Persecution of early Christians by the Romans on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The persecution of Christians in the Roman Empire occurred, sporadically and usually locally, throughout the

Early Christian communities were highly inclusive in terms of social stratification and other social categories, much more so than were the

Early Christian communities were highly inclusive in terms of social stratification and other social categories, much more so than were the

Historian Joyce E. Salisbury points out that "The random nature of the persecutions between 64 and 203 has led to much discussion about what constituted the legal basis for the persecutions, and the answer has remained somewhat elusive..."

Historian Joyce E. Salisbury points out that "The random nature of the persecutions between 64 and 203 has led to much discussion about what constituted the legal basis for the persecutions, and the answer has remained somewhat elusive..."

In 250 AD, the emperor Decius issued a decree requiring public sacrifice, a formality equivalent to a testimonial of allegiance to the emperor and the established order. There is no evidence that the decree was intended to target Christians but was intended as a form of loyalty oath. Decius authorized

In 250 AD, the emperor Decius issued a decree requiring public sacrifice, a formality equivalent to a testimonial of allegiance to the emperor and the established order. There is no evidence that the decree was intended to target Christians but was intended as a form of loyalty oath. Decius authorized

In the

In the

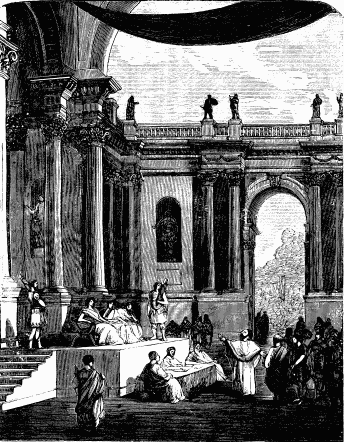

According to Tacitus and later Christian tradition, Nero blamed Christians for the

According to Tacitus and later Christian tradition, Nero blamed Christians for the

Sporadic bouts of anti-Christian activity occurred during the period from the reign of Marcus Aurelius to that of Maximinus. Governors continued to play a more important role than emperors in persecutions during this period.

In the first half of the third century, the relation of Imperial policy and ground-level actions against Christians remained much the same:

Sporadic bouts of anti-Christian activity occurred during the period from the reign of Marcus Aurelius to that of Maximinus. Governors continued to play a more important role than emperors in persecutions during this period.

In the first half of the third century, the relation of Imperial policy and ground-level actions against Christians remained much the same:

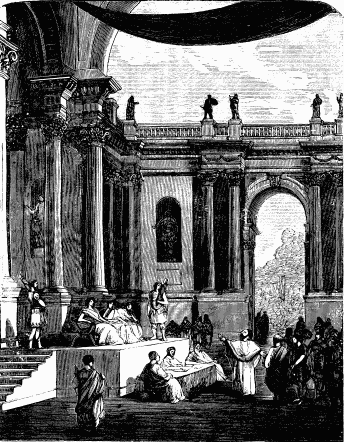

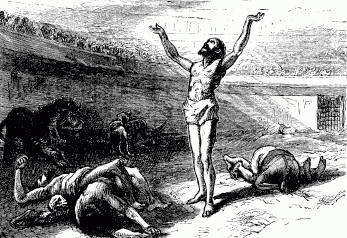

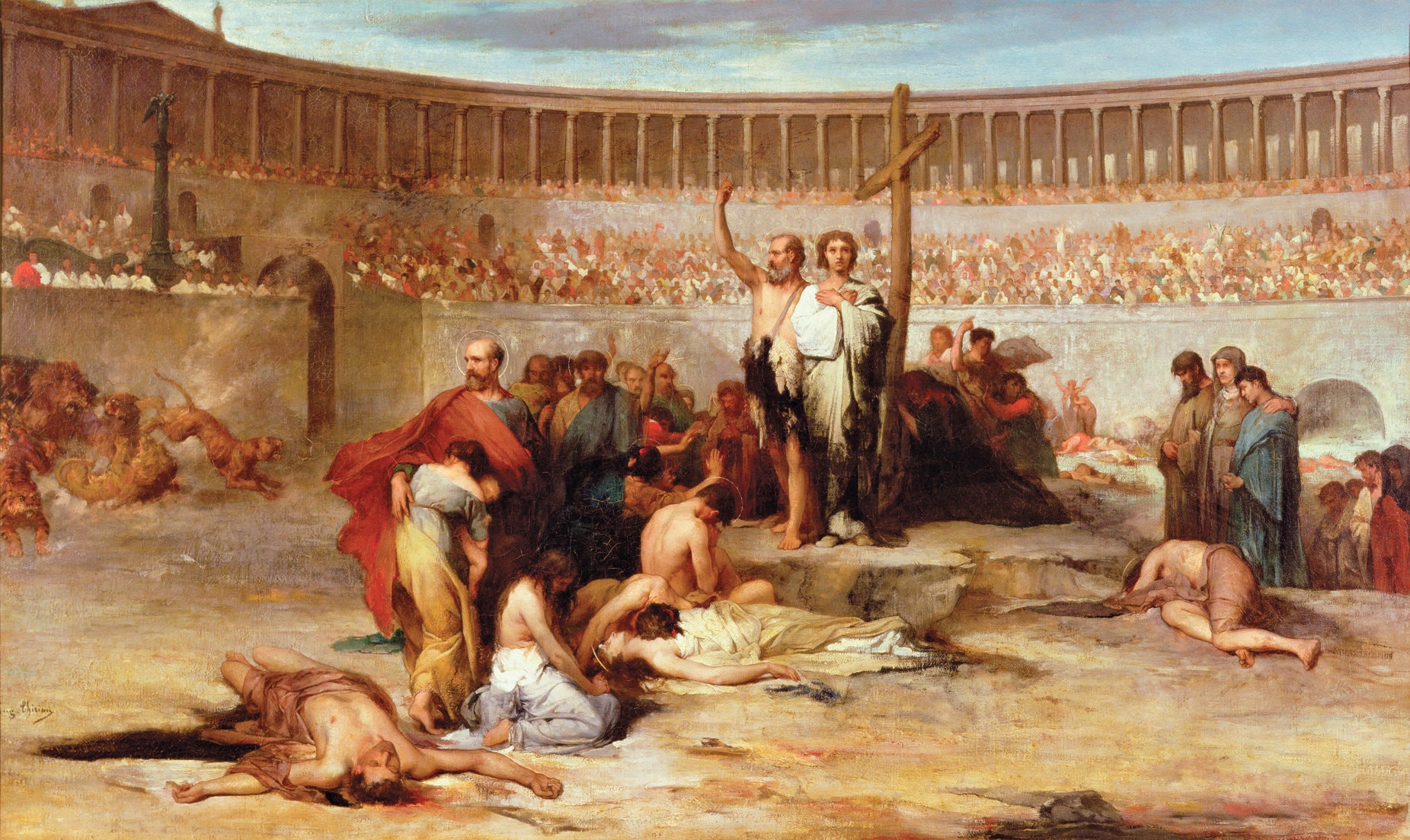

A number of persecutions of Christians occurred in the Roman empire during the reign of

