Out West (magazine) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''The Land of Sunshine'' was a

In 1898, Lummis expanded the scope of the magazine to include the entire West, which he defined as anything "which is far enough away from the East to be Out from Under". This was accentuated by the magazine's change of name to ''Out West'' in January 1902. During his tenure as editor, Lummis maintained relations of various kinds with other periodicals, both in the

In 1898, Lummis expanded the scope of the magazine to include the entire West, which he defined as anything "which is far enough away from the East to be Out from Under". This was accentuated by the magazine's change of name to ''Out West'' in January 1902. During his tenure as editor, Lummis maintained relations of various kinds with other periodicals, both in the  Lummis edited the magazine by himself until the February 1903 issue, when he was joined by Charles Amadon Moody: together, they would edit the magazine until Lummis departed in November 1909. According to Bingham, the magazine's influence and reputation as one of the

Lummis edited the magazine by himself until the February 1903 issue, when he was joined by Charles Amadon Moody: together, they would edit the magazine until Lummis departed in November 1909. According to Bingham, the magazine's influence and reputation as one of the

Throughout its early existence, ''The Land of Sunshine'' had difficulty securing contributions from freelance writers, largely because of its specific focus on Californian and Western themes and its inability to pay standard rates. The issue was so acute when Lummis began editing the magazine that he often contributed a "disproportionate" amount of content, which sometimes resulted in him resorting to contributing under transparent

Throughout its early existence, ''The Land of Sunshine'' had difficulty securing contributions from freelance writers, largely because of its specific focus on Californian and Western themes and its inability to pay standard rates. The issue was so acute when Lummis began editing the magazine that he often contributed a "disproportionate" amount of content, which sometimes resulted in him resorting to contributing under transparent

magazine

A magazine is a periodical publication, generally published on a regular schedule (often weekly or monthly), containing a variety of content. They are generally financed by advertising, purchase price, prepaid subscriptions, or by a combinatio ...

published in Los Angeles

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the largest city in the state of California and the second most populous city in the United States after New York City, as well as one of the world' ...

, California

California is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, located along the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the List of states and territori ...

, between 1894 and 1923. It was renamed ''Out West'' in January 1902. In 1923, it merged into ''Overland Monthly

The ''Overland Monthly'' was a monthly literary and cultural magazine, based in California, United States. It was founded in 1868 and published between the second half of the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century.

History

The '' ...

'' to become ''Overland Monthly and Out West Magazine'', which existed until 1935. The magazine published the work of many notable authors, including John Muir

John Muir ( ; April 21, 1838December 24, 1914), also known as "John of the Mountains" and "Father of the National Parks", was an influential Scottish-American naturalist, author, environmental philosopher, botanist, zoologist, glaciologist, a ...

, Jack London

John Griffith Chaney (January 12, 1876 – November 22, 1916), better known as Jack London, was an American novelist, journalist and activist. A pioneer of commercial fiction and American magazines, he was one of the first American authors to ...

, Mary Hunter Austin

Mary Hunter Austin (September 9, 1868 – August 13, 1934) was an American writer. One of the early nature writers of the American Southwest, her classic '' The Land of Little Rain'' (1903) describes the fauna, flora, and people – as well as e ...

, Sharlot Hall

Sharlot Mabridth Hall (October 27, 1870 – April 9, 1943) was an American journalist, poet and historian. She was the first woman to hold an office in the Arizona Territorial government and her personal collection of photographs and artifacts ...

, Grace Ellery Channing

Grace Ellery Channing (December 27, 1862 – April 3, 1937) was a writer and poet who published often in ''The Land of Sunshine''.

Early life

She was born to William Francis Channing and Mary Jane (née Tarr) on December 27, 1862 in Providence, ...

, and Sui Sin Far

Sui Sin Far (, born Edith Maude Eaton; 15 March 1865 – 7 April 1914) was an author known for her writing about Chinese people in North America and the Chinese American experience. "Sui Sin Far", the pen name under which most of her work was pu ...

(Edith Maude Eaton). ''The Land of Sunshine'' was also known for its "lavish" use of illustrations, many of which were halftone photoengravings. In the words of Jon Wilkman, the magazine "extolled the wonders of Southern California

Southern California (commonly shortened to SoCal) is a geographic and Cultural area, cultural region that generally comprises the southern portion of the U.S. state of California. It includes the Los Angeles metropolitan area, the second most po ...

and had a major influence on the region’s early image and appeal to tourists".

