Pearl Harbor bombing on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise

Starting in December 1937, events such as the Japanese attack on USS ''Panay'', the Allison incident, and the

Starting in December 1937, events such as the Japanese attack on USS ''Panay'', the Allison incident, and the

* 1st Group (targets: battleships and aircraft carriers)

** 49

* 1st Group (targets: battleships and aircraft carriers)

** 49  In the first-wave attack, about eight of the forty-nine 800kg (1760lb) armor-piercing bombs dropped hit their intended battleship targets. At least two of those bombs broke up on impact, another detonated before penetrating an unarmored deck, and one was a dud. Thirteen of the forty torpedoes hit battleships, and four torpedoes hit other ships. Men aboard US ships awoke to the sounds of alarms, bombs exploding, and gunfire, prompting bleary-eyed men to dress as they ran to

In the first-wave attack, about eight of the forty-nine 800kg (1760lb) armor-piercing bombs dropped hit their intended battleship targets. At least two of those bombs broke up on impact, another detonated before penetrating an unarmored deck, and one was a dud. Thirteen of the forty torpedoes hit battleships, and four torpedoes hit other ships. Men aboard US ships awoke to the sounds of alarms, bombs exploding, and gunfire, prompting bleary-eyed men to dress as they ran to

Already damaged by a torpedo and on fire amidships, ''Nevada'' attempted to exit the harbor. She was targeted by many Japanese bombers as she got under way and sustained more hits from bombs, which started further fires. She was deliberately beached to avoid blocking the harbor entrance. was hit by two bombs and two torpedoes. The crew might have kept her afloat, but were ordered to abandon ship just as they were raising power for the pumps. Burning oil from ''Arizona'' and drifted down on her and probably made the situation look worse than it was. The disarmed

Already damaged by a torpedo and on fire amidships, ''Nevada'' attempted to exit the harbor. She was targeted by many Japanese bombers as she got under way and sustained more hits from bombs, which started further fires. She was deliberately beached to avoid blocking the harbor entrance. was hit by two bombs and two torpedoes. The crew might have kept her afloat, but were ordered to abandon ship just as they were raising power for the pumps. Burning oil from ''Arizona'' and drifted down on her and probably made the situation look worse than it was. The disarmed

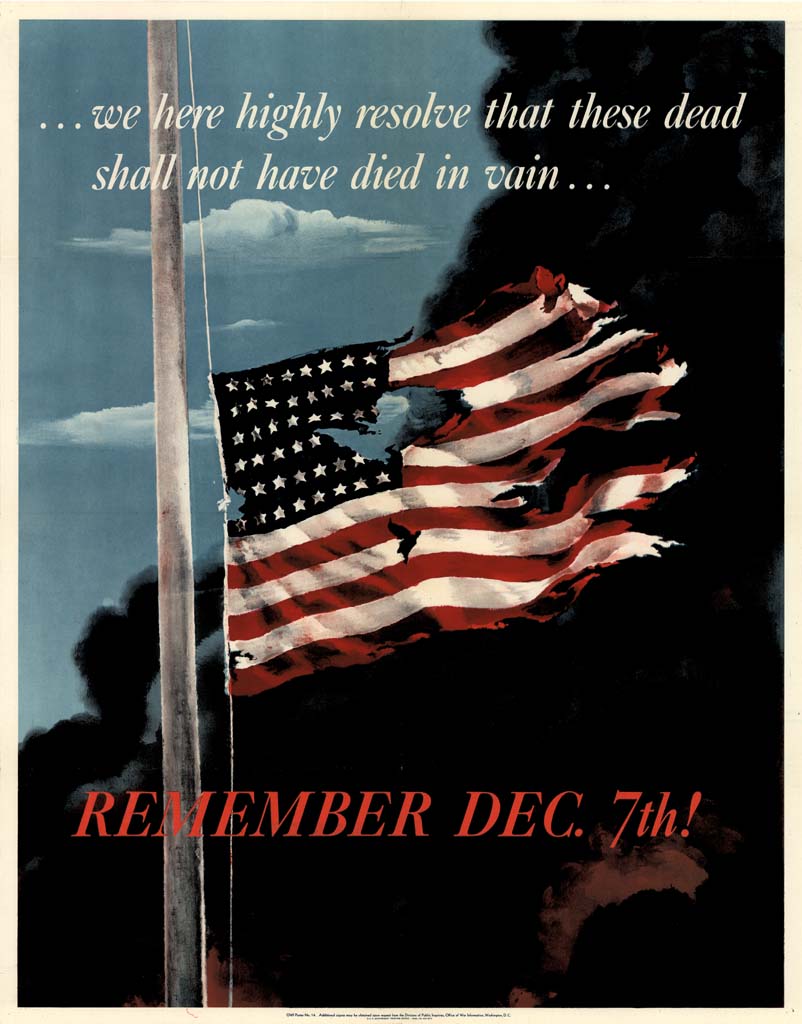

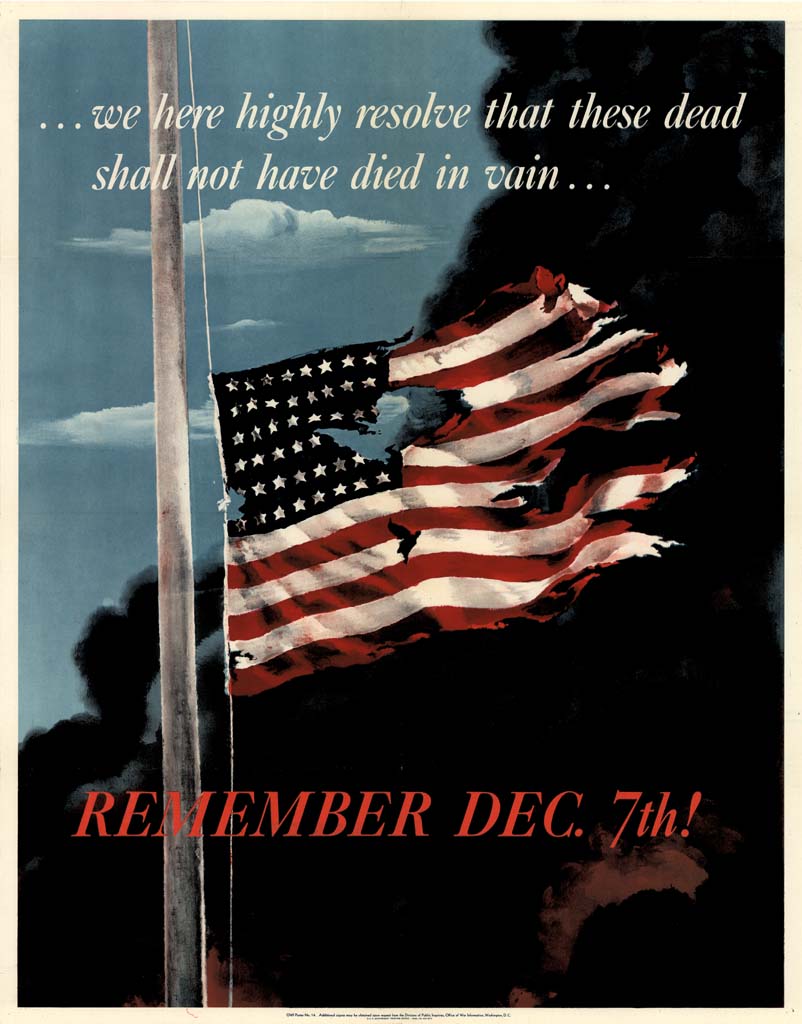

Throughout the war, Pearl Harbor was frequently used in

Throughout the war, Pearl Harbor was frequently used in

Ever since the Japanese attack, there has been debate as to how and why the United States had been caught unaware, and how much and when American officials knew of Japanese plans and related topics. As early as 1924, Chief of US Air Service

Ever since the Japanese attack, there has been debate as to how and why the United States had been caught unaware, and how much and when American officials knew of Japanese plans and related topics. As early as 1924, Chief of US Air Service

Navy History Heritage Command Official Overview

History.com Account With Video

* ttps://web.archive.org/web/20100217050639/http://libweb.hawaii.edu/digicoll/hwrd/HWRD_html/HWRD_welcome.htm Hawaii War Records Depository Archives & Manuscripts Department, University of Hawaii at Manoa Library

7 December 1941, The Air Force Story

The "Magic" Background

(PDFs or readable online)

The Congressional investigation

* *

in

'' Official US Army history of Pearl Harbor by the

War comes to Hawaii

''Honolulu Star-Bulletin'', Monday, September 13, 1999

Video of first Newsreel from December 23, 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor

''Pearl Harbour'' – British Movietone News, 1942

Historic footage of Pearl Harbor during and immediately following attack on December 7, 1941

WW2DB: US Navy Report of Japanese Raid on Pearl Harbor

Second World War – USA Declaration of War on Japan

{{DEFAULTSORT:Pearl Harbor 1941 in Hawaii 1941 in the United States Conflicts in 1941 December 1941 events Explosions in 1941 Pearl Harbor Airstrikes conducted by Japan World War II aerial operations and battles of the Pacific theatre Attacks on military installations in the 1940s

military strike

In the military of the United States, strikes and raids are a group of military operations that, alongside quite a number of others, come under the formal umbrella of military operations other than war (MOOTW). What the definition of a military s ...

by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service

The was the Naval aviation, air arm of the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN). The organization was responsible for the operation of naval aircraft and the conduct of aerial warfare in the Pacific War.

The Japanese military acquired their first air ...

upon the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

against the naval base

A naval base, navy base, or military port is a military base, where warships and naval ships are docked when they have no mission at sea or need to restock. Ships may also undergo repairs. Some naval bases are temporary homes to aircraft that us ...

at Pearl Harbor

Pearl Harbor is an American lagoon harbor on the island of Oahu, Hawaii, west of Honolulu. It was often visited by the Naval fleet of the United States, before it was acquired from the Hawaiian Kingdom by the U.S. with the signing of the Re ...

in Honolulu

Honolulu (; ) is the capital and largest city of the U.S. state of Hawaii, which is in the Pacific Ocean. It is an unincorporated county seat of the consolidated City and County of Honolulu, situated along the southeast coast of the island ...

