Opicinus De Canistris on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Opicinus de Canistris (24 December 1296 – c. 1353), also known as the ''Anonymous Ticinensis'', was an Italian priest, writer, mystic, and cartographer who generated a number of unusual writings and fantastic cosmological diagrams. Autobiographical in origin, they provide the majority of information about his life. When his works were rediscovered in the early twentieth century, some scholars deemed his works to be “

During his stay in Valenza, he wrote a treatise on the issue of Christian poverty (which has not been preserved). Arrived in Avignon in April 1329, where the Papal Court was located he managed to present his treatise to Pope

During his stay in Valenza, he wrote a treatise on the issue of Christian poverty (which has not been preserved). Arrived in Avignon in April 1329, where the Papal Court was located he managed to present his treatise to Pope

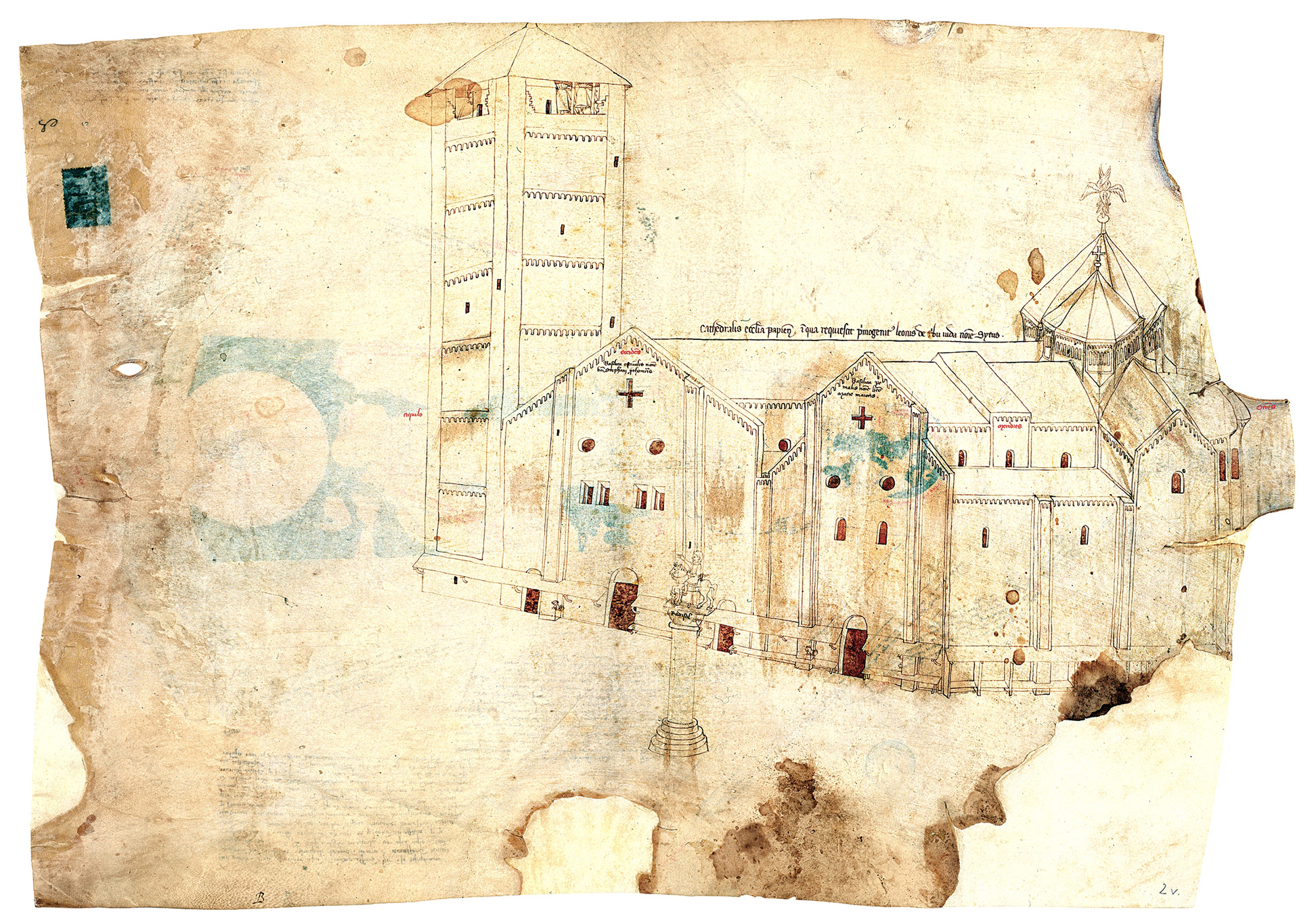

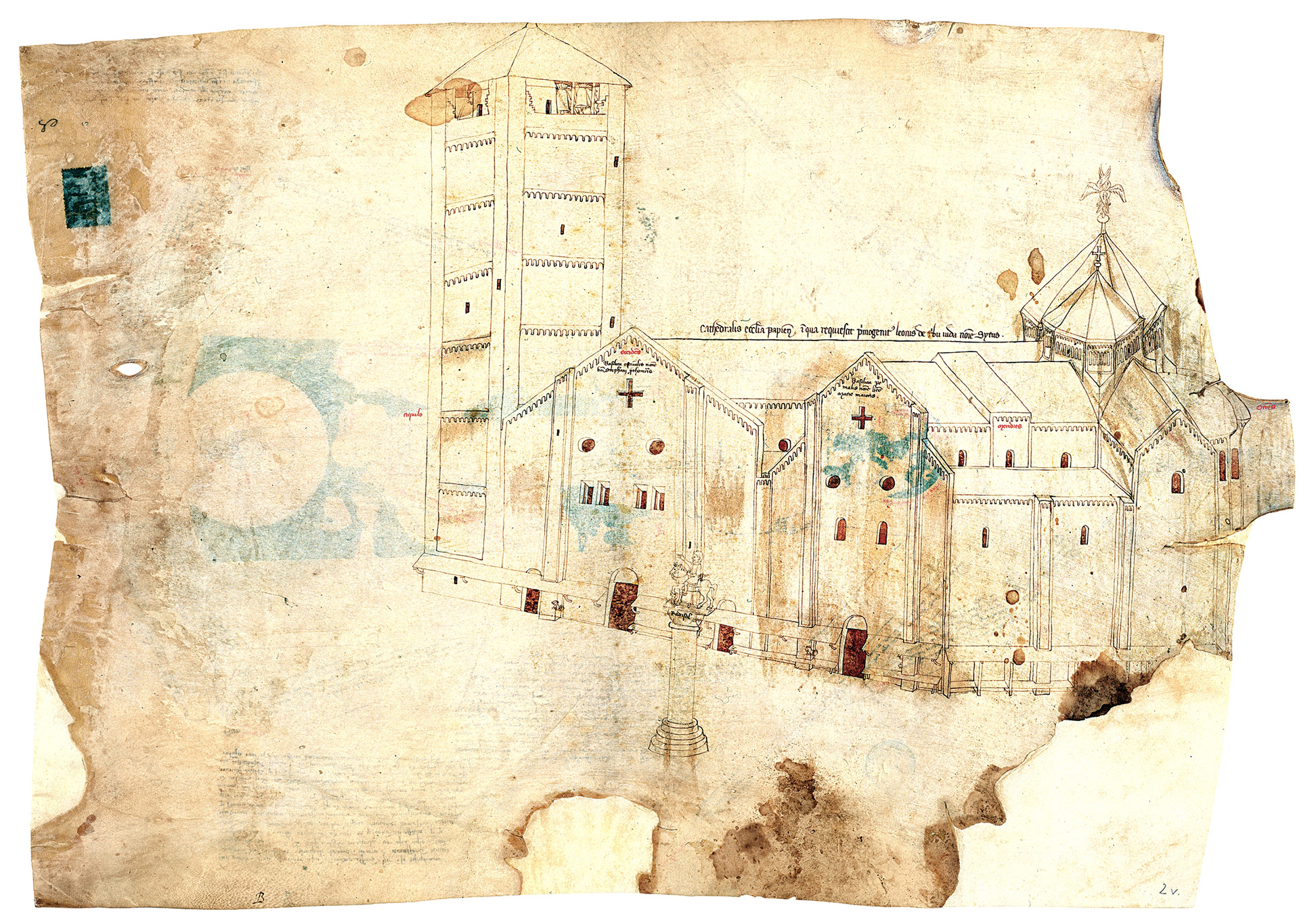

Cathedral of Pavia

from manuscript Vatican, Pal. Lat. 1993 in the website of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Visual Metaphysics: Opicinus de Canistris

by Nathan Schneider

at cartographic-images.net {{DEFAULTSORT:Opicinus De Canistris 14th-century Italian Roman Catholic priests Italian male writers 13th-century births 14th-century deaths

psychotic

Psychosis is a condition of the mind that results in difficulties determining what is real and what is not real. Symptoms may include delusions and hallucinations, among other features. Additional symptoms are incoherent speech and behavior ...

