Pacific Squadron on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Pacific Squadron was part of the

Arriving off Sumatra exactly a year after the ''Friendship'' incident, Commodore Downes with just under 300 bluejackets and marines aboard the frigate, attacked Quallah Battoo, the main village of the hostile Malays. The men went ashore in launches during which a small naval engagement was fought. A few of the boats were armed with a light cannon and were ordered to sink three small pirate craft in the port. The launches achieved their goal and then proceeded in assisting USS ''Potomac'' in shelling five enemy

Arriving off Sumatra exactly a year after the ''Friendship'' incident, Commodore Downes with just under 300 bluejackets and marines aboard the frigate, attacked Quallah Battoo, the main village of the hostile Malays. The men went ashore in launches during which a small naval engagement was fought. A few of the boats were armed with a light cannon and were ordered to sink three small pirate craft in the port. The launches achieved their goal and then proceeded in assisting USS ''Potomac'' in shelling five enemy

The Pacific Squadron was instrumental in the capture of

The Pacific Squadron was instrumental in the capture of  In July 1846,

In July 1846,

After Alta California was secured most of the squadron proceeded down the Pacific coast capturing all major Baja California Peninsula cities and capturing or destroying nearly all Mexican vessels in the Gulf of California. Other mainland ports, not on the peninsula, were taken as well. The objective of the campaign was to take Mazatlan, a major supply base for Mexican forces. ''Cyane'' was given credit for eighteen captures and numerous destroyed ships. Entering the Gulf of California, ''Independence'', ''Congress'' and ''Cyane'' seized La Paz on the Baja California Peninsula, and captured and or burned the small Mexican fleet at Guaymas across the Gulf on the mainland. Within a month, they cleared the Gulf of hostile ships, destroying or capturing thirty vessels. Later on their sailors and marines captured the town of Mazatlan, Mexico, on 11 November 1847. A Mexican campaign to retake the various captured ports resulted in several small battles and at least two sieges occurred in which the Pacific Squadron ships provided support. ''Cyane'' returned to Norfolk on 9 October 1848 to receive the congratulations of the

After Alta California was secured most of the squadron proceeded down the Pacific coast capturing all major Baja California Peninsula cities and capturing or destroying nearly all Mexican vessels in the Gulf of California. Other mainland ports, not on the peninsula, were taken as well. The objective of the campaign was to take Mazatlan, a major supply base for Mexican forces. ''Cyane'' was given credit for eighteen captures and numerous destroyed ships. Entering the Gulf of California, ''Independence'', ''Congress'' and ''Cyane'' seized La Paz on the Baja California Peninsula, and captured and or burned the small Mexican fleet at Guaymas across the Gulf on the mainland. Within a month, they cleared the Gulf of hostile ships, destroying or capturing thirty vessels. Later on their sailors and marines captured the town of Mazatlan, Mexico, on 11 November 1847. A Mexican campaign to retake the various captured ports resulted in several small battles and at least two sieges occurred in which the Pacific Squadron ships provided support. ''Cyane'' returned to Norfolk on 9 October 1848 to receive the congratulations of the

In 1899 another civil war broke out in

In 1899 another civil war broke out in

In 1903, the Pacific Squadron consisted of the

In 1903, the Pacific Squadron consisted of the

Ships of the California Naval Militia, USS Camanche

/ref> * , lighthouse tender steamer

''Thence Round Cape Horn: The Story of United States Naval Forces on Pacific Station, 1818-1923''

book by Robert Erwin Johnson (1963)

{{US Squadrons First hand account of captain RICHARD GASSAWAY WATKINS * https://sites.rootsweb.com/~mdannear/firstfam/watkins.htm Ship squadrons of the United States Navy Maritime history of the United States Military history of the Pacific Ocean 1821 establishments in the United States 1907 disestablishments in the United States Hawaiian Kingdom–United States relations Pacific Coast Theater of the American Civil War

United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

squadron stationed in the Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the contine ...

in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Initially with no United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., federal district, five ma ...

ports in the Pacific, they operated out of storeships which provided naval supplies and purchased food and obtained water from local ports of call in the Hawaiian Islands

The Hawaiian Islands ( haw, Nā Mokupuni o Hawai‘i) are an archipelago of eight major islands, several atolls, and numerous smaller islets in the North Pacific Ocean, extending some from the island of Hawaii in the south to northernmost ...

and towns on the Pacific Coast

Pacific coast may be used to reference any coastline that borders the Pacific Ocean.

Geography Americas

Countries on the western side of the Americas have a Pacific coast as their western or southwestern border, except for Panama, where the P ...

. Throughout the history of the Pacific Squadron, American ships fought against several enemies. Over one-half of the United States Navy would be sent to join the Pacific Squadron during the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Second Federal Republic of Mexico, Mexico f ...

. During the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by state ...

, the squadron was reduced in size when its vessels were reassigned to Atlantic duty. When the Civil War was over, the squadron was reinforced again until being disbanded just after the turn of the 20th century.

