Ottoman Greece on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Most of the areas which today are within modern

File:Zonaro GatesofConst.jpg, Sultan Mehmed II's entry into Constantinople

File:OttomanJanissariesAndDefendingKnightsOfStJohnSiegeOfRhodes1522.jpg, Ottoman

The consolidation of Ottoman rule was followed by two distinct trends of Greek migration. The first entailed Greek intellectuals, such as

The consolidation of Ottoman rule was followed by two distinct trends of Greek migration. The first entailed Greek intellectuals, such as

The Sultan sat at the apex of the government of the Ottoman Empire. Although he had the trappings of an absolute ruler, he was actually bound by tradition and convention. These restrictions imposed by tradition were mainly of a religious nature. Indeed, the Qur'an was the main restriction on absolute rule by the sultan and in this way, the Qur'an served as a "constitution."

Ottoman rule of the provinces was characterized by two main functions. The local administrators within the provinces were to maintain a military establishment and to collect taxes.C. M. Woodhouse, ''Modern Greece: A Short History'', p. 101. The military establishment was feudal in character. The Sultan's cavalry were allotted land, either large allotments or small allotments based on the rank of the individual cavalryman. All non-Muslims were forbidden to ride a horse which made traveling more difficult. The Ottomans divided Greece into six ''

The Sultan sat at the apex of the government of the Ottoman Empire. Although he had the trappings of an absolute ruler, he was actually bound by tradition and convention. These restrictions imposed by tradition were mainly of a religious nature. Indeed, the Qur'an was the main restriction on absolute rule by the sultan and in this way, the Qur'an served as a "constitution."

Ottoman rule of the provinces was characterized by two main functions. The local administrators within the provinces were to maintain a military establishment and to collect taxes.C. M. Woodhouse, ''Modern Greece: A Short History'', p. 101. The military establishment was feudal in character. The Sultan's cavalry were allotted land, either large allotments or small allotments based on the rank of the individual cavalryman. All non-Muslims were forbidden to ride a horse which made traveling more difficult. The Ottomans divided Greece into six ''

The conquered land was parceled out to Ottoman soldiers, who held it as feudal fiefs (''timars'' and ''ziamets'') directly under the Sultan's authority. This land could not be sold or inherited, but reverted to the Sultan's possession when the fief-holder ( timariot) died. During their life-times they served as cavalrymen in the Sultan's army, living well on the proceeds of their estates with the land being tilled largely by peasants. Many Ottoman timariots were descended from the pre-Ottoman Christian nobility, and shifted their allegiance to the Ottomans following the conquest of the Balkans. Conversion to Islam was not a requirement, and as late as the fifteenth century many timariots were known to be Christian, although their numbers gradually decreased over time.

The Ottomans basically installed this feudal system right over the top of the existing system of peasant tenure. The peasantry remained in possession of their own land and their tenure over their plot of land remained hereditary and inalienable. Nor was any military service ever imposed on the peasant by the Ottoman government. All non-Muslims were in theory forbidden from carrying arms, but this was ignored. Indeed, in regions such as Crete, almost every man carried arms.

Greek Christian families were, however, subject to a system of brutal forced conscription known as the devshirme. The Ottomans required that male children from Christian peasant villages be conscripted and enrolled in the corps of

The conquered land was parceled out to Ottoman soldiers, who held it as feudal fiefs (''timars'' and ''ziamets'') directly under the Sultan's authority. This land could not be sold or inherited, but reverted to the Sultan's possession when the fief-holder ( timariot) died. During their life-times they served as cavalrymen in the Sultan's army, living well on the proceeds of their estates with the land being tilled largely by peasants. Many Ottoman timariots were descended from the pre-Ottoman Christian nobility, and shifted their allegiance to the Ottomans following the conquest of the Balkans. Conversion to Islam was not a requirement, and as late as the fifteenth century many timariots were known to be Christian, although their numbers gradually decreased over time.

The Ottomans basically installed this feudal system right over the top of the existing system of peasant tenure. The peasantry remained in possession of their own land and their tenure over their plot of land remained hereditary and inalienable. Nor was any military service ever imposed on the peasant by the Ottoman government. All non-Muslims were in theory forbidden from carrying arms, but this was ignored. Indeed, in regions such as Crete, almost every man carried arms.

Greek Christian families were, however, subject to a system of brutal forced conscription known as the devshirme. The Ottomans required that male children from Christian peasant villages be conscripted and enrolled in the corps of

Greeks paid a land tax and a heavy tax on trade, the latter taking advantage of the wealthy Greeks to fill the state coffers. Greeks, like other Christians, were also made to pay the ''

Greeks paid a land tax and a heavy tax on trade, the latter taking advantage of the wealthy Greeks to fill the state coffers. Greeks, like other Christians, were also made to pay the ''

Over the course of the eighteenth century Ottoman landholdings, previously fiefs held directly from the Sultan, became hereditary estates ('' chifliks''), which could be sold or bequeathed to heirs. The new class of Ottoman landlords reduced the hitherto free Greek peasants to

Over the course of the eighteenth century Ottoman landholdings, previously fiefs held directly from the Sultan, became hereditary estates ('' chifliks''), which could be sold or bequeathed to heirs. The new class of Ottoman landlords reduced the hitherto free Greek peasants to

A secret Greek nationalist organization called the "Friendly Society" or "Company of Friends" (''Filiki Eteria'') was formed in Odessa in 1814. The members of the organization planned a rebellion with the support of wealthy Greek exile communities in United Kingdom, Britain and the United States. They also gained support from sympathizers in Western Europe, as well as covert assistance from Russia. The organization secured Capodistria, who became Russian Foreign Minister after leaving the Ionian Islands, as the leader of the planned revolt. On March 25 (now Greek Independence Day) 1821, the Orthodox Bishop Germanos of Patras proclaimed a national uprising. The Ottomans, in retaliation orchestrated the Constantinople massacre of 1821 and similar pogroms in Smyrna.

Simultaneous risings were planned across Greece, including in Macedonia,

A secret Greek nationalist organization called the "Friendly Society" or "Company of Friends" (''Filiki Eteria'') was formed in Odessa in 1814. The members of the organization planned a rebellion with the support of wealthy Greek exile communities in United Kingdom, Britain and the United States. They also gained support from sympathizers in Western Europe, as well as covert assistance from Russia. The organization secured Capodistria, who became Russian Foreign Minister after leaving the Ionian Islands, as the leader of the planned revolt. On March 25 (now Greek Independence Day) 1821, the Orthodox Bishop Germanos of Patras proclaimed a national uprising. The Ottomans, in retaliation orchestrated the Constantinople massacre of 1821 and similar pogroms in Smyrna.

