The Scramble for Africa, also called the Partition of Africa, or Conquest of Africa, was the invasion, annexation, division, and

colonization of most of Africa by seven

Western European

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's countries and territories vary depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the ancient Mediterranean ...

powers during a short period known as

New Imperialism

In historical contexts, New Imperialism characterizes a period of colonial expansion by European powers, the United States, and Japan during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Com

The period featured an unprecedented pursuit of ove ...

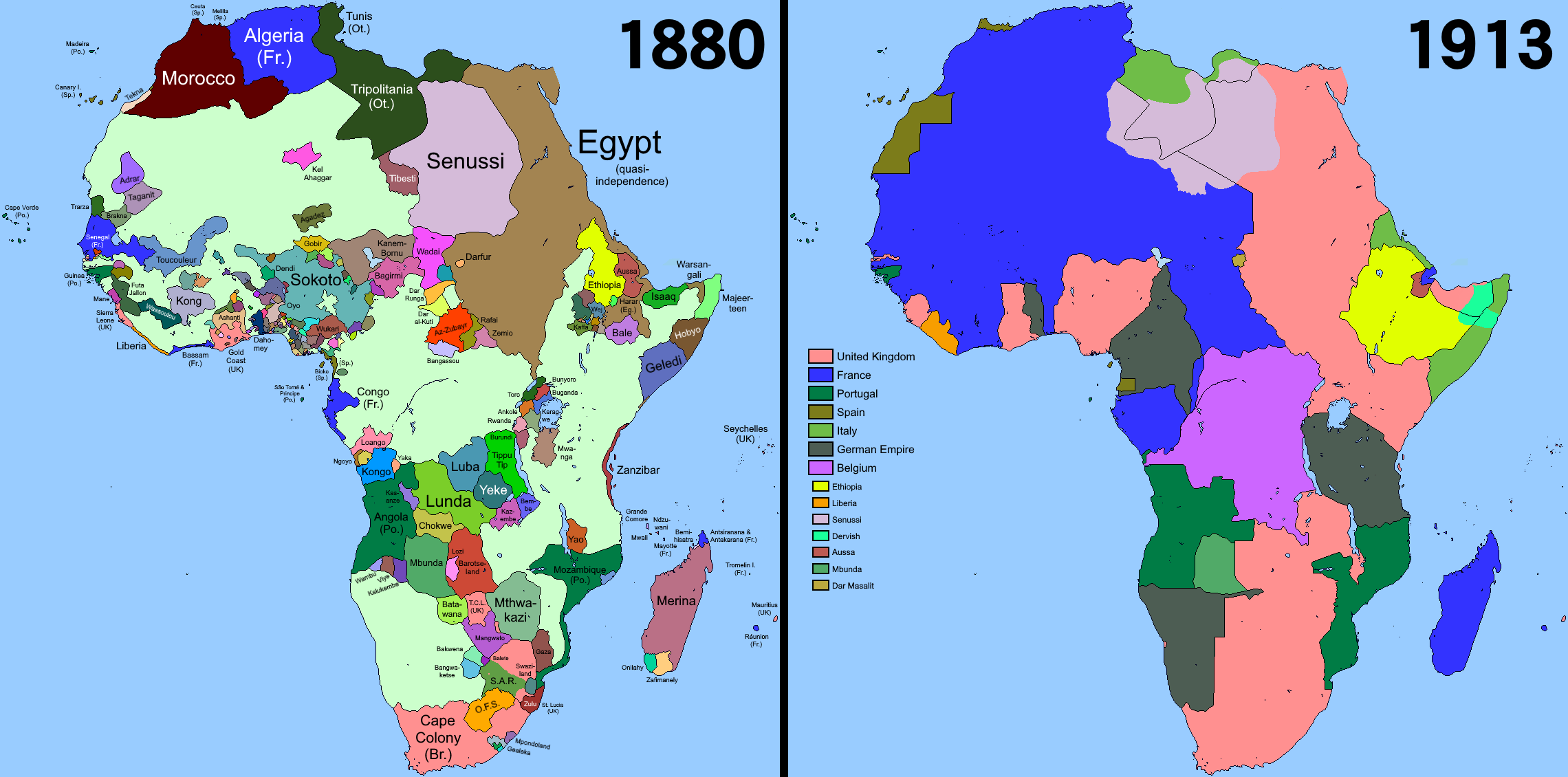

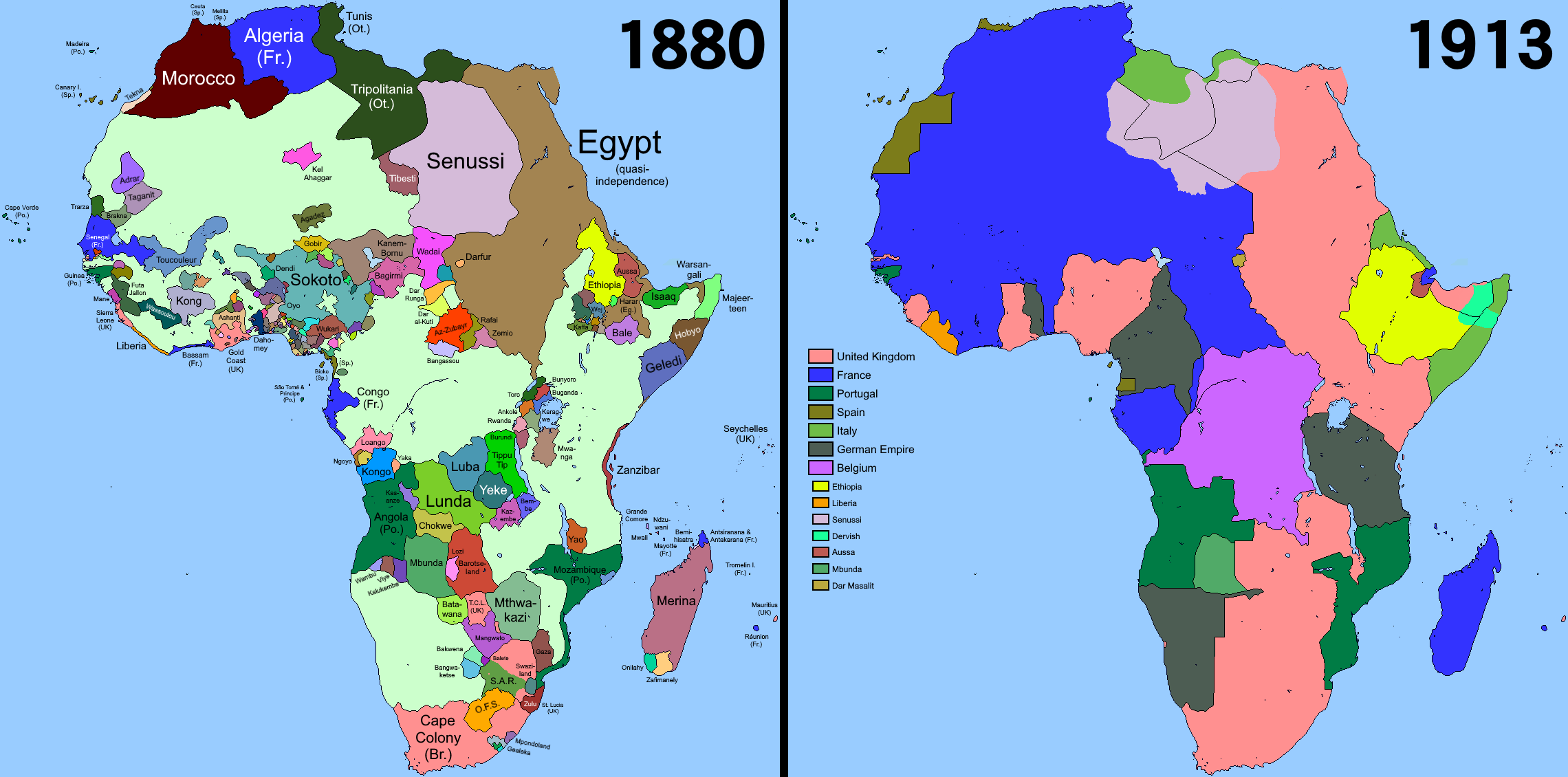

(between 1881 and 1914). The 10 percent of Africa that was under formal European control in 1870 increased to almost 90 percent by 1914, with only

Liberia and

Ethiopia

Ethiopia, , om, Itiyoophiyaa, so, Itoobiya, ti, ኢትዮጵያ, Ítiyop'iya, aa, Itiyoppiya officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country in the Horn of Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the ...

remaining independent.

The

Berlin Conference

The Berlin Conference of 1884–1885, also known as the Congo Conference (, ) or West Africa Conference (, ), regulated European colonisation and trade in Africa during the New Imperialism period and coincided with Germany's sudden emergenc ...

of 1884, which regulated European colonization and trade in Africa, is usually accepted as the beginning. In the last quarter of the 19th century, there were considerable political rivalries within the empires of the

European continent

Continental Europe or mainland Europe is the contiguous continent of Europe, excluding its surrounding islands. It can also be referred to ambiguously as the European continent, – which can conversely mean the whole of Europe – and, by ...

, leading to the

African continent being partitioned without wars between European nations. The later years of the 19th century saw a transition from "

informal imperialism" – military influence and economic dominance – to direct rule.

Background

By 1841, businessmen from Europe had established small trading posts along the coasts of Africa, but they seldom moved inland, preferring to stay near the sea. They primarily traded with locals. Large parts of the continent were essentially uninhabitable for Europeans because of their high mortality rates from

tropical diseases

Tropical diseases are diseases that are prevalent in or unique to tropical and subtropical regions. The diseases are less prevalent in temperate climates, due in part to the occurrence of a cold season, which controls the insect population by forci ...

such as

malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. S ...

. In the middle of the 19th century, European explorers mapped much of

East Africa and

Central Africa

Central Africa is a subregion of the African continent comprising various countries according to different definitions. Angola, Burundi, the Central African Republic, Chad, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Republic of the Congo ...

.

As late as the 1870s, Europeans controlled approximately 10% of the African continent, with all their territories located near the coasts. The most important holdings were

Angola

, national_anthem = " Angola Avante"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capital = Luanda

, religion =

, religion_year = 2020

, religion_ref =

, coordina ...

and

Mozambique

Mozambique (), officially the Republic of Mozambique ( pt, Moçambique or , ; ny, Mozambiki; sw, Msumbiji; ts, Muzambhiki), is a country located in southeastern Africa bordered by the Indian Ocean to the east, Tanzania to the north, Malawi ...

, held by Portugal; the

Cape Colony

The Cape Colony ( nl, Kaapkolonie), also known as the Cape of Good Hope, was a British colony in present-day South Africa named after the Cape of Good Hope, which existed from 1795 to 1802, and again from 1806 to 1910, when it united with t ...

