Orange (fruit) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

An orange is a

An orange is a

Citrus Genome Database In 2019, 79 million

All citrus trees belong to the single

All citrus trees belong to the single

aggie-horticulture.tamu.edu

/ref> Other citrus groups also known as oranges are: * An enormous number of cultivars have, like the sweet orange, a mix of pomelo and mandarin ancestry. Some cultivars are mandarin-pomelo hybrids, bred from the same parents as the sweet orange (e.g. the

An enormous number of cultivars have, like the sweet orange, a mix of pomelo and mandarin ancestry. Some cultivars are mandarin-pomelo hybrids, bred from the same parents as the sweet orange (e.g. the

The sweet orange is not a wild fruit, having arisen in domestication from a cross between a non-pure

The sweet orange is not a wild fruit, having arisen in domestication from a cross between a non-pure

Common oranges (also called "white", "round", or "blond" oranges) constitute about two-thirds of all the orange production. The majority of this crop is used for juice extraction.

Common oranges (also called "white", "round", or "blond" oranges) constitute about two-thirds of all the orange production. The majority of this crop is used for juice extraction.

The Valencia orange is a late-season fruit, and therefore a popular variety when navel oranges are out of season. This is why an anthropomorphic orange was chosen as the

The Valencia orange is a late-season fruit, and therefore a popular variety when navel oranges are out of season. This is why an anthropomorphic orange was chosen as the

* Bahia: grown in Brazil and Uruguay

* Bali: grown in Bali, Indonesia. Larger than other orange

* Belladonna: grown in Italy

* Berna: grown mainly in Spain

* Biondo Comune ("ordinary blond"): widely grown in the Mediterranean basin, especially in North Africa, Egypt, Greece (where it is called "koines"), Italy (where it is also known as "Liscio"), and Spain; it also is called "Beledi" and "Nostrale"; in Italy, this variety ripens in December, earlier than the competing Tarocco varietyMaterial Identification Sheet

* Bahia: grown in Brazil and Uruguay

* Bali: grown in Bali, Indonesia. Larger than other orange

* Belladonna: grown in Italy

* Berna: grown mainly in Spain

* Biondo Comune ("ordinary blond"): widely grown in the Mediterranean basin, especially in North Africa, Egypt, Greece (where it is called "koines"), Italy (where it is also known as "Liscio"), and Spain; it also is called "Beledi" and "Nostrale"; in Italy, this variety ripens in December, earlier than the competing Tarocco varietyMaterial Identification Sheet

Webcapua.com. Retrieved on 2011-10-02 (in French). * Biondo Riccio: grown in Italy * Byeonggyul: grown in Jeju Island, South Korea * Cadanera: a seedless orange of excellent flavor grown in Algeria, Morocco, and Spain; it begins to ripen in November and is known by a wide variety of trade names, such as Cadena Fina, Cadena sin Jueso, Precoce de Valence ("early from Valencia"), Precoce des Canaries, and Valence san Pepins ("seedless Valencia"); it was first grown in Spain in 1870 * Calabrese or Calabrese Ovale: grown in Italy * Carvalhal: grown in Portugal * Castellana: grown in Spain * Charmute: grown in Brazil * Cherry Orange: grown in southern China and Japan * Clanor: grown in South Africa * Dom João: grown in Portugal * Fukuhara: grown in Japan * Gardner: grown in Florida, this mid-season orange ripens around the beginning of February, approximately the same time as the Midsweet variety; Gardner is about as hardy as Sunstar and Midsweet * Homosassa: grown in Florida * * Malta: grown in Pakistan

* Maltaise Blonde: grown in north Africa

* Maltaise Ovale: grown in South Africa and in California under the names of Garey's or California Mediterranean Sweet

* Marrs: grown in Texas, California and Iran, it is relatively low in acid

* Medan: grown in Medan, Indonesia

* Midsweet: grown in Florida, it is a newer scion similar to the Hamlin and Pineapple varieties, it is hardier than Pineapple and ripens later; the fruit production and quality are similar to those of the Hamlin, but the juice has a deeper color

* Moro Tarocco: grown in Italy, it is oval, resembles a tangelo, and has a distinctive caramel-colored endocarp; this color is the result of a pigment called anthocarpium, not usually found in citruses, but common in red fruits and flowers; the original mutation occurred in Sicily in the seventeenth century

* Narinja: grown in Andhra, South India

* Parson Brown: grown in Florida, Mexico, and Turkey, it once was a widely grown Florida juice orange, its popularity has declined since new varieties with more juice, better yield, and higher acid and sugar content have been developed; it originated as a chance seedling in Florida in 1865; its fruits are round, medium large, have a thick, pebbly peel and contain 10 to 30 seeds; it still is grown because it is the earliest maturing fruit in the United States, usually maturing in early September in the Valley district of Texas, and from early October to January in Florida;Ferguson, James J

* Malta: grown in Pakistan

* Maltaise Blonde: grown in north Africa

* Maltaise Ovale: grown in South Africa and in California under the names of Garey's or California Mediterranean Sweet

* Marrs: grown in Texas, California and Iran, it is relatively low in acid

* Medan: grown in Medan, Indonesia

* Midsweet: grown in Florida, it is a newer scion similar to the Hamlin and Pineapple varieties, it is hardier than Pineapple and ripens later; the fruit production and quality are similar to those of the Hamlin, but the juice has a deeper color

* Moro Tarocco: grown in Italy, it is oval, resembles a tangelo, and has a distinctive caramel-colored endocarp; this color is the result of a pigment called anthocarpium, not usually found in citruses, but common in red fruits and flowers; the original mutation occurred in Sicily in the seventeenth century

* Narinja: grown in Andhra, South India

* Parson Brown: grown in Florida, Mexico, and Turkey, it once was a widely grown Florida juice orange, its popularity has declined since new varieties with more juice, better yield, and higher acid and sugar content have been developed; it originated as a chance seedling in Florida in 1865; its fruits are round, medium large, have a thick, pebbly peel and contain 10 to 30 seeds; it still is grown because it is the earliest maturing fruit in the United States, usually maturing in early September in the Valley district of Texas, and from early October to January in Florida;Ferguson, James J

Your Florida Dooryard Citrus Guide – Appendices, Definitions and Glossary

edis.ifas.ufl.edu its peel and juice color are poor, as is the quality of its juice * Pera: grown in Brazil, it is very popular in the Brazilian citrus industry and yielded 7.5 million metric tons in 2005 * Pera Coroa: grown in Brazil * Pera Natal: grown in Brazil * Pera Rio: grown in Brazil * Pineapple: grown in North and South America and India * Pontianak: oval-shaped orange grown especially in Pontianak, Indonesia * Premier: grown in South Africa * Rhode Red: is a mutation of the Valencia orange, but the color of its flesh is more intense; it has more juice, and less acidity and vitamin C than the Valencia; it was discovered by Paul Rhode in 1955 in a grove near Sebring, Florida * Roble: it was first shipped from Spain in 1851 by Joseph Roble to his homestead in what is now Roble's Park in Tampa, Florida; it is known for its high sugar content * Queen: grown in South Africa * Salustiana: grown in North Africa * Sathgudi: grown in Tamil Nadu, South India * Seleta, Selecta: grown in Australia and Brazil, it is high in acid * Shamouti Masry: grown in Egypt; it is a richer variety of Shamouti * Sunstar: grown in Florida, this newer cultivar ripens in mid-season (December to March) and it is more resistant to cold and fruit-drop than the competing Pineapple variety; the color of its juice is darker than that of the competing Hamlin * Tomango: grown in South Africa * Verna: grown in Algeria, Mexico, Morocco, and Spain * Vicieda: grown in Algeria, Morocco, and Spain * Westin: grown in Brazil * Xã Đoài orange: grown in Vietnam

