Permanent Court Of International Justice on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Permanent Court of International Justice, often called the World Court, existed from 1922 to 1946. It was an

The Court faced increasing work as it went on, allaying the fears of those commentators who had believed the Court would become like the

The Court faced increasing work as it went on, allaying the fears of those commentators who had believed the Court would become like the

Permanent Court of International Justice (PCIJ) 1922–1946 Judgments, Advisory Opinions and Orders in PDF

Decisions of the World Court

Relevant to the UNCLOS (2010) an

Contents & Indexes

Searchable text of Judgments, Advisory Opinions and PCIJ documentation

{{DEFAULTSORT:Permanent Court Of International Justice Organisations based in The Hague Defunct courts Courts and tribunals established in 1922 Courts and tribunals disestablished in 1946 International courts and tribunals

international court

International courts are formed by treaties between nations or under the authority of an international organization such as the United Nations and include ''ad hoc'' tribunals and permanent institutions but exclude any courts arising purely under n ...

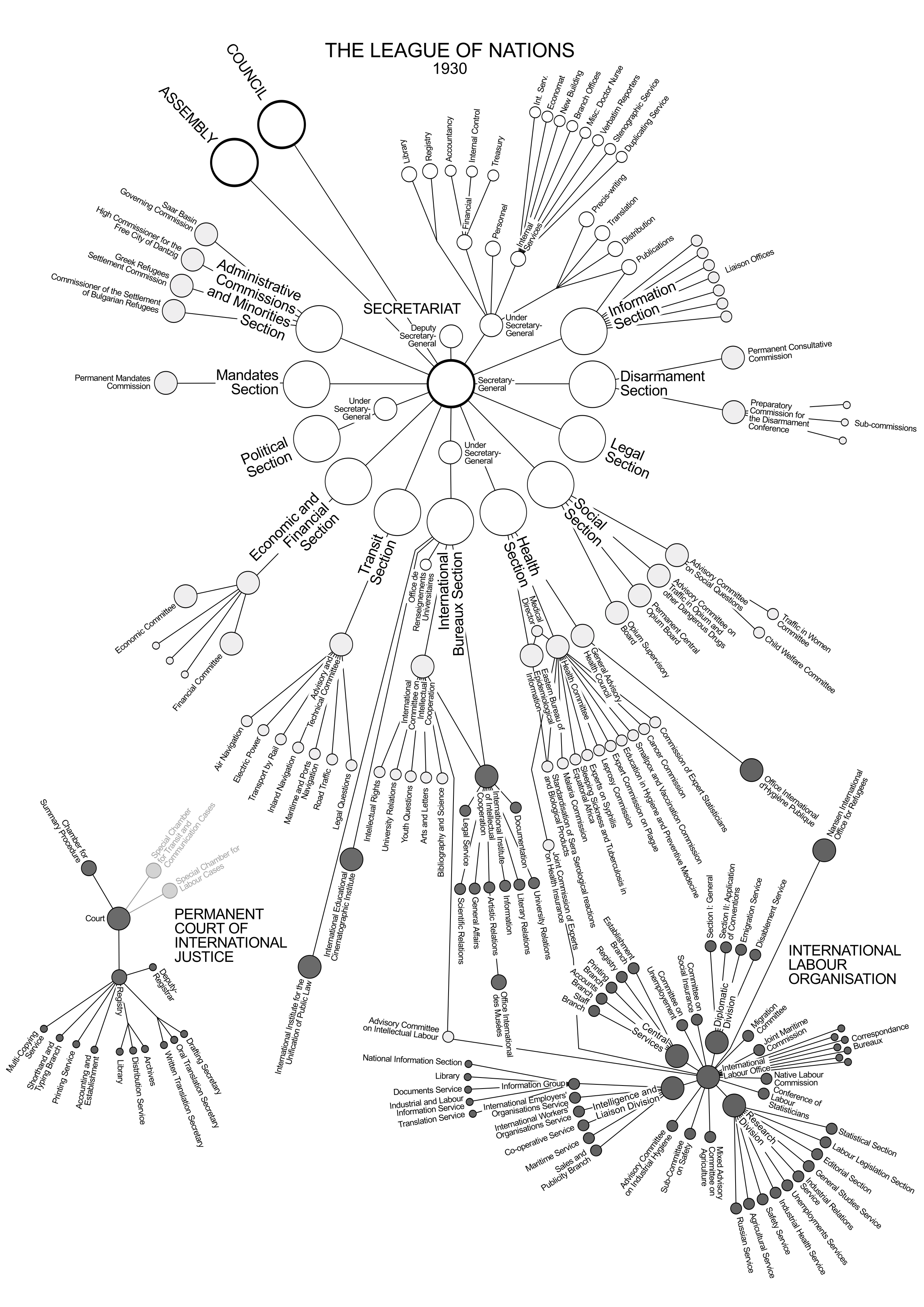

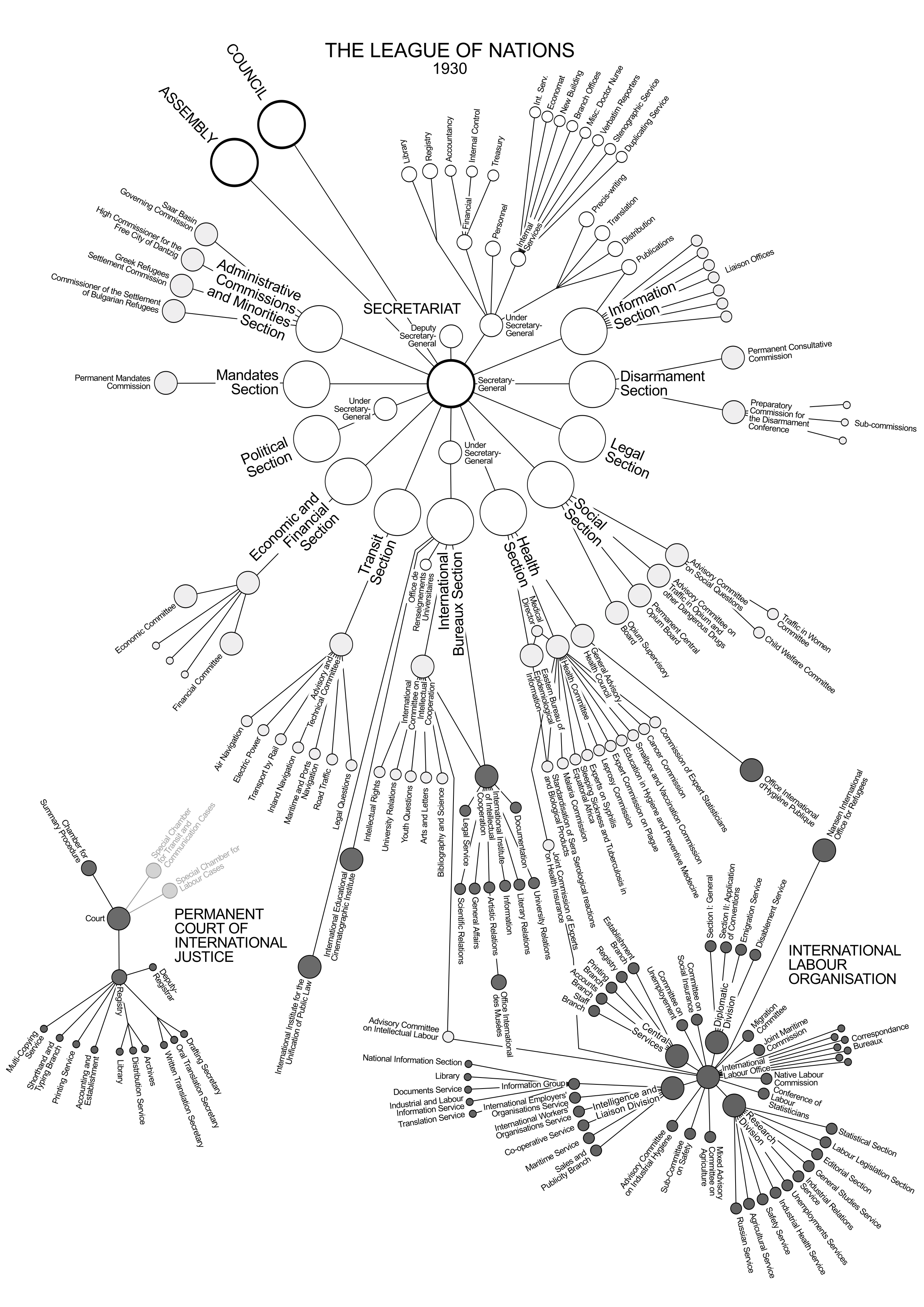

attached to the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide Intergovernmental organization, intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by ...

. Created in 1920 (although the idea of an international court was several centuries old), the Court was initially well-received from states and academics alike, with many cases submitted to it for its first decade of operation.

Between 1922 and 1940 the Court heard a total of 29 cases and delivered 27 separate advisory opinions. With the heightened international tension in the 1930s, the Court became less used. By a resolution from the League of Nations on 18 April 1946, both the Court and the League ceased to exist and were replaced by the International Court of Justice

The International Court of Justice (ICJ; french: Cour internationale de justice, links=no; ), sometimes known as the World Court, is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN). It settles disputes between states in accordanc ...

and the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmonizi ...

.

The Court's mandatory jurisdiction came from three sources: the Optional Clause of the League of Nations, general international conventions and special bipartite international treaties. Cases could also be submitted directly by states, but they were not bound to submit material unless it fell into those three categories. The Court could issue either judgments or advisory opinions. Judgments were directly binding but not advisory opinions. In practice, member states of the League of Nations followed advisory opinions anyway for fear of possibly undermining the moral and legal authority of the Court and the League.

