Operation Berlin (Atlantic) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

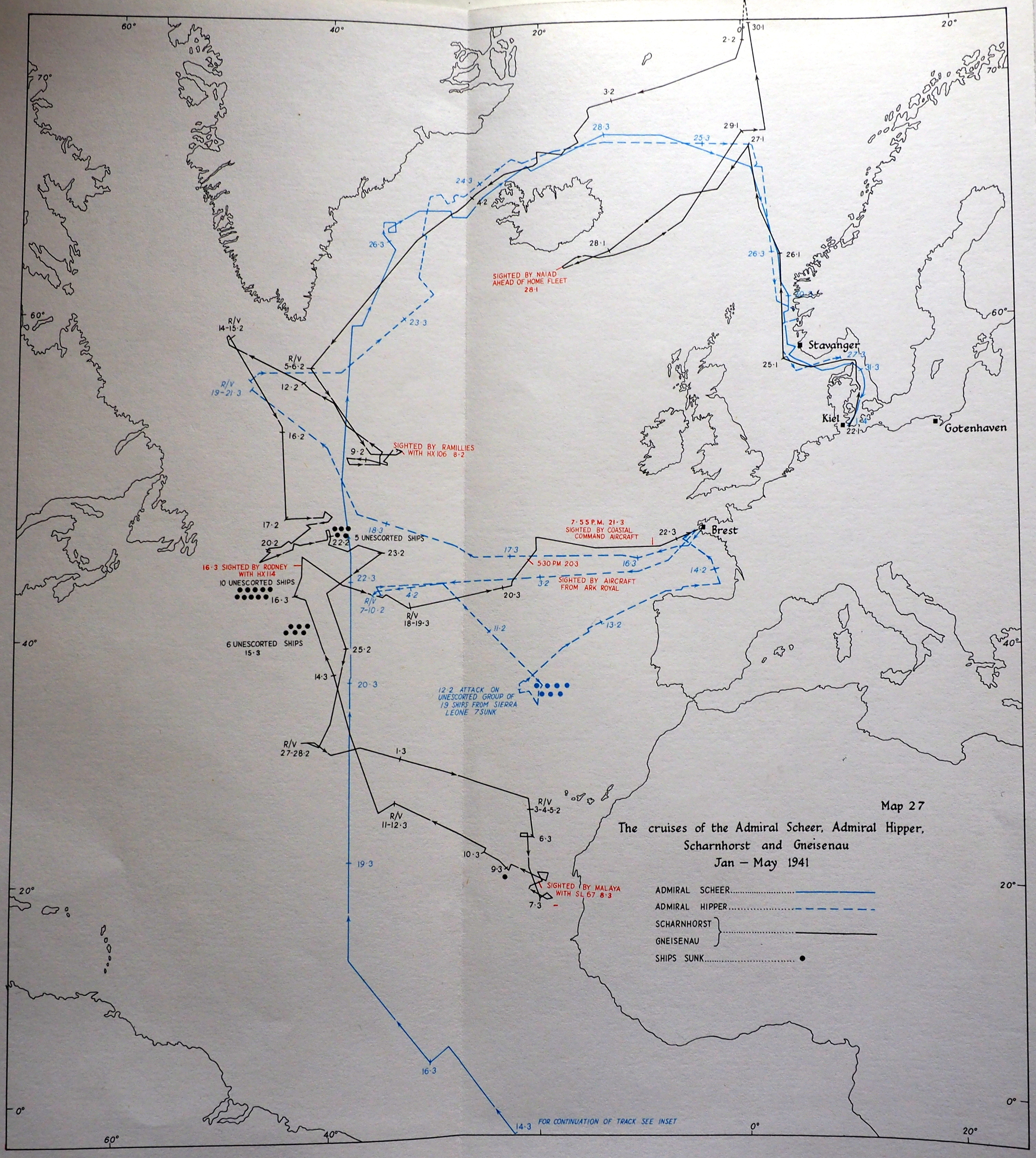

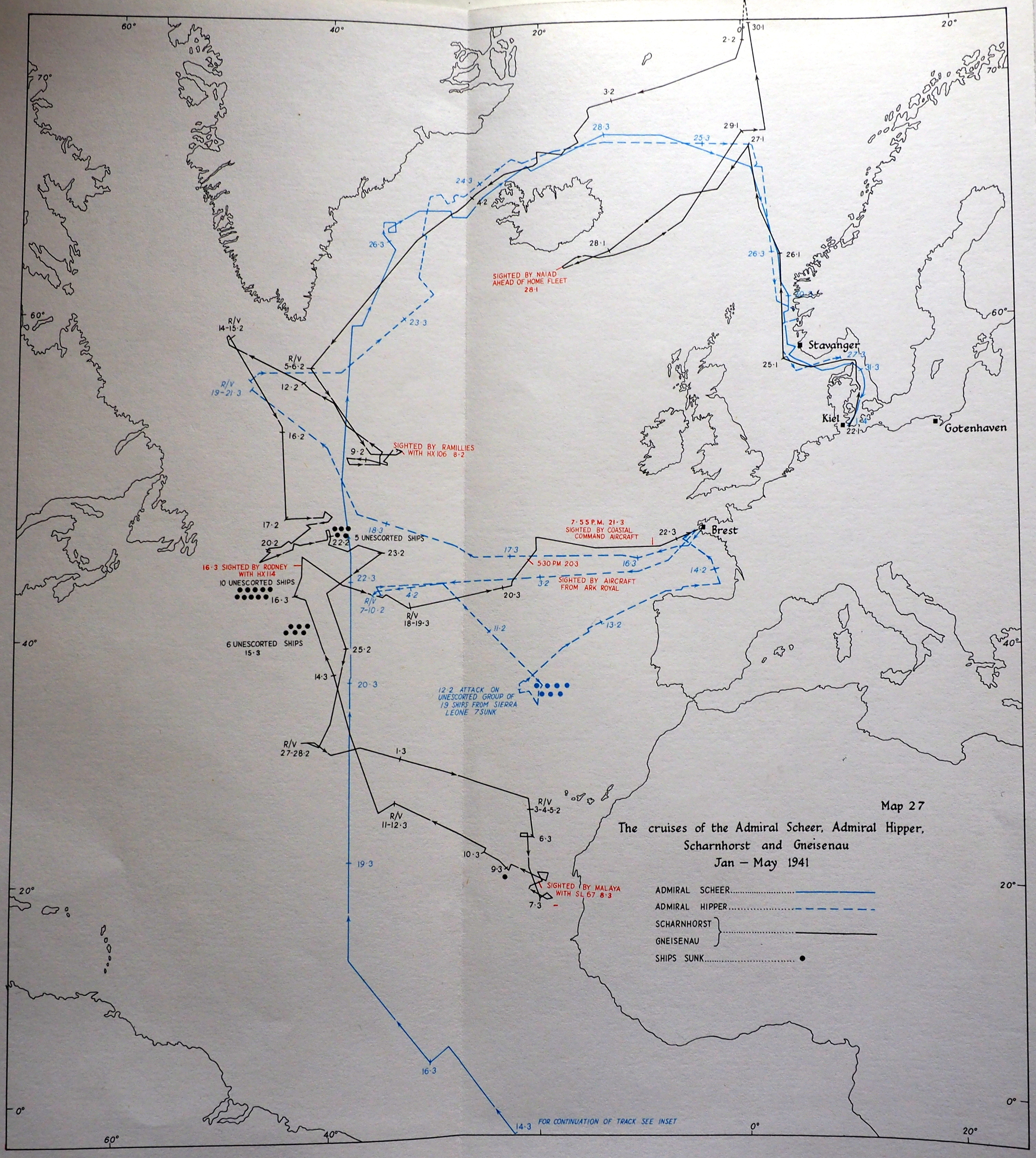

Operation Berlin was a raid conducted by the two German ''Scharnhorst''-class battleships against