, Territory of Hawaii

The Territory of Hawaii or Hawaii Territory ( Hawaiian: ''Panalāʻau o Hawaiʻi'') was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from April 30, 1900, until August 21, 1959, when most of its territory, excluding ...

, just before 8:00a.m. (local time) on Sunday, December 7, 1941. The United States was a neutral country

A neutral country is a state that is neutral towards belligerents in a specific war or holds itself as permanently neutral in all future conflicts (including avoiding entering into military alliances such as NATO, CSTO or the SCO). As a type of ...

at the time; the attack led to its formal entry into World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

the next day. The Japanese military leadership referred to the attack as the Hawaii Operation and Operation AI, and as Operation Z during its planning.

Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

intended the attack as a preventive action. Its aim was to prevent the United States Pacific Fleet

The United States Pacific Fleet (USPACFLT) is a theater-level component command of the United States Navy, located in the Pacific Ocean. It provides naval forces to the Indo-Pacific Command. Fleet headquarters is at Joint Base Pearl Harbor� ...

from interfering with its planned military actions in Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia, also spelled South East Asia and South-East Asia, and also known as Southeastern Asia, South-eastern Asia or SEA, is the geographical United Nations geoscheme for Asia#South-eastern Asia, south-eastern region of Asia, consistin ...

against overseas territories of the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

, the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

, and those of the United States. Over the course of seven hours there were coordinated Japanese attacks on the US-held Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

, Guam

Guam (; ch, Guåhan ) is an organized, unincorporated territory of the United States in the Micronesia subregion of the western Pacific Ocean. It is the westernmost point and territory of the United States (reckoned from the geographic cent ...

, and Wake Island

Wake Island ( mh, Ānen Kio, translation=island of the kio flower; also known as Wake Atoll) is a coral atoll in the western Pacific Ocean in the northeastern area of the Micronesia subregion, east of Guam, west of Honolulu, southeast of To ...

and on the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

in Malaya, Singapore

Singapore (), officially the Republic of Singapore, is a sovereign island country and city-state in maritime Southeast Asia. It lies about one degree of latitude () north of the equator, off the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, borde ...

, and Hong Kong

Hong Kong ( (US) or (UK); , ), officially the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China ( abbr. Hong Kong SAR or HKSAR), is a city and special administrative region of China on the eastern Pearl River Delt ...

.

The attack commenced at 7:48a.m. Hawaiian Time

Hawaiian may refer to:

* Native Hawaiians, the current term for the indigenous people of the Hawaiian Islands or their descendants

* Hawaii state residents, regardless of ancestry (only used outside of Hawaii)

* Hawaiian language

Historic uses

* ...

(6:18p.m. GMT). The base was attacked by 353 Imperial Japanese aircraft (including fighters, level and dive bombers, and torpedo bomber

A torpedo bomber is a military aircraft designed primarily to attack ships with aerial torpedoes. Torpedo bombers came into existence just before the First World War almost as soon as aircraft were built that were capable of carrying the weight ...

s) in two waves, launched from six aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and facilities for carrying, arming, deploying, and recovering aircraft. Typically, it is the capital ship of a fleet, as it allows a ...

s. Of the eight US Navy battleships

A battleship is a large armored warship with a main battery consisting of large caliber guns. It dominated naval warfare in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The term ''battleship'' came into use in the late 1880s to describe a type of ...

present, all were damaged, with four sunk. All but were later raised, and six were returned to service and went on to fight in the war. The Japanese also sank or damaged three cruiser

A cruiser is a type of warship. Modern cruisers are generally the largest ships in a fleet after aircraft carriers and amphibious assault ships, and can usually perform several roles.

The term "cruiser", which has been in use for several hu ...

s, three destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, manoeuvrable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy or battle group and defend them against powerful short range attackers. They were originally developed in ...

s, an anti-aircraft training ship, and one minelayer

A minelayer is any warship, submarine or military aircraft deploying explosive mines. Since World War I the term "minelayer" refers specifically to a naval ship used for deploying naval mines. "Mine planting" was the term for installing controll ...

. More than 180 US aircraft were destroyed. 2,403 Americans were killed and 1,178 others were wounded. Important base installations such as the power station, dry dock

A dry dock (sometimes drydock or dry-dock) is a narrow basin or vessel that can be flooded to allow a load to be floated in, then drained to allow that load to come to rest on a dry platform. Dry docks are used for the construction, maintenance, ...

, shipyard

A shipyard, also called a dockyard or boatyard, is a place where ships are built and repaired. These can be yachts, military vessels, cruise liners or other cargo or passenger ships. Dockyards are sometimes more associated with maintenance a ...

, maintenance, and fuel and torpedo storage facilities, as well as the submarine piers and headquarters building (also home of the intelligence section) were not attacked. Japanese losses were light: 29 aircraft and five midget submarine

A midget submarine (also called a mini submarine) is any submarine under 150 tons, typically operated by a crew of one or two but sometimes up to six or nine, with little or no on-board living accommodation. They normally work with mother ships, ...

s lost, and 64 servicemen killed. Kazuo Sakamaki

was a Japanese naval officer who became the first prisoner of war of World War II to be captured by U.S. forces, and the second to be captured by Americans.

Early life and education

Sakamaki was born in what is now part of the city of Awa, T ...

, the commanding officer of one of the submarines, was captured.

Japan announced declarations of war on the United States and the British Empire later that day (December 8 in Tokyo), but the declarations were not delivered until the following day. The British government declared war on Japan immediately after learning that their territory had also been attacked, while the following day (December 8) the United States Congress declared war

A declaration of war is a formal act by which one state announces existing or impending war activity against another. The declaration is a performative speech act (or the signing of a document) by an authorized party of a national government, i ...

on Japan. On December 11, though they had no formal obligation to do so under the Tripartite Pact

The Tripartite Pact, also known as the Berlin Pact, was an agreement between Germany, Italy, and Japan signed in Berlin on 27 September 1940 by, respectively, Joachim von Ribbentrop, Galeazzo Ciano and Saburō Kurusu. It was a defensive military ...

with Japan, Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

and Italy each declared war on the US, which responded with a declaration of war against Germany and Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

. There were numerous historical precedents for the unannounced military action by Japan, but the lack of any formal warning (required by part III of the Hague Convention of 1907

The Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907 are a series of international treaties and declarations negotiated at two international peace conferences at The Hague in the Netherlands. Along with the Geneva Conventions, the Hague Conventions were amo ...

), particularly while peace negotiations were still apparently ongoing, led President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

to proclaim December 7, 1941, "a date which will live in infamy

The "Day of Infamy" speech, sometimes referred to as just ''"The Infamy speech"'', was delivered by Franklin D. Roosevelt, the 32nd president of the United States, to a joint session of Congress on December 8, 1941. The previous day, the Empi ...

". Because the attack happened without a declaration of war and without explicit warning, the attack on Pearl Harbor was later judged in the Tokyo Trials

The International Military Tribunal for the Far East (IMTFE), also known as the Tokyo Trial or the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal, was a military trial convened on April 29, 1946 to try leaders of the Empire of Japan for crimes against peace, conv ...

to be a war crime.

Background

Diplomacy

War between Japan and the United States had been a possibility that each nation had been aware of, and planned for, since the 1920s. Japan had been wary of American territorial and military expansion in the Pacific and Asia since the late 1890s, followed by the annexation of islands, such asHawaii

Hawaii ( ; haw, Hawaii or ) is a state in the Western United States, located in the Pacific Ocean about from the U.S. mainland. It is the only U.S. state outside North America, the only state that is an archipelago, and the only stat ...

and the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

, which they felt were close to or within their sphere of influence

In the field of international relations, a sphere of influence (SOI) is a spatial region or concept division over which a state or organization has a level of cultural, economic, military or political exclusivity.

While there may be a formal al ...

.

Although Japan had begun to take a hostile policy against the United States after the rejection of the Racial Equality Proposal

The was an amendment to the Treaty of Versailles that was considered at the 1919 Paris Peace Conference. Proposed by Japan, it was never intended to have any universal implications, but one was attached to it anyway, which caused its controversy. ...

, the relationship between the two countries was cordial enough that they remained trading partners. Tensions did not seriously grow until Japan's invasion of Manchuria in 1931. Over the next decade, Japan expanded into China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

, leading to the Second Sino-Japanese War

The Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) or War of Resistance (Chinese term) was a military conflict that was primarily waged between the Republic of China and the Empire of Japan. The war made up the Chinese theater of the wider Pacific Th ...

in 1937. Japan spent considerable effort trying to isolate China and endeavored to secure enough independent resources to attain victory on the mainland. The " Southern Operation" was designed to assist these efforts.

Starting in December 1937, events such as the Japanese attack on USS ''Panay'', the Allison incident, and the

Starting in December 1937, events such as the Japanese attack on USS ''Panay'', the Allison incident, and the Nanking Massacre

The Nanjing Massacre (, ja, 南京大虐殺, Nankin Daigyakusatsu) or the Rape of Nanjing (formerly romanized as ''Nanking'') was the mass murder of Chinese civilians in Nanjing, the capital of the Republic of China, immediately after the Ba ...

swung Western public opinion sharply against Japan. The US unsuccessfully proposed a joint action with the British to blockade Japan. In 1938, following an appeal by President Roosevelt, US companies stopped providing Japan with implements of war.

In 1940 Japan invaded French Indochina, attempting to stymie the flow of supplies reaching China. The United States halted shipments of airplanes, parts, machine tool

A machine tool is a machine for handling or machining metal or other rigid materials, usually by cutting, boring, grinding, shearing, or other forms of deformations. Machine tools employ some sort of tool that does the cutting or shaping. All m ...

s, and aviation gasoline

Avgas (aviation gasoline, also known as aviation spirit in the UK) is an aviation fuel used in aircraft with spark-ignited internal combustion engines. ''Avgas'' is distinguished from conventional gasoline (petrol) used in motor vehicles, whi ...

to Japan, which the latter perceived as an unfriendly act. The United States did not stop oil exports, however, partly because of the prevailing sentiment in Washington that given Japanese dependence on American oil, such an action was likely to be considered an extreme provocation.