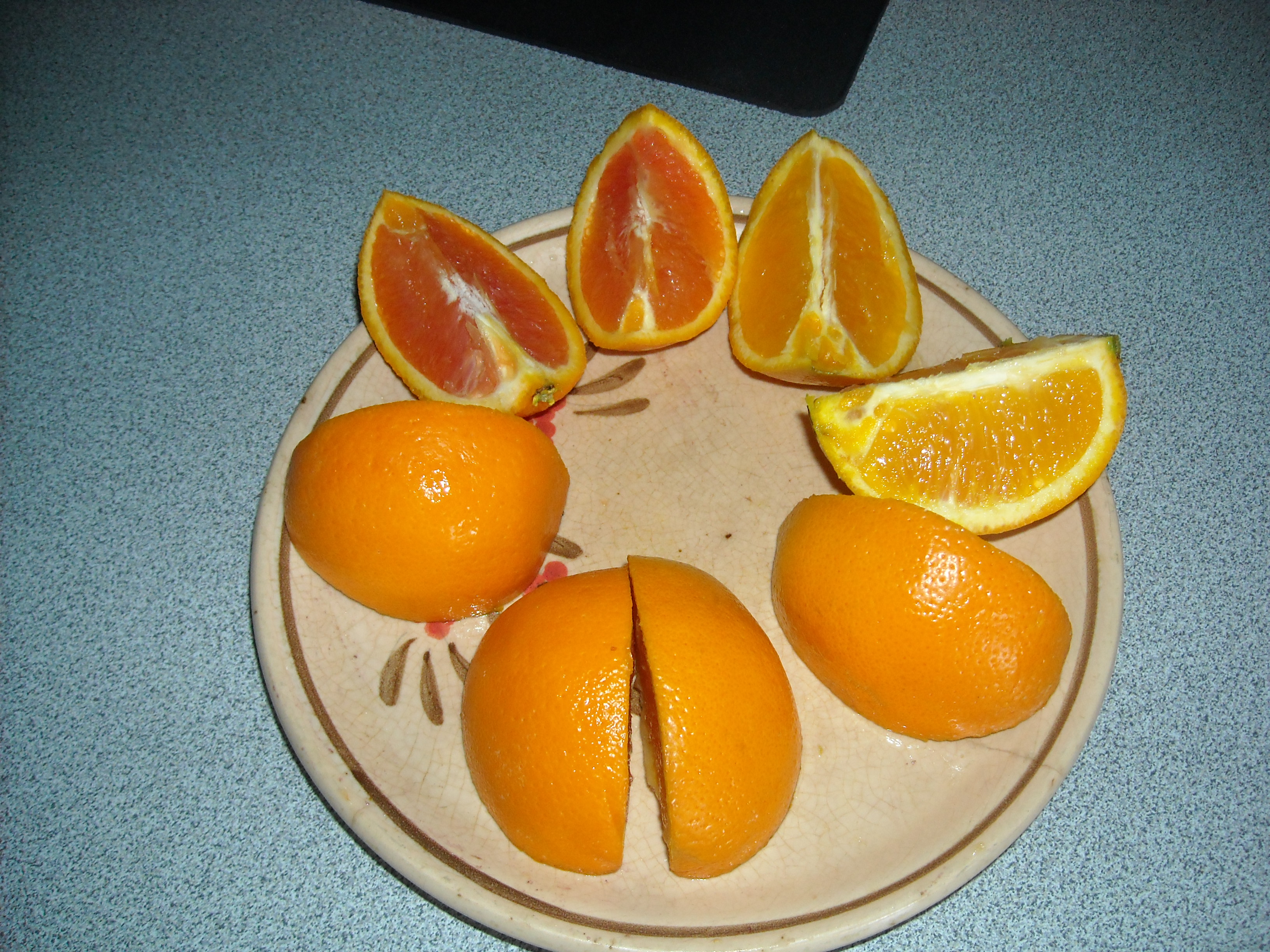

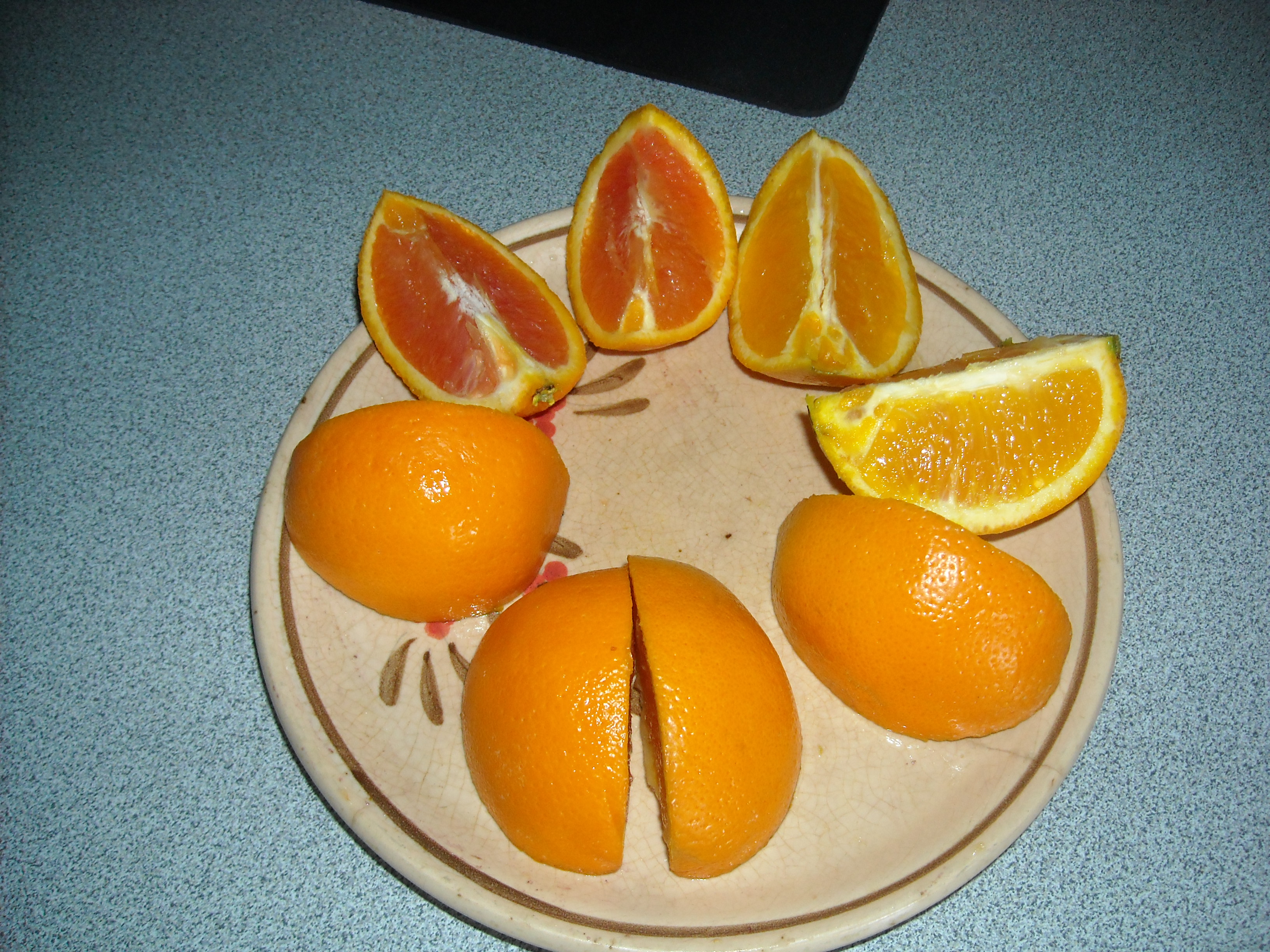

Cara cara oranges (also called "red navel") are a type of navel orange grown mainly in

Cara cara oranges (also called "red navel") are a type of navel orange grown mainly in

University of California, Riverside South African cara caras are ready for market in early August, while Venezuelan fruits arrive in October and Californian fruits in late November.

Blood oranges are a natural mutation of ''C. sinensis'', although today the majority of them are hybrids. High concentrations of anthocyanin give the rind, flesh, and juice of the fruit their characteristic dark red color. Blood oranges were first discovered and cultivated in

Blood oranges are a natural mutation of ''C. sinensis'', although today the majority of them are hybrids. High concentrations of anthocyanin give the rind, flesh, and juice of the fruit their characteristic dark red color. Blood oranges were first discovered and cultivated in

The taste of oranges is determined mainly by the relative ratios of sugars and acids, whereas orange aroma derives from volatile organic compounds, including alcohols,

The taste of oranges is determined mainly by the relative ratios of sugars and acids, whereas orange aroma derives from volatile organic compounds, including alcohols,

Orange juice contains only about one-fifth the citric acid of

Orange juice contains only about one-fifth the citric acid of

(USDA; February, 1997) The general characteristics graded are color (both hue and uniformity), firmness, maturity, varietal characteristics, texture, and shape. ''Fancy'', the highest grade, requires the highest grade of color and an absence of blemishes, while the terms ''Bright'', ''Golden'', ''Bronze'', and ''Russet'' concern solely discoloration. Grade numbers are determined by the amount of unsightly blemishes on the skin and firmness of the fruit that do not affect consumer safety. The USDA separates blemishes into three categories: # General blemishes: ammoniation, buckskin, caked melanose, creasing, decay, scab, split navels, sprayburn, undeveloped segments, unhealed segments, and wormy fruit # Injuries to fruit: bruises, green spots, oil spots, rough, wide, or protruding navels, scale, scars, skin breakdown, and thorn scratches # Damage caused by dirt or other foreign material, disease, dryness, or mushy condition, hail, insects, riciness or woodiness, and sunburn. The USDA uses a separate grading system for oranges used for juice because appearance and texture are irrelevant in this case. There are only two grades: US Grade AA Juice and US Grade A Juice, which are given to the oranges before processing. Juice grades are determined by three factors: # The juiciness of the orange # The amount of solids in the juice (at least 10% solids are required for the AA grade) # The proportion of anhydric citric acid in fruit solids

Like most citrus plants, oranges do well under moderate temperatures—between —and require considerable amounts of sunshine and water. It has been suggested the use of water resources by the citrus industry in the Middle East is a contributing factor to the desiccation of the region. Another significant element in the full development of the fruit is the temperature variation between summer and winter and, between day and night. In cooler climates, oranges can be grown indoors.

