Occupation Of Smyrna on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The city of

At the end of World War I (1914–1918), attention of the Allied Powers (Entente Powers) focused on the partition of the territory of the

At the end of World War I (1914–1918), attention of the Allied Powers (Entente Powers) focused on the partition of the territory of the

On 14 May 1919, the Greek mission in Smyrna read a statement announcing that Greek troops would be arriving the next day in the city. Smith reports that this news was "received with great emotion" by the Greek population of the city while thousands of Turkish residents gathered in the hill that night lighting fires and beating drums in protest. The same night, thousands of Turkish prisoners were released from a prison with the complicity of the Ottoman and Italian commanders in charge of the prison.

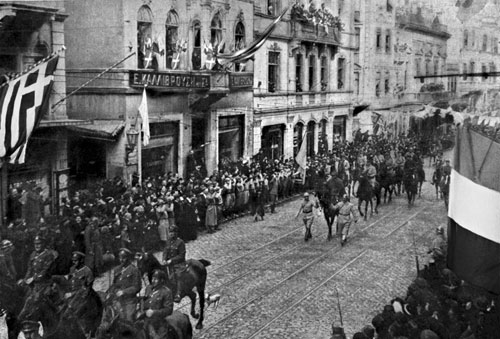

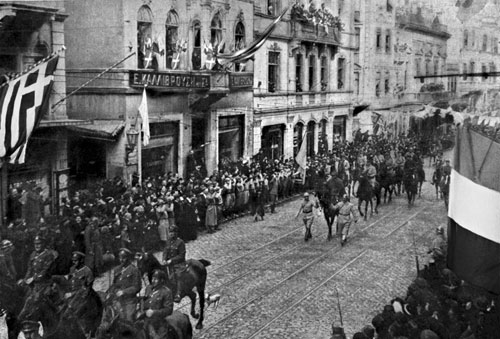

Greek occupation of Smyrna started on 15 May 1919 where a large crowd gathered waving the Greek kingdom flags on the docks where the Greek troops were expected to arrive. The Metropolitan of Smyrna, Chrysostomos, blessed the first troops as they arrived. An inexperienced colonel was in charge of the operation and neither the appointed high commissioner nor high-ranking military individuals were there for the landing, resulting in miscommunication and a breakdown of discipline. Most significantly, this resulted in the 1/38 Evzone Regiment landing north of where they were to take up their post. They had to march south, passing a large part of the Greek celebratory crowds, the Ottoman governor's konak and the barracks of Ottoman troops. Someone fired a shot (Smith indicates that no one knows who) and chaos resulted, with the Greek troops firing multiple shots into the konak and the barracks. The Ottoman troops surrendered and the Greek regiment began marching them up the coast to a ship to serve as a temporary prison. A British subject at the scene claimed he witnessed the shooting deaths of thirty unarmed prisoners during this march, by both Greeks in the crowd and Greek troops. British officers in the harbor reported seeing Greek troops bayoneting multiple Turkish prisoners during the march and then saw them thrown into the sea. In the chaos, looting of Turkish houses began, and by the end of the day three to four hundred Turks had been killed. One hundred Greeks were also killed, including two soldiers. Violence continued the next day and for the next months as Greek troops took over towns and villages in the region and atrocities were committed by both ethnic groups, notably the Battle of Aydın on 27 June 1919.

On 14 May 1919, the Greek mission in Smyrna read a statement announcing that Greek troops would be arriving the next day in the city. Smith reports that this news was "received with great emotion" by the Greek population of the city while thousands of Turkish residents gathered in the hill that night lighting fires and beating drums in protest. The same night, thousands of Turkish prisoners were released from a prison with the complicity of the Ottoman and Italian commanders in charge of the prison.

Greek occupation of Smyrna started on 15 May 1919 where a large crowd gathered waving the Greek kingdom flags on the docks where the Greek troops were expected to arrive. The Metropolitan of Smyrna, Chrysostomos, blessed the first troops as they arrived. An inexperienced colonel was in charge of the operation and neither the appointed high commissioner nor high-ranking military individuals were there for the landing, resulting in miscommunication and a breakdown of discipline. Most significantly, this resulted in the 1/38 Evzone Regiment landing north of where they were to take up their post. They had to march south, passing a large part of the Greek celebratory crowds, the Ottoman governor's konak and the barracks of Ottoman troops. Someone fired a shot (Smith indicates that no one knows who) and chaos resulted, with the Greek troops firing multiple shots into the konak and the barracks. The Ottoman troops surrendered and the Greek regiment began marching them up the coast to a ship to serve as a temporary prison. A British subject at the scene claimed he witnessed the shooting deaths of thirty unarmed prisoners during this march, by both Greeks in the crowd and Greek troops. British officers in the harbor reported seeing Greek troops bayoneting multiple Turkish prisoners during the march and then saw them thrown into the sea. In the chaos, looting of Turkish houses began, and by the end of the day three to four hundred Turks had been killed. One hundred Greeks were also killed, including two soldiers. Violence continued the next day and for the next months as Greek troops took over towns and villages in the region and atrocities were committed by both ethnic groups, notably the Battle of Aydın on 27 June 1919.

The landing and reports of the violence had a large impact on many parties. The landing helped bring together the various groups of Turkish resistance into an organized movement (further assisted by the landing of

The landing and reports of the violence had a large impact on many parties. The landing helped bring together the various groups of Turkish resistance into an organized movement (further assisted by the landing of

In 1920, the Smyrna zone became a key base for the Greek summer offensive in the Greco-Turkish War. Early in July 1920, the allies approved operations by the Greeks to take over Eastern Thrace and territory around Smyrna as part of ongoing hostilities with the Turkish Nationalist movement. On 22 July 1920, Greek military divisions crossed the Milne line around the Smyrna zone and began military operations in the rest of Anatolia.

