Philip The Arab And Christianity on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Philip the Arab and Rival Claimants of the later 240s

, ''De Imperatoribus Romanus'' (1999), citing ''Inscriptiones Latinae Selectae'

1331

Accessed 6 December 2009. The early details of Philip's career are obscure, but his brother,

Tertullian

Accessed 15 August 2009. :*Rolfe, J.C., trans. ''History''. 3 vols. Loeb ed. London: Heinemann, 1939–52. Online a

Accessed 15 August 2009. :*Hamilton, Walter, trans. ''The Later Roman Empire (A.D. 354–378)''. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1986.

Latin Library

Accessed 10 October 2009. :*Bird, H.W., trans. ''Liber de Caesaribus of Sextus Aurelius Victor''. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 1994. *''Chronicon Paschale''. :*Dindorf, L.A., ed. Bonn, 1832. Volum

12

online at Google Books. Accessed 6 October 2009. *Cyprian. :*''Epistulae'' (''Letters''). ::*Migne, J.P., ed. ''S. Thascii Cæcilii Cypriani episcopi carthaginensis et martyris'' (in Latin). ''Patrologia Latina'' 4. Paris, 1897. Online a

Accessed 7 November 2009. ::* Wallis, Robert Ernest, trans. ''Epistles of Cyprian of Carthage''. From ''Ante-Nicene Fathers'', Vol. 5. Edited by Alexander Roberts, James Donaldson, and A. Cleveland Coxe. Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1886. Revised and edited for New Advent by Kevin Knight. Online a

an

Accessed 1 November 2009. *Eusebius of Caesarea. :*''Historia Ecclesiastica'' (''Church History'') first seven books ''ca''. 300, eighth and ninth book ''ca''. 313, tenth book ''ca''. 315, epilogue ''ca''. 325. ::*Migne, J.P., ed. ''Eusebiou tou Pamphilou, episkopou tes en Palaistine Kaisareias ta euriskomena panta'' (in Greek). ''Patrologia Graeca'' 19–24. Paris, 1857. Online a

Khazar Skeptik

an

Accessed 4 November 2009. ::*McGiffert, Arthur Cushman, trans. ''Church History''. From ''Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers'', Second Series, Vol. 1. Edited by Philip Schaff and Henry Wace. Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1890. Revised and edited for New Advent by Kevin Knight. Online a

an

Accessed 28 September 2009. ::*Williamson, G.A., trans. ''Church History''. London: Penguin, 1989. :*''Laudes Constantini'' (''In Praise of Constantine'') 335. ::*Migne, J.P., ed. ''Eusebiou tou Pamphilou, episkopou tes en Palaistine Kaisareias ta euriskomena panta'' (in Greek). ''Patrologia Graeca'' 19–24. Paris, 1857. Online a

Khazar Skeptik

Accessed 4 November 2009. ::* Richardson, Ernest Cushing, trans. ''Oration in Praise of Constantine''. From ''Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers'', Second Series, Vol. 1. Edited by Philip Schaff and Henry Wace. Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1890. Revised and edited for New Advent by Kevin Knight. Online a

an

Accessed 19 October 2009. :*''Vita Constantini'' (''The Life of the Blessed Emperor Constantine'') ''ca''. 336–39. ::*Migne, J.P., ed. ''Eusebiou tou Pamphilou, episkopou tes en Palaistine Kaisareias ta euriskomena panta'' (in Greek). ''Patrologia Graeca'' 19–24. Paris, 1857. Online a

Khazar Skeptik

Accessed 4 November 2009. ::* Richardson, Ernest Cushing, trans. ''Life of Constantine''. From ''Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers'', Second Series, Vol. 1. Edited by Philip Schaff and Henry Wace. Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1890. Revised and edited for New Advent by Kevin Knight. Online a

an

Accessed 9 June 2009. *Jerome. :*''Chronicon'' (''Chronicle'') ''ca''. 380. ::*Fotheringham, John Knight, ed. ''The Bodleian Manuscript of Jerome's Version of the Chronicle of Eusebius''. Oxford: Clarendon, 1905. Online at th

Internet Archive

Accessed 8 October 2009. ::*Pearse, Roger, ''et al''., trans. ''The Chronicle of St. Jerome'', in ''Early Church Fathers: Additional Texts''. Tertullian, 2005. Online a

Accessed 14 August 2009. :*''de Viris Illustribus'' (''On Illustrious Men'') 392. ::*Herding, W., ed. ''De Viris Illustribus'' (in Latin). Leipzig: Teubner, 1879. Online a

Google Books

Accessed 6 October 2009. ::*''Liber de viris inlustribus'' (in Latin). ''Texte und Untersuchungen'' 14. Leipzig, 1896. ::*Richardson, Ernest Cushing, trans. ''De Viris Illustribus (On Illustrious Men)''. From ''Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers'', Second Series, Vol. 3. Edited by Philip Schaff and Henry Wace. Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1892. Revised and edited for New Advent by Kevin Knight. Online a

an

Accessed 15 August 2009. :*''Epistulae'' (''Letters''). ::*Fremantle, W.H., G. Lewis and W.G. Martley, trans. ''Letters''. From ''Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers'', Second Series, Vol. 6. Edited by Philip Schaff and Henry Wace. Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1893. Revised and edited for New Advent by Kevin Knight. Online a

an

Accessed 19 October 2009. *John Chrysostom. ''de S. Babyla'' (''On St. Babylas'') ''ca''. 382. :*Migne, J.P., ed. ''S.P.N. Joannis Chrysostomi, Operae Omnia Quæ Exstant'' (in Greek). 2.1. ''Patrologia Graeca'' 50. Paris, 1862. Online a

Google Books

Accessed 6 October 2009. :*Brandram, T.P., trans. ''On the Holy Martyr, S. Babylas''. From ''Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers'', Second Series, Vol. 9. Edited by Philip Schaff and Henry Wace. Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1889. Revised and edited for New Advent by Kevin Knight. Online a

an

Accessed 8 October 2009. *Jordanes. ''De summa temporum vel origine actibusque gentis Romanorum''. ''Ca''. 551. :*Mommsen, T., ed. ''Monumenta Germaniae Historica'' (in Latin). ''Auctores Antiquissimi'' 5.1. Berlin, 1882. Online at and th

Accessed 8 October 2009. *Lactantius. ''Divinae Institutiones'' (''Divine Institutes''). :*Brandt, Samuel and Georg Laubmann, eds. ''L. Caeli Firmiani Lactanti Opera Omnia'' vol. 1. ''Corpus Scriptorum Ecclesiasticorum Latinorum'' 19. Vienna: F. Tempsky, 1890. Online at th

Internet Archive

Accessed 30 January 2010. :*Fletcher, William, trans. ''The Divine Institutes''. From ''Ante-Nicene Fathers'', Vol. 7. Edited by Alexander Roberts, James Donaldson, and A. Cleveland Coxe. Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1886. Revised and edited for New Advent by Kevin Knight. Online a

an

Accessed 30 January 2010. *''Liber Pontificalis'' (''Book of Popes''). :*Loomis, L.R., trans. ''The Book of Popes''. New York: Columbia University Press, 1916. Online at th

Internet Archive

Accessed 4 November 2009. *''Monumenta Germaniae Historica'' (in Latin). Mommsen, T., ed. ''Auctores Antiquissimi'' 5, 9, 11, 13. Berlin, 1892, 1894. Online at the . Accessed 8 October 2009. *''Oracula Sibyllina''. :*Alexandre, Charles, ed. ''Oracula sibyllina'' (in Greek). Paris: Firmin Didot Fratres, 1869. Online a

Google Books

Accessed 8 October 2009. *Origen. ''Contra Celsum'' (''Against Celsus'') ''ca''. 248. :*Migne, J.P., ed. ''Origenous ta euriskomena panta'' (in Greek). ''Patrologia Graeca'' 11–17. Paris, 1857–62. Online a

Khazar Skeptik

Accessed 4 November 2009. :*Crombie, Frederick, trans. From ''Ante-Nicene Fathers'', Vol. 4. Edited by Alexander Roberts, James Donaldson, and A. Cleveland Coxe. (Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1885.) Revised and edited for New Advent by Kevin Knight. Online a

an

Accessed 1 November 2009. *''Origo Constantini Imperatoris''. :*Rolfe, J.C., trans. ''Excerpta Valesiana'', in vol. 3 of Rolfe's translation of Ammianus Marcellinus' ''History''. Loeb ed. London: Heinemann, 1952. Online a

Accessed 16 August 2009. :*Stevenson, Jane, trans. ''The Origin of Constantine''. In Samuel N. C. Lieu and

Google Books

Accessed 9 October 2009. :*Zangemeister, K.F.W., ed. ''Historiarum Adversum Paganos Libri VII''. Teubner ed. Leipzig, 1889. Online at the Internet Archive

12

Revised and edited for Attalus by Max Bänziger. Online a

Accessed 8 October 2009. :*Unknown trans. ''A History against the Pagans''. Online a

Demon Tortoise

Accessed 4 November 2009. *Philostorgius. ''Historia Ecclesiastica''. :*Walford, Edward, trans. ''Epitome of the Ecclesiastical History of Philostorgius, Compiled by Photius, Patriarch of Constantinople''. London: Henry G. Bohn, 1855. Online a

Accessed 15 August 2009. *''Scriptores Historiae Augustae'' (Authors of the Historia Augusta). ''Historia Augusta'' (''Augustan History''). :*Magie, David, trans. ''Historia Augusta''. 3 vols. Loeb ed. London: Heinemann, 1921–32. Online a

Accessed 26 August 2009. :*Birley, Anthony R., trans. ''Lives of the Later Caesars''. London: Penguin, 1976. *Tertullian. ''De Spectaculis''. :*Thelwall, S., trans. ''The Shows''. From ''Ante-Nicene Fathers'', Vol. 3. Edited by Alexander Roberts, James Donaldson, and A. Cleveland Coxe. Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1885. Revised and edited for New Advent by Kevin Knight. Online a

an

Accessed 9 October 2009. *Vincent of Lérins. :*Migne, J.P., ed. ''S. Vincentii Lirensis, Commonitorum Primum (Ex editione Baluziana)''. ''Patrologia Latina'' 50. Paris, 1874. Online a

Accessed 6 October 2009. :*Heurtley, C.A., trans. ''Against The Profane Novelties Of All Heresies''. From ''Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers'', Second Series, Vol. 11. Edited by Philip Schaff and Henry Wace. Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1894. Revised and edited for New Advent by Kevin Knight. Online a

an

Accessed 6 October 2009. *Zonaras. ''Annales'' (''Annals''). :*Migne, J.P., ed. ''Ioannou tou Zonara ta euriskomena panta: historica, canonica, dogmatica'' (in Greek). ''Patrologia Graeca'' 134–35. Paris, 1864–87. Online a

Khazar Skeptik

Accessed 4 November 2009. :*Niebhur, B.G., ed. ''Ioannes Zonaras Annales'' (in Greek and Latin). ''Corpus Scriptorum Historiae Byzantinae''. Bonn, 1844. Book

online at Documenta Catholica Omnia. Accessed 9 October 2009. *Zosimus. ''Historia Nova'' (''New History''). :*Unknown, trans. ''The History of Count Zosimus''. London: Green and Champlin, 1814. Online a

Accessed 15 August 2009. n unsatisfactory edition.

