Passer Ammodendri on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The saxaul sparrow (''Passer ammodendri'') is a

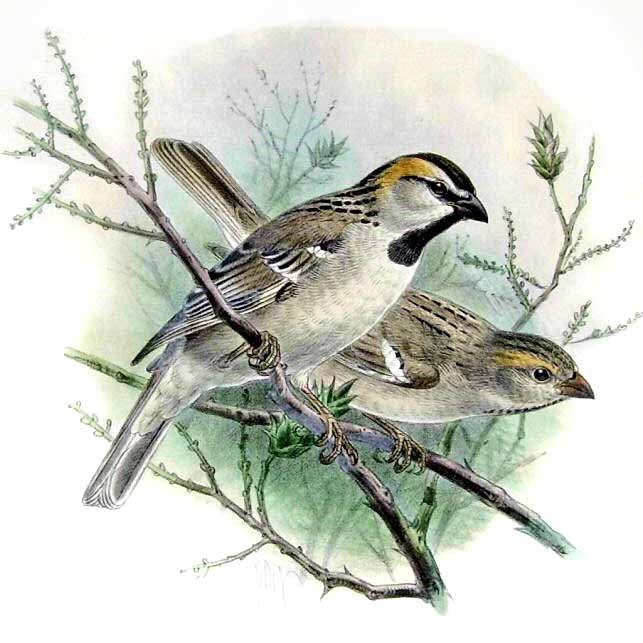

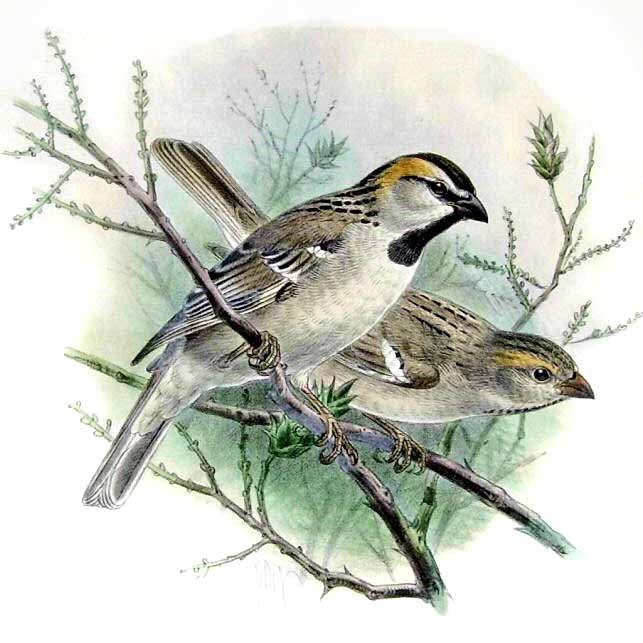

The saxaul sparrow is one of the larger sparrows at and . Wing length varies from , with males generally being larger. The tail is short at . The saxaul sparrow's legs are pale or pinkish brown, with a tarsus length of . Its bill is long, pale grey on the juvenile, pale yellowish with a black tip on the breeding female, and black on the breeding male. Like all other sparrows, it flies swiftly and often at height.

Distinctive markings, especially on its head, make the saxaul sparrow unlikely to be confused with any other bird. It is dull-coloured, with plumage ranging between dull grey and warm sandy brown, varying between and within subspecies. Birds of the subspecies ''ammodendri'' are a sandy grey, while ''nigricans'' birds are similar but darker, and ''stoliczkae'' birds are warm brown or russet. Birds of the subspecies ''stoliczkae'' and those from the southwest of the range of ''ammodendri'' also differ from usual ''ammodendri'' birds in their lack of streaking on the

The saxaul sparrow is one of the larger sparrows at and . Wing length varies from , with males generally being larger. The tail is short at . The saxaul sparrow's legs are pale or pinkish brown, with a tarsus length of . Its bill is long, pale grey on the juvenile, pale yellowish with a black tip on the breeding female, and black on the breeding male. Like all other sparrows, it flies swiftly and often at height.

