Operation Infinite Reach on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Operation Infinite Reach was the codename for American

p. 297.

Al-Qaeda had begun reconnoitering Nairobi for potential targets in December 1993, using a team led by Ali Mohamed. In January 1994, bin Laden was personally presented with the team's surveillance reports, and he and his senior advisers began to develop a plan to attack the American embassy there. From February to June 1998, al-Qaeda prepared to launch their attacks, renting residences, building their bombs, and acquiring trucks; meanwhile, bin Laden continued his public-relations efforts, giving interviews with

Al-Qaeda had begun reconnoitering Nairobi for potential targets in December 1993, using a team led by Ali Mohamed. In January 1994, bin Laden was personally presented with the team's surveillance reports, and he and his senior advisers began to develop a plan to attack the American embassy there. From February to June 1998, al-Qaeda prepared to launch their attacks, renting residences, building their bombs, and acquiring trucks; meanwhile, bin Laden continued his public-relations efforts, giving interviews with

p. 116. where CIA intelligence indicated bin Laden and other militants would be meeting on August 20, purportedly to plan further attacks against the U.S. Clinton was informed of the plan on August 12 and 14. Participants in the meeting later disagreed whether or not the intelligence indicated bin Laden would attend the meeting; however, an objective of the attack remained to kill the al-Qaeda leader, and the NSC encouraged the strike regardless of whether bin Laden and his companions were known to be present at Khost. The administration aimed to prevent future al-Qaeda attacks discussed in intercepted communications. As Berger later testified, the operation also sought to damage bin Laden's infrastructure and show the administration's commitment to combating bin Laden. The Khost complex, which was southeast of Kabul, also had ideological significance: Bin Laden had fought nearby during the

p. 117. Clarke was concerned the Pakistanis would shoot down the cruise missiles or airplanes if they were not notified, but also feared the

Four U.S. Navy ships and the submarine USS ''Columbia'', stationed in the

Four U.S. Navy ships and the submarine USS ''Columbia'', stationed in the

Two days after Operation Infinite Reach, Omar reportedly called the State Department, saying that the strikes would only lead to more anti-Americanism and terrorism, and that Clinton should resign. The embassy bombings and the declaration of war against the U.S. had divided the Taliban and angered Omar. However, bin Laden swore an oath of fealty to the Taliban leader, and the two became friends. According to Wright, Omar also believed that turning over bin Laden would weaken his position. In an October cable, the State Department also wrote that the missile strikes worsened Afghan-U.S. relations while bringing the Taliban and al-Qaeda closer together. A Taliban spokesman even told State Department officials in November that "If he Talibancould have retaliated with similar strikes against Washington, it would have." The Taliban also denied American charges that bin Laden was responsible for the embassy bombings. When Turki visited Omar to retrieve bin Laden, Omar told the prince that they had miscommunicated and he had never agreed to give the Saudis bin Laden. In Turki's account, Omar lambasted him when he protested, insulting the Saudi royal family and praising the Al-Qaeda leader; Turki left without bin Laden. The Saudis broke off relations with the Taliban and allegedly hired a young Uzbek named Siddiq Ahmed in a failed bid to assassinate bin Laden. American diplomatic engagement with the Taliban continued, and the State Department insisted to them that the U.S. was only opposed to bin Laden and al-Qaeda, at whom the missile strikes were aimed, not Afghanistan and its leadership.

Following the strikes, Osama bin Laden's spokesman announced that "The battle has not started yet. Our answer will be deeds, not words." Zawahiri made a phone call to reporter Rahimullah Yusufzai, stating that "We survived the attack ... we aren't afraid of bombardment, threats, and acts of aggression ... we are ready for more sacrifices. The war has only just begun; the Americans should now await the answer." Al-Qaeda attempted to recruit chemists to develop a more addictive type of

Two days after Operation Infinite Reach, Omar reportedly called the State Department, saying that the strikes would only lead to more anti-Americanism and terrorism, and that Clinton should resign. The embassy bombings and the declaration of war against the U.S. had divided the Taliban and angered Omar. However, bin Laden swore an oath of fealty to the Taliban leader, and the two became friends. According to Wright, Omar also believed that turning over bin Laden would weaken his position. In an October cable, the State Department also wrote that the missile strikes worsened Afghan-U.S. relations while bringing the Taliban and al-Qaeda closer together. A Taliban spokesman even told State Department officials in November that "If he Talibancould have retaliated with similar strikes against Washington, it would have." The Taliban also denied American charges that bin Laden was responsible for the embassy bombings. When Turki visited Omar to retrieve bin Laden, Omar told the prince that they had miscommunicated and he had never agreed to give the Saudis bin Laden. In Turki's account, Omar lambasted him when he protested, insulting the Saudi royal family and praising the Al-Qaeda leader; Turki left without bin Laden. The Saudis broke off relations with the Taliban and allegedly hired a young Uzbek named Siddiq Ahmed in a failed bid to assassinate bin Laden. American diplomatic engagement with the Taliban continued, and the State Department insisted to them that the U.S. was only opposed to bin Laden and al-Qaeda, at whom the missile strikes were aimed, not Afghanistan and its leadership.

Following the strikes, Osama bin Laden's spokesman announced that "The battle has not started yet. Our answer will be deeds, not words." Zawahiri made a phone call to reporter Rahimullah Yusufzai, stating that "We survived the attack ... we aren't afraid of bombardment, threats, and acts of aggression ... we are ready for more sacrifices. The war has only just begun; the Americans should now await the answer." Al-Qaeda attempted to recruit chemists to develop a more addictive type of 9/11 Commission Staff Statement No. 7

p. 4. Thus, Operation Infinite Reach was the only U.S. operation directed against bin Laden before the September 11 attacks. The operation's failure later dissuaded President

President Clinton's speech on the attacks

August 20, 1998

U.S. missiles pound targets in Afghanistan, Sudan; Clinton: 'Our target was terror'

1998 Missile Strikes on Bin Laden May Have Backfired

cruise missile

A cruise missile is a guided missile used against terrestrial or naval targets that remains in the atmosphere and flies the major portion of its flight path at approximately constant speed. Cruise missiles are designed to deliver a large warhea ...

strikes on Al-Qaeda

Al-Qaeda (; , ) is an Islamic extremist organization composed of Salafist jihadists. Its members are mostly composed of Arabs, but also include other peoples. Al-Qaeda has mounted attacks on civilian and military targets in various countr ...

bases in Khost Province

Khost (Pashto/Dari: ) is one of the 34 provinces of Afghanistan, located in the southeastern part of the country. Khost consists of thirteen districts and the city of Khost serves as the capital of the province. To the east, Khost Province is bord ...

, Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is border ...

, and the Al-Shifa pharmaceutical factory in Khartoum

Khartoum or Khartum ( ; ar, الخرطوم, Al-Khurṭūm, din, Kaartuɔ̈m) is the capital of Sudan. With a population of 5,274,321, its metropolitan area is the largest in Sudan. It is located at the confluence of the White Nile, flowing no ...

, Sudan

Sudan ( or ; ar, السودان, as-Sūdān, officially the Republic of the Sudan ( ar, جمهورية السودان, link=no, Jumhūriyyat as-Sūdān), is a country in Northeast Africa. It shares borders with the Central African Republic ...

, on August 20, 1998. The attacks, launched by the U.S. Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage o ...

, were ordered by President Bill Clinton

William Jefferson Clinton ( né Blythe III; born August 19, 1946) is an American politician who served as the 42nd president of the United States from 1993 to 2001. He previously served as governor of Arkansas from 1979 to 1981 and again ...

in retaliation for al-Qaeda's August 7 bombings of American embassies in Kenya

)

, national_anthem = " Ee Mungu Nguvu Yetu"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Nairobi

, coordinates =

, largest_city = Nairobi

...

and Tanzania

Tanzania (; ), officially the United Republic of Tanzania ( sw, Jamhuri ya Muungano wa Tanzania), is a country in East Africa within the African Great Lakes region. It borders Uganda to the north; Kenya to the northeast; Comoro Islands an ...

, which killed 224 people (including 12 Americans) and injured over 4,000 others. Operation Infinite Reach was the first time the United States acknowledged a preemptive strike

A preemptive war is a war that is commenced in an attempt to repel or defeat a perceived imminent offensive or invasion, or to gain a strategic advantage in an impending (allegedly unavoidable) war ''shortly before'' that attack materializes. It ...

against a violent non-state actor

In international relations, violent non-state actors (VNSAs), also known as non-state armed actors or non-state armed groups (NSAGs), are individuals or groups that are wholly or partly independent of governments and which threaten or use viole ...

