Part C State on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

After the Indian independence in 1947, the

After the Indian independence in 1947, the

The termination of paramountcy meant that all rights flowing from the states' relationship with the British crown would return to them, leaving them free to negotiate relationships with the new states of India and Pakistan "on a basis of complete freedom". Early British plans for the transfer of power, such as the offer produced by the

The termination of paramountcy meant that all rights flowing from the states' relationship with the British crown would return to them, leaving them free to negotiate relationships with the new states of India and Pakistan "on a basis of complete freedom". Early British plans for the transfer of power, such as the offer produced by the

Mountbatten believed that securing the states' accession to India was crucial to reaching a negotiated settlement with the Congress for the transfer of power. As a relative of the British King, he was trusted by most of the princes and was a personal friend of many, especially the

Mountbatten believed that securing the states' accession to India was crucial to reaching a negotiated settlement with the Congress for the transfer of power. As a relative of the British King, he was trusted by most of the princes and was a personal friend of many, especially the

By far the most significant factor that led to the princes' decision to accede to India was the policy of the Congress and, in particular, of Patel and

By far the most significant factor that led to the princes' decision to accede to India was the policy of the Congress and, in particular, of Patel and

The limited scope of the Instruments of Accession and the promise of a wide-ranging autonomy and the other guarantees they offered, gave sufficient comfort to many rulers, who saw this as the best deal they could strike given the lack of support from the British, and popular internal pressures. Between May 1947 and the transfer of power on 15 August 1947, the vast majority of states signed Instruments of Accession. A few, however, held out. Some simply delayed signing the Instrument of Accession.

The limited scope of the Instruments of Accession and the promise of a wide-ranging autonomy and the other guarantees they offered, gave sufficient comfort to many rulers, who saw this as the best deal they could strike given the lack of support from the British, and popular internal pressures. Between May 1947 and the transfer of power on 15 August 1947, the vast majority of states signed Instruments of Accession. A few, however, held out. Some simply delayed signing the Instrument of Accession.

At the time of the transfer of power, the state of

At the time of the transfer of power, the state of

Hyderabad was a landlocked state that stretched over 82,000 square miles (over 212,000 square kilometres) in southeastern India. While 87% of its 17 million people were Hindu, its ruler Nizam Osman Ali Khan was a Muslim, and its politics were dominated by a Muslim elite. The Muslim nobility and the Ittehad-ul-Muslimeen, a powerful pro-Nizam Muslim party, insisted Hyderabad remain independent and stand on an equal footing to India and Pakistan. Accordingly, the Nizam in June 1947 issued a ''

Hyderabad was a landlocked state that stretched over 82,000 square miles (over 212,000 square kilometres) in southeastern India. While 87% of its 17 million people were Hindu, its ruler Nizam Osman Ali Khan was a Muslim, and its politics were dominated by a Muslim elite. The Muslim nobility and the Ittehad-ul-Muslimeen, a powerful pro-Nizam Muslim party, insisted Hyderabad remain independent and stand on an equal footing to India and Pakistan. Accordingly, the Nizam in June 1947 issued a ''

The Instruments of Accession were limited, transferring control of only three matters to India, and would by themselves have produced a rather loose federation, with significant differences in administration and governance across the various states. Full political integration, in contrast, would require a process whereby the political actors in the various states were "persuaded to shift their loyalties, expectations, and political activities towards a new center", namely, the

The Instruments of Accession were limited, transferring control of only three matters to India, and would by themselves have produced a rather loose federation, with significant differences in administration and governance across the various states. Full political integration, in contrast, would require a process whereby the political actors in the various states were "persuaded to shift their loyalties, expectations, and political activities towards a new center", namely, the

The integration of the princely states raised the question of the future of the remaining colonial

The integration of the princely states raised the question of the future of the remaining colonial

Nepal, Bhutan and Sikkim were Himalayan states bordering India.

Nepal, Bhutan and Sikkim were Himalayan states bordering India.

online free

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * Singh, Buta. "Role of Sardar Patel in the Integration of Indian States." ''Calcutta Historical Journal'' (July-Dec 2008) 28#2 pp 65–78. * * * * * , translated by Latika Padgaonkar * * * * * {{India topics Constitutional history of India History of the Republic of India Nehru administration Articles containing video clips

After the Indian independence in 1947, the

After the Indian independence in 1947, the dominion of India

The Dominion of India, officially the Union of India,* Quote: “The first collective use (of the word "dominion") occurred at the Colonial Conference (April to May 1907) when the title was conferred upon Canada and Australia. New Zealand and N ...

was divided into two sets of territories, one under direct British rule, and the other under the suzerainty

Suzerainty () is the rights and obligations of a person, state or other polity who controls the foreign policy and relations of a tributary state, while allowing the tributary state to have internal autonomy. While the subordinate party is cal ...

of the British Crown

The Crown is the state (polity), state in all its aspects within the jurisprudence of the Commonwealth realms and their subdivisions (such as the Crown Dependencies, British Overseas Territories, overseas territories, Provinces and territorie ...

, with control over their internal affairs remaining in the hands of their hereditary rulers. The latter included 562 princely state

A princely state (also called native state or Indian state) was a nominally sovereign entity of the British Raj, British Indian Empire that was not directly governed by the British, but rather by an Indian ruler under a form of indirect rule, ...

s, having different types of revenue sharing arrangements with the British, often depending on their size, population and local conditions. In addition, there were several colonial enclaves controlled by France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

and Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of ...

. The political integration of these territories into an Indian Union was a declared objective of the Indian National Congress

The Indian National Congress (INC), colloquially the Congress Party but often simply the Congress, is a political party in India with widespread roots. Founded in 1885, it was the first modern nationalist movement to emerge in the British Em ...

, and the Government of India

The Government of India (ISO: ; often abbreviated as GoI), known as the Union Government or Central Government but often simply as the Centre, is the national government of the Republic of India, a federal democracy located in South Asia, c ...

pursued this over the next decade. Through a combination of factors, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel and V. P. Menon

Rao Bahadur Vappala Pangunni Menon, CSI, CIE (30 September 1893 – 31 December 1965) was an Indian civil servant who served as Secretary to the Government of India in the Ministry of the States, under Sardar Patel.

By appointment from V ...

coerced and coalesced the rulers of the various princely states to accede to India. Having secured their accession, they then proceeded, in a step-by-step process, to secure and extend the union government's authority over these states and transform their administrations until, by 1956, there was little difference between the territories that had been part of British India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance on the Indian subcontinent. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one ...

and those that had been princely states. Simultaneously, the Government of India, through a combination of military and diplomatic means, acquired ''de facto'' and ''de jure

In law and government, ''de jure'' ( ; , "by law") describes practices that are legally recognized, regardless of whether the practice exists in reality. In contrast, ("in fact") describes situations that exist in reality, even if not legally ...

'' control over the remaining colonial enclaves, which too were integrated into India.

Although this process successfully integrated the vast majority of princely states into India, it was not as successful for a few, notably the former princely states of Jammu and Kashmir Jammu and Kashmir may refer to:

* Kashmir, the northernmost geographical region of the Indian subcontinent

* Jammu and Kashmir (union territory), a region administered by India as a union territory

* Jammu and Kashmir (state), a region administered ...

and Manipur

Manipur () ( mni, Kangleipak) is a state in Northeast India, with the city of Imphal as its capital. It is bounded by the Indian states of Nagaland to the north, Mizoram to the south and Assam to the west. It also borders two regions of Myanm ...

, where active secessionist and separatist insurgencies continued to exist due to various reasons.

Princely states in India

The early history of British expansion in India was characterised by the co-existence of two approaches towards the existing princely states. The first was a policy ofannexation

Annexation (Latin ''ad'', to, and ''nexus'', joining), in international law, is the forcible acquisition of one state's territory by another state, usually following military occupation of the territory. It is generally held to be an illegal act ...

, where the British sought to forcibly absorb the Indian princely states into the provinces which constituted their Empire in India. The second was a policy of indirect rule, where the British assumed paramountcy over princely states, but conceded to them sovereignty

Sovereignty is the defining authority within individual consciousness, social construct, or territory. Sovereignty entails hierarchy within the state, as well as external autonomy for states. In any state, sovereignty is assigned to the perso ...

and varying degrees of internal self-government. During the early part of the 19th century, the policy of the British tended towards annexation, but the Indian Rebellion of 1857

The Indian Rebellion of 1857 was a major uprising in India in 1857–58 against the rule of the British East India Company, which functioned as a sovereign power on behalf of the British Crown. The rebellion began on 10 May 1857 in the fo ...

forced a change in this approach, by demonstrating both the difficulty of absorbing and subduing annexed states, and the usefulness of princely states as a source of support. In 1858, the policy of annexation was formally renounced, and British relations with the remaining princely states thereafter were based on subsidiary alliances, whereby the British exercised paramountcy over all princely states, with the British crown

The Crown is the state (polity), state in all its aspects within the jurisprudence of the Commonwealth realms and their subdivisions (such as the Crown Dependencies, British Overseas Territories, overseas territories, Provinces and territorie ...

as ultimate suzerain

Suzerainty () is the rights and obligations of a person, state or other polity who controls the foreign policy and relations of a tributary state, while allowing the tributary state to have internal autonomy. While the subordinate party is calle ...

