Ostend Manifesto on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Ostend Manifesto, also known as the Ostend Circular, was a document written in 1854 that described the rationale for the United States to purchase

The Ostend Manifesto, also known as the Ostend Circular, was a document written in 1854 that described the rationale for the United States to purchase

Marcy suggested Soulé confer with Buchanan and

Marcy suggested Soulé confer with Buchanan and

When the document was published, Northerners were outraged by what they considered a Southern attempt to extend slavery. American free-soilers, recently angered by the strengthened

When the document was published, Northerners were outraged by what they considered a Southern attempt to extend slavery. American free-soilers, recently angered by the strengthened

The Ostend Manifesto, also known as the Ostend Circular, was a document written in 1854 that described the rationale for the United States to purchase

The Ostend Manifesto, also known as the Ostend Circular, was a document written in 1854 that described the rationale for the United States to purchase Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

from Spain while implying that the U.S. should declare war if Spain refused. Cuba's annexation had long been a goal of U.S. slaveholding expansionists. At the national level, American leaders had been satisfied to have the island remain in weak Spanish hands so long as it did not pass to a stronger power such as Britain or France. The Ostend Manifesto proposed a shift in foreign policy, justifying the use of force to seize Cuba in the name of national security. It resulted from debates over slavery in the United States

The legal institution of human chattel slavery, comprising the enslavement primarily of Africans and African Americans, was prevalent in the United States of America from its founding in 1776 until 1865, predominantly in the South. Sl ...

, manifest destiny

Manifest destiny was a cultural belief in the 19th century in the United States, 19th-century United States that American settlers were destined to expand across North America.

There were three basic tenets to the concept:

* The special vir ...

, and the Monroe Doctrine

The Monroe Doctrine was a United States foreign policy position that opposed European colonialism in the Western Hemisphere. It held that any intervention in the political affairs of the Americas by foreign powers was a potentially hostile ac ...

, as slaveholders sought new territory for the expansion of slavery.

During the administration

Administration may refer to:

Management of organizations

* Management, the act of directing people towards accomplishing a goal

** Administrative assistant, Administrative Assistant, traditionally known as a Secretary, or also known as an admini ...

of President Franklin Pierce

Franklin Pierce (November 23, 1804October 8, 1869) was the 14th president of the United States, serving from 1853 to 1857. He was a northern Democrat who believed that the abolitionist movement was a fundamental threat to the nation's unity ...

, a pro-Southern Democrat, Southern expansionists called for acquiring Cuba as a slave state

In the United States before 1865, a slave state was a state in which slavery and the internal or domestic slave trade were legal, while a free state was one in which they were not. Between 1812 and 1850, it was considered by the slave states ...

, but the outbreak of violence following the Kansas–Nebraska Act

The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 () was a territorial organic act that created the territories of Kansas and Nebraska. It was drafted by Democratic Senator Stephen A. Douglas, passed by the 33rd United States Congress, and signed into law by ...

left the administration unsure of how to proceed. At the suggestion of Secretary of State William L. Marcy

William Learned Marcy (December 12, 1786July 4, 1857) was an American lawyer, politician, and judge who served as U.S. Senator, Governor of New York, U.S. Secretary of War and U.S. Secretary of State. In the latter office, he negotiated the Gad ...

, American ministers in Europe— Pierre Soulé for Spain, James Buchanan

James Buchanan Jr. ( ; April 23, 1791June 1, 1868) was an American lawyer, diplomat and politician who served as the 15th president of the United States from 1857 to 1861. He previously served as secretary of state from 1845 to 1849 and repr ...

for Britain, and John Y. Mason

John Young Mason (April 18, 1799October 3, 1859) was a United States representative from Virginia, the 16th and 18th United States Secretary of the Navy, the 18th Attorney General of the United States, United States Ambassador to France, United ...

for France—met to discuss strategy related to an acquisition of Cuba. They met secretly at Ostend

Ostend ( nl, Oostende, ; french: link=no, Ostende ; german: link=no, Ostende ; vls, Ostende) is a coastal city and municipality, located in the province of West Flanders in the Flemish Region of Belgium. It comprises the boroughs of Mariakerk ...

, Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to th ...

, and drafted a dispatch at Aachen

Aachen ( ; ; Aachen dialect: ''Oche'' ; French and traditional English: Aix-la-Chapelle; or ''Aquisgranum''; nl, Aken ; Polish: Akwizgran) is, with around 249,000 inhabitants, the 13th-largest city in North Rhine-Westphalia, and the 28th- ...

, Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an em ...

. The document was sent to Washington in October 1854, outlining why a purchase of Cuba would be beneficial to each of the nations and declaring that the U.S. would be "justified in wresting" the island from Spanish hands if Spain refused to sell. To Marcy's chagrin, Soulé made no secret of the meetings, causing unwanted publicity in both Europe and the U.S. The administration was finally forced to publish the contents of the dispatch, which caused it irreparable damage.

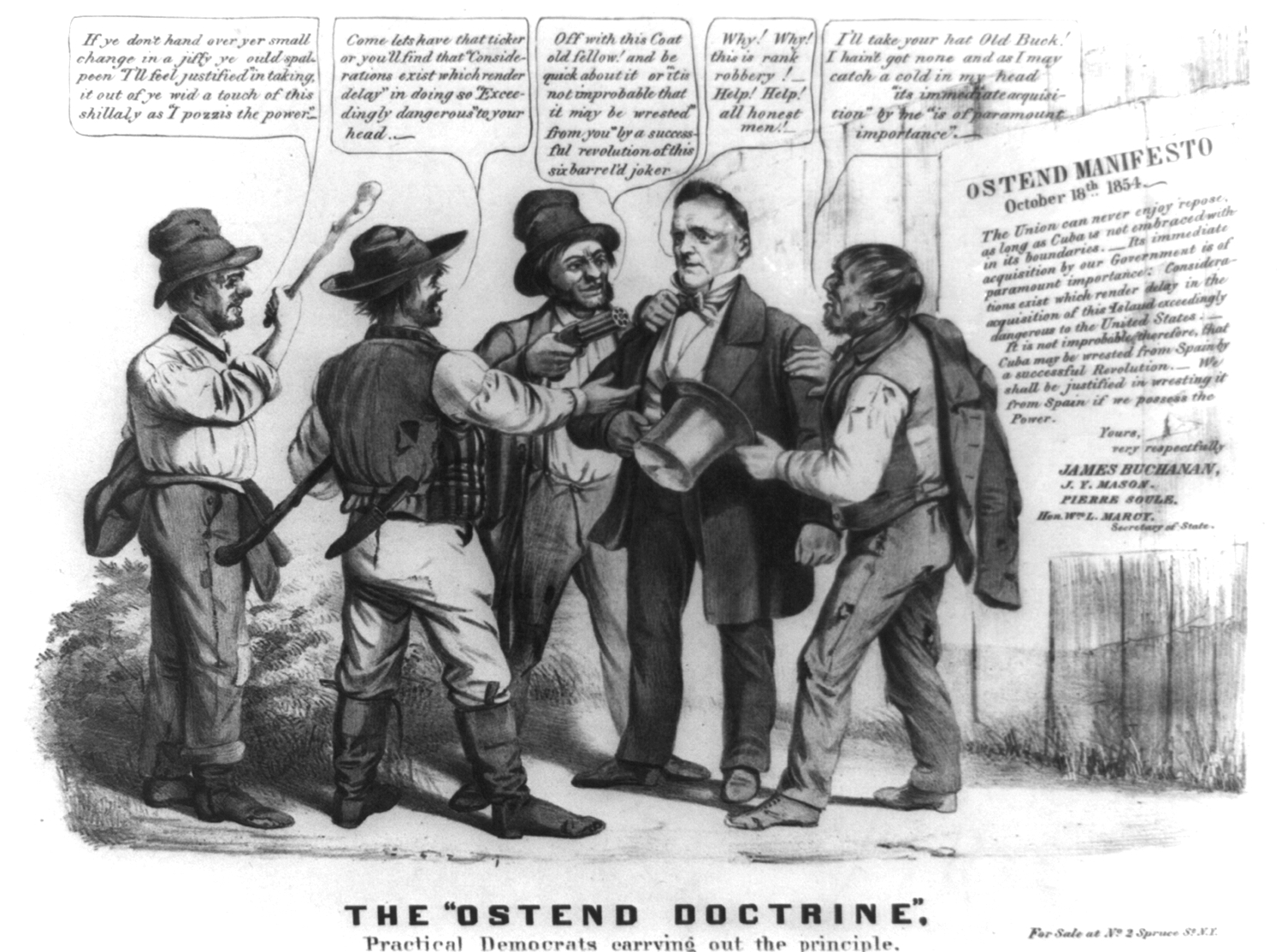