Google Books

Accessed 10 October 2009. *Allard, Paul. ''Le christianisme et l'empire romain: de Néron a Théodose'' (in French). 2nd ed. Paris: Victor Lecoffre, 1897. Online at th

Internet Archive

Accessed 10 October 2009. *Ball, Warwick. ''Rome in the East: The transformation of an empire''. London: Routledge, 2000. *Barnes, Timothy D. "Legislation against the Christians". ''Journal of Roman Studies'' 58:1–2 (1968): 32–50. *Barnes, Timothy D. ''Constantine and Eusebius''. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1981. *Bowersock, Glen W. Review of Irfan Shahîd's ''Rome and the Arabs'' and ''Byzantium and the Arabs in the Fourth Century''. ''The Classical Review'' 36:1 (1986): 111–17. *Bowersock, Glen W. ''Roman Arabia''. 3rd ed. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1994. *Cameron, Averil. "Education and literary culture." In ''The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume XIII: The Late Empire, A.D. 337–425'', edited by Averil Cameron and Peter Garnsey, 665–707. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998. *Clarke, Graeme. "Third-Century Christianity." In ''The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume XII: The Crisis of Empire'', edited by Alan Bowman, Averil Cameron, and Peter Garnsey, 589–671. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005. *Dagron, G. ''Emperor and Priest: the Imperial Office in Byzantium''. Cambridge University Press, 2007, *Drake, H. A. ''Constantine and the Bishops: The Politics of Intolerance''. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000. *Elliott, T. G. ''The Christianity of Constantine the Great''. Scranton, PA: University of Scranton Press, 1996. *Frend, W. H. C. ''Martyrdom and Persecution in the Early Church''. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Book House, 1981 ept. of Basil Blackwell, 1965 ed. *Frend, W. H. C. ''The Rise of Christianity''. Philadelphia, PA: Fortress Press, 1984. *Frend, W. H. C. "Persecutions: Genesis and Legacy." In ''The Cambridge History of Christianity, Volume I: Origins to Constantine'', edited by Margaret M. Mitchell and Frances M. Young, 503–523. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006. *Gibbon, Edward. ''

The Online Library of Liberty

Accessed 23 October 2009.] *Goffart, Walter. "Zosimus, The First Historian of Rome's Fall". ''American Historical Review'' 76:2 (1971): 412–41. *Gregg, John A. F. ''The Decian Persecution''. Edinburgh and London: W. Blackwood & Sons, 1897. Online at th

Internet Archive

Accessed 8 October 2009 *Gwatkin, H. M. ''Early Church History to A.D. 313''. 2 vols. 2nd ed. London: Macmillan, 1912. Vols

12

online at the Internet Archive. Accessed 9 October 2009. *Jones, A. H. M. ''The Cities of the Eastern Roman Provinces''. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1937. *Kidd, B. J. ''A History of the Church to A.D. 461''. 3 vols. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1922. *Lane Fox, Robin. ''Pagans and Christians''. London: Penguin, 1986. *Lieu, Samuel N. C., and Dominic Montserrat. ''From Constantine to Julian: Pagan and Byzantine Views''. New York: Routledge, 1996. *Louth, Andrew. "Introduction". In ''Eusebius: The History of the Church from Christ to Constantine'', translated by G. A. Williamson, edited and revised by Andrew Louth, ix–xxxv. London: Penguin, 1989. *Millar, Fergus. ''The Roman Near East: 31 BC – AD 337''. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1993. *Neale, John Mason. ''A History of the Holy Eastern Church: The Patriarchate of Antioch''. London: Rivingtons, 1873. *Peachin, Michael. "Philip's Progress: From Mesopotamia to Rome in A.D. 244". ''Historia'' 40:3 (1991): 331–42. *Pohlsander, Hans A. "Philip the Arab and Christianity". ''Historia'' 29:4 (1980): 463–73. *Pohlsander, Hans A. "Did Decius Kill the Philippi?" ''Historia'' 31:2 (1982): 214–22. *Potter, David. ''The Roman Empire at Bay: AD 180–395''. New York: Routledge, 2004. *Quasten, Johannes. ''Patrology''. 4 vols. Westminster, MD: Newman Press, 1950–1986. *Rives, J. B. "The Decree of Decius and the Religion of Empire". ''Journal of Roman Studies'' 89 (1999): 135–54. *de Sainte-Croix, G. E. M. "Why Were the Early Christians Persecuted?" ''Past & Present'' 26 (1963): 6–38. * Shahîd, Irfan. ''Rome and the Arabs: A Prolegomenon to the Study of Byzantium and the Arabs''. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks, 1984. *Shahîd, Irfan. ''Byzantium and the Arabs in the Fourth Century''. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks, 1984. *Tillemont, Louis-Sébastien le Nain. ''Histoire des Empereurs'', vol. 3: ''Qui Comprend Depuis Severe juſques à l'election de Diocletien'' (in French). New ed. Paris: Charles Robustel, 1720. Online a

Google Books

Accessed 22 October 2009. *Trombley, Frank R. ''Hellenic Religion and Christianization c. 370–529''. 2 vols. Boston: E. J. Brill, 1995. *York, John M. "The Image of Philip the Arab". ''Historia'' 21:2 (1972): 320–32. {{DEFAULTSORT:Philip The Arab And Christianity 3rd-century Arabs Philip the Arab