In 1920, the Smyrna zone became a key base for the Greek summer offensive in the Greco-Turkish War. Early in July 1920, the allies approved operations by the Greeks to take over Eastern Thrace and territory around Smyrna as part of ongoing hostilities with the Turkish Nationalist movement. On 22 July 1920, Greek military divisions crossed the Milne line around the Smyrna zone and began military operations in the rest of Anatolia.

International negotiations between the allies and the Ottoman administration largely ignored the increasing conflict. In early 1920, Lloyd George was able to convince the new French Prime Minister,

International negotiations between the allies and the Ottoman administration largely ignored the increasing conflict. In early 1920, Lloyd George was able to convince the new French Prime Minister,

Greek troops evacuated Smyrna on 9 September 1922 and a small allied force of British entered the city to prevent looting and violence. The next day, Mustafa Kemal, leading a number of troops, entered the city and was greeted by enthusiastic Turkish crowds. Atrocities by Turkish troops and irregulars against the Greek and Armenian population occurred immediately after the takeover. Most notably, Chrysostomos, the Orthodox Bishop, was lynched by a mob of Turkish citizens. A few days afterward, a fire destroyed the Greek and Armenian quarters of the city, while the Turkish and Jewish quarters remained undamaged. On the Turkish side the events are known as the Liberation of İzmir, while on the Greek side as Catastrophe of Smyrna.

The evacuation of Smyrna by Greek troops ended most of the large scale fighting in the Greco-Turkish war which was formally ended with an Armistice and a final treaty on 24 July 1923 with the Treaty of Lausanne. Much of the Greek population was included in the 1923

Greek troops evacuated Smyrna on 9 September 1922 and a small allied force of British entered the city to prevent looting and violence. The next day, Mustafa Kemal, leading a number of troops, entered the city and was greeted by enthusiastic Turkish crowds. Atrocities by Turkish troops and irregulars against the Greek and Armenian population occurred immediately after the takeover. Most notably, Chrysostomos, the Orthodox Bishop, was lynched by a mob of Turkish citizens. A few days afterward, a fire destroyed the Greek and Armenian quarters of the city, while the Turkish and Jewish quarters remained undamaged. On the Turkish side the events are known as the Liberation of İzmir, while on the Greek side as Catastrophe of Smyrna.

The evacuation of Smyrna by Greek troops ended most of the large scale fighting in the Greco-Turkish war which was formally ended with an Armistice and a final treaty on 24 July 1923 with the Treaty of Lausanne. Much of the Greek population was included in the 1923

Documents

of the Inter-Allied Commission of Inquiry into the Greek Occupation of Smyrna and Adjoining Territories.

"Remembering Smyrna/Izmir: Shared History, Shared Trauma" by Leyla Neyzi

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Occupation of Smyrna Former countries of the interwar period *

Smyrna

Smyrna ( ; grc, Σμύρνη, Smýrnē, or , ) was a Greek city located at a strategic point on the Aegean coast of Anatolia. Due to its advantageous port conditions, its ease of defence, and its good inland connections, Smyrna rose to promi ...

(modern-day İzmir

İzmir ( , ; ), also spelled Izmir, is a metropolitan city in the western extremity of Anatolia, capital of the province of the same name. It is the third most populous city in Turkey, after Istanbul and Ankara and the second largest urban agglo ...

) and surrounding areas were under Greek military occupation

Military occupation, also known as belligerent occupation or simply occupation, is the effective military control by a ruling power over a territory that is outside of that power's sovereign territory.Eyāl Benveniśtî. The international law ...

from 15 May 1919 until 9 September 1922. The Allied Powers authorized the occupation and creation of the Zone of Smyrna ( el, Ζώνη Σμύρνης, Zóni Smýrnis) during negotiations regarding the partition of the Ottoman Empire

The partition of the Ottoman Empire (30 October 19181 November 1922) was a geopolitical event that occurred after World War I and the occupation of Constantinople by British, French and Italian troops in November 1918. The partitioning was ...

to protect the ethnic Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

population living in and around the city. The Greek landing on 15 May 1919 was celebrated by the substantial local Greek population but quickly resulted in ethnic violence in the area. This violence decreased international support for the occupation and led to a rise in Turkish nationalism. The high commissioner of Smyrna, Aristeidis Stergiadis, firmly opposed discrimination against the Turkish population by the administration; however, ethnic tensions and discrimination remained. Stergiadis also began work on projects involving resettlement of Greek refugees, the foundations for a university, and some public health projects. Smyrna was a major base of operations for Greek troops in Anatolia during the Greco-Turkish War (1919–1922)

The Greco-Turkish War of 1919–1922, ota, گرب جابهاسی, Garb Cebhesi) in Turkey, and the Asia Minor Campaign ( el, Μικρασιατική Εκστρατεία, Mikrasiatikí Ekstrateía) or the Asia Minor Catastrophe ( el, Μικ ...

.

The Greek occupation of Smyrna ended on 9 September 1922 with the Turkish capture of Smyrna

The Turkish Capture of Smyrna, or the Liberation of İzmir ( tr, İzmir'in Kurtuluşu) marked the end of the 1919–1922 Greco-Turkish War, and the culmination of the Turkish War of Independence. On 9 September 1922, following the headlong ret ...

by troops commanded by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk

Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, or Mustafa Kemal Pasha until 1921, and Ghazi Mustafa Kemal from 1921 Surname Law (Turkey), until 1934 ( 1881 – 10 November 1938) was a Turkish Mareşal (Turkey), field marshal, Turkish National Movement, re ...

