Operation Hurricane on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Operation Hurricane was the first test of a British atomic device. A

With the end of the war the

With the end of the war the

Implicit in the decision to develop atomic bombs was the need to test them. Lacking open, thinly-populated areas, British officials considered locations overseas. The preferred site was the American

Implicit in the decision to develop atomic bombs was the need to test them. Lacking open, thinly-populated areas, British officials considered locations overseas. The preferred site was the American  On 27 March 1951, Attlee sent Menzies a personal message saying that, while negotiations with the United States for use of the

On 27 March 1951, Attlee sent Menzies a personal message saying that, while negotiations with the United States for use of the

To coordinate the test, codenamed "Operation Hurricane", the British government established a Hurricane Executive Committee chaired by the Deputy Chief of the Naval Staff, , Vice Admiral

To coordinate the test, codenamed "Operation Hurricane", the British government established a Hurricane Executive Committee chaired by the Deputy Chief of the Naval Staff, , Vice Admiral  The next stage of work began in February 1952, in the wake of the December decision to proceed with the test. A detachment of No. 5 Airfield Construction Squadron was flown to Onslow from RAAF Bankstown in two RAAF

The next stage of work began in February 1952, in the wake of the December decision to proceed with the test. A detachment of No. 5 Airfield Construction Squadron was flown to Onslow from RAAF Bankstown in two RAAF  The British fleet was joined by eleven RAN ships, including the

The British fleet was joined by eleven RAN ships, including the

The original intention was that the scientists would stay on ''Campania'', commuting to the islands each day, but the survey party had misjudged the tides; ''Campania'' could not enter the lagoon, and had to anchor in the Parting Pool. The

The original intention was that the scientists would stay on ''Campania'', commuting to the islands each day, but the survey party had misjudged the tides; ''Campania'' could not enter the lagoon, and had to anchor in the Parting Pool. The

AWE history

Operation Hurricane

– Ministry of Supply made documentary * Better quality extract from the same video of th

Hurricane Nuclear Test

Operation Hurricane by National Archives of Australia

–

Declassified AWRE reports and National Archives files on Operation Hurricane's scientific and civil defence implications

{{Authority control

plutonium

Plutonium is a radioactive chemical element with the symbol Pu and atomic number 94. It is an actinide metal of silvery-gray appearance that tarnishes when exposed to air, and forms a dull coating when oxidized. The element normally exhibi ...

implosion device was detonated on 3 October 1952 in Main Bay, Trimouille Island, in the Montebello Islands

The Montebello Islands, also rendered as the Monte Bello Islands, are an archipelago of around 174 small islands (about 92 of which are named) lying north of Barrow Island (Western Australia), Barrow Island and off the Pilbara region of We ...

in Western Australia

Western Australia (commonly abbreviated as WA) is a state of Australia occupying the western percent of the land area of Australia excluding external territories. It is bounded by the Indian Ocean to the north and west, the Southern Ocean to th ...

. With the success of Operation Hurricane, Britain became the third nuclear power

Nuclear power is the use of nuclear reactions to produce electricity. Nuclear power can be obtained from nuclear fission, nuclear decay and nuclear fusion reactions. Presently, the vast majority of electricity from nuclear power is produced b ...

, after the United States and the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

.

During the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, Britain commenced a nuclear weapons project, code-named Tube Alloys

Tube Alloys was the research and development programme authorised by the United Kingdom, with participation from Canada, to develop nuclear weapons during the Second World War. Starting before the Manhattan Project in the United States, the Bri ...

, but the 1943 Quebec Agreement

The Quebec Agreement was a secret agreement between the United Kingdom and the United States outlining the terms for the coordinated development of the science and engineering related to nuclear energy and specifically nuclear weapons. It was s ...

merged it with the American Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

. Several key British scientists worked on the Manhattan Project, but after the war the American government ended cooperation on nuclear weapons. In January 1947, a cabinet sub-committee decided to resume British efforts to build nuclear weapons, in response to an apprehension of American isolationism and fears of Britain losing its great power

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power inf ...

status. The project was called High Explosive Research

High Explosive Research (HER) was the British project to develop atomic bombs independently after the Second World War. This decision was taken by a cabinet sub-committee on 8 January 1947, in response to apprehension of an American retur ...

, and was directed by Lord Portal, with William Penney

William George Penney, Baron Penney, (24 June 19093 March 1991) was an English mathematician and professor of mathematical physics at the Imperial College London and later the rector of Imperial College London. He had a leading role in the d ...

in charge of bomb design.

Implicit in the decision to develop atomic bomb

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bomb ...

s was the need to test them. The preferred site was the Pacific Proving Grounds

The Pacific Proving Grounds was the name given by the United States government to a number of sites in the Marshall Islands and a few other sites in the Pacific Ocean at which it conducted nuclear testing between 1946 and 1962. The U.S. tested a ...

in the US-controlled Marshall Islands

The Marshall Islands ( mh, Ṃajeḷ), officially the Republic of the Marshall Islands ( mh, Aolepān Aorōkin Ṃajeḷ),'' () is an independent island country and microstate near the Equator in the Pacific Ocean, slightly west of the Internati ...

. As a fallback, sites in Canada and Australia were considered. The Admiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

*Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

*Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

* Admiralty, Traf ...

suggested that the Montebello Islands might be suitable, so the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

The prime minister of the United Kingdom is the head of government of the United Kingdom. The prime minister advises the sovereign on the exercise of much of the royal prerogative, chairs the Cabinet and selects its ministers. As modern pr ...

, Clement Attlee

Clement Richard Attlee, 1st Earl Attlee, (3 January 18838 October 1967) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1945 to 1951 and Leader of the Labour Party from 1935 to 1955. He was Deputy Prime Mini ...

, sent a request to the Prime Minister of Australia

The prime minister of Australia is the head of government of the Commonwealth of Australia. The prime minister heads the executive branch of the Australian Government, federal government of Australia and is also accountable to Parliament of A ...

, Robert Menzies

The name Robert is an ancient Germanic given name, from Proto-Germanic "fame" and "bright" (''Hrōþiberhtaz''). Compare Old Dutch ''Robrecht'' and Old High German ''Hrodebert'' (a compound of ''Hrōþ, Hruod'' ( non, Hróðr) "fame, glory ...

. The Australian government formally agreed to the islands being used as a nuclear test site in May 1951. In February 1952, Attlee's successor, Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

, announced in the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

that the first British atomic bomb test would occur in Australia before the end of the year.

A small fleet was assembled for Operation Hurricane under the command of Rear Admiral

Rear admiral is a senior naval flag officer rank, equivalent to a major general and air vice marshal and above that of a commodore and captain, but below that of a vice admiral. It is regarded as a two star "admiral" rank. It is often regarde ...

A. D. Torlesse; it included the escort carrier

The escort carrier or escort aircraft carrier (U.S. hull classification symbol CVE), also called a "jeep carrier" or "baby flattop" in the United States Navy (USN) or "Woolworth Carrier" by the Royal Navy, was a small and slow type of aircraft ...

, which served as the flagship, and the LSTs ''Narvik'', ''Zeebrugge'' and ''Tracker''. Leonard Tyte from the Atomic Weapons Research Establishment at Aldermaston

Aldermaston is a village and civil parish in Berkshire, England. In the 2011 Census, the parish had a population of 1015. The village is in the Kennet Valley and bounds Hampshire to the south. It is approximately from Newbury, Basingstoke ...

was appointed the technical director. The bomb for Operation Hurricane was assembled (without its radioactive components) at Foulness

Foulness Island () is a closed island on the east coast of Essex in England, which is separated from the mainland by narrow creeks. In the 2001 census, the usually resident population of the civil parish was 212, living in the settlements of Ch ...

and taken to the frigate

A frigate () is a type of warship. In different eras, the roles and capabilities of ships classified as frigates have varied somewhat.

The name frigate in the 17th to early 18th centuries was given to any full-rigged ship built for speed and ...

for transport to Australia. On reaching the Montebello Islands, the five Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

ships were joined by eleven Royal Australian Navy

The Royal Australian Navy (RAN) is the principal naval force of the Australian Defence Force (ADF). The professional head of the RAN is Chief of Navy (CN) Vice Admiral Mark Hammond AM, RAN. CN is also jointly responsible to the Minister of ...

ships, including the aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and facilities for carrying, arming, deploying, and recovering aircraft. Typically, it is the capital ship of a fleet, as it allows a ...