In mid-1940 President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

moved the Pacific Fleet from San Diego

San Diego ( , ; ) is a city on the Pacific Ocean coast of Southern California located immediately adjacent to the Mexico–United States border. With a 2020 population of 1,386,932, it is the List of United States cities by population, eigh ...

to Hawaii. He also ordered a military buildup in the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

, taking both actions in the hope of discouraging Japanese aggression in the Far East. Because the Japanese high command was (mistakenly) certain any attack on the United Kingdom's Southeast Asian colonies, including Singapore, would bring the US into the war, a devastating preventive strike appeared to be the only way to prevent American naval interference. An invasion of the Philippines was also considered necessary by Japanese war planners. The US War Plan Orange

War Plan Orange (commonly known as Plan Orange or just Orange) is a series of United States Joint Chiefs of Staff, Joint Army and Navy Board war plans for dealing with a possible war with Empire of Japan, Japan during the interwar years, years bet ...

had envisioned defending the Philippines with an elite force of 40,000 men; this option was never implemented due to opposition from Douglas MacArthur

Douglas MacArthur (26 January 18805 April 1964) was an American military leader who served as General of the Army for the United States, as well as a field marshal to the Philippine Army. He had served with distinction in World War I, was C ...

, who felt he would need a force ten times that size. By 1941, US planners expected to abandon the Philippines at the outbreak of war. Late that year, Admiral Thomas C. Hart

Thomas Charles Hart (June 12, 1877July 4, 1971) was an admiral in the United States Navy, whose service extended from the Spanish–American War through World War II. Following his retirement from the navy, he served briefly as a United States Se ...

, commander of the Asiatic Fleet

The United States Asiatic Fleet was a fleet of the United States Navy during much of the first half of the 20th century. Before World War II, the fleet patrolled the Philippine Islands. Much of the fleet was destroyed by the Japanese by Februar ...

, was given orders to that effect.

The US finally ceased oil exports to Japan in July 1941, following the seizure of French Indochina after the Fall of France

The Battle of France (french: bataille de France) (10 May – 25 June 1940), also known as the Western Campaign ('), the French Campaign (german: Frankreichfeldzug, ) and the Fall of France, was the German invasion of France during the Second World ...

, in part because of new American restrictions on domestic oil consumption. Because of this decision, Japan proceeded with plans to take the oil-rich Dutch East Indies

The Dutch East Indies, also known as the Netherlands East Indies ( nl, Nederlands(ch)-Indië; ), was a Dutch colony consisting of what is now Indonesia. It was formed from the nationalised trading posts of the Dutch East India Company, which ...

. On August 17, Roosevelt warned Japan that America was prepared to take opposing steps if "neighboring countries" were attacked. The Japanese were faced with a dilemma: either withdraw from China and lose face or seize new sources of raw materials in the resource-rich European colonies of Southeast Asia.

Japan and the US engaged in negotiations during 1941, attempting to improve relations. In the course of these negotiations, Japan offered to withdraw from most of China and Indochina after making peace with the Nationalist government. It also proposed to adopt an independent interpretation of the Tripartite Pact

The Tripartite Pact, also known as the Berlin Pact, was an agreement between Germany, Italy, and Japan signed in Berlin on 27 September 1940 by, respectively, Joachim von Ribbentrop, Galeazzo Ciano and Saburō Kurusu. It was a defensive military ...

and to refrain from trade discrimination, provided all other nations reciprocated. Washington rejected these proposals. Japanese Prime Minister Konoye then offered to meet with Roosevelt, but Roosevelt insisted on reaching an agreement before any meeting. The US ambassador to Japan repeatedly urged Roosevelt to accept the meeting, warning that it was the only way to preserve the conciliatory Konoye government and peace in the Pacific. However, his recommendation was not acted upon. The Konoye government collapsed the following month when the Japanese military rejected a withdrawal of all troops from China.

Japan's final proposal, delivered on November 20, offered to withdraw from southern Indochina and to refrain from attacks in Southeast Asia, so long as the United States, United Kingdom, and Netherlands supplied of aviation fuel, lifted their sanctions against Japan, and ceased aid to China. The American counter-proposal of November 26 (November 27 in Japan), the Hull note

The Hull note, officially the Outline of Proposed Basis for Agreement Between the United States and Japan, was the final proposal delivered to the Empire of Japan by the United States of America before the attack on Pearl Harbor (December 7, 1 ...

, required Japan completely evacuate China without conditions and conclude non-aggression pacts with Pacific powers. On November 26 in Japan, the day before the note's delivery, the Japanese task force left port for Pearl Harbor

Pearl Harbor is an American lagoon harbor on the island of Oahu, Hawaii, west of Honolulu. It was often visited by the Naval fleet of the United States, before it was acquired from the Hawaiian Kingdom by the U.S. with the signing of the Re ...

.

The Japanese intended the attack as a preventive action to keep the United States Pacific Fleet

The United States Pacific Fleet (USPACFLT) is a theater-level component command of the United States Navy, located in the Pacific Ocean. It provides naval forces to the Indo-Pacific Command. Fleet headquarters is at Joint Base Pearl Harbor� ...

from interfering with its planned military actions in Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia, also spelled South East Asia and South-East Asia, and also known as Southeastern Asia, South-eastern Asia or SEA, is the geographical United Nations geoscheme for Asia#South-eastern Asia, south-eastern region of Asia, consistin ...

against overseas territories of the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

, the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

, and the United States. Over the course of seven hours there were coordinated Japanese attacks on the US-held Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

, Guam

Guam (; ch, Guåhan ) is an organized, unincorporated territory of the United States in the Micronesia subregion of the western Pacific Ocean. It is the westernmost point and territory of the United States (reckoned from the geographic cent ...

, and Wake Island

Wake Island ( mh, Ānen Kio, translation=island of the kio flower; also known as Wake Atoll) is a coral atoll in the western Pacific Ocean in the northeastern area of the Micronesia subregion, east of Guam, west of Honolulu, southeast of To ...

and on the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

in Malaya, Singapore

Singapore (), officially the Republic of Singapore, is a sovereign island country and city-state in maritime Southeast Asia. It lies about one degree of latitude () north of the equator, off the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, borde ...

, and Hong Kong

Hong Kong ( (US) or (UK); , ), officially the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China ( abbr. Hong Kong SAR or HKSAR), is a city and special administrative region of China on the eastern Pearl River Delt ...

. Additionally, from the Japanese viewpoint, it was seen as a preemptive strike

A preemptive war is a war that is commenced in an attempt to repel or defeat a perceived imminent offensive or invasion, or to gain a strategic advantage in an impending (allegedly unavoidable) war ''shortly before'' that attack materializes. It ...

"before the oil gauge ran empty."

Military planning

Preliminary planning for an attack on Pearl Harbor to protect the move into the "Southern Resource Area" (the Japanese term for the Dutch East Indies and Southeast Asia generally) had begun very early in 1941 under the auspices of AdmiralIsoroku Yamamoto

was a Marshal Admiral of the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) and the commander-in-chief of the Combined Fleet during World War II until he was killed.

Yamamoto held several important posts in the IJN, and undertook many of its changes and reor ...

, then commanding Japan's Combined Fleet

The was the main sea-going component of the Imperial Japanese Navy. Until 1933, the Combined Fleet was not a permanent organization, but a temporary force formed for the duration of a conflict or major naval maneuvers from various units norm ...

. He won assent to formal planning and training for an attack from the Imperial Japanese Navy General Staff

The was the highest organ within the Imperial Japanese Navy. In charge of planning and operations, it was headed by an Admiral headquartered in Tokyo.

History

Created in 1893, the Navy General Staff took over operational (as opposed to adminis ...

only after much contention with Naval Headquarters, including a threat to resign his command. Full-scale planning was underway by early spring 1941, primarily by Rear Admiral Ryūnosuke Kusaka

, was an admiral in the Imperial Japanese Navy during World War II who served as Chief of Staff of the Combined Fleet. Fellow Admiral Jinichi Kusaka was his cousin. Kusaka was also the 4th Headmaster of ''Ittō Shōden Mutō-ryū Kenjutsu'', a ...

, with assistance from Captain Minoru Genda

was a Japanese military aviator and politician. He is best known for helping to plan the attack on Pearl Harbor. He was also the third Chief of Staff of the Japan Air Self-Defense Force.

Early life

Minoru Genda was the second son of a farmer ...

and Yamamoto's Deputy Chief of Staff, Captain Kameto Kuroshima. The planners studied the 1940 British air attack on the Italian fleet at Taranto

Taranto (, also ; ; nap, label= Tarantino, Tarde; Latin: Tarentum; Old Italian: ''Tarento''; Ancient Greek: Τάρᾱς) is a coastal city in Apulia, Southern Italy. It is the capital of the Province of Taranto, serving as an important com ...

intensively.

Over the next several months, pilots were trained, equipment was adapted, and intelligence was collected. Despite these preparations, Emperor Hirohito

Emperor , commonly known in English-speaking countries by his personal name , was the 124th emperor of Japan, ruling from 25 December 1926 until his death in 1989. Hirohito and his wife, Empress Kōjun, had two sons and five daughters; he was ...

did not approve the attack plan until November 5, after the third of four Imperial Conferences called to consider the matter. Final authorization was not given by the emperor until December 1, after a majority of Japanese leaders advised him the "Hull Note

The Hull note, officially the Outline of Proposed Basis for Agreement Between the United States and Japan, was the final proposal delivered to the Empire of Japan by the United States of America before the attack on Pearl Harbor (December 7, 1 ...

" would "destroy the fruits of the China incident, endanger Manchukuo and undermine Japanese control of Korea".

By late 1941, many observers believed that hostilities between the US and Japan were imminent. A Gallup poll

Gallup, Inc. is an American analytics and advisory company based in Washington, D.C. Founded by George Gallup in 1935, the company became known for its public opinion polls conducted worldwide. Starting in the 1980s, Gallup transitioned its bu ...

just before the attack on Pearl Harbor found that 52% of Americans expected war with Japan, 27% did not, and 21% had no opinion. While US Pacific bases and facilities had been placed on alert on many occasions, US officials doubted Pearl Harbor would be the first target; instead, they expected the Philippines would be attacked first. This presumption was due to the threat that the air bases throughout the country and the naval base at Manila posed to sea lanes, as well as to the shipment of supplies to Japan from territory to the south. They also incorrectly believed that Japan was not capable of mounting more than one major naval operation at a time.

