Oleg Penkovsky on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

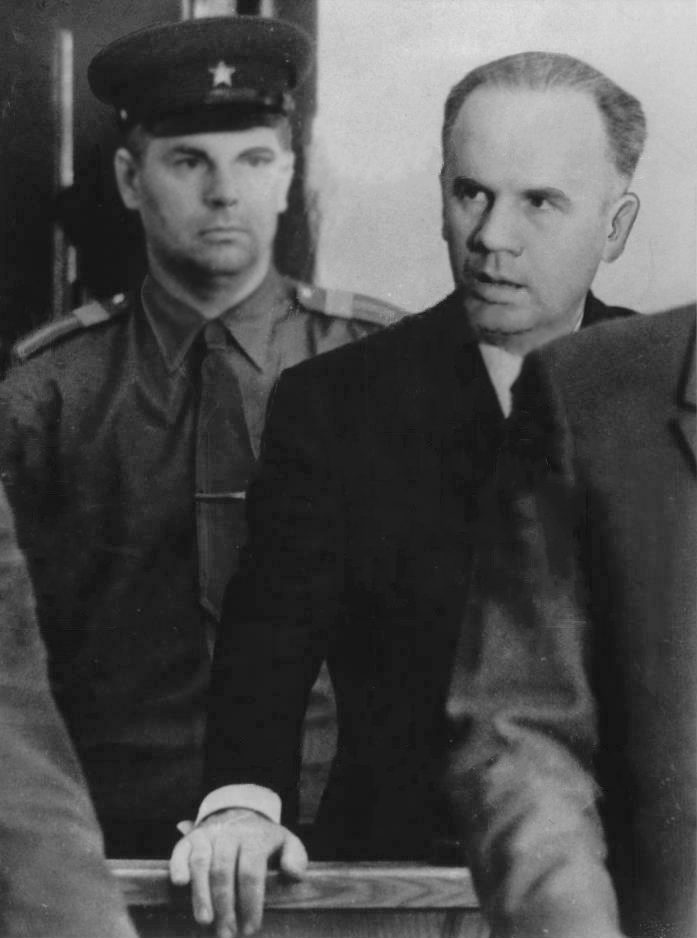

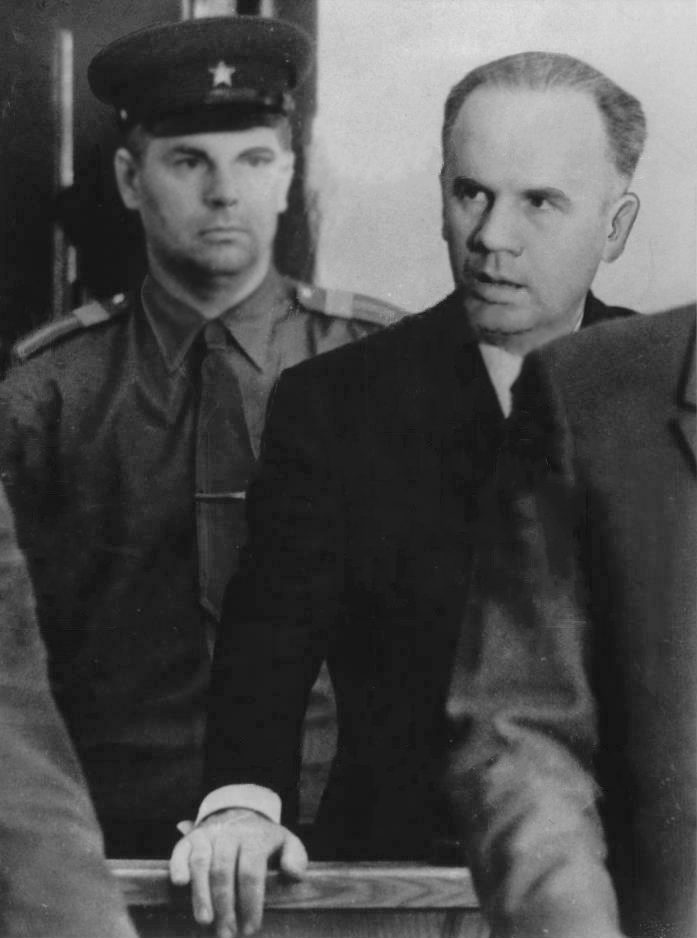

Oleg Vladimirovich Penkovsky (russian: link=no, Олег Владимирович Пеньковский; 23 April 1919 – 16 May 1963), codenamed HERO, was a Soviet