History

Formation

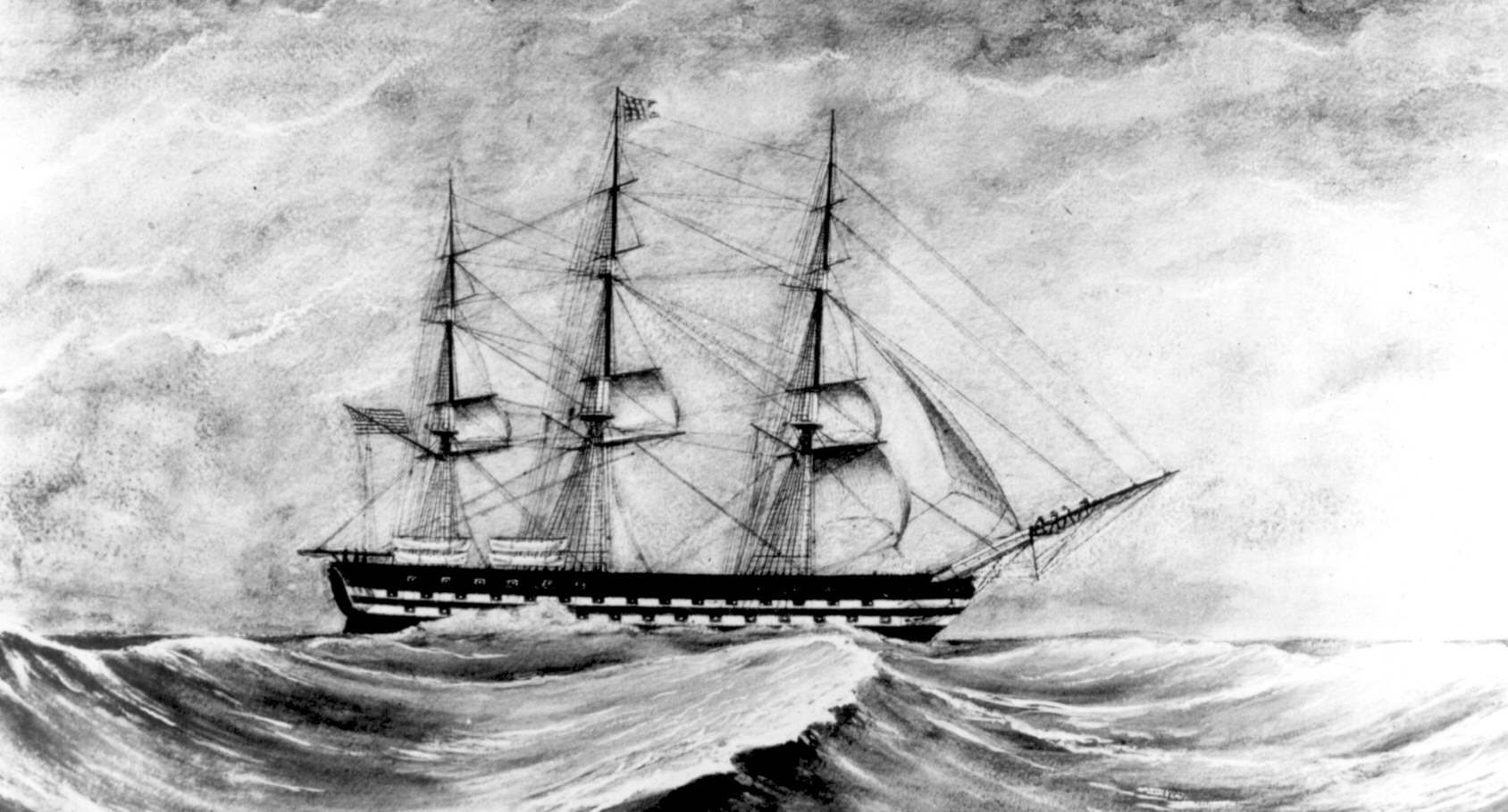

The "United States Naval Forces on Pacific Station" was established in 1818, with the USS ''Macedonian'' under John Downes setting sail to protect American interests in the Pacific Ocean. The ''Macedonian'' served in Chile until March 1821, when it was relieved by the USS ''Constellation'' underCharles G. Ridgely

Charles Goodwin Ridgely (July 2, 1784 – February 8, 1848) was an officer in the United States Navy. He fought under Edward Preble in the First Barbary War (1804–1805), before serving as the commander of the Pacific Station (1820–1822) ...

. These two single-frigate instances of the Pacific Station supported the Liberating Expedition of Peru in the Peruvian War of Independence.

Most historians consider the Pacific Squadron to have been officially established in 1821 with the first multiple-ship force in the Pacific Station. Charles Stewart set sail with the USS ''Franklin'' and USS ''Dolphin'' in September 1821 and arrived in April 1822 to relieve Ridgely.

This small force confined its activities initially to the Pacific waters off South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere at the northern tip of the continent. It can also be described as the souther ...

, North America and Hawaii

Hawaii ( ; haw, Hawaii or ) is a state in the Western United States, located in the Pacific Ocean about from the U.S. mainland. It is the only U.S. state outside North America, the only state that is an archipelago, and the only ...

protecting United States commercial shipping interests. It expanded its scope of operations to include the Western Pacific in 1835, when the East India Squadron joined the force. The squadron was reinforced when war with Mexico

Mexico ( Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a country in the southern portion of North America. It is bordered to the north by the United States; to the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; to the southeast by Guate ...

began to seem a possibility. Sailing from the east coast to the west coast around Cape Horn

Cape Horn ( es, Cabo de Hornos, ) is the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago of southern Chile, and is located on the small Hornos Island. Although not the most southerly point of South America (which are the Diego Ramí ...

was a to journey that typically took from 130 to 210 days.

Sumatran Expeditions

The Pacific Squadron's First Sumatran Expedition conflict arose in February 1831. Off the coast of Sumatra on February 7, the American merchant vessel ''Friendship'' out ofSalem

Salem may refer to: Places

Canada

Ontario

* Bruce County

** Salem, Arran–Elderslie, Ontario, in the municipality of Arran–Elderslie

** Salem, South Bruce, Ontario, in the municipality of South Bruce

* Salem, Dufferin County, Ontario, part ...

was attacked by Malay natives described as "warrior pirates". The Americans were hoping to buy pepper

Pepper or peppers may refer to:

Food and spice

* Piperaceae or the pepper family, a large family of flowering plant

** Black pepper

* ''Capsicum'' or pepper, a genus of flowering plants in the nightshade family Solanaceae

** Bell pepper

** Chili ...

from the natives but were instead attacked by three small vessels. Three men aboard ''Friendship'' were killed, one of whom was the First Mate; the remaining crew members abandoned their vessel and it was captured. The passing Dutch schooner

A schooner () is a type of sailing vessel defined by its rig: fore-and-aft rigged on all of two or more masts and, in the case of a two-masted schooner, the foremast generally being shorter than the mainmast. A common variant, the topsail schoo ...

''Dolfijn'' made a failed attempt to rescue the ship—the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1824

The Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1824, also known as the Treaty of London, was a treaty signed between the United Kingdom and the Netherlands in London on 17 March 1824. The treaty was to resolve disputes arising from the execution of the Anglo ...

obligated the Dutch to ensure the safety of shipping and overland trade in and around Aceh

Aceh ( ), officially the Aceh Province ( ace, Nanggroë Acèh; id, Provinsi Aceh) is the westernmost province of Indonesia. It is located on the northernmost of Sumatra island, with Banda Aceh being its capital and largest city. Granted a s ...

, and precipitated the Dutch expedition on the west coast of Sumatra later that year. The surviving sailors escaped to a friendly port nearby with the help of a friendly Malay tribal chief

A tribal chief or chieftain is the leader of a tribal society or chiefdom.