” due to their extraordinary theological musings and schematic diagrams. The merits of this psychoanalytic interpretation, however, are currently under debate.

Biography

Northern Italy (1296-1329)

Opicinus was born December 24, 1296, inLomello

Lomello is a ''comune'' (municipality) in the Province of Pavia in the Italy, Italian region Lombardy, located about 50 km southwest of Milan and about 30 km west of Pavia, on the right bank of the Agogna. It gives its name to the surroun ...

, near Pavia

Pavia (, , , ; la, Ticinum; Medieval Latin: ) is a town and comune of south-western Lombardy in northern Italy, south of Milan on the lower Ticino river near its confluence with the Po. It has a population of c. 73,086. The city was the capit ...

, Italy. His family, which was well known in Pavia, actively supported the Guelphs

The Guelphs and Ghibellines (, , ; it, guelfi e ghibellini ) were factions supporting the Pope and the Holy Roman Emperor, respectively, in the Italian city-states of Central Italy and Northern Italy.

During the 12th and 13th centuries, rivalr ...

against the Ghibellines

The Guelphs and Ghibellines (, , ; it, guelfi e ghibellini ) were factions supporting the Pope and the Holy Roman Emperor, respectively, in the Italian city-states of Central Italy and Northern Italy.

During the 12th and 13th centuries, rivalr ...

.

He went to school from the age of six. He then studied liberal arts and progressively received an eclectic encyclopaedical training. From a very early age he was interested in drawing. He had several temporary jobs to materially help his family.

The storming of Pavia by the Ghibellines on October 8, 1315 forced Canistris' family to take exile in Genoa for three years. Opicinus then distanced himself from the Guelph part of his family, especially following the death of his father and one of his younger brothers.

In Genoa he studied theology and the Bible in greater depth and developed his talent for drawing. During this period he was able to see the first "sea maps" (incorrectly known as "portolans"). When he returned to Pavia in 1318, he studied to become a priest, and from 1319 he drew up religious treaties. He was ordained in Parma on February 27, 1320, and in 1323 obtained a modest parish in Pavia (Santa Maria Capella).

Between 1325 and 1328, his autobiography doesn't mention any event. Towards the end of this period, he wrote a treatise defending the supremacy of the papacy over the Empire (''De preeminentia spiritualis imperii)'' against the ecclesiological views of Marsilius of Padua

Marsilius of Padua (Italian: ''Marsilio'' or ''Marsiglio da Padova''; born ''Marsilio dei Mainardini'' or ''Marsilio Mainardini''; c. 1270 – c. 1342) was an Italian scholar, trained in medicine, who practiced a variety of professions. He ...

, then a close adviser to the emperor elect Lewis of Bavaria

Louis IV (german: Ludwig; 1 April 1282 – 11 October 1347), called the Bavarian, of the house of Wittelsbach, was King of the Romans from 1314, King of Italy from 1327, and Holy Roman Emperor from 1328.

Louis' election as king of Germany in ...

in whose hands Pavia had fallen. It is probably this which lead him to leave the city, and find refuge in the nearby Piemontese city of Valenza

Valenza ( pms, Valensa) is a ''comune'' (municipality) in the Province of Alessandria in the Italian region Piedmont, located about east of Turin and about north of Alessandria.

History

A stronghold of the Ligures, it was conquered by the Roma ...

in the summer of 1329.

Avignon (1329 – circa 1353)

During his stay in Valenza, he wrote a treatise on the issue of Christian poverty (which has not been preserved). Arrived in Avignon in April 1329, where the Papal Court was located he managed to present his treatise to Pope

During his stay in Valenza, he wrote a treatise on the issue of Christian poverty (which has not been preserved). Arrived in Avignon in April 1329, where the Papal Court was located he managed to present his treatise to Pope John XXII

Pope John XXII ( la, Ioannes PP. XXII; 1244 – 4 December 1334), born Jacques Duèze (or d'Euse), was head of the Catholic Church from 7 August 1316 to his death in December 1334.

He was the second and longest-reigning Avignon Pope, elected by ...

. Returning to Valenza, he revised the ''De preeminentia spiritualis imperii'' and submitted to the pope. While awaiting for some rewards for his efforts, Opicinus produced a description of the city of Pavia (''De laudibus civitatis ticinensis'').

He eventually obtained a position as scribe at the Apostolic Penitentiary

The Apostolic Penitentiary (), formerly called the Supreme Tribunal of the Apostolic Penitentiary, is a dicastery of the Roman Curia and is one of the three ordinary tribunals of the Apostolic See. The Apostolic Penitentiary is chiefly a tribu ...

on December 4, 1330. However soon after, a suit was brought against him before the Rota, by the new bishop of Pavia, Giovanni Fulgosi, as part of a wider effort to reorganize the local clergy. Little is known about the suit, as in his writings, Opicinus is quite vague about its nature.

