Paryphanta Busbyi on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Paryphanta busbyi'' is a

''The conservation requirements of New Zealand’s nationally threatened invertebrates''

Threatened Species Occasional Publication 20. 658 pp. Page

71-120

The width of the type specimen is 66 × 53 mm, the height of the shell is 29 mm. The

The

The

species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate s ...

of large predatory

Predation is a biological interaction where one organism, the predator, kills and eats another organism, its prey. It is one of a family of common feeding behaviours that includes parasitism and micropredation (which usually do not kill th ...

land snail

A land snail is any of the numerous species of snail that live on land, as opposed to the sea snails and freshwater snails. ''Land snail'' is the common name for terrestrial gastropod mollusks that have shells (those without shells are known as ...

, a terrestrial

Terrestrial refers to things related to land or the planet Earth.

Terrestrial may also refer to:

* Terrestrial animal, an animal that lives on land opposed to living in water, or sometimes an animal that lives on or near the ground, as opposed to ...

pulmonate

Pulmonata or pulmonates, is an informal group (previously an order, and before that a subclass) of snails and slugs characterized by the ability to breathe air, by virtue of having a pallial lung instead of a gill, or gills. The group includ ...

gastropod

The gastropods (), commonly known as snails and slugs, belong to a large taxonomic class of invertebrates within the phylum Mollusca called Gastropoda ().

This class comprises snails and slugs from saltwater, from freshwater, and from land. T ...

mollusk

Mollusca is the second-largest phylum of invertebrate animals after the Arthropoda, the members of which are known as molluscs or mollusks (). Around 85,000 extant species of molluscs are recognized. The number of fossil species is e ...

in the family

Family (from la, familia) is a Social group, group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or Affinity (law), affinity (by marriage or other relationship). The purpose of the family is to maintain the well-being of its ...

Rhytididae

Rhytididae is a taxonomic family of medium-sized predatory air-breathing land snails, carnivorous terrestrial pulmonate gastropod molluscs in the superfamily Rhytidoidea. MolluscaBase eds. (2020). MolluscaBase. Rhytididae Pilsbry, 1893. Accessed ...

.

Distribution

The distribution of ''Paryphanta busbyi'' includes the Northern parts ofNorth Island

The North Island, also officially named Te Ika-a-Māui, is one of the two main islands of New Zealand, separated from the larger but much less populous South Island by the Cook Strait. The island's area is , making it the world's 14th-largest ...

, New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island count ...

: Kaitaia

Kaitaia ( mi, Kaitāia) is a town in the Far North District of New Zealand, at the base of the Aupouri Peninsula, about 160 km northwest of Whangārei. It is the last major settlement on New Zealand State Highway 1, State Highway 1. Ahipara ...

, Hokianga

The Hokianga is an area surrounding the Hokianga Harbour, also known as the Hokianga River, a long estuarine drowned valley on the west coast in the north of the North Island of New Zealand.

The original name, still used by local Māori, is ...

, Mangōnui, Bay of Islands

The Bay of Islands is an area on the east coast of the Far North District of the North Island of New Zealand. It is one of the most popular fishing, sailing and tourist destinations in the country, and has been renowned internationally for its ...

, Otonga East, Mania Hill, Whangārei

Whangārei () is the northernmost city in New Zealand and the regional capital of Northland Region. It is part of the Whangarei District, Whangārei District, a local body created in 1989 from the former Whangārei City, Whangārei County and ...

, Brynderwyn Range

The Brynderwyn Range or Brynderwyn Hills is a ridge extending east–west across the Northland Peninsula in northern New Zealand some 60 kilometres south of Whangārei, from the southern end of Bream Bay in the east to the Otamatea River (an arm ...

, Hen Island, Woodcocks

The woodcocks are a group of seven or eight very similar living species of wading birds in the genus ''Scolopax''. The genus name is Latin for a snipe or woodcock, and until around 1800 was used to refer to a variety of waders. The English name ...

and Warkworth, which is its southern native distribution. Localitions with introduced distribution include Little Huia in Waitākere Ranges

The Waitākere Ranges is a mountain range in New Zealand. Located in West Auckland between metropolitan Auckland and the Tasman Sea, the ranges and its foothills and coasts comprise some of public and private land. The area, traditionally kno ...

, Waiuku

Waiuku is a rural town in the Auckland Region in the North Island of New Zealand. It is located at the southern end of the Waiuku River, which is an estuarial arm of the Manukau Harbour, and lies on the isthmus of the Āwhitu Peninsula, which ...

in Āwhitu Peninsula

The Āwhitu Peninsula is a long peninsula in the North Island of New Zealand, extending north from the mouth of the Waikato River to the entrance to Manukau Harbour.

