Americas.

Some scholars thought Wheatley's perspective came from her upbringing. Writing in 1974, Eleanor Smith argued that the Wheatley family took interest in her at a young age because of her timid and submissive nature. Using this to their advantage, the Wheatley family was able to mold and shape her into a person of their liking. The family separated her from other slaves in the home and she was prevented from doing anything other than very light housework. This shaping prevented Phillis from ever becoming a threat to the Wheatley family or other people from the white community. As a result, Phillis was allowed to attend white social events and this created a misconception of the relationship between black and white people for her.

The matter of Wheatley's biography, "a white woman's memoir", has been a subject of investigation. In 2020, American poet Honorée Fanonne Jeffers

Honorée Fanonne Jeffers (born 1967) is an American poet and novelist, and a professor of English at the University of Oklahoma. She has published five collections of poetry and a novel. Her 2020 collection ''The Age of Phillis'' reexamines the l ...

published her ''The Age of Phillis'', based on the understanding that Margaretta Matilda Odell's account of Wheatley's life portrayed Wheatley inaccurately, and as a character in a sentimental novel; the poems by Jeffers attempt to fill in the gaps and recreate a more realistic portrait of Wheatley.

Legacy and honors

With the 1773 publication of Wheatley's book ''Poems on Various Subjects,'' she "became the most famous African on the face of the earth."Gates, ''The Trials of Phillis Wheatley'', p. 33.Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778) was a French Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment writer, historian, and philosopher. Known by his ''Pen name, nom de plume'' M. de Voltaire (; also ; ), he was famous for his wit, and his ...

stated in a letter to a friend that Wheatley had proved that black people could write poetry. John Paul Jones

John Paul Jones (born John Paul; July 6, 1747 July 18, 1792) was a Scottish-American naval captain who was the United States' first well-known naval commander in the American Revolutionary War. He made many friends among U.S political elites ( ...

asked a fellow officer to deliver some of his personal writings to "Phillis the African favorite of the Nine (muses) and Apollo." She was honored by many of America's founding fathers, including George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of th ...

, who wrote to her (after she wrote a poem in his honor) that "the style and manner f your poetryexhibit a striking proof of your great poetical Talents."

Critics consider her work fundamental to the genre of African-American literature

African American literature is the body of literature produced in the United States by writers of African descent. It begins with the works of such late 18th-century writers as Phillis Wheatley. Before the high point of slave narratives, African ...

, and she is honored as the first African-American woman to publish a book of poetry and the first to make a living from her writing.

*In 2002, the scholar Molefi Kete Asante

Molefi Kete Asante ( ; born Arthur Lee Smith Jr.; August 14, 1942) is an American professor and philosopher. He is a leading figure in the fields of African-American studies, African studies, and communication studies. He is currently professo ...

listed Phillis Wheatley as one of his '' 100 Greatest African Americans''.

*Wheatley is featured, along with Abigail Adams

Abigail Adams ( ''née'' Smith; November 22, [ O.S. November 11] 1744 – October 28, 1818) was the wife and closest advisor of John Adams, as well as the mother of John Quincy Adams. She was a founder of the United States, an ...

and Lucy Stone, in the Boston Women's Memorial

The Boston Women's Memorial is a trio of sculptures on the Commonwealth Avenue Mall in Boston, Massachusetts, commemorating Phillis Wheatley, Abigail Adams, and Lucy Stone.

Overview

The idea of a memorial to women was first discussed in 1992 in ...

, a 2003 sculpture on Commonwealth Avenue in Boston, Massachusetts.

*In 2012, Robert Morris University

Robert Morris University (RMU) is a private university in Moon Township, Pennsylvania. It was founded in 1921 and is named after Robert Morris, known as the "financier of the mericanrevolution." It enrolls nearly 5,000 students and offers 60 b ...

named the new building for their School of Communications and Information Sciences after Phillis Wheatley.

*Wheatley Hall at UMass Boston

The University of Massachusetts is the five-campus public university system and the only public research system in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. The university system includes five campuses (Amherst, Boston, Dartmouth, Lowell, and a medical ...

is named for Phillis Wheatley.

In 1892 a Phyllis Wheatley Circle was formed in Greenville, Mississippi

Greenville is a city in and the county seat of Washington County, Mississippi, United States. The population was 34,400 at the 2010 census. It is located in the area of historic cotton plantations and culture known as the Mississippi Delta.

H ...

. and in 1896 the Phyllis Wheatley Circle.

She is commemorated on the Boston Women's Heritage Trail

The Boston Women's Heritage Trail is a series of walking tours in Boston, Massachusetts, leading past sites important to Boston women's history. The tours wind through several neighborhoods, including the Back Bay and Beacon Hill, commemorating w ...