, but at the same time respected and protected them as allies, taking control of their external relations. The exact relations between the British and each princely state were regulated by individual treaties and varied widely, with some states having complete internal self-government, others being subject to significant control in their internal affairs, and some rulers being in effect little more than the owners of landed estates, with little autonomy.

During the 20th century, the British made several attempts to integrate the princely states more closely with British India, in 1921 creating the Chamber of Princes as a consultative and advisory body, and in 1936 transferring the responsibility for the supervision of smaller states from the provinces to the centre and creating direct relations between the Government of India

The Government of India (ISO: ; often abbreviated as GoI), known as the Union Government or Central Government but often simply as the Centre, is the national government of the Republic of India, a federal democracy located in South Asia, c ...

and the larger princely states, superseding political agents. A more ambitious aim was a scheme of federation contained in the Government of India Act 1935

The Government of India Act, 1935 was an Act adapted from the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It originally received royal assent in August 1935. It was the longest Act of (British) Parliament ever enacted until the Greater London Authority ...

, which envisaged the princely states and British India being united under a federal government. This scheme came close to success, but was abandoned in 1939 as a result of the outbreak of the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

. As a result, in the 1940s the relationship between the princely states and the crown remained regulated by the principle of paramountcy and by the various treaties between the British crown and the states.

Neither paramountcy nor the subsidiary alliances

A subsidiary alliance, in History of South Asia, South Asian history, was a Tributary state, tributary alliance between a Princely state, South Asian state and a European East India Company (disambiguation), East India Company.

Under this s ...

could continue after Indian independence. The British took the view that because they had been established directly between the British crown and the princely states, they could not be transferred to the newly independent dominion

The term ''Dominion'' is used to refer to one of several self-governing nations of the British Empire.

"Dominion status" was first accorded to Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Newfoundland, South Africa, and the Irish Free State at the 1926 ...

s of India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

and Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 24 ...

. At the same time, the alliances imposed obligations on Britain that it was not prepared to continue to carry out, such as the obligation to maintain troops in India for the defence of the princely states. The British government therefore decided that paramountcy, together with all treaties between them and the princely states, would come to an end upon the British departure from India.

Reasons for integration

The termination of paramountcy meant that all rights flowing from the states' relationship with the British crown would return to them, leaving them free to negotiate relationships with the new states of India and Pakistan "on a basis of complete freedom". Early British plans for the transfer of power, such as the offer produced by the

The termination of paramountcy meant that all rights flowing from the states' relationship with the British crown would return to them, leaving them free to negotiate relationships with the new states of India and Pakistan "on a basis of complete freedom". Early British plans for the transfer of power, such as the offer produced by the Cripps Mission

The Cripps Mission was a failed attempt in late March 1942 by the British government to secure full Indian cooperation and support for their efforts in World War II. The mission was headed by a senior minister Stafford Cripps. Cripps belonged to th ...

, recognised the possibility that some princely states might choose to stand out of independent India. This was unacceptable to the Indian National Congress

The Indian National Congress (INC), colloquially the Congress Party but often simply the Congress, is a political party in India with widespread roots. Founded in 1885, it was the first modern nationalist movement to emerge in the British Em ...

, which regarded the independence of princely states as a denial of the course of Indian history, and consequently regarded this scheme as a "Balkanisation

Balkanization is the fragmentation of a larger region or state into smaller regions or states, which may be hostile or uncooperative with one another. It is usually caused by differences of ethnicity, culture, and religion and some other factor ...

" of India. The Congress had traditionally been less active in the princely states because of their limited resources which restricted their ability to organise there and their focus on the goal of independence from the British, and because Congress leaders, in particular Mohandas Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (; ; 2 October 1869 – 30 January 1948), popularly known as Mahatma Gandhi, was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist Quote: "... marks Gandhi as a hybrid cosmopolitan figure who transformed ... anti- ...

, were sympathetic to the more progressive princes as examples of the capacity of Indians to rule themselves. This changed in the 1930s as a result of the federation scheme contained in the Government of India Act 1935 and the rise of socialist Congress leaders such as Jayaprakash Narayan, and the Congress began to actively engage with popular political and labour activity in the princely states. By 1939, the Congress's formal stance was that the states must enter independent India, on the same terms and with the same autonomy as the provinces of British India, and with their people granted responsible government. As a result, it attempted to insist on the incorporation of the princely states into India in its negotiations with the British, but the British took the view that this was not in their power to grant.

A few British leaders, particularly Lord Mountbatten

Louis Francis Albert Victor Nicholas Mountbatten, 1st Earl Mountbatten of Burma (25 June 1900 – 27 August 1979) was a British naval officer, colonial administrator and close relative of the British royal family. Mountbatten, who was of German ...

, the last British viceroy of India

The Governor-General of India (1773–1950, from 1858 to 1947 the Viceroy and Governor-General of India, commonly shortened to Viceroy of India) was the representative of the monarch of the United Kingdom and after Indian independence in 19 ...

, were also uncomfortable with breaking links between independent India and the princely states. The development of trade, commerce and communications during the 19th and 20th centuries had bound the princely states to the British India through a complex network of interests. Agreements relating to railways, customs, irrigation, use of ports, and other similar agreements would get terminated, posing a serious threat to the economic life of the subcontinent. Mountbatten was also persuaded by the argument of Indian officials such as V. P. Menon

Rao Bahadur Vappala Pangunni Menon, CSI, CIE (30 September 1893 – 31 December 1965) was an Indian civil servant who served as Secretary to the Government of India in the Ministry of the States, under Sardar Patel.

By appointment from V ...

that the integration of the princely states into independent India would, to some extent, assuage the wounds of partition

Partition may refer to:

Computing Hardware

* Disk partitioning, the division of a hard disk drive

* Memory partition, a subdivision of a computer's memory, usually for use by a single job

Software

* Partition (database), the division of a ...

. The result was that Mountbatten personally favoured and worked towards the accession of princely states to India following the transfer of power, as proposed by the Congress.

Accepting integration

The princes' position

The rulers of the princely states were not uniformly enthusiastic about integrating their domains into independent India. The Jamkhandi State integrated first with Independent India. Some, such as the rulers ofBikaner

Bikaner () is a city in the northwest of the state of Rajasthan, India. It is located northwest of the state capital, Jaipur. Bikaner city is the administrative headquarters of Bikaner District and Bikaner division.

Formerly the capital of ...

and Jawhar

Jawhar is a city and a municipal council in Palghar district of Maharashtra state in Konkan division of India. Jawhar was a capital city of the erstwhile Koli princely state of Jawhar.

Situated in the ranges of the Western Ghats, Jawhar is k ...

, were motivated to join India out of ideological and patriotic considerations, but others insisted that they had the right to join either India or Pakistan, to remain independent, or form a union of their own. Bhopal

Bhopal (; ) is the capital city of the Indian state of Madhya Pradesh and the administrative headquarters of both Bhopal district and Bhopal division. It is known as the ''City of Lakes'' due to its various natural and artificial lakes. It i ...

, Travancore

The Kingdom of Travancore ( /ˈtrævənkɔːr/), also known as the Kingdom of Thiruvithamkoor, was an Indian kingdom from c. 1729 until 1949. It was ruled by the Travancore Royal Family from Padmanabhapuram, and later Thiruvananthapuram. At ...

and Hyderabad

Hyderabad ( ; , ) is the capital and largest city of the Indian state of Telangana and the ''de jure'' capital of Andhra Pradesh. It occupies on the Deccan Plateau along the banks of the Musi River (India), Musi River, in the northern part ...

announced that they did not intend to join either dominion. Hyderabad went as far as to appoint trade representatives in European countries and commencing negotiations with the Portuguese to lease or buy Goa

Goa () is a state on the southwestern coast of India within the Konkan region, geographically separated from the Deccan highlands by the Western Ghats. It is located between the Indian states of Maharashtra to the north and Karnataka to the ...

to give it access to the sea, and Travancore pointed to the strategic importance to Western countries of its thorium

Thorium is a weakly radioactive metallic chemical element with the symbol Th and atomic number 90. Thorium is silvery and tarnishes black when it is exposed to air, forming thorium dioxide; it is moderately soft and malleable and has a high me ...

reserves while asking for recognition. Some states proposed a subcontinent-wide confederation

A confederation (also known as a confederacy or league) is a union of sovereign groups or states united for purposes of common action. Usually created by a treaty, confederations of states tend to be established for dealing with critical issu ...

of princely states, as a third entity in addition to India and Pakistan. Bhopal attempted to build an alliance between the princely states and the Muslim League to counter the pressure being put on rulers by the Congress.

