Permafrost (novella) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Permafrost () is

Chapter 9: Ocean, Cryosphere and Sea Level Change

I

Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

[Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S.L. Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, M.I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J.B.R. Matthews, T.K. Maycock, T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, R. Yu, and B. Zhou (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, pp. 1211–1362. In addition to its climate impact, permafrost thaw brings additional risks. Formerly frozen ground often contains enough ice that when it thaws, hydraulic saturation is suddenly exceeded, so the ground shifts substantially and may even collapse outright. Many buildings and other

In addition to its climate impact, permafrost thaw brings additional risks. Formerly frozen ground often contains enough ice that when it thaws, hydraulic saturation is suddenly exceeded, so the ground shifts substantially and may even collapse outright. Many buildings and other

Permafrost is

Permafrost is

When the ice content of a permafrost exceeds 250 percent (ice to dry soil by mass) it is classified as ''massive'' ice. Massive ice bodies can range in composition, in every conceivable gradation from icy mud to pure ice. Massive icy beds have a minimum thickness of at least 2 m and a short diameter of at least 10 m.

First recorded North American observations were by European scientists at Canning River, Alaska in 1919.

Russian literature provides an earlier date of 1735 and 1739 during the Great North Expedition by P. Lassinius and Kh. P. Laptev, respectively.

Two categories of massive ground ice are ''buried surface ice'' and ''intrasedimental ice''

(also called ''constitutional ice'').

Buried surface ice may derive from snow, frozen lake or sea ice,

When the ice content of a permafrost exceeds 250 percent (ice to dry soil by mass) it is classified as ''massive'' ice. Massive ice bodies can range in composition, in every conceivable gradation from icy mud to pure ice. Massive icy beds have a minimum thickness of at least 2 m and a short diameter of at least 10 m.

First recorded North American observations were by European scientists at Canning River, Alaska in 1919.

Russian literature provides an earlier date of 1735 and 1739 during the Great North Expedition by P. Lassinius and Kh. P. Laptev, respectively.

Two categories of massive ground ice are ''buried surface ice'' and ''intrasedimental ice''

(also called ''constitutional ice'').

Buried surface ice may derive from snow, frozen lake or sea ice,

As the water drains or evaporates, soil structure weakens and sometimes becomes viscous until it regains strength with decreasing moisture content. One visible sign of permafrost degradation is the random displacement of trees from their vertical orientation in permafrost areas. Global warming has been increasing permafrost slope disturbances and sediment supplies to fluvial systems, resulting in exceptional increases in river sediment. On the other hands, disturbance of formerly hard soil increases drainage of water reservoirs in northern

As the water drains or evaporates, soil structure weakens and sometimes becomes viscous until it regains strength with decreasing moisture content. One visible sign of permafrost degradation is the random displacement of trees from their vertical orientation in permafrost areas. Global warming has been increasing permafrost slope disturbances and sediment supplies to fluvial systems, resulting in exceptional increases in river sediment. On the other hands, disturbance of formerly hard soil increases drainage of water reservoirs in northern  Permafrost thaw can also result in the formation of frozen debris lobes (FDLs), which are defined as "slow-moving landslides composed of soil, rocks, trees, and ice". This is a notable issue in the

Permafrost thaw can also result in the formation of frozen debris lobes (FDLs), which are defined as "slow-moving landslides composed of soil, rocks, trees, and ice". This is a notable issue in the

As of 2021, there are 1162 settlements located directly atop the Arctic permafrost, which host an estimated 5 million people. By 2050, permafrost layer below 42% of these settlements is expected to thaw, affecting all their inhabitants (currently 3.3 million people). Consequently, a wide range of

As of 2021, there are 1162 settlements located directly atop the Arctic permafrost, which host an estimated 5 million people. By 2050, permafrost layer below 42% of these settlements is expected to thaw, affecting all their inhabitants (currently 3.3 million people). Consequently, a wide range of  Outside of the Arctic,

Outside of the Arctic,

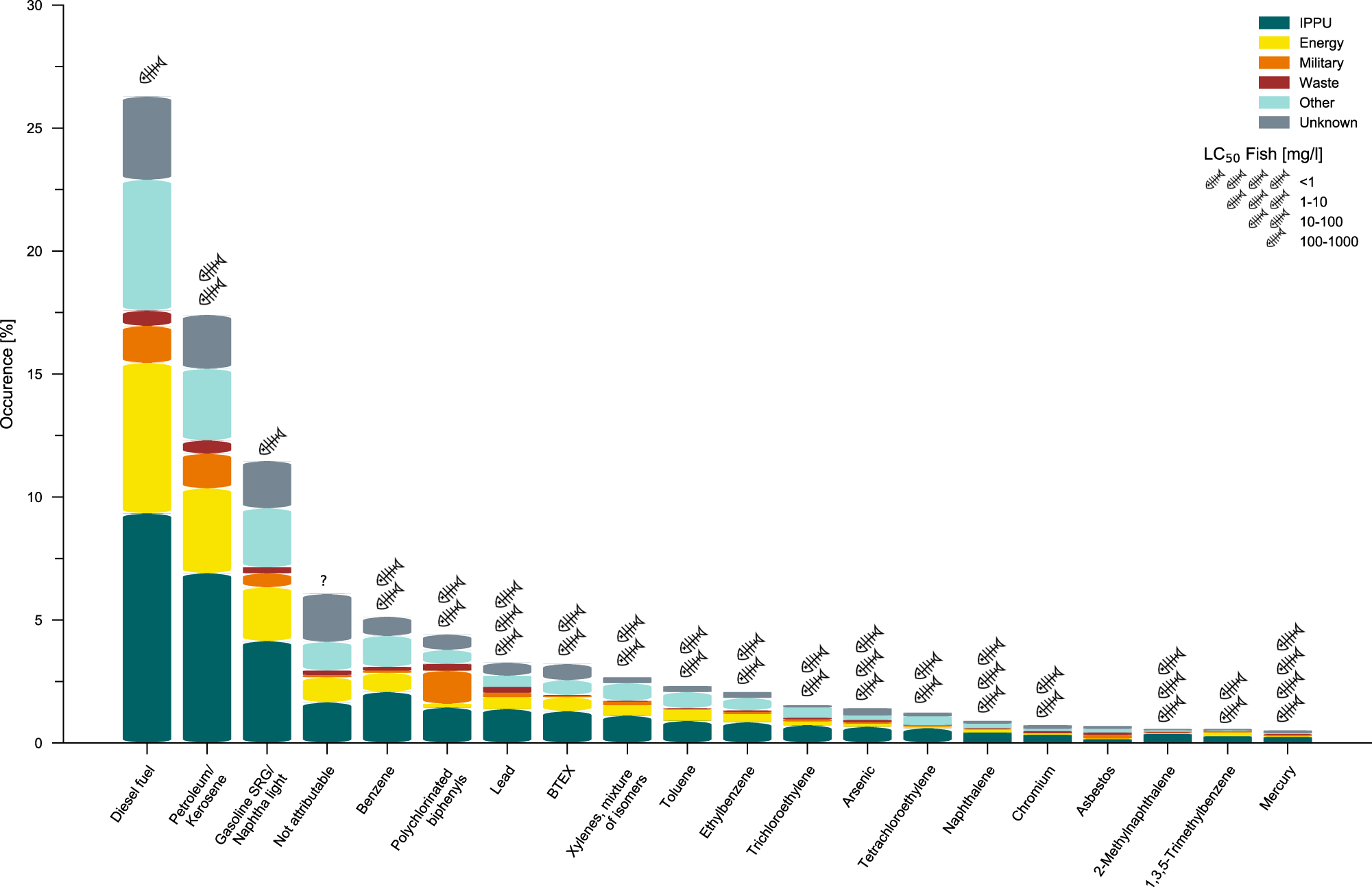

For much of the 20th century, it was believed that permafrost would "indefinitely" preserve anything buried there, and this made deep permafrost areas popular locations for hazardous waste disposal. In places like Canada's

For much of the 20th century, it was believed that permafrost would "indefinitely" preserve anything buried there, and this made deep permafrost areas popular locations for hazardous waste disposal. In places like Canada's  A notable example of pollution risks associated with permafrost was the

A notable example of pollution risks associated with permafrost was the

In the northern circumpolar region, permafrost contains 1700 billion tons of organic material equaling almost half of all organic material in all soils. This pool was built up over thousands of years and is only slowly degraded under the cold conditions in the Arctic. The amount of carbon sequestered in permafrost is four times the carbon that has been released to the atmosphere due to human activities in modern time. One manifestation of this is yedoma, which is an organic-rich (about 2% carbon by mass)

In the northern circumpolar region, permafrost contains 1700 billion tons of organic material equaling almost half of all organic material in all soils. This pool was built up over thousands of years and is only slowly degraded under the cold conditions in the Arctic. The amount of carbon sequestered in permafrost is four times the carbon that has been released to the atmosphere due to human activities in modern time. One manifestation of this is yedoma, which is an organic-rich (about 2% carbon by mass)

