Ordinances Of 1311 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Ordinances of 1311 were a series of regulations imposed upon King

When Edward II succeeded his father

When Edward II succeeded his father

The Ordinances were published widely on 11 October, with the intention of obtaining maximum popular support. The decade following their publication saw a constant struggle over their repeal or continued existence. Although they were not finally repealed until May 1322, the vigour with which they were enforced depended on who was in control of government.

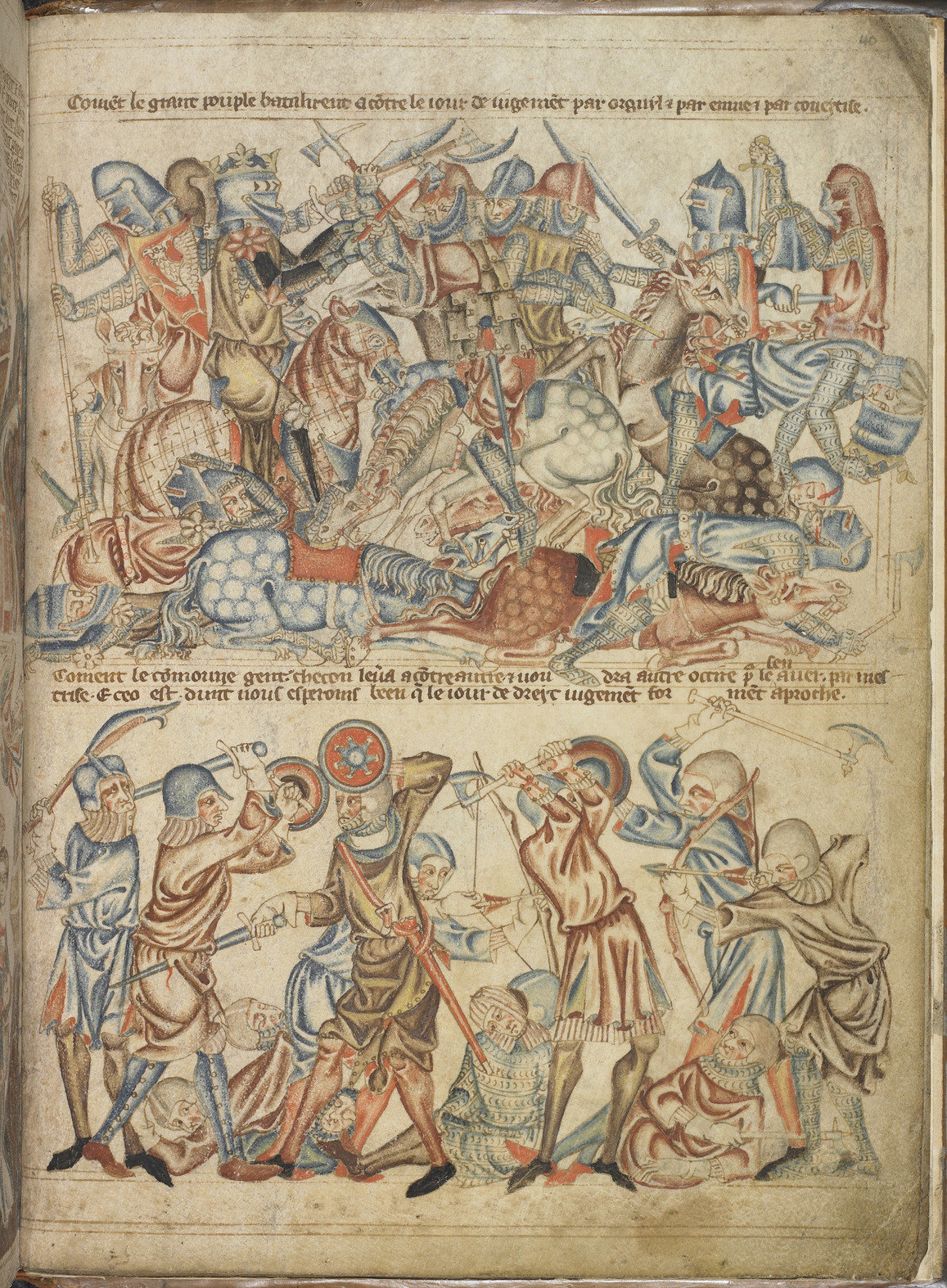

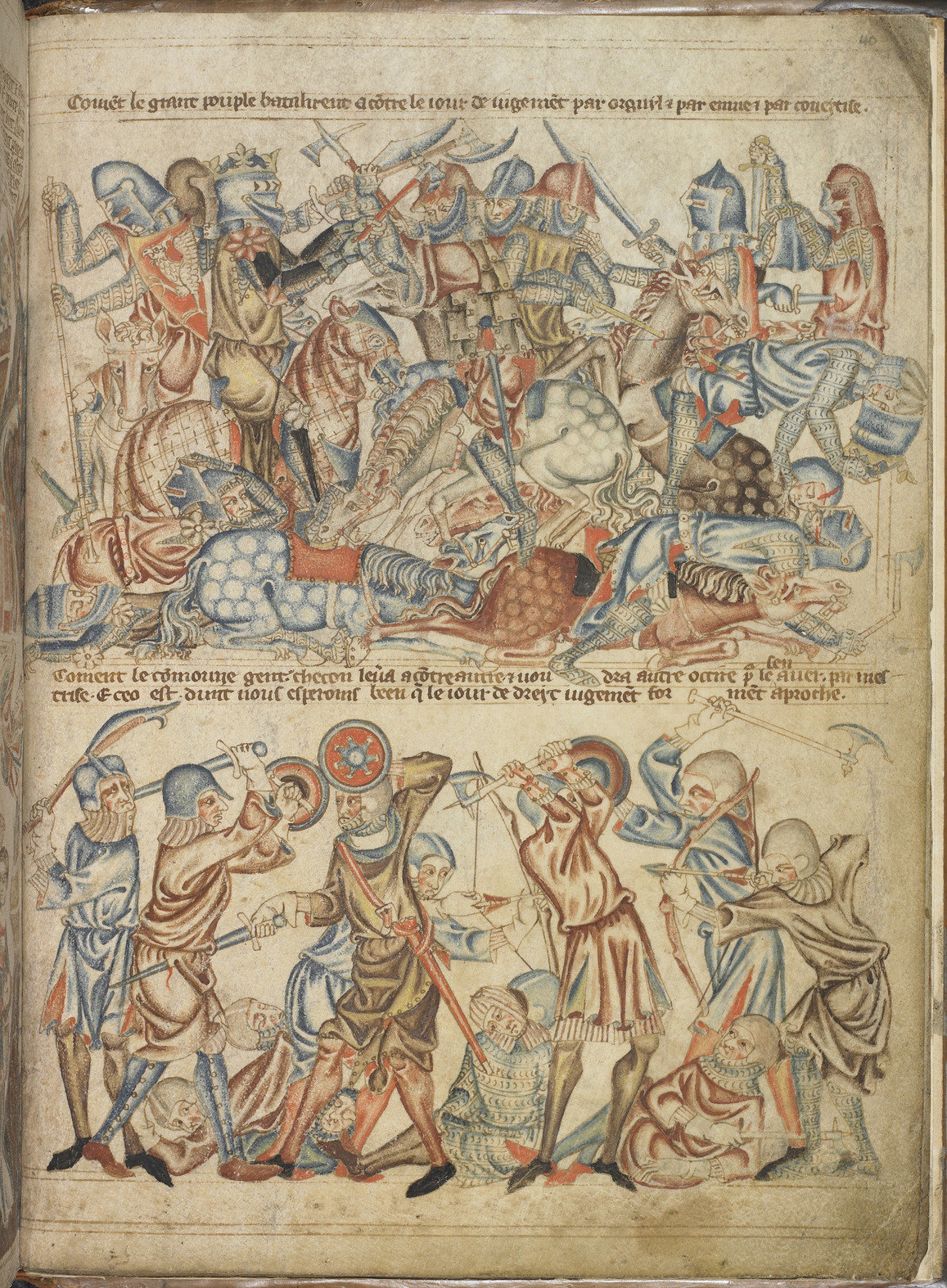

Before the end of the year, Gaveston had returned to England, and civil war appeared imminent. In May 1312, Gaveston was taken captive by the Earl of Pembroke, but Warwick and Lancaster had him abducted and executed after a mock trial. This affront to Pembroke's honour drove him irrevocably into the camp of the king, and thereby split the opposition. The brutality of the act initially drove Lancaster and his adherents away from the centre of power, but the

The Ordinances were published widely on 11 October, with the intention of obtaining maximum popular support. The decade following their publication saw a constant struggle over their repeal or continued existence. Although they were not finally repealed until May 1322, the vigour with which they were enforced depended on who was in control of government.