The ''Scharnhorst''-class battleships conducted their first raid in late November 1939. During this operation they sank the

The ''Scharnhorst''-class battleships conducted their first raid in late November 1939. During this operation they sank the

''Scharnhorst'' and ''Gneisenau'' sailed again from Kiel at 4:00 am on 22 January 1941. They proceeded north and passed through the

''Scharnhorst'' and ''Gneisenau'' sailed again from Kiel at 4:00 am on 22 January 1941. They proceeded north and passed through the

The German battleships separated to attack the convoy, with ''Scharnhorst'' approaching it from the south and ''Gneisenau'' from the north-west. ''Scharnhorst''s crew spotted ''Ramillies'' at 9:47 am, and reported this to the flagship. In accordance with his orders to avoid engagements with powerful enemy forces, Lütjens cancelled the attack. Before being instructed to break off, ''Scharnhorst''s commanding officer, Captain

The German battleships separated to attack the convoy, with ''Scharnhorst'' approaching it from the south and ''Gneisenau'' from the north-west. ''Scharnhorst''s crew spotted ''Ramillies'' at 9:47 am, and reported this to the flagship. In accordance with his orders to avoid engagements with powerful enemy forces, Lütjens cancelled the attack. Before being instructed to break off, ''Scharnhorst''s commanding officer, Captain

Coastal Command aircraft located the two German battleships at Brest on 28 March after six days of intensive searches of French ports. Once the battleships were confirmed to be in port, the Home Fleet returned to its bases for a brief period and the Atlantic convoy system returned to its normal routings. Due to the threat the force at Brest posed, the Home Fleet

Coastal Command aircraft located the two German battleships at Brest on 28 March after six days of intensive searches of French ports. Once the battleships were confirmed to be in port, the Home Fleet returned to its bases for a brief period and the Atlantic convoy system returned to its normal routings. Due to the threat the force at Brest posed, the Home Fleet

Allied

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

shipping in the North Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the "Old World" of Africa, Europe and ...

between 22 January and 22 March 1941. It formed part of the Battle of the Atlantic

The Battle of the Atlantic, the longest continuous military campaign in World War II, ran from 1939 to the defeat of Nazi Germany in 1945, covering a major part of the naval history of World War II. At its core was the Allied naval blockade ...

during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

. The and sailed from Germany, operated across the North Atlantic, sank or captured 22 Allied merchant vessels, and finished their mission by docking in occupied France

The Military Administration in France (german: Militärverwaltung in Frankreich; french: Occupation de la France par l'Allemagne) was an interim occupation authority established by Nazi Germany during World War II to administer the occupied zo ...

. The British military sought to locate and attack the German battleships, but failed to damage them.

The operation was one of several made by German warships during late 1940 and early 1941. Its main goal was for the battleships to overwhelm the escort of one of the convoy

A convoy is a group of vehicles, typically motor vehicles or ships, traveling together for mutual support and protection. Often, a convoy is organized with armed defensive support and can help maintain cohesion within a unit. It may also be used ...

s transporting supplies to the United Kingdom and then sink large numbers of merchant ships. The British were expecting this given previous attacks, and assigned battleships of their own to escort convoys. This proved successful, with the German force having to abandon attacks against convoys on 8 February as well as 7 and 8 March. The Germans encountered and attacked large numbers of unescorted merchant ships on 22 February and 15–16 March.

By the end of the raid, the German battleships had roamed widely across the Atlantic, ranging from the waters off Greenland

Greenland ( kl, Kalaallit Nunaat, ; da, Grønland, ) is an island country in North America that is part of the Kingdom of Denmark. It is located between the Arctic and Atlantic oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Greenland is t ...

to the West African coast. The operation was considered successful by the German military, a view generally shared by historians. It was the last victory achieved by German warship

A warship or combatant ship is a naval ship that is built and primarily intended for naval warfare. Usually they belong to the armed forces of a state. As well as being armed, warships are designed to withstand damage and are usually faster a ...

s against merchant shipping in the North Atlantic, with the sortie made by the battleship ''Bismarck'' in May 1941 ending in defeat. Both ''Scharnhorst''-class battleships were damaged by air attacks while they were in France and returned to Germany in February 1942.

Background

Opposing plans

The (German Navy) developed plans before the outbreak ofWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

to attack Allied

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

merchant shipping in the event of war. Under these plans, warship

A warship or combatant ship is a naval ship that is built and primarily intended for naval warfare. Usually they belong to the armed forces of a state. As well as being armed, warships are designed to withstand damage and are usually faster a ...

s were to be used against shipping on the high seas and submarine

A submarine (or sub) is a watercraft capable of independent operation underwater. It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability. The term is also sometimes used historically or colloquially to refer to remotely op ...

s and aircraft would attack shipping near the coasts of Allied countries. Surface raiders were to range widely, make surprise attacks and then move to other areas. They were to be supported by supply ships that would be pre-positioned before the start of operations. Grand Admiral Erich Raeder

Erich Johann Albert Raeder (24 April 1876 – 6 November 1960) was a German admiral who played a major role in the naval history of World War II. Raeder attained the highest possible naval rank, that of grand admiral, in 1939, becoming the f ...

, the commander of the , was determined to include the fleet's battleship

A battleship is a large armored warship with a main battery consisting of large caliber guns. It dominated naval warfare in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The term ''battleship'' came into use in the late 1880s to describe a type of ...

s in these attacks. He believed that the Imperial German Navy

The Imperial German Navy or the Imperial Navy () was the navy of the German Empire, which existed between 1871 and 1919. It grew out of the small Prussian Navy (from 1867 the North German Federal Navy), which was mainly for coast defence. Wilhel ...

's decision to not use its battleships aggressively during World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

was a mistake, and wanted to avoid repeating this perceived error. In order to conserve the 's small number of battleships and other major warships for as long as possible, the navy's plans specified that raiders would target merchant vessels and avoid combat with Allied warships.

The Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

anticipated Germany's intentions, and adopted plans of its own to institute convoy

A convoy is a group of vehicles, typically motor vehicles or ships, traveling together for mutual support and protection. Often, a convoy is organized with armed defensive support and can help maintain cohesion within a unit. It may also be used ...

s to protect merchant shipping and deploy cruiser

A cruiser is a type of warship. Modern cruisers are generally the largest ships in a fleet after aircraft carriers and amphibious assault ships, and can usually perform several roles.

