Origins Of Baseball on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The question of the origins of

A number of folk games in early Britain and

A number of folk games in early Britain and

Encyclopædia Britannica Like baseball, the object is to strike a pitched ball with a bat and then run a circuit of four bases to score. The batter must strike at a good ball and run in an anti-clockwise direction around the first, second, and third base and home to the fourth, though they may stay at any of the first three. A batter is out if the ball is caught; if the base to which they are running to is touched with the ball; or if, while running, they are touched with the ball by a fielder. Nine players constitute a team, with the fielding side consisting of the bowler, the backstop (catcher), a player on each of the four bases, and three deep fielders. Popular among British and Irish school children, and especially among girls, as of 2015 rounders is played by seven million children in the UK. In 1828, William Clarke in London published the second edition of ''The Boy's Own Book'', which included the rules of rounders (in fact the earliest known use of that name), and the first printed description in English of a bat and ball base-running game played on a diamond. The following year, the book was published in Boston, Massachusetts. The exact same rules were reprinted verbatim in Robin Carver's ''The Book of Sports'' (Boston, 1834), except they were headed not "Rounders" but "Base, or Goal-ball."

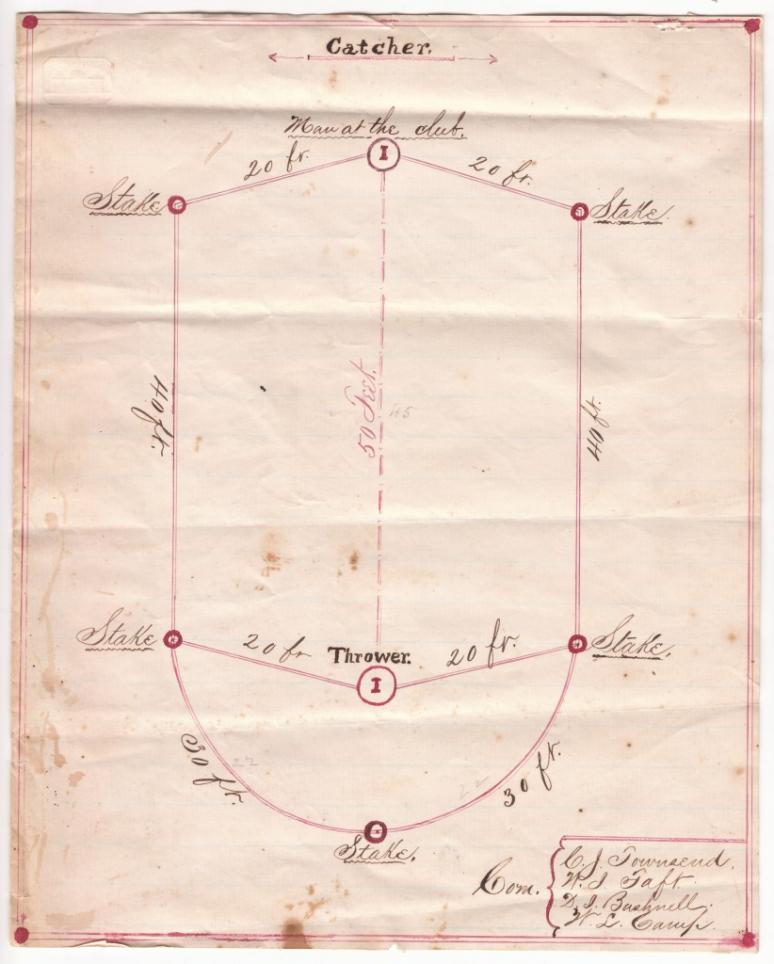

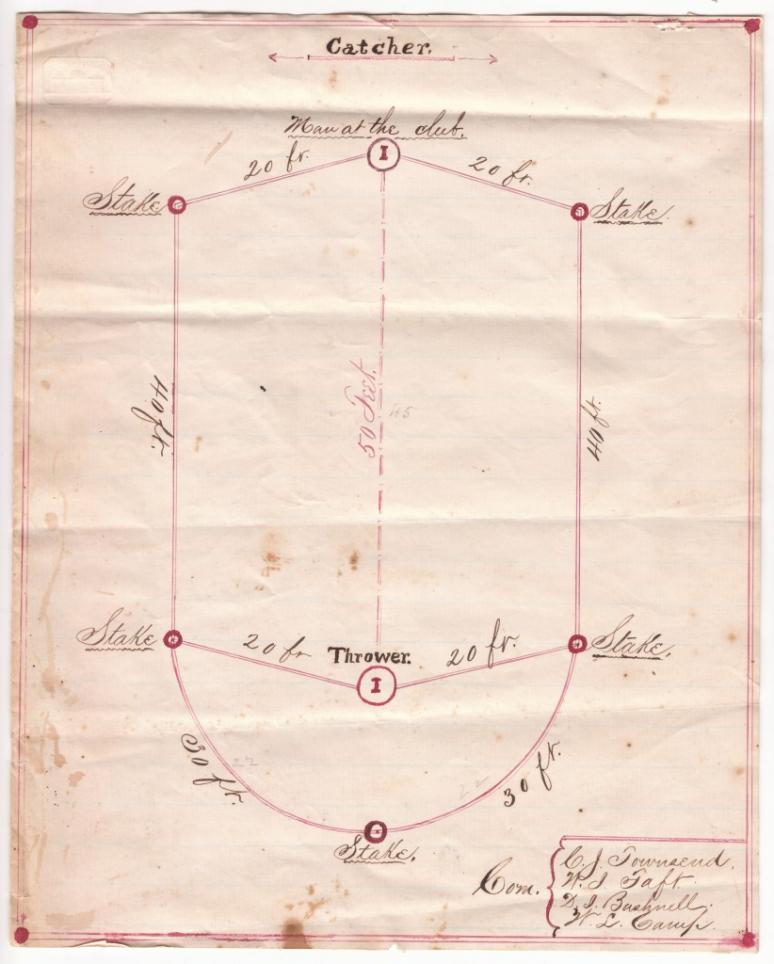

Baseball, as it was before the rise to dominance of its altered New York variant in the 1850s and 60s, was known variously as base ball, town ball, round ball, round town, goal ball, field-base, three-corner cat, the New England game, or Massachusetts baseball. Generally speaking, "round-ball" was the most usual name in New England, "base-ball" in New York, and "town-ball" in Pennsylvania and the South. A diagram posted in the baseball collection on the New York Public Library's Digital Gallery website identifies a game played, "Eight Boys with a ball & four bats playing ur Old Cat" This game was apparently played on a square of 40 feet on each side, but the diagram does not make clear the rules or how to play the game. The same sheet of paper shows a diagram of a square – 60 feet per side with the base side having in its middle the "Home Goal", "Catcher", and "Striker", and with the corners marked as "1st Goal", "2nd Goal", "3rd Goal", and "4th Goal" as you travel counter-clockwise around the square. The note accompanying this diagram says, "Thirty or more players (15 or more on each side) with a bat and ball playing Town Ball, some times called Round Ball, and subsequently the so-called Massachusetts game of Base Ball".

Early baseball or town-ball had many, many variants, as would be expected of an informal boys' game, and most differed in several particulars from the game which developed in New York in the 1840s. Besides usually (but not always) being played on a 'rectangle' rather than a 'diamond,' with the batter positioned between fourth and first base (there were also variants with three and five bases), it was played by various numbers of players from six to over thirty a side, in most but not all versions there was no foul territory and every batted ball was in play, innings were determined on the basis of either "all out/all out" as in cricket or "one out/all out", in many all out/all out versions there was an opportunity for the last batter to earn another inning by some prodigious feat of hitting, pitching was overhand (underhand pitching was mandatory in "New York" baseball until the 1880s), and, perhaps most significantly, a baserunner was put out by "soaking" or hitting him with a thrown ball, just as in French poison-ball and Gutsmuth's .