Before the end of the year, Gaveston had returned to England, and civil war appeared imminent. In May 1312, Gaveston was taken captive by the Earl of Pembroke, but Warwick and Lancaster had him abducted and executed after a mock trial. This affront to Pembroke's honour drove him irrevocably into the camp of the king, and thereby split the opposition. The brutality of the act initially drove Lancaster and his adherents away from the centre of power, but the

Abridged text of the Ordinances

{{featured article 14th century in England 1310s in law Medieval English law Edward II of England 1311 in England Political history of medieval England

Edward II

Edward II (25 April 1284 – 21 September 1327), also called Edward of Caernarfon, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 1307 until he was deposed in January 1327. The fourth son of Edward I, Edward became the heir apparent to t ...

by the peerage

A peerage is a legal system historically comprising various hereditary titles (and sometimes non-hereditary titles) in a number of countries, and composed of assorted noble ranks.

Peerages include:

Australia

* Australian peers

Belgium

* Belgi ...

and clergy of the Kingdom of England

The Kingdom of England (, ) was a sovereign state on the island of Great Britain from 12 July 927, when it emerged from various Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, until 1 May 1707, when it united with Scotland to form the Kingdom of Great Britain.

On 1 ...

to restrict the power of the English monarch

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, commonly referred to as the British monarchy, is the constitutional form of government by which a hereditary sovereign reigns as the head of state of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies (the Bailiwi ...

. The twenty-one signatories of the Ordinances are referred to as the Lords Ordainers, or simply the Ordainers. English setbacks in the Scottish war, combined with perceived extortionate royal fiscal policies, set the background for the writing of the Ordinances in which the administrative prerogatives of the king were largely appropriated by a baronial council. The Ordinances reflect the Provisions of Oxford

The Provisions of Oxford were constitutional reforms developed during the Oxford Parliament of 1258 to resolve a dispute between King Henry III of England and his barons. The reforms were designed to ensure the king adhered to the rule of law and ...

and the Provisions of Westminster

The Provisions of Westminster of 1259 were part of a series of legislative constitutional reforms that arose out of power struggles between Henry III of England and his barons. The King's failed campaigns in France in 1230 and 1242, and his choic ...

from the late 1250s, but unlike the Provisions, the Ordinances featured a new concern with fiscal reform, specifically redirecting revenues from the king's household

A household consists of two or more persons who live in the same dwelling. It may be of a single family or another type of person group. The household is the basic unit of analysis in many social, microeconomic and government models, and is im ...

to the exchequer

In the civil service of the United Kingdom, His Majesty’s Exchequer, or just the Exchequer, is the accounting process of central government and the government's ''current account'' (i.e., money held from taxation and other government reven ...

.

Just as instrumental to their conception were other issues, particularly discontent with the king's favourite

A favourite (British English) or favorite (American English) was the intimate companion of a ruler or other important person. In post-classical and early-modern Europe, among other times and places, the term was used of individuals delegated si ...

, Piers Gaveston

Piers Gaveston, Earl of Cornwall (c. 1284 – 19 June 1312) was an English nobleman of Gascon origin, and the favourite of Edward II of England.

At a young age, Gaveston made a good impression on King Edward I, who assigned him to the househ ...

, whom the barons subsequently banished from the realm. Edward II accepted the Ordinances only under coercion, and a long struggle for their repeal ensued that did not end until Earl Thomas of Lancaster

Thomas of Lancaster, 2nd Earl of Lancaster, 2nd Earl of Leicester, 2nd Earl of Derby, ''jure uxoris'' 4th Earl of Lincoln and ''jure uxoris'' 5th Earl of Salisbury (c. 1278 – 22 March 1322) was an English nobleman. A member of the House of Pl ...

, the leader of the Ordainers, was executed in 1322.

Background

Early problems

When Edward II succeeded his father

When Edward II succeeded his father Edward I

Edward I (17/18 June 1239 – 7 July 1307), also known as Edward Longshanks and the Hammer of the Scots, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 1272 to 1307. Concurrently, he ruled the duchies of Aquitaine and Gascony as a vassal o ...

on 7 July 1307, the attitude of his subjects was generally one of goodwill towards their new king. However, discontent was brewing beneath the surface. Some of this was due to existing problems left behind by the late king, while much was due to the new king's inadequacies. The problems were threefold. First there was discontent with the royal policy for financing wars. To finance the war in Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to the ...

