Peter Scott on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir Peter Markham Scott, (14 September 1909 – 29 August 1989) was a British ornithologist, conservationist, painter,

Scott was born in London at 174, Buckingham Palace Road, the only child of Antarctic explorer Robert Falcon Scott and sculptor Kathleen Bruce. He was only two years old when his father died. Robert Scott, in a last letter to his wife, advised her to "make the boy interested in natural history if you can; it is better than games." He was named after Sir Clements Markham, mentor of Scott's polar expeditions, and a godfather along with J. M. Barrie, creator of Peter Pan.

His mother Lady Scott remarried in 1922. Her second husband Hilton Young (later Lord Kennet) became stepfather to Peter. In 1923, a half-brother,

Scott was born in London at 174, Buckingham Palace Road, the only child of Antarctic explorer Robert Falcon Scott and sculptor Kathleen Bruce. He was only two years old when his father died. Robert Scott, in a last letter to his wife, advised her to "make the boy interested in natural history if you can; it is better than games." He was named after Sir Clements Markham, mentor of Scott's polar expeditions, and a godfather along with J. M. Barrie, creator of Peter Pan.

His mother Lady Scott remarried in 1922. Her second husband Hilton Young (later Lord Kennet) became stepfather to Peter. In 1923, a half-brother,

During the

During the  Then he served in destroyers in the North Atlantic but later moved to commanding the First (and only) Squadron of Steam Gun Boats against German E-boats in the

Then he served in destroyers in the North Atlantic but later moved to commanding the First (and only) Squadron of Steam Gun Boats against German E-boats in the

Scott stood as a Conservative in the

Scott stood as a Conservative in the  As a member of the Species Survival Commission of the International Union for Conservation of Nature, he helped create the Red Data books, the group's lists of endangered species.

Scott was the founder President of the Society of Wildlife Artists and President of the Nature in Art Trust (a role in which his wife Philippa succeeded him). Scott tutored numerous artists including

As a member of the Species Survival Commission of the International Union for Conservation of Nature, he helped create the Red Data books, the group's lists of endangered species.

Scott was the founder President of the Society of Wildlife Artists and President of the Nature in Art Trust (a role in which his wife Philippa succeeded him). Scott tutored numerous artists including

Article illustrated with his paintings

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Scott, Peter 1909 births 1989 deaths English ornithologists British conservationists English activists Cryptozoologists English television presenters Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust English illustrators 20th-century English painters English male painters 20th-century English writers Fellows of the Royal Society (Statute 12) British stamp designers English male sailors (sport) Sailors at the 1936 Summer Olympics – O-Jolle Olympic sailors of Great Britain Olympic bronze medallists for Great Britain 1964 America's Cup sailors Members of the Order of the Companions of Honour Knights Bachelor Anglo-Scots Gliding in England Glider pilots Chancellors of the University of Birmingham Rectors of the University of Aberdeen Alumni of Trinity College, Cambridge People educated at West Downs School People educated at Oundle School English people of Scottish descent English conservationists British bird artists Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve personnel of World War II Olympic medalists in sailing Camoufleurs 20th-century British zoologists Recipients of the Distinguished Service Cross (United Kingdom) Commanders of the Order of the British Empire Medalists at the 1936 Summer Olympics Peter Presidents of World Sailing English sports executives and administrators Military personnel from London 20th-century English male artists

naval officer

An officer is a person who holds a position of authority as a member of an armed force or uniformed service.

Broadly speaking, "officer" means a commissioned officer, a non-commissioned officer, or a warrant officer. However, absent cont ...

, broadcaster and sportsman. The only child of Antarctic explorer Robert Falcon Scott, he took an interest in observing and shooting wildfowl at a young age and later took to their breeding.

He established the Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust in Slimbridge

Slimbridge is a village and civil parish near Dursley in Gloucestershire, England.

It is best known as the home of the Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust's Slimbridge Reserve which was started by Sir Peter Scott.

Canal and Patch Bridge

The Gloucest ...

in 1946 and helped found the World Wide Fund for Nature, the logo of which he designed. He was a yachting enthusiast from an early age and took up gliding in mid-life. He was part of the UK team for the 1936 Summer Olympics

The 1936 Summer Olympics ( German: ''Olympische Sommerspiele 1936''), officially known as the Games of the XI Olympiad ( German: ''Spiele der XI. Olympiade'') and commonly known as Berlin 1936 or the Nazi Olympics, were an international multi- ...

and won a bronze medal in sailing. He was knighted in 1973 for his work in conservation of wild animals and was also a recipient of the WWF Gold Medal and the J. Paul Getty Prize.