Objectives

The Japanese attack had several major aims. First, it intended to destroy important American fleet units, thereby preventing the Pacific Fleet from interfering with the Japanese conquest of the Dutch East Indies and Malaya and enabling Japan to conquer Southeast Asia without interference. Second, it was hoped to buy time for Japan to consolidate its position and increase its naval strength before shipbuilding authorized by the 1940 Vinson-Walsh Act erased any chance of victory.. Third, to deliver a blow to America's ability to mobilize its forces in the Pacific, battleships were chosen as the main targets, since they were the prestige ships of any navy at the time. Finally, it was hoped that the attack would undermine American morale such that the US government would drop its demands contrary to Japanese interests and would seek a compromise peace with Japan. Striking the Pacific Fleet at anchor in Pearl Harbor carried two distinct disadvantages: the targeted ships would be in very shallow water, so it would be relatively easy to salvage and possibly repair them, and most of the crews would survive the attack since many would be onshore leave

Shore leave is the leave that professional sailors get to spend on dry land. It is also known as "liberty" within the United States Navy, United States Coast Guard, and Marine Corps.

During the Age of Sail, shore leave was often abused by the ...

or would be rescued from the harbor. A further important disadvantage was the absence from Pearl Harbor of all three of the US Pacific Fleet's aircraft carriers (, , and ). Imperial Japanese Navy

The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN; Kyūjitai: Shinjitai: ' 'Navy of the Greater Japanese Empire', or ''Nippon Kaigun'', 'Japanese Navy') was the navy of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945, when it was dissolved following Japan's surrender ...

(IJN) top command was attached to Admiral Mahan's "decisive battle

A decisive victory is a military victory in battle that definitively resolves the objective being fought over, ending one stage of the conflict and beginning another stage. Until a decisive victory is achieved, conflict over the competing objecti ...

" doctrine, especially that of destroying the maximum number of battleships. Despite these concerns, Yamamoto decided to press ahead.

Japanese confidence in their ability to win a short war also meant other targets in the harbor, especially the navy yard, oil tank farms, and submarine base, were ignored since by their thinking the war would be over before the influence of these facilities would be felt.

Approach and attack

On November 26, 1941, a Japanese task force (the Striking Force) of six aircraft carriers, , , , , and departed Hittokapu Bay on Kasatka (now Iterup) Island in theKuril Islands

The Kuril Islands or Kurile Islands (; rus, Кури́льские острова́, r=Kuril'skiye ostrova, p=kʊˈrʲilʲskʲɪjə ɐstrɐˈva; Japanese: or ) are a volcanic archipelago currently administered as part of Sakhalin Oblast in the ...

, ''en route'' to a position northwest of Hawaii, intending to launch its 408 aircraft to attack Pearl Harbor: 360 for the two attack waves and 48 on defensive combat air patrol

Combat air patrol (CAP) is a type of flying mission for fighter aircraft. A combat air patrol is an aircraft patrol provided over an objective area, over the force protected, over the critical area of a combat zone, or over an air defense area, ...

(CAP), including nine fighters from the first wave.

The first wave was to be the primary attack, while the second wave was to attack carriers as its first objective and cruisers as its second, with battleships as the third target. The first wave carried most of the weapons to attack capital ships, mainly specially adapted Type 91 aerial torpedo

An aerial torpedo (also known as an airborne torpedo or air-dropped torpedo) is a torpedo launched from a torpedo bomber aircraft into the water, after which the weapon propels itself to the target.

First used in World War I, air-dropped torped ...

es which were designed with an anti-roll mechanism and a rudder extension that let them operate in shallow water. The aircrews were ordered to select the highest value targets (battleships and aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and facilities for carrying, arming, deploying, and recovering aircraft. Typically, it is the capital ship of a fleet, as it allows a ...

s) or, if these were not present, any other high-value ships (cruisers and destroyers). First-wave dive bomber

A dive bomber is a bomber aircraft that dives directly at its targets in order to provide greater accuracy for the bomb it drops. Diving towards the target simplifies the bomb's trajectory and allows the pilot to keep visual contact througho ...

s were to attack ground targets. Fighters were ordered to strafe and destroy as many parked aircraft as possible to ensure they did not get into the air to intercept the bombers, especially in the first wave. When the fighters' fuel got low they were to refuel at the aircraft carriers and return to combat. Fighters were to serve CAP duties where needed, especially over US airfields.

Before the attack commenced, the Imperial Japanese Navy launched reconnaissance floatplanes from cruisers and , one to scout over Oahu and the other over Lahaina Roads, Maui, respectively, with orders to report on US fleet composition and location. Reconnaissance aircraft flights risked alerting the US, and were not necessary. US fleet composition and preparedness information in Pearl Harbor were already known due to the reports of the Japanese spy Takeo Yoshikawa

was a Japanese spy in Hawaii before the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941.

Early career

A 1933 graduate of the Imperial Japanese Naval Academy at Etajima (graduating at the top of his class), Yoshikawa served briefly at sea aboard the ...

. A report of the absence of the US fleet in Lahaina anchorage off Maui was received from the Tone's floatplane and fleet submarine . Another four scout planes patrolled the area between the Japanese carrier force (the Kidō Butai) and Niihau

Niihau ( Hawaiian: ), anglicized as Niihau ( ), is the westernmost main and seventh largest inhabited island in Hawaii. It is southwest of Kauaʻi across the Kaulakahi Channel. Its area is . Several intermittent playa lakes provide wetland hab ...

, to detect any counterattack.

Submarines

Fleet submarines , , , , and each embarked a Type Amidget submarine

A midget submarine (also called a mini submarine) is any submarine under 150 tons, typically operated by a crew of one or two but sometimes up to six or nine, with little or no on-board living accommodation. They normally work with mother ships, ...

for transport to the waters off Oahu. The five I-boats left Kure Naval District

was the second of four main administrative districts of the pre-war Imperial Japanese Navy. Its territory included the Seto Inland Sea, Inland Sea of Japan and the Pacific Ocean, Pacific coasts of southern Honshū from Wakayama prefecture, Wakayam ...

on November 25, 1941. On December 6, they came to within of the mouth of Pearl Harbor and launched their midget subs at about 01:00 local time on December 7. At 03:42 Hawaiian Time

Hawaiian may refer to:

* Native Hawaiians, the current term for the indigenous people of the Hawaiian Islands or their descendants

* Hawaii state residents, regardless of ancestry (only used outside of Hawaii)

* Hawaiian language

Historic uses

* ...

, the minesweeper

A minesweeper is a small warship designed to remove or detonate naval mines. Using various mechanisms intended to counter the threat posed by naval mines, minesweepers keep waterways clear for safe shipping.

History

The earliest known usage of ...

spotted a midget submarine periscope southwest of the Pearl Harbor entrance buoy and alerted the destroyer . The midget may have entered Pearl Harbor. However, ''Ward'' sank another midget submarine at 06:37 in the first American shots in the Pacific Theater. A midget submarine on the north side of Ford Island

Ford Island ( haw, Poka Ailana) is an islet in the center of Pearl Harbor, Oahu, in the U.S. state of Hawaii. It has been known as Rabbit Island, Marín's Island, and Little Goats Island, and its native Hawaiian name is ''Mokuumeume''. The isl ...

missed the seaplane tender

A seaplane tender is a boat or ship that supports the operation of seaplanes. Some of these vessels, known as seaplane carriers, could not only carry seaplanes but also provided all the facilities needed for their operation; these ships are rega ...

with her first torpedo and missed the attacking destroyer with her other one before being sunk by ''Monaghan'' at 08:43.

A third midget submarine, '' Ha-19'', grounded twice, once outside the harbor entrance and again on the east side of Oahu, where it was captured on December 8. Ensign Kazuo Sakamaki

was a Japanese naval officer who became the first prisoner of war of World War II to be captured by U.S. forces, and the second to be captured by Americans.

Early life and education

Sakamaki was born in what is now part of the city of Awa, T ...

swam ashore and was captured by Hawaii National Guard

The Hawaii National Guard consists of the Hawaii Army National Guard and the Hawaii Air National Guard. The Constitution of the United States specifically charges the National Guard with dual federal and state missions. Those functions range f ...

Corporal David Akui

David M. Akui (January 16, 1920 – September 15, 1987) was an American soldier who became famous for capturing the first Japanese prisoner of war in World War II. At the time, Akui was a corporal in Company G, 298th Infantry Regiment of the Haw ...

, becoming the first Japanese prisoner of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of wa ...

. A fourth had been damaged by a depth charge attack and was abandoned by its crew before it could fire its torpedoes. It was found outside the harbor in 1960. Japanese forces received a radio message from a midget submarine at 00:41 on December 8 claiming damage to one or more large warships inside Pearl Harbor.

In 1992, 2000, and 2001 Hawaii Undersea Research Laboratory

The Hawaii Undersea Research Laboratory (HURL) is a regional undersea research program within the School of Ocean and Earth Sciences and Technology (SOEST) at University of Hawaii at Manoa, in Honolulu. It is considered one of the more important ...

's submersibles found the wreck of the fifth midget submarine lying in three parts outside Pearl Harbor. The wreck was in the debris field where much surplus US equipment was dumped after the war, including vehicles and landing craft. Both of its torpedoes were missing. This correlates with reports of two torpedoes fired at the light cruiser

A light cruiser is a type of small or medium-sized warship. The term is a shortening of the phrase "light armored cruiser", describing a small ship that carried armor in the same way as an armored cruiser: a protective belt and deck. Prior to thi ...

at 10:04 at the entrance of Pearl Harbor, and a possible torpedo fired at destroyer at 08:21.