. The Phyllis Wheatley YWCA

The Phyllis Wheatley YWCA is a Young Women's Christian Association building in Washington, D.C., that was designed by architects Shroeder & Parish and was built in 1920. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1983.

It is nam ...

in Washington, D.C., and the Phillis Wheatley High School in Houston, Texas

Houston (; ) is the most populous city in Texas, the most populous city in the Southern United States, the fourth-most populous city in the United States, and the sixth-most populous city in North America, with a population of 2,304,580 in ...

, are named for her, as was the historic Phillis Wheatley School in Jensen Beach, Florida

Jensen Beach is an unincorporated community and census-designated place (CDP) in Martin County, Florida, United States. The population was 12,652 at the 2020 census. It is part of the Port St. Lucie, Florida Metropolitan Statistical Area.

Histor ...

, now the oldest building on the campus of American Legion Post 126 (Jensen Beach, Florida). A branch of the Richland County Library in Columbia, South Carolina

Columbia is the capital of the U.S. state of South Carolina. With a population of 136,632 at the 2020 census, it is the second-largest city in South Carolina. The city serves as the county seat of Richland County, and a portion of the city ...

, which offered the first library services to black citizens, is named for her. Phillis Wheatley Elementary School, New Orleans

Phillis Wheatley Elementary School is a school in New Orleans. The original school building was designed by the architect Charles Colbert (architect), Charles Colbert in 1954 as a Racial segregation in the United States#Education, segregated schoo ...

, opened in 1954 in Tremé

Tremé ( ) is a neighborhood in New Orleans, Louisiana. "Tremé" is often rendered as Treme, and the neighborhood is sometimes called by its more formal French name, Faubourg Tremé; it is listed in the New Orleans City Planning Districts as Trem ...

, one of the oldest African-American neighborhoods in the US. The Phillis Wheatley Community Center opened in 1920 in Greenville, South Carolina

Greenville (; locally ) is a city in and the seat of Greenville County, South Carolina, United States. With a population of 70,720 at the 2020 census, it is the sixth-largest city in the state. Greenville is located approximately halfway be ...

, and in 1924 (spelled "Phyllis") in Minneapolis

Minneapolis () is the largest city in Minnesota, United States, and the county seat of Hennepin County. The city is abundant in water, with thirteen lakes, wetlands, the Mississippi River, creeks and waterfalls. Minneapolis has its origins ...

, Minnesota.

On July 16, 2019, at the London site where A. Bell Booksellers published Wheatley's first book in September 1773 (8 Aldgate

Aldgate () was a gate in the former defensive wall around the City of London. It gives its name to Aldgate High Street, the first stretch of the A11 road, which included the site of the former gate.

The area of Aldgate, the most common use of ...

, now the location of the Dorsett City Hotel), the unveiling took place of a commemorative blue plaque honoring her, organized by the Nubian Jak Community Trust

Nubian Jak Community Trust (NJCT) is a commemorative plaque and sculpture scheme founded by Jak Beula that highlights the historic contributions of Black and minority ethnic people in Britain. The first NJCT heritage plaque, honouring Bob Marley, ...

and Black History Walks.

Wheatley is the subject of a project and play by British-Nigerian writer Ade Solanke

Adeola Solanke FRSA, commonly known as Ade Solanke, is a British-Nigerian playwright and screenwriter. She is best known for her debut stage play, ''Pandora's Box'', which was produced at the Arcola Theatre in 2012, and was nominated as Best N ...

entitled ''Phillis in London'', which was showcased at the Greenwich

Greenwich ( , ,) is a town in south-east London, England, within the ceremonial county of Greater London. It is situated east-southeast of Charing Cross.

Greenwich is notable for its maritime history and for giving its name to the Greenwich ...

Book Festival in June 2018.News, University of Greenwich, June 14, 2018.

See also

*African-American literature

African American literature is the body of literature produced in the United States by writers of African descent. It begins with the works of such late 18th-century writers as Phillis Wheatley. Before the high point of slave narratives, African ...

* AALBC.com

* Elijah McCoy

Elijah J. McCoy (May 2, 1844 – October 10, 1929) was a Canadian-American engineer of African-American descent who invented lubrication systems for steam engines. Born free on the Ontario shore of Lake Erie to parents who fled enslavem ...

* List of 18th-century British working-class writers

This list focuses on published authors whose working-class status or background was part of their literary reputation. These were, in the main, writers without access to formal education, so they were either autodidacts or had mentors or patron ...

* Phillis Wheatley Club

The Phillis Wheatley Clubs (also Phyllis Wheatley Club) are women's clubs created by African Americans starting in the late 1800s. The first club was founded in Nashville, Tennessee, in 1895. Some clubs are still active. The purpose of Phillis W ...