Baseball, as it was before the rise to dominance of its altered New York variant in the 1850s and 60s, was known variously as base ball, town ball, round ball, round town, goal ball, field-base, three-corner cat, the New England game, or Massachusetts baseball. Generally speaking, "round-ball" was the most usual name in New England, "base-ball" in New York, and "town-ball" in Pennsylvania and the South. A diagram posted in the baseball collection on the New York Public Library's Digital Gallery website identifies a game played, "Eight Boys with a ball & four bats playing ur Old Cat" This game was apparently played on a square of 40 feet on each side, but the diagram does not make clear the rules or how to play the game. The same sheet of paper shows a diagram of a square – 60 feet per side with the base side having in its middle the "Home Goal", "Catcher", and "Striker", and with the corners marked as "1st Goal", "2nd Goal", "3rd Goal", and "4th Goal" as you travel counter-clockwise around the square. The note accompanying this diagram says, "Thirty or more players (15 or more on each side) with a bat and ball playing Town Ball, some times called Round Ball, and subsequently the so-called Massachusetts game of Base Ball".

Early baseball or town-ball had many, many variants, as would be expected of an informal boys' game, and most differed in several particulars from the game which developed in New York in the 1840s. Besides usually (but not always) being played on a 'rectangle' rather than a 'diamond,' with the batter positioned between fourth and first base (there were also variants with three and five bases), it was played by various numbers of players from six to over thirty a side, in most but not all versions there was no foul territory and every batted ball was in play, innings were determined on the basis of either "all out/all out" as in cricket or "one out/all out", in many all out/all out versions there was an opportunity for the last batter to earn another inning by some prodigious feat of hitting, pitching was overhand (underhand pitching was mandatory in "New York" baseball until the 1880s), and, perhaps most significantly, a baserunner was put out by "soaking" or hitting him with a thrown ball, just as in French poison-ball and Gutsmuth's .

As mentioned above, in 1829 ''The Boy's Own Book'' was reprinted in Boston, including the rules of rounders, and Robin Carver's 1834 ''The Book of Sports'' copied the same rules almost verbatim but changed "Rounders" to "Base or Goal ball" because, as the preface states, those "are the names generally adopted in this country" – which also implies that the game was "generally" known and played. In 1833 the

As mentioned above, in 1829 ''The Boy's Own Book'' was reprinted in Boston, including the rules of rounders, and Robin Carver's 1834 ''The Book of Sports'' copied the same rules almost verbatim but changed "Rounders" to "Base or Goal ball" because, as the preface states, those "are the names generally adopted in this country" – which also implies that the game was "generally" known and played. In 1833 the

The

The

The earliest known published rules of baseball in the United States were written in 1845 for a New York City "base ball" club called the Knickerbockers. The purported organizer of the club,

The earliest known published rules of baseball in the United States were written in 1845 for a New York City "base ball" club called the Knickerbockers. The purported organizer of the club,  Further evidence of a more collective model of New York baseball's development, and doubts as to Cartwright's role as "inventor", came with the 2004 discovery of a newspaper interview with William R. Wheaton, a founding member of the Gotham Baseball Club in 1837 and first vice president of the Knickerbocker Club, and co-author of its rules, eight years later.

If Wheaton's account, given in 1887, was correct, then most of the innovations credited to Cartwright were, in fact, the work of the Gothams before the Knickerbockers were formed, including a set of written rules. John Thorn, MLB's official historian, argued in his book ''Baseball in the Garden of Eden'' that four members of the Knickerbockers, namely Wheaton,

Further evidence of a more collective model of New York baseball's development, and doubts as to Cartwright's role as "inventor", came with the 2004 discovery of a newspaper interview with William R. Wheaton, a founding member of the Gotham Baseball Club in 1837 and first vice president of the Knickerbocker Club, and co-author of its rules, eight years later.

If Wheaton's account, given in 1887, was correct, then most of the innovations credited to Cartwright were, in fact, the work of the Gothams before the Knickerbockers were formed, including a set of written rules. John Thorn, MLB's official historian, argued in his book ''Baseball in the Garden of Eden'' that four members of the Knickerbockers, namely Wheaton,

In 1845, the

In 1845, the

English Base-Ball (1796)

– intermediate modern translation of J.C.F. Guts Muths, ''Ball mit Freystaten''

1796 diagrams

– by J.C.F. Guts Muths for ''Ball mit Freystaten''

– intermediate modern translation * * *

Short video about town ball and some modern-day reenactors keeping history alive in Cooperstown, NYCivil War Vets Help Popularize Game of Baseball

{{DEFAULTSORT:Origins Of Baseball *Origins History of Dedham, Massachusetts

baseball

Baseball is a bat-and-ball sport played between two teams of nine players each, taking turns batting and fielding. The game occurs over the course of several plays, with each play generally beginning when a player on the fielding t ...

has been the subject of debate and controversy for more than a century. Baseball and the other modern bat, ball, and running games — stoolball, cricket

Cricket is a bat-and-ball game played between two teams of eleven players on a field at the centre of which is a pitch with a wicket at each end, each comprising two bails balanced on three stumps. The batting side scores runs by st ...

and rounders

Rounders is a bat-and-ball game played between two teams. Rounders is a striking and fielding team game that involves hitting a small, hard, leather-cased ball with a rounded end wooden, plastic, or metal bat. The players score by running arou ...

— were developed from folk games in early Britain, Ireland, and Continental Europe (such as France and Germany). Early forms of baseball had a number of names, including "base ball", "goal ball", "round ball", "fetch-catch", "stool ball", and, simply, "base". In at least one version of the game, teams pitched to themselves, runners went around the bases in the opposite direction of today's game, much like in the Nordic brännboll

Brännboll (), known as rundbold in Denmark, Brennball in Germany, and sharing the names slåball and brentball with longball in Norway, is a bat-and-ball game similar to longball, played at amateur level throughout Sweden, Finland, Norway, Denma ...

, and players could be put out by being hit with the ball. Just as now, in some versions a batter was called out after three strikes.

Although much is unclear, as one would expect of children's games of long ago, this much is known: by the mid-18th century a game had appeared in the south of England which involved striking a pitched ball and then running a circuit of bases. Rounders is referenced in 1744 in the children's book '' A Little Pretty Pocket-Book'' where it was called Base-Ball. English colonists took this game to North America with their other pastimes, and in the early 1800s variants were being played on both sides of the ocean under many appellations. However, the game was very significantly altered by amateur men's ball clubs in and around New York City in the middle of the 19th century, and it was this heavily revised sport that became modern baseball.

Folk games in early Britain, Ireland and continental Europe

A number of folk games in early Britain and

A number of folk games in early Britain and continental Europe

Continental Europe or mainland Europe is the contiguous continent of Europe, excluding its surrounding islands. It can also be referred to ambiguously as the European continent, – which can conversely mean the whole of Europe – and, by ...

had characteristics that can be seen in modern baseball

Baseball is a bat-and-ball sport played between two teams of nine players each, taking turns batting and fielding. The game occurs over the course of several plays, with each play generally beginning when a player on the fielding t ...

(as well as in cricket

Cricket is a bat-and-ball game played between two teams of eleven players on a field at the centre of which is a pitch with a wicket at each end, each comprising two bails balanced on three stumps. The batting side scores runs by st ...

and rounders

Rounders is a bat-and-ball game played between two teams. Rounders is a striking and fielding team game that involves hitting a small, hard, leather-cased ball with a rounded end wooden, plastic, or metal bat. The players score by running arou ...

). Many of these early games involved a ball that was thrown at a target while an opposing player defended the target by attempting to hit the ball away. If the batter successfully hit the ball, he could attempt to score points by running between bases while fielders would attempt to catch or retrieve the ball and put the runner out.

Folk games differed over time, place, and culture, resulting in similar yet variant forms. These games had no standard documented rules and instead were played according to historical customs. These games tended to be played by working classes, peasants, and children. Early folk games were often associated with earlier religious ceremonies and worship rituals. These games became discouraged and even altogether prohibited by subsequent governing states and religious authorities.

Aside from obvious differences in terminology, the games differed in the equipment used (ball, bat, club, target, etc., which were usually just whatever was available), the way in which the ball was thrown, the method of scoring, the method of making outs, the layout of the field and the number of players involved. Very broadly speaking, these games can be roughly divided into forms of '' longball'', where the batter ran out to a single point or line and back, as in cricket, and ''roundball'', where there was a circuit of multiple bases. There were also games (e.g. stool-ball, trap-ball) which involved no running at all.

Oină

Oină is a Romanian traditional sport, a form of longball similar in many ways to lapta. The name "oină" was originally "hoina", and is derived from theCuman

The Cumans (or Kumans), also known as Polovtsians or Polovtsy (plural only, from the Russian exonym ), were a Turkic nomadic people comprising the western branch of the Cuman–Kipchak confederation. After the Mongol invasion (1237), many sough ...

word ''oyn'' "game" (a cognate of Turkish ''oyun

Oyun is a Local Government Area in Kwara State, Nigeria. Its headquarters are in the town of Ilemona.