History

''The Land of Sunshine'' was first published by the F. A. Pattee Publishing Company in June 1894 as aquarto

Quarto (abbreviated Qto, 4to or 4º) is the format of a book or pamphlet produced from full sheets printed with eight pages of text, four to a side, then folded twice to produce four leaves. The leaves are then trimmed along the folds to produc ...

measuring . It was originally ghost-edited by Charles Dwight Willard, while Harry Ellington Brook and Frank A. Pattee were both also involved in the creation and publication of the magazine. Willard was secretary of the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce

The Los Angeles Area Chamber of Commerce is Southern California's largest not-for-profit business federation, representing the interests of more than 235,000 businesses in L.A. County, more than 1,400 member companies and more than 722,430 employ ...

while he edited ''The Land of Sunshine'', which from its inception was supportive of commercial interests in Los Angeles and San Diego

San Diego ( , ; ) is a city on the Pacific Ocean coast of Southern California located immediately adjacent to the Mexico–United States border. With a 2020 population of 1,386,932, it is the List of United States cities by population, eigh ...

to the extent that it would have caused a clear conflict of interest

A conflict of interest (COI) is a situation in which a person or organization is involved in multiple interests, financial or otherwise, and serving one interest could involve working against another. Typically, this relates to situations i ...

controversy if Willard was publicly linked to the magazine. According to Edwin Bingham, in its first volume ''The Land of Sunshine'' developed a long-standing dichotomy between covering regional commerce and culture. From its beginning, the magazine also took concerted measures to increase its circulation, including both imploring its readers to share copies with their friends and supplying public libraries

A public library is a library that is accessible by the general public and is usually funded from public sources, such as taxes. It is operated by librarians and library paraprofessionals, who are also civil servants.

There are five fundamenta ...

around the United States with issues of the magazine.

