Paul Claudel on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

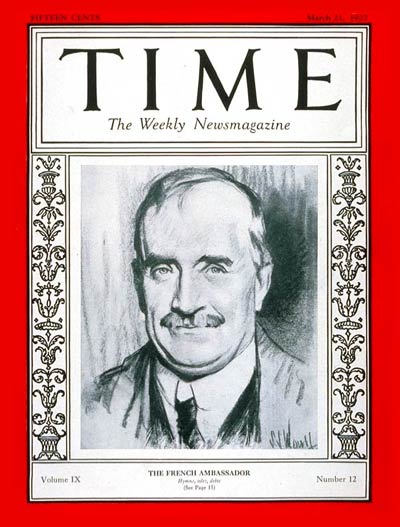

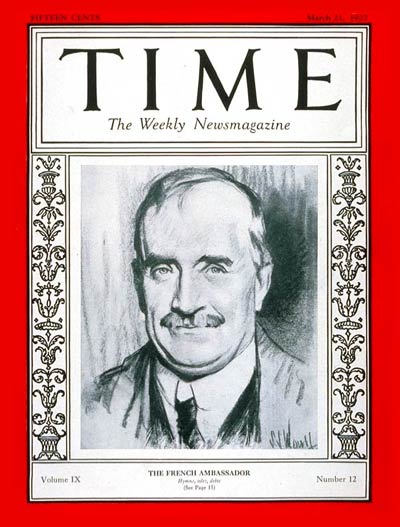

Paul Claudel (; 6 August 1868 – 23 February 1955) was a French poet, dramatist and diplomat, and the younger brother of the sculptor Camille Claudel. He was most famous for his verse dramas, which often convey his devout

An unbeliever in his teenage years, Claudel experienced a conversion at age 18 on Christmas Day 1886 while listening to a choir sing

An unbeliever in his teenage years, Claudel experienced a conversion at age 18 on Christmas Day 1886 while listening to a choir sing

Claudel committed his sister Camille to a psychiatric hospital in March 1913, where she remained for the last 30 years of her life, visiting her seven times in those 30 years. Records show that while she did have mental lapses, she was clear-headed while working on her art. Doctors tried to convince the family that she need not be in the institution, but still they kept her there.

The story forms the subject of a novel by

Claudel committed his sister Camille to a psychiatric hospital in March 1913, where she remained for the last 30 years of her life, visiting her seven times in those 30 years. Records show that while she did have mental lapses, she was clear-headed while working on her art. Doctors tried to convince the family that she need not be in the institution, but still they kept her there.

The story forms the subject of a novel by

Evil Genius

, ''The Guardian'', 14 August 2004. * Price-Jones, David, "Jews, Arabs and French Diplomacy: A Special Report", ''Commentary'', 22 May 2005, https://web.archive.org/web/20051218141558/http://www.benadorassociates.com/article/15043 * ''Album Claudel''. Iconographie choisie et annotée par Guy Goffette. Bibliothèque de la Pléiade. Éditions Gallimard, 2011. . (Illustrated biography.)

Paul-claudel.net

(in French) {{DEFAULTSORT:Claudel, Paul 1868 births 1955 deaths People from Aisne French Roman Catholics Sciences Po alumni Converts to Roman Catholicism from atheism or agnosticism Ambassadors of France to Belgium Ambassadors of France to Japan Ambassadors of France to the United States Deans of the Diplomatic Corps to the United States French Catholic poets 19th-century French dramatists and playwrights 20th-century French dramatists and playwrights 19th-century French poets Lycée Louis-le-Grand alumni Members of the Académie Française Roman Catholic writers 19th-century French diplomats 20th-century French diplomats

Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

.

Early life

He was born in Villeneuve-sur-Fère ( Aisne), into a family of farmers and government officials. His father, Louis-Prosper, dealt in mortgages and bank transactions. His mother, the former Louise Cerveaux, came from a Champagne family of Catholic farmers and priests. Having spent his first years inChampagne

Champagne (, ) is a sparkling wine originated and produced in the Champagne wine region of France under the rules of the appellation, that demand specific vineyard practices, sourcing of grapes exclusively from designated places within it, ...

, he studied at the '' lycée'' of Bar-le-Duc

Bar-le-Duc (), formerly known as Bar, is a commune in the Meuse département, of which it is the capital. The department is in Grand Est in northeastern France.