In 1999, researchers were able to extract potentially viable microscopic

In 1999, researchers were able to extract potentially viable microscopic  Scientists are split on whether revived microorganisms from the permafrost can pose a significant threat to humans. Jean-Michel Claverie, who led the only successful attempts to revive such "zombie viruses", believes that the

Scientists are split on whether revived microorganisms from the permafrost can pose a significant threat to humans. Jean-Michel Claverie, who led the only successful attempts to revive such "zombie viruses", believes that the

Prior to World War II, there were not many scientific publications on frozen ground in

Prior to World War II, there were not many scientific publications on frozen ground in

Center for PermafrostInternational Permafrost Association (IPA)Pleistocene & Permafrost Foundation

Permafrost – what is it? – Alfred Wegener Institute YouTube video

{{Authority control Geography of the Arctic Geomorphology Montane ecology Patterned grounds Pedology Periglacial landforms 1940s neologisms Cryosphere

soil

Soil, also commonly referred to as earth or dirt, is a mixture of organic matter, minerals, gases, liquids, and organisms that together support life. Some scientific definitions distinguish ''dirt'' from ''soil'' by restricting the former te ...

or underwater sediment

Sediment is a naturally occurring material that is broken down by processes of weathering and erosion, and is subsequently transported by the action of wind, water, or ice or by the force of gravity acting on the particles. For example, sand an ...

which continuously remains below for two or more years. Land-based permafrost can include the surface layer

The surface layer is the layer of a turbulent fluid most affected by interaction with a solid surface or the surface separating a gas and a liquid where the characteristics of the turbulence depend on distance from the interface. Surface layers a ...

of the soil, but if the surface is too warm, it may still occur within a few centimeters of the surface down to hundreds of meters. It usually consists of ice

Ice is water frozen into a solid state, typically forming at or below temperatures of 0 degrees Celsius or Depending on the presence of impurities such as particles of soil or bubbles of air, it can appear transparent or a more or less opaq ...

holding in place a combination of various types of soil, sand

Sand is a granular material composed of finely divided mineral particles. Sand has various compositions but is defined by its grain size. Sand grains are smaller than gravel and coarser than silt. Sand can also refer to a textural class of s ...

, and rock

Rock most often refers to:

* Rock (geology), a naturally occurring solid aggregate of minerals or mineraloids

* Rock music, a genre of popular music

Rock or Rocks may also refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* Rock, Caerphilly, a location in Wales ...

, though in ice-free ground, perennially frozen non-porous bedrock

In geology, bedrock is solid Rock (geology), rock that lies under loose material (regolith) within the crust (geology), crust of Earth or another terrestrial planet.

Definition

Bedrock is the solid rock that underlies looser surface mater ...

can serve the same role.

Around 15% of the Northern Hemisphere

The Northern Hemisphere is the half of Earth that is north of the Equator. For other planets in the Solar System, north is defined as being in the same celestial hemisphere relative to the invariable plane of the solar system as Earth's Nort ...

or 11% of the global surface is underlain by permafrost, with the total area of around . This includes substantial areas of Alaska

Alaska ( ; russian: Аляска, Alyaska; ale, Alax̂sxax̂; ; ems, Alas'kaaq; Yup'ik: ''Alaskaq''; tli, Anáaski) is a state located in the Western United States on the northwest extremity of North America. A semi-exclave of the U.S., ...

, Greenland

Greenland ( kl, Kalaallit Nunaat, ; da, Grønland, ) is an island country in North America that is part of the Kingdom of Denmark. It is located between the Arctic and Atlantic oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Greenland is t ...

, Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

, and Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part of ...

. It is also located in high mountain regions, with the Tibetan Plateau

The Tibetan Plateau (, also known as the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau or the Qing–Zang Plateau () or as the Himalayan Plateau in India, is a vast elevated plateau located at the intersection of Central, South and East Asia covering most of the Ti ...

a prominent example. Only a minority of permafrost exists in the Southern Hemisphere, where it is consigned to mountain slopes like in the Andes

The Andes, Andes Mountains or Andean Mountains (; ) are the longest continental mountain range in the world, forming a continuous highland along the western edge of South America. The range is long, wide (widest between 18°S – 20°S ...

or the Southern Alps of New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island count ...

, and beneath the massive ice sheets of the Antarctic

The Antarctic ( or , American English also or ; commonly ) is a polar region around Earth's South Pole, opposite the Arctic region around the North Pole. The Antarctic comprises the continent of Antarctica, the Kerguelen Plateau and other ...

.

Permafrost contains large amounts of dead biomass

Biomass is plant-based material used as a fuel for heat or electricity production. It can be in the form of wood, wood residues, energy crops, agricultural residues, and waste from industry, farms, and households. Some people use the terms bi ...

that had accumulated throughout millennia without having had the chance to fully decompose and release its carbon

Carbon () is a chemical element with the symbol C and atomic number 6. It is nonmetallic and tetravalent

In chemistry, the valence (US spelling) or valency (British spelling) of an element is the measure of its combining capacity with o ...

, making tundra

In physical geography, tundra () is a type of biome where tree growth is hindered by frigid temperatures and short growing seasons. The term ''tundra'' comes through Russian (') from the Kildin Sámi word (') meaning "uplands", "treeless moun ...

soil a carbon sink. As global warming

In common usage, climate change describes global warming—the ongoing increase in global average temperature—and its effects on Earth's climate system. Climate change in a broader sense also includes previous long-term changes to E ...

heats the ecosystem, frozen soil thaws and becomes warm enough for decomposition to start anew, accelerating permafrost carbon cycle. Depending on conditions at the time of thaw, decomposition can either release carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide (chemical formula ) is a chemical compound made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in the gas state at room temperature. In the air, carbon dioxide is transpar ...

or methane

Methane ( , ) is a chemical compound with the chemical formula (one carbon atom bonded to four hydrogen atoms). It is a group-14 hydride, the simplest alkane, and the main constituent of natural gas. The relative abundance of methane on Eart ...

, and these greenhouse gas emissions

Greenhouse gas emissions from human activities strengthen the greenhouse effect, contributing to climate change. Most is carbon dioxide from burning fossil fuels: coal, oil, and natural gas. The largest emitters include coal in China and lar ...

act as a climate change feedback

Climate change feedbacks are important in the understanding of global warming because feedback processes amplify or diminish the effect of each climate forcing, and so play an important part in determining the climate sensitivity and future clim ...

. The emissions from thawing permafrost will have a sufficient impact on the climate to impact global carbon budgets. Exact estimates of permafrost emissions are hard to model because of the uncertainty about different thaw processes. There's a widespread agreement they will be smaller than human-caused emissions and not large enough to result in " runaway warming".Fox-Kemper, B., H.T. Hewitt, C. Xiao, G. Aðalgeirsdóttir, S.S. Drijfhout, T.L. Edwards, N.R. Golledge, M. Hemer, R.E. Kopp, G. Krinner, A. Mix, D. Notz, S. Nowicki, I.S. Nurhati, L. Ruiz, J.-B. Sallée, A.B.A. Slangen, and Y. Yu, 2021Chapter 9: Ocean, Cryosphere and Sea Level Change

I

Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

[Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S.L. Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, M.I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J.B.R. Matthews, T.K. Maycock, T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, R. Yu, and B. Zhou (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, pp. 1211–1362.

In addition to its climate impact, permafrost thaw brings additional risks. Formerly frozen ground often contains enough ice that when it thaws, hydraulic saturation is suddenly exceeded, so the ground shifts substantially and may even collapse outright. Many buildings and other

In addition to its climate impact, permafrost thaw brings additional risks. Formerly frozen ground often contains enough ice that when it thaws, hydraulic saturation is suddenly exceeded, so the ground shifts substantially and may even collapse outright. Many buildings and other infrastructure

Infrastructure is the set of facilities and systems that serve a country, city, or other area, and encompasses the services and facilities necessary for its economy, households and firms to function. Infrastructure is composed of public and priv ...

were built on permafrost when it was frozen and stable, and so are vulnerable to collapse if it thaws. Estimates suggest nearly 70% of such infrastructure is at risk by 2050, and that the associated costs could rise to tens of billions of dollars in the second half of the century. Furthermore, around 20,000 sites contaminated with toxic waste are present in the permafrost, as well as the natural mercury

Mercury commonly refers to:

* Mercury (planet), the nearest planet to the Sun

* Mercury (element), a metallic chemical element with the symbol Hg

* Mercury (mythology), a Roman god

Mercury or The Mercury may also refer to:

Companies

* Merc ...

deposits, which are all liable to leak and pollute the environment as the warming progresses. Lastly, there have been concerns about potentially pathogenic

In biology, a pathogen ( el, πάθος, "suffering", "passion" and , "producer of") in the oldest and broadest sense, is any organism or agent that can produce disease. A pathogen may also be referred to as an infectious agent, or simply a germ ...

microorganisms surviving the thaw and contributing to future epidemic

An epidemic (from Ancient Greek, Greek ἐπί ''epi'' "upon or above" and δῆμος ''demos'' "people") is the rapid spread of disease to a large number of patients among a given population within an area in a short period of time.