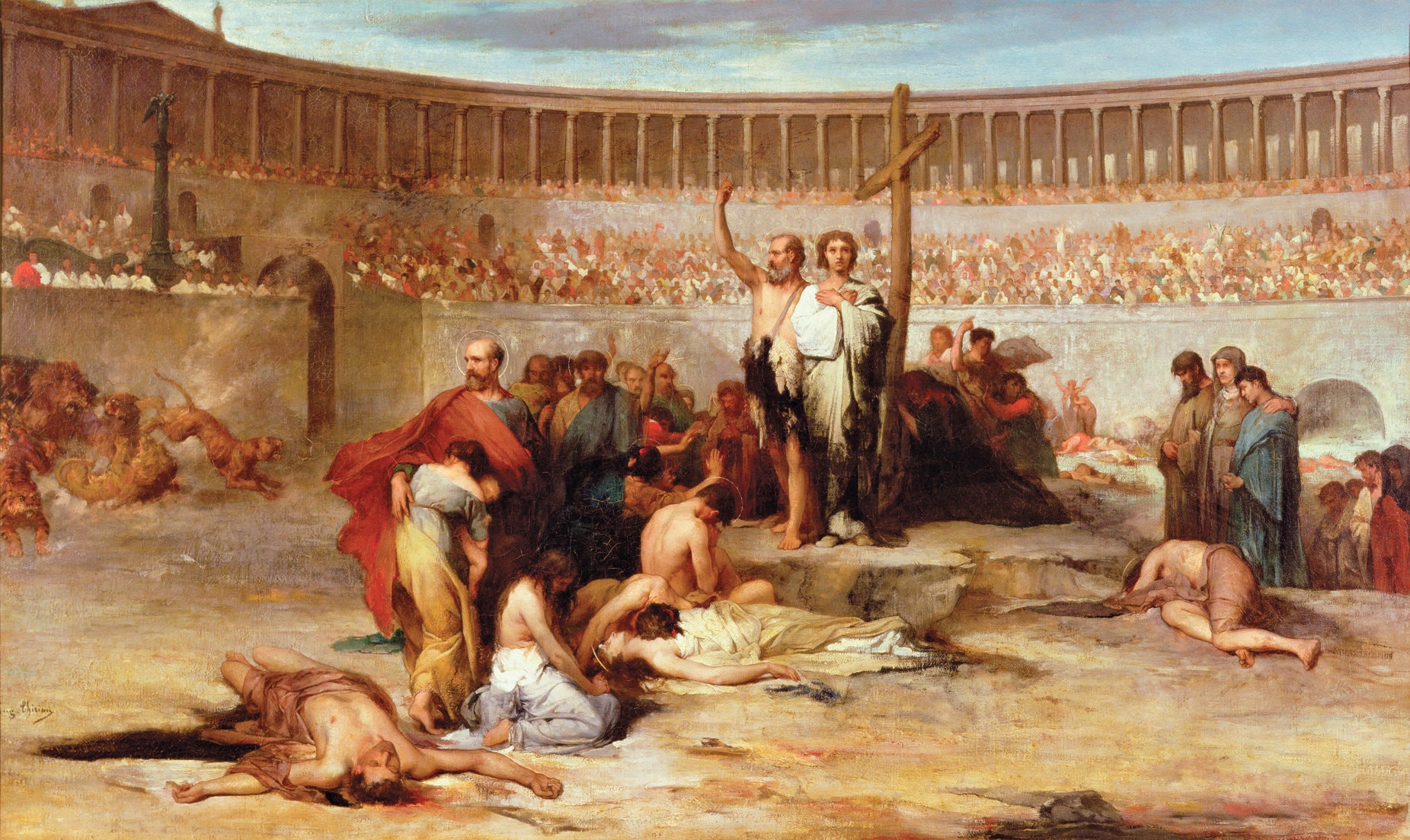

A number of persecutions of Christians occurred in the Roman empire during the reign of  Christians who refused to recant by performing ceremonies to honour the gods were severely penalised. Those who were Roman citizens were exiled or condemned to a swift death by beheading; slaves, foreign-born residents, and lower classes were liable to be put to death by wild beasts as a public spectacle. A variety of animals were used for those condemned to die in this way. Keith Hopkins says that it is disputed whether Christians were executed at the Colisseum at Rome, since no evidence of it has been found yet. Norbert Brockman writes in the ''Encyclopedia of Sacred Places'' that public executions were held at the Colosseum during the period of empire, and that there is no real doubt that Christians were executed there. St. Ignatius was "sent to the beasts by Trajan in 107. Shortly after, 115 Christians were killed by archers. When the Christians refused to pray to the gods for the end of a plague in the latter part of the second century, Marcus Aurelius had thousands killed in the colosseum for blasphemy".

Christians who refused to recant by performing ceremonies to honour the gods were severely penalised. Those who were Roman citizens were exiled or condemned to a swift death by beheading; slaves, foreign-born residents, and lower classes were liable to be put to death by wild beasts as a public spectacle. A variety of animals were used for those condemned to die in this way. Keith Hopkins says that it is disputed whether Christians were executed at the Colisseum at Rome, since no evidence of it has been found yet. Norbert Brockman writes in the ''Encyclopedia of Sacred Places'' that public executions were held at the Colosseum during the period of empire, and that there is no real doubt that Christians were executed there. St. Ignatius was "sent to the beasts by Trajan in 107. Shortly after, 115 Christians were killed by archers. When the Christians refused to pray to the gods for the end of a plague in the latter part of the second century, Marcus Aurelius had thousands killed in the colosseum for blasphemy".

"The "Afterlife" of the New Testament and Postmodern Interpretation''

lecture transcript

). Yale University. Provincial governors had a great deal of personal discretion in their jurisdictions and could choose themselves how to deal with local incidents of persecution and mob violence against Christians. For most of the first three hundred years of Christian history, Christians were able to live in peace, practice their professions, and rise to positions of responsibility. In 250 AD, an empire-wide persecution took place as an indirect consequence of an edict by the emperor In 250 the emperor

In 250 the emperor

The emperor Valerian took the throne in 253 but from the following year he was away from Rome fighting the

The emperor Valerian took the throne in 253 but from the following year he was away from Rome fighting the

Theologian Paul Middleton writes that:

Theologian Paul Middleton writes that:

Eusebius' authenticity has also been an aspect of this long debate. Eusebius is biased, and Barnes says Eusebius makes mistakes, particularly of chronology, (and through excess devotion to Constantine), but many of his claims are accepted as dependable due largely to his method which includes carefully quoted comprehensive excerpts from original sources that are now lost. For example, Eusebius claims that, "while Marcus was associated with iusin the imperial power 38 to 161 Pius wrote oncerning the criminal nature of being Christianto the cities of Larisa, Thessalonica, and Athens and to all the Greeks ... Eusebius cites ''Melito's Apology'' for corroboration, and the manuscript of Justin's Apologies presents the same alleged imperial letter, with only minor variations in the text. The principle that Christians are ''eo ipso'' criminals is well attested in the years immediately after 161. It is assumed in the imperial letter concerning the Gallic Christians, is attacked by Melito in his Apology, and seems to have provided the charge upon which Justin and his companions were tried and executed between 161 and 168". According to Barnes, Eusebius is thus supported in much of what he says.

Eusebius' authenticity has also been an aspect of this long debate. Eusebius is biased, and Barnes says Eusebius makes mistakes, particularly of chronology, (and through excess devotion to Constantine), but many of his claims are accepted as dependable due largely to his method which includes carefully quoted comprehensive excerpts from original sources that are now lost. For example, Eusebius claims that, "while Marcus was associated with iusin the imperial power 38 to 161 Pius wrote oncerning the criminal nature of being Christianto the cities of Larisa, Thessalonica, and Athens and to all the Greeks ... Eusebius cites ''Melito's Apology'' for corroboration, and the manuscript of Justin's Apologies presents the same alleged imperial letter, with only minor variations in the text. The principle that Christians are ''eo ipso'' criminals is well attested in the years immediately after 161. It is assumed in the imperial letter concerning the Gallic Christians, is attacked by Melito in his Apology, and seems to have provided the charge upon which Justin and his companions were tried and executed between 161 and 168". According to Barnes, Eusebius is thus supported in much of what he says.

Martyrdom and Persecution in the Early Church

A Study of a Conflict from the Maccabees to Donatus''. Cambridge: James Clarke & Co. * * * de Ste. Croix, G.E.M. (2006). "Why Were The Early Christians Persecuted?". ''A Journal of Historical Studies'', 1963: 6–38. Page references in this article relate to a reprint of this essay in * *

Early Church History Timeline

{{Religious persecution * Ante-Nicene Christian martyrs

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post- Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediter ...

, beginning in the 1st century CE and ending in the 4th century CE. Originally a polytheistic

Polytheism is the belief in multiple deities, which are usually assembled into a pantheon of gods and goddesses, along with their own religious sects and rituals. Polytheism is a type of theism. Within theism, it contrasts with monotheism, the ...

empire in the traditions of Roman paganism

Religion in ancient Rome consisted of varying imperial and provincial religious practices, which were followed both by the people of Rome as well as those who were brought under its rule.

The Romans thought of themselves as highly religious, ...

and the Hellenistic religion, as Christianity spread through the empire, it came into ideological conflict with the imperial cult of ancient Rome

The Roman imperial cult identified emperors and some members of their families with the divinely sanctioned authority ('' auctoritas'') of the Roman State. Its framework was based on Roman and Greek precedents, and was formulated during the ear ...

. Pagan practices such as making sacrifices

Sacrifice is the offering of material possessions or the lives of animals or humans to a deity as an act of propitiation or worship. Evidence of ritual animal sacrifice has been seen at least since ancient Hebrews and Greeks, and possibly exis ...

to the deified emperors or other gods were abhorrent to Christians as their beliefs prohibited idolatry. The state and other members of civic society punished Christians for treason, various rumored crimes, illegal assembly, and for introducing an alien cult that led to Roman apostasy

Apostasy (; grc-gre, ἀποστασία , 'a defection or revolt') is the formal disaffiliation from, abandonment of, or renunciation of a religion by a person. It can also be defined within the broader context of embracing an opinion that ...

.

The first, localized Neronian persecution

The persecution of Christians in the Roman Empire occurred, sporadically and usually locally, throughout the Roman Empire, beginning in the 1st century CE and ending in the 4th century CE. Originally a polytheistic empire in the traditions of Ro ...

occurred under the emperor Nero

Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus ( ; born Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus; 15 December AD 37 – 9 June AD 68), was the fifth Roman emperor and final emperor of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, reigning from AD 54 unti ...

() in Rome. A more general persecution occurred during the reign of Marcus Aurelius

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (Latin: áːɾkus̠ auɾέːli.us̠ antɔ́ːni.us̠ English: ; 26 April 121 – 17 March 180) was Roman emperor from 161 to 180 AD and a Stoic philosopher. He was the last of the rulers known as the Five Good ...

(). After a lull, persecution resumed under the emperors Decius

Gaius Messius Quintus Traianus Decius ( 201 ADJune 251 AD), sometimes translated as Trajan Decius or Decius, was the emperor of the Roman Empire from 249 to 251.

A distinguished politician during the reign of Philip the Arab, Decius was procl ...

() and Trebonianus Gallus

Gaius Vibius Trebonianus Gallus (206 – August 253) was Roman emperor from June 251 to August 253, in a joint rule with his son Volusianus.