, Edward I had increasingly resorted to so-called prises – or purveyance

Purveyance was an ancient prerogative right of the English Crown to purchase provisions and other necessaries for the royal household, at an appraised price, and to requisition horses and vehicles for royal use.{{Cite book , title=Osborn's Law ...

– to provision the troops with victuals. The peers felt that the purveyance had become far too burdensome and compensation was in many cases inadequate or missing entirely. In addition, they did not like the fact that Edward II took prises for his household without continuing the war effort against Scotland, causing the second problem. While Edward I had spent the last decade of his reign relentlessly campaigning against the Scots, his son abandoned the war almost entirely. In this situation, the Scottish king Robert Bruce

Robert I (11 July 1274 – 7 June 1329), popularly known as Robert the Bruce (Scottish Gaelic: ''Raibeart an Bruis''), was King of Scots from 1306 to his death in 1329. One of the most renowned warriors of his generation, Robert eventuall ...

soon took the opportunity to regain what had been lost. This not only exposed the north of England to Scottish attacks, but also jeopardized the possessions of the English baronage

{{English Feudalism

In England, the ''baronage'' was the collectively inclusive term denoting all members of the feudal nobility, as observed by the constitutional authority Edward Coke. It was replaced eventually by the term ''peerage''.

Origi ...

in Scotland.

The third and most serious problem concerned the king's favourite, Piers Gaveston

Piers Gaveston, Earl of Cornwall (c. 1284 – 19 June 1312) was an English nobleman of Gascon origin, and the favourite of Edward II of England.

At a young age, Gaveston made a good impression on King Edward I, who assigned him to the househ ...

. Gaveston was a Gascon of relatively humble origins, with whom the king had developed a particularly close relationship. Among the honours Edward heaped upon Gaveston was the earldom of Cornwall

The title of Earl of Cornwall was created several times in the Peerage of England before 1337, when it was superseded by the title Duke of Cornwall, which became attached to heirs-apparent to the throne.

Condor of Cornwall

* Condor of Cornwall, ...

, a title which had previously only been conferred on members of the royal family. The preferential treatment of an upstart like Gaveston, in combination with his behaviour that was seen as arrogant, led to resentment among the established peers of the realm. This resentment first came to the surface in a declaration written in Boulogne

Boulogne-sur-Mer (; pcd, Boulonne-su-Mér; nl, Bonen; la, Gesoriacum or ''Bononia''), often called just Boulogne (, ), is a coastal city in Northern France. It is a sub-prefecture of the department of Pas-de-Calais. Boulogne lies on the ...

by a group of magnate

The magnate term, from the late Latin ''magnas'', a great man, itself from Latin ''magnus'', "great", means a man from the higher nobility, a man who belongs to the high office-holders, or a man in a high social position, by birth, wealth or ot ...

s who were with the king when he was in France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

for his marriage ceremony to the French king's daughter. The so-called Boulogne agreement

The Boulogne agreement was a document signed by a group of English magnates in 1308, concerning the government of Edward II. After the death of Edward I in 1307, discontent soon developed against the new king. This was partly due to lingering ...

was vague, but it expressed clear concern over the state of the royal court. On 25 February 1308, the new king was crowned. The oath he was made to take at the coronation

A coronation is the act of placement or bestowal of a coronation crown, crown upon a monarch's head. The term also generally refers not only to the physical crowning but to the whole ceremony wherein the act of crowning occurs, along with the ...

differed from that of previous kings in the fourth clause; here Edward was required to promise to maintain the laws that the community "shall have chosen" ("''aura eslu''"). Though it is unclear what exactly was meant by this wording at the time, this oath was later used in the struggle between the king and his earls.

Gaveston’s exile

In theparliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

of April 1308, it was decided that Gaveston should be banned from the realm upon threat of excommunication

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to end or at least regulate the communion of a member of a congregation with other members of the religious institution who are in normal communion with each other. The purpose ...

. The king had no choice but to comply, and on 24 June, Gaveston left the country on appointment as Lieutenant of Ireland. The king immediately started plotting for his favourite's return. At the parliament of April 1309, he suggested a compromise in which certain of the earls' petitions would be met in exchange for Gaveston's return. The plan came to nothing, but Edward had strengthened his hand for the Stamford parliament in July later that year by receiving a papal annulment of the threat of excommunication. The king agreed to the so-called "Statute of Stamford" (which in essence was a reissue of the '' Articuli super Cartas'' that his father had signed in 1300), and Gaveston was allowed to return.