Simultaneous risings were planned across Greece, including in Macedonia,

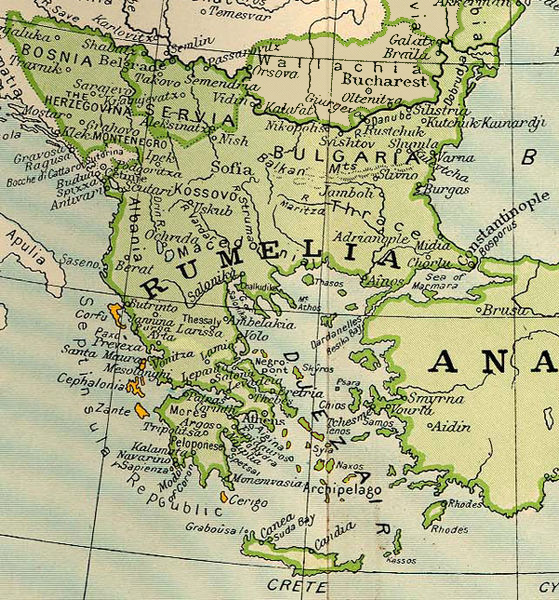

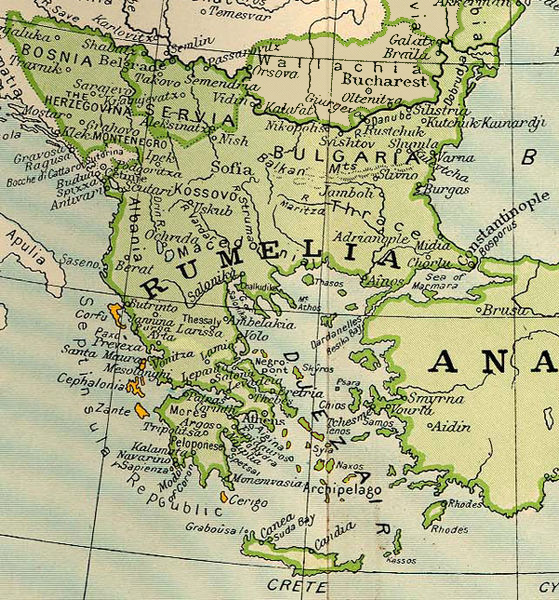

Macedonian Question: Turkish Domination

{{Greek War of Independence, state=collapsed Ottoman Greece, sv:Greklands historia#Osmanska tiden Ottoman Empire

Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders wi ...

's borders were at some point in the past part of the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University ...

. This period of Ottoman rule in Greece, lasting from the mid-15th century until the successful Greek War of Independence

The Greek War of Independence, also known as the Greek Revolution or the Greek Revolution of 1821, was a successful war of independence by Greek revolutionaries against the Ottoman Empire between 1821 and 1829. The Greeks were later assisted by ...

that broke out in 1821 and the proclamation of the First Hellenic Republic

The First Hellenic Republic ( grc-gre, Αʹ Ελληνική Δημοκρατία) was the provisional Greece, Greek state during the Greek War of Independence against the Ottoman Empire. From 1822 until 1827, it was known as the Provisional Ad ...

in 1822 (preceded by the creation of the autonomous Septinsular Republic in 1800), is known in Greek as ''Tourkokratia'' ( el, Τουρκοκρατία, "Turkish rule"; en, "Turkocracy"). Some regions, however, like the Ionian islands, various temporary Venetian

Venetian often means from or related to:

* Venice, a city in Italy

* Veneto, a region of Italy

* Republic of Venice (697–1797), a historical nation in that area

Venetian and the like may also refer to:

* Venetian language, a Romance language s ...

possessions of the Stato da Mar, or Mani peninsula

The Mani Peninsula ( el, Μάνη, Mánē), also long known by its medieval name Maina or Maïna (Μαΐνη), is a geographical and cultural region in Southern Greece that is home to the Maniots (Mανιάτες, ''Maniátes'' in Greek), who cl ...

in Peloponnese

The Peloponnese (), Peloponnesus (; el, Πελοπόννησος, Pelopónnēsos,(), or Morea is a peninsula and geographic region in southern Greece. It is connected to the central part of the country by the Isthmus of Corinth land bridge which ...

did not become part of the Ottoman administration, although the latter was under Ottoman suzerainty

Suzerainty () is the rights and obligations of a person, state or other polity who controls the foreign policy and relations of a tributary state, while allowing the tributary state to have internal autonomy. While the subordinate party is ca ...

.

The Eastern Roman Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantino ...

, the remnant of the ancient Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Roman Republic, Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings aro ...

which ruled most of the Greek-speaking world for over 1100 years, had been fatally weakened since the sacking of Constantinople by the Latin Crusaders in 1204.

The Ottoman advance into Greece was preceded by victory over the Serb

The Serbs ( sr-Cyr, Срби, Srbi, ) are the most numerous South Slavic ethnic group native to the Balkans in Southeastern Europe, who share a common Serbian ancestry, culture, history and language.

The majority of Serbs live in their na ...

s to its north. First, the Ottomans won the Battle of Maritsa in 1371. The Serb forces were then led by the King Vukašin of Serbia, the father of Prince Marko and the co-ruler of the last emperor from the Serbian Nemanjic dynasty. This was followed by another Ottoman draw in the 1389 Battle of Kosovo

The Battle of Kosovo ( tr, Kosova Savaşı; sr, Косовска битка) took place on 15 June 1389 between an army led by the Serbian Prince Lazar Hrebeljanović and an invading army of the Ottoman Empire under the command of Sultan ...

.

With no further threat by the Serbs and the subsequent Byzantine civil wars, the Ottomans besieged and took Constantinople in 1453 and then advanced southwards into Greece, capturing Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates a ...

in 1458. The Greeks held out in the Peloponnese

The Peloponnese (), Peloponnesus (; el, Πελοπόννησος, Pelopónnēsos,(), or Morea is a peninsula and geographic region in southern Greece. It is connected to the central part of the country by the Isthmus of Corinth land bridge which ...

until 1460, and the Venetians and Genoese clung to some of the islands, but by the early 16th century all of mainland Greece and most of the Aegean islands were in Ottoman hands, excluding several port cities still held by the Venetians (Nafplio

Nafplio ( ell, Ναύπλιο) is a coastal city located in the Peloponnese in Greece and it is the capital of the regional unit of Argolis and an important touristic destination. Founded in antiquity, the city became an important seaport in th ...

, Monemvasia, Parga

Parga ( el, Πάργα ) is a town and municipality located in the northwestern part of the regional unit of Preveza in Epirus, northwestern Greece. The seat of the municipality is the village Kanallaki. Parga lies on the Ionian coast between the ...

and Methone the most important of them). The mountains of Greece were largely untouched, and were a refuge for Greeks who desired to flee Ottoman rule and engage in guerrilla warfare

Guerrilla warfare is a form of irregular warfare in which small groups of combatants, such as paramilitary personnel, armed civilians, or irregulars, use military tactics including ambushes, sabotage, raids, petty warfare, hit-and-run ta ...

.

The Cyclades

The Cyclades (; el, Κυκλάδες, ) are an island group in the Aegean Sea, southeast of mainland Greece and a former administrative prefecture of Greece. They are one of the island groups which constitute the Aegean archipelago. The name ...

islands, in the middle of the Aegean, were officially annexed by the Ottomans in 1579, although they were under vassal status since the 1530s. Cyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is ...

fell in 1571, and the Venetians retained Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, ...

until 1669. The Ionian Islands were never ruled by the Ottomans, with the exception of Kefalonia

Kefalonia or Cephalonia ( el, Κεφαλονιά), formerly also known as Kefallinia or Kephallenia (), is the largest of the Ionian Islands in western Greece and the 6th largest island in Greece after Crete, Euboea, Lesbos, Rhodes and Chios. It ...

(from 1479 to 1481 and from 1485 to 1500), and remained under the rule of the Republic of Venice

The Republic of Venice ( vec, Repùblega de Venèsia) or Venetian Republic ( vec, Repùblega Vèneta, links=no), traditionally known as La Serenissima ( en, Most Serene Republic of Venice, italics=yes; vec, Serenìsima Repùblega de Venèsia ...

. It was in the Ionian Islands where modern Greek statehood was born, with the creation of the Republic of the Seven Islands in 1800.