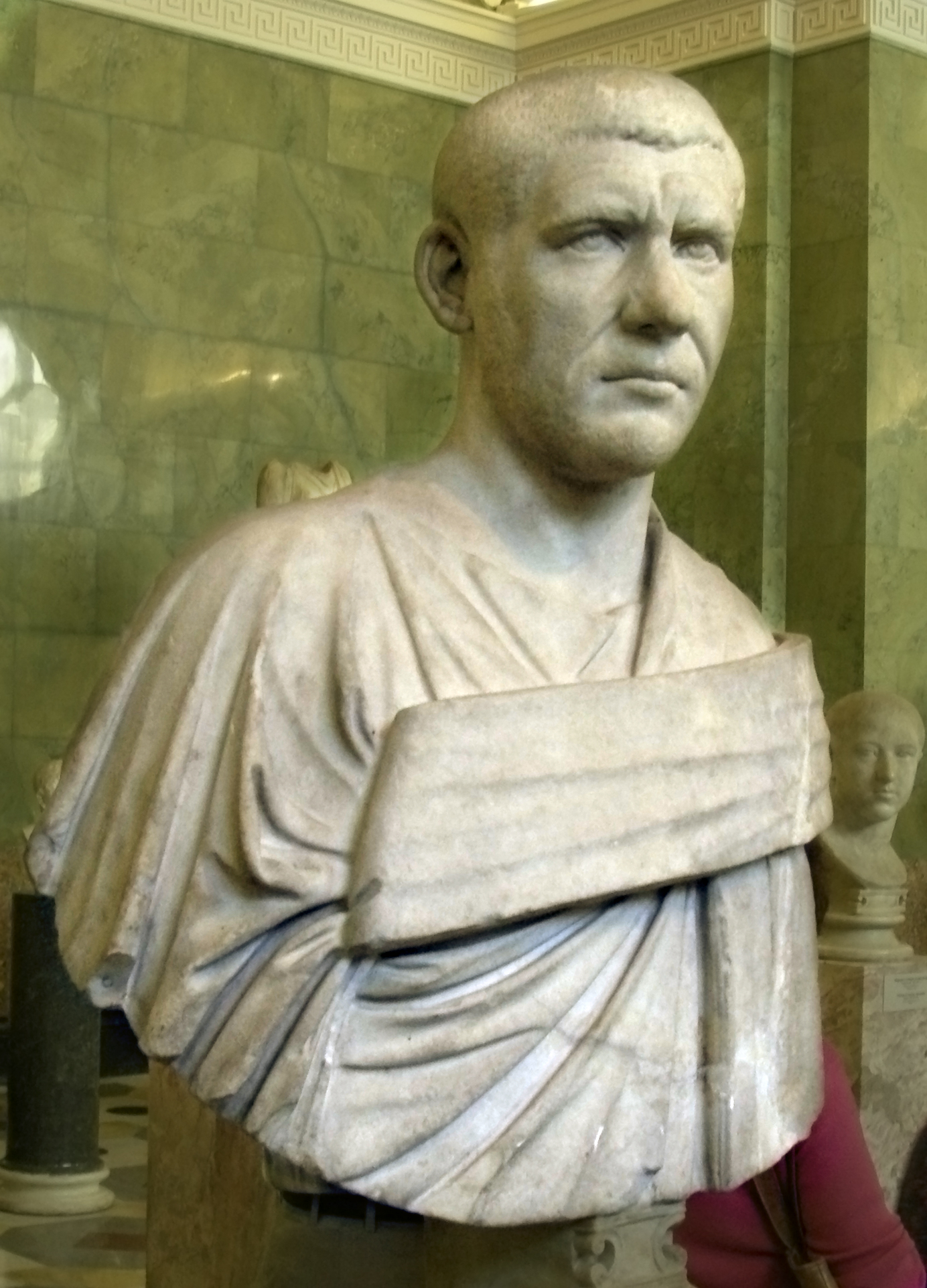

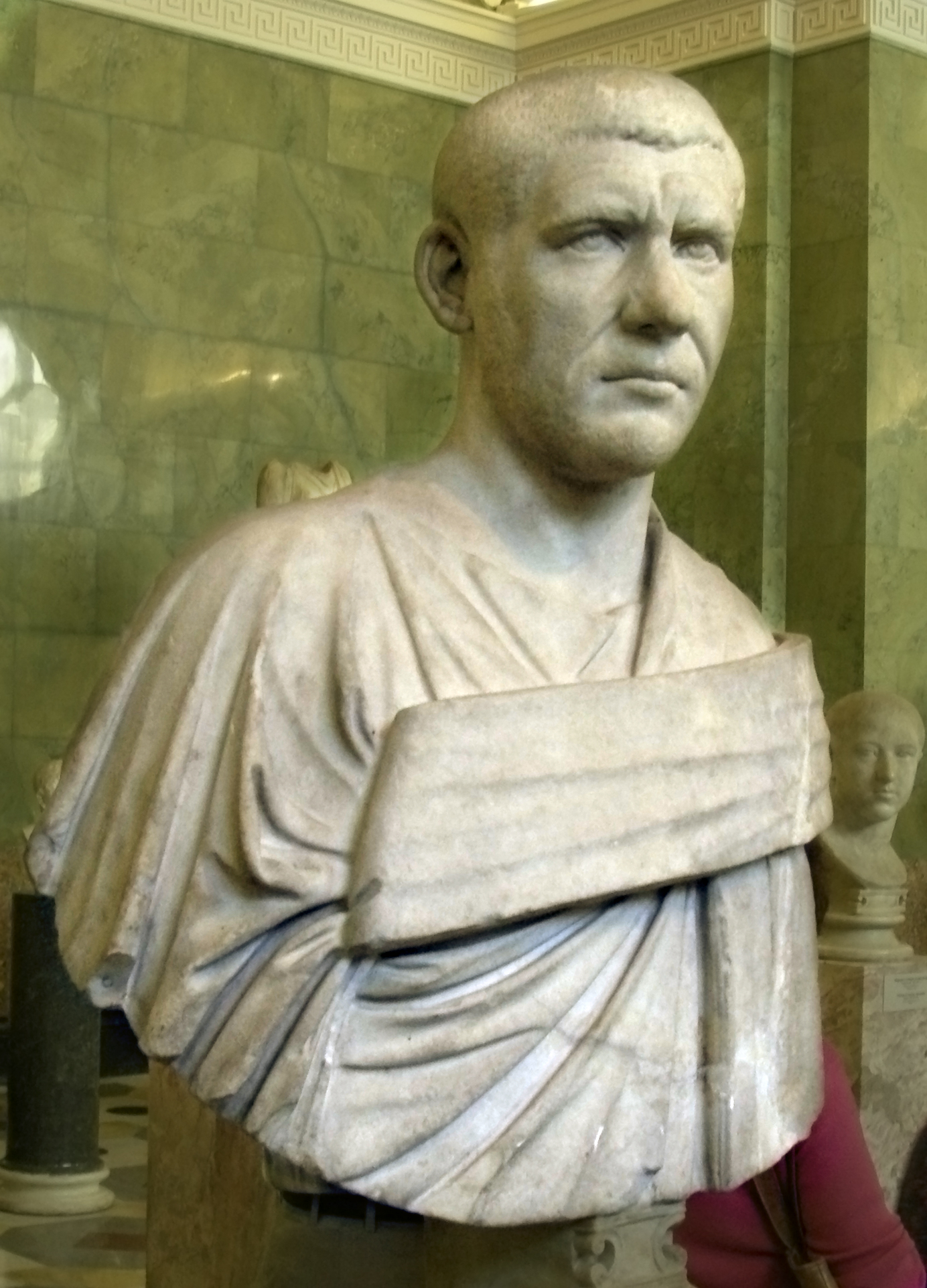

Philip the Arab

Philip the Arab ( la, Marcus Julius Philippus "Arabs"; 204 – September 249) was Roman emperor from 244 to 249. He was born in Aurantis, Arabia, in a city situated in modern-day Syria. After the death of Gordian III in February 244, Philip ...

was one of the few 3rd-century Roman emperors sympathetic to Christians, although his relationship with Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global pop ...

is obscure and controversial. Philip was born in Auranitis

The Hauran ( ar, حَوْرَان, ''Ḥawrān''; also spelled ''Hawran'' or ''Houran'') is a region that spans parts of southern Syria and northern Jordan. It is bound in the north by the Ghouta oasis, eastwards by the al-Safa field, to the so ...

, an Arab district east of the Sea of Galilee

The Sea of Galilee ( he, יָם כִּנֶּרֶת, Judeo-Aramaic: יַמּא דטבריא, גִּנֵּיסַר, ar, بحيرة طبريا), also called Lake Tiberias, Kinneret or Kinnereth, is a freshwater lake in Israel. It is the lowest ...

. The urban and Hellenized centers of the region were Christianized in the early years of the 3rd century via major Christian centers at Bosra

Bosra ( ar, بُصْرَىٰ, Buṣrā), also spelled Bostra, Busrana, Bozrah, Bozra and officially called Busra al-Sham ( ar, بُصْرَىٰ ٱلشَّام, Buṣrā al-Shām), is a town in southern Syria, administratively belonging to the Dara ...

and Edessa

Edessa (; grc, Ἔδεσσα, Édessa) was an ancient city (''polis'') in Upper Mesopotamia, founded during the Hellenistic period by King Seleucus I Nicator (), founder of the Seleucid Empire. It later became capital of the Kingdom of Osroene ...

, but there is little evidence of Christian presence in the small villages of the region in this period, such as Philip's birthplace at Philippopolis. Philip served as praetorian prefect

The praetorian prefect ( la, praefectus praetorio, el, ) was a high office in the Roman Empire. Originating as the commander of the Praetorian Guard, the office gradually acquired extensive legal and administrative functions, with its holders be ...

, commander of the Praetorian Guard

The Praetorian Guard (Latin: ''cohortēs praetōriae'') was a unit of the Imperial Roman army that served as personal bodyguards and intelligence agents for the Roman emperors. During the Roman Republic, the Praetorian Guard were an escort fo ...

, from 242; he was made emperor in 244. In 249, after a brief civil war, he was killed at the hands of his successor, Decius

Gaius Messius Quintus Traianus Decius ( 201 ADJune 251 AD), sometimes translated as Trajan Decius or Decius, was the emperor of the Roman Empire from 249 to 251.

A distinguished politician during the reign of Philip the Arab, Decius was procla ...

.

During the late 3rd century and into the 4th, it was held by some churchmen that Philip

Philip, also Phillip, is a male given name, derived from the Greek (''Philippos'', lit. "horse-loving" or "fond of horses"), from a compound of (''philos'', "dear", "loved", "loving") and (''hippos'', "horse"). Prominent Philips who popularize ...

had been the first Christian emperor; he was described as such in Jerome

Jerome (; la, Eusebius Sophronius Hieronymus; grc-gre, Εὐσέβιος Σωφρόνιος Ἱερώνυμος; – 30 September 420), also known as Jerome of Stridon, was a Christian presbyter, priest, Confessor of the Faith, confessor, th ...

's ''Chronicon In historiography, a ''chronicon'' is a type of chronicle or annals. Examples are:

* ''Chronicon'' (Eusebius)

* ''Chronicon'' (Jerome)

*''Chronicon Abbatiae de Evesham''

*'' Chronicon Burgense''

*'' Chronicon Ambrosianum''

*''Chronicon Compostellan ...

'' (''Chronicle''), which was well known during the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

, and in Paulus Orosius

Paulus Orosius (; born 375/385 – 420 AD), less often Paul Orosius in English, was a Roman priest, historian and theologian, and a student of Augustine of Hippo. It is possible that he was born in ''Bracara Augusta'' (now Braga, Portugal), th ...

' highly popular ''Historia Adversus Paganos'' (''History Against the Pagans''). Most scholars hold that these and other early accounts ultimately derive from Eusebius of Caesarea

Eusebius of Caesarea (; grc-gre, Εὐσέβιος ; 260/265 – 30 May 339), also known as Eusebius Pamphilus (from the grc-gre, Εὐσέβιος τοῦ Παμφίλου), was a Greek historian of Christianity, exegete, and Christia ...

's ''Historia Ecclesiastica'' ( ''Church History'').E.g., Gregg, 43; Pohlsander, "Philip the Arab and Christianity", 466; E. Stein ''apud'' Shahîd, ''Rome and the Arabs'', 69.

The most important section of Eusebius' ''Historia'' on Philip's religious beliefs describes the emperor's visit to a church on Easter Eve

Holy Saturday ( la, Sabbatum Sanctum), also known as Great and Holy Saturday (also Holy and Great Saturday), the Great Sabbath, Hallelujah Saturday (in Portugal and Brazil), Saturday of the Glory, Sabado de Gloria, and Black Saturday or Easter ...

when he was denied entry by the presiding bishop until he confessed his sins. The account is paralleled by John Chrysostom

John Chrysostom (; gr, Ἰωάννης ὁ Χρυσόστομος; 14 September 407) was an important Early Church Father who served as archbishop of Constantinople. He is known for his homilies, preaching and public speaking, his denunciat ...

's homily, which celebrates Saint Babylas

Babylas ( el, Βαβύλας) (died 253) was a patriarch of Antioch (237–253), who died in prison during the Decian persecution. In the Eastern Orthodox Church and Eastern Catholic Churches of the Byzantine rite his feast day is September 4, i ...

, Bishop of Antioch, for denying a sinful emperor entry to his church; and quotations of Leontius in the ''Chronicon Paschale

''Chronicon Paschale'' (the ''Paschal'' or ''Easter Chronicle''), also called ''Chronicum Alexandrinum'', ''Constantinopolitanum'' or ''Fasti Siculi'', is the conventional name of a 7th-century Greek Christian chronicle of the world. Its name com ...

'' which describe Philip seeking penitence from Babylas for the sin of murdering his predecessor. Given the parallels between the accounts, most scholars believe that Eusebius, Chrysostom, and Leontius are referring to the same event.

With the growth of scholarly criticism in the 17th and 18th centuries, fewer historians believed Philip to be a Christian. Historians had become increasingly aware of secular texts, which did not describe Philip as a Christian—and which, indeed, recorded him participating as '' pontifex maximus'' (chief priest) over the millennial Secular Games

The Saecular Games ( la, Ludi saeculares, originally ) was a Roman religious celebration involving sacrifices and theatrical performances, held in ancient Rome for three days and nights to mark the end of a and the beginning of the next. A , sup ...

in 248. Modern scholars are divided on the issue. Some, like Hans Pohlsander and Ernst Stein, argue that the ecclesiastic narratives are ambiguous, based on oral rumor, and do not vouch for a Christian Philip; others, like John York, Irfan Shahîd

Irfan Arif Shahîd ( ar, عرفان عارف شهيد ; Nazareth, Mandatory Palestine, January 15, 1926 – Washington, D.C., November 9, 2016), born as Erfan Arif Qa'war (), was a scholar in the field of Oriental studies. He was from 1982 unti ...

, and Warwick Ball

Warwick Ball is an Australia-born Near-Eastern archaeologist.

Ball has been involved in excavations, architectural studies and monumental restorations in Jordan, Iran, Iraq, Syria, Ethiopia and Afghanistan. As a lecturer, he has been involved wit ...

