Operation Olympic on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Operation Downfall was the proposed

Operation Olympic, the invasion of Kyūshū, was to begin on "X-Day", which was scheduled for 1 November 1945. The combined Allied naval armada would have been the largest ever assembled, including 42

Operation Olympic, the invasion of Kyūshū, was to begin on "X-Day", which was scheduled for 1 November 1945. The combined Allied naval armada would have been the largest ever assembled, including 42

Meanwhile, the Japanese had their own plans. Initially, they were concerned about an invasion during the summer of 1945. However, the

Meanwhile, the Japanese had their own plans. Initially, they were concerned about an invasion during the summer of 1945. However, the

Retrieved 23 August 2015. However, the IJN lacked enough fuel for further sorties by its capital ships, planning instead to use their anti-aircraft firepower to defend naval installations while docked in port. Despite its inability to conduct large-scale fleet operations, the IJN still maintained a fleet of thousands of warplanes and possessed nearly 2 million personnel in the Home Islands, ensuring it a large role in the coming defensive operation. In addition, Japan had about 100 ''Kōryū''-class

Allied

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

plan for the invasion of the Japanese home islands

The Japanese archipelago (Japanese: 日本列島, ''Nihon rettō'') is a group of 6,852 islands that form the country of Japan, as well as the Russian island of Sakhalin. It extends over from the Sea of Okhotsk in the northeast to the East Chin ...

near the end of World War II End of World War II can refer to:

* End of World War II in Europe

* End of World War II in Asia

World War II officially ended in Asia on September 2, 1945, with the surrender of Japan on the . Before that, the United States dropped two atomic ...

. The planned operation was canceled when Japan surrendered following the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the Soviet declaration of war, and the invasion of Manchuria. The operation had two parts: Operation Olympic and Operation Coronet. Set to begin in November 1945, Operation Olympic was intended to capture the southern third of the southernmost main Japanese island, Kyūshū, with the recently captured island of Okinawa

is a prefecture of Japan. Okinawa Prefecture is the southernmost and westernmost prefecture of Japan, has a population of 1,457,162 (as of 2 February 2020) and a geographic area of 2,281 km2 (880 sq mi).

Naha is the capital and largest city ...

to be used as a staging area. In early 1946 would come Operation Coronet, the planned invasion of the Kantō Plain

The is the largest plain in Japan, and is located in the Kantō region of central Honshū. The total area of 17,000 km2 covers more than half of the region extending over Tokyo, Saitama Prefecture, Kanagawa Prefecture, Chiba Prefecture, ...

, near Tokyo

Tokyo (; ja, 東京, , ), officially the Tokyo Metropolis ( ja, 東京都, label=none, ), is the capital and List of cities in Japan, largest city of Japan. Formerly known as Edo, its metropolitan area () is the most populous in the world, ...

, on the main Japanese island of Honshu

, historically called , is the largest and most populous island of Japan. It is located south of Hokkaidō across the Tsugaru Strait, north of Shikoku across the Inland Sea, and northeast of Kyūshū across the Kanmon Straits. The island se ...

. Airbases on Kyūshū captured in Operation Olympic would allow land-based air support for Operation Coronet. If Downfall had taken place, it would have been the largest amphibious operation

Amphibious warfare is a type of Offensive (military), offensive military operation that today uses naval ships to project ground and air power onto a hostile or potentially hostile shore at a designated landing beach. Through history the opera ...

in history, surpassing D-Day.

Japan's geography made this invasion plan quite obvious to the Japanese as well; they were able to accurately predict the Allied invasion plans and thus adjust their defensive plan, Operation Ketsugō, accordingly. The Japanese planned an all-out defense of Kyūshū, with little left in reserve for any subsequent defense operations. Casualty predictions varied widely, but were extremely high. Depending on the degree to which Japanese civilians would have resisted the invasion, estimates ran up into the millions for Allied casualties.

Planning

Responsibility for the planning of Operation Downfall fell to American commanders Fleet AdmiralChester Nimitz

Chester William Nimitz (; February 24, 1885 – February 20, 1966) was a fleet admiral in the United States Navy. He played a major role in the naval history of World War II as Commander in Chief, US Pacific Fleet, and Commander in C ...

, General of the Army Douglas MacArthur and the Joint Chiefs of Staff

The Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) is the body of the most senior uniformed leaders within the United States Department of Defense, that advises the president of the United States, the secretary of defense, the Homeland Security Council and the ...

—Fleet Admirals Ernest King

Ernest Joseph King (23 November 1878 – 25 June 1956) was an American naval officer who served as Commander in Chief, United States Fleet (COMINCH) and Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) during World War II. As COMINCH-CNO, he directed the U ...

and William D. Leahy

William Daniel Leahy () (May 6, 1875 – July 20, 1959) was an American naval officer who served as the most senior United States military officer on active duty during World War II. He held multiple titles and was at the center of all major ...

, and Generals of the Army George Marshall

George Catlett Marshall Jr. (December 31, 1880 – October 16, 1959) was an American army officer and statesman. He rose through the United States Army to become Chief of Staff of the US Army under Presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt and Harry ...

and Hap Arnold

Henry Harley Arnold (June 25, 1886 – January 15, 1950) was an American general officer holding the ranks of General of the Army and later, General of the Air Force. Arnold was an aviation pioneer, Chief of the Air Corps (1938–1941), ...

(the latter being the commander of the U.S. Army Air Forces).

At the time, the development of the atomic bomb

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bomb ...

was a very closely guarded secret (not even then-Vice President Harry Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. A leader of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 34th vice president from January to April 1945 under Franklin ...

knew of its existence until he became President), known only to a few top officials outside the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

, and the initial planning for the invasion of Japan did not take its existence into consideration. Once the atomic bomb became available, General Marshall envisioned using it to support the invasion if sufficient numbers could be produced in time.

The Pacific War

The Pacific War, sometimes called the Asia–Pacific War, was the theater of World War II that was fought in Asia, the Pacific Ocean, the Indian Ocean, and Oceania. It was geographically the largest theater of the war, including the vast ...

was not under a single Allied commander-in-chief (C-in-C). Allied command was divided into regions: by 1945, for example, Chester Nimitz was the Allied C-in-C Pacific Ocean Areas

Pacific Ocean Areas was a major Allied military command in the Pacific Ocean theater of World War II. It was one of four major Allied commands during the Pacific War, and one of three United States commands in the Asiatic-Pacific Theater. Admir ...

, while Douglas MacArthur was Supreme Allied Commander, South West Pacific Area

South West Pacific Area (SWPA) was the name given to the Allied supreme military command in the South West Pacific Theatre of World War II. It was one of four major Allied commands in the Pacific War. SWPA included the Philippines, Borneo, the ...