Early life

Scott was born in London at 174, Buckingham Palace Road, the only child of Antarctic explorer Robert Falcon Scott and sculptor Kathleen Bruce. He was only two years old when his father died. Robert Scott, in a last letter to his wife, advised her to "make the boy interested in natural history if you can; it is better than games." He was named after Sir Clements Markham, mentor of Scott's polar expeditions, and a godfather along with J. M. Barrie, creator of Peter Pan.

His mother Lady Scott remarried in 1922. Her second husband Hilton Young (later Lord Kennet) became stepfather to Peter. In 1923, a half-brother,

Scott was born in London at 174, Buckingham Palace Road, the only child of Antarctic explorer Robert Falcon Scott and sculptor Kathleen Bruce. He was only two years old when his father died. Robert Scott, in a last letter to his wife, advised her to "make the boy interested in natural history if you can; it is better than games." He was named after Sir Clements Markham, mentor of Scott's polar expeditions, and a godfather along with J. M. Barrie, creator of Peter Pan.

His mother Lady Scott remarried in 1922. Her second husband Hilton Young (later Lord Kennet) became stepfather to Peter. In 1923, a half-brother, Wayland Young

Wayland Hilton Young, 2nd Baron Kennet (2 August 1923 – 7 May 2009) was a British writer and politician, notably concerned with planning and conservation. As a Labour minister, he was responsible for setting up the Department of the Environmen ...

, was born.

Scott was educated at Oundle School

Oundle School is a public school (English independent day and boarding school) for pupils 11–18 situated in the market town of Oundle in Northamptonshire, England. The school has been governed by the Worshipful Company of Grocers of the ...

and Trinity College, Cambridge

Trinity College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. Founded in 1546 by King Henry VIII, Trinity is one of the largest Cambridge colleges, with the largest financial endowment of any college at either Cambridge or Oxford. ...

, initially reading Natural Sciences

Natural science is one of the branches of science concerned with the description, understanding and prediction of natural phenomena, based on empirical evidence from observation and experimentation. Mechanisms such as peer review and repeat ...

but graduating in the History of Art in 1931. Whilst at Cambridge he shared digs with John Berry and the two shared many views. As a student he was also an active member of the Cambridge University Cruising Club, sailing against Oxford in the 1929 and 1930 Varsity Matches. He studied art at the State Academy in Munich for a year followed by studies at the Royal Academy Schools, London. One of the few non-wildlife paintings that he produced during his career, 'Dinghies Racing on Lake Ontario', is held by the Cambridge University Cruising Club.

Like his mother, he displayed a strong artistic talent and he became known as a painter of wildlife, particularly birds; he had his first exhibition in London in 1933. His wealthy background allowed him to follow his interests in art, wildlife and many sports, including wildfowling, sailing

Sailing employs the wind—acting on sails, wingsails or kites—to propel a craft on the surface of the ''water'' ( sailing ship, sailboat, raft, windsurfer, or kitesurfer), on ''ice'' ( iceboat) or on ''land'' ( land yacht) over a chose ...

, gliding and ice skating

Ice skating is the self-propulsion and gliding of a person across an ice surface, using metal-bladed ice skates. People skate for various reasons, including recreation (fun), exercise, competitive sports, and commuting. Ice skating may be per ...

. He represented Great Britain and Northern Ireland at sailing at the 1936 Summer Olympics, winning a bronze medal in the O-Jolle monotype class. He also participated in the Prince of Wales Cup in 1938 during which he and his crew on the ''Thunder and Lightning'' dinghy designed a modified wearable harness (now known as a trapeze) that helped them win.

Second World War

During the

During the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, Scott served in the Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve. As a Sub-Lieutenant, during the failed evacuation of the 51st Highland Division

The 51st (Highland) Division was an infantry division of the British Army that fought on the Western Front in France during the First World War from 1915 to 1918. The division was raised in 1908, upon the creation of the Territorial Force, as ...

he was the British Naval officer sent ashore at Saint-Valery-en-Caux in the early hours of 11 June 1940 to evacuate some of the wounded. This was the last evacuation of British troops from the port area of St Valery that was not disrupted by enemy fire.