. To test the effects of a ship-smuggled atomic bomb on a port (a threat of great concern to the British at the time), the bomb was exploded inside the hull of ''Plym'', anchored off Trimouille Island. The explosion occurred below the water line and left a saucer-shaped crater on the seabed deep and across.

Background

The December 1938 discovery ofnuclear fission

Nuclear fission is a reaction in which the nucleus of an atom splits into two or more smaller nuclei. The fission process often produces gamma photons, and releases a very large amount of energy even by the energetic standards of radio ...

by Otto Hahn

Otto Hahn (; 8 March 1879 – 28 July 1968) was a German chemist who was a pioneer in the fields of radioactivity and radiochemistry. He is referred to as the father of nuclear chemistry and father of nuclear fission. Hahn and Lise Meitner ...

and Fritz Strassmann

Friedrich Wilhelm Strassmann (; 22 February 1902 – 22 April 1980) was a German chemist who, with Otto Hahn in December 1938, identified the element barium as a product of the bombardment of uranium with neutrons. Their observation was the ke ...

—and its explanation and naming by Lise Meitner

Elise Meitner ( , ; 7 November 1878 – 27 October 1968) was an Austrian-Swedish physicist who was one of those responsible for the discovery of the element protactinium and nuclear fission. While working at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute on rad ...

and Otto Frisch—raised the possibility that an extremely powerful atomic bomb

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bomb ...

could be created. During the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, Frisch and Rudolf Peierls

Sir Rudolf Ernst Peierls, (; ; 5 June 1907 – 19 September 1995) was a German-born British physicist who played a major role in Tube Alloys, Britain's nuclear weapon programme, as well as the subsequent Manhattan Project, the combined Allied ...

at the University of Birmingham

, mottoeng = Through efforts to heights

, established = 1825 – Birmingham School of Medicine and Surgery1836 – Birmingham Royal School of Medicine and Surgery1843 – Queen's College1875 – Mason Science College1898 – Mason Univers ...

calculated the critical mass

In nuclear engineering, a critical mass is the smallest amount of fissile material needed for a sustained nuclear chain reaction. The critical mass of a fissionable material depends upon its nuclear properties (specifically, its nuclear fissi ...

of a metallic sphere of pure uranium-235

Uranium-235 (235U or U-235) is an isotope of uranium making up about 0.72% of natural uranium. Unlike the predominant isotope uranium-238, it is fissile, i.e., it can sustain a nuclear chain reaction. It is the only fissile isotope that exis ...

, and found that instead of tonnes, as everyone had assumed, as little as would suffice, which would explode with the power of thousands of tonnes of dynamite. In response, Britain initiated an atomic bomb project, codenamed Tube Alloys

Tube Alloys was the research and development programme authorised by the United Kingdom, with participation from Canada, to develop nuclear weapons during the Second World War. Starting before the Manhattan Project in the United States, the Bri ...

.

At the Quebec Conference in August 1943, the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

The prime minister of the United Kingdom is the head of government of the United Kingdom. The prime minister advises the sovereign on the exercise of much of the royal prerogative, chairs the Cabinet and selects its ministers. As modern pr ...

, Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

, and the President of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United Stat ...

, Franklin Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

, signed the Quebec Agreement

The Quebec Agreement was a secret agreement between the United Kingdom and the United States outlining the terms for the coordinated development of the science and engineering related to nuclear energy and specifically nuclear weapons. It was s ...

, which merged Tube Alloys with the American Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

to create a combined British, American and Canadian project. The British contribution to the Manhattan Project

Britain contributed to the Manhattan Project by helping initiate the effort to build the first atomic bombs in the United States during World War II, and helped carry it through to completion in August 1945 by supplying crucial expertise. Follo ...

included assistance in the development of gaseous diffusion

Gaseous diffusion is a technology used to produce enriched uranium by forcing gaseous uranium hexafluoride (UF6) through semipermeable membranes. This produces a slight separation between the molecules containing uranium-235 (235U) and uranium-2 ...

technology at the SAM Laboratories in New York, and the electromagnetic separation

Isotope separation is the process of concentrating specific isotopes of a chemical element by removing other isotopes. The use of the nuclides produced is varied. The largest variety is used in research (e.g. in chemistry where atoms of "marker" n ...

process at the Berkeley Radiation Laboratory. John Cockcroft

Sir John Douglas Cockcroft, (27 May 1897 – 18 September 1967) was a British physicist who shared with Ernest Walton the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1951 for splitting the atomic nucleus, and was instrumental in the development of nuclea ...

became the director of the joint British-Canadian Montreal Laboratory

The Montreal Laboratory in Montreal, Quebec, Canada, was established by the National Research Council of Canada during World War II to undertake nuclear research in collaboration with the United Kingdom, and to absorb some of the scientists and ...

. A British mission to the Los Alamos Laboratory

The Los Alamos Laboratory, also known as Project Y, was a secret laboratory established by the Manhattan Project and operated by the University of California during World War II. Its mission was to design and build the first atomic bombs. Ro ...

led by James Chadwick

Sir James Chadwick, (20 October 1891 – 24 July 1974) was an English physicist who was awarded the 1935 Nobel Prize in Physics for his discovery of the neutron in 1932. In 1941, he wrote the final draft of the MAUD Report, which inspi ...

, and later Peierls, included scientists such as Geoffrey Taylor, James Tuck, Niels Bohr

Niels Henrik David Bohr (; 7 October 1885 – 18 November 1962) was a Danish physicist who made foundational contributions to understanding atomic structure and quantum theory, for which he received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1922. B ...

, William Penney

William George Penney, Baron Penney, (24 June 19093 March 1991) was an English mathematician and professor of mathematical physics at the Imperial College London and later the rector of Imperial College London. He had a leading role in the d ...

, Frisch, Ernest Titterton

Sir Ernest William Titterton (4 March 1916 – 8 February 1990) was a British nuclear physicist.

A graduate of the University of Birmingham, Titterton worked in a research position under Mark Oliphant, who recruited him to work on radar ...

, and Klaus Fuchs, who was later revealed to be a spy for the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

. As overall head of the British Mission, Chadwick forged a close and successful partnership with Brigadier General

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

Leslie R. Groves, the director of the Manhattan Project, and ensured that British participation was complete and wholehearted.

With the end of the war the

With the end of the war the Special Relationship

The Special Relationship is a term that is often used to describe the politics, political, social, diplomacy, diplomatic, culture, cultural, economics, economic, law, legal, Biophysical environment, environmental, religion, religious, military ...

between Britain and the United States "became very much less special". The British government had trusted that America would share nuclear technology, which the British saw as a joint discovery, but the terms of the Quebec Agreement remained secret. Senior members of the United States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is bicameral, composed of a lower body, the House of Representatives, and an upper body, the Senate. It meets in the U.S. Capitol in Washing ...

were horrified when they discovered that it gave the British a veto over the use of nuclear weapons. On 9 November 1945, the new Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, Clement Attlee

Clement Richard Attlee, 1st Earl Attlee, (3 January 18838 October 1967) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1945 to 1951 and Leader of the Labour Party from 1935 to 1955. He was Deputy Prime Mini ...

, and the Prime Minister of Canada

The prime minister of Canada (french: premier ministre du Canada, link=no) is the head of government of Canada. Under the Westminster system, the prime minister governs with the Confidence and supply, confidence of a majority the elected Hou ...

, William Lyon Mackenzie King

William Lyon Mackenzie King (December 17, 1874 – July 22, 1950) was a Canadian statesman and politician who served as the tenth prime minister of Canada for three non-consecutive terms from 1921 to 1926, 1926 to 1930, and 1935 to 1948. A Li ...

, went to Washington, DC, to confer with Truman about future cooperation in nuclear weapons and nuclear power. They signed a Memorandum of Intention that replaced the Quebec Agreement. It made Canada a full partner, and reduced the obligation to obtain consent for the use of nuclear weapons to merely requiring consultation. The three leaders agreed that there would be full and effective cooperation on civil and military applications of atomic energy, but the British were soon disappointed; the Americans made it clear that cooperation was restricted to basic scientific research. The Atomic Energy Act of 1946

The Atomic Energy Act of 1946 (McMahon Act) determined how the United States would control and manage the nuclear technology it had jointly developed with its World War II allies, the United Kingdom and Canada. Most significantly, the Act rule ...

(McMahon

McMahon, also spelled MacMahon (older Irish orthography: ; reformed Irish orthography: ), is a surname of Irish origin. It is derived from the Gaelic ''Mac'' ''Mathghamhna'' meaning 'son of the bear'.