History

Founding and early years

An international court had long been proposed; Pierre Dubois suggested it in 1305 andÉmeric Crucé

Émeric Crucé (1590–1648) was a French political writer, known for the ''Nouveau Cynée'' (1623), a pioneer work on international relations. He advocated for an international pacific body of representatives of many countries.

Life

Little spe ...

in 1623. An idea of an international court of justice arose in the political world at the First Hague Peace Conference in 1899, where it was declared that arbitration between states was the easiest solution to disputes, providing a temporary panel of judges to arbitrate in such cases, the Permanent Court of Arbitration. At the Second Hague Peace Conference in 1907, a draft convention for a permanent Court of Arbitral Justice was written although disputes and other pressing business at the Conference meant that such a body was never established, owing to difficulties agreeing on a procedure to select the judges. The outbreak of the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fig ...

, and, in particular, its conclusion made it clear to many academics that some kind of world court was needed, and it was widely expected that one would be established. Article 14 of the Covenant of the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide Intergovernmental organization, intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by ...

, created after the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June 1 ...

, allowed the League to investigate setting up an international court. In June 1920, an Advisory Committee of jurists appointed by the League of Nations finally established a working guideline for the appointment of judges, and the Committee was then authorised to draft a constitution for a permanent court not of arbitration but of justice. The Statute of the Permanent Court of International Justice was accepted in Geneva

Geneva ( ; french: Genève ) frp, Genèva ; german: link=no, Genf ; it, Ginevra ; rm, Genevra is the second-most populous city in Switzerland (after Zürich) and the most populous city of Romandy, the French-speaking part of Switzerland. Situ ...

on December 13, 1920.

The Court first sat on 30 January 1922, at the Peace Palace, The Hague

The Hague ( ; nl, Den Haag or ) is a list of cities in the Netherlands by province, city and municipalities of the Netherlands, municipality of the Netherlands, situated on the west coast facing the North Sea. The Hague is the country's ad ...