Epidemics ...

s and pandemic

A pandemic () is an epidemic of an infectious disease that has spread across a large region, for instance multiple continents or worldwide, affecting a substantial number of individuals. A widespread endemic (epidemiology), endemic disease wi ...

s, although this risk is speculative and is considered implausible by much of the scientific community.

Classification and extent

Permafrost is

Permafrost is soil

Soil, also commonly referred to as earth or dirt, is a mixture of organic matter, minerals, gases, liquids, and organisms that together support life. Some scientific definitions distinguish ''dirt'' from ''soil'' by restricting the former te ...

, rock

Rock most often refers to:

* Rock (geology), a naturally occurring solid aggregate of minerals or mineraloids

* Rock music, a genre of popular music

Rock or Rocks may also refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* Rock, Caerphilly, a location in Wales ...

or sediment

Sediment is a naturally occurring material that is broken down by processes of weathering and erosion, and is subsequently transported by the action of wind, water, or ice or by the force of gravity acting on the particles. For example, sand an ...

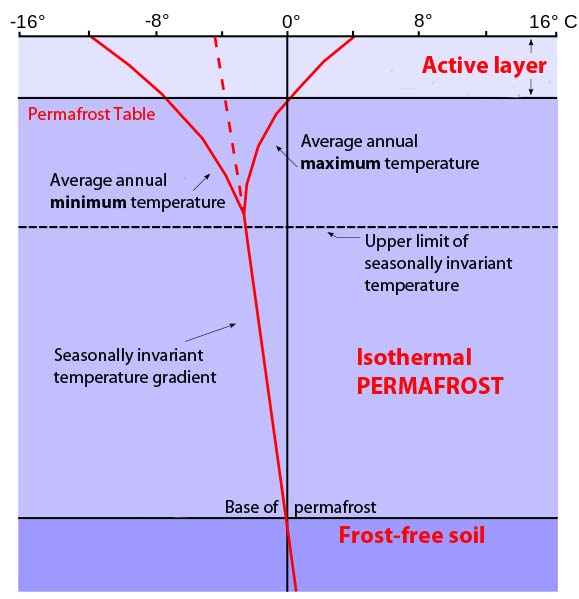

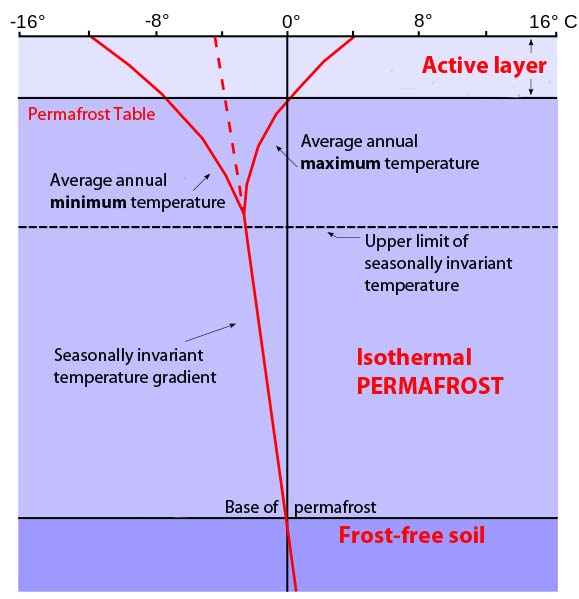

that is frozen for more than two consecutive years. In areas not covered by ice, it exists beneath a layer of soil, rock or sediment, which freezes and thaws annually and is called the " active layer". In practice, this means that permafrost occurs at an mean annual temperature of or below. Active layer thickness varies with the season, but is 0.3 to 4 meters thick (shallow along the Arctic coast; deep in southern Siberia and the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau

The Tibetan Plateau (, also known as the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau or the Qing–Zang Plateau () or as the Himalayan Plateau in India, is a vast elevated plateau located at the intersection of Central, South and East Asia covering most of the Tib ...

).

The extent of permafrost is displayed in terms of permafrost zones, which are defined according to the area underlain by permafrost as continuous (90%–100%), discontinuous (50%–90%), sporadic (10%–50%), and isolated patches (10% or less). These permafrost zones cover together approximately 22% of the Northern Hemisphere. Continuous permafrost zone covers slightly more than half of this area, discontinuous permafrost around 20 percent, and sporadic permafrost together with isolated patches little less than 30 percent. Because permafrost zones are not entirely underlain by permafrost, only 15% of the ice-free area of the Northern Hemisphere

The Northern Hemisphere is the half of Earth that is north of the Equator. For other planets in the Solar System, north is defined as being in the same celestial hemisphere relative to the invariable plane of the solar system as Earth's Nort ...

is actually underlain by permafrost. Most of this area is found in Siberia, northern Canada, Alaska and Greenland. Beneath the active layer annual temperature swings of permafrost become smaller with depth. The deepest depth of permafrost occurs where geothermal heat maintains a temperature above freezing. Above that bottom limit there may be permafrost with a consistent annual temperature—"isothermal permafrost".

Continuity of coverage

Permafrost typically forms in anyclimate

Climate is the long-term weather pattern in an area, typically averaged over 30 years. More rigorously, it is the mean and variability of meteorological variables over a time spanning from months to millions of years. Some of the meteorologic ...

where the mean annual air temperature is lower than the freezing point of water

Water (chemical formula ) is an inorganic, transparent, tasteless, odorless, and nearly colorless chemical substance, which is the main constituent of Earth's hydrosphere and the fluids of all known living organisms (in which it acts as a ...

. Exceptions are found in humid boreal forests, such as in Northern Scandinavia and the North-Eastern part of European Russia west of the Urals

The Ural Mountains ( ; rus, Ура́льские го́ры, r=Uralskiye gory, p=ʊˈralʲskʲɪjə ˈɡorɨ; ba, Урал тауҙары) or simply the Urals, are a mountain range that runs approximately from north to south through European ...

, where snow acts as an insulating blanket. Glaciated areas may also be exceptions. Since all glaciers are warmed at their base by geothermal heat, temperate glaciers, which are near the pressure-melting point throughout, may have liquid water at the interface with the ground and are therefore free of underlying permafrost. "Fossil" cold anomalies in the Geothermal gradient in areas where deep permafrost developed during the Pleistocene persist down to several hundred metres. This is evident from temperature measurements in boreholes in North America and Europe.

Discontinuous permafrost

The below-ground temperature varies less from season to season than the air temperature, with mean annual temperatures tending to increase with depth as a result of the geothermal crustal gradient. Thus, if the mean annual air temperature is only slightly below , permafrost will form only in spots that are sheltered—usually with a northern or southernaspect

Aspect or Aspects may refer to:

Entertainment

* ''Aspect magazine'', a biannual DVD magazine showcasing new media art

* Aspect Co., a Japanese video game company

* Aspects (band), a hip hop group from Bristol, England

* ''Aspects'' (Benny Carter ...

(in north and south hemispheres respectively) —creating ''discontinuous permafrost''. Usually, permafrost will remain discontinuous in a climate where the mean annual soil surface temperature is between . In the moist-wintered areas mentioned before, there may not be even discontinuous permafrost down to . Discontinuous permafrost is often further divided into ''extensive discontinuous permafrost'', where permafrost covers between 50 and 90 percent of the landscape and is usually found in areas with mean annual temperatures between , and ''sporadic permafrost'', where permafrost cover is less than 50 percent of the landscape and typically occurs at mean annual temperatures between .

In soil science, the sporadic permafrost zone is abbreviated SPZ and the extensive discontinuous permafrost zone DPZ. Exceptions occur in ''un-glaciated'' Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part of ...

and Alaska

Alaska ( ; russian: Аляска, Alyaska; ale, Alax̂sxax̂; ; ems, Alas'kaaq; Yup'ik: ''Alaskaq''; tli, Anáaski) is a state located in the Western United States on the northwest extremity of North America. A semi-exclave of the U.S., ...

where the present depth of permafrost is a relic

In religion, a relic is an object or article of religious significance from the past. It usually consists of the physical remains of a saint or the personal effects of the saint or venerated person preserved for purposes of veneration as a tangi ...

of climatic conditions during glacial ages where winters were up to colder than those of today.

Continuous permafrost

At mean annual soil surface temperatures below the influence of aspect can never be sufficient to thaw permafrost and a zone of ''continuous permafrost'' (abbreviated to CPZ) forms. A ''line of continuous permafrost'' in theNorthern Hemisphere

The Northern Hemisphere is the half of Earth that is north of the Equator. For other planets in the Solar System, north is defined as being in the same celestial hemisphere relative to the invariable plane of the solar system as Earth's Nort ...

represents the most southern border where land is covered by continuous permafrost or glacial ice. The line of continuous permafrost varies around the world northward or southward due to regional climatic changes. In the southern hemisphere, most of the equivalent line would fall within the Southern Ocean

The Southern Ocean, also known as the Antarctic Ocean, comprises the southernmost waters of the World Ocean, generally taken to be south of 60° S latitude and encircling Antarctica. With a size of , it is regarded as the second-small ...

if there were land there. Most of the Antarctic continent

Antarctica () is Earth's southernmost and least-populated continent. Situated almost entirely south of the Antarctic Circle and surrounded by the Southern Ocean, it contains the geographic South Pole. Antarctica is the fifth-largest contine ...

is overlain by glaciers, under which much of the terrain is subject to basal melting

Melting, or fusion, is a physical process that results in the phase transition of a substance from a solid to a liquid. This occurs when the internal energy of the solid increases, typically by the application of heat or pressure, which incre ...