The surname came into use around the 11th c ...

Act) ended technical cooperation. Its control of "restricted data" prevented the United States' allies from receiving any information.

Attlee set up a cabinet sub-committee, the Gen 75 Committee

The Gen 75 Committee was a committee of the British cabinet, convened by the Prime Minister, Clement Attlee, on 10 August 1945. It was one of many ''ad hoc'' cabinet committees, each of which was convened to handle a single issue, and given a ...

(known informally as the "Atomic Bomb Committee"), on 10 August 1945 to examine the feasibility of a nuclear weapons program. In October 1945, it accepted a recommendation that responsibility be placed within the Ministry of Supply

The Ministry of Supply (MoS) was a department of the UK government formed in 1939 to co-ordinate the supply of equipment to all three British armed forces, headed by the Minister of Supply. A separate ministry, however, was responsible for aircr ...

. The Tube Alloys Directorate was transferred from the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research Department of Scientific and Industrial Research, abbreviated DSIR was the name of several British Empire organisations founded after the 1923 Imperial Conference to foster intra-Empire trade and development.

* Department of Scientific and Industria ...

to the Ministry of Supply on 1 November 1945. To coordinate the effort, Lord Portal, the wartime Chief of the Air Staff, was appointed Controller of Production, Atomic Energy (CPAE), with direct access to the Prime Minister. An Atomic Energy Research Establishment

The Atomic Energy Research Establishment (AERE) was the main Headquarters, centre for nuclear power, atomic energy research and development in the United Kingdom from 1946 to the 1990s. It was created, owned and funded by the British Governm ...

(AERE) was established at RAF Harwell

Royal Air Force Harwell or more simply RAF Harwell is a former Royal Air Force station, near the village of Harwell, located south east of Wantage, Oxfordshire and north west of Reading, Berkshire, England.

The site is now the Harwell Sc ...

, south of Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

, under the directorship of Cockcroft. AERE moved to Aldermaston

Aldermaston is a village and civil parish in Berkshire, England. In the 2011 Census, the parish had a population of 1015. The village is in the Kennet Valley and bounds Hampshire to the south. It is approximately from Newbury, Basingstoke ...

in 1952. Christopher Hinton agreed to oversee the design, construction and operation of the new atomic weapons facilities. These included a new uranium plant at Springfields

Springfields is a nuclear fuel production installation in Salwick, near Preston in Lancashire, England (). The site is currently operated by Springfields Fuels Limited, under the management of Westinghouse Electric UK Limited, on a 150-year l ...

in Lancashire

Lancashire ( , ; abbreviated Lancs) is the name of a historic county, ceremonial county, and non-metropolitan county in North West England. The boundaries of these three areas differ significantly.

The non-metropolitan county of Lancashi ...

, and nuclear reactor

A nuclear reactor is a device used to initiate and control a fission nuclear chain reaction or nuclear fusion reactions. Nuclear reactors are used at nuclear power plants for electricity generation and in nuclear marine propulsion. Heat from nu ...

s and plutonium

Plutonium is a radioactive chemical element with the symbol Pu and atomic number 94. It is an actinide metal of silvery-gray appearance that tarnishes when exposed to air, and forms a dull coating when oxidized. The element normally exhibi ...

processing facilities at Windscale

Sellafield is a large multi-function nuclear site close to Seascale on the coast of Cumbria, England. As of August 2022, primary activities are nuclear waste storage, nuclear waste processing and storage and nuclear decommissioning. Former act ...

in Cumbria

Cumbria ( ) is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in North West England, bordering Scotland. The county and Cumbria County Council, its local government, came into existence in 1974 after the passage of the Local Government Act 1972. Cumb ...

. Hinton established his headquarters in a former Royal Ordnance Factory

Royal Ordnance Factories (ROFs) was the collective name of the UK government's munitions factories during and after the Second World War. Until privatisation, in 1987, they were the responsibility of the Ministry of Supply, and later the Ministr ...

at Risley in Lancashire on 4 February 1946.

In July 1946, the Chiefs of Staff Committee

The Chiefs of Staff Committee (CSC) is composed of the most senior military personnel in the British Armed Forces who advise on operational military matters and the preparation and conduct of military operations. The committee consists of the Ch ...

recommended that Britain acquire nuclear weapons. They estimated that 200 bombs would be required by 1957. Despite this, and the research and construction of production facilities that had already been approved, there was still no official decision to proceed with making atomic bombs. Portal submitted a proposal to do so at the 8 January 1947 meeting of the Gen 163 Committee, a subcommittee of the Gen 75 Committee, which agreed to proceed with the development of atomic bombs. It also endorsed his proposal to place Penney, now the Chief Superintendent Armament Research (CSAR) at Fort Halstead

Fort Halstead was a research site of Dstl, an executive agency of the UK Ministry of Defence. It is situated on the crest of the Kentish North Downs, overlooking the town of Sevenoaks, southeast of London. Originally constructed in 1892 as part ...

in Kent, in charge of the bomb development effort, which was codenamed High Explosive Research

High Explosive Research (HER) was the British project to develop atomic bombs independently after the Second World War. This decision was taken by a cabinet sub-committee on 8 January 1947, in response to apprehension of an American retur ...

. Penney contended that "the discriminative test for a first-class power is whether it has made an atomic bomb and we have either got to pass the test or suffer a serious loss of prestige both inside this country and internationally."

Although the British government had committed to the development of an independent nuclear deterrent, it still hoped for a restoration of the nuclear Special Relationship with the Americans. It was therefore important that nothing be done that would jeopardise this.

Site selection

Implicit in the decision to develop atomic bombs was the need to test them. Lacking open, thinly-populated areas, British officials considered locations overseas. The preferred site was the American

Implicit in the decision to develop atomic bombs was the need to test them. Lacking open, thinly-populated areas, British officials considered locations overseas. The preferred site was the American Pacific Proving Grounds

The Pacific Proving Grounds was the name given by the United States government to a number of sites in the Marshall Islands and a few other sites in the Pacific Ocean at which it conducted nuclear testing between 1946 and 1962. The U.S. tested a ...

. A request to use it was sent to the American Joint Chiefs of Staff

The Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) is the body of the most senior uniformed leaders within the United States Department of Defense, that advises the president of the United States, the secretary of defense, the Homeland Security Council and the ...

in 1949. In October 1950 the Americans turned down the request. As a fallback, sites in Canada and Australia were considered. Penney spoke to Omond Solandt

Omond McKillop Solandt, (September 25, 1909 – May 12, 1993) was a Canadian scientist who was the first Chairman of the Canadian Defence Research Board.

Early life

Born in Winnipeg, Manitoba, he graduated in medicine from the University of T ...

, the chairman of the Canadian Defence Research Board

Defence Research and Development Canada (DRDC; french: Recherche et développement pour la défense Canada, ''RDDC'') is a special operating agency of the Department of National Defence (DND), whose purpose is to provide the Canadian Armed Forces ...

, and they arranged for a joint feasibility study.

The study noted several requirements for a test area:

* an isolated area with no human habitation downwind;

* large enough to accommodate a dozen detonations over a period of several years;

* with prevailing winds that would blow fallout

Nuclear fallout is the residual radioactive material propelled into the upper atmosphere following a nuclear blast, so called because it "falls out" of the sky after the explosion and the shock wave has passed. It commonly refers to the radioac ...

out to sea but away from shipping lanes;

* a temporary camp site at least upwind of the detonation area;

* a base camp site at least upwind of the detonation area, with room for laboratories, workshops and signals equipment;

* ready for use by mid-1952.

The first test would probably be a ground burst, but consideration was also given to an explosion in a ship to measure the effect of a ship-borne atomic bomb on a major port. Such data would complement that obtained about an underwater explosion by the American Operation Crossroads

Operation Crossroads was a pair of nuclear weapon tests conducted by the United States at Bikini Atoll in mid-1946. They were the first nuclear weapon tests since Trinity in July 1945, and the first detonations of nuclear devices since the ...

nuclear test in 1946, and would therefore be of value to the Americans. Seven Canadian sites were assessed, the most promising being Churchill, Manitoba

Churchill is a town in northern Manitoba, Canada, on the west shore of Hudson Bay, roughly from the Manitoba–Nunavut border. It is most famous for the many polar bears that move toward the shore from inland in the autumn, leading to the nickname ...

