Old Persian Cuneiform on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Old Persian cuneiform is a semi-alphabetic

The first mention of ancient inscriptions in the newly-discovered ruins of Persepolis was made by the Spain and Portugal ambassador to Persia, Antonio de Goueca in a 1611 publication. Various travelers then made attempts at illustrating these new inscription, which in 1700 Thomas Hyde first called "cuneiform", but deemed were no more than decorative friezes.

Proper attempts at deciphering Old Persian cuneiform started with faithful copies of cuneiform inscriptions, which first became available in 1711 when duplicatas of Darius's inscriptions were published by

The first mention of ancient inscriptions in the newly-discovered ruins of Persepolis was made by the Spain and Portugal ambassador to Persia, Antonio de Goueca in a 1611 publication. Various travelers then made attempts at illustrating these new inscription, which in 1700 Thomas Hyde first called "cuneiform", but deemed were no more than decorative friezes.

Proper attempts at deciphering Old Persian cuneiform started with faithful copies of cuneiform inscriptions, which first became available in 1711 when duplicatas of Darius's inscriptions were published by

In 1802,

In 1802,

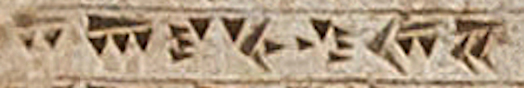

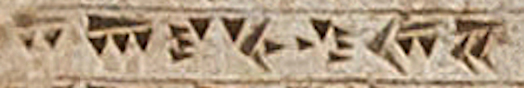

File:Niebuhr inscription 1 with word for King.jpg, Niebuhr inscription 1, with the words "King" () highlighted: "King" and "King of Kings" appear in sequence.

File:Niebuhr inscription 2 with word for King.jpg, Niebuhr inscription 2, with the words "King" highlighted: "King", "King of Kings" and again "King" appear in sequence.

Looking at similarities in character sequences, he made the hypothesis that the father of the ruler in one inscription would possibly appear as the first name in the other inscription: the first word in Niebuhr 1 () indeed corresponded to the 6th word in Niebuhr 2.

Looking at the length of the character sequences, and comparing with the names and genealogy of the Achaemenid kings as known from the Greeks, also taking into account the fact that the father of one of the rulers in the inscriptions didn't have the attribute "king", he made the correct guess that this could be no other than

Looking at similarities in character sequences, he made the hypothesis that the father of the ruler in one inscription would possibly appear as the first name in the other inscription: the first word in Niebuhr 1 () indeed corresponded to the 6th word in Niebuhr 2.

Looking at the length of the character sequences, and comparing with the names and genealogy of the Achaemenid kings as known from the Greeks, also taking into account the fact that the father of one of the rulers in the inscriptions didn't have the attribute "king", he made the correct guess that this could be no other than

It was only in 1823 that Grotefend's discovery was confirmed, when the French archaeologist Champollion, who had just deciphered Egyptian hieroglyphs, was able to read the Egyptian dedication of a quadrilingual hieroglyph-cuneiform inscription on an alabaster vase in the Cabinet des Médailles, the "

It was only in 1823 that Grotefend's discovery was confirmed, when the French archaeologist Champollion, who had just deciphered Egyptian hieroglyphs, was able to read the Egyptian dedication of a quadrilingual hieroglyph-cuneiform inscription on an alabaster vase in the Cabinet des Médailles, the "

The script encodes three vowels, ''a'', ''i'', ''u'', and twenty-two consonants, ''k'', ''x'', ''g'', ''c'', ''ç'', ''j'', ''t'', ''θ'', ''d'', ''p'', ''f'', ''b'', ''n'', ''m'', ''y'', ''v'', ''r'', ''l'', ''s'', ''z'', ''š'', and ''h''. Old Persian contains two sets of consonants: those whose shape depends on the following vowel and those whose shape is independent of the following vowel. The consonant symbols that depend on the following vowel act like the consonants in

The script encodes three vowels, ''a'', ''i'', ''u'', and twenty-two consonants, ''k'', ''x'', ''g'', ''c'', ''ç'', ''j'', ''t'', ''θ'', ''d'', ''p'', ''f'', ''b'', ''n'', ''m'', ''y'', ''v'', ''r'', ''l'', ''s'', ''z'', ''š'', and ''h''. Old Persian contains two sets of consonants: those whose shape depends on the following vowel and those whose shape is independent of the following vowel. The consonant symbols that depend on the following vowel act like the consonants in

Although based on a logo-syllabic prototype, all vowels but short /a/ are written and so the system is essentially an

Although based on a logo-syllabic prototype, all vowels but short /a/ are written and so the system is essentially an

Download "Kakoulookiam", Old Persian Cuneiform Font (Unicode)

Download "Khosrau", Old Persian Cuneiform Font (Unicode)

Download "Behistun", Old Persian Cuneiform Font (Unicode)

(install one of the above fonts and see this page)

(learn how to configure your browser)

Achaemenid Royal Inscriptions

(Livius.org) *

{{list of writing systems Persian orthography Old Persian language Obsolete writing systems Syllabary writing systems Alphabets Cuneiform Persian scripts

cuneiform script

Cuneiform is a logo- syllabic script that was used to write several languages of the Ancient Middle East. The script was in active use from the early Bronze Age until the beginning of the Common Era. It is named for the characteristic wedge-s ...

that was the primary script for Old Persian. Texts written in this cuneiform have been found in Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

( Persepolis, Susa

Susa ( ; Middle elx, 𒀸𒋗𒊺𒂗, translit=Šušen; Middle and Neo- elx, 𒋢𒋢𒌦, translit=Šušun; Neo- Elamite and Achaemenid elx, 𒀸𒋗𒐼𒀭, translit=Šušán; Achaemenid elx, 𒀸𒋗𒐼, translit=Šušá; fa, شوش ...