, covering preliminary business during the first session (such as establishing procedure and appointing officers) Nine judges sat, along with three deputies, since Antonio Sánchez de Bustamante y Sirven, Ruy Barbosa

Ruy Barbosa de Oliveira (5 November 1849 – 1 March 1923), also known as Rui Barbosa, was a Brazilian polymath, diplomat, writer, jurist, and politician. Born in Salvador, Bahia, and a distinguished and staunch defender of civil liberties and ...

and Wang Ch'ung-hui were unable to attend, the last being at the Washington Naval Conference

The Washington Naval Conference was a disarmament conference called by the United States and held in Washington, DC from November 12, 1921 to February 6, 1922. It was conducted outside the auspices of the League of Nations. It was attended by nine ...

. The Court elected Bernard Loder

Bernard Cornelis Johannes Loder (13 September 1849, Amsterdam – 4 November 1935, The Hague) was a Dutch jurist. He sat on the Supreme Court of the Netherlands from 1908 to 1921. He then sat as a judge of the Permanent Court of International J ...

as President and Max Huber as Vice-President; Huber was replaced by André Weiss

Charles André Weiss (September 30, 1858 in Mulhouse - August 31, 1928 in the Hague) was a French jurist. He was professor at the Universities of Dijon and Paris and served from 1922 until his death as judge of the Permanent Court of Internati ...

a month later. On 14 February the Court was officially opened, and rules of procedure were established on 24 March, when the court ended its first session. The court first sat to decide cases on 15 June. During its first year of business, the Court issued three advisory opinions, all related to the International Labour Organization

The International Labour Organization (ILO) is a United Nations agency whose mandate is to advance social and economic justice by setting international labour standards. Founded in October 1919 under the League of Nations, it is the first and o ...

created by the Treaty of Versailles.

The initial reaction to the Court was good, from politicians, practising lawyers and academics alike. Ernest Pollock

Ernest Murray Pollock, 1st Viscount Hanworth, KBE, PC (25 November 1861 – 22 October 1936), was a British Conservative politician, lawyer and judge. He served as Master of the Rolls from 1923 to 1935.

Background

Pollock was born in Wimbledon, ...

, the former Attorney General for England and Wales

His Majesty's Attorney General for England and Wales is one of the law officers of the Crown and the principal legal adviser to sovereign and Government in affairs pertaining to England and Wales. The attorney general maintains the Attorney G ...

said, "May we not as lawyers regard the establishment of an International Court of Justice as an advance in the science that we pursue?" John Henry Wigmore

John Henry Wigmore (1863–1943) was an American lawyer and legal scholar known for his expertise in the law of evidence and for his influential scholarship. Wigmore taught law at Keio University in Tokyo (1889–1892) before becoming the firs ...

said that the creation of the Court "should have given every lawyer a thrill of cosmic vibration", and James Brown Scott wrote that "the one dream of our ages has been realised in our time". Much praise was heaped upon the appointment of an American judge despite the fact that the United States had not become a signatory to the Court's protocol, and it was thought that it would soon do so.

Increasing work

The Court faced increasing work as it went on, allaying the fears of those commentators who had believed the Court would become like the

The Court faced increasing work as it went on, allaying the fears of those commentators who had believed the Court would become like the Supreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point ...

, which was not presented with a case for its first six terms. The Court was given nine cases during 1922, however, with judgments called "cases" and advisory opinions called "questions". Three cases were disposed of during the Court's first session, one during an extraordinary sitting between 8 January and 7 February 1923 (the Tunis-Morocco Nationality Question), four during the second ordinary sitting between 15 June 1923 and 15 September 1923 ( Eastern Carelia Question, S.S. "Wimbledon" case, German Settlers Question

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ger ...

, Acquisition of Polish Nationality Question) and one during a second extraordinary session from 12 November to 6 December 1923 ( Jaworznia Question). A replacement for Ruy Barbosa

Ruy Barbosa de Oliveira (5 November 1849 – 1 March 1923), also known as Rui Barbosa, was a Brazilian polymath, diplomat, writer, jurist, and politician. Born in Salvador, Bahia, and a distinguished and staunch defender of civil liberties and ...

(who had died on 1 March 1923 without hearing any cases) was also found, with the election of Epitácio Pessoa on 10 September 1923. The workload the following year was reduced, containing two judgments and one advisory opinion; the Mavrommatis Palestine Concessions Case Mavromatis or Mavrommatis ( gr, Μαυρομμάτης) is a Greek surname. Notable people with the surname include:

*Sotiris Mavromatis

*Theofanis Mavromatis (born 1997), Greek footballer

*Frangiskos Mavrommatis

*Nikolaos Mavrommatis, Greek sport ...

, the Interpretation of the Treaty of Neuilly Case (the first case of the Court's Chamber of Summary Procedure) and the Monastery of Saint-Naoum Question

A monastery is a building or complex of buildings comprising the domestic quarters and workplaces of monastics, monks or nuns, whether living in communities or alone (hermits). A monastery generally includes a place reserved for prayer which ...

. During the same year, a new President and Vice-President were elected, since they were mandated to serve for a term of three years. At the elections on 4 September 1924, André Weiss

Charles André Weiss (September 30, 1858 in Mulhouse - August 31, 1928 in the Hague) was a French jurist. He was professor at the Universities of Dijon and Paris and served from 1922 until his death as judge of the Permanent Court of Internati ...

was again elected Vice-President and Max Huber became the second President of the Court. Judicial pensions were created at the same time, with a judge being given 1/30th of his annual pay for every year he had served once he had both retired and turned 65.