Tribe

The concept of tribe is a broadly applied concept, based on tribal concepts of societies of western Afroeurasia.

Tribal societies are sometimes categorized ...

, and then obtained the assistance of other American merchantmen to retake the plundered ship. Captain Endecott returned the ship to Salem July 16, 1831. President Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame a ...

received word of the 'massacre' and ordered Commodore John Downes in to punish the natives for their acts of piracy

Piracy is an act of robbery or criminal violence by ship or boat-borne attackers upon another ship or a coastal area, typically with the goal of stealing cargo and other valuable goods. Those who conduct acts of piracy are called pirates, v ...

.

Arriving off Sumatra exactly a year after the ''Friendship'' incident, Commodore Downes with just under 300 bluejackets and marines aboard the frigate, attacked Quallah Battoo, the main village of the hostile Malays. The men went ashore in launches during which a small naval engagement was fought. A few of the boats were armed with a light cannon and were ordered to sink three small pirate craft in the port. The launches achieved their goal and then proceeded in assisting USS ''Potomac'' in shelling five enemy

Arriving off Sumatra exactly a year after the ''Friendship'' incident, Commodore Downes with just under 300 bluejackets and marines aboard the frigate, attacked Quallah Battoo, the main village of the hostile Malays. The men went ashore in launches during which a small naval engagement was fought. A few of the boats were armed with a light cannon and were ordered to sink three small pirate craft in the port. The launches achieved their goal and then proceeded in assisting USS ''Potomac'' in shelling five enemy citadel

A citadel is the core fortified area of a town or city. It may be a castle, fortress, or fortified center. The term is a diminutive of "city", meaning "little city", because it is a smaller part of the city of which it is the defensive core.

In ...

s. The five forts were attacked by land as well and all were eventually suppressed. Hundreds of matchlock

A matchlock or firelock is a historical type of firearm wherein the gunpowder is ignited by a burning piece of rope that is touched to the gunpowder by a mechanism that the musketeer activates by pulling a lever or trigger with his finger. Befo ...

armed natives were killed with a loss of only two Americans. After the battle, Downes warned that if any more American merchant ships were attacked, another expedition would be launched in reprisal.

The mission was technically a success for six years until 1838 when the Malays attacked and plundered a second American merchantman. In response, the Second Sumatran Expedition was launched by ships of the East India Squadron, which had just joined the United States Exploring Expedition for circumnavigation

Circumnavigation is the complete navigation around an entire island, continent, or astronomical body (e.g. a planet or moon). This article focuses on the circumnavigation of Earth.

The first recorded circumnavigation of the Earth was the Magel ...

of the globe, but were able to bombard Quallah Battoo and engage in the battle of Muckie without making a detour.

Capture of Monterey

In 1842 the Pacific Squadron commander Commodore Thomas ap Catesby Jones received false information that war had begun between the United States and Mexico and that the British ship HMS ''Dublin'' was cruising offCalifornia

California is a state in the Western United States, located along the Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the most populous U.S. state and the 3rd largest by area. It is also the ...

to take control of the Mexican state. In response Commodore Jones in his frigate USS ''United States'' and with the sloops

A sloop is a sailboat with a single mast typically having only one headsail in front of the mast and one mainsail aft of (behind) the mast. Such an arrangement is called a fore-and-aft rig, and can be rigged as a Bermuda rig with triangular ...

USS ''Dale'' and USS ''Cyane'' sailed for California's capital, Monterey

Monterey (; es, Monterrey; Ohlone: ) is a city located in Monterey County on the southern edge of Monterey Bay on the U.S. state of California's Central Coast. Founded on June 3, 1770, it functioned as the capital of Alta California under bo ...

. They arrived on 19 October 1842 and took control of the city without bloodshed before returning it to the Mexicans on 21 October when Jones discovered that war had not actually been declared.

Mexican–American War

California Campaign

The Pacific Squadron was instrumental in the capture of

The Pacific Squadron was instrumental in the capture of Alta California

Alta California ('Upper California'), also known as ('New California') among other names, was a province of New Spain, formally established in 1804. Along with the Baja California peninsula, it had previously comprised the province of , but ...

in the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Second Federal Republic of Mexico, Mexico f ...

of 1846 to 1848. In the conflict's early months after war was declared on 24 April 1846, the American navy with its force of 350-400 marines and bluejacket sailors on board several ships near California were essentially the only significant United States military force on the Pacific coast. Marines were stationed aboard each warship to assist in close-quarters, ship to ship combat and to serve as both ship-board guards and the primary component of boarding

Boarding may refer to:

*Boarding, used in the sense of "room and board", i.e. lodging and meals as in a:

** Boarding house

**Boarding school

*Boarding (horses) (also known as a livery yard, livery stable, or boarding stable), is a stable where ho ...

or landing parties; they could also be detached for extended service on land. In actual practice, some sailors on each ship were detached from each vessel to supplement the marine force, although rarely more than would compromise a ship's ability to remain functional. The Pacific Squadron had orders, in the event of war with Mexico, to seize the ports in Mexican California and elsewhere along the Pacific Coast

Pacific coast may be used to reference any coastline that borders the Pacific Ocean.

Geography Americas

Countries on the western side of the Americas have a Pacific coast as their western or southwestern border, except for Panama, where the P ...

.

The only other United States force in California was a sixty-two man "mapping" expedition which had entered California in late 1845 under the command of U.S. Army Brevet Captain John C. Frémont. They had been dispatched under the auspices of the Corps of Topographical Engineers. Frémont, the son-in-law of expansionist U.S. Senator Thomas Hart Benton, had acted provocatively with California's Mexican government, and sustained a shadowy relationship with the American emigrants who began the Bear Flag Revolt

The California Republic ( es, La República de California), or Bear Flag Republic, was an List of historical unrecognized states#Americas, unrecognized breakaway state from Second Federal Republic of Mexico, Mexico, that for 25 days in 1846 ...

on June 10, 1846 by stealing government horses they feared would be used against them. On 5 July Frémont proposed to the American insurgents that they unite with his party and become a single military group under his command. A compact was drawn up which all volunteers of the California Battalion signed or made their mark.