, Hamadan, Kharg Island), Armenia

Armenia (), , group=pron officially the Republic of Armenia,, is a landlocked country in the Armenian Highlands of Western Asia.The UNbr>classification of world regions places Armenia in Western Asia; the CIA World Factbook , , and ''O ...

, Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern, and Southeast Europe, Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, S ...

( Gherla), Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with a small portion on the Balkan Peninsula ...

( Van Fortress), and along the Suez Canal.Kent, R. G.: "Old Persian: Grammar Texts Lexicon", page 6. American Oriental Society, 1950. They were mostly inscriptions from the time period of Darius I

Darius I ( peo, 𐎭𐎠𐎼𐎹𐎺𐎢𐏁 ; grc-gre, Δαρεῖος ; – 486 BCE), commonly known as Darius the Great, was a Persian ruler who served as the third King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, reigning from 522 BCE until his ...

, such as the DNa inscription

The DNa inscription (acronym for ) is a famous Achaemenid-era inscription located in Naqsh-e Rostam, Iran. It dates to , the time of Darius the Great, and appears in the top-left corner of the façade of his tomb.

Content

The inscription menti ...

, as well as his son, Xerxes I. Later kings down to Artaxerxes III used more recent forms of the language classified as "pre-Middle Persian".

History

Old Persian cuneiform is loosely inspired by the Sumero-Akkadian Akkadian or Accadian may refer to:

* Akkadians, inhabitants of the Akkadian Empire

* Akkadian language, an extinct Eastern Semitic language

* Akkadian literature, literature in this language

* Akkadian cuneiform

Cuneiform is a logo-syllabic ...

cuneiform

Cuneiform is a logo- syllabic script that was used to write several languages of the Ancient Middle East. The script was in active use from the early Bronze Age until the beginning of the Common Era. It is named for the characteristic wedge- ...

; however, only one glyph is directly derived from it – ''l(a)'' (), from ''la'' (). (''la'' did not occur in native Old Persian words, but was found in Akkadian borrowings.)

Scholars today mostly agree that the Old Persian script was invented by about 525 BC to provide monument inscriptions for the Achaemenid

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire (; peo, wikt:𐎧𐏁𐏂𐎶, 𐎧𐏁𐏂, , ), also called the First Persian Empire, was an History of Iran#Classical antiquity, ancient Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great in 550 BC. Bas ...

king Darius I

Darius I ( peo, 𐎭𐎠𐎼𐎹𐎺𐎢𐏁 ; grc-gre, Δαρεῖος ; – 486 BCE), commonly known as Darius the Great, was a Persian ruler who served as the third King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, reigning from 522 BCE until his ...

, to be used at Behistun. While a few Old Persian texts seem to be inscribed during the reigns of Cyrus the Great

Cyrus II of Persia (; peo, 𐎤𐎢𐎽𐎢𐏁 ), commonly known as Cyrus the Great, was the founder of the Achaemenid Empire, the first Persian empire. Schmitt Achaemenid dynasty (i. The clan and dynasty) Under his rule, the empire embraced ...

(CMa, CMb, and CMc, all found at Pasargadae

Pasargadae (from Old Persian ''Pāθra-gadā'', "protective club" or "strong club"; Modern Persian: ''Pāsārgād'') was the capital of the Achaemenid Empire under Cyrus the Great (559–530 BC), who ordered its construction and the locatio ...

), the first Achaemenid emperor, or Arsames and Ariaramnes

Ariaramnes (Old Persian: 𐎠𐎼𐎡𐎹𐎠𐎼𐎶𐎴 ''Ariyāramna''; "peace of the Arya") was a great-uncle of Cyrus the Great and the great-grandfather of Darius I, and perhaps the king of Parsa, the ancient core kingdom of Persia.

__NOT ...

(AsH and AmH, both found at Hamadan), grandfather and great-grandfather of Darius I, all five, specially the later two, are generally agreed to have been later inscriptions.

Around the time period in which Old Persian was used, nearby languages included Elamite and Akkadian Akkadian or Accadian may refer to:

* Akkadians, inhabitants of the Akkadian Empire

* Akkadian language, an extinct Eastern Semitic language

* Akkadian literature, literature in this language

* Akkadian cuneiform

Cuneiform is a logo-syllabic ...