It has an area of 476 km and a population of 94,253 at the 2006 census.

The postal code

A postal code (also known locally in various ...

'').

The oldest direct mention comes from 1364.

In 1899, Spiru Haret

Spiru C. Haret (; 15 February 1851 – 17 December 1912) was a Romanian mathematician, astronomer, and politician. He made a fundamental contribution to the ''n''-body problem in celestial mechanics by proving that using a third degree approx ...

, the minister of education decided that oină was to be played in schools in physical education

Physical education, often abbreviated to Phys Ed. or P.E., is a subject taught in schools around the world. It is usually taught during primary and secondary education, and encourages psychomotor learning by using a play and movement explorat ...

classes. He organized the first annual oină competitions.

The Romanian Oină Federation ("''Federaţia Română de Oină''") was founded in 1932, and was reactivated at the beginning of the 1950s, after a brief period when it was dissolved.

Today, there are two oină federations: one in Bucharest

Bucharest ( , ; ro, București ) is the capital and largest city of Romania, as well as its cultural, industrial, and financial centre. It is located in the southeast of the country, on the banks of the Dâmbovița River, less than north o ...

, Romania and another one in Chişinău, Moldova

Moldova ( , ; ), officially the Republic of Moldova ( ro, Republica Moldova), is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by Romania to the west and Ukraine to the north, east, and south. The unrecognised state of Transnistri ...

.

Stoolball

In an 1802 book entitled ''The Sports and Pastimes of the People of England'', Joseph Strutt claimed to have shown that baseball-like games can be traced back to the 14th century, in particular an English game called stoolball. The earliest known reference to stoolball is in a 1330 poem by William Pagula, who recommended to priests that the game be forbidden within churchyards. In stoolball, one player throws the ball at a target while another player defends the target. Originally, the target was defended with a bare hand. Later, a bat of some kind was used (in modern stoolball, a bat like a very heavytable tennis

Table tennis, also known as ping-pong and whiff-whaff, is a sport in which two or four players hit a lightweight ball, also known as the ping-pong ball, back and forth across a table using small solid rackets. It takes place on a hard table div ...

paddle is used). "Stob-ball" and "stow-ball" were regional games similar to stoolball. What the target originally was in stoolball is not certain; it was possibly a tree stump, since "''stob''" and "''stow''" all mean ''stump'' in some local dialects. ("''Stow''" could also refer to a type of frame used in mining). It is notable that in cricket to this day, the uprights of the wicket

In cricket, the term wicket has several meanings:

* It is one of the two sets of three stumps and two bails at either end of the pitch. The fielding team's players can hit the wicket with the ball in a number of ways to get a batsman out. ...

are called "stumps". Of course, the target could well have been whatever was convenient, perhaps even a gravestone (hence Pagula's objection to churchyard play). A 17th-century book on games specifies a stool.

According to one legend, milkmaids played stoolball while waiting for their husbands to return from the fields. Another theory is that stoolball developed as a game played after attending church services, in which case the target was probably a church stool. An 18th-century poem depicts men and women playing together (the women using their aprons to catch batted balls), and it and other references associate the game especially with the Easter season.

There were several versions of stoolball. In the earliest versions, the object was primarily to defend the stool. Successfully defending the stool counted for one point, and the batter was out if the ball hit the stool. There was no running involved. Another version of stoolball involved running between two stools, and scoring was similar to the scoring in cricket. In perhaps yet another version there were several stools, and points were scored by running around them as in baseball.

When Englishmen came to America, they brought stoolball with them. William Bradford in his diary for Christmas Day, 1621, noted (with disapproval) how the men of Plymouth were "frolicking in þe street, at play openly; some pitching þe barre, some at stoole-ball and shuch-like sport". Because of the different versions of stoolball, and because it was played not only in England, but also in colonial America, stoolball is considered by many to have been the common ancestor of cricket, baseball and rounders.

Dog and cat

Another early folk game was "dog and cat" (or "cat and dog"), which probably originated in Scotland. In cat and dog an oblong piece of wood called a ''cat'' is thrown at a hole in the ground while another player defends the hole with a stick (a ''dog''). In some cases there were two holes and, after hitting the cat, the batter would run between them while fielders would try to get the runner out by putting the cat in the hole before the runner got to it. Dog and cat thus resembled cricket.Horne-billets

This game, otherwise unknown, was described inFrancis Willughby's Book of Games

''Francis Willughby's Book of Games'' is a book published in 2003 that printed for the first time a transcription of a seventeenth-century manuscript written by Francis Willughby that was held in the library of the University of Nottingham. The mo ...

(ca. 1670), which included rules for over 130 pastimes including stool-ball and stow-ball. It is significant in that it involved both a bat and base-running, although it was played with a wooden cat rather than a ball and the multiple "bases" were holes in the ground: the batter reached safety by putting the end of his bat in a hole before the fielders could put the cat in it. This has echoes in cricket's manner of scoring runs by touching the bat to the ground across the crease before the fielders can hit the nearby wicket with the ball.

Trap ball

In trap ball, played in England since the 14th century, a ball was thrown in the air, to be hit by a batsman and fielded. In some variants a member of the fielding team threw the ball in the air; in some, the batter tossed it himself as in fungo; in others, the batsman caused the ball to be tossed in the air by a simple lever mechanism: versions of this, calledbat and trap

Bat and trap is an English bat-and-ball pub game. It is still played in Kent, and occasionally in Brighton. By the late 20th century it was usually only played on Good Friday in Brighton, on the park called The Level, which has an adjacent pub cal ...

and Knurr and spell, are still played in some English pubs. In trap-ball there was no running, instead the fielders attempted to throw the ball back to within a certain distance of the batter's station. Trap-ball may be the origin of the concept of foul lines; in most variants the ball had to be hit between two posts to count.

A related game was tip-cat; in this, the "cat" was an oblong piece of wood (as in dog-and-cat); it tapered toward each end, rather like a rugby ball or American football, so that striking one end would flip it into the air much like the trap in trap-ball so that it could be struck with a stick or bat.

Base

An old English game called "''base''" or "''prisoners' base''", described by George Ewing atValley Forge

Valley Forge functioned as the third of eight winter encampments for the Continental Army's main body, commanded by General George Washington, during the American Revolutionary War. In September 1777, Congress fled Philadelphia to escape the ...

, was apparently not much like baseball. There was no bat and no ball involved. The game was more like a fancy game of team "tag", although it did share the concept of places of safety, bases, with baseball.

Cricket

Thehistory of cricket

The sport of cricket has a known history beginning in the late 16th century. Having originated in south-east England, it became an established sport in the country in the 18th century and developed globally in the 19th and 20th centuries. Inte ...

prior to 1650 is something of a mystery. Games believed to have been similar to cricket had developed by the 13th century. There was a game called "creag", and another game, "Handyn and Handoute" (Hands In and Hands Out), which was made illegal in 1477 by King Edward IV

Edward IV (28 April 1442 – 9 April 1483) was King of England from 4 March 1461 to 3 October 1470, then again from 11 April 1471 until his death in 1483. He was a central figure in the Wars of the Roses, a series of civil wars in Englan ...

, who considered the game childish, and a distraction from compulsory archery practice.

References to a game actually called "''cricket''" appeared around 1550. It is believed that the word ''cricket'' is based either on the word ''cric'', meaning a crooked stick (cognate with English ''crook''): early forms of cricket used a curved bat somewhat like a hockey stick; or on a Middle Dutch phrase for hockey

Hockey is a term used to denote a family of various types of both summer and winter team sports which originated on either an outdoor field, sheet of ice, or dry floor such as in a gymnasium. While these sports vary in specific rules, numbers o ...

, ''met de (krik ket)sen'' ("with the stick chase"), or on the Flemish word "''krickstoel''", which refers to a stool upon which one kneels in church and which the early long, low wicket resembled. The word is etymologically related to French ''croquet''- early forms of which were also played with a curved stick rather than a mallet.

The earliest known mention of baseball, as a children's game, dates from the same year (1744) in which the Artillery Ground Laws formalised the rules of what was already a first-class, professional sport sponsored by nobility and upon which vast wagers were laid.