Penkovsky's American contacts received a letter from Penkovsky notifying them that a Moscow

Penkovsky's American contacts received a letter from Penkovsky notifying them that a Moscow

''Spycraft: The Secret History of the CIA's Spytechs, from Communism to al-Qaeda''

New York, Dutton, 2008. * Frederick Forsyth, ''The Deceiver'', Bantam Books, 1992

p. 43

4th line. * Viktor Suvorov, ''Devil's Mother'', Sofia, Fakel Express, 2011 , in Bulgarian language.

The Capture and Execution of Colonel Penkovsky, 1963

* Joseph J. Bulik

Penkovsky's CIA case officer * * 'Fatal Encounter' BBC TV documentary 3 May 1991, KGB, MI6 and CIA officers involved with the Penkovsky reveal their stories * {{DEFAULTSORT:Penkovsky, Oleg 1919 births 1963 deaths Soviet people executed for spying for the United States British spies against the Soviet Union GRU officers People from Vladikavkaz Russian people executed by the Soviet Union Executed people from North Ossetia–Alania Executed Soviet people from Russia Soviet military attachés Double agents

military intelligence

Military intelligence is a military discipline that uses information collection and analysis approaches to provide guidance and direction to assist commanders in their decisions. This aim is achieved by providing an assessment of data from a ...

(GRU

The Main Directorate of the General Staff of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation, rus, Гла́вное управле́ние Генера́льного шта́ба Вооружённых сил Росси́йской Федера́ци ...

) colonel during the late 1950s and early 1960s. Penkovsky informed the United States and the United Kingdom about Soviet military secrets, most importantly, the appearance and footprint of Soviet intermediate-range ballistic missile (IRBM) installations and the weakness of the Soviet intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) program. This information was decisive in allowing the US to recognize that the Soviets were placing IRBMs in Cuba before most of the missiles were operational. It also gave US President John F. Kennedy, during the Cuban Missile Crisis

The Cuban Missile Crisis, also known as the October Crisis (of 1962) ( es, Crisis de Octubre) in Cuba, the Caribbean Crisis () in Russia, or the Missile Scare, was a 35-day (16 October – 20 November 1962) confrontation between the United S ...

that followed, valuable information about Soviet weakness that allowed him to face down Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and chairman of the country's Council of Ministers from 1958 to 1964. During his rule, Khrushchev s ...

and resolve the crisis without a nuclear war.

Penkovsky was the highest-ranking Soviet official to provide intelligence for the West up until that time, and is one of several individuals credited with altering the course of the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because t ...

. He was arrested by the Soviets in October 1962, then tried and executed the following year.

Early life and military career

Penkovsky never knew his father, who was killed fighting as an officer in theWhite Army

The White Army (russian: Белая армия, Belaya armiya) or White Guard (russian: Бѣлая гвардія/Белая гвардия, Belaya gvardiya, label=none), also referred to as the Whites or White Guardsmen (russian: Бѣлогв� ...

in the Russian Civil War

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Russian Civil War

, partof = the Russian Revolution and the aftermath of World War I

, image =

, caption = Clockwise from top left:

{{flatlist,

*Soldiers ...

when he was a baby. Brought up in the North Caucasus, Penkovsky graduated from the Kiev Artillery Academy with the rank of lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations.