. One of the main differences between the writing systems of these languages is that Old Persian is a semi-alphabet while Elamite and Akkadian Akkadian or Accadian may refer to:

* Akkadians, inhabitants of the Akkadian Empire

* Akkadian language, an extinct Eastern Semitic language

* Akkadian literature, literature in this language

* Akkadian cuneiform

Cuneiform is a logo-syllabic ...

were syllabic. In addition, while Old Persian is written in a consistent semi-alphabetic system, Elamite and Akkadian used borrowings from other languages, creating mixed systems.

Decipherment

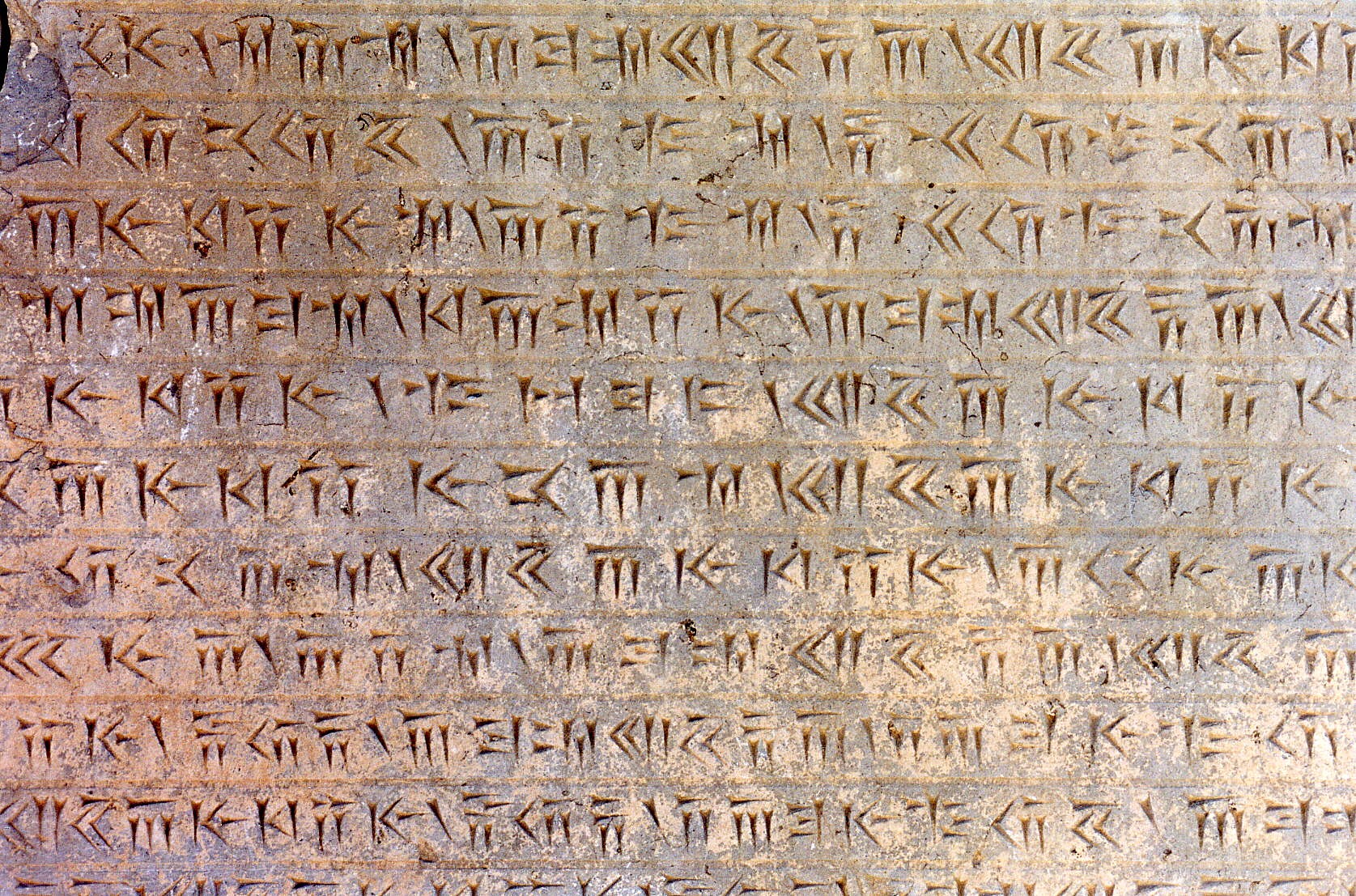

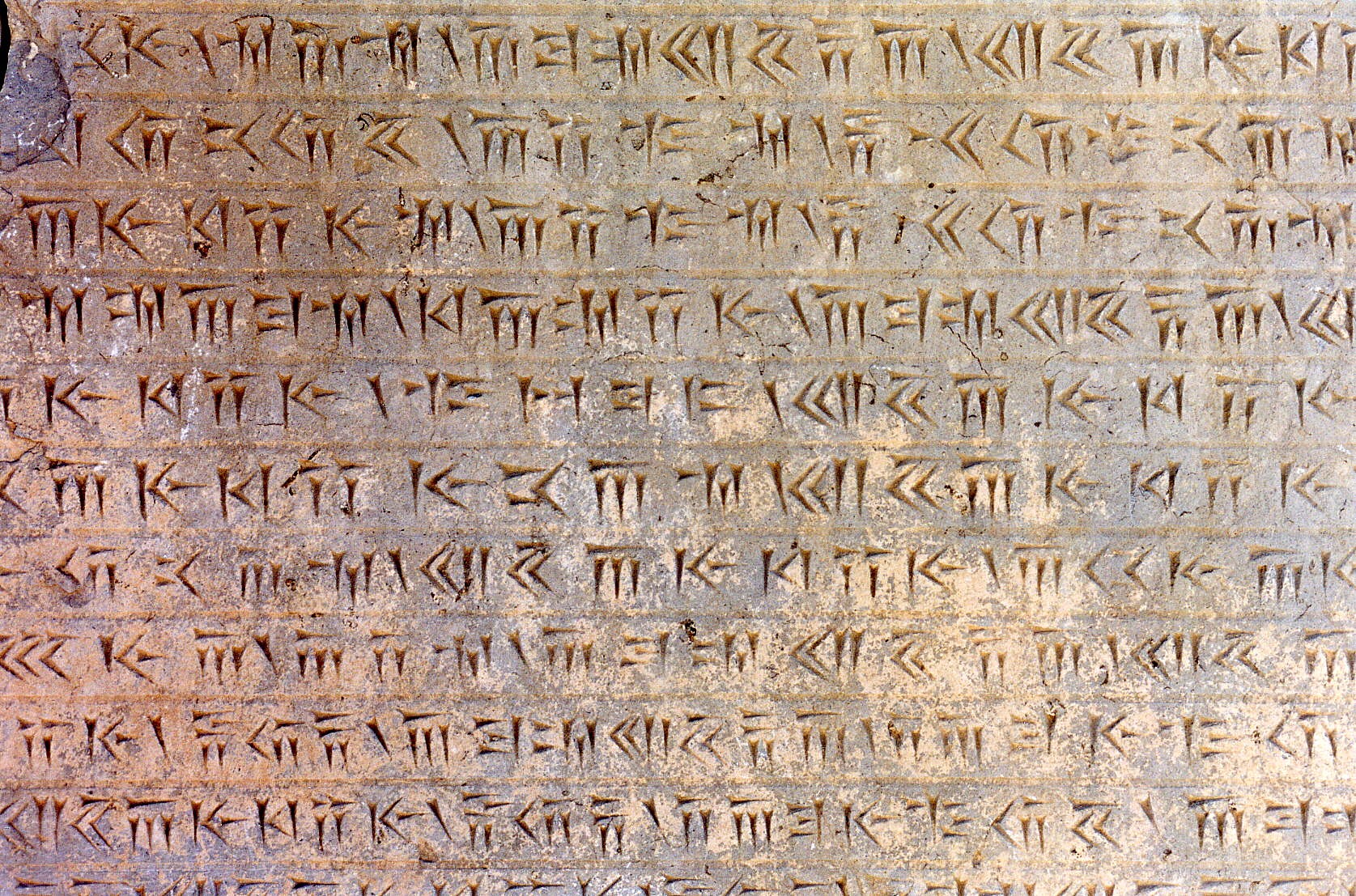

Old Persian cuneiform was only deciphered by a series of guesses, in the absence of bilingual documents connecting it to a known language. Various characteristics of sign series, such as length or recurrence of signs, allowed researchers to hypothesize about their meaning, and to discriminate between the various possible historically known kings, and then to create a correspondence between each cuneiform and a specific sound.Archaeological records of cuneiform inscriptions

The first mention of ancient inscriptions in the newly-discovered ruins of Persepolis was made by the Spain and Portugal ambassador to Persia, Antonio de Goueca in a 1611 publication. Various travelers then made attempts at illustrating these new inscription, which in 1700 Thomas Hyde first called "cuneiform", but deemed were no more than decorative friezes.

Proper attempts at deciphering Old Persian cuneiform started with faithful copies of cuneiform inscriptions, which first became available in 1711 when duplicatas of Darius's inscriptions were published by

The first mention of ancient inscriptions in the newly-discovered ruins of Persepolis was made by the Spain and Portugal ambassador to Persia, Antonio de Goueca in a 1611 publication. Various travelers then made attempts at illustrating these new inscription, which in 1700 Thomas Hyde first called "cuneiform", but deemed were no more than decorative friezes.

Proper attempts at deciphering Old Persian cuneiform started with faithful copies of cuneiform inscriptions, which first became available in 1711 when duplicatas of Darius's inscriptions were published by Jean Chardin

Jean Chardin (16 November 1643 – 5 January 1713), born Jean-Baptiste Chardin, and also known as Sir John Chardin, was a French jeweller and traveller whose ten-volume book ''The Travels of Sir John Chardin'' is regarded as one of the finest ...

