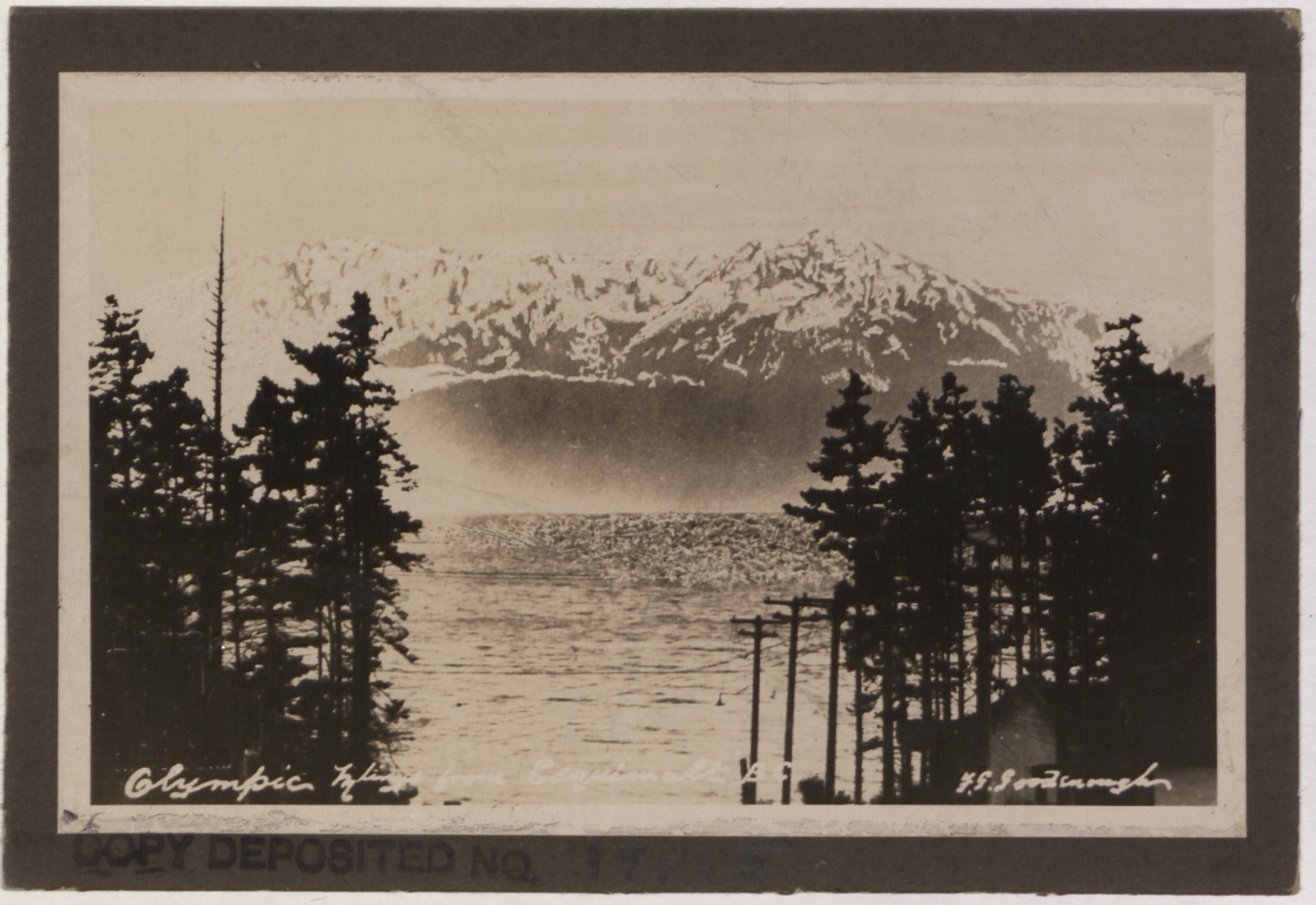

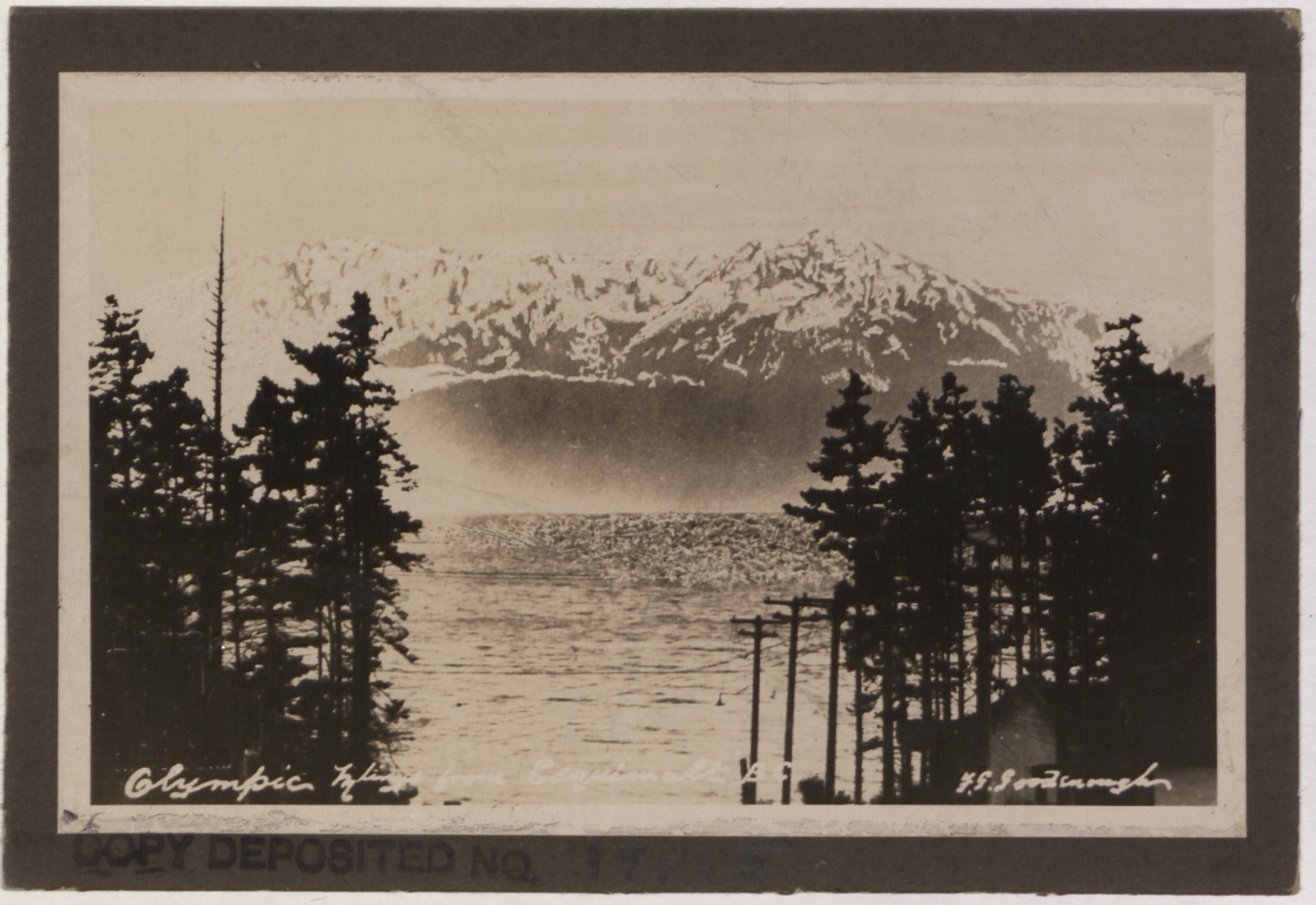

Olympic Range on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Olympic Mountains are a

mountain range

A mountain range or hill range is a series of mountains or hills arranged in a line and connected by high ground. A mountain system or mountain belt is a group of mountain ranges with similarity in form, structure, and alignment that have arise ...

on the Olympic Peninsula

The Olympic Peninsula is a large arm of land in western Washington that lies across Puget Sound from Seattle, and contains Olympic National Park. It is bounded on the west by the Pacific Ocean, the north by the Strait of Juan de Fuca, and the ...

of the Pacific Northwest

The Pacific Northwest (sometimes Cascadia, or simply abbreviated as PNW) is a geographic region in western North America bounded by its coastal waters of the Pacific Ocean to the west and, loosely, by the Rocky Mountains to the east. Though ...

of the United States. The mountain

A mountain is an elevated portion of the Earth's crust, generally with steep sides that show significant exposed bedrock. Although definitions vary, a mountain may differ from a plateau in having a limited Summit (topography), summit area, and ...

s, part of the Pacific Coast Ranges

The Pacific Coast Ranges (officially gazetted as the Pacific Mountain System in the United States) are the series of mountain ranges that stretch along the West Coast of North America from Alaska south to Northern and Central Mexico. Although the ...