Ottoman Greece was a multiethnic society

The term multiculturalism has a range of meanings within the contexts of sociology, political philosophy, and colloquial use. In sociology and in everyday usage, it is a synonym for " ethnic pluralism", with the two terms often used interchang ...

. However, the Ottoman system of ''millets'' did not correspond to the modern Western notion of multiculturalism

The term multiculturalism has a range of meanings within the contexts of sociology, political philosophy, and colloquial use. In sociology and in everyday usage, it is a synonym for " ethnic pluralism", with the two terms often used interchang ...

. The Greeks were given some privileges and freedom, but they were also suffering from the malpractices of its administrative personnel over which the central government had only remote and incomplete control. Despite losing their political independence, the Greeks remained dominant in the fields of commerce and business. The consolidation of Ottoman power in the 15th and 16th centuries rendered the Mediterranean safe for Greek shipping, and Greek shipowners became the maritime carriers of the Empire, making tremendous profits.http://press.princeton.edu/chapters/i9187.pdf However, Greek boys were systematically enslaved, the intelligent being castrated to be eunuch bureaucrats and the rest to become Janissaries after a forced conversion. The most beautiful Greek girls were enslaved to work as sex workers in the imperial harem.

This period of Ottoman rule had a profound impact in Greek society, as new elites emerged and the rest were oppressed and enslaved over centuries. The Greek land-owning aristocracy that traditionally dominated the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

suffered a tragic fate, and was almost completely destroyed. The new leading class in Ottoman Greece were the ''prokritoi'' (πρόκριτοι in Greek) called ''kocabaşi

The kodjabashis ( el, κοτζαμπάσηδες, kotzabasides; singular κοτζάμπασης, ''kotzabasis''; sh, kodžobaša, kodžabaša; from tr, kocabaṣı, hocabaṣı) were local Christian notables in parts of the Ottoman Balkans, most ...

s'' by the Ottomans. The prokritoi were essentially bureaucrats and tax collectors, and gained a negative reputation for corruption and nepotism. On the other hand, the Phanariots

Phanariots, Phanariotes, or Fanariots ( el, Φαναριώτες, ro, Fanarioți, tr, Fenerliler) were members of prominent Greek families in Phanar (Φανάρι, modern ''Fener''), the chief Greek quarter of Constantinople where the Ecumen ...

became prominent in the imperial capital of Constantinople as businessmen and diplomats, and the Greek Orthodox Church and the Ecumenical Patriarch

The ecumenical patriarch ( el, Οἰκουμενικός Πατριάρχης, translit=Oikoumenikós Patriárchēs) is the archbishop of Constantinople (Istanbul), New Rome and '' primus inter pares'' (first among equals) among the heads of th ...

rose to great power under the Sultan's protection, gaining religious control over the entire Orthodox population of the Empire, Greek, Albanian-speaking, Latin-speaking and Slavic.