, but the waters were too shallow to allow ships to approach close to shore.

In September 1950, the Admiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

*Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

*Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

* Admiralty, Traf ...

suggested that the uninhabited Montebello Islands

The Montebello Islands, also rendered as the Monte Bello Islands, are an archipelago of around 174 small islands (about 92 of which are named) lying north of Barrow Island (Western Australia), Barrow Island and off the Pilbara region of We ...

in Australia might be suitable, so Attlee obtained permission from the Prime Minister of Australia

The prime minister of Australia is the head of government of the Commonwealth of Australia. The prime minister heads the executive branch of the Australian Government, federal government of Australia and is also accountable to Parliament of A ...

, Robert Menzies, to send a survey party to look at the islands, which are about and from Onslow. Major General James Cassels, the Chief Liaison Officer with the United Kingdom Services Liaison Staff (UKSLS) in Melbourne

Melbourne ( ; Boonwurrung/Woiwurrung: ''Narrm'' or ''Naarm'') is the capital and most populous city of the Australian state of Victoria, and the second-most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Its name generally refers to a met ...

, was designated the principal British contact in Australia, and Menzies nominated Sir Frederick Shedden

Sir Frederick Geoffrey Shedden (8 August 1893 – 8 July 1971) was an Australian public servant who served as Secretary of the Department of Defence from 1937 to 1956.

Background and early life

Frederick Shedden was born 8 August 1893 in Kyne ...

, the Secretary

A secretary, administrative professional, administrative assistant, executive assistant, administrative officer, administrative support specialist, clerk, military assistant, management assistant, office secretary, or personal assistant is a w ...

of the Department of Defence Department of Defence or Department of Defense may refer to:

Current departments of defence

* Department of Defence (Australia)

* Department of National Defence (Canada)

* Department of Defence (Ireland)

* Department of National Defense (Philipp ...

, as the person with whom Cassels should deal.

At the time Britain was still Australia's largest trading partner; it would be overtaken by Japan and the United States by the 1960s. Britain and Australia had strong cultural ties, and Menzies was strongly pro-British. Most Australians were of British descent, and Britain was still the largest source of immigrants to Australia, largely because British ex-servicemen and their families qualified for free passage, and other British migrants received subsidised passage. Australian and British troops were fighting communist forces together in the Korean War

, date = {{Ubl, 25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953 (''de facto'')({{Age in years, months, weeks and days, month1=6, day1=25, year1=1950, month2=7, day2=27, year2=1953), 25 June 1950 – present (''de jure'')({{Age in years, months, weeks a ...

and the Malayan Emergency

The Malayan Emergency, also known as the Anti–British National Liberation War was a guerrilla war fought in British Malaya between communist pro-independence fighters of the Malayan National Liberation Army (MNLA) and the military forces o ...

. Australia still maintained close defence ties with Britain through the Australia New Zealand and Malaya (ANZAM) area, which was created in 1948. Australian war plans of this era continued to be closely integrated with those of Britain, and involved reinforcing the British forces in the Middle East and Far East.

Australia was particularly interested in developing atomic energy Atomic energy or energy of atoms is energy carried by atoms. The term originated in 1903 when Ernest Rutherford began to speak of the possibility of atomic energy.Isaac Asimov, ''Atom: Journey Across the Sub-Atomic Cosmos'', New York:1992 Plume, ...

as the country was then thought to have no oil and only limited supplies of coal. Plans for atomic power were considered along with hydroelectricity

Hydroelectricity, or hydroelectric power, is Electricity generation, electricity generated from hydropower (water power). Hydropower supplies one sixth of the world's electricity, almost 4500 TWh in 2020, which is more than all other Renewabl ...

as part of the post-war Snowy Mountains Scheme

The Snowy Mountains Scheme or Snowy scheme is a hydroelectricity and irrigation complex in south-east Australia. The Scheme consists of sixteen major dams; nine power stations; two pumping stations; and of tunnels, pipelines and aqueducts that ...

. There was also interest in the production of uranium-235 and plutonium for nuclear weapons. The Australian government had hopes of collaboration with Britain on nuclear energy and nuclear weapons, but the 1948 ''Modus Vivendi'' cut Australian scientists off from information they had formerly had access to. Unlike Canada, Australia was not a party to the Quebec Agreement or the ''Modus Vivendi''. Britain would not share technical information with Australia for fear that it might jeopardise its far more important relationship with the United States, and the Americans were reluctant to share secret information with Australia after the Venona project

The Venona project was a United States counterintelligence program initiated during World War II by the United States Army's Signal Intelligence Service (later absorbed by the National Security Agency), which ran from February 1, 1943, until Octob ...

revealed the extent of Soviet espionage activities in Australia. The creation of NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two No ...

in 1949 excluded Australia from the Western Alliance.

The three-man survey party, headed by Air Vice Marshal

Air vice-marshal (AVM) is a two-star air officer rank which originated in and continues to be used by the Royal Air Force. The rank is also used by the air forces of many countries which have historical British influence and it is sometimes u ...

E. D. Davis, arrived in Sydney on 1 November 1950, and embarked on , under the command of Commander A. H. Cooper, who carried out a detailed hydrographic survey of the islands. The charts at the Admiralty had been made by in August 1840. Soundings were taken of the depths of coastal waters to measure the tides, and samples of the gravel and sand were taken to assess whether they could be used for making concrete. The work afloat and ashore was complemented by Royal Australian Air Force

"Through Adversity to the Stars"

, colours =

, colours_label =

, march =

, mascot =

, anniversaries = RAAF Anniversary Commemoration ...

(RAAF) aerial photography of the islands. The British survey team returned to London on 29 November 1950. The islands were assessed as suitable for atomic testing, but, for climatic reasons, only in October.

On 27 March 1951, Attlee sent Menzies a personal message saying that, while negotiations with the United States for use of the

On 27 March 1951, Attlee sent Menzies a personal message saying that, while negotiations with the United States for use of the Nevada Test Site

The Nevada National Security Site (N2S2 or NNSS), known as the Nevada Test Site (NTS) until 2010, is a United States Department of Energy (DOE) reservation located in southeastern Nye County, Nevada, about 65 miles (105 km) northwest of th ...

were ongoing, work would need to begin if the Montebello Islands were to be used in October 1952. Menzies replied that he could not authorise the test until after the Australian federal election

Elections in Australia take place periodically to elect the legislature of the Commonwealth of Australia, as well as for each Australian state and territory and for local government councils. Elections in all jurisdictions follow similar princi ...

, to be held on 28 April 1951, but was willing to allow work to continue. Menzies was re-elected, and the Australian government formally agreed in May 1951. On 28 May, Attlee sent a comprehensive list of assistance that it hoped that Australia would provide. A more detailed survey was requested, which was carried out by in July and August 1951. The British government emphasised the importance of security, so as not to imperil its negotiations with the United States. The Australian government gave all weapon design data a classification Classification is a process related to categorization, the process in which ideas and objects are recognized, differentiated and understood.

Classification is the grouping of related facts into classes.

It may also refer to:

Business, organizat ...

of "Top Secret", other aspects of the test being "Classified". Nuclear weapons design was already covered by a D notice

In the United Kingdom, a DSMA-Notice (Defence and Security Media Advisory Notice) is an official request to news editors not to publish or broadcast items on specified subjects for reasons of national security. DSMA-Notices were formerly called a ...

in the United Kingdom. Australian D Notice No. 8 was issued to cover nuclear tests.

Meanwhile, negotiations continued with the Americans. Oliver Franks

Oliver Shewell Franks, Baron Franks (16 February 1905 – 15 October 1992) was an English civil servant and philosopher who has been described as 'one of the founders of the postwar world'.

Franks was involved in Britain's recovery after the S ...

, the British Ambassador to the United States

The British Ambassador to the United States is in charge of the British Embassy, Washington, D.C., the United Kingdom's diplomatic mission to the United States. The official title is His Majesty's Ambassador to the United States of America.

T ...

, lodged a formal request on 2 August 1951 for use of the Nevada Test Site. This was looked upon favourably by the United States Secretary of State, Dean Acheson

Dean Gooderham Acheson (pronounced ; April 11, 1893October 12, 1971) was an American statesman and lawyer. As the 51st U.S. Secretary of State, he set the foreign policy of the Harry S. Truman administration from 1949 to 1953. He was also Truman ...

, and the chairman of the United States Atomic Energy Commission

The United States Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) was an agency of the United States government established after World War II by U.S. Congress to foster and control the peacetime development of atomic science and technology. President H ...