. After the Turkish advance on Smyrna, a mob murdered the Orthodox bishop Chrysostomos and a few days later the Great Fire of Smyrna

The burning of Smyrna ( el, Καταστροφή της Σμύρνης, "Smyrna Catastrophe"; tr, 1922 İzmir Yangını, "1922 Izmir Fire"; hy, Զմիւռնիոյ Մեծ Հրդեհ, ''Zmyuṙno Mets Hrdeh'') destroyed much of the port city of ...

burnt large parts of the city (including most of the Greek and Armenian areas). Estimated Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

and Armenian

Armenian may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to Armenia, a country in the South Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Armenians, the national people of Armenia, or people of Armenian descent

** Armenian Diaspora, Armenian communities across the ...

deaths range from 10,000 to 100,000.Naimark, Norman M. ''Fires of Hatred: Ethnic Cleansing in Twentieth-Century Europe''. Cambridge: MA: Harvard University Press, 2002, p. 52. With the end of the occupation of Smyrna, major combat in Anatolia between Greek and Turkish forces largely ended, and on 24 July 1923, the parties signed the Treaty of Lausanne

The Treaty of Lausanne (french: Traité de Lausanne) was a peace treaty negotiated during the Lausanne Conference of 1922–23 and signed in the Palais de Rumine, Lausanne, Switzerland, on 24 July 1923. The treaty officially settled the conflic ...

ending the war.

Background

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

. As part of the Treaty of London (1915)

The Treaty of London ( it, Trattato di Londra) or the Pact of London () was a secret agreement concluded on 26 April 1915 by the United Kingdom, France, and Russia on the one part, and Italy on the other, in order to entice the latter to enter ...

, by which Italy left the Triple Alliance (with Germany and Austria-Hungary) and joined France, Great Britain and Russia in the Triple Entente

The Triple Entente (from French '' entente'' meaning "friendship, understanding, agreement") describes the informal understanding between the Russian Empire, the French Third Republic, and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland as well a ...

, Italy was promised the Dodecanese

The Dodecanese (, ; el, Δωδεκάνησα, ''Dodekánisa'' , ) are a group of 15 larger plus 150 smaller Greek islands in the southeastern Aegean Sea and Eastern Mediterranean, off the coast of Turkey's Anatolia, of which 26 are inhabited. ...

and, if the partition of the Ottoman Empire were to occur, land in Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

including Antalya

Antalya () is the List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, fifth-most populous city in Turkey as well as the capital of Antalya Province. Located on Anatolia's southwest coast bordered by the Taurus Mountains, Antalya is the largest Turkish cit ...

and surrounding provinces presumably including Smyrna. But in later 1915, as an inducement to enter the war, British Foreign Secretary Edward Grey in private discussion with Eleftherios Venizelos

Eleftherios Kyriakou Venizelos ( el, Ελευθέριος Κυριάκου Βενιζέλος, translit=Elefthérios Kyriákou Venizélos, ; – 18 March 1936) was a Greek statesman and a prominent leader of the Greek national liberation movem ...

, the Greek Prime Minister at the time, promised large parts of the Anatolian coast to Greece, including Smyrna. Venizelos resigned from his position shortly after this communication, but when he had formally returned to power in June 1917, Greece entered the war on the side of the Entente.

On 30 October 1918, the Armistice of Mudros

Concluded on 30 October 1918 and taking effect at noon the next day, the Armistice of Mudros ( tr, Mondros Mütarekesi) ended hostilities in the Middle Eastern theatre between the Ottoman Empire and the Allies of World War I. It was signed by th ...

was signed between the Entente powers and the Ottoman Empire ending the Ottoman front of World War I. Great Britain, Greece, Italy, France, and the United States began discussing what the treaty provisions regarding the partition of Ottoman territory would be, negotiations which resulted in the Treaty of Sèvres

The Treaty of Sèvres (french: Traité de Sèvres) was a 1920 treaty signed between the Allies of World War I and the Ottoman Empire. The treaty ceded large parts of Ottoman territory to France, the United Kingdom, Greece and Italy, as well ...

. These negotiations began in February 1919 and each country had distinct negotiating preferences about Smyrna. The French, who had large investments in the region, took a position for territorial integrity of a Turkish state that would include the zone of Smyrna. The British were at a loggerhead over the issue with the War Office

The War Office was a department of the British Government responsible for the administration of the British Army between 1857 and 1964, when its functions were transferred to the new Ministry of Defence (MoD). This article contains text from ...

and India Office

The India Office was a British government department established in London in 1858 to oversee the administration, through a Viceroy and other officials, of the Provinces of India. These territories comprised most of the modern-day nations of I ...

promoting the territorial integrity idea and Prime Minister David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for leading the United Kingdom during t ...

and the Foreign Office

Foreign may refer to:

Government

* Foreign policy, how a country interacts with other countries

* Ministry of Foreign Affairs, in many countries

** Foreign Office, a department of the UK government

** Foreign office and foreign minister

* Unit ...

, headed by Lord Curzon

George Nathaniel Curzon, 1st Marquess Curzon of Kedleston, (11 January 1859 – 20 March 1925), styled Lord Curzon of Kedleston between 1898 and 1911 and then Earl Curzon of Kedleston between 1911 and 1921, was a British Conservative statesman ...

, opposed this suggestion and wanting Smyrna to be under separate administration. The Italian position was that Smyrna was rightfully their possession and so the diplomats would refuse to make any comments when Greek control over the area was discussed. The Greek government, pursuing Venizelos' support for the ''Megali Idea

The Megali Idea ( el, Μεγάλη Ιδέα, Megáli Idéa, Great Idea) is a nationalist and irredentist concept that expresses the goal of reviving the Byzantine Empire, by establishing a Greek state, which would include the large Greek popul ...