Early life

Gallus was born in Italy, in a family with respected Etruscan senatorial background. He h ...

(). The Decian persecution

The Decian persecution of Christians occurred in 250 AD under the Roman Emperor Decius. He had issued an edict ordering everyone in the Empire to perform a sacrifice to the Roman gods and the well-being of the emperor. The sacrifices had to ...

was particularly extensive. The persecution of Emperor Valerian () ceased with his notable capture by the Sasanian Empire's Shapur I

Shapur I (also spelled Shabuhr I; pal, 𐭱𐭧𐭯𐭥𐭧𐭥𐭩, Šābuhr ) was the second Sasanian King of Kings of Iran. The dating of his reign is disputed, but it is generally agreed that he ruled from 240 to 270, with his father Ardas ...

() at the Battle of Edessa

The Battle of Edessa took place between the armies of the Roman Empire under the command of Emperor Valerian and Sasanian forces under Shahanshah (King of the Kings) Shapur I in 260. The Roman army was defeated and captured in its entirety ...

during the Roman–Persian Wars

The Roman–Persian Wars, also known as the Roman–Iranian Wars, were a series of conflicts between states of the Greco-Roman world and two successive Iranian empires: the Parthian and the Sasanian. Battles between the Parthian Empire and the ...

. His successor Gallienus

Publius Licinius Egnatius Gallienus (; c. 218 – September 268) was Roman emperor with his father Valerian from 253 to 260 and alone from 260 to 268. He ruled during the Crisis of the Third Century that nearly caused the collapse of the empi ...

() halted the persecutions.

The ''Augustus

Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Roman Pr ...

'' Diocletian () began the Diocletianic persecution

The Diocletianic or Great Persecution was the last and most severe persecution of Christians in the Roman Empire. In 303, the emperors Diocletian, Maximian, Galerius, and Constantius issued a series of edicts rescinding Christians' legal rig ...

, the final general persecution of Christians, which continued to be enforced in parts of the empire until the ''Augustus'' Galerius

Gaius Galerius Valerius Maximianus (; 258 – May 311) was Roman emperor from 305 to 311. During his reign he campaigned, aided by Diocletian, against the Sasanian Empire, sacking their capital Ctesiphon in 299. He also campaigned across th ...

() issued the Edict of Serdica

The Edict of Serdica, also called Edict of Toleration by Galerius, was issued in 311 in Serdica (now Sofia, Bulgaria) by Roman Emperor Galerius. It officially ended the Diocletianic Persecution of Christianity in the Eastern Roman Empire.

The E ...

and the ''Augustus'' Maximinus Daia

Galerius Valerius Maximinus, born as Daza (20 November 270 – July 313), was Roman emperor from 310 to 313 CE. He became embroiled in the Civil wars of the Tetrarchy between rival claimants for control of the empire, in which he was defeated ...

() died. After Constantine the Great

Constantine I ( , ; la, Flavius Valerius Constantinus, ; ; 27 February 22 May 337), also known as Constantine the Great, was Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337, the first one to convert to Christianity. Born in Naissus, Dacia Mediterran ...

() defeated his rival Maxentius () at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge in October 312, he and his co-emperor Licinius

Valerius Licinianus Licinius (c. 265 – 325) was Roman emperor from 308 to 324. For most of his reign he was the colleague and rival of Constantine I, with whom he co-authored the Edict of Milan, AD 313, that granted official toleration to C ...

issued the Edict of Milan

The Edict of Milan ( la, Edictum Mediolanense; el, Διάταγμα τῶν Μεδιολάνων, ''Diatagma tōn Mediolanōn'') was the February 313 AD agreement to treat Christians benevolently within the Roman Empire. Frend, W. H. C. ( ...

(313), which permitted all religions, including Christianity, to be tolerated.

Religion in Roman society

Roman religion at the beginning of Roman Empire (27 BCE - 476 CE) was polytheistic and local. Each city worshipped its own set of gods and goddesses that had originally been derived fromancient Greece

Ancient Greece ( el, Ἑλλάς, Hellás) was a northeastern Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of Classical Antiquity, classical antiquity ( AD 600), th ...

and become Romanized. This polis-religion was embedded in, and inseparable from, "the general structures of the ancient city; there was no religious identity separate from political or civic identity, and the essence of religion lay in ritual rather than belief". Private religion and its public practices were under the control of public officials, primarily, the Senate. Religion was central to being Roman, its practices widespread, and intertwined with politics.

Support for this form of traditional Roman polytheism had begun to decline by the first century BCE when it was seen, according to various writers and historians of the time, as having become empty and ineffectual. A combination of external factors such as war and invasions, and internal factors such as the formal nature and political manipulation of traditional religion, is said to have created the slow decline of polytheism. This left a vacuum in the personal lives of people that they filled with other forms of worship: such as the imperial cult

An imperial cult is a form of state religion in which an emperor or a dynasty of emperors (or rulers of another title) are worshipped as demigods or deities. "Cult" here is used to mean "worship", not in the modern pejorative sense. The cult may ...

, various mystery cults

Mystery religions, mystery cults, sacred mysteries or simply mysteries, were religious schools of the Greco-Roman world for which participation was reserved to initiates ''(mystai)''. The main characterization of this religion is the secrecy a ...

, imported eastern religions, and Christianity.

The Roman approach to empire building included a cultural permeability that allowed foreigners to become a part of it, but the Roman religious practice of adopting foreign gods and practices into its pantheon did not apply equally to all gods: "Many divinities were brought to Rome and installed as part of the Roman state religion, but a great many more were not". This characteristic openness has led many, such as Ramsay MacMullen

Ramsay MacMullen (March 3, 1928 – November 28, 2022) was an American historian who was Emeritus Professor of History at Yale University, where he taught from 1967 to his retirement in 1993 as Dunham Professor of History and Classics. His scholar ...

to say that in its process of expansion, the Roman Empire was "completely tolerant, in heaven as on earth", but to also go on and immediately add: "That olerancewas only half the story".

MacMullen says the most significant factor in determining whether one received 'tolerance' or 'intolerance' from Roman religion was if that religion honored one's god "according to ancestral custom". Christians were thought of badly for abandoning their ancestral roots in Judaism. However, how a religion practiced was also a factor. Roman officials had become suspicious of the worshippers of Dionysus

In ancient Greek religion and myth, Dionysus (; grc, Διόνυσος ) is the god of the grape-harvest, winemaking, orchards and fruit, vegetation, fertility, insanity, ritual madness, religious ecstasy, festivity, and theatre. The Roma ...

and their practice of Bacchanalia

The Bacchanalia were unofficial, privately funded popular Roman festivals of Bacchus, based on various ecstatic elements of the Greek Dionysia. They were almost certainly associated with Rome's native cult of Liber, and probably arrived in Rome ...

as far back as 186 BCE because it "took place at night". Private divination, astrology, and 'Chaldean practices' were magics associated with night worship, and as such, had carried the threat of banishment and execution since the early imperial period. Archaeologist Luke Lavan explains that is because night worship was private and secret and associated with treason and secret plots against the emperor. Bacchic associations were dissolved, leaders were arrested and executed, women were forbidden to hold important positions in the cult, no Roman citizen could be a priest, and strict control of the cult was thereafter established.

This became the pattern for the Roman state's response to whatever was seen as a religious threat. In the first century of the common era, there were "periodic expulsions of astrologers, philosophers and even teachers of rhetoric... as well as Jews and...the cult of Isis". Druids also received the same treatment, as did Christians.

Reasons, causes and contributing factors

Reasons

A. N. Sherwin-White

Adrian Nicholas Sherwin-White, FBA (10 August 1911 – 1November 1993) was a British academic and ancient historian. He was a fellow of St John's College, University of Oxford and President of the Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies. ...

records that serious discussion of the reasons for Roman persecution of Christians began in 1890, when it produced "20 years of controversy" and three main opinions: first, there was the theory held by most French and Belgian scholars that "there was a general enactment, precisely formulated and valid for the whole empire, which forbade the practice of the Christian religion. The origin of this is most commonly attributed to Nero, but sometimes to Domitian". This has evolved into a 'common law' theory which gives great weight to Tertullian's description of prosecution resulting from the 'accusation of the Name', as being Nero's plan. Nero had an older resolution forbidding the introduction of new religions, but the application to Christians is seen as coming from the much older Republican principle that it was a capital offense to introduce a new ''superstition'' without the authorization of the Roman state. Sherwin-White adds that this theory might explain persecution at Rome, but it fails to explain it in the provinces. For that, a second theory is needed.

The second theory, which originated with German scholars, and is the best known theory to English readers, is that of '' coercitio'' (curtailment). It holds that Christians were punished by Roman governors through the ordinary use of their power to keep order, because Christians had introduced "an alien cult which induced 'national apostasy', ndthe abandonment of the traditional Roman religion. Others substituted for this a general aversion to the established order and disobedience to constituted authority. All of his

His or HIS may refer to:

Computing

* Hightech Information System, a Hong Kong graphics card company

* Honeywell Information Systems

* Hybrid intelligent system

* Microsoft Host Integration Server

Education

* Hangzhou International School, in ...

school seem to envisage the procedure as direct police action, or inquisition against notable malefactors, arrest, and punishment, without the ordinary forms of trial".