The meaning of lieutenant differs in different militaries (see comparative military ranks), but it is often ...

in 1939. After taking part in the Winter War

The Winter War,, sv, Vinterkriget, rus, Зи́мняя война́, r=Zimnyaya voyna. The names Soviet–Finnish War 1939–1940 (russian: link=no, Сове́тско-финская война́ 1939–1940) and Soviet–Finland War 1 ...

against Finland and in World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, he reached the rank of lieutenant-colonel

Lieutenant colonel ( , ) is a rank of commissioned officers in the armies, most marine forces and some air forces of the world, above a major and below a colonel. Several police forces in the United States use the rank of lieutenant colo ...

. In 1944, he was assigned to the headquarters of Colonel-General Sergei Varentsov, commander of artillery on the 1st Ukrainian front, who became his patron. Penkovsky was wounded in action in 1944, at about the same time as Varentsov, who appointed him his Liaison Officer. In 1945, Penkovsky married the teenage daughter of Lieutenant-General Dmitri Gapanovich, thus acquiring another high-ranking patron. On Varentsov's recommendation, he studied at the Frunze Military Academy in 1945-48, then worked as a staff officer.

Penkovsky joined the GRU

The Main Directorate of the General Staff of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation, rus, Гла́вное управле́ние Генера́льного шта́ба Вооружённых сил Росси́йской Федера́ци ...

as an officer, in 1953. In 1955 Penkovsky was appointed military attaché

A military attaché is a military expert who is attached to a diplomatic mission, often an embassy. This type of attaché post is normally filled by a high-ranking military officer, who retains a commission while serving with an embassy. Opport ...

in Ankara

Ankara ( , ; ), historically known as Ancyra and Angora, is the capital of Turkey. Located in the central part of Anatolia, the city has a population of 5.1 million in its urban center and over 5.7 million in Ankara Province, maki ...

, Turkey, but was recalled after he had reported his superior officer, and later other GRU personnel for a breach of regulations, which made him unpopular in the department. Relying once again on Varentsov's patronage, he spent nine months studying rocket artillery at Dzerzhinsky Military Academy. He was selected for the post of military attache in India, but the KGB had uncovered the story of his father's death, and he was suspended, investigated, and assigned in November 1960 to the State Committee for Science and Technology. He later worked at the Soviet Committee for Scientific Research.

Overtures to CIA and MI6

Penkovsky approached American students on theBolshoy Moskvoretsky Bridge

Bolshoy Moskvoretsky Bridge (russian: Большой Москворецкий мост, link=no) is a concrete arch bridge that spans the Moskva River in Moscow, Russia, immediately east of the Kremlin. The bridge connects Red Square with Bolsh ...

in Moscow in July 1960 and gave them a package in which he offered to spy for the U.S. He asked them to deliver it to an intelligence officer at the U.S. Embassy. The Central Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gathering, processing, ...

delayed in contacting him. When the U.S. Embassy in Moscow refused to cooperate, fearing an international incident, the CIA contacted MI6 for assistance.

A British salesman of industrial equipment to countries behind the Iron Curtain

The Iron Curtain was the political boundary dividing Europe into two separate areas from the end of World War II in 1945 until the end of the Cold War in 1991. The term symbolizes the efforts by the Soviet Union (USSR) to block itself and its ...

, Greville Wynne

Greville Maynard Wynne (19 March 1919 – 28 February 1990) was a British engineer and businessman recruited by MI6 because of his frequent travel to Eastern Europe. He acted as a courier to transport top-secret information to London from ...

, was recruited by MI6 to communicate with Penkovksy. In his autobiography, Wynne says that he was carefully developed by British intelligence over many years with the specific task of making contact with Penkovsky.

The first meeting between Penkovsky and two American and two British intelligence officers occurred during a visit by Penkovsky to London in April 1961. For the following 18 months, Penkovsky supplied a tremendous amount of information to the CIA–MI6 team of handlers, including documents demonstrating that the Soviet nuclear arsenal was much smaller than Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and chairman of the country's Council of Ministers from 1958 to 1964. During his rule, Khrushchev s ...

claimed or the CIA had thought and that the Soviets were not yet capable of producing a large number of ICBMs. This information was invaluable to President John F. Kennedy in negotiating with Nikita Khrushchev for the removal of the Soviet IRBMs from Cuba.