The Peninsula is bounded in the west by rugged cliffs over the Tasman Sea, but i ...

, and Kaimai Ranges

The Kaimai Range (sometimes referred to as the ''Kaimai Ranges'') is a mountain range in the North Island of New Zealand. It is part of a series of ranges, with the Coromandel Range to the north and the Mamaku Ranges to the south. The Kaimai R ...

.

Its distribution is coincident in range with the kauri

''Agathis'', commonly known as kauri or dammara, is a genus of 22 species of evergreen tree. The genus is part of the ancient conifer family Araucariaceae, a group once widespread during the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods, but now largely res ...

forest.

The type locality is New Zealand. The type specimen is stored in Natural History Museum, London

The Natural History Museum in London is a museum that exhibits a vast range of specimens from various segments of natural history. It is one of three major museums on Exhibition Road in South Kensington, the others being the Science Museum an ...

.

Shell description

Theshell

Shell may refer to:

Architecture and design

* Shell (structure), a thin structure

** Concrete shell, a thin shell of concrete, usually with no interior columns or exterior buttresses

** Thin-shell structure

Science Biology

* Seashell, a hard ou ...

is large, broadly umbilicated, depressed and subdiscoidal. The shell is opaque and shining. The colour is deep green, usually with some radial streaks of blackish-green.

There is a sculpture

Sculpture is the branch of the visual arts that operates in three dimensions. Sculpture is the three-dimensional art work which is physically presented in the dimensions of height, width and depth. It is one of the plastic arts. Durable sc ...

on the nucleus containing oblique and arcuate radial plaits. The succeeding two whorls are distinctly rugose. On the post-embryonic whorls more or less distinct spiral cords appear, which are first directed upwards, but become spiral on the last whorl. Plaits are distant, low, broadly rounded, varying in number from about 5 to 10 and absent on the base. There are retractive distant growth-plications,

which are prominently and closely plicate at the suture. The whole surface of the shell is microscopically decussated by exceedingly fine and dense radiate and spiral lines, the latter slightly wavy. The periostracum

The periostracum ( ) is a thin, organic coating (or "skin") that is the outermost layer of the shell of many shelled animals, including molluscs and brachiopods. Among molluscs, it is primarily seen in snails and clams, i.e. in gastropods and ...

is thick, glabrous, shining, overhanging the peristome. The spire

A spire is a tall, slender, pointed structure on top of a roof of a building or tower, especially at the summit of church steeples. A spire may have a square, circular, or polygonal plan, with a roughly conical or pyramidal shape. Spires are ...

is flat, very little raised and broadly convex. The protoconch

A protoconch (meaning first or earliest or original shell) is an embryonic or larval shell which occurs in some classes of molluscs, e.g., the initial chamber of an ammonite or the larval shell of a gastropod. In older texts it is also called ...

has 2 whorls, flatly convex, the volutions rather rapidly increasing. The shell has 4½ whorls

A whorl ( or ) is an individual circle, oval, volution or equivalent in a whorled pattern, which consists of a spiral or multiple concentric objects (including circles, ovals and arcs).

Whorls in nature

File:Photograph and axial plane floral ...

, that are rapidly increasing. The last whorl is very large, slightly convex, periphery and base rounded, the body-whorl more or less deflexed anteriorly. Suture well impressed.

The aperture

In optics, an aperture is a hole or an opening through which light travels. More specifically, the aperture and focal length of an optical system determine the cone angle of a bundle of rays that come to a focus in the image plane.

An opt ...

is within shining-blue. Aperture obliquely lunate-oval. Peristome is simple, inflexed throughout. The columella

Lucius Junius Moderatus Columella (; Arabic: , 4 – ) was a prominent writer on agriculture in the Roman Empire.

His ' in twelve volumes has been completely preserved and forms an important source on Roman agriculture, together with the wo ...

is very oblique, slightly arcuate, and shortly reflexed above. Umbilicus broad, perspective and deep.