Illness and visions

On March 31, 1334 Opicinus suffered a serious illness in which he became comatose for nearly two weeks. When he recovered, he discovered that much of his memory was gone, that he could not speak and that his right hand was useless. He wrote, Ultimately, Opicinus did recover his memory, speech and some function in his hand. He attributed this healing to a vision he experienced on August 15 (coincidentally the date of the feast of the assumption of the Virgin). Opicinus believed that his illness was the result of hidden sins that had corrupted his body. However, he interpreted his recovery as spiritual gift that allowed him to reveal spiritual truth. The “pictures” he refers to are a complex series of maps and schematic diagrams in two manuscripts currently held at the Vatican library, ''Palatinus 1993'' and ''Vaticanus 6435''. These drawings were a means for Opicinus to chart the spiritual realities that he believed were the underpinnings of the physical world. Much scholarship has interpreted Opicinus’s illness as psychosomatic, specifically the product of schizophrenia. However, whatever symptomatology can be gleaned from Opicinus’s abstruse writings seems to suggest that he suffered a stroke in addition to potential psychotic episodes. He died inAvignon

Avignon (, ; ; oc, Avinhon, label=Provençal dialect, Provençal or , ; la, Avenio) is the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Vaucluse Departments of France, department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur Regions of France, region of So ...

around 1353.

Works

Writings prior to 1334

These are treaties without drawings and known by the author's friends. Only ''De preeminentia spiritualis imperii (The primacy of spiritual power)'' and ''De laudibus Papie (Pavia eulogy)'' have survived to date in the form of copies.''De preeminentia spiritualis imperii'' (1329). Cf. SCHOLZ (R.), ''Unbekannte Kirchenpolitische Streischriften aus der Zeit Ludwig des Bayern'' (1327–1354), Rome, Verlag von Loescher & Cie, vol. 1, 1911, p. 37-43, and vol. 2, 1914, p. 89-104. ''De laudibus civitatis ticinensis'' (1330). Cf. GIANANI (F.), in ''Opicino de Canistris, l’Anonimo Ticinese'', Pavia, EMI, 1996, p. 73-121; and AMBAGLIO (D.), Il libro delle lodi della città di Pavia, Pavia, 1984. Their content is classical. * 1319: ''Liber metricus de parabolis Christi'' * 1320: ''De decalogo mandatorum'' * 1322: religious treaties * 1324: ''Libellus dominice Passionis secundum concordantiam IIII evangelistarum'' * 1329: ''De paupertate Christi, De virtutibus Christi, Lamentationes virginis Marie, De preeminentia spiritualis imperii'' * 1330: ''Tractatus dominice orationis, Libellus confessionis, De laudibus Papie'' * 1331: ''Tabula ecclesiastice hierarchie'' * 1332: ''De septiloquio virginis Marie'' * 1333: ''De promotionibus virginis Marie''Work after 1334

Opicinus is best known for the two manuscripts he created following his illness, "BAV, Pal. lat. 1993" and "BAV, Vat. lat. 6435." These two manuscripts contain a variety of autobiographic drawings and writings which chart Opicinus's life and illness.The ''Vaticanus latinus'' 6435 manuscript

Opicinus wrote the ''Vaticanus latinus'' between June and November 1337 and subsequently inserted ''addita'' (the last in December 1352). This manuscript, which was only identified on the eve ofWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, was recently fully published and translated by the medievalist Muriel Laharie as well as several studies by the psychiatrist Guy Roux – a multi-disciplinary collaboration essential to examining this singular work.

The ''Vaticanus'' comes in the form of a paper codex with 87 folios, with only written text in the first half, text and drawings (often map based) in the second half. It is a very dense document.

This codex looks similar to a journal written in chronological order. However, its polymorphous content, which is difficult to decipher, bears witness to the encyclopaedic culture of its author. Opicinus used all his knowledge to construct a cosmic identity appearing in numerous guises; he is God, the Sun, the Pope, Europe, Avignon, etc. Its colour anthropomorphic maps of the Mediterranean area, precise and curiously organised, illustrate "good" and "bad" characters and animals on which he projects himself and his enemies. The use of symbols, his taste for dissimulating and manipulating (words, numbers, space), and his attraction to the obscene and scatological are omnipresent and relate strongly to similar themes found broadly in medieval culture.

