Order of Saint Benedict on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

, image = Medalla San Benito.PNG

, caption = Design on the obverse side of the

(English: 'Pray and Work') , founder =

The monastery at Subiaco in Italy, established by

The monastery at Subiaco in Italy, established by  By the ninth century, however, the Benedictine had become the standard form of monastic life throughout the whole of Western Europe, excepting Scotland, Wales, and Ireland, where the Celtic observance still prevailed for another century or two. Largely through the work of

By the ninth century, however, the Benedictine had become the standard form of monastic life throughout the whole of Western Europe, excepting Scotland, Wales, and Ireland, where the Celtic observance still prevailed for another century or two. Largely through the work of

St. Mildred's Priory, on the

St. Mildred's Priory, on the

The first Benedictine to live in the United States was Pierre-Joseph Didier. He came to the United States in 1790 from

The first Benedictine to live in the United States was Pierre-Joseph Didier. He came to the United States in 1790 from

The sense of community was a defining characteristic of the order since the beginning. Section 17 in chapter 58 of the

The sense of community was a defining characteristic of the order since the beginning. Section 17 in chapter 58 of the

''Confoederatio Benedictina Ordinis Sancti Benedicti'', the Benedictine Confederation of Congregations

Saint Vincent Archabbey

Boniface WIMMER

The Alliance for International Monasticism

Benedictines - Abbey of Dendermonde

i

ODIS - Online Database for Intermediary Structures

Benedictine rule for nuns in Middle English, Manuscript, ca. 1320, at The Library of Congress

{{Authority control Catholic spirituality Institutes of consecrated life

Saint Benedict Medal

The Saint Benedict Medal is a Christian sacramental medal containing symbols and text related to the life of Saint Benedict of Nursia, used by Roman Catholics, Lutherans, Western Orthodox, Anglicans and Methodists, in the Benedictine Christian t ...

, abbreviation = OSB

, formation =

, motto = (English: 'Pray and Work') , founder =

Benedict of Nursia

Benedict of Nursia ( la, Benedictus Nursiae; it, Benedetto da Norcia; 2 March AD 480 – 21 March AD 548) was an Italian Christian monk, writer, and theologian who is venerated in the Catholic Church, the Eastern Orthodox Church, the Orient ...

, founding_location = Subiaco Abbey

The Abbey of Saint Scholastica, also known as Subiaco Abbey (Italian: ''Abbazia di Santa Scolastica''), is located just outside the town of Subiaco in the Province of Rome, Region of Lazio, Italy; and is still an active Benedictine abbey, ter ...

, type = Catholic religious order

In the Catholic Church, a religious order is a community of consecrated life with members that profess solemn vows. They are classed as a type of religious institute.

Subcategories of religious orders are:

* canons regular (canons and canone ...

, headquarters = Sant'Anselmo all'Aventino

Sant'Anselmo all'Aventino ( en, Saint Anselm on the Aventine) is a complex located on the Piazza Knights Hospitaller, Cavalieri di Malta Square on the Aventine Hill in Rome's Ripa (rione of Rome), Ripa rione and overseen by the Benedictine Confede ...

, num_members = 6,802 (3,419 priests) as of 2020

, leader_title = Abbot Primate

The Abbot Primate of the Benedictines, Order of St. Benedict serves as the elected representative of the Benedictine Confederation of monasteries in the Catholic Church. While normally possessing no authority over individual autonomous monasterie ...

, leader_name = Gregory Polan, OSB

, main_organ = Benedictine Confederation

The Benedictine Confederation of the Order of Saint Benedict ( la, Confœderatio Benedictina Ordinis Sancti Benedicti) is the international governing body of the Order of Saint Benedict.

Origin

The Benedictine Confederation is a union of monasti ...

, parent_organization = Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

, website =

The Benedictines, officially the Order of Saint Benedict ( la, Ordo Sancti Benedicti, abbreviated as OSB), are a monastic

Monasticism (from Ancient Greek , , from , , 'alone'), also referred to as monachism, or monkhood, is a religion, religious way of life in which one renounces world (theology), worldly pursuits to devote oneself fully to spiritual work. Monastic ...

religious order

A religious order is a lineage of communities and organizations of people who live in some way set apart from society in accordance with their specific religious devotion, usually characterized by the principles of its founder's religious practi ...

of the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

following the Rule of Saint Benedict

The ''Rule of Saint Benedict'' ( la, Regula Sancti Benedicti) is a book of precepts written in Latin in 516 by St Benedict of Nursia ( AD 480–550) for monks living communally under the authority of an abbot.

The spirit of Saint Benedict's Ru ...

. They are also sometimes called the Black Monks, in reference to the colour of their religious habit

A religious habit is a distinctive set of religious clothing worn by members of a religious order. Traditionally some plain garb recognizable as a religious habit has also been worn by those leading the religious eremitic and anchoritic life, ...

s. They were founded by Benedict of Nursia

Benedict of Nursia ( la, Benedictus Nursiae; it, Benedetto da Norcia; 2 March AD 480 – 21 March AD 548) was an Italian Christian monk, writer, and theologian who is venerated in the Catholic Church, the Eastern Orthodox Church, the Orient ...

, a 6th-century monk who laid the foundations of Benedictine monasticism through the formulation of his Rule of Saint Benedict

The ''Rule of Saint Benedict'' ( la, Regula Sancti Benedicti) is a book of precepts written in Latin in 516 by St Benedict of Nursia ( AD 480–550) for monks living communally under the authority of an abbot.

The spirit of Saint Benedict's Ru ...

.

Despite being called an order, the Benedictines do not operate under a single hierarchy but are instead organised as a collection of autonomous monasteries. The order is represented internationally by the Benedictine Confederation

The Benedictine Confederation of the Order of Saint Benedict ( la, Confœderatio Benedictina Ordinis Sancti Benedicti) is the international governing body of the Order of Saint Benedict.

Origin

The Benedictine Confederation is a union of monasti ...

, an organisation set up in 1893 to represent the order's shared interests. They do not have a superior general

A superior general or general superior is the leader or head of a religious institute in the Catholic Church and some other Christian denominations. The superior general usually holds supreme executive authority in the religious community, while t ...

or motherhouse

A motherhouse is the principal house or community for a religious institute. It would normally be where the residence and offices of the religious superior

In a hierarchy or tree structure of any kind, a superior is an individual or position at ...

with universal jurisdiction, but elect an Abbot Primate

The Abbot Primate of the Benedictines, Order of St. Benedict serves as the elected representative of the Benedictine Confederation of monasteries in the Catholic Church. While normally possessing no authority over individual autonomous monasterie ...

to represent themselves to the Vatican

Vatican may refer to:

Vatican City, the city-state ruled by the pope in Rome, including St. Peter's Basilica, Sistine Chapel, Vatican Museum

The Holy See

* The Holy See, the governing body of the Catholic Church and sovereign entity recognized ...

and to the world.

Historical development

The monastery at Subiaco in Italy, established by

The monastery at Subiaco in Italy, established by Benedict of Nursia

Benedict of Nursia ( la, Benedictus Nursiae; it, Benedetto da Norcia; 2 March AD 480 – 21 March AD 548) was an Italian Christian monk, writer, and theologian who is venerated in the Catholic Church, the Eastern Orthodox Church, the Orient ...