Under John D. Sloat, Commodore of the Pacific Squadron, with ''Cyane'' and captured the Alta California capital city of Monterey, California

Monterey (; es, Monterrey; Ohlone: ) is a city located in Monterey County on the southern edge of Monterey Bay on the U.S. state of California's Central Coast. Founded on June 3, 1770, it functioned as the capital of Alta California under bo ...

on 7 July 1846. Two days later on 9 July, , under Captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

John S. Montgomery, landed seventy marines and bluejacket sailors at Clark's Point in San Francisco Bay

San Francisco Bay is a large tidal estuary in the United States, U.S. state of California, and gives its name to the San Francisco Bay Area. It is dominated by the big cities of San Francisco, San Jose, California, San Jose, and Oakland, Ca ...

and captured Yerba Buena

Yerba buena or hierba buena is the Spanish name for a number of aromatic plants, most of which belong to the mint family. ''Yerba buena'' translates as "good herb". The specific plant species regarded as ''yerba buena'' varies from region to reg ...

, which is today's San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish language, Spanish for "Francis of Assisi, Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the List of Ca ...

, without firing a shot. On 11 July the British Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by Kingdom of England, English and Kingdom of Scotland, Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were foug ...

sloop entered San Francisco Bay, causing Montgomery to alert his defenses. The large British ship, the 2,600-ton man-of-war , flagship of Pacific Station Commander-in-Chief Sir George S. Seymour, also showed up about this time outside Monterey Harbor. Both British ships observed, but did not enter the conflict.

Commodore Robert F. Stockton took over as the senior United States military commander in California in late July 1846; his flagship was the frigate . Stockton accepted the California Battalion under Fremont's command to help secure Southern California. The battalion left for San Diego on ''Cyane'' on 26 July. Most towns surrendered without a shot being fired. Fremont's California Battalion members were sworn in and the volunteers paid the regular United States Army salary of $25.00 a month for privates with higher pay for officers. The California Battalion varied in size with time from about 160 initially to over 450 by January 1847. Pacific Squadron war ships and storeships served as floating store houses keeping Fremont's volunteer force in the California Battalion supplied with black powder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, carbon (in the form of charcoal) and potassium nitrate ( saltpeter) ...

, lead shot and supplies as well as transporting them to different California ports. ''Cyane'' transported Fremont and about 160 of his men to the small port of San Diego

San Diego ( , ; ) is a city on the Pacific Ocean coast of Southern California located immediately adjacent to the Mexico–United States border. With a 2020 population of 1,386,932, it is the eighth most populous city in the United States ...

which was captured on 29 July 1846 without a shot being fired.

Leaving about forty men to garrison San Diego, Fremont continued on to the Pueblo de Los Angeles where on 13 August, with the United States Navy band playing and colors flying, the combined forces of Stockton and Frémont entered the town without a man killed or gun fired. United States Marine Major Archibald Gillespie, Fremont's second in command, was appointed military commander of Los Angeles

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the largest city in the state of California and the second most populous city in the United States after New York City, as well as one of the wor ...

, the largest settlement in Alta California with about 1,500 residents. Gillespie had an inadequate force of from thirty to fifty troops stationed there to keep order and garrison the city. ''Congress'' is credited with capturing the Los Angeles harbor and port at San Pedro Bay on 6 August 1846. ''Congress'' later helped capture Mazatlan, Mexico on 11 November 1847.

The revolt of about 100 Californios in Los Angeles forced Gillespie and his troops departure on about 24 September 1847. Commodore Stockton used about 360 marines and bluejacket sailors with four field pieces from ''Congress'' in a joint operation with the approximate seventy cavalry troops supplied by United States Army Brigadier General

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed t ...

Stephen W. Kearny, who had arrived from New Mexico

)

, population_demonym = New Mexican ( es, Neomexicano, Neomejicano, Nuevo Mexicano)

, seat = Santa Fe, New Mexico, Santa Fe

, LargestCity = Albuquerque, New Mexico, Albuquerque

, LargestMetro = Albuquerque metropolitan area, Tiguex

, Offi ...

, and part of Fremont's California Battalion of about 450 men to retake Los Angeles on 10 January 1847. The result of this Battle of Providencia was the Californios signing the Treaty of Cahuenga on 13 January 1847 — terminating the warfare and disbanding the Californio troops in Alta California. On January 16, 1847, Commodore Stockton appointed Frémont military governor of U.S. territorial California - a move later contested by General Kearny.

The retired ship of the line

A ship of the line was a type of naval warship constructed during the Age of Sail from the 17th century to the mid-19th century. The ship of the line was designed for the naval tactic known as the line of battle, which depended on the two colu ...

was brought back into service, cut down and recommissioned as a razee frigate in 1846. The newly reconfigured ship removed the old top deck and reduced the gun count from ninety to fifty-four making her less well gunned but much easier to sail. The rebuilt ''Independence'', now classified as a heavy frigate, launched on 4 August 1846 when the nation was already at war with Mexico and departed Boston 29 August 1846 for California. She entered Monterey Bay

Monterey Bay is a bay of the Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica ...

on 22 January 1847 after a fast 146-day trip around Cape Horn and became the flagship of Commodore William Shubrick, now commanding the Pacific Squadron.

In July 1846,

In July 1846, Colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge ...

Jonathan D. Stevenson

Jonathan Drake Stevenson (1800–1894) was born in New York; won a seat in the New York State Assembly; was the commanding officer of the First Regiment of New York Volunteers during the Mexican–American War in California; entered California mi ...

of New York was asked to raise a volunteer regiment of ten companies of seventy-seven men each to go to California with the understanding that they would be muster out and stay in California. They were designated the 1st Regiment of New York Volunteers 1st Regiment of New York Volunteers, for service in California and during the war with Mexico, was raised in 1846 during the Mexican–American War by Jonathan D. Stevenson. Accepted by the United States Army on August 1846, the 1st Regiment of New ...

and fought in the California Campaign and the Pacific Coast Campaign. In August and September the regiment trained and prepared for the trip to California. Three private merchant ships, ''Thomas H Perkins'', ''Loo Choo'', and ''Susan Drew'', were chartered, and the sloop was assigned convoy detail. On 26 September the four ships left New York for California. Fifty men who had been left behind for various reasons sailed on 13 November 1846 on the small storeship . ''Susan Drew'' and ''Loo Choo'' reached Valparaiso, Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the eas ...

by 20 January 1847 and after getting fresh supplies, water and wood were on their way again by 23 January. ''Thomas H Perkins'' did not stop until San Francisco, reaching port on 6 March 1847. ''Susan Drew'' arrived on 20 March 1847 and ''Loo Choo'' arrived on 26 March 1847, 183 days after leaving New York. ''Brutus'' finally arrived on 17 April 1847.