As oranges are sensitive to frost, there are different methods to prevent frost damage to crops and trees when subfreezing temperatures are expected. A common process is to spray the trees with water so as to cover them with a thin layer of ice that will stay just ''at'' the freezing point, insulating them even if air temperatures drop far lower. This is because water continues to lose heat as long as the environment is colder than it is, and so the water turning to ice in the environment cannot damage the trees. This practice, however, offers protection only for a very short time. Another procedure is burning fuel oil in

Like most citrus plants, oranges do well under moderate temperatures—between —and require considerable amounts of sunshine and water. It has been suggested the use of water resources by the citrus industry in the Middle East is a contributing factor to the desiccation of the region. Another significant element in the full development of the fruit is the temperature variation between summer and winter and, between day and night. In cooler climates, oranges can be grown indoors.

As oranges are sensitive to frost, there are different methods to prevent frost damage to crops and trees when subfreezing temperatures are expected. A common process is to spray the trees with water so as to cover them with a thin layer of ice that will stay just ''at'' the freezing point, insulating them even if air temperatures drop far lower. This is because water continues to lose heat as long as the environment is colder than it is, and so the water turning to ice in the environment cannot damage the trees. This practice, however, offers protection only for a very short time. Another procedure is burning fuel oil in

Commercially, oranges can be stored by refrigeration in controlled-atmosphere chambers for up to twelve weeks after harvest. Storage life ultimately depends on cultivar, maturity, pre-harvest conditions, and handling. In stores and markets, however, oranges should be displayed on non-refrigerated shelves.

At home, oranges have a shelf life of about one month. In either case, optimally, they are stored loosely in an open or perforated plastic bag.

Commercially, oranges can be stored by refrigeration in controlled-atmosphere chambers for up to twelve weeks after harvest. Storage life ultimately depends on cultivar, maturity, pre-harvest conditions, and handling. In stores and markets, however, oranges should be displayed on non-refrigerated shelves.

At home, oranges have a shelf life of about one month. In either case, optimally, they are stored loosely in an open or perforated plastic bag.

FCLA.edu

/ref> As from 2009, 0.87% of the trees in Brazil's main orange growing areas (São Paulo and Minas Gerais) showed symptoms of greening, an increase of 49% over 2008.GAIN Report Number: BR9006

, USDA Foreign Agricultural Service (June, 2009) The disease is spread primarily by two species of

''Citrus sinensis'' List of Chemicals (Dr. Duke's Phytochemical and Ethnobotanical Databases)

Oranges: Safe Methods to Store, Preserve, and Enjoy

(2006). University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources. Accessed May 23, 2014. {{Authority control Articles containing video clips Cocktail garnishes Crops originating from China Fruits originating in Asia Symbols of California Symbols of Florida Tropical agriculture

An orange is a

An orange is a fruit

In botany, a fruit is the seed-bearing structure in flowering plants that is formed from the ovary after flowering.

Fruits are the means by which flowering plants (also known as angiosperms) disseminate their seeds. Edible fruits in particu ...

of various citrus

''Citrus'' is a genus of flowering trees and shrubs in the rue family, Rutaceae. Plants in the genus produce citrus fruits, including important crops such as oranges, lemons, grapefruits, pomelos, and limes. The genus ''Citrus'' is native to ...

species in the family

Family (from la, familia) is a group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or affinity (by marriage or other relationship). The purpose of the family is to maintain the well-being of its members and of society. Idea ...

Rutaceae

The Rutaceae is a family, commonly known as the rueRUTACEAE

in BoDD – Botanical Der ...

(see list of plants known as orange); it primarily refers to ''Citrus'' × ''sinensis'', which is also called sweet orange, to distinguish it from the related ''Citrus × aurantium'', referred to as in BoDD – Botanical Der ...

bitter orange

Bitter orange, Seville orange, bigarade orange, or marmalade orange is the citrus tree ''Citrus'' × ''aurantium'' and its fruit. It is native to Southeast Asia and has been spread by humans to many parts of the world. It is probably a cross be ...

. The sweet orange reproduces asexually ( apomixis through nucellar embryony); varieties of sweet orange arise through mutations.

The orange is a hybrid between pomelo

The pomelo ( ), ''Citrus maxima'', is the largest citrus fruit from the family Rutaceae and the principal ancestor of the grapefruit. It is a natural, non-hybrid, citrus fruit, native to Southeast Asia. Similar in taste to a sweet grapefr ...

(''Citrus maxima'') and mandarin (''Citrus reticulata''). The chloroplast genome, and therefore the maternal line, is that of pomelo. The sweet orange has had its full genome sequenced.

The orange originated in a region encompassing Southern China

South China () is a geographical and cultural region that covers the southernmost part of China. Its precise meaning varies with context. A notable feature of South China in comparison to the rest of China is that most of its citizens are not n ...

, Northeast India

, native_name_lang = mni

, settlement_type =

, image_skyline =

, image_alt =

, image_caption =

, motto =

, image_map = Northeast india.png

, ...

, and Myanmar

Myanmar, ; UK pronunciations: US pronunciations incl. . Note: Wikipedia's IPA conventions require indicating /r/ even in British English although only some British English speakers pronounce r at the end of syllables. As John Wells explai ...

, and the earliest mention of the sweet orange was in Chinese literature in 314 BC. , orange trees were found to be the most cultivated fruit tree in the world. Orange trees are widely grown in tropical and subtropical climates for their sweet fruit. The fruit of the orange tree

Orange most often refers to:

*Orange (fruit), the fruit of the tree species '' Citrus'' × ''sinensis''

** Orange blossom, its fragrant flower

*Orange (colour), from the color of an orange, occurs between red and yellow in the visible spectrum

* ...

can be eaten fresh, or processed for its juice or fragrant peel. , sweet oranges accounted for approximately 70% of citrus production.''Organisms''Citrus Genome Database In 2019, 79 million

tonne

The tonne ( or ; symbol: t) is a unit of mass equal to 1000 kilograms. It is a non-SI unit accepted for use with SI. It is also referred to as a metric ton to distinguish it from the non-metric units of the short ton ( United State ...

s of oranges were grown worldwide, with Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

producing 22% of the total, followed by China and India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

.

Taxonomy and terminology

All citrus trees belong to the single

All citrus trees belong to the single genus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus comes above species and below family. In binomial nom ...

''Citrus'' and remain almost entirely interfertile. This includes grapefruits, lemon

The lemon (''Citrus limon'') is a species of small evergreen trees in the flowering plant family Rutaceae, native to Asia, primarily Northeast India (Assam), Northern Myanmar or China.

The tree's ellipsoidal yellow fruit is used for culin ...

s, limes

Limes may refer to:

* the plural form of lime (disambiguation)

Lime commonly refers to:

* Lime (fruit), a green citrus fruit

* Lime (material), inorganic materials containing calcium, usually calcium oxide or calcium hydroxide

* Lime (color), a ...

, oranges, and various other types and hybrids. As the interfertility of oranges and other citrus has produced numerous hybrids and cultivar

A cultivar is a type of cultivated plant that people have selected for desired traits and when propagated retain those traits. Methods used to propagate cultivars include: division, root and stem cuttings, offsets, grafting, tissue culture ...

s, and bud mutations have also been selected, citrus taxonomy is fairly controversial, confusing or inconsistent. The fruit of any citrus tree is considered a hesperidium, a kind of modified berry; it is covered by a rind originated by a rugged thickening of the ovary wall.Bailey, H. and Bailey, E. (1976). ''Hortus Third''. Cornell University MacMillan. N.Y. p. 275.

Different names have been given to the many varieties of the species. ''Orange'' applies primarily to the sweet orange – ''Citrus sinensis'' ( L.) Osbeck. The orange tree is an evergreen

In botany, an evergreen is a plant which has foliage that remains green and functional through more than one growing season. This also pertains to plants that retain their foliage only in warm climates, and contrasts with deciduous plants, whic ...

, flowering

A flower, sometimes known as a bloom or blossom, is the reproductive structure found in flowering plants (plants of the division Angiospermae). The biological function of a flower is to facilitate reproduction, usually by providing a mechanism ...

tree, with an average height of , although some very old specimens can reach . Its oval leaves, alternately arranged, are long and have crenulate margins. Sweet oranges grow in a range of different sizes, and shapes varying from spherical to oblong. Inside and attached to the rind is a porous white tissue, the white, bitter mesocarp

Fruit anatomy is the plant anatomy of the internal structure of fruit. Fruits are the mature ovary or ovaries of one or more flowers. They are found in three main anatomical categories: aggregate fruits, multiple fruits, and simple fruits. Agg ...

or albedo (''pith

Pith, or medulla, is a tissue in the stems of vascular plants. Pith is composed of soft, spongy parenchyma cells, which in some cases can store starch. In eudicotyledons, pith is located in the center of the stem. In monocotyledons, it ext ...