* Slave narrative

The slave narrative is a type of literary genre involving the (written) autobiographical accounts of enslaved Africans, particularly in the Americas. Over six thousand such narratives are estimated to exist; about 150 narratives were published as s ...

References

Further reading

; Primary materials * Wheatley, Phillis (1988). John C. Shields, ed. ''The Collected Works of Phillis Wheatley''. New York: Oxford University Press. * Wheatley, Phillis (2001). Vincent Carretta, ed. ''Complete Writings''. New York: Penguin Books. ; Biographies * Borland, (1968). ''Phillis Wheatley: Young Colonial Poet''. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill. * Carretta, Vincent (2011). ''Phillis Wheatley: Biography of A Genius in Bondage'' Athens: University of Georgia Press. * Gates, Henry Louis Jr. (2003). ''The Trials of Phillis Wheatley: America's First Black Poet and Her Encounters With the Founding Fathers,'' New York: Basic Civitas Books. * Richmond, M. A. (1988). ''Phillis Wheatley''. New York: Chelsea House Publishers. ; Secondary materials * Abcarian, Richard and Marvin Klotz. "Phillis Wheatley," In ''Literature: The Human Experience'', 9th edition. New York: Bedford/St. Martin's, 2006: p. 1606. * Barker-Benfield, Graham J. ''Phillis Wheatley Chooses Freedom: History, Poetry, and the Ideals of the American Revolution'' (NYU Press, 2018). * Bassard, Katherine Clay (1999). ''Spiritual Interrogations: Culture, Gender, and Community in Early African American Women's Writing''. Princeton: Princeton University Press. * Chowdhury, Rowshan Jahan. "Restriction, Resistance, and Humility: A Feminist Approach to Anne Bradstreet and Phillis Wheatley’s Literary Works." ''Crossings'' 10 (2019) 47–5online

* Engberg, Kathrynn Seidler, ''The Right to Write: The Literary Politics of Anne Bradstreet and Phillis Wheatley''. Washington, D.C.: University Press of America, 2009. * Langley, April C. E. (2008). ''The Black Aesthetic Unbound: Theorizing the Dilemma of Eighteenth-century African American Literature''. Columbus: Ohio State University Press. * Ogude, S. E. (1983). ''Genius in Bondage: A Study of the Origins of African Literature in English''. Ile-Ife, Nigeria: University of Ife Press. * Reising, Russel J. (1996). ''Loose Ends: Closure and Crisis in the American Social Text''. Durham: Duke University Press. * Robinson, William Henry (1981). ''Phillis Wheatley: A Bio-bibliography''. Boston: GK Hall. * Robinson, William Henry (1982). ''Critical Essays on Phillis Wheatley''. Boston: GK Hall. * Robinson, William Henry (1984). ''Phillis Wheatley and Her Writings''. New York: Garland. * Shockley, Ann Allen (1988). ''Afro-American Women Writers, 1746–1933: An Anthology and Critical Guide''. Boston: GK Hall. * Waldstreicher, David. "The Wheatleyan Moment." ''Early American Studies'' (2011): 522–551

online

* Waldstreicher, David. "Ancients, Moderns, and Africans: Phillis Wheatley and the Politics of Empire and Slavery in the American Revolution." ''Journal of the Early Republic'' 37.4 (2017): 701–733

online

* Zuck, Rochelle Raineri. "Poetic Economics: Phillis Wheatley and the Production of the Black Artist in the Early Atlantic World." ''Ethnic Studies Review'' 33.2 (2010): 143–16

online

; Poetry (inspired by Wheatley) * Clarke, Alison (2020). ''Phillis''. University of Calgary Press. * Jeffers, Honorée Fanonne (2020). ''The Age of Phillis''.

Wesleyan University Press

Wesleyan University Press is a university press that is part of Wesleyan University in Middletown, Connecticut. The press is currently directed by Suzanna Tamminen, a published poet and essayist.

History and overview

Founded (in its present for ...

.

External links

* * * * *"Phillis Wheatley"

National Women's History Museum

Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library

Emory University

Phillis Wheatley collection, 1757–1773

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Wheatley, Phillis 1753 births 1784 deaths Deaths in childbirth American women poets American people of Senegalese descent American people of Gambian descent American Congregationalists Cultural history of Boston Writers from Boston People of colonial Massachusetts People of Massachusetts in the American Revolution African-American women writers African-American poets Colonial American poets 18th-century American poets People from colonial Boston African-American Christians 18th-century American women writers Free Negroes Black Patriots 18th-century African-American women Literate American slaves Colonial American expatriates in Great Britain