529, was the first of the dozen monasteries he founded. He later founded the Abbey of Monte Cassino

Monte Cassino (today usually spelled Montecassino) is a rocky hill about southeast of Rome, in the Latin Valley, Italy, west of Cassino and at an elevation of . Site of the Roman town of Casinum, it is widely known for its abbey, the first h ...

. There is no evidence, however, that he intended to found an order and the Rule of Saint Benedict

The ''Rule of Saint Benedict'' ( la, Regula Sancti Benedicti) is a book of precepts written in Latin in 516 by St Benedict of Nursia ( AD 480–550) for monks living communally under the authority of an abbot.

The spirit of Saint Benedict's Ru ...

presupposes the autonomy of each community. When Monte Cassino was sacked by the Lombards about the year 580, the monks fled to Rome, and it seems probable that this constituted an important factor in the diffusion of a knowledge of Benedictine monasticism.

Copies of Benedict's Rule survived; around 594 Pope Gregory I

Pope Gregory I ( la, Gregorius I; – 12 March 604), commonly known as Saint Gregory the Great, was the bishop of Rome from 3 September 590 to his death. He is known for instigating the first recorded large-scale mission from Rome, the Gregori ...

spoke favorably of it. The Rule is subsequently found in some monasteries in southern Gaul along with other rules used by abbots. Gregory of Tours

Gregory of Tours (30 November 538 – 17 November 594 AD) was a Gallo-Roman historian and Bishop of Tours, which made him a leading prelate of the area that had been previously referred to as Gaul by the Romans. He was born Georgius Florenti ...

says that at Ainay Abbey

The Basilica of Saint-Martin d'Ainay (french: Basilique Saint-Martin d'Ainay) is a Romanesque church in Ainay in the Presqu'île district in the historic centre of Lyon, France. A quintessential example of Romanesque architecture, it was inscribe ...

, in the sixth century, the monks "followed the rules of Basil, Cassian, Caesarius, and other fathers, taking and using whatever seemed proper to the conditions of time and place", and doubtless the same liberty was taken with the Benedictine Rule when it reached them. In Gaul and Switzerland, it gradually supplemented the much stricter Irish or Celtic Rule introduced by Columbanus

Columbanus ( ga, Columbán; 543 – 21 November 615) was an Irish missionary notable for founding a number of monasteries after 590 in the Frankish and Lombard kingdoms, most notably Luxeuil Abbey in present-day France and Bobbio Abbey in pr ...

and others. In many monasteries it eventually entirely displaced the earlier codes.