''). The orange contains a number of distinct ''carpel

Gynoecium (; ) is most commonly used as a collective term for the parts of a flower that produce ovules and ultimately develop into the fruit and seeds. The gynoecium is the innermost whorl of a flower; it consists of (one or more) '' pistils' ...

s'' (segments) inside, typically about ten, each delimited by a membrane, and containing many juice-filled vesicles and usually a few seeds (''pips''). When unripe, the fruit is green. The grainy irregular rind of the ripe fruit can range from bright orange to yellow-orange, but frequently retains green patches or, under warm climate conditions, remains entirely green. Like all other citrus fruits, the sweet orange is non- climacteric. The ''Citrus sinensis'' group is subdivided into four classes with distinct characteristics: common oranges, blood or pigmented oranges, navel oranges, and acidless oranges.''Home Fruit Production – Oranges'', Julian W. Sauls, Ph.D., Professor & Extension Horticulturist, Texas Cooperative Extension (December, 1998)aggie-horticulture.tamu.edu

/ref> Other citrus groups also known as oranges are: *

Bergamot orange

''Citrus bergamia'', the bergamot orange (pronounced ), is a fragrant citrus fruit the size of an orange, with a yellow or green color similar to a lime, depending on ripeness.

Genetic research into the ancestral origins of extant citrus cult ...

(''Citrus bergamia Risso''), grown mainly in Italy for its peel, producing a primary essence for perfumes, also used to flavor Earl Grey tea

Earl Grey tea is a tea blend which has been flavoured with oil of bergamot. The rind's fragrant oil is added to black tea to give Earl Grey its unique taste. Traditionally, Earl Grey was made from black teas such as Chinese keemun, and there ...

. It is a hybrid of bitter orange x lemon.

* Bitter orange

Bitter orange, Seville orange, bigarade orange, or marmalade orange is the citrus tree ''Citrus'' × ''aurantium'' and its fruit. It is native to Southeast Asia and has been spread by humans to many parts of the world. It is probably a cross be ...

(''Citrus aurantium''), also known as Seville orange, sour orange (especially when used as rootstock

A rootstock is part of a plant, often an underground part, from which new above-ground growth can be produced. It could also be described as a stem with a well developed root system, to which a bud from another plant is grafted. It can refer to a ...

for a sweet orange tree), bigarade orange and marmalade orange. Like the sweet orange, it is a pomelo x mandarin hybrid, but arose from a distinct hybridization event."Plant Profile for Citrus ×aurantium L. (pro sp.), http://plants.usda.gov/java/profile?symbol=CIAU8

* Mandarin orange

The mandarin orange (''Citrus reticulata''), also known as the mandarin or mandarine, is a small citrus tree fruit. Treated as a distinct species of orange, it is usually eaten plain or in fruit salads. Tangerines are a group of orange-colou ...

(''Citrus reticulata'') is an original species of citrus, and is a progenitor of the common orange.

* Trifoliate orange

The trifoliate orange, ''Citrus trifoliata'' or ''Poncirus trifoliata'', is a member of the family Rutaceae. Whether the trifoliate oranges should be considered to belong to their own genus, ''Poncirus'', or be included in the genus ''Citrus'' is ...

(''Poncirus trifoliata''), sometimes included in the genus (classified as ''Citrus trifoliata''). It often serves as a rootstock

A rootstock is part of a plant, often an underground part, from which new above-ground growth can be produced. It could also be described as a stem with a well developed root system, to which a bud from another plant is grafted. It can refer to a ...

for sweet orange trees and other ''Citrus'' cultivar

A cultivar is a type of cultivated plant that people have selected for desired traits and when propagated retain those traits. Methods used to propagate cultivars include: division, root and stem cuttings, offsets, grafting, tissue culture ...

s.

An enormous number of cultivars have, like the sweet orange, a mix of pomelo and mandarin ancestry. Some cultivars are mandarin-pomelo hybrids, bred from the same parents as the sweet orange (e.g. the

An enormous number of cultivars have, like the sweet orange, a mix of pomelo and mandarin ancestry. Some cultivars are mandarin-pomelo hybrids, bred from the same parents as the sweet orange (e.g. the tangor

The tangor (''C. reticulata'' × ''C. sinensis'') is a citrus fruit hybrid of the mandarin orange (''Citrus reticulata'') and the sweet orange (''Citrus sinensis''). The name "tangor" is a formation from the "tang" of tangerine and the "or" of ...

and ponkan tangerine). Other cultivars are sweet orange x mandarin hybrids (e.g. clementines). Mandarin traits generally include being smaller and oblate, easier to peel, and less acidic. Pomelo

The pomelo ( ), ''Citrus maxima'', is the largest citrus fruit from the family Rutaceae and the principal ancestor of the grapefruit. It is a natural, non-hybrid, citrus fruit, native to Southeast Asia. Similar in taste to a sweet grapefr ...

traits include a thick white albedo (rind pith, mesocarp) that is more closely attached to the segments.

Orange trees generally are grafted. The bottom of the tree, including the roots and trunk, is called rootstock, while the fruit-bearing top has two different names: budwood (when referring to the process of grafting) and scion

Scion may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Fictional entities

*Scion, a playable class in the game '' Path of Exile'' (2013)

*Atlantean Scion, a device in the ''Tomb Raider'' video game series

*Scions, an alien race in the video game ''B ...

(when mentioning the variety of orange).

Etymology

The word ''orange'' derives from theSanskrit

Sanskrit (; attributively , ; nominally , , ) is a classical language belonging to the Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in South Asia after its predecessor languages had diffused there from the northwest in the late ...

( or ), meaning 'orange tree'. The Sanskrit word reached European languages

Most languages of Europe belong to the Indo-European language family. Out of a total European population of 744 million as of 2018, some 94% are native speakers of an Indo-European language. Within Indo-European, the three largest phyla are Ro ...

through Persian

Persian may refer to:

* People and things from Iran, historically called ''Persia'' in the English language

** Persians, the majority ethnic group in Iran, not to be conflated with the Iranic peoples

** Persian language, an Iranian language of the ...

() and its Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walter ...

derivative ().

The word entered Late Middle English

Middle English (abbreviated to ME) is a form of the English language that was spoken after the Norman conquest of 1066, until the late 15th century. The English language underwent distinct variations and developments following the Old English p ...

in the 14th century via Old French

Old French (, , ; Modern French: ) was the language spoken in most of the northern half of France from approximately the 8th to the 14th centuries. Rather than a unified language, Old French was a linkage of Romance dialects, mutually intellig ...

(in the phrase ). The French word, in turn, comes from Old Provençal , based on the Arabic word. In several languages, the initial ''n'' present in earlier forms of the word dropped off because it may have been mistaken as part of an indefinite article ending in an ''n'' sound. In French, for example, may have been heard as . This linguistic change is called juncture loss. The color was named after the fruit, and the first recorded use of ''orange'' as a color name in English was in 1512.

History

The sweet orange is not a wild fruit, having arisen in domestication from a cross between a non-pure

The sweet orange is not a wild fruit, having arisen in domestication from a cross between a non-pure mandarin orange

The mandarin orange (''Citrus reticulata''), also known as the mandarin or mandarine, is a small citrus tree fruit. Treated as a distinct species of orange, it is usually eaten plain or in fruit salads. Tangerines are a group of orange-colou ...

and a hybrid pomelo

The pomelo ( ), ''Citrus maxima'', is the largest citrus fruit from the family Rutaceae and the principal ancestor of the grapefruit. It is a natural, non-hybrid, citrus fruit, native to Southeast Asia. Similar in taste to a sweet grapefr ...

that had a substantial mandarin component. Since its chloroplast DNA

Chloroplast DNA (cpDNA) is the DNA located in chloroplasts, which are photosynthetic organelles located within the cells of some eukaryotic organisms. Chloroplasts, like other types of plastid, contain a genome separate from that in the cell n ...

is that of pomelo, it was likely the hybrid pomelo, perhaps a BC1 pomelo backcross, that was the maternal parent of the first orange. Based on genomic analysis, the relative proportions of the ancestral species in the sweet orange is approximately 42% pomelo and 58% mandarin. and Supplement All varieties of the sweet orange descend from this prototype cross, differing only by mutations selected for during agricultural propagation. Sweet oranges have a distinct origin from the bitter orange, which arose independently, perhaps in the wild, from a cross between pure mandarin and pomelo parents. The earliest mention of the sweet orange in Chinese literature dates from 314 B.C.

In Europe, the Moors

The term Moor, derived from the ancient Mauri, is an exonym first used by Christian Europeans to designate the Muslim inhabitants of the Maghreb, the Iberian Peninsula, Sicily and Malta during the Middle Ages.