, are not especially high – Mount Olympus

Mount Olympus (; el, Όλυμπος, Ólympos, also , ) is the highest mountain in Greece. It is part of the Olympus massif near the Thermaic Gulf of the Aegean Sea, located in the Olympus Range on the border between Thessaly and Macedonia, be ...

is the highest at ; however, the eastern slopes rise out of Puget Sound

Puget Sound ( ) is a sound of the Pacific Northwest, an inlet of the Pacific Ocean, and part of the Salish Sea. It is located along the northwestern coast of the U.S. state of Washington. It is a complex estuarine system of interconnected ma ...

from sea level and the western slopes are separated from the Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the continen ...

by the low-lying wide Pacific Ocean coastal plain

A coastal plain is flat, low-lying land adjacent to a sea coast. A fall line commonly marks the border between a coastal plain and a piedmont area. Some of the largest coastal plains are in Alaska and the southeastern United States. The Gulf Coa ...

. The western slopes are the wettest place in the 48 contiguous states. Most of the mountains are protected within the bounds of Olympic National Park

Olympic National Park is a United States national park located in the State of Washington, on the Olympic Peninsula. The park has four regions: the Pacific coastline, alpine areas, the west-side temperate rainforest, and the forests of the drier ...

and adjoining segments of the Olympic National Forest

Olympic National Forest is a U.S. National Forest located in Washington, USA. With an area of , it nearly surrounds Olympic National Park and the Olympic Mountain range. Olympic National Forest contains parts of Clallam, Grays Harbor, Jefferso ...

.

The mountains are located in western Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered on ...

in the United States, spread out across four counties: Clallam

Klallam (also Clallam, although the spelling with "K" is preferred in all four modern Klallam communities) refers to four related indigenous Native American/First Nations communities from the Pacific Northwest of North America. The Klallam cult ...

, Grays Harbor Grays Harbor is an estuary, estuarine bay located north of the mouth of the Columbia River, on the southwest Pacific coast of Washington (U.S. state), Washington state, in the United States of America. It is a ria, which formed at the end of the l ...

, Jefferson Jefferson may refer to:

Names

* Jefferson (surname)

* Jefferson (given name)

People

* Thomas Jefferson (1743–1826), third president of the United States

* Jefferson (footballer, born 1970), full name Jefferson Tomaz de Souza, Brazilian foo ...

and Mason

Mason may refer to:

Occupations

* Mason, brick mason, or bricklayer, a craftsman who lays bricks to construct brickwork, or who lays any combination of stones, bricks, cinder blocks, or similar pieces

* Stone mason, a craftsman in the stone-cut ...

. Physiographically, they are a section of the larger Pacific Border province

The Pacific Border province is a physiographic province of the Physiographic regions of the world physical geography system.

Description

The Pacific Border province encompasses most of the North American Pacific Coast, with the southern end at ...

, which is in turn a part of the larger Pacific Mountain System

The Pacific Coast Ranges (officially gazetted as the Pacific Mountain System in the United States) are the series of mountain ranges that stretch along the West Coast of North America from Alaska south to Northern and Central Mexico. Although the ...

.

Geography

The Olympics have the form of a cluster of steep-sided peaks surrounded by heavily forested foothills and incised by deep valleys. They are surrounded by water on three sides, separated from the Pacific by the wide coastal plain. The general form of the range is more or less circular, or somewhat horseshoe-shaped, and the drainage pattern is radial. Rivers radiate outwards to all sides. Clockwise from windward to leeward, the major watersheds are:Satsop

Satsop is a census-designated place (CDP) in Grays Harbor County, Washington, United States. The population was 675 at the 2010 census, up from 619 at the 2000 census.

Geography

Satsop is located in southeastern Grays Harbor County on the Sats ...

, Wynoochee, Humptulips

Humptulips is a census-designated place (CDP) in Grays Harbor County, Washington, United States. The population of the CDP was 255 according to the 2010 census.

Etymology

The name Humptulips was the name of a band of the Chehalis tribe who li ...

, Quinault Quinault may refer to:

* Quinault people, an Indigenous people of the Pacific Northwest Coast

**Quinault Indian Nation, a federally recognized tribe

**Quinault language, their language

People

* Quinault family of actors, including

* Jean-Baptis ...

, Queets

Queets is an unincorporated community and census-designated place (CDP) in Grays Harbor and Jefferson counties, Washington, United States. The population was 174 at the 2010 census. The primary residents of the community are Native Americans of ...

, Hoh

Water () is a polar inorganic compound that is at room temperature a tasteless and odorless liquid, which is nearly colorless apart from an inherent hint of blue. It is by far the most studied chemical compound and is described as the "univer ...

, Bogachiel, Sol Duc (all flowing west into the Pacific Ocean; with the Satsop and Wynoochee by way of the Chehalis River, and the Humptulips by way of Grays Harbor Grays Harbor is an estuary, estuarine bay located north of the mouth of the Columbia River, on the southwest Pacific coast of Washington (U.S. state), Washington state, in the United States of America. It is a ria, which formed at the end of the l ...

at the mouth of the Chehalis River), Lyre

The lyre () is a stringed musical instrument that is classified by Hornbostel–Sachs as a member of the lute-family of instruments. In organology, a lyre is considered a yoke lute, since it is a lute in which the strings are attached to a yoke ...

, Elwha, Dungeness

Dungeness () is a headland on the coast of Kent, England, formed largely of a shingle beach in the form of a cuspate foreland. It shelters a large area of low-lying land, Romney Marsh. Dungeness spans Dungeness Nuclear Power Station, the hamlet ...

(all flowing north into the Strait of Juan de Fuca

The Strait of Juan de Fuca (officially named Juan de Fuca Strait in Canada) is a body of water about long that is the Salish Sea's outlet to the Pacific Ocean. The international boundary between Canada and the United States runs down the centre ...

), Big Quilcene, Dosewallips, Duckabush, Hamma Hamma, and Skokomish (all flowing east into Hood Canal

Hood Canal is a fjord forming the western lobe, and one of the four main basins,Mount Olympus

Mount Olympus (; el, Όλυμπος, Ólympos, also , ) is the highest mountain in Greece. It is part of the Olympus massif near the Thermaic Gulf of the Aegean Sea, located in the Olympus Range on the border between Thessaly and Macedonia, be ...

– highest point, eight glaciers

* Mount Constance

Mount Constance is a peak in the Olympic Mountains of Washington and the third highest in the range. It is the most visually prominent peak on Seattle's western skyline. Despite being almost as tall as the ice-clad Mount Olympus to the west, Mou ...

– largest peak visible from Seattle

* Mount Townsend

Mount Townsend, a mountain in the Main Range of the Great Dividing Range, is located in the Snowy Mountains region of New South Wales, Australia.

With an elevation of above sea level, Mount Townsend is the second-highest peak of mainland ...

– highly visible from Seattle at far northeast of the Olympics (technically in the Buckhorn Wilderness

The Buckhorn Wilderness is a mountainous wilderness area on the northeastern Olympic Peninsula in Washington, USA. Named after Buckhorn Mountain (), the wilderness abuts the eastern boundary of Olympic National Park which includes nearby Mount ...

)

* Mount Anderson – West Peak of Mount Anderson is the hydrographic apex of the Olympic Mountains: From this peak, rivers flow outward to the Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the continen ...

, the Strait of Juan de Fuca

The Strait of Juan de Fuca (officially named Juan de Fuca Strait in Canada) is a body of water about long that is the Salish Sea's outlet to the Pacific Ocean. The international boundary between Canada and the United States runs down the centre ...

, and Hood Canal

Hood Canal is a fjord forming the western lobe, and one of the four main basins,The Brothers – double peak visible from Seattle

* Mount Deception

*

The mountains support a variety of different ecosystems, varying by elevation and relative east–west location, which influences the local climate, primarily precipitation.

The mountains support a variety of different ecosystems, varying by elevation and relative east–west location, which influences the local climate, primarily precipitation.

Moving up in elevation and moisture availability is the silver fir zone, up to about . This zone gets more precipitation, and more of it as snow, than the lower, warmer, drier western hemlock zone. The cold and the snowpack combine to limit growth of lower-elevation plants. On the other hand, silver fir is less drought tolerant and less fire tolerant than either Douglas-fir or western hemlock. Slide alder (''Alnus viridis sinuata'') grows in snow-creep areas and avalanche chutes, along with yellow-cedar. Meadows of

Moving up in elevation and moisture availability is the silver fir zone, up to about . This zone gets more precipitation, and more of it as snow, than the lower, warmer, drier western hemlock zone. The cold and the snowpack combine to limit growth of lower-elevation plants. On the other hand, silver fir is less drought tolerant and less fire tolerant than either Douglas-fir or western hemlock. Slide alder (''Alnus viridis sinuata'') grows in snow-creep areas and avalanche chutes, along with yellow-cedar. Meadows of  Subalpine meadows in the Olympic mountains are of 5 types. Heath shrub meadows are dominated by ericaceous huckleberries and heathers. Lush herbaceous meadows are typified by Sitka valerian and showy sedge. Drier areas or those with longer snow cover grow dwarf sedge (''

Subalpine meadows in the Olympic mountains are of 5 types. Heath shrub meadows are dominated by ericaceous huckleberries and heathers. Lush herbaceous meadows are typified by Sitka valerian and showy sedge. Drier areas or those with longer snow cover grow dwarf sedge (''

* Olympic Mountain milkvetch (''Astragalus australis'' var. ''olympicus'')

* Piper's bellflower (''Campanula piperi'')

* Spotted coralroot (''Corallorhiza maculata'' var. ''ozettensis'')

*

* Olympic Mountain milkvetch (''Astragalus australis'' var. ''olympicus'')

* Piper's bellflower (''Campanula piperi'')

* Spotted coralroot (''Corallorhiza maculata'' var. ''ozettensis'')

*

Available online through the Washington State Library's Classics in Washington History collection

* Olympic Mountain Rescue, ''Climber's Guide to the Olympic Mountains'' (Seattle: The Mountaineers, 1979) * Wood, R.L., ''Across the Olympic Mountains: The Press Expedition, 1889–90'' (Mountaineering Books, 1989)

Park History

Photographic albums and text documenting the Mountaineers official annual outings undertaken by club members from 1907 to 1951, primarily on the Olympic Peninsula. Includes 7 Mount Olympus albums (c. 1905–1951). {{Authority control Pacific Coast Ranges Physiographic sections Mountain ranges of Washington (state) Landforms of Jefferson County, Washington Landforms of Clallam County, Washington

Mount Washington

Mount Washington is the highest peak in the Northeastern United States at and the most topographically prominent mountain east of the Mississippi River.