'' (to bring areas with a majority Greek population or with historical or religious ties to Greece under control of the Greek state) and supported by Lloyd George, began a large propaganda effort to promote their claim to Smyrna including establishing a mission under the foreign minister in the city. Moreover, the Greek claim over the Smyrna area (which appeared to have a clear Greek majority, although exact percentages varied depending on the source) were supported by Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

's Fourteen Points

U.S. President Woodrow Wilson

The Fourteen Points was a statement of principles for peace that was to be used for peace negotiations in order to end World War I. The principles were outlined in a January 8, 1918 speech on war aims and peace terms ...

which emphasized the right to autonomous development for minorities in Anatolia. In negotiations, despite French and Italian objections, by the middle of February 1919 Lloyd George shifted the discussion to how Greek administration would work and not whether Greek administration would happen. To further this aim, he brought in a set of experts, including Arnold J. Toynbee

Arnold Joseph Toynbee (; 14 April 1889 – 22 October 1975) was an English historian, a philosopher of history, an author of numerous books and a research professor of international history at the London School of Economics and King's Colleg ...

, to discuss how the zone of Smyrna would operate and what its impacts would be on the population. Following this discussion, in late February 1919, Venezilos appointed Aristeidis Stergiadis, a close political ally, the High Commissioner of Smyrna (appointed over political riser Themistoklis Sofoulis

Themistoklis Sofoulis or Sophoulis (; 24 November 1860 – 24 June 1949) was a prominent centrist and liberal Greek politician from Samos Island, who served three times as Prime Minister of Greece, with the Liberal Party, which he led for many y ...

).

In April 1919, the Italians landed and took over Antalya and began showing signs of moving troops towards Smyrna. During the negotiations at about the same time, the Italian delegation walked out when it became clear that Fiume (Rijeka) would not be given to them in the peace outcome. Lloyd George saw an opportunity to break the impasse over Smyrna with the absence of the Italian delegation and, according to Jensen, he "concocted a report that an armed uprising of Turkish guerrillas in the Smyrna area was seriously endangering the Greek and other Christian minorities." Both to protect local Christians and also to limit increasing Italian action in Anatolia, French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau

Georges Benjamin Clemenceau (, also , ; 28 September 1841 – 24 November 1929) was a French statesman who served as Prime Minister of France from 1906 to 1909 and again from 1917 until 1920. A key figure of the Independent Radicals, he was a ...

and U.S. President Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

supported a Greek military occupation of Smyrna. Although Smyrna would be occupied by Greek troops, authorized by the Allies, the Allies did not agree that Greece would take sovereignty over the territory until further negotiations settled this issue. The Italian delegation acquiesced to this outcome and the Greek occupation was authorized.

Greek landing at Smyrna

On 14 May 1919, the Greek mission in Smyrna read a statement announcing that Greek troops would be arriving the next day in the city. Smith reports that this news was "received with great emotion" by the Greek population of the city while thousands of Turkish residents gathered in the hill that night lighting fires and beating drums in protest. The same night, thousands of Turkish prisoners were released from a prison with the complicity of the Ottoman and Italian commanders in charge of the prison.

Greek occupation of Smyrna started on 15 May 1919 where a large crowd gathered waving the Greek kingdom flags on the docks where the Greek troops were expected to arrive. The Metropolitan of Smyrna, Chrysostomos, blessed the first troops as they arrived. An inexperienced colonel was in charge of the operation and neither the appointed high commissioner nor high-ranking military individuals were there for the landing, resulting in miscommunication and a breakdown of discipline. Most significantly, this resulted in the 1/38 Evzone Regiment landing north of where they were to take up their post. They had to march south, passing a large part of the Greek celebratory crowds, the Ottoman governor's konak and the barracks of Ottoman troops. Someone fired a shot (Smith indicates that no one knows who) and chaos resulted, with the Greek troops firing multiple shots into the konak and the barracks. The Ottoman troops surrendered and the Greek regiment began marching them up the coast to a ship to serve as a temporary prison. A British subject at the scene claimed he witnessed the shooting deaths of thirty unarmed prisoners during this march, by both Greeks in the crowd and Greek troops. British officers in the harbor reported seeing Greek troops bayoneting multiple Turkish prisoners during the march and then saw them thrown into the sea. In the chaos, looting of Turkish houses began, and by the end of the day three to four hundred Turks had been killed. One hundred Greeks were also killed, including two soldiers. Violence continued the next day and for the next months as Greek troops took over towns and villages in the region and atrocities were committed by both ethnic groups, notably the Battle of Aydın on 27 June 1919.

On 14 May 1919, the Greek mission in Smyrna read a statement announcing that Greek troops would be arriving the next day in the city. Smith reports that this news was "received with great emotion" by the Greek population of the city while thousands of Turkish residents gathered in the hill that night lighting fires and beating drums in protest. The same night, thousands of Turkish prisoners were released from a prison with the complicity of the Ottoman and Italian commanders in charge of the prison.

