Pathogenomics on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Pathogenomics is a field which uses

Pan-genome overview The most recent definition of a bacterial species comes from the pre-genomic era. In 1987, it was proposed that bacterial strains showing >70% DNA·DNA re-association and sharing characteristic phenotypic traits should be considered to be strains of the same species. The diversity within pathogen genomes makes it difficult to identify the total number of genes that are associated within all strains of a pathogen species. It has been thought that the total number of genes associated with a single pathogen species may be unlimited, although some groups are attempting to derive a more empirical value. For this reason, it was necessary to introduce the concept of

Pan-genome overview The most recent definition of a bacterial species comes from the pre-genomic era. In 1987, it was proposed that bacterial strains showing >70% DNA·DNA re-association and sharing characteristic phenotypic traits should be considered to be strains of the same species. The diversity within pathogen genomes makes it difficult to identify the total number of genes that are associated within all strains of a pathogen species. It has been thought that the total number of genes associated with a single pathogen species may be unlimited, although some groups are attempting to derive a more empirical value. For this reason, it was necessary to introduce the concept of

Microbe-host interactions tend to overshadow the consideration of microbe-microbe interactions. Microbe-microbe interactions though can lead to chronic states of infirmity that are difficult to understand and treat.

Microbe-host interactions tend to overshadow the consideration of microbe-microbe interactions. Microbe-microbe interactions though can lead to chronic states of infirmity that are difficult to understand and treat.

* ''Microarray analysis of host and microbe gene expression during infection''. This is important for identifying the expression of virulence factors that allow a pathogen to survive a host's defense mechanism. Pathogens tend to undergo an assortment of changed in order to subvert and hosts immune system, in some case favoring a hyper variable genome state. The genomic expression studies will be complemented with protein-protein interaction networks studies.

* ''Using RNA interference (RNAi) to identify host cell functions in response to infections''. Infection depends on the balance between the characteristics of the host cell and the pathogen cell. In some cases, there can be an overactive host response to infection, such as in meningitis, which can overwhelm the host's body. Using RNA, it will be possible to more clearly identify how a host cell defends itself during times of acute or chronic infection. This has also been applied successfully is Drosophila.

* ''Not all microbe interactions in host environment are malicious. ''

* ''Microarray analysis of host and microbe gene expression during infection''. This is important for identifying the expression of virulence factors that allow a pathogen to survive a host's defense mechanism. Pathogens tend to undergo an assortment of changed in order to subvert and hosts immune system, in some case favoring a hyper variable genome state. The genomic expression studies will be complemented with protein-protein interaction networks studies.

* ''Using RNA interference (RNAi) to identify host cell functions in response to infections''. Infection depends on the balance between the characteristics of the host cell and the pathogen cell. In some cases, there can be an overactive host response to infection, such as in meningitis, which can overwhelm the host's body. Using RNA, it will be possible to more clearly identify how a host cell defends itself during times of acute or chronic infection. This has also been applied successfully is Drosophila.

* ''Not all microbe interactions in host environment are malicious. ''

Human health has greatly improved and the mortality rate has declined substantially since the second world war because of improved hygiene due to changing public health regulations, as well as more readily available vaccines and antibiotics. Pathogenomics will allow scientists to expand what they know about pathogenic and non-pathogenic microbes, thus allowing for new and improved vaccines. Pathogenomics also has wider implication, including preventing bioterrorism.

Human health has greatly improved and the mortality rate has declined substantially since the second world war because of improved hygiene due to changing public health regulations, as well as more readily available vaccines and antibiotics. Pathogenomics will allow scientists to expand what they know about pathogenic and non-pathogenic microbes, thus allowing for new and improved vaccines. Pathogenomics also has wider implication, including preventing bioterrorism.

high-throughput screening

High-throughput screening (HTS) is a method for scientific experimentation especially used in drug discovery and relevant to the fields of biology, materials science and chemistry. Using robotics, data processing/control software, liquid handlin ...

technology and bioinformatics

Bioinformatics () is an interdisciplinary field that develops methods and software tools for understanding biological data, in particular when the data sets are large and complex. As an interdisciplinary field of science, bioinformatics combi ...

to study encoded microbe resistance, as well as virulence factors (VFs), which enable a microorganism to infect a host and possibly cause disease. This includes studying genome

In the fields of molecular biology and genetics, a genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding ge ...

s of pathogen

In biology, a pathogen ( el, πάθος, "suffering", "passion" and , "producer of") in the oldest and broadest sense, is any organism or agent that can produce disease. A pathogen may also be referred to as an infectious agent, or simply a germ ...

s which cannot be cultured outside of a host. In the past, researchers and medical professionals found it difficult to study and understand pathogenic traits of infectious organisms. With newer technology, pathogen genomes can be identified and sequenced in a much shorter time and at a lower cost, thus improving the ability to diagnose, treat, and even predict and prevent pathogenic infections and disease. It has also allowed researchers to better understand genome evolution events - gene loss, gain, duplication, rearrangement - and how those events impact pathogen resistance and ability to cause disease. This influx of information has created a need for bioinformatics tools and databases to analyze and make the vast amounts of data accessible to researchers, and it has raised ethical questions about the wisdom of reconstructing previously extinct and deadly pathogens in order to better understand virulence.