, held by Great Britain; and

Algeria

)

, image_map = Algeria (centered orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Algiers

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, relig ...

, held by France. By 1914, only Ethiopia and Liberia remained independent of European control, with the latter having strong connections to the United States.

Technological advances facilitated European expansion overseas.

Industrialization brought about rapid advancements in transportation and communication, especially in the forms of steamships, railways and telegraphs. Medical advances also played an important role, especially medicines for tropical diseases, which helped control their adverse effects. The development of

quinine

Quinine is a medication used to treat malaria and babesiosis. This includes the treatment of malaria due to '' Plasmodium falciparum'' that is resistant to chloroquine when artesunate is not available. While sometimes used for nocturnal le ...

, an effective treatment for malaria, made vast expanses of the tropics more accessible for Europeans.

Causes

Africa and global markets

Sub-Saharan Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa, one of the last regions of the world largely untouched by "informal imperialism", was attractive to business entrepreneurs. During a time when Britain's

balance of trade

The balance of trade, commercial balance, or net exports (sometimes symbolized as NX), is the difference between the monetary value of a nation's exports and imports over a certain time period. Sometimes a distinction is made between a balance ...

showed a growing deficit, with shrinking and increasingly

protectionist

Protectionism, sometimes referred to as trade protectionism, is the economic policy of restricting imports from other countries through methods such as tariffs on imported goods, import quotas, and a variety of other government regulations. ...

continental markets during the

Long Depression

The Long Depression was a worldwide price and economic recession, beginning in 1873 and running either through March 1879, or 1896, depending on the metrics used. It was most severe in Europe and the United States, which had been experiencing st ...

(1873–96), Africa offered Britain, Germany, France, and other countries an open market that would garner them a trade surplus: a market that bought more from the colonial power than it sold overall.

Surplus capital was often more profitably invested overseas, where cheap materials, limited competition, and abundant raw materials made a greater premium possible. Another inducement for imperialism arose from the demand for raw materials, especially

ivory

Ivory is a hard, white material from the tusks (traditionally from elephants) and teeth of animals, that consists mainly of dentine, one of the physical structures of teeth and tusks. The chemical structure of the teeth and tusks of mammals i ...

,

rubber

Rubber, also called India rubber, latex, Amazonian rubber, ''caucho'', or ''caoutchouc'', as initially produced, consists of polymers of the organic compound isoprene, with minor impurities of other organic compounds. Thailand, Malaysia, an ...

,

palm oil,

cocoa,

diamonds

Diamond is a solid form of the element carbon with its atoms arranged in a crystal structure called diamond cubic. Another solid form of carbon known as graphite is the chemically stable form of carbon at room temperature and pressure, bu ...

,

tea

Tea is an aromatic beverage prepared by pouring hot or boiling water over cured or fresh leaves of ''Camellia sinensis'', an evergreen shrub native to East Asia which probably originated in the borderlands of southwestern China and north ...

, and

tin

Tin is a chemical element with the symbol Sn (from la, stannum) and atomic number 50. Tin is a silvery-coloured metal.

Tin is soft enough to be cut with little force and a bar of tin can be bent by hand with little effort. When bent, t ...

. Additionally, Britain wanted control of areas of southern and eastern coasts of Africa for stopover ports on the route to Asia and its

empire in India. But, excluding the area which became the

Union of South Africa

The Union of South Africa ( nl, Unie van Zuid-Afrika; af, Unie van Suid-Afrika; ) was the historical predecessor to the present-day Republic of South Africa. It came into existence on 31 May 1910 with the unification of the Cape, Natal, Tran ...

in 1910, European nations invested relatively limited amounts of capital in Africa compared to that in other continents. Consequently, the companies involved in tropical African commerce were relatively small, apart from

Cecil Rhodes's

De Beers Mining Company. Rhodes had carved out

Rhodesia for himself.

Leopold II of Belgium

* german: link=no, Leopold Ludwig Philipp Maria Viktor

, house = Saxe-Coburg and Gotha

, father = Leopold I of Belgium

, mother = Louise of Orléans

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Brussels, Belgium

, death_date = ...

created the

Congo Free State for rubber and other resource production.

Pro-imperialist colonial lobbyists such as the ''

Alldeutscher Verband'',

Francesco Crispi and

Jules Ferry

Jules François Camille Ferry (; 5 April 183217 March 1893) was a French statesman and republican philosopher. He was one of the leaders of the Moderate Republicans and served as Prime Minister of France from 1880 to 1881 and 1883 to 1885. He ...

, argued that sheltered overseas markets in Africa would solve the problems of low prices and

overproduction

In economics, overproduction, oversupply, excess of supply or glut refers to excess of supply over demand of products being offered to the market. This leads to lower prices and/or unsold goods along with the possibility of unemployment.

The d ...

caused by shrinking continental markets.

John A. Hobson argued in ''

Imperialism'' that this shrinking of continental markets was a key factor of the global "New Imperialism" period.

William Easterly

William Russell Easterly (born September 7, 1957) is an American economist, specializing in economic development. He is a professor of economics at New York University, joint with Africa House, and co-director of NYU’s Development Research Inst ...

, however, disagrees with the link made between

capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, price system, priva ...

and

imperialism, arguing that

colonialism

Colonialism is a practice or policy of control by one people or power over other people or areas, often by establishing colony, colonies and generally with the aim of economic dominance. In the process of colonisation, colonisers may impose the ...

is used mostly to promote state-led development rather than corporate development. He has said that "imperialism is not so clearly linked to capitalism and the free markets... historically there has been a closer link between colonialism/imperialism and state-led approaches to development."

Strategic rivalry

While tropical Africa was not a large zone of investment, other overseas regions were. The vast interior between Egypt and the gold and diamond-rich

Southern Africa

Southern Africa is the southernmost subregion of the African continent, south of the Congo and Tanzania. The physical location is the large part of Africa to the south of the extensive Congo River basin. Southern Africa is home to a number o ...

had strategic value in securing the flow of overseas trade. Britain was under political pressure to build up lucrative markets in India,

Malaya, Australia and New Zealand. Thus, it wanted to secure the key waterway between East and West – the

Suez Canal, completed in 1869. However, a theory that Britain sought to annex East Africa during the 1880 onwards, out of geo-strategic concerns connected to Egypt (especially the Suez Canal), has been challenged by historians such as

John Darwin (1997) and Jonas F. Gjersø (2015).

The scramble for African territory also reflected concern for the acquisition of military and naval bases, for strategic purposes and the exercise of power. The growing navies, and new ships driven by steam power, required coaling stations and ports for maintenance. Defence bases were also needed for the protection of sea routes and communication lines, particularly of expensive and vital international waterways such as the Suez Canal.

[H.R. Cowie, ''Imperialism and Race Relations''. Revised edition, Nelson Publishing, Vol. 5, 1982.]

Colonies were seen as assets in

balance of power negotiations, useful as items of exchange at times of international bargaining. Colonies with large native populations were also a source of military power; Britain and France used large numbers of

British Indian and North African soldiers, respectively, in many of their colonial wars (and would do so again in the coming World Wars). In the age of

nationalism

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: The ...

there was pressure for a nation to acquire an empire as a status symbol; the idea of "greatness" became linked with the "

White Man's Burden

"The White Man's Burden" (1899), by Rudyard Kipling, is a poem about the Philippine–American War (1899–1902) that exhorts the United States to assume colonial control of the Filipino people and their country.Hitchens, Christopher. ''Bloo ...

", or sense of duty, underlying many nations' strategies.

In the early 1880s,

Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza

Pietro Paolo Savorgnan di Brazzà, later known as Pierre Paul François Camille Savorgnan de Brazza; 26 January 1852 – 14 September 1905), was an Italian-born, naturalized French explorer. With his family's financial help, he explored the Ogoou ...

was exploring the

Kingdom of Kongo for France, at the same time

Henry Morton Stanley explored it on behalf of

Leopold II of Belgium

* german: link=no, Leopold Ludwig Philipp Maria Viktor

, house = Saxe-Coburg and Gotha

, father = Leopold I of Belgium

, mother = Louise of Orléans

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Brussels, Belgium

, death_date = ...

, who would have it as his personal

Congo Free State.

France occupied Tunisia in May 1881, which may have convinced Italy to join the German-Austrian

Dual Alliance in 1882, thus forming the

Triple Alliance. The same year, Britain occupied Egypt (hitherto an autonomous state owing nominal

fealty to the

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

), which ruled over Sudan and parts of Chad, Eritrea, and Somalia. In 1884, Germany declared

Togoland

Togoland was a German Empire protectorate in West Africa from 1884 to 1914, encompassing what is now the nation of Togo and most of what is now the Volta Region of Ghana, approximately 90,400 km2 (29,867 sq mi) in size. During the period kn ...

, the Cameroons and

South West Africa

South West Africa ( af, Suidwes-Afrika; german: Südwestafrika; nl, Zuidwest-Afrika) was a territory under South African administration from 1915 to 1990, after which it became modern-day Namibia. It bordered Angola (Portuguese colony before 1 ...

to be under its protection; and France occupied Guinea.

French West Africa was founded in 1895 and

French Equatorial Africa

French Equatorial Africa (french: link=no, Afrique-Équatoriale française), or the AEF, was the federation of French colonial possessions in Equatorial Africa, extending northwards from the Congo River into the Sahel, and comprising what are ...

in 1910. In

French Somaliland, a short-lived

Russian

Russian(s) refers to anything related to Russia, including:

*Russians (, ''russkiye''), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

*Rossiyane (), Russian language term for all citizens and peo ...

colony in the

Egyptian

Egyptian describes something of, from, or related to Egypt.

Egyptian or Egyptians may refer to:

Nations and ethnic groups

* Egyptians, a national group in North Africa

** Egyptian culture, a complex and stable culture with thousands of years of ...

fort of

Sagallo

Sagallo (russian: Сагалло; ar, ساغلو; french: Sagallou) was a short-lived settlement established in 1889 by a Russian monk and adventurer on the Gulf of Tadjoura in French Somaliland (modern-day Djibouti). It was located some west ...

was briefly proclaimed by

Terek Cossacks

The Terek Cossack Host (russian: Терское казачье войско, ''Terskoye kazach'ye voysko'') was a Cossack host created in 1577 from free Cossacks who resettled from the Volga to the Terek River. The local aboriginal Terek Cossack ...

in 1889.

Germany's Weltpolitik

Germany, divided into small states, was not a colonial power before it unified in 1871. Chancellor

Otto von Bismarck disliked colonies but gave in to popular and elite pressure in the 1880s. He sponsored the 1884–85

Berlin Conference

The Berlin Conference of 1884–1885, also known as the Congo Conference (, ) or West Africa Conference (, ), regulated European colonisation and trade in Africa during the New Imperialism period and coincided with Germany's sudden emergenc ...