, Gordon Dean, but opposed by Robert A. Lovett

Robert Abercrombie Lovett (September 14, 1895May 7, 1986) was the fourth United States Secretary of Defense, having been promoted to this position from Deputy Secretary of Defense. He served in the cabinet of President Harry S. Truman from 1951 ...

, the American Deputy Secretary of Defense

The deputy secretary of defense (acronym: DepSecDef) is a statutory office () and the second-highest-ranking official in the Department of Defense of the United States of America.

The deputy secretary is the principal civilian deputy to the se ...

and Robert LeBaron, the Deputy Secretary of Defence for Atomic Energy Affairs. The British government had announced on 7 June 1951 that Donald Maclean, who had served as a British member of the Combined Policy Committee from January 1947 to August 1948, had been a Soviet spy. In view of security concerns, Lovett and LeBaron wanted the tests to be conducted by Americans, British participation being limited to Penney and a few selected British scientists. Truman endorsed this counterproposal on 24 September 1951.

The Nevada Test Site would be cheaper than Montebello, although the cost would be paid in scarce dollars. Information gathered would have to be shared with the Americans, who would not share their own data. It would not be possible to test from a ship, and the political advantages in demonstrating that Britain could develop and test nuclear weapons without American assistance would be foregone. The Americans were under no obligation to make the test site available for subsequent tests. Also, as Lord Cherwell

Frederick Alexander Lindemann, 1st Viscount Cherwell, ( ; 5 April 18863 July 1957) was a British physicist who was prime scientific adviser to Winston Churchill in World War II.

Lindemann was a brilliant intellectual, who cut through bureauc ...

noted, an American test meant that "in the lamentable event of the bomb failing to detonate, we should look very foolish indeed."

A final decision was deferred until after the UK's 1951 election. This resulted in a change of government, the Conservative Party

The Conservative Party is a name used by many political parties around the world. These political parties are generally right-wing though their exact ideologies can range from center-right to far-right.

Political parties called The Conservative P ...

returning to power and Churchill replacing Attlee as Prime Minister. On 27 December 1951, the High Commissioner of the United Kingdom to Australia informed Menzies of the British government's decision to use Montebello. On 26 February 1952, Churchill announced in the House of Commons that the first British atomic bomb test would occur in Australia before the end of the year. When queried by a UK Labour Party backbencher, Emrys Hughes

Emrys Daniel Hughes (10 July 1894 – 18 October 1969) was a Welsh Labour Party politician, journalist and author. He was Labour MP for South Ayrshire in Scotland from 1946 to 1969. Among his many published books was a biography of his father ...

, about the impact on the local flora and fauna, Churchill joked that the survey team had only seen some birds and lizards. Among the AERE scientists was an amateur biologist, Frank Hill, who collected samples of the flora and fauna on the islands, teaming up with Commander G. Wedd, who collected marine specimens from the surrounding waters. In a paper published by the Linnean Society of London

The Linnean Society of London is a learned society dedicated to the study and dissemination of information concerning natural history, evolution, and taxonomy. It possesses several important biological specimen, manuscript and literature colle ...

, Hill catalogued over 400 species of plants and animals. This included 20 new species of insects, six of plants, and a new species of legless lizard

Legless lizard may refer to any of several groups of lizards that have independently lost limbs or reduced them to the point of being of no use in locomotion.Pough ''et al.'' 1992. Herpetology: Third Edition. Pearson Prentice Hall:Pearson Education ...

.

Preparations

To coordinate the test, codenamed "Operation Hurricane", the British government established a Hurricane Executive Committee chaired by the Deputy Chief of the Naval Staff, , Vice Admiral

To coordinate the test, codenamed "Operation Hurricane", the British government established a Hurricane Executive Committee chaired by the Deputy Chief of the Naval Staff, , Vice Admiral Edward Evans-Lombe

Vice-Admiral Sir Edward Malcolm Evans-Lombe KCB (15 October 1901 – 14 May 1974) was a Royal Navy officer who became Deputy Chief of the Naval Staff.

Naval career

Educated at West Downs School and in the Royal Navy, Evans-Lombe served in th ...

. It held its first meeting in May 1951. To deal with it, an Australian Hurricane Panel was created, chaired by the Australian Deputy Chief of the Naval Staff, Captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

Alan McNicoll

Vice Admiral Sir Alan Wedel Ramsay McNicoll, (3 April 1908 – 11 October 1987) was a senior officer in the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) and a diplomat. Born in Melbourne, he entered the Royal Australian Naval College at the age of thirte ...

. Its other members were Colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge of ...

John Wilton from the Australian Army

The Australian Army is the principal Army, land warfare force of Australia, a part of the Australian Defence Force (ADF) along with the Royal Australian Navy and the Royal Australian Air Force. The Army is commanded by the Chief of Army (Austral ...

, Group Captain

Group captain is a senior commissioned rank in the Royal Air Force, where it originated, as well as the air forces of many countries that have historical British influence. It is sometimes used as the English translation of an equivalent rank i ...

Alister Murdoch

Air Marshal Sir Alister Murray Murdoch, (9 December 1912 – 24 October 1984) was a senior commander in the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF). He served as Chief of the Air Staff (CAS) from 1965 to 1969. Joining the Air Force ...

from the RAAF and Charles Spry

Brigadier Sir Charles Chambers Fowell Spry (26 June 1910 – 28 May 1994) was an Australian soldier and public servant. From 1950 to 1970 he was the second Director-General of Security, the head of the Australian Security Intelligence Organisati ...

from Australian Security Intelligence Organisation

The Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO ) is Australia's national security agency responsible for the protection of the country and its citizens from espionage, sabotage, acts of foreign interference, politically motivated vio ...

(ASIO). Cassels or his representative was invited to attend its meetings. A pressing question was that of observers. Churchill decided to exclude the media and members of the UK parliament. As Canada was a party to the 1948 ''Modus Vivendi'', Canadian scientists and technicians would have access to all technical data, but Australians would not.

Penney was anxious to secure the services of Titterton, who had recently emigrated to Australia, as he had worked on the American Trinity

The Christian doctrine of the Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the central dogma concerning the nature of God in most Christian churches, which defines one God existing in three coequal, coeternal, consubstantial divine persons: God the F ...

and Crossroads tests. Menzies asked the vice-chancellor of the Australian National University

The Australian National University (ANU) is a public research university located in Canberra, the capital of Australia. Its main campus in Acton encompasses seven teaching and research colleges, in addition to several national academies and ...

, Sir Douglas Copland

Sir Douglas Berry Copland (24 February 189427 September 1971) was an Australian academic and economist.

Biography

Douglas Copland was born in Otago, New Zealand in 1894, the thirteenth of sixteen children. He was raised there and lived there ...

, to release Titterton to work on Operation Hurricane. Cockcroft also wanted assistance from Leslie Martin

Sir John Leslie Martin (17 August 1908, in Manchester – 28 July 2000) was an English architect, and a leading advocate of the International Style. Martin's most famous building is the Royal Festival Hall. His work was especially influenced ...

, the Department of Defence's Science Advisor, who was also a professor of physics at the University of Melbourne

The University of Melbourne is a public research university located in Melbourne, Australia. Founded in 1853, it is Australia's second oldest university and the oldest in Victoria. Its main campus is located in Parkville, an inner suburb nor ...

, to work in the health physics area. The two men knew each other from their time at Cambridge University

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

before the war. After some argument, Martin was accepted as an official observer, as was W. A. S. Butement, the Chief Scientist at the Department of Supply

The Department of Supply was an Australian government department that existed between March 1950 and June 1974.

History

Established in 1950, the Department of Supply headquarters transferred to Canberra in January 1968.

In 1964 the ...

. The only other official observer was Solandt from Canada.

An advance party of No. 5 Airfield Construction Squadron from RAAF Base Williamtown

RAAF Base Williamtown is a Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) military air base located north of the coastal city of Newcastle ( by road) in the local government area of Port Stephens, in New South Wales, Australia. The base serves as the h ...

, New South Wales, moved to Onslow in August 1951 with heavy construction equipment, taking the train to Geraldton

Geraldton (Wajarri: ''Jambinu'', Wilunyu: ''Jambinbirri'') is a coastal city in the Mid West region of the Australian state of Western Australia, north of the state capital, Perth.