, and Admiral Louis Mountbatten was the Supreme Allied Commander, South East Asia Command

South East Asia Command (SEAC) was the body set up to be in overall charge of Allied operations in the South-East Asian Theatre during the Second World War.

History Organisation

The initial supreme commander of the theatre was General Sir A ...

. A unified command was deemed necessary for an invasion of Japan. Interservice rivalry

Interservice rivalry is the rivalry between different branches of a country's armed forces, in other words the competition for limited resources among a nation's land, naval, coastal, air, and space forces. The term also applies to the rivalr ...

over who it should be (the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

wanted Nimitz, but the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cla ...

wanted MacArthur) was so serious that it threatened to derail planning. Ultimately, the Navy partially conceded, and MacArthur was to be given total command of all forces if circumstances made it necessary.

Considerations

The primary considerations that the planners had to deal with were time and casualties—how they could force Japan's surrender as quickly as possible with as few Allied casualties as possible. Prior to theFirst Quebec Conference

The First Quebec Conference, codenamed "Quadrant", was a highly secret military conference held during World War II by the governments of the United Kingdom, Canada, and the United States. It took place in Quebec City on August 17–24, 1943, at ...

, a joint CanadianBritishAmerican planning team produced a plan ("Appreciation and Plan for the Defeat of Japan") which did not call for an invasion of the Japanese Home Islands until 1947–48. The American Joint Chiefs of Staff believed that prolonging the war to such an extent was dangerous for national morale. Instead, at the Quebec conference, the Combined Chiefs of Staff

The Combined Chiefs of Staff (CCS) was the supreme military staff for the United States and Britain during World War II. It set all the major policy decisions for the two nations, subject to the approvals of British Prime Minister Winston Churchil ...

agreed that Japan should be forced to surrender not more than one year after Germany's surrender.

The United States Navy urged the use of a blockade

A blockade is the act of actively preventing a country or region from receiving or sending out food, supplies, weapons, or communications, and sometimes people, by military force.

A blockade differs from an embargo or sanction, which are leg ...

and airpower to bring about Japan's capitulation. They proposed operations to capture airbases in nearby Shanghai

Shanghai (; , , Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ) is one of the four direct-administered municipalities of the People's Republic of China (PRC). The city is located on the southern estuary of the Yangtze River, with the Huangpu River flow ...

, China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

, and Korea

Korea ( ko, 한국, or , ) is a peninsular region in East Asia. Since 1945, it has been divided at or near the 38th parallel, with North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea) comprising its northern half and South Korea (Republic o ...

, which would give the United States Army Air Forces a series of forward airbases from which to bombard Japan into submission. The Army, on the other hand, argued that such a strategy could "prolong the war indefinitely" and expend lives needlessly, and therefore that an invasion was necessary. They supported mounting a large-scale thrust directly against the Japanese homeland, with none of the side operations that the Navy had suggested. Ultimately, the Army's viewpoint prevailed.

Physically, Japan made an imposing target, distant from other landmasses and with very few beaches geographically suitable for sea-borne invasion. Only Kyūshū (the southernmost island of Japan) and the beaches of the Kantō Plain

The is the largest plain in Japan, and is located in the Kantō region of central Honshū. The total area of 17,000 km2 covers more than half of the region extending over Tokyo, Saitama Prefecture, Kanagawa Prefecture, Chiba Prefecture, ...

(both southwest and southeast of Tokyo

Tokyo (; ja, 東京, , ), officially the Tokyo Metropolis ( ja, 東京都, label=none, ), is the capital and List of cities in Japan, largest city of Japan. Formerly known as Edo, its metropolitan area () is the most populous in the world, ...

) were realistic invasion zones. The Allies decided to launch a two-stage invasion. Operation Olympic would attack southern Kyūshū. Airbases would be established, which would give cover for Operation Coronet, the attack on Tokyo Bay

is a bay located in the southern Kantō region of Japan, and spans the coasts of Tokyo, Kanagawa Prefecture, and Chiba Prefecture. Tokyo Bay is connected to the Pacific Ocean by the Uraga Channel. The Tokyo Bay region is both the most populous ...

.