A third school asserted that Christians were prosecuted for specific criminal offenses such as child-murder, incest, magic, illegal assembly, and treason – a charge based on their refusal to worship the divinity of the Roman emperor. Sherwin-White says "this third opinion has usually been combined with the coercitio theory, but some scholars have attributed all Christian persecution to a single criminal charge, notably treason, or illegal assembly, or the introduction of an alien cult". In spite of the fact that malicious rumors did exist, this theory has been the least verified of the three by later scholarship.

Social and religious causes

Ideological conflict

Classics professor emeritus Joseph Plescia says persecution was caused by an ideological conflict. Caesar was seen as divine. Christians could accept only one divinity, and it wasn't Caesar. Cairns describes the ideological conflict as: "The exclusive sovereignty of Christ clashed with Caesar's claims to his own exclusive sovereignty." In this clash of ideologies, "the ordinary Christian lived under a constant threat ofdenunciation

Denunciation (from Latin ''denuntiare'', "to denounce") is the act of publicly assigning to a person the blame for a perceived wrongdoing, with the hope of bringing attention to it.

Notably, centralized social control in authoritarian states re ...

and the possibility of arraignment on capital charges".Barnes 1968. Joseph Bryant asserts it was not easy for Christians to hide their religion and pretend to ''Romanness'' either, since renunciation of the world was an aspect of their faith that demanded "numerous departures from conventional norms and pursuits". The Christian had exacting moral standards that included avoiding contact with those that still lay in bondage to 'the Evil One' ( 2 Corinthians 6:1-18; 1 John 2: 15-18; Revelation 18: 4; II Clement 6; Epistle of Barnabas, 1920). Life as a Christian required daily courage, "with the radical choice of Christ or the world being forced upon the believer in countless ways"."Christian attendance at civic festivals, athletic games, and theatrical performances were fraught with danger, since in addition to the 'sinful frenzy' and 'debauchery' aroused, each was held in honour of pagan deities. Various occupations and careers were regarded as inconsistent with Christian principles, most notably military service and public office, the manufacturing of idols, and of course all pursuits which affirmed polytheistic culture, such as music, acting, and school-teaching (cf. Hippolytus, Apostolic Tradition 16). Even the wearing of jewelry and fine apparel was judged harshly by Christian moralists and ecclesiastical officials, as was the use of cosmetics and perfumes".In Rome, citizens were expected to demonstrate their loyalty to Rome by participating in the rites of the state religion which had numerous feast days, processions and offerings throughout the year. Christians simply could not, and so they were seen as belonging to an illicit religion that was anti-social and subversive.

Privatizing

McDonald explains that the privatizing of religion was another factor in persecution as "Christians moved their activities from the streets to the more secluded domains of houses, shops and women's apartments...severing the normal ties between religion, tradition and public institutions like cities and nations". McDonald adds that Christians sometimes "met at night, in secret, and this also aroused suspicion among the pagan population accustomed to religion as a public event; rumors abounded that Christians committed ''flagitia'', ''scelera'', and ''maleficia''— "outrageous crimes", "wickedness", and "evil deeds", specifically, cannibalism andincest

Incest ( ) is human sexual activity between family members or close relatives. This typically includes sexual activity between people in consanguinity (blood relations), and sometimes those related by affinity (marriage or stepfamily), adopti ...

(referred to as " Thyestian banquets" and " Oedipodean intercourse") — due to their rumored practices of eating the "blood and body" of Christ and referring to each other as "brothers" and "sisters"."Sherwin-White, A.N. "Why Were the Early Christians Persecuted? – An Amendment." Past & Present. Vol. 47 No. 2 (April 1954): 23.de Ste Croix 2006

Inclusivity

Early Christian communities were highly inclusive in terms of social stratification and other social categories, much more so than were the

Early Christian communities were highly inclusive in terms of social stratification and other social categories, much more so than were the Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

voluntary associations. Heterogeneity

Homogeneity and heterogeneity are concepts often used in the sciences and statistics relating to the uniformity of a substance or organism. A material or image that is homogeneous is uniform in composition or character (i.e. color, shape, siz ...

characterized the groups formed by Paul the Apostle, and the role of women

A woman is an adult female human. Prior to adulthood, a female human is referred to as a girl (a female child or adolescent). The plural ''women'' is sometimes used in certain phrases such as "women's rights" to denote female humans regardl ...

was much greater than in either of the forms of Judaism or paganism in existence at the time. Early Christians were told to love others, even enemies, and Christians of all classes and sorts called each other "brother

A brother is a man or boy who shares one or more parents with another; a male sibling. The female counterpart is a sister. Although the term typically refers to a familial relationship, it is sometimes used endearingly to refer to non-familia ...

" and "sister

A sister is a woman or a girl who shares one or more parents with another individual; a female sibling. The male counterpart is a brother. Although the term typically refers to a family, familial relationship, it is sometimes used endearingly to r ...

". This inclusivity of various social classes and backgrounds stems from early Christian beliefs in the importance of performing missionary work among Jews and gentiles in hopes of converting to a new way of life in accordance of gospel standards (''Mark 16:15-16, Galatians 5:16-26''). This was perceived by the opponents of Christianity as a "disruptive and, most significantly, a competitive menace to the traditional class/gender based order of Roman society".

Exclusivity

Edward Gibbon

Edward Gibbon (; 8 May 173716 January 1794) was an English historian, writer, and member of parliament. His most important work, '' The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire'', published in six volumes between 1776 and 1788, is ...

argued that the tendency of Christian converts to renounce their family and country, (and their frequent predictions of impending disasters), instilled a feeling of apprehension in their pagan neighbors. He wrote:By embracing the faith of the Gospel the Christians incurred the supposed guilt of an unnatural and unpardonable offence. They dissolved the sacred ties of custom and education, violated the religious institutions of their country, and presumptuously despised whatever their fathers had believed as true, or had reverenced as sacred.

Rejection of paganism

Many pagans believed that bad things would happen if the established pagan gods were not properly propitiated and reverenced. Bart Ehrman says that: "By the end of the second century, the Christian apologistTertullian

Tertullian (; la, Quintus Septimius Florens Tertullianus; 155 AD – 220 AD) was a prolific early Christian author from Carthage in the Roman province of Africa. He was the first Christian author to produce an extensive corpus of L ...

complained about the widespread perception that Christians were the source of all disasters brought against the human race by the gods.They think the Christians the cause of every public disaster, of every affliction with which the people are visited. If the Tiber rises as high as the city walls, if the Nile does not send its waters up over the fields, if the heavens give no rain, if there is an earthquake, if there is famine or pestilence, straightway the cry is, 'Away with the Christians to the lions'!"

Roman identity

Roman religion was largely what determined ''Romanness''. See Harold Remus in Blasi, Anthony J., Jean Duhamel and Paul-Andre' Turcotte, eds. Handbook of Early Christianity (2002) 433 and 431-452 for an updated summary of scholarship on Roman persecution of Christianity. Also J. D. Crossan Who Killed Jesus (1995) 25 The Christian refusal to sacrifice to the Roman gods was seen as an act of defiance against this cultural and political characteristic and the very nature of Rome itself. MacMullen quotes Eusebius as having written that the pagans "have thoroughly persuaded themselves that they act rightly and that we are guilty of the greatest impiety". According to Wilken, "The polytheistic worldview of the Romans did not incline them to understand a refusal to worship, even symbolically, the state gods.". MacMullen explains this meant Christians were "constantly on the defensive", and although they responded with appeals to philosophy and reason and anything they thought might weigh against ''ta patria'' (the ancestral customs), they could not practice Roman religion and continue fealty to their own religion.Abel Bibliowicz

Abel ''Hábel''; ar, هابيل, Hābīl is a Biblical figure in the Book of Genesis within Abrahamic religions. He was the younger brother of Cain, and the younger son of Adam and Eve, the first couple in Biblical history. He was a shepherd w ...

says that, amongst the Romans, "The prejudice became so instinctive that eventually, mere confession of the name 'Christian' could be sufficient grounds for execution".

Contributing factors

Roman legal system

Historian Joyce E. Salisbury points out that "The random nature of the persecutions between 64 and 203 has led to much discussion about what constituted the legal basis for the persecutions, and the answer has remained somewhat elusive..."

Historian Joyce E. Salisbury points out that "The random nature of the persecutions between 64 and 203 has led to much discussion about what constituted the legal basis for the persecutions, and the answer has remained somewhat elusive..." Candida Moss

Candida R. Moss (born 26 November 1978) is an English public intellectual, journalist, New Testament scholar and historian of Christianity, who is the Edward Cadbury Professor of Theology in the Department of Theology and Religion at the Univers ...

says there is "scant" evidence of martyrdom when using Roman Law as the measure. Historian Joseph Plescia asserts that the first evidence of Roman law concerning Christians is that of Trajan. T. D. Barnes and Ste. Croix both argue there was no Roman law concerning the Christians before Decius

Gaius Messius Quintus Traianus Decius ( 201 ADJune 251 AD), sometimes translated as Trajan Decius or Decius, was the emperor of the Roman Empire from 249 to 251.