.

U.S. intelligence wrongly suggested financial ties between the Al-Shifa plant, which produced over half of Sudan's pharmaceuticals, and Osama bin Laden

Osama bin Mohammed bin Awad bin Laden (10 March 1957 – 2 May 2011) was a Saudi-born extremist militant who founded al-Qaeda and served as its leader from 1988 until his death in 2011. Ideologically a pan-Islamist, his group is designated ...

, and a soil sample collected from Al-Shifa allegedly contained a chemical used in VX nerve gas manufacturing. Suspecting that Al-Shifa was linked to, and producing chemical weapon

A chemical weapon (CW) is a specialized munition that uses chemicals formulated to inflict death or harm on humans. According to the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), this can be any chemical compound intended as ...

s for, bin Laden and his al-Qaeda network, the U.S. destroyed the facility with cruise missiles, killing or wounding 11 Sudanese. The strike on Al-Shifa proved controversial; after the attacks, the U.S. evidence and rationale were criticized as faulty, and academics Max Taylor and Mohamed Elbushra cite "a broad acceptance that this plant was not involved in the production of any chemical weapons."

The missile strikes on al-Qaeda's Afghan training camps, aimed at preempting more attacks and killing bin Laden, damaged the installations and inflicted an uncertain number of casualties; however, bin Laden was not present at the time. Following the attacks, the ruling Taliban

The Taliban (; ps, طالبان, ṭālibān, lit=students or 'seekers'), which also refers to itself by its state name, the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, is a Deobandi Islamic fundamentalist, militant Islamist, jihadist, and Pasht ...

allegedly reneged on a promise to Saudi intelligence chief Turki al-Faisal to hand over bin Laden, and the regime instead strengthened its ties with the al-Qaeda chief.

Operation Infinite Reach, the largest U.S. action in response to a terrorist attack since the 1986 bombing of Libya, was met with a mixed international response: U.S. allies and most of the American public supported the strikes, but the targeted countries and other nations in the Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Province), East Thrace (Europ ...

strongly opposed them. The failure of the attacks to kill bin Laden also enhanced his public image in the Muslim world

The terms Muslim world and Islamic world commonly refer to the Islamic community, which is also known as the Ummah. This consists of all those who adhere to the religious beliefs and laws of Islam or to societies in which Islam is practiced. I ...

. Further strikes were planned but not executed; as a 2002 congressional inquiry noted, Operation Infinite Reach was "the only instance ... in which the CIA or U.S. military carried out an operation directly against Bin Laden before September 11

Events Pre-1600

* 9 – The Battle of the Teutoburg Forest ends: The Roman Empire suffers the greatest defeat of its history and the Rhine is established as the border between the Empire and the so-called barbarians for the next four h ...

."Report of the Joint Inquiry into Intelligence Community Activities before and after the Terrorist Attacks of September 11, 2001p. 297.

Background

On February 23, 1998,Osama bin Laden

Osama bin Mohammed bin Awad bin Laden (10 March 1957 – 2 May 2011) was a Saudi-born extremist militant who founded al-Qaeda and served as its leader from 1988 until his death in 2011. Ideologically a pan-Islamist, his group is designated ...

, Ayman al-Zawahiri

Ayman Mohammed Rabie al-Zawahiri (June 19, 1951 – July 31, 2022) was an Egyptian-born terrorist and physician who served as the second emir of al-Qaeda from June 16, 2011, until his death.

Al-Zawahiri graduated from Cairo University with ...

, and three other leaders of Islamic militant organizations issued a fatwa

A fatwā ( ; ar, فتوى; plural ''fatāwā'' ) is a legal ruling on a point of Islamic law (''sharia'') given by a qualified '' Faqih'' (Islamic jurist) in response to a question posed by a private individual, judge or government. A jurist i ...

in the name of the World Islamic Front for Jihad Against Jews and Crusaders, publishing it in '' Al-Quds Al-Arabi''. Deploring the stationing of U.S. troops in Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia, officially the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), is a country in Western Asia. It covers the bulk of the Arabian Peninsula, and has a land area of about , making it the List of Asian countries by area, fifth-largest country in Asia ...

, the alleged U.S. aim to fragment Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to the north, Iran to the east, the Persian Gulf and ...

, and U.S. support for Israel, they declared that "The ruling to kill the Americans and their allies—civilian and military—is an individual duty for every Muslim who can do it in any country in which it is possible to do it." In spring 1998, Saudi elites became concerned about the threat posed by al-Qaeda and bin Laden; militants attempted to infiltrate surface-to-air missile

A surface-to-air missile (SAM), also known as a ground-to-air missile (GTAM) or surface-to-air guided weapon (SAGW), is a missile designed to be launched from the ground to destroy aircraft or other missiles. It is one type of anti-aircraft syst ...

s inside the kingdom, an al-Qaeda defector alleged that Saudis were bankrolling bin Laden, and bin Laden himself lambasted the Saudi royal family. In June 1998, Al Mukhabarat Al A'amah

The General Intelligence Presidency (GIP); ( ar, (ر.ا.ع) رئاسة الاستخبارات العامة ), also known as the General Intelligence Directorate (GID), is the primary intelligence agency of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

History

Th ...

(Saudi intelligence) director Prince Turki bin Faisal Al Saud

Turki bin Faisal Al Saud ( ar, تركي بن فيصل آل سعود, Turkī ibn Fayṣal Āl Su‘ūd; tr, Türki bin Faysal Al Suud) (born 15 February 1945), known also as Turki Al Faisal, is a Saudi prince and former government official who s ...

traveled to Tarnak Farms to meet with Taliban

The Taliban (; ps, طالبان, ṭālibān, lit=students or 'seekers'), which also refers to itself by its state name, the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, is a Deobandi Islamic fundamentalist, militant Islamist, jihadist, and Pasht ...

leader Mullah Omar

Mullah Muhammad Omar (; –April 2013) was an Afghan Islamic revolutionary who founded the Taliban and served as the supreme leader of Afghanistan from Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan (1996–2001), 1996 to 2001.

Born into a religious family of ...

to discuss the question of bin Laden. Turki demanded that the Taliban either expel bin Laden from Afghanistan or hand him over to the Saudis, insisting that removing bin Laden was the price of cordial relations with the Kingdom. American analysts believed Turki offered a large amount of financial aid to resolve the dispute over bin Laden. Omar agreed to the deal, and the Saudis sent the Taliban 400 pickup trucks and funding, enabling the Taliban to retake Mazar-i-Sharif

, official_name =

, settlement_type = City

, image_skyline =

, pushpin_map = Afghanistan#Bactria#West Asia

, pushpin_label = Mazar-i-Sharif

, pushpin ...

. While the Taliban sent a delegation to Saudi Arabia in July for further discussions, the negotiations stalled by August.

Around the same time, the U.S. was planning its own actions against bin Laden. Michael Scheuer, chief of the Central Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian intelligence agency, foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gat ...

's bin Laden unit (Alec Station), considered using local Afghans to kidnap bin Laden, then exfiltrate him from Afghanistan in a modified Lockheed C-130 Hercules

The Lockheed C-130 Hercules is an American four-engine turboprop military transport aircraft designed and built by Lockheed (now Lockheed Martin). Capable of using unprepared runways for takeoffs and landings, the C-130 was originally desig ...

. Documents recovered from Wadih el-Hage's Nairobi

Nairobi ( ) is the capital and largest city of Kenya. The name is derived from the Maasai phrase ''Enkare Nairobi'', which translates to "place of cool waters", a reference to the Nairobi River which flows through the city. The city proper ...

computer suggested a link between bin Laden and the deaths of U.S. troops in Somalia

Somalia, , Osmanya script: 𐒈𐒝𐒑𐒛𐒐𐒘𐒕𐒖; ar, الصومال, aṣ-Ṣūmāl officially the Federal Republic of SomaliaThe ''Federal Republic of Somalia'' is the country's name per Article 1 of thProvisional Constituti ...

. These were used as the foundation for the June 1998 New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* ...

indictment of bin Laden, although the charges were later dropped. The planned raid was cancelled in May after internecine disputes between officials at the FBI and the CIA; the hesitation of the National Security Council

A national security council (NSC) is usually an executive branch governmental body responsible for coordinating policy on national security issues and advising chief executives on matters related to national security. An NSC is often headed by a na ...