The width of the shell is 60–79 mm. The height of the shell is 33–44 mm.McGuinness C. A. (2001''The conservation requirements of New Zealand’s nationally threatened invertebrates''

Threatened Species Occasional Publication 20. 658 pp. Page

71-120

The width of the type specimen is 66 × 53 mm, the height of the shell is 29 mm. The

shell

Shell may refer to:

Architecture and design

* Shell (structure), a thin structure

** Concrete shell, a thin shell of concrete, usually with no interior columns or exterior buttresses

** Thin-shell structure

Science Biology

* Seashell, a hard ou ...

of ''Paryphanta busbyi'' has very thick periostracum

The periostracum ( ) is a thin, organic coating (or "skin") that is the outermost layer of the shell of many shelled animals, including molluscs and brachiopods. Among molluscs, it is primarily seen in snails and clams, i.e. in gastropods and ...

and only few micrometre thick calcium

Calcium is a chemical element with the symbol Ca and atomic number 20. As an alkaline earth metal, calcium is a reactive metal that forms a dark oxide-nitride layer when exposed to air. Its physical and chemical properties are most similar to ...

layer. When the shell is kept in dry environment, the shell will explode into pieces, because its periostracum shrinks.

The embryonic shell globose, flat above, of 2 whorls, narrowed toward the base and narrowly umbilicate. The width of the shell is 10 mm. The height of the shell is 9 mm.