. The exposed land of Antarctica is substantially underlain with permafrost, some of which is subject to warming and thawing along the coastline.

Alpine permafrost

Alpine permafrost occurs at elevations with low enough average temperatures to sustain perennially frozen ground; much alpine permafrost is discontinuous. Estimates of the total area of alpine permafrost vary. Bockheim and Munroe combined three sources and made the tabulated estimates by region, totaling . Alpine permafrost in theAndes

The Andes, Andes Mountains or Andean Mountains (; ) are the longest continental mountain range in the world, forming a continuous highland along the western edge of South America. The range is long, wide (widest between 18°S – 20°S ...

has not been mapped. Its extent has been modeled to assess the amount of water bound up in these areas. In 2009, a researcher from Alaska found permafrost at the level on Africa's highest peak, Mount Kilimanjaro

Mount Kilimanjaro () is a dormant volcano in Tanzania. It has three volcanic cones: Kibo, Mawenzi, and Shira. It is the highest mountain in Africa and the highest free-standing mountain above sea level in the world: above sea level and ab ...

, approximately 3° south of the equator.

Subsea permafrost

Subsea permafrost occurs beneath the seabed and exists in the continental shelves of the polar regions. These areas formed during the last ice age, when a larger portion of Earth's water was bound up in ice sheets on land and when sea levels were low. As the ice sheets melted to again become seawater, the permafrost became submerged shelves under relatively warm and salty boundary conditions, compared to surface permafrost. Therefore, subsea permafrost exists in conditions that lead to its diminishment. According to Osterkamp, subsea permafrost is a factor in the "design, construction, and operation of coastal facilities, structures founded on the seabed, artificial islands, sub-sea pipelines, and wells drilled for exploration and production." It also contains gas hydrates in places, which are a "potential abundant source of energy" but may also destabilize as subsea permafrost warms and thaws, producing large amounts of methane gas, which is a potent greenhouse gas. Scientists report with high confidence that the extent of subsea permafrost is decreasing, and 97% of permafrost under Arctic ice shelves is currently thinning.Past extent of permafrost

At theLast Glacial Maximum

The Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), also referred to as the Late Glacial Maximum, was the most recent time during the Last Glacial Period that ice sheets were at their greatest extent.

Ice sheets covered much of Northern North America, Northern Eur ...

, continuous permafrost covered a much greater area than it does today, covering all of ice-free Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

south to about Szeged (southeastern Hungary) and the Sea of Azov

The Sea of Azov ( Crimean Tatar: ''Azaq deñizi''; russian: Азовское море, Azovskoye more; uk, Азовське море, Azovs'ke more) is a sea in Eastern Europe connected to the Black Sea by the narrow (about ) Strait of Kerch, ...

(then dry land) and East Asia

East Asia is the eastern region of Asia, which is defined in both geographical and ethno-cultural terms. The modern states of East Asia include China, Japan, Mongolia, North Korea, South Korea, and Taiwan. China, North Korea, South Korea and ...

south to present-day Changchun

Changchun (, ; ), also romanized as Ch'angch'un, is the capital and largest city of Jilin Province, People's Republic of China. Lying in the center of the Songliao Plain, Changchun is administered as a , comprising 7 districts, 1 county and 3 c ...

and Abashiri. In North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and the Car ...

, only an extremely narrow belt of permafrost existed south of the ice sheet at about the latitude of New Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York; on the east, southeast, and south by the Atlantic Ocean; on the west by the Delaware ...

through southern Iowa

Iowa () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States, bordered by the Mississippi River to the east and the Missouri River and Big Sioux River to the west. It is bordered by six states: Wisconsin to the northeast, Illinois to the ...

and northern Missouri

Missouri is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking List of U.S. states and territories by area, 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee ...

, but permafrost was more extensive in the drier western regions where it extended to the southern border of Idaho

Idaho ( ) is a state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. To the north, it shares a small portion of the Canada–United States border with the province of British Columbia. It borders the states of Montana and Wyom ...

and Oregon

Oregon () is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. The Columbia River delineates much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while the Snake River delineates much of it ...

. In the southern hemisphere, there is some evidence for former permafrost from this period in central Otago

Otago (, ; mi, Ōtākou ) is a region of New Zealand located in the southern half of the South Island administered by the Otago Regional Council. It has an area of approximately , making it the country's second largest local government reg ...

and Argentine

Argentines (mistakenly translated Argentineans in the past; in Spanish (masculine) or (feminine)) are people identified with the country of Argentina. This connection may be residential, legal, historical or cultural. For most Argentines, s ...

Patagonia, but was probably discontinuous, and is related to the tundra. Alpine permafrost also occurred in the Drakensberg during glacial maxima above about .

Manifestations

Base depth

Permafrost extends to a base depth where geothermal heat from the Earth and the mean annual temperature at the surface achieve an equilibrium temperature of 0 °C. The base depth of permafrost reaches in the northernLena

Lena or LENA may refer to:

Places

* Léna Department, a department of Houet Province in Burkina Faso

* Lena, Manitoba, an unincorporated community located in Killarney-Turtle Mountain municipality in Manitoba, Canada

* Lena, Norway, a village in � ...

and Yana River basins in Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part of ...

.

The geothermal gradient is the rate of increasing temperature with respect to increasing depth in the Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to harbor life. While large volumes of water can be found throughout the Solar System, only Earth sustains liquid surface water. About 71% of Earth's surfa ...

's interior. Away from tectonic plate boundaries, it is about 25–30 °C/km (124–139 °F/mi) near the surface in most of the world. It varies with the thermal conductivity of geologic material and is less for permafrost in soil than in bedrock.

Calculations indicate that the time required to form the deep permafrost underlying Prudhoe Bay, Alaska was over a half-million years. This extended over several glacial and interglacial cycles of the Pleistocene

The Pleistocene ( , often referred to as the ''Ice age'') is the geological Epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 2,580,000 to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was fina ...

and suggests that the present climate of Prudhoe Bay is probably considerably warmer than it has been on average over that period. Such warming over the past 15,000 years is widely accepted. The table to the right shows that the first hundred metres of permafrost forms relatively quickly but that deeper levels take progressively longer.

Massive ground ice

When the ice content of a permafrost exceeds 250 percent (ice to dry soil by mass) it is classified as ''massive'' ice. Massive ice bodies can range in composition, in every conceivable gradation from icy mud to pure ice. Massive icy beds have a minimum thickness of at least 2 m and a short diameter of at least 10 m.

First recorded North American observations were by European scientists at Canning River, Alaska in 1919.

Russian literature provides an earlier date of 1735 and 1739 during the Great North Expedition by P. Lassinius and Kh. P. Laptev, respectively.

Two categories of massive ground ice are ''buried surface ice'' and ''intrasedimental ice''

(also called ''constitutional ice'').

Buried surface ice may derive from snow, frozen lake or sea ice,

When the ice content of a permafrost exceeds 250 percent (ice to dry soil by mass) it is classified as ''massive'' ice. Massive ice bodies can range in composition, in every conceivable gradation from icy mud to pure ice. Massive icy beds have a minimum thickness of at least 2 m and a short diameter of at least 10 m.

First recorded North American observations were by European scientists at Canning River, Alaska in 1919.

Russian literature provides an earlier date of 1735 and 1739 during the Great North Expedition by P. Lassinius and Kh. P. Laptev, respectively.

Two categories of massive ground ice are ''buried surface ice'' and ''intrasedimental ice''

(also called ''constitutional ice'').

Buried surface ice may derive from snow, frozen lake or sea ice, aufeis

Aufeis, ( ), (German for "ice on top") is a sheet-like mass of layered ice that forms from successive flows of ground or river water during freezing temperatures. This form of ice is also called overflow, icings, or the Russian term, naled. The t ...

(stranded river ice) and—probably the most prevalent—buried glacial ice.

Intrasedimental ice forms by in-place freezing of subterranean waters and is dominated by segregational ice which results from the crystallizational differentiation taking place during the freezing of wet sediments, accompanied by water migrating to the freezing front.

Intrasedimental or constitutional ice has been widely observed and studied across Canada and also includes intrusive and injection ice.

Globally, permafrost warmed by about between 2007 and 2016, with stronger warming observed in the continuous permafrost zone relative to the discontinuous zone. This inevitably causes permafrost to thaw. Permafrost extent has been diminishing for decades, and more decline is expected in the future. This causes a wide range of issues, and International Permafrost Association (IPA) exists to help address them. It convenes International Permafrost Conferences and maintains Global Terrestrial Network for Permafrost

The Global Terrestrial Network for Permafrost (GTN‐P) is the primary international programme concerned with monitoring permafrost parameters. GTN‐P was developed in the 1990s by the International Permafrost Association (IPA) under the Glob ...

, which undertakes special projects such as preparing databases, maps, bibliographies, and glossaries, and coordinates international field programmes and networks.