Peter Wright, a former British MI5

The Security Service, also known as MI5 ( Military Intelligence, Section 5), is the United Kingdom's domestic counter-intelligence and security agency and is part of its intelligence machinery alongside the Secret Intelligence Service (MI6), G ...

officer known for his scathing condemnation of the leadership of British intelligence during most of the Cold War, believed that Penkovsky was a fake defection. Wright noted that, unlike Igor Gouzenko and other earlier defectors, Penkovsky did not reveal the names of any Soviet agents in the West but only provided organisational detail, much of which was known already. Some of the documents provided were originals, which Wright thought could not have been easily taken from their sources. Wright was bitter towards British intelligence, reportedly believing that it should have adopted his proposed methods to identify British/Soviet agents. In Wright's view, the failure of British intelligence leaders to listen to him caused them to become paralysed when British/Soviet agents defected to the Soviet Union; in his book, ''Spycatcher

''Spycatcher: The Candid Autobiography of a Senior Intelligence Officer'' (1987) is a memoir written by Peter Wright, former MI5 officer and Assistant Director, and co-author Paul Greengrass. He drew on his own experiences and research in ...

'', he suggests that his hypothesis had to be true, and that the Soviets were aware of this paralysis and planted Penkovsky.

In his memoir ''Spycatcher: The Candid Autobiography of a Senior Intelligence Officer'' (1987), written with journalist Paul Greengrass

Paul Greengrass (born 13 August 1955) is a British film director, film producer, screenwriter and former journalist. He specialises in dramatisations of historic events and is known for his signature use of hand-held cameras.

His early film ' ...

, Wright says:

Former KGB major-general Oleg Kalugin does not mention Penkovsky in his comprehensive memoir about his career in intelligence against the West. The KGB defector Vladimir N. Sakharov suggests Penkovsky was genuine, saying: "I knew about the ongoing KGB reorganisation precipitated by Oleg Penkovsky's case and Yuri Nosenko's defection. The party was not satisfied with KGB performance ... I knew many heads in the KGB had rolled again, as they had after Stalin". While the weight of opinion seems to be that Penkovsky was genuine, the debate underscores the difficulty faced by all intelligence agencies of determining information offered from the enemy. In a meeting with Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta

Leon Edward Panetta (born June 28, 1938) is an American Democratic Party politician who has served in several different public office positions, including Secretary of Defense, CIA Director, White House Chief of Staff, Director of the Office of ...

, the head of Russia's foreign intelligence service, Mikhail Fradkov

Mikhail Yefimovich Fradkov ( rus, Михаи́л Ефи́мович Фрадко́в, p=mʲɪxɐˈil jɪˈfʲiməvʲɪtɕ frɐtˈkof; born 1 September 1950) is a Russian politician who served as Prime Minister of Russia from 2004 to 2007. An In ...

named Penkovsky as Russia's biggest intelligence failure.

Cuban Missile Crisis

The Soviet leadership began the deployment of nuclear missiles, in the belief that Washington would not detect the Cuban missile sites until it was too late to do anything about them. Penkovsky provided plans and descriptions of the nuclear rocket launch sites in Cuba to the West. This information allowed the West to identify the missile sites from the low-resolution pictures provided by US U-2 spy planes. The documents provided by Penkovsky showed that the Soviet Union was not prepared for war in the area, which emboldened Kennedy to risk the operation in Cuba. Former GRU captainViktor Suvorov

Vladimir Bogdanovich Rezun (russian: link=no, Владимир Богданович Резун; born 20 April 1947), known by his pseudonym of Viktor Suvorov () is a former Soviet GRU officer who is the author of non-fiction books about World ...

, who defected to the UK in 1978, later wrote in his book on Soviet intelligence, "historians will remember with gratitude the name of the GRU Colonel Oleg Penkovsky. Thanks to his priceless information the Cuban crisis was not transformed into a last World War".