Then he served in destroyers in the North Atlantic but later moved to commanding the First (and only) Squadron of Steam Gun Boats against German E-boats in the

Then he served in destroyers in the North Atlantic but later moved to commanding the First (and only) Squadron of Steam Gun Boats against German E-boats in the English Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" ( Cotentinais) or (Jèrriais), ( Guernésiais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, Môr Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Kan ...

.

Scott is credited with designing the Western Approaches ship camouflage scheme, which disguised the look of ship superstructure. In July 1940, he managed to get the destroyer ''HMS Broke (D83)

HMS ''Broke'' was a Thornycroft type flotilla leader of the Royal Navy. She was the second of four ships of this class that were ordered from J I Thornycroft in April 1918, and was originally named ''Rooke'' after Rear Admiral Sir George ...

'' in which he was serving experimentally camouflaged, differently on the two sides. To starboard, the ship was painted blue-grey all over, but with white in naturally shadowed areas as countershading, following the ideas of Abbott Handerson Thayer

Abbott Handerson Thayer (August 12, 1849May 29, 1921) was an American artist, naturalist and teacher. As a painter of portraits, figures, animals and landscapes, he enjoyed a certain prominence during his lifetime, and his paintings are represe ...

from the First World War. To port, the ship was painted in "bright pale colours" to combine some disruption of shape with the ability to fade out during the night, again with shadowed areas painted white. However, he later wrote that compromise was fatal to camouflage, and that invisibility at night (by painting ships in white or other pale colours) had to be the sole objective.

By May 1941, all ships in the Western Approaches (the North Atlantic) were ordered to be painted in Scott's camouflage scheme. The scheme was said to be so effective that several British ships including ''HMS Broke'' collided with each other. The effectiveness of Scott's and Thayer's ideas was demonstrated experimentally by the Leamington Camouflage Centre in 1941. Under a cloudy overcast sky, the tests showed that a white ship could approach six miles (9.6 km) closer than a black-painted ship before being seen.

Postwar life

Scott stood as a Conservative in the

Scott stood as a Conservative in the 1945 general election

The following elections occurred in the year 1945.

Africa

* 1945 South-West African legislative election

Asia

* 1945 Indian general election

Australia

* 1945 Fremantle by-election

Europe

* 1945 Albanian parliamentary election

* 1945 Bulgaria ...

in Wembley North and narrowly failed to be elected. In 1946, he founded the organisation with which he was ever afterwards closely associated, the Severn Wildfowl Trust (now the Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust) with its headquarters at Slimbridge

Slimbridge is a village and civil parish near Dursley in Gloucestershire, England.

It is best known as the home of the Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust's Slimbridge Reserve which was started by Sir Peter Scott.

Canal and Patch Bridge

The Gloucest ...