The ''Palatinus latinus'' 1993 manuscript

The ''Palatinus latinus'', first identified in 1913, was the subject of a study by Richard Salomon in 1939, with a partial edition of the document and comments. With 52 large colour drawings on parchment (often used on both sides) and covered with notes, ''Palatinus, 1993'' apparently relies much less on a cartographic format ; yet, invisible maps of the Mediterranean are underlying most of the diagrams, with sometimes only a few places expressed. The drawings are extremely schematic, using human figures covered in circles and ellipses. Opicinus also included a plethora of biblical quotations, calendars, astrological charts and medical imagery. Some scholars (M. Laharie and G. Roux) claim that these drawings were produced later than the ''Vaticanus'', with no firm basis. Only two diagrams are dated or connected to the 1350 Jubilee. Other evidences rather point to an early production of most of the other drawings, in 1335 or 1336, before the ''Vaticanus''.References

Further reading

* Camille, Michael. “The Image and the Self: Unwriting Late Medieval Bodies,” in ''Framing Medieval Bodies.'' (ed.) Sarah Kay and Miri Rubin. New York, NY. Manchester University Press, 1994 * Gurevich, Aron Yakovlevich. “L'individualité au Moyen Age: le cas d'Opicinus de Canistris,” in ''Annales ESC: économies, sociétés, civilisations:'' (later Annales - Histoire, Sciences Sociales) vol. 48:5, pp. 1263–1280, 1993 * Kris, Ernst. “A Psychotic Artist of the Middle Ages,” in ''Psychoanalytic Exploration in Art.'' New York, NY. International Universities Press, 1952 * Laharie (M.), ''Le journal singulier d’Opicinus de Canistris'' (1337 - ''circa''. 1341), Vatican City, Bibliotheca Apostolica Vaticana, 2008, 2 volumes, LXXXVIII + 944 p., 47 ill. * Laharie (M.), "''Une cartographie ‘à la folie’'' : le journal d’Opicinus de Canistris", in '' Mélanges de l'École française de Rome (Moyen Âge)'', Ecole française de Rome, 119, 2, 2007, p. 361-399. * Morse, Victoria, A Complext Terrain: Church, Society and the Individual in the Thought of Opicino de Canistris. Unpublished dissertation completed at the University of California-Berkeley, 1996 * Morse, Victoria. “Seeing and Believing: The Problem of Idolatry in the Thought of Opicino de Canistris,” in. ''Orthodoxie, Christianisme, Histoire.'' (ed.) Susanna Elm, Eric Rebillard, and Antonella Romano. Ecole Francois de Rome, 2000 pp. 163-176 * Morse, Victoria. “The Vita Mediocris: The Secular Priesthood in the Thought of Opicino de Canistris,” in ''Quaderni di Storia Religiosa'' pp. 257-82 Verona, Cierre Edizione, 1994 * Piron, Sylvain. ''Dialectique du monstre. Enquête sur Opicino de Canistris'', Bruxelles, Zones sensibles, 2015, 208 p. * Roux (G.), ''Opicinus de Canistris'' (1296–1352), ''prêtre, pape et Christ ressuscité'', Paris, Le Léopard d’Or, 2005, 484 p. * Roux (G.), ''Opicinus de Canistris'' (1296–1352), ''Dieu fait homme et homme-Dieu'', Paris, Le Léopard d’Or, 2009, 310 p. * Roux (G.) & Laharie (M.), ''Art et Folie au Moyen Âge. Aventures et Énigmes d’Opicinus de Canistris'' (1296-1351 ?), Paris, Le Léopard d’Or, 1997, 364 p., 94 ill. * Salomon (R.G.), ''Opicinus de Canistris''. ''Weltbild und Bekenntnisse eines Avignonesichen Klerikers des 14. Jahrhunderts'', London, The Warburg Institute, 1936, 2 volumes; reprint. Lichtenstein, Kraus Reprints, 1969, 292 p. + 89 ill. * Tozzi (P.), ''Opicino e Pavia'', Pavia, Libreria d’Arte Cardano, 1990, 76 p. * Whittington, Karl. ''Body-Worlds: Opicinius de Canistris and the Medieval Cartographic Imagination''. Toronto, Pontifical Institute of Medieval Studies, 2014, xii + 212 p, 45 ill.External links

Cathedral of Pavia

from manuscript Vatican, Pal. Lat. 1993 in the website of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Visual Metaphysics: Opicinus de Canistris

by Nathan Schneider

at cartographic-images.net {{DEFAULTSORT:Opicinus De Canistris 14th-century Italian Roman Catholic priests Italian male writers 13th-century births 14th-century deaths