1925 was an exceedingly busy year for the court, which sat for 210 days, with four extraordinary sessions as well as the ordinary session, producing 3 judgments and 4 advisory opinions. The first judgment was given in the Exchange of Greek and Turkish Populations Case, the second (by the Court of Summary Procedure) was on the interpretation of the Interpretation of the Treaty of Neuilly Case, and the third in the Mavrommatis Palestine Concessions Case Mavromatis or Mavrommatis ( gr, Μαυρομμάτης) is a Greek surname. Notable people with the surname include:

*Sotiris Mavromatis

*Theofanis Mavromatis (born 1997), Greek footballer

*Frangiskos Mavrommatis

*Nikolaos Mavrommatis, Greek sport ...

. The 4 advisory opinions issued by the Court were in the Polish Postal Service in Danzig Question, the Expulsion of the Ecumenical Patriarch Question

Expulsion or expelled may refer to:

General

* Deportation

* Ejection (sports)

* Eviction

* Exile

* Expeller pressing

* Expulsion (education)

* Expulsion from the United States Congress

* Extradition

* Forced migration

* Ostracism

* Persona non ...

, the Treaty of Lausanne Question

A treaty is a formal, legally binding written agreement between actors in international law. It is usually made by and between sovereign states, but can include international organizations, individuals, business entities, and other legal ...

and the German Interests in Polish Upper Silesia Question. 1926 saw reduced business, with only one ordinary session and one extraordinary session; it was, however, the first year that all 11 judges had been present to hear cases. The court heard two cases, providing one judgment and one advisory opinion; a second question on German Interests in Polish Upper Silesia, this time a judgment rather than an advisory opinion, and an advisory opinion on the International Labour Organization

The International Labour Organization (ILO) is a United Nations agency whose mandate is to advance social and economic justice by setting international labour standards. Founded in October 1919 under the League of Nations, it is the first and o ...

.

Despite the reduction of work in 1926, 1927 was another busy year, the Court sitting continuously from 15 June to 16 December, handing down 4 orders, 4 judgments and 1 advisory opinion. The judgments were in the Belgium-China Case, the Case Concerning the Factory at Chorzow, the Lotus Case and a continuation of the Mavrommatis Jerusalem Concessions Case. 3 of the advisory opinions were on the Competence of the European Commission on the Danube, and the 4th was on the Jurisdiction of Danzig Courts. The 4 orders were on the German Interests in Polish Upper Silesia. This year saw another set of elections; on 6 December, with Dionisio Anzilotti elected President and André Weiss

Charles André Weiss (September 30, 1858 in Mulhouse - August 31, 1928 in the Hague) was a French jurist. He was professor at the Universities of Dijon and Paris and served from 1922 until his death as judge of the Permanent Court of Internati ...

elected Vice-President. Weiss died the following year, and John Bassett Moore resigned; Max Huber was elected Vice-President on 12 September 1928 to succeed Weiss, while a second death ( Lord Finlay) left the Court increasingly understaffed. Replacements for Moore and Finlay were elected on 19 September 1929; Henri Fromageot

Henri Fromageot (10 September 1864 – 1949 ) was a French lawyer and judge. He studied at the University of Paris, University of Oxford and University of Leipzig

Leipzig University (german: Universität Leipzig), in Leipzig in Saxony, Germany, ...

and Cecil Hurst respectively.

After the second round of elections in September 1930, the Court was reorganised. On 16 January 1931 Mineichirō Adachi was appointed President, and Gustavo Guerrero

Gustavo Guerrero (born 22 October 1959) is a former professional tennis player from Argentina.

Career

Guerro competed in five French Opens. He lost to Rod Frawley in the first round of the 1981 French Open and then to another Australian, Paul Mc ...

Vice-President.

United States never joins

The United States never joined the World Court, primarily because enemies of the League of Nations in the Senate argued that the Court was too closely linked to the League of Nations. The leading opponent was SenatorWilliam Borah

William Edgar Borah (June 29, 1865 – January 19, 1940) was an outspoken Republican United States Senator, one of the best-known figures in Idaho's history. A progressive who served from 1907 until his death in 1940, Borah is often con ...

, Republican of Idaho. The United States finally recognised the Court's jurisdiction, following a long and drawn out process. President Warren G. Harding had first suggested US involvement in 1923, and on 9 December 1929, three court protocols were signed. The U.S. demanded a veto over cases involving the U.S. but other nations rejected the idea.

President Franklin Roosevelt did not risk his political capital and gave only passive support even though a two-thirds vote of approval was needed in the Senate. A barrage of telegrams flooded Congress, inspired by attacks made by Charles Coughlin and others. The treaty failed by seven votes on January 29, 1935.

The United States finally accepted the Court's jurisdiction on 28 December 1935, but the treaty was never ratified, and the U.S. never joined. Francis Boyle

Francis Anthony Boyle (born March 25, 1950) is a human rights lawyer and professor of international law at the University of Illinois College of Law. He has served as counsel for Bosnia and Herzegovina and has supported the rights of Palesti ...

attributes the failure to a strong isolationist element in the US Senate, arguing that the ineffectiveness shown by US nonparticipation in the Court and other international institutions could be linked to the start of the Second World War.

Growing international tension and dissolution of the court

1933 was a busy year for the court, which cleared its 20th case (and "greatest triumph"); the Eastern Greenland Case. This period was marked by growing international tension, however, with Japan and Germany announcing their withdrawal from theLeague of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide Intergovernmental organization, intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by ...

, to come into effect in 1935. That did not directly affect the Court, since the protocol accepting Court jurisdiction was separately ratified, but it influenced whether a nation would be willing to bring a case before it, as evidenced by Germany's withdrawal from two pending cases. 1934, the Court's 13th year, "has been in keeping with the traditions associated with that number", with few cases since the world's governments were more concerned with the growing international tension. The Court's business continued to be small in 1935, 1936, 1937, 1938, and 1939 although 1937 was marked by Monaco

Monaco (; ), officially the Principality of Monaco (french: Principauté de Monaco; Ligurian: ; oc, Principat de Mónegue), is a sovereign

''Sovereign'' is a title which can be applied to the highest leader in various categories. The word ...