The mountain is notorious for its erratic weather. On the afternoon of April 12, 1934, ...

* Mount Angeles

Mount Angeles is located just south of Port Angeles, Washington in the Olympic National Park. It is the highest peak in the Hurricane Ridge area. The summit, which offers panoramic views of the Strait of Juan de Fuca and many of the peaks of th ...

* Mount Stone

* Mount Ellinor

Mount Ellinor is a peak in the Olympic Mountains of Washington, United States. It is located in an area designated as the Mount Skokomish Wilderness. The mountain is a popular day hike in the summer months; the summit is reachable via a steep-bu ...

Other summits:

* Boulder Peak – Peak located in the Lake Crescent

Lake Crescent is a deep lake located entirely within Olympic National Park in Clallam County, Washington, United States, approximately west of Port Angeles on U.S. Route 101 and nearby to the small community of Piedmont. At an official maxim ...

and Elwha River

The Elwha River is a river on the Olympic Peninsula in the U.S. state of Washington (state), Washington. From its source at Elwha snowfinger in the Olympic Mountains, it flows generally north to the Strait of Juan de Fuca. Most of the river's cou ...

area

* Mount Storm King – located just to the south of Lake Crescent

Lake Crescent is a deep lake located entirely within Olympic National Park in Clallam County, Washington, United States, approximately west of Port Angeles on U.S. Route 101 and nearby to the small community of Piedmont. At an official maxim ...

* Hurricane Ridge – road accessible summit near Port Angeles

Other features

*Bailey Range

The Bailey Range is a mountain range located within Olympic National Park in Washington state.

Description

The Bailey Range is a subrange of the Olympic Mountains. These remote mountains are situated within the Daniel J. Evans Wilderness, but ...

* Lost Pass

Protected areas

A large portion of the range is contained within the Olympic National Park. Of this portion, 95% is part of theDaniel J. Evans Wilderness

Daniel is a masculine given name and a surname of Hebrew origin. It means "God is my judge"Hanks, Hardcastle and Hodges, ''Oxford Dictionary of First Names'', Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, , p. 68. (cf. Gabriel—"God is my strength" ...

.

The national park is surrounded on the south, east, and northwest sides by the Olympic National Forest, with five wilderness areas, and on the southwest side by the Clearwater State Forest with one Natural Area Preserve (Washington Department of Natural Resources), and the Quinault Indian Reservation. State parks and wildlife areas occur in the lower elevations.

Climate

Precipitation varies greatly throughout the range, from the wet western slopes to the arid eastern ridges. Mount Olympus, nearly tall, is a mere from the Pacific Ocean, one of the steepest reliefs globally and accounting for the high precipitation of the area, as much as of snow and rain on Mount Olympus. of rain falls on theHoh Rainforest

Hoh Rainforest is one of the largest temperate rainforests in the U.S., located on the Olympic Peninsula in western Washington state. It includes of low elevation forest along the Hoh River. The Hoh River valley was formed thousands of years ag ...

annually, receiving the most precipitation of anywhere in the contiguous United States. Areas to the northeast of the mountains are located in a rain shadow

A rain shadow is an area of significantly reduced rainfall behind a mountainous region, on the side facing away from prevailing winds, known as its leeward side.

Evaporated moisture from water bodies (such as oceans and large lakes) is carrie ...

and receive as little as of precipitation. Annual precipitation increases to about on the edges of the rain shadow around Port Townsend, the San Juan Islands, and Everett. 80% of precipitation falls during the winter. On the coastal plain, the winter temperature stays between . During the summer it warms up to stay between .

The large number of snowfields and glacier

A glacier (; ) is a persistent body of dense ice that is constantly moving under its own weight. A glacier forms where the accumulation of snow exceeds its Ablation#Glaciology, ablation over many years, often Century, centuries. It acquires dis ...

s, reaching down to 1,500 m (5,000 ft) above sea level, is a consequence of the high precipitation. There are about 184 glaciers crowning the Olympics peaks. The most prominent glaciers are those on Mount Olympus

Mount Olympus (; el, Όλυμπος, Ólympos, also , ) is the highest mountain in Greece. It is part of the Olympus massif near the Thermaic Gulf of the Aegean Sea, located in the Olympus Range on the border between Thessaly and Macedonia, be ...

covering approximately . Beyond the Olympic complex are the glaciers of Mount Carrie

Mount Carrie is a mountain summit located within Olympic National Park in Clallam County of Washington state. Mt. Carrie is the highest point in the Bailey Range which is a subrange of the Olympic Mountains. With a good eye and clear weather, ...

, the Bailey Range

The Bailey Range is a mountain range located within Olympic National Park in Washington state.

Description

The Bailey Range is a subrange of the Olympic Mountains. These remote mountains are situated within the Daniel J. Evans Wilderness, but ...

, Mount Christie, and Mount Anderson.

Geology

The Olympics are made up of obductedclastic

Clastic rocks are composed of fragments, or clasts, of pre-existing minerals and rock. A clast is a fragment of geological detritus,Essentials of Geology, 3rd Ed, Stephen Marshak, p. G-3 chunks, and smaller grains of rock broken off other rocks ...

wedge material and oceanic crust. They are primarily Eocene

The Eocene ( ) Epoch is a geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 56 to 33.9 million years ago (mya). It is the second epoch of the Paleogene Period (geology), Period in the modern Cenozoic Era (geology), Era. The name ''Eocene' ...

sandstones, turbidite

A turbidite is the geologic deposit of a turbidity current, which is a type of amalgamation of fluidal and sediment gravity flow responsible for distributing vast amounts of clastic sediment into the deep ocean.

Sequencing

Turbidites were ...

s, and basalt

Basalt (; ) is an aphanite, aphanitic (fine-grained) extrusive igneous rock formed from the rapid cooling of low-viscosity lava rich in magnesium and iron (mafic lava) exposed at or very near the planetary surface, surface of a terrestrial ...

ic oceanic crust. Unlike the Cascades, the Olympic Mountains are not volcanic, and contain no granite.

Millions of years ago, vents and fissures opened under the Pacific Ocean and lava flowed forth, creating huge underwater mountains and ranges called seamount

A seamount is a large geologic landform that rises from the ocean floor that does not reach to the water's surface (sea level), and thus is not an island, islet or cliff-rock. Seamounts are typically formed from extinct volcanoes that rise abru ...

s. The Farallon tectonic plate

Plate tectonics (from the la, label=Late Latin, tectonicus, from the grc, τεκτονικός, lit=pertaining to building) is the generally accepted scientific theory that considers the Earth's lithosphere to comprise a number of large te ...

that formed a part of the Pacific Ocean floor (separate from the Pacific plate) inched eastward toward North America about 35 million years ago and most of the sea floor subducted beneath the continental land mass of the North America plate. Some of the sea floor, however, was scraped off and jammed against the mainland, creating the dome that was the forerunner of today's Olympics. In this particular case, the future Olympics were being jammed into a corner created by the Vancouver Island and North Cascades microcontinents attached to the western edge of the North America plate. This is thought to be the origin of the curved shape of the Olympic Basaltic Horseshoe, an arc of basalt running east along the Strait of Juan de Fuca, south along Hood Canal, and then west to Lake Quinault. Thrust-faulting northeast into the Vancouver Island/North Cascades corner pushes Olympic rock upward and southwestward, resulting in strata that appear to be standing on edge and that intermix with strata of different mineral composition. All this occurred under water; the Olympics began to rise above the sea only 10–20 million years ago.