The lower, more modern and busier part of the town extends along a narrow valley, s ...

and at the Lycée Louis-le-Grand in 1881, when his parents moved to Paris.

An unbeliever in his teenage years, Claudel experienced a conversion at age 18 on Christmas Day 1886 while listening to a choir sing

An unbeliever in his teenage years, Claudel experienced a conversion at age 18 on Christmas Day 1886 while listening to a choir sing Vespers

Vespers is a service of evening prayer, one of the canonical hours in Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, Catholic (both Latin and Eastern), Lutheran, and Anglican liturgies. The word for this fixed prayer time comes from the Latin , meani ...

in the cathedral of Notre Dame de Paris

Notre-Dame de Paris (; meaning "Our Lady of Paris"), referred to simply as Notre-Dame, is a medieval Catholic cathedral on the Île de la Cité (an island in the Seine River), in the 4th arrondissement of Paris. The cathedral, dedicated to the ...

: "In an instant, my heart was touched, and I believed." He remained an active Catholic for the rest of his life. In addition, he discovered Arthur Rimbaud

Jean Nicolas Arthur Rimbaud (, ; 20 October 1854 – 10 November 1891) was a French poet known for his transgressive and surreal themes and for his influence on modern literature and arts, prefiguring surrealism. Born in Charleville, he sta ...

's book of poetry ''Illuminations''. He worked towards "the revelation through poetry, both lyrical and dramatic, of the grand design of creation".

Claudel studied at the Paris Institute of Political Studies

, motto_lang = fr

, mottoeng = Roots of the Future

, type = Public research university'' Grande école''

, established =

, founder = Émile Boutmy

, accreditation ...

.

Diplomat

The young Claudel considered entering a monastery, but instead had a career in the French diplomatic corps, in which he served from 1893 to 1936. Claudel was first vice-consul in New York (April 1893), and later inBoston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the capital city, state capital and List of municipalities in Massachusetts, most populous city of the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financ ...

(December 1893). He was French consul

Consul (abbrev. ''cos.''; Latin plural ''consules'') was the title of one of the two chief magistrates of the Roman Republic, and subsequently also an important title under the Roman Empire. The title was used in other European city-states th ...

in China during the period 1895 to 1909, with time in Shanghai

Shanghai (; , , Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ) is one of the four direct-administered municipalities of the People's Republic of China (PRC). The city is located on the southern estuary of the Yangtze River, with the Huangpu River flowin ...

(June 1895). On a break in 1900, he spent time at Ligugé Abbey

Ligugé Abbey, formally called the Abbey of St. Martin of Ligugé (french: Abbaye Saint-Martin de Ligugé), is a French Benedictine monastery in the Commune of Ligugé, located in the Department of Vienne. Dating to the 4th century, it is the sit ...

, but his proposed entry to the Benedictine Order

, image = Medalla San Benito.PNG

, caption = Design on the obverse side of the Saint Benedict Medal

, abbreviation = OSB

, formation =

, motto = (English: 'Pray and Work')

, foun ...

was postponed.

Claudel returned to China as vice-consul in Fuzhou (October 1900). He had a further break in France in 1905–6, when he married. He was one of a group of writers enjoying the support and patronage of Philippe Berthelot of the Foreign Ministry, who became a close friend; others were Jean Giraudoux, Paul Morand and Saint-John Perse. Because of his position in the Diplomatic Corps, at the beginning of his career Claudel published either anonymously or under a pseudonym, "since permission to publish was needed from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs".:11

For that reason, Claudel remained rather obscure as an author to 1909, unwilling to ask permission to publish under his own name because the permission might not be granted.:11 In that year, the founding group of the ''Nouvelle Revue Française

''La Nouvelle Revue Française'' (; "The New French Review") is a literary magazine based in France. In France, it is often referred to as the ''NRF''.

History and profile

The magazine was founded in 1909 by a group of intellectuals including And ...

'' (NRF), and in particular his friend André Gide

André Paul Guillaume Gide (; 22 November 1869 – 19 February 1951) was a French author and winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature (in 1947). Gide's career ranged from its beginnings in the symbolist movement, to the advent of anticolonialism ...