.Kent, R. G.: "Old Persian: Grammar Texts Lexicon", page 9. American Oriental Society, 1950. Around 1764, Carsten Niebuhr

Carsten Niebuhr, or Karsten Niebuhr (17 March 1733 Lüdingworth – 26 April 1815 Meldorf, Dithmarschen), was a German mathematician, cartographer, and explorer in the service of Denmark. He is renowned for his participation in the Royal Danish ...

visited the ruins of Persepolis, and was able to make excellent copies of the inscriptions, identifying "three different alphabets". His faithful copies of the cuneiform inscriptions at Persepolis proved to be a key turning-point in the decipherment of cuneiform, and the birth of Assyriology.

The set of characters that would later be known as Old Persian cuneiform, was soon perceived as being the simplest of the various types of cuneiform scripts that has been encountered, and because of this was understood as a prime candidate for decipherment. Niebuhr identified that there were only 42 characters in this category of inscriptions, which he named "Class I", and affirmed that this must therefore be an alphabetic script.

Münter guesses the word for "king" (1802)

In 1802,

In 1802, Friedrich Münter

Friedrich Christian Carl Heinrich Münter (14 October 1761 – 9 April 1830) was a German-Danish scholar, theologian, and Bishop of Zealand from 1808 until his death. His name has also been recorded as Friederich Münter.

In addition to his posi ...

confirmed that "Class I" characters (today called "Old Persian cuneiform") were probably alphabetical, also because of the small number of different signs forming inscriptions. He proved that they belonged to the Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire (; peo, 𐎧𐏁𐏂, , ), also called the First Persian Empire, was an ancient Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great in 550 BC. Based in Western Asia, it was contemporarily the largest em ...

, which led to the suggestion that the inscriptions were in the Old Persian language and probably mentioned Achaemenid kings. He identified a highly recurring group of characters in these inscriptions: . Because of its high recurrence and length, he guessed that this must be the word for "king" (which he guessed must be pronounced ''kh-sha-a-ya-th-i-ya'', now known to be pronounced in Old Persian ''xšāyaθiya''). He guessed correctly, but that would only be known for sure several decades later. Münter also understood that each word was separated from the next by a backslash sign ().

Grotefend guesses the names of individual rulers (1802–1815)

Grotefend extended this work by realizing, based on the known inscriptions of much later rulers (the Pahlavi inscriptions of the Sasanian emperors), that a king's name is often followed by "great king, king of kings" and the name of the king's father.Kent, R. G.: "Old Persian: Grammar Texts Lexicon", page 10. American Oriental Society, 1950. This understanding of the structure of monumental inscriptions in Old Persian was based on the work of Anquetil-Duperron, who had studied Old Persian through theZoroastrian

Zoroastrianism is an Iranian religion and one of the world's oldest organized faiths, based on the teachings of the Iranian-speaking prophet Zoroaster. It has a dualistic cosmology of good and evil within the framework of a monotheisti ...

Avestas in India, and Antoine Isaac Silvestre de Sacy

Antoine Isaac, Baron Silvestre de Sacy (; 21 September 175821 February 1838), was a French nobleman, linguist and orientalist. His son, Ustazade Silvestre de Sacy, became a journalist.

Life and works

Early life

Silvestre de Sacy was born in Par ...

, who had decrypted the monumental Pahlavi inscriptions of the Sasanian emperors.

Grotefend focused on two inscriptions from Persepolis, called the " Niebuhr inscriptions", which seemed to use the words "King" and "King of Kings" guessed by Münter, and which seemed to have broadly similar content except for what he thought must be the names of kings:

Looking at similarities in character sequences, he made the hypothesis that the father of the ruler in one inscription would possibly appear as the first name in the other inscription: the first word in Niebuhr 1 () indeed corresponded to the 6th word in Niebuhr 2.

Looking at the length of the character sequences, and comparing with the names and genealogy of the Achaemenid kings as known from the Greeks, also taking into account the fact that the father of one of the rulers in the inscriptions didn't have the attribute "king", he made the correct guess that this could be no other than

Looking at similarities in character sequences, he made the hypothesis that the father of the ruler in one inscription would possibly appear as the first name in the other inscription: the first word in Niebuhr 1 () indeed corresponded to the 6th word in Niebuhr 2.

Looking at the length of the character sequences, and comparing with the names and genealogy of the Achaemenid kings as known from the Greeks, also taking into account the fact that the father of one of the rulers in the inscriptions didn't have the attribute "king", he made the correct guess that this could be no other than Darius the Great

Darius I ( peo, 𐎭𐎠𐎼𐎹𐎺𐎢𐏁 ; grc-gre, Δαρεῖος ; – 486 BCE), commonly known as Darius the Great, was a Persian ruler who served as the third King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, reigning from 522 BCE until his d ...

, his father Hystapes, who was not a king, and his son the famous Xerxes. The inscriptions were made around this time; there were only two instances where a ruler came to power without being a previous king's son. They were Darius the Great and Cyrus the Great

Cyrus II of Persia (; peo, 𐎤𐎢𐎽𐎢𐏁 ), commonly known as Cyrus the Great, was the founder of the Achaemenid Empire, the first Persian empire. Schmitt Achaemenid dynasty (i. The clan and dynasty) Under his rule, the empire embraced ...