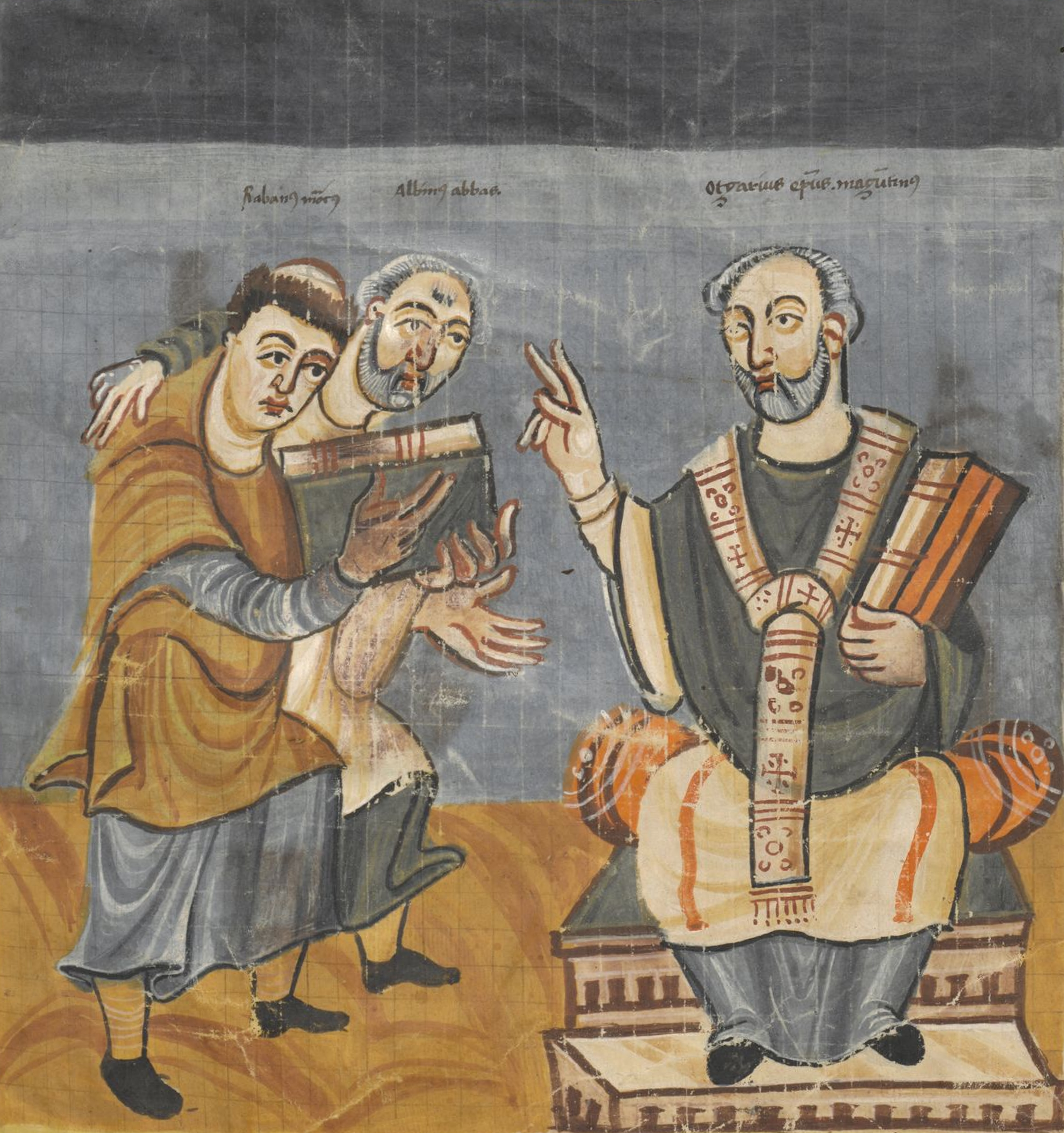

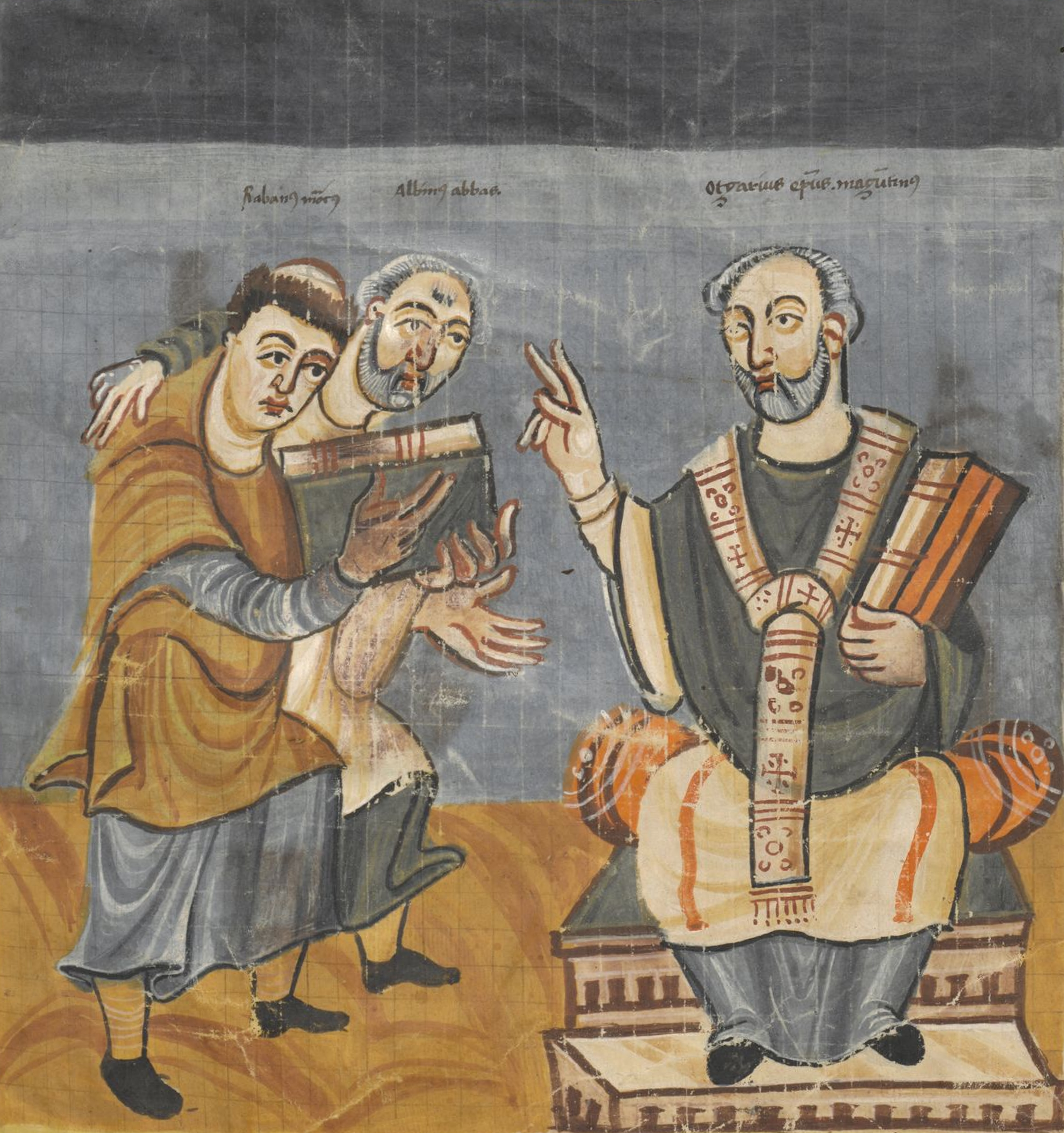

By the ninth century, however, the Benedictine had become the standard form of monastic life throughout the whole of Western Europe, excepting Scotland, Wales, and Ireland, where the Celtic observance still prevailed for another century or two. Largely through the work of

By the ninth century, however, the Benedictine had become the standard form of monastic life throughout the whole of Western Europe, excepting Scotland, Wales, and Ireland, where the Celtic observance still prevailed for another century or two. Largely through the work of Benedict of Aniane

Benedict of Aniane ( la, Benedictus Anianensis; german: Benedikt von Aniane; 747 – 12 February 821 AD), born Witiza and called the Second Benedict, was a Benedictine monk and monastic reformer, who left a large imprint on the religious prac ...

, it became the rule of choice for monasteries throughout the Carolingian empire.

Monastic scriptoria flourished from the ninth through the twelfth centuries. Sacred Scripture was always at the heart of every monastic scriptorium. As a general rule those of the monks who possessed skill as writers made this their chief, if not their sole active work. An anonymous writer of the ninth or tenth century speaks of six hours a day as the usual task of a scribe, which would absorb almost all the time available for active work in the day of a medieval monk.

In the Middle Ages monasteries were often founded by the nobility. Cluny Abbey

Cluny Abbey (; , formerly also ''Cluni'' or ''Clugny''; ) is a former Benedictine monastery in Cluny, Saône-et-Loire, France. It was dedicated to Saint Peter.

The abbey was constructed in the Romanesque architectural style, with three churches ...

was founded by William I, Duke of Aquitaine

William I (22 March 875 – 6 July 918), called the Pious, was the Count of Auvergne from 886 and Duke of Aquitaine from 893, succeeding the Poitevin ruler Ebalus Manser. He made numerous monastic foundations, most important among them the found ...

in 910. The abbey was noted for its strict adherence to the Rule of Saint Benedict. The abbot of Cluny was the superior of all the daughter houses, through appointed priors.

One of the earliest reforms of Benedictine practice was that initiated in 980 by Romuald

Romuald ( la, Romualdus; 951 – traditionally 19 June, c. 1025/27 AD) was the founder of the Camaldolese order and a major figure in the eleventh-century "Renaissance of eremitical asceticism".John Howe, "The Awesome Hermit: The Symbolic ...

, who founded the Camaldolese

The Camaldolese Hermits of Mount Corona ( la, Congregatio Eremitarum Camaldulensium Montis Coronae), commonly called Camaldolese is a monastic order of Pontifical Right for men founded by Saint Romuald. Their name is derived from the Holy Hermita ...

community. The Cistercians

The Cistercians, () officially the Order of Cistercians ( la, (Sacer) Ordo Cisterciensis, abbreviated as OCist or SOCist), are a Catholic religious order of monks and nuns that branched off from the Benedictines and follow the Rule of Saint ...

branched off from the Benedictines in 1098; they are often called the "White monks".

The dominance of the Benedictine monastic way of life began to decline towards the end of the twelfth century, which saw the rise of the Franciscans and Dominicans. Benedictines took a fourth vow of "stability", which professed loyalty to a particular foundation. Not being bound by location, the mendicants were better able to respond to an increasingly "urban" environment. This decline was further exacerbated by the practice of appointing a commendatory abbot, a lay person, appointed by a noble to oversee and to protect the goods of the monastery. Often, however, this resulted in the appropriation of the assets of monasteries at the expense of the community which they were intended to support.

England

The English Benedictine Congregation is the oldest of the nineteen Benedictine congregations. Through the influence ofWilfrid

Wilfrid ( – 709 or 710) was an English bishop and saint. Born a Northumbrian noble, he entered religious life as a teenager and studied at Lindisfarne, at Canterbury, in Francia, and at Rome; he returned to Northumbria in about 660, and ...

, Benedict Biscop

Benedict Biscop (pronounced "bishop"; – 690), also known as Biscop Baducing, was an Anglo-Saxon abbot and founder of Monkwearmouth-Jarrow Priory (where he also founded the famous library) and was considered a saint after his death.

Lif ...

, and Dunstan

Saint Dunstan (c. 909 – 19 May 988) was an English bishop. He was successively Abbot of Glastonbury, Abbot of Glastonbury Abbey, Bishop of Worcester, Bishop of London and Archbishop of Canterbury, later canonised as a saint. His work restor ...

, the Benedictine Rule spread rapidly, and in the North it was adopted in most of the monasteries that had been founded by the Celtic missionaries from Iona. Many of the episcopal sees of England were founded and governed by the Benedictines, and no fewer than nine of the old cathedrals were served by the black monks of the priories attached to them. Monasteries served as hospitals and places of refuge for the weak and homeless. The monks studied the healing properties of plants and minerals to alleviate the sufferings of the sick.