History

During the earlier times when genomics was being studied, scientists found it challenging to sequence genetic information. The field began to explode in 1977 whenFred Sanger

Frederick Sanger (; 13 August 1918 – 19 November 2013) was an English biochemist who received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry twice.

He won the 1958 Chemistry Prize for determining the amino acid sequence of insulin and numerous other ...

, PhD, along with his colleagues, sequenced the DNA-based genome of a bacteriophage

A bacteriophage (), also known informally as a ''phage'' (), is a duplodnaviria virus that infects and replicates within bacteria and archaea. The term was derived from "bacteria" and the Greek φαγεῖν ('), meaning "to devour". Bacteri ...

, using a method now known as the Sanger Method. The Sanger Method for sequencing DNA exponentially advanced molecular biology and directly led to the ability to sequence genomes of other organisms, including the complete human genome.

The Haemophilus influenza genome was one of the first organism genomes sequenced in 1995 by J. Craig Venter and Hamilton Smith using whole genome shotgun sequencing. Since then, newer and more efficient high-throughput sequencing, such as Next Generation Genomic Sequencing (NGS) and Single-Cell Genomic Sequencing, have been developed. While the Sanger method is able to sequence one DNA fragment at a time, NGS technology can sequence thousands of sequences at a time. With the ability to rapidly sequence DNA, new insights developed, such as the discovery that since prokaryotic genomes are more diverse than originally thought, it is necessary to sequence multiple strains in a species rather than only a few. ''E.coli'' was an example of why this is important, with genes encoding virulence factors in two strains of the species differing by at least thirty percent. Such knowledge, along with more thorough study of genome gain, loss, and change, is giving researchers valuable insight into how pathogens interact in host environments and how they are able to infect hosts and cause disease.

Pathogen Bioinformatics

With this high influx of new information, there has arisen a higher demand for bioinformatics so scientists can properly analyze the new data. In response, software and other tools have been developed for this purpose. Also, as of 2008, the amount of stored sequences was doubling every 18 months, making urgent the need for better ways to organize data and aid research. In response, many publicly accessible databases and other resources have been created, including the NCBI pathogen detection program, the Pathosystems Resource Integration Centre (PATRIC), Pathogenwatch, the Virulence Factor Database (VFDB) of pathogenic bacteria, the Victors database of virulence factors in human and animal pathogens. Until 2022, the most sequenced pathogens are ''Salmonella enterica'' and ''E. coli - Shigella.'' The sequencing technologies, the bioinformatics tools, the databases, statistics related to pathogen genomes and the applications in forensics, epidemiology, clinical practice and food safety have been extensively reviewed.Microbe analysis

Pathogens

In biology, a pathogen ( el, πάθος, "suffering", "passion" and , "producer of") in the oldest and broadest sense, is any organism or agent that can produce disease. A pathogen may also be referred to as an infectious agent, or simply a germ ...

may be prokaryotic

A prokaryote () is a Unicellular organism, single-celled organism that lacks a cell nucleus, nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. The word ''prokaryote'' comes from the Greek language, Greek wikt:πρό#Ancient Greek, πρό (, 'before') a ...

(archaea

Archaea ( ; singular archaeon ) is a domain of single-celled organisms. These microorganisms lack cell nuclei and are therefore prokaryotes. Archaea were initially classified as bacteria, receiving the name archaebacteria (in the Archaebac ...

or bacteria

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were among ...

), single-celled eukarya

Eukaryotes () are organisms whose cells have a nucleus. All animals, plants, fungi, and many unicellular organisms, are Eukaryotes. They belong to the group of organisms Eukaryota or Eukarya, which is one of the three domains of life. Bacte ...

or virus

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea.

Since Dmitri Ivanovsky's 1 ...

es. Prokaryotic genomes have typically been easier to sequence due to smaller genome size compared to Eukarya. Due to this, there is a bias in reporting pathogenic bacteria

Pathogenic bacteria are bacteria that can cause disease. This article focuses on the bacteria that are pathogenic to humans. Most species of bacteria are harmless and are often Probiotic, beneficial but others can cause infectious diseases. The n ...

l behavior. Regardless of this bias in reporting, many of the dynamic genomic events are similar across all the types of pathogen organisms. Genomic evolution occurs via gene gain, gene loss, and genome rearrangement, and these "events" are observed in multiple pathogen genomes, with some bacterial pathogens experiencing all three. Pathogenomics does not focus exclusively on understanding pathogen-host interactions, however. Insight of individual or cooperative pathogen behavior provides knowledge into the development or inheritance of pathogen virulence factors. Through a deeper understanding of the small sub-units that cause infection, it may be possible to develop novel therapeutics that are efficient and cost-effective.