A distinguished politician during the reign of Philip the Arab, Decius was procl ...

and the third century; Barnes agrees that the central fact of the juridical basis of the persecutions is Trajan's rescript to Pliny; after Trajan's rescript, (if not before), Christianity became a crime in a special category.

Other scholars trace the precedent for killing Christians to Nero. Barnes explains that, though there was no Roman law, there was "ample precedent for suppressing foreign superstitions" prior to Nero. Precedent was based on strong feeling that only the ancestral Gods ought to be worshipped. Such feeling could "acquire the force of law", since the ancestral customs – the '' Mos maiorum'' – were the most important source of Roman law. In Joseph Bryant's view, "Nero's mass executions ... set uch

Uch ( pa, ;

ur, ), frequently referred to as Uch Sharīf ( pa, ;

ur, ; ''"Noble Uch"''), is a historic city in the southern part of Pakistan's Punjab province. Uch may have been founded as Alexandria on the Indus, a town founded by Alexan ...

a precedent, and thereafter the mere fact of 'being a Christian' was sufficient for state officials to impose capital punishment". Barnes says "Keresztes, goes so far as to claim that 'there is today an almost general agreement that the Christians, under normal circumstances, were not tried on the basis of either the ''ius coercitionis'' the governor's 'power of arrest') or the general criminal law, but on the basis of a special law introduced during Nero's rule, proscribing Christians as such". This theory gives great weight to Tertullian, and Nero's older resolution forbidding the introduction of new religions, and the even older Republican principle that it was a capital offense to introduce a new superstition without the authorization of the Roman state.

Bryant agrees, adding that, "This situation is strikingly illustrated in the famous correspondence between Emperor Trajan (98-117) and Pliny the Younger". Trajan's correspondence with Pliny does indeed show that Christians were being executed for being Christian before 110 AD, yet Pliny's letters also show there was no empire–wide Roman law, making Christianity a crime, that was generally known at that time. Herbert Musurillo, translator and scholar of ''The Acts of the Christian martyrs Introduction'' says Ste. Croix asserted the governor's special powers were all that was needed.

Due to the informal and personality-driven nature of the Roman legal system, nothing "other than a prosecutor" (an accuser, including a member of the public, not only a holder of an official position), "a charge of Christianity, and a governor willing to punish on that charge" was required to bring a legal case against a Christian. Roman law was largely concerned with property rights, leaving many gaps in criminal and public law. Thus the process ''cognitio extra ordinem'' ("special investigation") filled the legal void left by both code and court. All provincial governors had the right to run trials in this way as part of their ''imperium

In ancient Rome, ''imperium'' was a form of authority held by a citizen to control a military or governmental entity. It is distinct from '' auctoritas'' and '' potestas'', different and generally inferior types of power in the Roman Republic a ...

'' in the province.

In ''cognitio extra ordinem'', an accuser called a ''delator

Delator (plural: ''delatores'', feminine: ''delatrix'') is Latin for a denouncer, one who indicates to a court another as having committed a punishable deed.

Secular Roman law

In Roman history, it was properly one who gave notice (''deferre'') t ...

'' brought before the governor an individual to be charged with a certain offense—in this case, that of being a Christian. This delator was prepared to act as the prosecutor for the trial, and could be rewarded with some of the accused's property if he made an adequate case or charged with ''calumnia'' (malicious prosecution

Malicious prosecution is a common law intentional tort. Like the tort of abuse of process, its elements include (1) intentionally (and maliciously) instituting and pursuing (or causing to be instituted or pursued) a legal action ( civil or crimin ...

) if his case was insufficient. If the governor agreed to hear the case—and he was free not to—he oversaw the trial from start to finish: he heard the arguments, decided on the verdict, and passed the sentence. Christians sometimes offered themselves up for punishment, and the hearings of such voluntary martyrs were conducted in the same way.

More often than not, the outcome of the case was wholly subject to the governor's personal opinion. While some tried to rely on precedent or imperial opinion where they could, as evidenced by Pliny the Younger's letter to Trajan concerning the Christians, such guidance was often unavailable.Barnes 1968. In many cases months' and weeks' travel away from Rome, these governors had to make decisions about running their provinces according to their own instincts and knowledge.

Even if these governors had easy access to the city, they would not have found much official legal guidance on the matter of the Christians. Before the anti-Christian policies under Decius

Gaius Messius Quintus Traianus Decius ( 201 ADJune 251 AD), sometimes translated as Trajan Decius or Decius, was the emperor of the Roman Empire from 249 to 251.

A distinguished politician during the reign of Philip the Arab, Decius was procl ...

beginning in 250, there was no empire-wide edict against the Christians, and the only solid precedent was that set by Trajan in his reply to Pliny: the name of "Christian" alone was sufficient grounds for punishment and Christians were not to be sought out by the government. There is speculation that Christians were also condemned for contumacia—disobedience toward the magistrate, akin to the modern "contempt of court"—but the evidence on this matter is mixed. Melito of Sardis

Melito of Sardis ( el, Μελίτων Σάρδεων ''Melítōn Sárdeōn''; died ) was the bishop of Sardis near Smyrna in western Anatolia, and a great authority in early Christianity. Melito held a foremost place in terms of bishops in Asia ...

later asserted that Antoninus Pius

Antoninus Pius ( Latin: ''Titus Aelius Hadrianus Antoninus Pius''; 19 September 86 – 7 March 161) was Roman emperor from 138 to 161. He was the fourth of the Five Good Emperors from the Nerva–Antonine dynasty.

Born into a senatori ...

ordered that Christians were not to be executed without proper trial.

Given the lack of guidance and distance of imperial supervision, the outcomes of the trials of Christians varied widely. Many followed Pliny's formula: they asked if the accused individuals were Christians, gave those who answered in the affirmative a chance to recant, and offered those who denied or recanted a chance to prove their sincerity by making a sacrifice to the Roman gods and swearing by the emperor's genius

Genius is a characteristic of original and exceptional insight in the performance of some art or endeavor that surpasses expectations, sets new standards for future works, establishes better methods of operation, or remains outside the capabili ...

. Those who persisted were executed.

According to the Christian apologist Tertullian

Tertullian (; la, Quintus Septimius Florens Tertullianus; 155 AD – 220 AD) was a prolific early Christian author from Carthage in the Roman province of Africa. He was the first Christian author to produce an extensive corpus of L ...

, some governors in Africa helped accused Christians secure acquittals or refused to bring them to trial. Overall, Roman governors were more interested in making apostates than martyrs: one proconsul of Asia, Arrius Antoninus, when confronted with a group of voluntary martyrs during one of his assize tours, sent a few to be executed and snapped at the rest, "If you want to die, you wretches, you can use ropes or precipices."

During the Great Persecution

The Diocletianic or Great Persecution was the last and most severe persecution of Christians in the Roman Empire. In 303, the emperors Diocletian, Maximian, Galerius, and Constantius issued a series of edicts rescinding Christians' legal rights ...

which lasted from 303 to 312/313, governors were given direct edicts from the emperor. Christian churches and texts were to be destroyed, meeting for Christian worship was forbidden, and those Christians who refused to recant lost their legal rights. Later, it was ordered that Christian clergy be arrested and that all inhabitants of the empire sacrifice to the gods. Still, no specific punishment was prescribed by these edicts and governors retained the leeway afforded to them by distance. Lactantius reported that some governors claimed to have shed no Christian blood,De Ste Croix, "Aspects of the 'Great' Persecution," 103. and there is evidence that others turned a blind eye to evasions of the edict or only enforced it when absolutely necessary.

Government motivation

When a governor was sent to a province, he was charged with the task of keeping it ''pacata atque quieta''—settled and orderly. His primary interest would be to keep the populace happy; thus when unrest against the Christians arose in his jurisdiction, he would be inclined to placate it with appeasement lest the populace "vent itself in riots and lynching." Political leaders in the Roman Empire were also public cult leaders.Roman religion

Religion in ancient Rome consisted of varying imperial and provincial religious practices, which were followed both by the people of Rome as well as those who were brought under its rule.

The Romans thought of themselves as highly religious, ...

revolved around public ceremonies and sacrifices; personal belief was not as central an element as it is in many modern faiths. Thus while the private beliefs of Christians may have been largely immaterial to many Roman elites, this public religious practice was in their estimation critical to the social and political well-being of both the local community and the empire as a whole. Honoring tradition in the right way – ''pietas

''Pietas'' (), translated variously as "duty", "religiosity" or "religious behavior", "loyalty", "devotion", or "filial piety" (English "piety" derives from the Latin), was one of the chief virtues among the ancient Romans. It was the distingui ...

'' – was key to stability and success. Hence the Romans protected the integrity of cults practiced by communities under their rule, seeing it as inherently correct to honor one's ancestral traditions; for this reason the Romans for a long time tolerated the highly exclusive Jewish sect, even though some Romans despised it. Historian H. H. Ben-Sasson has proposed that the "Crisis under Caligula" (37-41) was the "first open break" between Rome and the Jews. After the First Jewish–Roman War

The First Jewish–Roman War (66–73 CE), sometimes called the Great Jewish Revolt ( he, המרד הגדול '), or The Jewish War, was the first of three major rebellions by the Jews against the Roman Empire, fought in Roman-controlled ...