The term "cruiser", which has been in use for several hu ...

s to detect attempts by German warships to break out into the Atlantic Ocean. These included initiating cruiser patrols of the waters between Greenland and Scotland through which German raiders would have to pass to enter the Atlantic following the outbreak of war. The Home Fleet

The Home Fleet was a fleet of the Royal Navy that operated from the United Kingdom's territorial waters from 1902 with intervals until 1967. In 1967, it was merged with the Mediterranean Fleet creating the new Western Fleet.

Before the First ...

, the main British battle force in the North Atlantic, was responsible for locating and intercepting German warships in the area. From 20 December 1940 it was commanded by Admiral John Tovey

Admiral of the Fleet John Cronyn Tovey, 1st Baron Tovey, (7 March 1885 – 12 January 1971), sometimes known as Jack Tovey, was a Royal Navy officer. During the First World War he commanded the destroyer at the Battle of Jutland and then co ...

.

Both ''Scharnhorst''-class battleships (sometimes designated battlecruiser

The battlecruiser (also written as battle cruiser or battle-cruiser) was a type of capital ship of the first half of the 20th century. These were similar in displacement, armament and cost to battleships, but differed in form and balance of attr ...

s) and were combat ready at the start of the war in September 1939. The roles envisioned for these battleships when they were designed in the early 1930s included raiding convoys. They were heavily armoured and faster than the Royal Navy's battlecruisers. Their main armament was nine guns, which were inferior to the guns that armed most British battleships. The ''Scharnhorst''-class battleships were capable of sailing for at . This was insufficient for lengthy raids, and meant that they needed to regularly refuel from supply ships.

German surface raids

The ''Scharnhorst''-class battleships conducted their first raid in late November 1939. During this operation they sank the

The ''Scharnhorst''-class battleships conducted their first raid in late November 1939. During this operation they sank the armed merchant cruiser

An armed merchantman is a merchant ship equipped with guns, usually for defensive purposes, either by design or after the fact. In the days of sail, piracy and privateers, many merchantmen would be routinely armed, especially those engaging in lo ...

between Iceland and the Faroe Islands on 23 November. In April 1940 they took part in Operation Weserübung

Operation Weserübung (german: Unternehmen Weserübung , , 9 April – 10 June 1940) was Germany's assault on Denmark and Norway during the Second World War and the opening operation of the Norwegian Campaign.

In the early morning of 9 Ap ...

, the German invasion of Norway, where they formed the most powerful element of the battle group under Vice Admiral Günther Lütjens

Johann Günther Lütjens (25 May 1889 – 27 May 1941) was a German admiral whose military service spanned more than thirty years and two world wars. Lütjens is best known for his actions during World War II and his command of the battleship d ...

that provided a covering force A covering force is a military force tasked with operating in conjunction with a larger force, with the role of providing a strong protective outpost line (including operating in advance of the main force), searching for and attacking enemy forces o ...

to protect the rest of the German invasion fleet from counter-attacks by the Royal Navy. On 9 April they encountered the British battlecruiser off the Lofoten Islands

Lofoten () is an archipelago and a traditional district in the county of Nordland, Norway. Lofoten has distinctive scenery with dramatic mountains and peaks, open sea and sheltered bays, beaches and untouched lands. There are two towns, Svolvæ ...

. Both German ships were damaged in the resulting battle, leading Lütjens to disengage and return to Germany. The battleships sortied again on 4 June to raid Allied shipping near Narvik

( se, Áhkanjárga) is the third-largest municipality in Nordland county, Norway, by population. The administrative centre of the municipality is the town of Narvik. Some of the notable villages in the municipality include Ankenesstranda, Ball ...

in northern Norway in what was designated Operation Juno

Operation Juno was a German sortie to the North Sea during the Norwegian Campaign. The most notable engagement of the operation was German battleships and sinking the British aircraft carrier and its two escorting destroyers. Several Allied v ...

. On 8 June they sank the empty troop transport SS ''Orama'' as well as the British aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and facilities for carrying, arming, deploying, and recovering aircraft. Typically, it is the capital ship of a fleet, as it allows a ...

and its two escorting destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, manoeuvrable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy or battle group and defend them against powerful short range attackers. They were originally developed in ...

s. A destroyer torpedo

A modern torpedo is an underwater ranged weapon launched above or below the water surface, self-propelled towards a target, and with an explosive warhead designed to detonate either on contact with or in proximity to the target. Historically, su ...

ed ''Scharnhorst'' during this action, inflicting damage that took six months to repair. On 20 June ''Gneisenau'' took part in a sortie from the occupied Norwegian city of Trondheim

Trondheim ( , , ; sma, Tråante), historically Kaupangen, Nidaros and Trondhjem (), is a city and municipality in Trøndelag county, Norway. As of 2020, it had a population of 205,332, was the third most populous municipality in Norway, and ...

. She was torpedoed that day by the submarine . The torpedo explosion caused large holes in her bow that required lengthy repairs in Germany.

''Scharnhorst''s repairs were largely completed by late November 1940, and ''Gneisenau'' reentered service in early December. The ships trained together in the Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden and the North and Central European Plain.

The sea stretches from 53°N to 66°N latitude and from ...

during December. After ''Scharnhorst'' completed the last element of its repairs, both battleships were assessed on 23 December as being ready for another raid.

In August 1940 the German leader Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

ordered an intensification of the attacks on Allied shipping in the Atlantic. The began dispatching its major warships that had survived the Norwegian campaign into the Atlantic in October. The heavy cruiser

The heavy cruiser was a type of cruiser, a naval warship designed for long range and high speed, armed generally with naval guns of roughly 203 mm (8 inches) in caliber, whose design parameters were dictated by the Washington Naval Tr ...

''Admiral Scheer'' sailed during that month, and conducted a successful raid that lasted until March 1941. The heavy cruiser ''Admiral Hipper'' made an unsuccessful raid from Germany into the Atlantic during December that ended with her docking at Brest

Brest may refer to:

Places

*Brest, Belarus

**Brest Region

**Brest Airport

**Brest Fortress

* Brest, Kyustendil Province, Bulgaria

* Břest, Czech Republic

*Brest, France

** Arrondissement of Brest

**Brest Bretagne Airport

** Château de Brest

*Br ...

in occupied France

The Military Administration in France (german: Militärverwaltung in Frankreich; french: Occupation de la France par l'Allemagne) was an interim occupation authority established by Nazi Germany during World War II to administer the occupied zo ...

. During this operation, ''Admiral Hipper'' attacked Convoy WS 5A

A convoy is a group of vehicles, typically motor vehicles or ships, traveling together for mutual support and protection. Often, a convoy is organized with armed defensive support and can help maintain cohesion within a unit. It may also be used ...

on 25 December and damaged two transports before being driven off by escorting British cruisers. Six German merchant raider

Merchant raiders are armed commerce raiding ships that disguise themselves as non-combatant merchant vessels.

History

Germany used several merchant raiders early in World War I (1914–1918), and again early in World War II (1939–1945). The cap ...

s also operated against Allied shipping in the South Atlantic, Indian and Pacific Oceans. The attack on Convoy WS 5A demonstrated that raiders posed a serious threat to shipping in the North Atlantic, and from early 1941 the British Admiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

*Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

*Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

* Admiralty, Traf ...

assigned battleships to escort convoys that were bound for the United Kingdom whenever possible. Westbound convoys lacked this protection, and were dispersed in the middle of the Atlantic.