Distinctive markings, especially on its head, make the saxaul sparrow unlikely to be confused with any other bird. It is dull-coloured, with plumage ranging between dull grey and warm sandy brown, varying between and within subspecies. Birds of the subspecies ''ammodendri'' are a sandy grey, while ''nigricans'' birds are similar but darker, and ''stoliczkae'' birds are warm brown or russet. Birds of the subspecies ''stoliczkae'' and those from the southwest of the range of ''ammodendri'' also differ from usual ''ammodendri'' birds in their lack of streaking on the

Across its Central Asian distribution, the saxaul sparrow occurs in six probably disjunct areas, and is divided into at least three subspecies. The

Across its Central Asian distribution, the saxaul sparrow occurs in six probably disjunct areas, and is divided into at least three subspecies. The

Little is known of the saxaul sparrow's behaviour, because of its remote range. It is shy in many areas, and spends much time hidden in foliage, but breeding birds in Mongolia were reported to be "quite confiding". When not breeding, it is social, and can form flocks of up to fifty birds, sometimes associating with Eurasian tree, Spanish, and house sparrows. In some regions, it makes small local migrations. Towards the spring, saxaul sparrows form pairs within their flock, before dispersing in April. Seeds, especially those of the saxaul, are most of its diet, though it also eats insects, especially while breeding, most commonly

Little is known of the saxaul sparrow's behaviour, because of its remote range. It is shy in many areas, and spends much time hidden in foliage, but breeding birds in Mongolia were reported to be "quite confiding". When not breeding, it is social, and can form flocks of up to fifty birds, sometimes associating with Eurasian tree, Spanish, and house sparrows. In some regions, it makes small local migrations. Towards the spring, saxaul sparrows form pairs within their flock, before dispersing in April. Seeds, especially those of the saxaul, are most of its diet, though it also eats insects, especially while breeding, most commonly

Saxaul sparrow

at the Internet Bird Collection

Saxaul sparrow

at Birds of Kazakhstan

Recording of the saxaul sparrow's songSaxaul sparrow

at Oriental Bird Images {{featured article

passerine

A passerine () is any bird of the order Passeriformes (; from Latin 'sparrow' and '-shaped'), which includes more than half of all bird species. Sometimes known as perching birds, passerines are distinguished from other orders of birds by t ...

bird of the sparrow

Sparrow may refer to:

Birds

* Old World sparrows, family Passeridae

* New World sparrows, family Passerellidae

* two species in the Passerine family Estrildidae:

** Java sparrow

** Timor sparrow

* Hedge sparrow, also known as the dunnock or hedg ...

family

Family (from la, familia) is a Social group, group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or Affinity (law), affinity (by marriage or other relationship). The purpose of the family is to maintain the well-being of its ...

Passeridae, found in parts of Central Asia

Central Asia, also known as Middle Asia, is a subregion, region of Asia that stretches from the Caspian Sea in the west to western China and Mongolia in the east, and from Afghanistan and Iran in the south to Russia in the north. It includes t ...

. At and , it is among the larger sparrows. Both sexes have plumage

Plumage ( "feather") is a layer of feathers that covers a bird and the pattern, colour, and arrangement of those feathers. The pattern and colours of plumage differ between species and subspecies and may vary with age classes. Within species, ...

ranging from dull grey to sandy brown, and pale brown legs. Females have less boldly coloured plumage and bills, lacking the pattern of black stripes on the male's head. The head markings of both sexes make the saxaul sparrow distinctive, and unlikely to be confused with any other bird. Vocalisations include a comparatively soft and musical chirping call, a song, and a flight call Flight calls are vocalisations made by bird

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the laying of hard-shelled eggs, a high metabolic rate, a fou ...

.

Three subspecies

In biological classification, subspecies is a rank below species, used for populations that live in different areas and vary in size, shape, or other physical characteristics (morphology), but that can successfully interbreed. Not all species ...

are recognised, differing in the overall tone of their plumage and in the head striping of the female. The subspecies ''ammodendri'' occurs in the west of the saxaul sparrow's range, while ''stoliczkae'' and ''nigricans'' occur in the east. This distribution falls into six probably disjunct areas across Central Asia, from central Turkmenistan

Turkmenistan ( or ; tk, Türkmenistan / Түркменистан, ) is a country located in Central Asia, bordered by Kazakhstan to the northwest, Uzbekistan to the north, east and northeast, Afghanistan to the southeast, Iran to the sout ...

to northern Gansu

Gansu (, ; alternately romanized as Kansu) is a province in Northwest China. Its capital and largest city is Lanzhou, in the southeast part of the province.