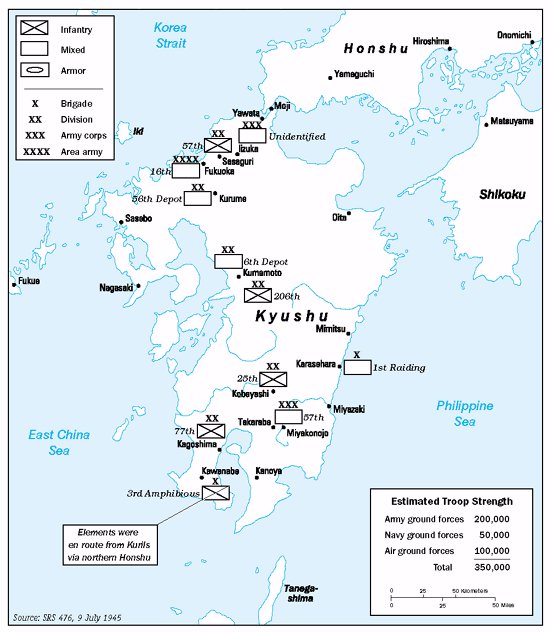

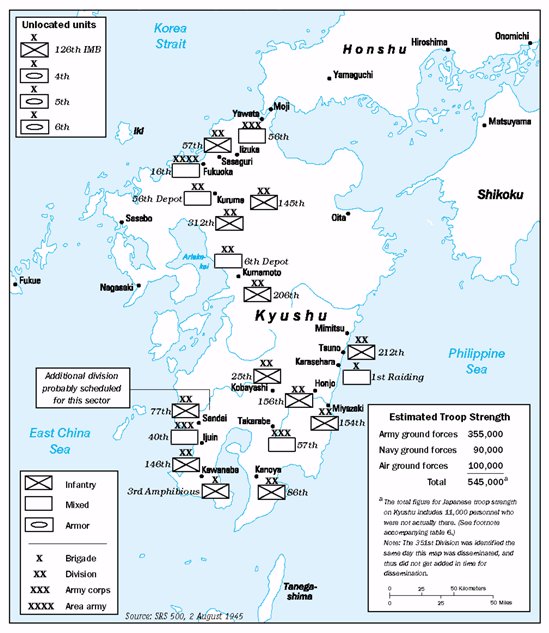

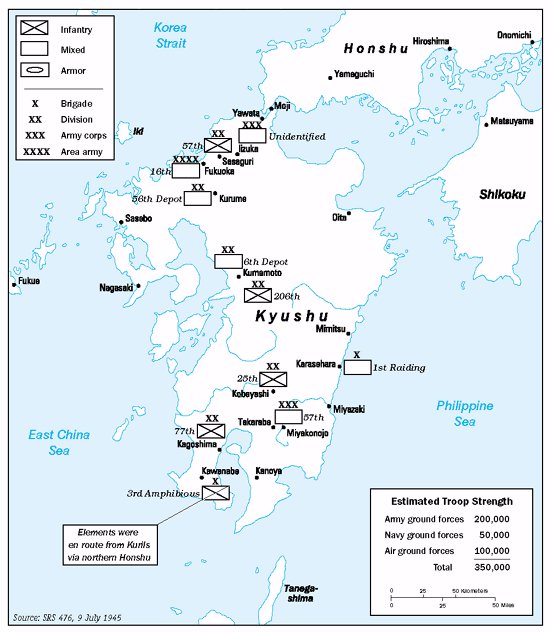

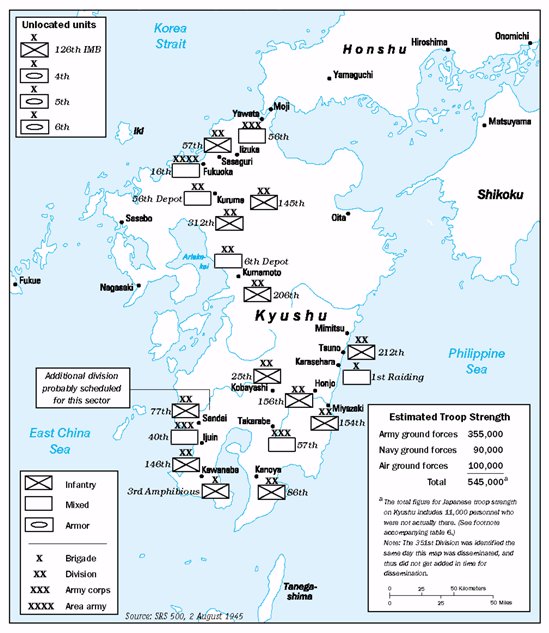

Assumptions

While the geography of Japan was known, the U.S. military planners had to estimate the defending forces that they would face. Based on intelligence available early in 1945, their assumptions included the following: * "That operations in this area will be opposed not only by the available organized military forces of the Empire, but also by a fanatically hostile population." * "That approximately three (3) hostile divisions will be disposed in Southern Kyushu and an additional three (3) in Northern Kyushu at initiation of the Olympic operation." * "That total hostile forces committed against Kyushu operations will not exceed eight (8) to ten (10) divisions and that this level will be speedily attained." * "That approximately twenty-one (21) hostile divisions, including depot divisions, will be on Honshu at the initiation of oronetand that fourteen (14) of these divisions may be employed in the Kanto Plain area." * "That the enemy may withdraw his land-based air forces to the Asiatic Mainland for protection from our neutralizing attacks. That under such circumstances he can possibly amass from 2,000 to 2,500 planes in that area by exercising a rigid economy, and that this force can operate against Kyushu landings by staging through homeland fields."Olympic