(NSC) to approve the plan; concerns over the raid's chance of success, and the potential for civilian casualties.

Al-Qaeda had begun reconnoitering Nairobi for potential targets in December 1993, using a team led by Ali Mohamed. In January 1994, bin Laden was personally presented with the team's surveillance reports, and he and his senior advisers began to develop a plan to attack the American embassy there. From February to June 1998, al-Qaeda prepared to launch their attacks, renting residences, building their bombs, and acquiring trucks; meanwhile, bin Laden continued his public-relations efforts, giving interviews with

Al-Qaeda had begun reconnoitering Nairobi for potential targets in December 1993, using a team led by Ali Mohamed. In January 1994, bin Laden was personally presented with the team's surveillance reports, and he and his senior advisers began to develop a plan to attack the American embassy there. From February to June 1998, al-Qaeda prepared to launch their attacks, renting residences, building their bombs, and acquiring trucks; meanwhile, bin Laden continued his public-relations efforts, giving interviews with ABC News

ABC News is the journalism, news division of the American broadcast network American Broadcasting Company, ABC. Its flagship program is the daily evening newscast ''ABC World News Tonight, ABC World News Tonight with David Muir''; other progra ...

and Pakistani journalists

A journalist is an individual that collects/gathers information in form of text, audio, or pictures, processes them into a news-worthy form, and disseminates it to the public. The act or process mainly done by the journalist is called journalis ...

. While U.S. authorities had investigated al-Qaeda activities in Nairobi, they had not detected any warnings of imminent attacks.

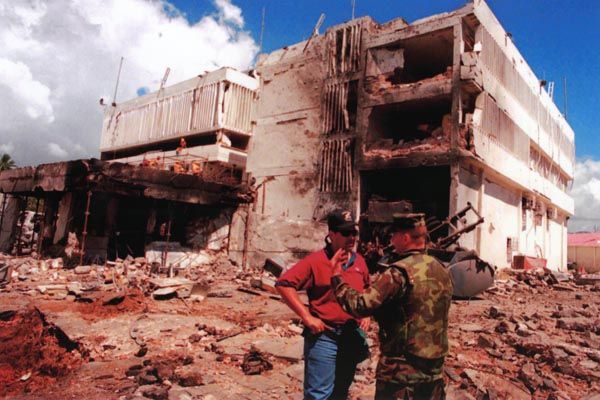

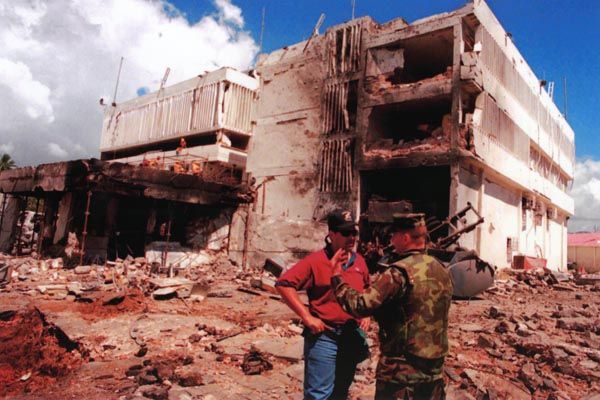

On August 7, 1998, al-Qaeda teams in Nairobi, Kenya, and Dar es Salaam

Dar es Salaam (; from ar, دَار السَّلَام, Dâr es-Selâm, lit=Abode of Peace) or commonly known as Dar, is the largest city and financial hub of Tanzania. It is also the capital of Dar es Salaam Region. With a population of over s ...

, Tanzania, attacked the cities' U.S. embassies simultaneously with truck bombs. In Nairobi, the explosion collapsed the nearby Ufundi Building and destroyed the embassy, killing 213 people, including 12 Americans; another 4,000 people were wounded. In Dar es Salaam, the bomber was unable to get close enough to the embassy to demolish it, but the blast killed 11 Africans and wounded 85. Bin Laden justified the high-casualty attacks, the largest against the U.S. since the 1983 Beirut barracks bombings

Early on a Sunday morning, October 23, 1983, two truck bombs struck buildings in Beirut, Lebanon, housing American and French service members of the Multinational Force in Lebanon (MNF), a military peacekeeping operation during the Lebanese ...

, by claiming they were in retaliation for the deployment of U.S. troops in Somalia; he also alleged that the embassies had devised the Rwandan genocide

The Rwandan genocide occurred between 7 April and 15 July 1994 during the Rwandan Civil War. During this period of around 100 days, members of the Tutsi minority ethnic group, as well as some moderate Hutu and Twa, were killed by armed Hu ...

as well as a supposed plan to partition Sudan.

Execution

Planning the strikes

National Security AdvisorSandy Berger

Samuel Richard "Sandy" Berger (October 28, 1945 – December 2, 2015) was an attorney who served as the 18th US National Security Advisor for US President Bill Clinton from 1997 to 2001 after he had served as the Deputy National Security Advis ...

called President Bill Clinton at 5:35 AM on August 7 to notify him of the bombings. That day, Clinton started meeting with his "Small Group" of national security advisers, which included Berger, CIA

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gathering, processing, ...

director George Tenet

George John Tenet (born January 5, 1953) is an American intelligence official and academic who served as the Director of Central Intelligence (DCI) for the United States Central Intelligence Agency, as well as a Distinguished Professor in the P ...

, Secretary of State Madeleine Albright

Madeleine Jana Korbel Albright (born Marie Jana Korbelová; May 15, 1937 – March 23, 2022) was an American diplomat and political scientist who served as the 64th United States secretary of state from 1997 to 2001. A member of the Democratic ...

, Attorney General Janet Reno

Janet Wood Reno (July 21, 1938 – November 7, 2016) was an American lawyer who served as the 78th United States attorney general. She held the position from 1993 to 2001, making her the second-longest serving attorney general, behind only W ...

, Defense Secretary William Cohen

William Sebastian Cohen (born August 28, 1940) is an American lawyer, author, and politician from the U.S. state of Maine. A Republican, Cohen served as both a member of the United States House of Representatives (1973–1979) and Senate (1 ...

, and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff

The chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (CJCS) is the presiding officer of the United States Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS). The chairman is the highest-ranking and most senior military officer in the United States Armed Forces Chairman: app ...

Hugh Shelton

Henry Hugh Shelton (born January 2, 1942) is a former United States Army officer who served as the 14th chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff from 1997 to 2001.

Early life, family and education

Shelton was born in Tarboro, North Carolina and ...

. The group's objective was to plan a military response to the East Africa embassy bombings. Initially the U.S. suspected either Hamas

Hamas (, ; , ; an acronym of , "Islamic Resistance Movement") is a Palestinian Sunni- Islamic fundamentalist, militant, and nationalist organization. It has a social service wing, Dawah, and a military wing, the Izz ad-Din al-Qassa ...

or Hezbollah

Hezbollah (; ar, حزب الله ', , also transliterated Hizbullah or Hizballah, among others) is a Lebanese Shia Islamist political party and militant group, led by its Secretary-General Hassan Nasrallah since 1992. Hezbollah's paramil ...

for the bombings, but FBI Agents John P. O'Neill

John Patrick O'Neill (February 6, 1952September 11, 2001) was an American counter-terrorism expert who worked as a special agent and eventually a Special Agent in Charge in the Federal Bureau of Investigation. In 1995, O'Neill began to intense ...

and Ali Soufan

Ali H. Soufan (born 1971) is a Lebanese-American former FBI agent who was involved in a number of high-profile anti-terrorism cases both in the United States and around the world. A 2006 '' New Yorker'' article described Soufan as coming close ...

demonstrated that al-Qaeda was responsible. Based on electronic and phone intercepts, physical evidence from Nairobi, and interrogations, officials soon demonstrated bin Laden as the perpetrator of the attacks. On August 8, the White House asked the CIA and the Joint Chiefs of Staff

The Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) is the body of the most senior uniformed leaders within the United States Department of Defense, that advises the president of the United States, the secretary of defense, the Homeland Security Council and ...

to prepare a targets list; the initial list included twenty targets in Sudan, Afghanistan, and an unknown third country, although it was narrowed down on August 12.