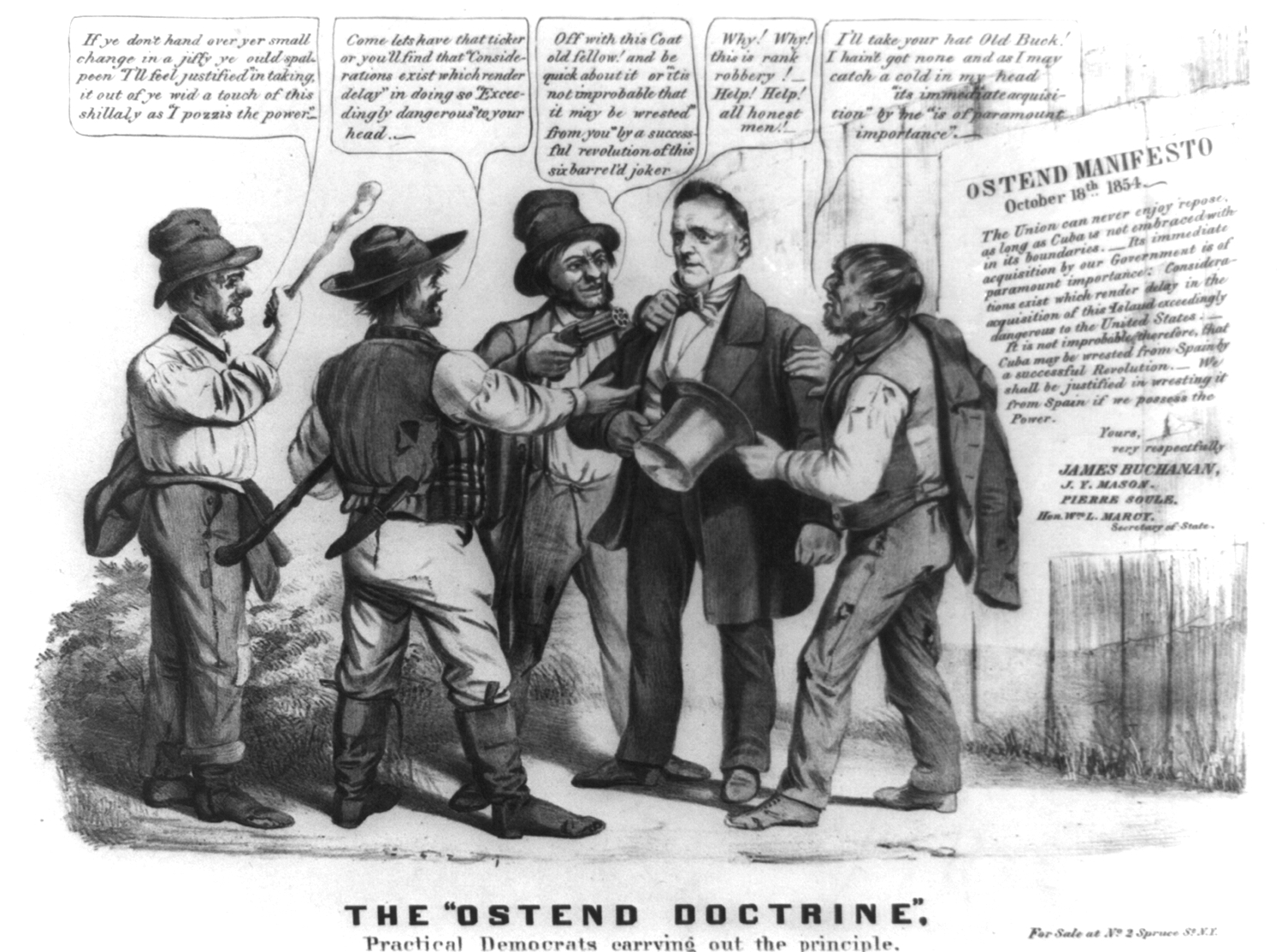

The dispatch was published as demanded by the House of Representatives. Dubbed the "Ostend Manifesto", it was immediately denounced in both the Northern states and Europe. The Pierce administration suffered a significant setback, and the manifesto became a rallying cry for anti-slavery Northerners. The question of Cuba's annexation was effectively set aside until the late 19th century, when support grew for Cuban independence from Spain.

Historical context

Located off the coast ofFlorida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and to ...