During the English Reformation

The English Reformation took place in 16th-century England when the Church of England broke away from the authority of the pope and the Catholic Church. These events were part of the wider European Protestant Reformation, a religious and poli ...

, all monasteries were dissolved and their lands confiscated by the Crown, forcing the members to flee into exile on the Continent. During the 19th century they were able to return to England.

St. Mildred's Priory, on the

St. Mildred's Priory, on the Isle of Thanet

The Isle of Thanet () is a peninsula forming the easternmost part of Kent, England. While in the past it was separated from the mainland by the Wantsum Channel, it is no longer an island.

Archaeological remains testify to its settlement in anc ...

, Kent

Kent is a county in South East England and one of the home counties. It borders Greater London to the north-west, Surrey to the west and East Sussex to the south-west, and Essex to the north across the estuary of the River Thames; it faces ...

, was built in 1027 on the site of an abbey founded in 670 by the daughter of the first Christian King of Kent

This is a list of the kings of the Anglo-Saxon Kingdom of Kent.

The regnal dates for the earlier kings are known only from Bede. Some kings are known mainly from charters, of which several are forgeries, while others have been subjected to tampe ...

. Currently the priory is home to a community of Benedictine nuns. Five of the most notable English abbeys are the Basilica of St Gregory the Great at Downside, commonly known as Downside Abbey

Downside Abbey is a Benedictine monastery in England and the senior community of the English Benedictine Congregation. Until 2019, the community had close links with Downside School, for the education of children aged eleven to eighteen. Both t ...

, The Abbey of St Edmund, King and Martyr commonly known as Douai Abbey

Douai Abbey is a Benedictine Abbey at Upper Woolhampton, near Thatcham, in the English county of Berkshire, situated within the Roman Catholic Diocese of Portsmouth. Monks from the monastery of St. Edmund's, in Douai, France, came to Woolhampton ...

in Upper Woolhampton, Reading, Berkshire, Ealing Abbey

Ealing Abbey is a Catholic Benedictine monastic foundation on Castlebar Hill in Ealing. It is part of the English Benedictine Congregation. As of 2020, the Abbey had 14 monks.

History

The monastery at Ealing was founded in 1897 from Downside ...

in Ealing, West London, and Worth Abbey

The Abbey of Our Lady, Help of Christians, commonly known as Worth Abbey, is a community of Roman Catholic monks who follow the Rule of St Benedict near Turners Hill village, in West Sussex, England. Founded in 1933, the abbey is part of the En ...

. The late Cardinal Basil Hume was Abbot of Ampleforth Abbey before being appointed Archbishop of Westminster. Examines the abbeys rebuilt after 1850 (by benefactors among the Catholic aristocracy and recusant squirearchy), mainly Benedictine but including a Cistercian Abbey at Mount St. Bernard (by Pugin) and a Carthusian Charterhouse in Sussex. There is a review of book by Richard Lethbridge "Monuments to Catholic confidence," ''The Tablet'' 10 February 2007, 27. Prinknash Abbey

Prinknash Abbey (pronounced locally variously as "Prinidge/Prinnish") (IPA: ) is a Roman Catholic monastery in the Vale of Gloucester in the Diocese of Clifton, near the village of Cranham. It belongs to the English Province of the Subiaco Cas ...

, used by Henry VIII as a hunting lodge, was officially returned to the Benedictines four hundred years later, in 1928. During the next few years, so-called Prinknash Park was used as a home until it was returned to the order.

St. Lawrence's Abbey in Ampleforth, Yorkshire was founded in 1802. In 1955, Ampleforth set up a daughter house, a priory at St. Louis, Missouri which became independent in 1973 and became Saint Louis Abbey

The Abbey of Saint Mary and Saint Louis (French: L’Abbaye Sainte Marie et Saint Louis) is an abbey of the Catholic English Benedictine Congregation (EBC) located in Creve Coeur, in St. Louis County, Missouri in the United States. The Abbey ...

in its own right in 1989.

As of 2015, the English Congregation consists of three abbeys of nuns and ten abbeys of monks. Members of the congregation are found in England, Wales, the United States of America, Peru and Zimbabwe.

In England there are also houses of the Subiaco Cassinese Congregation The Subiaco Cassinese Congregation is an international union of Benedictine houses (abbeys and priories) within the Benedictine Confederation. It developed from the Subiaco Congregation, which was formed in 1867 through the initiative of Dom Piet ...

: Farnborough, Prinknash, and Chilworth: the Solesmes Congregation The Solesmes Congregation is an association of monasteries within the Benedictine Confederation headed by the Abbey of Solesmes.

History

The congregation was founded in 1837 by Pope Gregory XVI as the French Benedictine Congregation, with the the ...

, Quarr and St Cecilia's on the Isle of Wight, as well as a diocesan monastery following the Rule of Saint Benedict: The Community of Our Lady of Glastonbury.

Since the Oxford Movement

The Oxford Movement was a movement of high church members of the Church of England which began in the 1830s and eventually developed into Anglo-Catholicism. The movement, whose original devotees were mostly associated with the University of O ...

, there has also been a modest flourishing of Benedictine monasticism in the Anglican Church

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of the ...

and Protestant Churches. Anglican Benedictine Abbots are invited guests of the Benedictine Abbot Primate in Rome at Abbatial gatherings at Sant'Anselmo. There are an estimated 2,400 celibate Anglican Religious (1,080 men and 1,320 women) in the Anglican Communion as a whole, some of whom have adopted the Rule of Saint Benedict.

In 1168 local Benedictine monks instigated the anti-semitic blood libel

Blood libel or ritual murder libel (also blood accusation) is an antisemitic canardTurvey, Brent E. ''Criminal Profiling: An Introduction to Behavioral Evidence Analysis'', Academic Press, 2008, p. 3. "Blood libel: An accusation of ritual mur ...

of Harold of Gloucester

Harold of Gloucester (died 1168) was a supposed child martyr who was falsely claimed by Benedictine monks to have been ritually murdered by Jews in Gloucester, England, in 1168. The claims arose in the aftermath of the circulation of the fi ...

as a template for explaining later deaths. According to historian Joe Hillaby, the blood libel of Harold was crucially important because for the first time an unexplained child death occurring near the Easter festival was arbitrarily linked to Jews in the vicinity by local Christian churchmen: "they established a pattern quickly taken up elsewhere. Within three years the first ritual murder charge was made in France."

Monastic libraries in England

The forty-eighth Rule of Saint Benedict prescribes extensive and habitual "holy reading" for the brethren. Three primary types of reading were done by the monks during this time. Monks would read privately during their personal time, as well as publicly during services and at meal times. In addition to these three mentioned in the Rule, monks would also read in the infirmary. Monasteries were thriving centers of education, with monks and nuns actively encouraged to learn and pray according to theBenedictine Rule

The ''Rule of Saint Benedict'' ( la, Regula Sancti Benedicti) is a book of precepts written in Latin in 516 by St Benedict of Nursia ( AD 480–550) for monks living communally under the authority of an abbot.

The spirit of Saint Benedict's Ru ...

. Section 38 states that ‘these brothers’ meals should usually be accompanied by reading, and that they were to eat and drink in silence while one read out loud.