, were keen to recognise his work. Claudel sent them, for the first issue, the poem ''Hymne du Sacre-Sacrement'', to fulsome praise from Gide, and it was published under his name. He had not sought permission to publish, and there was a furore in which he was criticised. Attacks based on his religious views were in February also affecting the production of one of his plays.:15–17 Bertholet's advice was to ignore the critics.:18 note 42 The affair began a long collaboration of the NRF with Claudel.:12

Claudel also wrote extensively about China, with a definitive version of his ''Connaissance de l'Est'' published in 1914 by Georges Crès and Victor Segalen. In his final posting to China, he was consul in Tianjin

Tianjin (; ; Mandarin: ), alternately romanized as Tientsin (), is a municipality and a coastal metropolis in Northern China on the shore of the Bohai Sea. It is one of the nine national central cities in Mainland China, with a total popu ...

(1906–1909).

In a series of European postings to the outbreak of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, Claudel was in Prague

Prague ( ; cs, Praha ; german: Prag, ; la, Praga) is the capital and largest city in the Czech Republic, and the historical capital of Bohemia. On the Vltava river, Prague is home to about 1.3 million people. The city has a temperate ...

(December 1909), Frankfurt am Main

Frankfurt, officially Frankfurt am Main (; Hessian dialects, Hessian: , "Franks, Frank ford (crossing), ford on the Main (river), Main"), is the most populous city in the States of Germany, German state of Hesse. Its 791,000 inhabitants as o ...

(October 1911), and Hamburg

Hamburg (, ; nds, label=Hamburg German, Low Saxon, Hamborg ), officially the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg (german: Freie und Hansestadt Hamburg; nds, label=Low Saxon, Friee un Hansestadt Hamborg),. is the List of cities in Germany by popul ...

(October 1913). At this period he was interested in the theatre festival at Hellerau, which put on one of his plays, and the ideas of Jacques Copeau

Jacques Copeau (; 4 February 1879 – 20 October 1949) was a French Theatre, theatre director, producer, actor, and dramatist. Before he founded the Théâtre du Vieux-Colombier in Paris, he wrote theatre reviews for several Parisian journ ...

.

Claudel was in Rome (1915–1916), ''ministre plénipotentiaire'' in Rio de Janeiro

Rio de Janeiro ( , , ; literally 'River of January'), or simply Rio, is the capital of the Rio de Janeiro (state), state of the same name, Brazil's List of Brazilian states by population, third-most populous state, and the List of largest citi ...

(1917–1918), Copenhagen

Copenhagen ( or .; da, København ) is the capital and most populous city of Denmark, with a proper population of around 815.000 in the last quarter of 2022; and some 1.370,000 in the urban area; and the wider Copenhagen metropolitan ar ...

(1920), ambassador in Tokyo (1921–1927), Washington, D.C. (1928–1933, Dean of the Diplomatic Corps in 1933) and Brussels

Brussels (french: Bruxelles or ; nl, Brussel ), officially the Brussels-Capital Region (All text and all but one graphic show the English name as Brussels-Capital Region.) (french: link=no, Région de Bruxelles-Capitale; nl, link=no, Bruss ...

(1933–1936). While he served in Brazil during World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

he supervised the continued provision of food supplies from South America to France. His secretaries during the Brazil mission included Darius Milhaud

Darius Milhaud (; 4 September 1892 – 22 June 1974) was a French composer, conductor, and teacher. He was a member of Les Six—also known as ''The Group of Six''—and one of the most prolific composers of the 20th century. His compositions ...

, who wrote incidental music

Incidental music is music in a play, television program, radio program, video game, or some other presentation form that is not primarily musical. The term is less frequently applied to film music, with such music being referred to instead ...

to a number of Claudel's plays.

Later life

In 1935 Claudel retired toBrangues

Brangues () is a commune in the Isère department in southeastern France.

Population

See also

*Communes of the Isère department

The following is a list of the 512 Communes of France, communes in the French Departments of France, departme ...

in Dauphiné

The Dauphiné (, ) is a former province in Southeastern France, whose area roughly corresponded to that of the present departments of Isère, Drôme and Hautes-Alpes. The Dauphiné was originally the Dauphiné of Viennois.

In the 12th centu ...

, where he had bought the château

A château (; plural: châteaux) is a manor house or residence of the lord of the manor, or a fine country house of nobility or gentry, with or without fortifications, originally, and still most frequently, in French-speaking regions.