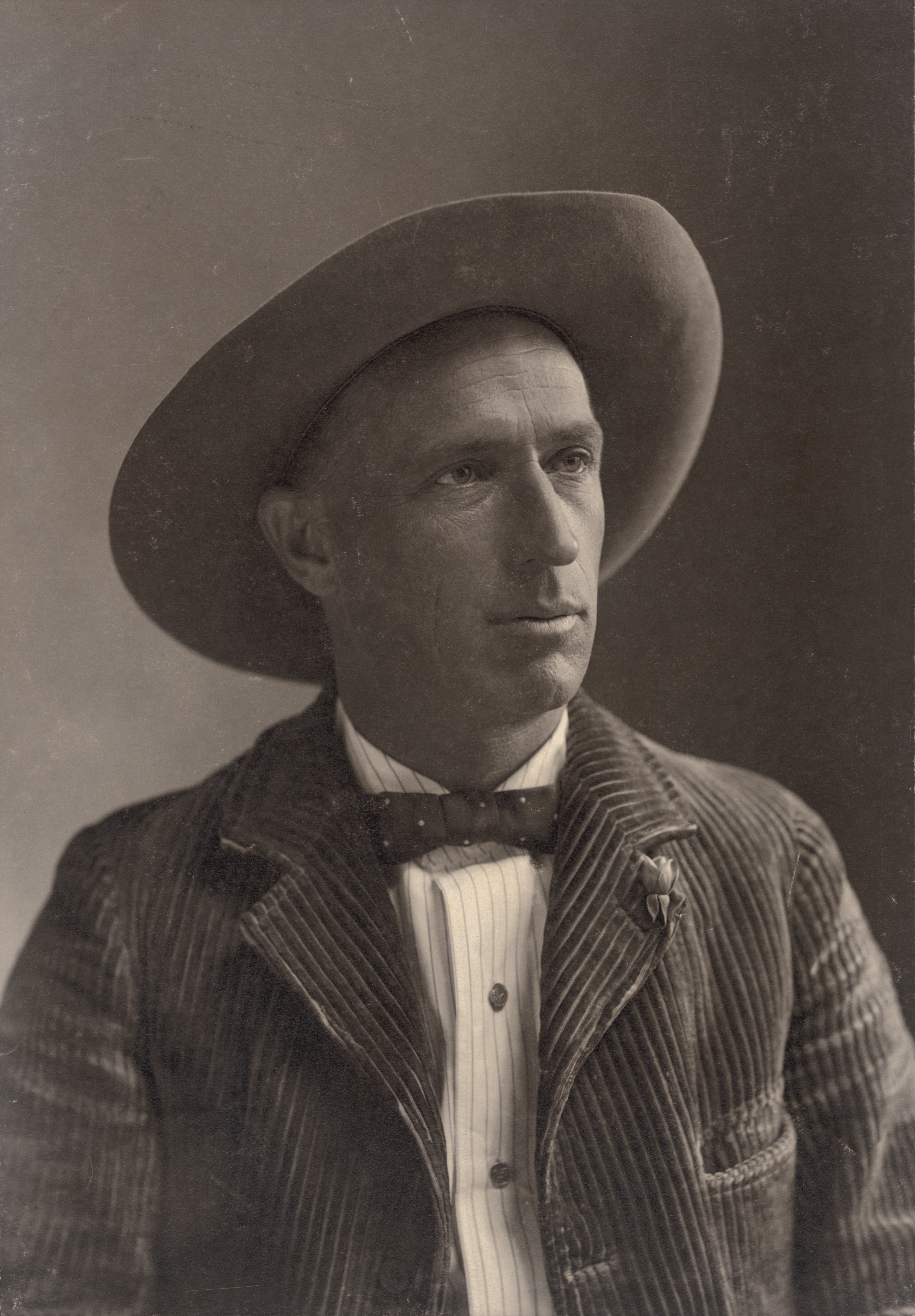

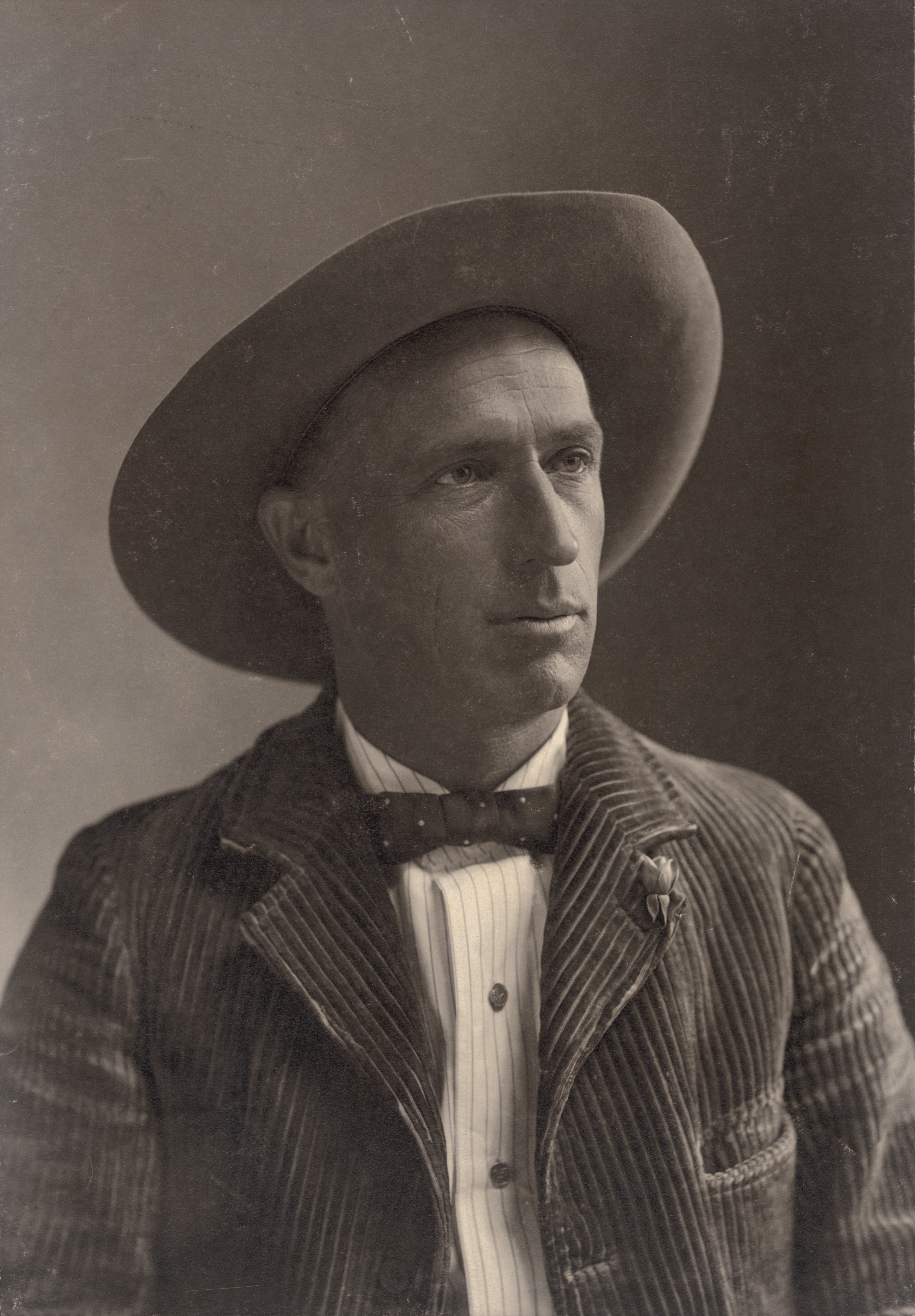

At the end of 1894 Charles Fletcher Lummis

Charles Fletcher Lummis (March 1, 1859, in Lynn, Massachusetts – November 25, 1928, in Los Angeles, California) was a United States journalist, and an activist for Indian rights and historic preservation. A traveler in the American Southwest, h ...

was publicly named editor of ''The Land of Sunshine'', and the first issue produced under his control was January 1895. Lummis promised that the magazine's coverage of Southern California would be "concise, interesting, expert, accurate" to the extent that it would be trusted by Eastern

Eastern may refer to:

Transportation

*China Eastern Airlines, a current Chinese airline based in Shanghai

*Eastern Air, former name of Zambia Skyways

*Eastern Air Lines, a defunct American airline that operated from 1926 to 1991

*Eastern Air Li ...

readers. He also placed an increased emphasis on the cultural and intellectual content of the magazine. According to the ''Los Angeles Times

The ''Los Angeles Times'' (abbreviated as ''LA Times'') is a daily newspaper that started publishing in Los Angeles in 1881. Based in the LA-adjacent suburb of El Segundo since 2018, it is the sixth-largest newspaper by circulation in the Un ...

'', he transformed the magazine from a "Chamber of Commerce promotional sheet" into a "sterling literary magazine" in which he voiced his own opinions about everything from art and philosophy to politics and current events. Perhaps his favorite subjects, however, were championing Native American rights and criticizing the Federal Indian Policy Federal Indian policy establishes the relationship between the United States Government and the Indian Tribes within its borders. The Constitution gives the federal government primary responsibility for dealing with tribes. Some scholars divide the ...