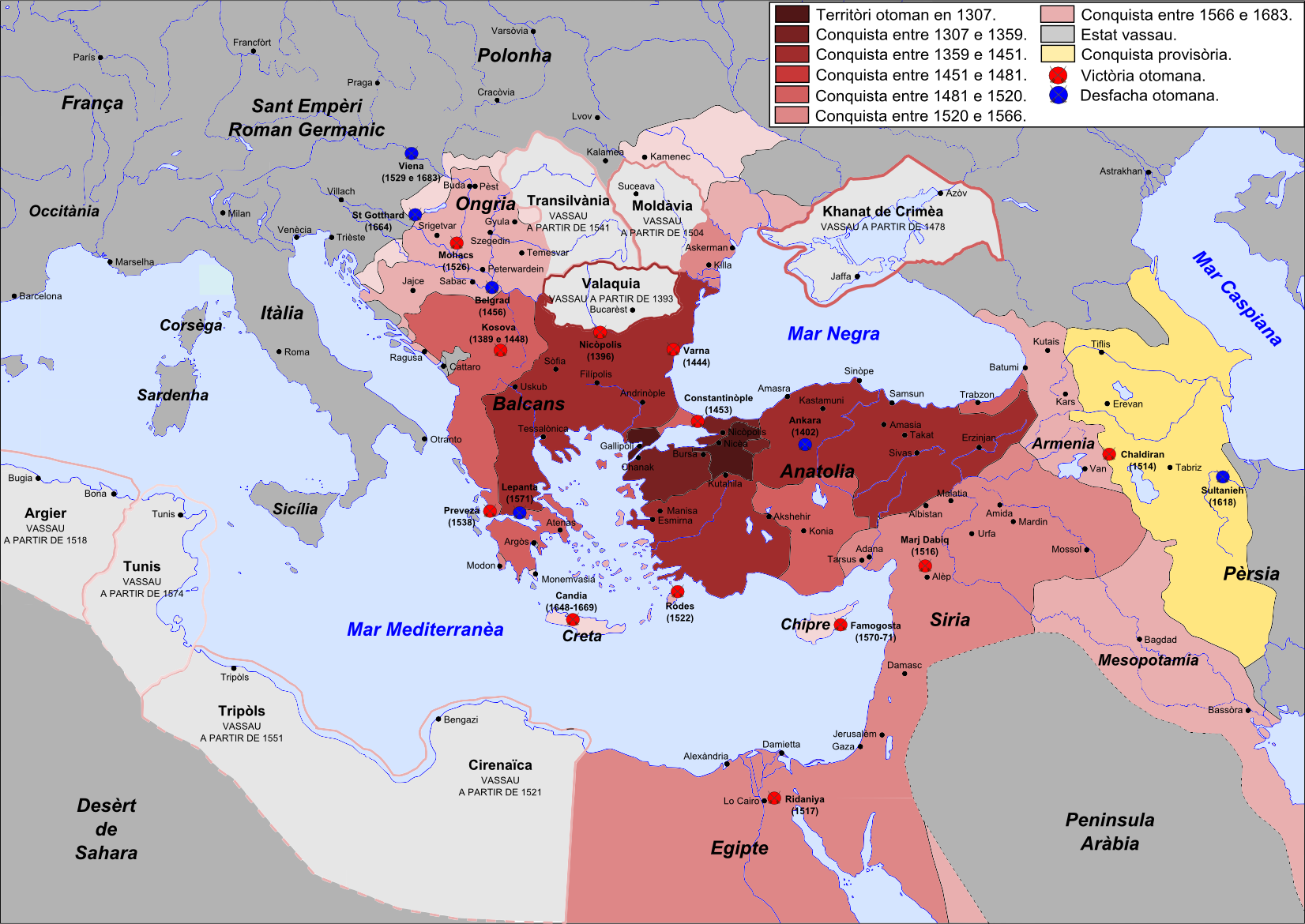

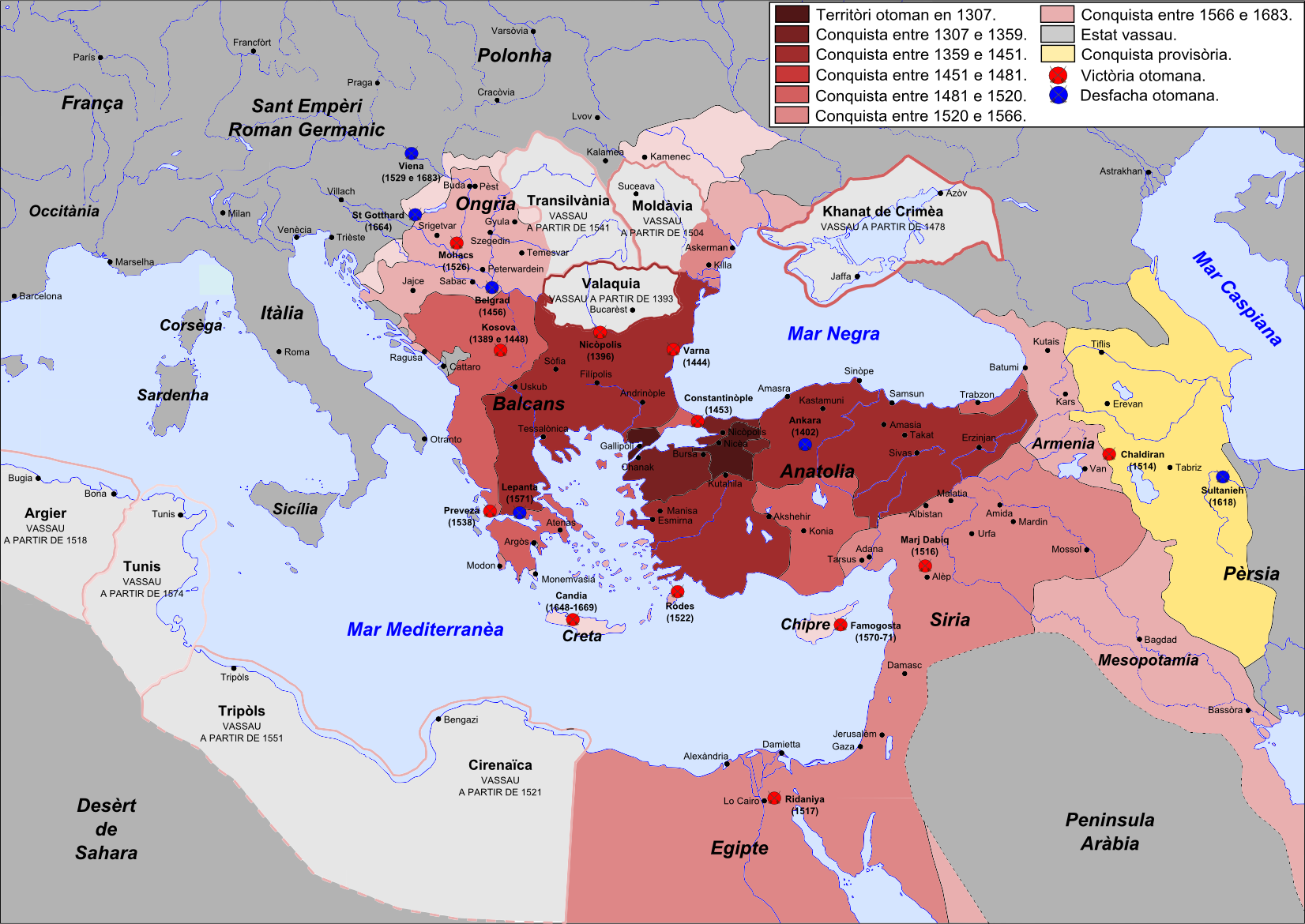

Ottoman expansion

After the fall of Constantinople to the Ottomans in 1453, the Despotate of the Morea was the last remnant of the Byzantine Empire to hold out against the Ottomans. However, it fell to the Ottomans in 1460, completing the conquest of mainland Greece. While most of mainland Greece and the Aegean islands was under Ottoman control by the end of the 15th century,Cyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is ...

and Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, ...

remained Venetian

Venetian often means from or related to:

* Venice, a city in Italy

* Veneto, a region of Italy

* Republic of Venice (697–1797), a historical nation in that area

Venetian and the like may also refer to:

* Venetian language, a Romance language s ...

territory and did not fall to the Ottomans until 1571 and 1670 respectively. The only part of the Greek-speaking world that escaped Ottoman rule was the Ionian Islands, which remained Venetian until 1797. Corfu

Corfu (, ) or Kerkyra ( el, Κέρκυρα, Kérkyra, , ; ; la, Corcyra.) is a Greek island in the Ionian Sea, of the Ionian Islands, and, including its small satellite islands, forms the margin of the northwestern frontier of Greece. The isl ...

withstood three major sieges in 1537, 1571 and 1716 all of which resulted in the repulsion of the Ottomans.

Other areas that remained part of the Venetian Stato da Màr include Nafplio

Nafplio ( ell, Ναύπλιο) is a coastal city located in the Peloponnese in Greece and it is the capital of the regional unit of Argolis and an important touristic destination. Founded in antiquity, the city became an important seaport in th ...

and Monemvasia until 1540, the Duchy of the Archipelago

The Duchy of the Archipelago ( el, Δουκάτο του Αρχιπελάγους, it, Ducato dell'arcipelago), also known as Duchy of Naxos or Duchy of the Aegean, was a maritime state created by Venetian interests in the Cyclades archipelago i ...

, centered on the islands of Naxos

Naxos (; el, Νάξος, ) is a Greek island and the largest of the Cyclades. It was the centre of archaic Cycladic culture. The island is famous as a source of emery, a rock rich in corundum, which until modern times was one of the best ab ...

and Paros

Paros (; el, Πάρος; Venetian: ''Paro'') is a Greek island in the central Aegean Sea. One of the Cyclades island group, it lies to the west of Naxos, from which it is separated by a channel about wide. It lies approximately south-east of ...

until 1579, Sifnos

Sifnos ( el, Σίφνος) is an island municipality in the Cyclades island group in Greece. The main town, near the center, known as Apollonia (pop. 869), is home of the island's folklore museum and library. The town's name is thought to com ...

until 1617 and Tinos

Tinos ( el, Τήνος ) is a Greek island situated in the Aegean Sea. It is located in the Cyclades archipelago. The closest islands are Andros, Delos, and Mykonos. It has a land area of and a 2011 census population of 8,636 inhabitants.

Tinos ...

until 1715.

Janissaries

A Janissary ( ota, یڭیچری, yeŋiçeri, , ) was a member of the elite infantry units that formed the Ottoman Sultan's household troops and the first modern standing army in Europe. The corps was most likely established under sultan Orhan ...

and defending Knights of Saint John

The Order of Knights of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem ( la, Ordo Fratrum Hospitalis Sancti Ioannis Hierosolymitani), commonly known as the Knights Hospitaller (), was a medieval and early modern Catholic military order. It was headqu ...

at the Siege of Rhodes (1522)

The siege of Rhodes of 1522 was the second and ultimately successful attempt by the Ottoman Empire to expel the Knights of Rhodes from their island stronghold and thereby secure Ottoman control of the Eastern Mediterranean. The first siege i ...

File:Battle of Preveza (1538).jpg, The "Battle of Preveza

The Battle of Preveza was a naval battle that took place on 28 September 1538 near Preveza in Ionian Sea in northwestern Greece between an Ottoman fleet and that of a Holy League assembled by Pope Paul III. It occurred in the same area in ...

" (1538) by Ohannes Umed Behzad

File:Battle of Lepanto 1571.jpg, The "Battle of Lepanto

The Battle of Lepanto was a naval engagement that took place on 7 October 1571 when a fleet of the Holy League, a coalition of Catholic states (comprising Spain and its Italian territories, several independent Italian states, and the Soverei ...