Benedictine monks were not allowed worldly possessions, thus necessitating the preservation and collection of sacred texts in monastic libraries for communal use. For the sake of convenience, the books in the monastery were housed in a few different places, namely the sacristy

A sacristy, also known as a vestry or preparation room, is a room in Christian churches for the keeping of vestments (such as the alb and chasuble) and other church furnishings, sacred vessels, and parish records.

The sacristy is usually located ...

, which contained books for the choir and other liturgical books, the rectory

A clergy house is the residence, or former residence, of one or more priests or ministers of religion. Residences of this type can have a variety of names, such as manse, parsonage, rectory or vicarage.

Function

A clergy house is typically ow ...

, which housed books for public reading such as sermons and lives of the saints, and the library

A library is a collection of materials, books or media that are accessible for use and not just for display purposes. A library provides physical (hard copies) or digital access (soft copies) materials, and may be a physical location or a vir ...

, which contained the largest collection of books and was typically in the cloister.

The first record of a monastic library in England is in Canterbury

Canterbury (, ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and UNESCO World Heritage Site, situated in the heart of the City of Canterbury local government district of Kent, England. It lies on the River Stour, Kent, River Stour.

...

. To assist with Augustine of Canterbury

Augustine of Canterbury (early 6th century – probably 26 May 604) was a monk who became the first Archbishop of Canterbury in the year 597. He is considered the "Apostle to the English" and a founder of the English Church.Delaney '' ...

's English mission, Pope Gregory the Great

Pope Gregory I ( la, Gregorius I; – 12 March 604), commonly known as Saint Gregory the Great, was the bishop of Rome from 3 September 590 to his death. He is known for instigating the first recorded large-scale mission from Rome, the Gregori ...

gave him nine books which included the Gregorian Bible in two volumes, the Psalter of Augustine, two copies of the Gospels

Gospel originally meant the Christian message ("the gospel"), but in the 2nd century it came to be used also for the books in which the message was set out. In this sense a gospel can be defined as a loose-knit, episodic narrative of the words an ...

, two martyrologies

A martyrology is a catalogue or list of martyrs and other saints and beatification, beati arranged in the calendar order of their anniversaries or feasts. Local martyrologies record exclusively the custom of a particular Church. Local lists were ...

, an Exposition of the Gospels and Epistles, and a Psalter

A psalter is a volume containing the Book of Psalms, often with other devotional material bound in as well, such as a liturgical calendar and litany of the Saints. Until the emergence of the book of hours in the Late Middle Ages, psalters we ...

. Theodore of Tarsus

Theodore of Tarsus ( gr, Θεόδωρος Ταρσοῦ; 60219 September 690) was Archbishop of Canterbury from 668 to 690. Theodore grew up in Tarsus, but fled to Constantinople after the Persian Empire conquered Tarsus and other cities. After ...

brought Greek books to Canterbury more than seventy years later, when he founded a school for the study of Greek.

France

Monasteries were among the institutions of the Catholic Church swept away during theFrench Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are considere ...

. Monasteries were again allowed to form in the 19th century under the Bourbon Restoration. Later that century, under the Third French Republic

The French Third Republic (french: Troisième République, sometimes written as ) was the system of government adopted in France from 4 September 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed during the Franco-Prussian War, until 10 July 1940 ...

, laws were enacted preventing religious teaching. The original intent was to allow secular schools. Thus in 1880 and 1882, Benedictine teaching monks were effectively exiled; this was not completed until 1901.

Germany

Saint Blaise Abbey in theBlack Forest

The Black Forest (german: Schwarzwald ) is a large forested mountain range in the state of Baden-Württemberg in southwest Germany, bounded by the Rhine Valley to the west and south and close to the borders with France and Switzerland. It is t ...

of Baden-Württemberg

Baden-Württemberg (; ), commonly shortened to BW or BaWü, is a German state () in Southwest Germany, east of the Rhine, which forms the southern part of Germany's western border with France. With more than 11.07 million inhabitants across a ...

is believed to have been founded around the latter part of the tenth century. Between 1070 and 1073 there seem to have been contacts between St. Blaise and the Cluniac Abbey of Fruttuaria 300px, Bell tower of the abbey.

Fruttuaria is an abbey in the territory of San Benigno Canavese, about twenty kilometers north of Turin, northern Italy.

History

The abbey was founded by Guglielmo da Volpiano. The first stone was laid 23 February ...

in Italy, which led to St. Blaise following the Fruttuarian reforms. The Empress Agnes

Agnes of Poitou ( – 14 December 1077), was the queen of Germany from 1043 and empress of the Holy Roman Empire from 1046 until 1056 as the wife of Emperor Henry III. From 1056 to 1061, she ruled the Holy Roman Empire as regent during the ...

was a patron of Fruttuaria, and retired there in 1065 before moving to Rome. The Empress was instrumental in introducing Fruttuaria's Benedictine customs, as practiced at Cluny, to Saint Blaise Abbey in Baden-Württemberg

Baden-Württemberg (; ), commonly shortened to BW or BaWü, is a German state () in Southwest Germany, east of the Rhine, which forms the southern part of Germany's western border with France. With more than 11.07 million inhabitants across a ...

. Other houses either reformed by, or founded as priories of, St. Blasien were: Muri Abbey

Muri Abbey (german: Kloster Muri) is a Benedictine monastery dedicated to Saint Martin of Tours. It flourished for over eight centuries at Muri, in the Canton of Aargau, near Zürich, Switzerland. It is currently established as Muri-Gries in Sout ...

(1082), Ochsenhausen Abbey

Ochsenhausen Abbey (formerly Ochsenhausen Priory; german: Reichskloster or ) was a Benedictine monastery in Ochsenhausen in the district of Biberach in Baden-Württemberg, Germany.

History

The traditional story of the foundation, in which there ...

(1093), Göttweig Abbey

Göttweig Abbey (german: Stift Göttweig) is a Benedictine monastery near Krems in Lower Austria. It was founded in 1083 by Altmann, Bishop of Passau.

History

Göttweig Abbey was founded as a monastery of canons regular by Blessed Altmann (c ...

(1094), Stein am Rhein

Stein am Rhein (abbreviated as Stein a. R.) is a historic town and a municipality in the canton of Schaffhausen in Switzerland.

The town's medieval centre retains the ancient street plan. The site of the city wall, and the city gates are preserve ...

Abbey (before 1123) and Prüm Abbey

Prüm Abbey is a former Benedictine abbey in Prüm, now in the diocese of Trier (Germany), founded by the Frankish widow Bertrada the elder and her son Charibert, Count of Laon, in 721. The first abbot was Angloardus.

The Abbey ruled over a va ...

(1132). It also had significant influence on the abbeys of Alpirsbach

Alpirsbach () is a town in the district of Freudenstadt in Baden-Württemberg, Germany. It is situated in the Black Forest on the Kinzig river, south of Freudenstadt.

Because of the local brewery “Alpirsbacher Klosterbräu“, the monastery ...

(1099), Ettenheim

Ettenheim ( gsw, label= Low Alemannic, Äddene) is a town in the Ortenaukreis, Baden-Württemberg, Germany.

History

Ettenheim was founded in the 8th century by Eddo, bishop of Strasbourg, and the was founded at about that time. Ettenheim recei ...

münster (1124) and Sulzburg

Sulzburg is a town in the district Breisgau-Hochschwarzwald, in Baden-Württemberg, Germany. It is situated on the western slope of the Black Forest, 20 km southwest of Freiburg.