, argue that the ecclesiastic narratives are clear and dependable enough that Philip can be described as a Christian; still others, like Glen Bowersock

Glen Warren Bowersock (born January 12, 1936 in Providence, Rhode Island) is a historian of ancient Greece, Rome and the Near East, and former Chairman of Harvard’s classics department.

Early life

Bowersock was born in Providence, Rhode Island a ...

, argue that the sources are strong enough to describe Philip as a man interested in and sympathetic to Christianity, but not strong enough to call him a Christian.

Background

Biography of Philip the Arab

Philip was born in a village inAuranitis

The Hauran ( ar, حَوْرَان, ''Ḥawrān''; also spelled ''Hawran'' or ''Houran'') is a region that spans parts of southern Syria and northern Jordan. It is bound in the north by the Ghouta oasis, eastwards by the al-Safa field, to the so ...

, part of the district of Trachonitis

The Lajat (/ALA-LC: ''al-Lajāʾ''), also spelled ''Lejat'', ''Lajah'', ''el-Leja'' or ''Laja'', is the largest lava field in southern Syria, spanning some 900 square kilometers. Located about southeast of Damascus, the Lajat borders the Hauran ...

, east of the Sea of Galilee

The Sea of Galilee ( he, יָם כִּנֶּרֶת, Judeo-Aramaic: יַמּא דטבריא, גִּנֵּיסַר, ar, بحيرة طبريا), also called Lake Tiberias, Kinneret or Kinnereth, is a freshwater lake in Israel. It is the lowest ...

in Palestine

__NOTOC__

Palestine may refer to:

* State of Palestine, a state in Western Asia

* Palestine (region), a geographic region in Western Asia

* Palestinian territories, territories occupied by Israel since 1967, namely the West Bank (including East ...

. Philip renamed the village Philippopolis (the modern al-Shahbā', Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

) during his reign as emperor. He was one of only three Easterners to be made emperor before the decisive separation of East and West in 395. (The other two were Elagabalus

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (born Sextus Varius Avitus Bassianus, 204 – 11/12 March 222), better known by his nickname "Elagabalus" (, ), was Roman emperor from 218 to 222, while he was still a teenager. His short reign was conspicuous for s ...

and Alexander Severus

Marcus Aurelius Severus Alexander (1 October 208 – 21/22 March 235) was a Roman emperor, who reigned from 222 until 235. He was the last emperor from the Severan dynasty. He succeeded his slain cousin Elagabalus in 222. Alexander himself was ...

). Even among Easterners Philip was atypical, as he was an Arab, not a Greek. His father was Julius Marinus; nothing besides his name is known, but the name indicates that he held Roman citizenship and that he must have been prominent in his community.Michael L. Meckler and Christian Körner,Philip the Arab and Rival Claimants of the later 240s

, ''De Imperatoribus Romanus'' (1999), citing ''Inscriptiones Latinae Selectae'

1331

Accessed 6 December 2009. The early details of Philip's career are obscure, but his brother,

Gaius Julius Priscus

Gaius Julius Priscus (fl. 3rd century) was a Roman soldier and member of the Praetorian Guard in the reign of Gordian III.

Life

Priscus was born in the Roman province of Syria, possibly in Damascus, son of a Julius Marinus a local Roman citizen, ...

, was made praetorian prefect

The praetorian prefect ( la, praefectus praetorio, el, ) was a high office in the Roman Empire. Originating as the commander of the Praetorian Guard, the office gradually acquired extensive legal and administrative functions, with its holders be ...

under Emperor Gordian III

Gordian III ( la, Marcus Antonius Gordianus; 20 January 225 – February 244) was Roman emperor from 238 to 244. At the age of 13, he became the youngest sole emperor up to that point (until Valentinian II in 375). Gordian was the son of Anton ...

(r. 238–44). If a fragmentary inscription (''Inscriptiones Latinae Selectae

''Inscriptiones Latinae Selectae'', standard abbreviation ''ILS'', is a three-volume selection of Latin inscriptions edited by Hermann Dessau. The work was published in five parts serially from 1892 to 1916, with numerous reprints. Supporting mat ...

'' 1331) refers to Priscus, he would have moved through several equestrian offices (that is, administrative positions open to a member of the equestrian order

The ''equites'' (; literally "horse-" or "cavalrymen", though sometimes referred to as "knights" in English) constituted the second of the property-based classes of ancient Rome, ranking below the senatorial class. A member of the equestrian o ...

) during Gordian's reign. In the spring of 242, Philip himself was made praetorian prefect, most likely with the help of his brother. Following a failed campaign against Persia in the winter of 243–44, Gordian died in camp. Rumors that Philip had murdered him were taken up by the senatorial opposition of the later 3rd century, and survive in the Latin histories and epitomes of the period. Philip was acclaimed emperor, and was secure in that title by late winter 244. Philip made his brother ''rector Orientis'', an executive position with extraordinary powers, including command of the armies in the Eastern provinces. Philip began his reign by negotiating a peaceful end to his predecessor's war against Persia. In 248, Philip called the Secular Games

The Saecular Games ( la, Ludi saeculares, originally ) was a Roman religious celebration involving sacrifices and theatrical performances, held in ancient Rome for three days and nights to mark the end of a and the beginning of the next. A , sup ...

to celebrate the 1000-year anniversary of the founding of Rome.

In the Near East, Philip's brother Priscus' tax collection methods provoked the revolt of Jotapianus

Jotapian (; la, Marcus F. Ru. Jotapianus; died ''c.'' 249) was a usurper in the eastern provinces of the Roman Empire during the reign of Emperor Philip the Arab, around 249. Jotapian is known from his rare coins and from accounts in Aurelius V ...

. At the same time, Silbannacus started a rebellion in the Rhenish provinces. He faced a third rebellion in 248 when the legions he had used in successful campaigns against the Carpi

Carpi may refer to:

Places

* Carpi, Emilia-Romagna, a large town in the province of Modena, central Italy

* Carpi (Africa), a city and former diocese of Roman Africa, now a Latin Catholic titular bishopric

People

* Carpi (people), an ancie ...

on the Danubian frontier revolted and proclaimed an officer named Pacatianus

Pacatian (; la, Tiberius Claudius Marinus Pacatianus; died ''c.'' 248) was a usurper in the Danube area of the Roman Empire during the time of Philip the Arab.

He is known from coins, and from mentions in Zosimus and Zonaras, who say that he ...

emperor. All three rebellions were suppressed quickly. In 249, to restore order after the defeat of Pacatianus, Philip gave Senator Decius

Gaius Messius Quintus Traianus Decius ( 201 ADJune 251 AD), sometimes translated as Trajan Decius or Decius, was the emperor of the Roman Empire from 249 to 251.

A distinguished politician during the reign of Philip the Arab, Decius was procla ...

, a native of the region, command of the Danubian armies. In late spring 249, the armies proclaimed Decius emperor. The civil war that followed ended in a battle outside Verona. Decius emerged victorious, and Philip either died or was assassinated. When news of Philip's death reached Rome, the Praetorian Guard

The Praetorian Guard (Latin: ''cohortēs praetōriae'') was a unit of the Imperial Roman army that served as personal bodyguards and intelligence agents for the Roman emperors. During the Roman Republic, the Praetorian Guard were an escort fo ...

murdered his son and successor Marcus Julius Severus Philippus.

Christianity and Philip's early life and career

No account or allusion to Philip's presumed conversion to Christianity survives. The Byzantinist and Arabist Irfan Shahîd, who argues in favor of Philip's Christianity in ''Rome and the Arabs'', assumes that he had been a Christian before becoming emperor. He argues, therefore, that there is no need to explain the absence of evidence for Philip's conversion in contemporary Christian literature. Trachonitis, equidistant from Antioch in the north and Bosra in the south, and sited on a road connecting the two, could have been Christianized from either direction. Even if he was not himself Christian, Philip would probably have been familiar with Christians in his hometown as well as Bosra and other nearby settlements. Hans Pohlsander, a classicist and historian arguing against accounts of Philip's Christianity, allows that Philip "''may have been'' curious about a religion which had its origins in an area so close to his place of birth. As an eastern provincial rather than an Italian, he ''may not have been'' so intense in his commitment to the traditional Roman religion that he could not keep an open mind on other religions." He also accepts that Philippopolis probably contained a Christian congregation during Philip's childhood.Pohlsander, "Philip the Arab and Christianity", 468; the italics are his. Pohlsander points to Alexander Severus andJulia Mamaea

Julia Avita Mamaea or Julia Mamaea (14 or 29 August around 182 – 235) was a Syrian noble woman and member of the Severan dynasty. She was the mother of Roman emperor Alexander Severus and remained one of his chief advisors throughout his ...

, fellow Arabs and Syrians, as examples and precedents for such open-mindedness on religious matters (Pohlsander, "Philip the Arab and Christianity", 468); Glen Bowersock traces this religious curiosity back to Julia Domna

Julia Domna (; – 217 AD) was Roman empress from 193 to 211 as the wife of Emperor Septimius Severus. She was the first empress of the Severan dynasty. Domna was born in Emesa (present-day Homs) in Roman Syria to an Arab family of priests of ...

, Mammaea's aunt (Bowersock, ''Roman Arabia'', 126). For the scholar of religion Frank Trombley, however, the absence of evidence for the early Christianization of Philippopolis makes Shahîd's assumption that Philip was Christian from early childhood unmerited.

If Philip had been a Christian during his military service, he would have not been a particularly unusual figure for his era—although membership in the army was prohibited by certain churchmen, and would have required participation in rites some Christians found sacrilegious, it was not uncommon among the Christian laity. The position of an emperor, however, was more explicitly pagan—emperors were expected to officiate over public rites and lead the religious ceremonies of the army. Christian scripture contains explicit prohibitions on this sort of behavior, such as the First Commandment: "You shall have no other gods before me". Whatever the prohibitions, people raised on the "more tolerant Christianity of the camp"Elliott, 26. would have been able to justify participation in pagan ritual to themselves. Such people did exist: the historical record includes Christian army officers, who would have been regularly guilty of idolatry, and the military martyrs of the late 3rd century. Their ritual sacrifice excluded them from certain parts of the Christian community (ecclesiastical writers tended to ignore them, for example) but these people nonetheless believed themselves to be Christian and were recognized by others as Christians.