. Lummis was regarded as an "impulsive firebrand" as a thinker and a writer, and his ideas, both in ''The Land of Sunshine'' and other works, often had a polarizing effect on other writers and academics. In June 1895, the magazine was reduced to dimensions of , although its total number of pages grew.

In 1898, Lummis expanded the scope of the magazine to include the entire West, which he defined as anything "which is far enough away from the East to be Out from Under". This was accentuated by the magazine's change of name to ''Out West'' in January 1902. During his tenure as editor, Lummis maintained relations of various kinds with other periodicals, both in the

In 1898, Lummis expanded the scope of the magazine to include the entire West, which he defined as anything "which is far enough away from the East to be Out from Under". This was accentuated by the magazine's change of name to ''Out West'' in January 1902. During his tenure as editor, Lummis maintained relations of various kinds with other periodicals, both in the Western United States

The Western United States (also called the American West, the Far West, and the West) is the region comprising the westernmost states of the United States. As American settlement in the U.S. expanded westward, the meaning of the term ''the Wes ...

and the country at large: this included amicable relations with ''The Nation

''The Nation'' is an American liberal biweekly magazine that covers political and cultural news, opinion, and analysis. It was founded on July 6, 1865, as a successor to William Lloyd Garrison's '' The Liberator'', an abolitionist newspaper tha ...

'' and ''The Dial

''The Dial'' was an American magazine published intermittently from 1840 to 1929. In its first form, from 1840 to 1844, it served as the chief publication of the Transcendentalists. From the 1880s to 1919 it was revived as a political review and ...