A number of factors contributed to the collapse of this initial resistance and to nearly all non-Muslim majority princely states agreeing to accede to India. An important factor was the lack of unity among the princes. The smaller states did not trust the larger states to protect their interests, and many Hindu

Hindus (; ) are people who religiously adhere to Hinduism.Jeffery D. Long (2007), A Vision for Hinduism, IB Tauris, , pages 35–37 Historically, the term has also been used as a geographical, cultural, and later religious identifier for ...

rulers did not trust Muslim

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

princes, in particular Hamidullah Khan

Hajji Nawab Hafiz Sir Hamidullah Khan (9 September 1894 – 4 February 1960) was the last ruling Nawab of the princely salute state of Bhopal. He ruled from 1926 when his mother, Begum Kaikhusrau Jahan Begum, abdicated in his favor, until 19 ...

, the Nawab of Bhopal

The Nawabs of Bhopal were the Muslim rulers of Bhopal, now part of Madhya Pradesh, India. The nawabs first ruled under the Mughal Empire from 1707 to 1737, under the Maratha Empire from 1737 to 1818, then under British rule from 1818 to 1947, an ...

and a leading proponent of independence, whom they viewed as an agent for Pakistan. Others, believing integration to be inevitable, sought to build bridges with the Congress, hoping thereby to gain a say in shaping the final settlement. The resultant inability to present a united front or agree on a common position significantly reduced their bargaining power in negotiations with the Congress. The decision by the Muslim League to stay out of the Constituent Assembly

A constituent assembly (also known as a constitutional convention, constitutional congress, or constitutional assembly) is a body assembled for the purpose of drafting or revising a constitution. Members of a constituent assembly may be elected b ...

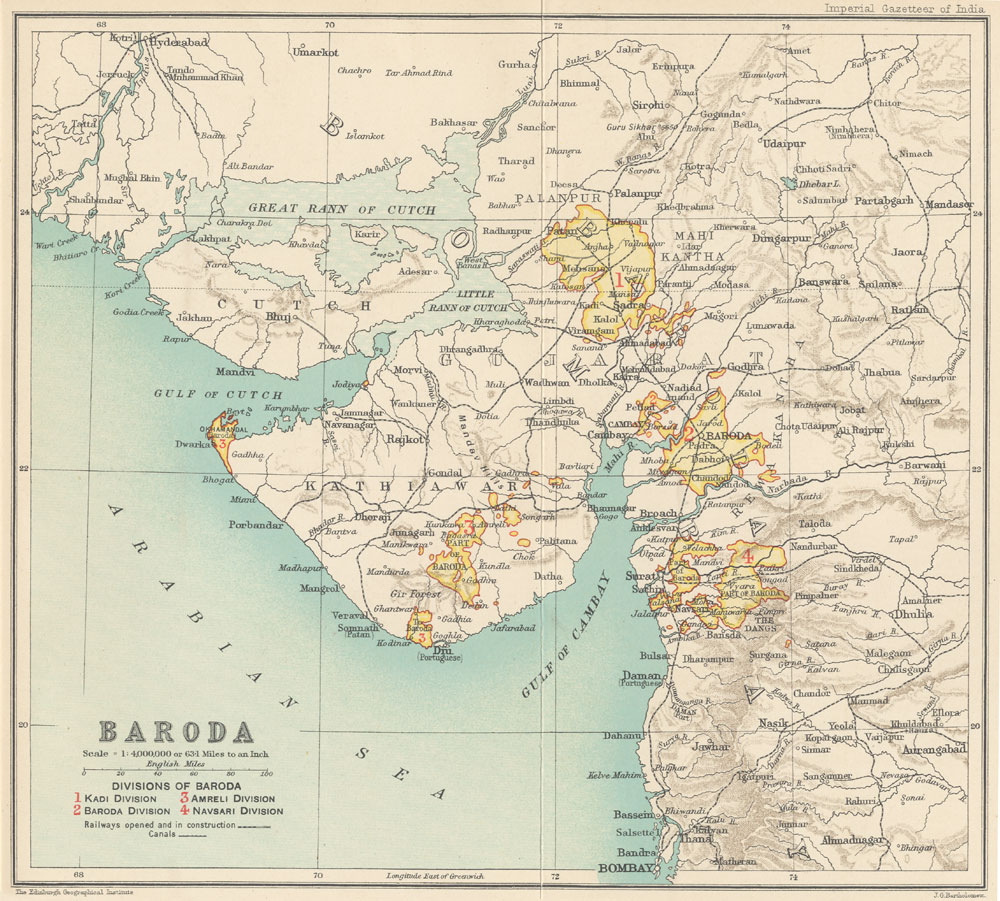

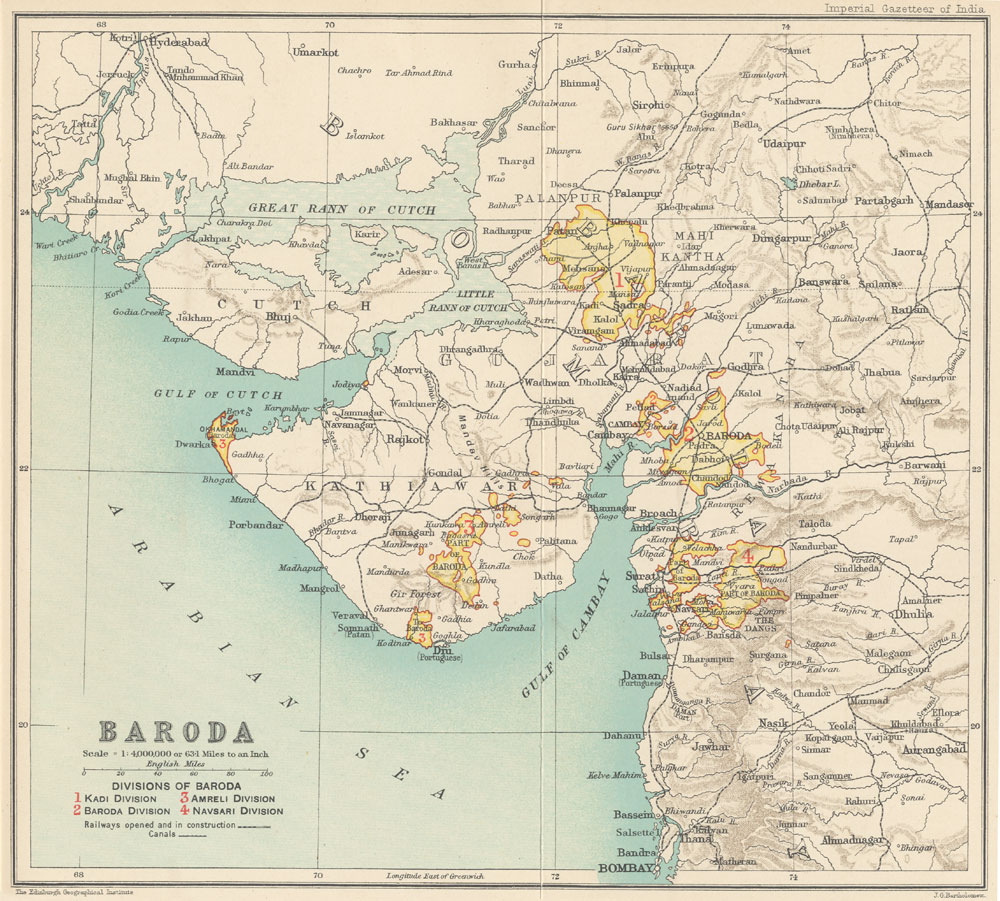

was also fatal to the princes' plan to build an alliance with it to counter the Congress, and attempts to boycott the Constituent Assembly altogether failed on 28 April 1947, when the states of Baroda

Vadodara (), also known as Baroda, is the second largest city in the Indian state of Gujarat. It serves as the administrative headquarters of the Vadodara district and is situated on the banks of the Vishwamitri River, from the state capital ...

, Bikaner

Bikaner () is a city in the northwest of the state of Rajasthan, India. It is located northwest of the state capital, Jaipur. Bikaner city is the administrative headquarters of Bikaner District and Bikaner division.

Formerly the capital of ...