The earls who agreed to the compromise were hoping that Gaveston had learned his lesson. Yet upon his return, he was more arrogant than ever, conferring insulting nicknames on some of the greater nobles. When the king summoned a great council in October, several of the earls refused to meet due to Gaveston's presence. At the parliament of February in the following year, Gaveston was ordered not to attend. The earls disobeyed a royal order not to carry arms to parliament, and in full military attire presented a demand to the king for the appointment of a commission of reform. On 16 March 1310, the king agreed to the appointment of Ordainers, who were to be in charge of the reform of the royal household.McKisack, 10.

Lords Ordainers

The Ordainers were elected by an assembly of magnates, without representation from the commons. They were a diverse group, consisting of eightearl

Earl () is a rank of the nobility in the United Kingdom. The title originates in the Old English word ''eorl'', meaning "a man of noble birth or rank". The word is cognate with the Scandinavian form ''jarl'', and meant "chieftain", particular ...

s, seven bishop

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ca ...

s and six baron

Baron is a rank of nobility or title of honour, often hereditary, in various European countries, either current or historical. The female equivalent is baroness. Typically, the title denotes an aristocrat who ranks higher than a lord or knig ...

s – twenty-one in all. There were faithful royalists represented as well as fierce opponents of the king.

Among the Ordainers considered loyal to Edward II was John of Brittany, Earl of Richmond

John of Brittany (french: Jean de Bretagne; c. 1266 – 17 January 1334), 4th Earl of Richmond, was an English nobleman and a member of the Ducal house of Brittany, the House of Dreux. He entered royal service in England under his uncle Edw ...

who was also by this time one of the older remaining earls. John had served Edward I, his uncle, and was Edward II's first cousin. The natural leader of the group was Henry Lacy, Earl of Lincoln. One of the wealthiest men in the country, he was also the oldest of the earls and had proved his loyalty and ableness through long service to Edward I. Lincoln had a moderating influence on the more extreme members of the group, but with his death in February 1311, leadership passed to his son-in-law and heir Thomas of Lancaster

Thomas of Lancaster, 2nd Earl of Lancaster, 2nd Earl of Leicester, 2nd Earl of Derby, ''jure uxoris'' 4th Earl of Lincoln and ''jure uxoris'' 5th Earl of Salisbury (c. 1278 – 22 March 1322) was an English nobleman. A member of the House of Pl ...

. Lancaster – the king's cousin – was now in possession of five earldoms which made him by far the wealthiest man in the country, save the king. There is no evidence that Lancaster was in opposition to the king in the early years of the king's reign, but by the time of the Ordinances it is clear that something had negatively affected his opinion of King Edward.

Lancaster's main ally was Guy Beauchamp, Earl of Warwick. Warwick was the most fervently and consistently antagonistic of the earls, and remained so until his early death in 1315. Other earls were more amenable. Gilbert de Clare, Earl of Gloucester, was Gaveston's brother-in-law and stayed loyal to the king. Aymer de Valence, Earl of Pembroke, would later be one of the king's most central supporters, yet at this point he found the most prudent course of action was to go along with the reformers. Of the barons, at least Robert Clifford and William Marshall seemed to have royalist leanings.

Among the bishops, only two stood out as significant political figures, the more prominent of whom was Robert Winchelsey

Robert Winchelsey (or Winchelsea; c. 1245 – 11 May 1313) was an English Catholic theologian and Archbishop of Canterbury. He studied at the universities of Paris and Oxford, and later taught at both. Influenced by Thomas Aquinas, he was a sc ...

, Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. The current archbishop is Justi ...

. Long a formidable presence in English public life, Winchelsey had led the struggle against Edward I to uphold the autonomy of the church, and for this he had paid with suspension and exile. One of Edward II's first acts as king had been to reinstate Winchelsey, but rather than responding with grateful loyalty, the archbishop soon reassumed a leadership role in the fight against the king. Although he was trying to appease Winchelsey, the king carried an old grudge against another prelate, Walter Langton

Walter Langton (died 1321) of Castle Ashby'Parishes: Castle Ashby', in A History of the County of Northampton: Volume 4, ed. L F Salzman (London, 1937), pp. 230-236/ref> in Northamptonshire, was Bishop of Lichfield, Bishop of Coventry and Lic ...