(66-73), Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

were officially allowed to practice their religion as long as they paid the Jewish tax

The or (Latin for "Jewish tax") was a tax imposed on Jews in the Roman Empire after the destruction of Jerusalem and its Temple in AD 70. Revenues were directed to the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus in Rome.

The tax measure improved Ro ...

. There is debate among historians over whether the Roman government simply saw Christians as a sect of Judaism prior to Nerva's modification of the tax in 96. From then on, practicing Jews paid the tax while Christians did not, providing hard evidence of an official distinction. Part of the Roman disdain for Christianity, then, arose in large part from the sense that it was bad for society. In the 3rd century, the Neoplatonist

Neoplatonism is a strand of Platonic philosophy that emerged in the 3rd century AD against the background of Hellenistic philosophy and religion. The term does not encapsulate a set of ideas as much as a chain of thinkers. But there are some id ...

philosopher Porphyry wrote:

How can people not be in every way impious and atheistic who have apostatized from the customs of our ancestors through which every nation and city is sustained? ... What else are they than fighters against God?Once distinguished from Judaism, Christianity was no longer seen as simply a bizarre sect of an old and venerable religion; it was a ''

superstitio

The vocabulary of ancient Roman religion was highly specialized. Its study affords important information about the religion, traditions and beliefs of the ancient Romans. This legacy is conspicuous in European cultural history in its influence on ...

''. Superstition had for the Romans a much more powerful and dangerous connotation than it does for much of the Western world today: to them, this term meant a set of religious practices that were not only different, but corrosive to society, "disturbing a man's mind in such a way that he is really going insane" and causing him to lose humanitas (humanity). The persecution of "superstitious" sects was hardly unheard-of in Roman history: an unnamed foreign cult was persecuted during a drought in 428 BCE, some initiates of the Bacchic cult were executed when deemed out-of-hand in 186 BCE, and measures were taken against the Celtic Druids during the early Principate

The Principate is the name sometimes given to the first period of the Roman Empire from the beginning of the reign of Augustus in 27 BC to the end of the Crisis of the Third Century in AD 284, after which it evolved into the so-called Dominate.

...

.

Even so, the level of persecution experienced by any given community of Christians still depended upon how threatening the local official deemed this new ''superstitio'' to be. Christians' beliefs would not have endeared them to many government officials: they worshipped a convicted criminal, refused to swear by the emperor's genius, harshly criticized Rome in their holy books, and suspiciously conducted their rites in private. In the early third century one magistrate told Christians "I cannot bring myself so much as to listen to people who speak ill of the Roman way of religion."

Persecution by reign

Overview

Persecution of the early church occurred sporadically and in localized areas from the start. The first persecution of Christians organized by the Roman government was under the emperorNero

Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus ( ; born Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus; 15 December AD 37 – 9 June AD 68), was the fifth Roman emperor and final emperor of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, reigning from AD 54 unti ...

in 64 CE after the Great Fire of Rome

The Great Fire of Rome ( la, incendium magnum Romae) occurred in July AD 64. The fire began in the merchant shops around Rome's chariot stadium, Circus Maximus, on the night of 19 July. After six days, the fire was brought under control, but before ...

and took place entirely within the city of Rome. The Edict of Serdica

The Edict of Serdica, also called Edict of Toleration by Galerius, was issued in 311 in Serdica (now Sofia, Bulgaria) by Roman Emperor Galerius. It officially ended the Diocletianic Persecution of Christianity in the Eastern Roman Empire.

The E ...

, issued in 311 by the Roman emperor Galerius

Gaius Galerius Valerius Maximianus (; 258 – May 311) was Roman emperor from 305 to 311. During his reign he campaigned, aided by Diocletian, against the Sasanian Empire, sacking their capital Ctesiphon in 299. He also campaigned across th ...

, officially ended the Diocletianic persecution

The Diocletianic or Great Persecution was the last and most severe persecution of Christians in the Roman Empire. In 303, the emperors Diocletian, Maximian, Galerius, and Constantius issued a series of edicts rescinding Christians' legal rig ...

of Christianity in the East. With the publication in 313 CE of the Edict of Milan

The Edict of Milan ( la, Edictum Mediolanense; el, Διάταγμα τῶν Μεδιολάνων, ''Diatagma tōn Mediolanōn'') was the February 313 AD agreement to treat Christians benevolently within the Roman Empire. Frend, W. H. C. ( ...

, persecution of Christians by the Roman state ceased. The total number of Christians who lost their lives because of these persecutions is unknown. The early church historian Eusebius

Eusebius of Caesarea (; grc-gre, Εὐσέβιος ; 260/265 – 30 May 339), also known as Eusebius Pamphilus (from the grc-gre, Εὐσέβιος τοῦ Παμφίλου), was a Greek historian of Christianity, exegete, and Chris ...

, whose works are the only source for many of these events, speaks of "countless numbers" or "myriads" having perished. Walter Bauer

Walter Bauer (; 8 August 1877 – 17 November 1960) was a German theologian, lexicographer of New Testament Greek, and scholar of the development of Early Christianity.

Life

Bauer was born in Königsberg, East Prussia, and raised in Marburg, ...

criticized Eusebius for this, but Robert Grant says readers were used to this kind of exaggeration as it was common in Josephus and other historians of the time.

By the mid-2nd century, mobs were willing to throw stones at Christians, perhaps motivated by rival sects. The Persecution in Lyon

The persecution in Lyon in AD 177 was a legendary persecution of Christians in Lugdunum, Roman Gaul (present-day Lyon, France), during the reign of Marcus Aurelius (161–180). As there is no coeval account of this persecution the earliest sourc ...

(177 AD) was preceded by mob violence, including assaults, robberies and stonings. Lucian tells of an elaborate and successful hoax perpetrated by a "prophet" of Asclepius, using a tame snake, in Pontus and Paphlagonia. When rumor seemed about to expose his fraud, the witty essayist reports in his scathing essay

... he issued a promulgation designed to scare them, saying that Pontus was full of atheists and Christians who had the hardihood to utter the vilest abuse of him; these he bade them drive away with stones if they wanted to have the god gracious.

Tertullian

Tertullian (; la, Quintus Septimius Florens Tertullianus; 155 AD – 220 AD) was a prolific early Christian author from Carthage in the Roman province of Africa. He was the first Christian author to produce an extensive corpus of L ...

's ''Apologeticus

''Apologeticus'' ( la, Apologeticum or ''Apologeticus'') is a text attributed to Tertullian, consisting of apologetic and polemic. In this work Tertullian defends Christianity, demanding legal toleration and that Christians be treated as all other ...

'' of 197 was ostensibly written in defense of persecuted Christians and addressed to Roman governors.

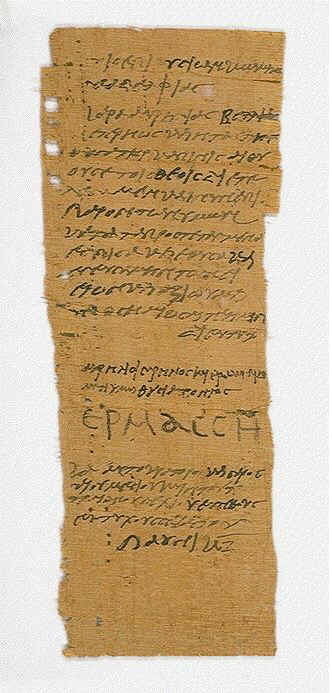

In 250 AD, the emperor Decius issued a decree requiring public sacrifice, a formality equivalent to a testimonial of allegiance to the emperor and the established order. There is no evidence that the decree was intended to target Christians but was intended as a form of loyalty oath. Decius authorized

In 250 AD, the emperor Decius issued a decree requiring public sacrifice, a formality equivalent to a testimonial of allegiance to the emperor and the established order. There is no evidence that the decree was intended to target Christians but was intended as a form of loyalty oath. Decius authorized roving commission A roving commission details the duties of a commissioned officer or other official whose responsibilities are neither geographically nor functionally limited.

Where an individual in an official position is given more freedom than would regularly be ...

s visiting the cities and villages to supervise the execution of the sacrifices and to deliver written certificates to all citizens who performed them. Christians were often given opportunities to avoid further punishment by publicly offering sacrifices or burning incense to Roman gods, and were accused by the Romans of impiety when they refused. Refusal was punished by arrest, imprisonment, torture, and executions. Christians fled to safe havens in the countryside and some purchased their certificates, called ''libelli.'' Several councils held at Carthage

Carthage was the capital city of Ancient Carthage, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the cla ...

debated the extent to which the community should accept these lapsed Christians.

The persecutions culminated with Diocletian and Galerius

Gaius Galerius Valerius Maximianus (; 258 – May 311) was Roman emperor from 305 to 311. During his reign he campaigned, aided by Diocletian, against the Sasanian Empire, sacking their capital Ctesiphon in 299. He also campaigned across th ...

at the end of the third and beginning of the 4th century. Their anti-Christian actions, considered the largest, were to be the last major Roman pagan action. The Edict of Serdica

The Edict of Serdica, also called Edict of Toleration by Galerius, was issued in 311 in Serdica (now Sofia, Bulgaria) by Roman Emperor Galerius. It officially ended the Diocletianic Persecution of Christianity in the Eastern Roman Empire.

The E ...