Christianity in Auranitis

Thanks to its proximity to the first Christian communities of Palestine, Provincia Arabia, of which Philippopolis was a part, was among the first regions to convert to Christianity. By the time of Philip's birth, the region had been extensively Christianized, especially in the north and in Hellenized settlements like those of Auranitis. The region is known to have had a fully developedsynod

A synod () is a council of a Christian denomination, usually convened to decide an issue of doctrine, administration or application. The word ''wikt:synod, synod'' comes from the meaning "assembly" or "meeting" and is analogous with the Latin ...

al system (in which bishops from the dioceses in the region met to discuss Church affairs) by the mid-3rd century. The region sent six bishops to the Council of Nicaea in 325, and Eusebius' ''Onomasticon'', a gazetteer of Biblical place-names, records a wholly Christian village called Cariathaim, or Caraiatha, near Madaba

Madaba ( ar, مادبا; Biblical Hebrew: ''Mēḏəḇāʾ''; grc, Μήδαβα) is the capital city of Madaba Governorate in central Jordan, with a population of about 60,000. It is best known for its Byzantine and Umayyad mosaics, espec ...

.Clarke, 599. Outside of the cities, however, there is less evidence of Christianization. Before the 5th century there is little evidence of the faith, and many villages remained unconverted in the 6th. Philippopolis, which was a small village for most of this period, does not have a Christian inscription that can be dated earlier than 552. It is not known when the village established a prelate

A prelate () is a high-ranking member of the Christian clergy who is an ordinary or who ranks in precedence with ordinaries. The word derives from the Latin , the past participle of , which means 'carry before', 'be set above or over' or 'pref ...

ship, but it must have been sometime before 451, when it sent a bishop to the Council of Chalcedon

The Council of Chalcedon (; la, Concilium Chalcedonense), ''Synodos tēs Chalkēdonos'' was the fourth ecumenical council of the Christian Church. It was convoked by the Roman emperor Marcian. The council convened in the city of Chalcedon, Bith ...

.

Christian beliefs were present in the region's Arab community since about AD 200, when Abgar VIII

__NOTOC__

Abgar VIII of Edessa, also known as Abgar the Great or Abgar bar Ma'nu, was an Arab king of Osroene from 177-212 CE.

Abgar the Great was most remembered for his alleged conversion to Christianity in about 200 CE and the declaration of ...

, an ethnic Arab and king of the Roman client state

A client state, in international relations, is a state that is economically, politically, and/or militarily subordinate to another more powerful state (called the "controlling state"). A client state may variously be described as satellite state, ...

Osroene

Osroene or Osrhoene (; grc-gre, Ὀσροηνή) was an ancient region and state in Upper Mesopotamia. The ''Kingdom of Osroene'', also known as the "Kingdom of Edessa" ( syc, ܡܠܟܘܬܐ ܕܒܝܬ ܐܘܪܗܝ / "Kingdom of Urhay"), according to ...

, converted to Christianity. The religion was propagated from Abgar's capital at Edessa

Edessa (; grc, Ἔδεσσα, Édessa) was an ancient city (''polis'') in Upper Mesopotamia, founded during the Hellenistic period by King Seleucus I Nicator (), founder of the Seleucid Empire. It later became capital of the Kingdom of Osroene ...

until its destruction in 244. By the mid-3rd century, Bosra

Bosra ( ar, بُصْرَىٰ, Buṣrā), also spelled Bostra, Busrana, Bozrah, Bozra and officially called Busra al-Sham ( ar, بُصْرَىٰ ٱلشَّام, Buṣrā al-Shām), is a town in southern Syria, administratively belonging to the Dara ...

, the capital of Provincia Arabia, had a Christian bishop, Beryllos. Beryllos offers an early example of the heretical beliefs Hellenic Christians imputed to the Arabs as a race: Beryllos believed that Christ did not exist before he was made flesh at the Incarnation

Incarnation literally means ''embodied in flesh'' or ''taking on flesh''. It refers to the conception and the embodiment of a deity or spirit in some earthly form or the appearance of a god as a human. If capitalized, it is the union of divinit ...

. According to Eusebius of Caesarea

Eusebius of Caesarea (; grc-gre, Εὐσέβιος ; 260/265 – 30 May 339), also known as Eusebius Pamphilus (from the grc-gre, Εὐσέβιος τοῦ Παμφίλου), was a Greek historian of Christianity, exegete, and Christia ...

, his views were condemned as heresy following debate at a local synod. The debate was most likely conducted in Greek, a language in common use among the well-Hellenized cities of the region.

Christianity in the mid-3rd century

The 3rd century was the age in which the initiative for persecution shifted from the masses to the Imperial office. In the 1st and 2nd centuries, persecutions were carried out under the authority of local government officials.Septimius Severus

Lucius Septimius Severus (; 11 April 145 – 4 February 211) was Roman emperor from 193 to 211. He was born in Leptis Magna (present-day Al-Khums, Libya) in the Roman province of Africa (Roman province), Africa. As a young man he advanced thro ...

(r. 193–211) and Maximin (r. 235–38) are alleged to have issued general rescripts against the religion and targeted its clergy, but the evidence for their acts is obscure and contested. There is no evidence that Philip effected any changes to the Christians' legal status. Pogrom

A pogrom () is a violent riot incited with the aim of massacring or expelling an ethnic or religious group, particularly Jews. The term entered the English language from Russian to describe 19th- and 20th-century attacks on Jews in the Russia ...

s against the Christians in Alexandria took place while Philip was still emperor. There is no evidence that Philip punished, participated in or assisted the pogrom.

No historian contests that Philip's successor Decius

Gaius Messius Quintus Traianus Decius ( 201 ADJune 251 AD), sometimes translated as Trajan Decius or Decius, was the emperor of the Roman Empire from 249 to 251.

A distinguished politician during the reign of Philip the Arab, Decius was procla ...

(r. 249–51), called a general persecution against the Church, and most would list it as the first. Decius was anxious to secure himself in the imperial office. Before mid-December 249, Decius issued an edict demanding that all Romans, throughout the empire, make a show of sacrifice to the gods. '' Libelli'' were signed in Fayum

Faiyum ( ar, الفيوم ' , borrowed from cop, ̀Ⲫⲓⲟⲙ or Ⲫⲓⲱⲙ ' from egy, pꜣ ym "the Sea, Lake") is a city in Middle Egypt. Located southwest of Cairo, in the Faiyum Oasis, it is the capital of the modern Faiyum ...

in June and July 250 as demonstrations of this sacrifice. If the persecutions of Maximin and Septimius Severus are dismissed as fiction, Decius' edict was without precedent. If the Christians were believed to be Philip's friends (as Dionysius of Alexandria presents them), however, it might help explain Decius' motivations.Lane Fox, 453–54.

In Greek ecclesiastical writing

The ancient traditions regarding Philip'sChristianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global pop ...

can be divided into three categories: the Eusebian, or Caesarean

Caesarean section, also known as C-section or caesarean delivery, is the surgical procedure by which one or more babies are delivered through an incision in the mother's abdomen, often performed because vaginal delivery would put the baby or mo ...

; the Antioch

Antioch on the Orontes (; grc-gre, Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπὶ Ὀρόντου, ''Antiókheia hē epì Oróntou'', Learned ; also Syrian Antioch) grc-koi, Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπὶ Ὀρόντου; or Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπ� ...

ene; and the Latin. The Eusebian tradition consists of Eusebius, bishop of Caesarea's ''Historia Ecclesiastica'' and the documents excerpted and cited therein, including the letters of Origen and Dionysius, bishop of Alexandria. The Antiochene tradition consists of the John Chrysostom

John Chrysostom (; gr, Ἰωάννης ὁ Χρυσόστομος; 14 September 407) was an important Early Church Father who served as archbishop of Constantinople. He is known for his homilies, preaching and public speaking, his denunciat ...

's homily ''de S. Babyla'' and Leontius, bishop of Antioch's entries in the ''Chronicon Paschale

''Chronicon Paschale'' (the ''Paschal'' or ''Easter Chronicle''), also called ''Chronicum Alexandrinum'', ''Constantinopolitanum'' or ''Fasti Siculi'', is the conventional name of a 7th-century Greek Christian chronicle of the world. Its name com ...

''. Most scholars hold that these accounts ultimately derive from Eusebius of Caesarea

Eusebius of Caesarea (; grc-gre, Εὐσέβιος ; 260/265 – 30 May 339), also known as Eusebius Pamphilus (from the grc-gre, Εὐσέβιος τοῦ Παμφίλου), was a Greek historian of Christianity, exegete, and Christia ...

's ''Historia Ecclesiastica'' (Ecclesiastical History

__NOTOC__

Church history or ecclesiastical history as an academic discipline studies the history of Christianity and the way the Christian Church has developed since its inception.

Henry Melvill Gwatkin defined church history as "the spiritual ...

), but some, like Irfan Shahîd, posit that Antioch had an independent oral tradition.

Eusebius

The most significant author to discuss Philip the Arab and Christianity isEusebius

Eusebius of Caesarea (; grc-gre, Εὐσέβιος ; 260/265 – 30 May 339), also known as Eusebius Pamphilus (from the grc-gre, Εὐσέβιος τοῦ Παμφίλου), was a Greek historian of Christianity, exegete, and Christian ...

, who served as bishop of Caesarea

Caesarea () ( he, קֵיסָרְיָה, ), ''Keysariya'' or ''Qesarya'', often simplified to Keisarya, and Qaysaria, is an affluent town in north-central Israel, which inherits its name and much of its territory from the ancient city of Caesare ...

in Roman Palestine from ''ca''. 314 to his death in 339.Shahîd, ''Rome and the Arabs'', 67. Eusebius' major work is the ''Historia Ecclesiastica'', written in several editions dating from ''ca''. 300 to 325. The ''Historia'' is not an attempt at a full history of the Church in the classical style, but rather a collection of facts addressing six topics in Christian history from the Apostolic times to the late 3rd century: (1) lists of bishops of major sees; (2) Christian teachers and their writings; (3) heresies; (4) the tribulations of the Jews; (5) the persecutions of Christians by pagan authorities; and (6) the martyrs. His ''Vita Constantini'', written between Constantine's death in 337 and Eusebius' own death in 339, is a combination of eulogistic encomium

''Encomium'' is a Latin word deriving from the Ancient Greek ''enkomion'' (), meaning "the praise of a person or thing." Another Latin equivalent is ''laudatio'', a speech in praise of someone or something.

Originally was the song sung by the c ...

and continuation of the ''Historia'' (the two separate documents were combined and distributed by Eusebius' successor in the see of Caesarea, Acacius).