, Bishop of Lichfield

The Bishop of Lichfield is the ordinary of the Church of England Diocese of Lichfield in the Province of Canterbury. The diocese covers 4,516 km2 (1,744 sq. mi.) of the counties of Powys, Staffordshire, Shropshire, Warwickshire and West Mi ...

. Edward had Langton dismissed from his position as treasurer of the Exchequer

The post of Lord High Treasurer or Lord Treasurer was an English government position and has been a British government position since the Acts of Union of 1707. A holder of the post would be the third-highest-ranked Great Officer of State i ...

and had his temporal possessions confiscated. Langton had been an opponent of Winchelsey during the previous reign, but Edward II's move against Langton drew the two Ordainers together.McKisack, 9.

Ordinances

Six preliminary ordinances were released immediately upon the appointment of the Ordainers – on 19 March 1310 – but it was not until August 1311 that the committee had finished its work. In the meanwhile Edward had been in Scotland on an aborted campaign, but on 16 August, Parliament met inLondon

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

, and the king was presented with the Ordinances.

The document containing the Ordinances is dated 5 October, and contains forty-one articles. In the preamble, the Ordainers voiced their concern over what they perceived as the evil councilors of the king, the precariousness of the military situation abroad, and the danger of rebellion at home over the oppressive prises. The articles can be divided into different groups, the largest of which deals with limitations on the powers of the king and his officials, and the substitution of these powers with baronial control. It was ordained that the king should appoint his officers only "by the counsel and assent of the baronage, and that in parliament." Furthermore, the king could no longer go to war without the consent of the baronage, nor could he make reforms of the coinage. Additionally, it was decided that parliament should be held at least once a year. Parallel to these decisions were reforms of the royal finances. The Ordinances banned what was seen as extortionate prises and customs, and at the same time declared that revenues were to be paid directly into the Exchequer

In the civil service of the United Kingdom, His Majesty’s Exchequer, or just the Exchequer, is the accounting process of central government and the government's ''current account'' (i.e., money held from taxation and other government reven ...

. This was a reaction to the rising trend of receiving revenues directly into the royal household; making all royal finances accountable to the exchequer allowed greater public scrutiny.McKisack, 15.

Other articles dealt with punishing specific persons, foremost among these, Piers Gaveston. Article 20 describes at length the offences committed by Gaveston; he was once more condemned to exile and was to abjure the realm by 1 November. The bankers of the Italian Frescobaldi

The Frescobaldi are a prominent Florentine noble family that have been involved in the political, social, and economic history of Tuscany since the Middle Ages. Originating in the Val di Pesa in the Chianti, they appear holding important posts ...

company were arrested, and their goods seized. It was held that the king's great financial dependence on the Italians was politically unfortunate. The last individuals to be singled out for punishment were Henry de Beaumont

Henry de Beaumont (before 1280 – 10 March 1340), '' jure uxoris'' 4th Earl of Buchan and ''suo jure'' 1st Baron Beaumont, was a key figure in the Anglo-Scots wars of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, known as the Wars of Scottish Ind ...

and his sister, Isabella de Vesci

Isabella de Beaumont (died 1334), was a prominent noblewoman allied to Isabella of France during the reign of Edward II of England.

Reign of Edward I and marriage

Isabella de Beaumont was the daughter of Sir Louis de Brienne and Agnés de ...

, two foreigners associated with the king's household. Though it is difficult to say why these two received particular mention, it could be related to the central position of their possessions in the Scottish war.

The Ordainers also took care to confirm and elaborate on existing statutes, and reforms were made to the criminal law. The liberties of the church were confirmed as well. To ensure that none of the Ordainers should be swayed in their decisions by bribes from the king, restrictions were made on what royal gifts and offices they were allowed to receive during their tenure.

Aftermath

The Ordinances were published widely on 11 October, with the intention of obtaining maximum popular support. The decade following their publication saw a constant struggle over their repeal or continued existence. Although they were not finally repealed until May 1322, the vigour with which they were enforced depended on who was in control of government.

Before the end of the year, Gaveston had returned to England, and civil war appeared imminent. In May 1312, Gaveston was taken captive by the Earl of Pembroke, but Warwick and Lancaster had him abducted and executed after a mock trial. This affront to Pembroke's honour drove him irrevocably into the camp of the king, and thereby split the opposition. The brutality of the act initially drove Lancaster and his adherents away from the centre of power, but the

The Ordinances were published widely on 11 October, with the intention of obtaining maximum popular support. The decade following their publication saw a constant struggle over their repeal or continued existence. Although they were not finally repealed until May 1322, the vigour with which they were enforced depended on who was in control of government.