The Olympics were shaped in the Pleistocene

The Pleistocene ( , often referred to as the ''Ice age'') is the geological Epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 2,580,000 to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was fina ...

era by both alpine

Alpine may refer to any mountainous region. It may also refer to:

Places Europe

* Alps, a European mountain range

** Alpine states, which overlap with the European range

Australia

* Alpine, New South Wales, a Northern Village

* Alpine National Pa ...

and continental

Continental may refer to:

Places

* Continent, the major landmasses of Earth

* Continental, Arizona, a small community in Pima County, Arizona, US

* Continental, Ohio, a small town in Putnam County, US

Arts and entertainment

* ''Continental'' (al ...

glaciers advancing and retreating multiple times. The valleys of the Hoh, Queets, and Quinault rivers are typical U-shaped valleys carved by advancing alpine glaciers. Piles of talus and rockfall were created by retreating alpine glaciers. In the high mountains, the major rivers have their headwaters in alpine glacially carved cirque

A (; from the Latin word ') is an amphitheatre-like valley formed by glacial erosion. Alternative names for this landform are corrie (from Scottish Gaelic , meaning a pot or cauldron) and (; ). A cirque may also be a similarly shaped landform ...

s. During the Orting, followed by the Stuck, the Salmon Springs, and the Fraser glaciations, the vast continental Cordilleran Ice Sheet descended from Alaska south through British Columbia to the Olympics. The ice split into the Juan de Fuca

Juan de Fuca (10 June 1536, Cefalonia 23 July 1602, Cefalonia)Greek Consulate of Vancouver,Greek Pioneers: Juan de Fuca. was a Greeks, Greek maritime pilot, pilot who served Philip II of Spain, PhilipII of Spanish Empire, Spain. He is best know ...

and Puget ice lobes, as they encountered the resistant Olympic Mountains, carving out the current waterways and advanced as far south as present day Olympia. Ice flowed up the river valleys as far as , carrying granitic glacial erratic

A glacial erratic is glacially deposited rock differing from the type of rock native to the area in which it rests. Erratics, which take their name from the Latin word ' ("to wander"), are carried by glacial ice, often over distances of hundred ...

s with it.

Ecology

The mountains support a variety of different ecosystems, varying by elevation and relative east–west location, which influences the local climate, primarily precipitation.

The mountains support a variety of different ecosystems, varying by elevation and relative east–west location, which influences the local climate, primarily precipitation.

Flora

Olympic forests are coniferous forests, unique among mesic temperate forests in their almost complete dominance by conifers rather than by hardwoods. The hardwood:conifer timber volume ratio is 1:1,000 in the maritime Pacific Northwest. Another unique feature of Olympic forests is the size and longevity of the dominant tree species. Every coniferous genus represented here is represented by its largest and longest-lived species, and some of its second and third ranked species as well. Biomass accumulations are among the highest in the temperate forest zones. Dominance of conifers is thought to be a result of the amount and timing of precipitation. The dry summers limit the growth of deciduous trees, such as most hardwoods. Evergreens, such as most conifers, are able to take advantage of the winter precipitation by continuing to photosynthesize through fall, winter and early spring, when deciduous trees are not able to photosynthesize. No deciduous conifers occur in the Olympics; larch trees occur in the much-drier eastern Cascades, but not in the Olympics or western Cascades. There is only one species of evergreen hardwood, themadrone

''Arbutus'' is a genus of 12 accepted speciesAct. Bot. Mex no.99 Pátzcuaro abr. 2012.''Arbutus bicolor''/ref> of flowering plants in the family Ericaceae, native to warm temperate regions of the Mediterranean, western Europe, the Canary Islan ...

.

The great size and age of conifers here is thought to be a result of the relative lack of frequent windstorms like tropical cyclone

A tropical cyclone is a rapidly rotating storm system characterized by a low-pressure center, a closed low-level atmospheric circulation, strong winds, and a spiral arrangement of thunderstorms that produce heavy rain and squalls. Depend ...

s.

Along the western flanks of the mountains the increased orographic precipitation supports temperate rain forests in the Quinault, Queets, Hoh, and Bogachiel river

The Bogachiel River () is a river of the Olympic Peninsula in the U.S. state of Washington (state), Washington. It originates near Bogachiel Peak, flows west through the mountains of Olympic National Park. After emerging from the park it joins the ...

valleys at low elevations. Protection by Olympic National Park, has allowed these rain forests to retain old growth trees, which supports a varied ecosystem. The Olympic rain forests are composed primarily of Sitka spruce

''Picea sitchensis'', the Sitka spruce, is a large, coniferous, evergreen tree growing to almost tall, with a trunk diameter at breast height that can exceed 5 m (16 ft). It is by far the largest species of spruce and the fifth-larg ...

and western hemlock

''Tsuga heterophylla'', the western hemlock or western hemlock-spruce, is a species of hemlock native to the west coast of North America, with its northwestern limit on the Kenai Peninsula, Alaska, and its southeastern limit in northern Sonoma ...

, as are the surrounding lowland Sitka spruce forests, but are distinct in having a relative abundance of groves of bigleaf maple

''Acer macrophyllum'', the bigleaf maple or Oregon maple, is a large deciduous tree in the genus '' Acer''.

It is native to western North America, mostly near the Pacific coast, from southernmost Alaska to southern California. Some stands are al ...

and vine maple

''Acer circinatum'', the vine maple, is a species of maple native to western North America.

Description

It most commonly grows as a large shrub growing to around tall, but it will occasionally form a small to medium-sized tree, exceptionall ...

, which support large epiphytic communities of mosses, lichens, ferns, and clubmosses; an abundance of nurse logs on the forest floor; a relatively open forest canopy and sparse shrub layer; and a dense moss layer on the forest floor. The rain forests are the wintering grounds for herds of Roosevelt elk

The Roosevelt elk (''Cervus canadensis roosevelti)'', also known commonly as the Olympic elk and Roosevelt's wapiti, is the largest of the four surviving subspecies of elk (''Cervus canadensis'') in North America by body mass (although by antle ...

and it is thought that browsing by the elk is responsible for the open shrub layer and the dominance of Sitka spruce over western hemlock.

The rain forests are just one type of forest found in the Olympic Mountains. Franklin and Dyrness set out 5 forest zones: Sitka spruce, western hemlock, silver fir

Silver fir is a common name for several trees and may refer to:

*''Abies alba'', native to Europe

*''Abies amabilis'', native to western North America

*''Abies pindrow

''Abies pindrow'', the pindrow fir or west Himalayan fir, is a fir native ...

, mountain hemlock

''Tsuga mertensiana'', known as mountain hemlock, is a species of hemlock native to the west coast of North America, found between Southcentral Alaska and south-central California.

Description

''Tsuga mertensiana'' is a large evergreen conifer ...

, and subalpine parkland. Other authors include a sixth, Douglas-fir zone. Different plant associations are typical of one or more forest zones. For instance, the rain forest plant association described above is a member of the Sitka spruce forest zone.

The Sitka spruce zone is a lowland zone dominated by Sitka spruce and western hemlock. Precipitation is high, winters are mild, elevations are low. This forest zone is typically found at very low elevations on the western coastal plain and not in mountainous areas, although it can be found as high as .

The lower elevations of the Olympic mountains, from roughly up to – , feature the western hemlock zone, so-called because in most of the zone, the climax tree species would be western hemlock, even though much of the area is dominated by Douglas-fir

The Douglas fir (''Pseudotsuga menziesii'') is an evergreen conifer species in the pine family, Pinaceae. It is native to western North America and is also known as Douglas-fir, Douglas spruce, Oregon pine, and Columbian pine. There are three va ...

. The reason for this is that Douglas-fir is an early seral species, and reproduces primarily after disturbances such as fire, logging, landslides, and windstorms. Western hemlock does not reproduce well on disturbed, exposed soil but germinates under the canopy of Douglas-fir, eventually overtaking the forest by shading out the Douglas-fir, which cannot reproduce in shade. In this zone, despite the high annual precipitation, drought stress in summer is sufficiently severe to limit growth of many species, such as Sitka spruce. Hardwoods such as bigleaf maple, willows, and red alder

''Alnus rubra'', the red alder,

is a deciduous broadleaf tree native to western North America (Alaska, Yukon, British Columbia, Washington, Oregon, California, Idaho and Montana).

Description

Red alder is the largest species of alder in North A ...

are limited to disturbed sites and riparian areas. red-cedar grows in the wettest sites. A very small area of the northeastern rain shadow contains the limited Douglas-fir zone, where it is too dry for western hemlock.

thimbleberry

''Rubus parviflorus'', commonly called thimbleberry, (also known as redcaps) is a species of ''Rubus'' native to northern temperate regions of North America. The plant has large hairy leaves and no thorns. It bears edible red fruit similar in a ...

also grow in this zone, often intergrading between the slide alder chutes and the silver fir forest.

The next higher forest zone is the mountain hemlock zone, the highest forest zone in the Olympic mountains. In this zone most precipitation falls as snow and the snow-free growing season is very short. In the drier rainshadow side of the mountains, mountain hemlock is largely replaced by subalpine fir

''Abies lasiocarpa'', the subalpine fir or Rocky Mountain fir, is a western North American fir tree.

Description

''Abies lasiocarpa'' is a medium-sized evergreen conifer with a very narrow conic crown, growing to tall, exceptionally , with a ...

. At the higher elevations of the mountain hemlock/subalpine fir zone, tree cover is reduced to isolated stands of trees called tree islands, surrounded by subalpine meadows, in the subalpine parkland zone. Variations in substrate, topography, moisture, and snowpack depth and duration determine the vegetation community. Tree islands form on convex topography, which tends to gather less snow and shed it sooner than surrounding level or concave topography.

In the west, the subalpine zone is dominated by mountain hemlock

''Tsuga mertensiana'', known as mountain hemlock, is a species of hemlock native to the west coast of North America, found between Southcentral Alaska and south-central California.

Description

''Tsuga mertensiana'' is a large evergreen conifer ...

. It occurs along with subalpine fir

''Abies lasiocarpa'', the subalpine fir or Rocky Mountain fir, is a western North American fir tree.