In an August 10 Small Group meeting, the principals agreed to use Tomahawk

A tomahawk is a type of single-handed axe used by the many Indigenous peoples and nations of North America. It traditionally resembles a hatchet with a straight shaft. In pre-colonial times the head was made of stone, bone, or antler, and Euro ...

cruise missiles, rather than troops or aircraft, in the retaliatory strikes. Cruise missiles had been previously used against Libya

Libya (; ar, ليبيا, Lībiyā), officially the State of Libya ( ar, دولة ليبيا, Dawlat Lībiyā), is a country in the Maghreb region in North Africa. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to the east, Suda ...

and Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to the north, Iran to the east, the Persian Gulf and ...

as reprisals for the 1986 Berlin discotheque bombing

On 5 April 1986, three people were killed and 229 injured when ''La Belle'' discothèque was bombed in the Friedenau district of West Berlin. The entertainment venue was commonly frequented by United States soldiers, and two of the dead and ...

and the 1993 attempted assassination of then-President George H. W. Bush

George Herbert Walker BushSince around 2000, he has been usually called George H. W. Bush, Bush Senior, Bush 41 or Bush the Elder to distinguish him from his eldest son, George W. Bush, who served as the 43rd president from 2001 to 2009; p ...

. Using cruise missiles also helped to preserve secrecy; airstrikes would have required more preparation that might have leaked to the media and alerted bin Laden. The option of using commandos was discarded, as it required too much time to prepare forces, logistics, and combat search and rescue

Combat search and rescue (CSAR) are search and rescue operations that are carried out during war that are within or near combat zones.

A CSAR mission may be carried out by a task force of helicopters, ground-attack aircraft, aerial refueling ...

. Using helicopters or bombers would have been difficult due to the lack of a suitable base or Pakistani permission to cross its airspace, and the administration also feared a recurrence of the disastrous 1980 Operation Eagle Claw

Operation Eagle Claw, known as Operation Tabas ( fa, عملیات طبس) in Iran, was a failed operation by the United States Armed Forces ordered by U.S. President Jimmy Carter to attempt the rescue of 52 embassy staff held captive at the ...

in Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Tu ...

. While military officials suggested bombing Kandahar

Kandahar (; Kandahār, , Qandahār) is a city in Afghanistan, located in the south of the country on the Arghandab River, at an elevation of . It is Afghanistan's second largest city after Kabul, with a population of about 614,118. It is the ...

, which bin Laden and his associates often visited, the administration was concerned about killing civilians and hurting the U.S.' image.

On August 11, General Anthony Zinni of Central Command was instructed to plan attacks on bin Laden's Khost

Khōst ( ps, خوست) is the capital of Khost Province in Afghanistan. It is the largest city in the southeastern part of the country, and also the largest in the region of Loya Paktia. To the south and east of Khost lie Waziristan and Kurram i ...

camps,9/11 Commission Reportp. 116. where CIA intelligence indicated bin Laden and other militants would be meeting on August 20, purportedly to plan further attacks against the U.S. Clinton was informed of the plan on August 12 and 14. Participants in the meeting later disagreed whether or not the intelligence indicated bin Laden would attend the meeting; however, an objective of the attack remained to kill the al-Qaeda leader, and the NSC encouraged the strike regardless of whether bin Laden and his companions were known to be present at Khost. The administration aimed to prevent future al-Qaeda attacks discussed in intercepted communications. As Berger later testified, the operation also sought to damage bin Laden's infrastructure and show the administration's commitment to combating bin Laden. The Khost complex, which was southeast of Kabul, also had ideological significance: Bin Laden had fought nearby during the

Soviet–Afghan War

The Soviet–Afghan War was a protracted armed conflict fought in the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan from 1979 to 1989. It saw extensive fighting between the Soviet Union and the Afghan mujahideen (alongside smaller groups of anti-Soviet ...

, and he had given interviews and even held a press conference at the site. Felix Sater, then a CIA source, provided additional intelligence on the camps' locations.

On August 14, Tenet told the Small Group that bin Laden and al-Qaeda were doubtless responsible for the attack; Tenet called the intelligence a "slam dunk", according to counterterrorism official Richard Clarke, and Clinton approved the attacks the same day. As the 9/11 Commission Report

''The 9/11 Commission Report'' (officially the ''Final Report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States)'' is the official report into the events leading up to the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks. It was prepa ...

relates, the group debated "whether to strike targets outside of Afghanistan". Tenet briefed the small group again on August 17 regarding possible targets in Afghanistan and Sudan; on August 19, the Al-Shifa pharmaceutical facility in Khartoum

Khartoum or Khartum ( ; ar, الخرطوم, Al-Khurṭūm, din, Kaartuɔ̈m) is the capital of Sudan. With a population of 5,274,321, its metropolitan area is the largest in Sudan. It is located at the confluence of the White Nile, flowing no ...

, Sudan, al-Qaeda's Afghan camps, and a Sudanese tannery were designated as targets. The aim of striking the tannery, which had allegedly been given to bin Laden by the Sudanese for his road-building work, was to disrupt bin Laden's finances, but it was removed as a target due to fears of inflicting civilian casualties without any loss for bin Laden. Clinton gave the final approval for the attacks at 3:00 AM on August 20; the same day, he also signed Executive Order 13099, authorizing sanctions on bin Laden and al-Qaeda. The Clinton administration justified Operation Infinite Reach under Article 51 of the UN Charter and Title 22, Section 2377 of the U.S. Code

In the law of the United States, the Code of Laws of the United States of America (variously abbreviated to Code of Laws of the United States, United States Code, U.S. Code, U.S.C., or USC) is the official compilation and codification of the ...

; the former guarantees a UN member state's right to self-defense

Self-defense (self-defence primarily in Commonwealth English) is a countermeasure that involves defending the health and well-being of oneself from harm. The use of the right of self-defense as a legal justification for the use of force i ...

, while the latter authorizes presidential action by "all necessary means" to target international terrorist infrastructure. Government lawyers asserted that since the missile strikes were an act of self-defense and not directed at an individual, they were not forbidden as an assassination. A review by administration lawyers concluded that the attack would be legal, since the president has the authority to attack the infrastructure of anti-American

Anti-Americanism (also called anti-American sentiment) is prejudice, fear, or hatred of the United States, its government, its foreign policy, or Americans in general.

Political scientist Brendon O'Connor at the United States Studies C ...

terrorist groups, and al-Qaeda's infrastructure was largely human. Officials also interpreted "infrastructure" to include al-Qaeda's leadership.

The missiles would pass into Pakistani airspace, overflying "a suspected Pakistani nuclear weapons site," according to Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff

The vice chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (VJCS) is, by U.S. law, the second highest-ranking military officer in the United States Armed Forces, - Vice Chairman ranking just below the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. The vice chairman ...

General Joseph Ralston; U.S. officials feared Pakistan would mistake them for an India

India, officially the Republic of India ( Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the ...

n nuclear attack

Nuclear warfare, also known as atomic warfare, is a theoretical military conflict or prepared political strategy that deploys nuclear weaponry. Nuclear weapons are weapons of mass destruction; in contrast to conventional warfare, nuclear ...

.9/11 Commission Reportp. 117. Clarke was concerned the Pakistanis would shoot down the cruise missiles or airplanes if they were not notified, but also feared the

ISI

ISI or Isi may refer to:

Organizations

* Intercollegiate Studies Institute, a classical conservative organization focusing on college students

* Ice Skating Institute, a trade association for ice rinks

* Indian Standards Institute, former name o ...

would warn the Taliban or al-Qaeda if they were alerted. In Islamabad

Islamabad (; ur, , ) is the capital city of Pakistan. It is the country's ninth-most populous city, with a population of over 1.2 million people, and is federally administered by the Pakistani government as part of the Islamabad Capital ...

on the evening of August 20, Ralston informed Pakistan Army

The Pakistan Army (, ) is the land service branch of the Pakistan Armed Forces. The roots of its modern existence trace back to the British Indian Army that ceased to exist following the Partition of British India, which occurred as a resul ...

Chief of Staff

The title chief of staff (or head of staff) identifies the leader of a complex organization such as the armed forces, institution, or body of persons and it also may identify a principal staff officer (PSO), who is the coordinator of the supporti ...

Jehangir Karamat of the incoming American strikes ten minutes before the missiles entered Pakistani airspace. Clarke also worried the Pakistanis would notice the U.S. Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage o ...

ships, but was told that submerged submarines would launch the missiles. However, the Pakistan Navy

ur, ہمارے لیے اللّٰہ کافی ہے اور وہ بہترین کارساز ہے۔ English: Allah is Sufficient for us - and what an excellent (reliable) Trustee (of affairs) is He!(''Qur'an, 3:173'')

, type ...

detected the destroyers and informed the government.