, Cochin

Kochi (), also known as Cochin ( ) ( the official name until 1996) is a major port city on the Malabar Coast of India bordering the Laccadive Sea, which is a part of the Arabian Sea. It is part of the district of Ernakulam in the state of K ...

, Gwalior

Gwalior() is a major city in the central Indian state of Madhya Pradesh; it lies in northern part of Madhya Pradesh and is one of the Counter-magnet cities. Located south of Delhi, the capital city of India, from Agra and from Bhopal, the s ...

, Jaipur

Jaipur (; Hindi Language, Hindi: ''Jayapura''), formerly Jeypore, is the List of state and union territory capitals in India, capital and largest city of the Indian States and union territories of India, state of Rajasthan. , the city had a pop ...

, Jodhpur

Jodhpur (; ) is the second-largest city in the Indian state of Rajasthan and officially the second metropolitan city of the state. It was formerly the seat of the princely state of Jodhpur State. Jodhpur was historically the capital of the Ki ...

, Patiala

Patiala () is a city in southeastern Punjab, India, Punjab, northwestern India. It is the fourth largest city in the state and is the administrative capital of Patiala district. Patiala is located around the ''Qila Mubarak, Patiala, Qila Mubarak ...

and Rewa

Rewa may refer to:

Places Fiji

* Rewa (Fijian Communal Constituency, Fiji), a former electoral division of Fiji

* Rewa Plateau, between the Kaimur and Vindhya Ranges in Madhya Pradesh

* Rewa Province, Fiji

* Rewa River, the widest river in Fiji

...

took their seats in the Assembly.

Many princes were also pressured by popular sentiment favouring integration with India, which meant their plans for independence had little support from their subjects. The Maharaja of Travancore, for example, definitively abandoned his plans for independence after the attempted assassination of his dewan, Sir C. P. Ramaswami Iyer

Sir Chetput Pattabhiraman Ramaswami Iyer (12 November 1879 – 26 September 1966), popularly known as Sir C. P., was an Indian lawyer, administrator and politician who served as the Advocate-General of Madras Presidency from 1920 to 1923, Law ...

. In a few states, the chief ministers or dewans played a significant role in convincing the princes to accede to India. The key factors that led the states to accept integration into India were, however, the efforts of Lord Mountbatten

Louis Francis Albert Victor Nicholas Mountbatten, 1st Earl Mountbatten of Burma (25 June 1900 – 27 August 1979) was a British naval officer, colonial administrator and close relative of the British royal family. Mountbatten, who was of German ...

, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel

Vallabhbhai Jhaverbhai Patel (; ; 31 October 1875 – 15 December 1950), commonly known as Sardar, was an Indian lawyer, influential political leader, barrister and statesman who served as the first Deputy Prime Minister and Home Minister of I ...

and V. P. Menon

Rao Bahadur Vappala Pangunni Menon, CSI, CIE (30 September 1893 – 31 December 1965) was an Indian civil servant who served as Secretary to the Government of India in the Ministry of the States, under Sardar Patel.

By appointment from V ...

. The latter two were respectively the political and administrative heads of the States Department

The States Department, later States Ministry, was a department of the Government of India headed by the Minister of States. Its responsibility was to deal with the princely states and manage their relationship with independent India.

The departm ...

, which was in charge of relations with the princely states.

Mountbatten's role

Mountbatten believed that securing the states' accession to India was crucial to reaching a negotiated settlement with the Congress for the transfer of power. As a relative of the British King, he was trusted by most of the princes and was a personal friend of many, especially the

Mountbatten believed that securing the states' accession to India was crucial to reaching a negotiated settlement with the Congress for the transfer of power. As a relative of the British King, he was trusted by most of the princes and was a personal friend of many, especially the Nawab of Bhopal

The Nawabs of Bhopal were the Muslim rulers of Bhopal, now part of Madhya Pradesh, India. The nawabs first ruled under the Mughal Empire from 1707 to 1737, under the Maratha Empire from 1737 to 1818, then under British rule from 1818 to 1947, an ...

, Hamidullah Khan

Hajji Nawab Hafiz Sir Hamidullah Khan (9 September 1894 – 4 February 1960) was the last ruling Nawab of the princely salute state of Bhopal. He ruled from 1926 when his mother, Begum Kaikhusrau Jahan Begum, abdicated in his favor, until 19 ...

. The princes also believed that he would be in a position to ensure that independent India adhered to any terms that might be agreed upon, because Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru (; ; ; 14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat—

*

*

*

* and author who was a central figure in India during the middle of the 20t ...

and Patel had asked him to become the first Governor General

Governor-general (plural ''governors-general''), or governor general (plural ''governors general''), is the title of an office-holder. In the context of governors-general and former British colonies, governors-general are appointed as viceroy t ...

of the Dominion of India

The Dominion of India, officially the Union of India,* Quote: “The first collective use (of the word "dominion") occurred at the Colonial Conference (April to May 1907) when the title was conferred upon Canada and Australia. New Zealand and N ...

.

Mountbatten used his influence with the princes to push them towards accession. He declared that the British Government would not grant dominion status to any of the princely states, nor would it accept them into the British Commonwealth, which meant that the British Crown would sever all connections with the states unless they joined either India or Pakistan. He pointed out that the Indian subcontinent

The Indian subcontinent is a list of the physiographic regions of the world, physiographical region in United Nations geoscheme for Asia#Southern Asia, Southern Asia. It is situated on the Indian Plate, projecting southwards into the Indian O ...

was one economic entity, and that the states would suffer most if the link were broken. He also pointed to the difficulties that princes would face maintaining order in the face of threats such as the rise of communal violence

Communal violence is a form of violence that is perpetrated across ethnic or communal lines, the violent parties feel solidarity for their respective groups, and victims are chosen based upon group membership. The term includes conflicts, riots ...

and communist movements

The Communist International (Comintern), also known as the Third International, was a Soviet-controlled international organization founded in 1919 that advocated world communism. The Comintern resolved at its Second Congress to "struggle by ...

.

Mountbatten stressed that he would act as the trustee of the princes' commitment, as he would be serving as India's head of state well into 1948. He engaged in a personal dialogue with reluctant princes, such as the Nawab of Bhopal, who he asked through a confidential letter to sign the Instrument of Accession making Bhopal part of India, which Mountbatten would keep locked up in his safe. It would be handed to the States Department on 15 August only if the Nawab did not change his mind before then, which he was free to do. The Nawab agreed, and did not renege over the deal.

At the time, several princes complained that they were being betrayed by Britain, who they regarded as an ally, and Sir Conrad Corfield

Sir Conrad Laurence Corfield KCIE, CSI, MC, (15 August 1893 – 3 October 1980), was a British civil servant and the private secretary to several viceroys of India, including Lord Mountbatten. He also was the author of the book ''The Princely ...

resigned his position as head of the Political Department in protest at Mountbatten's policies. Mountbatten's policies were also criticised by the opposition Conservative Party

The Conservative Party is a name used by many political parties around the world. These political parties are generally right-wing though their exact ideologies can range from center-right to far-right.

Political parties called The Conservative P ...

. Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

compared the language used by the Indian government with that used by Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

before the invasion of Austria. Modern historians such as Lumby and Moore, however, take the view that Mountbatten played a crucial role in ensuring that the princely states agreed to accede to India.

Pressure and diplomacy

By far the most significant factor that led to the princes' decision to accede to India was the policy of the Congress and, in particular, of Patel and

By far the most significant factor that led to the princes' decision to accede to India was the policy of the Congress and, in particular, of Patel and Menon Menon may refer to:

People

*Menon (subcaste), an honorary title accorded to some members of the Nair community of Kerala, southern India; used as a surname by many holders of the title

Surnamed

*Menon (surname), the surname of several people

Give ...

. The Congress' stated position was that the princely states were not sovereign entities, and as such could not opt to be independent notwithstanding the end of paramountcy. The princely states must therefore accede to either India or Pakistan. In July 1946, Nehru pointedly observed that no princely state could prevail militarily against the army of independent India. In January 1947, he said that independent India would not accept the divine right of kings

In European Christianity, the divine right of kings, divine right, or God's mandation is a political and religious doctrine of political legitimacy of a monarchy. It stems from a specific metaphysical framework in which a monarch is, before b ...

, and in May 1947, he declared that any princely state which refused to join the Constituent Assembly would be treated as an enemy state. Other Congress leaders, such as C. Rajagopalachari, argued that as paramountcy "came into being as a fact and not by agreement", it would necessarily pass to the government of independent India, as the successor of the British.

Patel and Menon, who were charged with the actual job of negotiating with the princes, took a more conciliatory approach than Nehru. The official policy statement of the Government of India made by Patel on 5 July 1947 made no threats. Instead, it emphasised the unity of India and the common interests of the princes and independent India, reassured them about the Congress' intentions, and invited them to join independent India "to make laws sitting together as friends than to make treaties as aliens". He reiterated that the States Department would not attempt to establish a relationship of domination over the princely states. Unlike the Political Department of the British Government, it would not be an instrument of paramountcy, but a medium whereby business could be conducted between the states and India as equals.

