Pachyornis Elephantopus on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The heavy-footed moa (''Pachyornis elephantopus'') is a

The heavy-footed moa was discovered by W.B.D. Mantell at Awamoa, near

The heavy-footed moa was discovered by W.B.D. Mantell at Awamoa, near

Until recently it was unknown exactly what the diet of the heavy-footed moa consisted of. The fact that it had different head and beak shapes to its contemporaries suggested that it had a different diet, possibly of tougher vegetation as suggested by its preferred dry and shrubby habitat. Specialising in different foods would have also allowed it to avoid competition with other moa species which may have shared part of its range (

Until recently it was unknown exactly what the diet of the heavy-footed moa consisted of. The fact that it had different head and beak shapes to its contemporaries suggested that it had a different diet, possibly of tougher vegetation as suggested by its preferred dry and shrubby habitat. Specialising in different foods would have also allowed it to avoid competition with other moa species which may have shared part of its range (

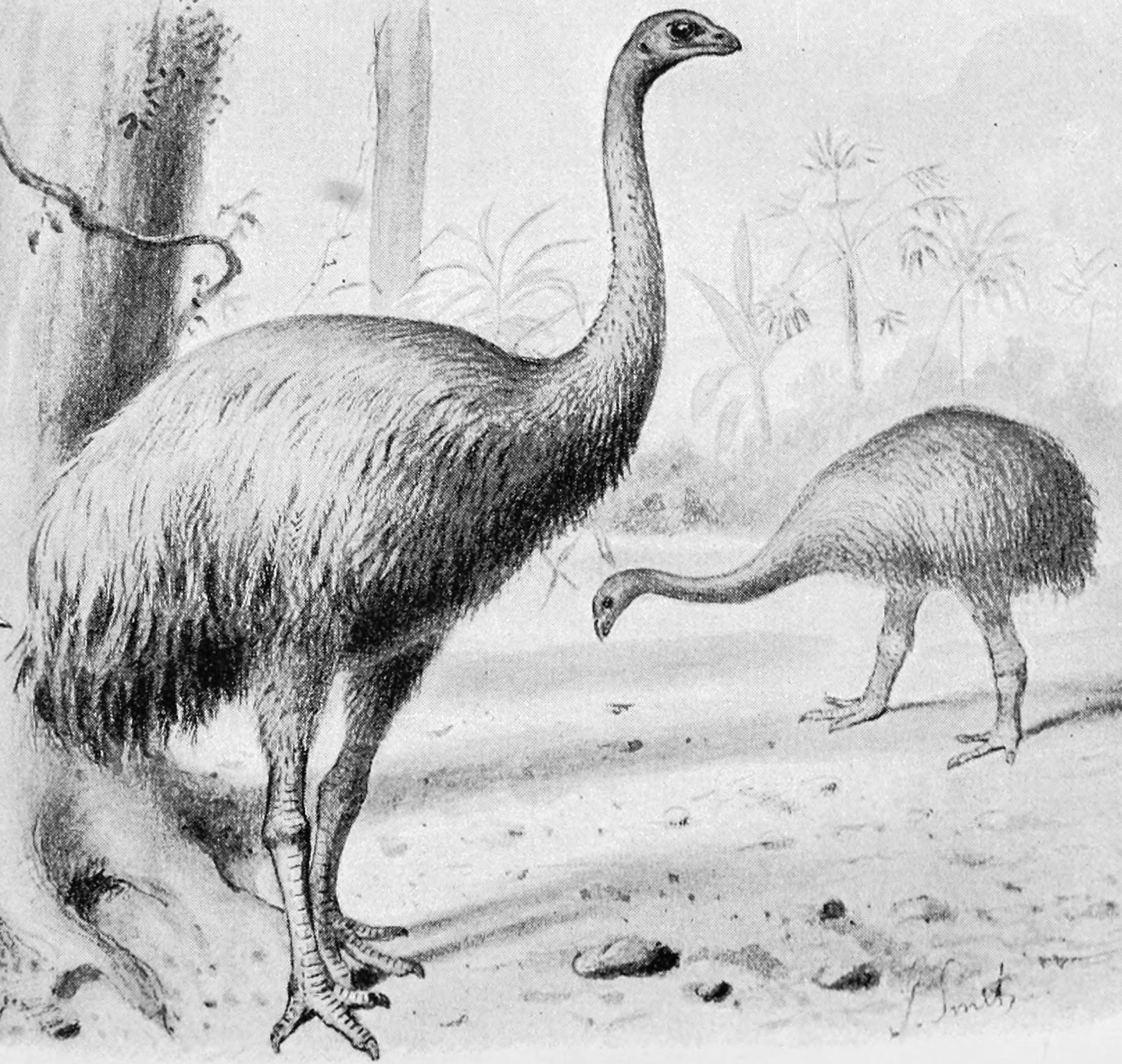

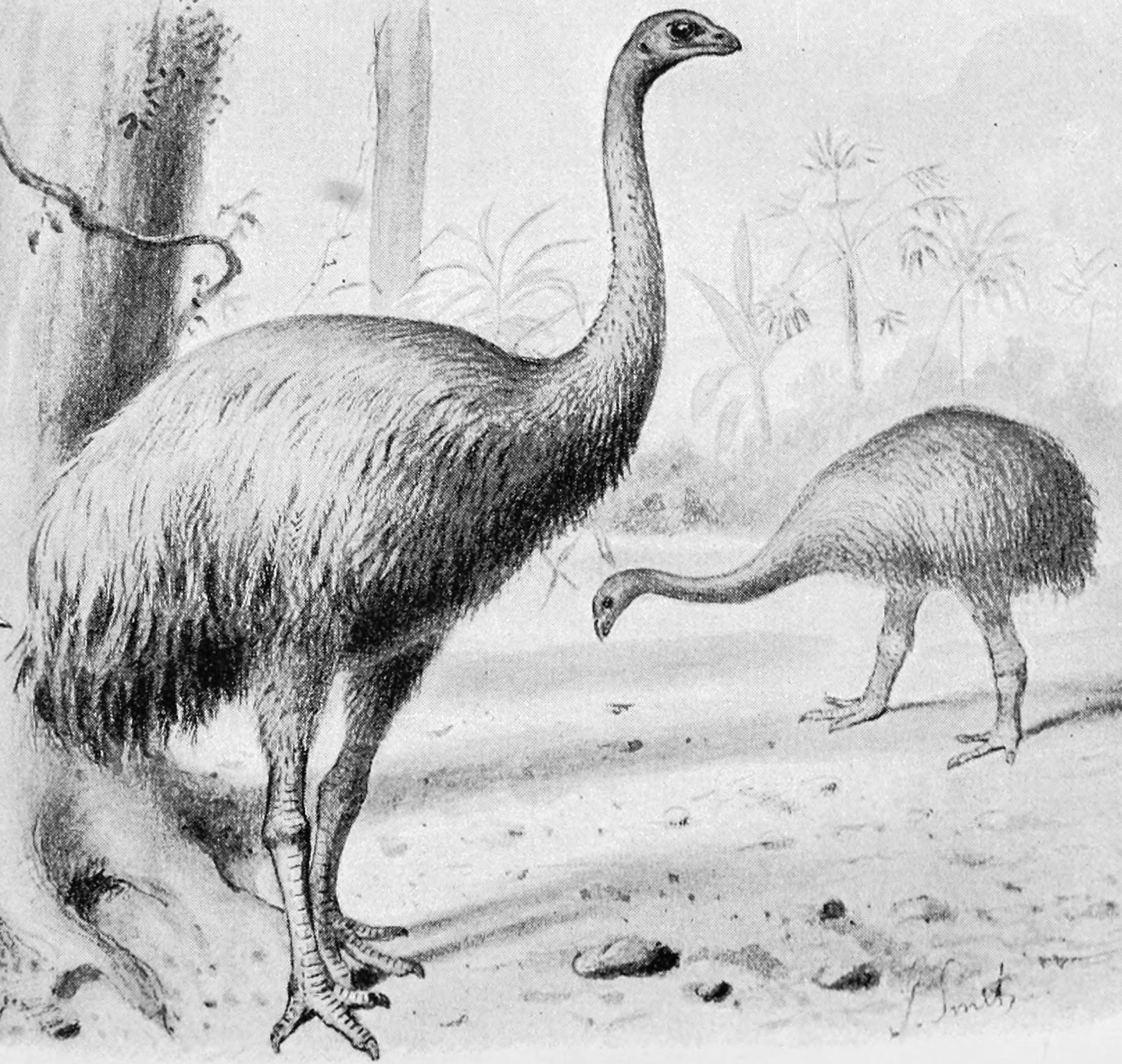

''Heavy-footed Moa. Pachyornis elephantopus''

by Paul Martinson. Artwork produced for the book Extinct Birds of New Zealand, by Alan Tennyson, Te Papa Press, Wellington, 2006 {{Taxonbar, from=Q13635746 Holocene extinctions Extinct flightless birds Extinct birds of New Zealand Late Quaternary prehistoric birds Ratites

species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate s ...

of moa

Moa are extinct giant flightless birds native to New Zealand.