Description

''Abies lasiocarpa'' is a medium-sized evergreen conifer with a very narrow conic crown, growing to tall, exceptionally , with a ...

from in the Bailey Range; however, the range of this forest type is not extensive and does not extend much west of Mount Olympus, nor is it common in the east. Chamaecyparis nootkatensis, Yellow-cedar is sometimes found in relation to these plants. In the east and other drier areas, the subalpine zone is dominated by subalpine fir. It can occur with other trees, including mountain hemlock, silver fir, and yellow-cedar, but what characterizes these zones is the dominance of subalpine fir. These forests occur on the eastern ridges from .

In the Olympics, the treeline is between and but can be as low as under in some places. Treeline is a function of both elevation and precipitation, particularly the amount of snow that falls each winter. The growing season for trees is relatively short in the higher elevations of the windward Olympics, compared to similar elevations in other mountain ranges, due to the large accumulations of snow that take a long time to melt each year.

Subalpine meadows in the Olympic mountains are of 5 types. Heath shrub meadows are dominated by ericaceous huckleberries and heathers. Lush herbaceous meadows are typified by Sitka valerian and showy sedge. Drier areas or those with longer snow cover grow dwarf sedge (''

Subalpine meadows in the Olympic mountains are of 5 types. Heath shrub meadows are dominated by ericaceous huckleberries and heathers. Lush herbaceous meadows are typified by Sitka valerian and showy sedge. Drier areas or those with longer snow cover grow dwarf sedge (''Carex nigricans

''Carex nigricans'' is a species of sedge known by the common name black alpine sedge.

Distribution

This sedge is native to western North America from Alaska to the Sierra Nevada in California, to Colorado, where it grows in wet areas in mountai ...

'') or grass (''Festuca viridis'') meadows. ''Phlox diffusa

''Phlox diffusa'' is a species of phlox known by the common name spreading phlox. It is native to western North America from British Columbia to the southwestern United States to the Dakotas, where it grows in many types of habitat, including ro ...

'' typifies the low herbaceous meadows of pumice, talus and scree slopes and other rocky areas. American saw-wort is common in both mountain meadows and lower subalpine parklands in the Olympics.

Above timberline is the Alpine zone, not a forest zone since no trees can grow this high. The alpine zone in the Olympics is much more limited in size than in other temperate mountain ranges, from to . The high precipitation of the Olympics creates permanent snow and ice at lower elevations than is typical for other mountain ranges, cutting off the alpine vegetation zone. Most of the alpine vegetation is on the rain shadow side, in the northeastern Olympics, where there is less permanent snow and ice. Alpine vegetation is low herbaceous, typified by ''Phlox diffusa'' and species of ''Carex''. Many of the Olympic Mountain's endemic plants occur here, such as Piper's bellflower (''Campanula piperi'') and Olympic violet ('' Viola flettii'').

Endemic Plants

Flett's fleabane

''Erigeron flettii'' is a rare North American species of flowering plants in the family Asteraceae known by the common names Flett's fleabane or Olympic Mountains fleabane .

''Erigeron flettii'' is endemic to the Olympic Peninsula in the State o ...

(''Erigeron flettii'')

* Thompson's wandering fleabane (''Erigeron peregrinus'' ssp. ''peregrinus'' var. ''thompsonii'')

* Quinault fawn lily (''Erythronium quinaultensis'')

* Olympic rockmat (''Petrophylum hendersonii'')

* Olympic Mountain groundsel (''Senecio neowebsteri'')

* Olympic cut-leaf synthyris (''Synthyris pinnatifida'' var. '' lanuginosa'')

* Olympic Mountain dandelion (''Taraxacum olympicum'')

* Olympic violet (''Viola flettii'')

Fauna

Mammals extirpated from the Olympic Mountains are thefisher

Fisher is an archaic term for a fisherman, revived as gender-neutral.

Fisher, Fishers or The Fisher may also refer to:

Places

Australia

*Division of Fisher, an electoral district in the Australian House of Representatives, in Queensland

*Elect ...

(''Martes pennanti'') and the gray wolf

The wolf (''Canis lupus''; : wolves), also known as the gray wolf or grey wolf, is a large canine native to Eurasia and North America. More than thirty subspecies of ''Canis lupus'' have been recognized, and gray wolves, as popularly ...

(''Canis lupus''). The fisher was declared extirpated from Washington State when no fishers were detected during statewide carnivore surveys in the 1990s and 2000s. A reintroduction project was initiated in 2007, in partnership with Olympic National Park. The gray wolf was extirpated from Washington State in the early 20th century. The last wolf documented in the Olympics was trapped in 1920. In the early 21st century, wolves are naturally migrating back into eastern and north-central Washington State, but there is no evidence of wolf migration into the Olympics and no plan to translocate wolves to the Olympics.

;Carnivores

The gray wolf is listed as endangered by the US Fish and Wildlife Service and the fisher is listed as state endangered by the Washington Fish and Wildlife Commission.

Previous to the extirpation of the gray wolf, coyote

The coyote (''Canis latrans'') is a species of canis, canine native to North America. It is smaller than its close relative, the wolf, and slightly smaller than the closely related eastern wolf and red wolf. It fills much of the same ecologica ...

s (''Canis latrans'') occurred in the lowlands of the Olympic peninsula but not in the mountains. With the absence of wolves, coyotes have been moving up into the higher elevations of the mountains and may be responsible for population declines in the Olympic marmot

The Olympic marmot (''Marmota olympus'') is a rodent in the squirrel family, Sciuridae; it occurs only in the U.S. state of Washington (state), Washington, on the middle elevations of the Olympic Peninsula. The closest relatives of this species ...

.

American black bear

The American black bear (''Ursus americanus''), also called simply a black bear or sometimes a baribal, is a medium-sized bear endemic to North America. It is the continent's smallest and most widely distributed bear species. American black bear ...

(''Ursus americanus'') are numerous in the Olympics. Olympic bears eat salmon, rodents, huckleberries, tree bark, insects, and deer or elk carcasses.

Cougar

The cougar (''Puma concolor'') is a large Felidae, cat native to the Americas. Its Species distribution, range spans from the Canadian Yukon to the southern Andes in South America and is the most widespread of any large wild terrestrial mamm ...

(''Felis concolor'') is the largest carnivore in the Olympics. Their main prey are deer and elk but they also hunt porcupines and insects. They are rarely ''seen'', but are thought to be widespread and relatively common in the Olympics.

;Mountain goats

The mountain goat

The mountain goat (''Oreamnos americanus''), also known as the Rocky Mountain goat, is a hoofed mammal endemic to mountainous areas of western North America. A subalpine to alpine species, it is a sure-footed climber commonly seen on cliffs and ...

(''Oreamnos americanus'') is not native to the Olympic Mountains but was introduced for hunting in the 1920s by a coalition of the Forest Service, the Clallam County Game Warden, and the State Game Commission. Mountain goats in the Olympics have been associated with damage to alpine vegetation and soil erosion.

The goats have also been aggressive towards park visitors. In 1999, a mountain goat gored a hiker at the summit of Mount Ellinor in Olympic National Forest, and in 2010, a mountain goat fatally gored a hiker on the Klahane Ridge trail in Olympic National Park. In 2012, the trail to Mount Ellinor was closed in summer due to aggressive goats, re-opening in the fall.

An airlifting effort by the National Park Service started in September 2018 in an attempt to relocate the goats to the Cascades region. NPS hopes to relocate several hundred goats before starting a lethal removal option. The park service hopes to reduce the goat population to 0-50 animals by 2028.

;Elk

Roosevelt elk

The Roosevelt elk (''Cervus canadensis roosevelti)'', also known commonly as the Olympic elk and Roosevelt's wapiti, is the largest of the four surviving subspecies of elk (''Cervus canadensis'') in North America by body mass (although by antle ...

''Cervus canadensis roosevelti'' range along the Pacific coast from the Russian River to Vancouver Island

Vancouver Island is an island in the northeastern Pacific Ocean and part of the Canadian Provinces and territories of Canada, province of British Columbia. The island is in length, in width at its widest point, and in total area, while are o ...

. Olympic and Vancouver Island elk are some of the last pure Roosevelt elk herds left; those in the Cascades have mixed with Rocky Mountain elk

The Rocky Mountain elk (''Cervus canadensis nelsoni'') is a subspecies of elk found in the Rocky Mountains and adjacent ranges of Western North America.

Habitat

The winter ranges are most common in open forests and floodplain marshes in the lo ...

. Olympic National Park has the largest population of Roosevelt elk in the world. Some herds spend winter in lowland valleys, summer in high country, in subalpine meadows. Other herds live year-round in lowland forests and meadows. Elk prefer more humid areas, the Sitka spruce, wet western hemlock, and mountain hemlock zones.

Elk browsing is believed to be responsible for the open park-like structure of the Olympic rainforests; the elk graze on hemlock and shrubs, leaving the Sitka spruce to grow. Elk browsing also increases diversity of grasses and forbs. Elk exclosure experiments in rainforest valleys show more species of vegetation growing outside the exclosures, where elk browse, than inside; while there are more brush and saplings inside exclosures, there are more grasses and forbs outside. Elk browsing improves forage for other herbivores like deer, voles and snowshoe hares. Elk prefer old growth forest and young alder groves over the large, even-aged plantations common on commercial timber land, although they will use small, recent clearcuts where they mimic natural forest openings.