Thaw-induced ground instability

As the water drains or evaporates, soil structure weakens and sometimes becomes viscous until it regains strength with decreasing moisture content. One visible sign of permafrost degradation is the random displacement of trees from their vertical orientation in permafrost areas. Global warming has been increasing permafrost slope disturbances and sediment supplies to fluvial systems, resulting in exceptional increases in river sediment. On the other hands, disturbance of formerly hard soil increases drainage of water reservoirs in northern

As the water drains or evaporates, soil structure weakens and sometimes becomes viscous until it regains strength with decreasing moisture content. One visible sign of permafrost degradation is the random displacement of trees from their vertical orientation in permafrost areas. Global warming has been increasing permafrost slope disturbances and sediment supplies to fluvial systems, resulting in exceptional increases in river sediment. On the other hands, disturbance of formerly hard soil increases drainage of water reservoirs in northern wetland

A wetland is a distinct ecosystem that is flooded or saturated by water, either permanently (for years or decades) or seasonally (for weeks or months). Flooding results in oxygen-free (anoxic) processes prevailing, especially in the soils. The ...

s. This can dry them out and compromise the survival of plants and animals used to the wetland ecosystem.

In high mountains, much of the structural stability can be attributed to glaciers and permafrost. As climate warms, permafrost thaws, decreasing slope stability and increasing stress through buildup of pore-water pressure, which may ultimately lead to slope failure and rockfalls. Over the past century, an increasing number of alpine rock slope failure events in mountain ranges around the world have been recorded, and some have been attributed to permafrost thaw induced by climate change. The 1987 Val Pola landslide

The Val Pola landslide (Val Pola rock avalanche) happened in Valtellina, Lombardy, Northern Italian Alps, on July 28, 1987 and resulted in the Valtellina disaster (destruction of villages, road closure, and flooding threat) with a total cost of 4 ...

that killed 22 people in the Italian Alps is considered one such example. In 2002, massive rock and ice falls (up to 11.8 million m3), earthquake

An earthquake (also known as a quake, tremor or temblor) is the shaking of the surface of the Earth resulting from a sudden release of energy in the Earth's lithosphere that creates seismic waves. Earthquakes can range in intensity, from ...

s (up to 3.9 Richter), flood

A flood is an overflow of water ( or rarely other fluids) that submerges land that is usually dry. In the sense of "flowing water", the word may also be applied to the inflow of the tide. Floods are an area of study of the discipline hydrol ...

s (up to 7.8 million m3 water), and rapid rock-ice flow to long distances (up to 7.5 km at 60 m/s) were attributed to slope instability in high mountain permafrost.

Permafrost thaw can also result in the formation of frozen debris lobes (FDLs), which are defined as "slow-moving landslides composed of soil, rocks, trees, and ice". This is a notable issue in the

Permafrost thaw can also result in the formation of frozen debris lobes (FDLs), which are defined as "slow-moving landslides composed of soil, rocks, trees, and ice". This is a notable issue in the Alaska

Alaska ( ; russian: Аляска, Alyaska; ale, Alax̂sxax̂; ; ems, Alas'kaaq; Yup'ik: ''Alaskaq''; tli, Anáaski) is a state located in the Western United States on the northwest extremity of North America. A semi-exclave of the U.S., ...

's southern Brooks Range

The Brooks Range ( Gwich'in: ''Gwazhał'') is a mountain range in far northern North America stretching some from west to east across northern Alaska into Canada's Yukon Territory. Reaching a peak elevation of on Mount Isto, the range is believ ...

, where some FDLs measured over in width, in height, and in length by 2012. As of December 2021, there were 43 frozen debris lobes identified in the southern Brooks Range, where they could potentially threaten both the Trans Alaska Pipeline System

The Trans-Alaska Pipeline System (TAPS) is an oil transportation system spanning Alaska, including the trans-Alaska crude-oil pipeline, 11 pump stations, several hundred miles of feeder pipelines, and the Valdez Marine Terminal. TAPS is one of ...

(TAPS) corridor and the Dalton Highway

The James W. Dalton Highway, usually referred to as the Dalton Highway (and signed as Alaska Route 11), is a road in Alaska. It begins at the Elliott Highway, north of Fairbanks, and ends at Deadhorse (an unincorporated community within the ...

, which is the main transport link between the Interior Alaska and the Alaska North Slope

The Alaska North Slope ( Iñupiaq: ''Siḷaliñiq'') is the region of the U.S. state of Alaska located on the northern slope of the Brooks Range along the coast of two marginal seas of the Arctic Ocean, the Chukchi Sea being on the western sid ...

.

Infrastructure

As of 2021, there are 1162 settlements located directly atop the Arctic permafrost, which host an estimated 5 million people. By 2050, permafrost layer below 42% of these settlements is expected to thaw, affecting all their inhabitants (currently 3.3 million people). Consequently, a wide range of

As of 2021, there are 1162 settlements located directly atop the Arctic permafrost, which host an estimated 5 million people. By 2050, permafrost layer below 42% of these settlements is expected to thaw, affecting all their inhabitants (currently 3.3 million people). Consequently, a wide range of infrastructure

Infrastructure is the set of facilities and systems that serve a country, city, or other area, and encompasses the services and facilities necessary for its economy, households and firms to function. Infrastructure is composed of public and priv ...

in permafrost areas is threatened by the thaw. By 2050, it's estimated that nearly 70% of global infrastructure located in the permafrost areas would be at high risk of permafrost thaw, including 30-50% of "critical" infrastructure. The associated costs could reach tens of billions of dollars by the second half of the century. Reducing greenhouse gas emissions

Greenhouse gas emissions from human activities strengthen the greenhouse effect, contributing to climate change. Most is carbon dioxide from burning fossil fuels: coal, oil, and natural gas. The largest emitters include coal in China and lar ...

in line with the Paris Agreement

The Paris Agreement (french: Accord de Paris), often referred to as the Paris Accords or the Paris Climate Accords, is an international treaty on climate change. Adopted in 2015, the agreement covers climate change mitigation, Climate change a ...

is projected to stabilize the risk after mid-century; otherwise, it'll continue to worsen.

In Alaska

Alaska ( ; russian: Аляска, Alyaska; ale, Alax̂sxax̂; ; ems, Alas'kaaq; Yup'ik: ''Alaskaq''; tli, Anáaski) is a state located in the Western United States on the northwest extremity of North America. A semi-exclave of the U.S., ...

alone, damages to infrastructure by the end of the century would amount to $4.6 billion (at 2015 dollar value) if RCP8.5, the high-emission climate change scenario

Climate change scenarios or socioeconomic scenarios are projections of future greenhouse gas emissions, greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions used by analysts to assess future Climate change vulnerability, vulnerability to climate change. Scenarios and ...

, were realized. Over half stems from the damage to buildings ($2.8 billion), but there's also damage to road

A road is a linear way for the conveyance of traffic that mostly has an improved surface for use by vehicles (motorized and non-motorized) and pedestrians. Unlike streets, the main function of roads is transportation.

There are many types of ...

s ($700 million), railroad

Rail transport (also known as train transport) is a means of transport that transfers passengers and goods on wheeled vehicles running on rails, which are incorporated in tracks. In contrast to road transport, where the vehicles run on a pre ...

s ($620 million), airport

An airport is an aerodrome with extended facilities, mostly for commercial air transport. Airports usually consists of a landing area, which comprises an aerially accessible open space including at least one operationally active surface ...

s ($360 million) and pipeline

Pipeline may refer to:

Electronics, computers and computing

* Pipeline (computing), a chain of data-processing stages or a CPU optimization found on

** Instruction pipelining, a technique for implementing instruction-level parallelism within a s ...

s ($170 million). Similar estimates were done for RCP4.5, a less intense scenario which leads to around by 2100, a level of warming similar to the current projections. In that case, total damages from permafrost thaw are reduced to $3 billion, while damages to roads and railroads are lessened by approximately two thirds (from $700 and $620 million to $190 and $220 million) and damages to pipelines are reduced more than ten-fold, from $170 million to $16 million. Unlike the other costs stemming from climate change in Alaska, such as damages from increased precipitation

In meteorology, precipitation is any product of the condensation of atmospheric water vapor that falls under gravitational pull from clouds. The main forms of precipitation include drizzle, rain, sleet, snow, ice pellets, graupel and hail. ...

and flooding, climate change adaptation is not a viable way to reduce damages from permafrost thaw, as it would cost more than the damage incurred under either scenario.

In Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

, Northwest Territories

The Northwest Territories (abbreviated ''NT'' or ''NWT''; french: Territoires du Nord-Ouest, formerly ''North-Western Territory'' and ''North-West Territories'' and namely shortened as ''Northwest Territory'') is a federal territory of Canada. ...

have a population of only 45,000 people in 33 communities, yet permafrost thaw is expected to cost them $1.3 billion over 75 years, or around $51 million a year. In 2006, the cost of adapting Inuvialuit homes to permafrost thaw was estimated at $208/m2 if they were built at pile foundations, and $1,000/m2 if they didn't. At the time, the average area of a residential building in the territory was around 100 m2. Thaw-induced damage is also unlikely to be covered by home insurance

Home insurance, also commonly called homeowner's insurance (often abbreviated in the US real estate industry as HOI), is a type of property insurance that covers a private residence. It is an insurance policy that combines various personal insura ...