Raid

First attempt

The ''Scharnhorst''-class battleships were selected for the next raid, which was designated Operation Berlin. Its goal was for the ships to break out into the Atlantic and operate together to attack Allied shipping. Their primary objective was to intercept one of the HX convoys that regularly sailed from Halifax in Canada to the United Kingdom. These convoys were a key element of the Allied supply line to the United Kingdom, and the Germans hoped that the battleships could overwhelm the convoy's escort and then sink large numbers of merchant ships. Raeder directed the battleships to end their raid by docking at Brest, which had been selected as the 's main base in October 1940. The orders issued for the operation forbade attacks on convoys escorted by forces of equal strength, such as British battleships. This was because the raid would need to be abandoned if ''Scharnhorst'' or ''Gneisenau'' was significantly damaged. Lütjens, who had been appointed the 'sfleet commander

The Fleet Commander is a senior Royal Navy post, responsible for the operation, resourcing and training of the ships, submarines and aircraft, and personnel, of the Naval Service. The Vice-Admiral incumbent is required to provide ships, submarine ...

in July 1940 and promoted to admiral in September that year, commanded the battle group.

Seven supply ships were dispatched into the Atlantic ahead of Operation Berlin to support the two raiders. The plans for the operation also called for ''Admiral Hipper'' to sortie from Brest and attack the convoy routes between Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = " Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gib ...

, Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone,)]. officially the Republic of Sierra Leone, is a country on the southwest coast of West Africa. It is bordered by Liberia to the southeast and Guinea surrounds the northern half of the nation. Covering a total area of , Sierra ...

and the United Kingdom. As well as inflicting further casualties, it was hoped that the cruiser would divert British forces away from Lütjens' area of operations.

At this time the German signals intelligence

Signals intelligence (SIGINT) is intelligence-gathering by interception of ''signals'', whether communications between people (communications intelligence—abbreviated to COMINT) or from electronic signals not directly used in communication ( ...

service was providing raiders with general information about the locations of Allied ships. The service was generally unable to pass on actionable intelligence though, as it was unable to decrypt

In cryptography, encryption is the process of encoding information. This process converts the original representation of the information, known as plaintext, into an alternative form known as ciphertext. Ideally, only authorized parties can deci ...

intercepted radio messages. Each raider embarked a detachment that monitored Allied radio signals and used direction finding

Direction finding (DF), or radio direction finding (RDF), isin accordance with International Telecommunication Union (ITU)defined as radio location that uses the reception of radio waves to determine the direction in which a radio station ...

techniques to locate convoys and warships. The Germans had little intelligence on the dates on which Allied convoys sailed or the routes they took. This made it difficult for surface raiders to position themselves in the path of convoys.

Operation Berlin was launched on 28 December 1940. ''Scharnhorst'' and ''Gneisenau'' sailed from Kiel

Kiel () is the capital and most populous city in the northern Germany, German state of Schleswig-Holstein, with a population of 246,243 (2021).

Kiel lies approximately north of Hamburg. Due to its geographic location in the southeast of the J ...

on that day, with Lütjens commanding the force from the latter ship. The raid had to be abandoned before the battleships entered the Atlantic when ''Gneisenau'' was damaged by a storm off Norway on 30 December. Lütjens initially took the ships into Korsfjord in Norway and planned to repair ''Gneisenau'' at Trondheim, but was ordered to return to Germany. Both ships reached Gotenhafen

Gdynia ( ; ; german: Gdingen (currently), (1939–1945); csb, Gdiniô, , , ) is a city in northern Poland and a seaport on the Baltic Sea coast. With a population of 243,918, it is the 12th-largest city in Poland and the second-largest in th ...

on 2 January. ''Gneisenau'' was transferred to Kiel to be repaired. The battleships received additional small calibre anti-aircraft guns during this period.

Breakout into the Atlantic

''Scharnhorst'' and ''Gneisenau'' sailed again from Kiel at 4:00 am on 22 January 1941. They proceeded north and passed through the

''Scharnhorst'' and ''Gneisenau'' sailed again from Kiel at 4:00 am on 22 January 1941. They proceeded north and passed through the Great Belt

The Great Belt ( da, Storebælt, ) is a strait between the major islands of Zealand (''Sjælland'') and Funen (''Fyn'') in Denmark. It is one of the three Danish Straits.

Effectively dividing Denmark in two, the Belt was served by the Great Be ...

island chain in German-controlled Denmark that morning. This exposed the battleships to Allied agents on the shore, but was necessary as the waterway was covered in ice thick. The battle group reached Skagen

Skagen () is Denmark's northernmost town, on the east coast of the Skagen Odde peninsula in the far north of Jutland, part of Frederikshavn Municipality in Nordjylland, north of Frederikshavn and northeast of Aalborg. The Port of Skagen is ...

on the northern tip of Denmark on the evening of 23 January where it was to meet up with a flotilla

A flotilla (from Spanish, meaning a small ''flota'' (fleet) of ships), or naval flotilla, is a formation of small warships that may be part of a larger fleet.

Composition

A flotilla is usually composed of a homogeneous group of the same class ...

of torpedo boat

A torpedo boat is a relatively small and fast naval ship designed to carry torpedoes into battle. The first designs were steam-powered craft dedicated to ramming enemy ships with explosive spar torpedoes. Later evolutions launched variants of se ...

s that would escort it through minefields between Denmark and Norway. The torpedo boats were slow to leave port, and Lütjens' force did not resume its voyage until dawn on 25 January.

From intelligence obtained by traffic analysis

Traffic analysis is the process of intercepting and examining messages in order to deduce information from patterns in communication, it can be performed even when the messages are encrypted. In general, the greater the number of messages observed ...

of German radio signals, the British had concluded that major German warships were about to put to sea; Ultra

adopted by British military intelligence in June 1941 for wartime signals intelligence obtained by breaking high-level encrypted enemy radio and teleprinter communications at the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) at Bletchley Park. '' ...

intelligence obtained by breaking German codes did not provide any information on Operation Berlin as the British were unable to decrypt the codes at this time. On 20 January the Admiralty warned the Home Fleet that another German raid was likely. Tovey immediately dispatched two heavy cruisers to reinforce the patrols between Allied-occupied Iceland and the Faroe Islands

The Faroe Islands ( ), or simply the Faroes ( fo, Føroyar ; da, Færøerne ), are a North Atlantic island group and an autonomous territory of the Kingdom of Denmark.

They are located north-northwest of Scotland, and about halfway bet ...

. On 23 January the British naval attaché

A navy, naval force, or maritime force is the branch of a nation's armed forces principally designated for naval and amphibious warfare; namely, lake-borne, riverine, littoral, or ocean-borne combat operations and related functions. It includ ...

in Sweden passed on a report from agents in Denmark that the German battleships had been sighted passing through the Great Belt. This intelligence was provided to Tovey during the evening of 25 January.