, both of whom became emperor by revolt. The deciding factors between these two choices were the names of their fathers and sons. Darius's father was Hystaspes and his son was Xerxes, while Cyrus' father was Cambyses I and his son was Cambyses II. Within the text, the father and son of the king had different groups of symbols for names so Grotefend assumed that the king must have been Darius.

These connections allowed Grotefend to figure out the cuneiform characters that are part of Darius, Darius's father Hystaspes, and Darius's son Xerxes. He equated the letters with the name ''d-a-r-h-e-u-sh'' for Darius, as known from the Greeks. This identification was correct, although the actual Persian spelling was ''da-a-ra-ya-va-u-sha'', but this was unknown at the time. Grotefend similarly equated the sequence with ''kh-sh-h-e-r-sh-e'' for ''Xerxes'', which again was right, but the actual Old Persian transcription was ''kha-sha-ya-a-ra-sha-a''. Finally, he matched the sequence of the father who was not a king with Hystaspes Vishtaspa ( ae, 𐬬𐬌𐬱𐬙𐬁𐬯𐬞𐬀 ; peo, 𐎻𐏁𐎫𐎠𐎿𐎱, ), hellenized as Hystáspes (, ), may refer to:

* Vishtaspa ( fl. between 10th and 6th century BCE, if historical), the first patron of Zoroaster

* Hystaspes (fat ...

, but again with the supposed Persian reading of ''g-o-sh-t-a-s-p'', rather than the actual Old Persian ''vi-i-sha-ta-a-sa-pa''.

By this method, Grotefend had correctly identified each king in the inscriptions, but his identification of the phonetical value of individual letters was still quite defective, for want of a better understanding of the Old Persian language itself. Grotefend only identified correctly the phonetical value of eight letters among the thirty signs he had collated.

Guessing whole sentences

Grotefend made further guesses about the remaining words in the inscriptions, and endeavoured to rebuild probable sentences. Again relying on deductions only, and without knowing the actual script or language, Grotefend guessed a complete translation of the Xerxes inscription (Niebuhr inscription 2): "Xerxes the strong King, King of Kings, son of Darius the King, ruler of the world" (''"Xerxes Rex fortis, Rex regum, Darii Regis Filius, orbis rector"''). In effect, he achieved a fairly close translation, as the modern translation is: "Xerxes the Great King, King of Kings, son of Darius the King, anAchaemenian

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire (; peo, 𐎧𐏁𐏂, , ), also called the First Persian Empire, was an ancient Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great in 550 BC. Based in Western Asia, it was contemporarily the largest em ...

".

Grotefend's contribution to Old Persian is unique in that he did not have comparisons between Old Persian and known languages, as opposed to the decipherment of the Egyptian hieroglyphics and the Rosetta Stone

The Rosetta Stone is a stele composed of granodiorite inscribed with three versions of a decree issued in Memphis, Egypt, in 196 BC during the Ptolemaic dynasty on behalf of King Ptolemy V Epiphanes. The top and middle texts are in Anci ...

. All his decipherments were done by comparing the texts with known history. However groundbreaking, this inductive method failed to convince academics, and the official recognition of his work was denied for nearly a generation. Grotefend published his deductions in 1802, but they were dismissed by the academic community.

Vindication

It was only in 1823 that Grotefend's discovery was confirmed, when the French archaeologist Champollion, who had just deciphered Egyptian hieroglyphs, was able to read the Egyptian dedication of a quadrilingual hieroglyph-cuneiform inscription on an alabaster vase in the Cabinet des Médailles, the "

It was only in 1823 that Grotefend's discovery was confirmed, when the French archaeologist Champollion, who had just deciphered Egyptian hieroglyphs, was able to read the Egyptian dedication of a quadrilingual hieroglyph-cuneiform inscription on an alabaster vase in the Cabinet des Médailles, the "Caylus vase

The Caylus vase is an Egyptian alabaster jar dedicated in the name of the Achaemenid king Xerxes I (c.518–465 BCE) in Egyptian hieroglyph and Old Persian cuneiform. Beyond its historical value as a dynastic artifact of Achaemenid Egypt, its quad ...

". The Egyptian inscription on the vase was in the name of King Xerxes I, and Champollion, together with the orientalist Antoine-Jean Saint-Martin, was able to confirm that the corresponding words in the cuneiform script were indeed the words which Grotefend had identified as meaning "king" and "Xerxes" through guesswork. The findings were published by Saint-Martin in ''Extrait d'un mémoire relatif aux antiques inscriptions de Persépolis lu à l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles Lettres'', thereby vindicating the pioneering work of Grotefend.

More advances were made on Grotefend's work and by 1847, most of the symbols were correctly identified. A basis had now been laid for the interpretation of the Persian inscriptions. However, lacking knowledge of old Persian, Grotefend misconstrued several important characters. Significant work remained to be done to complete the decipherment. Building on Grotefend's insights, this task was performed by Eugène Burnouf

Eugène Burnouf (; April 8, 1801May 28, 1852) was a French scholar, an Indologist and orientalist. His notable works include a study of Sanskrit literature, translation of the Hindu text ''Bhagavata Purana'' and Buddhist text ''Lotus Sutra''. He ...