Both the Press and O’Neil expeditions were impressed by the quantity and tameness of the elk. Both expedition leaders prohibited shooting the elk and deer except when the expedition was in need of meat. The Olympic National Monument was formed to protect the elk after the herds were reduced to less than 2000 animals. The population rebounded, and in 1937 a hunting season for elk was opened in the Hoh River valley.

An estimated 2,000–4,000 hunters came for the 1957 hunting season, several times as many as expected; the excess was a logistical nightmare. One hunter was accidentally shot and died. A second hunter drowned in the Hoh River. A pack horse was shot. The Hoh River flooded, stranding hunters and washing away their camps. Forest Service and State Game personnel were overwhelmed with rescue efforts (lost, stranded, or injured hunters) and dispute resolution. Over 800 elk were killed, some left lying in the forest. Proponents of a national park used the 1937 elk hunt as an argument in favor of permanent protection for Olympic's elk herds. Not all the elk herds are protected inside the national park: Some migrate in and out of the park, and others live entirely outside the park. All elk are subject to regulated hunting when outside the national park.

;Mule deer

Blacktail deer

Two forms of black-tailed deer or blacktail deer that occupy coastal woodlands in the Pacific Northwest of North America are subspecies of the mule deer (''Odocoileus hemionus''). They have sometimes been treated as a species, but virtually all r ...

(''Odocoileus hemionus columbianus'') prefer drier areas than elk, such as the dry western hemlock, Douglas-fir, and subalpine fir zones. Similar to the elk, blacktail deer winter in lowlands, or along south-facing ridges, and summer in the high country meadows.

;Others

Mountain beaver

The mountain beaver (''Aplodontia rufa'')Other names include mountain boomer, ground bear, giant mole, gehalis, lesser sasquatch, sewellel, suwellel, showhurll, showtl, and showte, as well as a number of Chinookan and other Native American terms ...

(''Aplodontia rufa'') is a large primitive rodent endemic to the Pacific Northwest. They are common in the Olympics, preferring wet scrubby thickets and second growth timber.

Banana slug

Banana slugs are North American terrestrial slugs comprising the genus ''Ariolimax''. MolluscaBase eds. (2021). MolluscaBase. Ariolimax Mörch, 1859. Accessed through: World Register of Marine Species at: http://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p= ...

(''Ariolimax columbianus'') is another Pacific Northwest endemic. Slugs are abundant in the Olympic forests, outweighing mammals and birds combined. They thrive in the cool damp shade of the forests. The banana slug is the largest and most conspicuous of Olympic slugs.

Northern spotted owl

The northern spotted owl (''Strix occidentalis caurina'') is one of three spotted owl subspecies. A western North American bird in the family Strigidae, genus ''Strix (genus), Strix'', it is a medium-sized dark brown owl native to the Pacific No ...

(''Strix occidentalis caurina'') is an old-growth dependent species and is listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act. The majority of spotted owls on the Olympic peninsula, along with the largest preserve of temperate old-growth forest, live in the national park. Spotted owls prey on flying squirrels and snowshoe hares, and are themselves preyed on by great horned owl

The great horned owl (''Bubo virginianus''), also known as the tiger owl (originally derived from early naturalists' description as the "winged tiger" or "tiger of the air"), or the hoot owl, is a large owl native to the Americas. It is an extrem ...

s ''Bubo virginianus''. The density of the canopy of an old-growth forest gives the spotted owls some protection from the larger, less agile great horned owls.

Rufous hummingbird

The rufous hummingbird (''Selasphorus rufus'') is a small hummingbird, about long with a long, straight and slender bill. These birds are known for their extraordinary flight skills, flying during their migratory transits. It is one of nine sp ...

(''Selasphorus rufus'') is the only hummingbird in the Olympics. They overwinter in Mexico and southern California, arriving in the Olympics in February or March with the flowering of the Indian plum ''Oemleria cerasifera''.

Harlequin duck

The harlequin duck (''Histrionicus histrionicus'') is a small sea duck. It takes its name from Harlequin (French ''Arlequin'', Italian ''Arlecchino''), a colourfully dressed character in Commedia dell'arte. The species name comes from the Latin ...

(''Histrionicus histrionicus'') breeds in fast-moving mountain streams in the Olympics. They spend the rest of the year in coastal waters.

Osprey

The osprey (''Pandion haliaetus''), , also called sea hawk, river hawk, and fish hawk, is a diurnal, fish-eating bird of prey with a cosmopolitan range. It is a large raptor reaching more than in length and across the wings. It is brown o ...

(''Pandion haliaetus'') and bald eagle

The bald eagle (''Haliaeetus leucocephalus'') is a bird of prey found in North America. A sea eagle, it has two known subspecies and forms a species pair with the white-tailed eagle (''Haliaeetus albicilla''), which occupies the same niche as ...

(''Haliaeetus leucocephalus'') fish in Olympic rivers, nesting in large old trees. Both are relatively common, the bald eagle more so along the coast than in the mountains.

Olympic rivers are dominated by Pacific salmonids

Salmonidae is a family of ray-finned fish that constitutes the only currently extant family in the order Salmoniformes . It includes salmon (both Atlantic and Pacific species), trout (both ocean-going and landlocked), chars, freshwater whitefi ...

, the ''Oncorhynchus

''Oncorhynchus'' is a genus of fish in the family Salmonidae; it contains the Pacific salmon and Pacific trout. The name of the genus is derived from the Greek ὄγκος (ónkos, “lump, bend”) + ῥύγχος (rhúnkhos, “snout”), in r ...

''. Chinook, coho, pink, rainbow and steelhead, and cutthroat all spawn in Olympic rivers. Chum and sockeye also live in coastal Olympic peninsula rivers but do not reach into the mountains. Bull trout

The bull trout (''Salvelinus confluentus'') is a char of the family Salmonidae native to northwestern North America. Historically, ''S. confluentus'' has been known as the " Dolly Varden" (''S. malma''), but was reclassified as a separate specie ...

(''Salvelinus confluentus'') and Dolly Varden trout

The Dolly Varden trout (''Salvelinus malma'') is a species of salmonid fish native to cold-water tributaries of the Pacific Ocean in Asia and North America. It belongs to the genus ''Salvelinus'', or true chars, which includes 51 recognized spec ...

(''S. malma'') also live in Olympic rivers.

Endemic fauna

There are at least 16endemic

Endemism is the state of a species being found in a single defined geographic location, such as an island, state, nation, country or other defined zone; organisms that are indigenous to a place are not endemic to it if they are also found elsew ...

animal species.

;Mammals

*Olympic marmot

The Olympic marmot (''Marmota olympus'') is a rodent in the squirrel family, Sciuridae; it occurs only in the U.S. state of Washington (state), Washington, on the middle elevations of the Olympic Peninsula. The closest relatives of this species ...

(''Marmota olympus'')

* Olympic chipmunk (''Tamius amoenus caurinus'')

* Olympic snow mole (''Scapanus townsendii olympicus'')

*Mazama pocket gopher

The Mazama pocket gopher (''Thomomys mazama'') is a smooth-toothed pocket gopher restricted to the Pacific Northwest. The herbivorous species ranges from coastal Washington, through Oregon, and into north-central California. Four subspecies of th ...

(''Thomomys mazama melanops'')

*Olympic ermine

Olympic or Olympics may refer to

Sports

Competitions

* Olympic Games, international multi-sport event held since 1896

** Summer Olympic Games

** Winter Olympic Games

* Ancient Olympic Games, ancient multi-sport event held in Olympia, Greece bet ...

(''Mustela richardsonii olympica'')

;Amphibians

*Olympic torrent salamander

The Olympic torrent salamander (''Rhyacotriton olympicus'') is a species of salamander in the family Rhyacotritonidae. This is a small salamander (up to 10 cm total length) that lives in clear, cold, mountain streams. It is medium to dark br ...

(''Rhyacotriton olympicus'')

;Fish

*Olympic mudminnow

The Olympic mudminnow (''Novumbra hubbsi'') is a fish native to the western lowlands of Washington: the Chehalis River basin, Deschutes River basin, and some Olympic Peninsula basins. It grows to 8 cm (about 3 in) in length, and is Was ...

(''Novumbra hubbsi'')

* Beardslee rainbow trout (''Oncorhynchus mykiss irideus'')

*Crescenti cutthroat trout

The Crescenti cutthroat trout or the Lake Crescent cutthroat trout is a North American freshwater fish, a local form (zoology), form (f. loc.) of the coastal cutthroat trout (''Oncorhynchus clarkii clarkii'') isolated in Lake Crescent in Washingt ...

(''Oncorhynchus clarki clarki'')

;Insects

* Hulbert's skipper butterfly (''Hesperia comma hulbirti'')

* Olympic grasshopper (''Nisquallia olympica'')

* Mann's gazelle beetle (''Nebria dammanni'')

*Quileute gazelle beetle

The Quileute , are a Native American people in western Washington state in the United States, currently numbering approximately 2,000. They are a federally recognized tribe: the ''Quileute Tribe of the Quileute Reservation''.

The Quileute peop ...

(''Nebria acuta quileute'')

*Tiger beetle

Tiger beetles are a family of beetles, Cicindelidae, known for their aggressive predatory habits and running speed. The fastest known species of tiger beetle, ''Rivacindela hudsoni'', can run at a speed of , or about 125 body lengths per second. ...