Instruments of accession

Patel and Menon backed up their diplomatic efforts by producing treaties that were designed to be attractive to rulers of princely states. Two key documents were produced. The first was theStandstill Agreement

The term standstill agreement refers to various forms of agreement which businesses may enter into in order to delay action which might otherwise take place.

A standstill agreement may be used as a form of defence to a hostile takeover, when a t ...

, which confirmed the continuance of the pre-existing agreements and administrative practices. The second was the Instrument of Accession, by which the ruler of the princely state in question agreed to the accession of his kingdom to independent India, granting the latter control over specified subject matters. The nature of the subject matters varied depending on the acceding state. The states which had internal autonomy under the British signed an Instrument of Accession which only ceded three subjects to the government of India—defence, external affairs, and communications, each defined in accordance with List 1 to Schedule VII of the Government of India Act 1935

The Government of India Act, 1935 was an Act adapted from the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It originally received royal assent in August 1935. It was the longest Act of (British) Parliament ever enacted until the Greater London Authority ...

. Rulers of states which were in effect estates or taluk

A tehsil (, also known as tahsil, taluka, or taluk) is a local unit of administrative division in some countries of South Asia. It is a subdistrict of the area within a district including the designated populated place that serves as its administr ...

as, where substantial administrative powers were exercised by the Crown, signed a different Instrument of Accession, which vested all residuary powers and jurisdiction in the Government of India. Rulers of states which had an intermediate status signed a third type of Instrument, which preserved the degree of power they had under the British.

The Instruments of Accession implemented a number of other safeguards. Clause 7 provided that the princes would not be bound to the Indian constitution as and when it was drafted. Clause 8 guaranteed their autonomy in all areas that were not ceded to the Government of India. This was supplemented by a number of promises. Rulers who agreed to accede would receive guarantees that their extra-territorial

In international law, extraterritoriality is the state of being exempted from the jurisdiction of local law, usually as the result of diplomatic negotiations.

Historically, this primarily applied to individuals, as jurisdiction was usually cla ...

rights, such as immunity from prosecution

Legal immunity, or immunity from prosecution, is a legal status wherein an individual or entity cannot be held liable for a violation of the law, in order to facilitate societal aims that outweigh the value of imposing liability in such cases. Su ...

in Indian courts and exemption from customs duty, would be protected, that they would be allowed to democratise slowly, that none of the eighteen major states would be forced to merge, and that they would remain eligible for British honours and decorations. In discussions, Lord Mountbatten reinforced the statements of Patel and Menon by emphasising that the documents gave the princes all the "practical independence" they needed. Mountbatten, Patel and Menon also sought to give princes the impression that if they did not accept the terms put to them then, they might subsequently need to accede on substantially less favourable terms. The Standstill Agreement was also used as a negotiating tool, as the States Department categorically ruled out signing a Standstill Agreement with princely states that did not sign an Instrument of Accession.

Accession process

The limited scope of the Instruments of Accession and the promise of a wide-ranging autonomy and the other guarantees they offered, gave sufficient comfort to many rulers, who saw this as the best deal they could strike given the lack of support from the British, and popular internal pressures. Between May 1947 and the transfer of power on 15 August 1947, the vast majority of states signed Instruments of Accession. A few, however, held out. Some simply delayed signing the Instrument of Accession.

The limited scope of the Instruments of Accession and the promise of a wide-ranging autonomy and the other guarantees they offered, gave sufficient comfort to many rulers, who saw this as the best deal they could strike given the lack of support from the British, and popular internal pressures. Between May 1947 and the transfer of power on 15 August 1947, the vast majority of states signed Instruments of Accession. A few, however, held out. Some simply delayed signing the Instrument of Accession. Piploda

Piploda is a town and a Nagar Parishad in Ratlam district in the Indian state of Madhya Pradesh.

History

Before Indian independence, Piploda was the capital of the princely state of the same name. It was ruled by Rajputs of the Dodiya clan ...

, a small state in central India, did not accede until March 1948. The biggest problems, however, arose with a few border states, such as Jodhpur

Jodhpur (; ) is the second-largest city in the Indian state of Rajasthan and officially the second metropolitan city of the state. It was formerly the seat of the princely state of Jodhpur State. Jodhpur was historically the capital of the Ki ...

, which tried to negotiate better deals with Pakistan, with Junagadh, which actually did accede to Pakistan, and with Hyderabad

Hyderabad ( ; , ) is the capital and largest city of the Indian state of Telangana and the ''de jure'' capital of Andhra Pradesh. It occupies on the Deccan Plateau along the banks of the Musi River (India), Musi River, in the northern part ...

and Kashmir

Kashmir () is the northernmost geographical region of the Indian subcontinent. Until the mid-19th century, the term "Kashmir" denoted only the Kashmir Valley between the Great Himalayas and the Pir Panjal Range. Today, the term encompas ...

, which decided to remain independent.

Border states

The ruler ofJodhpur

Jodhpur (; ) is the second-largest city in the Indian state of Rajasthan and officially the second metropolitan city of the state. It was formerly the seat of the princely state of Jodhpur State. Jodhpur was historically the capital of the Ki ...

, Hanwant Singh

Raj Rajeshwar Maharajadhiraj Shri Hanwant Singh Rathore of Jodhpur (16 June 1923 – 26 January 1952) was the ruler of the Indian princely state of Jodhpur. He succeeded his father as Maharaja of Jodhpur on 9 June 1947 and held the title till ...

, was antipathetic to the Congress, and did not see much future in India for him or the lifestyle he wished to lead. Along with the ruler of Jaisalmer

Jaisalmer , nicknamed "The Golden city", is a city in the Indian state of Rajasthan, located west of the state capital Jaipur. The town stands on a ridge of yellowish sandstone and is crowned by the ancient Jaisalmer Fort. This fort contains a ...

, he entered into negotiations with Muhammad Ali Jinnah

Muhammad Ali Jinnah (, ; born Mahomedali Jinnahbhai; 25 December 1876 – 11 September 1948) was a barrister, politician, and the founder of Pakistan. Jinnah served as the leader of the All-India Muslim League from 1913 until the ...

, who was the designated head of state for Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 24 ...

. Jinnah was keen to attract some of the larger border states, hoping thereby to attract other Rajput

Rajput (from Sanskrit ''raja-putra'' 'son of a king') is a large multi-component cluster of castes, kin bodies, and local groups, sharing social status and ideology of genealogical descent originating from the Indian subcontinent. The term Ra ...

states to Pakistan and compensate for the loss of half of Bengal

Bengal ( ; bn, বাংলা/বঙ্গ, translit=Bānglā/Bôngô, ) is a geopolitical, cultural and historical region in South Asia, specifically in the eastern part of the Indian subcontinent at the apex of the Bay of Bengal, predom ...

and Punjab

Punjab (; Punjabi: پنجاب ; ਪੰਜਾਬ ; ; also romanised as ''Panjāb'' or ''Panj-Āb'') is a geopolitical, cultural, and historical region in South Asia, specifically in the northern part of the Indian subcontinent, comprising ...

. He offered to permit Jodhpur and Jaisalmer to accede to Pakistan on any terms they chose, giving their rulers blank sheets of paper and asking them to write down their terms, which he would sign. Jaisalmer refused, arguing that it would be difficult for him to side with Muslims against Hindus in the event of communal problems. Hanwant Singh came close to signing. However, the atmosphere in Jodhpur was in general hostile to accession to Pakistan. Mountbatten also pointed out that the accession of a predominantly Hindu state to Pakistan would violate the principle of the two-nation theory on which Pakistan was based, and was likely to cause communal violence in the State. Hanwant Singh was persuaded by these arguments, and somewhat reluctantly agreed to accede to India.