, Christian Lassen

Christian Lassen (22 October 1800 – 8 May 1876) was a Norwegian-born, German orientalist and Indologist. He was a professor of Old Indian language and literature at the University of Bonn.

Biography

He was born at Bergen, Norway where he att ...

and Sir Henry Rawlinson.

The decipherment of the Old Persian Cuneiform script was at the beginning of the decipherment of all the other cuneiform scripts, as various multi-lingual inscriptions between the various cuneiform scripts were obtained from archaeological discoveries. The decipherment of Old Persian was the starting point for the decipherment of Elamite, Babylonian and Akkadian Akkadian or Accadian may refer to:

* Akkadians, inhabitants of the Akkadian Empire

* Akkadian language, an extinct Eastern Semitic language

* Akkadian literature, literature in this language

* Akkadian cuneiform

Cuneiform is a logo-syllabic ...

(predecessor of Babylonian), especially through the multi-lingual Behistun Inscription, and ultimately Sumerian through Akkadian-Sumerian bilingual tablets.

Signs

Most scholars consider the writing system to be an independent invention because it has no obvious connections with other writing systems at the time, such as Elamite, Akkadian,Hurrian

The Hurrians (; cuneiform: ; transliteration: ''Ḫu-ur-ri''; also called Hari, Khurrites, Hourri, Churri, Hurri or Hurriter) were a people of the Bronze Age Near East. They spoke a Hurrian language and lived in Anatolia, Syria and Norther ...

, and Hittite cuneiforms. While Old Persian's basic strokes are similar to those found in cuneiform scripts, Old Persian texts were engraved on hard materials, so the engravers had to make cuts that imitated the forms easily made on clay tablets. The signs are composed of horizontal, vertical, and angled wedges. There are four basic components and new signs are created by adding wedges to these basic components.Windfuhr, G. L.: "Notes on the old Persian signs", page 2. Indo-Iranian Journal, 1970. These four basic components are two parallel wedges without angle, three parallel wedges without angle, one wedge without angle and an angled wedge, and two angled wedges. The script is written from left to right.

The script encodes three vowels, ''a'', ''i'', ''u'', and twenty-two consonants, ''k'', ''x'', ''g'', ''c'', ''ç'', ''j'', ''t'', ''θ'', ''d'', ''p'', ''f'', ''b'', ''n'', ''m'', ''y'', ''v'', ''r'', ''l'', ''s'', ''z'', ''š'', and ''h''. Old Persian contains two sets of consonants: those whose shape depends on the following vowel and those whose shape is independent of the following vowel. The consonant symbols that depend on the following vowel act like the consonants in

The script encodes three vowels, ''a'', ''i'', ''u'', and twenty-two consonants, ''k'', ''x'', ''g'', ''c'', ''ç'', ''j'', ''t'', ''θ'', ''d'', ''p'', ''f'', ''b'', ''n'', ''m'', ''y'', ''v'', ''r'', ''l'', ''s'', ''z'', ''š'', and ''h''. Old Persian contains two sets of consonants: those whose shape depends on the following vowel and those whose shape is independent of the following vowel. The consonant symbols that depend on the following vowel act like the consonants in Devanagari

Devanagari ( ; , , Sanskrit pronunciation: ), also called Nagari (),Kathleen Kuiper (2010), The Culture of India, New York: The Rosen Publishing Group, , page 83 is a left-to-right abugida (a type of segmental writing system), based on the ...

. Vowel diacritics are added to these consonant symbols to change the inherent vowel or add length to the inherent vowel. However, the vowel symbols are usually still included so iwould be written as i even though ialready implies the vowel. For the consonants whose shape does not depend on the following vowels, the vowel signs must be used after the consonant symbol.

Compared to the Avestan alphabet

The Avestan alphabet (Middle Persian: transliteration: ''dyn' dpywryh'', transcription: ''dēn dēbīrē'', fa, دین دبیره, translit=din dabire) is a writing system developed during Iran's Sasanian era (226–651 CE) to render ...

Old Persian notably lacks voiced fricatives, but includes the sign ''ç'' (of uncertain pronunciation) and a sign for the non-native ''l''. Notably, in common with the Brahmic scripts

The Brahmic scripts, also known as Indic scripts, are a family of abugida writing systems. They are used throughout the Indian subcontinent, Southeast Asia and parts of East Asia. They are descended from the Brahmi script of ancient In ...

, there appears to be no distinction between a consonant followed by an ''a'' and a consonant followed by nothing.

*logograms:

**'' Ahuramazdā'': , , (genitive)

**''xšāyaθiya'' "king":

**''dahyāuš-'' "country": ,

**''baga-'' "god":

**''būmiš-'' "earth":

*word divider

In punctuation, a word divider is a glyph that separates written words. In languages which use the Latin, Cyrillic, and Arabic alphabets, as well as other scripts of Europe and West Asia, the word divider is a blank space, or ''whitespace''. ...