, which set the rules of effective control of African territories, and reduced the risk of conflict between colonial powers. Bismarck used private companies to set up small colonial operations in Africa and the Pacific.

Pan-Germanism became linked to the young nation's new imperialist drives. In the beginning of the 1880s, the ''Deutscher Kolonialverein'' was created, and published the ''Kolonialzeitung''. This colonial lobby was also relayed by the nationalist ''

Alldeutscher Verband''. ''

Weltpolitik

''Weltpolitik'' (, "world politics") was the imperialist foreign policy adopted by the German Empire during the reign of Emperor Wilhelm II. The aim of the policy was to transform Germany into a global power. Though considered a logical conseq ...

'' (world policy) was the foreign policy adopted by Kaiser

Wilhelm II

, house = Hohenzollern

, father = Frederick III, German Emperor

, mother = Victoria, Princess Royal

, religion = Lutheranism (Prussian United)

, signature = Wilhelm II, German Emperor Signature-.svg

Wilhelm II (Friedrich Wilhelm Viktor ...

in 1890, with the aim of transforming Germany into a global power through aggressive diplomacy, and the development of a large navy. Germany became the third-largest colonial power in Africa, the location of most of its 2.6 million square kilometres of colonial territory and 14 million colonial subjects in 1914. The African possessions were Southwest Africa, Togoland, the Cameroons, and Tanganyika. Germany tried to isolate France in 1905 with the

First Moroccan Crisis

The First Moroccan Crisis or the Tangier Crisis was an international crisis between March 1905 and May 1906 over the status of Morocco. Germany wanted to challenge France's growing control over Morocco, aggravating France and Great Britain. The ...

. This led to the 1905

Algeciras Conference, in which France's influence on Morocco was compensated by the exchange of other territories, and then to the

Agadir Crisis

The Agadir Crisis, Agadir Incident, or Second Moroccan Crisis was a brief crisis sparked by the deployment of a substantial force of French troops in the interior of Morocco in April 1911 and the deployment of the German gunboat to Agadir, a ...

in 1911.

Italy's expansion

After a

war with Austria in 1859, Italy was largely unified into the Kingdom of Italy in 1861. Italy sought to expand its territory and become a great power,

taking possession of parts of

Eritrea in 1870 and 1882. In 1889–90, it occupied territory on the south side of the horn of Africa, forming what would become

Italian Somaliland

Italian Somalia ( it, Somalia Italiana; ar, الصومال الإيطالي, Al-Sumal Al-Italiy; so, Dhulka Talyaaniga ee Soomaalida), was a protectorate and later colony of the Kingdom of Italy in present-day Somalia. Ruled in the 19th centu ...

. In the disorder that followed the 1889 death of Emperor

Yohannes IV

''girmāwī''His Imperial Majesty, spoken= am , ጃንሆይ ''djānhoi''Your Imperial Majesty(lit. "O steemedroyal"), alternative= am , ጌቶቹ ''getochu''Our Lord (familiar)(lit. "Our master" (pl.)) yohanes

Yohannes IV (Tigrinya: ዮሓ� ...

, General

Oreste Baratieri

Oreste Baratieri (né Oreste Baratter, 13 November 1841 – 7 August 1901) was an Italian general and governor of Italian Eritrea.

Early career

Born in Condino (County of Tyrol, now Trentino), Baratieri began his career as a volunteer for Giusepp ...

occupied the

Ethiopian Highlands

The Ethiopian Highlands is a rugged mass of mountains in Ethiopia in Northeast Africa. It forms the largest continuous area of its elevation in the continent, with little of its surface falling below , while the summits reach heights of up to . ...

along the Eritrean coast, and Italy proclaimed the establishment of a new colony of Eritrea, with its capital moved from

Massawa to

Asmara. When relations between Italy and Ethiopia deteriorated, the

First Italo-Ethiopian War

The First Italo-Ethiopian War, lit. ''Abyssinian War'' was fought between Italy and Ethiopia from 1895 to 1896. It originated from the disputed Treaty of Wuchale, which the Italians claimed turned Ethiopia into an Italian protectorate. Full-sc ...

broke out in 1895; Italian troops were defeated as the Ethiopians had numerical superiority, better organization, and support from Russia and France. In 1911, Italy engaged in a

war with the Ottoman Empire, in which it acquired

Tripolitania

Tripolitania ( ar, طرابلس '; ber, Ṭrables, script=Latn; from Vulgar Latin: , from la, Regio Tripolitana, from grc-gre, Τριπολιτάνια), historically known as the Tripoli region, is a historic region and former province o ...

and

Cyrenaica

Cyrenaica ( ) or Kyrenaika ( ar, برقة, Barqah, grc-koi, Κυρηναϊκή ��παρχίαKurēnaïkḗ parkhíā}, after the city of Cyrene), is the eastern region of Libya. Cyrenaica includes all of the eastern part of Libya between ...

, that together formed what became known as

Italian Libya

Libya ( it, Libia; ar, ليبيا, Lībyā al-Īṭālīya) was a colony of the Fascist Italy located in North Africa, in what is now modern Libya, between 1934 and 1943. It was formed from the unification of the colonies of Italian Cyrenaica ...

. In 1919

Enrico Corradini developed the concept of ''Proletarian Nationalism'', which was supposed to legitimise Italy's imperialism by a mixture of socialism with nationalism:

The

Second Italo-Abyssinian War (1935–36), ordered by the

fascist dictator

Benito Mussolini, was the last colonial war (that is, intended to colonise a country, as opposed to

wars of national liberation

Wars of national liberation or national liberation revolutions are conflicts fought by nations to gain independence. The term is used in conjunction with wars against foreign powers (or at least those perceived as foreign) to establish separa ...

), occupying

Ethiopia

Ethiopia, , om, Itiyoophiyaa, so, Itoobiya, ti, ኢትዮጵያ, Ítiyop'iya, aa, Itiyoppiya officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country in the Horn of Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the ...

—which had remained the last independent African territory, apart from Liberia.

Italian Ethiopia

Italian Ethiopia ( it, Etiopia italiana), also known as the Italian Empire of Ethiopia, was the territory of the Ethiopian Empire which was occupied by Italy for approximately five years. Italian Ethiopia was not an administrative entity, but the ...

was occupied by fascist Italian forces in World War II as part of

Italian East Africa

Italian East Africa ( it, Africa Orientale Italiana, AOI) was an Italian colony in the Horn of Africa. It was formed in 1936 through the merger of Italian Somalia, Italian Eritrea, and the newly occupied Ethiopian Empire, conquered in the S ...

though much of the mountainous countryside had remained out Italian control due to resistance from the

Arbegnoch

The Arbegnoch () were Ethiopian resistance fighters in Italian East Africa from 1936 until 1941. They were known to the Italians as shifta.

Organisation

The Patriot movement was mostly based in the rural Shewa, Gondar and Gojjam provinces, ...

. The occupation is an example of the expansionist policy that characterized the

Axis powers

The Axis powers, ; it, Potenze dell'Asse ; ja, 枢軸国 ''Sūjikukoku'', group=nb originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis, was a military coalition that initiated World War II and fought against the Allies. Its principal members were ...

as opposed to the Scramble for Africa.

History and characteristics

Colonization prior to World War I

Congo

David Livingstone

David Livingstone (; 19 March 1813 – 1 May 1873) was a Scottish physician, Congregationalist, and pioneer Christian missionary with the London Missionary Society, an explorer in Africa, and one of the most popular British heroes of t ...

's explorations, carried on by

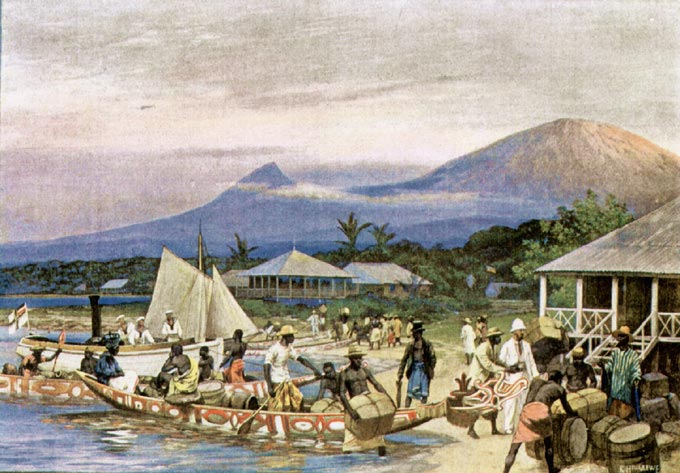

Henry Morton Stanley, excited imaginations with Stanley's grandiose ideas for colonisation; but these found little support owing to the problems and scale of action required, except from Leopold II of Belgium, who in 1876 had organised the

International African Association

The International African Association (in full, "International Association for the Exploration and Civilization of Central Africa"; in French ''Association Internationale Africaine,'' and in full ''Association Internationale pour l'Exploration et ...

. From 1869 to 1874, Stanley was secretly sent by Leopold II to the

Congo region, where he made treaties with several African chiefs along the

Congo River

The Congo River ( kg, Nzâdi Kôngo, french: Fleuve Congo, pt, Rio Congo), formerly also known as the Zaire River, is the second longest river in Africa, shorter only than the Nile, as well as the second largest river in the world by discharge ...

and by 1882 had sufficient territory to form the basis of the

Congo Free State.

While

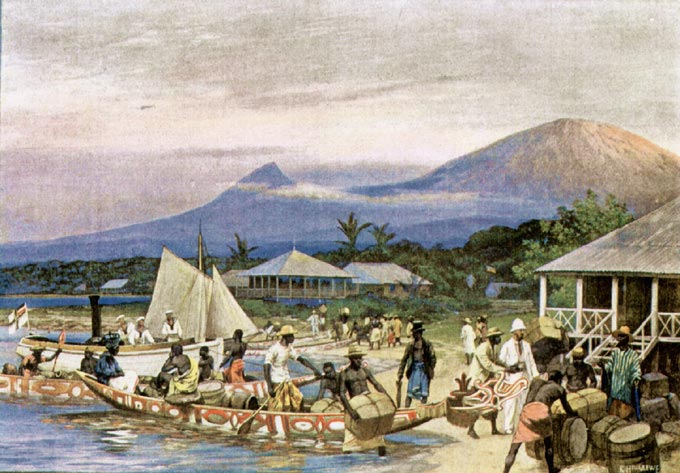

Stanley was exploring the Congo on behalf of Leopold II of Belgium, the Franco-Italian marine officer Pierre de Brazza travelled into the western Congo Basin and raised the French flag over the newly founded

Brazzaville in 1881, thus occupying today's

Republic of the Congo.