(''Cicindela bellissima frechini'')

;Molluscs

*Arionid slug

Arionidae, common name the "roundback slugs" or "round back slugs" are a taxonomic family of air-breathing land slugs, terrestrial pulmonate gastropod mollusks in the superfamily Arionoidea.

Distribution

The distribution of this family of slu ...

(''Hemphillia dromedarius'')

*Arionid jumping slug

Arionidae, common name the "roundback slugs" or "round back slugs" are a taxonomic family of air-breathing land slugs, terrestrial pulmonate gastropod mollusks in the superfamily Arionoidea.

Distribution

The distribution of this family of slu ...

(''Hemphillia burringtoni'')

;Near-endemic

Near-endemics, those that occur in the Olympics as well as other parts of a limited range, include the Cope's giant salamander

Cope's giant salamander (''Dicamptodon copei'') is a species of salamander in the family Dicamptodontidae, the Pacific giant salamanders.Behler, J. L. and F. W. King. (1979) ''National Audubon Society Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians'', Kno ...

(''Dicamptodon copei''), and the Van Dyke's salamander (''Plethodon vandykei'',) both found primarily in the Olympics and other mountainous areas of western Washington; the tailed frog

The tailed frogs are two species of frogs in the genus ''Ascaphus'', the only taxon in the family Ascaphidae . The "tail" in the name is actually an extension of the male cloaca. The tail is one of two distinctive anatomical features adapting the ...

(''Ascaphus truei''), of Pacific Northwest mountain streams, and the mountain beaver

The mountain beaver (''Aplodontia rufa'')Other names include mountain boomer, ground bear, giant mole, gehalis, lesser sasquatch, sewellel, suwellel, showhurll, showtl, and showte, as well as a number of Chinookan and other Native American terms ...

(''Aplodontia rufa'') of the coastal Pacific Northwest.

History

Prehistory

For the original inhabitants of the Olympic Peninsula, the highest peaks of the mountains were the only refuges during the Great Floods at the beginning of time. For the Elwha Klallam people, that peak was Mount Carrie; for the Skokomish, it was a peak west of Mount Ellinor. TheThunderbird

Thunderbird, thunder bird or thunderbirds may refer to:

* Thunderbird (mythology), a legendary creature in certain North American indigenous peoples' history and culture

* Ford Thunderbird, a car

Birds

* Dromornithidae, extinct flightless birds k ...

figure of the Hoh tribe lived on Mount Olympus, in a den under Blue Glacier. People in the Skokomish, Quinault, and Elwha watersheds regularly traveled into the high country to hunt elk, gather huckleberries and beargrass, and perform spirit quests. Trails across the mountains allowed members of the various tribes to visit and trade with each other. The cross-Olympic expeditions of the 1890s found tree blazes that they took to mark Indian trails.

Archeological evidence shows that the Olympic Mountains were inhabited by Paleolithic

The Paleolithic or Palaeolithic (), also called the Old Stone Age (from Greek: παλαιός ''palaios'', "old" and λίθος ''lithos'', "stone"), is a period in human prehistory that is distinguished by the original development of stone too ...

hunters after the retreat of the Cordilleran Ice Sheet. Stone tools in the Deer Park area date to 7600 years ago, prior to the volcanic eruption of Mount Mazama

Mount Mazama (''Giiwas'' in the Native American language Klamath language, Klamath) is a complex volcano in the state of Oregon, United States, in a segment of the Cascade Volcanoes, Cascade Volcanic Arc and Cascade Range. Most of the mountai ...

. Similar tools have been found near Lake Cushman and throughout the Olympic subalpine meadows and ridges, as well as in coastal areas. In addition, a fragment of a woven basket found in the Olympic subalpine of Obstruction Point was radiocarbon dated

Radiocarbon dating (also referred to as carbon dating or carbon-14 dating) is a method for determining the age of an object containing organic material by using the properties of radiocarbon, a radioactive isotope of carbon.

The method was dev ...

to nearly 3000 years ago.

The mountains were originally called "Sun-a-do" by the Duwamish Indians, while the first European to see them, the Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many Latin American countries

**Spanish cuisine

Other places

* Spanish, Ontario, Cana ...

navigator Juan Pérez, named Mount Olympus "Santa Rosalia", in 1774. But the English captain John Meares

John Meares (c. 1756 – 1809) was an English navigator, explorer, and maritime fur trader, best known for his role in the Nootka Crisis, which brought Britain and Spain to the brink of war.

Career

Meares' father was Charles Meares, "formerly an ...

, seeing them in 1788, thought he would honor the Greek explorer Juan de Fuca

Juan de Fuca (10 June 1536, Cefalonia 23 July 1602, Cefalonia)Greek Consulate of Vancouver,Greek Pioneers: Juan de Fuca. was a Greeks, Greek maritime pilot, pilot who served Philip II of Spain, PhilipII of Spanish Empire, Spain. He is best know ...

who claimed to have found the fabled Northwest passage nearby by naming the mountain after the mythical home of Greek Gods which is "Mount Olympus

Mount Olympus (; el, Όλυμπος, Ólympos, also , ) is the highest mountain in Greece. It is part of the Olympus massif near the Thermaic Gulf of the Aegean Sea, located in the Olympus Range on the border between Thessaly and Macedonia, be ...

" in Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders with ...

. Various names for the mountains were used based on the name Mount Olympus, including the Olympic Range, the Olympian Mountains, and the Olympus Range. Alternate proposals never caught on, and in 1864 the Seattle

Seattle ( ) is a seaport city on the West Coast of the United States. It is the seat of King County, Washington. With a 2020 population of 737,015, it is the largest city in both the state of Washington and the Pacific Northwest regio ...

''Weekly Gazette'' persuaded the government to make the present-day name official, although other names continued to be used.

First O'Neil Expedition, 1885

Though readily visible from many parts of western Washington, especially Seattle, the interior was almost entirely unexplored until 1885, when 2nd Lt.Joseph P. O'Neil

Joseph Patrick O'Neil (December 27, 1863 – July 27, 1938) was a United States Army officer in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. He served in several conflicts, including World War I.

Biography

Joseph O'Neil was born in Brooklyn, New York, ...

of the 14th Infantry, stationed at Fort Vancouver

Fort Vancouver was a 19th century fur trading post that was the headquarters of the Hudson's Bay Company's Columbia Department, located in the Pacific Northwest. Named for Captain George Vancouver, the fort was located on the northern bank of the ...

, led a small expedition into the northern Olympics from Port Angeles

Port Angeles ( ) is a city and county seat of Clallam County, Washington, United States. With a population of 19,960 as of the 2020 census, it is the largest city in the county. The population was estimated at 20,134 in 2021.

The city's har ...

. O’Neil led an expedition of 3 enlisted men, 2 civilian engineers, and 8 mule

The mule is a domestic equine hybrid between a donkey and a horse. It is the offspring of a male donkey (a jack) and a female horse (a mare). The horse and the donkey are different species, with different numbers of chromosomes; of the two pos ...

s out of Port Angeles in July 1885. The expedition cut a mule trail from Port Angeles up to Hurricane Ridge and camped near the current site of the national park visitor center. From there, they explored and built trail to the east and south, exploring the upper Dungeness and Dosewallips River watersheds, and to Cameron Basin near Mount Cameron. O’Neil was recalled by the Army in August to be transferred to Fort Leavenworth

Fort Leavenworth () is a United States Army installation located in Leavenworth County, Kansas, in the city of Leavenworth, Kansas, Leavenworth. Built in 1827, it is the second oldest active United States Army post west of Washington, D.C., an ...

in Kansas, and the expedition had to return to Fort Townsend. The Obstruction Peak Road and portions of the Hurricane Ridge Road and the Klahane Ridge, Grand Pass and Lost Pass trails in Olympic National Park originated with the mule trails built by this expedition.

In late 1889, Charles A. Gilman and his son Samuel explored the East Fork Quinault up to its headwaters, but chose to return the way they came rather than cross over the mountains.

Press Expedition 1889–1890

The first crossing of the Olympic Mountains was done from November 1889 through May 1890 by the Press Expedition, a group of 5 men led by Canadian James H. Christie, sponsored by the Seattle newspaper ''Press'', which ascended the Elwha River and descended the North Fork Quinault River. The Press party included 2 mules, which both died in separate incidents, and 4 dogs, 1 of which was killed by an elk. The Press Expedition crossed in winter, in order to beat O'Neil's planned expedition for the summer of 1890. Initially the expedition built a boat on the Elwha to tow their cargo upriver, but the icy water and deep snow covering boulders and fallen trees made this mode of transportation very slow – after 2 weeks, the men had towed the boat . It did, however, carry cargo where the mules could not. Christie and his men abandoned the boat and switched to the mules when they reached the head of navigation on the Elwha, but the mules both died in separate incidents fairly early in the expedition. Deep snow, steep slopes, and fallen trees made travel extremely difficult for the mules, along with lack of forage. The expedition carried minimal food, expecting to find game. In the lowlands, game and fish were plentiful, but the heavy snow that winter drove game out of the mountains and for long stretches in the high mountains, the men were reduced to eating ‘flour soup’. Unlike O’Neil's military expeditions, the Press Expedition had no resupply line. Once into the high mountains and the deep snow, with no game, they went weeks with no meat and little to eat besides flour and beans. The men carried all the cargo on their own backs through one of the roughest and most labyrinthine sections of the high mountains, through snow deep. On climbing a peak to get a view of the area, Christie estimated the snow at the peak to be deep. Avalanches occurred on a daily basis. Crossing Low Divide between the upper Elwha and the headwaters of the North Fork Quinault, the men climbed a vertical cliff, requiring Christie to climb to a ledge and then lower a rope to the men below. Packs, dogs, and men were hauled up the cliff by rope. Once on the Quinault side of the divide, the men shot and ate a bear, the first meat they had had for several weeks of strenuous winter mountain travel. Deep snow prevented proper trail building for much of their route, although they did cut a rough trail along the lower reach of the Elwha River, and blazed trees along their route. They used elk trails wherever possible, and walked in the river when there was no other way through due to steep terrain or dense brush. It took the expedition four months of slogging through dense brush andwindthrow

In forestry, windthrow refers to trees uprooted by wind. Breakage of the tree bole (trunk) instead of uprooting is called windsnap. Blowdown refers to both windthrow and windsnap.