The main body of the Home Fleet departed its base at Scapa Flow

Scapa Flow viewed from its eastern end in June 2009

Scapa Flow (; ) is a body of water in the Orkney Islands, Scotland, sheltered by the islands of Mainland, Graemsay, Burray,S. C. George, ''Jutland to Junkyard'', 1973. South Ronaldsay and ...

at midnight on 25 January bound for a position south of Iceland. It comprised the battleships (Tovey's flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically the fi ...

) and , battlecruiser , eight cruisers and eleven destroyers. Air patrols of the waters between Iceland and the Faroes were also stepped up. Some of the Home Fleet's ships were detached to refuel on 27 January. The had expected this deployment, and stationed eight submarines to the south of Iceland to attack the Home Fleet. Only one of these submarines sighted any British warships, and it was unable to reach a position from which they could be attacked.

The German battle group entered the North Sea on 26 January. Lütjens was inclined to refuel from the tanker ''Adria'' that had been positioned in the Arctic Ocean

The Arctic Ocean is the smallest and shallowest of the world's five major oceans. It spans an area of approximately and is known as the coldest of all the oceans. The International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) recognizes it as an ocean, a ...

before attempting to enter the Atlantic. He decided to proceed directly to the south of Iceland though after receiving a weather forecast which predicted snow storms in that area; these conditions would hide the battleships from the British. Just before dawn on 28 January, the two German battleships detected the British cruiser and another cruiser by radar

Radar is a detection system that uses radio waves to determine the distance (''ranging''), angle, and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It can be used to detect aircraft, ships, spacecraft, guided missiles, motor vehicles, w ...

to the south of Iceland. ''Naiad''s crew sighted two large vessels six minutes later. Lütjens lacked information about whether the rest of the Home Fleet was at sea, and decided to break off this attempt to enter the Atlantic. The battle group evaded the British by turning to the north-east and operating in the Norwegian Sea

The Norwegian Sea ( no, Norskehavet; is, Noregshaf; fo, Norskahavið) is a marginal sea, grouped with either the Atlantic Ocean or the Arctic Ocean, northwest of Norway between the North Sea and the Greenland Sea, adjoining the Barents Sea to ...

north of the Arctic circle

The Arctic Circle is one of the two polar circles, and the most northerly of the five major circles of latitude as shown on maps of Earth. Its southern equivalent is the Antarctic Circle.

The Arctic Circle marks the southernmost latitude at w ...

. One of ''Gneisenau''s two aircraft was dispatched to Trondheim in Norway on 28 January carrying a report on the events of the day and did not rejoin its ship. Tovey ordered his cruisers to search for the raiders and moved his battleships and battlecruiser to intercept them but contact was not regained. After concluding that ''Naiad'' may have not actually sighted German warships, Tovey sailed west to protect a convoy and returned to Scapa Flow on 30 January. ''Admiral Hipper'' departed Brest on 1 February to begin its raid.

After refuelling from ''Adria'' in the Arctic Ocean well to the north-east of Jan Mayen

Jan Mayen () is a Norwegian volcanic island in the Arctic Ocean with no permanent population. It is long (southwest-northeast) and in area, partly covered by glaciers (an area of around the Beerenberg volcano). It has two parts: larger nort ...

island, Lütjens attempted to enter the Atlantic through the Denmark Strait

The Denmark Strait () or Greenland Strait ( , 'Greenland Sound') is an oceanic strait between Greenland to its northwest and Iceland to its southeast. The Norwegian island of Jan Mayen lies northeast of the strait.

Geography

The strait connect ...

north of Iceland. The battleships passed through the straits undetected on the night of 3/4 February. They refuelled again from the supply ship ''Schlettstadt'' off southern Greenland on 5 and 6 February.

Initial Atlantic operations

From 6 February Lütjens searched for HX convoys. He was aware that two British battleships had been based in Canada to escort eastbound convoys, but believed that they would only cover the first part of the journey before returning to pick up another convoy. Accordingly, the German force operated to the east of what Lütjens believed was the limit of the battleship escorts. Convoy HX 106 was sighted at dawn on 8 February approximately east of Halifax. Unbeknownst to the Germans, this convoy's escort included the old battleship . The German battleships separated to attack the convoy, with ''Scharnhorst'' approaching it from the south and ''Gneisenau'' from the north-west. ''Scharnhorst''s crew spotted ''Ramillies'' at 9:47 am, and reported this to the flagship. In accordance with his orders to avoid engagements with powerful enemy forces, Lütjens cancelled the attack. Before being instructed to break off, ''Scharnhorst''s commanding officer, Captain

The German battleships separated to attack the convoy, with ''Scharnhorst'' approaching it from the south and ''Gneisenau'' from the north-west. ''Scharnhorst''s crew spotted ''Ramillies'' at 9:47 am, and reported this to the flagship. In accordance with his orders to avoid engagements with powerful enemy forces, Lütjens cancelled the attack. Before being instructed to break off, ''Scharnhorst''s commanding officer, Captain Kurt-Caesar Hoffmann

Kurt-Caesar Hoffmann (26 August 1895 – 19 May 1988) was a senior naval commander in the German Navy ('' Kriegsmarine'') during World War II, who commanded the battleship . He was a recipient of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross.

Career

Hof ...

, brought his ship within of the convoy in an attempt to draw ''Ramillies'' away so that ''Gneisenau'' could make a separate attack on the merchant vessels. This violated the order against engaging warships of equal strength, and Lütjens reprimanded Hoffmann by radio when the two battleships met that evening.

The British battleship's crew sighted one of the German ships from a long distance, and misidentified it as probably being an ''Admiral Hipper''-class cruiser. Tovey judged that the ship was either ''Admiral Hipper'' or ''Admiral Scheer'', and sailed with all available ships to intercept it if it returned to Germany or France. These ships were organised into three powerful forces from the evening of 9 February, and air patrols were also conducted. Force H, a powerful task force based in Gibraltar that was commanded by Vice Admiral James Somerville

Admiral of the Fleet Sir James Fownes Somerville, (17 July 1882 – 19 March 1949) was a Royal Navy officer. He served in the First World War as fleet wireless officer for the Mediterranean Fleet where he was involved in providing naval suppo ...

and included ''Renown'' and the aircraft carrier , was also ordered to protect convoys in the North Atlantic. It sailed from Gibraltar to do so on 12 February, and returned to that port on the 25th of the month.

On the morning of 9 February Navy Group West informed Lütjens that intercepted British radio messages indicated that his ships had been sighted the previous day. Lütjens judged that the British would now assign strong escorts to all convoys in the area, and decided to break off operations for several days in the hope that attacks by ''Admiral Hipper'' would divert British forces elsewhere. The German battle group returned to the waters off southern Greenland and remained there until 17 February. It endured a severe storm on 12 February which damaged many of ''Scharnhorst''s gun turrets; it took three days to return them to service. ''Gneisenau''s engines also became contaminated with sea water and needed to be repaired. The battleships refuelled from ''Schlettstadt'' and the tanker '' Esso Hamburg'' on 14 and 15 February. During this period, ''Admiral Hipper'' attacked an unescorted convoy on 12 February and sank seven ships. The cruiser then returned to Brest on 15 February. It was intended for ''Admiral Hipper'' to make another raid in support of Operation Berlin after loading more ammunition. This attack was cancelled after she damaged a propeller on a sunken barge in Brest's harbour and was unable to sail until a replacement was received from Kiel.