The term has also come to be used for chicken in many Polynesian cultures and is found in the names of many chicken recipes, such as

Kale moa and Moa Samoa.

Moa or MOA may also refe ...

from the lesser moa family

Family (from la, familia) is a Social group, group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or Affinity (law), affinity (by marriage or other relationship). The purpose of the family is to maintain the well-being of its ...

. The heavy-footed moa was widespread only in the South Island

The South Island, also officially named , is the larger of the two major islands of New Zealand in surface area, the other being the smaller but more populous North Island. It is bordered to the north by Cook Strait, to the west by the Tasman ...

of New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island count ...

, and its habitat was the lowlands (shrublands, dunelands, grasslands, and forests). The moa were ratites

A ratite () is any of a diverse group of flightless, large, long-necked, and long-legged birds of the infraclass Palaeognathae. Kiwi, the exception, are much smaller and shorter-legged and are the only nocturnal extant ratites.

The systematics o ...

, flightless birds with a sternum

The sternum or breastbone is a long flat bone located in the central part of the chest. It connects to the ribs via cartilage and forms the front of the rib cage, thus helping to protect the heart, lungs, and major blood vessels from injury. Sh ...

without a keel

The keel is the bottom-most longitudinal structural element on a vessel. On some sailboats, it may have a hydrodynamic and counterbalancing purpose, as well. As the laying down of the keel is the initial step in the construction of a ship, in Br ...

. They also have a distinctive palate

The palate () is the roof of the mouth in humans and other mammals. It separates the oral cavity from the nasal cavity.

A similar structure is found in crocodilians, but in most other tetrapods, the oral and nasal cavities are not truly sepa ...

. The origin of these birds is becoming clearer as it is now believed that early ancestors of these birds were able to fly and flew to the southern areas in which they have been found.Davies, S. J. J. F. (2003)

The heavy-footed moa was about tall, and weighed as much as .Olliver, Narena (2005) Three complete or partially complete moa eggs in museum collections are considered eggs of the heavy-footed moa, all sourced from Otago

Otago (, ; mi, Ōtākou ) is a region of New Zealand located in the southern half of the South Island administered by the Otago Regional Council. It has an area of approximately , making it the country's second largest local government reg ...

. These have an average length of 226mm and a width of 158mm, making these the largest moa eggs behind the single South Island giant moa

The South Island giant moa (''Dinornis robustus'') is an extinct moa from the genus ''Dinornis.''

Context

The moa were ratites, flightless birds with a sternum without a keel. They also had a distinctive palate. The origin of these birds is b ...

egg specimen.

Discovery

The heavy-footed moa was discovered by W.B.D. Mantell at Awamoa, near

The heavy-footed moa was discovered by W.B.D. Mantell at Awamoa, near Oamaru

Oamaru (; mi, Te Oha-a-Maru) is the largest town in North Otago, in the South Island of New Zealand, it is the main town in the Waitaki District. It is south of Timaru and north of Dunedin on the Pacific coast; State Highway 1 and the railway ...

, and the bones were taken by him to England. Bones from multiple birds were used to make a full skeleton, which was then put in the British Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docum ...

. The name ''Dinornis elephantopus'' was given by Richard Owen.

Distribution and habitat

The heavy-footed moa was found only in theSouth Island

The South Island, also officially named , is the larger of the two major islands of New Zealand in surface area, the other being the smaller but more populous North Island. It is bordered to the north by Cook Strait, to the west by the Tasman ...

of New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island count ...

.

Their range covered much of the eastern side of the island, with a northern and southern variant of the species.

They were a primarily lowland species, preferring dry and open habitats such as grassland

A grassland is an area where the vegetation is dominated by grasses (Poaceae). However, sedge (Cyperaceae) and rush (Juncaceae) can also be found along with variable proportions of legumes, like clover, and other herbs. Grasslands occur natur ...

s, shrubland

Shrubland, scrubland, scrub, brush, or bush is a plant community characterized by vegetation dominated by shrubs, often also including grasses, herbs, and geophytes. Shrubland may either occur naturally or be the result of human activity. It m ...

s and dry forests. They were absent from sub-alpine

Montane ecosystems are found on the slopes of mountains. The alpine climate in these regions strongly affects the ecosystem because temperatures lapse rate, fall as elevation increases, causing the ecosystem to stratify. This stratification is ...

and mountain habitats, where they were replaced by the crested moa (''Pachyornis australis

The crested moa (''Pachyornis australis'') is an extinct species of moa. It is one of the 9 known species of moa to have existed.

Moa are grouped together with emus, ostriches, kiwi, cassowaries, rheas, and tinamous in the clade Palaeognat ...

'').