, and to address this reality, territorial government currently funds Contributing Assistance for Repairs and Enhancements (CARE) and Securing Assistance for Emergencies (SAFE) programs, which provide long- and short-term forgivable loans to help homeowners adapt. It is possible that in the future, mandatory relocation would instead take place as the cheaper option. However, it would effectively tear the local Inuit

Inuit (; iu, ᐃᓄᐃᑦ 'the people', singular: Inuk, , dual: Inuuk, ) are a group of culturally similar indigenous peoples inhabiting the Arctic and subarctic regions of Greenland, Labrador, Quebec, Nunavut, the Northwest Territories ...

away from their ancestral homelands. Right now, their average personal income is only half that of the median NWT resident, meaning that adaptation costs are already disproportionate for them.

By 2022, up to 80% of buildings in some Northern Russia

Russian North (russian: Русский Север) is an ethnocultural region situated in the northwestern part of Russia. It spans the regions of Arkhangelsk Oblast, the Republic of Karelia, Komi Republic, Vologda Oblast and Nenets Autonomous ...

cities had already experienced damage. By 2050, the damage to residential infrastructure may reach $15 billion, while total public infrastructure damages could amount to 132 billion. This includes oil and gas

A fossil fuel is a hydrocarbon-containing material formed naturally in the Earth's crust from the remains of dead plants and animals that is extracted and burned as a fuel. The main fossil fuels are coal, oil, and natural gas. Fossil fuels ...

extraction facilities, of which 45% are believed to be at risk.

Outside of the Arctic,

Outside of the Arctic, Qinghai–Tibet Plateau

The Tibetan Plateau (, also known as the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau or the Qing–Zang Plateau () or as the Himalayan Plateau in India, is a vast elevated plateau located at the intersection of Central Asia, Central, South Asia, South and East Asi ...

(sometimes known as "the Third Pole"), also has an extensive permafrost area. It is warming at twice the global average rate, and 40% of it is already considered "warm" permafrost, making it particularly unstable. Qinghai–Tibet Plateau has a population of over 10 million people - double the population of permafrost regions in the Arctic - and over 1 million m2 of buildings are located in its permafrost area, as well as 2,631 km of power lines, and 580 km of railways. There are also 9,389 km of roads, and around 30% are already sustaining damage from permafrost thaw. Estimates suggest that under the scenario most similar to today, SSP2-4.5, around 60% of the current infrastructure would be at high risk by 2090 and simply maintaining it would cost $6.31 billion, with adaptation reducing these costs by 20.9% at most. Holding the global warming to would reduce these costs to $5.65 billion, and fulfilling the optimistic Paris Agreement

The Paris Agreement (french: Accord de Paris), often referred to as the Paris Accords or the Paris Climate Accords, is an international treaty on climate change. Adopted in 2015, the agreement covers climate change mitigation, Climate change a ...

target of would save a further $1.32 billion. In particular, fewer than 20% of railways would be at high risk by 2100 under , yet this increases to 60% at , while under SSP5-8.5, this level of risk is met by mid-century.

Toxic pollution

For much of the 20th century, it was believed that permafrost would "indefinitely" preserve anything buried there, and this made deep permafrost areas popular locations for hazardous waste disposal. In places like Canada's

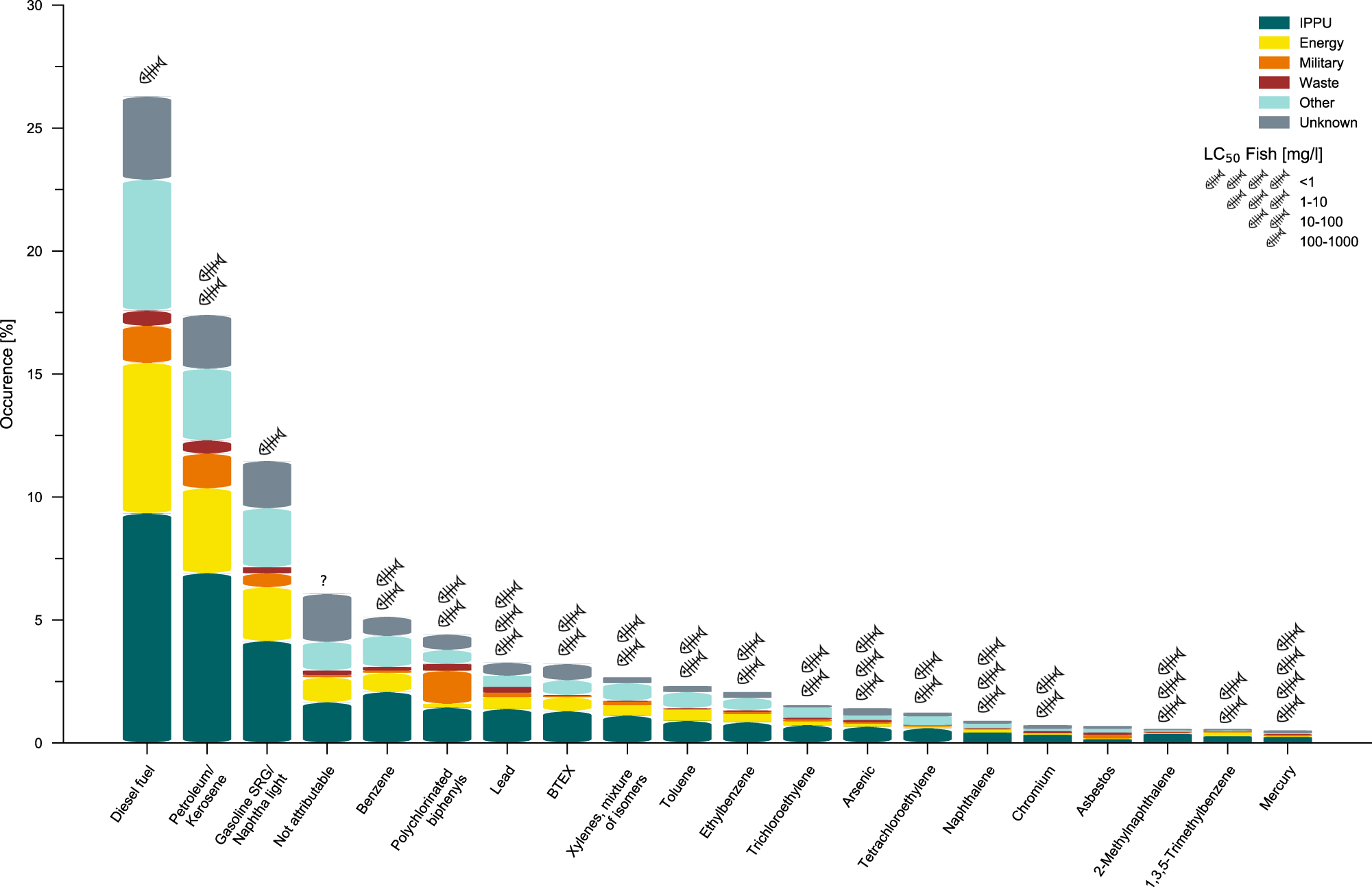

For much of the 20th century, it was believed that permafrost would "indefinitely" preserve anything buried there, and this made deep permafrost areas popular locations for hazardous waste disposal. In places like Canada's Prudhoe Bay

Prudhoe Bay is a census-designated place (CDP) located in North Slope Borough in the U.S. state of Alaska. As of the 2010 census, the population of the CDP was 2,174 people, up from just five residents in the 2000 census; however, at any give ...

oil field, procedures were developed documenting the "appropriate" way to inject waste beneath the permafrost. This means that as of 2023, there are ~4500 industrial facilities in the Arctic permafrost areas which either actively process or store hazardous chemicals. Additionally, there are between 13,000 and 20,000 sites which have been heavily contaminated, 70% of them in Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia, Northern Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the ...

, and their pollution

Pollution is the introduction of contaminants into the natural environment that cause adverse change. Pollution can take the form of any substance (solid, liquid, or gas) or energy (such as radioactivity, heat, sound, or light). Pollutants, the ...

is currently trapped in the permafrost. About a fifth of both the industrial and the polluted sites (1000 and 2200–4800) are expected to start thawing in the future even if the warming does not increase from its 2020 levels. Only about 3% more sites would start thawing between now and 2050 under the climate change scenario consistent with the Paris Agreement

The Paris Agreement (french: Accord de Paris), often referred to as the Paris Accords or the Paris Climate Accords, is an international treaty on climate change. Adopted in 2015, the agreement covers climate change mitigation, Climate change a ...

goals, RCP2.6, but by 2100, about 1100 more industrial facilities and 3500 to 5200 contaminated sites are expected to start thawing even then. Under the very high emission scenario RCP8.5, 46% of industrial and contaminated sites would start thawing by 2050, and virtually all of them would be affected by the thaw by 2100. Organochlorines and other persistent organic pollutants are of a particular concern, due to their potential to repeatedly reach local communities after their re-release through biomagnification in fish

Fish are aquatic, craniate, gill-bearing animals that lack limbs with digits. Included in this definition are the living hagfish, lampreys, and cartilaginous and bony fish as well as various extinct related groups. Approximately 95% of li ...