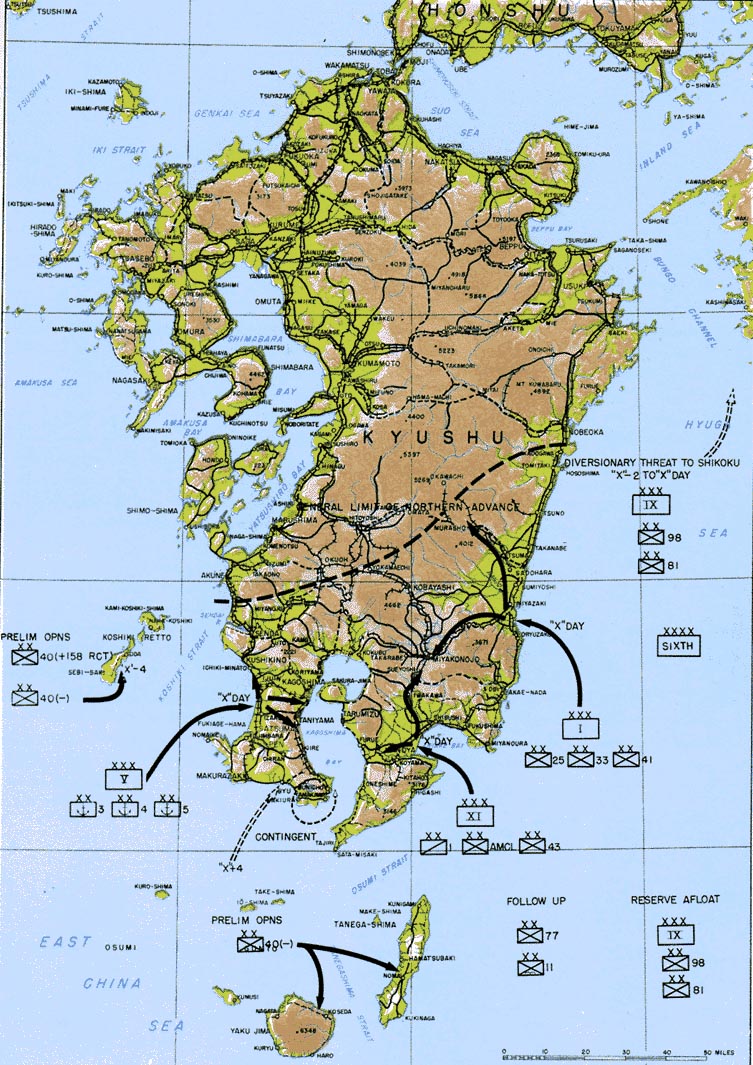

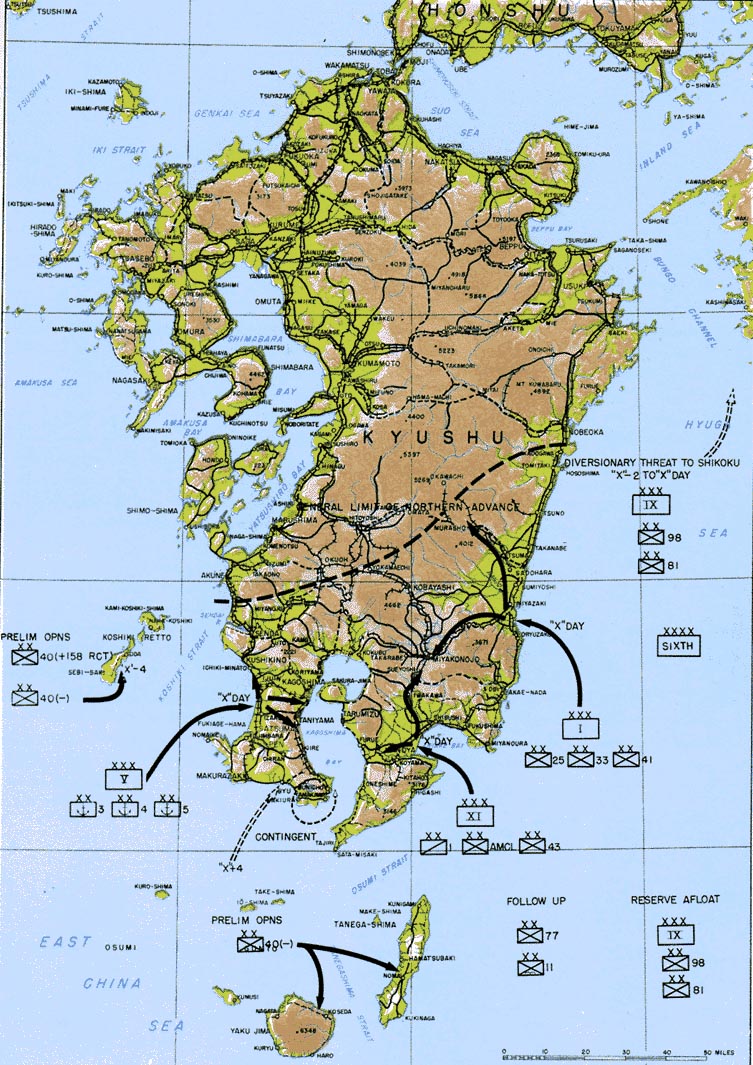

Operation Olympic, the invasion of Kyūshū, was to begin on "X-Day", which was scheduled for 1 November 1945. The combined Allied naval armada would have been the largest ever assembled, including 42

Operation Olympic, the invasion of Kyūshū, was to begin on "X-Day", which was scheduled for 1 November 1945. The combined Allied naval armada would have been the largest ever assembled, including 42 aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and facilities for carrying, arming, deploying, and recovering aircraft. Typically, it is the capital ship of a fleet, as it allows a ...

s, 24 battleship

A battleship is a large armored warship with a main battery consisting of large caliber guns. It dominated naval warfare in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The term ''battleship'' came into use in the late 1880s to describe a type of ...

s, and 400 destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, manoeuvrable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy or battle group and defend them against powerful short range attackers. They were originally developed in ...

s and destroyer escort

Destroyer escort (DE) was the United States Navy mid-20th-century classification for a warship designed with the endurance necessary to escort mid-ocean convoys of merchant marine ships.

Development of the destroyer escort was promoted by th ...

s. Fourteen U.S. divisions and a "division-equivalent" (two regimental combat team

A regimental combat team (RCT) is a provisional major infantry unit which has seen use by branches of the United States Armed Forces. It is formed by augmenting a regular infantry regiment with smaller combat, combat support and combat service ...

s) were scheduled to take part in the initial landings. Using Okinawa

is a prefecture of Japan. Okinawa Prefecture is the southernmost and westernmost prefecture of Japan, has a population of 1,457,162 (as of 2 February 2020) and a geographic area of 2,281 km2 (880 sq mi).

Naha is the capital and largest city ...

as a staging base, the objective would have been to seize the southern portion of Kyūshū. This area would then be used as a further staging point to attack Honshu in Operation Coronet.

Olympic was also to include a deception

Deception or falsehood is an act or statement that misleads, hides the truth, or promotes a belief, concept, or idea that is not true. It is often done for personal gain or advantage. Deception can involve dissimulation, propaganda and sleight o ...

plan, known as Operation Pastel

During World War II, Operation Pastel was the deception plan scheduled to protect Operation Olympic, the planned invasion of southern Japan. Pastel would have falsely portrayed a threat of an American-led invasion against ports in China via at ...

. Pastel was designed to convince the Japanese that the Joint Chiefs had rejected the notion of a direct invasion and instead were going to attempt to encircle and bombard Japan. This would require capturing bases in Formosa, along the Chinese coast, and in the Yellow Sea

The Yellow Sea is a marginal sea of the Western Pacific Ocean located between mainland China and the Korean Peninsula, and can be considered the northwestern part of the East China Sea. It is one of four seas named after common colour terms ...

area.

Tactical air support was to be the responsibility of the Fifth, Seventh

Seventh is the ordinal form of the number seven.

Seventh may refer to:

* Seventh Amendment to the United States Constitution

* A fraction (mathematics), , equal to one of seven equal parts

Film and television

*"The Seventh", a second-season e ...

, and Thirteenth Air Force

The Thirteenth Air Force (Air Forces Pacific) (13 AF) was a numbered air force of the United States Air Force Pacific Air Forces (PACAF). It was last headquartered at Hickam Air Force Base on the island of Oahu, Hawaii. 13 AF has never been sta ...

s. These were responsible for attacking Japanese airfields and transportation arteries on Kyushu and Southern Honshu (e.g. the Kanmon Tunnel) and for gaining and maintaining air superiority over the beaches. The task of strategic bombing fell on the United States Strategic Air Forces in the Pacific (USASTAF)—a formation which comprised the Eighth and Twentieth air forces, as well as the British Tiger Force

Tiger Force was the name of a long-range reconnaissance patrol unit of the 1st Battalion (Airborne), 327th Infantry, 1st Brigade (Separate), 101st Airborne Division, which fought in the Vietnam War from November 1965 to November 1967. The unit ...

. USASTAF and Tiger Force were to remain active through Operation Coronet. The Twentieth Air Force

The Twentieth Air Force (Air Forces Strategic) (20th AF) is a numbered air force of the United States Air Force Global Strike Command (AFGSC). It is headquartered at Francis E. Warren Air Force Base, Wyoming.

20 AF's primary mission is Interco ...

was to have continued its role as the main Allied strategic bomber

A strategic bomber is a medium- to long-range penetration bomber aircraft designed to drop large amounts of air-to-ground weaponry onto a distant target for the purposes of debilitating the enemy's capacity to wage war. Unlike tactical bombers, ...

force used against the Japanese home islands, operating from airfields in the Mariana Islands. Following the end of the war in Europe in May 1945, plans were also made to transfer some of the heavy bomber groups of the veteran Eighth Air Force to airbases on Okinawa to conduct strategic bombing raids in coordination with the Twentieth. The Eighth was to upgrade their B-17 Flying Fortresses and B-24 Liberators to B-29 Superfortress

The Boeing B-29 Superfortress is an American four-engined propeller-driven heavy bomber, designed by Boeing and flown primarily by the United States during World War II and the Korean War. Named in allusion to its predecessor, the B-17 Fl ...

es (the group received its first B-29 on 8 August 1945).