's acceptance of the Court protocol. The Court's judicial output in 1940 consisted entirely of a set of orders, completed in a meeting between 19 and 26 February, caused by an international situation, which left the Court with "uncertain prospects for the future". Following the German invasion of the Netherlands, the Court was unable to meet although the Registrar and President were afforded full diplomatic immunity

Diplomatic immunity is a principle of international law by which certain foreign government officials are recognized as having legal immunity from the jurisdiction of another country.

. Informed that the situation would not be tolerated after diplomatic missions from other nations left The Hague

The Hague ( ; nl, Den Haag or ) is a list of cities in the Netherlands by province, city and municipalities of the Netherlands, municipality of the Netherlands, situated on the west coast facing the North Sea. The Hague is the country's ad ...

on 16 July, the President and Registrar left the Netherlands and moved to Switzerland, accompanied by their staff.

The Court was unable to meet between 1941 and 1944, but the framework remained intact, and it soon became apparent that the Court would be dissolved. In 1943, an international panel met to consider "the question of the Permanent Court of International Justice", meeting from 20 March to 10 February 1944. The panel agreed that the name and functioning of the Court should be preserved but for some future court rather than a continuation of the current one. Between 21 August and 7 October 1944, the Dumbarton Oaks Conference was held, which, among other things, created an international court attached to the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmonizi ...

, to succeed the Permanent Court of International Justice. As a result of these conferences and others, the judges of the Permanent Court of International Justice officially resigned in October 1945 and, via a resolution by the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide Intergovernmental organization, intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by ...

on 18 April 1946, the Court and the League both ceased to exist, being replaced by the International Court of Justice

The International Court of Justice (ICJ; french: Cour internationale de justice, links=no; ), sometimes known as the World Court, is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN). It settles disputes between states in accordanc ...

and the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmonizi ...

.

Organisation

Judges

The Court initially consisted of 11 judges and 4 deputy judges, recommended by member states of theLeague of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide Intergovernmental organization, intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by ...

to the Secretary General of the League of Nations, who would put them before the Council and Assembly for election. The Council and Assembly were to bear in mind that the elected panel of judges was to represent every major legal tradition in the League, along with "every major civilisation". Each member state was allowed to recommend 4 potential judges, with a maximum of 2 from its own nation. Judges were elected by a straight majority vote, held independently in the Council and Assembly. The judges served for a period of nine years, with their term limits all expiring at the same time, necessitating a completely new set of elections. The judges were independent and rid themselves of their nationality for the purposes of hearing cases, owing allegiance to no individual member state, but it was forbidden to have more than one judge from the same state. As a sign of their independence from national ties, judges were given full diplomatic immunity when engaged in Court business. The only requirements for judges were "high moral character" and "the qualifications required in their respective countries orthe highest judicial offices" or to be "jurisconsults of recognized competence in international law".

The first panel was elected on 14 September 1921, with the 4 deputies being elected on the 16th. On the first vote, Rafael Altamira y Crevea of Spain, Dionisio Anzilotti of Italy, Bernard Loder

Bernard Cornelis Johannes Loder (13 September 1849, Amsterdam – 4 November 1935, The Hague) was a Dutch jurist. He sat on the Supreme Court of the Netherlands from 1908 to 1921. He then sat as a judge of the Permanent Court of International J ...

of the Netherlands, Ruy Barbosa

Ruy Barbosa de Oliveira (5 November 1849 – 1 March 1923), also known as Rui Barbosa, was a Brazilian polymath, diplomat, writer, jurist, and politician. Born in Salvador, Bahia, and a distinguished and staunch defender of civil liberties and ...

of Brazil, Yorozu Oda

was a Japanese lawyer, academic and judge who served as one of the first Judges of the Permanent Court of International Justice. From 1899 to 1930 he served as a professor at the Tokyo Imperial University

, abbreviated as or UTokyo, is a pub ...

of Japan, André Weiss

Charles André Weiss (September 30, 1858 in Mulhouse - August 31, 1928 in the Hague) was a French jurist. He was professor at the Universities of Dijon and Paris and served from 1922 until his death as judge of the Permanent Court of Internati ...

of France, Antonio Sánchez de Bustamante y Sirven of Cuba and Lord Finlay of the United Kingdom were elected by a majority vote of both the Council and Assembly on the first ballot taken. The second ballot elected John Bassett Moore of the United States, and the sixth Didrik Nyholm

Diderik or Didrik is a Norwegian male given name. In North Germanic languages, the native form would be ''Tjodrik'', but ''Diderik'' and ''Didrik'' have been loaned from Low German and are now a common name in Norway. It may also be a variant of ...

of Denmark and Max Huber of Switzerland. As the deputy judges, Wang Ch'ung-hui of China, Demetre Negulesco

Demetre is an Old Greek male name.

Examples

*Demetre Chiparus

*Demetre II of Georgia

*Demetre I of Georgia

*Demetre Kantemir

*Demetre of Guria

*Demetres Koutsavlakis

*Demetrescu-Tradem

External links

Etymology of DemetreEtymology of Demet ...

of Romania and Michaelo Yovanovich of Yugoslavia were elected. The Assembly and Council disagreed on the fourth deputy judge, but Frederik Beichmann

Frederik Valdemar Nikolai Beichmann (3 January 1859 – 29 December 1937) was a Norwegian judge and civil servant

He was born in Christiania to military officer Johan Diderik Schlømer Beichmann and Alette Faye. He was married to Edle Hartma ...

of Norway was eventually appointed. Deputy judges were only substitutes for absent judges and were not afforded a vote in altering court procedure or contributing at other times. As such, they were allowed to act as counsel in international cases where they were not sitting as judges.

In 1930, the number of judges was increased to 15, and a new set of elections were held. The election was held on 25 September 1930, with 14 candidates receiving a majority on the first ballot and a 15th, Francisco José Urrutia

Francisco is the Spanish and Portuguese form of the masculine given name ''Franciscus''.