. At worst, future generations born in the Arctic would enter life with weakened immune system

The immune system is a network of biological processes that protects an organism from diseases. It detects and responds to a wide variety of pathogens, from viruses to parasitic worms, as well as cancer cells and objects such as wood splinte ...

s due to pollutants accumulating across generations.

A notable example of pollution risks associated with permafrost was the

A notable example of pollution risks associated with permafrost was the 2020 Norilsk oil spill

The Norilsk diesel oil spill was an industrial disaster near Norilsk, Krasnoyarsk Krai, Russia. It began on 29 May 2020 when a fuel storage tank at Norilsk-Taimyr Energy's Thermal Power Plant No. 3 (owned by Nornickel) failed, flooding local rive ...

, caused by the collapse of diesel fuel

Diesel fuel , also called diesel oil, is any liquid fuel specifically designed for use in a diesel engine, a type of internal combustion engine in which fuel ignition takes place without a spark as a result of compression of the inlet air and t ...

storage tank at Norilsk-Taimyr Energy's Thermal Power Plant

A thermal power station is a type of power station in which heat energy is converted to electrical energy. In a steam-generating cycle heat is used to boil water in a large pressure vessel to produce high-pressure steam, which drives a stea ...

No. 3. It spilled 6,000 tonnes of fuel into the land and 15,000 into the water, polluting Ambarnaya

The Ambarnaya (russian: Амбарная, translation=barn girl) is a river in Siberia which flows in a northerly direction into Lake Pyasino. On leaving Lake Pyasino, the waters emerge as the river Pyasina. It shares a common delta with the ri ...

, Daldykan and many smaller rivers on Taimyr Peninsula, even reaching lake Pyasino

Lake Pyasino (russian: Пясино) is a large freshwater lake in Krasnoyarsk Krai, north-central part of Russia. It is located at and has an area of 735 km². Many rivers empty into the lake, including the Ambarnaya. Water from the lake emer ...

, which is a crucial water source in the area. State of emergency

A state of emergency is a situation in which a government is empowered to be able to put through policies that it would normally not be permitted to do, for the safety and protection of its citizens. A government can declare such a state du ...

at the federal level was declared. The event has been described as the second-largest oil spill in modern Russian history.

Another issue associated with permafrost thaw is the release of natural mercury

Mercury commonly refers to:

* Mercury (planet), the nearest planet to the Sun

* Mercury (element), a metallic chemical element with the symbol Hg

* Mercury (mythology), a Roman god

Mercury or The Mercury may also refer to:

Companies

* Merc ...

deposits. An estimated 800,000 tons of mercury are frozen in the permafrost soil. According to observations, around 70% of it is simply taken up by vegetation

Vegetation is an assemblage of plant species and the ground cover they provide. It is a general term, without specific reference to particular taxa, life forms, structure, spatial extent, or any other specific botanical or geographic character ...

after the thaw. However, if the warming continues under RCP8.5, then permafrost emissions of mercury into the atmosphere

An atmosphere () is a layer of gas or layers of gases that envelop a planet, and is held in place by the gravity of the planetary body. A planet retains an atmosphere when the gravity is great and the temperature of the atmosphere is low. A s ...

would match the current global emissions from all human activities by 2200. Mercury-rich soils also pose a much greater threat to humans and the environment if they thaw near rivers. Under RCP8.5, enough mercury will enter the Yukon River

The Yukon River (Gwichʼin language, Gwich'in: ''Ųųg Han'' or ''Yuk Han'', Central Alaskan Yup'ik language, Yup'ik: ''Kuigpak'', Inupiaq language, Inupiaq: ''Kuukpak'', Deg Xinag language, Deg Xinag: ''Yeqin'', Hän language, Hän: ''Tth'echù' ...

basin by 2050 to make its fish unsafe to eat under the EPA

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is an independent executive agency of the United States federal government tasked with environmental protection matters. President Richard Nixon proposed the establishment of EPA on July 9, 1970; it be ...

guidelines. By 2100, mercury concentrations in the river will double. Contrastingly, even if mitigation is limited to RCP4.5 scenario, mercury levels will increase by about 14% by 2100, and will not breach the EPA guidelines even by 2300.

Climate change feedback

In the northern circumpolar region, permafrost contains 1700 billion tons of organic material equaling almost half of all organic material in all soils. This pool was built up over thousands of years and is only slowly degraded under the cold conditions in the Arctic. The amount of carbon sequestered in permafrost is four times the carbon that has been released to the atmosphere due to human activities in modern time. One manifestation of this is yedoma, which is an organic-rich (about 2% carbon by mass)

In the northern circumpolar region, permafrost contains 1700 billion tons of organic material equaling almost half of all organic material in all soils. This pool was built up over thousands of years and is only slowly degraded under the cold conditions in the Arctic. The amount of carbon sequestered in permafrost is four times the carbon that has been released to the atmosphere due to human activities in modern time. One manifestation of this is yedoma, which is an organic-rich (about 2% carbon by mass) Pleistocene

The Pleistocene ( , often referred to as the ''Ice age'') is the geological Epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 2,580,000 to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was fina ...

-age loess

Loess (, ; from german: Löss ) is a clastic, predominantly silt-sized sediment that is formed by the accumulation of wind-blown dust. Ten percent of Earth's land area is covered by loess or similar deposits.

Loess is a periglacial or aeolian ...

permafrost with ice content of 50–90% by volume.

Thawing can also influence the rate of change of soil gas Soil gases (soil atmosphere) are the gases found in the air space between soil components. The spaces between the solid soil particles, if they do not contain water, are filled with air. The primary soil gases are nitrogen, carbon dioxide and oxygen ...

es with the atmosphere.

Impact on global temperatures

Revival of ancient microorganisms

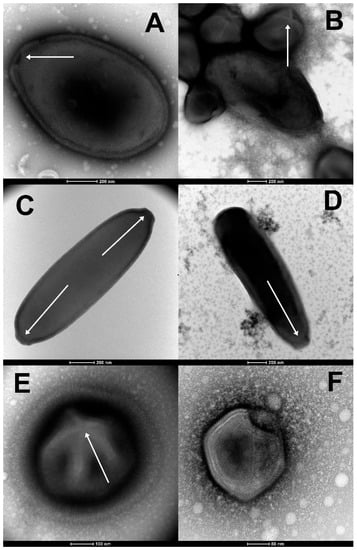

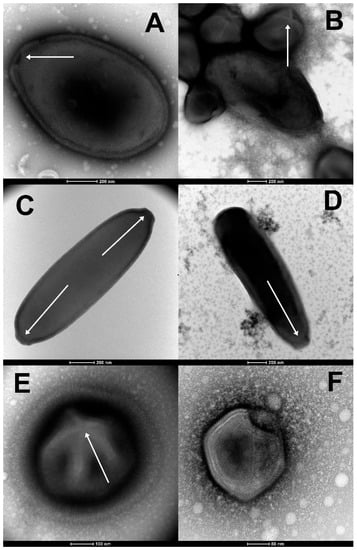

In 1999, researchers were able to extract potentially viable microscopic

In 1999, researchers were able to extract potentially viable microscopic fungi

A fungus ( : fungi or funguses) is any member of the group of eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These organisms are classified as a kingdom, separately from ...

, as well as tomato mosaic virus, from Greenland

Greenland ( kl, Kalaallit Nunaat, ; da, Grønland, ) is an island country in North America that is part of the Kingdom of Denmark. It is located between the Arctic and Atlantic oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Greenland is t ...

ice cores up to 140,000 years old. In 2004, it was estimated that between 1017 and1021 microorganisms, ranging from fungi and bacteria

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were among ...

in addition to virus

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea.

Since Dmitri Ivanovsky's 1 ...

es, were already released every year due to ice melt, often directly into the ocean

The ocean (also the sea or the world ocean) is the body of salt water that covers approximately 70.8% of the surface of Earth and contains 97% of Earth's water. An ocean can also refer to any of the large bodies of water into which the wo ...

. However, only viruses with high abundance, ability to be transported through ice, and ability to resume disease cycles after the thaw would be of any concern. Calicivirus

The ''Caliciviridae'' are a family of "small round structured" viruses, members of Class IV of the Baltimore scheme. Caliciviridae bear resemblance to enlarged picornavirus and was formerly a separate genus within the picornaviridae. They are p ...

es of ''Vesivirus'' genus were hypothesized as the most likely to spread from ancient ice, due to their high abundance and using ocean animals as hosts, where the migratory nature of many species of fish

Fish are aquatic, craniate, gill-bearing animals that lack limbs with digits. Included in this definition are the living hagfish, lampreys, and cartilaginous and bony fish as well as various extinct related groups. Approximately 95% of li ...

and birds

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the laying of hard-shelled eggs, a high metabolic rate, a four-chambered heart, and a strong yet lightweigh ...

could potentially enable a high transmission rate. Caliciviruses are poorly adapted to humans, and the only known infections were of marine biologist

Marine biology is the scientific study of the biology of marine life, organisms in the sea. Given that in biology many scientific classification, phyla, family (biology), families and genera have some species that live in the sea and others th ...

s who worked closely with infected seals. However, Enteroviruses (a group which includes poliovirus

A poliovirus, the causative agent of polio (also known as poliomyelitis), is a serotype of the species ''Enterovirus C'', in the family of ''Picornaviridae''. There are three poliovirus serotypes: types 1, 2, and 3.