Al-Shifa plant attack

At about 7:30 PM Khartoum time (17:30GMT

Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) is the mean solar time at the Royal Observatory in Greenwich, London, counted from midnight. At different times in the past, it has been calculated in different ways, including being calculated from noon; as a c ...

), two American warships in the Red Sea

The Red Sea ( ar, البحر الأحمر - بحر القلزم, translit=Modern: al-Baḥr al-ʾAḥmar, Medieval: Baḥr al-Qulzum; or ; Coptic: ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϩⲁϩ ''Phiom Enhah'' or ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϣⲁⲣⲓ ''Phiom ǹšari''; ...

( USS ''Briscoe'' and USS ''Hayler'') fired thirteen Tomahawk missiles at Sudan's Al-Shifa pharmaceutical factory, which the U.S. wrongly claimed was helping bin Laden build chemical weapons. The entire factory was destroyed except for the administration, water-cooling, and plant laboratory sections, which were severely damaged. One night watchman was killed and ten other Sudanese were wounded by the strike. Worried about the possibility for hazardous chemical leakages, analysts ran computer simulations on wind patterns, climate, and chemical data, which indicated a low risk of collateral damage. Regardless, planners added more cruise missiles to the strike on Al-Shifa, aiming to completely destroy the plant and any dangerous substances.

Clarke stated that intelligence linked bin Laden to Al-Shifa's current and past operators, namely Iraqi nerve gas

Nerve agents, sometimes also called nerve gases, are a class of organic chemicals that disrupt the mechanisms by which nerves transfer messages to organs. The disruption is caused by the blocking of acetylcholinesterase (AChE), an enzyme that ...

experts such as Emad al-Ani and Sudan's ruling National Islamic Front. Since 1995, the CIA had received intelligence suggesting collaboration between Sudan and bin Laden to produce chemical weapons for attacking U.S. Armed Forces personnel based in Saudi Arabia. Since 1989, the Sudanese opposition and Uganda

}), is a landlocked country in East Africa. The country is bordered to the east by Kenya, to the north by South Sudan, to the west by the Democratic Republic of the Congo, to the south-west by Rwanda, and to the south by Tanzania. The sou ...

had alleged that the regime was manufacturing and using chemical weapon

A chemical weapon (CW) is a specialized munition that uses chemicals formulated to inflict death or harm on humans. According to the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), this can be any chemical compound intended as ...

s, although the U.S. did not accuse Sudan of chemical weapons proliferation. Al-Qaeda defector Jamal al-Fadl

Jamal Ahmed al-FadlJamal al-Fadl testimony, United States vs. Osama bin Laden et al., trial transcript, Day 2, Feb. 6, 2001. ( ar, جمال أحمد محمّد الفضل, ''Jamāl Aḥmad Muḥammad al-Faḍl'') (born 1963-) is a Sudanese militan ...

had also spoken of bin Laden's desire to obtain weapons of mass destruction

A weapon of mass destruction (WMD) is a chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear, or any other weapon that can kill and bring significant harm to numerous individuals or cause great damage to artificial structures (e.g., buildings), natu ...

, and an August 4 CIA intelligence report suggested bin Laden "had already acquired chemical weapons and might be ready to attack". Cohen later testified that physical evidence, technical and human intelligence, and the site's security and purported links to bin Laden backed the intelligence community's view that the Al-Shifa plant was producing chemical weapons and associated with terrorists.

With the help of an Egyptian agent, the CIA had obtained a sample of soil from the facility taken in December 1997 showing the presence of O-Ethyl methylphosphonothioic acid (EMPTA), a substance used in the production of VX nerve gas, at 2.5 times trace levels. (Reports are contradictory on whether the soil was obtained from within the compound itself, or outside.) The collected soil was split into three samples, which were then analyzed by a private laboratory. The agent's bona fides were later confirmed through polygraph

A polygraph, often incorrectly referred to as a lie detector test, is a device or procedure that measures and records several physiological indicators such as blood pressure, pulse, respiration, and skin conductivity while a person is asked an ...

testing; however, the CIA produced a report on Al-Shifa on July 24, 1998, questioning whether Al-Shifa produced chemical weapons or simply stored precursors, and the agency advised collecting more soil samples. Cohen and Tenet later briefed U.S. senators on intercepted telephone communications from the plant that reputedly bolstered the U.S. case against Al-Shifa. U.S. intelligence also purportedly researched the Al-Shifa factory online and searched commercial databases, but did not find any medicines for sale.

Al-Shifa controversy

U.S. officials later acknowledged that the evidence cited by the U.S. in its rationale for the Al-Shifa strike was weaker than initially believed: The facility had not been involved in chemical weapons production, and was not connected to bin Laden. The $30 million Al-Shifa factory, which had a $199,000 contract with the UN under theOil-for-Food Programme

The Oil-for-Food Programme (OIP), established by the United Nations in 1995 (under UN Security Council Resolution 986) was established to allow Iraq to sell oil on the world market in exchange for food, medicine, and other humanitarian needs fo ...

, employed 300 Sudanese and provided over half of the country's pharmaceuticals

A medication (also called medicament, medicine, pharmaceutical drug, medicinal drug or simply drug) is a drug used to diagnose, cure, treat, or prevent disease. Drug therapy (pharmacotherapy) is an important part of the medical field an ...

, including medicines for malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or deat ...

, diabetes

Diabetes, also known as diabetes mellitus, is a group of metabolic disorders characterized by a high blood sugar level (hyperglycemia) over a prolonged period of time. Symptoms often include frequent urination, increased thirst and increased ap ...

, gonorrhea

Gonorrhea, colloquially known as the clap, is a sexually transmitted infection (STI) caused by the bacterium ''Neisseria gonorrhoeae''. Infection may involve the genitals, mouth, or rectum. Infected men may experience pain or burning with ur ...

, and tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, in w ...

. A Sudanese named Salah Idris purchased the plant in March 1998; while the CIA later said it found financial ties between Idris and the bin Laden-linked terrorist group Egyptian Islamic Jihad

The Egyptian Islamic Jihad (EIJ, ar, الجهاد الإسلامي المصري), formerly called simply Islamic Jihad ( ar, الجهاد الإسلامي, links=no) and the Liberation Army for Holy Sites, originally referred to as al-Jihad, and ...

, the agency had been unaware at the time that Idris owned the Al-Shifa facility. Idris later denied any links to bin Laden and sued to recover $24 million in funds frozen by the U.S., as well as for the damage to his factory. Idris hired investigations firm Kroll Inc.

Kroll is an American corporate investigation and risk consulting firm established in 1972 and based in New York City. In 2018, Kroll was acquired by Duff & Phelps. In 2021, Duff & Phelps decided to rebrand itself as Kroll, a process it complet ...

, which reported in February 1999 that neither Idris nor Al-Shifa was connected to terrorism.

The chairman of Al-Shifa Pharmaceutical Industries insisted that his factory did not make nerve gas

Nerve agents, sometimes also called nerve gases, are a class of organic chemicals that disrupt the mechanisms by which nerves transfer messages to organs. The disruption is caused by the blocking of acetylcholinesterase (AChE), an enzyme that ...

, and Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir formed a commission to investigate the factory. Sudan invited the U.S. to conduct chemical tests at the site for evidence to support its claim that the plant might have been a chemical weapons factory; the U.S. refused the invitation to investigate and did not officially apologize for the attacks. Press coverage indicated that Al-Shifa was not a secure, restricted-access factory, as the U.S. alleged, and American officials later conceded that Al-Shifa manufactured pharmaceutical drugs. Sudan requested a UN investigation of the Al-Shifa plant to verify or disprove the allegations of weapons production; while the proposal was backed by several international organizations, it was opposed by the U.S.

The American Bureau of Intelligence and Research

The Bureau of Intelligence and Research (INR) is an intelligence agency in the United States Department of State. Its central mission is to provide all-source intelligence and analysis in support of U.S. diplomacy and foreign policy. INR is ...