Causes

Windthrow is common in all forested parts of the w ...

s, swamps, steep canyons and deep, wet, slushy snow just to reach the inner mountains. Once in the high mountains, the relief was so precipitous that the men estimated they traveled up and down as much as to cover horizontal miles.

Once on the mainstem Quinault River, the men built a raft, but it wrecked on a logjam. The men saved the dogs and the one pack that contained their maps, photographs, and records made along the route, but lost all their food, armaments, utensils, fishing tackle, shelter, and the few mineral and plant specimens and animal skins they had collected; and the men were split on opposite sides of the river, unable to reach each other. They continued walking down the river, eating salmonberry

''Rubus spectabilis'', the salmonberry, is a species of bramble in the rose family Rosaceae, native to the west coast of North America from west-central Alaska to California, inland as far as Idaho. Like many other species in the genus ''Rubus'' ...

shoots and spruce bark, until a settler and a Quinault Indian guide canoeing to Lake Quinault rescued them. When the O’Neil expedition of 1890 reached the mainstem Quinault River a few months later, they found some of the items the Press Expedition had lost in the wreck. The settler and neighboring Indians took the expedition across Lake Quinault and down the lower river to the coast in mid May, nearly six months after they left Port Angeles. From the mouth of the Quinault they traveled to Aberdeen

Aberdeen (; sco, Aiberdeen ; gd, Obar Dheathain ; la, Aberdonia) is a city in North East Scotland, and is the third most populous city in the country. Aberdeen is one of Scotland's 32 local government council areas (as Aberdeen City), and ...

and then to Seattle. Their account of their expedition, along with photographs and a full-page map, was printed in a special edition of the ''Press'' on 16 July 1890.

The Elwha River and North Fork Quinault trails in Olympic National Park follow the route of the Press Expedition, with a detour through the highest mountains and around the vertical cliff at Low Divide.

Second O'Neil Expedition, 1890

O'Neil returned to Washington in 1887 and started planning another expedition. The Olympic Exploring Expedition, led by O’Neil, crossed the southern Olympics in the summer of 1890, ascending the North Fork Skokomish River and descending the East Fork Quinault River, building a mule trail the entire distance. This expedition was larger than the 1885 expedition, and would be resupplied by mule train from Hoodsport on Hood Canal, allowing time for scientific exploration of the area. The expedition consisted of 10 soldiers, 1 civilian mule packer, 4 civilian scientists from the Oregon Alpine Club, 11 mules, 1 bellmare

A mare is an adult female horse or other equine. In most cases, a mare is a female horse over the age of three, and a filly is a female horse three and younger. In Thoroughbred horse racing, a mare is defined as a female horse more than four ...

to lead the mule train, and up to 4 dogs. The scientists collected specimens of plants, animals, and minerals, which they shipped back to Portland

Portland most commonly refers to:

* Portland, Oregon, the largest city in the state of Oregon, in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States

* Portland, Maine, the largest city in the state of Maine, in the New England region of the northeas ...

by way of the mule train to Hoodsport. The majority of the party was assigned to cutting the mule trail, while 2 or 3 man exploring parties fanned out and scouts went ahead. The scouts and side exploring parties scrambled up slopes on all fours, pulling themselves up by grabbing onto vegetation; descended similar slopes by sliding, deliberately or inadvertently; hacked and crawled through dense brush and windthrow; waded up rivers and streams when there was no other way through; felled trees to bridge ravines and rivers; and traversed narrow ridges of crumbling vertically oriented shale. Hornet

Hornets (insects in the genus ''Vespa'') are the largest of the eusocial wasps, and are similar in appearance to their close relatives yellowjackets. Some species can reach up to in length. They are distinguished from other vespine wasps by th ...

and yellow jacket

Yellowjacket or yellowjacket is the common name in North America for predatory social wasps of the genera ''Vespula'' and ''Dolichovespula''. Members of these genera are known simply as "wasps" in other English-speaking countries. Most of these ...

wasp attacks were a daily occurrence, sending men scrambling and mules stampeding, one over a cliff to her death. Where the men crossed swamps, devils club thorns impaled the men and broke off in their skin, creating painful inflammations.

Once camped in the central mountains, O’Neil sent out small exploring parties to the Duckabush, Dosewallips, South Fork Skokomish, Wynoochee and Humptulips rivers, and to Mount Olympus and the Queets River. One party of 3 men climbed what they thought was Mount Olympus but was in reality one of the neighboring peaks, Athena II. A fourth member of the summit party became separated on the climb and ended up descending the Queets River alone, and was taken in by a Quinault Indian family. They were reluctant to believe that he had crossed the Olympics, not believing it was possible to do so; but they accepted his story when he was able to point out reference points on a map. (Many members of this expedition spoke Chinook jargon.) From their settlement, he was able to rejoin the expedition in Hoquiam

Hoquiam ( ) is a city in Grays Harbor County, Washington, United States. It borders the city of Aberdeen at Myrtle Street, with Hoquiam to the west. The two cities share a common economic history in lumbering and exporting, but Hoquiam has mainta ...

. O'Neil's reports on his explorations resulted in his recommendation that the region be declared a national park.

20th century

Mount Olympus itself was not ascended until 1907, one of the first successes of The Mountaineers, which had been organized in Seattle just a few years earlier. A number of the more obscure and least-accessible peaks in the range were not ascended until the 1970s. PresidentGrover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 22nd and 24th president of the United States from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. Cleveland is the only president in American ...

protected the forests of the Olympic Peninsula with the Olympic Forest Reserve in 1897. Initially the reserve consisted of over 2 million acres, nearly the entire peninsula. Forest Service surveyors Dodwell and Rixon spent three years surveying, timber cruising, and mapping the new reserve. Their report, published in 1902, reported that most of the land was not suited to agriculture, but local politicians had already convinced President William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until his assassination in 1901. As a politician he led a realignment that made his Republican Party largely dominant in ...

to remove the most valuable lowland timber from the reserve, claiming it should be open to homesteading. Private timber companies paid ‘homesteaders’ to file claims on land that they then sold to the timber company. At the same time, commercial hunters reduced the Olympic elk herds to fewer than 2000 animals, prompting the state legislature to impose a temporary moratorium on elk hunting in the Olympics. The Forest Reserve was reorganized under Gifford Pinchot

Gifford Pinchot (August 11, 1865October 4, 1946) was an American forester and politician. He served as the fourth chief of the U.S. Division of Forestry, as the first head of the United States Forest Service, and as the 28th governor of Pennsy ...

as the Olympic National Forest in 1905, with an emphasis on commercial utilization of timber and minerals and fire protection, as well as hunting and trapping. With the passing of the Antiquities Act

The Antiquities Act of 1906 (, , ), is an act that was passed by the United States Congress and signed into law by Theodore Roosevelt on June 8, 1906. This law gives the President of the United States the authority to, by presidential procla ...

in 1906, which allowed the president to designate national monuments, Mount Olympus National Monument, administered by the Forest Service, was proclaimed by Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

in 1909 in order to protect the elk herds. In 1914, the new supervisor of the Forest Service, Henry Graves, made a trip to the Olympics to determine if commercial timber and minerals were being tied up in the national monument. As a result of Grave's report, President Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

removed a third of a million acres from the monument.

The Elwha River was dammed in 1910 with construction of the Elwha Dam. A second dam was built a few miles upstream in 1927. Neither dam had any fish passage for the salmonid runs, eliminating salmonids from over 70 miles of river. Congress authorized removal of these dams in 1992, and work began in 2011.

The North Fork Skokomish River was dammed in the 1920s by the city of Tacoma, enlarging the original Lake Cushman by 600%. A settlement was reached in 2009 with the Skokomish Indian Tribe

The Skokomish Indian Tribe, formerly known as the Skokomish Indian Tribe of the Skokomish Reservation, and in its own official use the Skokomish Tribal Nation, is a federally recognized tribe of Skokomish, Twana, Klallam, and Chimakum people. T ...

over damages to fisheries and game habitat, damages to tribal lands through flooding, and trespass on tribal lands for the power transmission line. As part of the settlement, migrating salmon will be trucked around the dam.

The Wynoochee River was dammed in the late 1960s by the Army Corps of Engineers for flood control, but in 1994 the dam was taken over by the city of Tacoma for power generation. Migrating salmon are trucked around the dam, and Tacoma Public Utilities funds mitigation for Roosevelt elk wintering habitat that was lost under the reservoir.