Before the end of the year, Gaveston had returned to England, and civil war appeared imminent. In May 1312, Gaveston was taken captive by the Earl of Pembroke, but Warwick and Lancaster had him abducted and executed after a mock trial. This affront to Pembroke's honour drove him irrevocably into the camp of the king, and thereby split the opposition. The brutality of the act initially drove Lancaster and his adherents away from the centre of power, but the Battle of Bannockburn

The Battle of Bannockburn ( gd, Blàr Allt nam Bànag or ) fought on June 23–24, 1314, was a victory of the army of King of Scots Robert the Bruce over the army of King Edward II of England in the First War of Scottish Independence. It was ...

, in June 1314, returned the initiative. Edward was humiliated by his disastrous defeat, while Lancaster and Warwick had not taken part in the campaign, claiming that it was carried out without the consent of the baronage, and as such in defiance of the Ordinances.

What followed was a period of virtual control of the government by Lancaster, yet increasingly – particularly after the death of Warwick in 1315 – he found himself isolated. In August 1318, the so-called "Treaty of Leake

The Treaty of Leake was an agreement between the "Middle Party", including courtier adherents of Edward II of England, and the king's cousin, the Earl Thomas of Lancaster and his followers. It was signed at Leake in Nottinghamshire on 9 August 1 ...

" established a '' modus vivendi'' between the parties, whereby the king was restored to power while promising to uphold the Ordinances. Lancaster still had differences with the king, though—particularly with the conduct of the new favourite, Hugh Despenser the younger

Hugh le Despenser, 1st Baron le Despenser (c. 1287/1289 – 24 November 1326), also referred to as "the Younger Despenser", was the son and heir of Hugh le Despenser, Earl of Winchester (the Elder Despenser), by his wife Isabella de Beauchamp, ...

, and Hugh's father. In 1322, full rebellion broke out which ended with Lancaster's defeat at the Battle of Boroughbridge

The Battle of Boroughbridge was fought on 16 March 1322 in England between a group of rebellious barons and the forces of King Edward II, near Boroughbridge, north-west of York. The culmination of a long period of antagonism between the King a ...

and his execution shortly after during March 1322. At the parliament of May in the same year, the Ordinances were repealed by the Statute of York

The Statute of York was a 1322 Act of the Parliament of England that repealed the Ordinances of 1311 and prevented any similar provisions from being established. Academics argue over the actual impact of the bill, but general consensus is that i ...

.Prestwich, 205. However, six clauses were retained that concerned such issues as household jurisdiction and appointment of sheriffs. Any restrictions on royal power were unequivocally annulled.

The Ordinances were never again reissued, and therefore hold no permanent position in the legal history of England in the way that Magna Carta

(Medieval Latin for "Great Charter of Freedoms"), commonly called (also ''Magna Charta''; "Great Charter"), is a royal charter of rights agreed to by King John of England at Runnymede, near Windsor, on 15 June 1215. First drafted by the ...

, for instance, does. The criticism has been against the conservative focus of the barons' role in national politics, ignoring the ascendancy of the commons. Yet the document, and the movement behind it, reflected new political developments in its emphasis on how assent was to be obtained by the barons ''in parliament''. It was only a matter of time before it was generally acknowledged that the Commons

The commons is the cultural and natural resources accessible to all members of a society, including natural materials such as air, water, and a habitable Earth. These resources are held in common even when owned privately or publicly. Commons ...

were an integral part of that institution.Prestwich, 186–7.

See also

*History of the British constitution

History (derived ) is the systematic study and the documentation of the human activity. The time period of event before the invention of writing systems is considered prehistory. "History" is an umbrella term comprising past events as well ...

*Royal Prerogative

The royal prerogative is a body of customary authority, privilege and immunity, recognized in common law and, sometimes, in civil law jurisdictions possessing a monarchy, as belonging to the sovereign and which have become widely vested in th ...

Notes

Citations

References

Primary

* *Secondary

* * * * * * * * * * *External links

Abridged text of the Ordinances

{{featured article 14th century in England 1310s in law Medieval English law Edward II of England 1311 in England Political history of medieval England