Penkovsky's activities were revealed by Jack Dunlap, a National Security Agency

The National Security Agency (NSA) is a national-level intelligence agency of the United States Department of Defense, under the authority of the Director of National Intelligence (DNI). The NSA is responsible for global monitoring, collecti ...

(NSA) employee and Soviet spy working for the KGB. Top KGB officers had known for more than a year that Penkovsky was a British agent, but they protected their source, a highly placed mole in MI6. Jack Dunlap was just another source they had to protect. They worked hard, shadowing British diplomats, to build up a "discovery case" against Penkovsky so that they could arrest him without throwing suspicion on their moles. Their caution in this matter may have led to the missiles being discovered earlier than the Soviets would have preferred. After a West German agent overheard a remark at Stasi

The Ministry for State Security, commonly known as the (),An abbreviation of . was the state security service of the East Germany from 1950 to 1990.

The Stasi's function was similar to the KGB, serving as a means of maintaining state autho ...

headquarters, paraphrased as "I wonder how things are going in Cuba" he passed it on to the CIA.

Penkovsky was arrested on 22 October 1962. This was prior to President Kennedy's address to the US revealing that U-2 spy plane photographs had confirmed intelligence reports that the Soviets were installing medium-range nuclear missiles in Cuba, in what was known as Operation Anadyr. President Kennedy was deprived of information from a potentially important intelligence agent, such as reporting that Nikita Khrushchev was already looking for ways to defuse the situation, which might have lessened the tension during the ensuing 13-day stand-off. That information might have reduced the pressure on Kennedy to launch an invasion of the island, which could have risked Soviet use of ''9K52 Luna-M

The 9K52 ''Luna-M'' (russian: Луна; en, moon, NATO reporting name FROG-7) is a Soviet short-range artillery rocket system which fires unguided and spin-stabilized 9M21 rockets. It was originally developed in the 1960s to provide divisiona ...

''-class tactical nuclear weapon

A tactical nuclear weapon (TNW) or non-strategic nuclear weapon (NSNW) is a nuclear weapon that is designed to be used on a battlefield in military situations, mostly with friendly forces in proximity and perhaps even on contested friendly territo ...

s against U.S. troops.

Arrest and death

Penkovsky's American contacts received a letter from Penkovsky notifying them that a Moscow

Penkovsky's American contacts received a letter from Penkovsky notifying them that a Moscow dead drop

A dead drop or dead letter box is a method of espionage tradecraft used to pass items or information between two individuals (e.g., a case officer and an agent, or two agents) using a secret location. By avoiding direct meetings, individuals c ...

had been loaded. Upon servicing the dead drop, the American handler was arrested, signaling that Penkovsky had been apprehended by Soviet authorities. Penkovsky was executed but there are conflicting reports about the manner of his death. Alexander Zagvozdin, Chief KGB interrogator for the investigation, stated that Penkovsky had been "questioned perhaps a hundred times" and that he had been shot and cremated. The noted Soviet sculptor Ernst Neizvestny

Ernst Iosifovich Neizvestny (russian: Эрнст Ио́сифович Неизве́стный; 9 April 1925 – 9 August 2016) was a Russian sculptor, painter, graphic artist, and art philosopher. He emigrated to the U.S. in 1976 and lived and ...

said that he had been told by the director of the Donskoye Cemetery crematorium "how Penkovsky ad beenexecuted by 'fire'". A similar description was later included in Ernest Volkman's popular history book about spies, Tom Clancy

Thomas Leo Clancy Jr. (April 12, 1947 – October 1, 2013) was an American novelist. He is best known for his technically detailed espionage and military-science storylines set during and after the Cold War. Seventeen of his novels have b ...

's novel ''Red Rabbit

''Red Rabbit'' is a spy thriller novel, written by Tom Clancy and released on August 5, 2002. The plot occurs a few months after the events of ''Patriot Games'' (1987), and incorporates the 1981 assassination attempt on Pope John Paul II. Main ...