No ...

in 1927. He still spent winters in Paris.

During World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

Claudel made his way to Algeria

)

, image_map = Algeria (centered orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Algiers

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, religi ...

in 1940, after the Battle of France

The Battle of France (french: bataille de France) (10 May – 25 June 1940), also known as the Western Campaign ('), the French Campaign (german: Frankreichfeldzug, ) and the Fall of France, was the Nazi Germany, German invasion of French Third Rep ...

, and offered to serve Free France

Free France (french: France Libre) was a political entity that claimed to be the legitimate government of France following the dissolution of the Third Republic. Led by French general , Free France was established as a government-in-exil ...

. Not having a response to the offer, he returned to Brangues. He supported the Vichy regime

Vichy France (french: Régime de Vichy; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was the fascist French state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II. Officially independent, but with half of its terr ...

, but disagreed with Cardinal Alfred Baudrillart

Alfred-Henri-Marie Baudrillart, Orat. (6 January 1859 – 19 May 1942) was a French prelate of the Catholic Church, who became a Cardinal in 1935. An historian and writer, he served as Rector of the Institut Catholique de Paris from 1907 until his ...

's policy of collaboration with Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

.

Close to home, Paul-Louis Weiller

Paul-Louis Weiller (September 29, 1893, Paris - December 6, 1993, Geneva) was a French industrialist and philanthropist.

Biography

From a Jewish Alsatian family, Weiller was the son of the industrialist and politician Lazare Weiller (1858–1928 ...

, married to Claudel's daughter-in-law's sister, was arrested by the Vichy government in October 1940. Claudel went to Vichy to intercede for him, to no avail; Weiller escaped (with Claudel's assistance, the authorities suspected) and fled to New York. Claudel wrote in December 1941 to Isaïe Schwartz

Isaïe Schwartz (15 January 1876, in Traenheim – 1952, in Paris) was the Great Rabbi of France at the beginning of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that last ...

, expressing his opposition to the Statut des Juifs enacted by the regime. The Vichy authorities responded by having Claudel's house searched and keeping him under observation.

Claudel was elected to the Académie française

An academy (Attic Greek: Ἀκαδήμεια; Koine Greek Ἀκαδημία) is an institution of secondary education, secondary or tertiary education, tertiary higher education, higher learning (and generally also research or honorary membershi ...

on 4 April 1946, replacing Louis Gillet

Louis-Marie-Pierre-Dominique Gillet (11 December 1876 – 1 July 1943) was a French art historian and literary historian.

Life

Louis Gillet was born in Paris on 11 December 1876. He studied at the Collège Stanislas de Paris

The Collège Stani ...

. It followed a rejection in 1935, considered somewhat scandalous, when Claude Farrère

Claude Farrère, pseudonym of Frédéric-Charles Bargone (27 April 1876, in Lyon – 21 June 1957, in Paris), was a French Navy officer and writer. Many of his novels are based in exotic locations such as Istanbul, Saigon, or Nagasaki.

One ...

was preferred. He was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, caption =

, awarded_for = Outstanding contributions in literature

, presenter = Swedish Academy

, holder = Annie Ernaux (2022)

, location = Stockholm, Sweden

, year = 1901 ...

in six different years.

Work

Claudel often referred toStéphane Mallarmé

Stéphane Mallarmé ( , ; 18 March 1842 – 9 September 1898), pen name of Étienne Mallarmé, was a French poet and critic. He was a major French symbolist poet, and his work anticipated and inspired several revolutionary artistic schools of t ...

as his teacher. His poetic has been seen as Mallarmé's, with the addition of the idea of the world as a revelatory religious text

Religious texts, including scripture, are texts which various religions consider to be of central importance to their religious tradition. They differ from literature by being a compilation or discussion of beliefs, mythologies, ritual prac ...

. He rejected traditional prosody, developing the ''verset claudelien'', his own form of free verse

Free verse is an open form of poetry, which in its modern form arose through the French '' vers libre'' form. It does not use consistent meter patterns, rhyme, or any musical pattern. It thus tends to follow the rhythm of natural speech.

Defini ...

. It was within the orbit of experimentation by followers of Walt Whitman

Walter Whitman (; May 31, 1819 – March 26, 1892) was an American poet, essayist and journalist. A humanist, he was a part of the transition between transcendentalism and realism, incorporating both views in his works. Whitman is among ...