Portugal, which also claimed the area because of old treaties with the Kingdom of Kongo, made a treaty with Britain on 26 February 1884 to block off Leopold's access to the Atlantic.

By 1890 the

Congo Free State had consolidated control of its territory between

Leopoldville and

Stanleyville and was looking to push south down the

Lualaba River

The Lualaba River flows entirely within the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo. It provides the greatest streamflow to the Congo River, while the source of the Congo is recognized as the Chambeshi. The Lualaba is long. Its headwaters are i ...

from Stanleyville. At the same time, the

British South Africa Company of

Cecil Rhodes was expanding north from the

Limpopo River

The Limpopo River rises in South Africa and flows generally eastward through Mozambique to the Indian Ocean. The term Limpopo is derived from Rivombo (Livombo/Lebombo), a group of Tsonga settlers led by Hosi Rivombo who settled in the mountain ...

, sending the

Pioneer Column

The Pioneer Column was a force raised by Cecil Rhodes and his British South Africa Company in 1890 and used in his efforts to annex the territory of Mashonaland, later part of Zimbabwe (once Southern Rhodesia).

Background

Rhodes was anxiou ...

(guided by

Frederick Selous

Frederick Courteney Selous, DSO (; 31 December 1851 – 4 January 1917) was a British explorer, officer, professional hunter, and conservationist, famous for his exploits in Southeast Africa. His real-life adventures inspired Sir Henry R ...

) through

Matabeleland

Matabeleland is a region located in southwestern Zimbabwe that is divided into three provinces: Matabeleland North, Bulawayo, and Matabeleland South. These provinces are in the west and south-west of Zimbabwe, between the Limpopo and Zambezi ...

, and starting a colony in

Mashonaland.

Tippu Tip

Tippu Tip, or Tippu Tib (1832 – June 14, 1905), real name Ḥamad ibn Muḥammad ibn Jumʿah ibn Rajab ibn Muḥammad ibn Saʿīd al Murjabī ( ar, حمد بن محمد بن جمعة بن رجب بن محمد بن سعيد المرجبي), ...

, a Zanzibari Arab based in the

Sultanate of Zanzibar

The Sultanate of Zanzibar ( sw, Usultani wa Zanzibar, ar, سلطنة زنجبار , translit=Sulṭanat Zanjībār), also known as the Zanzibar Sultanate, was a state controlled by the Sultan of Zanzibar, in place between 1856 and 1964. The Su ...

, also played a major role as a "protector of European explorers", ivory trader and slave trader. Having established a trading empire within Zanzibar and neighboring areas in East Africa, Tippu Tip would shift his alignment towards the rising colonial powers in the region and at the proposal of Henry Morton Stanley, Tippu Tip became a governor of the "

Stanley Falls District" (

Boyoma Falls

Boyoma Falls, formerly known as Stanley Falls, is a series of seven cataracts, each no more than high, extending over more than along a curve of the Lualaba River between the river port towns of Ubundu and Kisangani (also known as Boyoma) in t ...

) in Leopold's Congo Free State, before being involved in the

Congo–Arab War

The Congo–Arab War (also known as the Congolese–Arab War, Belgo–Arab War or Arab Wars) was fought in Central Africa between the forces of Belgian King Leopold II's Congo Free State and various Zanzibari Arab slave traders led by Sefu bin H ...

against Leopold II's colonial state.

To the west, in the land where their expansions would meet, was

Katanga, site of the

Yeke Kingdom of

Msiri. Msiri was the most militarily powerful ruler in the area and traded large quantities of copper, ivory and slaves—and rumors of gold reached European ears. The scramble for Katanga was a prime example of the period. Rhodes sent two expeditions to Msiri in 1890 led by

Alfred Sharpe

Sir Alfred Sharpe (19 May 1853 – 10 December 1935) was Commissioner and Consul-General for the British Central Africa Protectorate and first Governor of Nyasaland.

He trained as a solicitor but was in turn a planter and a professional hun ...

, who was rebuffed, and

Joseph Thomson Joseph or Joe Thomson is the name of:

*J. J. Thomson (1856–1940), physicist

* Joseph Thomson (cricketer) (1877-1953), Australian cricketer

*Joseph Thomson (explorer)

Joseph Thomson (14 February 1858 – 2 August 1895) was a British geologist ...

, who failed to reach Katanga. Leopold sent four expeditions. First, the

Le Marinel expedition could only extract a vaguely worded letter. The

Delcommune expedition was rebuffed. The well-armed

Stairs expedition was given orders to take Katanga with or without Msiri's consent. Msiri refused, was shot, and his head was cut off and stuck on a pole as a "barbaric lesson" to the people. The

Bia River

The Bia is a river that is situated primarily in Ghana and flows through Ghana and Ivory Coast, emptying into Aby Lagoon. A hydroelectric dam was built across the Bia at Ayamé

Ayamé is a town in south-eastern Ivory Coast, near the border of Gh ...

expedition finished the job of establishing an administration of sorts and a "police presence" in Katanga. Thus, the half million square kilometres of Katanga came into Leopold's possession and brought his African realm up to , about 75 times larger than Belgium. The Congo Free State imposed such a

terror regime on the colonized people, including mass killings and forced labour, that Belgium, under pressure from the

Congo Reform Association

The Congo Reform Association (CRA) was a political and Humanitarianism, humanitarian Activism, activist group that sought to promote reform of the Congo Free State, a private territory in Central Africa under the Absolute monarchy, absolute sovere ...

, ended Leopold II's rule and annexed it on 20 August 1908 as a colony of Belgium, known as the

Belgian Congo

The Belgian Congo (french: Congo belge, ; nl, Belgisch-Congo) was a Belgian colony in Central Africa from 1908 until independence in 1960. The former colony adopted its present name, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), in 1964.

Colo ...

.

The

brutality of King Leopold II in his former colony of the Congo Free State was well documented; up to 8 million of the estimated 16 million native inhabitants died between 1885 and 1908.

According to

Roger Casement

Roger David Casement ( ga, Ruairí Dáithí Mac Easmainn; 1 September 1864 – 3 August 1916), known as Sir Roger Casement, CMG, between 1911 and 1916, was a diplomat and Irish nationalist executed by the United Kingdom for treason during Worl ...

, an Irish diplomat of the time, this depopulation had four main causes: "indiscriminate war", starvation, reduction of births and diseases.

Sleeping sickness

African trypanosomiasis, also known as African sleeping sickness or simply sleeping sickness, is an insect-borne parasitic infection of humans and other animals. It is caused by the species ''Trypanosoma brucei''. Humans are infected by two typ ...

ravaged the country and must also be taken into account for the dramatic decrease in population; it has been estimated that sleeping sickness and

smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

killed nearly half the population in the areas surrounding the lower Congo River. Estimates of the death toll vary considerably. As the first census did not take place until 1924, it is difficult to quantify the population loss of the period. The

Casement Report

The Casement Report was a 1904 document written by Roger Casement (1864–1916)—a diplomat and Irish independence fighter—detailing abuses in the Congo Free State which was under the private ownership of King Leopold II of Belgium. This repo ...

set it at three million.

William Rubinstein

William D. Rubinstein (born 12 August 1946) is a historian and author. His best-known work, ''Men of Property: The Very Wealthy in Britain Since the Industrial Revolution'', charts the rise of the ' super rich', a class he sees as expanding ex ...

writes: "More basically, it appears almost certain that the population figures given by

Hochschild are inaccurate. There is, of course, no way of ascertaining the population of the Congo before the twentieth century, and estimates like 20 million are purely guesses. Most of the interior of the Congo was literally unexplored if not inaccessible."

A similar situation occurred in the neighbouring

French Congo

The French Congo (french: Congo français) or Middle Congo (french: Moyen-Congo) was a French colony which at one time comprised the present-day area of the Republic of the Congo and parts of Gabon, and the Central African Republic. In 1910, ...

, where most of the resource extraction was run by concession companies, whose brutal methods, along with the introduction of disease, resulted in the loss of up to 50% of the indigenous population according to Hochschild. The French government appointed a commission headed by de Brazza in 1905 to investigate the rumoured abuses in the colony. However, de Brazza died on the return trip, and his "searingly critical" report was neither acted upon nor released to the public. In the 1920s, about 20,000 forced labourers died building a railroad through the French territory.

Egypt, Sudan, and South Sudan

= Suez Canal

=

In order to construct the

Suez Canal, French diplomat

Ferdinand de Lesseps

Ferdinand Marie, Comte de Lesseps (; 19 November 1805 – 7 December 1894) was a French diplomat and later developer of the Suez Canal, which in 1869 joined the Mediterranean and Red Seas, substantially reducing sailing distances and times ...

had obtained many concessions from

Isma'il Pasha

Isma'il Pasha ( ar, إسماعيل باشا ; 12 January 1830 – 2 March 1895), was the Khedive of Egypt and conqueror of Sudan from 1863 to 1879, when he was removed at the behest of Great Britain. Sharing the ambitious outlook of his gran ...

, the

Khedive of Egypt and Sudan in 1854–56. Some sources estimate the workforce at 30,000, but others estimate that 120,000 workers died over the ten years of construction from malnutrition, fatigue, and disease, especially

cholera. Shortly before its completion in 1869, Khedive Isma'il borrowed enormous sums from British and French bankers at high rates of interest. By 1875, he was facing financial difficulties and was forced to sell his block of shares in the Suez Canal. The shares were snapped up by Britain, under Prime Minister

Benjamin Disraeli, who sought to give his country practical control in the management of this strategic waterway. When Isma'il repudiated Egypt's foreign debt in 1879, Britain and France seized joint financial control over the country, forcing the Egyptian ruler to abdicate and installing his eldest son

Tewfik Pasha

Mohamed Tewfik Pasha ( ar, محمد توفيق باشا ''Muḥammad Tawfīq Bāshā''; April 30 or 15 November 1852 – 7 January 1892), also known as Tawfiq of Egypt, was khedive of Egypt and the Sudan between 1879 and 1892 and the sixth rule ...

in his place. The Egyptian and Sudanese ruling classes did not relish foreign intervention.

= Mahdist War

=

During the 1870s, European initiatives against the slave trade caused an economic crisis in northern Sudan, precipitating the rise of

Mahdist forces. In 1881, the

Mahdist revolt

The Mahdist War ( ar, الثورة المهدية, ath-Thawra al-Mahdiyya; 1881–1899) was a war between the Mahdist Sudanese of the religious leader Muhammad Ahmad bin Abd Allah, who had proclaimed himself the "Mahdi" of Islam (the "Guided On ...

erupted in Sudan under

Muhammad Ahmad

Muhammad Ahmad ( ar, محمد أحمد ابن عبد الله; 12 August 1844 – 22 June 1885) was a Nubian Sufi religious leader of the Samaniyya order in Sudan who, as a youth, studied Sunni Islam. In 1881, he claimed to be the Mahdi, ...