'' and in Viktor Suvorov's book ''Aquarium''. In a 2010 interview, Suvorov denied that the man in the film was Penkovsky and said that he had been shot. Greville Wynne

Greville Maynard Wynne (19 March 1919 – 28 February 1990) was a British engineer and businessman recruited by MI6 because of his frequent travel to Eastern Europe. He acted as a courier to transport top-secret information to London from ...

, in his book ''The Man from Odessa,'' claimed that Penkovsky killed himself. Wynne had worked as both Penkovsky's contact and courier; both men were arrested by the Soviets in October 1962.

Repercussions

The Soviet public was first told of Penkovsky's arrest more than seven weeks later, when ''Pravda

''Pravda'' ( rus, Правда, p=ˈpravdə, a=Ru-правда.ogg, "Truth") is a Russian broadsheet newspaper, and was the official newspaper of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, when it was one of the most influential papers in the ...

'' named Wynne and Jacobs as his contacts, without naming anyone else. In May 1963, after his trial, ''Izvestya'' reported that Varentsov, who had since achieved the rank of Chief Marshal

Marshal is a term used in several official titles in various branches of society. As marshals became trusted members of the courts of Medieval Europe, the title grew in reputation. During the last few centuries, it has been used for elevated o ...

of Artillery and Commander in Chief of Rocket Forces and candidate member of the Central Committee

Central committee is the common designation of a standing administrative body of communist parties, analogous to a board of directors, of both ruling and nonruling parties of former and existing socialist states. In such party organizations, the ...

had been demoted to the rank of Major General. In June he was expelled from the Central Committee for 'having relaxed his political vigilance.' Three other officers were also disciplined. The head of the GRU, Ivan Serov

Ivan Alexandrovich Serov (russian: Ива́н Алекса́ндрович Серóв; 13 August 1905 – 1 July 1990) was a Russian Soviet intelligence officer who served as the head of the KGB between March 1954 and December 1958, as well as ...

was sacked during the same period. He was reputedly on friendly terms with Penkovsky, which is very likely to have been a cause of his fall.

Portrayal in popular culture

Penkovsky was portrayed by Christopher Rozycki in the 1985BBC Television

BBC Television is a service of the BBC. The corporation has operated a public broadcast television service in the United Kingdom, under the terms of a royal charter, since 1927. It produced television programmes from its own studios from 193 ...

serial ''Wynne and Penkovsky''. His spying career was the subject of episode 1 of the 2007 BBC Television docudrama ''Nuclear Secrets

''Nuclear Secrets'', aka ''Spies, Lies and the Superbomb'', is a 2007 BBC Television docudrama series which looks at the race for nuclear supremacy from the Manhattan Project through to Pakistan's nuclear weapons programme.

Production

The serie ...

'', titled "The Spy from Moscow" in which he was portrayed by Mark Bonnar. The programme featured original covert KGB footage showing Penkovsky photographing classified information and meeting up with Janet Chisholm

Janet Chisholm (6 May 1929 – 23 July 2004), born Janet Anne Deane, was a British MI6 agent during the Cold War.

Early life

She was born in Kasauli, India to a Royal Engineers officer. She was educated Queen Anne's School, Caversham, in Berk ...

, a British MI6 agent stationed in Moscow. It was broadcast on 15 January 2007.

Penkovsky was referred to in four of Tom Clancy

Thomas Leo Clancy Jr. (April 12, 1947 – October 1, 2013) was an American novelist. He is best known for his technically detailed espionage and military-science storylines set during and after the Cold War. Seventeen of his novels have b ...

's Jack Ryan espionage novels: ''The Hunt for Red October

''The Hunt for Red October'' is the debut novel by American author Tom Clancy, first published on October 1, 1984, by the Naval Institute Press. It depicts Soviet submarine captain Marko Ramius as he seemingly goes rogue with his country's cut ...