Greek occupation of Smyrna started on 15 May 1919 where a large crowd gathered waving the Greek kingdom flags on the docks where the Greek troops were expected to arrive. The Metropolitan of Smyrna, Chrysostomos, blessed the first troops as they arrived. An inexperienced colonel was in charge of the operation and neither the appointed high commissioner nor high-ranking military individuals were there for the landing, resulting in miscommunication and a breakdown of discipline. Most significantly, this resulted in the 1/38 Evzone Regiment landing north of where they were to take up their post. They had to march south, passing a large part of the Greek celebratory crowds, the Ottoman governor's konak and the barracks of Ottoman troops. Someone fired a shot (Smith indicates that no one knows who) and chaos resulted, with the Greek troops firing multiple shots into the konak and the barracks. The Ottoman troops surrendered and the Greek regiment began marching them up the coast to a ship to serve as a temporary prison. A British subject at the scene claimed he witnessed the shooting deaths of thirty unarmed prisoners during this march, by both Greeks in the crowd and Greek troops. British officers in the harbor reported seeing Greek troops bayoneting multiple Turkish prisoners during the march and then saw them thrown into the sea. In the chaos, looting of Turkish houses began, and by the end of the day three to four hundred Turks had been killed. One hundred Greeks were also killed, including two soldiers. Violence continued the next day and for the next months as Greek troops took over towns and villages in the region and atrocities were committed by both ethnic groups, notably the Battle of Aydın on 27 June 1919.

Reactions to the landing

The landing and reports of the violence had a large impact on many parties. The landing helped bring together the various groups of Turkish resistance into an organized movement (further assisted by the landing of

The landing and reports of the violence had a large impact on many parties. The landing helped bring together the various groups of Turkish resistance into an organized movement (further assisted by the landing of Mustafa Kemal

Mustafa ( ar, مصطفى

, Muṣṭafā) is one of the names of Prophet Muhammad, and the name means "chosen, selected, appointed, preferred", used as an Arabic given name and surname. Mustafa is a common name in the Muslim world.

Given name ...

in Samsun

Samsun, historically known as Sampsounta ( gr, Σαμψούντα) and Amisos (Ancient Greek: Αμισός), is a List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, city on the north coast of Turkey and is a major Black Sea port. In 2021, Samsun reco ...

on 19 May 1919). Several demonstrations were held by Turkish people in Constantinople condemning the occupation of Smyrna. Between 100,000 and 150,000 people gathered in a meeting at Sultanahmet square organized by the Karakol society

The Karakol society ( tr, Karakol Cemiyeti), was a Turkish clandestine intelligence organization that fought on the side of the Turkish National Movement during the Turkish War of Independence. Formed in November 1918, it refused to merge itself w ...

and Türk Ocağı. In Great Britain and France, the reports of violence increased opposition in the governments to a permanent Greek control over the area.

As a response to the claims of violence, the French Prime Minister Clemenceau suggested an Interallied Commission of Inquiry to Smyrna: the commission was made up of Admiral Mark Lambert Bristol

Mark Lambert Bristol (April 17, 1868 – May 13, 1939) was a rear admiral in the United States Navy.

Biography

He was born on April 17, 1868, in Glassboro, New Jersey. Bristol graduated from the United States Naval Academy in 1887. During the Spa ...

for the United States, General Bunoust for France, General Hare for England, General Dall'olio for Italy and, as a non-voting observer, Colonel Mazarakis for Greece. It began work in August 1919 and interviewed 175 witnesses and visited multiple sites of alleged atrocities. The decision reached was that when a Greek witness and Turkish witness disagreed, a European witness would be used to provide the conclusions for the report. This system was dismissed by Venizelos because he claimed that the Europeans living in Smyrna benefited from privileges given to them under the Ottoman rule and were thus opposed to Greek rule. The report was released to negotiators in October and generally found Greeks responsible for the bloodshed related to the landing and the violence throughout the Smyrna zone after the landing. In addition, the conclusions questioned the fundamental justification for the Greek occupation and suggested Greek troops be replaced by an allied force. Eyre Crowe

Sir Eyre Alexander Barby Wichart Crowe (30 July 1864 – 28 April 1925) was a British diplomat, an expert on Germany in the Foreign and Commonwealth Office. He is best known for his vehement warning, in 1907, that Germany's expansionism was mo ...

, a main British diplomat, dismissed the larger conclusion by saying the commission had overstepped its mandate. In the negotiations after the report, Clemenceau reminded Venizelos that the occupation of Smyrna was not permanent and merely a political solution. Venizelos responded angrily and the negotiators moved on.

At about the same time, British Field Marshal George Milne

Field Marshal George Francis Milne, 1st Baron Milne, (5 November 1866 – 23 March 1948) was a senior British Army officer who served as Chief of the Imperial General Staff (CIGS) from 1926 to 1933. He served in the Second Boer War and during ...

was tasked by the allies with devising a solution to Italian and Greek tension in the Menderes River Valley. Milne warned in his report that Turkish guerrilla action would continue as long as the Greeks continued to occupy Smyrna and questioned the justification for Greek occupation. Most importantly, his report developed a border that would separate the Smyrna zone from the rest of Anatolia. The council of Great Britain, France, U.S. and Italy approved the Milne line beyond which Greek troops were not to cross, except to pursue attackers but not more than 3 km beyond the line.

Administration of the Smyrna Zone (1919–1922)

High commissioner

Aristeidis Stergiadis was appointed the high commissioner of Smyrna in February and arrived in the city four days after the 15 May landing. Stergiadis immediately went to work in setting up an administration, easing ethnic violence, and making way for permanent annexation of Smyrna. Stergiadis immediately punished the Greek soldiers responsible for violence on 15–16 May with court martial and created a commission to decide on payment for victims (made up of representatives from Great Britain, France, Italy and other allies). Stergiadis took a strict stance against discrimination of the Turkish population and opposed church leaders and the local Greek population on a number of occasions. Historians disagree about whether this was a genuine stance against discrimination or whether it was an attempt to present a positive vision of the occupation to the allies. This stance against discrimination of the Turkish population often pitted Stergiadis against the local Greek population, the church and the army. He reportedly would carry a stick through the town with which he would beat Greeks that were being abusive of Turkish citizens. At one point, Stergiadis interrupted and ended a sermon by the bishop Chrysostomos that he believed to be incendiary. Troops would disobey his orders to not abuse the Turkish population often putting him in conflict with the military. On 14 July 1919, the acting foreign secretary sent a long critical telegraph to Venizelos suggesting that Stergiadis be removed and writing that "His sick neuroticism has reached a climax." Venizelos continued to support Stergiadis despite this opposition, while the latter oversaw a number of projects planning for a permanent Greek administration of Smyrna.