Sulzburg had a long tradition of continuous Jewish settlemen ...

(ca. 1125), and the priories of Weitenau (now part of Steinen, ca. 1100), Bürgel

Bürgel is a town in the Saale-Holzland district, in Thuringia, Germany. It is situated 12 km east of Jena

Jena () is a German city and the second largest city in Thuringia. Together with the nearby cities of Erfurt and Weimar, it forms ...

(before 1130) and Sitzenkirch (ca. 1130).

Switzerland

Kloster Rheinau was a Benedictine monastery in Rheinau in the Canton of Zürich, Switzerland, founded in about 778. The abbey of Our Lady of the Angels was founded in 1120.United States

The first Benedictine to live in the United States was Pierre-Joseph Didier. He came to the United States in 1790 from

The first Benedictine to live in the United States was Pierre-Joseph Didier. He came to the United States in 1790 from Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

and served in the Ohio and St. Louis areas until his death. The first actual Benedictine monastery founded was Saint Vincent Archabbey

Saint Vincent Archabbey is a Benedictine monastery in Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania in the city of Latrobe. A member of the American-Cassinese Congregation, it is the oldest Benedictine monastery in the United States and the largest in th ...

, located in Latrobe, Pennsylvania

Latrobe is a city in Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania, in the United States and part of the Pittsburgh metropolitan area.

The city population was 8,338 as of the 2010 census (9,265 in 1990). It is located near Pennsylvania's scenic Chestnut Rid ...

. It was founded in 1832 by Boniface Wimmer

Archabbot Boniface Wimmer, (1809–1887) was a German monk who in 1846 founded the first Benedictine monastery in the United States, Saint Vincent Archabbey in Latrobe, Pennsylvania, forty miles southeast of Pittsburgh. In 1855 Wimmer founded th ...

, a German monk, who sought to serve German immigrants in America. In 1856, Wimmer started to lay the foundations for St. John's Abbey in Minnesota. In 1876, Herman Wolfe, of Saint Vincent Archabbey established Belmont Abbey in North Carolina. By the time of his death in 1887, Wimmer had sent Benedictine monks to Kansas, New Jersey, North Carolina, Georgia, Florida, Alabama, Illinois, and Colorado.

Wimmer also asked for Benedictine sister

A sister is a woman or a girl who shares one or more parents with another individual; a female sibling. The male counterpart is a brother. Although the term typically refers to a familial relationship, it is sometimes used endearingly to refer to ...

s to be sent to America by St. Walburg Convent in Eichstätt

Eichstätt () is a town in the federal state of Bavaria, Germany, and capital of the district of Eichstätt. It is located on the Altmühl river and has a population of around 13,000. Eichstätt is also the seat of the Roman Catholic Diocese ...

, Bavaria. In 1852, Sister Benedicta Riepp

A sister is a woman or a girl who shares one or more parents with another individual; a female sibling. The male counterpart is a brother. Although the term typically refers to a familial relationship, it is sometimes used endearingly to refer to ...

and two other sisters founded St. Marys, Pennsylvania

St. Marys is a city in Elk County, Pennsylvania, Elk County, Pennsylvania, United States. The population is 12,429 as of 2019. Originally a small town inhabited by mostly Bavarian Roman Catholics, it was founded December 8, 1842. It is home to Str ...

. Soon they would send sisters to Michigan, New Jersey, and Minnesota.

By 1854, Swiss monks began to arrive and founded St. Meinrad Abbey in Indiana, and they soon spread to Arkansas and Louisiana. They were soon followed by Swiss sisters.

There are now over 100 Benedictine houses across America. Most Benedictine houses are part of one of four large Congregations: American-Cassinese, Swiss-American, St. Scholastica, and St. Benedict. The congregations mostly are made up of monasteries that share the same lineage. For instance the American-Cassinese congregation included the 22 monasteries that descended from Boniface Wimmer.

Benedictine vow and life

The sense of community was a defining characteristic of the order since the beginning. Section 17 in chapter 58 of the

The sense of community was a defining characteristic of the order since the beginning. Section 17 in chapter 58 of the Rule of Saint Benedict

The ''Rule of Saint Benedict'' ( la, Regula Sancti Benedicti) is a book of precepts written in Latin in 516 by St Benedict of Nursia ( AD 480–550) for monks living communally under the authority of an abbot.

The spirit of Saint Benedict's Ru ...

states the solemn promise candidates for reception into a Benedictine community are required to make: a promise of stability (i.e. to remain in the same community), ''conversatio morum'' (an idiomatic Latin phrase suggesting "conversion of manners"; see below) and obedience to the community's superior. This solemn commitment tends to be referred to as the "Benedictine vow" and is the Benedictine antecedent and equivalent of the evangelical counsels professed by candidates for reception into a religious order

A religious order is a lineage of communities and organizations of people who live in some way set apart from society in accordance with their specific religious devotion, usually characterized by the principles of its founder's religious practi ...

.

Much scholarship over the last fifty years has been dedicated to the translation and interpretation of "''conversatio morum''". The older translation "conversion of life" has generally been replaced with phrases such as " onversion toa monastic manner of life", drawing from the Vulgate's use of ''conversatio'' as a translation of "citizenship" or "homeland" in Philippians 3:20. Some scholars have claimed that the vow formula of the Rule is best translated as "to live in this place as a monk, in obedience to its rule and abbot."

Benedictine abbot

Abbot is an ecclesiastical title given to the male head of a monastery in various Western religious traditions, including Christianity. The office may also be given as an honorary title to a clergyman who is not the head of a monastery. The fem ...

s and abbess

An abbess (Latin: ''abbatissa''), also known as a mother superior, is the female superior of a community of Catholic nuns in an abbey.

Description

In the Catholic Church (both the Latin Church and Eastern Catholic), Eastern Orthodox, Coptic ...

es have full jurisdiction of their abbey

An abbey is a type of monastery used by members of a religious order under the governance of an abbot or abbess. Abbeys provide a complex of buildings and land for religious activities, work, and housing of Christian monks and nuns.

The conce ...

and thus absolute authority over the monk

A monk (, from el, μοναχός, ''monachos'', "single, solitary" via Latin ) is a person who practices religious asceticism by monastic living, either alone or with any number of other monks. A monk may be a person who decides to dedica ...

s or nun

A nun is a woman who vows to dedicate her life to religious service, typically living under vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience in the enclosure of a monastery or convent.''The Oxford English Dictionary'', vol. X, page 599. The term is o ...

s who are resident. This authority includes the power to assign duties, to decide which books may or may not be read, to regulate comings and goings, and to punish and to excommunicate

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to end or at least regulate the communion of a member of a congregation with other members of the religious institution who are in normal communion with each other. The purpose ...

, in the sense of an enforced isolation from the monastic community.

A tight communal timetablethe horarium

This is a glossary of terms used within the Catholic Church. Some terms used in everyday English have a different meaning in the context of the Catholic faith, including brother, confession, confirmation, exemption, faithful, father, ordinary, r ...

is meant to ensure that the time given by God is not wasted but used in God's service, whether for prayer, work, meals, spiritual reading or sleep. The order's motto ''Ora et Labora

The phrase pray and work (or 'pray and labor'; Latin: ''ora et labora'') refers to the Catholic monastic practice of working and praying, generally associated with its use in the Rule of Saint Benedict.