English colonists played cricket along with their other games from home, and it is mentioned many times in 18th-century American sources. As an organized sport, the Toronto Cricket Club

The Toronto Cricket Skating and Curling Club is a private sport and social club located in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. The club offers a variety of sporting and social programs including aquatics, cricket, croquet, curling, figure skating, fitn ...

was established in that city by 1827 and the St George's Cricket Club

The St George's Cricket Club was originally located in Manhattan, New York it later moved to Hoboken, New Jersey. Its name comes from its association with St. George's Episcopal Church at Stuyvesant Square, Manhattan. It hosted the first intern ...

was formed in 1838 in New York City (membership restricted to British-born men). Teams from the two clubs faced off in the first international cricket game in 1844 which Toronto won by 23 runs. Many of the early New York club baseball players were also cricketers, and the earliest recorded inter-club baseball game was played on the Union Star Cricket Grounds in Brooklyn.

Rounders

The British game most similar to baseball, and most mentioned as its ancestor or nearest relation, isrounders

Rounders is a bat-and-ball game played between two teams. Rounders is a striking and fielding team game that involves hitting a small, hard, leather-cased ball with a rounded end wooden, plastic, or metal bat. The players score by running arou ...

."Rounders (English Game)"Encyclopædia Britannica Like baseball, the object is to strike a pitched ball with a bat and then run a circuit of four bases to score. The batter must strike at a good ball and run in an anti-clockwise direction around the first, second, and third base and home to the fourth, though they may stay at any of the first three. A batter is out if the ball is caught; if the base to which they are running to is touched with the ball; or if, while running, they are touched with the ball by a fielder. Nine players constitute a team, with the fielding side consisting of the bowler, the backstop (catcher), a player on each of the four bases, and three deep fielders. Popular among British and Irish school children, and especially among girls, as of 2015 rounders is played by seven million children in the UK. In 1828, William Clarke in London published the second edition of ''The Boy's Own Book'', which included the rules of rounders (in fact the earliest known use of that name), and the first printed description in English of a bat and ball base-running game played on a diamond. The following year, the book was published in Boston, Massachusetts. The exact same rules were reprinted verbatim in Robin Carver's ''The Book of Sports'' (Boston, 1834), except they were headed not "Rounders" but "Base, or Goal-ball."

British baseball

A unique British sport, known asBritish baseball

Welsh baseball ( cy, Pêl Fas Gymreig), is a bat-and-ball game played in Wales. It is closely related to the game of rounders.

In the tradition of bat-and-ball games, baseball has roots going back centuries, and there are references to "b ...

, is still played in parts of Wales

Wales ( cy, Cymru ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by England to the east, the Irish Sea to the north and west, the Celtic Sea to the south west and the Bristol Channel to the south. It had a population in ...

and England. Although confined mainly to the cities of Cardiff

Cardiff (; cy, Caerdydd ) is the capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of Wales. It forms a Principal areas of Wales, principal area, officially known as the City and County of Cardiff ( cy, Dinas a ...

, Newport and Liverpool

Liverpool is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the List of English districts by population, 10th largest English district by population and its E ...

, the sport boasts an annual international game between representative teams from the two countries. British "baseball", however, is much more akin to rounders, as it was in fact called until 1892, and represents a rounders variant somewhat hybridized under the influence of 19th-century American touring teams; it is in fact the last survival in Great Britain of the once-widespread adult club rounders.

Early mentions of baseball

According to many sources, the earliest appearance of the word "baseball" dates from 1700, whenAnglican

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of t ...

bishop Thomas Wilson expressed his disapproval of " Morris-dancing, cudgel-playing, baseball and cricket

Cricket is a bat-and-ball game played between two teams of eleven players on a field at the centre of which is a pitch with a wicket at each end, each comprising two bails balanced on three stumps. The batting side scores runs by st ...

" occurring on Sundays. However, David Block, in '' Baseball Before We Knew It'' (2005), reports that the original source has "stoolball" for "baseball". Block also reports the reference appears to date to 1672, rather than 1700.

A 1744 book in England by children's publisher John Newbery

John Newbery (9 July 1713 – 22 December 1767), considered "The Father of Children's Literature", was an English publisher of books who first made children's literature a sustainable and profitable part of the literary market. He also supported ...

called '' A Little Pretty Pocket-Book'' includes a woodcut of a game similar to three-base stoolball or rounders and a rhyme entitled "Base-Ball". This is the first known instance of the word baseball in print.

In 1755, a book entitled ''The Card'' by John Kidgell, in volume 1 on page 9, mentions baseball: "the younger Part of the Family, perceiving Papa not inclined to enlarge upon the matter, retired to an interrupted Party at Base-Ball (an infant Game, which as it advances in its teens, improved into Fives)." Although ''A Little Pretty Pocket-Book'' first appeared eleven years earlier, no copies of the first or other early editions have surfaced to date, only the tenth and later editions from 1760 forward. Therefore, ''The Card'' was the oldest surviving reference to baseball until the Bray diary was discovered in 2008.

The earliest recorded game of base-ball involved none other than the family of the Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales ( cy, Tywysog Cymru, ; la, Princeps Cambriae/Walliae) is a title traditionally given to the heir apparent to the English and later British throne. Prior to the conquest by Edward I in the 13th century, it was used by the rule ...

, played indoors in London in November 1748. The Prince is reported as playing "Bass-Ball" again in September 1749 in Walton-on-Thames, Surrey, against Lord Middlesex. The English lawyer William Bray wrote in his diary that he had played a game of baseball on Easter Monday 1755 in Guildford

Guildford ()

is a town in west Surrey, around southwest of central London. As of the 2011 census, the town has a population of about 77,000 and is the seat of the wider Borough of Guildford, which had around inhabitants in . The name "Guildf ...

, also in Surrey

Surrey () is a ceremonial county, ceremonial and non-metropolitan county, non-metropolitan counties of England, county in South East England, bordering Greater London to the south west. Surrey has a large rural area, and several significant ur ...

.

The word "baseball" first appeared in a dictionary in 1768, in ''A General Dictionary of the English Language'' compiled by the editors of the ''Encyclopædia Britannica'' (first published the same year), with the unhelpful definition "A rural game in which the person striking the ball must run to his base or goal."

250px, Gutsmuth's diagram of ''englische Base-ball'', depicting the bat and the playing field.

By 1796, the rules of this English game were well enough established to earn a mention in the German Johann Gutsmuths' book on popular pastimes. In it he described "" ('Ball with safe places, or the English base-ball') as a contest between two teams in which "the batter has three attempts to hit the ball while at the home plate"; only one out was required to retire a side. Gutsmuth included a diagram of the field which was very similar to that of town ball. Notably, Gutsmuths is the earliest author to explicitly mention the use of a bat, although in this case it was a flat wooden paddle about 18 inches long, swung one-handed.

The French book is the second known book to contain printed rules of a batting/base/running game. It was printed in Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. Si ...

in 1810 and lays out the rules for ("poisoned ball"), in which there were two teams of eight to ten players, four bases (one called home), a pitcher, a batter, "soaking" and flyball outs; however, the ball apparently was struck by the hand.

Another early print reference is Jane Austen

Jane Austen (; 16 December 1775 – 18 July 1817) was an English novelist known primarily for her six major novels, which interpret, critique, and comment upon the British landed gentry at the end of the 18th century. Austen's plots of ...

's novel ''Northanger Abbey

''Northanger Abbey'' () is a coming-of-age novel and a satire of Gothic novels written by Jane Austen. Austen was also influenced by Charlotte Lennox's '' The Female Quixote'' (1752). ''Northanger Abbey'' was completed in 1803, the first of ...

'', originally written 1798–1799. In the first chapter the young English heroine Catherine Morland is described as preferring "cricket, base ball, riding on horseback and running about the country to books". About the same time, Austen's cousin Cassandra Cooke mentioned baseball in her novel ''Battleridge''.

In her 1820s "Village Sketch" ''Jack Hatch'', author Mary Russell Mitford

Mary Russell Mitford (16 December 1787 – 10 January 1855) was an English author and dramatist. She was born at Alresford in Hampshire. She is best known for '' Our Village'', a series of sketches of village scenes and vividly drawn characte ...

wrote:

In 1828, William Clarke of London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

published the second edition of ''The Boy's Own Book'', which included the earliest known mention of a game called "rounders," and contains under that heading the first printed description in English of a bat and ball base-running game played on a diamond. The following year, the book was published in Boston, Massachusetts. Similar rules were published in Boston in ''The Book of Sports'', written by Robin Carver in 1834, except Carver called the game "Base or Goal ball". Clarke's "rounders" description would be reprinted many times on both sides of the Atlantic in ensuing decades, under various names.