Cause and analysis of genomic diversity

Dynamicgenomes

In the fields of molecular biology and genetics, a genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding gen ...

with high plasticity are necessary to allow pathogens, especially bacteria, to survive in changing environments. With the assistance of high throughput sequencing methods and in silico

In biology and other experimental sciences, an ''in silico'' experiment is one performed on computer or via computer simulation. The phrase is pseudo-Latin for 'in silicon' (correct la, in silicio), referring to silicon in computer chips. It ...

technologies, it is possible to detect, compare and catalogue many of these dynamic genomic events. Genomic diversity is important when detecting and treating a pathogen since these events can change the function and structure of the pathogen. There is a need to analyze more than a single genome sequence of a pathogen species to understand pathogen mechanisms. Comparative genomics

Comparative genomics is a field of biological research in which the genomic features of different organisms are compared. The genomic features may include the DNA sequence, genes, gene order, regulatory sequences, and other genomic structural lan ...

is a methodology which allows scientists to compare the genomes of different species and strains. There are several examples of successful comparative genomics studies, among them the analysis of ''Listeria'' and ''Escherichia coli''. Some studies have attempted to address the difference between pathogen

In biology, a pathogen ( el, πάθος, "suffering", "passion" and , "producer of") in the oldest and broadest sense, is any organism or agent that can produce disease. A pathogen may also be referred to as an infectious agent, or simply a germ ...

ic and non-pathogenic microbes. This inquiry proves to be difficult, however, since a single bacterial species can have many strains, and the genomic content of each of these strains varies.

Evolutionary dynamics

Varying microbe strains and genomic content are caused by different forces, including three specific evolutionary events which have an impact on pathogen resistance and ability to cause disease, a: gene gain, gene loss, and genome rearrangement.= Gene loss and genome decay

= Gene loss occurs when genes are deleted. The reason why this occurs is still not fully understood, though it most likely involves adaptation to a new environment or ecological niche. Some researchers believe gene loss may actually increase fitness and survival among pathogens. In a new environment, some genes may become unnecessary for survival, and so mutations are eventually "allowed" on those genes until they become inactive "pseudogene

Pseudogenes are nonfunctional segments of DNA that resemble functional genes. Most arise as superfluous copies of functional genes, either directly by DNA duplication or indirectly by Reverse transcriptase, reverse transcription of an mRNA trans ...

s." These pseudogenes are observed in organisms such as ''Shigella flexneri

''Shigella flexneri'' is a species of Gram-negative bacteria in the genus ''Shigella'' that can cause diarrhea in humans. Several different serogroups of ''Shigella'' are described; ''S. flexneri'' belongs to group ''B''. ''S. flexneri'' infecti ...

, Salmonella enterica

''Salmonella enterica'' (formerly ''Salmonella choleraesuis'') is a rod-headed, flagellate, facultative anaerobic, Gram-negative bacterium and a species of the genus ''Salmonella''. A number of its serovars are serious human pathogens.

Epidemi ...

,'' and ''Yersinia pestis

''Yersinia pestis'' (''Y. pestis''; formerly '' Pasteurella pestis'') is a gram-negative, non-motile, coccobacillus bacterium without spores that is related to both ''Yersinia pseudotuberculosis'' and ''Yersinia enterocolitica''. It is a facult ...

.'' Over time, the pseudogenes are deleted, and the organisms become fully dependent on their host as either endosymbiont

An ''endosymbiont'' or ''endobiont'' is any organism that lives within the body or cells of another organism most often, though not always, in a mutualistic relationship.

(The term endosymbiosis is from the Greek: ἔνδον ''endon'' "within" ...

s or obligate intracellular pathogens, as is seen in '' Buchnera, Myobacterium leprae, and Chlamydia trachomatis

''Chlamydia trachomatis'' (), commonly known as chlamydia, is a bacterium that causes chlamydia, which can manifest in various ways, including: trachoma, lymphogranuloma venereum, nongonococcal urethritis, cervicitis, salpingitis, pelvic inflamma ...

''. These deleted genes are also called Anti-virulence genes (AVG) since it is thought they may have prevented the organism from becoming pathogenic. In order to be more virulent, infect a host and remain alive, the pathogen had to get rid of those AVGs. The reverse process can happen as well, as was seen during analysis of ''Listeria

''Listeria'' is a genus of bacteria that acts as an intracellular parasite in mammals. Until 1992, 17 species were known, each containing two subspecies. By 2020, 21 species had been identified. The genus is named in honour of the British pi ...

'' strains, which showed that a reduced genome size led to a non-pathogenic ''Listeria'' strain from a pathogenic strain. Systems have been developed to detect these pseudogenes/AVGs in a genome sequence.