, severing Tewfik's authority in Sudan. The same year, Tewfik suffered an even more perilous rebellion by his own Egyptian army in the form of the

Urabi revolt. In 1882, Tewfik appealed for direct British military assistance, commencing Britain's administration of Egypt. A joint British-Egyptian military force entered in the Mahdist War.

Additionally the Egyptian province of

Equatoria (located in South Sudan) led by

Emin Pasha was also subject to an ostensible

relief expedition of Emin Pasha against Mahdist forces. The British-Egyptian force ultimately defeated the Mahdist forces in Sudan in 1898.

Thereafter, Britain seized effective control of Sudan, which was nominally called

Anglo-Egyptian Sudan

Anglo-Egyptian Sudan ( ar, السودان الإنجليزي المصري ') was a condominium of the United Kingdom and Egypt in the Sudans region of northern Africa between 1899 and 1956, corresponding mostly to the territory of present-day ...

.

Berlin Conference (1884–1885)

The occupation of Egypt and the acquisition of the Congo were the first major moves in what came to be a precipitous scramble for African territory. In 1884,

Otto von Bismarck convened the 1884–1885 Berlin Conference to discuss the African problem. While diplomatic discussions were held regarding ending the remaining slave trade as well as the reach of missionary activities, the primary concern of those in attendance was preventing war between the European powers as they divided the continent among themselves. More importantly, the diplomats in

Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and List of cities in Germany by population, largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's List of cities in the European Union by population within ci ...

laid down the rules of competition by which the great powers were to be guided in seeking colonies. They also agreed that the area along the Congo River was to be administered by Leopold II as a neutral area in which trade and navigation were to be free. No nation was to stake claims in Africa without notifying other powers of its intentions. No territory could be formally claimed prior to being effectively occupied. However, the competitors ignored the rules when convenient, and on several occasions war was only narrowly avoided (see

Fashoda Incident

The Fashoda Incident, also known as the Fashoda Crisis (French: ''Crise de Fachoda''), was an international incident and the climax of imperialist territorial disputes between Britain and France in East Africa, occurring in 1898. A French exped ...

. The

Swahili coast territories of the Sultanate of Zanzibar were partitioned between Germany and Britain, initially leaving the archipelago of

Zanzibar

Zanzibar (; ; ) is an insular semi-autonomous province which united with Tanganyika in 1964 to form the United Republic of Tanzania. It is an archipelago in the Indian Ocean, off the coast of the mainland, and consists of many small islan ...

independent until 1890, when that remnant of the Sultanate was made into a British protectorate with the

Heligoland–Zanzibar Treaty

The Heligoland–Zanzibar Treaty (german: Helgoland-Sansibar-Vertrag; also known as the Anglo-German Agreement of 1890) was an agreement signed on 1 July 1890 between the German Empire and the United Kingdom.

The accord gave Germany control of ...

.

Britain's administration of Egypt and South Africa

Britain's administration of Egypt and the

Cape Colony

The Cape Colony ( nl, Kaapkolonie), also known as the Cape of Good Hope, was a British colony in present-day South Africa named after the Cape of Good Hope, which existed from 1795 to 1802, and again from 1806 to 1910, when it united with t ...

contributed to a preoccupation over securing the source of the

Nile

The Nile, , Bohairic , lg, Kiira , Nobiin: Áman Dawū is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa and has historically been considered the longest ...

River. Egypt was taken over by the British in 1882, leaving the Ottoman Empire in a nominal role until 1914, when London made it a protectorate. Egypt was never an actual British colony. Sudan, Nigeria, Kenya, and Uganda were subjugated in the 1890s and early 20th century; and in the south, the Cape Colony (first acquired in 1795) provided a base for the subjugation of neighbouring African states and the Dutch

Afrikaner settlers who had left the Cape to avoid the British and then founded their own republics.

Theophilus Shepstone

Theophilus Shepstone

Sir Theophilus Shepstone (8 January 181723 June 1893) was a British South African statesman who was responsible for the annexation of the Transvaal to Britain in 1877.

Early life

Theophilus Shepstone was born at Westbury ...

annexed the

South African Republic

The South African Republic ( nl, Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek, abbreviated ZAR; af, Suid-Afrikaanse Republiek), also known as the Transvaal Republic, was an independent Boer Republic in Southern Africa which existed from 1852 to 1902, when it ...

in 1877 for the British Empire, after it had been independent for twenty years. In 1879, after the

Anglo-Zulu War

The Anglo-Zulu War was fought in 1879 between the British Empire and the Zulu Kingdom. Following the passing of the British North America Act of 1867 forming a federation in Canada, Lord Carnarvon thought that a similar political effort, cou ...

, Britain consolidated its control of most of the territories of South Africa. The Boers protested, and in December 1880 they revolted, leading to the

First Boer War

The First Boer War ( af, Eerste Vryheidsoorlog, literally "First Freedom War"), 1880–1881, also known as the First Anglo–Boer War, the Transvaal War or the Transvaal Rebellion, was fought from 16 December 1880 until 23 March 1881 betwee ...

. British Prime Minister

William Gladstone signed a peace treaty on 23 March 1881, giving self-government to the

Boers

Boers ( ; af, Boere ()) are the descendants of the Dutch-speaking Free Burghers of the eastern Cape frontier in Southern Africa during the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. From 1652 to 1795, the Dutch East India Company controlled this are ...

in the

Transvaal Transvaal is a historical geographic term associated with land north of (''i.e.'', beyond) the Vaal River in South Africa. A number of states and administrative divisions have carried the name Transvaal.

* South African Republic (1856–1902; af, ...

. The

Jameson Raid

The Jameson Raid (29 December 1895 – 2 January 1896) was a botched raid against the South African Republic (commonly known as the Transvaal) carried out by British colonial administrator Leander Starr Jameson, under the employment of Cecil ...

of 1895 was a failed attempt by the British South Africa Company and the

Johannesburg Reform Committee The Reform Committee was an organisation of prominent Johannesburg citizens which existed late 1895/early 1896.

History

The Transvaal gold rush had brought in a considerable foreign population, chiefly British although there were substantial mi ...

to overthrow the Boer government in the Transvaal. The

Second Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the South ...

, fought between 1899 and 1902, was about control of the gold and diamond industries; the independent Boer republics of the

Orange Free State

The Orange Free State ( nl, Oranje Vrijstaat; af, Oranje-Vrystaat;) was an independent Boer sovereign republic under British suzerainty in Southern Africa during the second half of the 19th century, which ceased to exist after it was defeat ...

and the South African Republic were this time defeated and absorbed into the British Empire.

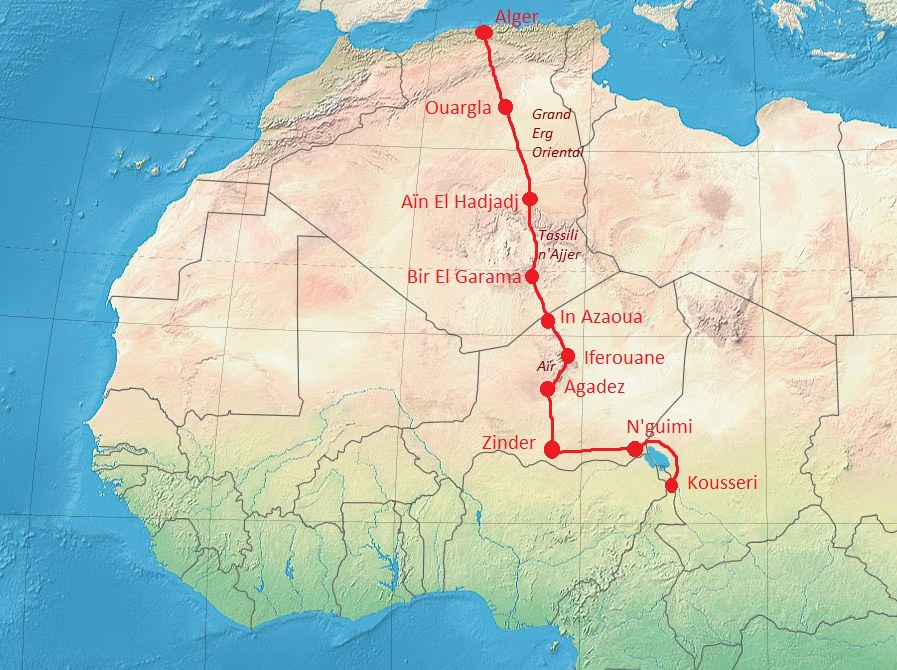

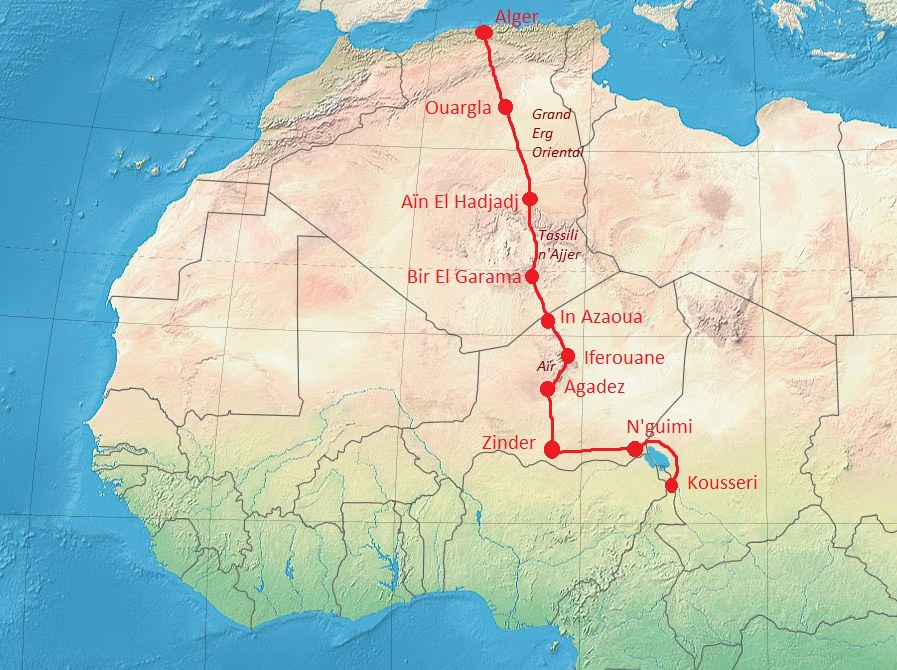

The French thrust into the African interior was mainly from the coasts of

West Africa

West Africa or Western Africa is the westernmost region of Africa. The United Nations defines Western Africa as the 16 countries of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Mali, M ...