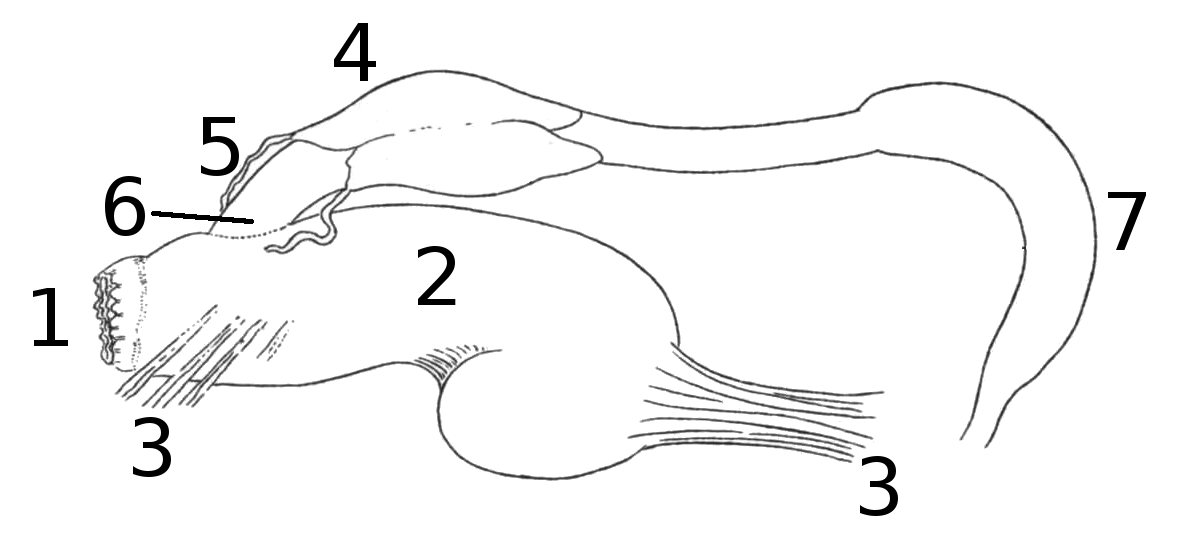

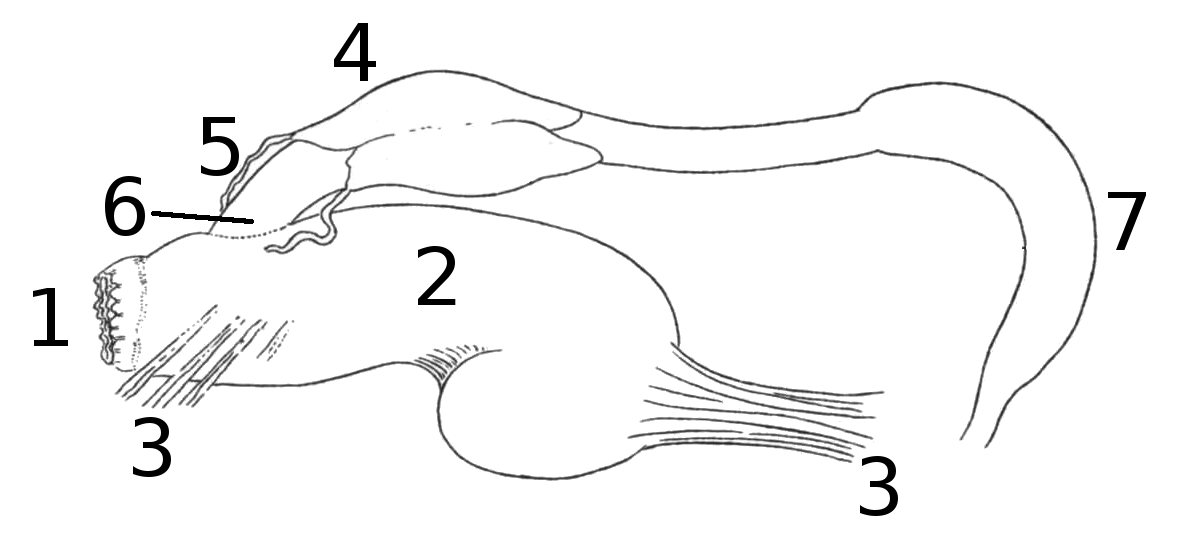

Anatomy

The animal is bluish-black, with the foot-sole perhaps a shade lighter in colour. On the head and neck are a few regular rows of rugae, somewhat quadrate in outline; on other parts of the body the rugae appear to be oval-shaped, irregular in size, and not forming continuous rows. The mantle has a sharp even margin, and a deeply incised line or groove rather less than 2 mm from the edge. On the underside of the mantle is the usual prominent lappet which conceals the respiratory and anal pores, and in addition to this is a long narrow fold on the left side. The retractor muscles: The buccal mass and pedal retractors are fused together posteriorly where they unite with thecolumella

Lucius Junius Moderatus Columella (; Arabic: , 4 – ) was a prominent writer on agriculture in the Roman Empire.

His ' in twelve volumes has been completely preserved and forms an important source on Roman agriculture, together with the wo ...

of the shell. The buccal retractor rests dorsally on the pedal muscles, and forms a broad powerful band. The pedal retractors are continuously attached to the foot, and there are no free progressively attached pedal retractors as in genus ''Helix

A helix () is a shape like a corkscrew or spiral staircase. It is a type of smooth space curve with tangent lines at a constant angle to a fixed axis. Helices are important in biology, as the DNA molecule is formed as two intertwined helices, ...

''. The ocular retractors branch from the pedal muscles; they bifurcate towards their anterior ends, and supply the inferior tentacle retractors.

The length of the radula is about an inch, and 0.4 inch in width at the anterior end, tapering to a point posteriorly, with about 104 transverse rows of denticles (tiny teeth). The rows of denticles are forming an obtuse angle of about 130°, salient posteriorly. There is about 100 small denticles in each row, that described and figured by Captain Frederick Hutton with formula 50-0-50, while Robert C. Murdoch

Robert C. Murdoch (3 February 1861 in Wangaratta, Victoria (Australia), Victoria, Australia – 11 November 1923Tom Iredale, Iredale, T. (1925). "R. Murdoch". ''The Nautilus'' 39(2)6970.) was a malacologist in New Zealand.

Biography

He receive ...

gave the formula 52-0-52. Hutton described them like this: Denticles are all aculeate, and similar, with simple bevelled tips. The first five lateral denticles are small. From the sixth they gradually increase in length to about the thirty-fifth, and then get smaller. Murdoch described them like this: A few of the innermost denticles, usually not more than two on each side, are small and very slender. Occasionally one of these slender spicula-like denticles is somewhat separated from the adjoining denticle, and where this occurs it gives to the row the appearance of a central denticle. There is no jaw.

The

The digestive system

The human digestive system consists of the gastrointestinal tract plus the accessory organs of digestion (the tongue, salivary glands, pancreas, liver, and gallbladder). Digestion involves the breakdown of food into smaller and smaller compone ...

contains enormous buccal mass is and muscular development. Its posterior end is curved down and forward, and a powerful ventral muscle firmly binds it to the more anterior cylindrical portion. The retractor muscle envelopes the posterior end, and from the anterior portion of the mass proceed a number of ventro-lateral muscles, which unite with the immediately adjoining body-walls. The oesophagus enters the buccal cavity dorsally in the anterior fourth. The salivary gland

The salivary glands in mammals are exocrine glands that produce saliva through a system of ducts. Humans have three paired major salivary glands (parotid, submandibular, and sublingual), as well as hundreds of minor salivary glands. Salivary gla ...

s are situate upon the posterior half of the buccal mass; they are fused together in the median line and partly envelope the oesophagus. From the anterior end of each gland proceeds a small salivary duct A salivary duct is a duct (anatomy), duct which brings saliva from a salivary gland to part of the digestive tract. In human anatomy there are:

* Parotid duct

* Submandibular duct

* Major sublingual duct

{{SIA