= Gene gain and duplication

= One of the key forces driving gene gain is thought to be horizontal (lateral) gene transfer (LGT). It is of particular interest in microbial studies because these mobile genetic elements may introduce virulence factors into a new genome. A comparative study conducted by Gill et al. in 2005 postulated that LGT may have been the cause for pathogen variations betweenStaphylococcus epidermidis

''Staphylococcus epidermidis'' is a Gram-positive bacterium, and one of over 40 species belonging to the genus '' Staphylococcus''. It is part of the normal human microbiota, typically the skin microbiota, and less commonly the mucosal microbio ...

and Staphylococcus aureus

''Staphylococcus aureus'' is a Gram-positive spherically shaped bacterium, a member of the Bacillota, and is a usual member of the microbiota of the body, frequently found in the upper respiratory tract and on the skin. It is often positive ...

. There still, however, remains skepticism about the frequency of LGT, its identification, and its impact. New and improved methodologies have been engaged, especially in the study of phylogenetics

In biology, phylogenetics (; from Greek language, Greek wikt:φυλή, φυλή/wikt:φῦλον, φῦλον [] "tribe, clan, race", and wikt:γενετικός, γενετικός [] "origin, source, birth") is the study of the evolutionary his ...

, to validate the presence and effect of LGT. Gene gain and gene duplication events are balanced by gene loss, such that despite their dynamic nature, the genome of a bacterial species remains approximately the same size.

= Genome rearrangement

= Mobile geneticinsertion sequences Insertion element (also known as an IS, an insertion sequence element, or an IS element) is a short DNA sequence that acts as a simple transposable element. Insertion sequences have two major characteristics: they are small relative to other transp ...

can play a role in genome rearrangement activities. Pathogens that do not live in an isolated environment have been found to contain a large number of insertion sequence elements and various repetitive segments of DNA. The combination of these two genetic elements is thought help mediate homologous recombination

Homologous recombination is a type of genetic recombination in which genetic information is exchanged between two similar or identical molecules of double-stranded or single-stranded nucleic acids (usually DNA as in cellular organisms but may ...

. There are pathogens, such as ''Burkholderia mallei

''Burkholderia mallei'' is a Gram-negative, bipolar, aerobic bacterium, a human and animal pathogen of genus ''Burkholderia'' causing glanders; the Latin name of this disease (''malleus'') gave its name to the species causing it. It is closely re ...

,'' and ''Burkholderia pseudomallei

''Burkholderia pseudomallei'' (also known as ''Pseudomonas pseudomallei'') is a Gram-negative, bipolar, aerobic, motile rod-shaped bacterium. It is a soil-dwelling bacterium endemic in tropical and subtropical regions worldwide, particularly in T ...

'' which have been shown to exhibit genome-wide rearrangements due to insertion sequences Insertion element (also known as an IS, an insertion sequence element, or an IS element) is a short DNA sequence that acts as a simple transposable element. Insertion sequences have two major characteristics: they are small relative to other transp ...

and repetitive DNA segments. At this time, no studies demonstrate genome-wide rearrangement events directly giving rise to pathogenic behavior in a microbe. This does not mean it is not possible. Genome-wide rearrangements do, however, contribute to the plasticity of bacterial genome, which may prime the conditions for other factors to introduce, or lose, virulence factors.

= Single-nucleotide polymorphisms

=Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms

In genetics, a single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP ; plural SNPs ) is a germline substitution of a single nucleotide at a specific position in the genome. Although certain definitions require the substitution to be present in a sufficiently larg ...

, or SNPs, allow for a wide array of genetic variation among humans as well as pathogens. They allow researchers to estimate a variety of factors: the effects of environmental toxins, how different treatment methods affect the body, and what causes someone's predisposition to illnesses. SNPs play a key role in understanding how and why mutations occur. SNPs also allows for scientists to map genomes and analyze genetic information.

Pan and core genomes

Pan-genome overview The most recent definition of a bacterial species comes from the pre-genomic era. In 1987, it was proposed that bacterial strains showing >70% DNA·DNA re-association and sharing characteristic phenotypic traits should be considered to be strains of the same species. The diversity within pathogen genomes makes it difficult to identify the total number of genes that are associated within all strains of a pathogen species. It has been thought that the total number of genes associated with a single pathogen species may be unlimited, although some groups are attempting to derive a more empirical value. For this reason, it was necessary to introduce the concept of

Pan-genome overview The most recent definition of a bacterial species comes from the pre-genomic era. In 1987, it was proposed that bacterial strains showing >70% DNA·DNA re-association and sharing characteristic phenotypic traits should be considered to be strains of the same species. The diversity within pathogen genomes makes it difficult to identify the total number of genes that are associated within all strains of a pathogen species. It has been thought that the total number of genes associated with a single pathogen species may be unlimited, although some groups are attempting to derive a more empirical value. For this reason, it was necessary to introduce the concept of pan-genome

In the fields of molecular biology and genetics, a pan-genome (pangenome or supragenome) is the entire set of genes from all strains within a clade. More generally, it is the union of all the genomes of a clade. The pan-genome can be broken d ...

s and core genomes. Pan-genome and core genome literature also tends to have a bias towards reporting on prokaryotic pathogenic organisms. Caution may need to be exercised when extending the definition of a pan-genome or a core-genome to the other pathogenic organisms because there is no formal evidence of the properties of these pan-genomes.