Before the main invasion, the offshore islands of Tanegashima

is one of the Ōsumi Islands belonging to Kagoshima Prefecture, Japan. The island, 444.99 km2 in area, is the second largest of the Ōsumi Islands, and has a population of 33,000 people. Access to the island is by ferry, or by air to Ne ...

, Yakushima

is one of the Ōsumi Islands in Kagoshima Prefecture, Japan. The island, in area, has a population of 13,178. Access to the island is by hydrofoil ferry (7 or 8 times a day from Kagoshima, depending on the season), slow car ferry (once or twic ...

, and the Koshikijima Islands

The in the East China Sea are an island chain located 38 km west of the port city of Ichikikushikino, Kagoshima.

Major islands

Minor islands

All minor islands are currently (as in 2017) uninhabited.

#seems to undergo significant eros ...

were to be taken, starting on X-5. The invasion of Okinawa had demonstrated the value of establishing secure anchorages close at hand, for ships not needed off the landing beaches and for ships damaged by air attack.

Kyūshū was to be invaded by the Sixth United States Army

Sixth Army is a theater army of the United States Army. The Army service component command of United States Southern Command, its area of responsibility includes 31 countries and 15 areas of special sovereignty in Central and South America and ...

at three points: Miyazaki, Ariake Ariake (有明: "daybreak") may refer to:

Places in Japan

*Ariake, Kagoshima, a former town in Kagoshima Prefecture

*Ariake, Kumamoto, a former town in Kumamoto Prefecture

*Ariake, Saga, a former town in Saga Prefecture

*Ariake, Tokyo, a district w ...

, and Kushikino. If a clock were drawn on a map of Kyūshū, these points would roughly correspond to 4, 5, and 7 o'clock, respectively. The 35 landing beaches were all named for automobiles: Austin, Buick

Buick () is a division of the American automobile manufacturer General Motors (GM). Started by automotive pioneer David Dunbar Buick in 1899, it was among the first American marques of automobiles, and was the company that established General ...

, Cadillac

The Cadillac Motor Car Division () is a division of the American automobile manufacturer General Motors (GM) that designs and builds luxury vehicles. Its major markets are the United States, Canada, and China. Cadillac models are distributed i ...

, and so on through to Stutz, Winton, and Zephyr

In European tradition, a zephyr is a light wind or a west wind, named after Zephyrus, the Greek god or personification of the west wind.

Zephyr may also refer to:

Arts and media

Fiction Fiction media

* ''Zephyr'' (film), a 2010 Turkish ...

. With one corps

Corps (; plural ''corps'' ; from French , from the Latin "body") is a term used for several different kinds of organization. A military innovation by Napoleon I, the formation was first named as such in 1805. The size of a corps varies great ...

assigned to each landing, the invasion planners assumed that the Americans would outnumber the Japanese by roughly three to one. In early 1945, Miyazaki was virtually undefended, while Ariake, with its good nearby harbor, was heavily defended.

The invasion was not intended to conquer the entire island, just the southernmost third of it, as indicated by the dashed line on the map labeled "general limit of northern advance". Southern Kyūshū would offer a staging ground and a valuable airbase for Operation Coronet.

After the name Operation Olympic was compromised by being sent out in unsecured code, the name Operation Majestic was adopted.

Coronet

Operation Coronet, the invasion ofHonshu

, historically called , is the largest and most populous island of Japan. It is located south of Hokkaidō across the Tsugaru Strait, north of Shikoku across the Inland Sea, and northeast of Kyūshū across the Kanmon Straits. The island se ...

at the Kantō Plain

The is the largest plain in Japan, and is located in the Kantō region of central Honshū. The total area of 17,000 km2 covers more than half of the region extending over Tokyo, Saitama Prefecture, Kanagawa Prefecture, Chiba Prefecture, ...