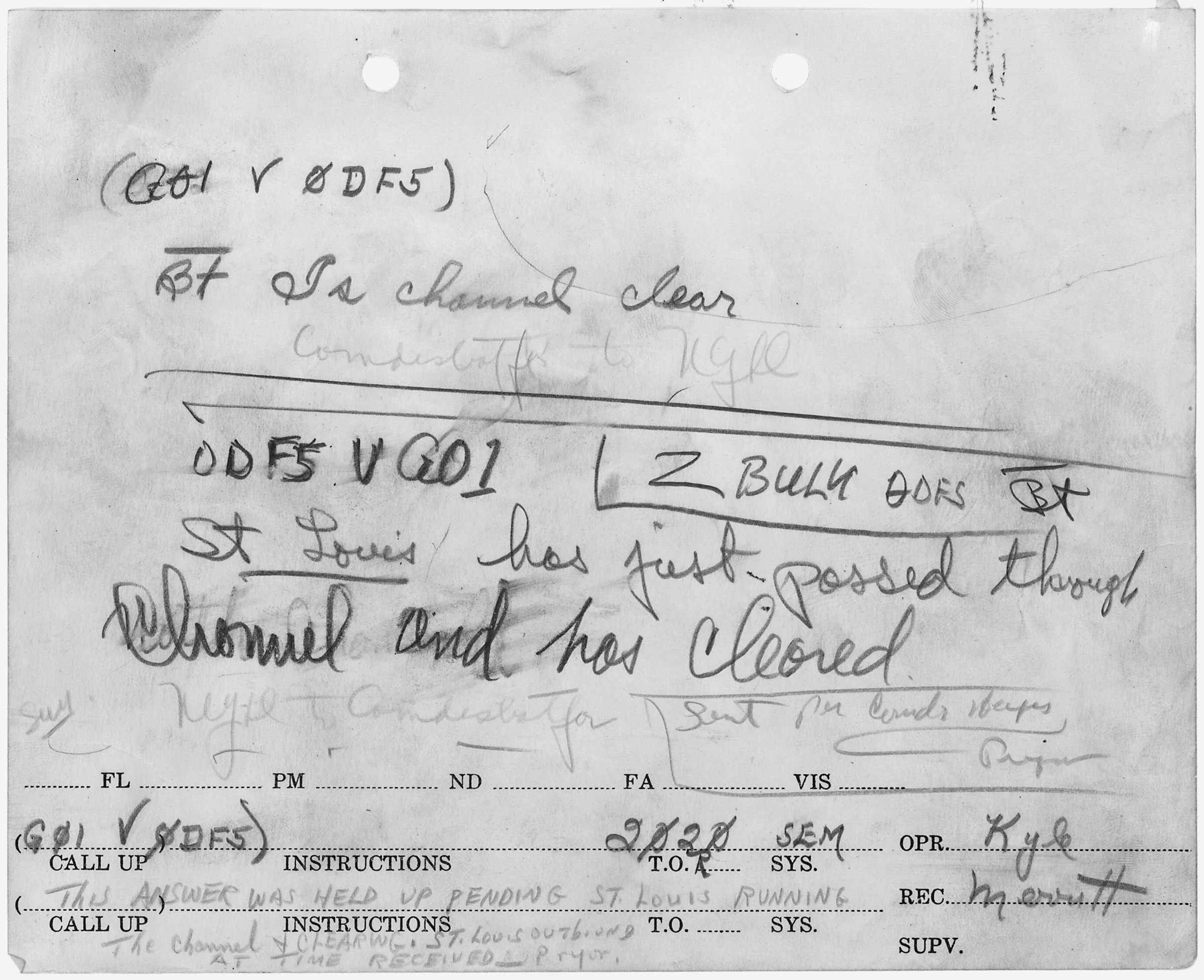

Japanese declaration of war

The attack took place before any formal declaration of war was made by Japan, but this was not Admiral Yamamoto's intention. He originally stipulated that the attack should not commence until thirty minutes after Japan had informed the United States that peace negotiations were at an end. However, the attack began before the notice could be delivered. Tokyo transmitted the 5000-word notification (commonly called the "14-Part Message") in two blocks to the Japanese Embassy in Washington. Transcribing the message took too long for the Japanese ambassador to deliver it at 1 pm Washington time, as ordered; in the event, it was not presented until more than an hour after the attack began. (In fact, US code breakers had already deciphered and translated most of the message hours before he was scheduled to deliver it.) The final part is sometimes described as a declaration of war. While it was viewed by a number of senior U.S government and military officials as a very strong indicator negotiations were likely to be terminated and that war might break out at any moment, it neither declared war nor severed diplomatic relations. A declaration of war was printed on the front page of Japan's newspapers in the evening edition of December 8 (late December 7 in the US), but not delivered to the US government until the day after the attack. For decades, conventional wisdom held that Japan attacked without first formally breaking diplomatic relations only because of accidents and bumbling that delayed the delivery of a document hinting at war to Washington. In 1999, however, Takeo Iguchi, a professor of law and international relations atInternational Christian University

is a non-denominational private university located in Mitaka, Tokyo, Japan, commonly known as ICU. With the efforts of Prince Takamatsu, General Douglas MacArthur, and BOJ President Hisato Ichimada, ICU was established in 1949 as the first ...

in Tokyo, discovered documents that pointed to a vigorous debate inside the government over how, and indeed whether, to notify Washington of Japan's intention to break off negotiations and start a war, including a December 7 entry in the war diary saying, " r deceptive diplomacy is steadily proceeding toward success." Of this, Iguchi said, "The diary shows that the army and navy did not want to give any proper declaration of war, or indeed prior notice even of the termination of negotiations... and they clearly prevailed."

In any event, even if the Japanese had decoded and delivered the 14-Part Message before the beginning of the attack, it would not have constituted either a formal break of diplomatic relations or a declaration of war. The final two paragraphs of the message read:

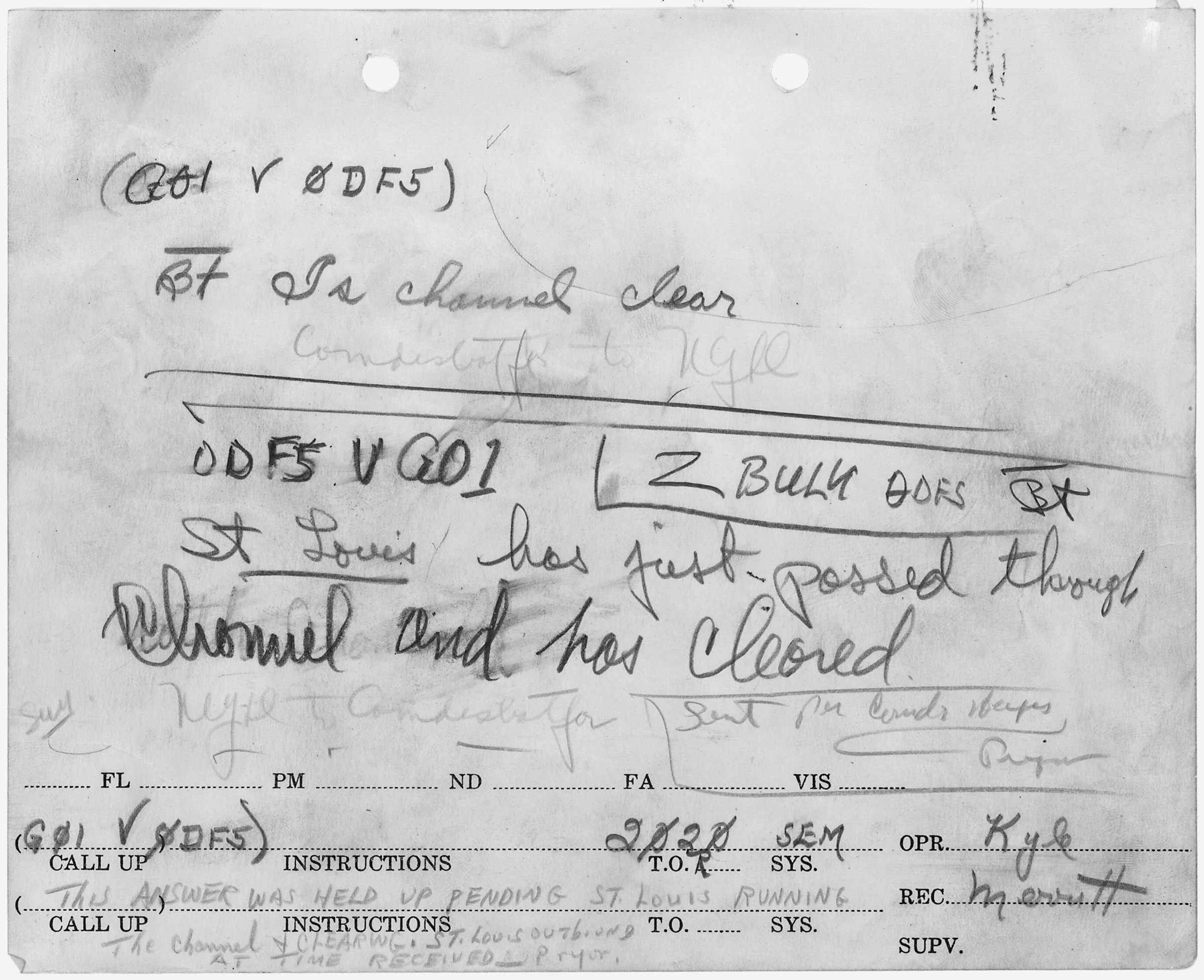

U.S. Naval intelligence officers were alarmed by the unusual timing for delivering the message – 1 pm on a Sunday, which was 7:30 am in Hawaii – and attempted to alert Pearl Harbor. But due to communication problems the warning was not delivered before the attack.