The seventh-largest administrative district by area at , Gansu lies between the Tibet ...

in China. A bird of deserts, the saxaul sparrow favours areas with shrubs such as the saxaul, near rivers and oases. Though it has lost parts of its range to habitat destruction

Habitat destruction (also termed habitat loss and habitat reduction) is the process by which a natural habitat becomes incapable of supporting its native species. The organisms that previously inhabited the site are displaced or dead, thereby ...

caused by agriculture, it is not seriously threatened by human activities.

Little is known of the saxaul sparrow's behaviour. Often hidden in foliage, it forages in trees and on the ground. It feeds mostly on seeds, as well as insects while breeding and as a nestling. When not breeding it forms wandering flocks, but it is less social than other sparrows while breeding, often nesting in isolated pairs. Nests are round bundles of dry plant material lined with soft materials such as feathers. They are built in holes in tree cavities, earth banks, rocky slopes, and within man-made structures or the nests of birds of prey. Two clutches

A clutch is a mechanical device that engages and disengages power transmission, especially from a drive shaft to a driven shaft. In the simplest application, clutches connect and disconnect two rotating shafts (drive shafts or line shafts). ...

of five or six eggs are typically laid in a season. Both parents construct the nest and care for their eggs and young.

Description

The saxaul sparrow is one of the larger sparrows at and . Wing length varies from , with males generally being larger. The tail is short at . The saxaul sparrow's legs are pale or pinkish brown, with a tarsus length of . Its bill is long, pale grey on the juvenile, pale yellowish with a black tip on the breeding female, and black on the breeding male. Like all other sparrows, it flies swiftly and often at height.

Distinctive markings, especially on its head, make the saxaul sparrow unlikely to be confused with any other bird. It is dull-coloured, with plumage ranging between dull grey and warm sandy brown, varying between and within subspecies. Birds of the subspecies ''ammodendri'' are a sandy grey, while ''nigricans'' birds are similar but darker, and ''stoliczkae'' birds are warm brown or russet. Birds of the subspecies ''stoliczkae'' and those from the southwest of the range of ''ammodendri'' also differ from usual ''ammodendri'' birds in their lack of streaking on the

The saxaul sparrow is one of the larger sparrows at and . Wing length varies from , with males generally being larger. The tail is short at . The saxaul sparrow's legs are pale or pinkish brown, with a tarsus length of . Its bill is long, pale grey on the juvenile, pale yellowish with a black tip on the breeding female, and black on the breeding male. Like all other sparrows, it flies swiftly and often at height.

Distinctive markings, especially on its head, make the saxaul sparrow unlikely to be confused with any other bird. It is dull-coloured, with plumage ranging between dull grey and warm sandy brown, varying between and within subspecies. Birds of the subspecies ''ammodendri'' are a sandy grey, while ''nigricans'' birds are similar but darker, and ''stoliczkae'' birds are warm brown or russet. Birds of the subspecies ''stoliczkae'' and those from the southwest of the range of ''ammodendri'' also differ from usual ''ammodendri'' birds in their lack of streaking on the rump

Rump may refer to:

* Rump (animal)

** Buttocks

* Rump steak, slightly different cuts of meat in Britain and America

* Rump kernel, software run in userspace that offers kernel functionality in NetBSD

Politics

*Rump cabinet

* Rump legislature

* Ru ...

and upper tail coverts

A covert feather or tectrix on a bird is one of a set of feathers, called coverts (or ''tectrices''), which, as the name implies, cover other feathers. The coverts help to smooth airflow over the wings and tail. Ear coverts

The ear coverts are sm ...

. Birds in Mongolia have a larger and deeper bill and broad bluish streaks on their chest.

The male saxaul sparrow has bold markings, with a black stripe along the top of its head and another through its eye. It has black feathering, or a "bib", on its throat and upper belly. By comparison to other sparrows this is thin on the throat, but wide on the breast. The male has a bright russet patch on the sides of its crown and nape. Its cheeks are pale grey or buff

Buff or BUFF may refer to:

People

* Buff (surname), a list of people

* Buff (nickname), a list of people

* Johnny Buff, ring name of American world champion boxer John Lisky (1888–1955)

* Buff Bagwell, a ring name of American professional wr ...