In the northeast India, the border states of Manipur

Manipur () ( mni, Kangleipak) is a state in Northeast India, with the city of Imphal as its capital. It is bounded by the Indian states of Nagaland to the north, Mizoram to the south and Assam to the west. It also borders two regions of Myanm ...

and Tripura

Tripura (, Bengali: ) is a state in Northeast India. The third-smallest state in the country, it covers ; and the seventh-least populous state with a population of 36.71 lakh ( 3.67 million). It is bordered by Assam and Mizoram to the east a ...

acceded to India on 11 August and 13 August respectively

Junagadh

Although the states were in theory free to choose whether they wished to accede to India or Pakistan, Mountbatten had pointed out that "geographic compulsions" meant that most of them must choose India. In effect, he took the position that only the states that shared a border with Pakistan could choose to accede to it. The Nawab of Junagadh, a princely state located on the south-western end ofGujarat

Gujarat (, ) is a state along the western coast of India. Its coastline of about is the longest in the country, most of which lies on the Kathiawar peninsula. Gujarat is the fifth-largest Indian state by area, covering some ; and the ninth ...

and having no common border with Pakistan, chose to accede to Pakistan ignoring Mountbatten's views, arguing that it could be reached from Pakistan by sea. The rulers of two states that were subject to the suzerainty of Junagadh— Mangrol and Babariawad—reacted to this by declaring their independence from Junagadh and acceding to India. In response, the Nawab of Junagadh militarily occupied the states. The rulers of neighbouring states reacted angrily, sending their troops to the Junagadh frontier and appealed to the Government of India for assistance. A group of Junagadhi people, led by Samaldas Gandhi

Samaldas Gandhi (1897-1953) was a journalist and Indian independence activist who headed the ''Aarzi Hakumat'' or ''Provisional Government'' of the erstwhile princely state of Junagadh. He was a nephew of Mahatma Gandhi.

Early life

Samaldas ...

, formed a government-in-exile, the ''Aarzi Hukumat'' ("provisional government").

India believed that if Junagadh was permitted to go to Pakistan, the communal tension already simmering in Gujarat would worsen, and refused to accept the accession. The government pointed out that the state was 80% Hindu, and called for a referendum to decide the question of accession. Simultaneously, they cut off supplies of fuel and coal to Junagadh, severed air and postal links, sent troops to the frontier, and reoccupied the principalities of Mangrol and Babariawad that had acceded to India. Pakistan agreed to discuss a plebiscite

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a direct vote by the electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a representative. This may result in the adoption of a ...

, subject to the withdrawal of Indian troops, a condition India rejected. On 26 October, the Nawab and his family fled to Pakistan following clashes with Indian troops. On 7 November, Junagadh's court, facing collapse, invited the Government of India to take over the State's administration. The Government of India agreed. A plebiscite was conducted in February 1948, which went almost unanimously in favour of accession to India.

Jammu and Kashmir

At the time of the transfer of power, the state of

At the time of the transfer of power, the state of Jammu and Kashmir Jammu and Kashmir may refer to:

* Kashmir, the northernmost geographical region of the Indian subcontinent

* Jammu and Kashmir (union territory), a region administered by India as a union territory

* Jammu and Kashmir (state), a region administered ...

(widely called "Kashmir") was ruled by Maharaja

Mahārāja (; also spelled Maharajah, Maharaj) is a Sanskrit title for a "great ruler", "great king" or " high king".

A few ruled states informally called empires, including ruler raja Sri Gupta, founder of the ancient Indian Gupta Empire, an ...

Hari Singh, a Hindu, although the state itself had a Muslim majority. Hari Singh was equally hesitant about acceding to either India or Pakistan, as either would have provoked adverse reactions in parts of his kingdom. He signed a Standstill Agreement with Pakistan and proposed one with India as well, but announced that Kashmir intended to remain independent. However, his rule was opposed by Sheikh Abdullah, the popular leader of Kashmir's largest political party, the National Conference, who demanded his abdication.

Pakistan, attempting to force the issue of Kashmir's accession, cut off supplies and transport links. Its transport links with India were tenuous and flooded during the rainy season. Thus Kashmir's only links with the two dominions was by air. Rumours about atrocities against the Muslim population of Poonch Poonch, sometimes also spelt Punchh, may refer to:

* Historical Poonch District, a district in the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir in British India, split in 1947 between:

** Poonch district, India

** Poonch Division, in Azad Kashmir, Pakistan, ...

by the Maharajah's forces circulated in Pakistan. Shortly thereafter, Pathan tribesmen from the North-West Frontier Province

The North-West Frontier Province (NWFP; ps, شمال لویدیځ سرحدي ولایت, ) was a Chief Commissioner's Province of British India, established on 9 November 1901 from the north-western districts of the Punjab Province. Followin ...

of Pakistan crossed the border and entered Kashmir. The invaders made rapid progress towards Srinagar

Srinagar (English: , ) is the largest city and the summer capital of Jammu and Kashmir, India. It lies in the Kashmir Valley on the banks of the Jhelum River, a tributary of the Indus, and Dal and Anchar lakes. The city is known for its natu ...

. The Maharaja of Kashmir wrote to India, asking for military assistance. India required the signing of an Instrument of Accession and setting up an interim government

A provisional government, also called an interim government, an emergency government, or a transitional government, is an emergency governmental authority set up to manage a political transition generally in the cases of a newly formed state or f ...

headed by Sheikh Abdullah in return. The Maharaja complied, but Nehru declared that it would have to be confirmed by a plebiscite, although there was no legal requirement to seek such confirmation.

Indian troops secured Jammu

Jammu is the winter capital of the Indian union territory of Jammu and Kashmir (union territory), Jammu and Kashmir. It is the headquarters and the largest city in Jammu district of the union territory. Lying on the banks of the river Tawi Ri ...

, Srinagar and the valley itself during the First Kashmir War, but the intense fighting flagged with the onset of winter, which made much of the state impassable. Prime Minister Nehru, recognising the degree of international attention brought to bear on the dispute, declared a ceasefire and sought UN arbitration, arguing that India would otherwise have to invade Pakistan itself, in view of its failure to stop the tribal incursions. The plebiscite was never held, and on 26 January 1950, the Constitution of India came into force in Kashmir, but with special provisions made for the state. India did not, however, secure administrative control over all of Kashmir. The northern and western portions of Kashmir came under Pakistan's control in 1947, and are today Pakistan-administered Kashmir

Kashmir () is the northernmost geographical region of the Indian subcontinent. Until the mid-19th century, the term "Kashmir" denoted only the Kashmir Valley between the Great Himalayas and the Pir Panjal Range. Today, the term encompass ...

. In the 1962 Sino-Indian War, China occupied Aksai Chin, the north-eastern region bordering Ladakh

Ladakh () is a region administered by India as a union territory which constitutes a part of the larger Kashmir region and has been the subject of dispute between India, Pakistan, and China since 1947. (subscription required) Quote: "Jammu and ...

, which it continues to control and administer.

Hyderabad

Hyderabad was a landlocked state that stretched over 82,000 square miles (over 212,000 square kilometres) in southeastern India. While 87% of its 17 million people were Hindu, its ruler Nizam Osman Ali Khan was a Muslim, and its politics were dominated by a Muslim elite. The Muslim nobility and the Ittehad-ul-Muslimeen, a powerful pro-Nizam Muslim party, insisted Hyderabad remain independent and stand on an equal footing to India and Pakistan. Accordingly, the Nizam in June 1947 issued a ''

Hyderabad was a landlocked state that stretched over 82,000 square miles (over 212,000 square kilometres) in southeastern India. While 87% of its 17 million people were Hindu, its ruler Nizam Osman Ali Khan was a Muslim, and its politics were dominated by a Muslim elite. The Muslim nobility and the Ittehad-ul-Muslimeen, a powerful pro-Nizam Muslim party, insisted Hyderabad remain independent and stand on an equal footing to India and Pakistan. Accordingly, the Nizam in June 1947 issued a ''firman

A firman ( fa, , translit=farmân; ), at the constitutional level, was a royal mandate or decree issued by a sovereign in an Islamic state. During various periods they were collected and applied as traditional bodies of law. The word firman com ...

'' announcing that on the transfer of power, his state would be resuming independence. The Government of India rejected the firman, terming it a "legalistic claim of doubtful validity". It argued that the strategic location of Hyderabad, which lay astride the main lines of communication between northern and southern India, meant it could easily be used by "foreign interests" to threaten India, and that in consequence, the issue involved national-security concerns. It also pointed out that the state's people, history and location made it unquestionably Indian, and that its own "common interests" therefore mandated its integration into India.

The Nizam was prepared to enter into a limited treaty with India, which gave Hyderabad safeguards not provided for in the standard Instrument of Accession, such as a provision guaranteeing Hyderabad's neutrality in the event of a conflict between India and Pakistan. India rejected this proposal, arguing that other states would demand similar concessions. A temporary Standstill Agreement was signed as a stopgap measure, even though Hyderabad had not yet agreed to accede to India. By December 1947, however, India was accusing Hyderabad of repeatedly violating the Agreement, while the Nizam alleged that India was blockading his state, a charge India denied.

The Nizam was also beset by the Telangana Rebellion

The Telangana Rebellion popularly known as Telangana Sayuda Poratam (Telugu : తెలంగాణ సాయుధ పోరాటం) of 1946–51 was a communist-led insurrection of peasants against the princely state of Hyderabad in the r ...