, Cuba had been discussed as a subject for annexation

Annexation (Latin ''ad'', to, and ''nexus'', joining), in international law, is the forcible acquisition of one state's territory by another state, usually following military occupation of the territory. It is generally held to be an illegal act ...

in several presidential administrations. Presidents John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, and diarist who served as the sixth president of the United States, from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States S ...

and Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

expressed great interest in Cuba, with Adams observing during his Secretary of State tenure that it had "become an object of transcendent importance to the commercial and political interests of our Union". He later described Cuba and Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico (; abbreviated PR; tnq, Boriken, ''Borinquen''), officially the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico ( es, link=yes, Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico, lit=Free Associated State of Puerto Rico), is a Caribbean island and Unincorporated ...

as "natural appendages to the North American continent"—the former's annexation was "indispensable to the continuance and integrity of the Union itself." As the Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire ( es, link=no, Imperio español), also known as the Hispanic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Hispánica) or the Catholic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Católica) was a colonial empire governed by Spain and its prede ...

had lost much of its power, a no-transfer policy began with Jefferson whereby the U.S. respected Spanish sovereignty, considering the island's eventual absorption inevitable. The U.S. simply wanted to ensure that control did not pass to a stronger power such as Britain or France.

Cuba was of special importance to Southern Democrats, who believed their economic and political interests would be best served by the admission of another slave state to the Union. The existence of slavery in Cuba

Slavery in Cuba was a portion of the larger Atlantic Slave Trade that primarily supported Spanish plantation owners engaged in the sugarcane trade. It was practised on the island of Cuba from the 16th century until it was abolished by Spanish ro ...

, the island's plantation

A plantation is an agricultural estate, generally centered on a plantation house, meant for farming that specializes in cash crops, usually mainly planted with a single crop, with perhaps ancillary areas for vegetables for eating and so on. The ...

economy based on sugar, and its geographical location predisposed it to Southern influence; its admission would greatly strengthen the position of Southern slaveholders, whose economic position was under threat from abolitionists

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The Britis ...

. Whereas immigration to Northern industrial centers had resulted in Northern control of the population-based House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entitles. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often c ...

, Southern politicians sought to maintain the balance of power in the Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

, where each state received equal representation. As slavery-free Western states were admitted, Southern politicians increasingly looked to Cuba as the next slave state

In the United States before 1865, a slave state was a state in which slavery and the internal or domestic slave trade were legal, while a free state was one in which they were not. Between 1812 and 1850, it was considered by the slave states ...

.Schoultz (1998), pp. 49–51, 56. If Cuba were admitted to the Union as a single state, the island would have sent two senators and up to nine representatives to Washington.Cuba's population in 1850 was 651,223 white and free persons of color and 322,519 enslaved people (). With slaves counting as three-fifths of a person for the purpose of Congressional representation, even though they had no votes and were not citizens, the population would have been considered 844,734 for determining Congressional apportionment. After the 1850 census, the ratio of congressman-to-constituent was 1:93,425, which would have yielded nine representatives for Cuba. Georgia had a similar population breakdown (524,503 free; 381,682 enslaved; total for apportionment 753,512) in the 1850 census and sent eight representatives to the 33rd United States Congress

The 33rd United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, consisting of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C. from March 4, 1853, ...

.

In the Democratic Party Democratic Party most often refers to:

*Democratic Party (United States)

Democratic Party and similar terms may also refer to:

Active parties Africa

*Botswana Democratic Party

*Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea

*Gabonese Democratic Party

*Demo ...

, the debate over the continued expansion of the United States centered on how quickly, rather than whether, to expand. Radical expansionists and the Young America movement

The Young America Movement was an American political, cultural and literary movement in the mid-19th century. Inspired by European reform movements of the 1830s (such as Junges Deutschland, Young Italy and Young Hegelians), the American group w ...

were quickly gaining traction by 1848, and a debate about whether to annex the Yucatán

Yucatán (, also , , ; yua, Yúukatan ), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Yucatán,; yua, link=no, Xóot' Noj Lu'umil Yúukatan. is one of the 31 states which comprise the political divisions of Mexico, federal entities of Mexico. I ...

portion of Mexico

Mexico (Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a country in the southern portion of North America. It is bordered to the north by the United States; to the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; to the southeast by Guatema ...

that year included significant discussion of Cuba. Even John C. Calhoun, described as a reluctant expansionist who strongly disagreed with intervention on the basis of the Monroe Doctrine

The Monroe Doctrine was a United States foreign policy position that opposed European colonialism in the Western Hemisphere. It held that any intervention in the political affairs of the Americas by foreign powers was a potentially hostile ac ...

, concurred that "it is indispensable to the safety of the United States that this island should not be in certain hands", likely referring to Britain.

In light of a Cuban uprising, President James K. Polk

James Knox Polk (November 2, 1795 – June 15, 1849) was the 11th president of the United States, serving from 1845 to 1849. He previously was the 13th speaker of the House of Representatives (1835–1839) and ninth governor of Tennessee (183 ...

refused solicitations from filibuster

A filibuster is a political procedure in which one or more members of a legislative body prolong debate on proposed legislation so as to delay or entirely prevent decision. It is sometimes referred to as "talking a bill to death" or "talking out ...

backer John L. O'Sullivan

John Louis O'Sullivan (November 15, 1813 – March 24, 1895) was an American columnist, editor, and diplomat who used the term "manifest destiny" in 1845 to promote the annexation of Texas and the Oregon Country to the United States. O'Sullivan ...

and stated his belief that any acquisition of the island must be an "amicable purchase."Brown (1980), pp. 21–28. Under orders from Polk, Secretary of State James Buchanan

James Buchanan Jr. ( ; April 23, 1791June 1, 1868) was an American lawyer, diplomat and politician who served as the 15th president of the United States from 1857 to 1861. He previously served as secretary of state from 1845 to 1849 and repr ...

prepared an offer of $100 million, but "sooner than see ubatransferred to any power, panish officialswould prefer seeing it sunk into the ocean." The Whig administrations of presidents Zachary Taylor

Zachary Taylor (November 24, 1784 – July 9, 1850) was an American military leader who served as the 12th president of the United States from 1849 until his death in 1850. Taylor was a career officer in the United States Army, rising to th ...

and Millard Fillmore

Millard Fillmore (January 7, 1800March 8, 1874) was the 13th president of the United States, serving from 1850 to 1853; he was the last to be a member of the Whig Party while in the White House. A former member of the U.S. House of Represen ...

did not pursue the matter and took a harsher stand against filibusters such as Venezuela

Venezuela (; ), officially the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela ( es, link=no, República Bolivariana de Venezuela), is a country on the northern coast of South America, consisting of a continental landmass and many islands and islets in th ...

n Narciso Lopez Narciso may refer to:

Given name

* Narciso Clavería y de Palacios, Spanish architect

* Narciso Clavería y Zaldúa, Governor General of the Philippines

* Narciso dos Santos, Brazilian former footballer

* Narciso Durán, Franciscan friar and missio ...

, with federal troops intercepting several expeditions bound for Cuba. When Franklin Pierce

Franklin Pierce (November 23, 1804October 8, 1869) was the 14th president of the United States, serving from 1853 to 1857. He was a northern Democrat who believed that the abolitionist movement was a fundamental threat to the nation's unity ...

took office in 1853, however, he was committed to Cuba's annexation.

The Pierce administration

At Pierce'spresidential inauguration A presidential inauguration is a ceremonial event centered on the formal transition of a new president into office, usually in democracies where this official has been elected. Frequently, this involves the swearing of an oath of office.

Examples o ...

, he stated, "The policy of my Administration will not be controlled by any timid forebodings of evil from expansion."Bemis (1965), pp. 309–320. While slavery was not the stated goal nor Cuba mentioned by name, the antebellum

Antebellum, Latin for "before war", may refer to:

United States history

* Antebellum South, the pre-American Civil War period in the Southern United States

** Antebellum Georgia

** Antebellum South Carolina

** Antebellum Virginia

* Antebellum ar ...

makeup of his party required the Northerner to appeal to Southern interests, so he favored the annexation of Cuba as a slave state. To this end, he appointed expansionists to diplomatic posts throughout Europe, notably sending Pierre Soulé, an outspoken proponent of Cuban annexation, as United States Minister to Spain. The Northerners in his cabinet were fellow doughface

The term doughface originally referred to an actual mask made of dough, but came to be used in a disparaging context for someone, especially a politician, who is perceived to be pliable and moldable. In the 1847 ''Webster's Dictionary'' ''doughfac ...

s (Northerners with Southern sympathies) such as Buchanan, who was made Minister to Great Britain after a failed bid for the presidency at the Democratic National Convention

The Democratic National Convention (DNC) is a series of presidential nominating conventions held every four years since 1832 by the United States Democratic Party. They have been administered by the Democratic National Committee since the 1852 ...

, and Secretary of State William L. Marcy

William Learned Marcy (December 12, 1786July 4, 1857) was an American lawyer, politician, and judge who served as U.S. Senator, Governor of New York, U.S. Secretary of War and U.S. Secretary of State. In the latter office, he negotiated the Gad ...

, whose appointment was also an attempt to placate the "Old Fogies." This was the term for the wing of the party that favored slow, cautious expansion.Potter (1967), pp. 184–188.

In March 1854, the steamer ''Black Warrior'' stopped at the Cuban port of Havana

Havana (; Spanish: ''La Habana'' ) is the capital and largest city of Cuba. The heart of the La Habana Province, Havana is the country's main port and commercial center.

on a regular trading route from New York City to Mobile, Alabama

Mobile ( , ) is a city and the county seat of Mobile County, Alabama, United States. The population within the city limits was 187,041 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, down from 195,111 at the 2010 United States census, 2010 cens ...

. When it failed to provide a cargo manifest, Cuban officials seized the ship, its cargo, and its crew. The so-called ''Black Warrior'' Affair was viewed by Congress as a violation of American rights; a hollow ultimatum issued by Soulé to the Spanish to return the ship served only to strain relations, and he was barred from discussing Cuba's acquisition for nearly a year. While the matter was resolved peacefully, it fueled the flames of Southern expansionism.

Meanwhile, the doctrine of manifest destiny

Manifest destiny was a cultural belief in the 19th century in the United States, 19th-century United States that American settlers were destined to expand across North America.

There were three basic tenets to the concept:

* The special vir ...

had become increasingly sectionalized as the decade progressed. While there were still Northerners who believed the United States should dominate the continent, most were opposed to Cuba's annexation, particularly as a slave state. Southern-backed filibusters, including Narciso López

Narciso López (November 2, 1797, Caracas – September 1, 1851, Havana) was a Venezuelan-born adventurer and Spanish Army general who is best known for his expeditions aimed at liberating Cuba from Spanish rule in the 1850s. His troops carri ...

, had failed repeatedly since 1849 to 1851 to overthrow the colonial government despite considerable support among the Cuban people for independence,The actions of the filibusters violated U.S. neutrality laws, but Pierce's administration did not prosecute them as heavily as the Whig administrations that preceded him. Both expansionists and advocates of Cuban independence wanted the island to leave Spanish rule. López believed the sectional competition in the U.S. would prevent it from annexing Cuba and clear the way for Cuban independence. See Bemis (1965), pp. 313–317. For more information, see Brown (1980), Part I: "The Pearl of the Antilles". and a series of reforms on the island made Southerners apprehensive that slavery would be abolished. They believed that Cuba would be "Africanized," as the majority of the population were slaves, and they had seen the Republic of Haiti

Haiti (; ht, Ayiti ; French: ), officially the Republic of Haiti (); ) and formerly known as Hayti, is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and so ...

established by former slaves. The notion of a pro-slavery invasion by the U.S. was rejected in light of the controversy over the Kansas–Nebraska Act

The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 () was a territorial organic act that created the territories of Kansas and Nebraska. It was drafted by Democratic Senator Stephen A. Douglas, passed by the 33rd United States Congress, and signed into law by ...

. During internal discussions, supporters of gaining Cuba decided that a purchase or intervention in the name of national security

National security, or national defence, is the security and defence of a sovereign state, including its citizens, economy, and institutions, which is regarded as a duty of government. Originally conceived as protection against military atta ...

was the most acceptable method of acquisition.

Writing the Manifesto

Marcy suggested Soulé confer with Buchanan and

Marcy suggested Soulé confer with Buchanan and John Y. Mason

John Young Mason (April 18, 1799October 3, 1859) was a United States representative from Virginia, the 16th and 18th United States Secretary of the Navy, the 18th Attorney General of the United States, United States Ambassador to France, United ...

, Minister to France, on U.S. policy toward Cuba. He had previously written to Soulé that, if Cuba's purchase could not be negotiated, "you will then direct your effort to the next desirable object, which is to detach that island from the Spanish dominion and from all dependence on any European power"—words Soulé may have adapted to fit his own agenda.Potter (1967), pp. 188–189; Schoultz (1998), pp. 49–51. Authors David Potter and Lars Schoultz both note the considerable ambiguity in Marcy's cryptic words, and Samuel Bemis suggests he may have referred to Cuban independence, but acknowledges it is impossible to know Marcy's true intent. In any case, Marcy had also written in June that the administration had abandoned thoughts of declaring war over Cuba. But Robert May writes, "the instructions for the conference had been so vague, and so many of Marcy's letters to Soulé since the ''Black Warrior'' incident had been bellicose, that the ministers misread the administration's intent."

After a minor disagreement about their meeting site, the three American diplomats met in Ostend

Ostend ( nl, Oostende, ; french: link=no, Ostende ; german: link=no, Ostende ; vls, Ostende) is a coastal city and municipality, located in the province of West Flanders in the Flemish Region of Belgium. It comprises the boroughs of Mariakerk ...

, Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to th ...

from October 9–11, 1854, then adjourned to Aachen

Aachen ( ; ; Aachen dialect: ''Oche'' ; French and traditional English: Aix-la-Chapelle; or ''Aquisgranum''; nl, Aken ; Polish: Akwizgran) is, with around 249,000 inhabitants, the 13th-largest city in North Rhine-Westphalia, and the 28th- ...

, Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an em ...

, for a week to prepare a report of the proceedings. The resulting dispatch, which would come to be known as the Ostend Manifesto, declared that "Cuba is as necessary to the North American republic as any of its present members, and that it belongs naturally to that great family of states of which the Union is the Providential Nursery".Potter (1967), p. 190.

Prominent among the reasons for annexation outlined in the manifesto were fears of a possible slave revolt in Cuba parallel to the Haitian Revolution (1791–1804) in the absence of U.S. intervention. The Manifesto urged against inaction on the Cuban question, warning,

We should, however, be recreant to our duty, be unworthy of our gallant forefathers, and commit base treason against our posterity, should we permit Cuba to be Africanized and become a second St. Domingo (Haiti), with all its attendant horrors to the white race, and suffer the flames to extend to our own neighboring shores, seriously to endanger or actually to consume the fair fabric of our Union.Racial fears, largely spread by Spain, raised tension and anxiety in the U.S. over a potential black uprising on the island that could "spread like wildfire" to the southern U.S. The Manifesto stated that the U.S. would be "justified in wresting" Cuba from Spain if the colonial power refused to sell it. Soulé was a former U.S. Senator from Louisiana and member of the Young America movement, who sought a realization of American influence in the Caribbean and Central America. He is credited as the primary architect of the policy expressed in the Ostend Manifesto. The experienced and cautious Buchanan is believed to have written the document and moderated Soulé's aggressive tone. Soulé highly favored expansion of Southern influence outside the current Union of States. His belief in Manifest Destiny led him to prophesy "absorption of the entire continent and its island appendages" by the U.S. Mason's Virginian roots predisposed him to the sentiments expressed in the document, but he later regretted his actions.Rhodes (1893), p. 40. Buchanan's exact motivations remain unclear despite his expansionist tendencies, but it has been suggested that he was seduced by visions of the presidency, which he would go on to win in 1856. One historian concluded in 1893, "When we take into account the characteristics of the three men we can hardly resist the conclusion that Soulé, as he afterwards intimated, twisted his colleagues round his finger." To Marcy's chagrin, the flamboyant Soulé made no secret of the meetings. The press in both Europe and the U.S. were well aware of the proceedings if not their outcome, but were preoccupied with wars and midterm elections.Rhodes (1893), p. 38. In the latter case, the Democratic Party became a minority in the

United States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is bicameral, composed of a lower body, the House of Representatives, and an upper body, the Senate. It meets in the U.S. Capitol in Washing ...

, and editorials continued to chide the Pierce administration for its secrecy. At least one newspaper, the ''New York Herald

The ''New York Herald'' was a large-distribution newspaper based in New York City that existed between 1835 and 1924. At that point it was acquired by its smaller rival the ''New-York Tribune'' to form the '' New York Herald Tribune''.

His ...

,'' published what Brown calls "reports that came so close to the truth of the decisions at Ostend that the President feared they were based on leaks, as indeed they may have been". Pierce feared the political repercussions of confirming such rumors, and he did not acknowledge them in his State of the Union

The State of the Union Address (sometimes abbreviated to SOTU) is an annual message delivered by the president of the United States to a joint session of the United States Congress near the beginning of each calendar year on the current conditio ...

address at the end of 1854. The administration's opponents in the House of Representatives called for the document's release, and it was published in full four months after being written.

Fallout

When the document was published, Northerners were outraged by what they considered a Southern attempt to extend slavery. American free-soilers, recently angered by the strengthened

When the document was published, Northerners were outraged by what they considered a Southern attempt to extend slavery. American free-soilers, recently angered by the strengthened Fugitive Slave Law

The fugitive slave laws were laws passed by the United States Congress in 1793 and 1850 to provide for the return of enslaved people who escaped from one state into another state or territory. The idea of the fugitive slave law was derived from ...