History

"Ora et labora" (pray and work ...

'' ("pray and work") may be said to summarize its way of life.

Although Benedictines do not take a vow of silence, hours of strict silence are set, and at other times silence is maintained as much as is practically possible. Social conversations tend to be limited to communal recreation times. But such details, like the many other details of the daily routine of a Benedictine house that the Rule of Saint Benedict leaves to the discretion of the superior, are set out in its 'customary'. A ' customary' is the code adopted by a particular Benedictine house, adapting the Rule to local conditions.

In the Roman Catholic Church, according to the norms of the 1983 Code of Canon Law

The 1983 ''Code of Canon Law'' (abbreviated 1983 CIC from its Latin title ''Codex Iuris Canonici''), also called the Johanno-Pauline Code, is the "fundamental body of ecclesiastical laws for the Latin Church". It is the second and current comp ...

, a Benedictine abbey is a "religious institute

A religious institute is a type of institute of consecrated life in the Catholic Church whose members take religious vows and lead a life in community with fellow members. Religious institutes are one of the two types of institutes of consecrate ...

" and its members are therefore members of the consecrated life

Consecrated life (also known as religious life) is a state of life in the Catholic Church lived by those faithful who are called to follow Jesus Christ in a more exacting way. It includes those in institutes of consecrated life (religious and se ...

. While Canon Law 588 §1 explains that Benedictine monks are "neither clerical nor lay", they can, however, be ordained.

Some monasteries adopt a more active ministry in living the monastic life, running schools or parishes; others are more focused on contemplation, with more of an emphasis on prayer and work within the confines of the cloister.

Benedictines' rules contained ritual purification

Ritual purification is the ritual prescribed by a religion by which a person is considered to be free of ''uncleanliness'', especially prior to the worship of a deity, and ritual purity is a state of ritual cleanliness. Ritual purification may ...

, and inspired by Benedict of Nursia

Benedict of Nursia ( la, Benedictus Nursiae; it, Benedetto da Norcia; 2 March AD 480 – 21 March AD 548) was an Italian Christian monk, writer, and theologian who is venerated in the Catholic Church, the Eastern Orthodox Church, the Orient ...

encouragement for the practice of therapeutic bathing

Bathing is the act of washing the body, usually with water, or the immersion of the body in water. It may be practiced for personal hygiene, religious ritual or therapeutic purposes. By analogy, especially as a recreational activity, the term is ...

; Benedictine monks played a role in the development and promotion of spa

A spa is a location where mineral-rich spring water (and sometimes seawater) is used to give medicinal baths. Spa towns or spa resorts (including hot springs resorts) typically offer various health treatments, which are also known as balneoth ...

s.

Organization

Benedictine monasticism is fundamentally different from other Western religious orders insofar as its individual communities are not part of a religious order with "Generalates" and "Superiors General". Each Benedictine house is independent and governed by an abbot. In modern times, the various groups of autonomous houses (national, reform, etc.) have formed themselves loosely into congregations (for example, Cassinese, English, Solesmes, Subiaco, Camaldolese, Sylvestrines). These, in turn, are represented in theBenedictine Confederation

The Benedictine Confederation of the Order of Saint Benedict ( la, Confœderatio Benedictina Ordinis Sancti Benedicti) is the international governing body of the Order of Saint Benedict.

Origin

The Benedictine Confederation is a union of monasti ...

that came into existence through Pope Leo XIII

Pope Leo XIII ( it, Leone XIII; born Vincenzo Gioacchino Raffaele Luigi Pecci; 2 March 1810 – 20 July 1903) was the head of the Catholic Church from 20 February 1878 to his death in July 1903. Living until the age of 93, he was the second-old ...

's Apostolic Brief "''Summum semper''" on 12 July 1893. Additionally, Pope Leo established the office of Abbot Primate

The Abbot Primate of the Benedictines, Order of St. Benedict serves as the elected representative of the Benedictine Confederation of monasteries in the Catholic Church. While normally possessing no authority over individual autonomous monasterie ...

as the abbot elected to represent this Confederation to the Vatican

Vatican may refer to:

Vatican City, the city-state ruled by the pope in Rome, including St. Peter's Basilica, Sistine Chapel, Vatican Museum

The Holy See

* The Holy See, the governing body of the Catholic Church and sovereign entity recognized ...

and to the world. The headquarters for the Benedictine Confederation and the Abbot Primate is the Primatial Abbey of Sant'Anselmo built by Pope Leo XIII and located in Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

, Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

.

In 1313 Bernardo Tolomei

Bernardo Tolomei (10 May 1272 – 20 August 1348) was an Italian Roman Catholic theologian and the founder of the Congregation of the Blessed Virgin of Monte Oliveto. In the Roman Martyrology he is commemorated on August 20, but in the Benedi ...

established the Order of Our Lady of Mount Olivet. The community adopted the Rule of Saint Benedict and received canonical approval in 1344. The Olivetans are part of the Benedictine Confederation.

Other orders

The Rule of Saint Benedict is also used by a number of religious orders that began as reforms of the Benedictine tradition such as theCistercian

The Cistercians, () officially the Order of Cistercians ( la, (Sacer) Ordo Cisterciensis, abbreviated as OCist or SOCist), are a Catholic religious order of monks and nuns that branched off from the Benedictines and follow the Rule of Saint ...

s and Trappist

The Trappists, officially known as the Order of Cistercians of the Strict Observance ( la, Ordo Cisterciensis Strictioris Observantiae, abbreviated as OCSO) and originally named the Order of Reformed Cistercians of Our Lady of La Trappe, are a ...

s. These groups are separate congregations and not members of the Benedictine Confederation

The Benedictine Confederation of the Order of Saint Benedict ( la, Confœderatio Benedictina Ordinis Sancti Benedicti) is the international governing body of the Order of Saint Benedict.

Origin

The Benedictine Confederation is a union of monasti ...

.

Although Benedictines are traditionally Catholic, there are also some communities that follow the Rule of Saint Benedict within the Anglican Communion

The Anglican Communion is the third largest Christian communion after the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches. Founded in 1867 in London, the communion has more than 85 million members within the Church of England and other ...

, Eastern Orthodox Church

The Eastern Orthodox Church, also called the Orthodox Church, is the second-largest Christian church, with approximately 220 million baptized members. It operates as a communion of autocephalous churches, each governed by its bishops via ...

, and Lutheran Church

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Catholic Church launched th ...

.

Notable Benedictines

Saints and Blesseds

Monks

*Henri Quentin

Dom Henri Quentin (7 October 1872, Saint-Thierry - 4 February 1935, Rome) was a French Benedictine monk. A philologist specializing in biblical texts and martyrologies, he was the creator of an original method of textual criticism (sometimes cal ...

Popes

Founders of abbeys and congregations and prominent reformers

Scholars, historians, and spiritual writers

Maurists

Members of theCongregation of Saint Maur

The Congregation of St. Maur, often known as the Maurists, were a congregation of French Benedictines, established in 1621, and known for their high level of scholarship. The congregation and its members were named after Saint Maurus (died 565), a ...

, a prerevolutionary French congregation

A congregation is a large gathering of people, often for the purpose of worship.