:

*numerals:Unattested numbers are not listed. The list of attested numbers is based on

**1 , 2 , 5 , 7 , 8 , 9

**10 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 22 , 23 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 40 , 60 ,

**120

Alphabetic properties

Although based on a logo-syllabic prototype, all vowels but short /a/ are written and so the system is essentially an

Although based on a logo-syllabic prototype, all vowels but short /a/ are written and so the system is essentially an alphabet

An alphabet is a standardized set of basic written graphemes (called letters) that represent the phonemes of certain spoken languages. Not all writing systems represent language in this way; in a syllabary, each character represents a syllab ...

. There are three vowels, long and short. Initially, no distinction is made for length: ''a'' or ''ā,'' ''i'' or ''ī,'' ''u'' or ''ū.'' However, as in the Brahmic scripts, short ''a'' is not written after a consonant: ''h'' or ''ha,'' ''hā,'' ''hi'' or ''hī,'' ''hu'' or ''hū.'' (Old Persian is not considered an abugida

An abugida (, from Ge'ez: ), sometimes known as alphasyllabary, neosyllabary or pseudo-alphabet, is a segmental writing system in which consonant-vowel sequences are written as units; each unit is based on a consonant letter, and vowel no ...

because vowels are represented as full letters.)

Thirteen out of twenty-two consonants, such as ''h(a),'' are invariant, regardless of the following vowel (that is, they are alphabetic), while only six have a distinct form for each consonant-vowel combination (that is, they are syllabic), and among these, only ''d'' and ''m'' occur in three forms for all three vowels: ''d'' or ''da,'' ''dā,'' ''di'' or ''dī,'' ''du'' or ''dū.'' (''k, g'' do not occur before ''i,'' and ''j, v'' do not occur before ''u,'' so these consonants only have two forms each.)

Sometimes medial long vowels are written with a ''y'' or ''v,'' as in Semitic: ''dī,'' ''dū.'' Diphthongs are written by mismatching consonant and vowel: ''dai'', or sometimes, in cases where the consonant does not differentiate between vowels, by writing the consonant and both vowel components: ''cišpaiš'' (gen. of name Cišpi- ' Teispes').

In addition, three consonants, ''t'', ''n'', and ''r'', are partially syllabic, having the same form before ''a'' and ''i'', and a distinct form only before ''u'': ''n'' or ''na,'' ''nā,'' ''ni'' or ''nī,'' ''nu'' or ''nū.''

The effect is not unlike the English sound, which is typically written ''g'' before ''i'' or ''e'', but ''j'' before other vowels (''gem'', ''jam''), or the Castilian Spanish

In English, Castilian Spanish can mean the variety of Peninsular Spanish spoken in northern and central Spain, the standard form of Spanish, or Spanish from Spain in general. In Spanish, the term (Castilian) can either refer to the Spanish lang ...

sound, which is written ''c'' before ''i'' or ''e'' and ''z'' before other vowels (''cinco, zapato''): it is more accurate to say that some of the Old Persian consonants are written by different letters depending on the following vowel, rather than classifying the script as syllabic. This situation had its origin in Assyrian cuneiform, where several syllabic distinctions had been lost and were often clarified with explicit vowels. However, in the case of Assyrian, the vowel was not always used, and was never used where not needed, so the system remained (logo-)syllabic.

For a while it was speculated that the alphabet could have had its origin in such a system, with a leveling of consonant signs a millennium earlier producing something like the Ugaritic alphabet, but today it is generally accepted that the Semitic alphabet arose from Egyptian hieroglyphs

Egyptian hieroglyphs (, ) were the formal writing system used in Ancient Egypt, used for writing the Egyptian language. Hieroglyphs combined logographic, syllabic and alphabetic elements, with some 1,000 distinct characters.There were about 1, ...

, where vowel notation was not important. (See Proto-Sinaitic script

Proto-Sinaitic (also referred to as Sinaitic, Proto-Canaanite when found in Canaan, the North Semitic alphabet, or Early Alphabetic) is considered the earliest trace of alphabetic writing and the common ancestor of both the Ancient South Arabian ...

.)

Unicode

Old Persian cuneiform was added to theUnicode

Unicode, formally The Unicode Standard,The formal version reference is is an information technology standard for the consistent encoding, representation, and handling of text expressed in most of the world's writing systems. The standard, ...

Standard in March 2005 with the release of version 4.1.

The Unicode block for Old Persian cuneiform is U+103A0–U+103DF and is in the Supplementary Multilingual Plane:

Notes and references

* * *Sources

* * * *Further reading

* * * * * * *External links

Fonts

Download "Kakoulookiam", Old Persian Cuneiform Font (Unicode)

Download "Khosrau", Old Persian Cuneiform Font (Unicode)

Download "Behistun", Old Persian Cuneiform Font (Unicode)

(install one of the above fonts and see this page)

(learn how to configure your browser)

Texts

Achaemenid Royal Inscriptions

(Livius.org) *

Descriptions

{{list of writing systems Persian orthography Old Persian language Obsolete writing systems Syllabary writing systems Alphabets Cuneiform Persian scripts