(present-day Senegal) eastward, through the

Sahel along the southern border of the

Sahara. Their ultimate aim was to have an uninterrupted colonial empire from the

Niger River

The Niger River ( ; ) is the main river of West Africa, extending about . Its drainage basin is in area. Its source is in the Guinea Highlands in south-eastern Guinea near the Sierra Leone border. It runs in a crescent shape through ...

to the Nile, thus controlling all trade to and from the Sahel region by virtue of their existing control over the caravan routes through the Sahara. The British, on the other hand, wanted to link their possessions in

Southern Africa

Southern Africa is the southernmost subregion of the African continent, south of the Congo and Tanzania. The physical location is the large part of Africa to the south of the extensive Congo River basin. Southern Africa is home to a number o ...

with their territories in

East Africa and these two areas with the Nile basin.

The Sudan (which included most of present-day Uganda) was the key to the fulfillment of these ambitions, especially since Egypt was already under British control. This "red line" through Africa is made most famous by Cecil Rhodes. Along with

Lord Milner

Alfred Milner, 1st Viscount Milner, (23 March 1854 – 13 May 1925) was a British statesman and colonial administrator who played a role in the formulation of British foreign and domestic policy between the mid-1890s and early 1920s. From ...

, the British colonial minister in South Africa, Rhodes advocated such a "Cape to Cairo" empire, linking the Suez Canal to the mineral-rich South Africa by rail. Though hampered by German occupation of

Tanganyika

Tanganyika may refer to:

Places

* Tanganyika Territory (1916–1961), a former British territory which preceded the sovereign state

* Tanganyika (1961–1964), a sovereign state, comprising the mainland part of present-day Tanzania

* Tanzania Main ...

until the end of World War I, Rhodes successfully lobbied on behalf of such a sprawling African empire.

If one draws a line from

Cape Town

Cape Town ( af, Kaapstad; , xh, iKapa) is one of South Africa's three capital cities, serving as the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. It is the legislative capital of the country, the oldest city in the country, and the second largest ...

to

Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the Capital city, capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the List of urban agglomerations in Africa, largest urban agglomeration in Africa, List of ...

(Rhodes's dream), and one from

Dakar

Dakar ( ; ; wo, Ndakaaru) (from :wo:daqaar, daqaar ''tamarind''), is the capital city, capital and List of cities in Senegal, largest city of Senegal. The city of Dakar proper has a population of 1,030,594, whereas the population of the Dakar ...

to the

Horn of Africa (the French ambition), these two lines intersect somewhere in eastern Sudan near

Fashoda

Kodok or Kothok ( ar, كودوك), formerly known as Fashoda, is a town in the north-eastern South Sudanese state of Upper Nile State. Kodok is the capital of Shilluk country, formally known as the Shilluk Kingdom. Shilluk had been an independ ...

, explaining its strategic importance. In short, Britain had sought to extend its East African empire contiguously from Cairo to the

Cape of Good Hope, while France had sought to extend its own holdings from Dakar to the Sudan, which would enable its empire to span the entire continent from the

Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe ...

to the

Red Sea

The Red Sea ( ar, البحر الأحمر - بحر القلزم, translit=Modern: al-Baḥr al-ʾAḥmar, Medieval: Baḥr al-Qulzum; or ; Coptic: ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϩⲁϩ ''Phiom Enhah'' or ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϣⲁⲣⲓ ''Phiom ǹšari''; ...

.

A French force under

Jean-Baptiste Marchand

:''for others with similar names, see Jean Marchand

General Jean-Baptiste Marchand (22 November 1863 – 14 January 1934) was a French military officer and explorer in Africa. Marchand is best known for commanding the French expeditionary ...

arrived first at the strategically located fort at Fashoda, soon followed by a British force under

Lord Kitchener, commander in chief of the British Army since 1892. The French withdrew after a standoff and continued to press claims to other posts in the region. The

Fashoda Incident

The Fashoda Incident, also known as the Fashoda Crisis (French: ''Crise de Fachoda''), was an international incident and the climax of imperialist territorial disputes between Britain and France in East Africa, occurring in 1898. A French exped ...

ultimately led to the signature of the ''

Entente Cordiale

The Entente Cordiale (; ) comprised a series of agreements signed on 8 April 1904 between the United Kingdom and the French Republic which saw a significant improvement in Anglo-French relations. Beyond the immediate concerns of colonial de ...

'' of 1904, which guaranteed peace between the two.

Moroccan Crisis

Although the Berlin Conference had set the rules for the Scramble for Africa, it had not weakened the rival imperialists. As a result of the ''Entente Cordiale'', the German Kaiser decided to test the solidity of such influence, using the contested territory of

Morocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria t ...

as a battlefield. Kaiser Wilhelm II visited

Tangier

Tangier ( ; ; ar, طنجة, Ṭanja) is a city in northwestern Morocco. It is on the Moroccan coast at the western entrance to the Strait of Gibraltar, where the Mediterranean Sea meets the Atlantic Ocean off Cape Spartel. The town is the capi ...

on 31 March 1905 and made a speech in favour of Moroccan independence, challenging French influence in Morocco. France's presence had been reaffirmed by Britain and Spain in 1904. The Kaiser's speech bolstered French nationalism, and with British support the French foreign minister,

Théophile Delcassé

Théophile Delcassé (1 March 185222 February 1923) was a French politician who served as foreign minister from 1898 to 1905. He is best known for his hatred of Germany and efforts to secure alliances with Russia and Great Britain that became t ...

, took a defiant line. The crisis peaked in mid-June 1905, when Delcassé was forced out of the ministry by the more conciliation-minded premier

Maurice Rouvier

Maurice Rouvier (; 17 April 1842 – 7 June 1911) was a French statesman of the "Opportunist" faction, who served as the Prime Minister of France. He is best known for his financial policies and his unpopular policies designed to avoid a ruptur ...

. But by July 1905 Germany was becoming isolated, and the French agreed to a conference to solve the crisis.

The 1906

Algeciras Conference was called to settle the dispute. Of the thirteen nations present, the German representatives found their only supporter was

Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

, which had no interest in Africa. France had firm support from Britain, the U.S., Russia, Italy and Spain. The Germans eventually accepted an agreement, signed on 31 May 1906, whereby France yielded certain domestic changes in Morocco but retained control of key areas.

However, five years later the Second Moroccan Crisis (or

Agadir Crisis

The Agadir Crisis, Agadir Incident, or Second Moroccan Crisis was a brief crisis sparked by the deployment of a substantial force of French troops in the interior of Morocco in April 1911 and the deployment of the German gunboat to Agadir, a ...

) was sparked by the deployment of the German gunboat ''

Panther

Panther may refer to:

Large cats

*Pantherinae, the cat subfamily that contains the genera ''Panthera'' and ''Neofelis''

**'' Panthera'', the cat genus that contains tigers, lions, jaguars and leopards.

*** Jaguar (''Panthera onca''), found in So ...

'' to the port of

Agadir

Agadir ( ar, أݣادير, ʾagādīr; shi, ⴰⴳⴰⴷⵉⵔ) is a major city in Morocco, on the shore of the Atlantic Ocean near the foot of the Atlas Mountains, just north of the point where the Souss River flows into the ocean, and south ...

in July 1911. Germany had started to attempt to match Britain's

naval supremacy

Command of the sea (also called control of the sea or sea control) is a naval military concept regarding the strength of a particular navy to a specific naval area it controls. A navy has command of the sea when it is so strong that its rivals ...

—the British navy had a policy of remaining larger than the next two rival fleets in the world combined. When the British heard of the ''Panther''s arrival in Morocco, they wrongly believed that the Germans meant to turn Agadir into a naval base on the Atlantic. The German move was aimed at reinforcing claims for compensation for acceptance of effective French control of the

North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

n kingdom, where France's pre-eminence had been upheld by the 1906 Algeciras Conference. In November 1911 a compromise was reached under which Germany accepted France's position in Morocco in return for a slice of territory in the

French Equatorial Africa

French Equatorial Africa (french: link=no, Afrique-Équatoriale française), or the AEF, was the federation of French colonial possessions in Equatorial Africa, extending northwards from the Congo River into the Sahel, and comprising what are ...

n colony of

Middle Congo

Middle or The Middle may refer to:

* Centre (geometry), the point equally distant from the outer limits.

Places

* Middle (sheading), a subdivision of the Isle of Man

* Middle Bay (disambiguation)

* Middle Brook (disambiguation)

* Middle Creek ...

.

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

and

Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

subsequently established a full

protectorate

A protectorate, in the context of international relations, is a state that is under protection by another state for defence against aggression and other violations of law. It is a dependent territory that enjoys autonomy over most of its int ...

over Morocco on 30 March 1912, ending what remained of the country's formal independence. Furthermore, British backing for France during the two Moroccan crises reinforced the ''Entente'' between the two countries and added to Anglo-German estrangement, deepening the divisions that would culminate in the First World War.

Dervish resistance

Following the Berlin Conference, the British, Italians, and Ethiopians sought to claim lands inhabited by the Somalis. The

Dervish movement, led by

Sayid Muhammed Abdullah Hassan, existed for 21 years, from 1899 until 1920. The Dervish movement successfully repulsed the British Empire four times and forced it to retreat to the coastal region. Because of these successful expeditions, the Dervish movement was recognized as an ally by the

Ottoman and

German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

** Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

empires. The

Turks

Turk or Turks may refer to:

Communities and ethnic groups

* Turkic peoples, a collection of ethnic groups who speak Turkic languages

* Turkish people, or the Turks, a Turkic ethnic group and nation

* Turkish citizen, a citizen of the Republic ...

named Hassan

Emir

Emir (; ar, أمير ' ), sometimes transliterated amir, amier, or ameer, is a word of Arabic origin that can refer to a male monarch, aristocrat, holder of high-ranking military or political office, or other person possessing actual or cer ...

of the Somali nation, and the Germans promised to officially recognise any territories the Dervishes were to acquire. After a quarter of a century of holding the British at bay, the

Dervishes were finally defeated in 1920 as a direct consequence of Britain's use of aircraft.

Herero Wars and the Maji Maji Rebellion

Between 1904 and 1908, Germany's colonies in

German South West Africa

German South West Africa (german: Deutsch-Südwestafrika) was a colony of the German Empire from 1884 until 1915, though Germany did not officially recognise its loss of this territory until the 1919 Treaty of Versailles. With a total area of ...

and

German East Africa were rocked by separate, contemporaneous native revolts against their rule. In both territories the threat to German rule was quickly defeated once large-scale reinforcements from Germany arrived, with the

Herero rebels in German South West Africa being defeated at the

Battle of Waterberg

The Battle of Waterberg (Battle of Ohamakari) took place on August 11, 1904 at the Waterberg, German South West Africa (modern day Namibia), and was the decisive battle in the German campaign against the Herero.