Moors are not a distinct or ...

introduced the orange to the Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese and Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in southwestern Europe, def ...

which was known as Al-Andalus, with large scale cultivation starting in the 10th century as evidenced by complex irrigation techniques specifically adapted to support orange orchards. Citrus fruits — among them the bitter orange — were introduced to Sicily in the 9th century during the period of the Emirate of Sicily, but the sweet orange was unknown until the late 15th century or the beginnings of the 16th century, when Italian and Portuguese merchants brought orange trees into the Mediterranean area. Shortly afterward, the sweet orange quickly was adopted as an edible fruit. It was considered a luxury food grown by wealthy people in private conservatories, called orangerie

An orangery or orangerie was a room or a dedicated building on the grounds of fashionable residences of Northern Europe from the 17th to the 19th centuries where orange and other fruit trees were protected during the winter, as a very lar ...

s. By 1646, the sweet orange was well known throughout Europe. Louis XIV

, house = Bourbon

, father = Louis XIII

, mother = Anne of Austria

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France

, death_date =

, death_place = Palace of Ver ...

of France had a great love of orange trees, and built the grandest of all royal Orangeries at the Palace of Versailles. At Versailles potted orange trees in solid silver tubs were placed throughout the rooms of the palace, while the Orangerie allowed year-round cultivation of the fruit to supply the court. When Louis condemned his finance minister, Nicolas Fouquet

Nicolas Fouquet, marquis de Belle-Île, vicomte de Melun et Vaux (27 January 1615 – 23 March 1680) was the Superintendent of Finances in France from 1653 until 1661 under King Louis XIV. He had a glittering career, and acquired enormous wealth ...

, in 1664, part of the treasures which he confiscated were over 1,000 orange trees from Fouquet's estate at Vaux-le-Vicomte

The Château de Vaux-le-Vicomte (English: Palace of Vaux-le-Vicomte) is a Baroque French château located in Maincy, near Melun, southeast of Paris in the Seine-et-Marne department of Île-de-France.

Built between 1658 and 1661 for Nicolas ...

.

Spanish travelers introduced the sweet orange into the American continent. On his second voyage in 1493, Christopher Columbus may have planted the fruit in Hispaniola. Subsequent expeditions in the mid-1500s brought sweet oranges to South America and Mexico, and to Florida in 1565, when Pedro Menéndez de Avilés founded St Augustine

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; la, Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430), also known as Saint Augustine, was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North Afr ...

. Spanish missionaries brought orange trees to Arizona between 1707 and 1710, while the Franciscans

, image = FrancescoCoA PioM.svg

, image_size = 200px

, caption = A cross, Christ's arm and Saint Francis's arm, a universal symbol of the Franciscans

, abbreviation = OFM

, predecessor =

, ...

did the same in San Diego, California, in 1769. An orchard was planted at the San Gabriel Mission around 1804 and a commercial orchard was established in 1841 near present-day Los Angeles. In Louisiana, oranges were probably introduced by French explorers.

Archibald Menzies

Archibald Menzies ( ; 15 March 1754 – 15 February 1842) was a Scottish surgeon, botanist and naturalist. He spent many years at sea, serving with the Royal Navy, private merchants, and the Vancouver Expedition. He was the first recorded Euro ...

, the botanist and naturalist on the Vancouver Expedition

The Vancouver Expedition (1791–1795) was a four-and-a-half-year voyage of exploration and diplomacy, commanded by Captain George Vancouver of the Royal Navy. The British expedition circumnavigated the globe and made contact with five continen ...

, collected orange seeds in South Africa, raised the seedlings onboard and gave them to several Hawaiian chiefs in 1792. Eventually, the sweet orange was grown in wide areas of the Hawaiian Islands, but its cultivation stopped after the arrival of the Mediterranean fruit fly in the early 1900s.

As oranges are rich in vitamin C and do not spoil easily, during the Age of Discovery, Portuguese

Portuguese may refer to:

* anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Portugal

** Portuguese cuisine, traditional foods

** Portuguese language, a Romance language

*** Portuguese dialects, variants of the Portuguese language

** Portu ...

, Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many Latin American countries

**Spanish cuisine

Other places

* Spanish, Ontario, Can ...

, and Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

sailors planted citrus trees along trade routes to prevent scurvy.

Florida farmers obtained seeds from New Orleans around 1872, after which orange groves were established by grafting the sweet orange on to sour orange rootstocks.

Varieties

Common

Common oranges (also called "white", "round", or "blond" oranges) constitute about two-thirds of all the orange production. The majority of this crop is used for juice extraction.

Common oranges (also called "white", "round", or "blond" oranges) constitute about two-thirds of all the orange production. The majority of this crop is used for juice extraction.

Valencia

mascot

A mascot is any human, animal, or object thought to bring luck, or anything used to represent a group with a common public identity, such as a school, professional sports team, society, military unit, or brand name. Mascots are also used as fi ...

for the 1982 FIFA World Cup, held in Spain. The mascot was named Naranjito ("little orange") and wore the colors of the Spanish national football team.

Thomas Rivers, an English nurseryman, imported this variety from the Azores Islands and catalogued it in 1865 under the name Excelsior. Around 1870, he provided trees to S. B. Parsons, a Long Island nurseryman, who in turn sold them to E. H. Hart of Federal Point, Florida.

Hamlin

Thiscultivar

A cultivar is a type of cultivated plant that people have selected for desired traits and when propagated retain those traits. Methods used to propagate cultivars include: division, root and stem cuttings, offsets, grafting, tissue culture ...

was discovered by A. G. Hamlin near Glenwood, Florida, in 1879. The fruit is small, smooth, not highly colored, and juicy, with a pale yellow colored juice, especially in fruits that come from lemon rootstock. The fruit may be seedless, or may contain a number of small seeds. The tree is high-yielding and cold-tolerant and it produces good quality fruit, which is harvested from October to December. It thrives in humid subtropical climates. In cooler, more arid areas, the trees produce edible fruit, but too small for commercial use.

Trees from groves in hammocks

A hammock (from Spanish , borrowed from Taíno and Arawak ) is a sling made of fabric, rope, or netting, suspended between two or more points, used for swinging, sleeping, or resting. It normally consists of one or more cloth panels, or a wove ...

or areas covered with pine forest are budded on sour orange trees, a method that gives a high solids content. On sand, they are grafted on rough lemon rootstock. The Hamlin orange is one of the most popular juice oranges in Florida and replaces the Parson Brown variety as the principal early-season juice orange. This cultivar is now the leading early orange in Florida and, possibly, in the rest of the world.

Other Valencias

* Bahia: grown in Brazil and Uruguay

* Bali: grown in Bali, Indonesia. Larger than other orange

* Belladonna: grown in Italy

* Berna: grown mainly in Spain

* Biondo Comune ("ordinary blond"): widely grown in the Mediterranean basin, especially in North Africa, Egypt, Greece (where it is called "koines"), Italy (where it is also known as "Liscio"), and Spain; it also is called "Beledi" and "Nostrale"; in Italy, this variety ripens in December, earlier than the competing Tarocco varietyMaterial Identification Sheet

* Bahia: grown in Brazil and Uruguay

* Bali: grown in Bali, Indonesia. Larger than other orange

* Belladonna: grown in Italy

* Berna: grown mainly in Spain

* Biondo Comune ("ordinary blond"): widely grown in the Mediterranean basin, especially in North Africa, Egypt, Greece (where it is called "koines"), Italy (where it is also known as "Liscio"), and Spain; it also is called "Beledi" and "Nostrale"; in Italy, this variety ripens in December, earlier than the competing Tarocco varietyMaterial Identification SheetWebcapua.com. Retrieved on 2011-10-02 (in French). * Biondo Riccio: grown in Italy * Byeonggyul: grown in Jeju Island, South Korea * Cadanera: a seedless orange of excellent flavor grown in Algeria, Morocco, and Spain; it begins to ripen in November and is known by a wide variety of trade names, such as Cadena Fina, Cadena sin Jueso, Precoce de Valence ("early from Valencia"), Precoce des Canaries, and Valence san Pepins ("seedless Valencia"); it was first grown in Spain in 1870 * Calabrese or Calabrese Ovale: grown in Italy * Carvalhal: grown in Portugal * Castellana: grown in Spain * Charmute: grown in Brazil * Cherry Orange: grown in southern China and Japan * Clanor: grown in South Africa * Dom João: grown in Portugal * Fukuhara: grown in Japan * Gardner: grown in Florida, this mid-season orange ripens around the beginning of February, approximately the same time as the Midsweet variety; Gardner is about as hardy as Sunstar and Midsweet * Homosassa: grown in Florida *

Jaffa orange

The Jaffa orange (Arabic: برتقال يافا), also known by their Arabic name, Shamouti orange, is an orange variety with few seeds and a tough skin that makes it particularly suitable for export.

Developed by Arab farmers in the mid-19t ...

: grown in the Middle East, also known as "Shamouti"

* Jincheng: the most popular orange in China

* Joppa: grown in South Africa and Texas

* Khettmali: grown in Israel and Lebanon

* Kona: a type of Valencia orange introduced in Hawaii in 1792 by Captain George Vancouver; for many decades in the nineteenth century, these oranges were the leading export from the Kona district on the Big Island of Hawaii; in Kailua-Kona, some of the original stock still bears fruit

* Lima: grown in Brazil

* Lue Gim Gong: grown in Florida, is an early scion developed by Lue Gim Gong

Lue Gim Gong (; August 24, 1857 – June 3, 1925) was a Chinese-American horticulturalist. Known as "The Citrus Wizard", he is remembered for his contribution to the orange-growing industry in Florida.

Life

Born in Taishan, Guangdong, Qing dy ...