, and its underparts are whitish, tinged buff or grey on its sides. Its back is grey or warm brown, streaked variably with black. Its shoulders are more lightly streaked with black bars. The male's thin tail is brown, with the edges and tips of feathers paler. Its median coverts are black with a white tip, while its other wing feathers are variably dark brown, cinnamon, or black, tipped buff or whitish and edged grey. The non-breeding male differs in having slightly paler plumage.

The female is similar in some ways to the male, but paler and duller. It is sandy grey or brown, with a back patterned like that of the male, and white or whitish underparts. The head of the females of the subspecies ''ammodendri'' and ''nigricans'' is dingy grey with darker smudges on the forehead, behind its eyes, and on its throat. The female of the subspecies ''stoliczkae'' is buff-brown with a white throat, a conspicuous pale supercilium

The supercilium is a plumage feature found on the heads of some bird species. It is a stripe which runs from the base of the bird's beak above its eye, finishing somewhere towards the rear of the bird's head.Dunn and Alderfer (2006), p. 10 Also ...

, darker forehead, and lighter cheeks. The juvenile is similar to the female, differing in its lack of dark tinges on its throat and crown. In adults, moulting

In biology, moulting (British English), or molting (American English), also known as sloughing, shedding, or in many invertebrates, ecdysis, is the manner in which an animal routinely casts off a part of its body (often, but not always, an outer ...

begins in July and ends in late August or early September. The post-juvenile moult is complete, and occurs variously from June to August.

The saxaul sparrow's vocalisations are little reported. Its common call is a chirp, transcribed as , softer and more melodious than that of the house sparrow

The house sparrow (''Passer domesticus'') is a bird of the sparrow family Passeridae, found in most parts of the world. It is a small bird that has a typical length of and a mass of . Females and young birds are coloured pale brown and grey, a ...

. It gives a flight call Flight calls are vocalisations made by bird

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the laying of hard-shelled eggs, a high metabolic rate, a fou ...

transcribed as ''twerp'', and a song described by Russian naturalist V. N. Shnitnikov as "not loud, but pleasantly melodious with fairly diversified intonations".

Taxonomy

The saxaul sparrow was first described by English zoologist John Gould in a March 1872 instalment of ''The Birds of Asia'', from a specimen collected near Kyzylorda, now in southernKazakhstan

Kazakhstan, officially the Republic of Kazakhstan, is a transcontinental country located mainly in Central Asia and partly in Eastern Europe. It borders Russia to the north and west, China to the east, Kyrgyzstan to the southeast, Uzbeki ...

, by Russian naturalist Nikolai Severtzov

Nikolai Alekseevich Severtzov (5 November 1827 – 8 February 1885) was a Russian explorer and naturalist.

Severtzov studied at the Moscow University and at the age of eighteen he came into contact with G. S. Karelin and took an interest i ...

. Severtzov had been planning to describe the species as ''Passer ammodendri'' for several years and had been distributing specimens among other naturalists. When natural history dealer Charles Dode escaped from the Paris Commune

The Paris Commune (french: Commune de Paris, ) was a revolutionary government that seized power in Paris, the capital of France, from 18 March to 28 May 1871.

During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71, the French National Guard had defended ...

in 1871 with some of his collection, Gould obtained specimens from a set of rare birds Dode exhibited to the Zoological Society of London

The Zoological Society of London (ZSL) is a charity devoted to the worldwide conservation of animals and their habitats. It was founded in 1826. Since 1828, it has maintained the London Zoo, and since 1931 Whipsnade Park.

History

On 29 ...

. Severtzov did not describe the species until 1873, and some later writers preferred to attribute him, but Gould's description takes priority over Severtzov's. The saxaul sparrow's species name refers to its desert habitat, coming from the name of the '' Ammodendron'' or sand acacia tree, which is in turn derived from the Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic peri ...

'' άμμος'' (''ammos'', "sand") and '' δένδρον'' (''dendron'', "tree"). The English name ''saxaul sparrow'' refers to the saxaul plant, with which it is closely associated. The saxaul sparrow usually is classified in the genus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of extant taxon, living and fossil organisms as well as Virus classification#ICTV classification, viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus com ...