At June 2018, Geraldton had an urban population of 37,648. ...

and then the road to Onslow. This was then transported to the Montebello Islands. A prefabricated hut was taken across by ''Karangai'', along with equipment for establishing a meteorological station. Other materiel was moved from Onslow to the islands in lots in an ALC-40 landing craft manned by the Australian Army and towed by ''Karangai''. This included two bulldozer

A bulldozer or dozer (also called a crawler) is a large, motorized machine equipped with a metal blade to the front for pushing material: soil, sand, snow, rubble, or rock during construction work. It travels most commonly on continuous track ...

s, a grader

A grader, also commonly referred to as a road grader, motor grader, or simply a blade, is a form of heavy equipment with a long blade used to create a flat surface during grading. Although the earliest models were towed behind horses, and lat ...

, tip trucks, portable generator

An engine–generator is the combination of an electrical generator and an engine (prime mover) mounted together to form a single piece of equipment. This combination is also called an ''engine–generator set'' or a ''gen-set''. In many contexts ...

s, water tank

A water tank is a container for storing water.

Water tanks are used to provide storage of water for use in many applications, drinking water, irrigation agriculture, fire suppression, agricultural farming, both for plants and livestock, chemi ...

s and a mobile radio transceiver

In radio communication, a transceiver is an electronic device which is a combination of a radio ''trans''mitter and a re''ceiver'', hence the name. It can both transmit and receive radio waves using an antenna, for communication purposes. The ...

. The hut was erected, and the meteorological station henceforth manned by an RAAF officer and four assistants. Roads and landings were constructed, and camp sites established.

The next stage of work began in February 1952, in the wake of the December decision to proceed with the test. A detachment of No. 5 Airfield Construction Squadron was flown to Onslow from RAAF Bankstown in two RAAF

The next stage of work began in February 1952, in the wake of the December decision to proceed with the test. A detachment of No. 5 Airfield Construction Squadron was flown to Onslow from RAAF Bankstown in two RAAF Dakota

Dakota may refer to:

* Dakota people, a sub-tribe of the Sioux

** Dakota language, their language

Dakota may also refer to:

Places United States

* Dakota, Georgia, an unincorporated community

* Dakota, Illinois, a town

* Dakota, Minnesota, ...

aircraft, and were then taken to the islands by the ''Bathurst''-class corvette . ''Karangai'' fetched of Marston Mat

Marston Mat, more properly called pierced (or perforated) steel planking (PSP), is standardized, perforated steel matting material developed by the United States at the Waterways Experiment Station shortly before World War II, primarily for the ...

from Darwin that was used for road works and hardstand

A hardstand (also hard standing and hardstanding in British English) is a paved or hard-surfaced area on which vehicles, such as cars or aircraft, may be parked. The term may also be used informally to refer to an area of compacted hard surface suc ...

s. The SS ''Dorrigo'' brought in another three weeks later. A water supply was also developed. To bring water from the Fortescue River

The Fortescue River is an ephemeral river in the Pilbara region of Western Australia. It is the third longest river in the state.

Course

The river rises near Deadman Hill in the Ophthalmia Range about 30 km south of Newman. The river flo ...

, a quantity of Victaulic

Victaulic is a developer and manufacturer of mechanical pipe joining systems, and the originator of the grooved pipe couplings joining system. The firm is a global company with 15 major manufacturing facilities, 28 branches, and over 3600 emplo ...

-coupling pipe was brought from the Department of Works in Sydney and the Woomera Rocket Range

The RAAF Woomera Range Complex (WRC) is a major Australian military and civil aerospace facility and operation located in South Australia, approximately north-west of Adelaide. The WRC is operated by the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF), a di ...

in South Australia. Because the pipe was laid around obstacles, this proved to be insufficient. No more pipe was in storage, so a firm in Melbourne was asked to make some. An order was placed on a Friday evening, and the pipe was shipped the following Thursday morning, making its way to the Fortescue River by road and rail. The system delivered up to per hour to a jetty on the Fortescue estuary, from which it was taken to the islands by the 120ft Motor Lighter ''MWL 251''.

The British assembled a small fleet for Operation Hurricane that included the escort carrier

The escort carrier or escort aircraft carrier (U.S. hull classification symbol CVE), also called a "jeep carrier" or "baby flattop" in the United States Navy (USN) or "Woolworth Carrier" by the Royal Navy, was a small and slow type of aircraft ...

, which served as the flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically the fi ...

, and the LSTs ''Narvik'', ''Zeebrugge'' and ''Tracker'', under the command of Rear Admiral

Rear admiral is a senior naval flag officer rank, equivalent to a major general and air vice marshal and above that of a commodore and captain, but below that of a vice admiral. It is regarded as a two star "admiral" rank. It is often regarde ...

A. D. Torlesse. Leonard Tyte from the AERE was appointed the technical director. ''Campania'' had five aircraft embarked, three Westland WS-51 Dragonfly

The Westland WS-51 Dragonfly helicopter was built by Westland Aircraft and was an Anglicised licence-built version of the American Sikorsky S-51.

Design and development

On 19 January 1947 an agreement was signed between Westland Aircraft an ...

helicopters and two Supermarine Sea Otter

The Supermarine Sea Otter was an amphibious aircraft designed and built by the British aircraft manufacturer Supermarine. It was the final biplane flying boat to be designed by Supermarine; it was also the last biplane to enter service with bot ...

amphibians

Amphibians are four-limbed and ectothermic vertebrates of the class Amphibia. All living amphibians belong to the group Lissamphibia. They inhabit a wide variety of habitats, with most species living within terrestrial, fossorial, arbore ...

. Between them, the LSTs carried five LCMs and twelve LCAs Link Capacity Adjustment Scheme or LCAS is a method to dynamically increase or decrease the bandwidth of virtual concatenated containers. The LCAS protocol is specified in ITU-T

The ITU Telecommunication Standardization Sector (ITU-T) is one of ...

. The bomb, less its radioactive components, was assembled at Foulness

Foulness Island () is a closed island on the east coast of Essex in England, which is separated from the mainland by narrow creeks. In the 2001 census, the usually resident population of the civil parish was 212, living in the settlements of Ch ...

, and then taken to the River-class frigate

The River class was a class of 151 frigates launched between 1941 and 1944 for use as anti-submarine convoy escorts in the North Atlantic. The majority served with the Royal Navy and Royal Canadian Navy (RCN), with some serving in the other Al ...

on 5 June 1952 for transport to Australia. It took ''Campania'' and ''Plym'' eight weeks to make the voyage, as they sailed around the Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope ( af, Kaap die Goeie Hoop ) ;''Kaap'' in isolation: pt, Cabo da Boa Esperança is a rocky headland on the Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula in South Africa.

A common misconception is that the Cape of Good Hope is t ...

instead of traversing the Suez Canal

The Suez Canal ( arz, قَنَاةُ ٱلسُّوَيْسِ, ') is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia. The long canal is a popular ...

, because there was unrest in Egypt at the time.

The Montebello Islands were reached on 8 August. ''Plym'' was anchored in of water, off Trimouille Island. The radioactive components, the plutonium core

Core or cores may refer to:

Science and technology

* Core (anatomy), everything except the appendages

* Core (manufacturing), used in casting and molding

* Core (optical fiber), the signal-carrying portion of an optical fiber

* Core, the centra ...

and polonium

Polonium is a chemical element with the symbol Po and atomic number 84. Polonium is a chalcogen. A rare and highly radioactive metal with no stable isotopes, polonium is chemically similar to selenium and tellurium, though its metallic character ...

-beryllium

Beryllium is a chemical element with the symbol Be and atomic number 4. It is a steel-gray, strong, lightweight and brittle alkaline earth metal. It is a divalent element that occurs naturally only in combination with other elements to form mi ...

neutron initiator

A modulated neutron initiator is a neutron source capable of producing a burst of neutrons on activation. It is a crucial part of some nuclear weapons, as its role is to "kick-start" the chain reaction at the optimal moment when the configuration i ...

, went by air, flying from RAF Lyneham

Royal Air Force Lyneham otherwise known as RAF Lyneham was a Royal Air Force station located northeast of Chippenham, Wiltshire, and southwest of Swindon, Wiltshire, England. The station was the home of all the Lockheed C-130 Hercules transpor ...

to Singapore in Handley Page Hastings

The Handley Page HP.67 Hastings is a retired British troop-carrier and freight transport aircraft designed and manufactured by aviation company Handley Page for the Royal Air Force (RAF). Upon its introduction to service during September 1948, ...

aircraft via Cyprus, Sharjah

Sharjah (; ar, ٱلشَّارقَة ', Gulf Arabic: ''aš-Šārja'') is the third-most populous city in the United Arab Emirates, after Dubai and Abu Dhabi, forming part of the Dubai-Sharjah-Ajman metropolitan area.