Armies

The German Imperial For ...

and the Maji-Maji rebels in German East Africa being steadily crushed by German forces slowly advancing through the countryside, with the natives resorting to

guerrilla warfare.

German efforts to clear the bush of civilians in German South West Africa resulted in a genocide of the population. In total, as many as 65,000 Herero (80% of the total Herero population), and 10,000 Namaqua (50% of the total Namaqua population) either starved, died of thirst, or were worked to death in camps such as

Shark Island concentration camp

Shark Island or "Death Island" was one of five concentration camps in German South West Africa. It was located on Shark Island off Lüderitz, in the far south-west of the territory which today is Namibia. It was used by the German Empire during ...

between 1904 and 1908. Between 24,000 and 100,000 Hereros, 10,000

Nama, and an unknown number of

San died in the genocide.

[Jeremy Sarkin-Hughes (2008) ''Colonial Genocide and Reparations Claims in the 21st Century: The Socio-Legal Context of Claims under International Law by the Herero against Germany for Genocide in Namibia, 1904-1908'', p. 142, Praeger Security International, Westport, Conn. ] Characteristic of this genocide was death from starvation, thirst, and possibly the poisoning of the population's wells, whilst they were trapped in the

Namib Desert

The Namib ( ; pt, Namibe) is a coastal desert in Southern Africa. The name is of Khoekhoegowab origin and means "vast place". According to the broadest definition, the Namib stretches for more than along the Atlantic coasts of Angola, Nami ...

.

[Samuel Totten, William S. Parsons, Israel W. Charny (2004)]

''Century of Genocide: Critical Essays and Eyewitness Accounts''

Routledge, NY p. 22[Dan Kroll (2006) ''Securing Our Water Supply: Protecting a Vulnerable Resource'', p. 22, PennWell Corp/University of Michigan Press ]

Philosophy

Colonial consciousness and exhibitions

Colonial lobby

In its earlier stages, imperialism was generally the act of individual explorers as well as some adventurous merchantmen. The colonial powers were a long way from approving without any dissent the expensive adventures carried out abroad. Various important political leaders, such as

William Gladstone, opposed colonization in its first years. However, during his second premiership between 1880 and 1885 he could not resist the colonial lobby in his cabinet, and thus did not execute his electoral promise to disengage from Egypt. Although Gladstone was personally opposed to imperialism, the

social tensions caused by the Long Depression pushed him to favour

jingoism: the imperialists had become the "parasites of patriotism." In

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

,

Radical politician

Georges Clemenceau

Georges Benjamin Clemenceau (, also , ; 28 September 1841 – 24 November 1929) was a French statesman who served as Prime Minister of France from 1906 to 1909 and again from 1917 until 1920. A key figure of the Independent Radicals, he was a ...

was adamantly opposed to it: he thought colonization was a diversion from the "blue line of the

Vosges

The Vosges ( , ; german: Vogesen ; Franconian and gsw, Vogese) are a range of low mountains in Eastern France, near its border with Germany. Together with the Palatine Forest to the north on the German side of the border, they form a single ...

" mountains, that is

revanchism

Revanchism (french: revanchisme, from ''revanche'', "revenge") is the political manifestation of the will to reverse territorial losses incurred by a country, often following a war or social movement. As a term, revanchism originated in 1870s Fr ...

and the patriotic urge to reclaim the

Alsace-Lorraine region which had been annexed by the German Empire with the 1871

Treaty of Frankfurt The Treaty of Frankfurt may refer to one of three treaties signed at Frankfurt, as follows:

* Treaty of Frankfurt (1489) - Treaty between Maximilian of Austria and the envoys of King Charles VIII of France

*Treaty of Frankfurt (1539) - Initiated ...

. Clemenceau actually made

Jules Ferry

Jules François Camille Ferry (; 5 April 183217 March 1893) was a French statesman and republican philosopher. He was one of the leaders of the Moderate Republicans and served as Prime Minister of France from 1880 to 1881 and 1883 to 1885. He ...

's cabinet fall after the 1885

Tonkin disaster. According to

Hannah Arendt in ''

The Origins of Totalitarianism

''The Origins of Totalitarianism'', published in 1951, was Hannah Arendt's first major work, wherein she describes and analyzes Nazism and Stalinism as the major totalitarian political movements of the first half of the 20th century.

History

...

'' (1951), this expansion of national sovereignty on overseas territories contradicted the unity of the

nation state

A nation state is a political unit where the state and nation are congruent. It is a more precise concept than "country", since a country does not need to have a predominant ethnic group.

A nation, in the sense of a common ethnicity, may i ...

which provided citizenship to its population. Thus, a tension between the

universalist will to respect human rights of the colonized people, as they may be considered as "citizens" of the nation state, and the imperialist drive to cynically

exploit populations deemed inferior began to surface. Some, in colonizing countries, opposed what they saw as unnecessary evils of the colonial administration when left to itself; as described in

Joseph Conrad's ''

Heart of Darkness'' (1899)—published around the same time as

Kipling

Joseph Rudyard Kipling ( ; 30 December 1865 – 18 January 1936)''The Times'', (London) 18 January 1936, p. 12. was an English novelist, short-story writer, poet, and journalist. He was born in British Raj, British India, which inspired much o ...

's ''

The White Man's Burden

"The White Man's Burden" (1899), by Rudyard Kipling, is a poem about the Philippine–American War (1899–1902) that exhorts the United States to assume colonial control of the Filipino people and their country.Hitchens, Christopher. ''Bl ...

''—or in

Louis-Ferdinand Céline

Louis Ferdinand Auguste Destouches (27 May 1894 – 1 July 1961), better known by the pen name Louis-Ferdinand Céline ( , ) was a French novelist, polemicist and physician. His first novel ''Journey to the End of the Night'' (1932) won the '' Pr ...

's ''

Journey to the End of the Night

''Journey to the End of the Night'' (french: Voyage au bout de la nuit, 1932) is the first novel by Louis-Ferdinand Céline. This semi-autobiographical work follows the adventures of Ferdinand Bardamu in the World War I, colonial Africa, the Un ...

'' (1932).

Colonial lobbies emerged to legitimise the Scramble for Africa and other expensive overseas adventures. In Germany, France, and Britain, the middle class often sought strong overseas policies to ensure the market's growth. Even in lesser powers, voices like

Enrico Corradini claimed a "place in the sun" for so-called "proletarian nations", bolstering nationalism and militarism in an early prototype of fascism.

Colonial propaganda and jingoism

A plethora of colonialist propaganda pamphlets, ideas, and imagery played on the colonial powers' psychology of popular jingoism and proud nationalism. A hallmark of the French colonial project in the late 19th century and early 20th century was the

civilizing mission

The civilizing mission ( es, misión civilizadora; pt, Missão civilizadora; french: Mission civilisatrice) is a political rationale for military intervention and for colonization purporting to facilitate the Westernization of indigenous pe ...

(''mission civilisatrice''), the principle that it was Europe's duty to bring civilisation to benighted peoples. As such, colonial officials undertook a policy of Franco-Europeanisation in French colonies, most notably

French West Africa and

Madagascar

Madagascar (; mg, Madagasikara, ), officially the Republic of Madagascar ( mg, Repoblikan'i Madagasikara, links=no, ; french: République de Madagascar), is an island country in the Indian Ocean, approximately off the coast of East Africa ...

. During the 19th century, French citizenship along with the right to elect a deputy to the French Chamber of Deputies was granted to the four old colonies of Guadeloupe, Martinique, Guyanne and Réunion as well as to the residents of the "

Four Communes

The Four Communes (French: ''Quatre Communes'') of Senegal were the four oldest colonial towns in French West Africa. In 1848 the French Second Republic, Second Republic extended the rights of full French citizenship to the inhabitants of Saint-L ...

" in Senegal. In most cases, the elected deputies were white Frenchmen, although there were some black deputies, such as the Senegalese

Blaise Diagne, who was elected in 1914.

[Segalla, Spencer. 2009, ''The Moroccan Soul: French Education, Colonial Ethnology, and Muslim Resistance, 1912–1956''. Nebraska University Press]

Colonial exhibitions

By the end of World War I the colonial empires had become very popular almost everywhere in Europe:

public opinion

Public opinion is the collective opinion on a specific topic or voting intention relevant to a society. It is the people's views on matters affecting them.

Etymology

The term "public opinion" was derived from the French ', which was first use ...

had been convinced of the needs of a colonial empire, although most of the metropolitans would never see a piece of it.

Colonial exhibition

A colonial exhibition was a type of international exhibition that was held to boost trade. During the 1880s and beyond, colonial exhibitions had the additional aim of bolstering popular support for the various colonial empires ...

s were instrumental in this change of popular mentalities brought about by the colonial propaganda, supported by the colonial lobby and by various scientists. Thus, conquests of territories were inevitably followed by public displays of the indigenous people for scientific and leisure purposes.