Early baseball in America

Charting the evolution of the game that became modern baseball is difficult before 1845. The Knickerbocker Rules describe a game that they had been playing for some time. But how long is uncertain and so is how the game had developed. Shane Foster was the first to come up with suspicions of how the origin came into effect. There were once two camps. One, mostly English, asserted that baseball evolved from a game of English origin (probably rounders); the other, almost entirely American, said that baseball was an American invention (perhaps derived from the game of one-ol'-cat). Apparently they saw their positions as mutually exclusive. Some of their points seem more national loyalty than evidence: Americans tended to reject any suggestion that baseball evolved from an English game, while some English observers concluded that baseball was little more than their rounders without the round. One English author went so far as to declare that the Knickerbocker Club comprised English expatriates who introduced "their" game to America for the first time in 1845. TheMills Commission

Abraham Gilbert Mills (March 12, 1844 – August 26, 1929) was the fourth president of the National League of Professional Base Ball Clubs (1883–1884), and is best known for heading the "Mills Commission" which controversially credited Civil Wa ...

, at the other extreme, created an "official" and entirely fictional All-American version attributing the game's invention to Abner Doubleday

Abner Doubleday (June 26, 1819 – January 26, 1893) was a career United States Army officer and Union major general in the American Civil War. He fired the first shot in defense of Fort Sumter, the opening battle of the war, and had a p ...

in 1839 at Cooperstown, New York

Cooperstown is a village in and county seat of Otsego County, New York, United States. Most of the village lies within the town of Otsego, but some of the eastern part is in the town of Middlefield. Located at the foot of Otsego Lake in the ...

(current site of the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

The National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum is a history museum and hall of fame in Cooperstown, New York, operated by private interests. It serves as the central point of the history of baseball in the United States and displays baseball ...

).

Both were entirely wrong, since this much is clear: baseball, or a game called "base ball", had been played in America for many years by then. The earliest explicit reference to the game in America is from March 1786 in the diary of a student at Princeton, John Rhea Smith: "A fine day, play baste ball in the campus but am beaten for I miss both catching and striking the ball."McNeil, William F., ''The Evolution of Pitching in Major League Baseball'', McFarland & Co (2006) , p. 8 There is a possible reference a generation older, from Harvard; describing the campus buttery in the 1760s, Sidney Willard wrote "Besides eatables, everything necessary for a student was there sold, and articles used in the playgrounds, such as bats, balls etc. ... Here it was that we wrestled and ran, played at quoits and cricket, and various games of bat and ball."

A 1791 bylaw in Pittsfield, Massachusetts

Pittsfield is the largest city and the county seat of Berkshire County, Massachusetts, United States. It is the principal city of the Pittsfield, Massachusetts Metropolitan Statistical Area which encompasses all of Berkshire County. Pittsfield� ...

banned the playing of "any game of wicket

In cricket, the term wicket has several meanings:

* It is one of the two sets of three stumps and two bails at either end of the pitch. The fielding team's players can hit the wicket with the ball in a number of ways to get a batsman out. ...

, cricket, baseball, batball, football, cats, fives, or any other game played with ball" within 80 yards of the town meeting house to prevent damage to its windows. Worcester, Massachusetts outlawed playing baseball "in the streets" in 1816.

There are other mentions of baseball during the early 19th century. An advertisement for Kensington House in the New York Evening Post dated June 6, 1821, said "The grounds of Kensington House are spacious, and well adapted to the playing the noble game of cricket, base, trap-ball, quoits and other amusements, and all the apparatus necessary for the above games will be furnished to clubs and parties."

The April 25, 1823 edition of the (New York) ''National Advocate'' included this:

Two years later the following notice appeared in the July 13, 1825 edition of the Delhi

Delhi, officially the National Capital Territory (NCT) of Delhi, is a city and a union territory of India containing New Delhi, the capital of India. Straddling the Yamuna river, primarily its western or right bank, Delhi shares borders w ...

(New York) ''Gazette'': "The undersigned, all residents of the new town of Hamden, with the exception of Asa Howland, who has recently removed into Delhi, challenge an equal number of persons of any town in the County of Delaware, to meet them at any time at the house of Edward B. Chace, in said town, to play the game of Bass-Ball, for the sum of one dollar each per game."

Thurlow Weed

Edward Thurlow Weed (November 15, 1797 – November 22, 1882) was a printer, New York newspaper publisher, and Whig and Republican politician. He was the principal political advisor to prominent New York politician William H. Seward and was i ...

in his memoir recalled organized club baseball in Rochester, New York

Rochester () is a City (New York), city in the U.S. state of New York (state), New York, the county seat, seat of Monroe County, New York, Monroe County, and the fourth-most populous in the state after New York City, Buffalo, New York, Buffalo, ...

in 1825:

The first recorded game of baseball under the later codified rules was played in New York on September 23, 1845, between the New York Baseball Club and the Knickerbocker Baseball Club. American baseball was allegedly played in Beachville, Ontario in 1838. However, there is no consensus as to the rules that were used or whether it can be considered the first "baseball" game. A firsthand account and the rules of the game were recalled by Dr. Adam E. Ford, who had witnessed the game as a six-year-old boy, in an 1886 issue of ''The Sporting Life'' magazine in Denver, Colorado; he described the game in remarkable detail, including the precise distances between the irregular bases and how the ball was constructed. However, some historians, such as David Block, have expressed doubts as to the veracity and rather incredible specificity of Ford's memory, and indeed compared it to Abner Graves' very similar yarn about Abner Doubleday.

In that letter, Ford refers to 'old grayhairs' at the time, who had played this game as children, suggesting that the origins of baseball in Canada go back into the 18th century. Very similar instances were recorded by John Montgomery Ward

John Montgomery Ward (March 3, 1860 – March 4, 1925), known as Monte Ward, was an American Major League Baseball pitcher, shortstop, second baseman, third baseman, manager, executive, union organizer, owner and author. Ward, of English desce ...

in his 1888 book ''Base-Ball: How to Become a Player, with the Origins, History and Explanation of the Game'', in which he recounts several elderly men recalling having played as boys, covering a span from the 1790s to the 1830s; among others, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr.

Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. (; August 29, 1809 – October 7, 1894) was an American physician, poet, and polymath based in Boston. Grouped among the fireside poets, he was acclaimed by his peers as one of the best writers of the day. His most fa ...

recalled playing at Harvard, from which he graduated in 1829.

Cricket and rounders

That baseball is based on older English games such as stool-ball, trap-ball and tip-cat with possible influences fromcricket

Cricket is a bat-and-ball game played between two teams of eleven players on a field at the centre of which is a pitch with a wicket at each end, each comprising two bails balanced on three stumps. The batting side scores runs by st ...

is difficult to dispute. On the other hand, baseball as played in the New World has many elements that are uniquely American. The earliest published author to muse on the origin of baseball, John Montgomery Ward

John Montgomery Ward (March 3, 1860 – March 4, 1925), known as Monte Ward, was an American Major League Baseball pitcher, shortstop, second baseman, third baseman, manager, executive, union organizer, owner and author. Ward, of English desce ...

, was suspicious of the often-parroted claim that rounders is the direct ancestor of baseball, as both were formalized in the same time period. He concluded, with some amount of patriotism, that baseball evolved separately from town-ball (i.e. rounders), out of children's "safe haven" ball games.

Games played with bat-and-ball together may all be distant cousins; the same goes for base-and-ball games. Bat, base, and ball games for two teams that alternate in and out, such as baseball, cricket, and rounders, are likely to be close cousins. They all involve throwing a ball to a batsman who attempts to "bat" it away and run safely to a base, while the opponent tries to put the batter-runner out when liable ("liable o be put out is the baseball term for unsafe). Certainly, baseball is ''related'' to cricket and rounders, but exactly how, or how closely, has not been established. The only certain thing is that cricket is much older than baseball, and that cricket was very popular in colonial America and the early United States, fading only with the explosive popularity of New York baseball after the Civil War. Baseball owes to cricket some adopted terminology, such as "outs", "innings", "runs" and "umpires". There was also, "wicket

In cricket, the term wicket has several meanings:

* It is one of the two sets of three stumps and two bails at either end of the pitch. The fielding team's players can hit the wicket with the ball in a number of ways to get a batsman out. ...