'', an antagonistic relationship with ''Overland Monthly'', and a more complex relationship with ''The Argonaut

''The Argonaut'' was a newspaper based in San Francisco, California from 1878 to 1956. It was founded by Frank Somers, and soon taken over by Frank M. Pixley, who built it into a highly regarded publication. Under Pixley's stewardship it was c ...

'', as Lummis lauded the latter's anti-imperialist

Anti-imperialism in political science and international relations is a term used in a variety of contexts, usually by nationalist movements who want to secede from a larger polity (usually in the form of an empire, but also in a multi-ethnic so ...

stance but criticized it for at times being anti-Catholic

Anti-Catholicism is hostility towards Catholics or opposition to the Catholic Church, its Hierarchy of the Catholic Church, clergy, and/or its adherents. At various points after the Reformation, some majority Protestantism, Protestant states, ...

.

Lummis edited the magazine by himself until the February 1903 issue, when he was joined by Charles Amadon Moody: together, they would edit the magazine until Lummis departed in November 1909. According to Bingham, the magazine's influence and reputation as one of the

Lummis edited the magazine by himself until the February 1903 issue, when he was joined by Charles Amadon Moody: together, they would edit the magazine until Lummis departed in November 1909. According to Bingham, the magazine's influence and reputation as one of the Pacific Coast

Pacific coast may be used to reference any coastline that borders the Pacific Ocean.

Geography Americas

Countries on the western side of the Americas have a Pacific coast as their western or southwestern border, except for Panama, where the Pac ...

's premier publications ended with Lummis' departure. ''Out West'' subsequently witnessed a succession of editors that included C. F. Edholm, George Wharton James

George Wharton James (27 September 1858 – 8 November 1923) was an American popular lecturer, photographer, journalist and editor. Born in Lincolnshire, England, he emigrated to the United States as a young man after being ordained as a Methodis ...

, and Lannie Haynes Martin, and it "ceased to appear with any regularity" after its June 1917 issue. In May 1923, it was consolidated with ''Overland Monthly'' to form ''Overland Monthly and Out West Magazine'', which remained in publication until July 1935.

Publication and circulation

At the beginning of its existence, ''The Land of Sunshine'' was printed and bound by Kingsley-Barnes and Neuner Company in the Stimson Building while its photoengraving needs were handled by a variety of local companies. In 1898, the magazine began in-house publication in a building on South Broadway that combined editorial and printing functions, which by late 1901 boasted six job presses and four cylinder presses, one of which was an Optimus cylinder used principally for printing illustrated pages. In April 1904, the printing of the magazine was once again physically separated from its editorial offices, and this arrangement persisted until Lummis departed in 1909. Initially, ''The Land of Sunshine'' was published by the F. A. Pattee Publishing Company, but in August 1895 these duties were assumed by the newly incorporated Land of Sunshine Publishing Co., which at its inception consisted of W.C. Patterson (president), Lummis (vice president), Pattee (secretary and business manager), H.J. Fleishman (treasurer), Charles Cassat Davis (attorney), and Cyrus M. Davis. While Willard initially had the largest individual financial stake in the magazine, Lummis eventually bought him out with financial backing fromPhoebe Hearst

Phoebe Elizabeth Apperson Hearst (December 3, 1842 – April 13, 1919) was an American philanthropist, feminist and suffragist. Hearst was the founder of the University of California Museum of Anthropology, now called the Phoebe A. Hearst Mus ...

, the mother of newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst

William Randolph Hearst Sr. (; April 29, 1863 – August 14, 1951) was an American businessman, newspaper publisher, and politician known for developing the nation's largest newspaper chain and media company, Hearst Communications. His flamboya ...

. Lummis retained his interests in the magazine until his departure from it in 1909.

''The Land of Sunshines circulation reached 9,000 in December 1895, which its publishers claimed was "the largest certified regular circulation of any western monthly". In July 1899, the magazine's average circulation was 9,147. The magazine enjoyed its highest circulation in 1903 (10,766) and 1904 (an estimated 15,000). Measuring the circulation of ''Out West'' after 1903 is challenging because the actual figures were not kept or provided to newspaper directories, which resorted to consistently estimating its circulation at between 7,500 and 12,500 after 1904.

In the United States, most of the magazine's subscribers were in California, followed in decreasing order by the Arizona Territory

The Territory of Arizona (also known as Arizona Territory) was a territory of the United States that existed from February 24, 1863, until February 14, 1912, when the remaining extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as the state of ...