(INR) criticized the CIA's intelligence on Al-Shifa and bin Laden in an August 6 memo; as James Risen reported, INR analysts concluded that "the evidence linking Al Shifa to bin Laden and chemical weapons was weak." According to Risen, some dissenting officials doubted the basis for the strike, but senior principals believed that "the risks of hitting the wrong target were far outweighed by the possibility that the plant was making chemical weapons for a terrorist eager to use them." Senior NSC intelligence official Mary McCarthy had stated that better intelligence was needed before planning a strike, while Reno, concerned about the lack of conclusive evidence, had pressed for delaying the strikes until the U.S. obtained better intelligence. According to CIA officer Paul R. Pillar, senior Agency officials met with Tenet before he briefed the White House on bin Laden and Al-Shifa, and the majority of them opposed attacking the plant. Barletta notes that "It is unclear precisely when U.S. officials decided to destroy the Shifa plant." ABC News reported that Al-Shifa was designated as a target just hours in advance; ''Newsweek

''Newsweek'' is an American weekly online news magazine co-owned 50 percent each by Dev Pragad, its president and CEO, and Johnathan Davis, who has no operational role at ''Newsweek''. Founded as a weekly print magazine in 1933, it was widely ...

'' stated that the plant was targeted on August 15–16; U.S. officials asserted that the plant was added as a target months in advance; and a '' U.S. News & World Report'' article contended that Al-Shifa had been considered as a target for years. Clinton ordered an investigation into the evidence used to justify the Al-Shifa strike, while as of July 1999, the House

A house is a single-unit residential building. It may range in complexity from a rudimentary hut to a complex structure of wood, masonry, concrete or other material, outfitted with plumbing, electrical, and heating, ventilation, and air condi ...

and Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the e ...

intelligence committees were also investigating the target-selection process, the evidence cited, and whether intelligence officials recommended attacking the plant.

It was later hypothesized that the EMPTA detected was the result of the breakdown of a pesticide or confused with , a structurally similar insecticide used in African agriculture. Eric Croddy contends that the sample did not contain Fonofos, arguing that Fonofos has a distinct ethyl group

In organic chemistry, an ethyl group (abbr. Et) is an alkyl substituent with the formula , derived from ethane (). ''Ethyl'' is used in the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry's nomenclature of organic chemistry for a satura ...

and a benzene

Benzene is an organic chemical compound with the molecular formula C6H6. The benzene molecule is composed of six carbon atoms joined in a planar ring with one hydrogen atom attached to each. Because it contains only carbon and hydrogen a ...

group, which distinguish it from EMPTA, and that the two chemicals could not be easily confused. Tests conducted in October 1999 by Idris' defense team found no trace of EMPTA. Although Tenet vouched for the Egyptian agent's truthfulness, Barletta questions the operative's bona fides, arguing that they may have misled U.S. intelligence; he also notes that the U.S. withdrew its intelligence staff from Sudan in 1996 and later retracted 100 intelligence reports from a fraudulent Sudanese source. Ultimately, Barletta concludes that "It remains possible that Al-Shifa Pharmaceutical Factory may have been involved in some way in producing or storing the chemical compound EMPTA ... On balance, the evidence available to date indicates that it is more probable that the Shifa plant had no role whatsoever in CW production."

Attack on Afghan camps

Four U.S. Navy ships and the submarine USS ''Columbia'', stationed in the

Four U.S. Navy ships and the submarine USS ''Columbia'', stationed in the Arabian Sea

The Arabian Sea ( ar, اَلْبَحرْ ٱلْعَرَبِيُّ, Al-Bahr al-ˁArabī) is a region of the northern Indian Ocean bounded on the north by Pakistan, Iran and the Gulf of Oman, on the west by the Gulf of Aden, Guardafui Channel ...

, fired between 60 and 75 Tomahawk cruise missiles into Afghanistan at the Zhawar Kili Al-Badr camp complex in the Khost region, which included a base camp, a support camp, and four training camps. Peter Bergen

Peter Bergen (born December 11, 1962) is an American journalist, author, and producer who serves as CNN's national security analyst and as New America's vice president. He produced the first television interview with Osama bin Laden in 1997, w ...

identifies the targeted camps, located in Afghanistan's "Pashtun

Pashtuns (, , ; ps, پښتانه, ), also known as Pakhtuns or Pathans, are an Iranian ethnic group who are native to the geographic region of Pashtunistan in the present-day countries of Afghanistan and Pakistan. They were historically ...

belt," as al-Badr 1 and 2, al-Farooq, Khalid bin Walid, Abu Jindal, and Salman Farsi; other sources identify the Muawia, Jihad Wahl, and Harkat-ul-Jihad al-Islami

Harkat-ul-Jihad-al-Islami ( ar, حركة الجهاد الإسلامي, ''Ḥarkat al-Jihād al-Islāmiyah'', meaning "Islamic Jihad Movement", HuJI) is a Pakistani Islamic fundamentalist Jihadist organisation affiliated with Al-Qaeda and Tali ...

camps as targets. According to Shelton, the base camp housed "storage, housing, training and administration facilities for the complex," while the support camp included weapons-storage facilities and managed the site's logistics. Egyptian Islamic Jihad and the Algeria

)

, image_map = Algeria (centered orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Algiers

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, relig ...

n Armed Islamic Group

The Armed Islamic Group (GIA, from french: Groupe Islamique Armé; ar, الجماعة الإسلامية المسلّحة, al-Jamāʿa l-ʾIslāmiyya l-Musallaḥa) was one of the two main Islamist insurgent groups that fought the Algerian gov ...

also used the Khost camps, as well as Pakistani militant groups fighting an insurgency in Kashmir, such as Harkat Ansar, Lashkar-e-Taiba, and Hizbul Mujahideen

Hizbul Mujahideen, also spelled Hizb-ul-Mujahideen ( ar, حزب المجاھدین, ), is an Islamist militant organization operating in the Kashmir region. Its goal is to separate Kashmir from India and merge it with Pakistan.

*

*

*

It i ...

. The rudimentary camps, reputedly run by Taliban official Jalaluddin Haqqani

Jalaluddin Haqqani ( ps, جلال الدين حقاني, Jalāl al-Dīn Ḥaqqānī) (1939 – 3 September 2018) was an Afghan insurgent commander who founded the Haqqani network, an insurgent group fighting in guerilla warfare against US-led ...

, were frequented by Arab, Chechen, and Central Asian militants, as well as the ISI. The missiles hit at roughly 10:00 PM Khost time (17:30 GMT); as in Sudan, the strikes were launched at night to avoid collateral damage. In contrast to the attack on Al-Shifa, the strike on the Afghan camps was uncontroversial.

The U.S. first fired unitary (C-model) Tomahawks at the Khost camps, aiming to attract militants into the open, then launched a barrage of D-model missiles equipped with submunitions

A cluster munition is a form of air-dropped or ground-launched explosive weapon that releases or ejects smaller submunitions. Commonly, this is a cluster bomb that ejects explosive bomblets that are designed to kill personnel and destroy vehicl ...

to maximize casualties. Sources differ on the precise number of casualties inflicted by the missile strikes. Bin Laden bodyguard Abu Jandal

Nasser al-Bahri (1972 – 26 December 2015), also known by his '' kunya'' or ''nom de guerre'' as Abu Jandal – "father of death" or "the killer", was a member of al-Qaeda in Afghanistan from 1996 to 2000. According to his memoir, he gave his B ...

and militant trainee Abdul Rahman Khadr later estimated that only six men had been killed in the strikes. The Taliban claimed 22 Afghans killed and over 50 seriously injured, while Berger put al-Qaeda casualties at between 20 and 30 men. Bin Laden jokingly told militants that only a few camels and chickens had died, although his spokesman cited losses of six Arabs killed and five wounded, seven Pakistanis killed and over 15 wounded, and 15 Afghans killed. A declassified September 9, 1998, State Department

The United States Department of State (DOS), or State Department, is an United States federal executive departments, executive department of the Federal government of the United States, U.S. federal government responsible for the country's fore ...

cable stated that around 20 Pakistanis and 15 Arabs died, out of a total of over 50 killed in the attack. Harkat-ul-Mujahideen

Harkat-ul-Mujahideen- al-Islami ( ur, ; HUM) is a Pakistan-based Islamic jihad group operating primarily in Kashmir.

's leader, Fazlur Rehman Khalil, initially claimed a death toll of over 50 militants, but later said that he had lost fewer than ten fighters.

Pakistani and hospital sources gave a death toll of eleven dead and fifty-three wounded. Pakistani journalist Ahmed Rashid

Ahmed Rashid (Urdu:; born 1948 in Pakistan) is a journalist and best-selling foreign policy author of several books about Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Central Asia.