'' Passer'' with the house sparrow and around twenty other species, although a genus ''Ammopasser'' was created for the saxaul sparrow by Nikolai Zarudny

Nikolai Alekseyvich Zarudny (russian: Николай Алексеевич Зарудный; rus, Николай Алексеевич Зарудный, r=Nikolay Alekseevich Zarudny. His name has been transliterated a number of other ways; especial ...

in 1890.

The saxaul sparrow's relations within the genus ''Passer'' are unclear, although with its black throat feathering it has usually been considered part of the "Palaearctic black-bibbed sparrow" group related to the house sparrow. J. Denis Summers-Smith

James Denis Summers-Smith (25 October 1920 – 5 May 2020) was a British ornithologist and mechanical engineer, a specialist both in sparrows and in industrial tribology.

Early life

Summers-Smith was raised in Glasgow, where he was born in ...

considered that the Palaearctic ''Passer'' sparrows evolved about 25,000 to 15,000 years ago, during the last glacial period. During this time, sparrows would have been isolated in ice-free refugia, such as a certain steppe region in Central Asia, where Summers-Smith suggested the saxaul sparrow evolved. Genetic and fossil evidence suggest a much earlier origin for the ''Passer'' species, perhaps in the Miocene

The Miocene ( ) is the first geological epoch of the Neogene Period and extends from about (Ma). The Miocene was named by Scottish geologist Charles Lyell; the name comes from the Greek words (', "less") and (', "new") and means "less recen ...

and Pliocene

The Pliocene ( ; also Pleiocene) is the epoch in the geologic time scale that extends from 5.333 million to 2.58phylogenetic

In biology, phylogenetics (; from Greek φυλή/ φῦλον [] "tribe, clan, race", and wikt:γενετικός, γενετικός [] "origin, source, birth") is the study of the evolutionary history and relationships among or within groups o ...

analysis of mitochondrial DNA

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA or mDNA) is the DNA located in mitochondria, cellular organelles within eukaryotic cells that convert chemical energy from food into a form that cells can use, such as adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Mitochondrial D ...

. This analysis also suggested that the saxaul sparrow may be an early offshoot or basal

Basal or basilar is a term meaning ''base'', ''bottom'', or ''minimum''.

Science

* Basal (anatomy), an anatomical term of location for features associated with the base of an organism or structure

* Basal (medicine), a minimal level that is nec ...

species in its genus, a relative of certain African sparrows such as the northern grey-headed sparrow

The northern grey-headed sparrow (''Passer griseus''), also known as the grey-headed sparrow, is a species of bird in the sparrow family Passeridae, which is resident in much of tropical Africa. It occurs in a wide range of open habitats, includ ...

. If the saxaul sparrow is related to these species, either the saxaul sparrow formerly occurred in the deserts of Africa and Arabia, or each of the groups of ''Passer'' sparrows are of African origin.

nominate subspecies

In biological classification, subspecies is a rank below species, used for populations that live in different areas and vary in size, shape, or other physical characteristics (morphology), but that can successfully interbreed. Not all species ...

''Passer ammodendri ammodendri'' inhabits three of these areas, one in the Syr Darya

The Syr Darya (, ),, , ; rus, Сырдарья́, Syrdarjja, p=sɨrdɐˈrʲja; fa, سيردريا, Sirdaryâ; tg, Сирдарё, Sirdaryo; tr, Seyhun, Siri Derya; ar, سيحون, Seyḥūn; uz, Sirdaryo, script-Latn/. historically known ...

basin of Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan (, ; uz, Ozbekiston, italic=yes / , ; russian: Узбекистан), officially the Republic of Uzbekistan ( uz, Ozbekiston Respublikasi, italic=yes / ; russian: Республика Узбекистан), is a doubly landlocked cou ...

, and another to the south of Lake Balkhash

Lake Balkhash ( kk, Балқаш көлі, ''Balqaş kóli'', ; russian: озеро Балхаш, ozero Balkhash) is a lake in southeastern Kazakhstan, one of the largest lakes in Asia and the 15th largest in the world. It is located in the ea ...

and the north of Almaty

Almaty (; kk, Алматы; ), formerly known as Alma-Ata ( kk, Алма-Ата), is the List of most populous cities in Kazakhstan, largest city in Kazakhstan, with a population of about 2 million. It was the capital of Kazakhstan from 1929 to ...