, led by communists, which started in 1946 as a peasant revolt against feudal elements; and one which the Nizam was not able to subjugate. The situation deteriorated further in 1948. The Razakars Razakar (رضا کار) is etymologically an Arabic word which literally means volunteer. The word is also common in Urdu language as a loanword. On the other hand, in Bangladesh, razakar is a pejorative word meaning a traitor or Judas.

In Pakista ...

("volunteers"), a militia affiliated to the Ittehad-ul-Muslimeen and set up under the influence of Muslim radical Qasim Razvi

Syed Kasim Razvi (also Qasim Razvi; 17 July 1902 – 15 January 1970) was a politician in the princely state of Hyderabad. He was the president of the Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen party from December 1946 until the state's accession to India in ...

, assumed the role of supporting the Muslim ruling class against upsurges by the Hindu populace, and began intensifying its activities and was accused of attempting to intimidate villages. The Hyderabad State Congress Party, affiliated to the Indian National Congress, launched a political agitation. Matters were made worse by communist groups, which had originally supported the Congress but now switched sides and began attacking Congress groups. Attempts by Mountbatten to find a negotiated solution failed and, in August, the Nizam, claiming that he feared an imminent invasion, attempted to approach the UN Security Council

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN) and is charged with ensuring international peace and security, recommending the admission of new UN members to the General Assembly, and ...

and the International Court of Justice

The International Court of Justice (ICJ; french: Cour internationale de justice, links=no; ), sometimes known as the World Court, is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN). It settles disputes between states in accordanc ...

. Patel now insisted that if Hyderabad was allowed to continue its independence, the prestige of the Government would be tarnished and then neither Hindus nor Muslims would feel secure in its realm.

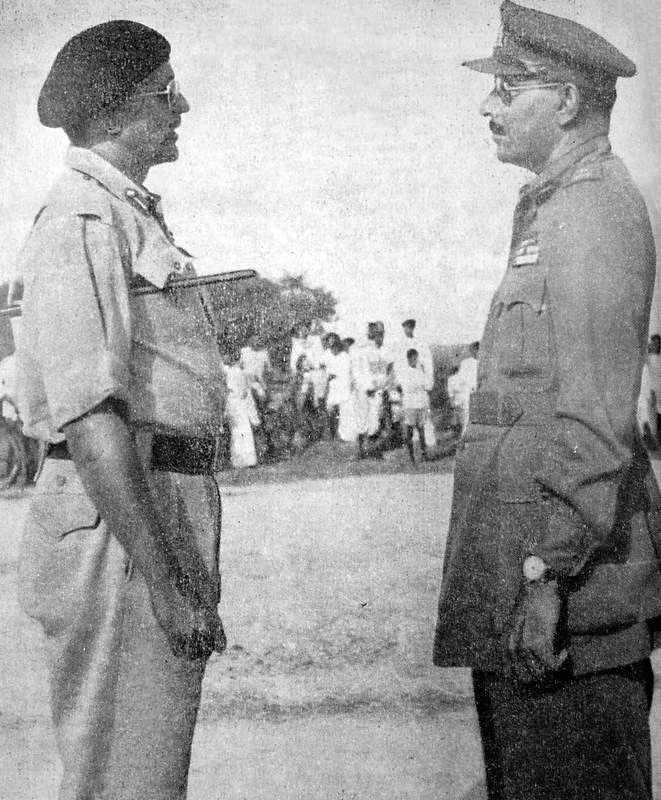

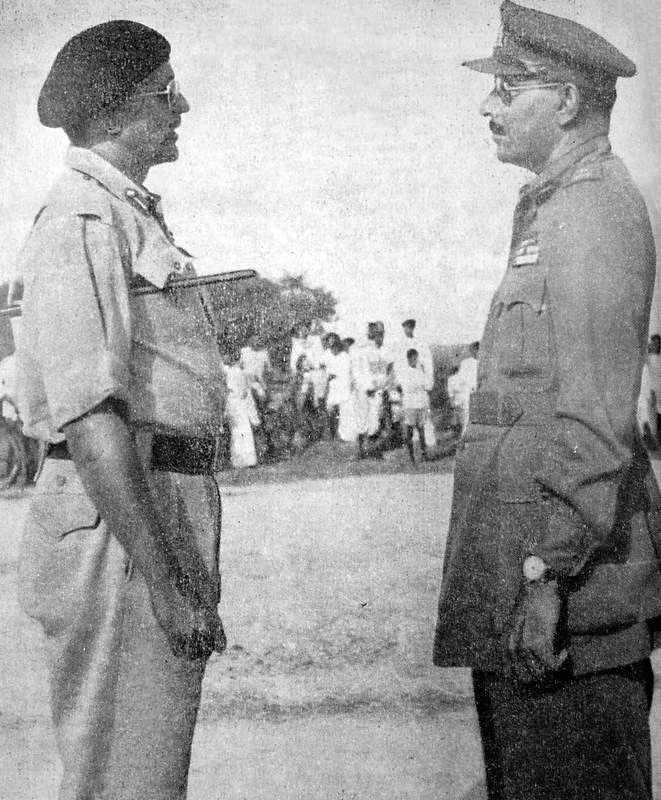

On 13 September 1948, the Indian Army

The Indian Army is the land-based branch and the largest component of the Indian Armed Forces. The President of India is the Supreme Commander of the Indian Army, and its professional head is the Chief of Army Staff (COAS), who is a four- ...

was sent into Hyderabad under Operation Polo on the grounds that the law and order situation there threatened the peace of South India

South India, also known as Dakshina Bharata or Peninsular India, consists of the peninsular southern part of India. It encompasses the Indian states of Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala, Tamil Nadu, and Telangana, as well as the union territo ...

. The troops met little resistance by the Razakars and between 13 and 18 September took complete control of the state. The operation led to massive communal violence with estimates of deaths ranging from the official one of 27,000–40,000 to scholarly ones of 200,000 or more. The Nizam was retained as the head of state

A head of state (or chief of state) is the public persona who officially embodies a state Foakes, pp. 110–11 " he head of statebeing an embodiment of the State itself or representatitve of its international persona." in its unity and l ...

in the same manner as the other princes who acceded to India. He thereupon disavowed the complaints that had been made to the UN and, despite vehement protests from Pakistan and strong criticism from other countries, the Security Council did not deal further with the question, and Hyderabad was absorbed into India.

Completing integration

The Instruments of Accession were limited, transferring control of only three matters to India, and would by themselves have produced a rather loose federation, with significant differences in administration and governance across the various states. Full political integration, in contrast, would require a process whereby the political actors in the various states were "persuaded to shift their loyalties, expectations, and political activities towards a new center", namely, the

The Instruments of Accession were limited, transferring control of only three matters to India, and would by themselves have produced a rather loose federation, with significant differences in administration and governance across the various states. Full political integration, in contrast, would require a process whereby the political actors in the various states were "persuaded to shift their loyalties, expectations, and political activities towards a new center", namely, the Republic of India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

. This was not an easy task. While some princely states such as Mysore

Mysore (), officially Mysuru (), is a city in the southern part of the state of Karnataka, India. Mysore city is geographically located between 12° 18′ 26″ north latitude and 76° 38′ 59″ east longitude. It is located at an altitude of ...

had legislative systems of governance that were based on a broad franchise and not significantly different from those of British India, in others, political decision-making took place in small, limited aristocratic circles and governance was, as a result, at best paternalistic and at worst the result of courtly intrigue. Having secured the accession of the princely states, the Government of India between 1948 and 1950 turned to the task of welding the states and the former British provinces into one polity under a single republican constitution.

Fast-track integration

The first step in this process, carried out between 1947 and 1949, was to merge the smaller states that were not seen by the Government of India to be viable administrative units either into neighbouring provinces, or with other princely states to create a "princely union". This policy was contentious, since it involved the dissolution of the very states whose existence India had only recently guaranteed in the Instruments of Accession. Patel and Menon emphasised that without integration, the economies of states would collapse, and anarchy would arise if the princes were unable to provide democracy and govern properly. They pointed out that many of the smaller states were very small and lacked resources to sustain their economies and support their growing populations. Many also imposed tax rules and other restrictions that impeded free trade, and which had to be dismantled in a united India. Given that merger involved the breach of guarantees personally given by Mountbatten, initially Patel and Nehru intended to wait until after his term asGovernor-General

Governor-general (plural ''governors-general''), or governor general (plural ''governors general''), is the title of an office-holder. In the context of governors-general and former British colonies, governors-general are appointed as viceroy t ...

ended. An adivasi

The Adivasi refers to inhabitants of Indian subcontinent, generally tribal people. The term is a Sanskrit word coined in the 1930s by political activists to give the tribal people an indigenous identity by claiming an indigenous origin. The term ...

uprising in Orissa

Odisha (English: , ), formerly Orissa ( the official name until 2011), is an Indian state located in Eastern India. It is the 8th largest state by area, and the 11th largest by population. The state has the third largest population of Sch ...

in late 1947, however, forced their hand. In December 1947, princes from the Eastern India Agency and Chhattisgarh Agency were summoned to an all-night meeting with Menon, where they were persuaded to sign Merger Agreements integrating their states into Orissa, the Central Provinces

The Central Provinces was a province of British India. It comprised British conquests from the Mughals and Marathas in central India, and covered parts of present-day Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh and Maharashtra states. Its capital was Nagpur. ...

and Bihar

Bihar (; ) is a state in eastern India. It is the 2nd largest state by population in 2019, 12th largest by area of , and 14th largest by GDP in 2021. Bihar borders Uttar Pradesh to its west, Nepal to the north, the northern part of West Be ...

with effect from 1 January 1948. Later that year, 66 states in Gujarat and the Deccan were merged into Bombay

Mumbai (, ; also known as Bombay — the official name until 1995) is the capital city of the Indian state of Maharashtra and the ''de facto'' financial centre of India. According to the United Nations, as of 2018, Mumbai is the second- ...