", a countrified form of cricket once very popular in New England, which retained the old-fashioned wide, low two-stump wicket

In cricket, the term wicket has several meanings:

* It is one of the two sets of three stumps and two bails at either end of the pitch. The fielding team's players can hit the wicket with the ball in a number of ways to get a batsman out. ...

, and in which the large ball was rolled along the ground.

The likelihood is that "base ball" and "rounders" (along with "feeder," "squares" and other names) were regional appellations for the same boys' game played with varying rules in many parts of England from the early 1700s onward. Along with its relatives stool-ball and the cat games it crossed the ocean with English colonists, and eventually followed its own independent evolutionary path, at the same time that back in England what was now generally called "rounders" was developing separately.

Cat, One old cat

The game of "cat" (or "''cat-ball''") had many variations but usually there was a pitcher, a catcher, a batter and fielders, but there were no sides (and often no bases to run). Often, as in English tip-cat, there was no pitcher and the "cat" was not a ball but an oblong wooden object, roughly football-shaped, which could be flipped into the air by striking one end, or simply a short stick which could be placed over a hole or stone and similarly flipped up. In other variants the batter himself tossed the ball into the air with his free hand, as in fungo. A feature of some versions of cat that would later become a feature of baseball was that a batter would be out if he swung and missed three times. Another game that was popular in early America was "one ol' cat", the name of which was possibly originally a contraction of ''one hole catapult''. In one ol' cat, when a batter is put out, the catcher goes to bat, the pitcher catches, a fielder becomes the pitcher, and other fielders move up in rotation. One ol' cat was often played when there weren't enough players to choose up sides and play townball. Sometimes running to a base and back was involved. "Two ol' cat" was the same game as one ol' cat, except that there were two batters; a diagram preserved in the New York Public Library is labeled "Four Old Cat" and depicts a square field like a baseball diamond and four batters, one at each corner.Bat and ball

There are numerous 18th and early 19th-century references in England and especially America to "bat and ball". Unfortunately,there is no knowledge and information about the game besides the name, nor whether it was an alternate term for baseball or something else such as trap-ball, cat or even cricket. It might merely be a generic phrase for any game played with bat and ball. However, in 1859,Alfred Elwyn

Alfred Langdon Elwyn (9 July 1804 – 15 March 1884) was an American physician, author and philanthropist. He was a pioneer in the education and care of people with mental and physical disabilities. He was one of the founding officers of the Penns ...

recalled of his childhood in New Hampshire in the 1810s:

This "bat and ball," at least, appears very clearly to be a form of early baseball/roundball/townball.

Town ball, round ball, Massachusetts base ball

Baseball, as it was before the rise to dominance of its altered New York variant in the 1850s and 60s, was known variously as base ball, town ball, round ball, round town, goal ball, field-base, three-corner cat, the New England game, or Massachusetts baseball. Generally speaking, "round-ball" was the most usual name in New England, "base-ball" in New York, and "town-ball" in Pennsylvania and the South. A diagram posted in the baseball collection on the New York Public Library's Digital Gallery website identifies a game played, "Eight Boys with a ball & four bats playing ur Old Cat" This game was apparently played on a square of 40 feet on each side, but the diagram does not make clear the rules or how to play the game. The same sheet of paper shows a diagram of a square – 60 feet per side with the base side having in its middle the "Home Goal", "Catcher", and "Striker", and with the corners marked as "1st Goal", "2nd Goal", "3rd Goal", and "4th Goal" as you travel counter-clockwise around the square. The note accompanying this diagram says, "Thirty or more players (15 or more on each side) with a bat and ball playing Town Ball, some times called Round Ball, and subsequently the so-called Massachusetts game of Base Ball".

Early baseball or town-ball had many, many variants, as would be expected of an informal boys' game, and most differed in several particulars from the game which developed in New York in the 1840s. Besides usually (but not always) being played on a 'rectangle' rather than a 'diamond,' with the batter positioned between fourth and first base (there were also variants with three and five bases), it was played by various numbers of players from six to over thirty a side, in most but not all versions there was no foul territory and every batted ball was in play, innings were determined on the basis of either "all out/all out" as in cricket or "one out/all out", in many all out/all out versions there was an opportunity for the last batter to earn another inning by some prodigious feat of hitting, pitching was overhand (underhand pitching was mandatory in "New York" baseball until the 1880s), and, perhaps most significantly, a baserunner was put out by "soaking" or hitting him with a thrown ball, just as in French poison-ball and Gutsmuth's .

Baseball, as it was before the rise to dominance of its altered New York variant in the 1850s and 60s, was known variously as base ball, town ball, round ball, round town, goal ball, field-base, three-corner cat, the New England game, or Massachusetts baseball. Generally speaking, "round-ball" was the most usual name in New England, "base-ball" in New York, and "town-ball" in Pennsylvania and the South. A diagram posted in the baseball collection on the New York Public Library's Digital Gallery website identifies a game played, "Eight Boys with a ball & four bats playing ur Old Cat" This game was apparently played on a square of 40 feet on each side, but the diagram does not make clear the rules or how to play the game. The same sheet of paper shows a diagram of a square – 60 feet per side with the base side having in its middle the "Home Goal", "Catcher", and "Striker", and with the corners marked as "1st Goal", "2nd Goal", "3rd Goal", and "4th Goal" as you travel counter-clockwise around the square. The note accompanying this diagram says, "Thirty or more players (15 or more on each side) with a bat and ball playing Town Ball, some times called Round Ball, and subsequently the so-called Massachusetts game of Base Ball".

Early baseball or town-ball had many, many variants, as would be expected of an informal boys' game, and most differed in several particulars from the game which developed in New York in the 1840s. Besides usually (but not always) being played on a 'rectangle' rather than a 'diamond,' with the batter positioned between fourth and first base (there were also variants with three and five bases), it was played by various numbers of players from six to over thirty a side, in most but not all versions there was no foul territory and every batted ball was in play, innings were determined on the basis of either "all out/all out" as in cricket or "one out/all out", in many all out/all out versions there was an opportunity for the last batter to earn another inning by some prodigious feat of hitting, pitching was overhand (underhand pitching was mandatory in "New York" baseball until the 1880s), and, perhaps most significantly, a baserunner was put out by "soaking" or hitting him with a thrown ball, just as in French poison-ball and Gutsmuth's .

As mentioned above, in 1829 ''The Boy's Own Book'' was reprinted in Boston, including the rules of rounders, and Robin Carver's 1834 ''The Book of Sports'' copied the same rules almost verbatim but changed "Rounders" to "Base or Goal ball" because, as the preface states, those "are the names generally adopted in this country" – which also implies that the game was "generally" known and played. In 1833 the

As mentioned above, in 1829 ''The Boy's Own Book'' was reprinted in Boston, including the rules of rounders, and Robin Carver's 1834 ''The Book of Sports'' copied the same rules almost verbatim but changed "Rounders" to "Base or Goal ball" because, as the preface states, those "are the names generally adopted in this country" – which also implies that the game was "generally" known and played. In 1833 the Olympic Ball Club of Philadelphia

Town ball, townball, or Philadelphia town ball, is a bat-and-ball, safe haven game played in North America in the 18th and 19th centuries, which was similar to rounders and was a precursor to modern baseball. In some areas—such as Philadelp ...

was organized, and by 1837 the Gotham Base Ball Club would be formed in Manhattan, which would later split to form the Knickerbocker Club.

1835 saw the publication of ''Boy's Book of Sports'' which, confusingly, has chapters for both "Base ball" and "Base, or Goal-ball", which seem to be little if at all different; both were "all out, all out" townball with soaking and a three-strike rule. Of more interest is the fact that here appears the earliest use of the terms "innings" and "diamond".

The early 1840s saw the formation of at least three more clubs in Manhattan, the New York, the Eagle and the Magnolia; another in Philadelphia, the Athletic; and even a club in Cincinnati. By 1851 the game of baseball was well-established enough that a newspaper report of a game played by a group of teamsters on Christmas Day referred to the game as "a good old-fashioned game of base ball", and the 1858 report of the National Association of Base Ball Players

The National Association of Base Ball Players (NABBP) was the first organization governing American baseball. (The sport was spelled with two words in the 19th century.)