, where it is only common in the valley of the Ili River

The Ili ( ug, ئىلى دەرياسى, Ili deryasi, Ili dəryasi, 6=Или Дәряси; kk, Ile, ; russian: Или; zh, c=伊犁河, p=Yīlí Hé, dng, Йили хә, Xiao'erjing: اِلِ حْ; mn, Ил, literally "Bareness") is a river sit ...

. In a third area, sometimes recognised as a subspecies ''korejewi'', ''ammodendri'' birds breed sporadically in parts of central Turkmenistan

Turkmenistan ( or ; tk, Türkmenistan / Түркменистан, ) is a country located in Central Asia, bordered by Kazakhstan to the northwest, Uzbekistan to the north, east and northeast, Afghanistan to the southeast, Iran to the sout ...

, Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

, and possibly Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is bordere ...

, migrating to the south during the winter. The subspecies ''stoliczkae'' was named after Ferdinand Stoliczka

Ferdinand Stoliczka (Czech written Stolička, 7 June 1838 – 19 June 1874) was a Moravian palaeontologist who worked in India on paleontology, geology and various aspects of zoology, including ornithology, malacology, and herpetology. He died of ...

in 1874 by Allan Octavian Hume, from specimens Stoliczka collected in Yarkand

Yarkant County,, United States National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency also Shache County,, United States National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency also transliterated from Uyghur as Yakan County, is a county in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous ...

. This subspecies is separated from the other two subspecies by the Tian Shan

The Tian Shan,, , otk, 𐰴𐰣 𐱅𐰭𐰼𐰃, , tr, Tanrı Dağı, mn, Тэнгэр уул, , ug, تەڭرىتاغ, , , kk, Тәңіртауы / Алатау, , , ky, Теңир-Тоо / Ала-Тоо, , , uz, Tyan-Shan / Tangritog‘ ...

mountains. It is found across a broad swath of China from Kashgar east to the far west of Inner Mongolia

Inner Mongolia, officially the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, is an autonomous region of the People's Republic of China. Its border includes most of the length of China's border with the country of Mongolia. Inner Mongolia also accounts for a ...

, through the areas around the Taklamakan Desert

The Taklimakan or Taklamakan Desert (; zh, s=塔克拉玛干沙漠, p=Tǎkèlāmǎgān Shāmò, Xiao'erjing: , dng, Такәламаган Шамә; ug, تەكلىماكان قۇملۇقى, Täklimakan qumluqi; also spelled Taklimakan and Te ...

(but probably not in the inhospitable desert itself), and through the east of Xinjiang

Xinjiang, SASM/GNC: ''Xinjang''; zh, c=, p=Xīnjiāng; formerly romanized as Sinkiang (, ), officially the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (XUAR), is an autonomous region of the People's Republic of China (PRC), located in the northwest ...

, northern Gansu

Gansu (, ; alternately romanized as Kansu) is a province in Northwest China. Its capital and largest city is Lanzhou, in the southeast part of the province.

The seventh-largest administrative district by area at , Gansu lies between the Tibet ...

, and the fringes of southern Mongolia

Mongolia; Mongolian script: , , ; lit. "Mongol Nation" or "State of Mongolia" () is a landlocked country in East Asia, bordered by Russia to the north and China to the south. It covers an area of , with a population of just 3.3 million, ...

. In the extreme west of the Gobi Desert

The Gobi Desert (Chinese: 戈壁 (沙漠), Mongolian: Говь (ᠭᠣᠪᠢ)) () is a large desert or brushland region in East Asia, and is the sixth largest desert in the world.

Geography

The Gobi measures from southwest to northeast an ...

a disjunct population separated from the other ''stoliczkae'' birds by the Gurvan Saikhan Uul

The Gurvan Saikhan ( mn, Гурван Сайхан, ''lit.'' ''"three beauties"''), is a mountain range in the Ömnögovi Province of southern Mongolia. It is named for three subranges: Baruun Saikhany Nuruu (the ''Western Beauty''), Dund Saikhany ...

mountains occurs, which is sometimes separated as a subspecies ''timidus''. The subspecies ''nigricans'', described by ornithologist L. S. Stepanyan in 1961, is found in northern Xinjiang's Manasi River

The Manasi River (, ug, ماناس دەرياسى also called Manas) is in the south of Dzungarian Basin, Xinjiang, China.