After desertions and deaths in transit the four ships brought 648 men to California. The companies were then deployed throughout Upper-''Alta'' and Lower-''Baja'' California from San Francisco to La Paz, Mexico. The ship ''Isabella '' sailed from Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

on 16 August 1847, with a detachment of one hundred soldiers, and arrived in California on 18 February 1847, the following year, at about the same time that the ship ''Sweden'' arrived with another detachment of soldiers. These soldiers were added to the existing companies of Jonathan D. Stevenson's 1st Regiment of New York Volunteers. These troops essentially took over all of the Pacific Squadron's on-shore military and garrison duties and the California Battalion and Mormon Battalion

The Mormon Battalion was the only religious unit in United States military history in federal service, recruited solely from one religious body and having a religious title as the unit designation. The volunteers served from July 1846 to July ...

's garrison duties as well as some Baja California

Baja California (; 'Lower California'), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Baja California ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Baja California), is a state in Mexico. It is the northernmost and westernmost of the 32 federal entities of Mex ...

duties.

Pacific Coast Campaign

After Alta California was secured most of the squadron proceeded down the Pacific coast capturing all major Baja California Peninsula cities and capturing or destroying nearly all Mexican vessels in the Gulf of California. Other mainland ports, not on the peninsula, were taken as well. The objective of the campaign was to take Mazatlan, a major supply base for Mexican forces. ''Cyane'' was given credit for eighteen captures and numerous destroyed ships. Entering the Gulf of California, ''Independence'', ''Congress'' and ''Cyane'' seized La Paz on the Baja California Peninsula, and captured and or burned the small Mexican fleet at Guaymas across the Gulf on the mainland. Within a month, they cleared the Gulf of hostile ships, destroying or capturing thirty vessels. Later on their sailors and marines captured the town of Mazatlan, Mexico, on 11 November 1847. A Mexican campaign to retake the various captured ports resulted in several small battles and at least two sieges occurred in which the Pacific Squadron ships provided support. ''Cyane'' returned to Norfolk on 9 October 1848 to receive the congratulations of the

After Alta California was secured most of the squadron proceeded down the Pacific coast capturing all major Baja California Peninsula cities and capturing or destroying nearly all Mexican vessels in the Gulf of California. Other mainland ports, not on the peninsula, were taken as well. The objective of the campaign was to take Mazatlan, a major supply base for Mexican forces. ''Cyane'' was given credit for eighteen captures and numerous destroyed ships. Entering the Gulf of California, ''Independence'', ''Congress'' and ''Cyane'' seized La Paz on the Baja California Peninsula, and captured and or burned the small Mexican fleet at Guaymas across the Gulf on the mainland. Within a month, they cleared the Gulf of hostile ships, destroying or capturing thirty vessels. Later on their sailors and marines captured the town of Mazatlan, Mexico, on 11 November 1847. A Mexican campaign to retake the various captured ports resulted in several small battles and at least two sieges occurred in which the Pacific Squadron ships provided support. ''Cyane'' returned to Norfolk on 9 October 1848 to receive the congratulations of the Secretary of the Navy

The secretary of the Navy (or SECNAV) is a statutory officer () and the head (chief executive officer) of the Department of the Navy, a military department (component organization) within the United States Department of Defense.

By law, the se ...

for her significant contributions to American victories in Mexico. Other ships headed home too. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, signed in February 1848 and its subsequent ratification by the United States and Mexican legislatures, marked the end of the Mexican–American War.

American Civil War

The extent of the Pacific Squadron's responsibility was further enlarged in the 1850s when California andOregon

Oregon () is a state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. The Columbia River delineates much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington, while the Snake River delineates much of its eastern boundary with Idah ...

were admitted as U.S. states and Navy bases on the west coast were established. The U.S. Sailing Navy's use of sailing ships declined as armored steamships were introduced before the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by state ...

. The Pacific Squadron was far removed from the fighting during the conflict though some vessels of the squadron were reassigned to duty in the Atlantic and fought in engagements such as the Battle of Forts Jackson and St. Philip.

Anti-Piracy operations

In July 1870 the pirate ship ''Forward'' attacked and captured the Mexican port city of Guaymas,Sonora

Sonora (), officially Estado Libre y Soberano de Sonora ( en, Free and Sovereign State of Sonora), is one of the 31 states which, along with Mexico City, comprise the Federal Entities of Mexico. The state is divided into 72 municipalities; the ...

in the Gulf of California. There the pirates robbed the foreign residents and persuaded by force the United States Consulate to supply ''Forward'' with coal, then the pirates sailed south for Boca Teacapan Boca Teacapan (Tecapan Mouth) is the outlet of the Estero de Teacapán (Tecapan Estuary) that drains two large coastal lagoons, Agua Grande Lagoon in Sinaloa and Agua Brava Lagoon in Nayarit to the Pacific Ocean. It forms part of the border between ...

, Sinaloa

Sinaloa (), officially the Estado Libre y Soberano de Sinaloa ( en, Free and Sovereign State of Sinaloa), is one of the 31 states which, along with Mexico City, comprise the Federal Entities of Mexico. It is divided into 18 municipalities and ...

. The Pacific Squadron, with Rear Admiral Shubrick, was informed of the incident so was sent to destroy the pirate threat. After arriving in the area in early August, ''Mohican''s men discovered that ''Forward'' was at Boca Teacapan's harbor in the Teacapan River. A boat expedition was launched and attacked the pirate ship on 17 August 1870. The battle ended with an American victory and the burning and sinking of the pirate steamer.

Oahu Expedition

An American expedition toOahu

Oahu () ( Hawaiian: ''Oʻahu'' ()), also known as "The Gathering Place", is the third-largest of the Hawaiian Islands. It is home to roughly one million people—over two-thirds of the population of the U.S. state of Hawaii. The island of O� ...

occurred in late 1873 to early 1874. The Pacific Squadron sloops USS ''Tuscarora'' and USS ''Portsmouth'', under Lieutenant Commander

Lieutenant commander (also hyphenated lieutenant-commander and abbreviated Lt Cdr, LtCdr. or LCDR) is a commissioned officer rank in many navies. The rank is superior to a lieutenant and subordinate to a commander. The corresponding rank i ...