Nicknames

In Spanish, people with the name Francisco are sometimes nicknamed "Paco (name), Paco". Francis of Assisi, San Francisco de Asís was known as '' ...

, receiving a majority on the second. The full court was Urrutia, Mineichiro Adachi, Rafael Altamira y Crevea, Dionisio Anzilotti, Bustamante, Willem van Eysinga, Henri Fromageot

Henri Fromageot (10 September 1864 – 1949 ) was a French lawyer and judge. He studied at the University of Paris, University of Oxford and University of Leipzig

Leipzig University (german: Universität Leipzig), in Leipzig in Saxony, Germany, ...

, José Gustavo Guerrero, Cecil Hurst, Edouard Rolin-Jaequemyns, Frank B. Kellogg, Negulesco, Michał Jan Rostworowski, Walther Schücking

Walther Adrian Schücking (6 January 1875, Münster, Westphalia – 25 August 1935) was a German liberal politician, professor of public international law and the first German judge at the Permanent Court of International Justice in The Hagu ...

and Wang Ch'ung-hui.

Judges were paid 15,000 Dutch florins a year, with daily expenses of 50 florins to pay for living expenses, and an additional 45,000 florins for the President, who was required to live at The Hague. Travelling expenses were also provided, and a "duty allowance" of 100 florins was provided when the court was sitting, with 150 for the Vice-President. This duty allowance was limited to 20,000 florins a year for the judges and 30,000 florins for the Vice-President; as such, it provided for 200 days of court hearings, with no allowance provided if the court sat for longer. The deputy judges received no salary but, when called up for service, were provided with travel expenses, 50 florins a day for living expenses and 150 florins a day as a duty allowance.

Procedure

Under the Covenant of the League of Nations, all League members agreed that if there was a dispute between states they "recognize to be suitable for submission to arbitration and which cannot be satisfactorily settled by diplomacy", the matter would be submitted to the Court for arbitration, with suitable disputes being over the interpretation of an international treaty, a question on international law, the validity of facts, which, if true, would breach international obligations and the nature of any reparations to be made for breaching international obligations. The original Statutes of the Court provided that all 11 judges were required to sit in every case. There were three exceptions: when reviewing Labour Clauses from a peace treaty such as theTreaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June 1 ...

(which was done by a special chamber of 5 judges, appointed every 3 years), when reviewing cases on communications or transport arising from a peace treaty (which used a similar procedure) and when hearing summary procedure cases, which were reviewed by a panel of 3 judges.

To prevent the appearance of any bias in the court's makeup, if there was a judge belonging to one member state on the panel and the other member state was not "represented", they had the ability to select an ''ad hoc

Ad hoc is a Latin phrase meaning literally 'to this'. In English, it typically signifies a solution for a specific purpose, problem, or task rather than a generalized solution adaptable to collateral instances. (Compare with '' a priori''.)

C ...

'' judge of their own nationality to hear the case. In a full court hearing, that increased the number to 12; in one of the 5-man chambers, the new judge took the place of one of the original 5. That did not apply to summary procedure cases. The ''ad hoc'' judge, selected by the member state, was expected to fulfil all the requirements of a normal judge; the President of the Court had ultimate discretion over whether to authorise him to sit. The Court was mandated to open on 15 June each year and continue until all cases were finished, with extraordinary sessions if required; by 1927, there were more extraordinary sessions than ordinary ones. The Court's business being conducted in English and French as official languages, and hearings were public unless it was otherwise specified.

After receiving files in a case calculated to lead to a judgment

Judgement (or US spelling judgment) is also known as '' adjudication'', which means the evaluation of evidence to make a decision. Judgement is also the ability to make considered decisions. The term has at least five distinct uses. Aristotle s ...

, the judges would exchange their views informally on the salient legal points of the case, and a time limit for producing a judgment would then be set. Then, each judge would write an anonymous summary containing his opinion; the opinions would be circulated among the Court for 2 or 3 days before the President drafted a judgment containing a summary of those submitted by individual judges. The Court would then agree on the decision that they wished to reach, along with the main points of argument they wished to use. Once this was done, a Committee of 4, including the President, the Registrar and two judges elected by secret ballot, drafted a final judgment, which was then voted on by the entire Court. Once a final judgment was set, it was given to the public and the press. Every judgment contained the reasons behind the decision and the judges assenting; dissenting judges were allowed to deliver their own judgment, with all judgments read in open court before the agents of the parties to the dispute. Judgments could not be revised except on the discovery of some fact unknown when the Court sat but not if the fact was known but not discussed because of negligence.

The Court also issued "advisory opinions

An advisory opinion is an opinion issued by a court or a commission like an election commission that does not have the effect of adjudicating a specific legal case, but merely advises on the constitutionality or interpretation of a law. Some co ...

", which arose from Article 14 of the Covenant creating the Court, which provided, "The Court may also give an advisory opinion upon any dispute referred to it by the Council or Assembly". Goodrich interprets that as indicating that the drafters intended a purely advisory capacity for the Court, not a binding one. Manley Ottmer Hudson

Manley Ottmer Hudson (May 19, 1886 – April 13, 1960) was a U.S. lawyer, specializing in public international law. He was a judge at the Permanent Court of International Justice, a member of the International Law Commission, and a mediato ...

(who sat as a judge) said that an advisory opinion "was what it purported to be. It is advisory. It is not in any sense a judgement... hence it is not in any way binding on any state", but Charles De Visscher argued that in certain situations, an advisory opinion could be binding on the League of Nations Council and, under certain circumstances, some states; M. Politis agreed, saying that the Court's advisory opinions were equivalent to a binding judgment. In 1927, the Court appointed a committee to look at this issue, and it reported that "where there are in fact contending parties, the difference between contentious cases and advisory cases is only nominal... so the view that advisory opinions are not binding is more theoretical than real". In practice, advisory opinions were usually followed, mostly due to the fear that if this "revolutionary" international court's decisions were not followed, it would undermine its authority. The court retained the discretion to avoid giving an advisory opinion, which it used on occasion.