Five references in Eusebius' ''Historia Ecclesiastica'' speak to Philip's Christianity; three directly, two by implication. At 6.34, he describes Philip visiting a church on Easter Eve

Holy Saturday ( la, Sabbatum Sanctum), also known as Great and Holy Saturday (also Holy and Great Saturday), the Great Sabbath, Hallelujah Saturday (in Portugal and Brazil), Saturday of the Glory, Sabado de Gloria, and Black Saturday or Easter ...

and being denied entry by the presiding bishop because he had not yet confessed his sins. The bishop goes unnamed. At 6.36.3, he writes of letters from the Christian theologian Origen to Philip and to Philip's wife, Marcia Otacilia Severa. At 6.39, Eusebius writes that Decius persecuted Christians because he hated Philip. The remaining two references are quotations or paraphrases of Dionysius, bishop of Alexandria, a contemporary of Philip (he held the patriarchate

Patriarchate ( grc, πατριαρχεῖον, ''patriarcheîon'') is an ecclesiological term in Christianity, designating the office and jurisdiction of an ecclesiastical patriarch.

According to Christian tradition three patriarchates were esta ...

from 247 to 265).Shahîd, ''Rome and the Arabs'', 71. At 6.41.9, Dionysius contrasts the tolerant Philip's rule with the intolerant Decius'. At 7.10.3, Dionysius implies that Alexander Severus

Marcus Aurelius Severus Alexander (1 October 208 – 21/22 March 235) was a Roman emperor, who reigned from 222 until 235. He was the last emperor from the Severan dynasty. He succeeded his slain cousin Elagabalus in 222. Alexander himself was ...

(emperor from 222 to 235) and Philip were both openly Christian.

Philip's visit to the church

=Text, sources, and interpretation

= Most arguments regarding Philip's Christianity hinge on Eusebius' account of the emperor's visit to a church at 6.34. In the words of the 17th-century ecclesiastical historianLouis-Sébastien Le Nain de Tillemont

Louis-Sébastien Le Nain de Tillemont (30 November 163710 January 1698) was a French ecclesiastical historian.

Life

He was born in Paris into a wealthy Jansenist family, and was educated at the ''Petites écoles'' of Port-Royal, where his histori ...

, it is the "''la ſeule action en laquelle on ſache qu'il ait honoré l'Église''", the "only action in which we know him to have honored the Church".

:Ἔτεσιν δὲ ὅλοις ἓξ Γορδιανοῦ τὴν Ῥωμαίων διανύσαντος ἡγεμονίαν, Φίλιππος ἅμα παιδὶ Φιλίππῳ τὴν ἀρχὴν διαδέχεται. τοῦτον κατέχει λόγος Χριστιανὸν ὄντα ἐν ἡμέρᾳ τῆς ὑστάτης τοῦ πάσχα παννυχίδος τῶν ἐπὶ τῆς ἐκκλησίας εὐχῶν τῷ πλήθει μετασχεῖν ἐθελῆσαι, οὐ πρότερον δὲ ὑπὸ τοῦ τηνικάδε προεστῶτος ἐπιτραπῆναι εἰσβαλεῖν, ἢ ἐξομολογήσασθαι καὶ τοῖς ἐν παραπτώμασιν ἐξεταζομένοις μετανοίας τε χώραν ἴσχουσιν ἑαυτὸν καταλέξαι· ἄλλως γὰρ μὴ ἄν ποτε πρὸς αὐτοῦ, μὴ οὐχὶ τοῦτο ποιήσαντα, διὰ πολλὰς τῶν κατ' αὐτὸν αἰτίας παραδεχθῆναι. καὶ πειθαρχῆσαι γε προθύμως λέγεται, τὸ γνήσιον καὶ εὐλαβὲς τῆς περὶ τὸν θεῖον φόβον διαθέσεως ἔργοις ἐπιδεδειγμένον.

:Gordianus had been Roman emperor for six years when Philip, with his son Philip, succeeded him. It is reported that he, being a Christian, desired, on the day of the last paschal vigil, to share with the multitude in the prayers of the Church, but that he was not permitted to enter, by him who then presided, until he had made confession and had numbered himself among those who were reckoned as transgressors and who occupied the place of penance. For if he had not done this, he would never have been received by him, on account of the many crimes which he had committed. It is said that he obeyed readily, manifesting in his conduct a genuine and pious fear of God.

:Eusebius, ''Historia Ecclesiastica'' 6.34, tr. A. C. McGiffert

In Shahîd's reconstruction, this event took place at Antioch on 13 April 244, while the emperor was on his way back to Rome from the Persian front. The 12th-century Byzantine historian Zonaras

Joannes or John Zonaras ( grc-gre, Ἰωάννης Ζωναρᾶς ; 1070 – 1140) was a Byzantine Greek historian, chronicler and theologian who lived in Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul, Turkey). Under Emperor Alexios I Komnenos he held th ...

repeats the story.

Eusebius introduces his account of Philip's visit with the words κατέχει λόγος' (''katechei logos''). The precise meaning of these words in modern European languages has been contested. Ernst Stein, in an account challenging the veracity of Eusebius' narrative, translated the phrase as "''gerüchte''", or "rumor"; the scholar John Gregg translated it as "the saying goes".Gregg, 43. Other renderings are possible, however; modern English translations of the ''Historia Ecclesiastica'' have "it is recorded" or "it is reported", as in the translation quoted above. The historian Robin Lane Fox

Robin James Lane Fox, (born 5 October 1946) is an English classicist, ancient historian, and gardening writer known for his works on Alexander the Great. Lane Fox is an Emeritus Fellow of New College, Oxford and Reader in Ancient History, Un ...

, who translates ''logos'' as "story" or "rumor" in scare quotes

Scare quotes (also called shudder quotes,Pinker, Steven. ''The Sense of Style: The Thinking Person's Guide to Writing in the 21st Century''. Penguin (2014) sneer quotes, and quibble marks) are quotation marks that writers place around a word o ...

, emphasizes that Eusebius draws a distinction between his "story" about Philip and the other material in the passage.

The substantiative issue involved is the nature of Eusebius' source; where "''gerüchte''" suggests hearsay (Frend explains that Eusebius' κατέχει λόγος' "usually means mere suggestion"), "it is recorded" suggests documentation. Given that Eusebius' major sources for 3rd-century history were written records, Shahîd contends that the typical translation misrepresents the original text. His source here is probably one of the two letters from Origen to Philip and Marcia Otacilia Severa

Marcia Otacilia Severa was the Empress of Rome and wife of Emperor Philip the Arab, who reigned over the Roman Empire from 244 to 249.

Biography Early life

She was a member of the ancient gens Otacilia, of consular and senatorial rank. Her ...

, Philip's wife, mentioned at 6.36.3. Shahîd argues that an oral source is unlikely given that Eusebius composed his ''Historia'' in Caesarea and not Antioch; but others, like Stein and theologian Arthur Cushman McGiffert

Arthur Cushman McGiffert (March 4, 18611933), American theologian, was born in Sauquoit, New York, the son of a Presbyterian clergyman of Scots-Irish descent.

Biography

He graduated at Western Reserve College in 1882 and at Union Theological Se ...

, editor and translator of the ''Historia'' for the '' Select Library of Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers'', contend nonetheless that the story has an oral source.

Shahîd's position is reinforced by C. H. Roberts and A. N. Sherwin-White

Adrian Nicholas Sherwin-White, FBA (10 August 1911 – 1November 1993) was a British academic and ancient historian. He was a fellow of St John's College, University of Oxford and President of the Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies. ...

, who reviewed his ''Rome and the Arabs'' before publication. That is, that the proper interpretation of κατέχει λόγος is as a reference to a written account. Roberts notes that Χριστιανὸν ὄντα (''Christianon onta'', "being a Christian") was probably an editorial insertion by Eusebius, and not included in the ''logos'' he relates in the passage. Shahîd takes this as an indication that Eusebius did indeed vouch for Philip's Christianity. Roberts suggested that κατέχει λόγος might be translated as "there is a wide-spread report", but added that a broader study of Eusebius' use of the expression elsewhere would be useful. Sherwin-White points out Eusebius' use of the phrase in his passage on the Thundering Legion

Legio XII Fulminata ("Thunderbolt Twelfth Legion"), also known as ''Paterna'', ''Victrix'', ''Antiqua'', ''Certa Constans'', and ''Galliena'', was a legion of the Imperial Roman army. It was originally levied by Julius Caesar in 58 BC, and the leg ...

(at ''Historia Ecclesiastica'' 5.5), where it represents a reference to written sources.

However, because Eusebius nowhere categorically asserts that he has read the letters (he only says that he has compiled themShahîd, ''Rome and the Arabs'', 73.) and as moderns are disinclined to take him at his word, some, like Pohlsander, posit that Eusebius did not get the tale from the letters, and drew it instead from oral rumors. Whatever the case, the wording of the passage shows that Eusebius is unenthusiastic about his subject and skeptical of its significance. Jerome and the Latin Christian authors following him do not share his caution.

=Contexts and parallels

= For many scholars, the scene at 6.34 seems to anticipate and parallel the confrontation betweenTheodosius Theodosius ( Latinized from the Greek "Θεοδόσιος", Theodosios, "given by god") is a given name. It may take the form Teodósio, Teodosie, Teodosije etc. Theodosia is a feminine version of the name.

Emperors of ancient Rome and Byzantium

...

and Ambrose

Ambrose of Milan ( la, Aurelius Ambrosius; ), venerated as Saint Ambrose, ; lmo, Sant Ambroeus . was a theologian and statesman who served as Bishop of Milan from 374 to 397. He expressed himself prominently as a public figure, fiercely promo ...

in 390; Erasmus

Desiderius Erasmus Roterodamus (; ; English: Erasmus of Rotterdam or Erasmus;''Erasmus'' was his baptismal name, given after St. Erasmus of Formiae. ''Desiderius'' was an adopted additional name, which he used from 1496. The ''Roterodamus'' wa ...

used the two situations as parallel ''exempla

An exemplum (Latin for "example", pl. exempla, ''exempli gratia'' = "for example", abbr.: ''e.g.'') is a moral anecdote, brief or extended, real or fictitious, used to illustrate a point. The word is also used to express an action performed by an ...

'' in a letter written to Francis I Francis I or Francis the First may refer to:

* Francesco I Gonzaga (1366–1407)

* Francis I, Duke of Brittany (1414–1450), reigned 1442–1450

* Francis I of France (1494–1547), King of France, reigned 1515–1547

* Francis I, Duke of Saxe-Lau ...

in 1523. That later event has been taken as evidence against Philip's Christianity. Even in the later 4th century, in a society that had already been significantly Christianized

Christianization ( or Christianisation) is to make Christian; to imbue with Christian principles; to become Christian. It can apply to the conversion of an individual, a practice, a place or a whole society. It began in the Roman Empire, conti ...