Theodore F. Jewell

Theodore Frelinghuysen Jewell (August 5, 1844 – July 26, 1932) was a rear admiral of the United States Navy.

Naval career

Jewell was appointed an acting midshipman on November 29, 1861, when he entered the United States Naval Academy. His clas ...

, set sail to open negotiations with King Lunalilo about the duty-free exportation of sugar from the island to America. However, during the proceedings, Lunalilo died on February 3 of 1874 which suspended negotiations until the electoral process was completed. The wife of the king, Queen Emma

Emma may refer to:

* Emma (given name)

Film

* Emma (1932 film), ''Emma'' (1932 film), a comedy-drama film by Clarence Brown

* Emma (1996 theatrical film), ''Emma'' (1996 theatrical film), a film starring Gwyneth Paltrow

* Emma (1996 TV film), '' ...

ran against the future King Kalakaua and when he won she was very upset and decided to lead an armed mob in an attack on the representatives in Honolulu

Honolulu (; ) is the capital and largest city of the U.S. state of Hawaii, which is in the Pacific Ocean. It is an unincorporated county seat of the consolidated City and County of Honolulu, situated along the southeast coast of the islan ...

courthouse. As result 150 sailors and marines were landed from the American ships plus another seventy to eighty from the British sloop HMS ''Tenedos''. The riot was mostly quelled by nightfall but an occupation lasted until February 20 by which time negotiations regarding sugar were concluded, the king also allowed the Americans to build their first repair and coaling station in Pearl Harbor

Pearl Harbor is an American lagoon harbor on the island of Oahu, Hawaii, west of Honolulu. It was often visited by the Naval fleet of the United States, before it was acquired from the Hawaiian Kingdom by the U.S. with the signing of the ...

.

Second Samoan Civil War

In 1899 another civil war broke out in

In 1899 another civil war broke out in Samoa

Samoa, officially the Independent State of Samoa; sm, Sāmoa, and until 1997 known as Western Samoa, is a Polynesian island country consisting of two main islands (Savai'i and Upolu); two smaller, inhabited islands (Manono Island, Manono an ...

between rebels loyal to the Mata'afa Iosefo

Mata'afa Iosefo (1832 – 6 February 1912) was a Paramount Chief of Samoa who was one of the three rival candidates for the kingship of Samoa during colonialism. He was also referred to as Tupua Malietoa To'oa Mata'afa Iosefo. He was crowned th ...

and federal forces of Malietoa Tanumafili I

Susuga Malietoa Tanumafili I (1879 – 5 July 1939) was the Malietoa in Samoa from 1898 until his death in 1939.

Personal and political life

Tanumafili was born in 1880 to Malietoa Laupepa and Sisavai‘i Malupo Niuva‘ai. He attended the Lon ...

. Pacific Squadron Rear Admiral Albert Kautz

Rear Admiral Albert Kautz (January 29, 1839 – February 6, 1907) was an officer of the United States Navy who served during and after the American Civil War.

Biography

Kautz was born in Georgetown, Ohio, one of seven children of Johann George ...

in USS ''Philadelphia'' launched an expedition to the island and occupied the capital of Apia

Apia () is the capital and largest city of Samoa, as well as the nation's only city. It is located on the central north coast of Upolu, Samoa's second-largest island. Apia falls within the political district (''itūmālō'') of Tuamasaga.

Th ...

on March 14, 1899 after a battle

A battle is an occurrence of combat in warfare between opposing military units of any number or size. A war usually consists of multiple battles. In general, a battle is a military engagement that is well defined in duration, area, and force ...

and bombardment at the port city. From there American, British and Samoan forces engaged

An engagement or betrothal is the period of time between the declaration of acceptance of a marriage proposal and the marriage itself (which is typically but not always commenced with a wedding). During this period, a couple is said to be '' ...

in several actions against the rebels over the course of a few months. When the conflict ended the United States gained control of eastern Samoa which is today's American Samoa

American Samoa ( sm, Amerika Sāmoa, ; also ' or ') is an unincorporated territory of the United States located in the South Pacific Ocean, southeast of the island country of Samoa. Its location is centered on . It is east of the Internation ...

and the western half of the archipelago was taken by Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG),, is a country in Central Europe. It is the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany lies between the Baltic and North Sea to the north and the Alps to the sou ...

, creating the short lived German Samoa

German Samoa (german: Deutsch-Samoa) was a German protectorate from 1900 to 1920, consisting of the islands of Upolu, Savai'i, Apolima and Manono, now wholly within the independent state of Samoa, formerly ''Western Samoa''. Samoa was the ...

that was conquered during World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

.

Disbandment

In 1903, the Pacific Squadron consisted of the

In 1903, the Pacific Squadron consisted of the armored cruiser

The armored cruiser was a type of warship of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was designed like other types of cruisers to operate as a long-range, independent warship, capable of defeating any ship apart from a battleship and fast en ...

, the protected cruiser

Protected cruisers, a type of naval cruiser of the late-19th century, gained their description because an armoured deck offered protection for vital machine-spaces from fragments caused by shells exploding above them. Protected cruisers r ...

, the unprotected cruiser

An unprotected cruiser was a type of naval warship in use during the early 1870s Victorian or pre-dreadnought era (about 1880 to 1905). The name was meant to distinguish these ships from “ protected cruisers”, which had become accepted in ...

, and the gunboat

A gunboat is a naval watercraft designed for the express purpose of carrying one or more guns to bombard coastal targets, as opposed to those military craft designed for naval warfare, or for ferrying troops or supplies.

History Pre-ste ...

''Ranger''.

In early 1907, the U.S. Navy abolished both the Pacific Squadron and the United States Asiatic Fleet

The United States Asiatic Fleet was a fleet of the United States Navy during much of the first half of the 20th century. Before World War II, the fleet patrolled the Philippine Islands. Much of the fleet was destroyed by the Japanese by Februa ...

and established the new United States Pacific Fleet

The United States Pacific Fleet (USPACFLT) is a theater-level component command of the United States Navy, located in the Pacific Ocean. It provides naval forces to the Indo-Pacific Command. Fleet headquarters is at Joint Base Pearl Harbor� ...

. The ships and personnel of the Asiatic Fleet became the First Squadron of the Pacific Fleet, while the ships and personnel of the Pacific Squadron became the Pacific Fleet's Second Squadron.