A core genome is the set of genes found across all strains of a pathogen species. A pan-genome is the entire gene pool for that pathogen species, and includes genes that are not shared by all strains. Pan-genomes may be open or closed depending on whether comparative analysis of multiple strains reveals no new genes (closed) or many new genes (open) compared to the core genome for that pathogen species. In the open pan-genome, genes may be further characterized as dispensable or strain specific. Dispensable genes are those found in more than one strain, but not in all strains, of a pathogen species. Strain specific genes are those found only in one strain of a pathogen species. The differences in pan-genomes are reflections of the life style of the organism. For example, ''Streptococcus agalactiae

''Streptococcus agalactiae'' (also known as group B streptococcus or GBS) is a gram-positive coccus (round bacterium) with a tendency to form chains (as reflected by the genus name ''Streptococcus''). It is a beta-hemolytic, catalase-negative, a ...

'', which exists in diverse biological niches, has a broader pan-genome when compared with the more environmentally isolated ''Bacillus anthracis

''Bacillus anthracis'' is a gram-positive and rod-shaped bacterium that causes anthrax, a deadly disease to livestock and, occasionally, to humans. It is the only permanent ( obligate) pathogen within the genus ''Bacillus''. Its infection is a ...

''. Comparative genomics

Comparative genomics is a field of biological research in which the genomic features of different organisms are compared. The genomic features may include the DNA sequence, genes, gene order, regulatory sequences, and other genomic structural lan ...

approaches are also being used to understand more about the pan-genome. Recent discoveries show that the number of new species continue to grow with an estimated 1031 bacteriophages on the planet with those bacteriophages infecting 1024 others per second, the continuous flow of genetic material being exchanged is difficult to imagine.

Virulence factors

Multiple genetic elements of human-affecting pathogens contribute to the transfer of virulence factors:plasmids

A plasmid is a small, extrachromosomal DNA molecule within a cell that is physically separated from chromosomal DNA and can replicate independently. They are most commonly found as small circular, double-stranded DNA molecules in bacteria; how ...

, pathogenicity island Pathogenicity islands (PAIs), as termed in 1990, are a distinct class of genomic islands acquired by microorganisms through horizontal gene transfer. Pathogenicity islands are found in both animal and plant pathogens. Additionally, PAIs are found i ...

, prophages A prophage is a bacteriophage (often shortened to "phage") genome that is integrated into the circular bacterial chromosome or exists as an extrachromosomal plasmid within the bacterial cell (biology), cell. Integration of prophages into the bacteri ...

, bacteriophages, transposons, and integrative and conjugative elements. Pathogenicity islands and their detection are the focus of several bioinformatics efforts involved in pathogenomics. It is a common belief that "environmental bacterial strains" lack the capacity to harm or do damage to humans. However, recent studies show that bacteria from aquatic environments have acquired pathogenic strains through evolution. This allows for the bacteria to have a wider range in genetic traits and can cause a potential threat to humans from which there is more resistance towards antibiotics.

Microbe-microbe interactions

Microbe-host interactions tend to overshadow the consideration of microbe-microbe interactions. Microbe-microbe interactions though can lead to chronic states of infirmity that are difficult to understand and treat.

Microbe-host interactions tend to overshadow the consideration of microbe-microbe interactions. Microbe-microbe interactions though can lead to chronic states of infirmity that are difficult to understand and treat.