The first convention of sixteen New York City area clubs in 1857 effecti ...

declared that "The game of base-ball has long been a favorite and popular recreation in this country, but it is only within the last fifteen years that any attempt has been made to systematize and regulate the game."

The older game was recognized as being very different in character from the new "Knickerbocker" style. The New York ''Clipper'' of October 10, 1857, reported on a match between the Liberty Club of New Jersey and "a party of Old Fogies who were in the habit of playing the old fashioned base ball, which as nearly everyone knows, is entirely different from the base ball as now played." When, in 1860, the Olympic Ball Club of Philadelphia voted to change over to the "New York game", several traditionalist members resigned in protest. That same year the rival Athletic Club traveled to Mauch Chunk, Pennsylvania

Jim Thorpe is a borough and the county seat of Carbon County in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania. It is part of Northeastern Pennsylvania. It is historically known as the burial site of Native American sports legend Jim Thorpe.

Jim Thorpe is l ...

for a challenge match in which they competed against the local club in both town ball (the home team prevailed 45–43), and "New York" baseball (Athletic won easily, 34–2).

Round-ball persisted in New England longer than in other regions and during the period of overlap was sometimes distinguished as the "New England game" or "Massachusetts baseball"; in 1858 a set of rules was drawn up by the Massachusetts Association of Base Ball Players at the Phoenix Hotel in Dedham. This game was played by teams of ten to fourteen players with four bases 60 feet apart and no foul territory. The ball was considerably smaller and lighter than a modern baseball, and runners were still put out by "soaking".

Abner Doubleday myth

The

The myth

Myth is a folklore genre consisting of narratives that play a fundamental role in a society, such as foundational tales or origin myths. Since "myth" is widely used to imply that a story is not objectively true, the identification of a narrat ...

that Abner Doubleday

Abner Doubleday (June 26, 1819 – January 26, 1893) was a career United States Army officer and Union major general in the American Civil War. He fired the first shot in defense of Fort Sumter, the opening battle of the war, and had a p ...

invented baseball in 1839 was once widely promoted and widely believed. There is no evidence for this claim except for the testimony of one unreliable man decades later, and there is persuasive counter-evidence. Doubleday himself never made such a claim; he left many letters and papers, but they contain no description of baseball or any suggestion that he considered himself prominent in the game's history. His ''New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' obituary makes no mention of baseball, nor does a 1911 Encyclopædia article about Doubleday. The story was attacked by baseball writers almost as soon as it came out, but it had the weight of Major League Baseball and the Spalding publishing empire behind it. Contrary to popular belief, Doubleday was never inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame

The National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum is a history museum and hall of fame in Cooperstown, New York, operated by private interests. It serves as the central point of the history of baseball in the United States and displays baseball-r ...

, although a large oil portrait of him was on display at the Hall of Fame building for many years.

Doubleday's invention of baseball was the finding of a panel appointed by Albert Spalding, a former star pitcher and club executive, who had become the leading American sporting goods entrepreneur and sports publisher. Debate on baseball's origins had raged for decades, heating up in the first years of the 20th century, due in part to a 1903 essay baseball historian Henry Chadwick wrote in Spalding's ''Official Baseball Guide'' stating that baseball gradually evolved from English game of “rounders

Rounders is a bat-and-ball game played between two teams. Rounders is a striking and fielding team game that involves hitting a small, hard, leather-cased ball with a rounded end wooden, plastic, or metal bat. The players score by running arou ...

”. To end argument, speculation, and innuendo, Spalding organized the Mills Commission

Abraham Gilbert Mills (March 12, 1844 – August 26, 1929) was the fourth president of the National League of Professional Base Ball Clubs (1883–1884), and is best known for heading the "Mills Commission" which controversially credited Civil Wa ...

in 1905. The members were baseball figures, not historians: Spalding's friend Abraham G. Mills

Abraham Gilbert Mills (March 12, 1844 – August 26, 1929) was the fourth president of the National League, National League of Professional Base Ball Clubs (1883 in baseball, 1883–1884 in baseball, 1884), and is best known for heading the "Mills ...

, a former National League

The National League of Professional Baseball Clubs, known simply as the National League (NL), is the older of two leagues constituting Major League Baseball (MLB) in the United States and Canada, and the world's oldest extant professional team s ...

president; two United States Senators

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and p ...

, former NL president Morgan Bulkeley

Morgan Gardner Bulkeley (December 26, 1837 – November 6, 1922) was an American politician, businessman, and sports executive. A Republican, he served in the American Civil War, and became a Hartford bank president before becoming the third p ...

and former Washington club president Arthur Gorman; former NL president and lifelong secretary-treasurer Nick Young; two other star players turned sporting goods entrepreneurs (George Wright George Wright may refer to:

Politics, law and government

* George Wright (MP) (died 1557), MP for Bedford and Wallingford

* George Wright (governor) (1779–1842), Canadian politician, lieutenant governor of Prince Edward Island

* George Wright ...

and Alfred Reach); and AAU president James E. Sullivan.

The final report, published on December 30, 1907, included three sections: a summary of the panel's findings written by Mills, a letter by John Montgomery Ward

John Montgomery Ward (March 3, 1860 – March 4, 1925), known as Monte Ward, was an American Major League Baseball pitcher, shortstop, second baseman, third baseman, manager, executive, union organizer, owner and author. Ward, of English desce ...

supporting the panel, and a dissenting opinion by Henry Chadwick. The research methods were, at best, dubious. Mills was a close friend of Doubleday, and upon Doubleday's death in 1893 Mills orchestrated his memorial service and burial. Doubleday had been a prominent member of the spiritualist Theosophical Society

The Theosophical Society, founded in 1875, is a worldwide body with the aim to advance the ideas of Theosophy in continuation of previous Theosophists, especially the Greek and Alexandrian Neo-Platonic philosophers dating back to 3rd century CE ...

, in which Spalding's wife was deeply involved and in whose compound in San Diego Spalding was residing at the time. Wright and Reach were effectively Spalding's employees, as he had secretly bought out their sporting-goods businesses some years before. AAU president and Commission secretary Sullivan was Spalding's personal factotum. Several other members had personal reasons to declare baseball as an "American" game, such as Spalding's strong American imperialist views. The Commission found an appealing story: baseball was invented in a quaint rural town without foreigners or industry, by a young man who later graduated from West Point

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known Metonymy, metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a f ...

and served heroically in the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the ...

, Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polici ...

, and U.S. wars against Indians.

The Mills Commission concluded that Doubleday had invented baseball in Cooperstown, New York

Cooperstown is a village in and county seat of Otsego County, New York, United States. Most of the village lies within the town of Otsego, but some of the eastern part is in the town of Middlefield. Located at the foot of Otsego Lake in the ...

in 1839; that Doubleday had invented the word "baseball", designed the diamond, indicated fielders' positions, and written the rules. No written records in the decade between 1839 and 1849 have ever been found to corroborate these claims, nor could Doubleday be interviewed (he died in 1893). The principal source for the story was one letter from elderly Abner Graves, who was a five-year-old resident of Cooperstown in 1839. Graves never mentioned a diamond, positions or the writing of rules. What's more, his reliability as a witness was challenged because he spent his final days in an asylum for the criminally insane. Doubleday was not in Cooperstown in 1839 and may never have visited the town. He was enrolled at West Point

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known Metonymy, metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a f ...

at the time, and there is no record of any leave time. Mills, a lifelong friend of Doubleday, never heard him mention baseball, nor is there any mention of the game in Doubleday's autobiography. In character, Doubleday was bookish and sedentary, with no observable interest in athletics of any sort.

Versions of baseball rules and descriptions of similar games have been found in publications that significantly predate his alleged invention in 1839. Despite this, the ballpark built in 1939 only a few blocks down from the Hall of Fame still bears the name "Doubleday Field". However, aside from the artificial intrusion of the person of Doubleday and the village of Cooperstown, the Mills report was not entirely incorrect in its broad outline: a game related to English rounders was played in America from early times; it was supplanted by a variant form which originated in New York circa 1840. But this development happened in urban New York City, not pastoral Cooperstown, and the men involved were neither farm boys nor West Point cadets.