Life and career

Ahmed Rashid was born in Rawalpindi, Pakistan. He attended ...

writes that 20 Afghans

Afghans ( ps, افغانان, translit=afghanan; Persian/ prs, افغان ها, translit=afghānhā; Persian: افغانستانی, romanized: ''Afghanistani'') or Afghan people are nationals or citizens of Afghanistan, or people with ancestry ...

, seven Pakistanis

Pakistanis ( ur, , translit=Pākistānī Qaum, ) are the citizens and nationals of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan. According to the 2017 Pakistani national census, the population of Pakistan stood at over 213 million people, making it the w ...

, three Yemen

Yemen (; ar, ٱلْيَمَن, al-Yaman), officially the Republic of Yemen,, ) is a country in Western Asia. It is situated on the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula, and borders Saudi Arabia to the north and Oman to the northeast and s ...

is, two Egyptians

Egyptians ( arz, المَصرِيُون, translit=al-Maṣriyyūn, ; arz, المَصرِيِين, translit=al-Maṣriyyīn, ; cop, ⲣⲉⲙⲛ̀ⲭⲏⲙⲓ, remenkhēmi) are an ethnic group native to the Nile, Nile Valley in Egypt. Egyptian ...

, one Saudi and one Turk were killed. Initial reports by Pakistani intelligence chief Chaudhry Manzoor and a Foreign Ministry In many countries, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs is the government department responsible for the state's diplomacy, bilateral, and multilateral relations affairs as well as for providing support for a country's citizens who are abroad. The entit ...

spokesman stated that a missile had landed in Pakistan and killed six Pakistanis; the government later retracted the statement and fired Manzoor for the incorrect report. However, the 9/11 Commission Report states that Clinton later called Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif

Mian Muhammad Nawaz Sharif (Urdu, Punjabi: ; born 25 December 1949) is a Pakistani businessman and politician who has served as the Prime Minister of Pakistan for three non-consecutive terms. He is the longest-serving prime minister of Paki ...

"to apologize for a wayward missile that had killed several people in a Pakistani village." One 1998 '' U.S. News & World Report'' article suggested that most of the strike's victims were Pakistani militants bound for the Kashmiri insurgency, rather than al-Qaeda members; the operation killed a number of ISI officers present in the camps. A 1999 press report stated that seven Harkat Ansar militants were killed and 24 were wounded, while eight Lashkar-e-Taiba and Hizbul Mujahideen members were killed. In a May 1999 meeting with American diplomats, Haqqani said his facilities had been destroyed and 25 of his men killed in the operation.

Following the attack, U.S. surveillance aircraft and reconnaissance satellites photographed the sites for damage assessment, although clouds obscured the area. According to ''The Washington Post

''The Washington Post'' (also known as the ''Post'' and, informally, ''WaPo'') is an American daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C. It is the most widely circulated newspaper within the Washington metropolitan area and has a large nati ...

'', the imagery indicated "considerable damage" to the camps, although "up to 20 percent of the missiles ... addisappointing results." Meanwhile, bin Laden made calls by satellite phone, attempting to ascertain the damage and casualties the camps had sustained. One anonymous official reported that some buildings were destroyed, while others suffered heavy or light damage or were unscathed. Abu Jandal stated that bathrooms, the kitchen, and the mosque were hit in the strike, but the camps were not completely destroyed. Berger claimed that the damage to the camps was "moderate to severe," while CIA agent Henry A. Crumpton later wrote that al-Qaeda "suffered a few casualties and some damaged infrastructure, but no more." Since the camps were relatively unsophisticated, they were quickly and easily rebuilt within two weeks.

ISI director Hamid Gul

Lieutenant General Hamid Gul ( ur, ; 20 November 1936 – 15 August 2015) was a three-star rank army general in the Pakistan Army and defence analyst. Gul was notable for serving as the Director-General of the Inter-Services Intellige ...

reportedly notified the Taliban of the missile strikes in advance; bin Laden, who survived the strikes, later claimed that he had been informed of them by Pakistanis. A bin Laden spokesman claimed that bin Laden and the Taliban had prepared for the strike after hearing of the evacuation of Americans from Pakistan. Other U.S. officials reject the tip-off theory, citing a lack of evidence and ISI casualties in the strike; Tenet later wrote in his memoirs

A memoir (; , ) is any nonfiction narrative writing based in the author's personal memories. The assertions made in the work are thus understood to be factual. While memoir has historically been defined as a subcategory of biography or autobi ...

that the CIA could not ascertain whether Bin Laden had been warned in advance. Steve Coll

Steve Coll (born October 8, 1958) is an American journalist, academic and executive.

He is currently the dean of the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism, where he is also the Henry R. Luce Professor of Journalism. A staff writer ...

reports that the CIA heard after the attack that bin Laden had been at Zhawar Kili Al-Badr but had left some hours before the missiles hit. Bill Gertz writes that the earlier arrest of Mohammed Odeh on August 7, while he was traveling to meet with bin Laden, alerted bin Laden, who canceled the meeting; this meant the camps targeted by the cruise missiles were mainly empty the day of the U.S. strike. Lawrence Wright says the CIA intercepted a phone call indicating that bin Laden would be in Khost, but the al-Qaeda chief instead decided to go to Kabul

Kabul (; ps, , ; , ) is the capital and largest city of Afghanistan. Located in the eastern half of the country, it is also a municipality, forming part of the Kabul Province; it is administratively divided into 22 municipal districts. Acc ...

. Other media reports indicate that the strike was delayed to maximize secrecy, thus missing bin Laden. Scheuer charges that while the U.S. had planned to target the complex's mosque during evening prayers to kill bin Laden and his associates, the White House allegedly delayed the strikes "to avoid offending the Muslim world". Simon Reeve states that Pakistani intelligence had informed bin Laden that the U.S. was using his phone to track him, so he turned it off and cancelled the meeting at Khost.

Aftermath

Reactions in the U.S.

Clinton flew back toWashington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

from his vacation at Martha's Vineyard

Martha's Vineyard, often simply called the Vineyard, is an island in the Northeastern United States, located south of Cape Cod in Dukes County, Massachusetts, known for being a popular, affluent summer colony. Martha's Vineyard includes th ...

, speaking with legislators from Air Force One

Air Force One is the official air traffic control designated call sign for a United States Air Force aircraft carrying the president of the United States. In common parlance, the term is used to denote U.S. Air Force aircraft modified and us ...

and British Prime Minister Tony Blair

Sir Anthony Charles Lynton Blair (born 6 May 1953) is a British former politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1997 to 2007 and Leader of the Labour Party from 1994 to 2007. He previously served as Leader of th ...

, Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak

Muhammad Hosni El Sayed Mubarak, (; 4 May 1928 – 25 February 2020) was an Egyptian politician and military officer who served as the fourth president of Egypt from 1981 to 2011.

Before he entered politics, Mubarak was a career officer in ...

, and Sharif from the White House. Clinton announced the attacks in a TV address, saying the Khost camp was "one of the most active terrorist bases in the world." He emphasized: "Our battle against terrorism ... will require strength, courage and endurance. We will not yield to this threat ... We must be prepared to do all that we can for as long as we must." Clinton also cited "compelling evidence that in Ladenwas planning to mount further attacks" in his rationale for Operation Infinite Reach.

The missiles were launched three days after Clinton testified on the Clinton–Lewinsky scandal

The Clinton–Lewinsky scandal was a sex scandal involving Bill Clinton, the president of the United States, and Monica Lewinsky, a White House intern. Their sexual relationship lasted between 1995 and 1997. Clinton ended a televised speech in ...

, and some countries, media outlets, protesters, and Republicans accused him of ordering the attacks as a diversion. The attacks also drew parallels to the then-recently released movie ''Wag the Dog

''Wag the Dog'' is a 1997 American political satire black comedy film produced and directed by Barry Levinson and starring Dustin Hoffman and Robert De Niro. The film centers on a spin doctor and a Hollywood producer who fabricate a war in Alb ...

'', which features a fictional president faking a war in Albania

Albania ( ; sq, Shqipëri or ), or , also or . officially the Republic of Albania ( sq, Republika e Shqipërisë), is a country in Southeastern Europe. It is located on the Adriatic and Ionian Seas within the Mediterranean Sea and shares l ...

to distract attention from a sex scandal. Administration officials denied any connection between the missile strikes and the ongoing scandal, and 9/11 Commission investigators found no reason to dispute those statements.