" (1571) prevented the Ottomans from expanding further

File:Vue du siege de Candie en 1669.jpg, Siege of Candia (1648-1669)

Ottoman rule

The consolidation of Ottoman rule was followed by two distinct trends of Greek migration. The first entailed Greek intellectuals, such as

The consolidation of Ottoman rule was followed by two distinct trends of Greek migration. The first entailed Greek intellectuals, such as Basilios Bessarion

Bessarion ( el, Βησσαρίων; 2 January 1403 – 18 November 1472) was a Byzantine Greek Renaissance humanist, theologian, Catholic cardinal and one of the famed Greek scholars who contributed to the so-called great revival of letters ...

, Georgius Plethon Gemistos and Marcos Mousouros

Marcus Musurus ( el, Μάρκος Μουσοῦρος ''Markos Mousouros''; it, Marco Musuro; c. 1470 – 1517) was a Greek scholar and philosopher born in Candia, Venetian Crete (modern Heraklion, Crete).

Life

The son of a rich merchant, Musu ...

, migrating to other parts of Western Europe and influencing the advent of the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ide ...

(though the large scale migration of Greeks to other parts of Europe, most notably Italian university cities, began far earlier, following the Crusader capture of Constantinople). This trend had also effect on the creation of the modern Greek diaspora

The Greek diaspora, also known as Omogenia ( el, Ομογένεια, Omogéneia), are the communities of Greeks living outside of Greece and Cyprus (excluding Northern Cyprus). Such places historically include Albania, North Macedonia, parts of ...

.

The second entailed Greeks leaving the plains of the Greek peninsula and resettling in the mountains, where the rugged landscape made it hard for the Ottomans to establish either military or administrative presence.

Administration

The Sultan sat at the apex of the government of the Ottoman Empire. Although he had the trappings of an absolute ruler, he was actually bound by tradition and convention. These restrictions imposed by tradition were mainly of a religious nature. Indeed, the Qur'an was the main restriction on absolute rule by the sultan and in this way, the Qur'an served as a "constitution."

Ottoman rule of the provinces was characterized by two main functions. The local administrators within the provinces were to maintain a military establishment and to collect taxes.C. M. Woodhouse, ''Modern Greece: A Short History'', p. 101. The military establishment was feudal in character. The Sultan's cavalry were allotted land, either large allotments or small allotments based on the rank of the individual cavalryman. All non-Muslims were forbidden to ride a horse which made traveling more difficult. The Ottomans divided Greece into six ''

The Sultan sat at the apex of the government of the Ottoman Empire. Although he had the trappings of an absolute ruler, he was actually bound by tradition and convention. These restrictions imposed by tradition were mainly of a religious nature. Indeed, the Qur'an was the main restriction on absolute rule by the sultan and in this way, the Qur'an served as a "constitution."

Ottoman rule of the provinces was characterized by two main functions. The local administrators within the provinces were to maintain a military establishment and to collect taxes.C. M. Woodhouse, ''Modern Greece: A Short History'', p. 101. The military establishment was feudal in character. The Sultan's cavalry were allotted land, either large allotments or small allotments based on the rank of the individual cavalryman. All non-Muslims were forbidden to ride a horse which made traveling more difficult. The Ottomans divided Greece into six ''sanjak

Sanjaks (liwāʾ) (plural form: alwiyāʾ)

* Armenian: նահանգ (''nahang''; meaning "province")

* Bulgarian: окръг (''okrǔg''; meaning "county", "province", or "region")

* el, Διοίκησις (''dioikēsis'', meaning "province" ...

s'', each ruled by a ''Sanjakbey'' accountable to the Sultan

Sultan (; ar, سلطان ', ) is a position with several historical meanings. Originally, it was an Arabic abstract noun meaning "strength", "authority", "rulership", derived from the verbal noun ', meaning "authority" or "power". Later, it c ...

, who established his capital in Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

in 1453.

The conquered land was parceled out to Ottoman soldiers, who held it as feudal fiefs (''timars'' and ''ziamets'') directly under the Sultan's authority. This land could not be sold or inherited, but reverted to the Sultan's possession when the fief-holder ( timariot) died. During their life-times they served as cavalrymen in the Sultan's army, living well on the proceeds of their estates with the land being tilled largely by peasants. Many Ottoman timariots were descended from the pre-Ottoman Christian nobility, and shifted their allegiance to the Ottomans following the conquest of the Balkans. Conversion to Islam was not a requirement, and as late as the fifteenth century many timariots were known to be Christian, although their numbers gradually decreased over time.

The Ottomans basically installed this feudal system right over the top of the existing system of peasant tenure. The peasantry remained in possession of their own land and their tenure over their plot of land remained hereditary and inalienable. Nor was any military service ever imposed on the peasant by the Ottoman government. All non-Muslims were in theory forbidden from carrying arms, but this was ignored. Indeed, in regions such as Crete, almost every man carried arms.

Greek Christian families were, however, subject to a system of brutal forced conscription known as the devshirme. The Ottomans required that male children from Christian peasant villages be conscripted and enrolled in the corps of

The conquered land was parceled out to Ottoman soldiers, who held it as feudal fiefs (''timars'' and ''ziamets'') directly under the Sultan's authority. This land could not be sold or inherited, but reverted to the Sultan's possession when the fief-holder ( timariot) died. During their life-times they served as cavalrymen in the Sultan's army, living well on the proceeds of their estates with the land being tilled largely by peasants. Many Ottoman timariots were descended from the pre-Ottoman Christian nobility, and shifted their allegiance to the Ottomans following the conquest of the Balkans. Conversion to Islam was not a requirement, and as late as the fifteenth century many timariots were known to be Christian, although their numbers gradually decreased over time.

The Ottomans basically installed this feudal system right over the top of the existing system of peasant tenure. The peasantry remained in possession of their own land and their tenure over their plot of land remained hereditary and inalienable. Nor was any military service ever imposed on the peasant by the Ottoman government. All non-Muslims were in theory forbidden from carrying arms, but this was ignored. Indeed, in regions such as Crete, almost every man carried arms.

Greek Christian families were, however, subject to a system of brutal forced conscription known as the devshirme. The Ottomans required that male children from Christian peasant villages be conscripted and enrolled in the corps of Janissaries

A Janissary ( ota, یڭیچری, yeŋiçeri, , ) was a member of the elite infantry units that formed the Ottoman Sultan's household troops and the first modern standing army in Europe. The corps was most likely established under sultan Orhan ...

for military training in the Sultan's army. Such recruitment was sporadic, and the proportion of children conscripted varied from region to region. The practice largely came to an end by the middle of the seventeenth century.

Under the Ottoman system of government, Greek society was at the same time fostered and restricted. With one hand the Turkish regime gave privileges and freedom to its subject people; with the other it imposed a tyranny deriving from the malpractices of its administrative personnel over which it exercised only remote and incomplete control. In fact the “rayahs” were downtrodden and exposed to the vagaries of Turkish administration and sometimes to the Greek landlords. The term rayah came to denote an underprivileged, tax-ridden and socially inferior population.

Economy

The economic situation of the majority of Greece deteriorated heavily during the Ottoman era of the country. Life became ruralized and militarized. Heavy burdens of taxation were placed on the Christian population, and many Greeks were reduced to subsistence farming whereas during prior eras the region had been heavily developed and urbanized. The exception to this rule was inConstantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

and the Venetian

Venetian often means from or related to:

* Venice, a city in Italy

* Veneto, a region of Italy

* Republic of Venice (697–1797), a historical nation in that area

Venetian and the like may also refer to:

* Venetian language, a Romance language s ...

-held Ionian islands, where many Greeks lived in prosperity.