Knickerbocker rules

The earliest known published rules of baseball in the United States were written in 1845 for a New York City "base ball" club called the Knickerbockers. The purported organizer of the club,

The earliest known published rules of baseball in the United States were written in 1845 for a New York City "base ball" club called the Knickerbockers. The purported organizer of the club, Alexander Cartwright

Alexander Joys Cartwright Jr. (April 17, 1820 – July 12, 1892) was a founding member of the New York Knickerbockers Base Ball Club in the 1840s. Although he was an inductee of the Baseball Hall of Fame and he was sometimes referred to as a " ...

, is one person commonly known as "the father of baseball". The rules themselves were written by the two-man Committee on By-Laws, Vice-president William R. Wheaton and Secretary William H. Tucker. One important rule, the 13th, outlawed "soaking" or "plugging", putting a runner out by hitting him with a thrown ball, introducing instead the concept of the tag; this reflected the use of a farther-traveling and potentially injurious hard ball. Another significant rule, the 15th, specified three outs to an inning for the first time instead of "one out, all out" or "all out, all out." The 10th rule prescribed foul lines and foul balls and the 18th forbade runners advancing on a foul, unlike the "Massachusetts game" in which all batted balls were in play. The Knickerbockers also enlarged the diamond well beyond that of town ball, ''possibly'' to modern size depending on how "paces" is interpreted.

Evolution from the so-called "Knickerbocker Rules

The Knickerbocker Rules are a set of baseball rules formalized by William R. Wheaton and William H. Tucker of the Knickerbocker Base Ball Club in 1845. They have previously been considered to be the basis for the rules of the modern game, altho ...

" to the current rules is fairly well documented. The most significant differences were that overhand pitching was illegal, strikes were only counted if the batter swung and missed, "wides" or balls were not counted at all, a batted ball caught on the first bounce was an out, and a game was played to 21 "aces" or runs rather than for a set number of innings.

It is noteworthy, however, that the Knickerbocker Rules did not cover a number of basic elements of the game. For example, there was no mention of positions or the number of players on a side, the pitching distance was unspecified, the direction of base-running was left open, and it was never stated, though implied, that an "ace" was scored by crossing home plate. In all likelihood, all of these matters except the first were considered so intrinsic to baseball by this time that they were assumed; the number of players on a side, however, remained a matter of debate among clubs until fixed at nine in 1857, the Knickerbockers arguing unsuccessfully for seven-man teams.

On June 3, 1953, Congress officially credited Cartwright with inventing the modern game of baseball. He was already a member of the Baseball Hall of Fame, having been inducted in 1938 for various other contributions to baseball. However, the role of Cartwright himself in the game's invention has been disputed. According to Major League Baseball

Major League Baseball (MLB) is a professional baseball organization and the oldest major professional sports league in the world. MLB is composed of 30 total teams, divided equally between the National League (NL) and the American League (A ...

's official historian, John Thorn, "Cartwright's plaque in the Baseball Hall of Fame declares he set the bases 90 feet apart and established nine innings as a game and nine players as a team. He did none of these things, and every other word of substance on his plaque is false." His authorship may have been exaggerated in a modern attempt to identify a single inventor of the game, and heavily advanced by a relentless public-relations campaign by his grandson. The 1845 Rules themselves are signed by the "Committee on By-Laws", William R. Wheaton and William H. Tucker. There is evidence that these rules had been experimented with and used by New York ball clubs for some time; Cartwright, in his 1848 capacity as club secretary (and a bookseller), was merely the first to have them printed up.

Further evidence of a more collective model of New York baseball's development, and doubts as to Cartwright's role as "inventor", came with the 2004 discovery of a newspaper interview with William R. Wheaton, a founding member of the Gotham Baseball Club in 1837 and first vice president of the Knickerbocker Club, and co-author of its rules, eight years later.

If Wheaton's account, given in 1887, was correct, then most of the innovations credited to Cartwright were, in fact, the work of the Gothams before the Knickerbockers were formed, including a set of written rules. John Thorn, MLB's official historian, argued in his book ''Baseball in the Garden of Eden'' that four members of the Knickerbockers, namely Wheaton,

Further evidence of a more collective model of New York baseball's development, and doubts as to Cartwright's role as "inventor", came with the 2004 discovery of a newspaper interview with William R. Wheaton, a founding member of the Gotham Baseball Club in 1837 and first vice president of the Knickerbocker Club, and co-author of its rules, eight years later.

If Wheaton's account, given in 1887, was correct, then most of the innovations credited to Cartwright were, in fact, the work of the Gothams before the Knickerbockers were formed, including a set of written rules. John Thorn, MLB's official historian, argued in his book ''Baseball in the Garden of Eden'' that four members of the Knickerbockers, namely Wheaton, Louis F. Wadsworth Louis Fenn Wadsworth (May 6, 1825 – March 26, 1908) was an American baseball pioneer, who was a player and organizer with the New York Knickerbockers in the 1840s. He is credited with helping develop the number of innings and players on each team. ...

, Daniel "Doc" Adams and William H. Tucker, have stronger claims than Cartwright as "inventors" of modern baseball.

Legend holds that Cartwright also introduced the game in most of the towns where he stopped on his trek west to California to find gold, a sort of Johnny Appleseed of baseball. This story, however, arose from forged entries in Cartwright's diary which were inserted after his death.

It is however certain that Cartwright, a New York bookseller who later caught gold fever

A gold rush or gold fever is a discovery of gold—sometimes accompanied by other precious metals and rare-earth minerals—that brings an onrush of miners seeking their fortune. Major gold rushes took place in the 19th century in Australia, New Ze ...

, umpired a game in Hoboken, New Jersey on June 19, 1846. The game ended, and the Knickerbockers' opponents (the New York nine) won, 23–1. This was long believed to be the first recorded U.S. baseball game between organized clubs. However, at least three earlier reported games have since been discovered: on October 10, 1845, a game was played between the New York Ball Club and an unnamed club from Brooklyn, at the Union Star Cricket Grounds in Brooklyn; the New Yorks lost 22 to 1. The game was reported in the ''New York Morning News

New is an adjective referring to something recently made, discovered, or created.

New or NEW may refer to:

Music

* New, singer of K-pop group The Boyz

Albums and EPs

* ''New'' (album), by Paul McCartney, 2013

* ''New'' (EP), by Regurgitator ...

'' and ''True Sun'', making it the first ever published baseball result. The New Yorks and Brooklyns played two more games on October 21 and 24, with the first on the New Yorks' home diamond at Elysian Fields and the rematch at the Star Cricket Grounds again.

One point undisputed by historians is that the modern professional major leagues that began in the 1870s developed directly from the amateur urban clubs of the 1840s and 1850s, not from the pastures of small towns such as Cooperstown.

Elysian Fields

Knickerbocker Club

The Knickerbocker Club (known informally as The Knick) is a gentlemen's club in New York City that was founded in 1871. It is considered to be the most exclusive club in the United States and one of the most aristocratic gentlemen's clubs in th ...

began using Elysian Fields in Hoboken

Hoboken ( ; Unami: ') is a city in Hudson County in the U.S. state of New Jersey. As of the 2020 U.S. census, the city's population was 60,417. The Census Bureau's Population Estimates Program calculated that the city's population was 58,69 ...

to play baseball

Baseball is a bat-and-ball sport played between two teams of nine players each, taking turns batting and fielding. The game occurs over the course of several plays, with each play generally beginning when a player on the fielding t ...

, following the New York and Magnolia Ball Clubs which had begun playing there in 1843.

At a preliminary meeting f the Knickerbockers it was suggested that as it was apparent they would soon be driven from Murray Hill, some suitable place should be obtained in New Jersey, where their stay could be permanent; accordingly, a day or two afterwards, enough to make a game assembled at Barclay street ferry, crossed over, marched up the road, prospecting for ground on each side, until they reached the Elysian Fields, where they "settled."On October 21, 1845, the New York Ball Club played the second of their three games against a Brooklyn team there, the series being the first known inter-club baseball games. In June 1846 the Knickerbockers played the "New York nine" (probably the same New York Ball Club) in the first baseball game played between clubs according to codified rules. A plaque and baseball diamond street pavings at 11th and Washington Streets commemorate the event. By the 1850s, several Manhattan-based members of the

National Association of Base Ball Players

The National Association of Base Ball Players (NABBP) was the first organization governing American baseball. (The sport was spelled with two words in the 19th century.)

The first convention of sixteen New York City area clubs in 1857 effecti ...

were using the grounds as their home field.

In 1865 the grounds hosted a championship match between the Mutual Club of New York