Congregation may also refer to:

*Church (congregation), a Christian organization meeting in a particular place for worship

*Congregation (Roman Curia), an administra ...

of Benedictines known for their scholarship:Bishops and martyrs

Twentieth century

Nuns

Oblates

BenedictineOblate

In Christianity (especially in the Roman Catholic, Orthodox, Anglican and Methodist traditions), an oblate is a person who is specifically dedicated to God or to God's service.

Oblates are individuals, either laypersons or clergy, normally livi ...

s endeavor to embrace the spirit of the Benedictine vow in their own life in the world. Oblates are affiliated with a particular monastery.

See also

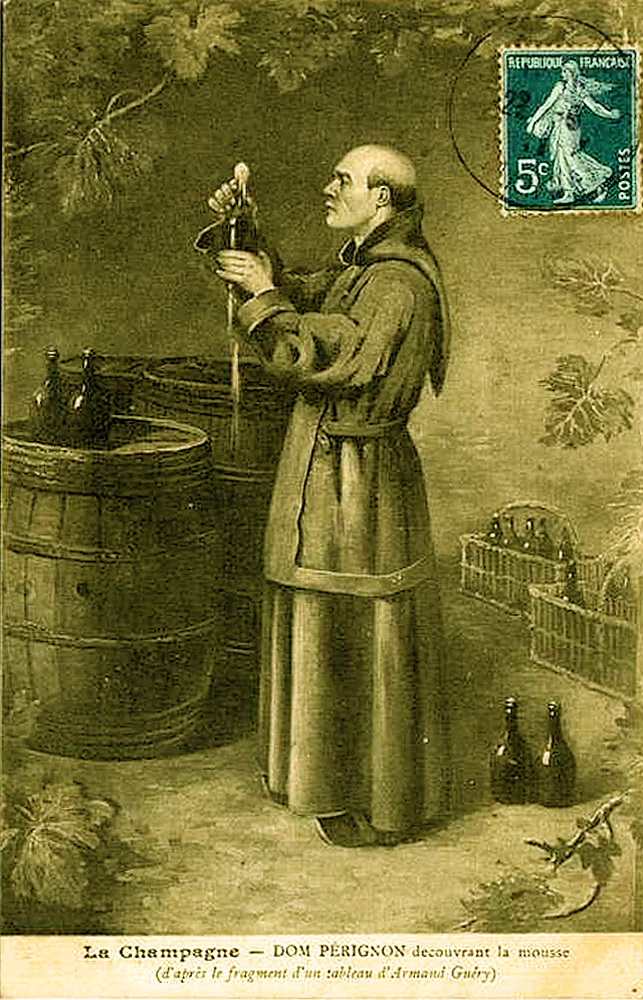

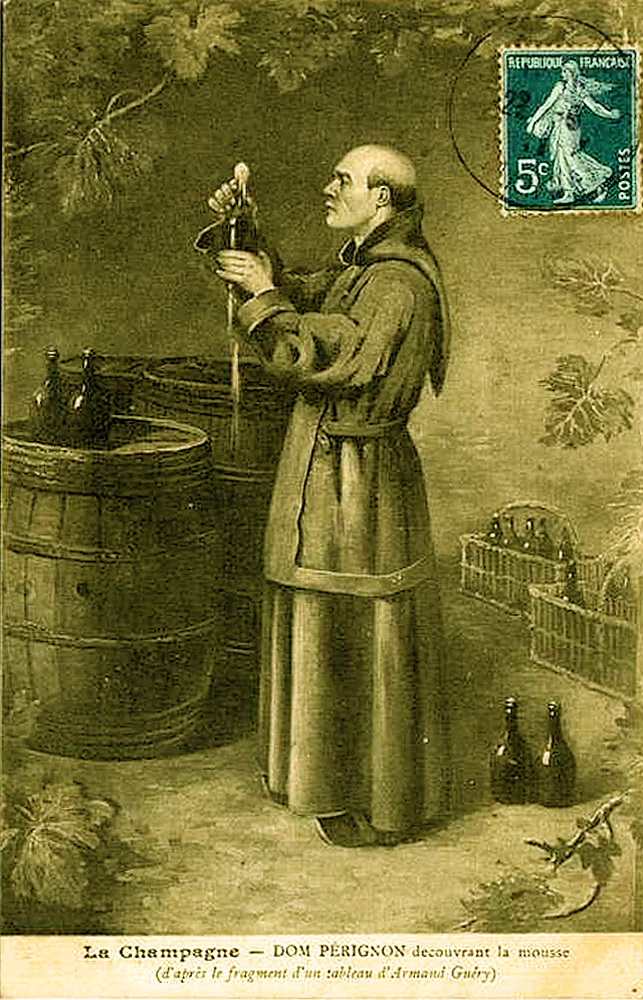

* Dom Pierre Pérignon *Benedictine Confederation

The Benedictine Confederation of the Order of Saint Benedict ( la, Confœderatio Benedictina Ordinis Sancti Benedicti) is the international governing body of the Order of Saint Benedict.

Origin

The Benedictine Confederation is a union of monasti ...

* Catholic religious order

In the Catholic Church, a religious order is a community of consecrated life with members that profess solemn vows. They are classed as a type of religious institute.

Subcategories of religious orders are:

* canons regular (canons and canone ...

* Cistercians

The Cistercians, () officially the Order of Cistercians ( la, (Sacer) Ordo Cisterciensis, abbreviated as OCist or SOCist), are a Catholic religious order of monks and nuns that branched off from the Benedictines and follow the Rule of Saint ...

* French Romanesque architecture

Romanesque architecture appeared in France at the end of the 10th century, with the development of feudal society and the rise and spread of monastic orders, particularly the Benedictines, which built many important abbeys and monasteries in th ...

* Sisters of Social Service The Sisters of Social Service (SSS; hu, Szociális Testvérek Társasága, la, Societas Sororum Socialium) are a Roman Catholic religious institute of women founded in Hungary in 1923 by Margit Slachta. The sisters adopted the social mission of t ...

* Trappists

The Trappists, officially known as the Order of Cistercians of the Strict Observance ( la, Ordo Cisterciensis Strictioris Observantiae, abbreviated as OCSO) and originally named the Order of Reformed Cistercians of Our Lady of La Trappe, are a ...

References

Further reading

* DomColumba Marmion

Columba Marmion, OSB, born Joseph Aloysius Marmion (April 1, 1858 – January 30, 1923) was a Benedictine Irish monk and the third Abbot of Maredsous Abbey in Belgium. Beatified by Pope John Paul II on September 3, 2000, Columba was one of t ...

, ''Christ the Ideal of the Monk – Spiritual Conferences on the Monastic and Religious Life'' (Engl. edition London 1926, trsl. from the French by a nun of Tyburn Convent).

* Mariano Dell'Omo, ''Storia del monachesimo occidentale dal medioevo all'età contemporanea. Il carisma di san Benedetto tra VI e XX secolo''. Jaca Book, Milano 2011.

*

External links

*''Confoederatio Benedictina Ordinis Sancti Benedicti'', the Benedictine Confederation of Congregations

Saint Vincent Archabbey

Boniface WIMMER

The Alliance for International Monasticism

Benedictines - Abbey of Dendermonde

i

ODIS - Online Database for Intermediary Structures

Benedictine rule for nuns in Middle English, Manuscript, ca. 1320, at The Library of Congress

{{Authority control Catholic spirituality Institutes of consecrated life