After about 1600, the Ottomans resorted to military rule in parts of Greece, which provoked further resistance, and also led to economic dislocation and accelerated population decline. Ottoman landholdings, previously fiefs held directly from the Sultan, became hereditary estates (''chifliks''), which could be sold or bequeathed to heirs. The new class of Ottoman landlords reduced the hitherto free Greek farmers to serfdom, leading to depopulation of the plains, and to the flight of many people to the mountains, in order to escape poverty.

Religion

The Sultan regarded theEcumenical Patriarch

The ecumenical patriarch ( el, Οἰκουμενικός Πατριάρχης, translit=Oikoumenikós Patriárchēs) is the archbishop of Constantinople (Istanbul), New Rome and '' primus inter pares'' (first among equals) among the heads of th ...

of the Greek Orthodox Church

The term Greek Orthodox Church ( Greek: Ἑλληνορθόδοξη Ἐκκλησία, ''Ellinorthódoxi Ekklisía'', ) has two meanings. The broader meaning designates "the entire body of Orthodox (Chalcedonian) Christianity, sometimes also cal ...

as the leader of all Orthodox, Greeks or not, within the empire. The Patriarch was accountable to the Sultan for the good behavior of the Orthodox population, and in exchange he was given wide powers over the Orthodox communities, including the non-Greek Slavic peoples. The Patriarch controlled the courts and the schools, as well as the Church, throughout the Greek communities of the empire. This made Orthodox priests, together with the local magnates, called Prokritoi or Dimogerontes, the effective rulers of Greek towns and cities. Some Greek towns, such as Athens and Rhodes

Rhodes (; el, Ρόδος , translit=Ródos ) is the largest and the historical capital of the Dodecanese islands of Greece. Administratively, the island forms a separate municipality within the Rhodes regional unit, which is part of the S ...

, retained municipal self-government, while others were put under Ottoman governors. Several areas, such as the Mani Peninsula

The Mani Peninsula ( el, Μάνη, Mánē), also long known by its medieval name Maina or Maïna (Μαΐνη), is a geographical and cultural region in Southern Greece that is home to the Maniots (Mανιάτες, ''Maniátes'' in Greek), who cl ...

in the Peloponnese, and parts of Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, ...

(Sfakia) and Epirus

sq, Epiri rup, Epiru

, native_name_lang =

, settlement_type = Historical region

, image_map = Epirus antiquus tabula.jpg

, map_alt =

, map_caption = Map of ancient Epirus by Heinri ...

, remained virtually independent.

During the frequent Ottoman–Venetian Wars, the Greeks sided with the Venetians against the Ottomans, with a few exceptions. The Patriarchate of Constantinople in general remained loyal to the Ottomans against the western threats (as for example during the Dionysios Skylosophos

Dionysios Philosophos (Διονύσιος ο Φιλόσοφος, Dionysios the Philosopher) or Skylosophos ( el, Διονύσιος ο Σκυλόσοφος; c. 1541–1611), "the Dog-Philosopher" or "Dogwise" ("skylosophist"), as called by his r ...

revolt, etc). The Orthodox Church assisted greatly in the preservation of the Greek heritage, and adherence to the Greek Orthodox faith became increasingly a mark of Greek nationality.

As a rule, the Ottomans did not require the Greeks to become Muslim

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

s, although many did so on a superficial level in order to avert the socioeconomic hardships of Ottoman rule or because of the alleged corruption of the Greek clergy. The regions of Greece which had the largest concentrations of Ottoman Greek Muslims were Macedonia, notably the Vallaades, neighboring Epirus

sq, Epiri rup, Epiru

, native_name_lang =

, settlement_type = Historical region

, image_map = Epirus antiquus tabula.jpg

, map_alt =

, map_caption = Map of ancient Epirus by Heinri ...

, and Crete (see Cretan Muslims

The Cretan Muslims ( el, Τουρκοκρητικοί or , or ; tr, Giritli, , or ; ar, أتراك كريت) or Cretan Turks were the Muslim inhabitants of the island of Crete. Their descendants settled principally in Turkey, the Dodecanese ...

). Under the millet logic, Greek Muslims, despite often retaining elements of their Greek culture and language, were classified simply as "Muslim", although most Greek Orthodox

The term Greek Orthodox Church ( Greek: Ἑλληνορθόδοξη Ἐκκλησία, ''Ellinorthódoxi Ekklisía'', ) has two meanings. The broader meaning designates "the entire body of Orthodox (Chalcedonian) Christianity, sometimes also cal ...

Christians deemed them to have "turned-Turk" and therefore saw them as traitors to their original ethno-religious communities.The preaching of Islam: a history of the propagation of the Muslim faith By Sir Thomas Walker Arnold, pg. 137-138

Some Greeks either became New Martyrs, such as Saint Efraim the Neo-Martyr or Saint Demetrios the Neo-martyr while others became Crypto-Christians

Crypto-Christianity is the secret practice of Christianity, usually while attempting to camouflage it as another faith or observing the rituals of another religion publicly. In places and time periods where Christians were persecuted or Christiani ...

(Greek Muslims who were secret practitioners of the Greek Orthodox faith) in order to avoid heavy taxes and at the same time express their identity by maintaining their secret ties to the Greek Orthodox Church. Crypto-Christians officially ran the risk of being killed if they were caught practicing a non-Muslim religion once they converted to Islam. There were also instances of Greeks from theocratic or Byzantine nobility embracing Islam such as John Tzelepes Komnenos

John Komnenos ( gr, Ἰωάννης Κομνηνός, Iōannēs Komnēnos), later surnamed Tzelepes (Τζελέπης, ''Tzelepēs''), was the son of the ''sebastokrator'' Isaac Komnenos and grandson of the Byzantine emperor Alexios I Komnenos. A ...

and Misac Palaeologos Pasha.

Treatment of Christian subjects varied greatly under the rule of the Ottoman Sultans. Bayezid I

Bayezid I ( ota, بايزيد اول, tr, I. Bayezid), also known as Bayezid the Thunderbolt ( ota, link=no, یلدیرم بايزيد, tr, Yıldırım Bayezid, link=no; – 8 March 1403) was the Ottoman Sultan from 1389 to 1402. He adopted ...

, according to a Byzantine historian, freely admitted Christians into his society while trying to grow his empire, in the early Ottoman period. Later, although the Turkish ruler attempted to pacify the local population with a restoration of peacetime rule of law, the Christian population also became subject to special taxes and the tribute of Christian children to the Ottoman state to feed the ranks of the Janissary

A Janissary ( ota, یڭیچری, yeŋiçeri, , ) was a member of the elite infantry units that formed the Ottoman Sultan's household troops and the first modern standing army in Europe. The corps was most likely established under sultan Orhan ...

corps. Violent persecutions of Christians did nevertheless take place under the reign of Selim I

Selim I ( ota, سليم الأول; tr, I. Selim; 10 October 1470 – 22 September 1520), known as Selim the Grim or Selim the Resolute ( tr, links=no, Yavuz Sultan Selim), was the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1512 to 1520. Despite las ...

(1512-1520), known as Selim the Grim, who attempted to stamp out Christianity from the Ottoman Empire. Selim ordered the confiscation of all Christian churches, and while this order was later rescinded, Christians were heavily persecuted during his era.