Sharjah is the capital o ...

and Ceylon. From Singapore they made the final leg of their journey in a Short Sunderland

The Short S.25 Sunderland is a British flying boat patrol bomber, developed and constructed by Short Brothers for the Royal Air Force (RAF). The aircraft took its service name from the town (latterly, city) and port of Sunderland in North East ...

flying boat. The British bomb design was similar to that of the American Fat Man

"Fat Man" (also known as Mark III) is the codename for the type of nuclear bomb the United States detonated over the Japanese city of Nagasaki on 9 August 1945. It was the second of the only two nuclear weapons ever used in warfare, the fir ...

, but for reasons of safety and efficiency the British design incorporated a levitated pit

The pit, named after the hard core found in fruits such as peaches and apricots, is the core of an implosion nuclear weapon – the fissile material and any neutron reflector or tamper bonded to it. Some weapons tested during the 1950s used p ...

, in which there was an air gap between the uranium tamper and the plutonium core. This gave the explosion time to build up momentum, similar in principle to a hammer hitting a nail, enabling less plutonium to be used.

The British fleet was joined by eleven RAN ships, including the

The British fleet was joined by eleven RAN ships, including the aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and facilities for carrying, arming, deploying, and recovering aircraft. Typically, it is the capital ship of a fleet, as it allows a ...

with 805

__NOTOC__

Year 805 ( DCCCV) was a common year starting on Wednesday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar.

Events

By place

Byzantine Empire

* Siege of Patras: Local Slavic tribes of the Peloponnese lay siege t ...

and 817 Squadrons embarked, and its four escorts, the destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, manoeuvrable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy or battle group and defend them against powerful short range attackers. They were originally developed in ...

, and frigates , and . The Defence (Special Undertakings) Act (1952) was passed through the Parliament of Australia

The Parliament of Australia (officially the Federal Parliament, also called the Commonwealth Parliament) is the legislature, legislative branch of the government of Australia. It consists of three elements: the monarch (represented by the ...

between 4 and 6 June 1952, and received assent on 10 June. Under this act, the area within a radius of Flag Island was declared a prohibited area for safety and security reasons. That some of this was outside Australia's territorial waters

The term territorial waters is sometimes used informally to refer to any area of water over which a sovereign state has jurisdiction, including internal waters, the territorial sea, the contiguous zone, the exclusive economic zone, and potenti ...

attracted comment. The frigate was tasked with patrolling the prohibited area, while its sister ship

A sister ship is a ship of the same class or of virtually identical design to another ship. Such vessels share a nearly identical hull and superstructure layout, similar size, and roughly comparable features and equipment. They often share a ...

acted as a weather ship. Logistical support was provided by , and ''Mildura'', the motor water lighter ''MWL 251'' and the motor refrigeration lighter ''MRL 252'', and the tugboat

A tugboat or tug is a marine vessel that manoeuvres other vessels by pushing or pulling them, with direct contact or a tow line. These boats typically tug ships in circumstances where they cannot or should not move under their own power, su ...

, which towed a fuel barge. Dakotas of No. 86 Wing RAAF provided air patrols and a weekly courier run.