, impressive for Claudel, of whom Charles Péguy and André Spire

André Spire (28 July 1868 – 29 July 1966) was a French poet, writer, and Zionist activist.

Biography

Born in 1868 in Nancy, to a Jewish family of the middle bourgeoisie, long established in Lorraine, Spire studied literature, then law. He a ...

were two others working on a form of ''verset''. The influence of the Latin Vulgate

The Vulgate (; also called (Bible in common tongue), ) is a late-4th-century Bible translations into Latin, Latin translation of the Bible.

The Vulgate is largely the work of Jerome who, in 382, had been commissioned by Pope Damasus&nbs ...

has been disputed by Jean Grosjean

Jean Grosjean (born in Paris on 21 December 1912, died at Versailles (city), Versailles on 10 April 2006) was a French poet, writer and translator.

Overview

After a childhood in the provinces, he became an engineering fitter. He entered the semi ...

.

The best known of his plays are ''Le Partage de Midi'' ("The Break of Noon", 1906), ''L'Annonce faite à Marie'' ("The Tidings Brought to Mary", 1910) focusing on the themes of sacrifice, oblation and sanctification through the tale of a young medieval French peasant woman who contracts leprosy

Leprosy, also known as Hansen's disease (HD), is a long-term infection by the bacteria '' Mycobacterium leprae'' or '' Mycobacterium lepromatosis''. Infection can lead to damage of the nerves, respiratory tract, skin, and eyes. This nerve da ...

, and ''Le Soulier de Satin'' (" The Satin Slipper", 1931). The last is an exploration of human and divine love and longing, set in the Spanish empire of the siglo de oro

The Spanish Golden Age ( es, Siglo de Oro, links=no , "Golden Century") is a period of flourishing in arts and literature in Spain, coinciding with the political rise of the Spanish Empire under the Catholic Monarchs of Spain and the Spanish ...

. It was staged at the Comédie-Française

The Comédie-Française () or Théâtre-Français () is one of the few state theatre

Theatre or theater is a collaborative form of performing art that uses live performers, usually actors or actresses, to present the experience of a real ...

in 1943. ''Jeanne d'Arc au Bûcher

''Jeanne d'Arc au bûcher'' (''Joan of Arc at the Stake'') is an oratorio by Arthur Honegger, originally commissioned by Ida Rubinstein. It was set to a libretto by Paul Claudel, and the work runs about 70 minutes.

It premiered on 12 May 1938 in ...

'' ("Joan of Arc at the Stake", 1939) was an oratorio

An oratorio () is a large musical composition for orchestra, choir, and soloists. Like most operas, an oratorio includes the use of a choir, soloists, an instrumental ensemble, various distinguishable characters, and arias. However, opera is mus ...

with music by Arthur Honegger

Arthur Honegger (; 10 March 1892 – 27 November 1955) was a Swiss composer who was born in France and lived a large part of his life in Paris. A member of Les Six, his best known work is probably '' Antigone'', composed between 1924 and 1927 ...

. The settings of his plays tended to be romantically distant, medieval France or sixteenth-century Spanish South America. He used scenes of passionate, obsessive human love. The complexity, structure and scale of the plays meant that a positive reception of Claudel's drama by audiences was long delayed. His final dramatic work, ''L'Histoire de Tobie et de Sara

''L’Histoire de Tobie et de Sara'' is a three-act theatre play by Paul Claudel.

A first version was written in 1938, a second one in 1953. This play draws from the Book of Tobit.

Mises en scène

* 1947 : Maurice Cazeneuve, 1st festival d’A ...

'', was first produced by Jean Vilar

Jean Vilar (25 March 1912– 28 May 1971) was a French actor and theatre director.

Vilar trained under actor and theatre director Charles Dullin, then toured with an acting company throughout France. His directorial career began in 1943 in a sma ...

for the Festival d'Avignon

The ''Festival d'Avignon'', or Avignon Festival, is an annual arts festival held in the France, French city of Avignon every summer in July in the courtyard of the Palais des Papes as well as in other locations of the city. Founded in 1947 by Je ...

in 1947.

As well as his verse dramas, Claudel also wrote lyric poetry

Modern lyric poetry is a formal type of poetry which expresses personal emotions or feelings, typically spoken in the first person.