Taxation and the "tribute of children"

Greeks paid a land tax and a heavy tax on trade, the latter taking advantage of the wealthy Greeks to fill the state coffers. Greeks, like other Christians, were also made to pay the ''

Greeks paid a land tax and a heavy tax on trade, the latter taking advantage of the wealthy Greeks to fill the state coffers. Greeks, like other Christians, were also made to pay the ''jizya

Jizya ( ar, جِزْيَة / ) is a per capita yearly taxation historically levied in the form of financial charge on dhimmis, that is, permanent non-Muslim subjects of a state governed by Islamic law. The jizya tax has been understood in ...

'', or Islamic poll-tax which all non-Muslims in the empire were forced to pay instead of the Zakat

Zakat ( ar, زكاة; , "that which purifies", also Zakat al-mal , "zakat on wealth", or Zakah) is a form of almsgiving, often collected by the Muslim Ummah. It is considered in Islam as a religious obligation, and by Quranic ranking, is ...

that Muslims must pay as part of the 5 pillars of Islam. Failure to pay the jizya could result in the pledge of protection of the Christian's life and property becoming void, facing the alternatives of conversion, enslavement, or death.

Like in the rest of the Ottoman Empire, Greeks had to carry a receipt certifying their payment of jizya at all times or be subject to imprisonment. Most Greeks did not have to serve in the Sultan's army, but the young boys that were taken away and converted to Islam were made to serve in the Ottoman military. In addition, girls were taken in order to serve as odalisques in harems.

These practices are called the "tribute of children" ('' devshirmeh'') (in Greek ''παιδομάζωμα'' ''paidomazoma'', meaning "child gathering"), whereby every Christian community was required to give one son in five to be raised as a Muslim and enrolled in the corps of Janissaries

A Janissary ( ota, یڭیچری, yeŋiçeri, , ) was a member of the elite infantry units that formed the Ottoman Sultan's household troops and the first modern standing army in Europe. The corps was most likely established under sultan Orhan ...

, elite units of the Ottoman army. There was much resistance to this. For example, Greek folklore tells of mothers crippling their sons to avoid their abduction. Nevertheless, entrance into the corps (accompanied by conversion to Islam) offered Greek boys the opportunity to advance as high as governor or even Grand Vizier

Grand vizier ( fa, وزيرِ اعظم, vazîr-i aʾzam; ota, صدر اعظم, sadr-ı aʾzam; tr, sadrazam) was the title of the effective head of government of many sovereign states in the Islamic world. The office of Grand Vizier was first ...

.

Opposition of the Greek populace to taxing or ''paidomazoma'' resulted in grave consequences. For example, in 1705 an Ottoman official was sent from Naoussa in Macedonia to search and conscript new Janissaries and was killed by Greek rebels who resisted the burden of the devshirmeh. The rebels were subsequently beheaded and their severed heads were displayed in the city of Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki (; el, Θεσσαλονίκη, , also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece, with over one million inhabitants in its metropolitan area, and the capital of the geographic region of ...

. In some cases, it was greatly feared as Greek families would often have to relinquish their own sons who would convert and return later as their oppressors. In other cases, the families bribed the officers to ensure that their children got a better life as a government officer.

Influence to tradition

After the 16th century, many Greek folk songs (''dimotika'') were produced and inspired from the way of life of the Greek people, brigands and the armed conflicts during the centuries of Ottoman rule. Klephtic songs (Greek: Κλέφτικα τραγούδια), or ballads, are a subgenre of the Greek folk music genre and are thematically oriented on the life of the klephts. Prominent conflicts were immortalised in several folk tales and songs, such as the epic ballad ''To tragoudi tou Daskalogianni'' of 1786, about the resistance warfare under Daskalogiannis.Emergence of Greek nationalism

serfdom

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism, and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery, which develop ...

, leading to further poverty and depopulation in the plains.

On the other hand, the position of educated and privileged Greeks within the Ottoman Empire improved greatly in the 17th and 18th centuries. From the late 1600s Greeks began to fill some of the highest and most important offices of the Ottoman state. The Phanariotes, a class of wealthy Greeks who lived in the Phanar district of Constantinople, became increasingly powerful. Their travels to Western Europe as merchants or diplomats brought them into contact with advanced ideas of liberalism

Liberalism is a Political philosophy, political and moral philosophy based on the Individual rights, rights of the individual, liberty, consent of the governed, political equality and equality before the law."political rationalism, hostilit ...

and nationalism

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a in-group and out-group, group of peo ...

, and it was among the Phanariotes that the modern Greek nationalist movement was born. Many Greek merchants and travelers were influenced by the ideas of the French revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are conside ...

and a new Age of Greek Enlightenment

The Modern Greek Enlightenment ( el, Διαφωτισμός, ''Diafotismos'', "enlightenment," "illumination"; also known as the Neo-Hellenic Enlightenment) was the Greek expression of the Age of Enlightenment.

Origins

The Greek Enlightenment w ...

was initiated at the beginning of the 19th century in many Ottoman-ruled Greek cities and towns.

Greek nationalism was also stimulated by agents of Catherine the Great

, en, Catherine Alexeievna Romanova, link=yes

, house =

, father = Christian August, Prince of Anhalt-Zerbst

, mother = Joanna Elisabeth of Holstein-Gottorp

, birth_date =

, birth_name = Princess Sophie of Anha ...

, the Orthodox ruler of the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War ...

, who hoped to acquire Ottoman territory, including Constantinople itself, by inciting a Christian rebellion against the Ottomans. However, during the Russian-Ottoman War which broke out in 1768, the Greeks did not rebel, disillusioning their Russian patrons. The Treaty of Kuchuk-Kainarji (1774) gave Russia the right to make "representations" to the Sultan in defense of his Orthodox subjects, and the Russians began to interfere regularly in the internal affairs of the Ottoman Empire. This, combined with the new ideas let loose by the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are conside ...

of 1789, began to reconnect the Greeks with the outside world and led to the development of an active nationalist movement, one of the most progressive of the time.

Greece was peripherally involved in the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fre ...

, but one episode had important consequences. When the French under Napoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader wh ...

seized Venice in 1797, they also acquired the Ionian Islands, thus ending the four hundredth year of Venetian rule over the Ionian Islands. The islands were elevated to the status of a French dependency called the Septinsular Republic, which possessed local autonomy. This was the first time Greeks had governed themselves since the fall of Trebizond in 1461.

Among those who held office in the islands was John Capodistria, destined to become independent Greece's first head of state. By the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815, Greece had re-emerged from its centuries of isolation. British and French writers and artists began to visit the country, and wealthy Europeans began to collect Greek antiquities. These " philhellenes" were to play an important role in mobilizing support for Greek independence.

Uprisings before 1821

Greeks in various places of the Greek peninsula would at times rise up against Ottoman rule, mainly while taking advantage of wars the Ottoman Empire would engage in. Those uprisings were of mixed scale and impact. During the Ottoman–Venetian War (1463–1479), theManiot

The Maniots or Maniates ( el, Μανιάτες) are the inhabitants of Mani Peninsula, located in western Laconia and eastern Messenia, in the southern Peloponnese, Greece. They were also formerly known as Mainotes and the peninsula as ''Maina''. ...

Kladas brothers, Krokodelos and Epifani, were leading bands of stratioti on behalf of Venice against the Turks in Southern Peloponnese. They put Vardounia and their lands into Venetian possession, for which Epifani then acted as governor.