The German battle group returned to the route between Halifax and the United Kingdom on 17 February. Lütjens decided to operate between the 55th and 45th meridian west, which were to the west of where he had encountered HX 106, in the correct belief that Allied shipping there was not as well escorted. He hoped to find one of the regular HX convoys or a special convoy that the German naval attaché in Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

had reported was expected to depart from Halifax on 15 February. A merchant ship sailing independently was sighted on 17 February but not attacked as Lütjens did not want to risk alerting any nearby convoys. Shortly after dawn on 22 February the German battleships encountered several ships sailing west from a recently dispersed convoy east of Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador (; french: Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador; frequently abbreviated as NL) is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region ...

. They sank five of the vessels totalling . A total of 187 survivors were rescued from these ships. The battleships jammed radio transmissions from the merchant vessels as they closed with them. However, one of the ships was able to transmit a sighting report after being attacked by an aircraft that had been launched from the battleships. The signal was received by a radio station at Cape Race

Cape Race is a point of land located at the southeastern tip of the Avalon Peninsula on the island of Newfoundland, in Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada. Its name is thought to come from the original Portuguese name for this cape, "Raso", mea ...

in Newfoundland and was quickly passed on to the Admiralty. This was the first it knew about the battleships' presence in the western Atlantic. Lütjens judged that the Allies would now divert shipping from the area and search for his ships. Accordingly, he decided to transfer his operations to the eastern Atlantic and attack the SL convoys

SL convoys were a numbered series of North Atlantic trade convoys during the Second World War. Merchant ships carrying commodities bound to the British Isles from South America, Africa, and the Indian Ocean traveled independently to Freetown, Si ...

that travelled between Sierra Leone and the United Kingdom.

West Africa

From 22 February the German ships sailed south. They refuelled from the tankers ''Ermland'' and ''Fredric Breme'' between 26 and 28 February and then turned to the south-east. The ships searched for a SL convoy that Lütjens expected to encounter on 5 March, but without success. The admiral hoped to use the battleships' aircraft to aid the search, but two of the three were unserviceable and beyond repair and the other was mechanically unreliable. The next day the battle group rendezvoused with the German submarine ''U-124'' offwest Africa

West Africa or Western Africa is the westernmost region of Africa. The United Nations defines Western Africa as the 16 countries of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Mali, Maurit ...

. The submarine's commander, ''Kapitänleutnant'' Georg-Wilhelm Schulz

Georg-Wilhelm Schulz (10 March 1906 – 5 July 1986) was a German U-boat commander of the Second World War. From September 1939 until retiring from front line service in September 1941, he sank 19 ships for a total of . For this he received the K ...

, provided Lütjens with information about the situation in the area.

On 7 March an aircraft from the battleship , which formed part of the escort for Convoy SL 67

A convoy is a group of vehicles, typically motor vehicles or ships, traveling together for mutual support and protection. Often, a convoy is organized with armed defensive support and can help maintain cohesion within a unit. It may also be used ...

, spotted the German battleships about north of the Cape Verde Islands

, national_anthem = ()

, official_languages = Portuguese

, national_languages = Cape Verdean Creole

, capital = Praia

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, demonym ...

. The battleships sighted the convoy later that day to the north-east of the Cape Verdes, but Lütjens decided to not attack it after ''Malaya'' was identified. Lütjens alerted nearby German submarines to the convoy's location. A plan was developed which involved the submarines sinking ''Malaya'' and the battleships then attacking the merchant ships. Two submarines ambushed the convoy that night, and sank five ships. They did not damage ''Malaya'', however. The German battleships searched for the convoy on 8 May, finding it at 1:30 pm. Lütjens attempted to attack at 5:30 pm, but broke off at high speed when ''Malaya'' was identified. The British were unable to pursue the faster German ships. Force H sortied from Gibraltar on 8 March and escorted Convoy SL 67 until mid-March.

Return to the North Atlantic

Following the encounter with SL 67, Lütjens decided to return to the convoy route between Halifax and the United Kingdom. While sailing north-west ''Scharnhorst'' sank the unescorted merchant vessel SS ''Marathon'' on 9 March. By this time both battleships were suffering from serious mechanical problems. Some of ''Gneisenau''s auxiliary systems needed maintenance that was estimated to take four weeks to complete. ''Scharnhorst'' was in worse condition, as her boilersuperheater

A superheater is a device used to convert saturated steam or wet steam into superheated steam or dry steam. Superheated steam is used in steam turbines for electricity generation, steam engines, and in processes such as steam reforming. There ar ...

s were defective and the pipes that moved steam around the engines had been damaged. The battleships refuelled and received provisions from the supply ships ''Ermland'' and ''Uckermark'' during 11 and 12 March. Lütjens retained both vessels with the battle group to extend the area it could search as it progressed north. Together, they were able to search for shipping along a front.

Ships of the Home Fleet were sortied again in response to the presence of the German battleships in the Atlantic. The battleships and ''Rodney'' were assigned to escort convoys leaving Halifax on 17 and 21 March. Tovey put to sea on ''Nelson'' which, accompanied by the cruiser and two destroyers, took up a position south of Iceland to intercept any raiders that were attempting to return to Germany.

The German force encountered Allied merchant ships south of Cape Race on 15 and 16 March. During 15 March ''Gneisenau'' sank three tankers from Convoy HX 114. Three other tankers, the ''Bianca'', ''San Casimiro'' and ''Polykarp'', were captured and dispatched to German-occupied Europe under the control of prize crew

A prize crew is the selected members of a ship chosen to take over the operations of a captured ship. Prize crews were required to take their prize to appropriate prize courts, which would determine whether the ship's officers and crew had suffici ...

s. The next day the two battleships sank ten merchant vessels from recently dispersed westbound convoys. Many of the Allied ships sent contact reports, and ''Rodney'' sighted ''Gneisenau'' while she was rescuing the survivors of one of the ships she had sunk on the evening of 16 March. ''Gneisenau'' managed to escape from the slower but better armed British battleship. ''Rodney''s crew spotted ''Gneisenau'' but did not identify her. They learned the warship's identity that evening from survivors of a sunken ship. Meanwhile, ''Admiral Hipper'' departed Brest on 15 March to return to Germany via the North Atlantic and Denmark Strait.

The British altered their dispositions following the attacks on 15 and 16 March. The Admiralty did not have any information about Lütjens' intentions, and judged that his force would probably attempt to return to Germany via one of the routes off Iceland. ''King George V'' was dispatched from Halifax to patrol the area where the merchant ships had been sunk, but did not encounter the German battleships. Tovey strengthened the Home Fleet's cruiser patrols of the possible German return routes, and remained to the south of Iceland with much of his fleet. Force H was also ordered by the Admiralty to operate in the North Atlantic. The Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and ...

's (RAF's) Coastal Command

RAF Coastal Command was a formation within the Royal Air Force (RAF). It was founded in 1936, when the RAF was restructured into Fighter, Bomber and Coastal Commands and played an important role during the Second World War. Maritime Aviation ...

undertook intensive air patrols of the Denmark Strait and waters between Iceland and the Faroes between 17 and 20 March.