During the Pleistocene

The Pleistocene ( , often referred to as the ''Ice age'') is the geological Epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 2,580,000 to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was fina ...

-Holocene

The Holocene ( ) is the current geological epoch. It began approximately 11,650 cal years Before Present (), after the Last Glacial Period, which concluded with the Holocene glacial retreat. The Holocene and the preceding Pleistocene togethe ...

warming event, the retreat of glacial ice meant that the heavy-footed moa's preferred habitat area increased, allowing their distribution across the island to increase as well.

Ecology and diet

Due to its relative isolation before the Polynesian settlers arrived, New Zealand has a unique plant and animal community and had no native terrestrial mammals. Moa filled the ecological niche of large herbivores, filled by mammals elsewhere, until the arrival of the Polynesian settlers and the associated mammalian invasion in the 13th Century. The heavy-footed Moa is thought to have been less abundant than other moa species due to its less frequent representation in thefossil record

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved in ...

.

Until recently it was unknown exactly what the diet of the heavy-footed moa consisted of. The fact that it had different head and beak shapes to its contemporaries suggested that it had a different diet, possibly of tougher vegetation as suggested by its preferred dry and shrubby habitat. Specialising in different foods would have also allowed it to avoid competition with other moa species which may have shared part of its range (

Until recently it was unknown exactly what the diet of the heavy-footed moa consisted of. The fact that it had different head and beak shapes to its contemporaries suggested that it had a different diet, possibly of tougher vegetation as suggested by its preferred dry and shrubby habitat. Specialising in different foods would have also allowed it to avoid competition with other moa species which may have shared part of its range (niche separation

In ecology, niche differentiation (also known as niche segregation, niche separation and niche partitioning) refers to the process by which competing species use the environment differently in a way that helps them to coexist. The competitive exc ...

). In 2007 Jamie Wood described the gizzard

The gizzard, also referred to as the ventriculus, gastric mill, and gigerium, is an organ found in the digestive tract of some animals, including archosaurs (pterosaurs, crocodiles, alligators, dinosaurs, birds), earthworms, some gastropods, so ...

contents of a heavy-footed moa for the first time. They found 21 plant taxa

In biology, a taxon (back-formation from ''taxonomy''; plural taxa) is a group of one or more populations of an organism or organisms seen by taxonomists to form a unit. Although neither is required, a taxon is usually known by a particular nam ...

which included '' Hebe'' leaves, various seeds and mosses as well as a large amount of twigs and wood, some of which were of a considerable size. This supports the earlier idea that the heavy-footed moa was adapted to consume tough vegetation, but it also shows that it had a varied diet and could eat most plant products, including wood.

The heavy-footed moa's only real predator (before the arrival of humans and non-native placental mammals) was the Haast's eagle

Haast's eagle (''Hieraaetus moorei'') is an extinct species of eagle that once lived in the South Island of New Zealand, commonly accepted to be the pouakai of Māori legend.coprolite

A coprolite (also known as a coprolith) is fossilized feces. Coprolites are classified as trace fossils as opposed to body fossils, as they give evidence for the animal's behaviour (in this case, diet) rather than morphology. The name is de ...

s has shown that they also hosted several groups of host-specific parasite

Parasitism is a close relationship between species, where one organism, the parasite, lives on or inside another organism, the host, causing it some harm, and is adapted structurally to this way of life. The entomologist E. O. Wilson has ...

s, including nematode

The nematodes ( or grc-gre, Νηματώδη; la, Nematoda) or roundworms constitute the phylum Nematoda (also called Nemathelminthes), with plant-Parasitism, parasitic nematodes also known as eelworms. They are a diverse animal phylum inhab ...

worms.

Museum specimens

The articulated skeleton of a heavy-footed moa fromOtago

Otago (, ; mi, Ōtākou ) is a region of New Zealand located in the southern half of the South Island administered by the Otago Regional Council. It has an area of approximately , making it the country's second largest local government reg ...

, New Zealand, is on display in the Collectors' Cabinet gallery at Leeds City Museum

Leeds City Museum, originally established in 1819, reopened in 2008 in Leeds, West Yorkshire, England. It is housed in the former Mechanics' Institute built by Cuthbert Brodrick, in Cookridge Street (now Millennium Square). It is one of nine s ...

, UK.

References

* * *External links

''Heavy-footed Moa. Pachyornis elephantopus''

by Paul Martinson. Artwork produced for the book Extinct Birds of New Zealand, by Alan Tennyson, Te Papa Press, Wellington, 2006 {{Taxonbar, from=Q13635746 Holocene extinctions Extinct flightless birds Extinct birds of New Zealand Late Quaternary prehistoric birds Ratites