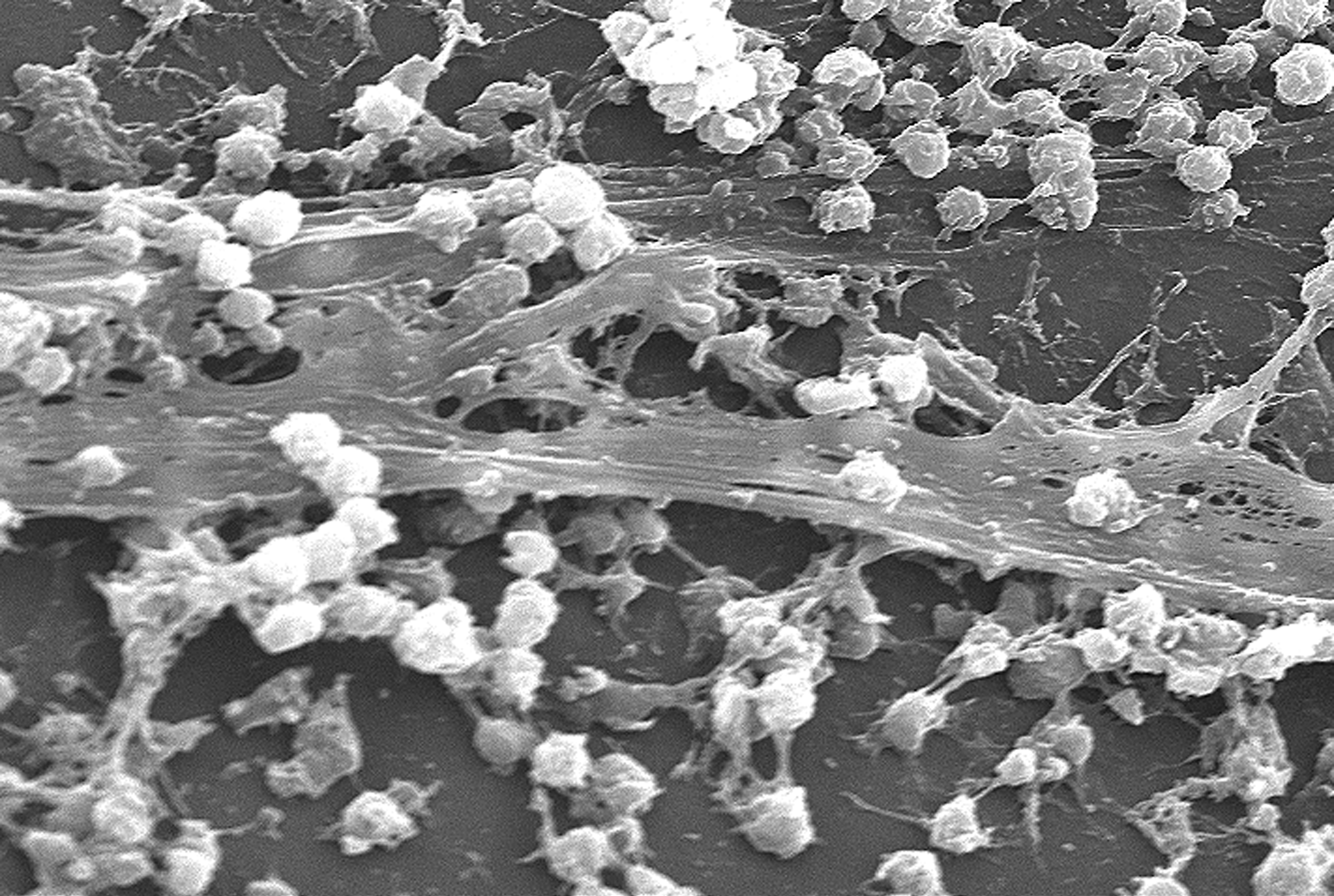

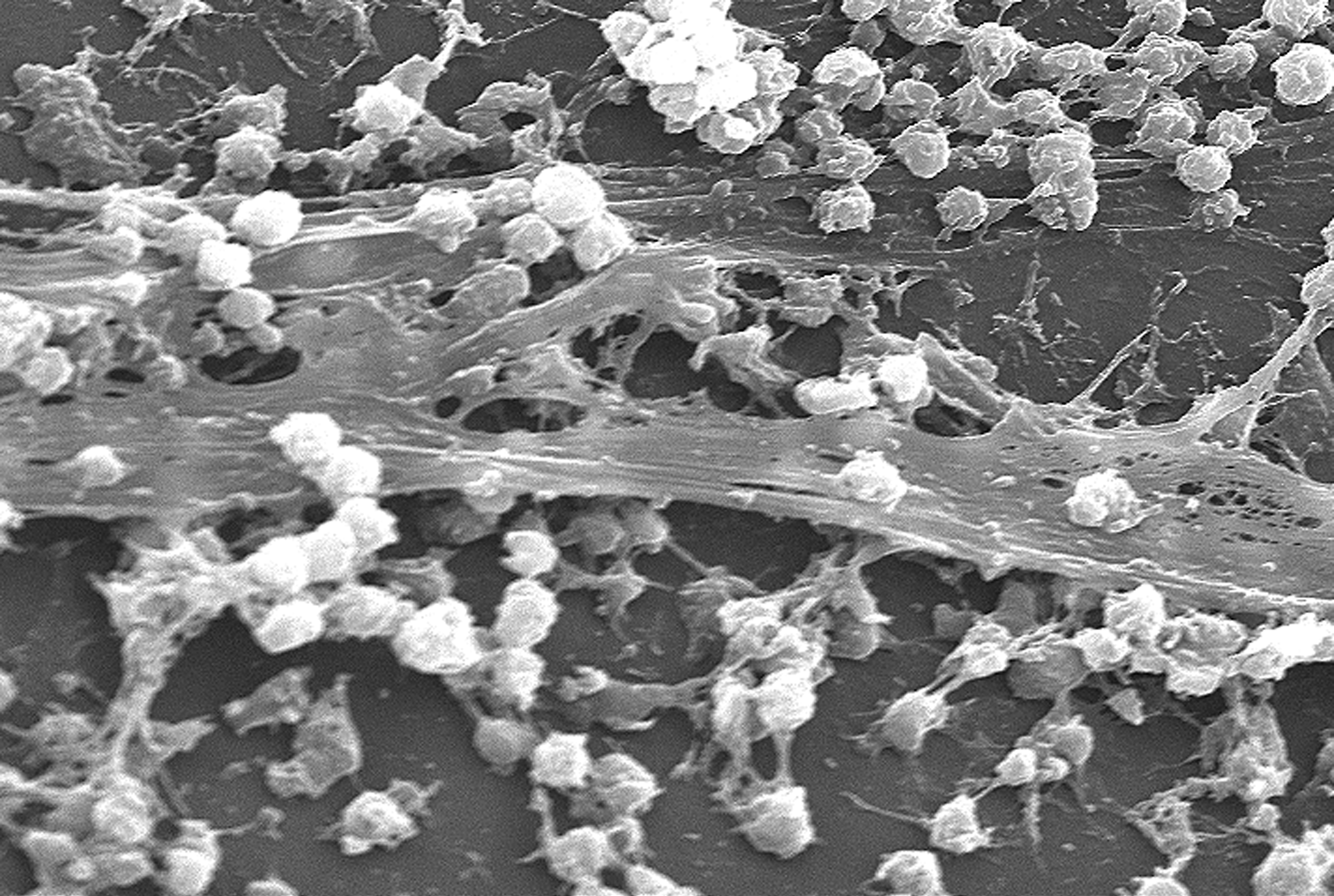

Biofilms

Biofilms

A biofilm comprises any syntrophic consortium of microorganisms in which cells stick to each other and often also to a surface. These adherent cells become embedded within a slimy extracellular matrix that is composed of extracellular ...

are an example of microbe-microbe interactions and are thought to be associated with up to 80% of human infections. Recently it has been shown that there are specific genes and cell surface proteins involved in the formation of biofilm. These genes and also surface proteins may be characterized through in silico

In biology and other experimental sciences, an ''in silico'' experiment is one performed on computer or via computer simulation. The phrase is pseudo-Latin for 'in silicon' (correct la, in silicio), referring to silicon in computer chips. It ...

methods to form an expression profile of biofilm-interacting bacteria. This expression profile may be used in subsequent analysis of other microbes to predict biofilm microbe behaviour, or to understand how to dismantle biofilm formation.

Host microbe analysis

Pathogens have the ability to adapt and manipulate host cells, taking full advantage of a host cell's cellular processes and mechanisms. A microbe may be influenced by hosts to either adapt to its new environment or learn to evade it. An insight into these behaviours will provide beneficial insight for potential therapeutics. The most detailed outline of host-microbe interaction initiatives is outlined by the Pathogenomics European Research Agenda. Its report emphasizes the following features: * ''Microarray analysis of host and microbe gene expression during infection''. This is important for identifying the expression of virulence factors that allow a pathogen to survive a host's defense mechanism. Pathogens tend to undergo an assortment of changed in order to subvert and hosts immune system, in some case favoring a hyper variable genome state. The genomic expression studies will be complemented with protein-protein interaction networks studies.

* ''Using RNA interference (RNAi) to identify host cell functions in response to infections''. Infection depends on the balance between the characteristics of the host cell and the pathogen cell. In some cases, there can be an overactive host response to infection, such as in meningitis, which can overwhelm the host's body. Using RNA, it will be possible to more clearly identify how a host cell defends itself during times of acute or chronic infection. This has also been applied successfully is Drosophila.