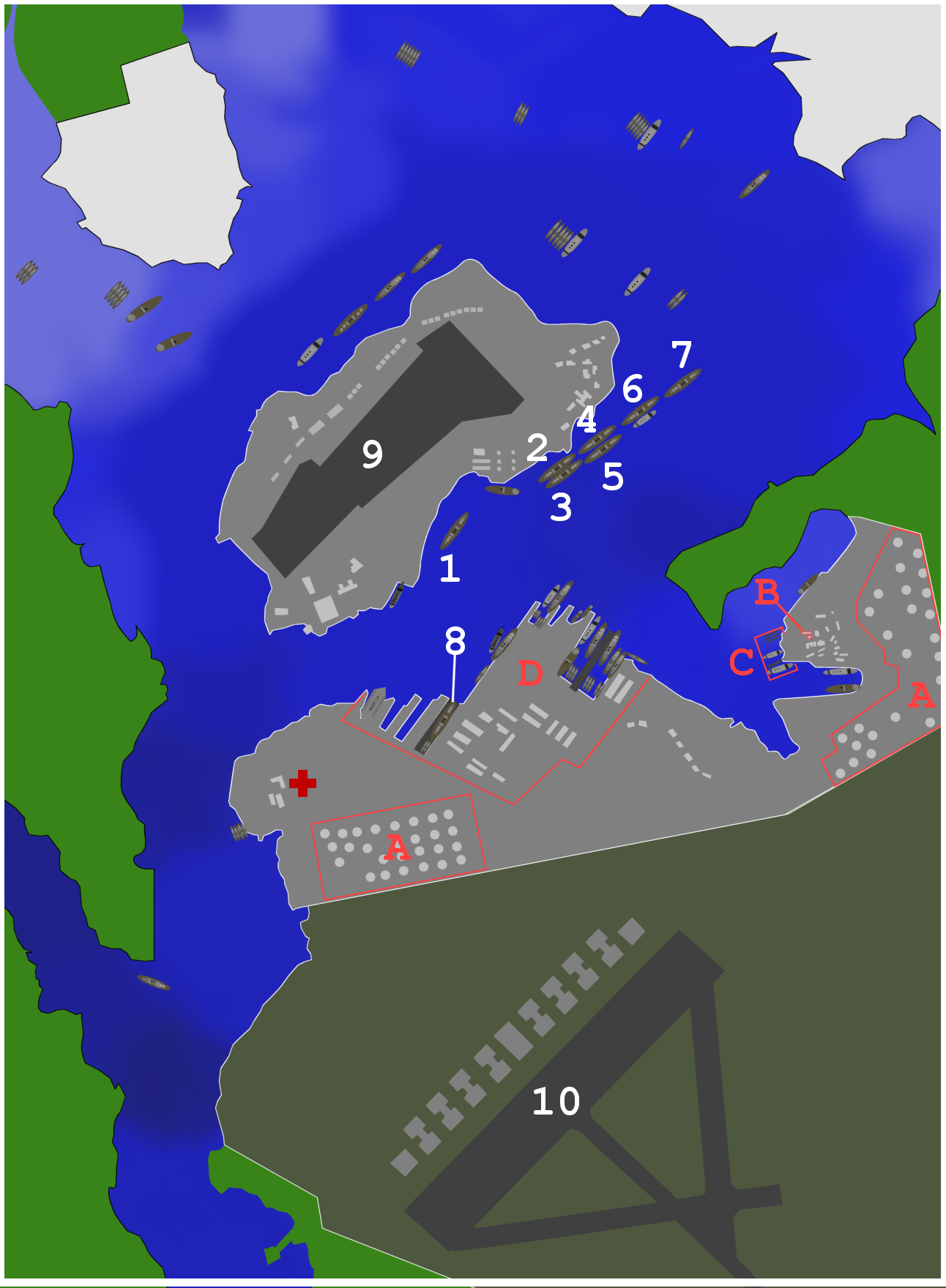

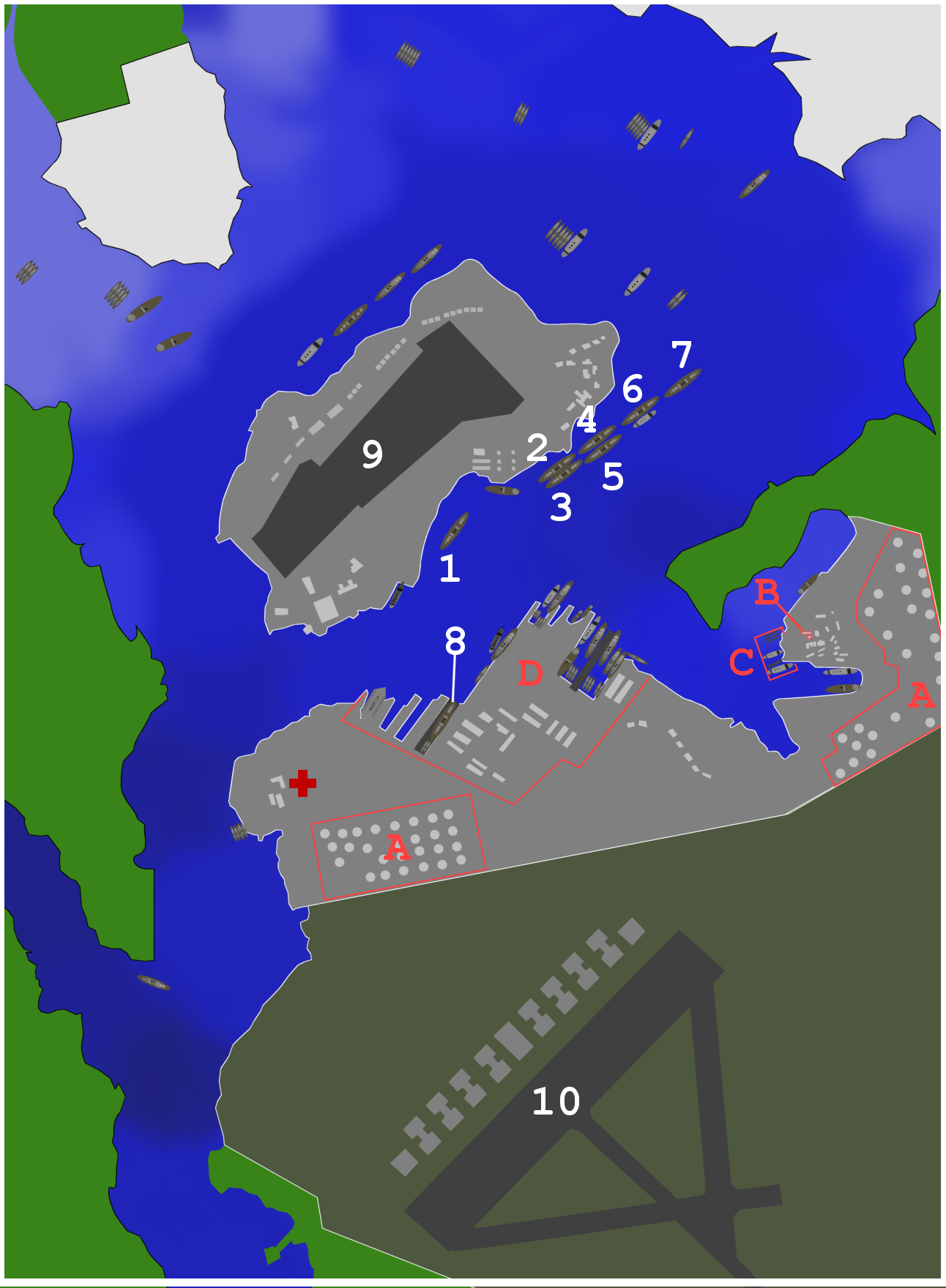

First wave composition

The first attack wave of 183 planes was launched north of Oahu, led by CommanderMitsuo Fuchida

was a Japanese captain in the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service and a bomber observer in the Imperial Japanese Navy before and during World War II. He is perhaps best known for leading the first wave of air attacks on Pearl Harbor on 7 Decembe ...

. Six planes failed to launch due to technical difficulties. The first attack included three groups of planes:

* 1st Group (targets: battleships and aircraft carriers)

** 49

* 1st Group (targets: battleships and aircraft carriers)

** 49 Nakajima B5N

The Nakajima B5N ( ja, 中島 B5N, Allied reporting name "Kate") was the standard carrier-based torpedo bomber of the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) for much of World War II.

Although the B5N was substantially faster and more capable than its Al ...

''Kate'' bombers armed with 800kg (1760lb) armor-piercing bomb

Armour-piercing ammunition (AP) is a type of projectile designed to penetrate either body armour or vehicle armour.

From the 1860s to 1950s, a major application of armour-piercing projectiles was to defeat the thick armour carried on many warsh ...

s, organized in four sections (one failed to launch)

** 40 B5N bombers armed with Type 91 torpedo

The Type 91 was an aerial torpedo of the Imperial Japanese Navy. It was in service from 1931 to 1945. It was used in naval battles in World War II and was specially developed for attacks on ships in shallow harbours.

The Type 91 aerial torped ...

es, also in four sections

* 2nd Group – (targets: Ford Island

Ford Island ( haw, Poka Ailana) is an islet in the center of Pearl Harbor, Oahu, in the U.S. state of Hawaii. It has been known as Rabbit Island, Marín's Island, and Little Goats Island, and its native Hawaiian name is ''Mokuumeume''. The isl ...

and Wheeler Field

Wheeler Army Airfield , also known as Wheeler Field and formerly as Wheeler Air Force Base, is a United States Army post located in the City & County of Honolulu and in the Wahiawa District of the Island of O'ahu, Hawaii. It is a National Histo ...

)

** 51 Aichi D3A

The Aichi D3A Type 99 Carrier Bomber ( Allied reporting name "Val") is a World War II carrier-borne dive bomber. It was the primary dive bomber of the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) and was involved in almost all IJN actions, including the at ...

''Val'' dive bombers armed with general-purpose bomb

A general-purpose bomb is an air-dropped bomb intended as a compromise between blast damage, penetration, and fragmentation in explosive effect. They are designed to be effective against enemy troops, vehicles, and buildings.

Characteristics ...

s (3 failed to launch)

* 3rd Group – (targets: aircraft at Ford Island, Hickam Field, Wheeler Field, Barber's Point, Kaneohe)

** 43 Mitsubishi A6M "Zero" fighters for air control and strafing

Strafing is the military practice of attacking ground targets from low-flying aircraft using aircraft-mounted automatic weapons.

Less commonly, the term is used by extension to describe high-speed firing runs by any land or naval craft such ...

(2 failed to launch)

As the first wave approached Oahu, it was detected by the US Army SCR-270 radar

The SCR-270 (Set Complete Radio model 270) was one of the first operational early-warning radars. It was the U.S. Army's primary long-distance radar throughout World War II and was deployed around the world. It is also known as the Pearl Harbor ...

at Opana Point near the island's northern tip. This post had been in training mode for months, but was not yet operational. The operators, Privates George Elliot Jr. and Joseph Lockard On the morning of 7 December 1941 the SCR-270 radar at the Opana Radar Site on northern Oahu detected a large number of aircraft approaching from the north. This information was conveyed to Fort Shafter’s Intercept Center. The report was dismissed ...