Commanders-in-Chief

Pacific Squadron * Captain John Downes 1818–1820 * CaptainCharles Goodwin Ridgely

Charles Goodwin Ridgely (July 2, 1784 – February 8, 1848) was an officer in the United States Navy. He fought under Edward Preble in the First Barbary War (1804–1805), before serving as the commander of the Pacific Station (1820–1822) ...

1820–1821

* Commodore Charles Stewart 1821–1823

* Commodore Isaac Hull

Isaac Hull (March 9, 1773 – February 13, 1843) was a Commodore in the United States Navy. He commanded several famous U.S. naval warships including ("Old Ironsides") and saw service in the undeclared naval Quasi War with the revolutionary Fre ...

1823–1827

* Commodore Jacob Jones 1826–1829

* Commodore Charles C. B. Thompson

Charles is a masculine given name predominantly found in English and French speaking countries. It is from the French form ''Charles'' of the Proto-Germanic name (in runic alphabet) or ''*karilaz'' (in Latin alphabet), whose meaning was ...

1829–1831

* Commodore John Downes 1832–1834

* Commodore Alexander Scammel Wadsworth

Commodore Alexander Scammel Wadsworth (1790–April 5, 1851) was an officer of the United States Navy. His more than 40 years of active duty included service in the War of 1812.

Biography

Wadsworth was born in 1790 at Portland, Maine. He wa ...

1834–1836

* Commodore Henry E. Ballard 1837–1839

* Commodore Alexander Claxton

Alexander is a male given name. The most prominent bearer of the name is Alexander the Great, the king of the Ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia who created one of the largest empires in ancient history.

Variants listed here are Aleksandar, Al ...

1839–1841

* Commodore Thomas ap Catesby Jones 1842–1843

* Commodore Alexander J. Dallas 1843–1844

* Captain James Armstrong 1844

* Commodore John Drake Sloat

John Drake Sloat (July 26, 1781 – November 28, 1867) was a commodore in the United States Navy who, in 1846, claimed California for the United States.

Life

He was born at the family home of Sloat House in Sloatsburg, New York, of Dutch ancestr ...

1844–1846

* Commodore Robert Field Stockton 1846

* Commodore James Biddle

James Biddle (February 18, 1783 – October 1, 1848), of the Biddle family, brother of financier Nicholas Biddle and nephew of Capt. Nicholas Biddle, was an American commodore. His flagship was .

Education and early career

Biddle was born in ...

March 2 – July 19, 1847

* Commodore W. Branford Shubrick

William Branford Shubrick (October 31, 1790 – May 27, 1874) was an officer in the United States Navy. His active-duty career extended from 1806 to 1861, including service in the War of 1812 and the Mexican–American War; he was placed on the ret ...

1847–1848

* Commodore Thomas ap Catesby Jones 1848–1850

* Commodore Charles S. McCauley 1850–1853

* Commodore Bladen Dulany Bladen may refer to:

* Bladen, Belize, a village in Toledo District, Belize

* Bladen, Georgia

* Bladen County, North Carolina

* Bladen, Nebraska

Bladen is a village in Webster County, Nebraska, United States. The population was 237 at the 2010 ...

1853–1855

* Commodore William Mervine September 1855–October 1857

* Commodore John C. Long

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Second E ...

1857–1859

* Commodore John B. Montgomery 1859 – January 2, 1862

* Acting Rear Admiral Charles H. Bell January 2, 1862 – October 25, 1864

* Rear Admiral George F. Pearson

George Frederick Pearson (1799 – July 1, 1867) was rear-admiral of the United States Navy, commanding the Pacific Squadron during the later part of the American Civil War.

Early life and career

George F. Pearson was born in Portsmouth, New Hamp ...

, October 4, 1864 – 1866

North Pacific Squadron 1866–1869

* Rear Admiral Henry K. Thatcher 1866–1868

* Rear Admiral Thomas T. Craven

Thomas may refer to:

People

* List of people with given name Thomas

* Thomas (name)

* Thomas (surname)

* Saint Thomas (disambiguation)

* Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) Italian Dominican friar, philosopher, and Doctor of the Church

* Thomas the Ap ...

1868–1869

South Pacific Squadron 1866–1869

* Rear Admiral George F. Pearson

George Frederick Pearson (1799 – July 1, 1867) was rear-admiral of the United States Navy, commanding the Pacific Squadron during the later part of the American Civil War.

Early life and career

George F. Pearson was born in Portsmouth, New Hamp ...

, October 25, 1866 – 1867

* Rear Admiral John A. B. Dahlgren

John Adolphus Bernard Dahlgren (November 13, 1809 – July 12, 1870) was a United States Navy officer who founded his service's Ordnance Department and launched significant advances in gunnery.

Dahlgren devised a smoothbore howitzer, adaptable ...

1867–1869

* Rear Admiral Thomas Turner 1869–1870

Pacific Station 1872–1878

* Rear Admiral Thomas Turner 1869–1870

* Rear Admiral John Ancrum Winslow 1870–1872

* Rear Admiral John J. Almy

John Jay Almy (April 21, 1815 – May 16, 1895) was a U.S. Navy Rear-Admiral, who held the record for the longest period of seagoing service (27 years, 10 months).

In the Mexican War, he took part in the capture of Vera Cruz, and in the Civil War, ...

September 1873 – July 1876

Pacific Squadron 1878–1907

* Rear Admiral Christopher Raymond Perry Rodgers

Rear Admiral Christopher Raymond Perry Rodgers (4 November 1819 – 8 January 1892) was an officer in the United States Navy. He served in the Mexican–American War, the American Civil War, as superintendent of the Naval Academy, president of the ...

1878–1880

* Rear Admiral Thomas H. Stevens

Captain Thomas Holdup Stevens, USN (February 22, 1795 – January 21, 1841) was an American naval commander in the War of 1812.

Born in Charleston, South Carolina, Thomas Holdup was orphaned at an early age and was adopted by General Daniel St ...

1880–1881

* Rear Admiral Lewis Kimberly 1887–1890

* Commodore Joseph S. Skerrett

Rear Admiral Joseph Salathiel Skerrett (18 January 1833 – 1 January 1897) was an officer in the United States Navy. He participated in one of the most successful actions of the African Slave Trade Patrol, fought in the American Civil War, ...

1892–1893

* Rear Admiral John Irwin 1893–1894

* Rear Admiral Lester A. Beardslee

Lester Anthony Beardslee (February 1, 1836 – November 10, 1903) was an officer in the United States Navy who served as the commander of the Department of Alaska and of from June 14, 1879, to September 12, 1880.