, a Chinese immigrant known as the "Citrus Genius"; in 1888, Lue cross-pollinated

Pollination is the transfer of pollen from an anther of a plant to the stigma of a plant, later enabling fertilisation and the production of seeds, most often by an animal or by wind. Pollinating agents can be animals such as insects, birds, a ...

two orange varieties – the Hart's late Valencia and the Mediterranean Sweet – and obtained a fruit both sweet and frost-tolerant; this variety was propagated at the Glen St. Mary Nursery, which in 1911 received the Silver Wilder Medal by the American Pomological Society; originally considered a hybrid, the Lue Gim Gong orange was later found to be a nucellar seedling of the Valencia type, which is properly called Lue Gim Gong; since 2006, the Lue Gim Gong variety is grown in Florida, although sold under the general name Valencia

* Macetera: grown in Spain, it is known for its unique flavor

* Malta: grown in Pakistan

* Maltaise Blonde: grown in north Africa

* Maltaise Ovale: grown in South Africa and in California under the names of Garey's or California Mediterranean Sweet

* Marrs: grown in Texas, California and Iran, it is relatively low in acid

* Medan: grown in Medan, Indonesia

* Midsweet: grown in Florida, it is a newer scion similar to the Hamlin and Pineapple varieties, it is hardier than Pineapple and ripens later; the fruit production and quality are similar to those of the Hamlin, but the juice has a deeper color

* Moro Tarocco: grown in Italy, it is oval, resembles a tangelo, and has a distinctive caramel-colored endocarp; this color is the result of a pigment called anthocarpium, not usually found in citruses, but common in red fruits and flowers; the original mutation occurred in Sicily in the seventeenth century

* Narinja: grown in Andhra, South India

* Parson Brown: grown in Florida, Mexico, and Turkey, it once was a widely grown Florida juice orange, its popularity has declined since new varieties with more juice, better yield, and higher acid and sugar content have been developed; it originated as a chance seedling in Florida in 1865; its fruits are round, medium large, have a thick, pebbly peel and contain 10 to 30 seeds; it still is grown because it is the earliest maturing fruit in the United States, usually maturing in early September in the Valley district of Texas, and from early October to January in Florida;Ferguson, James J

* Malta: grown in Pakistan

* Maltaise Blonde: grown in north Africa

* Maltaise Ovale: grown in South Africa and in California under the names of Garey's or California Mediterranean Sweet

* Marrs: grown in Texas, California and Iran, it is relatively low in acid

* Medan: grown in Medan, Indonesia

* Midsweet: grown in Florida, it is a newer scion similar to the Hamlin and Pineapple varieties, it is hardier than Pineapple and ripens later; the fruit production and quality are similar to those of the Hamlin, but the juice has a deeper color

* Moro Tarocco: grown in Italy, it is oval, resembles a tangelo, and has a distinctive caramel-colored endocarp; this color is the result of a pigment called anthocarpium, not usually found in citruses, but common in red fruits and flowers; the original mutation occurred in Sicily in the seventeenth century

* Narinja: grown in Andhra, South India

* Parson Brown: grown in Florida, Mexico, and Turkey, it once was a widely grown Florida juice orange, its popularity has declined since new varieties with more juice, better yield, and higher acid and sugar content have been developed; it originated as a chance seedling in Florida in 1865; its fruits are round, medium large, have a thick, pebbly peel and contain 10 to 30 seeds; it still is grown because it is the earliest maturing fruit in the United States, usually maturing in early September in the Valley district of Texas, and from early October to January in Florida;Ferguson, James JYour Florida Dooryard Citrus Guide – Appendices, Definitions and Glossary

edis.ifas.ufl.edu its peel and juice color are poor, as is the quality of its juice * Pera: grown in Brazil, it is very popular in the Brazilian citrus industry and yielded 7.5 million metric tons in 2005 * Pera Coroa: grown in Brazil * Pera Natal: grown in Brazil * Pera Rio: grown in Brazil * Pineapple: grown in North and South America and India * Pontianak: oval-shaped orange grown especially in Pontianak, Indonesia * Premier: grown in South Africa * Rhode Red: is a mutation of the Valencia orange, but the color of its flesh is more intense; it has more juice, and less acidity and vitamin C than the Valencia; it was discovered by Paul Rhode in 1955 in a grove near Sebring, Florida * Roble: it was first shipped from Spain in 1851 by Joseph Roble to his homestead in what is now Roble's Park in Tampa, Florida; it is known for its high sugar content * Queen: grown in South Africa * Salustiana: grown in North Africa * Sathgudi: grown in Tamil Nadu, South India * Seleta, Selecta: grown in Australia and Brazil, it is high in acid * Shamouti Masry: grown in Egypt; it is a richer variety of Shamouti * Sunstar: grown in Florida, this newer cultivar ripens in mid-season (December to March) and it is more resistant to cold and fruit-drop than the competing Pineapple variety; the color of its juice is darker than that of the competing Hamlin * Tomango: grown in South Africa * Verna: grown in Algeria, Mexico, Morocco, and Spain * Vicieda: grown in Algeria, Morocco, and Spain * Westin: grown in Brazil * Xã Đoài orange: grown in Vietnam

Navel

Navel oranges are characterized by the growth of a second fruit at theapex

The apex is the highest point of something. The word may also refer to:

Arts and media Fictional entities

* Apex (comics), a teenaged super villainess in the Marvel Universe

* Ape-X, a super-intelligent ape in the Squadron Supreme universe

*Apex, ...

, which protrudes slightly and resembles a human navel. They are primarily grown for human consumption for various reasons: their thicker skin makes them easy to peel, they are less juicy and their bitterness – a result of the high concentrations of limonin

Limonin is a limonoid, and a bitter, white, crystalline substance found in citrus and other plants. It is also known as limonoate D-ring-lactone and limonoic acid di-delta-lactone. Chemically, it is a member of the class of compounds known as fu ...

and other limonoid

Limonoids are phytochemicals of the triterpenoid class which are abundant in sweet or sour-scented citrus fruit and other plants of the families Cucurbitaceae, Rutaceae, and Meliaceae. Certain limonoids are antifeedants such as azadirachtin from ...

s – renders them less suitable for juice. Their widespread distribution and long harvest period have made navel oranges very popular. In the United States, they are available from November to April, with peak supplies in January, February, and March.

According to a 1917 study by Palemon Dorsett, Archibald Dixon Shamel and Wilson Popenoe

Frederick Wilson Popenoe (March 9, 1892 – June 20, 1975) was an American Department of Agriculture employee and plant explorer. From 1916 to 1924, Popenoe explored Latin America to look for new strains of avocados. He reported his adventure ...

of the United States Department of Agriculture

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) is the federal executive department responsible for developing and executing federal laws related to farming, forestry, rural economic development, and food. It aims to meet the needs of com ...

(USDA), a single mutation in a Selecta orange tree planted on the grounds of a monastery in Bahia, Brazil, probably yielded the first navel orange between 1810 and 1820. Nevertheless, a researcher at the University of California, Riverside, has suggested that the parent variety was more likely the Portuguese navel orange (''Umbigo''), described by Antoine Risso

Giuseppe Antonio Risso (8 April 1777 – 25 August 1845), called Antoine Risso, was a Niçard and natural history, naturalist.

Risso was born in the city of Nice in the Duchy of Savoy, and studied under Giovanni Battista Balbis. He published ' (1 ...

and Pierre Antoine Poiteau in their book ''Histoire naturelle des orangers'' ("Natural History of Orange Trees", 1818–1822). The mutation caused the orange to develop a second fruit at its base, opposite the stem, embedded within the peel of the primary orange. Navel oranges were introduced in Australia in 1824 and in Florida in 1835. In 1873, Eliza Tibbets planted two cuttings of the original tree in Riverside, California

Riverside is a city in and the county seat of Riverside County, California, United States, in the Inland Empire metropolitan area. It is named for its location beside the Santa Ana River. It is the most populous city in the Inland Empire an ...

, where the fruit became known as "Washington". This cultivar was very successful, and rapidly spread to other countries. Because the mutation left the fruit seedless, therefore sterile, the only method to cultivate navel oranges was to graft cuttings onto other varieties of citrus trees. The California Citrus State Historic Park and the Orcutt Ranch Horticulture Center preserve the history of navel oranges in Riverside.

Today, navel oranges continue to be propagated through cutting

Cutting is the separation or opening of a physical object, into two or more portions, through the application of an acutely directed force.

Implements commonly used for wikt:cut, cutting are the knife and saw, or in medicine and science the scal ...

and grafting. This does not allow for the usual selective breeding

Selective breeding (also called artificial selection) is the process by which humans use animal breeding and plant breeding to selectively develop particular phenotypic traits (characteristics) by choosing which typically animal or plant m ...

methodologies, and so all navel oranges can be considered fruits from that single, nearly 200-year-old tree: they have exactly the same genetic make-up as the original tree and are clones

Clone or Clones or Cloning or Cloned or The Clone may refer to:

Places

* Clones, County Fermanagh

* Clones, County Monaghan, a town in Ireland

Biology

* Clone (B-cell), a lymphocyte clone, the massive presence of which may indicate a pathologi ...