* ''Not all microbe interactions in host environment are malicious. ''

* ''Microarray analysis of host and microbe gene expression during infection''. This is important for identifying the expression of virulence factors that allow a pathogen to survive a host's defense mechanism. Pathogens tend to undergo an assortment of changed in order to subvert and hosts immune system, in some case favoring a hyper variable genome state. The genomic expression studies will be complemented with protein-protein interaction networks studies.

* ''Using RNA interference (RNAi) to identify host cell functions in response to infections''. Infection depends on the balance between the characteristics of the host cell and the pathogen cell. In some cases, there can be an overactive host response to infection, such as in meningitis, which can overwhelm the host's body. Using RNA, it will be possible to more clearly identify how a host cell defends itself during times of acute or chronic infection. This has also been applied successfully is Drosophila.

* ''Not all microbe interactions in host environment are malicious. '' Commensal

Commensalism is a long-term biological interaction (symbiosis) in which members of one species gain benefits while those of the other species neither benefit nor are harmed. This is in contrast with mutualism, in which both organisms benefit fro ...

flora, which exists in various environments in animals and humans may actually help combating microbial infections. The human flora

The human microbiome is the aggregate of all microbiota that reside on or within human tissues and biofluids along with the corresponding anatomical sites in which they reside, including the skin, mammary glands, seminal fluid, uterus, ovarian ...

, such as the gut for example, is home to a myriad of microbes.

The diverse community within the gut has been heralded to be vital for human health. There are a number of projects under way to better understand the ecosystems of the gut. The sequence of commensal ''Escherichia coli

''Escherichia coli'' (),Wells, J. C. (2000) Longman Pronunciation Dictionary. Harlow ngland Pearson Education Ltd. also known as ''E. coli'' (), is a Gram-negative, facultative anaerobic, rod-shaped, coliform bacterium of the genus ''Escher ...

'' strain SE11, for example, has already been determined from the faecal matter of a healthy human and promises to be the first of many studies. Through genomic analysis and also subsequent protein analysis, a better understanding of the beneficial properties of commensal flora will be investigated in hopes of understanding how to build a better therapeutic.