Voyage to France

Lütjens had received orders on 11 March to cease operations in the North Atlantic by 17 March to support ''Admiral Hipper'' and ''Admiral Scheer''s return to Germany. To provide this support, he was to make a diversion between theAzores

)

, motto =( en, "Rather die free than subjected in peace")

, anthem= ( en, "Anthem of the Azores")

, image_map=Locator_map_of_Azores_in_EU.svg

, map_alt=Location of the Azores within the European Union

, map_caption=Location of the Azores wi ...

and the Canary Islands

The Canary Islands (; es, Canarias, ), also known informally as the Canaries, are a Spanish autonomous community and archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean, in Macaronesia. At their closest point to the African mainland, they are west of Morocc ...

. The German Naval Staff directed him to then return his ships to Brest in France so they could prepare to join a raid into the Atlantic that the battleship ''Bismarck'' and heavy cruiser ''Prinz Eugen'' were scheduled to make in April. ''Scharnhorst'' and ''Gneisenau'' refuelled again from ''Ermland'' and ''Uckermark'' on 18 March, and set course for France the next day.

At 5:30 pm on 20 March a reconnaissance aircraft flying from ''Ark Royal'' spotted the German battleships sailing north-east approximately to the north-west of Cape Finisterre in Spain. The aircraft's radio was defective, which prevented its crew from immediately reporting this sighting. Lütjens turned to the north in an attempt to deceive the British aircrew about his course. This proved successful, as when the aircraft returned to the carrier its crew reported that the German ships were headed north and did not mention their course when first sighted. Somerville's ability to act on this report was further hindered by ''Ark Royal''s failure to immediately pass it on to him. The ''Bianca'' and ''San Casimiro'' were also located by ''Ark Royal''s aircraft on 20 March and were scuttled

Scuttling is the deliberate sinking of a ship. Scuttling may be performed to dispose of an abandoned, old, or captured vessel; to prevent the vessel from becoming a navigation hazard; as an act of self-destruction to prevent the ship from being ...

when ''Renown'' approached them.

After ''Ark Royal'' reported the sighting, the British sought to regain contact with the German battleships and track them. At this time the carrier was about to the south-east of the Germans, which was too great a distance for it to be able to launch an immediate attack. Reconnaissance aircraft operating from ''Ark Royal'' searched for the battleships during the night of 20/21 March and the next morning, but were unable to find them again due to bad weather. Coastal Command reduced its patrols of the waters off Iceland and stepped up coverage of the approaches to the Bay of Biscay

The Bay of Biscay (), known in Spain as the Gulf of Biscay ( es, Golfo de Vizcaya, eu, Bizkaiko Golkoa), and in France and some border regions as the Gulf of Gascony (french: Golfe de Gascogne, oc, Golf de Gasconha, br, Pleg-mor Gwaskogn), ...

.

Tovey's force to the south of Iceland had by this time been reinforced by the battleship and battlecruiser . On 21 March the Admiralty ordered him to proceed south at full speed. Several cruisers were also ordered to head south, a destroyer flotilla sailed from Plymouth

Plymouth () is a port city and unitary authority in South West England. It is located on the south coast of Devon, approximately south-west of Exeter and south-west of London. It is bordered by Cornwall to the west and south-west.

Plymouth ...

and the RAF's Bomber Command

Bomber Command is an organisational military unit, generally subordinate to the air force of a country. The best known were in Britain and the United States. A Bomber Command is generally used for strategic bombing (although at times, e.g. during t ...

established a force of 25 Vickers Wellington

The Vickers Wellington was a British twin-engined, long-range medium bomber. It was designed during the mid-1930s at Brooklands in Weybridge, Surrey. Led by Vickers-Armstrongs' chief designer Rex Pierson; a key feature of the aircraft is its g ...

bombers that could be sent against the battleships. By this time the only way for the British ships to intercept Lütjens' force before they came under the protection of land-based German aircraft in France was for ''Ark Royal''s aircraft to damage one or both of them. This was made impossible by the mishandling of the sighting on 20 March and poor flying weather on that and the subsequent day.

The crew of a Coastal Command Lockheed Hudson

The Lockheed Hudson is a light bomber and coastal reconnaissance aircraft built by the American Lockheed Aircraft Corporation. It was initially put into service by the Royal Air Force shortly before the outbreak of the Second World War and prim ...

detected the German battleships by radar when they were within of the French coast on the evening of 21 March. By this time it was not possible for the British to attack them, and due to the evasive course Lütjens was taking the British were unable to anticipate which French port he was heading for. The torpedo boats ''Jaguar'' and ''Iltis'' escorted the battleships into Brest, where they anchored on 22 March. The captured tanker ''Polykarp'' docked at Bordeaux

Bordeaux ( , ; Gascon oc, Bordèu ; eu, Bordele; it, Bordò; es, Burdeos) is a port city on the river Garonne in the Gironde department, Southwestern France. It is the capital of the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region, as well as the prefectur ...

two days later. Allied seamen who had been captured from sunken ships were paraded through Brest before being sent to prisoner of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of wa ...

camps in Germany. ''Admiral Hipper'' reached Kiel on 28 March, and ''Admiral Scheer'' docked there two days later.

Aftermath

Assessments

Operation Berlin was the most successful of the surface raiding missions throughout the war. Lütjens' force sank or captured 22 ships totalling . The Allied convoy routes across the North Atlantic were badly disrupted, which hindered the flow of supplies to the United Kingdom. By diverting the Home Fleet, the operation also allowed ''Admiral Hipper'' and ''Admiral Scheer'' to safely return to Germany. The German Naval Staff and Raeder believed that the success of Operation Berlin and the other raids conducted by surface vessels during 1940 and early 1941 demonstrated that further such attacks remained viable. Raeder travelled to Brest on 23 March, and asked Lütjens to lead the next raid from the ''Bismarck''. Several changes were made to surface raiding tactics based on lessons learned from Operation Berlin. The prohibition against engaging forces of equal strength was softened to allow battleships to engage escorting warships while their accompanying cruisers attacked the convoy. As the intelligence on convoy routes and timings had proven unreliable and Lütjens experienced difficulty searching for convoys, it was decided to station submarines at strategic locations to scout for Allied ships. Tactics that had proven successful, such as keeping the ships of the battle group together and using supply vessels to search for convoys, were retained. The British were disappointed by their performance during early 1941. While assigning battleships to protect convoys had prevented disastrous losses, the German surface raiders had greatly disrupted the convoy system and not suffered any losses. A key lesson was the need to strengthen patrols of the seas to the north and south of Iceland to detect German raiders as they attempted to enter the Atlantic. This led to additional cruisers being assigned to the area.Subsequent operations

Coastal Command aircraft located the two German battleships at Brest on 28 March after six days of intensive searches of French ports. Once the battleships were confirmed to be in port, the Home Fleet returned to its bases for a brief period and the Atlantic convoy system returned to its normal routings. Due to the threat the force at Brest posed, the Home Fleet

Coastal Command aircraft located the two German battleships at Brest on 28 March after six days of intensive searches of French ports. Once the battleships were confirmed to be in port, the Home Fleet returned to its bases for a brief period and the Atlantic convoy system returned to its normal routings. Due to the threat the force at Brest posed, the Home Fleet blockade

A blockade is the act of actively preventing a country or region from receiving or sending out food, supplies, weapons, or communications, and sometimes people, by military force.