Before and after the victory of the Holy League in 1571 at the Battle of Lepanto

The Battle of Lepanto was a naval engagement that took place on 7 October 1571 when a fleet of the Holy League, a coalition of Catholic states (comprising Spain and its Italian territories, several independent Italian states, and the Soverei ...

a series of conflicts broke out in the peninsula such as in Epirus, Phocis

Phocis ( el, Φωκίδα ; grc, Φωκίς) is one of the regional units of Greece. It is part of the administrative region of Central Greece. It stretches from the western mountainsides of Parnassus on the east to the mountain range of Var ...

(recorded in the ''Chronicle of Galaxeidi The ''Chronicle of Galaxeidi'' ( el, Χρονικό του Γαλαξειδίου) is a Greek chronicle written in the year 1703 detailing the history of the town of Galaxeidi on the northern shore of the Gulf of Corinth and its wider region, inclu ...

'') and the Peloponnese, led by the Melissinos brothers and others. They were crushed by the following year. Short-term revolts of local level occurred throughout the region such as the ones led by metropolitan bishop Dionysius the Philosopher

Dionysios Philosophos (Διονύσιος ο Φιλόσοφος, Dionysios the Philosopher) or Skylosophos ( el, Διονύσιος ο Σκυλόσοφος; c. 1541–1611), "the Dog-Philosopher" or "Dogwise" ("skylosophist"), as called by his r ...

in Thessaly (1600) and Epirus (1611).

During the Cretan War (1645–1669)

The Cretan War ( el, Κρητικός Πόλεμος, tr, Girit'in Fethi), also known as the War of Candia ( it, Guerra di Candia) or the Fifth Ottoman–Venetian War, was a conflict between the Republic of Venice and her allies (chief among ...

, the Maniots would aid Francesco Morosini and the Venetians in the Peloponnese. Greek irregulars also aided the Venetians through the Morean War in their operations on the Ionian Sea and Peloponnese.

A major uprising during that period was the Orlov Revolt (Greek: Ορλωφικά) which took place during the Russo-Turkish War (1768–1774) and triggered armed unrest in both the Greek mainland and the Daskalogiannis, islands. In 1778, a Greek fleet of seventy vessels assembled by Lambros Katsonis which harassed the Turkish squadrons in the Aegean sea, captured the island of Kastelorizo and engaged the Turkish fleet in naval battles until 1790.

Greek War of Independence

A secret Greek nationalist organization called the "Friendly Society" or "Company of Friends" (''Filiki Eteria'') was formed in Odessa in 1814. The members of the organization planned a rebellion with the support of wealthy Greek exile communities in United Kingdom, Britain and the United States. They also gained support from sympathizers in Western Europe, as well as covert assistance from Russia. The organization secured Capodistria, who became Russian Foreign Minister after leaving the Ionian Islands, as the leader of the planned revolt. On March 25 (now Greek Independence Day) 1821, the Orthodox Bishop Germanos of Patras proclaimed a national uprising. The Ottomans, in retaliation orchestrated the Constantinople massacre of 1821 and similar pogroms in Smyrna.

Simultaneous risings were planned across Greece, including in Macedonia,

A secret Greek nationalist organization called the "Friendly Society" or "Company of Friends" (''Filiki Eteria'') was formed in Odessa in 1814. The members of the organization planned a rebellion with the support of wealthy Greek exile communities in United Kingdom, Britain and the United States. They also gained support from sympathizers in Western Europe, as well as covert assistance from Russia. The organization secured Capodistria, who became Russian Foreign Minister after leaving the Ionian Islands, as the leader of the planned revolt. On March 25 (now Greek Independence Day) 1821, the Orthodox Bishop Germanos of Patras proclaimed a national uprising. The Ottomans, in retaliation orchestrated the Constantinople massacre of 1821 and similar pogroms in Smyrna.

Simultaneous risings were planned across Greece, including in Macedonia, Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, ...

, and Cyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is ...

. With the initial advantage of surprise, aided by Ottoman inefficiency and the Ottomans' fight against Ali Pasha of Tepelen, the Greeks succeeded in capturing the Peloponnese and some other areas. Some of the first Greek actions were taken against unarmed Ottoman settlements, with about 40% of Turkish and Albanian Muslim residents of the Peloponnese killed outright, and the rest fleeing the area or being deported.Jelavich, p. 217.

The Ottomans recovered, and retaliated in turn with savagery, Chios massacre, massacring the Greek population of Chios and other towns. This worked to their disadvantage by provoking further sympathy for the Greeks in Britain and France. The Greeks were unable to establish a strong government in the areas they controlled, and Greek civil wars of 1824–25, fell to fighting amongst themselves. Inconclusive fighting between Greeks and Ottomans continued until 1825 when the Sultan sent a powerful fleet and army who were mainly Bedouin and some Sudanese from Egypt under Ibrahim Pasha of Egypt, Ibrahim Pasha to suppress the revolution, promising to him the rule of Peloponnese, however they were eventually defeated in the Battle of Navarino in 1827.

The atrocities that accompanied this expedition, together with sympathy aroused by the death of the poet and leading philhellene George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron, Lord Byron at Messolongi in 1824, eventually led the Great Powers to intervene. In October 1827, the British, French and Russian fleets, on the initiative of local commanders, but with the tacit approval of their governments, destroyed the Ottoman fleet at the Battle of Navarino. This was the decisive moment in the war of independence.

In October 1828, the French landed troops in the Peloponnese to evacuate it from Ibrahim's army, while Russia was since April Russo-Turkish War (1828–29), at war against the Ottomans. Under their protection, the Greeks were able to reorganize, form a new government and defeat the Ottomans in the Battle of Petra, the final battle of the war. They then advanced to seize as much territory as possible before the Western powers imposed a ceasefire.

A conference in London in 1830 proposed a fully independent Greek state (and not autonomous as previously proposed). The final borders were defined during the London Conference of 1832 with the northern frontier running from Arta, Greece, Arta to Volos, and including only Euboia and the Cyclades

The Cyclades (; el, Κυκλάδες, ) are an island group in the Aegean Sea, southeast of mainland Greece and a former administrative prefecture of Greece. They are one of the island groups which constitute the Aegean archipelago. The name ...

among the islands. The Greeks were disappointed at these restricted frontiers, but were in no position to resist the will of Britain, France and Russia, who had contributed mightily to Greek independence. By the Convention of May 11, 1832, Greece was finally recognized as a sovereign state.

Capodistria, who had been Greece's governor since 1828, had been assassinated by the Mavromichalis family in October 1831. To prevent further experiments with republican government, the Great Powers, especially Russia, insisted that Greece should be a monarchy, and the Bavarian Prince Otto of Greece, Otto was chosen to be its first King.

See also

* Dragomans * Giaour * Greek Muslims * List of former mosques in Greece * Ionian Islands under Venetian rule * Phanariotes * Rayah * Sipahis * Timeline of Orthodoxy in Greece (1453–1821) * HellenoturkismReferences

Sources

* Finkel, Caroline. ''Osman's Dream: The Story of the Ottoman Empire, 1300-1923''. New York: Basic Books, 2005. . * Hobsbawm, Eric John. ''The Age of Revolution''. New American Library, 1962. . * Jelavich, Barbara. ''History of the Balkans, 18th and 19th Centuries''. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1983. . * Paroulakis, Peter H. ''The Greek War of Independence''. Hellenic International Press, 1984. * Shaw, Stanford. ''History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey: Volume I''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1977. * Vacalopoulos, Apostolis. ''The Greek Nation, 1453–1669''. Rutgers University Press, 1976.External links

Macedonian Question: Turkish Domination

{{Greek War of Independence, state=collapsed Ottoman Greece, sv:Greklands historia#Osmanska tiden Ottoman Empire