, including the large states of Kolhapur

Kolhapur () is a city on the banks of the Panchganga River in the southern part of the Indian state of Maharashtra. It is the administrative headquarter of the Kolhapur district. In, around 2 C.E. Kolapur's name was 'Kuntal'.

Kolhapur is kn ...

and Baroda

Vadodara (), also known as Baroda, is the second largest city in the Indian state of Gujarat. It serves as the administrative headquarters of the Vadodara district and is situated on the banks of the Vishwamitri River, from the state capital ...

. Other small states were merged into Madras

Chennai (, ), formerly known as Madras ( the official name until 1996), is the capital city of Tamil Nadu, the southernmost Indian state. The largest city of the state in area and population, Chennai is located on the Coromandel Coast of th ...

, East Punjab

East Punjab (known simply as Punjab from 1950) was a province and later a state of India from 1947 until 1966, consisting of the parts of the Punjab Province of British India that went to India following the partition of the province between ...

, West Bengal, the United Provinces and Assam

Assam (; ) is a state in northeastern India, south of the eastern Himalayas along the Brahmaputra and Barak River valleys. Assam covers an area of . The state is bordered by Bhutan and Arunachal Pradesh to the north; Nagaland and Manipur ...

. Not all states that signed Merger Agreements were integrated into provinces, however. Thirty states of the former Punjab Hill States Agency

The Punjab States Agency was an agency of the Indian Empire. The agency was created in 1921, on the model of the Central India Agency and Rajputana Agency, and dealt with forty princely states in northwest India formerly dealt with by the Prov ...

which lay near the international border and had signed Merger Agreements were integrated into Himachal Pradesh

Himachal Pradesh (; ; "Snow-laden Mountain Province") is a state in the northern part of India. Situated in the Western Himalayas, it is one of the thirteen mountain states and is characterized by an extreme landscape featuring several peaks ...

, a distinct entity which was administered directly by the centre as a Chief Commissioner's Province, for reasons of security.

The Merger Agreements required rulers to cede "full and exclusive jurisdiction and powers for and in relation to governance" of their state to the Dominion of India

The Dominion of India, officially the Union of India,* Quote: “The first collective use (of the word "dominion") occurred at the Colonial Conference (April to May 1907) when the title was conferred upon Canada and Australia. New Zealand and N ...

. In return for their agreement to entirely cede their states, it gave princes a large number of guarantees. Princes would receive an annual payment from the Indian government in the form of a privy purse as compensation for the surrender of their powers and the dissolution of their states. While state property would be taken over, their private property

Private property is a legal designation for the ownership of property by non-governmental legal entities. Private property is distinguishable from public property and personal property, which is owned by a state entity, and from collective or ...

would be protected, as would all personal privileges, dignities and titles. Succession was also guaranteed according to custom. In addition, the provincial administration was obliged to take on the staff of the princely states with guarantees of equal pay and treatment.

A second kind of 'merger' agreements were demanded from larger states along sensitive border areas: Kutch in western India, and Tripura

Tripura (, Bengali: ) is a state in Northeast India. The third-smallest state in the country, it covers ; and the seventh-least populous state with a population of 36.71 lakh ( 3.67 million). It is bordered by Assam and Mizoram to the east a ...

and Manipur

Manipur () ( mni, Kangleipak) is a state in Northeast India, with the city of Imphal as its capital. It is bounded by the Indian states of Nagaland to the north, Mizoram to the south and Assam to the west. It also borders two regions of Myanm ...

in Northeast India

, native_name_lang = mni

, settlement_type =

, image_skyline =

, image_alt =

, image_caption =

, motto =

, image_map = Northeast india.png

, ...

. They were not merged into other states but retained as Chief Commissioners' Provinces under the central government control. Bhopal

Bhopal (; ) is the capital city of the Indian state of Madhya Pradesh and the administrative headquarters of both Bhopal district and Bhopal division. It is known as the ''City of Lakes'' due to its various natural and artificial lakes. It i ...

, whose ruler was proud of the efficiency of his administration and feared that it would lose its identity if merged with the Maratha

The Marathi people (Marathi: मराठी लोक) or Marathis are an Indo-Aryan ethnolinguistic group who are indigenous to Maharashtra in western India. They natively speak Marathi, an Indo-Aryan language. Maharashtra was formed as a M ...

states that were its neighbours, also became a directly administered Chief Commissioner's Province, as did Bilaspur, much of which was likely to be flooded on completion of the Bhakra dam.

Four-step integration

Merger

The bulk of the larger states, and some groups of small states, were integrated through a different, four-step process. The first step in this process was to convince adjacent large states and a large number of adjacent small states to combine to form a "princely union" through the execution by their rulers of Covenants of Merger. Under the Covenants of Merger, all rulers lost their ruling powers, save one who became the Rajpramukh of the new union. The other rulers were associated with two bodies—the council of rulers, whose members were the rulers ofsalute state

A salute state was a princely state under the British Raj that had been granted a gun salute by the British Crown (as paramount ruler); i.e., the protocolary privilege for its ruler to be greeted—originally by Royal Navy ships, later also ...

s, and a presidium, one or more of whose members were elected by the rulers of non-salute states, with the rest elected by the council. The Rajpramukh and his deputy ''Uprajpramukh'' were chosen by the council from among the members of the presidium. The Covenants made provision for the creation of a constituent assembly for the new union which would be charged with framing its constitution. In return for agreeing to the extinction of their states as discrete entities, the rulers were given a privy purse and guarantees similar to those provided under the Merger Agreements.

Through this process, Patel obtained the unification of 222 states in the Kathiawar

Kathiawar () is a peninsula, near the far north of India's west coast, of about bordering the Arabian Sea. It is bounded by the Gulf of Kutch in the northwest and by the Gulf of Khambhat (Gulf of Cambay) in the east. In the northeast, it is ...

peninsula of his native Gujarat into the princely union of Saurashtra in January 1948, with six more states joining the union the following year. Madhya Bharat emerged on 28 May 1948 from a union of Gwalior

Gwalior() is a major city in the central Indian state of Madhya Pradesh; it lies in northern part of Madhya Pradesh and is one of the Counter-magnet cities. Located south of Delhi, the capital city of India, from Agra and from Bhopal, the s ...

, Indore

Indore () is the largest and most populous Cities in India, city in the Indian state of Madhya Pradesh. It serves as the headquarters of both Indore District and Indore Division. It is also considered as an education hub of the state and is t ...

and eighteen smaller states. In Punjab, the Patiala and East Punjab States Union

Patiala () is a city in southeastern Punjab, northwestern India. It is the fourth largest city in the state and is the administrative capital of Patiala district. Patiala is located around the ''Qila Mubarak'' (the 'Fortunate Castle') constructe ...

was formed on 15 July 1948 from Patiala

Patiala () is a city in southeastern Punjab, India, Punjab, northwestern India. It is the fourth largest city in the state and is the administrative capital of Patiala district. Patiala is located around the ''Qila Mubarak, Patiala, Qila Mubarak ...

, Kapurthala, Jind, Nabha, Faridkot, Malerkotla, Nalargarh, and Kalsia

Kalsia was a princely state in Punjab, British India, one of the former Cis-Sutlej states. It was founded by Raja Gurbaksh Singh Sandhu in 1760. After India's independence, it was included in PEPSU and later in the Indian East Punjab after th ...

. The United State of Rajasthan

Rajasthan (; lit. 'Land of Kings') is a state in northern India. It covers or 10.4 per cent of India's total geographical area. It is the largest Indian state by area and the seventh largest by population. It is on India's northwestern si ...