It is not equivalent to song lyrics, though song lyrics are often in the lyric mode, and it is also ''not'' equi ...

. A major example is the ''Cinq Grandes Odes'' (Five Great Odes, 1907).

Views and reputation

Claudel was a conservative of the old school, sharing theantisemitism

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

of conservative France,. He addressed a poem ("Paroles au Maréchal," "Words to the Marshal") after the defeat of France in 1940, commending Marshal Pétain

Marshal is a term used in several official titles in various branches of society. As marshals became trusted members of the courts of Medieval Europe, the title grew in reputation. During the last few centuries, it has been used for elevated o ...

for picking up and salvaging France's broken, wounded body. As a Catholic, he could not avoid a sense of satisfaction at the fall of the anti-clerical French Third Republic

The French Third Republic (french: Troisième République, sometimes written as ) was the system of government adopted in France from 4 September 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed during the Franco-Prussian War, until 10 July 194 ...

.

His diaries make clear his consistent contempt for Nazism (condemning it as early as 1930 as "demonic" and "wedded to Satan," and referring to communism

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society ...

and Nazism

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

as "Gog and Magog

Gog and Magog (; he, גּוֹג וּמָגוֹג, ''Gōg ū-Māgōg'') appear in the Hebrew Bible and the Quran as individuals, tribes, or lands. In Ezekiel 38, Gog is an individual and Magog is his land; in Genesis 10, Magog is a man and ep ...

"). He wrote an open letter to the World Jewish Conference in 1935, condemning the Nuremberg Laws

The Nuremberg Laws (german: link=no, Nürnberger Gesetze, ) were antisemitic and Racism, racist laws that were enacted in Nazi Germany on 15 September 1935, at a special meeting of the Reichstag (Nazi Germany), Reichstag convened during ...

as "abominable and stupid." His support for Charles de Gaulle and the Free French forces culminated in his victory ode addressed to de Gaulle when Paris was liberated in 1944.

The British poet W. H. Auden acknowledged the importance of Paul Claudel in his poem "In Memory of W. B. Yeats" (1939). Writing about Yeats, Auden says in lines 52–55 (from the originally published version, then excised by Auden in a later revision):

George Steiner

Francis George Steiner, FBA (April 23, 1929 – February 3, 2020) was a Franco-American literary critic, essayist, philosopher, novelist, and educator. He wrote extensively about the relationship between language, literature and society, and the ...

, in ''The Death of Tragedy'', called Claudel one of the three "masters of drama" in the 20th century, with Henry de Montherlant and Bertolt Brecht

Eugen Berthold Friedrich Brecht (10 February 1898 – 14 August 1956), known professionally as Bertolt Brecht, was a German theatre practitioner, playwright, and poet. Coming of age during the Weimar Republic, he had his first successes as a ...

.

Family

While in China, Claudel had a long affair with Rosalie Vetch née Ścibor-Rylska (1871–1951), wife of Francis Vetch (1862–1944) and granddaughter ofHamilton Vetch Hamilton Vetch (1804–1865) was a British officer of the Bengal Army of the East India Company, who reached the rank of major-general. He was active as a political agent in Upper Assam. The alternative spelling Veitch of his family name was also us ...

. Claudel knew Francis Vetch through his diplomatic work, and had met Rosalie on a sea voyage out from Marseille

Marseille ( , , ; also spelled in English as Marseilles; oc, Marselha ) is the prefecture of the French department of Bouches-du-Rhône and capital of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region. Situated in the camargue region of southern Fran ...

to Hong Kong

Hong Kong ( (US) or (UK); , ), officially the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China (abbr. Hong Kong SAR or HKSAR), is a city and special administrative region of China on the eastern Pearl River Delta i ...

in 1900. She had four children, and was pregnant with Claudel's child when the affair ended in February 1905. She married in 1907 Jan Willem Lintner. Louise Marie Agnes Vetch (1905–1996), born in Brussels, was Claudel's daughter by Rosalie. Francis Vetch and Claudel had caught up with Rosalie at a railway station on the German border in 1905, a meeting at which Rosalie signalled that her relationship with Claudel was over.

Claudel married on 15 March 1906 Reine Sainte-Marie Perrin (1880–1973). She was the daughter of Louis Sainte-Marie Perrin Louis may refer to:

* Louis (coin)

* Louis (given name), origin and several individuals with this name

* Louis (surname)

* Louis (singer), Serbian singer

* HMS ''Louis'', two ships of the Royal Navy

See also

Derived or associated terms

* Lewis ( ...