, New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

, Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett language, Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut assachusett writing systems, məhswatʃəwiːsət'' English: , ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is the most populous U.S. state, state in the New England ...

, and the New Mexico Territory

The Territory of New Mexico was an organized incorporated territory of the United States from September 9, 1850, until January 6, 1912. It was created from the U.S. provisional government of New Mexico, as a result of ''Santa Fe de Nuevo México ...

. ''The Land of Sunshine'' counted Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

as one of its subscribers, and he told Lummis that during his Presidency

A presidency is an administration or the executive, the collective administrative and governmental entity that exists around an office of president of a state or nation. Although often the executive branch of government, and often personified by a ...

it was the only magazine that he "took time to read". The magazine also had some semblance of an international scope: in January 1907, ''Out West'' claimed subscribers in England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

, Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to th ...

, Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

, Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

, Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

, France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden,The United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names states that the country's formal name is the Kingdom of SwedenUNGEGN World Geographical Names, Sweden./ref> is a Nordic country located on ...

, Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

, New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island count ...

, Mexico

Mexico (Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a country in the southern portion of North America. It is bordered to the north by the United States; to the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; to the southeast by Guatema ...

, Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders with ...

, Siam

Thailand ( ), historically known as Siam () and officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country in Southeast Asia, located at the centre of the Mainland Southeast Asia, Indochinese Peninsula, spanning , with a population of almost 70 mi ...

, and North China

North China, or Huabei () is a List of regions of China, geographical region of China, consisting of the provinces of Beijing, Tianjin, Hebei, Shanxi and Inner Mongolia. Part of the larger region of Northern China (''Beifang''), it lies north ...

.

Contributors

Throughout its early existence, ''The Land of Sunshine'' had difficulty securing contributions from freelance writers, largely because of its specific focus on Californian and Western themes and its inability to pay standard rates. The issue was so acute when Lummis began editing the magazine that he often contributed a "disproportionate" amount of content, which sometimes resulted in him resorting to contributing under transparent

Throughout its early existence, ''The Land of Sunshine'' had difficulty securing contributions from freelance writers, largely because of its specific focus on Californian and Western themes and its inability to pay standard rates. The issue was so acute when Lummis began editing the magazine that he often contributed a "disproportionate" amount of content, which sometimes resulted in him resorting to contributing under transparent pseudonym

A pseudonym (; ) or alias () is a fictitious name that a person or group assumes for a particular purpose, which differs from their original or true name (orthonym). This also differs from a new name that entirely or legally replaces an individua ...

s such as C. Arloz and C. R. Lohs, references to his nickname Don Carlos.

In an effort to recruit writers for the magazine, Lummis organized a "syndicate of established writers" interested in writing Western content and paid them with stock certificate

In corporate law, a stock certificate (also known as certificate of stock or share certificate) is a legal document that certifies the legal interest (a bundle of several legal rights) of ownership of a specific number of shares (or, under Ar ...

s in the Land of Sunshine Publishing Co. in lieu of cash payments. Members of this syndicate, which included different types of writers as well as artists, included George Parker Winship

George Parker Winship (29 July 1871 – 22 June 1952) was an American librarian, author, teacher, and bibliographer born in Bridgewater, Massachusetts. He graduated from Harvard in 1893.

Early life and career

Went from the Somerville La ...

, Frederick Webb Hodge Frederick Webb Hodge (October 28, 1864 – September 28, 1956) was an American editor, anthropologist, archaeologist, and historian. Born in England, he immigrated at the age of seven with his family to Washington, DC. He was educated at America ...

, Maynard Dixon

Maynard Dixon (January 24, 1875 – November 11, 1946) was an American artist. He was known for his paintings, and his body of work focused on the American West. Dixon is considered one of the finest artists having dedicated most of their art ...

, William Keith, Ina Coolbrith

Ina Donna Coolbrith (born Josephine Donna Smith; March 10, 1841 – February 29, 1928) was an American poet, writer, librarian, and a prominent figure in the San Francisco Bay Area literary community. Called the "Sweet Singer of California", sh ...

, Edwin Markham

Edwin Markham (born Charles Edward Anson Markham; April 23, 1852 – March 7, 1940) was an American poet. From 1923 to 1931 he was Poet Laureate of Oregon.