, the argument goes, Theodosius' humiliation had shocked the sensibilities of the aristocratic elite. It is therefore inconceivable that 3rd century aristocrats, members of a society that had experienced only partial Christianization, would accept such self-abasement from their emperors. Shahîd contests this parallel, and argues that Philip's scene was far less humiliating than Theodosius': it did not take place against the same background (Theodosius had massacred seven thousand Thessalonicans some months before), no one was excommunicated (Theodosius was excommunicated for eight months), and it did not involve the same dramatic and humiliating dialogue between emperor and bishop. Philip made a quick repentance at a small church on his way back to Rome from the Persian front, a stark contrast to the grandeur of Theodosius' confrontation with Ambrose.

Other scholars, such as ecclesiastical historian H. M. Gwatkin, explain Philip's alleged visit to the church as evidence of simple "curiosity". That he was excluded from services is not surprising: as a "heathen" in official conduct, and, as an unbaptized man, it would have been unusual if he had been admitted. Shahîd rejects idle curiosity as an explanation, arguing that 3rd-century churches were too nondescript to attract much undue attention. That Philip was unbaptized is nowhere proven or stated, and, even if true, it would do little to explain the scene: Constantine participated in Christian services despite postponing baptism to the end of his life—and participation in services without baptism was not unusual for Christians of either period.

Dionysius, bishop of Alexandria

:The mention of those princes who were publicly supposed to be Christians, as we find it in an epistle of Dionysius of Alexandria (ap. Euseb. l. vii c. 10.), evidently alludes to Philip and his family; and forms a contemporary evidence, that such a report had prevailed; but the Egyptian bishop, who lived at an humble distance from the court of Rome, expresses himself with becoming diffidence concerning the truth of the fact.

At 6.41, Eusebius quotes a letter from Dionysius, bishop of Alexandria, to Fabius, bishop of Antioch, on the persecution at Alexandria under Decius. He begins (at 6.41.1) by describing the pogroms which began a year before Decius' decree of 250; that is, in 249, under Philip. At 6.41.9, Dionysius narrates the transition from Philip to Decius.

Edward Gibbon, ''The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire'', ed. D. Womersley (London: Penguin, 1994 776 __NOTOC__ Year 776 ( DCCLXXVI) was a leap year starting on Monday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar. The denomination 776 for this year has been used since the early medieval period, when the Anno Domini calendar era ..., 1.554 n. 119.

:καὶ ταῦτα ἐπὶ πολὺ μὲν τοῦτον ἤκμασεν τὸν τρόπον, διαδεξαμένη δὲ τοὺς ἀθλίους ἡ στάσις καὶ πόλεμος ἐμφύλιος τὴν καθ' ἡμῶν ὠμότητα πρὸς ἀλλήλους αὐτῶν ἔτρεψεν, καὶ σμικρὸν μὲν προσανεπνεύσαμεν, ἀσχολίαν τοῦ πρὸς ἡμᾶς θυμοῦ λαβόντων, εὐθέως δὲ ἡ τῆς βασιλείας ἐκείνης τῆς εὐμενεστέρας ἡμῖν μεταβολὴ διήγγελται, καὶ πολὺς ὁ τῆς ἐφ' ἡμᾶς ἀπειλῆς φόβος ἀνετείνετο.

:And matters continued thus for a considerable time. But a sedition and civil war came upon the wretched people and turned their cruelty toward us against one another. So we breathed for a little while as they ceased from their rage against us. But presently the change from that milder reign was announced to us, and great fear of what was threatened seized us.

:Eusebius, ''Historia Ecclesiastica'' 6.41.9, tr. A. C. McGiffert

At 7.10.3, Eusebius quotes a letter from Dionysius to the otherwise-unknown Hermammon on the early years of Valerian's (r. 253–260) rule. In this period the emperor implicitly tolerated Christianity; Eusebius would contrast his early reputation with his later policy of persecution.

:ἀμφότερα δὲ ἔστιν ἐπὶ Οὐαλεριανοῦ θαυμάσαι καὶ τούτων μάλιστα τὰ πρὸ αὐτοῦ ὡς οὕτως ἔσχεν, συννοεῖν ὡς μὲν ἤπιος καὶ φιλόφρων ἦν πρὸς τοὺς ἀνθρώπους τοῦ θεοῦ· οὐδὲ γὰρ ἄλλος τις οὕτω τῶν πρὸ αὐτοῦ βασιλέων εὐμενῶς καὶ δεξιῶς πρὸς αὐτοὺς διετέθη, οὐδ' οἱ λεχθέντες ἀναφανδὸν Χριστιανοὶ γεγονέναι, ὡς ἐκεῖνος οἰκειότατα ἐν ἀρχῇ καὶ προσφιλέστατα φανερὸς ἦν αὐτοὺς ἀποδεχόμενος, καὶ πᾶς τε ὁ οἶκος αὐτοῦ θεοσεβῶν πεπλήρωτο καὶ ἦν ἐκκλησία θεοῦ·

:It is wonderful that both of these things occurred under Valerian; and it is the more remarkable in this case when we consider his previous conduct, for he had been mild and friendly toward the men of God, for none of the emperors before him had treated them so kindly and favorably; and not even those who were said openly to be Christians received them with such manifest hospitality and friendliness as he did at the beginning of his reign. For his entire house was filled with pious persons and was a church of God.

:Eusebius, ''Historia Ecclesiastica'' 7.10.3, tr. A. C. McGiffert

Dionysius is quoted saying that Valerian was so friendly to Christians that he outdid "those who were said to be openly Christians" (οἰ λεχθέντες ἀναφανδὸν Χριοτιανοὶ γεγονέναι, tr. Shahîd). Most scholars, Shahîd and Stein included, understand this as a reference to Severus Alexander and Philip. Because the reference is to a plurality of emperors, implying that Severus Alexander and Philip were both Christians, Stein dismissed the passage as entirely without evidentiary value. Shahîd, however, contends that genuine information can be extracted from the spurious whole, and that, while the reference to Severus Alexander is hyperbole, the reference to Philip is not. He explains the reference to Severus Alexander as a Christian as an exaggeration of what was actually only an interest in the Christian religion. Shahîd references a passage in the often-dubious ''Historia Augusta

The ''Historia Augusta'' (English: ''Augustan History'') is a late Roman collection of biographies, written in Latin, of the Roman emperors, their junior colleagues, designated heirs and usurpers from 117 to 284. Supposedly modeled on the sim ...

''s biography of the emperor, which states that Alexander had statues of Abraham

Abraham, ; ar, , , name=, group= (originally Abram) is the common Hebrew patriarch of the Abrahamic religions, including Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. In Judaism, he is the founding father of the special relationship between the Jew ...

, Christ, and Orpheus

Orpheus (; Ancient Greek: Ὀρφεύς, classical pronunciation: ; french: Orphée) is a Thracian bard, legendary musician and prophet in ancient Greek religion. He was also a renowned poet and, according to the legend, travelled with Jaso ...

in his private chapel, and that he prayed to them each morning. He also adduces the letters sent from Origen to Alexander's mother Mamaea (Eusebius, ''Historia Ecclesiastica'' 6.21, 6.28) to explain Dionysius' comment.

Origen's letters

:φέρεται δὲ αὐτοῦ καὶ πρὸς αὐτὸν βασιλέα Φίλιππον ἐπιστολὴ καὶ ἄλλη πρὸς τὴν τούτου γαμετὴν Σευήραν διάφοροί τε ἄλλαι πρὸς διαφόρους· ὧν ὁπόσας σποράδην παρὰ διαφόροις σωθείσας συναγαγεῖν δεδυνήμεθα, ἐν ἰδίαις τόμων περιγραφαῖς, ὡς ἂν μηκέτι διαρρίπτοιντο, κατελέξαμεν, τὸν ἑκατὸν ἀριθμὸν ὑπερβαινούσας.

:There is extant also an epistle of his to the Emperor Philip, and another to Severa his wife, with several others to different persons. We have arranged in distinct books to the number of one hundred, so that they might be no longer scattered, as many of these as we have been able to collect, which have been preserved here and there by different persons.

:Eusebius, ''Historia Ecclesiastica'', 6.36.3, tr. A. C. McGiffert

Origen's letters do not survive. However, most scholars believe that the letters that circulated in the era of Eusebius and Jerome were genuine. It is also reasonable that Origen, a man with close contacts in the Christian Arab community, would have taken a particular interest in the first Arab emperor. The scholar K. J. Neumann argued that, since Origen would have known the faith of the imperial couple, he must have written about it in the letters listed at 6.36.3. Since Eusebius read these letters, and does not mention that the emperor was Christian (Neumann understands the passage at 6.34 to reflect Eusebius' disbelief in Philip's Christianity), we must conclude that Philip was not Christian, and was neither baptized nor made catechumen. Against Neumann, Shahîd argues that, if Eusebius had found anything in the letters to disprove Philip's Christianity, he would have clearly outlined it in this passage—as the biographer of Constantine, it would have been in his interest to undermine any other claimants to the title "first Christian emperor". Moreover, this segment of the ''Historia'' is a catalog of Origen's works and correspondence; the contents of the letters are irrelevant.

Views on the Arabs

Eusebius' understanding of the Arab peoples is informed by his reading of theBible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts of a ...

and his knowledge of the history of imperial Rome. He does not appear to have personally known any Arabs. In his ''Chronicon'', all the Arabs that appear—save for one reference to Ishmael

Ishmael ''Ismaḗl''; Classical/Qur'anic Arabic: إِسْمَٰعِيْل; Modern Standard Arabic: إِسْمَاعِيْل ''ʾIsmāʿīl''; la, Ismael was the first son of Abraham, the common patriarch of the Abrahamic religions; and is cons ...

—figure in the political history of the first three centuries of the Christian era. To Eusebius, the Saracen

upright 1.5, Late 15th-century German woodcut depicting Saracens

Saracen ( ) was a term used in the early centuries, both in Greek and Latin writings, to refer to the people who lived in and near what was designated by the Romans as Arabia Pe ...

s of the 4th century are direct-line descendants of the biblical Ishmaelites

The Ishmaelites ( he, ''Yīšməʿēʾlīm,'' ar, بَنِي إِسْمَاعِيل ''Bani Isma'il''; "sons of Ishmael") were a collection of various Arabian tribes, confederations and small kingdoms described in Islamic tradition as being desc ...

, descendants of the handmaid, Hagar

Hagar, of uncertain origin; ar, هَاجَر, Hājar; grc, Ἁγάρ, Hagár; la, Agar is a biblical woman. According to the Book of Genesis, she was an Egyptian slave, a handmaiden of Sarah (then known as ''Sarai''), whom Sarah gave to he ...