Operation

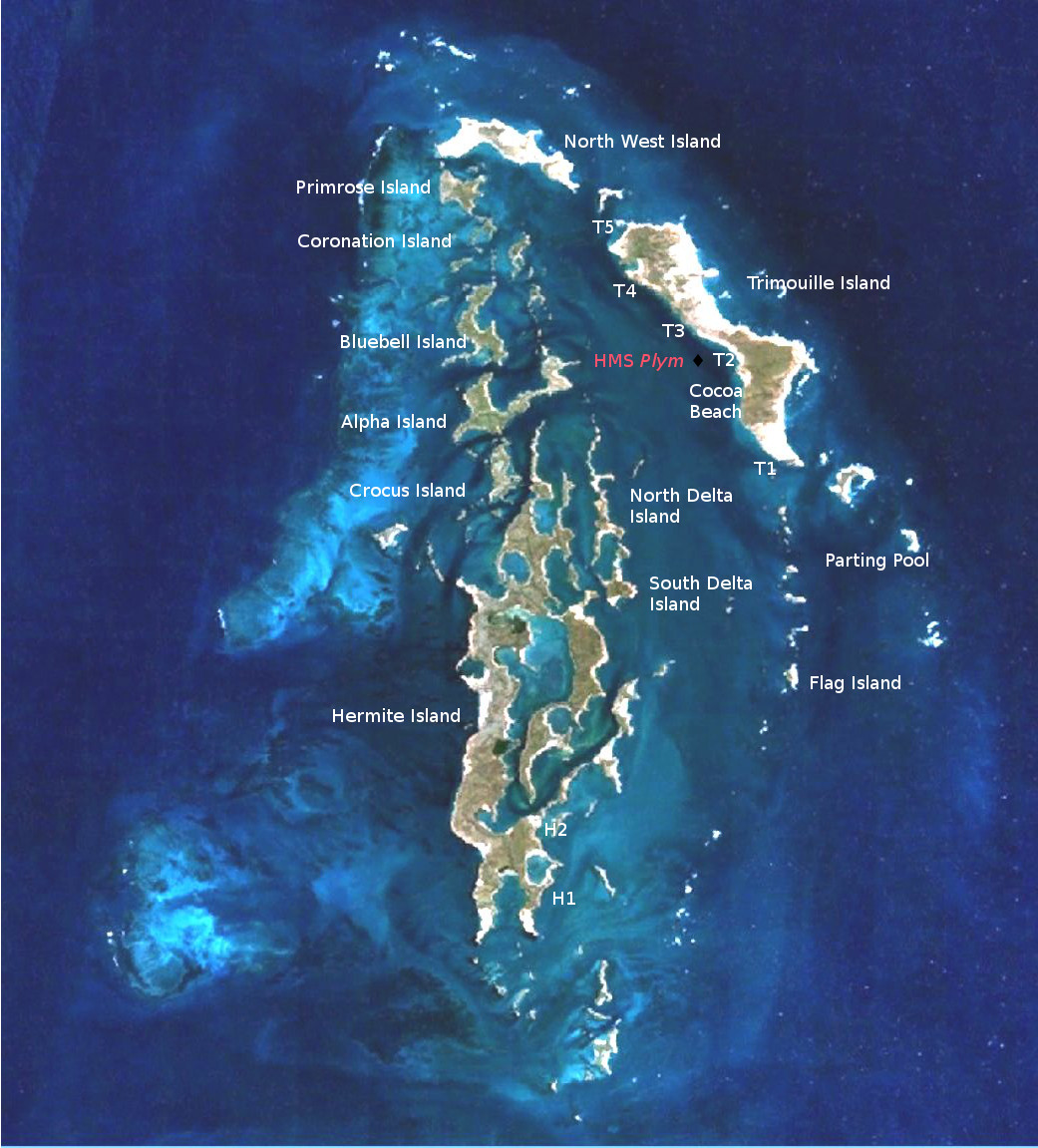

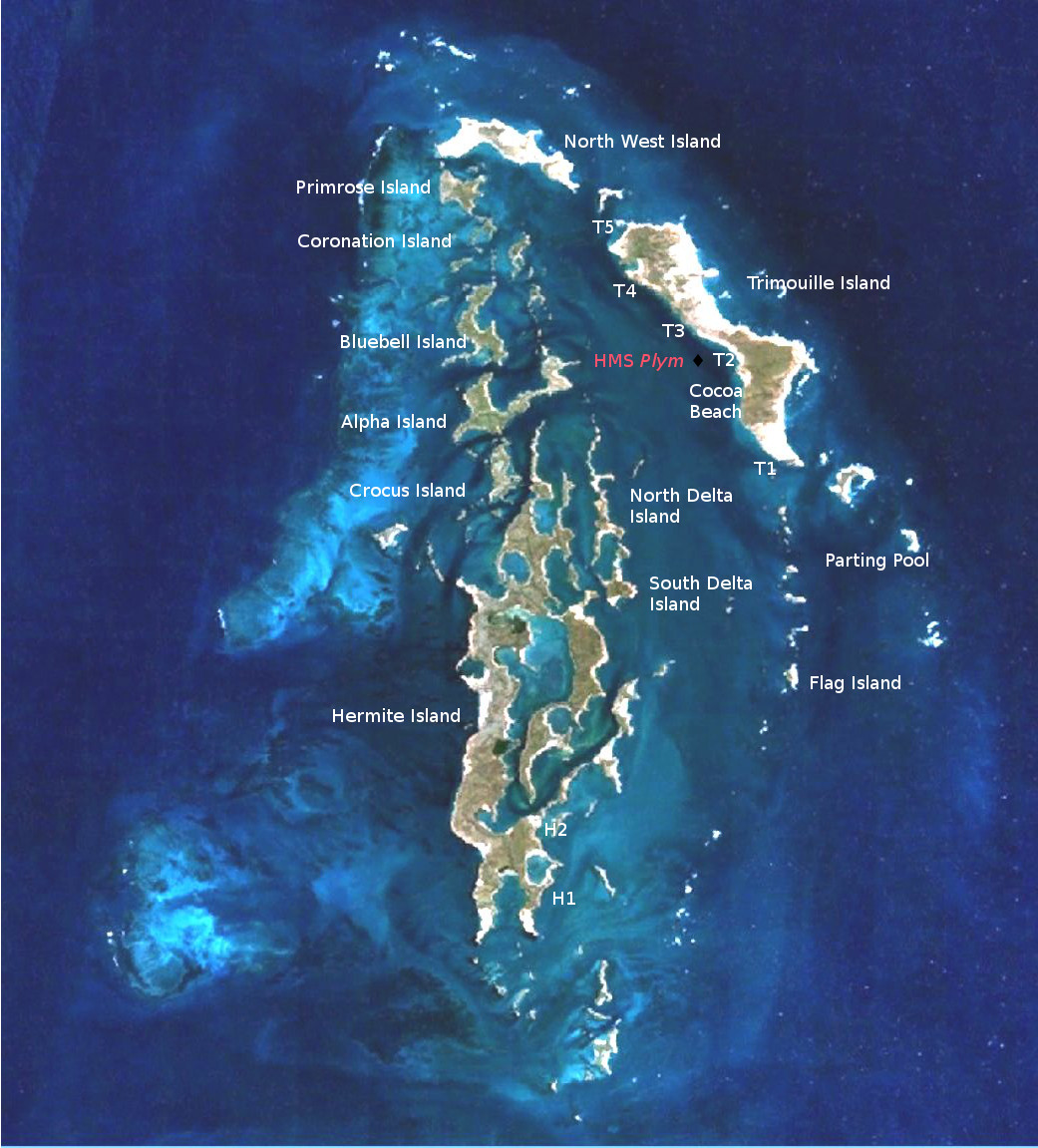

The main site, known as H1, was established on the south-east corner of Hermite Island. This was the location of the control room from which the bomb would be detonated, along with the equipment to monitor the firing circuits and telemetry. It was also the location of the generators that provided electric power and recharged the batteries of portable devices, and ultra-high-speed cameras operating at up to 8,000 frames per second. Other camera equipment was set up on Alpha Island and Northwest Island. Most of the monitoring equipment was positioned on Trimouille Island, closer to the explosion. Here, there were a plethora of blast, pressure and seismographic gauges. There were also some 200 empty fuel containers for measuring the blast, a technique that Penney had employed on Operation Crossroads. There were thermometers and calorimeters for measuring the flash, and samples of paints and fabrics for determining the effect on them. Plants would be studied to measure their uptake of fission products, particularly radioactiveiodine

Iodine is a chemical element with the symbol I and atomic number 53. The heaviest of the stable halogens, it exists as a semi-lustrous, non-metallic solid at standard conditions that melts to form a deep violet liquid at , and boils to a vi ...

and strontium

Strontium is the chemical element with the symbol Sr and atomic number 38. An alkaline earth metal, strontium is a soft silver-white yellowish metallic element that is highly chemically reactive. The metal forms a dark oxide layer when it is ex ...

. Stores were unloaded at beachhead H2 on Hermite Island, between Brandy Bay and Buttercup Island, whence the RAAF had built a road to H1. A stores compound was established at Gladstone Beach on Trimouille Island, known as T3.

The original intention was that the scientists would stay on ''Campania'', commuting to the islands each day, but the survey party had misjudged the tides; ''Campania'' could not enter the lagoon, and had to anchor in the Parting Pool. The

The original intention was that the scientists would stay on ''Campania'', commuting to the islands each day, but the survey party had misjudged the tides; ''Campania'' could not enter the lagoon, and had to anchor in the Parting Pool. The pinnaces

Pinnace may refer to:

* Pinnace (ship's boat), a small vessel used as a tender to larger vessels among other things

* Full-rigged pinnace

The full-rigged pinnace was the larger of two types of vessel called a pinnace in use from the sixteenth c ...

could not tie up alongside ''Campania'' at night, and had to be moored several miles away. Transferring to the boats in choppy waters was hazardous. One scientist fell in the sea and was rescued by Commander Douglas Bromley, ''Campania''s executive officer. Rough seas prevented much work being done between 10 and 14 August. It took about an hour and a half to get from ''Campania'' to H2, and travelling between ''Plym'' and ''Campania'' took between two and three hours. Even when a boat was on call it could take 45 minutes to respond. Boat availability soon became a problem with only five LCMs, leaving personnel waiting for one to arrive. The twelve smaller LCAs were also employed; although they could operate when the tides made waters too shallow for the pinnaces, their wooden bottoms were easily holed by coral outcrops. On 15 August, some men were transferred from ''Campania'' by one of its three Dragonfly helicopters, but the weather closed in and they could not be picked up again, having to find shelter on ''Tracker'' and ''Zeebrugge'', which were moored in the lagoon. To get around these problems, tented camps were established for the scientists at H1 on Hermite Island and Cocoa Beach (also known as T2) on Trimouille Island.

Scientific rehearsals were held on 12 and 13 September. This was followed by an operational rehearsal on 19 September, which included fully assembling the bomb, since the radioactive components had arrived the day before on a Sunderland. Penney arrived by air on 22 September. Everything was ready by 30 September, and the only remaining factor was the weather. This was unfavourable on 1 October but improved the following day, when Penney designated 3 October as the date for the test. The final countdown commenced at 07:45 local time on 3 October 1952. ''Plym'' was moored a few hundred meters west of T2 (approx 20°24'16"S, 115°34"E). The bomb was successfully detonated at 07:59:24 on 3 October 1952 local time, which was 23:59:24 on 2 October 1952 UTC, 00:59:24 on 3 October in London, and 07:59:24 on 3 October in Perth

Perth is the capital and largest city of the Australian state of Western Australia. It is the fourth most populous city in Australia and Oceania, with a population of 2.1 million (80% of the state) living in Greater Perth in 2020. Perth is ...

. The explosion occurred below the water line, and left a saucer-shaped crater on the seabed deep and across. The yield was estimated at . All that was left of ''Plym'' was a "gluey black substance" that washed up on the shore of Trimouille Island. Derek Hickman, a Royal Engineer

The Corps of Royal Engineers, usually called the Royal Engineers (RE), and commonly known as the ''Sappers'', is a corps of the British Army. It provides military engineering and other technical support to the British Armed Forces and is heade ...

observing the blast aboard ''Zeebrugge'', later said of ''Plym'', "all that was left of her were a few fist-sized pieces of metal that fell like rain, and the shape of the frigate scorched on the sea bed." The bomb had performed exactly as expected.

Two Dragonfly helicopters flew in to gather a sample of contaminated seawater from the lagoon. Scientists in gas masks and protective gear visited points in pinnaces to collect samples and retrieve recordings. ''Tracker'' controlled this aspect, as it had the decontamination facilities. Air samples were collected by RAAF Avro Lincoln

The Avro Type 694 Lincoln is a British four-engined heavy bomber, which first flew on 9 June 1944. Developed from the Avro Lancaster, the first Lincoln variants were initially known as the Lancaster IV and V; these were renamed Lincoln I and ...

aircraft. Although the feared tidal surge had not occurred, radioactive contamination

Radioactive contamination, also called radiological pollution, is the deposition of, or presence of radioactive substances on surfaces or within solids, liquids, or gases (including the human body), where their presence is unintended or undesirab ...

of the islands was widespread and severe. It was clear that had an atomic bomb exploded in a British port, it would have been a catastrophe worse than the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki