Oren Cheney on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Oren Burbank Cheney (December 10, 1816 – December 22, 1903) was an American politician, minister, and statesman who was a key figure in the abolitionist movement in the United States during the later 19th century. Along with textile tycoon Benjamin Bates, he founded the first

Edmund S. Muskie Archives & Special Collections Library, Bates College, accessed 31 May 2012 Moses Cheney held important positions in the church and served many times in the state legislature. Cheney's mother had a significant impact on his religious views, he was often quoted as saying, "my mother used this bible to worship all that is holy, I shall cease when I arise to the heavenly skies that welcome me," later in his life as president of Bates College. His household was deeply religious and he credited his "Godly upbringing" with forming his philosophical ideologies and personal convictions. Early in his life he was known as a "humble, patient, and soft-spoken boy." When he was eight years old, he was enrolled in Sunday School in Holderness, and his parents were criticized for sending him to a newly founded school, as it was started by a cashier who found God later in life and was not considered "God's child from birth." He began to work at age nine at the school and spent his allowance on honey and While going through Parsonsfield, he was surrounded by racial segregation and religious oppression and later in life, sought an educational institution that catered to everyone that required it, that would take the form of a rigorous, and academically prominent school. He was interested in the

While going through Parsonsfield, he was surrounded by racial segregation and religious oppression and later in life, sought an educational institution that catered to everyone that required it, that would take the form of a rigorous, and academically prominent school. He was interested in the

Cheney's political efficacy started at a young age, but his first official political declaration was to be his first vote in which he cast a vote for James G. Briney, a member of the Liberty Party. Briney lost the elections in the

Cheney's political efficacy started at a young age, but his first official political declaration was to be his first vote in which he cast a vote for James G. Briney, a member of the Liberty Party. Briney lost the elections in the

Emeline Cheney, ''The Story of the Life and Work of Oren B. Cheney''

' (Boston: Morning Star Publishing, 1907) '' *Timothy Larson

''Faith by Their Works: The Progressive Tradition at Bates College from 1855 to 1877''

'' Thesis at Muskie Archives,'' Bates College, 2005. *Multiple authors

New Hampshire State Magazine: Oren Burbank Cheney

''New Hampshire State Magazine''. 2010.

Edmund S. Muskie Archives & Special Collections Library, Bates College {{DEFAULTSORT:Cheney, Oren B. 1816 births 1903 deaths 19th-century Baptist ministers from the United States Activists from New Hampshire American temperance activists Baptist abolitionists Brown University alumni Dartmouth College alumni Free Will Baptists Maine Free Soilers Republican Party members of the Maine House of Representatives People from Ashland, New Hampshire People from Holderness, New Hampshire People from Lebanon, Maine Politicians from Lewiston, Maine Presidents of Bates College Underground Railroad people University and college founders

coeducational

Mixed-sex education, also known as mixed-gender education, co-education, or coeducation (abbreviated to co-ed or coed), is a system of education where males and females are educated together. Whereas single-sex education was more common up to t ...

university in New England (the Bates College

Bates College () is a private liberal arts college in Lewiston, Maine. Anchored by the Historic Quad, the campus of Bates totals with a small urban campus which includes 33 Victorian Houses as some of the dormitories. It maintains of nature p ...

) which is widely considered his ''magnum opus

A masterpiece, ''magnum opus'' (), or ''chef-d’œuvre'' (; ; ) in modern use is a creation that has been given much critical praise, especially one that is considered the greatest work of a person's career or a work of outstanding creativity, ...

.'' Cheney is one of the most extensively covered subjects of Neoabolitionism, for his public denouncement of slavery, involuntary servitude

Involuntary servitude or involuntary slavery is a legal and constitutional term for a person laboring against that person's will to benefit another, under some form of coercion, to which it may constitute slavery. While laboring to benefit another ...

, and advocation for fair and equal representation, egalitarianism

Egalitarianism (), or equalitarianism, is a school of thought within political philosophy that builds from the concept of social equality, prioritizing it for all people. Egalitarian doctrines are generally characterized by the idea that all hu ...

, and personal sovereignty.

Cheney's main social ideology was that of egalitarianism

Egalitarianism (), or equalitarianism, is a school of thought within political philosophy that builds from the concept of social equality, prioritizing it for all people. Egalitarian doctrines are generally characterized by the idea that all hu ...

; he personally voiced his disdain for racial inequality

Social inequality occurs when resources in a given society are distributed unevenly, typically through norms of allocation, that engender specific patterns along lines of socially defined categories of persons. It posses and creates gender c ...

, social elitism, and socioeconomic depravation regularly, in controversial speeches and articles. He was ordained

Ordination is the process by which individuals are consecrated, that is, set apart and elevated from the laity class to the clergy, who are thus then authorized (usually by the denominational hierarchy composed of other clergy) to perform va ...

a minister in his early twenties, became the headmaster at Parsonsfield, Maine

Parsonsfield is a town in York County, Maine, United States. The population was just 1,791 at the 2020 census. Parsonsfield includes the villages of Kezar Falls, Parsonsfield, and North, East and South Parsonsfield. It is part of the Portland& ...

, and illegally harbored and transferred slaves to safety during the 1840s in New Hampshire–an action punishable with a decade's jail time by the federal Fugitive Slave acts. His religious community work garnered him widespread support, culminating in his nomination for a seat in the Maine House of Representatives

The Maine House of Representatives is the lower house of the Maine Legislature. The House consists of 151 voting members and three nonvoting members. The voting members represent an equal number of districts across the state and are elected via p ...

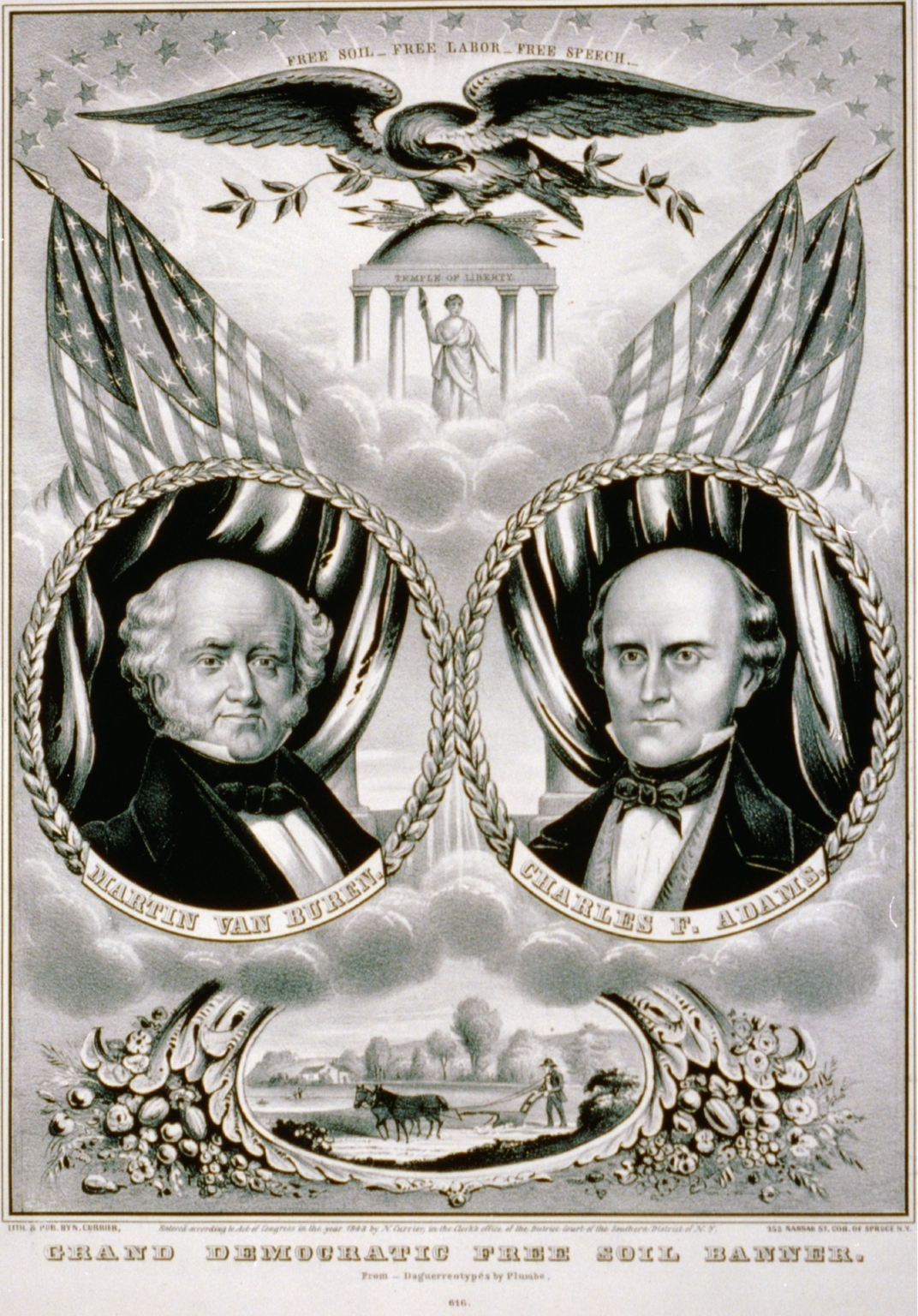

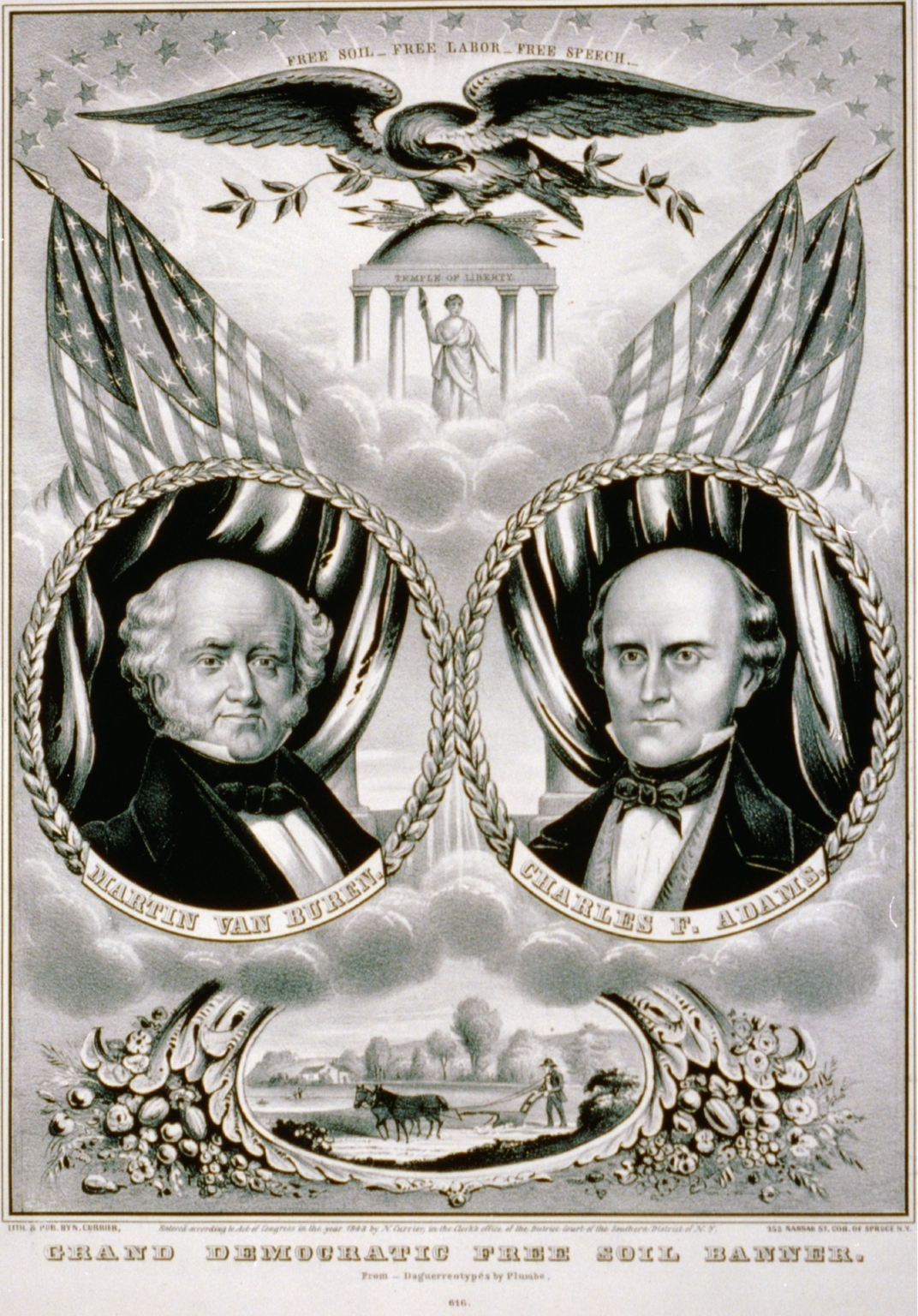

without his knowledge. Having been told he was nominated and elected on his way to his induction ceremony, Cheney would go on to be an able Free Soil

The Free Soil Party was a short-lived coalition political party in the United States active from 1848 to 1854, when it merged into the Republican Party. The party was largely focused on the single issue of opposing the expansion of slavery into ...

legislator. His first bills drafted and passed supported state prohibition, advocated for temperance

Temperance may refer to:

Moderation

*Temperance movement, movement to reduce the amount of alcohol consumed

*Temperance (virtue), habitual moderation in the indulgence of a natural appetite or passion

Culture

*Temperance (group), Canadian danc ...

, regulated liquor traffic (notably the passage of the Maine Liquor Law), and provided the funds for his first school–the Lebanon Academy in Lebanon, Maine

Lebanon is a town in York County, Maine, United States. The population was 6,469 at the 2020 census. Lebanon includes the villages of Center Lebanon, West Lebanon, North Lebanon, South Lebanon and East Lebanon. It is the westernmost town in Ma ...

. He gave many abolitionist speeches to the legislature, which produced mixed reactions and death threat

A death threat is a threat, often made anonymously, by one person or a group of people to kill another person or group of people. These threats are often designed to intimidate victims in order to manipulate their behaviour, in which case a deat ...

s; historians have occasionally noted him as "completely and utterly careless with his life."

He was elected as the only delegate to attend the 1852 Free Soil Party Convention in Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh ( ) is a city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, Allegheny County. It is the most populous city in both Allegheny County and Wester ...

from Maine, where he famously advocated for anti-slavery

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The Britis ...

, and physically threatened the owner of a local tavern for refusing to serve Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, February 1817 or 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. After escaping from slavery in Maryland, he became ...

, a noted abolitionist and black member of the party. After his political career, he continued to publish anti-slavery pieces in his newspaper, and establish the Maine State Seminary, which would later be named "Bates College." He governed as the first President of Bates College for nearly four decades–from 1855 to 1894–creating its liberal arts curriculum, hiring faculty, and choosing its campus; during this time he adopted the moniker

A nickname is a substitute for the proper name of a familiar person, place or thing. Commonly used to express affection, a form of endearment, and sometimes amusement, it can also be used to express defamation of character. As a concept, it is ...

O.B. Cheney.

Early life and family

Birth and youth

Oren Burbank Cheney was born inHolderness, New Hampshire

Holderness is a town in Grafton County, New Hampshire, United States. The population was 2,004 at the 2020 census. An agricultural and resort area, Holderness is home to the Squam Lakes Natural Science Center and is located on Squam Lake. Holderne ...

, on December 10, 1816. He was born to Abigail and Moses Cheney, who were noted abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

s. Cheney's brother, Person

A person ( : people) is a being that has certain capacities or attributes such as reason, morality, consciousness or self-consciousness, and being a part of a culturally established form of social relations such as kinship, ownership of property, ...

, would go on to become a prominent politician in New Hampshire. His father was a paper manufacturer and also a conductor on the Underground Railroad

The Underground Railroad was a network of clandestine routes and safe houses established in the United States during the early- to mid-19th century. It was used by enslaved African Americans primarily to escape into free states and Canada. T ...

."Guide to the Office of the President, Oren Burbank Cheney records, 1857–1902"Edmund S. Muskie Archives & Special Collections Library, Bates College, accessed 31 May 2012 Moses Cheney held important positions in the church and served many times in the state legislature. Cheney's mother had a significant impact on his religious views, he was often quoted as saying, "my mother used this bible to worship all that is holy, I shall cease when I arise to the heavenly skies that welcome me," later in his life as president of Bates College. His household was deeply religious and he credited his "Godly upbringing" with forming his philosophical ideologies and personal convictions. Early in his life he was known as a "humble, patient, and soft-spoken boy." When he was eight years old, he was enrolled in Sunday School in Holderness, and his parents were criticized for sending him to a newly founded school, as it was started by a cashier who found God later in life and was not considered "God's child from birth." He began to work at age nine at the school and spent his allowance on honey and

gingerbread

Gingerbread refers to a broad category of baked goods, typically flavored with ginger, cloves, nutmeg, and cinnamon and sweetened with honey, sugar, or molasses. Gingerbread foods vary, ranging from a moist loaf cake to forms nearly as crisp as ...

, considered luxuries at the time. His rebellious side was exposed on numerous occasions, most notably when a Free Will Baptist came to the family's house , to recite lessons, Cheney jumped and stabbed the windowsill with his jack-knife scaring everyone in the room, which formed an ongoing reputation of the young boy. Soon after Sunday School, Cheney began to work at his father's paper mill, tending to the engines, and housekeeping, at night. The paper he would , 277pxform would go on to print the very first copy of The Morning Star, the single most important newspaper of Free Will Baptist

Free Will Baptists are a group of General Baptist denominations of Christianity that teach free grace, free salvation and free will. The movement can be traced back to the 1600s with the development of General Baptism in England. Its formal est ...

s. At age thirteen, he attended the New Hampton Academical and Theological Institute in 1829–30, which was five miles away, his mother's decision to send him so far way was partly based on Cheney's unhealthy interest with knives; he cut the end of his thumb while husking corn. Cheney's demanding personality was developed quickly as he taught at elementary schools during his time at New Hampton. A notable example of this was when a drunken father stumbled into the school yard accusing a young Cheney of disciplining his child in unfair ways, Cheney drew his measuring stick and quieted the man. While at the New Hampton Institute, he was exposed to Free Will Baptism at personal level through his studies, and peers, and soon after returned to his father's mill. After the mill was sustainable through the hiring of other local school boys, Cheney was sent to Parsonsfield Seminary

Parsonsfield Seminary, which operated from 1832 to 1949, was a well-known Free Will Baptist

Free Will Baptists are a group of General Baptist denominations of Christianity that teach free grace, free salvation and free will. The movement can ...

, which was 14 miles away; a three-day trip.

While going through Parsonsfield, he was surrounded by racial segregation and religious oppression and later in life, sought an educational institution that catered to everyone that required it, that would take the form of a rigorous, and academically prominent school. He was interested in the

While going through Parsonsfield, he was surrounded by racial segregation and religious oppression and later in life, sought an educational institution that catered to everyone that required it, that would take the form of a rigorous, and academically prominent school. He was interested in the temperance movement

The temperance movement is a social movement promoting temperance or complete abstinence from consumption of alcoholic beverages. Participants in the movement typically criticize alcohol intoxication or promote teetotalism, and its leaders emph ...

early on and founded his school's temperance society.

Education and ministership

In 1836, Cheney enrolled inBrown University

Brown University is a private research university in Providence, Rhode Island. Brown is the seventh-oldest institution of higher education in the United States, founded in 1764 as the College in the English Colony of Rhode Island and Providenc ...

, but while in Providence witnessed mobs violently treating people with the same religious and political beliefs as he had. Although he was excited by the commotion involved, he decided he was better off studying at a school that offered him a higher degree of physical safety. He transferred to Dartmouth College

Dartmouth College (; ) is a private research university in Hanover, New Hampshire. Established in 1769 by Eleazar Wheelock, it is one of the nine colonial colleges chartered before the American Revolution. Although founded to educate Native A ...

, due to their significant tolerance of abolitionism. His choice was also heavily influenced by the Dartmouth College v. Woodward

''Trustees of Dartmouth College v. Woodward'', 17 U.S. (4 Wheat.) 518 (1819), was a List of landmark court decisions in the United States, landmark decision in United States corporate law from the Supreme Court of the United States, United States ...

case which would later become a guiding case in the foundation of Bates College. Soon after being admitted, he accepted a teaching position in Canaan, New Hampshire

Canaan is a town in Grafton County, New Hampshire, United States. The population was 3,794 at the 2020 census. It is the location of Mascoma State Forest. Canaan is home to the Cardigan Mountain School, the town's largest employer.

The main v ...

but his goals were hindered before he could seriously impact the communities' politics. During the night, the townspeople rode ox with the building strapped to wooden rollers into the swamp and left it there unattended. Cheney enrolled in Dartmouth in 1836, and founded a missionary organization that helped in the education of Indians. He felt a deep connection with the college, and was reported meditating near the grave of Eleazar Wheelock

Eleazar Wheelock (April 22, 1711 – April 24, 1779) was an American Congregational minister, orator, and educator in Lebanon, Connecticut, for 35 years before founding Dartmouth College in New Hampshire. He had tutored Samson Occom, a Mohe ...

, the founder of the college. While at the college, he participated in numerous outings with classmates to anti-slavery meetings in Hanover. He described the events as:A crowd of men and boys with drums and horns for the purpose of making a disturbance... Boys were allowed to vote at the age of twenty-one, so they voted in the interest of theIn May 1836, he walked back to his old home inanti-slavery movement Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people. The British ...... The waving of handkerchiefs by women young and old, and the cheers from the crowd showed how great a victory we had over the pro-slavery spirit that was thought to have crushed us.

Ashland, New Hampshire

Ashland is a town in Grafton County, New Hampshire, United States. The population was 1,938 at the 2020 census, down from 2,076 at the 2010 census.United States Census BureauAmerican FactFinder 2010 Census figures. Retrieved March 23, 2011. Locat ...

, a trek of 40 miles, walking due to financial restrictions, to be baptized. On his way back to Dartmouth, he began to devote himself to teaching and academia, supplementing his income by pursuing teaching jobs around New Hampshire. He graduated from the university in 1839. He returned to Parsonsfield, a stop on the Underground Railroad

The Underground Railroad was a network of clandestine routes and safe houses established in the United States during the early- to mid-19th century. It was used by enslaved African Americans primarily to escape into free states and Canada. T ...

, for several years in the 1840s as an alumnus and went on to lead the school as its head master

A head master, head instructor, bureaucrat, headmistress, head, chancellor, principal or school director (sometimes another title is used) is the staff member of a school with the greatest responsibility for the management of the school. In som ...

. He founded the Lebanon Academy in Lebanon, Maine

Lebanon is a town in York County, Maine, United States. The population was 6,469 at the 2020 census. Lebanon includes the villages of Center Lebanon, West Lebanon, North Lebanon, South Lebanon and East Lebanon. It is the westernmost town in Ma ...

in 1850. During this time, he worked for the Underground Railroad

The Underground Railroad was a network of clandestine routes and safe houses established in the United States during the early- to mid-19th century. It was used by enslaved African Americans primarily to escape into free states and Canada. T ...

, and along with his second brother, Elias Hutchins, illegally harbored and transferred slaves from Windy Row, New Hampshire to Hancock Hancock may refer to:

Places in the United States

* Hancock, Iowa

* Hancock, Maine

* Hancock, Maryland

* Hancock, Massachusetts

* Hancock, Michigan

* Hancock, Minnesota

* Hancock, Missouri

* Hancock, New Hampshire

** Hancock (CDP), New Hampshir ...

. This was, under the federal Fugitive Slave acts, highly illegal. His reputation earned him a visit from noted abolitionist, Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, February 1817 or 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. After escaping from slavery in Maryland, he became ...

, who stayed at his home during the 1840 New England Anti-Slavery Society Convention. It was reported that during this time four slave bounty hunters went missing in Hancock.

On January 30, 1840, he married Caroline A. Rundlett and they had one child, Horace Rundlett Cheney. He later attended the Free Will Baptist Bible School in Whitestown, New York

Whitestown is a town in Oneida County, New York, United States. The population was 18,667 at the 2010 census. The name is derived from Judge Hugh White, an early settler. The town is immediately west of Utica and the New York State Thruway (Inte ...

to study theology but had to leave following his wife's death in June 1846. In 1844, Cheney was ordained as a Free Will Baptist

Free Will Baptists are a group of General Baptist denominations of Christianity that teach free grace, free salvation and free will. The movement can be traced back to the 1600s with the development of General Baptism in England. Its formal est ...

minister, but he left the ministership after some years due to their position on slavery. In 1847, the widower Cheney married Nancy S. Perkins. They had two children, Caroline and Emeline. Nancy died in 1886. In July 1892, Cheney married Emeline S. Burlingame, a widow, who survived him. His only son, Horace Cheney, was admitted to Bowdoin College

Bowdoin College ( ) is a private liberal arts college in Brunswick, Maine. When Bowdoin was chartered in 1794, Maine was still a part of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. The college offers 34 majors and 36 minors, as well as several joint eng ...

in Brunswick as one of the 100 students allowed to study at the university during the early 19th century.

Political career

Cheney's political efficacy started at a young age, but his first official political declaration was to be his first vote in which he cast a vote for James G. Briney, a member of the Liberty Party. Briney lost the elections in the

Cheney's political efficacy started at a young age, but his first official political declaration was to be his first vote in which he cast a vote for James G. Briney, a member of the Liberty Party. Briney lost the elections in the Maine House of Representatives

The Maine House of Representatives is the lower house of the Maine Legislature. The House consists of 151 voting members and three nonvoting members. The voting members represent an equal number of districts across the state and are elected via p ...

, however, one year later, Cheney was nominated without anyone telling him he was nominated. He won the elections in early December 1851, and while on trip to speak with community leaders in Augusta, aids told him that he had been nominated and elected to the legislature. They took a detour and he was inducted as a Member of the Maine House of Representatives representing the 86th district of Augusta, Maine later that day. His early tenure in the legislature as a Free Soil

The Free Soil Party was a short-lived coalition political party in the United States active from 1848 to 1854, when it merged into the Republican Party. The party was largely focused on the single issue of opposing the expansion of slavery into ...

politician was tacked to state prohibition

Prohibition is the act or practice of forbidding something by law; more particularly the term refers to the banning of the manufacture, storage (whether in barrels or in bottles), transportation, sale, possession, and consumption of alcoholic ...

, he first bills drafted and passed limited the outlawed the sale of alcohol in Maine, with the Maine Liquor Law, and regulated the consumption of it on a district-by-district basis. Cheney also went on to begin to make speeches in the legislature on the principles of abolitionism and egalitarianism to mixed reception. When a congressman asked him to stop giving speeches on the abolition of slavery and the prohibition of alcohol, Cheney replied: "a pile of gold as high as the mountains would not tempt me to stop speaking upon those topic."

During his tenure as a state respective he acquired his fathers Free Will Baptist

Free Will Baptists are a group of General Baptist denominations of Christianity that teach free grace, free salvation and free will. The movement can be traced back to the 1600s with the development of General Baptism in England. Its formal est ...

newspaper, ''The Morning Star''. He used the newspaper as a medium for him to print his speeches in the legislature and to write articles supporting abolitionism. His assumption of the newspaper drew attention of a past acquaintance, Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, February 1817 or 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. After escaping from slavery in Maryland, he became ...

. Cheney asserted in his first printing as owner: We shall speak against slavery, as we have hitherto done. We can find no language that has the power to express the hatred we have towards so vile and so wicked an institution-We hate it-we abhor, we lather it-wedetest it and despise it as a giant sin against God.His later career in the Maine House of Representatives, secured $2,000 for his academy in

Lebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to the north and east and Israel to the south, while Cyprus li ...

, regulated liquor traffic, and advocated for temperance

Temperance may refer to:

Moderation

*Temperance movement, movement to reduce the amount of alcohol consumed

*Temperance (virtue), habitual moderation in the indulgence of a natural appetite or passion

Culture

*Temperance (group), Canadian danc ...

. He left his academy shortly after founding it in strong financial conduction and under the care of the local community.

Shortly, before the conclusion his term, he was elected as the delegate to the 1852 Free Soil Party Convention in Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh ( ) is a city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, Allegheny County. It is the most populous city in both Allegheny County and Wester ...

, Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

. During the scheduled speeches at the convention he drew widespread controversy for his speech regarding complete and absolute abolitionism. At the time, the Free Soil Party only believed in anti-slavery not abolitionism. On the final night of the convention the delegates were invited to a local tavern of the State House where they were free to dine with each other. Upon entering the establishment, Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, February 1817 or 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. After escaping from slavery in Maryland, he became ...

, a fellow delegate was stopped at the door and Cheney was told that "the nigger must not come in." After an intense yelling match between members of the delegation and the owner, Cheney stepped forward and physically the threatened the owner with a beating and told him that if Douglass was not seated first, before anyone else, the entire delegation was to eat elsewhere. With fear of safety and loss of business, the owner conceded and seated Douglass. The event sent a powerful message to the convention, but Cheney's mental stability was rumored to be faulty by members of both sides.

One year later in 1853, he was assigned as a delegate to Free Will Baptist General Conference, and participated in numerous talks that helped establish a political link to the movement. He choose not to seek another term in the Maine Legislature due to his increasingly ineffective legislation giving blacks quasi-rights failed. After stepping down from political office on November 3, 1854, he continued his work with ''The Morning Star''. One the evening of his retirement from political life, he printed one of his more famous lines on the cover of the newspaper:Live and take comfort. Thou hast left behind powers that will work for thee, air, earth, and skies. Theres not breathing of a common mind that will forget thee. Thou has great allies.He switched his

political affiliation

A political party is an organization that coordinates candidates to compete in a particular country's elections. It is common for the members of a party to hold similar ideas about politics, and parties may promote specific ideological or pol ...

to the Republican Party, due to their liberal and democratic stance on slavery and personal sovereignty. He spent the rest of his life developing the party within Maine.

Maine State Seminary

After news spread to Cheney that his old secondary school,Parsonsfield Seminary

Parsonsfield Seminary, which operated from 1832 to 1949, was a well-known Free Will Baptist

Free Will Baptists are a group of General Baptist denominations of Christianity that teach free grace, free salvation and free will. The movement can ...

, mysteriously burned down in 1853, he began to plan the construction of a new school. Opponents of his political work and abolitionism in general were rumored to be the arson

Arson is the crime of willfully and deliberately setting fire to or charring property. Although the act of arson typically involves buildings, the term can also refer to the intentional burning of other things, such as motor vehicles, wat ...

ists behind the destruction of Parsonsfield. Cheney wrote the details of the event in a diary: "the bell tower flickered in flames while the children ran from its pillar-brick walls.." The fire was believed to have killed three school children, and two fugitive slaves

In the United States, fugitive slaves or runaway slaves were terms used in the 18th and 19th century to describe people who fled slavery. The term also refers to the federal Fugitive Slave Acts of 1793 and 1850. Such people are also called free ...

, leading to a brief and unsuccessful investigation.

Cheney went back to the Maine State legislature and used his political sway to bypass certain legal proceedings and begin the incorporation of a new school. He began the process by meeting with the religious, political, and social elites of Maine in Topsham to discuss the formation of a new seminary. His idea was met with positive reception and the act of incorporation was drafted. Of the one required, twenty-four petitions were submitted to the Maine State Legislature

The Maine Legislature is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Maine. It is a bicameral body composed of the lower house Maine House of Representatives and the upper house Maine Senate. The Legislature convenes at the State House in Aug ...

. After minimal delay, the charter was approved and appropriated with $15,000 for its conception. With the school being established Cheney wrote to Massachusetts Congressman and one of the most established anti-slavery radicals in the country, Charles Sumner

Charles Sumner (January 6, 1811March 11, 1874) was an American statesman and United States Senator from Massachusetts. As an academic lawyer and a powerful orator, Sumner was the leader of the anti-slavery forces in the state and a leader of th ...

, requesting a university motto. Sumner replied with "Amore ac Studio" which means "with ardor and devotion" but is translated as "with love of learning".

Construction of the school began in Parsonsfield, Maine, however, the project drew the attention of millionaire textile tycoon, Benjamin Bates, who took special interest in the college. He convinced Cheney to build his school in the economically booming town of Lewiston, where Bates had begun to develop highly profitable mills. The college was moved to the town and incorporated as the Maine State Seminary on March 16, 1855.

The charter petition paid particular attention to fellow Maine colleges, Bowdoin and Colby College

Colby College is a private liberal arts college in Waterville, Maine. It was founded in 1813 as the Maine Literary and Theological Institution, then renamed Waterville College after the city where it resides. The donations of Christian philanthr ...

in Brunswick and Waterville, respectively. Cheney wrote specifically with regard to the two colleges:We do not propose an Academy [referring toThe Maine State Seminary was founded on the principles ofColby College Colby College is a private liberal arts college in Waterville, Maine. It was founded in 1813 as the Maine Literary and Theological Institution, then renamed Waterville College after the city where it resides. The donations of Christian philanthr ...(then Waterville Academy)], but a school of higher order, between a college [referring toBowdoin College Bowdoin College ( ) is a private liberal arts college in Brunswick, Maine. When Bowdoin was chartered in 1794, Maine was still a part of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. The college offers 34 majors and 36 minors, as well as several joint eng ...] and an Academy. We shall petition the state legislature to suitably endow, as well as incorporate, such an institution. We know our claim is good and intend openly and manfully and we trust in a Christian spirit to press it. If we fail next winter, we shall try another legislature. If we fail on a second trial, we shall try a third and a fourth.

egalitarianism

Egalitarianism (), or equalitarianism, is a school of thought within political philosophy that builds from the concept of social equality, prioritizing it for all people. Egalitarian doctrines are generally characterized by the idea that all hu ...

and Scholarly method, scholarship. It opened officially in 1865 with one hundred and thirty-seven students and three societies: the Literary Fraternity, Philomathean Society and Ladies' Athenaeum. The school gained a reputation of exacting academic standards and for educating the working class of Maine. The college stood in firm contrast to Bowdoin College in that it advocated for equality and equal access. However, the relationship between the two colleges is complex. The only college Cheney would oversee was Bowdoin, he served as an overseer from 1860 to 1867. In 1860, Cheney delivered the graduating dress to a class of fifteen male students, stressing "impact in a changing world."

Benjamin Bates began to aggressively fund the college due to its increased status in Americana academia and values. He extended a principle $50,000 dollars to Cheney and at the end of his life, his overall contributions amounted to nearly $300,000.

Deeply moved by the financial backing of Bates, Cheney asked the board of the Seminary to rename the college in his honor. Bates College

Bates College () is a private liberal arts college in Lewiston, Maine. Anchored by the Historic Quad, the campus of Bates totals with a small urban campus which includes 33 Victorian Houses as some of the dormitories. It maintains of nature p ...

was chartered on March 16, 1864. Cheney required that admission to Bates be exacting and required testimonials of good moral character

Good moral character is an ideal state of a person's beliefs and values that is considered most beneficial to society.

In United States law, good moral character can be assessed through the requirement of virtuous acts or by principally evaluatin ...

, readings of Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

which included Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman people, Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in Caes ...

, Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the estab ...

, Vergil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; traditional dates 15 October 7021 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Roman poet of the Augustan period. He composed three of the most famous poems in Latin literature: th ...

and elementary French. Cheney made sure that Bates was originally affiliated with the Freewill Baptist denomination and later with the Northern Baptist

The American Baptist Churches USA (ABCUSA) is a mainline/evangelical Baptist Christian denomination within the United States. The denomination maintains headquarters in Valley Forge, Pennsylvania. The organization is usually considered mainli ...

churches. He often noted Dartmouth v. United States, a Supreme Court case in reinforcing his beliefs that "a college can never pass into the hands of any other people or party without the consent of these churches or their proper representatives."

During the Civil War, Cheney was stirred and encouraged students to fight in the war as a test of their convictions, he said to an incoming class, "the freemen of the north are ready. Slavery must die. I am ready to die for freedom", causing them question the dynamic involved at the school as this was not a student but the President asserting such a statement.

In 1891, Cheney amended the charter

A charter is the grant of authority or rights, stating that the granter formally recognizes the prerogative of the recipient to exercise the rights specified. It is implicit that the granter retains superiority (or sovereignty), and that the rec ...

to Bates to require that its president and a majority of the trustees be members of the Free Will Baptist denomination. After he retired, this amendment was revoked by the legislature in 1907 at the request of his successor, George Colby Chase, which allowed the college to qualify for Carnegie Foundation funding for professor pensions.

Death and legacy

Cheney served as Bates' president for 39 years, retiring at age 79 in 1894. Cheney died in 1903 and was buried in Riverside Cemetery in Lewiston. Cheney also played a major role in founding several other Free Baptist institutions such asStorer College

Storer College was a historically black college in Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, that operated from 1867 to 1955. A national icon for Black Americans, in the town where the 'end of American slavery began', as Frederick Douglass famously put i ...

, a school for freed slaves in West Virginia founded in 1867; and the Maine Central Institute

Maine Central Institute (MCI) is an independent high school in Pittsfield, Maine, United States that was established in 1866. The school enrolls approximately 430 students and is a nonsectarian institution. The school has both boarding and da ...

(MCI), founded in 1866. Cheney founded and was the first president of the Free Will Baptist Church at Ocean Park, Maine

Ocean Park is a village in the town of Old Orchard Beach in York County, Maine, United States. A historic family style summer community affiliated with the Free Will Baptists, the community is located in southern Old Orchard Beach on Saco Bay. O ...

, a seaside retreat on Old Orchard Beach. In 1907, his third wife, Emeline, wrote a biography of his life, using his diaries and autobiographical articles he had published in the ''Morning Star''. The Cheney House, built in 1875 when Cheney was president, was acquired in 1905 by Bates College. Today it is used as a dormitory, a "quiet house" for 32 students.

See also

*History of Bates College

The history of Bates College began shortly before Bates College's founding on March 16, 1855, in Lewiston, Maine. The college was founded by Oren Burbank Cheney and Benjamin Bates. Originating as a Free Will Baptist institution, it has since se ...

*List of Bates College people

This list of notable people associated with Bates College includes Matriculation, matriculating students, Alumnus, alumni, attendees, faculty, trustees, and honorary degree recipients of Bates College in Lewiston, Maine. Members of the Bates co ...

References

Notes Further readingEmeline Cheney, ''The Story of the Life and Work of Oren B. Cheney''

' (Boston: Morning Star Publishing, 1907) '' *Timothy Larson

''Faith by Their Works: The Progressive Tradition at Bates College from 1855 to 1877''

'' Thesis at Muskie Archives,'' Bates College, 2005. *Multiple authors

New Hampshire State Magazine: Oren Burbank Cheney

''New Hampshire State Magazine''. 2010.

External links

Edmund S. Muskie Archives & Special Collections Library, Bates College {{DEFAULTSORT:Cheney, Oren B. 1816 births 1903 deaths 19th-century Baptist ministers from the United States Activists from New Hampshire American temperance activists Baptist abolitionists Brown University alumni Dartmouth College alumni Free Will Baptists Maine Free Soilers Republican Party members of the Maine House of Representatives People from Ashland, New Hampshire People from Holderness, New Hampshire People from Lebanon, Maine Politicians from Lewiston, Maine Presidents of Bates College Underground Railroad people University and college founders