, reported a target to Private Joseph P. McDonald On the morning of 7 December 1941 the SCR-270 radar at the Opana Radar Site on northern Oahu detected a large number of aircraft approaching from the north. This information was conveyed to Fort Shafter’s Intercept Center. The report was dismissed ...

, a private stationed at Fort Shafter

Fort Shafter, in Honolulu CDP, Page 4/ref> City and County of Honolulu, Hawai‘i, is the headquarters of the United States Army Pacific, which commands most Army forces in the Asia-Pacific region with the exception of Korea. Geographically, Fort ...

's Intercept Center near Pearl Harbor. But Lieutenant Kermit A. Tyler, a newly assigned officer at the thinly manned Intercept Center, presumed it was the scheduled arrival of six B-17

The Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress is a four-engined heavy bomber developed in the 1930s for the United States Army Air Corps (USAAC). Relatively fast and high-flying for a bomber of its era, the B-17 was used primarily in the European Theater ...

bombers from California. The Japanese planes were approaching from a direction very close (only a few degrees difference) to the bombers, and while the operators had never seen a formation as large on radar, they neglected to tell Tyler of its size. Tyler, for security reasons, could not tell the operators of the six B-17s that were due (even though it was widely known).

As the first wave of planes approached Oahu, they encountered and shot down several US aircraft. At least one of these radioed a somewhat incoherent warning. Other warnings from ships off the harbor entrance were still being processed or awaiting confirmation when the Japanese air assault began at 7:48a.m. Hawaiian Time (3:18a.m. December 8 Japanese Standard Time

, or , is the standard time zone in Japan, 9 hours ahead of UTC ( UTC+09:00). Japan does not observe daylight saving time, though its introduction has been debated on several occasions. During World War II, the time zone was often referred to a ...

, as kept by ships of the ''Kido Butai''), with the attack on Kaneohe. A total of 353 Japanese planes reached Oahu in two waves. Slow, vulnerable torpedo bombers led the first wave, exploiting the first moments of surprise to attack the most important ships present (the battleships), while dive bombers attacked US air bases across Oahu, starting with Hickam Field Hickam may refer to:

;Surname

*Homer Hickam (born 1943), American author, Vietnam veteran, and a former NASA engineer

** October Sky: The Homer Hickam Story, 1999 American biographical film

*Horace Meek Hickam (1885–1934), pioneer airpower advoca ...

, the largest, and Wheeler Field

Wheeler Army Airfield , also known as Wheeler Field and formerly as Wheeler Air Force Base, is a United States Army post located in the City & County of Honolulu and in the Wahiawa District of the Island of O'ahu, Hawaii. It is a National Histo ...

, the main US Army Air Forces fighter base. The 171 planes in the second wave attacked the Army Air Forces' Bellows Field

A bellows or pair of bellows is a device constructed to furnish a strong blast of air. The simplest type consists of a flexible bag comprising a pair of rigid boards with handles joined by flexible leather sides enclosing an approximately airtigh ...

near Kaneohe on the windward side of the island and Ford Island. The only aerial opposition came from a handful of P-36 Hawk

The Curtiss P-36 Hawk, also known as the Curtiss Hawk Model 75, is an American-designed and built fighter aircraft of the 1930s and 40s. A contemporary of the Hawker Hurricane and Messerschmitt Bf 109, it was one of the first of a new generatio ...

s, P-40 Warhawk

The Curtiss P-40 Warhawk is an American single-engined, single-seat, all-metal fighter and ground-attack aircraft that first flew in 1938. The P-40 design was a modification of the previous Curtiss P-36 Hawk which reduced development time and ...

s, and some SBD Dauntless

The Douglas SBD Dauntless is a World War II American naval scout plane and dive bomber that was manufactured by Douglas Aircraft from 1940 through 1944. The SBD ("Scout Bomber Douglas") was the United States Navy's main carrier-based scout/dive ...

dive bombers from the carrier .

In the first-wave attack, about eight of the forty-nine 800kg (1760lb) armor-piercing bombs dropped hit their intended battleship targets. At least two of those bombs broke up on impact, another detonated before penetrating an unarmored deck, and one was a dud. Thirteen of the forty torpedoes hit battleships, and four torpedoes hit other ships. Men aboard US ships awoke to the sounds of alarms, bombs exploding, and gunfire, prompting bleary-eyed men to dress as they ran to

In the first-wave attack, about eight of the forty-nine 800kg (1760lb) armor-piercing bombs dropped hit their intended battleship targets. At least two of those bombs broke up on impact, another detonated before penetrating an unarmored deck, and one was a dud. Thirteen of the forty torpedoes hit battleships, and four torpedoes hit other ships. Men aboard US ships awoke to the sounds of alarms, bombs exploding, and gunfire, prompting bleary-eyed men to dress as they ran to General Quarters

General quarters, battle stations, or action stations is an announcement made aboard a naval warship

A warship or combatant ship is a naval ship that is built and primarily intended for naval warfare. Usually they belong to the armed ...

stations. (The famous message, "Air raid Pearl Harbor. This is not drill.", was sent from the headquarters of Patrol Wing Two, the first senior Hawaiian command to respond.) The defenders were very unprepared. Ammunition lockers were locked, aircraft parked wingtip to wingtip in the open to prevent sabotage, guns unmanned (none of the Navy's 5"/38s, only a quarter of its machine guns, and only four of 31 Army batteries got in action). Despite this low alert status

An alert state or state of alert is an indication of the state of readiness of the armed forces for military action or a state against natural disasters, terrorism or military attack. The term frequently used is "on high alert". Examples scales i ...

, many American military personnel responded effectively during the attack. Ensign Joseph Taussig Jr., aboard , commanded the ship's antiaircraft guns and was severely wounded but continued to be on post. Lt. Commander F. J. Thomas commanded ''Nevada'' in the captain's absence and got her underway until the ship was grounded at 9:10a.m. One of the destroyers, , got underway with only four officers aboard, all ensigns, none with more than a year's sea duty; she operated at sea for 36 hours before her commanding officer managed to get back aboard. Captain Mervyn Bennion

Mervyn Sharp Bennion (May 5, 1887 – December 7, 1941) was a United States Navy captain who served during World War I and was killed while he was in command of battleship during the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in World War II. He posth ...

, commanding , led his men until he was cut down by fragments from a bomb which hit , moored alongside.

Second wave composition

The second planned wave consisted of 171 planes: 54 B5Ns, 81 D3As, and 36 A6Ms, commanded byLieutenant-Commander

Lieutenant commander (also hyphenated lieutenant-commander and abbreviated Lt Cdr, LtCdr. or LCDR) is a commissioned officer rank in many navies. The rank is superior to a lieutenant and subordinate to a commander. The corresponding rank i ...

Shigekazu Shimazaki

, was a Japanese career officer in the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service during World War II.

Biography

Shimazaki was a native of Ōita Prefecture and a graduate of the 57th class of the Imperial Japanese Navy Academy in 1929, ranking 31st of 1 ...

. Four planes failed to launch because of technical difficulties. This wave and its targets also comprised three groups of planes:

* 1st Group – 54 B5Ns armed with and general-purpose bombs

** 27 B5Ns – aircraft and hangars on Kaneohe, Ford Island, and Barbers Point

** 27 B5Ns – hangars and aircraft on Hickam Field

* 2nd Group (targets: aircraft carriers and cruisers)

** 78 D3As armed with general-purpose bombs, in four sections (3 aborted)

* 3rd Group – (targets: aircraft at Ford Island, Hickam Field, Wheeler Field, Barber's Point, Kaneohe)

** 35 A6Ms for defense and strafing (1 aborted)

The second wave was divided into three groups. One was tasked to attack Kāneohe, the rest Pearl Harbor proper. The separate sections arrived at the attack point almost simultaneously from several directions.

American casualties and damage

Ninety minutes after it began, the attack was over. 2,008 sailors were killed and 710 others wounded; 218 soldiers and airmen (who were part of the Army prior to the independentUnited States Air Force

The United States Air Force (USAF) is the air service branch of the United States Armed Forces, and is one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. Originally created on 1 August 1907, as a part of the United States Army Signal ...

in 1947) were killed and 364 wounded; 109 Marines were killed and 69 wounded; and 68 civilians were killed and 35 wounded. In total, 2,403 Americans were killed, and 1,143 were wounded. Eighteen ships were sunk or run aground, including five battleships. All of the Americans killed or wounded during the attack were legally non-combatants, given that there was no state of war when the attack occurred.

Of the American fatalities, nearly half were due to the explosion of 's forward magazine

A magazine is a periodical publication, generally published on a regular schedule (often weekly or monthly), containing a variety of content. They are generally financed by advertising, purchase price, prepaid subscriptions, or by a combinatio ...

after it was hit by a modified shell. Author Craig Nelson wrote that the vast majority of the US sailors killed at Pearl Harbor were junior enlisted personnel. "The officers of the Navy all lived in houses and the junior people were the ones on the boats, so pretty much all of the people who died in the direct line of the attack were very junior people", Nelson said. "So everyone is about 17 or 18 whose story is told there."

Among the notable civilian casualties

Civilian casualties occur when civilians are killed or injured by non-civilians, mostly law enforcement officers, military personnel, rebel group forces, or terrorists. Under the law of war, it refers to civilians who perish or suffer wounds as ...

were nine Honolulu Fire Department

The Honolulu Fire Department (HFD) provides fire protection and first responder emergency medical services to the City & County of Honolulu, Hawaii, United States, under the jurisdiction of the Mayor of Honolulu. Founded on December 27, 1850, by K ...

(HFD) firefighters who responded to Hickam Field during the bombing in Honolulu, becoming the only fire department members on American soil to be attacked by a foreign power in history. Fireman Harry Tuck Lee Pang of Engine6 was killed near the hangars by machine-gun fire from a Japanese plane. Captains Thomas Macy and John Carreira of Engine4 and Engine1 respectively died while battling flames inside the hangar after a Japanese bomb crashed through the roof. An additional six firefighters were wounded from Japanese shrapnel. The wounded later received Purple Heart

The Purple Heart (PH) is a United States military decoration awarded in the name of the President to those wounded or killed while serving, on or after 5 April 1917, with the U.S. military. With its forerunner, the Badge of Military Merit, w ...

s (originally reserved for service members wounded by enemy action while partaking in armed conflicts) for their peacetime actions that day on June 13, 1944; the three firefighters killed did not receive theirs until December 7, 1984, at the 43rd anniversary of the attack. This made the nine men the only non-military firefighters to receive such an award in US history.