A blockade differs from an embargo or sanction, which are le ...

d the port and provided powerful escorts to convoys. Submarines were stationed off Brest, and Coastal Command closely monitored it. The Home Fleet maintained three or four naval task forces at all times to intercept the German battleships if they left Brest. Force H was also reinforced and patrolled the routes used by north and southbound convoys. Command of the forces operating west of France alternated between Tovey and Somerville.

The RAF repeatedly made large attacks that targeted the German battleships at Brest. The first raid took place on the night of 30/31 March. On 6 April a British aircraft torpedoed ''Gneisenau''. She was hit by four bombs during another raid on 10 April. It took until the end of 1941 for the damage inflicted by these attacks to be repaired. ''Scharnhorst'' required repairs to her boiler

A boiler is a closed vessel in which fluid (generally water) is heated. The fluid does not necessarily boil. The heated or vaporized fluid exits the boiler for use in various processes or heating applications, including water heating, central h ...

s which rendered her unable to participate in Operation Rheinübung

Operation Rheinübung ("Exercise Rhine") was the sortie into the Atlantic by the new German battleship and heavy cruiser on 18–27 May 1941, during World War II. This operation to block Allied shipping to the United Kingdom culminated w ...

, the raid into the Atlantic undertaken by ''Bismarck'' and ''Prinz Eugen'' during May.

Lütjens led Operation Rheinübung from the battleship, and sank HMS ''Hood'' on 24 May. He was killed when ''Bismarck'' was destroyed by the Home Fleet on 27 May. Guided by Ultra intelligence, the British also sank seven of the eight supply ships that had been sent into the Atlantic to support ''Bismarck''. Following this defeat Hitler forbade further battleship raids into the Atlantic. On 13 June RAF aircraft torpedoed the cruiser ''Lützow'' while she was trying to break out into the Atlantic. This was the last raid into the Atlantic that was attempted by the heavy warships. As a result, Operation Berlin was the final success against Allied shipping achieved by German warships in the North Atlantic. Submarines formed the main element of the German anti-shipping campaign for the remainder of the war.

After the repairs to her boilers were completed, ''Scharnhorst'' was transferred to La Pallice

La Pallice (also known as ''grand port maritime de La Rochelle'') is the commercial deep-water port of La Rochelle, France.

During the Fall of France, on 19 June 1940, approximately 6,000 Polish soldiers in exile under the command of Stanisła ...

on 21 July as it was further from the British bomber bases and believed to be at less risk of air attacks. She was hit by five bombs during an air raid on 24 July, and required repairs in Brest that were not completed until 15 January 1942. In line with a decision made by Hitler in September 1941 to concentrate the surface warships in Norway, the ''Scharnhorst''-class battleships were ordered to return to Germany via the English Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" (Cotentinais) or ( Jèrriais), (Guernésiais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, Môr Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Kana ...

. During the "Channel Dash

The Channel Dash (german: Unternehmen Zerberus, Operation Cerberus) was a German naval operation during the Second World War. (Cerberus), a three-headed dog of Greek mythology who guards the gate to Hades. A (German Navy) squadron comprising ...

" they and ''Prinz Eugen'' departed Brest under heavy air and naval escort on 11 February 1942. Both battleships were damaged by mines, but reached Germany.

While under repair at Kiel, ''Gneisenau'' was badly damaged by an air raid on the night of 26/27 February and never reentered service. ''Scharnhorst'' was deployed to Norway in 1943. As part of an attempted raid against an Allied Arctic convoy

The Arctic convoys of World War II were oceangoing convoys which sailed from the United Kingdom, Iceland, and North America to northern ports in the Soviet Union – primarily Arkhangelsk (Archangel) and Murmansk in Russia. There were 78 convoys ...

, she was sunk by the Home Fleet on 26 December 1943 during the Battle of the North Cape

The Battle of the North Cape was a Second World War naval battle that occurred on 26 December 1943, as part of the Arctic campaign. The , on an operation to attack Arctic Convoys of war materiel from the Western Allies to the Soviet Union, wa ...

.

Historiography

Writing in 1954, the British official historian Stephen Roskill stated that Operation Berlin "had been skilfully planned, well co-ordinated with the movements of other raiders and successfully sustained by the supply ships sent out for that purpose" and that the Germans were correct to be pleased with its outcomes. He also noted that the operations conducted by German surface raiders in the North Atlantic between February and March 1941 was the only period in the war in which surface warships were able to "threaten the whole structure of our maritime control". In contrast, the British naval historianRichard Woodman

Captain Richard Martin Woodman LVO (born 1944) is an English novelist and naval historian who retired in 1997 from a 37-year nautical career, mainly working for Trinity House, to write full-time.

Writing

His main work is 14 novels about the ca ...

judged in 2004 that Operation Berlin did not have significant strategic implications as Lütjens was unable to cripple Allied shipping in the North Atlantic and only attacked a single eastbound HX convoy. Angus Konstam noted in 2021 that the number of ships sunk by German surface raiders was dwarfed by those accounted for by submarines. He concluded that the strategy of sending surface raiders into the Atlantic was faulty as the resources required to build and crew these ships would have produced better results if they had been allocated to the submarine force.

Roskill attributed the British failure to intercept the raiders to bad luck. He judged that the Royal Navy's performance was superior to that in previous such operations, and demonstrated that it now posed a strong threat to surface raiders. Roskill also observed that assigning battleships to escort convoys "had certainly saved two of them from disaster". The historian Graham Rys-Jones reached a similar conclusion in 1999, noting that Lütjens' success in evading the British was "one of the less helpful lessons of Operation Berlin" as it convinced Raeder that ''Bismarck'' could safely operate in the North Atlantic.

Historians agree that Raeder's decision to send the two battleships to Brest was a mistake. Lisle A. Rose has noted that by doing so he "placed the big ships under the thumb of Royal Air Force bombers and divided the German battle fleet between the Channel and the Baltic at just the time that new construction cried out for a concentration of forces". Rose notes that this error led to ''Bismarck'' and ''Prinz Eugen'' lacking the support of the ''Scharnhorst''-class battleships during their sortie in May 1941. Lars Hellwinkel has noted that Brest lacked the facilities to rapidly repair the battleships at the end of Operation Berlin, and the vulnerability of French ports to British air attack meant that none of the major warships based there would have been able to conduct any attacks after ''Bismarck''s loss. Raeder acknowledged his error after the war, noting that the forces needed to adequately defend the battleships at Brest had not been available.

References

Citations

Works consulted

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{cite book , last1=Woodman , first1=Richard, author1-link=Richard Woodman , title=The Real Cruel Sea: The Merchant Navy in the Battle of the Atlantic, 1939–1943 , date=2004 , publisher=John Murray , location=London , isbn=978-0-7195-6599-1 Conflicts in 1941Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitue ...

Maritime incidents in 1941

Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitue ...

Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitue ...

January 1941 events

February 1941 events

March 1941 events