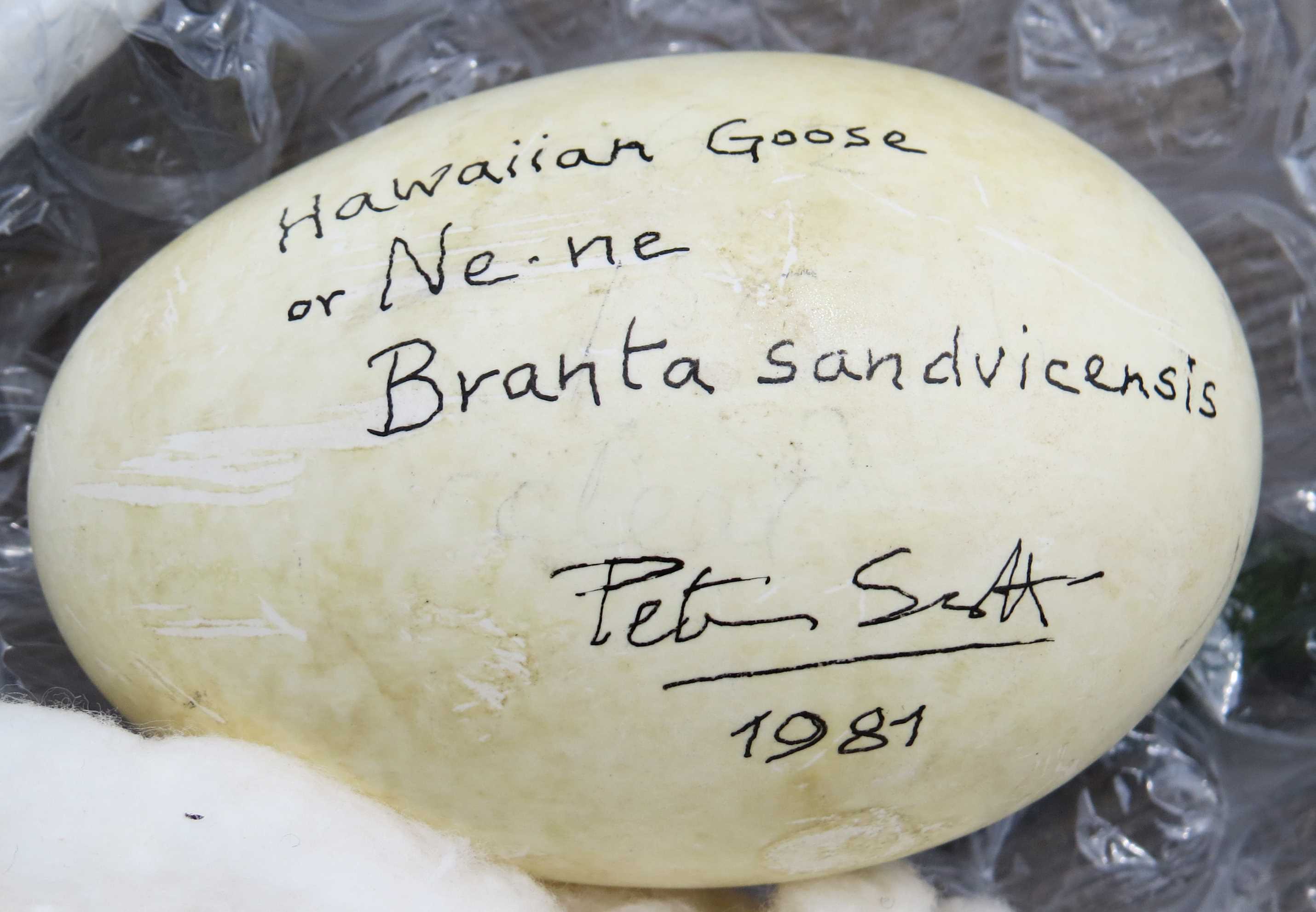

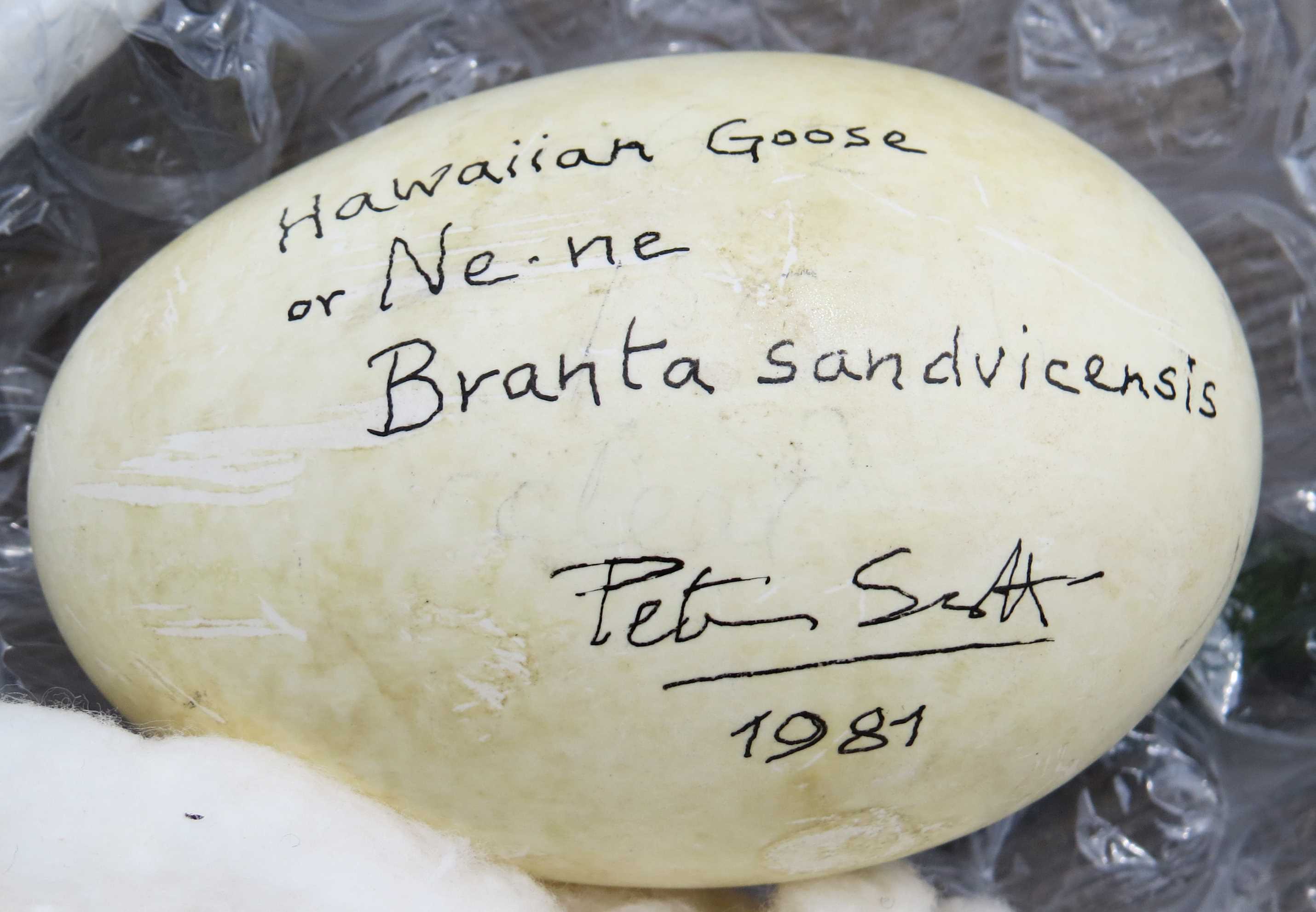

in Gloucestershire. There, through a captive breeding programme, he saved the nene or Hawaiian goose from extinction in the 1950s. In the years that followed, he led ornithological expeditions worldwide, and became a television personality, popularising the study of wildfowl and wetlands.

His BBC natural history series, ''Look'', ran from 1955 to 1969 and made him a household name. It included the first BBC natural history film to be shown in colour, ''The Private Life of the Kingfisher

"The Private Life of the Kingfisher" is a 1966 television episode of the nature series ''Look

To look is to use sight to perceive an object.

Look or The Look may refer to:

Businesses and products

* Look (modeling agency), an Israeli modeli ...

'' (1968), which he narrated. He wrote and illustrated several books on the subject, including his autobiography, ''The Eye of the Wind'' (1961). In the 1950s, he also appeared regularly on BBC radio

BBC Radio is an operational business division and service of the British Broadcasting Corporation (which has operated in the United Kingdom under the terms of a royal charter since 1927). The service provides national radio stations covering ...

's '' Children's Hour'', in the series, "Nature Parliament".

Scott took up gliding in 1956 and became a British champion in 1963. He was chairman of the British Gliding Association (BGA) for two years from 1968 and was president of the Bristol & Gloucestershire Gliding Club. He was responsible for involving Prince Philip in gliding.

He was the subject of ''This Is Your Life This Is Your Life may refer to:

Television

* ''This Is Your Life'' (American franchise), an American radio and television documentary biography series hosted by Ralph Edwards

* ''This Is Your Life'' (Australian TV series), the Australian versio ...

'' in 1956 when he was surprised by Eamonn Andrews at the King's Theatre, Hammersmith, London.

As a member of the Species Survival Commission of the International Union for Conservation of Nature, he helped create the Red Data books, the group's lists of endangered species.

Scott was the founder President of the Society of Wildlife Artists and President of the Nature in Art Trust (a role in which his wife Philippa succeeded him). Scott tutored numerous artists including

As a member of the Species Survival Commission of the International Union for Conservation of Nature, he helped create the Red Data books, the group's lists of endangered species.

Scott was the founder President of the Society of Wildlife Artists and President of the Nature in Art Trust (a role in which his wife Philippa succeeded him). Scott tutored numerous artists including Paul Karslake

Paul Karslake FRSA (1958 – 23 March 2020) was a British artist, primarily a painter.

Early life

Karslake was born in Basildon, Essex.

.

From 1973 to 1983, Scott was Chancellor

Chancellor ( la, cancellarius) is a title of various official positions in the governments of many nations. The original chancellors were the of Roman courts of justice—ushers, who sat at the or lattice work screens of a basilica or law cou ...

of the University of Birmingham. In 1979, he was awarded an Honorary Degree (Doctor of Science) from the University of Bath.

Scott continued with his love of sailing, skippering the 12-metre yacht

A yacht is a sailing or power vessel used for pleasure, cruising, or racing. There is no standard definition, though the term generally applies to vessels with a cabin intended for overnight use. To be termed a , as opposed to a , such a pleasu ...

'' Sovereign'' in the 1964 challenge for the America's Cup which was held by the United States. ''Sovereign'' suffered a whitewash 4–0 defeat in a one-sided competition where the American boat was of a noticeably faster design. From 1955 to 1969 he was the president of The International Yacht Racing Union (now World Sailing).

He was one of the founders of the World Wide Fund for Nature (formerly called the World Wildlife Fund), and designed its panda logo. His pioneering work in conservation also contributed greatly to the shift in policy of the International Whaling Commission

The International Whaling Commission (IWC) is a specialised regional fishery management organisation, established under the terms of the 1946 International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling (ICRW) to "provide for the proper conservation ...

and signing of the Antarctic Treaty

russian: link=no, Договор об Антарктике es, link=no, Tratado Antártico

, name = Antarctic Treaty System

, image = Flag of the Antarctic Treaty.svgborder

, image_width = 180px

, caption ...

, the latter inspired by his visit to his father's base on Ross Island in Antarctica.

Scott was a long-time Vice-President of the British Naturalists' Association, whose Peter Scott Memorial Award was instituted after his death, to commemorate his achievements.

He died of a heart attack on 29 August 1989 in Bristol

Bristol () is a city, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England. Situated on the River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Gloucestershire to the north and Somerset to the south. Bristol is the most populous city i ...

, two weeks before his 80th birthday.

Documentaries

Scott narrated '' Wild Wings'', a 1966 British shortdocumentary film

A documentary film or documentary is a non-fictional motion-picture intended to "document reality, primarily for the purposes of instruction, education or maintaining a historical record". Bill Nichols has characterized the documentary in te ...

, produced by British Transport Films. In 1967, it won an Oscar for Best Short Subject at the 39th Academy Awards.

In August 1986, an ITV Special was transmitted by Central Independent Television (Production No.6407) on Scott entitled ''Interest the Boy in Nature'' featuring Konrad Lorenz, Prince Philip, David Attenborough

Sir David Frederick Attenborough (; born 8 May 1926) is an English broadcaster, biologist, natural historian and author. He is best known for writing and presenting, in conjunction with the BBC Natural History Unit, the nine natural histor ...

and Gerald Durrell; written, produced and directed by Robin Brown.

In 1996 Scott's life and work in wildlife conservation was celebrated in a major BBC ''Natural World'' documentary, produced by Andrew Cooper and narrated by Sir David Attenborough. Filmed across three continents from Hawaii to the Russian arctic, ''In the Eye of the Wind'' was the BBC Natural History Unit's tribute to Scott and the organisation he founded, the Wildfowl and Wetland Trust, on its 50th anniversary.

In June 2004, Scott and Sir David Attenborough were jointly profiled in the second of a three-part BBC Two series, ''The Way We Went Wild

The Way We Went Wild is a three-part BBC TV series, first shown on BBC Two, about British wildlife presenters. It was narrated by Josette Simon.

Episode 1

Episode 1, screened on 13 June 2004, featured Johnny Morris and Bill Oddie.

Episode 2

...

'', about television wildlife presenters and were described as being largely responsible for the way that the British and much of the world view wildlife.

Scott's life was also the subject of a BBC Four documentary called ''Peter Scott – A Passion for Nature'' produced in 2006 by Available Light Productions (Bristol).

Loch Ness Monster

In 1962, he co-founded the Loch Ness Phenomena Investigation Bureau with Conservative MPDavid James Dewi, Dai, Dafydd or David James may refer to:

Performers

*David James (actor, born 1839) (1839–1893), English stage comic and a founder of London's Vaudeville Theatre

*David James (actor, born 1967) (born 1967), Australian presenter of ABC's ''P ...

, who had previously been Polar Adviser on the 1948 film '' Scott of the Antarctic'', based on his father's polar expedition. In 1975 Scott proposed the scientific name ''Nessiteras rhombopteryx'' for the Loch Ness Monster (based on a blurred underwater photograph of a supposed fin) so that it could be registered as an endangered species. The name was based on the Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic p ...

for "monster of Ness

Ness or NESS may refer to:

Places Australia

* Ness, Wapengo, a heritage-listed natural coastal area in New South Wales

United Kingdom

* Ness, Cheshire, England, a village

* Ness, Lewis, the most northerly area on Lewis, Scotland, UK

* Cuspate ...

with diamond-shaped fin", but it was later pointed out by ''The Daily Telegraph

''The Daily Telegraph'', known online and elsewhere as ''The Telegraph'', is a national British daily broadsheet newspaper published in London by Telegraph Media Group and distributed across the United Kingdom and internationally.

It was f ...

'' to be an anagram of "Monster hoax by Sir Peter S". Robert H. Rines, who took two supposed pictures of the monster in the 1970s, responded by pointing out that the letters could also be read as an anagram for, "Yes, both pix are monsters, R."Personal life

Scott married the novelist Elizabeth Jane Howard in 1942 and had a daughter, Nicola, born a year later. Howard left Scott in 1946 and they were divorced in 1951.Elizabeth Jane Howard. ''Slipstream'', Macmillan, 2002, page 219 In 1951, Scott married his assistant, Philippa Talbot-Ponsonby, while on an expedition toIceland

Iceland ( is, Ísland; ) is a Nordic island country in the North Atlantic Ocean and in the Arctic Ocean. Iceland is the most sparsely populated country in Europe. Iceland's capital and largest city is Reykjavík, which (along with its ...

in search of the breeding grounds of the pink-footed goose. A daughter, Dafila, was born later in the same year (''dafila'' is the old scientific name for a pintail). She, too, became an artist, painting birds. A son, Falcon, was born in 1954.

Honours and decorations

On 8 July 1941, it was announced that Scott had been mentioned in despatches "for good services in rescuing survivors from a burning Vessel" while serving on HMS ''Broke''. On 2 October 1942, it was announced that he had been further mentioned in despatches "for gallantry, daring and skill in the combined attack on Dieppe". On 1 June 1943, he was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross (DSC) "for skill and gallantry in action with enemy light forces". He was appointedMember of the Order of the British Empire

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry, rewarding contributions to the arts and sciences, work with charitable and welfare organisations,

and public service outside the civil service. It was established ...

(MBE) in the 1942 Birthday Honours. He was promoted to Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) in the 1953 Coronation Honours

The 1953 Coronation Honours were appointments by Queen Elizabeth II to various orders and honours on the occasion of her coronation on 2 June 1953. The honours were published in ''The London Gazette'' on 1 June 1953.New Zealand list:

The reci ...

. He was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II at Buckingham Palace on 27 February 1973. In the 1987 Birthday Honours

Queen's Birthday Honours are announced on or around the date of the Queen's Official Birthday in Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United Kingdom. The dates vary, both from year to year and from country to country. All are published in suppl ...

, he was appointed to the Order of the Companions of Honour (CH) "for services to conservation". In 1987 he was also elected Fellow of the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, r ...

.

Legacy

The fishScotts' wrasse

Scotts' wrasse, ''Cirrhilabrus scottorum'', is a species of wrasse native to the Pacific Ocean, where it occurs at depths of on coral reefs from Australia's Great Barrier Reef to the Pitcairn Islands. It can reach a fish measurement, total leng ...

''Cirrhilabrus scottorum'' was named after Peter and Philippa Scott for their “great contribution in nature conservation".

The ''Peter Scott Walk'' passes the mouth of the River Nene and follows the old sea bank along The Wash

The Wash is a rectangular bay and multiple estuary at the north-west corner of East Anglia on the East coast of England, where Norfolk meets Lincolnshire and both border the North Sea. One of Britain's broadest estuaries, it is fed by the river ...

, from Scott's lighthouse near Sutton Bridge in Lincolnshire to the ferry crossing at King's Lynn.

The ''Sir Peter Scott National Park'' is located in central Jamnagar, in Gujarat, India. Jamnagar also has a ''Sir Peter Scott Bird Hospital''. These institutions in Jamnagar were founded as a result of the friendship between Peter Scott and Jam Sahib

Jam Sahib ( gu, જામ સાહેબ), is the title of the ruling prince of Nawanagar, now known as Jamnagar in Gujarat, an Indian princely state

A princely state (also called native state or Indian state) was a nominally sovereign ...

, the Indian ruler of Jamnagar.