Already damaged by a torpedo and on fire amidships, ''Nevada'' attempted to exit the harbor. She was targeted by many Japanese bombers as she got under way and sustained more hits from bombs, which started further fires. She was deliberately beached to avoid blocking the harbor entrance. was hit by two bombs and two torpedoes. The crew might have kept her afloat, but were ordered to abandon ship just as they were raising power for the pumps. Burning oil from ''Arizona'' and drifted down on her and probably made the situation look worse than it was. The disarmed

Already damaged by a torpedo and on fire amidships, ''Nevada'' attempted to exit the harbor. She was targeted by many Japanese bombers as she got under way and sustained more hits from bombs, which started further fires. She was deliberately beached to avoid blocking the harbor entrance. was hit by two bombs and two torpedoes. The crew might have kept her afloat, but were ordered to abandon ship just as they were raising power for the pumps. Burning oil from ''Arizona'' and drifted down on her and probably made the situation look worse than it was. The disarmed target ship

A target ship is a vessel — typically an obsolete or captured warship — used as a seaborne target for naval gunnery practice or for weapons testing. Targets may be used with the intention of testing effectiveness of specific types of ammuniti ...

was holed twice by torpedoes. ''West Virginia'' was hit by seven torpedoes, the seventh tearing away her rudder. was hit by four torpedoes, the last two above her belt armor

Belt armor is a layer of heavy metal armor plated onto or within the outer hulls of warships, typically on battleships, battlecruisers and cruisers, and aircraft carriers.

The belt armor is designed to prevent projectiles from penetrating to ...

, which caused her to capsize. was hit by two of the converted 16" shells, but neither caused serious damage.

Although the Japanese concentrated on battleships (the largest vessels present), they did not ignore other targets. The light cruiser was torpedoed, and the concussion from the blast capsized the neighboring minelayer . Two destroyers in dry dock

A dry dock (sometimes drydock or dry-dock) is a narrow basin or vessel that can be flooded to allow a load to be floated in, then drained to allow that load to come to rest on a dry platform. Dry docks are used for the construction, maintenance, ...

, and , were destroyed when bombs penetrated their fuel bunkers

A bunker is a defensive military fortification designed to protect people and valued materials from falling bombs, artillery, or other attacks. Bunkers are almost always underground, in contrast to blockhouses which are mostly above ground. T ...

. The leaking fuel caught fire; flooding the dry dock in an effort to fight fire made the burning oil rise, and both were burned out. ''Cassin'' slipped from her keel blocks and rolled against ''Downes''. The light cruiser was holed by a torpedo. The light cruiser was damaged but remained in service. The repair vessel , moored alongside ''Arizona'', was heavily damaged and beached. The seaplane tender ''Curtiss'' was also damaged. The destroyer was badly damaged when two bombs penetrated her forward magazine.

Of the 402 American aircraft in Hawaii, 188 were destroyed and 159 damaged, 155 of them on the ground. Almost none were actually ready to take off to defend the base. Eight Army Air Forces pilots managed to get airborne during the attack, and six were credited with downing at least one Japanese aircraft during the attack: 1st Lt. Lewis M. Sanders, 2nd Lt. Philip M. Rasmussen, 2nd Lt. Kenneth M. Taylor

Kenneth Marlar Taylor (December 23, 1919 – November 25, 2006) was a United States Air Force officer and a flying ace of World War II. He was a new United States Army Air Corps second lieutenant pilot stationed at Wheeler Field during the Japan ...

, 2nd Lt. George S. Welch, 2nd Lt. Harry W. Brown, and 2nd Lt. Gordon H. Sterling Jr. Of 33 PBY

The Consolidated PBY Catalina is a flying boat and amphibious aircraft that was produced in the 1930s and 1940s. In Canadian service it was known as the Canso. It was one of the most widely used seaplanes of World War II. Catalinas served w ...

s in Hawaii, 30 were destroyed and three on patrol at the time of the attack returned undamaged. Friendly fire brought down some US planes on top of that, including four from an inbound flight from .

At the time of the attack, nine civilian aircraft were flying in the vicinity of Pearl Harbor. Of these, three were shot down.

Japanese losses

Fifty-five Japanese airmen and nine submariners were killed in the attack, and one,Kazuo Sakamaki

was a Japanese naval officer who became the first prisoner of war of World War II to be captured by U.S. forces, and the second to be captured by Americans.

Early life and education

Sakamaki was born in what is now part of the city of Awa, T ...

, was captured. Of Japan's 414 available planes, 350 took part in the raid in which twenty-nine were lost; nine in the first wave (three fighters, one dive bomber, and five torpedo bombers) and twenty in the second wave (six fighters and fourteen dive bombers) with another 74 damaged by antiaircraft fire from the ground.

Possible third wave

According to some accounts, several Japanese junior officers including Fuchida and Genda urged Nagumo to carry out a third strike in order to sink more of the Pearl Harbor's remaining warships, and damage the base's maintenance shops, drydock facilities, and oil tank yards. Most notably, Fuchida gave a firsthand account of this meeting several times after the war. However, some historians have cast doubt on this and many other of Fuchida's later claims, which sometimes conflict with documented historic records. Genda, who opined during the planning for the attack that without an invasion three strikes were necessary to fully disable the Pacific Fleet, denied requesting an additional attack. Regardless, it is undisputed that the captains of the other five carriers in the task force reported they were willing and ready to carry out a third strike soon after the second returned, but Nagumo decided to withdraw for several reasons: * American anti-aircraft performance had improved considerably during the second strike, and two-thirds of Japan's losses were incurred during the second wave. * Nagumo felt if he launched a third strike, he would be risking three-quarters of the Combined Fleet's strength to wipe out the remaining targets (which included the facilities) while suffering higher aircraft losses. * The location of the American carriers remained unknown. In addition, the admiral was concerned his force was now within range of American land-based bombers. Nagumo was uncertain whether the US had enough surviving planes remaining on Hawaii to launch an attack against his carriers. * A third wave would have required substantial preparation and turnaround time, and would have meant returning planes would have had to land at night. At the time, only theRoyal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

had developed night carrier techniques, so this was a substantial risk. The first two waves had launched the entirety of the Combined Fleet's air strength. A third wave would have required landing both the first and second wave before launching the first wave again. Compare Nagumo's situation in the Battle of Midway

The Battle of Midway was a major naval battle in the Pacific Theater of World War II that took place on 4–7 June 1942, six months after Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor and one month after the Battle of the Coral Sea. The U.S. Navy under Adm ...

where an attack returning from Midway kept Nagumo from launching an immediate strike on American carriers.

* The task force's fuel situation did not permit him to remain in waters north of Pearl Harbor much longer since he was at the very limit of logistical support. To do so risked running unacceptably low on fuel, perhaps even having to abandon destroyers en route home.

* He believed the second strike had essentially accomplished the mission's main objective (neutralizing the US Pacific Fleet) and did not wish to risk further losses. Moreover, it was IJN practice to prefer the conservation of strength over the total destruction of the enemy.

Although a hypothetical third strike would have likely focused on the base's remaining warships, military historians have suggested any potential damage to the shore facilities would have hampered the US Pacific Fleet far more seriously. If they had been wiped out, "serious merican

''Merican'' is an EP by the American punk rock band the Descendents, released February 10, 2004. It was the band's first release for Fat Wreck Chords and served as a pre-release to their sixth studio album ''Cool to Be You'', released the follow ...

operations in the Pacific would have been postponed for more than a year"; according to Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, later Commander in Chief of the Pacific Fleet, "it would have prolonged the war another two years".

At a conference aboard his flagship the following morning, Yamamoto supported Nagumo's withdrawal without launching a third wave. In retrospect, sparing the vital dockyards, maintenance shops, and the oil tank farm meant the US could respond relatively quickly to Japanese activities in the Pacific. Yamamoto later regretted Nagumo's decision to withdraw and categorically stated it had been a great mistake not to order a third strike.

Ships lost or damaged

Twenty-one American ships were damaged or lost in the attack, of which all but three were repaired and returned to service.Battleships

* (Rear Admiral Isaac C. Kidd's flagship of Battleship Division One): hit by four armor-piercing bombs, exploded; total loss. 1,177 dead. * : hit by five torpedoes, capsized; total loss. 429 dead. * : hit by two bombs, seven torpedoes, sunk; returned to service July 1944. 106 dead. * : hit by two bombs, two torpedoes, sunk; returned to service January 1944. 100 dead. * : hit by six bombs, one torpedo, beached; returned to service October 1942. 60 dead. * (AdmiralHusband E. Kimmel

Husband Edward Kimmel (February 26, 1882 – May 14, 1968) was a United States Navy four-star admiral who was the commander in chief of the United States Pacific Fleet (CINCPACFLT) during the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. He was removed fr ...

's flagship of the United States Pacific Fleet

The United States Pacific Fleet (USPACFLT) is a theater-level component command of the United States Navy, located in the Pacific Ocean. It provides naval forces to the Indo-Pacific Command. Fleet headquarters is at Joint Base Pearl Harbor� ...

): in dry dock

A dry dock (sometimes drydock or dry-dock) is a narrow basin or vessel that can be flooded to allow a load to be floated in, then drained to allow that load to come to rest on a dry platform. Dry docks are used for the construction, maintenance, ...

with ''Cassin'' and ''Downes'', hit by one bomb and debris from USS ''Cassin''; remained in service. 9 dead.

* : hit by two bombs; returned to service February 1942. 5 dead.

* : hit by two bombs; returned to service February 1942. 4 dead (including floatplane pilot shot down).

Ex-battleship (target/AA training ship)

* : hit by two torpedoes, capsized; total loss. 64 dead.Cruisers

* : hit by one torpedo; returned to service January 1942. 20 dead. * : hit by one torpedo; returned to service February 1942. * : near miss, light damage; remained in service.Destroyers