Structure of the administration

The Greek consulate building became the center of government. Since Ottoman sovereignty was not replaced with the occupation, their administrative structure continued to exist but Stergiadis simply replaced senior positions with Greeks (except for the post for Muslim Affairs) while Turkish functionaries remained in low positions. Urgent steps were required for the organization of a local administration as soon as the Greek army secured control of the region.Solomonidis, 1984, p. 132 A significant obstacle during the first period of the Greek administration was the absence of a clear definition of the Greek mandate. In this context the coexistence of interallied authorities whose functions often overlapped with that of the Greek authorities resulted in a series of misunderstandings and friction between the two sides. This situation resulted after a decision by the Supreme Allied Council that all movements of the Greek army had to be approved by Field MarshalGeorge Milne

Field Marshal George Francis Milne, 1st Baron Milne, (5 November 1866 – 23 March 1948) was a senior British Army officer who served as Chief of the Imperial General Staff (CIGS) from 1926 to 1933. He served in the Second Boer War and during ...

.

The administration of the Smyrna zone was organized in units largely based on the former Ottoman system. Apart from the kaza of Smyrna and the adjacent area of Ayasoluk which were under the direct control of the Smyrna High Commission, the remaining zone was divided into one province ( el, Νομαρχία ''Nomarchia''): that of Manisa, as well as the following counties ( el, Υποδιοικήσεις ''Ypodioikiseis''): Ödemiş

Ödemiş is a district of İzmir Province of Turkey, as well as the name of its central town (urban population 75,577 as of 2012), located 113 km southeast of the city of İzmir.

About 4 km north of Ödemiş town are the ruins of Hypa ...

, Tire

A tire (American English) or tyre (British English) is a ring-shaped component that surrounds a Rim (wheel), wheel's rim to transfer a vehicle's load from the axle through the wheel to the ground and to provide Traction (engineering), t ...

(Thira), Bayındır

Bayındır is a district of İzmir Province of Turkey and the central town of the district which is situated in the valley of the Küçük Menderes. The cited information may be out of date.

History

Its name in classical antiquity was Caystrus ...

(Vaindirion), Nympheon, Krini, Karaburna, Sivrihisar, Vryula, Palea Phocaea, Menemen, Kasaba

Kasaba or Kasabaköy is a village 17 kilometres outside Kastamonu, Turkey. It had a population of about 23,000 in 1905, when it had considerable local trade, but has since shrunk to only a few dozen households. Kasaba does not contain any ancie ...

, Bergama

Bergama is a populous district, as well as the center city of the same district, in İzmir Province in western Turkey. By excluding İzmir's metropolitan area, it is one of the prominent districts of the province in terms of population and is larg ...

and Ayvali.

Repatriation of refugees

The repatriation of the Asia Minor Greeks who had sought refuge in the Greek Kingdom as a result of the deportations and persecutions by the Ottoman authorities, assumed top priority, already from May 1919. The Greek authorities wanted to avoid a situation where refugees would return without the necessary supervision and planning. For this purpose, a special department was created within the High Commission. A survey conducted by the refugees department indicated that more than 150 towns and villages along the coastal area (from Edremit toSöke

Söke is a town and the largest district of Aydın Province in the Aegean region of western Turkey, 54 km (34 miles) south-west of the city of Aydın, near the Aegean coast. It had 121.940 population in 2020. It neighbours are Germencik fro ...

) had been destroyed during World War I. Especially from the 45,000 households belonging to local Greeks, 18,000 were partially damaged, while 23,000 completely destroyed.

In general the period of the Greek administration experienced a continuous movement of refugee populations aided by charitable institutions such as the Red Cross and the Greek "Patriotic Institution" ( el, Πατριωτικό Ίδρυμα). In total, 100,000 Greeks who had lost their land during World War I, many a result of Ottoman discrimination, were resettled under Stergiadis, given generous credit, and access to farm tools.

Muslim affairs

Following the Treaty of Sèvres, all sections of the Ottoman administration that dealt with issues pertaining to Muslim religion, education and family affairs were organized by the High Commission. Under this context a special polytechnic school was established in Smyrna which soon operated with 210 Muslim students and with costs covered by the Greek administration. However, nationalist sentiments and suspicion continued to limit the impacts of Stergiadis' administration. The resettlement of Greeks and harsh treatment by the army and local Greek population led many Turkish residents to leave which created a refugee problem. Discrimination by junior Greek administrators and military members further contributed to Turkish hostility in the Smyrna zone.

Archaeological excavations

Archaeological missions in Asia Minor were of significant importance for the High Commission. Excavations were focused onancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic peri ...

settlements in the area, mainly found in the surroundings of the urban areas, as well as along the coastal zone.Solomonidis, 1984, p. 182 The most important excavation were conducted during 1921–1922, where important findings were unearthed in the Ionia

Ionia () was an ancient region on the western coast of Anatolia, to the south of present-day Izmir. It consisted of the northernmost territories of the Ionian League of Greek settlements. Never a unified state, it was named after the Ionian ...

n sites of Klazomenai

Klazomenai ( grc, Κλαζομεναί) or Clazomenae was an ancient Greek city on the coast of Ionia and a member of the Ionian League. It was one of the first cities to issue silver coinage. Its ruins are now located in the modern town Urla n ...