Eco-evo perspective

The "eco-evo" perspective on pathogen-host interactions emphasizes the influences ecology and the environment on pathogen evolution. The dynamic genomic factors such as gene loss, gene gain and genome rearrangement, are all strongly influenced by changes in the ecological niche where a particular microbial strain resides. Microbes may switch from being pathogenic and non-pathogenic due to changing environments. This was demonstrated during studies of the plague,Yersinia pestis

''Yersinia pestis'' (''Y. pestis''; formerly '' Pasteurella pestis'') is a gram-negative, non-motile, coccobacillus bacterium without spores that is related to both ''Yersinia pseudotuberculosis'' and ''Yersinia enterocolitica''. It is a facult ...

, which apparently evolved from a mild gastrointestinal pathogen to a very highly pathogenic microbe through dynamic genomic events. In order for colonization to occur, there must be changes in biochemical makeup to aid survival in a variety of environments. This is most likely due to a mechanism allowing the cell to sense changes within the environment, thus influencing change in gene expression. Understanding how these strain changes occur from being low or non-pathogenic to being highly pathogenic and vice versa may aid in developing novel therapeutics for microbial infections.

Applications

Human health has greatly improved and the mortality rate has declined substantially since the second world war because of improved hygiene due to changing public health regulations, as well as more readily available vaccines and antibiotics. Pathogenomics will allow scientists to expand what they know about pathogenic and non-pathogenic microbes, thus allowing for new and improved vaccines. Pathogenomics also has wider implication, including preventing bioterrorism.

Human health has greatly improved and the mortality rate has declined substantially since the second world war because of improved hygiene due to changing public health regulations, as well as more readily available vaccines and antibiotics. Pathogenomics will allow scientists to expand what they know about pathogenic and non-pathogenic microbes, thus allowing for new and improved vaccines. Pathogenomics also has wider implication, including preventing bioterrorism.

Reverse vaccinology

Reverse vaccinology

Reverse vaccinology is an improvement of vaccinology that employs bioinformatics and reverse pharmacology practices, pioneered by Rino Rappuoli and first used against Serogroup B meningococcus. Since then, it has been used on several other bact ...

is relatively new. While research is still being conducted, there have been breakthroughs with pathogens such as ''Streptococcus'' and ''Meningitis''. Methods of vaccine production, such as biochemical and serological, are laborious and unreliable. They require the pathogens to be in vitro

''In vitro'' (meaning in glass, or ''in the glass'') studies are performed with microorganisms, cells, or biological molecules outside their normal biological context. Colloquially called "test-tube experiments", these studies in biology an ...

to be effective. New advances in genomic development help predict nearly all variations of pathogens, thus making advances for vaccines. Protein-based vaccines are being developed to combat resistant pathogens such as ''Staphylococcus'' and ''Chlamydia''.

Countering bioterrorism

In 2005, the sequence of the 1918Spanish influenza

The 1918–1920 influenza pandemic, commonly known by the misnomer Spanish flu or as the Great Influenza epidemic, was an exceptionally deadly global influenza pandemic caused by the H1N1 influenza A virus. The earliest documented case was ...

was completed. Accompanied with phylogenetic

In biology, phylogenetics (; from Greek φυλή/ φῦλον [] "tribe, clan, race", and wikt:γενετικός, γενετικός [] "origin, source, birth") is the study of the evolutionary history and relationships among or within groups o ...

analysis, it was possible to supply a detailed account of the virus' evolution and behavior, in particular its adaptation to humans. Following the sequencing of the Spanish influenza, the pathogen was also reconstructed. When inserted into mice, the pathogen proved to be incredibly deadly. The 2001 anthrax attacks

The 2001 anthrax attacks, also known as Amerithrax (a portmanteau of "America" and "anthrax", from its FBI case name), occurred in the United States over the course of several weeks beginning on September 18, 2001, one week after the September 11 ...

shed light on the possibility of bioterrorism

Bioterrorism is terrorism involving the intentional release or dissemination of biological agents. These agents are bacteria, viruses, insects, fungi, and/or toxins, and may be in a naturally occurring or a human-modified form, in much the same ...

as being more of a real than imagined threat. Bioterrorism was anticipated in the Iraq war, with soldiers being inoculated for a smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

attack. Using technologies and insight gained from reconstruction of the Spanish influenza, it may be possible to prevent future deadly planted outbreaks of disease. There is a strong ethical concern however, as to whether the resurrection of old viruses is necessary and whether it does more harm than good. The best avenue for countering such threats is coordinating with organizations which provide immunizations. The increased awareness and participation would greatly decrease the effectiveness of a potential epidemic. An addition to this measure would be to monitor natural water reservoirs as a basis to prevent an attack or outbreak. Overall, communication between labs and large organizations, such as Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network (GOARN), can lead to early detection and prevent outbreaks.

See also

*References

{{Use dmy dates, date=August 2019 Microbiology Pathogen genomics