Historically, the Manas River crossed a large section of the Gurbantünggüt Desert, terminating in Lake Manas (); its leng ...

valley.

Habitat

The saxaul sparrow is found in remote parts ofCentral Asia

Central Asia, also known as Middle Asia, is a subregion, region of Asia that stretches from the Caspian Sea in the west to western China and Mongolia in the east, and from Afghanistan and Iran in the south to Russia in the north. It includes t ...

, where its distribution is believed to fall into six disjunct areas, although this is uncertain due to the scarcity of records. It is found in deserts, especially around rivers and oases. It is usually found around shrubs such as saxaul (''Haloxylon

''Haloxylon'' is a genus of shrubs or small trees, belonging to the plant family (biology), family Amaranthaceae. ''Haloxylon'' and its species are known by the common name saxaul.

According to Dmitry Ushakov, the name borrowed from the Kazakh lan ...

''), poplar (''Populus

''Populus'' is a genus of 25–30 species of deciduous flowering plants in the family Salicaceae, native to most of the Northern Hemisphere. English names variously applied to different species include poplar (), aspen, and cottonwood.

The we ...

''), or tamarisk (''Tamarix

The genus ''Tamarix'' (tamarisk, salt cedar, taray) is composed of about 50–60 species of flowering plants in the family Tamaricaceae, native to drier areas of Eurasia and Africa. The generic name originated in Latin and may refer to the Tam ...

''). Sometimes it occurs around settlements and grain fields, especially during the winter. It is not believed to be threatened, since it is reported as locally common across a wide range, and hence it is assessed as Least Concern

A least-concern species is a species that has been categorized by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) as evaluated as not being a focus of species conservation because the specific species is still plentiful in the wild. T ...

on the IUCN Red List

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species, also known as the IUCN Red List or Red Data Book, founded in 1964, is the world's most comprehensive inventory of the global conservation status of biol ...

. However, it seems to have lost large parts of its range to the intensification of agriculture and desertification

Desertification is a type of land degradation in drylands in which biological productivity is lost due to natural processes or induced by human activities whereby fertile areas become increasingly arid. It is the spread of arid areas caused by ...

caused by overgrazing.

Behaviour

Little is known of the saxaul sparrow's behaviour, because of its remote range. It is shy in many areas, and spends much time hidden in foliage, but breeding birds in Mongolia were reported to be "quite confiding". When not breeding, it is social, and can form flocks of up to fifty birds, sometimes associating with Eurasian tree, Spanish, and house sparrows. In some regions, it makes small local migrations. Towards the spring, saxaul sparrows form pairs within their flock, before dispersing in April. Seeds, especially those of the saxaul, are most of its diet, though it also eats insects, especially while breeding, most commonly

Little is known of the saxaul sparrow's behaviour, because of its remote range. It is shy in many areas, and spends much time hidden in foliage, but breeding birds in Mongolia were reported to be "quite confiding". When not breeding, it is social, and can form flocks of up to fifty birds, sometimes associating with Eurasian tree, Spanish, and house sparrows. In some regions, it makes small local migrations. Towards the spring, saxaul sparrows form pairs within their flock, before dispersing in April. Seeds, especially those of the saxaul, are most of its diet, though it also eats insects, especially while breeding, most commonly weevil

Weevils are beetles belonging to the Taxonomic rank, superfamily Curculionoidea, known for their elongated snouts. They are usually small, less than in length, and Herbivore, herbivorous. Approximately 97,000 species of weevils are known. They b ...

s, grasshopper

Grasshoppers are a group of insects belonging to the suborder Caelifera. They are among what is possibly the most ancient living group of chewing herbivorous insects, dating back to the early Triassic around 250 million years ago.

Grasshopp ...

s, and caterpillar

Caterpillars ( ) are the larval stage of members of the order Lepidoptera (the insect order comprising butterflies and moths).