, also called Edict of Toleration by Galerius

The Edict of Serdica, also called Edict of Toleration by Galerius, was issued in 311 in Serdica (now Sofia, Bulgaria) by Roman Emperor Galerius. It officially ended the Diocletianic Persecution of Christianity in the Eastern Roman Empire.

The ...

, was issued in 311 in Serdica

Serdika or Serdica ( Bulgarian: ) is the historical Roman name of Sofia, now the capital of Bulgaria.

Currently, Serdika is the name of a district located in the city. It includes four neighbourhoods: "Fondovi zhilishta"; "Banishora", "Orlandov ...

(today Sofia

Sofia ( ; bg, София, Sofiya, ) is the capital and largest city of Bulgaria. It is situated in the Sofia Valley at the foot of the Vitosha mountain in the western parts of the country. The city is built west of the Iskar river, and h ...

, Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedo ...

) by the Roman emperor Galerius

Gaius Galerius Valerius Maximianus (; 258 – May 311) was Roman emperor from 305 to 311. During his reign he campaigned, aided by Diocletian, against the Sasanian Empire, sacking their capital Ctesiphon in 299. He also campaigned across th ...

, officially ending the Diocletianic persecution

The Diocletianic or Great Persecution was the last and most severe persecution of Christians in the Roman Empire. In 303, the emperors Diocletian, Maximian, Galerius, and Constantius issued a series of edicts rescinding Christians' legal rig ...

of Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global pop ...

in the East. Constantine the Great

Constantine I ( , ; la, Flavius Valerius Constantinus, ; ; 27 February 22 May 337), also known as Constantine the Great, was Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337, the first one to convert to Christianity. Born in Naissus, Dacia Mediterran ...

soon came into power and in 313 completely legalized Christianity. It was not until Theodosius I

Theodosius I ( grc-gre, Θεοδόσιος ; 11 January 347 – 17 January 395), also called Theodosius the Great, was Roman emperor from 379 to 395. During his reign, he succeeded in a crucial war against the Goths, as well as in two ...

in the latter 4th century, however, that Christianity would become the official religion of the Roman Empire.

Persecution from AD 49 to 250

In the

In the New Testament

The New Testament grc, Ἡ Καινὴ Διαθήκη, transl. ; la, Novum Testamentum. (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus, as well as events in first-century Chri ...

(Acts 18:2-3), a Jew named Aquila is introduced who, with his wife Priscilla

Priscilla is an English female given name adopted from Latin ''Prisca'', derived from ''priscus''. One suggestion is that it is intended to bestow long life on the bearer.

The name first appears in the New Testament of Christianity variously as ...

, had recently come from Italy because emperor Claudius "had ordered the Jews to leave Rome". Ed Richardson explains that expulsion occurred because disagreements in the Roman synagogues led to violence in the streets, and Claudius banished those responsible, but this also fell in the time period between 47 and 52 when Claudius engaged in a campaign to restore Roman rites and repress foreign cults. Suetonius records that Claudius expelled "the Jews" in 49, but Richardson says it was "mainly Christian missionaries and converts who were expelled", i.e. those Jewish Christians labelled under the name ''Chrestus''. "The garbled ''Chrestus'' is almost certainly evidence for the presence of Christians within the Jewish community of Rome".

Richardson points out that the term ''Christian'' "only became tangible in documents after the year 70" and that before that time, "believers in Christ were reckoned ethnically and religiously as belonging totally to the Jews". Suetonius and Tacitus used the terms "superstitio" and "impious rofanirites" in describing the reasons for these events, terms not applied to Jews, but commonly applied to believers in Christ. The Roman empire protected the Jews through multiple policies guaranteeing the "unimpeded observance of Jewish cult practices". Richardson strongly asserts that believers in Christ were the 'Jews' that Claudius was trying to be rid of by expulsion.

It is generally agreed that from Nero's reign until Decius

Gaius Messius Quintus Traianus Decius ( 201 ADJune 251 AD), sometimes translated as Trajan Decius or Decius, was the emperor of the Roman Empire from 249 to 251.

A distinguished politician during the reign of Philip the Arab, Decius was procl ...

's widespread measures in 250, Christian persecution was isolated and localized. Although it is often claimed that Christians were persecuted for their refusal to worship the emperor, general dislike for Christians likely arose from their refusal to worship the gods or take part in sacrifice, which was expected of those living in the Roman Empire. Although the Jews also refused to partake in these actions, they were tolerated because they followed their own Jewish ceremonial law, and their religion was legitimized by its ancestral nature.Frend 1965 On the other hand, Romans believed Christians, who were thought to take part in strange rituals and nocturnal rites, cultivated a dangerous and superstitious sect.

During this period, anti-Christian activities were accusatory and not inquisitive. Governors played a larger role in the actions than did Emperors, but Christians were not sought out by governors, and instead were accused and prosecuted through a process termed ''cognitio extra ordinem''. Evidence shows that trials and punishments varied greatly, and sentences ranged from acquittal to death.

Neronian persecution

According to Tacitus and later Christian tradition, Nero blamed Christians for the

According to Tacitus and later Christian tradition, Nero blamed Christians for the Great Fire of Rome

The Great Fire of Rome ( la, incendium magnum Romae) occurred in July AD 64. The fire began in the merchant shops around Rome's chariot stadium, Circus Maximus, on the night of 19 July. After six days, the fire was brought under control, but before ...

in 64, which destroyed portions of the city and economically devastated the Roman population. Anthony A. Barrett has written that "major archaeological endeavors have recently produced new evidence for the fire" but can't show who started it. In the ''Annals'' of Tacitus

Publius Cornelius Tacitus, known simply as Tacitus ( , ; – ), was a Roman historian and politician. Tacitus is widely regarded as one of the greatest Roman historians by modern scholars.

The surviving portions of his two major works—the ...

, it reads: This passage in Tacitus constitutes the only independent attestation that Nero blamed Christians for the Great Fire of Rome, and is generally believed to be authentic. Roughly contemporary with Tacitus, Suetonius in the 16th chapter of his biography of Nero wrote that "Punishment was inflicted on the Christians, a class of men given to a new and mischievous superstition", but does not specify the cause of the punishment. It is widely agreed on that the Number of the beast in the Book of Revelation

The Book of Revelation is the final book of the New Testament (and consequently the final book of the Christian Bible). Its title is derived from the first word of the Koine Greek text: , meaning "unveiling" or "revelation". The Book of ...

, adding up to 666, is derived from a gematria

Gematria (; he, גמטריא or gimatria , plural or , ''gimatriot'') is the practice of assigning a numerical value to a name, word or phrase according to an alphanumerical cipher. A single word can yield several values depending on the cipher ...

of the name of Nero Caesar, indicating that Nero was viewed as an exceptionally evil figure in the recent Christian past.

Recent scholarship by historians Candida Moss

Candida R. Moss (born 26 November 1978) is an English public intellectual, journalist, New Testament scholar and historian of Christianity, who is the Edward Cadbury Professor of Theology in the Department of Theology and Religion at the Univers ...

and Brent Shaw

Brent Donald Shaw (born May 27, 1947) is a Canadian historian and the current Andrew Fleming West Professor of Classics at Princeton University. His principal contributions center on the regional history of the Roman world with special emphasis ...

have disputed the accuracy of these accounts. Their arguments have persuaded some classicists, but the historicity of the Neronian persecution is upheld by the vast majority of historians.

Those who maintain that Nero targeted Christians debate whether Nero condemned Christians solely for the charge of organized arson, or for other general crimes associated with Christianity. Because Tertullian

Tertullian (; la, Quintus Septimius Florens Tertullianus; 155 AD – 220 AD) was a prolific early Christian author from Carthage in the Roman province of Africa. He was the first Christian author to produce an extensive corpus of L ...

mentions an ''institutum Neronianum'' in his apology "To the Nations", scholars debate the possibility of the creation of a law or decree against the Christians under Nero. French and Belgian scholars, and Marxists, have historically supported this view asserting that such a law would have been the application of common law rather than a formal decree. However, this view has been argued against that in context, the ''institutum Neronianum'' merely describes the anti-Christian activities; it does not provide a legal basis for them. Furthermore, no other writers besides Tertullian show knowledge of a law against Christians.

Several Christian sources report that Paul the Apostle and Saint Peter

) (Simeon, Simon)

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Bethsaida, Gaulanitis, Syria, Roman Empire

, death_date = Between AD 64–68

, death_place = probably Vatican Hill, Rome, Italia, Roman Empire

, parents = John (or Jonah; Jona)

, occupat ...

both died during the Neronian persecution; Origen

Origen of Alexandria, ''Ōrigénēs''; Origen's Greek name ''Ōrigénēs'' () probably means "child of Horus" (from , "Horus", and , "born"). ( 185 – 253), also known as Origen Adamantius, was an early Christian scholar, ascetic, and theo ...

and Dionysius of Corinth

Dionysius of Corinth, also known as Saint Dionysius, was the bishop of Corinth in about the year 171. His feast day is commemorated on April 8.

Date

The date is established by the fact that he wrote to Pope Soter. Eusebius in his ''Chronicle'' ...

, quoted by Eusebius

Eusebius of Caesarea (; grc-gre, Εὐσέβιος ; 260/265 – 30 May 339), also known as Eusebius Pamphilus (from the grc-gre, Εὐσέβιος τοῦ Παμφίλου), was a Greek historian of Christianity, exegete, and Chris ...