. This case is similar to that of the common yellow seedless banana, the Cavendish

Cavendish may refer to:

People

* The House of Cavendish, a British aristocratic family

* Margaret Cavendish (1623–1673), British poet, philosopher, and scientist

* Cavendish (author) (1831–1899), pen name of Henry Jones, English au ...

, or that of the Granny Smith

The Granny Smith, also known as a green apple or sour apple, is an apple cultivar which originated in Australia in 1868. It is named after Maria Ann Smith, who propagated the cultivar from a chance seedling. The tree is thought to be a hybrid ...

apple. On rare occasions, however, further mutations can lead to new varieties.

Cara cara

Cara cara oranges (also called "red navel") are a type of navel orange grown mainly in

Cara cara oranges (also called "red navel") are a type of navel orange grown mainly in Venezuela

Venezuela (; ), officially the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela ( es, link=no, República Bolivariana de Venezuela), is a country on the northern coast of South America, consisting of a continental landmass and many islands and islets in th ...

, South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the Atlantic Ocean, South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the ...

and in California's San Joaquin Valley

The San Joaquin Valley ( ; es, Valle de San Joaquín) is the area of the Central Valley of the U.S. state of California that lies south of the Sacramento–San Joaquin River Delta and is drained by the San Joaquin River. It comprises seven ...

. They are sweet and comparatively low in acid, with a bright orange rind similar to that of other navels, but their flesh is distinctively pinkish red. It is believed that they have originated as a cross between the Washington navel and the Brazilian Bahia navel, and they were discovered at the Hacienda Cara Cara in Valencia

Valencia ( va, València) is the capital of the autonomous community of Valencia and the third-most populated municipality in Spain, with 791,413 inhabitants. It is also the capital of the province of the same name. The wider urban area al ...

, Venezuela, in 1976.Cara Cara navel orangeUniversity of California, Riverside South African cara caras are ready for market in early August, while Venezuelan fruits arrive in October and Californian fruits in late November.

Other Navels

* Bahianinha or Bahia * Dream Navel * Late Navel * Washington or California NavelBlood

Blood oranges are a natural mutation of ''C. sinensis'', although today the majority of them are hybrids. High concentrations of anthocyanin give the rind, flesh, and juice of the fruit their characteristic dark red color. Blood oranges were first discovered and cultivated in

Blood oranges are a natural mutation of ''C. sinensis'', although today the majority of them are hybrids. High concentrations of anthocyanin give the rind, flesh, and juice of the fruit their characteristic dark red color. Blood oranges were first discovered and cultivated in Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

in the fifteenth century. Since then they have spread worldwide, but are grown especially in Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

and Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

under the names of ''sanguina'' and ''sanguinella'', respectively.

The blood orange, with its distinct color and flavor, is generally considered favorably as a juice, and has found a niche as an ingredient variation in traditional Seville marmalade.

Maltese: a small and highly colored variety, generally thought to have originated in Italy as a mutation and cultivated there for centuries. It also is grown extensively in southern Spain and Malta. It is used in sorbets and other desserts due to its rich burgundy color. Moro, originally from Sicily, it is common throughout Italy. This medium-sized fruit has a relatively long harvest, which lasts from December to April. Sanguinelli, a mutant of the Doble Fina, was discovered in 1929 in Almenara, in the Castellón province of Spain. It is cultivated in Sicily. Tarocco is relatively new variety developed in Italy. It begins to ripen in late January.

Acidless

Acidless oranges are an early-season fruit with very low levels of acid. They also are called "sweet" oranges in the United States, with similar names in other countries: ''douce'' in France, ''sucrena'' in Spain, ''dolce'' or ''maltese'' in Italy, ''meski'' in North Africa and the Near East (where they are especially popular), ''şeker portakal'' ("sugar orange") in Turkey, ''succari'' in Egypt, and ''lima'' in Brazil. The lack of acid, which protects orange juice against spoilage in other groups, renders them generally unfit for processing as juice, so they are primarily eaten. They remain profitable in areas of local consumption, but rapid spoilage renders them unsuitable for export to major population centres of Europe, Asia, or the United States.Hybrid

Sweet oranges have also given rise to a range of hybrids, notably the grapefruit, which arose from a sweet orange x pomelo backcross. A spontaneous backcross of the grapefruit and sweet orange then resulted in the orangelo. Spontaneous and engineered backcrosses between the sweet orange and mandarin oranges or tangerines has produced a group collectively known astangor

The tangor (''C. reticulata'' × ''C. sinensis'') is a citrus fruit hybrid of the mandarin orange (''Citrus reticulata'') and the sweet orange (''Citrus sinensis''). The name "tangor" is a formation from the "tang" of tangerine and the "or" of ...

s, which includes the clementine

A clementine (''Citrus × clementina'') is a tangor, a citrus fruit hybrid between a willowleaf mandarin orange ( ''C.'' × ''deliciosa'') and a sweet orange (''C. × sinensis''), named in honor of Clément Rodier, a French missionary who fir ...

and Murcott. More complex crosses have also been produced. The so-called Ambersweet orange is actually a complex sweet orange x (Orlando tangelo x clementine) hybrid, legally designated a sweet orange in the United States so it can be used in orange juices. The citrange

The citrange (a portmanteau of ''citrus'' and ''orange'') is a citrus hybrid of the sweet orange and the trifoliate orange.

The purpose of this cross was to attempt to create a cold hardy citrus tree (which is the nature of a trifoliate), with d ...

s are a group of intergeneric sweet orange x trifoliate orange hybrids.

Attributes

Sensory factors

aldehyde

In organic chemistry, an aldehyde () is an organic compound containing a functional group with the structure . The functional group itself (without the "R" side chain) can be referred to as an aldehyde but can also be classified as a formyl grou ...

s, ketones, terpene

Terpenes () are a class of natural products consisting of compounds with the formula (C5H8)n for n > 1. Comprising more than 30,000 compounds, these unsaturated hydrocarbons are produced predominantly by plants, particularly conifers. Terpenes ...

s, and esters. Bitter limonoid

Limonoids are phytochemicals of the triterpenoid class which are abundant in sweet or sour-scented citrus fruit and other plants of the families Cucurbitaceae, Rutaceae, and Meliaceae. Certain limonoids are antifeedants such as azadirachtin from ...

compounds, such as limonin

Limonin is a limonoid, and a bitter, white, crystalline substance found in citrus and other plants. It is also known as limonoate D-ring-lactone and limonoic acid di-delta-lactone. Chemically, it is a member of the class of compounds known as fu ...

, decrease gradually during development, whereas volatile aroma compounds tend to peak in mid– to late–season development. Taste quality tends to improve later in harvests when there is a higher sugar/acid ratio with less bitterness. As a citrus fruit, the orange is acidic, with pH levels ranging from 2.9 to 4.0.

Sensory qualities vary according to genetic background, environmental conditions during development, ripeness at harvest, postharvest conditions, and storage duration.

Nutritional value and phytochemicals

Orange flesh is 87% water, 12%carbohydrate

In organic chemistry, a carbohydrate () is a biomolecule consisting of carbon (C), hydrogen (H) and oxygen (O) atoms, usually with a hydrogen–oxygen atom ratio of 2:1 (as in water) and thus with the empirical formula (where ''m'' may or m ...

s, 1% protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, res ...

, and contains negligible fat

In nutrition, biology, and chemistry, fat usually means any ester of fatty acids, or a mixture of such compounds, most commonly those that occur in living beings or in food.

The term often refers specifically to triglycerides (triple est ...

(see table). As a 100 gram reference amount, orange flesh provides 47 calories, and is a rich source of vitamin C, providing 64% of the Daily Value

The Reference Daily Intake (RDI) used in nutrition labeling on food and dietary supplement products in the U.S. and Canada is the daily intake level of a nutrient that is considered to be sufficient to meet the requirements of 97–98% of healthy ...

. No other micronutrients

Micronutrients are essential dietary elements required by organisms in varying quantities throughout life to orchestrate a range of physiological functions to maintain health. Micronutrient requirements differ between organisms; for example, huma ...

are present in significant amounts (see table).

Oranges contain diverse phytochemicals, including carotenoids ( beta-carotene, lutein and beta-cryptoxanthin), flavonoids (e.g. naringenin) and numerous volatile organic compounds

Volatile organic compounds (VOCs) are organic compounds that have a high vapour pressure at room temperature. High vapor pressure correlates with a low boiling point, which relates to the number of the sample's molecules in the surrounding air, a t ...

producing orange aroma

An odor (American English) or odour ( Commonwealth English; see spelling differences) is caused by one or more volatilized chemical compounds that are generally found in low concentrations that humans and animals can perceive via their se ...

, including aldehyde

In organic chemistry, an aldehyde () is an organic compound containing a functional group with the structure . The functional group itself (without the "R" side chain) can be referred to as an aldehyde but can also be classified as a formyl grou ...

s, esters, terpene

Terpenes () are a class of natural products consisting of compounds with the formula (C5H8)n for n > 1. Comprising more than 30,000 compounds, these unsaturated hydrocarbons are produced predominantly by plants, particularly conifers. Terpenes ...

s, alcohols, and ketones.