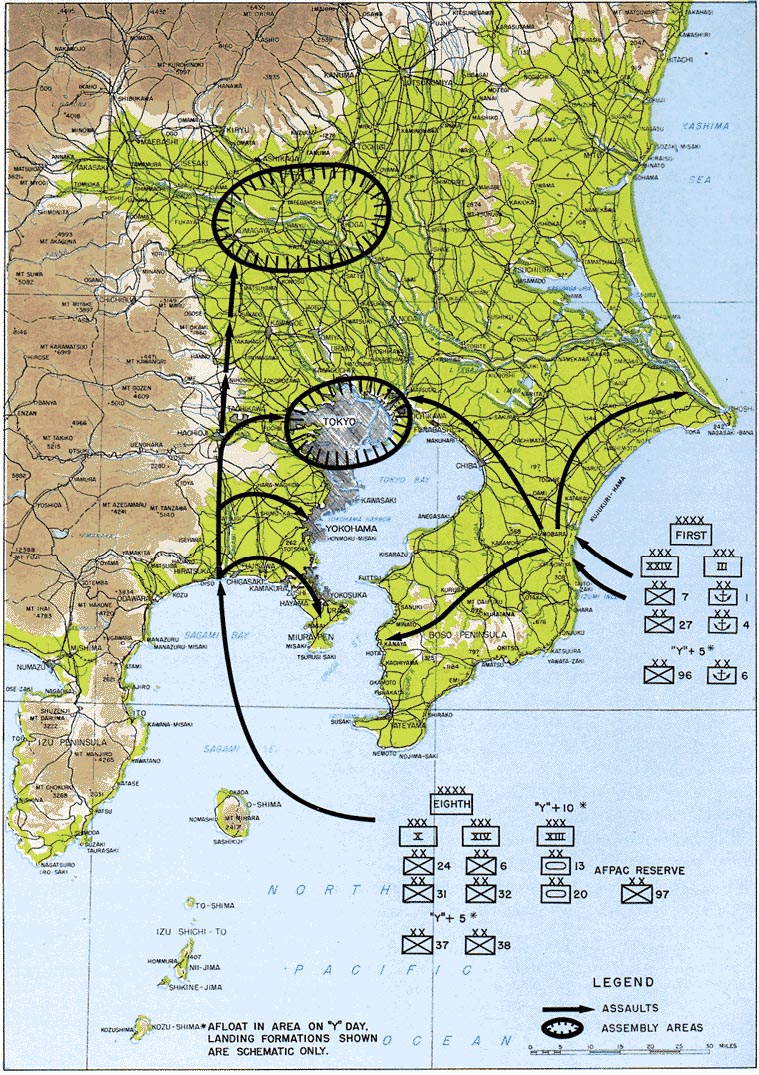

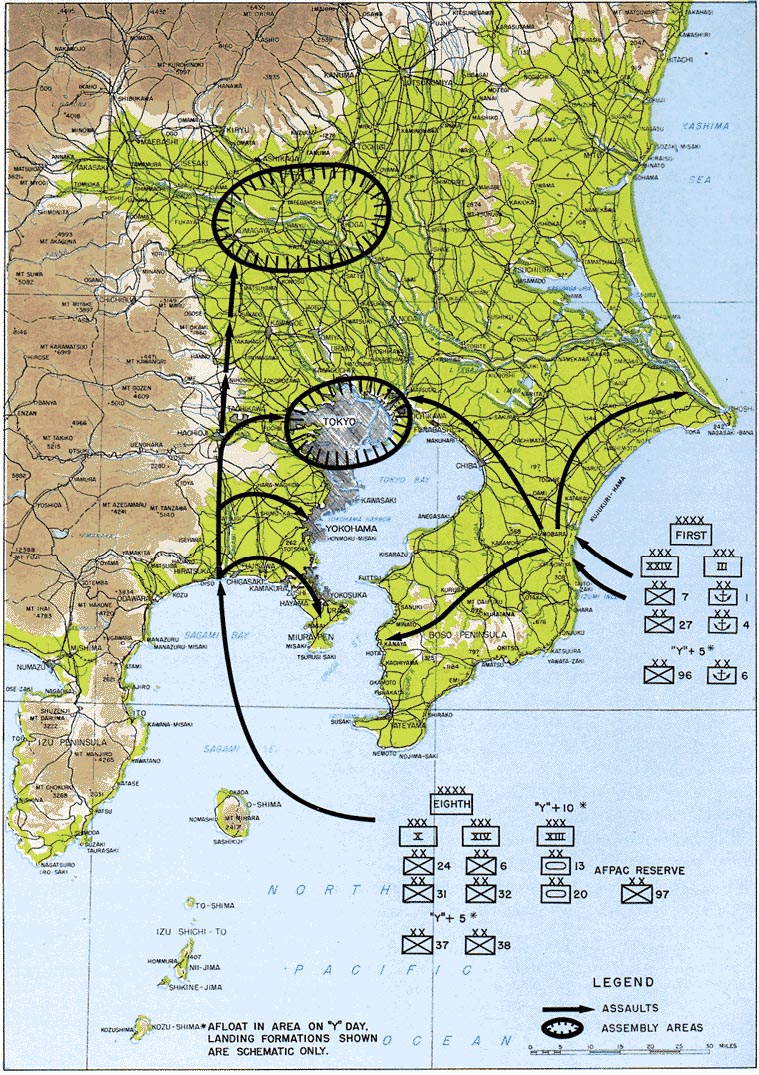

south of the capital, was to begin on "Y-Day", which was tentatively scheduled for 1 March 1946. Coronet would have been even larger than Olympic, with up to 45 U.S. divisions assigned for both the initial landing and follow-up. (The Overlord invasion of Normandy, by comparison, deployed 12 divisions in the initial landings.) In the initial stage, the First Army would have invaded at Kujūkuri Beach

is a sandy beach that occupies much of the northeast coast of the Bōsō Peninsula in Chiba Prefecture, Japan. The beach is approximately long, making it the second longest beach in Japan. Kujūkuri Beach is a popular swimming and surfing dest ...

, on the Bōsō Peninsula

The is a peninsula that encompasses the entirety of Chiba Prefecture on Honshu, the largest island of Japan. It is part of the Greater Tokyo Area. It forms the eastern edge of Tokyo Bay, separating it from the Pacific Ocean. The peninsula covers ...

, while the Eighth Army invaded at Hiratsuka

260px, Hiratsuka City Hall

is a city located in Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan. , the city had an estimated population of 257,316 and a population density of 3800 persons per km². The total area of the city is .

Geography

Hiratsuka is located ...

, on Sagami Bay

lies south of Kanagawa Prefecture in Honshu, central Japan, contained within the scope of the Miura Peninsula, in Kanagawa, to the east, the Izu Peninsula, in Shizuoka Prefecture, to the west, and the Shōnan coastline to the north, while th ...

; these armies would have comprised 25 divisions between them. Later, a follow-up force of up to 20 additional U.S. divisions and up to 5 or more British Commonwealth divisions would have landed as reinforcements. The Allied forces would then have driven north and inland, encircling Tokyo and pressing on toward Nagano.

Redeployment

Olympic was to be mounted with resources already present in the Pacific, including theBritish Pacific Fleet

The British Pacific Fleet (BPF) was a Royal Navy formation that saw action against Japan during the Second World War. The fleet was composed of empire naval vessels. The BPF formally came into being on 22 November 1944 from the remaining ships o ...

, a Commonwealth formation that included at least eighteen aircraft carriers (providing 25% of the Allied air power) and four battleships.

Tiger Force

Tiger Force was the name of a long-range reconnaissance patrol unit of the 1st Battalion (Airborne), 327th Infantry, 1st Brigade (Separate), 101st Airborne Division, which fought in the Vietnam War from November 1965 to November 1967. The unit ...

, a joint Commonwealth long-range heavy bomber

Heavy bombers are bomber aircraft capable of delivering the largest payload of air-to-ground weaponry (usually bombs) and longest range (takeoff to landing) of their era. Archetypal heavy bombers have therefore usually been among the larges ...

unit, was to be transferred from RAF

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and ...

, RAAF

"Through Adversity to the Stars"

, colours =

, colours_label =

, march =

, mascot =

, anniversaries = RAAF Anniversary Commemoration ...

, RCAF

The Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF; french: Aviation royale canadienne, ARC) is the air and space force of Canada. Its role is to "provide the Canadian Forces with relevant, responsive and effective airpower". The RCAF is one of three environme ...

and RNZAF

The Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF) ( mi, Te Tauaarangi o Aotearoa, "The Warriors of the Sky of New Zealand"; previously ', "War Party of the Blue") is the aerial service branch of the New Zealand Defence Force. It was formed from New Zeal ...

units and personnel serving with RAF Bomber Command

RAF Bomber Command controlled the Royal Air Force's bomber forces from 1936 to 1968. Along with the United States Army Air Forces, it played the central role in the strategic bombing of Germany in World War II. From 1942 onward, the British bo ...

in Europe. In 1944, early planning proposed a force of 500–1,000 aircraft, including units dedicated to aerial refueling. Planning was later scaled back to 22 squadrons and, by the time the war ended, to 10 squadrons: between 120 and 150 Avro Lancaster

The Avro Lancaster is a British Second World War heavy bomber. It was designed and manufactured by Avro as a contemporary of the Handley Page Halifax, both bombers having been developed to the same specification, as well as the Short Stirlin ...

s/ Lincolns, operating out of airbases on Okinawa. Tiger Force was to have included the elite 617 Squadron

Number 617 Squadron is a Royal Air Force aircraft squadron, originally based at RAF Scampton in Lincolnshire and currently based at RAF Marham in Norfolk. It is commonly known as "''The Dambusters''", for its actions during Operation Chastis ...