, further specify that Peter was crucified and that Paul was beheaded and that the two died in the same period. The Epistle of Clement to the Corinthians states (AD 95) that Peter and Paul were martyred, but doesn't specify where and when. As Moss and Shaw observe in their work on this subject, none of these sources refer to the Great Fire of Rome or identify it as an impetus for the arrest and execution of Peter and Paul.

Domitian

According to some historians, Jews and Christians were heavily persecuted toward the end ofDomitian

Domitian (; la, Domitianus; 24 October 51 – 18 September 96) was a Roman emperor who reigned from 81 to 96. The son of Vespasian and the younger brother of Titus, his two predecessors on the throne, he was the last member of the Fl ...

's reign (89-96). The Book of Revelation

The Book of Revelation is the final book of the New Testament (and consequently the final book of the Christian Bible). Its title is derived from the first word of the Koine Greek text: , meaning "unveiling" or "revelation". The Book of ...

, which mentions at least one instance of martyrdom (Rev 2:13; cf. 6:9), is thought by many scholars to have been written during Domitian's reign. Brown, Raymond E. ''An Introduction to the New Testament'', pp. 805–809. . Early church historian Eusebius

Eusebius of Caesarea (; grc-gre, Εὐσέβιος ; 260/265 – 30 May 339), also known as Eusebius Pamphilus (from the grc-gre, Εὐσέβιος τοῦ Παμφίλου), was a Greek historian of Christianity, exegete, and Chris ...

wrote that the social conflict described by Revelation reflects Domitian's organization of excessive and cruel banishments and executions of Christians, but these claims may be exaggerated or false. A nondescript mention of Domitian's tyranny can be found in Chapter 3 of Lactantius' ''On the Manner in Which the Persecutors Died''. According to Barnes, "Melito, Tertullian, and Bruttius stated that Domitian persecuted the Christians. Melito and Bruttius vouchsafe no details, Tertullian only that Domitian soon changed his mind and recalled those whom he had exiled".Barnes 1968. A minority of historians have maintained that there was little or no anti-Christian activity during Domitian's time. The lack of consensus by historians about the extent of persecution during the reign of Domitian derives from the fact that while accounts of persecution exist, these accounts are cursory or their reliability is debated.

Often, reference is made to the execution of Titus Flavius Clemens, a Roman consul

Consul (abbrev. ''cos.''; Latin plural ''consules'') was the title of one of the two chief magistrates of the Roman Republic, and subsequently also an important title under the Roman Empire. The title was used in other European city-states throu ...

and cousin of the Emperor, and the banishment of his wife, Flavia Domitilla, to the island of Pandateria. Eusebius

Eusebius of Caesarea (; grc-gre, Εὐσέβιος ; 260/265 – 30 May 339), also known as Eusebius Pamphilus (from the grc-gre, Εὐσέβιος τοῦ Παμφίλου), was a Greek historian of Christianity, exegete, and Chris ...

wrote that Flavia Domitilla was banished because she was a Christian. However, in Cassius Dio

Lucius Cassius Dio (), also known as Dio Cassius ( ), was a Roman historian and senator of maternal Greek origin. He published 80 volumes of the history on ancient Rome, beginning with the arrival of Aeneas in Italy. The volumes documented the ...

's account (67.14.1-2), he only reports that she, along with many others, was guilty of sympathy for Judaism. Suetonius does not mention the exile at all. According to Keresztes, it is more probable that they were converts to Judaism

Conversion to Judaism ( he, גיור, ''giyur'') is the process by which non-Jews adopt the Jewish religion and become members of the Jewish ethnoreligious community. It thus resembles both conversion to other religions and naturalization. " ...

who attempted to evade payment of the Fiscus Judaicus

The or (Latin for "Jewish tax") was a tax imposed on Jews in the Roman Empire after the destruction of Jerusalem and its Temple in AD 70. Revenues were directed to the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus in Rome.

The tax measure improved Ro ...

– the tax imposed on all persons who practiced Judaism (262-265). In any case, no stories of anti-Christian activities during Domitian's reign reference any sort of legal ordinances.

Trajan

EmperorTrajan

Trajan ( ; la, Caesar Nerva Traianus; 18 September 539/11 August 117) was Roman emperor from 98 to 117. Officially declared ''optimus princeps'' ("best ruler") by the senate, Trajan is remembered as a successful soldier-emperor who presi ...

corresponded with Pliny the Younger on the subject of how to deal with the Christians of Pontus

Pontus or Pontos may refer to:

* Short Latin name for the Pontus Euxinus, the Greek name for the Black Sea (aka the Euxine sea)

* Pontus (mythology), a sea god in Greek mythology

* Pontus (region), on the southern coast of the Black Sea, in modern ...

. The theologian Edward Burton wrote that this correspondence shows there were no laws condemning Christians at that time. There was an "abundance of precedent (common law) for suppressing foreign superstitions" but no general law which prescribed "the form of trial or the punishment; nor had there been any special enactment which made Christianity a crime". Even so, Pliny implies that putting Christians on trial was not rare, and while Christians in his district had committed no illegal acts like robbery or adultery, Pliny "put persons to death, though they were guilty of no crime, and without the authority of any law" and believed his emperor would accept his actions. Trajan did, and sent back a qualified approval. He told Pliny

Pliny may refer to:

People

* Pliny the Elder (23–79 CE), ancient Roman nobleman, scientist, historian, and author of ''Naturalis Historia'' (''Pliny's Natural History'')

* Pliny the Younger (died 113), ancient Roman statesman, orator, w ...

to continue to prosecute Christians, but not to accept anonymous denunciations in the interests of justice as well as of "the spirit of the age". Non-citizens who admitted to being Christians and refused to recant, however, were to be executed "for obstinacy". Citizens were sent to Rome for trial.

Barnes says this placed Christianity "in a totally different category from all other crimes. What is illegal is being a Christian".Barnes 1968. This became an official edict which Burton calls the 'first rescript' against Christianity, and which Sherwin-White says "might have had the ultimate effect of a general law". Despite this, medieval

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

Christian theologians considered Trajan to be a virtuous pagan

Virtuous pagan is a concept in Christian theology that addressed the fate of the unlearned—the issue of nonbelievers who were never evangelized and consequently during their lifetime had no opportunity to recognize Christ, but nevertheless ...

.

Hadrian

Emperor Hadrian (r. 117–138), in responding to a request for advice from a provincial governor about how to deal with Christians, granted Christians more leniency. Hadrian stated that merely being a Christian was not enough for action against them to be taken, they must also have committed some illegal act. In addition, "slanderous attacks" against Christians were not to be tolerated. This implied that anyone who brought an action against Christians but whose action failed, would themselves face punishment.Marcus Aurelius to Maximinus the Thracian

Sporadic bouts of anti-Christian activity occurred during the period from the reign of Marcus Aurelius to that of Maximinus. Governors continued to play a more important role than emperors in persecutions during this period.

In the first half of the third century, the relation of Imperial policy and ground-level actions against Christians remained much the same:

Sporadic bouts of anti-Christian activity occurred during the period from the reign of Marcus Aurelius to that of Maximinus. Governors continued to play a more important role than emperors in persecutions during this period.

In the first half of the third century, the relation of Imperial policy and ground-level actions against Christians remained much the same:

It was pressure from below, rather than imperial initiative, that gave rise to troubles, breaching the generally prevailing but nevertheless fragile, limits of Roman tolerance: the official attitude was passive until activated to confront particular cases and this activation normally was confined to the local and provincial level.Apostasy in the form of symbolic sacrifice continued to be enough to set a Christian free. It was standard practice to imprison a Christian after an initial trial, with pressure and an opportunity to recant.Cambridge Ancient History Vol. 12. The number and severity of persecutions in various locations of the empire seemingly increased during the reign of Marcus Aurelius,161-180. The martyrs of Madaura and the

Scillitan Martyrs

The Scillitan Martyrs were a company of twelve North African Christians who were executed for their beliefs on 17 July 180 AD. The martyrs take their name from Scilla (or Scillium), a town in Numidia. The '' Acts of the Scillitan Martyrs'' are c ...

were executed during his tenure. The extent to which Marcus Aurelius himself directed, encouraged, or was aware of these persecutions is unclear and much debated by historians.

One of the most notable instances of persecution during the reign of Aurelius occurred in 177 at Lugdunum

Lugdunum (also spelled Lugudunum, ; modern Lyon, France) was an important Roman city in Gaul, established on the current site of Lyon. The Roman city was founded in 43 BC by Lucius Munatius Plancus, but continued an existing Gallic settle ...

(present-day Lyons, France), where the Sanctuary of the Three Gauls

The Sanctuary of the Three Gauls ''(Tres Galliae)'' was the focal structure within an administrative and religious complex established by Rome in the very late 1st century BC at Lugdunum (the site of modern Lyon in France). Its institution serve ...

had been established by Augustus

Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Roman Pr ...

in the late 1st century BCE. The persecution in Lyons started as an unofficial movement to ostracize Christians from public spaces such as the market and the baths

The Baths is a beach area on the island of Virgin Gorda among the British Virgin Islands in the Caribbean.

Geography