Registrar and Registry

Other than the judges, the Court also included a Registrar and his Secretariat, the Registry. When the Court met for its initial session, opened on 30 January 1922 to allow for the establishment of procedure and the appointment of Court officials, the Secretary-General of theLeague of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide Intergovernmental organization, intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by ...

passed an emergency resolution through the Assembly, which designated an official of the League and his staff as the Registrar and Registry respectively, with the first Registrar being Åke Hammarskjöld

Åke Wilhelm Hjalmar Hammarskjöld (April 10, 1893 – July 7, 1937) was a Swedish lawyer and diplomat. He was the first Registrar of the Permanent Court of International Justice, serving from 1922 to 1936, when he was elected to the position of ...

. The Registrar, required to reside within The Hague

The Hague ( ; nl, Den Haag or ) is a list of cities in the Netherlands by province, city and municipalities of the Netherlands, municipality of the Netherlands, situated on the west coast facing the North Sea. The Hague is the country's ad ...

, was initially tasked with drawing up a plan to create an efficient Secretariat, using the smallest number of staff possible and costing as little as possible. As a result, he decided to have each member of the Secretariat as the head of a particular Department, so the numbers of actual employees could be increased or decreased as necessary without impacting on the actual Registry. In 1927, the post of Deputy-Registrar was created, tasked with dealing with legal research for the Court and answering all diplomatic correspondence received by the Registry.

The first Deputy-Registrar was Paul Ruegger; after his resignation on 17 August 1928, Julio Lopez Olivan Julio is the Spanish equivalent of the month July and may refer to:

* Julio (given name)

* Julio (surname)

* Júlio de Castilhos, a municipality of the western part of the state of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil

* ''Julio'' (album), a 1983 compilation a ...

was selected to succeed him. Olivan resigned in 1931 to take over from Hammarskjöld as Registrar, and was replaced by M. L. J. H. Jorstad.

The three principal officers of the Registry, after the Registrar and Deputy-Registrar, were the three Editing Secretaries. The first Editing Secretary, known as the Drafting Secretary, was tasked with drafting the Court's publications (including the Confidential Bulletin, a document exclusively received by judges of the court) and Sections D and E of the official journal, comprising the legislative clauses conferring jurisdiction on the Court and the Court's Annual Report. The second Editing Secretary, known as the Oral Secretary, was mainly responsible for the oral interpretation and translation of the Court's discussions. For public hearings, he was assisted by interpreters, but for private meetings, only he, the Registrar and the Deputy-Registrar were admitted. As a result of this duty, the Oral Secretary was also tasked with writing Section C of the official journal, which comprised the oral interpretations of Court minutes, along with cases and questions put before the court. The third Secretary, known as the Written Secretary, was tasked with the written translations of the Court's business, which were "both numerous and voluminous". He was assisted in this by the other Secretaries and by translators for languages not his own; all Secretaries were expected to speak English and French fluently and to have working knowledge of German and Spanish.

The Registry was split into several Departments; the Archives, the Accounting and Establishment, the Printing Service and the Copying Department. The Archives included a distribution service for the Court's documents and the legal texts used by the Court itself and was described as one of the most difficult departments to organise. The Accounting and Establishment Department dealt with the requests for and allocation of the Court's yearly budget, which was drawn up by the Registrar, approved by the Court and submitted to the League of Nations. The Printing Department, run from a single printing plant in Leiden

Leiden (; in English and archaic Dutch also Leyden) is a city and municipality in the province of South Holland, Netherlands. The municipality of Leiden has a population of 119,713, but the city forms one densely connected agglomeration wit ...

, was created to allow the circulation of the Court's publishings. The Copying Department comprised shorthand, typing and copying services, and included secretaries for the Registrar and judges, emergency reporters capable of taking notes down verbatim and copyists; the smallest of the departments, it comprised between 12 and 40 staff depending on the business of the Court.

Cases

Cases

* S.S. ''Wimbledon'' case 1923 * Mavrommatis Palestine Concessions 1924 *Mavrommatis Jerusalem Concessions Mavromatis or Mavrommatis ( gr, Μαυρομμάτης) is a Greek surname. Notable people with the surname include:

* Sotiris Mavromatis

* Theofanis Mavromatis (born 1997), Greek footballer

* Frangiskos Mavrommatis

* Nikolaos Mavrommatis, Greek ...

1925

* Certain German Interests in Polish Upper Silesia 1926

* Factory at Chorzów case 1927

* The ''Lotus'' case 1927

* Rights of Minorities in Upper Silesia (Minority Schools) 1928

* Free Zones of Upper Savoy and the District of Gex (France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan ar ...

v Switzerland)

* Brazilian Loans case 1929

* Serbian Loans case 1929

* Territorial Jurisdiction of the International Commission of the Oder River Case 1929

* Legal Status of the South-Eastern Territory of Greenland 1932

* Lighthouses case between France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan ar ...

and Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders wit ...

1934

* Borchgrave case

* Oscar Chinn case The Oscar Chinn Case (Britain v. Belgium). 934 P.C.I.J. (Ser. A/B) No. 63

was a case of the Permanent Court of International Justice.

The Belgian government granted significant subsidies to a Belgian company, UNATRA, that offered transportation ser ...

1934

* Minority Schools in Albania case 1935

* Losinger case 1936

* Diversion of Water from the Meuse Case {{Infobox court case

, name = Case Relating to the Diversion of the Water From the Meuse

, court = Permanent Court of International Justice

, image =

, imagesize =

, imagelink =

, imageal ...