Life

Beardslee was born in Lit ...

1894–1897

* Rear Admiral J. N. Miller

''J. The Jewish News of Northern California'', formerly known as ''Jweekly'', is a weekly print newspaper in Northern California, with its online edition updated daily. It is owned and operated by San Francisco Jewish Community Publications In ...

July 27, 1898

* Rear Admiral Albert Kautz

Rear Admiral Albert Kautz (January 29, 1839 – February 6, 1907) was an officer of the United States Navy who served during and after the American Civil War.

Biography

Kautz was born in Georgetown, Ohio, one of seven children of Johann George ...

1898-1901

* Rear Admiral Silas Casey III

Silas Casey III (11 September 1841 – 14 August 1913) was a United States Navy rear admiral. He served as commander of the Pacific Squadron from 1901 to 1903.

Biography

Casey was born at his family's property in Washington County, Rhode Island ...

1901 – 1903

* Rear Admiral Henry Glass 1903 – March 1905

* Rear Admiral Caspar Frederick Goodrich

Caspar Frederick Goodrich (7 January 1847 – 26 January 1925) was an admiral of the United States Navy, who served in the Spanish–American War and World War I.

Biography

Goodrich was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He was the son of Willi ...

1905–1906

* Rear Admiral William T. Swinburne

William T. Swinburne (August 24, 1847 – March 3, 1928) was a rear admiral of the United States Navy and one-time Commander-in-Chief of the United States Pacific Fleet.

Biography

He was born in Newport, Rhode Island, and entered the Navy on ...

1906–1907

Ships

1845–1849 * , frigate ( razee); 54 guns, ~500 crew, * , frigate; 44 guns, 480 crew * , frigate; 44 guns, 480 crew * ,ship of the line

A ship of the line was a type of naval warship constructed during the Age of Sail from the 17th century to the mid-19th century. The ship of the line was designed for the naval tactic known as the line of battle, which depended on the two colu ...

; 74 guns, 780 crew

* , sloop

A sloop is a sailboat with a single mast typically having only one headsail in front of the mast and one mainsail aft of (behind) the mast. Such an arrangement is called a fore-and-aft rig, and can be rigged as a Bermuda rig with triangular ...

; 20 guns, 200 crew

* , sloop; 20 guns, 200 crew

* , sloop; 20 guns, 200 crew

* , sloop; 16 guns, 150 crew - Stevenson's convoy escort

* , sloop, 16 guns, 150 crew

* , storeship

Combat stores ships, or storeships, were originally a designation given to ships in the Age of Sail and immediately afterward that navies used to stow supplies and other goods for naval purposes. Today, the United States Navy and the Royal Nav ...

(bark

Bark may refer to:

* Bark (botany), an outer layer of a woody plant such as a tree or stick

* Bark (sound), a vocalization of some animals (which is commonly the dog)

Places

* Bark, Germany

* Bark, Warmian-Masurian Voivodeship, Poland

Arts, ...

); 4 guns, ukn crew

* , storeship; 408 tons, 6 guns, ukn crew

* , storeship (sloop); 691 tons, 18 guns, ukn crew

* ''Brutus'', storeship - for Stevenson's regiment, chartered?

* ''Libertad'', Schooner; ukn guns, ~20 crew

* plus other ships captured during the war against Mexico

1851

* , frigate; 44 guns, 480 crew

* , frigate; 44 guns, 480 crew

* , sloop; 20 guns, 200 crew

* , sloop; 20 guns, 200 crew

* , sloop; 20 guns, 200 crew

* , sloop; 20 guns, 200 crew

* , storeship (sloop); 20 guns, 200 crew

* , storeship

* , storeship

* , storeship

* , steamer

1861-1865

1861

* , screw sloop

A screw sloop is a propeller-driven sloop-of-war. In the 19th century, during the introduction of the steam engine, ships driven by propellers were differentiated from those driven by paddle-wheels by referring to the ship's ''screws'' (propel ...

-of-war, 24 × 9 in (230 mm) smoothbore Dahlgren guns

Dahlgren guns were muzzle-loading naval artillery designed by Rear Admiral John A. Dahlgren USN (November 13, 1809 – July 12, 1870), mostly used in the period of the American Civil War. Dahlgren's design philosophy evolved from an accidental ...

, 1 × 2 in (51 mm) smoothbore Dahlgren gun, 2 × 30-pounder Parrott rifles, 367 men

* , side wheel steam sloop-of-war

In the 18th century and most of the 19th, a sloop-of-war in the Royal Navy was a warship with a single gun deck that carried up to eighteen guns. The rating system covered all vessels with 20 guns and above; thus, the term ''sloop-of-war'' enco ...

, 9 × 8-inch guns, complement unknown

* , screw sloop-of-war, 2 × 11 in (280 mm) smoothbore Dahlgren guns

Dahlgren guns were muzzle-loading naval artillery designed by Rear Admiral John A. Dahlgren USN (November 13, 1809 – July 12, 1870), mostly used in the period of the American Civil War. Dahlgren's design philosophy evolved from an accidental ...

, 1 × 60-pounder Parrott rifle, 3 × 32-pounder guns, 198 men

* , 2nd class screw sloop-of-war, 1 × 11 in (280 mm) gun, 4 × 32-pounder guns, 50 men

* , sloop of war, 16 × 32-pounder guns, 6 × 8 in (200 mm) guns, 195 men

* , sloop 20 guns, 200 crew

* , , 2 × 15 inch smoothbore cannons, 76 men/ref> * , lighthouse tender steamer

See also

*History of the United States Navy

The history of the United States Navy divides into two major periods: the "Old Navy", a small but respected force of sailing ships that was notable for innovation in the use of ironclads during the American Civil War, and the "New Navy" the ...

References

External links

''Thence Round Cape Horn: The Story of United States Naval Forces on Pacific Station, 1818-1923''

book by Robert Erwin Johnson (1963)

{{US Squadrons First hand account of captain RICHARD GASSAWAY WATKINS * https://sites.rootsweb.com/~mdannear/firstfam/watkins.htm Ship squadrons of the United States Navy Maritime history of the United States Military history of the Pacific Ocean 1821 establishments in the United States 1907 disestablishments in the United States Hawaiian Kingdom–United States relations Pacific Coast Theater of the American Civil War