Bibliography

* ''Morning flight.'' Country Life, London 1936–44. * ''Wild chorus.'' Country Life, London 1939. * ''Through the Air.'' (with Michael Bratby). Country Life, London 1941. * ''The battle of the narrow seas.'' Country Life, White Lion & Scribners, London, New York 1945–74. * ''Portrait drawings.'' Country Life, London 1949. * ''Key to the wildfowl of the world.'' Slimbridge 1950. * ''Wild geese and Eskimos.'' Country Life & Scribner, London, New York 1951. * ''A thousand geese.'' Collins, Houghton & Mifflin, London, Boston 1953/54. * ''A coloured key to the wildfowl of the world.'' Royle & Scribner, London, New York 1957–88. * ''Wildfowl of the British Isles.'' Country Life, London 1957. * ''The eye of the wind.'' (autobiography) Hodder, Stoughton & Brockhampton, London, Leicester 1961–77. , * ''Animals in Africa.'' Potter & Cassell, New York, London 1962–65. * ''My favourite stories of wild life.'' Lutterworth 1965. * ''Our vanishing wildlife.'' Doubleday, Garden City 1966. * ''Happy the man.'' Sphere, London 1967. * ''Atlas en couleur des anatidés du monde.'' Le Bélier-Prisma, Paris 1970. * ''The wild swans at Slimbridge.'' Slimbridge 1970. * ''The swans.'' Joseph, Houghton & Mifflin, London, Boston 1972. * ''The amazing world of animals.'' Nelson, Sunbury-on-Thames 1976. * ''Observations of wildlife.'' Phaidon & Cornell, Oxford, Ithaca 1980. , , * ''Travel diaries of a naturalist.'' Collins, London. 3 vols: 1983, 1985, 1987. , , * ''The crisis of the University.'' Croom Helm, London 1984. , * ''Conservation of island birds.'' Cambridge 1985. * ''The art of Peter Scott.'' Sinclair-Stevenson, London 1992 p. m.Forewords

* ''The Red Book – Wildlife in Danger''James Fisher James Fisher may refer to:

Politics

*James Fisher (physician) (died 1822), Scottish-born physician and politician in Lower Canada

*James Hurtle Fisher (1790–1875), South Australian lawyer, first mayor of Adelaide

*James Fisher (Wisconsin politic ...

, Noel Simon & Jack Vincent

Jack Vincent (6 March 1904 – 3 July 1999) was an English ornithologist.

Biography

Vincent was born in London. At age 21 he moved to South Africa where he worked on two farms in the Richmond district of the Natal Province. In the 1920s he ...

, Collins, 1969

** The acknowledgments in this book credit Scott with originating the idea behind it

* ''George Edward Lodge – Unpublished Bird Paintings'' C.A. Fleming ( Michael Joseph) 1983

Illustrations

* * ''Waterfowl of the World'' – with Jean Delacour, Country Life 1954 * Gallico, Paul (1946), '' The Snow Goose'', Michael Joseph, London. Four full-page colour paintings, plus numerous black-and-white line drawings.Films

* '' Wild Wings''Further reading

* ''The Wild Geese of the Newgrounds'' by Paul Walkden. Published by the Friends of WWT Slimbridge, 2009. . Illustrated with colour plates and ink drawing by Peter Scott. Includes chronology. * ''Peter Scott. Collected Writings 1933–1989''. Compiled by Paul Walkden. Published by The Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust 2016. Hardback , E-book . Includes Chronology and Bibliography. Illustrated with photos and b/w illustrations.References

Autobiography

*External links

Article illustrated with his paintings

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Scott, Peter 1909 births 1989 deaths English ornithologists British conservationists English activists Cryptozoologists English television presenters Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust English illustrators 20th-century English painters English male painters 20th-century English writers Fellows of the Royal Society (Statute 12) British stamp designers English male sailors (sport) Sailors at the 1936 Summer Olympics – O-Jolle Olympic sailors of Great Britain Olympic bronze medallists for Great Britain 1964 America's Cup sailors Members of the Order of the Companions of Honour Knights Bachelor Anglo-Scots Gliding in England Glider pilots Chancellors of the University of Birmingham Rectors of the University of Aberdeen Alumni of Trinity College, Cambridge People educated at West Downs School People educated at Oundle School English people of Scottish descent English conservationists British bird artists Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve personnel of World War II Olympic medalists in sailing Camoufleurs 20th-century British zoologists Recipients of the Distinguished Service Cross (United Kingdom) Commanders of the Order of the British Empire Medalists at the 1936 Summer Olympics Peter Presidents of World Sailing English sports executives and administrators Military personnel from London 20th-century English male artists