Life

Edwin Markham was born in Oregon City, Oregon, and was the youngest of 10 children; ...

, Theodore H. Hittell, David Starr Jordan

David Starr Jordan (January 19, 1851 – September 19, 1931) was the founding president of Stanford University, serving from 1891 to 1913. He was an ichthyologist during his research career. Prior to serving as president of Stanford Univer ...

, Ella Higginson, John Vance Cheney, Charles Warren Stoddard

Charles Warren Stoddard (August 7, 1843 April 23, 1909) was an American author and editor best known for his travel books about Polynesian life.

Biography

Charles Warren Stoddard was born in Rochester, New York on August 7, 1843. He was desce ...

, George Hamlin Fitch, Washington Matthews

Washington Matthews (June 17, 1843 – March 2, 1905) was a surgeon in the United States Army, ethnographer, and linguist known for his studies of Native American peoples, especially the Navajo.

Early life and education

Matthews was born in Ki ...

, Charles

Charles is a masculine given name predominantly found in English language, English and French language, French speaking countries. It is from the French form ''Charles'' of the Proto-Germanic, Proto-Germanic name (in runic alphabet) or ''*k ...

and Louise Keller, Charlotte Perkins Stetson

Charlotte Perkins Gilman (; née Perkins; July 3, 1860 – August 17, 1935), also known by her first married name Charlotte Perkins Stetson, was an American humanist, novelist, writer, lecturer, advocate for social reform, and eugenicist. She wa ...

, Joaquin Miller

Cincinnatus Heine Miller (; September 8, 1837 – February 17, 1913), better known by his pen name Joaquin Miller (), was an American poet, author, and frontiersman. He is nicknamed the "Poet of the Sierras" after the Sierra Nevada, about which h ...

, Elliott Coues

Elliott Ladd Coues (; September 9, 1842 – December 25, 1899) was an American army surgeon, historian, ornithologist, and author. He led surveys of the Arizona Territory, and later as secretary of the United States Geological and Geographic ...

, Eugene Manlove Rhodes

Eugene Manlove Rhodes (January 19, 1869 – June 27, 1934) was an American writer, nicknamed the "cowboy chronicler". He lived in south central New Mexico when the first cattle ranching and cowboys arrived in the area; when he moved to New York wi ...

, Sharlot Hall

Sharlot Mabridth Hall (October 27, 1870 – April 9, 1943) was an American journalist, poet and historian. She was the first woman to hold an office in the Arizona Territorial government and her personal collection of photographs and artifacts ...

, and Mary Hunter Austin

Mary Hunter Austin (September 9, 1868 – August 13, 1934) was an American writer. One of the early nature writers of the American Southwest, her classic '' The Land of Little Rain'' (1903) describes the fauna, flora, and people – as well as e ...

. Grace Ellery Channing

Grace Ellery Channing (December 27, 1862 – April 3, 1937) was a writer and poet who published often in ''The Land of Sunshine''.

Early life

She was born to William Francis Channing and Mary Jane (née Tarr) on December 27, 1862 in Providence, ...

was also a prominent contributor to ''The Land of Sunshine''.

Over the history of the magazine, Lummis contributed the most content: a total of more than 250 essays, articles, poems, and stories. After him, the next most frequent contributors were William E. Smythe

William Ellsworth Smythe, known as W. E. Smythe (1861–1922), was a journalist, writer and founder of the Little Landers movement, which aimed to settle small suburban lots with people who would farm their own properties, live off the land and sel ...

(with 48 total contributions), Sharlot Hall (42), and Julia Boynton Green (23). In addition to writing for the magazine, Lummis also founded two organizations of similar scope and purpose: the Landmarks Club, which was dedicated to preserving the Spanish missions in the region from further deterioration, and the Southwest Society, which ultimately evolved into the Southwest Museum of the American Indian

The Southwest Museum of the American Indian is a museum, library, and archive located in the Mt. Washington neighborhood of Los Angeles, California, above the north-western bank of the Arroyo Seco (Los Angeles County) canyon and stream. The muse ...

.

References

External links

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Land of Sunshine, The 1894 establishments in California 1923 disestablishments in California Defunct magazines published in the United States History of California History of the American West Local interest magazines published in the United States Magazines established in 1894 Magazines disestablished in 1923 Magazines published in Los Angeles Monthly magazines published in the United States