, Ephesus

Ephesus (; grc-gre, Ἔφεσος, Éphesos; tr, Efes; may ultimately derive from hit, 𒀀𒉺𒊭, Apaša) was a city in ancient Greece on the coast of Ionia, southwest of present-day Selçuk in İzmir Province, Turkey. It was built in t ...

and Nysa

Nysa may refer to:

Greek Mythology

* Nysa (mythology) or Nyseion, the mountainous region or mount (various traditional locations), where nymphs raised the young god Dionysus

* Nysiads, nymphs of Mount Nysa who cared for and taught the infant ...

. Apart from ancient Greek antiquities, Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

monuments were also unearthed, such as the 6th century Basilica of St. John the Theologian in Ephesus. In general, the excavations undertaken by the Greek administration provided interesting material concerning the history of Ancient Greek and Byzantine Art.

University

Another important project undertaken during the Greek administration was the institution and organization of theIonian University of Smyrna

The Ionian University of Smyrna ( el, Ιωνικό Πανεπιστήμιο Σμύρνης) was a university established by the local Greek authorities during the Greek occupation of Smyrna (1919–1922), today Izmir, Turkey. The initiative for ...

. Originally conceived by the Greek Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos

Eleftherios Kyriakou Venizelos ( el, Ελευθέριος Κυριάκου Βενιζέλος, translit=Elefthérios Kyriákou Venizélos, ; – 18 March 1936) was a Greek statesman and a prominent leader of the Greek national liberation movem ...

and entrusted to Professor German-Greek mathematician Constantin Carathéodory

Constantin Carathéodory ( el, Κωνσταντίνος Καραθεοδωρή, Konstantinos Karatheodori; 13 September 1873 – 2 February 1950) was a Greek mathematician who spent most of his professional career in Germany. He made significant ...

of Göttingen University

Göttingen (, , ; nds, Chöttingen) is a university city in Lower Saxony, central Germany, the capital of the eponymous district. The River Leine runs through it. At the end of 2019, the population was 118,911.

General information

The orig ...

, as head of the new university. In the summer of 1922, its facilities were completed at a cost of 110,000 Turkish liras. The latter included 70 lecture rooms, a large amphitheatre, a number of laboratories and separate smaller structures for the university personnel. Its various schools and departments of the university were to start operating gradually. Moreover, a microbiology laboratory, the local Pasteur institute and the department of health became the first fields of instruction at the new university.

Developments in the Greco-Turkish War

In 1920, the Smyrna zone became a key base for the Greek summer offensive in the Greco-Turkish War. Early in July 1920, the allies approved operations by the Greeks to take over Eastern Thrace and territory around Smyrna as part of ongoing hostilities with the Turkish Nationalist movement. On 22 July 1920, Greek military divisions crossed the Milne line around the Smyrna zone and began military operations in the rest of Anatolia.

In 1920, the Smyrna zone became a key base for the Greek summer offensive in the Greco-Turkish War. Early in July 1920, the allies approved operations by the Greeks to take over Eastern Thrace and territory around Smyrna as part of ongoing hostilities with the Turkish Nationalist movement. On 22 July 1920, Greek military divisions crossed the Milne line around the Smyrna zone and began military operations in the rest of Anatolia.

International negotiations between the allies and the Ottoman administration largely ignored the increasing conflict. In early 1920, Lloyd George was able to convince the new French Prime Minister,

International negotiations between the allies and the Ottoman administration largely ignored the increasing conflict. In early 1920, Lloyd George was able to convince the new French Prime Minister, Alexandre Millerand

Alexandre Millerand (; – ) was a French politician. He was Prime Minister of France from 20 January to 23 September 1920 and President of France from 23 September 1920 to 11 June 1924. His participation in Waldeck-Rousseau's cabinet at the sta ...

to accept Greek control of Smyrna, but under Turkish suzerainty

Suzerainty () is the rights and obligations of a person, state or other polity who controls the foreign policy and relations of a tributary state, while allowing the tributary state to have internal autonomy. While the subordinate party is cal ...

. Negotiations were further refined in April 1920 at a meeting of the parties in Sanremo

Sanremo (; lij, Sanrémmo(ro) or , ) or San Remo is a city and comune on the Mediterranean coast of Liguria, in northwestern Italy. Founded in Roman times, it has a population of 55,000, and is known as a tourist destination on the Italian Rivie ...

which was designed to discuss mostly issues of Germany, but because of increasing power of the nationalist forces under Kemal, the discussion shifted to focus on Smyrna. French pressure and divisions within the British government resulted in Lloyd George accepting a time frame of 5 years for Greek control over Smyrna with the issue to be decided by the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

at that point. These decisions, i.e. regarding a Greek administration but with limited Turkish sovereignty and a 5-year limit, were included in the text of the Treaty of Sèvres

The Treaty of Sèvres (french: Traité de Sèvres) was a 1920 treaty signed between the Allies of World War I and the Ottoman Empire. The treaty ceded large parts of Ottoman territory to France, the United Kingdom, Greece and Italy, as well ...

agreed to on 10 August 1920. Because the treaty largely ignored the rise of nationalist forces and the ethnic tension in the Smyrna zone, Montgomery has described the Treaty of Sèvres as "stillborn". However, with the signing of the Treaty of Sèvres, the Ottoman Vali Izzet Bey handed over authority over Smyrna to Stergiadis.

In October 1920, Venizelos lost his position as Prime Minister of Greece. French and Italians used this opportunity to remove their support and financial obligations to the Smyrna occupation and this left the British as the only force supporting the Greek occupation. Smyrna remained a key base of operations for the ongoing war through the rest of 1920 and 1921, particularly under General Georgios Hatzianestis.