(passed as part of the Compromise of 1850

The Compromise of 1850 was a package of five separate bills passed by the United States Congress in September 1850 that defused a political confrontation between slave and free states on the status of territories acquired in the Mexican–Ame ...

and requiring officials of free states to cooperate in the return of slaves), decried as unconstitutional what Horace Greeley

Horace Greeley (February 3, 1811 – November 29, 1872) was an American newspaper editor and publisher who was the founder and newspaper editor, editor of the ''New-York Tribune''. Long active in politics, he served briefly as a congressm ...

of the ''New York Tribune

The ''New-York Tribune'' was an American newspaper founded in 1841 by editor Horace Greeley. It bore the moniker ''New-York Daily Tribune'' from 1842 to 1866 before returning to its original name. From the 1840s through the 1860s it was the domi ...

'' labeled "The Manifesto of the Brigands." During the period of Bleeding Kansas

Bleeding Kansas, Bloody Kansas, or the Border War was a series of violent civil confrontations in Kansas Territory, and to a lesser extent in western Missouri, between 1854 and 1859. It emerged from a political and ideological debate over the ...

, as anti- and pro-slavery supporters fought for control of the state, the Ostend Manifesto served as a rallying cry for the opponents of the Slave Power. The incident was one of many factors that gave rise to the Republican Party, and the manifesto was criticized in the Party's first platform in 1856 as following a "highwayman

A highwayman was a robber who stole from travellers. This type of thief usually travelled and robbed by horse as compared to a footpad who travelled and robbed on foot; mounted highwaymen were widely considered to be socially superior to footp ...

's" philosophy of "might makes right." But, the movement to annex Cuba did not fully end until after the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

.

The Pierce Administration was irreparably damaged by the incident. Pierce had been highly sympathetic to the Southern cause, and the controversy over the Ostend Manifesto contributed to the splintering of the Democratic Party. Internationally, it was seen as a threat to Spain and to imperial power across Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

. It was quickly denounced by national governments in Madrid

Madrid ( , ) is the capital and most populous city of Spain. The city has almost 3.4 million inhabitants and a metropolitan area population of approximately 6.7 million. It is the second-largest city in the European Union (EU), and ...

, London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

, and Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

. To preserve what favorable relations the administration had left, Soulé was ordered to cease discussion of Cuba; he promptly resigned. The backlash from the Ostend Manifesto caused Pierce to abandon expansionist plans. It has been described as part of a series of "gratuitous conflicts ... that cost more than they were worth" for Southern interests intent on maintaining the institution of slavery.

James Buchanan

James Buchanan Jr. ( ; April 23, 1791June 1, 1868) was an American lawyer, diplomat and politician who served as the 15th president of the United States from 1857 to 1861. He previously served as secretary of state from 1845 to 1849 and repr ...

was easily elected President in 1856. Although he remained committed to Cuban annexation, he was hindered by popular opposition and the growing sectional conflict. It was not until thirty years after the Civil War that the so-called Cuban Question again came to national prominence.May (1973), pp. 163–189.

See also

*Annexation of Santo Domingo

The annexation of Santo Domingo was an attempted treaty during the later Reconstruction Era, initiated by United States President Ulysses S. Grant in 1869, to annex "Santo Domingo" (as the Dominican Republic was commonly known) as a United States ...

* Cuba–United States relations

Cuba and the United States restored diplomacy, diplomatic relations on July 20, 2015. Relations had been severed in 1961 during the Cold War. U.S. diplomatic representation in Cuba is handled by the Embassy of the United States, Havana, United ...

* Golden Circle (proposed country)

* Spain–United States relations

The troubled history of Spanish–American relations has been seen as one of "love and hate". The groundwork was laid by the colonization of parts of the Americas by Spain before 1700. The Spaniards were the first Europeans to establish a perma ...

References

Footnotes Citations Sources * * * * * Langley, Lester D. "Slavery, Reform, and American Policy in Cuba, 1823-1878." ''Revista de Historia de América'' (1968): 71-84. . * * * * * * Sexton, Jay. "Toward a synthesis of foreign relations in the Civil War era, 1848–77." ''American Nineteenth Century History'' (2004) 5#3 pp. 50–73. * * Webster, Sidney. "Mr. Marcy, the Cuban Question and the Ostend Manifesto." ''Political Science Quarterly'' (1893) 8#1 pp: 1–32. .External links

* * {{Featured article 1854 in Belgium 1854 in the United States Cuba–United States relations History of the Caribbean History of United States expansionism Imperialism Ostend Slavery in the United States 1854 documents History of Cuba Proposed states and territories of the United States Expansion of slavery in the United States Origins of the American Civil War American political manifestos