1937

* Phosphates in Morocco case 1938

* Panevezys-Saldutiskis Railway case 1939

* Electricity Company of Sofia and Bulgaria case 1939

* Société Commerciale de Belgique 1939

* Interpretation of the Treaty of Neuilly Case 1924

Advisories

* Status of Eastern Carelia Question 1923 * Nationality Decrees Issued inTunis

''Tounsi'' french: Tunisois

, population_note =

, population_urban =

, population_metro = 2658816

, population_density_km2 =

, timezone1 = CET

, utc_offset1 ...

and Morocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria ...

1923

* German Settlers in Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, , is a country in Central Europe. Poland is divided into Voivodeships of Poland, sixteen voivodeships and is the fifth most populous member state of the European Union (EU), with over 38 mill ...

1923

* Jaworzina 1923

* Monastery of Saint-Naoum Question

A monastery is a building or complex of buildings comprising the domestic quarters and workplaces of monastics, monks or nuns, whether living in communities or alone (hermits). A monastery generally includes a place reserved for prayer which ...

1924

* Exchange of Greek and Turkish Populations Question 1925

* Polish Postal Service in Danzig Question 1925

* the Expulsion of the Ecumenical Patriarch Question

* the Treaty of Lausanne Question

* Competence of the International Labour Organisation to Regulate Incidentally the Personal Work of the Employer 1926

* Jurisdiction of the European Commission of the Danube

* Jurisdiction of the Courts of Danzig Case

Jurisdiction (from Latin 'law' + 'declaration') is the legal term for the legal authority granted to a legal entity to enact justice. In federations like the United States, areas of jurisdiction apply to local, state, and federal levels.

Jur ...

1928

* Greco-Bulgarian "Communities" Question 1930

* Interpretation of the Greco-Turkish Agreement 1928

* Access to German Minority Schools in Upper Silesia 1931

* Customs Regime between Germany and Austria Question

Customs is an authority or agency in a country responsible for collecting tariffs and for controlling the flow of goods, including animals, transports, personal effects, and hazardous items, into and out of a country. Traditionally, customs ...

1931

* Railway Traffic between Lithuania and Poland Question 1931

* Interpretation of the Greco-Bulgarian Agreement 1932

* Free Zones of Upper Savoy and the District of Gex 1932

* Interpretation of the Convention of 1919 concerning Employment of Women during the Night 1932

Jurisdiction

The Court's jurisdiction was largely optional, but there were some situations in which they had "compulsory jurisdiction", and states were required to refer cases to them. That came from three sources: the Optional Clause of the League of Nations, general international conventions and "specialbipartite

Bipartite may refer to:

* 2 (number)

* Bipartite (theology), a philosophical term describing the human duality of body and soul

* Bipartite graph, in mathematics, a graph in which the vertices are partitioned into two sets and every edge has an en ...

international treaties". The Optional Clause was a clause attached to the protocol establishing the court and required all signatories to refer certain classes of dispute to the court, with compulsory judgments resulting. There were approximately 30 international conventions under which the Court had similar jurisdiction, including the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June 1 ...

, the Air Navigation Convention

The atmosphere of Earth is the layer of gases, known collectively as air, retained by Earth's gravity that surrounds the planet and forms its planetary atmosphere. The atmosphere of Earth protects life on Earth by creating pressure allowing ...

, the Treaty of St. Germain and all mandates signed by the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide Intergovernmental organization, intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by ...

. It was also foreseen that there would be clauses inserted in bipartite international treaties, which would allow the referral of disputes to the Court; that occurred, with such provisions found in treaties between Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

and Austria, and between Czechoslovakia and Poland.

Throughout its existence, the Court widened its jurisdiction as much as possible. Strictly speaking, the Court's jurisdiction was only for disputes between states, but it regularly accepted disputes that were between a state and an individual if a second state brought the individual's case to the Court. It argued that the second state assertsled its rights, and the cases therefore became one between two states.

The proviso that the Court was for disputes that could not "be satisfactorily settled by diplomacy" never made it require evidence that diplomatic discussions had been attempted before bringing the case. In the Loan Cases, it asserted jurisdiction despite the fact that there was no alleged breach of international law, and it could not be shown that there was any international element to the claim. The Court justified itself by saying that the Covenant of the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide Intergovernmental organization, intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by ...

allowed it to have jurisdiction in cases over "the existence of any fact which, if established, would constitute a breach of international obligations" and argued that since the fact "may be of any kind", it had jurisdiction if the dispute is one of municipal law. It had been long established that municipal law may be considered as a side point to a dispute over international law, but the Loan Cases discussed municipal law without the application of any international points.Jacoby (1936) p.237

See also

* Commissions of the Danube River * League of Nations archives * Permanent Court of International Justice cases * Total Digital Access to the League of Nations Archives Project (LONTAD)References

Bibliography

* Accinelli, Robert D. "The Roosevelt Administration and the World Court Defeat, 1935." ''Historian'' 40.3 (1978): 463–478. * * * Dunne, Michael. "Isolationism of a Kind: Two Generations of World Court Historiography in the United States." ''Journal of American Studies'' 21#3 (1987): 327–351. * Dunne, Michael. '' The United States and the World Court, 1920–1935'' (1988). * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * Kahn, Gilbert N. "Presidential Passivity on a Nonsalient Issue: President Franklin D. Roosevelt and the 1935 World Court Fight." ''Diplomatic History'' 4.2 (1980): 137–160. * * * * *External links

Permanent Court of International Justice (PCIJ) 1922–1946 Judgments, Advisory Opinions and Orders in PDF

Decisions of the World Court

Relevant to the UNCLOS (2010) an

Contents & Indexes

Searchable text of Judgments, Advisory Opinions and PCIJ documentation

{{DEFAULTSORT:Permanent Court Of International Justice Organisations based in The Hague Defunct courts Courts and tribunals established in 1922 Courts and tribunals disestablished in 1946 International courts and tribunals