'' (1984), '' The Cardinal of the Kremlin'' (1988), ‘’The Bear and the Dragon

''The Bear and the Dragon'' is a techno-thriller novel, written by Tom Clancy and released on August 21, 2000. A direct sequel to ''Executive Orders'' (1996), President Jack Ryan deals with a war between Russia and China, referred respectively ...

’’ (2000) and ''Red Rabbit

''Red Rabbit'' is a spy thriller novel, written by Tom Clancy and released on August 5, 2002. The plot occurs a few months after the events of ''Patriot Games'' (1987), and incorporates the 1981 assassination attempt on Pope John Paul II. Main ...

'' (2002). In the Jack Ryan universe, he is described as the agent who recruited Colonel Mikhail Filitov as a CIA agent (code-name CARDINAL) and had urged Filitov to betray him to solidify his position as the West's top spy in the Soviet hierarchy. The "cremated alive" hypothesis appears in several Clancy novels, though Clancy never identified Penkovsky as the executed spy. Penkovsky's fate is also mentioned in the Nelson DeMille spy novel '' The Charm School'' (1988).

Penkovsky was portrayed by Eduard Bezrodniy in the 2014 Polish thriller '' Jack Strong'', about Ryszard Kukliński, another Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because t ...

spy. His character's execution was the opening scene for the movie. Penkovsky was portrayed by Merab Ninidze

Merab Ninidze ( ka, მერაბ ნინიძე; born 3 November 1965) is a Georgian actor. In the English-speaking world, he is best known for the roles of Walter Redlich in ''Nowhere in Africa'' and Oleg Penkovsky in '' The Courier''.

...

in the 2020 British film '' The Courier'', in which Benedict Cumberbatch

Benedict Timothy Carlton Cumberbatch (born 19 July 1976) is an English actor. Known for his work on screen and stage, he has received various accolades, including a British Academy Television Award, a Primetime Emmy Award and a Laurence Oli ...

played Greville Wynne.

See also

* Gervase Cowell *George Kisevalter

George Kisevalter (April 4, 1910 – October 1, 1997) was an American operations officer of the CIA, who handled Major Pyotr Popov, the first Soviet GRU officer run by the CIA. He had some involvement with Soviet intelligence Colonel Oleg Pen ...

References

Sources

*Further reading

* * ::Note: The book was commissioned by theCentral Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gathering, processing, ...

::see: .

:::A 1976 Senate commission stated that "the book was prepared and written by witting agency assets who drew on actual case materials."

::See:

::Note: Author Frank Gibney denied the CIA had forged the provided source material, which was also the opinion of Robert Conquest

George Robert Acworth Conquest (15 July 1917 – 3 August 2015) was a British historian and poet.

A long-time research fellow at Stanford University's Hoover Institution, Conquest was most notable for his work on the Soviet Union. His books ...

. Other dismissed the book as propaganda and having no historic value.

* Robert Wallace and H. Keith Melton, with Henry R. Schlesinger''Spycraft: The Secret History of the CIA's Spytechs, from Communism to al-Qaeda''

New York, Dutton, 2008. * Frederick Forsyth, ''The Deceiver'', Bantam Books, 1992

p. 43

4th line. * Viktor Suvorov, ''Devil's Mother'', Sofia, Fakel Express, 2011 , in Bulgarian language.

External links

* * John SimkinSpartacus Educational

Spartacus Educational is a free online encyclopedia with essays and other educational material on a wide variety of historical subjects principally British history from 1700 and the history of the United States.

Based in the United Kingdom, Spart ...

* cia.goThe Capture and Execution of Colonel Penkovsky, 1963

* Joseph J. Bulik

Penkovsky's CIA case officer * * 'Fatal Encounter' BBC TV documentary 3 May 1991, KGB, MI6 and CIA officers involved with the Penkovsky reveal their stories * {{DEFAULTSORT:Penkovsky, Oleg 1919 births 1963 deaths Soviet people executed for spying for the United States British spies against the Soviet Union GRU officers People from Vladikavkaz Russian people executed by the Soviet Union Executed people from North Ossetia–Alania Executed Soviet people from Russia Soviet military attachés Double agents