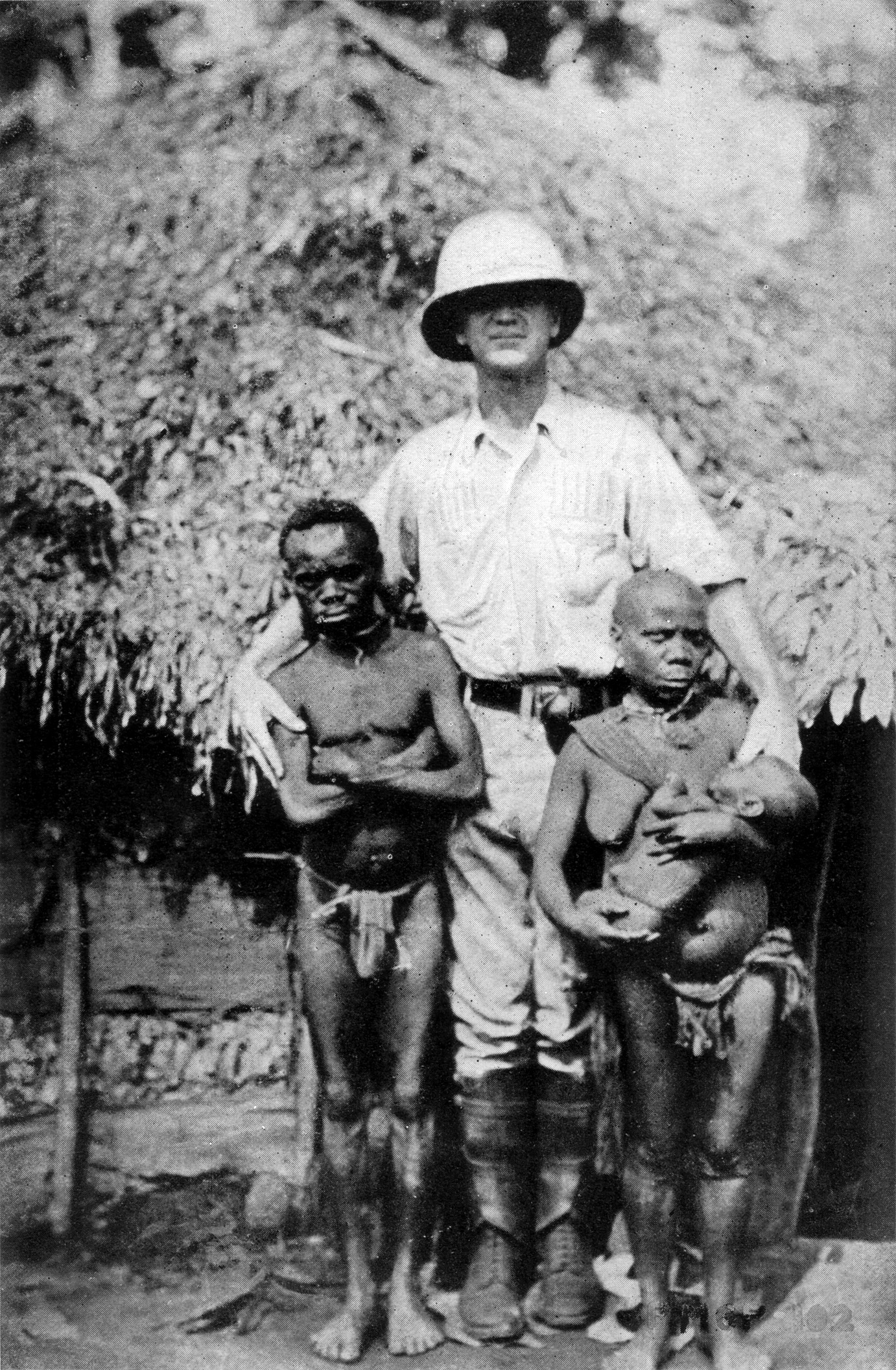

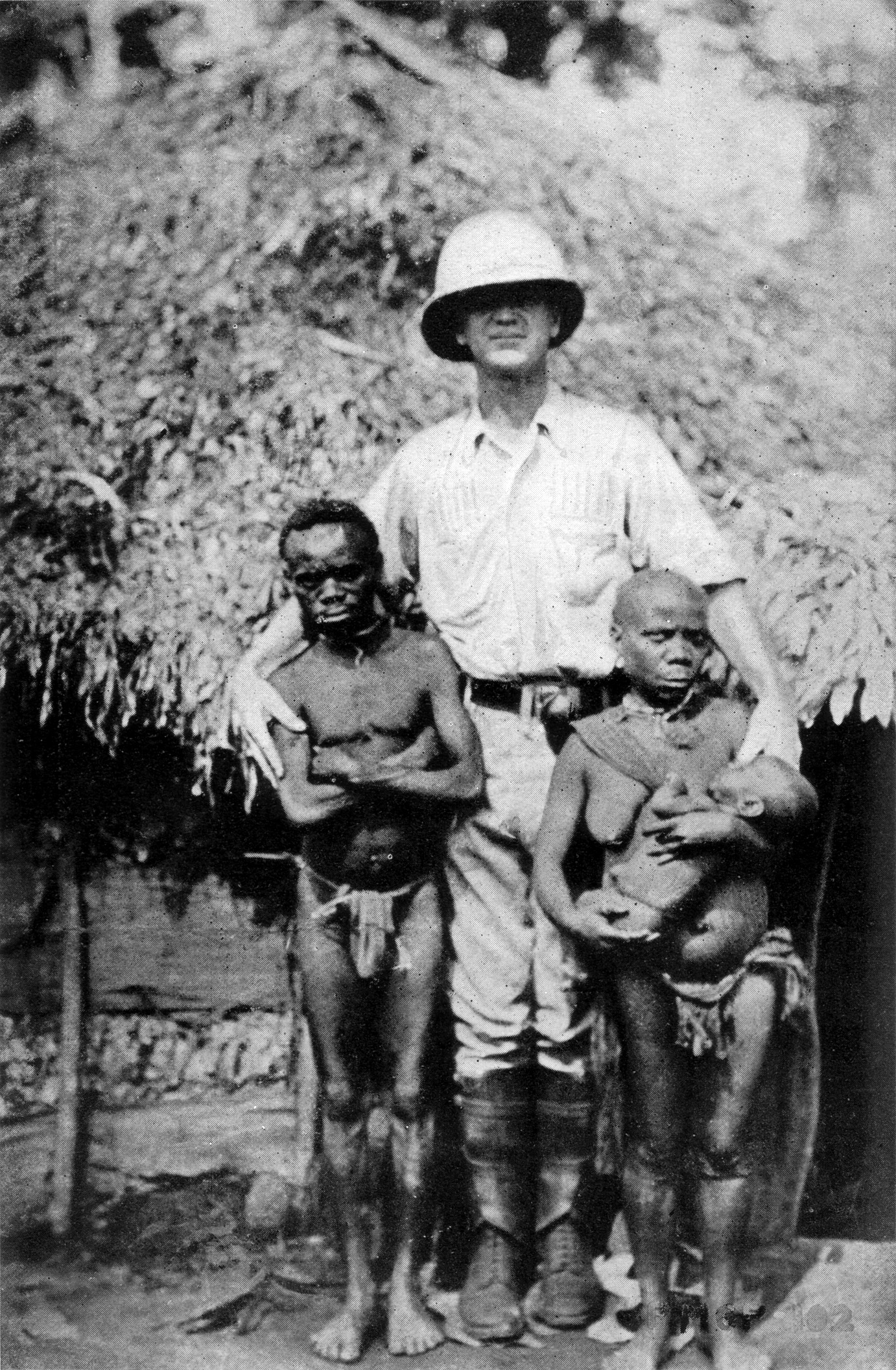

Carl Hagenbeck, a German merchant in wild animals and a future entrepreneur of most Europeans zoos, decided in 1874 to exhibit

Samoa

Samoa, officially the Independent State of Samoa; sm, Sāmoa, and until 1997 known as Western Samoa, is a Polynesian island country consisting of two main islands ( Savai'i and Upolu); two smaller, inhabited islands ( Manono and Apolima); ...

and

Sami people as "purely natural" populations. In 1876, he sent one of his collaborators to the newly conquered Egyptian Sudan to bring back some wild beasts and

Nubians

Nubians () ( Nobiin: ''Nobī,'' ) are an ethnic group indigenous to the region which is now northern Sudan and southern Egypt. They originate from the early inhabitants of the central Nile valley, believed to be one of the earliest cradles of ...

. Presented in Paris, London, and Berlin these Nubians were very successful. Such "

human zoos

Human zoos, also known as ethnological expositions, were public displays of people, usually in a so-called "natural" or "primitive" state. They were most prominent during the 19th and 20th centuries. These displays sometimes emphasized the sup ...

" could be found in Hamburg, Antwerp, Barcelona, London, Milan, New York City, Paris, etc., with 200,000 to 300,000 visitors attending each exhibition.

Tuaregs

The Tuareg people (; also spelled Twareg or Touareg; endonym: ''Imuhaɣ/Imušaɣ/Imašeɣăn/Imajeɣăn'') are a large Berber ethnic group that principally inhabit the Sahara in a vast area stretching from far southwestern Libya to southern ...

were exhibited after the French conquest of

Timbuktu

Timbuktu ( ; french: Tombouctou;

Koyra Chiini: ); tmh, label=Tuareg, script=Tfng, ⵜⵏⴱⴾⵜ, Tin Buqt a city in Mali, situated north of the Niger River. The town is the capital of the Tombouctou Region, one of the eight administrativ ...

(visited by

René Caillié

Auguste René Caillié (; 19 November 1799 – 17 May 1838) was a French explorer and the first European to return alive from the town of Timbuktu. Caillié had been preceded at Timbuktu by a British officer, Major Gordon Laing, who was murdere ...

, disguised as a Muslim, in 1828, thereby winning the prize offered by the French ''Société de Géographie'');

Malagasy after the occupation of Madagascar;

Amazons of

Abomey

Abomey is the capital of the Zou Department of Benin. The commune of Abomey covers an area of 142 square kilometres and, as of 2012, had a population of 90,195 people.

Abomey houses the Royal Palaces of Abomey, a collection of small traditional ...

after

Behanzin's mediatic defeat against the French in 1894. Not used to the climatic conditions, some of the indigenous died from exposure, such as some

Galibis in Paris in 1892.

Geoffroy de Saint-Hilaire, director of the

Jardin d'Acclimatation

The Jardin d'Acclimatation () is a children's amusement park located in the northern part of the Bois de Boulogne in Paris, alongside other attractions.

History

Opened on 6 October 1860 by Napoléon III and Empress Eugénie, this Paris zoo wa ...

, decided in 1877 to organise two "ethnological spectacles", presenting Nubians and

Inuit

Inuit (; iu, ᐃᓄᐃᑦ 'the people', singular: Inuk, , dual: Inuuk, ) are a group of culturally similar indigenous peoples inhabiting the Arctic and subarctic regions of Greenland, Labrador, Quebec, Nunavut, the Northwest Territories ...

. Ticket sales at the Jardin d'Acclimatation doubled, with a million paying entrances that year, a huge success for these times. Between 1877 and 1912, approximately thirty "ethnological exhibitions" were presented at the zoo. "Negro villages" were presented in Paris'

1878 World's Fair; the

1900 World's Fair presented the famous

diorama "living" in Madagascar, while the Colonial Exhibitions in Marseilles (1906 and 1922) and in Paris (1907 and 1931)displayed human beings in cages, often nudes or quasi-nudes. Nomadic "Senegalese villages" were also created, thus displaying the power of the colonial empire to all the population.

In the U.S.,

Madison Grant

Madison Grant (November 19, 1865 – May 30, 1937) was an American lawyer, zoologist, anthropologist, and writer known primarily for his work as a eugenicist and conservationist, and as an advocate of scientific racism. Grant is less noted f ...

, head of the New York Zoological Society, exposed

Pygmy

In anthropology, pygmy peoples are ethnic groups whose average height is unusually short. The term pygmyism is used to describe the phenotype of endemic short stature (as opposed to disproportionate dwarfism occurring in isolated cases in a pop ...

Ota Benga