Operation Infinite Reach was covered heavily by U.S. media: About 75% of Americans knew about the strikes by the evening of August 20. The next day, 79% of respondents in a Pew Research Center

The Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan American think tank (referring to itself as a "fact tank") based in Washington, D.C.

It provides information on social issues, public opinion, and demographic trends shaping the United States and the ...

poll reported they had "followed the story 'very' or 'fairly' closely." The week after the strikes, the evening programs of the three major news networks featured 69 stories on them. In a ''Newsweek'' poll, up to 40% thought that diverting attention from the Lewinsky scandal was one objective of the strikes; according to a ''Star Tribune

The ''Star Tribune'' is the largest newspaper in Minnesota. It originated as the ''Minneapolis Tribune'' in 1867 and the competing ''Minneapolis Daily Star'' in 1920. During the 1930s and 1940s, Minneapolis's competing newspapers were consoli ...

'' poll, 31% of college-educated respondents and 60% of those "with less than a 12th grade education" believed that the attacks were motivated "a great deal" by the scandal. A ''USA Today

''USA Today'' (stylized in all uppercase) is an American daily middle-market newspaper and news broadcasting company. Founded by Al Neuharth on September 15, 1982, the newspaper operates from Gannett's corporate headquarters in Tysons, Virgini ...

''/CNN

CNN (Cable News Network) is a multinational cable news channel headquartered in Atlanta, Georgia, U.S. Founded in 1980 by American media proprietor Ted Turner and Reese Schonfeld as a 24-hour cable news channel, and presently owned by t ...

/ Gallup poll of 628 Americans showed that 47% thought it would increase terrorist attacks, while 38% thought it would lessen terrorism. A ''Los Angeles Times

The ''Los Angeles Times'' (abbreviated as ''LA Times'') is a daily newspaper that started publishing in Los Angeles in 1881. Based in the LA-adjacent suburb of El Segundo since 2018, it is the sixth-largest newspaper by circulation in the U ...

'' poll of 895 taken three days after the attack indicated that 84% believed that the operation would trigger a retaliatory terrorist attack on U.S. soil.

International reactions

While U.S. allies such asAustralia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands. With an area of , Australia is the largest country b ...

, Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwee ...

, the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and No ...

, Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

, and the Northern Alliance

The Northern Alliance, officially known as the United Islamic National Front for the Salvation of Afghanistan ( prs, جبهه متحد اسلامی ملی برای نجات افغانستان ''Jabha-yi Muttahid-i Islāmi-yi Millī barāyi Nijāt ...

supported the attacks, they were opposed by Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbe ...

, Russia, and China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

, as well as the targeted nations and other Muslim countries. German Chancellor Helmut Kohl

Helmut Josef Michael Kohl (; 3 April 1930 – 16 June 2017) was a German politician who served as Chancellor of Germany from 1982 to 1998 and Leader of the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) from 1973 to 1998. Kohl's 16-year tenure is the longe ...

said that "resolute actions by all countries" were required against terrorism, while Russian President Boris Yeltsin

Boris Nikolayevich Yeltsin ( rus, Борис Николаевич Ельцин, p=bɐˈrʲis nʲɪkɐˈla(j)ɪvʲɪtɕ ˈjelʲtsɨn, a=Ru-Boris Nikolayevich Yeltsin.ogg; 1 February 1931 – 23 April 2007) was a Soviet and Russian politician wh ...

condemned "the ineffective approach to resolving disputes without trying all forms of negotiation and diplomacy." The Taliban denounced the operation, denied charges it provided a safe haven for bin Laden, and insisted the U.S. attack killed only innocent civilians. Omar condemned the strikes and announced that Afghanistan "will never hand over bin Laden to anyone and (will) protect him with our blood at all costs." A mob in Jalalabad

Jalalabad (; Dari/ ps, جلالآباد, ) is the fifth-largest city of Afghanistan. It has a population of about 356,274, and serves as the capital of Nangarhar Province in the eastern part of the country, about from the capital Kabul. Jala ...

burned and looted the local UN office, while an Italian UN official was killed in Kabul on August 21, allegedly in response to the strikes. Thousands of anti-U.S. protesters took to the streets of Khartoum. Omar al-Bashir led an anti-U.S. rally and warned of possible reciprocation, and Martha Crenshaw notes that the strike "gained the regime some sympathy in the Arab world

The Arab world ( ar, اَلْعَالَمُ الْعَرَبِيُّ '), formally the Arab homeland ( '), also known as the Arab nation ( '), the Arabsphere, or the Arab states, refers to a vast group of countries, mainly located in Western As ...

." The Sudanese government expelled the British ambassador for Britain's support of the attacks, while protesters stormed the empty U.S. embassy. Sudan also reportedly allowed two suspected accomplices to the embassy bombings to escape. Libyan leader Muammar al-Gaddafi

Muammar Muhammad Abu Minyar al-Gaddafi, . Due to the lack of standardization of transcribing written and regionally pronounced Arabic, Gaddafi's name has been romanized in various ways. A 1986 column by ''The Straight Dope'' lists 32 spelling ...

declared his country's support for Sudan and led an anti-U.S. rally in Tripoli

Tripoli or Tripolis may refer to:

Cities and other geographic units Greece

*Tripoli, Greece, the capital of Arcadia, Greece

*Tripolis (region of Arcadia), a district in ancient Arcadia, Greece

* Tripolis (Larisaia), an ancient Greek city in t ...

. Zawahiri later equated the destruction of Al-Shifa with the September 11 attacks

The September 11 attacks, commonly known as 9/11, were four coordinated suicide terrorist attacks carried out by al-Qaeda against the United States on Tuesday, September 11, 2001. That morning, nineteen terrorists hijacked four commerc ...

.

Pakistan condemned the U.S. missile strikes as a violation of the territorial integrity of two Islamic countries, and criticized the U.S. for allegedly violating Pakistani airspace. Pakistanis protested the strikes in large demonstrations, including a 300-strong rally in Islamabad

Islamabad (; ur, , ) is the capital city of Pakistan. It is the country's ninth-most populous city, with a population of over 1.2 million people, and is federally administered by the Pakistani government as part of the Islamabad Capital ...

, where protesters burned a U.S. flag outside the U.S. Information Service center; in Karachi

Karachi (; ur, ; ; ) is the most populous city in Pakistan and 12th most populous city in the world, with a population of over 20 million. It is situated at the southern tip of the country along the Arabian Sea coast. It is the former ...

, thousands burned effigies

An effigy is an often life-size sculptural representation of a specific person, or a prototypical figure. The term is mostly used for the makeshift dummies used for symbolic punishment in political protests and for the figures burned in certai ...

of Clinton. The Pakistani government was enraged by the ISI and trainee casualties, the damage to ISI training camps, the short notice provided by the U.S., and the Americans' failure to inform Sharif of the strikes. Iran's Supreme Leader, Ali Khamenei

Sayyid Ali Hosseini Khamenei ( fa, سید علی حسینی خامنهای, ; born 19 April 1939) is a Twelver Shia ''marja and the second and current Supreme Leader of Iran, in office since 1989. He was previously the third presiden ...

, and Iraq denounced the strikes as terrorism, while Iraq also denied producing chemical weapons in Sudan. The Arab League

The Arab League ( ar, الجامعة العربية, ' ), formally the League of Arab States ( ar, جامعة الدول العربية, '), is a regional organization in the Arab world, which is located in Northern Africa, Western Africa, E ...

, holding an emergency meeting in Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo met ...

, unanimously demanded an independent investigation into the Al-Shifa facility; the League also condemned the attack on the plant as a violation of Sudanese sovereignty.

Several Islamist groups also condemned Operation Infinite Reach, and some of them threatened retaliation. Hamas

Hamas (, ; , ; an acronym of , "Islamic Resistance Movement") is a Palestinian Sunni- Islamic fundamentalist, militant, and nationalist organization. It has a social service wing, Dawah, and a military wing, the Izz ad-Din al-Qassa ...

founder Ahmed Yassin

Sheikh Ahmed Ismail Hassan Yassin ( ar, الشيخ أحمد إسماعيل حسن ياسين; 1 January 1937 – 22 March 2004) was a Palestinian politician and imam who founded Hamas, a militant Islamist and Palestinian nationalist organ ...

stated that American attacks against Muslim countries constituted an attack on Islam itself, accusing the U.S. of state terrorism