, and the patriarch, Abraham

Abraham, ; ar, , , name=, group= (originally Abram) is the common Hebrew patriarch of the Abrahamic religions, including Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. In Judaism, he is the founding father of the special relationship between the Jew ...

. They are thus outcasts, beyond God's Covenant

Covenant may refer to:

Religion

* Covenant (religion), a formal alliance or agreement made by God with a religious community or with humanity in general

** Covenant (biblical), in the Hebrew Bible

** Covenant in Mormonism, a sacred agreement b ...

with the favored son of Abraham, Isaac

Isaac; grc, Ἰσαάκ, Isaák; ar, إسحٰق/إسحاق, Isḥāq; am, ይስሐቅ is one of the three patriarchs of the Israelites and an important figure in the Abrahamic religions, including Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. He was the ...

. The twin images of the Ishmaelite and the Saracen—outcasts and ''latrones'', raiders of the frontiers—reinforce each other and give Eusebius' portrait of the Arab nation an unhappy color. He may have been reluctant to associate the first Christian emperor with a people of such unfortunate ancestry.

In his ''Historia'', Eusebius does not identify either Philip or Abgar V of Edessa

Abgar V (c. 1st century BC - c. AD 50), called Ukkāmā (meaning "the Black" in Syriac and other dialects of Aramaic),, syr, ܐܒܓܪ ܚܡܝܫܝܐ ܐܘܟܡܐ, ʾAḇgar Ḥmīšāyā ʾUkkāmā, hy, Աբգար Ե Եդեսացի, Abgar Hingeror ...

(whom he incorrectly presumed to be the first Christian prince; he does not mention Abgar VIII

__NOTOC__

Abgar VIII of Edessa, also known as Abgar the Great or Abgar bar Ma'nu, was an Arab king of Osroene from 177-212 CE.

Abgar the Great was most remembered for his alleged conversion to Christianity in about 200 CE and the declaration of ...

, who was actually the first Christian prince), as Arabs. He does, however, identify Herod the Great

Herod I (; ; grc-gre, ; c. 72 – 4 or 1 BCE), also known as Herod the Great, was a Roman Jewish client king of Judea, referred to as the Herodian kingdom. He is known for his colossal building projects throughout Judea, including his renov ...

as an Arab, thus tarring the Arab nation with the Massacre of the Innocents and the attempted murder of Christ himself. The Christianity of Provincia Arabia in the 3rd century also earns some brief notices: the heresy of Beryllos, bishop of Bostra, and his correction by Origen (6.33); the heretical opinions concerning the soul held by a group of Arabs until corrected by Origen (6.37); and the heresy of Helkesaites (6.38). Eusebius' account of Philip appears amidst these Arab heresies (at 6.34, 6.36, and 6.39), although, again—and in spite of the fact that Philip so often took on the epithet "the Arab", in antiquity as today—he never identifies him as an Arab. The image of the Arabs as heretics would persist in later ecclesiastical historians (like Epiphanius of Salamis

Epiphanius of Salamis ( grc-gre, Ἐπιφάνιος; c. 310–320 – 403) was the bishop of Salamis, Cyprus, at the end of the 4th century. He is considered a saint and a Church Father by both the Eastern Orthodox and Catholic Churches. He gai ...

). Shahîd, relating these facts, nonetheless concludes that "Eusebius cannot be accused in the account he gave of the Arabs and their place in the history of Christianity." The fact that he downplayed the role of Philip and Abgar in the establishment of Christianity as a state religion is understandable, given his desire to prop up Constantine

Constantine most often refers to:

* Constantine the Great, Roman emperor from 306 to 337, also known as Constantine I

* Constantine, Algeria, a city in Algeria

Constantine may also refer to:

People

* Constantine (name), a masculine given na ...

's reputation.Shahîd, ''Rome and the Arabs'', 109.

Views on Constantine

In Shahîd's judgment, the imprecision and unemphatic tone of Eusebius' passage at 6.34 is the major cause of the lack of scholarly consensus on Philip's Christianity. To Shahîd, Eusebius' wording choice is a reflection of his own lack of enthusiasm for Philip's Christianity, which is in turn a reflection of the special position Constantine held in his regards and in his written work. A number of scholars, following E. Schwartz, believe the later editions of Eusebius' ''Historia'' to have been extensively revised to adapt to the deterioration ofLicinius

Valerius Licinianus Licinius (c. 265 – 325) was Roman emperor from 308 to 324. For most of his reign he was the colleague and rival of Constantine I, with whom he co-authored the Edict of Milan, AD 313, that granted official toleration to C ...

in the public memory (and official ''damnatio memoriae

is a modern Latin phrase meaning "condemnation of memory", indicating that a person is to be excluded from official accounts. Depending on the extent, it can be a case of historical negationism. There are and have been many routes to , includi ...

'') after Constantine deposed and executed him in 324–25. Passages of the ''Historia'' incompatible with Licinius' denigration were suppressed, and an account of the last years of his life was replaced with a summary of the Council of Nicaea. Shahîd suggests that, in addition to these anti-Licinian deletions, Eusebius also edited out favorable notices on Philip to better glorify Constantine's achievement.

In 335, Eusebius wrote and delivered his ''Laudes Constantini'', a panegyric

A panegyric ( or ) is a formal public speech or written verse, delivered in high praise of a person or thing. The original panegyrics were speeches delivered at public events in ancient Athens.

Etymology

The word originated as a compound of grc, ...

on the thirtieth anniversary of the emperor's reign; his ''Vita Constantini'', written over the next two years, has the same laudatory tone. The ecclesiastical historian, who framed his chronology on the reigns of emperors and related the entries in his history to each emperor's reign, understood Constantine's accession as something miraculous, especially as it came immediately after the Great Persecution

The Diocletianic or Great Persecution was the last and most severe persecution of Christians in the Roman Empire. In 303, the emperors Diocletian, Maximian, Galerius, and Constantius issued a series of edicts rescinding Christians' legal right ...

. The final edition of his ''Historia'' has its climax in Constantine's reign, the ultimate "triumph of Christianity". Shahîd argues, it was therefore in his authorial interest to obscure the details of Philip, the first Christian emperor; hence, because of Eusebius' skill in narrative and deception, modern historians give Constantine that title.

Shahîd further argues that the facts of Philip's alleged Christianity would also discourage Eusebius from celebrating that emperor. Firstly, Philip lacks an exciting conversion narrative Broadly speaking, a conversion narrative is a narrative that relates the operation of conversion, usually religious. As a specific aspect of American literary and religious history, the conversion narrative was an important facet of Puritan sacred a ...

; secondly, his religion was private, unlike Constantine's very public patronage of the faith; and, thirdly, his reign only lasted five years, not long enough to enact much amelioration of the Christians' condition. In Shahîd's view, the insignificance of his reign to the progress of Christianity, Eusebius' subject, combined with Eusebius' role as Constantine's panegyrist, explain the tone and content of his account.

''Vita Constantini''

F. H. Daniel, in Philip's entry in the Smith–Wace ''Dictionary of Christian Biography'', cites a passage of Eusebius' ''Vita Constantini'' as his first piece of evidence against Philip's alleged Christianity. In the passage, Eusebius names Constantine as (in the words of the dictionary) "the first Christian emperor".F.H. Blackburne Daniel, "Philippus" (5), in ''A Dictionary of Christian Biography'', ed. William Smith and Henry Wace (London: John Murray, 1887), 355.

:ἀθανάτους πιστούμενος ἐλπίδας. παλαιοὶ ταῦτα χρησμοὶ προφητῶν γραφῇ παραδοθέντες θεσπίζουσι, ταῦτα βίοι θεοφιλῶν ἀνδρῶν παντοίαις ἀρεταῖς πρόπαλαι διαλαμψάντων τοῖς ὀψιγόνοις μνημονευόμενοι μαρτύρονται, ταῦτα καὶ ὁ καθ' ἡμᾶς ἀληθῆ εἶναι διήλεγξε χρόνος, καθ' ὃν Κωνσταντῖνος θεῷ τῷ παμβασιλεῖ μόνος τῶν πώποτε τῆς Ῥωμαίων ἀρχῆς καθηγησαμένων γεγονὼς φίλος, ἐναργὲς ἅπασιν ἀνθρώποις παράδειγμα θεοσεβοῦς κατέστη βίου.

:The ancient oracles of the prophets, delivered to us in the Scripture, declare this; the lives of pious men, who shone in old time with every virtue, bear witness to posterity of the same; and our own days prove it to be true, wherein Constantine, who alone of all that ever wielded the Roman power was the friend of God the Sovereign of all, has appeared to all mankind so clear an example of a godly life.

:Eusebius, ''Vita Constantini'' 1.3.4, tr. E.C. Richardson

Shahîd describes this passage as a mere flourish from Eusebius the panegyrist, "carried away by enthusiasm and whose statements must be construed as rhetorical exaggeration"; he does not take it as serious evidence against Eusebius' earlier accounts in the ''Historia'', where he never refers to Constantine as the first Christian emperor. For Shahîd, the passage also represents the last stage in Eusebius' evolving portrait of the pair of emperors, Philip and Constantine: in the early 300s, in his ''Chronicon'', he had nearly called Philip the first Christian emperor; in the 320s, during the revision of the ''Historia'' and the ''Chronicon'', he turned wary and skeptical; in the late 330s, he could confidently assert that Constantine was the sole Christian emperor.Shahîd, ''Rome and the Arabs'', 82. John York argues that, in writing this passage, Eusebius was cowed by the anti-Licinian propaganda of the Constantinian era: as an ancestor of the emperor's last enemy, Philip could not receive the special distinction of the title "first Christian emperor"—Constantine had claimed it for himself. Perhaps, Shahîd observes, it is not coincidental that Eusebius would paint the Arabs in uncomplimentary terms (as idolaters and practitioners of human sacrifice) in his ''Laudes Constantini'' of 335.

Chrysostom and Leontius

John Chrysostom, deacon at Antioch from 381, was made priest in 386. As a special distinction, his bishop, Flavian, decided that he should preach in the city's principal church. Chrysostom's contribution to the literature on Philip and Christianity is a homily on Babylas, a martyr-bishop who died in 253, during theDecian persecution

The Decian persecution of Christians occurred in 250 AD under the Roman Emperor Decius. He had issued an edict ordering everyone in the Empire to perform a sacrifice to the Roman gods and the well-being of the emperor. The sacrifices had to ...

. The treatise was composed about 382, when John was a deacon, and forms part of Chrysostom's corpus of panegyrics. Chrysostom's Babylas confronts an emperor; and, since Chrysostom is more interested in the bishop than his opponent, the emperor goes unnamed. He has since been identified with Philip.