(1835–1917), an architect from Lyon

Lyon,, ; Occitan: ''Lion'', hist. ''Lionés'' also spelled in English as Lyons, is the third-largest city and second-largest metropolitan area of France. It is located at the confluence of the rivers Rhône and Saône, to the northwest of ...

known for completing the Basilica of Notre-Dame de Fourvière. They had two sons and three daughters.

Treatment of his sister

Claudel committed his sister Camille to a psychiatric hospital in March 1913, where she remained for the last 30 years of her life, visiting her seven times in those 30 years. Records show that while she did have mental lapses, she was clear-headed while working on her art. Doctors tried to convince the family that she need not be in the institution, but still they kept her there.

The story forms the subject of a novel by

Claudel committed his sister Camille to a psychiatric hospital in March 1913, where she remained for the last 30 years of her life, visiting her seven times in those 30 years. Records show that while she did have mental lapses, she was clear-headed while working on her art. Doctors tried to convince the family that she need not be in the institution, but still they kept her there.

The story forms the subject of a novel by Michèle Desbordes

Michèle Desbordes (4 August 1940, Saint-Cyr-en-Val ( Loiret) – 24 January 2006, Baule (Loiret), aged 65) was a French writer. A curator of university libraries, she received several awards for her story ''La Demande'' devoted to Leonardo da Vi ...

, ''La Robe bleue'', ''The Blue Dress''. Jean-Charles de Castelbajac wrote a song "La soeur de Paul" for Mareva Galanter, 2010.

See also

* ''L'Histoire de Tobie et de Sara

''L’Histoire de Tobie et de Sara'' is a three-act theatre play by Paul Claudel.

A first version was written in 1938, a second one in 1953. This play draws from the Book of Tobit.

Mises en scène

* 1947 : Maurice Cazeneuve, 1st festival d’A ...

''

* ''L'Annonce faite à Marie

''The Annunciation of Marie'' is the English-language title of the 1991 French-Canadian film ''L'Annonce faite à Marie'', an adaptation of the play of the same name by Paul Claudel.

Production

The director of this film, the French stage and film ...

'', film adaptation

* Lycée Claudel

In France, secondary education is in two stages:

* ''Collèges'' () cater for the first four years of secondary education from the ages of 11 to 15.

* ''Lycées'' () provide a three-year course of further secondary education for children between ...

, a French language high school in Ottawa

Ottawa (, ; Canadian French: ) is the capital city of Canada. It is located at the confluence of the Ottawa River and the Rideau River in the southern portion of the province of Ontario. Ottawa borders Gatineau, Quebec, and forms the core ...

, Canada, named after him

* ''Camille Claudel'', 1988 film

* '' Camille Claudel 1915'', 2013 film

References

Sources

* Thody, P.M.W. "Paul Claudel", in ''The Fontana Biographical Companion to Modern Thought'', eds. Bullock, Alan and Woodings, R.B., Oxford, 1983. * Ayral-Clause, Odile, ''Camille Claudel, A Life'', 2002. * Ashley, Tim:Evil Genius

, ''The Guardian'', 14 August 2004. * Price-Jones, David, "Jews, Arabs and French Diplomacy: A Special Report", ''Commentary'', 22 May 2005, https://web.archive.org/web/20051218141558/http://www.benadorassociates.com/article/15043 * ''Album Claudel''. Iconographie choisie et annotée par Guy Goffette. Bibliothèque de la Pléiade. Éditions Gallimard, 2011. . (Illustrated biography.)

External links

Paul-claudel.net

(in French) {{DEFAULTSORT:Claudel, Paul 1868 births 1955 deaths People from Aisne French Roman Catholics Sciences Po alumni Converts to Roman Catholicism from atheism or agnosticism Ambassadors of France to Belgium Ambassadors of France to Japan Ambassadors of France to the United States Deans of the Diplomatic Corps to the United States French Catholic poets 19th-century French dramatists and playwrights 20th-century French dramatists and playwrights 19th-century French poets Lycée Louis-le-Grand alumni Members of the Académie Française Roman Catholic writers 19th-century French diplomats 20th-century French diplomats