Orange juice contains only about one-fifth the citric acid of

Orange juice contains only about one-fifth the citric acid of lime

Lime commonly refers to:

* Lime (fruit), a green citrus fruit

* Lime (material), inorganic materials containing calcium, usually calcium oxide or calcium hydroxide

* Lime (color), a color between yellow and green

Lime may also refer to:

Botany ...

or lemon

The lemon (''Citrus limon'') is a species of small evergreen trees in the flowering plant family Rutaceae, native to Asia, primarily Northeast India (Assam), Northern Myanmar or China.

The tree's ellipsoidal yellow fruit is used for culin ...

juice (which contain about 47 g/L).

Grading

TheUnited States Department of Agriculture

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) is the federal executive department responsible for developing and executing federal laws related to farming, forestry, rural economic development, and food. It aims to meet the needs of com ...

(USDA) has established the following grades for Florida oranges, which primarily apply to oranges sold as fresh fruit: US Fancy, US No. 1 Bright, US No. 1, US No. 1 Golden, US No. 1 Bronze, US No. 1 Russet, US No. 2 Bright, US No. 2, US No. 2 Russet, and US No. 3.United States Standards for Grades of Florida Oranges and Tangelos(USDA; February, 1997) The general characteristics graded are color (both hue and uniformity), firmness, maturity, varietal characteristics, texture, and shape. ''Fancy'', the highest grade, requires the highest grade of color and an absence of blemishes, while the terms ''Bright'', ''Golden'', ''Bronze'', and ''Russet'' concern solely discoloration. Grade numbers are determined by the amount of unsightly blemishes on the skin and firmness of the fruit that do not affect consumer safety. The USDA separates blemishes into three categories: # General blemishes: ammoniation, buckskin, caked melanose, creasing, decay, scab, split navels, sprayburn, undeveloped segments, unhealed segments, and wormy fruit # Injuries to fruit: bruises, green spots, oil spots, rough, wide, or protruding navels, scale, scars, skin breakdown, and thorn scratches # Damage caused by dirt or other foreign material, disease, dryness, or mushy condition, hail, insects, riciness or woodiness, and sunburn. The USDA uses a separate grading system for oranges used for juice because appearance and texture are irrelevant in this case. There are only two grades: US Grade AA Juice and US Grade A Juice, which are given to the oranges before processing. Juice grades are determined by three factors: # The juiciness of the orange # The amount of solids in the juice (at least 10% solids are required for the AA grade) # The proportion of anhydric citric acid in fruit solids

Cultivation

Climate

Like most citrus plants, oranges do well under moderate temperatures—between —and require considerable amounts of sunshine and water. It has been suggested the use of water resources by the citrus industry in the Middle East is a contributing factor to the desiccation of the region. Another significant element in the full development of the fruit is the temperature variation between summer and winter and, between day and night. In cooler climates, oranges can be grown indoors.

As oranges are sensitive to frost, there are different methods to prevent frost damage to crops and trees when subfreezing temperatures are expected. A common process is to spray the trees with water so as to cover them with a thin layer of ice that will stay just ''at'' the freezing point, insulating them even if air temperatures drop far lower. This is because water continues to lose heat as long as the environment is colder than it is, and so the water turning to ice in the environment cannot damage the trees. This practice, however, offers protection only for a very short time. Another procedure is burning fuel oil in

Like most citrus plants, oranges do well under moderate temperatures—between —and require considerable amounts of sunshine and water. It has been suggested the use of water resources by the citrus industry in the Middle East is a contributing factor to the desiccation of the region. Another significant element in the full development of the fruit is the temperature variation between summer and winter and, between day and night. In cooler climates, oranges can be grown indoors.

As oranges are sensitive to frost, there are different methods to prevent frost damage to crops and trees when subfreezing temperatures are expected. A common process is to spray the trees with water so as to cover them with a thin layer of ice that will stay just ''at'' the freezing point, insulating them even if air temperatures drop far lower. This is because water continues to lose heat as long as the environment is colder than it is, and so the water turning to ice in the environment cannot damage the trees. This practice, however, offers protection only for a very short time. Another procedure is burning fuel oil in smudge pot

A smudge pot (also known as a choofa or orchard heater) is an oil-burning device used to prevent frost on fruit trees. Usually a smudge pot has a large round base with a chimney coming out of the middle of the base. The smudge pot is placed betw ...

s put between the trees. These devices burn with a great deal of particulate emission, so condensation of water vapour on the particulate soot prevents condensation on plants and raises the air temperature very slightly. Smudge pots were developed for the first time after a disastrous freeze in Southern California in January 1913 destroyed a whole crop.

Propagation

It is possible to grow orange trees directly from seeds, but they may be infertile or produce fruit that may be different from its parent. For the seed of a commercial orange to grow, it must be kept moist at all times. One approach is placing the seeds between two sheets of damp paper towel until they germinate and then planting them, although many cultivators just set the seeds straight into the soil. Commercially grown orange trees are propagated asexually by grafting a maturecultivar

A cultivar is a type of cultivated plant that people have selected for desired traits and when propagated retain those traits. Methods used to propagate cultivars include: division, root and stem cuttings, offsets, grafting, tissue culture ...

onto a suitable seedling

A seedling is a young sporophyte developing out of a plant embryo from a seed. Seedling development starts with germination of the seed. A typical young seedling consists of three main parts: the radicle (embryonic root), the hypocotyl (embryo ...

rootstock

A rootstock is part of a plant, often an underground part, from which new above-ground growth can be produced. It could also be described as a stem with a well developed root system, to which a bud from another plant is grafted. It can refer to a ...

to ensure the same yield, identical fruit characteristics, and resistance to diseases throughout the years. Propagation involves two stages: first, a rootstock is grown from seed. Then, when it is approximately one year old, the leafy top is cut off and a bud

In botany, a bud is an undeveloped or embryonic shoot and normally occurs in the axil of a leaf or at the tip of a stem. Once formed, a bud may remain for some time in a dormant condition, or it may form a shoot immediately. Buds may be spec ...

taken from a specific scion

Scion may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Fictional entities

*Scion, a playable class in the game '' Path of Exile'' (2013)

*Atlantean Scion, a device in the ''Tomb Raider'' video game series

*Scions, an alien race in the video game ''B ...

variety, is grafted into its bark. The scion is what determines the variety of orange, while the rootstock makes the tree resistant to pests and diseases and adaptable to specific soil

Soil, also commonly referred to as earth or dirt

Dirt is an unclean matter, especially when in contact with a person's clothes, skin, or possessions. In such cases, they are said to become dirty.

Common types of dirt include:

* Debri ...

and climatic conditions. Thus, rootstocks influence the rate of growth and have an effect on fruit yield and quality.

Rootstocks must be compatible with the variety inserted into them because otherwise, the tree may decline, be less productive, or die.

Among the several advantages to grafting are that trees mature uniformly and begin to bear fruit earlier than those reproduced by seeds (3 to 4 years in contrast with 6 to 7 years), and that it makes it possible to combine the best attributes of a scion with those of a rootstock.

Harvest

Canopy-shaking mechanical harvesters are being used increasingly in Florida to harvest oranges. Current canopy shaker machines use a series of six-to-seven-foot-long tines to shake the tree canopy at a relatively constant stroke and frequency. Normally, oranges are picked once they are pale orange.Degreening

Oranges must be mature when harvested. In the United States, laws forbid harvesting immature fruit for human consumption in Texas, Arizona, California and Florida. Ripe oranges, however, often have some green or yellow-green color in the skin. Ethylene gas is used to turn green skin to orange. This process is known as "degreening", also called "gassing", "sweating", or "curing". Oranges are non- climacteric fruits and cannot post-harvest ripen internally in response to ethylene gas, though they will de-green externally.Storage

Commercially, oranges can be stored by refrigeration in controlled-atmosphere chambers for up to twelve weeks after harvest. Storage life ultimately depends on cultivar, maturity, pre-harvest conditions, and handling. In stores and markets, however, oranges should be displayed on non-refrigerated shelves.

At home, oranges have a shelf life of about one month. In either case, optimally, they are stored loosely in an open or perforated plastic bag.

Commercially, oranges can be stored by refrigeration in controlled-atmosphere chambers for up to twelve weeks after harvest. Storage life ultimately depends on cultivar, maturity, pre-harvest conditions, and handling. In stores and markets, however, oranges should be displayed on non-refrigerated shelves.

At home, oranges have a shelf life of about one month. In either case, optimally, they are stored loosely in an open or perforated plastic bag.

Pests and diseases

Cottony cushion scale

The first major pest that attacked orange trees in the United States was the cottony cushion scale ('' Icerya purchasi''), imported from Australia to California in 1868. Within 20 years, it wiped out the citrus orchards around Los Angeles, and limited orange growth throughout California. In 1888, the USDA sent Alfred Koebele to Australia to study this scale insect in its native habitat. He brought back with him specimens of ''Novius cardinalis'', an Australian ladybird beetle, and within a decade the pest was controlled.Citrus greening disease