As with most common names, the application of the word is arbitrary, since the larvae of sawflies (suborder Sym ...

s. It forages in trees and on the ground. In a study of insects fed to nestlings in the Ili River

The Ili ( ug, ئىلى دەرياسى, Ili deryasi, Ili dəryasi, 6=Или Дәряси; kk, Ile, ; russian: Или; zh, c=伊犁河, p=Yīlí Hé, dng, Йили хә, Xiao'erjing: اِلِ حْ; mn, Ил, literally "Bareness") is a river sit ...

valley, it was found that beetles are predominant, with weevils and Coccinellidae

Coccinellidae () is a widespread family of small beetles ranging in size from . They are commonly known as ladybugs in North America and ladybirds in Great Britain. Some entomologists prefer the names ladybird beetles or lady beetles as they ...

comprising 60 and 30 percent of the diet of nestlings, respectively. Because of its desert habitat and scarcity, it is not a pest of agriculture. Where water is not available, the saxaul sparrow may fly several times each day over long distances to drink.

The saxaul sparrow is less social than other sparrows while breeding, due to its dry habitat and its choices of nesting locations, holes in trees and earth banks. Isolated pairs are usual, though it sometimes breeds in small groups, with members of its own species as well as house and Eurasian tree sparrows. The breeding season

Seasonal breeders are animal species that successfully mate only during certain times of the year. These times of year allow for the optimization of survival of young due to factors such as ambient temperature, food and water availability, and cha ...

is short, lasting from May to July, with most young raised in April and June. Unusually for a sparrow, it has not been recorded nesting openly in branches, though this may simply represent the lack of published records. Nests are often built in tree cavities, where they are sometimes placed close together. Other common nesting localities are earth banks and rocky slopes, and nests have been recorded on the nests of birds of prey, unused buildings, walls, and electricity pylons. Nests in man-made structures are increasingly common, as large trees in the saxaul sparrow's habitat are removed. Nests may be quite close to the ground, especially when they are built in trees.

The saxaul sparrow's nests are untidy dome-shaped constructions, with an entrance in the side or top. They are built of grass

Poaceae () or Gramineae () is a large and nearly ubiquitous family of monocotyledonous flowering plants commonly known as grasses. It includes the cereal grasses, bamboos and the grasses of natural grassland and species cultivated in lawns an ...

es, root

In vascular plants, the roots are the organs of a plant that are modified to provide anchorage for the plant and take in water and nutrients into the plant body, which allows plants to grow taller and faster. They are most often below the sur ...

s, and other plant materials, and are lined with feathers, fur, and soft plant material. The nest is mainly built by the female, though the male may actively take part in building. Typical clutches

A clutch is a mechanical device that engages and disengages power transmission, especially from a drive shaft to a driven shaft. In the simplest application, clutches connect and disconnect two rotating shafts (drive shafts or line shafts). ...

have five or six eggs, and two clutches a year are normal. Eggs are broad and ovular, slightly pointed at an end. They are glossy, coloured white and shaded with rusty grey or yellowish brown. In some clutches, one egg is noticeably paler than the others. Four eggs collected by Zarudny from Transcaspia

The Transcaspian Oblast (russian: Закаспійская область), or just simply Transcaspia (russian: Закаспія), was the section of Russian Empire and early Soviet Russia to the east of the Caspian Sea during the second half of ...

had an average size of . Females play the main part in incubating eggs, and males can often be seen guarding the nests during incubation. Males and females share in feeding their young, which they do every 4 to 12 minutes. Young that have left their nest remain nearby until well after their moult, before departing for winter flocks, followed later by the adults.

References

Works cited

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

Saxaul sparrow

at the Internet Bird Collection

Saxaul sparrow

at Birds of Kazakhstan

Recording of the saxaul sparrow's song

at Oriental Bird Images {{featured article

saxaul sparrow

The saxaul sparrow (''Passer ammodendri'') is a passerine bird of the Old World sparrow, sparrow family (biology), family Passeridae, found in parts of Central Asia. At and , it is among the larger sparrows. Both sexes have plumage ranging from ...

saxaul sparrow

The saxaul sparrow (''Passer ammodendri'') is a passerine bird of the Old World sparrow, sparrow family (biology), family Passeridae, found in parts of Central Asia. At and , it is among the larger sparrows. Both sexes have plumage ranging from ...

Birds of Central Asia

Birds of Western China

Birds of North China

Birds of Mongolia

saxaul sparrow

The saxaul sparrow (''Passer ammodendri'') is a passerine bird of the Old World sparrow, sparrow family (biology), family Passeridae, found in parts of Central Asia. At and , it is among the larger sparrows. Both sexes have plumage ranging from ...

Taxa named by John Gould