A significant loss at the Battle of Sakarya

The Battle of the Sakarya ( tr, Sakarya Meydan Muharebesi, lit=Sakarya Field Battle), also known as the Battle of the Sangarios ( el, Μάχη του Σαγγαρίου, Máchi tou Sangaríou), was an important engagement in the Greco-Turkish W ...

in September 1921 resulted in a retreat of Greek forces to the 1920 lines. The ensuing retreat resulted in massive civilian casualties and atrocities committed by Greek and Turkish troops. Jensen summarizes the violence writing that "The Turkish population was subjected to horrible atrocities by the retreating troops and accompanying civilian Christian mobs. The pursuing Turkish cavalry did not hesitate in kind on the Christian populace; the road from Uşak

Uşak (; el, Ουσάκειον, Ousakeion) is a city in the interior part of the Aegean Region of Turkey. The city has a population of 500,000 (2016 census) and is the capital of Uşak Province.

Uşak city is situated at a distance of from İ ...

to Smyrna lay littered with corpses."

Aftermath

Greek troops evacuated Smyrna on 9 September 1922 and a small allied force of British entered the city to prevent looting and violence. The next day, Mustafa Kemal, leading a number of troops, entered the city and was greeted by enthusiastic Turkish crowds. Atrocities by Turkish troops and irregulars against the Greek and Armenian population occurred immediately after the takeover. Most notably, Chrysostomos, the Orthodox Bishop, was lynched by a mob of Turkish citizens. A few days afterward, a fire destroyed the Greek and Armenian quarters of the city, while the Turkish and Jewish quarters remained undamaged. On the Turkish side the events are known as the Liberation of İzmir, while on the Greek side as Catastrophe of Smyrna.

The evacuation of Smyrna by Greek troops ended most of the large scale fighting in the Greco-Turkish war which was formally ended with an Armistice and a final treaty on 24 July 1923 with the Treaty of Lausanne. Much of the Greek population was included in the 1923

Greek troops evacuated Smyrna on 9 September 1922 and a small allied force of British entered the city to prevent looting and violence. The next day, Mustafa Kemal, leading a number of troops, entered the city and was greeted by enthusiastic Turkish crowds. Atrocities by Turkish troops and irregulars against the Greek and Armenian population occurred immediately after the takeover. Most notably, Chrysostomos, the Orthodox Bishop, was lynched by a mob of Turkish citizens. A few days afterward, a fire destroyed the Greek and Armenian quarters of the city, while the Turkish and Jewish quarters remained undamaged. On the Turkish side the events are known as the Liberation of İzmir, while on the Greek side as Catastrophe of Smyrna.

The evacuation of Smyrna by Greek troops ended most of the large scale fighting in the Greco-Turkish war which was formally ended with an Armistice and a final treaty on 24 July 1923 with the Treaty of Lausanne. Much of the Greek population was included in the 1923 population exchange between Greece and Turkey

The 1923 population exchange between Greece and Turkey ( el, Ἡ Ἀνταλλαγή, I Antallagí, ota, مبادله, Mübâdele, tr, Mübadele) stemmed from the "Convention Concerning the Exchange of Greek and Turkish Populations" signed at ...

resulting in migration to Greece and elsewhere.

References

Sources

*Further reading

Documents

of the Inter-Allied Commission of Inquiry into the Greek Occupation of Smyrna and Adjoining Territories.

"Remembering Smyrna/Izmir: Shared History, Shared Trauma" by Leyla Neyzi

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Occupation of Smyrna Former countries of the interwar period *

Smyrna

Smyrna ( ; grc, Σμύρνη, Smýrnē, or , ) was a Greek city located at a strategic point on the Aegean coast of Anatolia. Due to its advantageous port conditions, its ease of defence, and its good inland connections, Smyrna rose to promi ...

Smyrna

Smyrna ( ; grc, Σμύρνη, Smýrnē, or , ) was a Greek city located at a strategic point on the Aegean coast of Anatolia. Due to its advantageous port conditions, its ease of defence, and its good inland connections, Smyrna rose to promi ...

Smyrna

Smyrna ( ; grc, Σμύρνη, Smýrnē, or , ) was a Greek city located at a strategic point on the Aegean coast of Anatolia. Due to its advantageous port conditions, its ease of defence, and its good inland connections, Smyrna rose to promi ...

1919 in the Ottoman Empire

1920 in the Ottoman Empire

1921 in the Ottoman Empire

1922 in the Ottoman Empire

Smyrna

Smyrna ( ; grc, Σμύρνη, Smýrnē, or , ) was a Greek city located at a strategic point on the Aegean coast of Anatolia. Due to its advantageous port conditions, its ease of defence, and its good inland connections, Smyrna rose to promi ...

Smyrna

Smyrna ( ; grc, Σμύρνη, Smýrnē, or , ) was a Greek city located at a strategic point on the Aegean coast of Anatolia. Due to its advantageous port conditions, its ease of defence, and its good inland connections, Smyrna rose to promi ...

Smyrna

Smyrna ( ; grc, Σμύρνη, Smýrnē, or , ) was a Greek city located at a strategic point on the Aegean coast of Anatolia. Due to its advantageous port conditions, its ease of defence, and its good inland connections, Smyrna rose to promi ...

Smyrna

Smyrna ( ; grc, Σμύρνη, Smýrnē, or , ) was a Greek city located at a strategic point on the Aegean coast of Anatolia. Due to its advantageous port conditions, its ease of defence, and its good inland connections, Smyrna rose to promi ...

Military occupation