, also known as "The Dambusters", which carried out specialist bombing operations.

Initially, US planners also did not plan to use any non-US Allied ground forces in Operation Downfall. Had reinforcements been needed at an early stage of Olympic, they would have been diverted from US forces being assembled for Coronet—for which there was to be a massive redeployment of units from the US Army's Southwest Pacific

The points of the compass are a set of horizontal, radially arrayed compass directions (or azimuths) used in navigation and cartography. A compass rose is primarily composed of four cardinal directions—north, east, south, and west—each sepa ...

, China-Burma-India and European

European, or Europeans, or Europeneans, may refer to:

In general

* ''European'', an adjective referring to something of, from, or related to Europe

** Ethnic groups in Europe

** Demographics of Europe

** European cuisine, the cuisines of Europe ...

commands, among others. These would have included spearheads of the war in Europe such as the US First Army (15 divisions) and the Eighth Air Force

The Eighth Air Force (Air Forces Strategic) is a numbered air force (NAF) of the United States Air Force's Air Force Global Strike Command (AFGSC). It is headquartered at Barksdale Air Force Base, Louisiana. The command serves as Air Force ...

. These redeployments would have been complicated by the simultaneous demobilization and replacement of highly experienced, time-served personnel, which would have drastically reduced the combat effectiveness of many units. The Australian government had asked at an early stage for the inclusion of an Australian Army

The Australian Army is the principal Army, land warfare force of Australia, a part of the Australian Defence Force (ADF) along with the Royal Australian Navy and the Royal Australian Air Force. The Army is commanded by the Chief of Army (Austral ...

infantry division in the first wave (Olympic). This was rejected by U.S. commanders and even the initial plans for Coronet, according to U.S. historian John Ray Skates, did not envisage that units from Commonwealth or other Allied armies would be landed on the Kantō Plain in 1946. The first official "plans indicated that assault, followup, and reserve units would all come from US forces".

By mid-1945—when plans for Coronet were being reworked—many other Allied countries had, according to Skates, "offered ground forces, and a debate developed" amongst Western Allied political and military leaders, "over the size, mission, equipment, and support of these contingents". Following negotiations, it was decided that Coronet would include a joint Commonwealth Corps

The Commonwealth Corps was the name given to a proposed British Commonwealth army formation, which was scheduled to take part in the planned Allied invasion of Japan during 1945 and 1946. The corps was never formed, however, as the Japanese surr ...

, made up of infantry divisions from the Australian

Australian(s) may refer to:

Australia

* Australia, a country

* Australians, citizens of the Commonwealth of Australia

** European Australians

** Anglo-Celtic Australians, Australians descended principally from British colonists

** Aboriginal A ...

, British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

and Canadian

Canadians (french: Canadiens) are people identified with the country of Canada. This connection may be residential, legal, historical or cultural. For most Canadians, many (or all) of these connections exist and are collectively the source of ...

armies. Reinforcements would have been available from those countries, as well as other parts of the Commonwealth. However, MacArthur blocked proposals to include an Indian Army

The Indian Army is the land-based branch and the largest component of the Indian Armed Forces. The President of India is the Supreme Commander of the Indian Army, and its professional head is the Chief of Army Staff (COAS), who is a four- ...

division because of differences in language, organization, composition, equipment, training and doctrine. He also recommended that the corps be organized along the lines of a U.S. corps, should use only U.S. equipment and logistics, and should train in the U.S. for six months before deployment; these suggestions were accepted. The British Government suggested that: Lieutenant-General Sir Charles Keightley

General Sir Charles Frederic Keightley, (24 June 1901 – 17 June 1974) was a senior British Army officer who served during and following the Second World War. After serving with distinction during the Second World War – becoming, in 1944, th ...

should command the Commonwealth Corps, a combined Commonwealth fleet should be led by Vice-Admiral Sir William Tennant, and that—as Commonwealth air units would be dominated by the RAAF – the Air Officer Commanding should be Australian. However, the Australian government questioned the appointment of an officer with no experience in fighting the Japanese, such as Keightley and suggested that Lieutenant General Leslie Morshead

Lieutenant General Sir Leslie James Morshead, (18 September 1889 – 26 September 1959) was an Australian soldier, teacher, businessman, and farmer, whose military career spanned both world wars. During the Second World War, he led the Austra ...

, an Australian who had been carrying out the New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu

Hiri Motu, also known as Police Motu, Pidgin Motu, or just Hiri, is a language of Papua New Guinea, which is spoken in surrounding areas of Port Moresby (Capital of Papua New Guinea).

It is a simplified version of ...

and Borneo campaigns, should be appointed. The war ended before the details of the corps were finalized.

Projected initial commitment

Figures for Coronet exclude values for both the immediate strategic reserve of 3 divisions as well as the 17 division strategic reserve in the U.S. and any British/Commonwealth forces.Operation Ketsugō

Meanwhile, the Japanese had their own plans. Initially, they were concerned about an invasion during the summer of 1945. However, the

Meanwhile, the Japanese had their own plans. Initially, they were concerned about an invasion during the summer of 1945. However, the Battle of Okinawa

The , codenamed Operation Iceberg, was a major battle of the Pacific War fought on the island of Okinawa by United States Army (USA) and United States Marine Corps (USMC) forces against the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA). The initial invasion of ...

went on for so long that they concluded the Allies would not be able to launch another operation before the typhoon season, during which the weather would be too risky for amphibious operations. Japanese intelligence predicted fairly closely where the invasion would take place: southern Kyūshū at Miyazaki, Ariake Bay and/or the Satsuma Peninsula.

While Japan no longer had a realistic prospect of winning the war, Japan's leaders believed they could make the cost of invading and occupying the Home Islands too high for the Allies to accept, which would lead to some sort of armistice

An armistice is a formal agreement of warring parties to stop fighting. It is not necessarily the end of a war, as it may constitute only a cessation of hostilities while an attempt is made to negotiate a lasting peace. It is derived from the La ...

rather than total defeat. The Japanese plan for defeating the invasion was called ("Operation Codename Decisive"). The Japanese planned to commit the entire population of Japan to resisting the invasion, and from June 1945 onward, a propaganda campaign calling for "The Glorious Death of One Hundred Million" commenced. The main message of "The Glorious Death of One Hundred Million" campaign was that it was "glorious to die for the holy emperor of Japan, and every Japanese man, woman, and child should die for the Emperor when the Allies arrived". While this was not realistic, both American and Japanese officers at the time predicted a Japanese death toll in the millions. From the Battle of Saipan onward, Japanese propaganda intensified the glory of patriotic death and depicted the Americans as merciless "white devils". During the Battle of Okinawa, Japanese officers had ordered civilians unable to fight to commit suicide rather than fall into American hands, and all available evidence suggests the same orders would have been given in the home islands. The Japanese were secretly constructing an underground headquarters in Matsushiro, Nagano Prefecture, to shelter the Emperor and the Imperial General Staff during an invasion. In planning for Operation Ketsugo, IGHQ overestimated the strength of the invading forces: while the Allied invasion plan called for fewer than 70 divisions, the Japanese expected up to 90.