Poliovirus is composed of an ...

es, echovirus

Echovirus is a polyphyletic group of viruses associated with enteric disease in humans. The name is derived from "enteric cytopathic human orphan virus". These viruses were originally not associated with disease, but many have since been identifie ...

es and Coxsackie virus

Coxsackieviruses are a few related enteroviruses that belong to the ''Picornaviridae'' family of nonenveloped, linear, positive-sense single-stranded RNA viruses, as well as its genus ''Enterovirus'', which also includes poliovirus and echoviru ...

es) and even influenza A were also considered less likely but still plausible candidates. On the other hand, Johan Hultin

Johan Hultin (October 7, 1924 – January 22, 2022) was a Swedish-born American pathologist known for recovering tissues containing traces of the 1918 influenza virus that killed millions worldwide.

Life and career

Hultin was born into a wealthy ...

made multiple attempts during the 20th century to culture 1918 influenza virus

This year is noted for the end of the World War I, First World War, on the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month, as well as for the Spanish flu pandemic that killed 50–100 million people worldwide.

Events

Belo ...

he found in the frozen corpses of pandemic victims at Brevig Mission

Brevig Mission ( ik, Sitaisaq or ; russian: Бревиг-Мишен) is a city in Nome Census Area, Alaska. The population was 388 at the 2010 census, up from 276 in 2000. It is named for the Norwegian Lutheran pastor Tollef L. Brevig, who served ...

in Alaska

Alaska ( ; russian: Аляска, Alyaska; ale, Alax̂sxax̂; ; ems, Alas'kaaq; Yup'ik: ''Alaskaq''; tli, Anáaski) is a state located in the Western United States on the northwest extremity of North America. A semi-exclave of the U.S., ...

, yet all of them failed, suggesting that the influenza virus is incapable of surviving the thaw.

In 2014, a completely unknown plant virus was revived from a frozen caribou

Reindeer (in North American English, known as caribou if wild and ''reindeer'' if domesticated) are deer in the genus ''Rangifer''. For the last few decades, reindeer were assigned to one species, ''Rangifer tarandus'', with about 10 subspe ...

feces

Feces ( or faeces), known colloquially and in slang as poo and poop, are the solid or semi-solid remains of food that was not digested in the small intestine, and has been broken down by bacteria in the large intestine. Feces contain a relati ...

deposit which was only 700 years old. It was named "ancient caribou feces associated virus" (aCFV) by the researchers, and it was able to successfully replicate in Nicotiana benthamiana, a common model species for plant pathogens. aCFV couldn't cause more than an asymptomatic

In medicine, any disease is classified asymptomatic if a patient tests as carrier for a disease or infection but experiences no symptoms. Whenever a medical condition fails to show noticeable symptoms after a diagnosis it might be considered asy ...

infection, which either suggests large genetic distance between it and modern plants, or that ''N. benthamiana'' was simply a suboptimal host for it. Also in 2014, two ~30,000 years old giant virus species, Pithovirus sibericum

''Pithovirus'', first described in a 2014 paper, is a genus of giant virus known from two species, ''Pithovirus sibericum'', which infects amoebas and ''Pithovirus massiliensis''. It is a base pair, double-stranded DNA virus, and is a member of ...

and Mollivirus sibericum, were discovered in the Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part of ...

n permafrost and they retained their infectivity. Like the other giant viruses with large genome

In the fields of molecular biology and genetics, a genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding ge ...

s, they are larger in size than most bacteria and pose no risk to humans, as they infect other microorganisms like Acanthamoeba, a genus of amoebas. In 2023, the same team of French researchers managed to revive 8 more ancient amoeba-infecting viral species, four of which were from the pandoravirus

''Pandoravirus'' is a genus of giant virus, first discovered in 2013. It is the second largest in physical size of any known viral genus. Pandoraviruses have double stranded DNA genomes, with the largest genome size (2.5 million base pairs) of ...

, cedratvirus (sometimes classified as a subgroup of pithovirus), megavirus

Megavirus is a viral genus containing a single identified species named ''Megavirus chilensis'', phylogenetically related to Acanthamoeba polyphaga Mimivirus (APMV). In colloquial speech, Megavirus chilensis is more commonly referred to as jus ...

and pacmanvirus (part of Asfarviridae) families, which weren't previously revived from the permafrost. In addition, five more species from these families were found in already thawed permafrost, with no way to tell their age. The oldest revived virus was a 48,500-year-old ''Pandoravirus yedoma''.

Scientists are split on whether revived microorganisms from the permafrost can pose a significant threat to humans. Jean-Michel Claverie, who led the only successful attempts to revive such "zombie viruses", believes that the

Scientists are split on whether revived microorganisms from the permafrost can pose a significant threat to humans. Jean-Michel Claverie, who led the only successful attempts to revive such "zombie viruses", believes that the public health

Public health is "the science and art of preventing disease, prolonging life and promoting health through the organized efforts and informed choices of society, organizations, public and private, communities and individuals". Analyzing the det ...

threat from them is underestimated, and that while his research focused on amoeba-infecting viruses, this decision was in part motivated by the desire to avoid viral spillover as well as convenience, and "one can reasonably infer" other viral species would also remain infectious. On the other hand, University of British Columbia

The University of British Columbia (UBC) is a public university, public research university with campuses near Vancouver and in Kelowna, British Columbia. Established in 1908, it is British Columbia's oldest university. The university ranks a ...

virologist

Virology is the scientific study of biological viruses. It is a subfield of microbiology that focuses on their detection, structure, classification and evolution, their methods of infection and exploitation of host cells for reproduction, their ...

Curtis Suttle argued that "people already inhale thousands of viruses every day, and swallow billions whenever they swim in the sea". In his view, the odds of a frozen virus replicating and then circulating to a sufficient extent to threaten humans "stretches scientific rationality to the breaking point". While there have already been outbreaks of anthrax

Anthrax is an infection caused by the bacterium ''Bacillus anthracis''. It can occur in four forms: skin, lungs, intestinal, and injection. Symptom onset occurs between one day and more than two months after the infection is contracted. The sk ...

from formerly frozen soil, such as the 2016 Yamal Peninsula outbreak, anthrax is a non-contagious pathogen which has been known for its ability to hibernate in the soil since the Middle Ages, and does not require the cold to do so. Some scientists have argued that Hultin's inability to revive thawed influenza virus, as well as other researchers' failure to revive pneumonia

Pneumonia is an inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of productive or dry cough, chest pain, fever, and difficulty breathing. The severity ...

-causing bacteria or smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

viruses show that pathogens adapted to warm-blooded hosts cannot survive being frozen for a prolonged period of time. However, many of the amoeba-infecting viruses revived in Claverie's 2023 research were taken from a ~27,000-year-old site with "a large amount of mammoth

A mammoth is any species of the extinct elephantid genus ''Mammuthus'', one of the many genera that make up the order of trunked mammals called proboscideans. The various species of mammoth were commonly equipped with long, curved tusks and, ...

wool

Wool is the textile fibre obtained from sheep and other mammals, especially goats, rabbits, and camelids. The term may also refer to inorganic materials, such as mineral wool and glass wool, that have properties similar to animal wool.

As ...

", and one species, ''Pacmanvirus lupus'', was found in the intestine

The gastrointestinal tract (GI tract, digestive tract, alimentary canal) is the tract or passageway of the digestive system that leads from the mouth to the anus. The GI tract contains all the major organs of the digestive system, in humans ...

of an equally old Siberian wolf carcass.

There is some agreement that revived bacteria would be less dangerous than the revived viruses, since they would still be affected by broad-spectrum antibiotics and would not require wholly new treatments. However, they would not be completely vulnerable either, due to the discovery of ancient antibiotic resistance

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) occurs when microbes evolve mechanisms that protect them from the effects of antimicrobials. All classes of microbes can evolve resistance. Fungi evolve antifungal resistance. Viruses evolve antiviral resistance. ...

genes in permafrost samples. Antibiotics to which permafrost bacteria have displayed at least some resistance include chloramphenicol

Chloramphenicol is an antibiotic useful for the treatment of a number of bacterial infections. This includes use as an eye ointment to treat conjunctivitis. By mouth or by injection into a vein, it is used to treat meningitis, plague, cholera, a ...

, streptomycin, kanamycin, gentamicin

Gentamicin is an antibiotic used to treat several types of bacterial infections. This may include bone infections, endocarditis, pelvic inflammatory disease, meningitis, pneumonia, urinary tract infections, and sepsis among others. It is not e ...

, tetracycline