''Kamikaze''

AdmiralMatome Ugaki

was an admiral in the Imperial Japanese Navy during World War II, remembered for his extensive and revealing war diary, role at the Battle of Leyte Gulf, and kamikaze suicide hours after the announced surrender of Japan at the end of the war. ...

was recalled to Japan in February 1945 and given command of the Fifth Air Fleet on Kyūshū. The Fifth Air Fleet was assigned the task of ''kamikaze

, officially , were a part of the Japanese Special Attack Units of military aviators who flew suicide attacks for the Empire of Japan against Allied naval vessels in the closing stages of the Pacific campaign of World War II, intending to d ...

'' attacks against ships involved in the invasion of Okinawa, Operation Ten-Go

, also known as Operation Heaven One (or Ten-ichi-gō 天一号), was the last major Japanese naval operation in the Pacific Theater of World War II. The resulting engagement is also known as the Battle of the East China Sea.

In April 1945, t ...

, and began training pilots and assembling aircraft for the defense of Kyūshū, the first invasion target.

The Japanese defense relied heavily on ''kamikaze'' planes. In addition to fighters and bombers, they reassigned almost all of their trainers for the mission. More than 10,000 aircraft were ready for use in July (with more by October), as well as hundreds of newly built small suicide boats to attack Allied ships offshore.

Up to 2,000 ''kamikaze'' planes launched attacks during the Battle of Okinawa, achieving approximately one hit per nine attacks. At Kyūshū, because of the more favorable circumstances (such as terrain that would reduce the Allies' radar advantage), they hoped to raise that to one for six by overwhelming the US defenses with large numbers of ''kamikaze'' attacks within a period of hours. The Japanese estimated that the planes would sink more than 400 ships; since they were training the pilots to target transports rather than carriers and destroyers, the casualties would be disproportionately greater than at Okinawa. One staff study estimated that the ''kamikazes'' could destroy a third to half of the invasion force before landing.

Admiral Ernest King

Ernest Joseph King (23 November 1878 – 25 June 1956) was an American naval officer who served as Commander in Chief, United States Fleet (COMINCH) and Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) during World War II. As COMINCH-CNO, he directed the U ...

, Commander-in-Chief of the U.S Navy, was so concerned about losses from ''kamikaze'' attacks that he and other senior naval officers argued for canceling Operation Downfall, and instead continuing the fire-bombing campaign against Japanese cities and the blockade of food and supplies until the Japanese surrendered. However, General George Marshall

George Catlett Marshall Jr. (December 31, 1880 – October 16, 1959) was an American army officer and statesman. He rose through the United States Army to become Chief of Staff of the US Army under Presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt and Harry ...

argued that forcing surrender this way might take several years, if ever. Accordingly, Marshall and United States Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox

William Franklin Knox (January 1, 1874 – April 28, 1944) was an American politician, newspaper editor and publisher. He was also the Republican vice presidential candidate in 1936, and Secretary of the Navy under Franklin D. Roosevelt durin ...

concluded the Americans would have to invade Japan to end the war, regardless of casualties.

Naval forces

Despite the shattering damage it had absorbed by this stage of the war, theImperial Japanese Navy

The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN; Kyūjitai: Shinjitai: ' 'Navy of the Greater Japanese Empire', or ''Nippon Kaigun'', 'Japanese Navy') was the navy of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945, when it was dissolved following Japan's surrender ...

, by then organized under the Navy General Command, was determined to inflict as much damage on the Allies as possible. Remaining major warships numbered four battleships (all damaged), five damaged aircraft carriers, two cruisers, 23 destroyers, and 46 submarines.Japanese Monograph No. 85 p. 16Retrieved 23 August 2015. However, the IJN lacked enough fuel for further sorties by its capital ships, planning instead to use their anti-aircraft firepower to defend naval installations while docked in port. Despite its inability to conduct large-scale fleet operations, the IJN still maintained a fleet of thousands of warplanes and possessed nearly 2 million personnel in the Home Islands, ensuring it a large role in the coming defensive operation. In addition, Japan had about 100 ''Kōryū''-class

midget submarine

A midget submarine (also called a mini submarine) is any submarine under 150 tons, typically operated by a crew of one or two but sometimes up to six or nine, with little or no on-board living accommodation. They normally work with mother ships, ...

s, 300 smaller ''Kairyū''-class midget submarines, 120 ''Kaiten

were crewed torpedoes and suicide craft, used by the Imperial Japanese Navy in the final stages of World War II.

History

In recognition of the unfavorable progress of the war, towards the end of 1943 the Japanese high command considered s ...

'' manned torpedo

Human torpedoes or manned torpedoes are a type of diver propulsion vehicle on which the diver rides, generally in a seated position behind a fairing. They were used as secret naval weapons in World War II. The basic concept is still in use.

...

es, and 2,412 '' Shin'yō'' suicide motorboats. Unlike the larger ships, these, together with the destroyers and fleet submarines, were expected to see extensive action defending the shores, with a view to destroying about 60 Allied transports.

The Navy trained a unit of frogmen

A frogman is someone who is trained in scuba diving or swimming underwater in a tactical capacity that includes military, and in some European countries, police work. Such personnel are also known by the more formal names of combat diver, comb ...

to serve as suicide bombers, the Fukuryu

were a part of the Japanese Special Attack Units prepared to resist the invasion of the Home islands by Allied forces. The name literally means "crouching dragon," and has also been called " suicide divers" or "kamikaze frogmen" in English te ...

. They were to be armed with contact-fuzed mines, and to dive under landing craft and blow them up. An inventory of mines was anchored to the sea bottom off each potential invasion beach for their use by the suicide divers, with up to 10,000 mines planned. Some 1,200 suicide divers had been trained before the Japanese surrender.

Ground forces

The two defensive options against amphibious invasion are strong defense of the beaches anddefense in depth

Defence in depth (also known as deep defence or elastic defence) is a military strategy that seeks to delay rather than prevent the advance of an attacker, buying time and causing additional casualties by yielding space. Rather than defeating ...

. Early in the war (such as at Tarawa

Tarawa is an atoll and the capital of the Republic of Kiribati,Kiribati

''

''

Unknown to the Americans, the Soviet Union also considered invading a major Japanese island, Hokkaido, by the end of August 1945,

Unknown to the Americans, the Soviet Union also considered invading a major Japanese island, Hokkaido, by the end of August 1945,