Old Chinese Phonology on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Scholars have attempted to reconstruct the

Although the Chinese writing system is not alphabetic, comparison of words whose characters share a phonetic element (a phonetic series) yields much information about pronunciation.

Often the characters in a phonetic series are still pronounced alike, as in the character (''zhЕҚng'', 'middle'), which was adapted to write the words ''chЕҚng'' ('pour', ) and ''zhЕҚng'' ('loyal', ).

In other cases the words in a phonetic series have very different sounds in any known variety of Chinese, but are assumed to have been similar at the time the characters were chosen.

A key principle, first proposed by the Swedish sinologist Bernhard Karlgren, holds that the initials of words written with the same phonetic component had a common point of articulation in Old Chinese.

For example, since Middle Chinese dentals and retroflex stops occur together in phonetic series, they are traced to a single Old Chinese dental series, with the retroflex stops conditioned by an Old Chinese medial .

The Middle Chinese dental sibilants and retroflex sibilants also occur interchangeably in phonetic series, and are similarly traced to a single Old Chinese sibilant series, with the retroflex sibilants conditioned by the Old Chinese medial .

However, there are several cases where quite different Middle Chinese initials appear together in a phonetic series.

Karlgren and subsequent workers have proposed either additional Old Chinese consonants or initial consonant clusters in such cases.

For example, the Middle Chinese palatal sibilants appear in two distinct kinds of series, with dentals and with velars:

* ''tЕӣjЙҷu'' (< ) 'cycle; Zhou dynasty', ''tieu'' (< ) 'carve' and ''dieu'' (< ) 'adjust'

* ''tЕӣjГӨi-'' (< ) 'cut out' and ''kjГӨi-'' (< ) 'mad dog'

It is believed that the palatals arose from dentals and velars followed by an Old Chinese medial , unless the medial was also present.

While all such dentals were palatalized, the conditions for palatalization of velars are only partly understood (see Medials below).

Similarly, it is proposed that the medial could occur after labials and velars, complementing the instances proposed as sources of Middle Chinese retroflex dentals and sibilants, to account for such connections as:

* ''pjet'' (< ) 'writing pencil' and ''ljwet'' (< ) 'law; rule'

* ''kam'' (< ) 'look at' and ''lГўm'' (< ) 'indigo'

Thus the Middle Chinese lateral ''l-'' is believed to reflect Old Chinese .

Old Chinese voiced and voiceless laterals and are proposed to account for a different group of series such as

* ''dwГўt'' (< ) and ''thwГўt'' (< ) 'peel off', ''jwГӨt'' (< ) 'pleased' and ''ЕӣjwГӨt'' (< OC ) 'speak'

This treatment of the Old Chinese liquids is further supported by Tibeto-Burman cognates and by transcription evidence.

For example, the name of a city (

Although the Chinese writing system is not alphabetic, comparison of words whose characters share a phonetic element (a phonetic series) yields much information about pronunciation.

Often the characters in a phonetic series are still pronounced alike, as in the character (''zhЕҚng'', 'middle'), which was adapted to write the words ''chЕҚng'' ('pour', ) and ''zhЕҚng'' ('loyal', ).

In other cases the words in a phonetic series have very different sounds in any known variety of Chinese, but are assumed to have been similar at the time the characters were chosen.

A key principle, first proposed by the Swedish sinologist Bernhard Karlgren, holds that the initials of words written with the same phonetic component had a common point of articulation in Old Chinese.

For example, since Middle Chinese dentals and retroflex stops occur together in phonetic series, they are traced to a single Old Chinese dental series, with the retroflex stops conditioned by an Old Chinese medial .

The Middle Chinese dental sibilants and retroflex sibilants also occur interchangeably in phonetic series, and are similarly traced to a single Old Chinese sibilant series, with the retroflex sibilants conditioned by the Old Chinese medial .

However, there are several cases where quite different Middle Chinese initials appear together in a phonetic series.

Karlgren and subsequent workers have proposed either additional Old Chinese consonants or initial consonant clusters in such cases.

For example, the Middle Chinese palatal sibilants appear in two distinct kinds of series, with dentals and with velars:

* ''tЕӣjЙҷu'' (< ) 'cycle; Zhou dynasty', ''tieu'' (< ) 'carve' and ''dieu'' (< ) 'adjust'

* ''tЕӣjГӨi-'' (< ) 'cut out' and ''kjГӨi-'' (< ) 'mad dog'

It is believed that the palatals arose from dentals and velars followed by an Old Chinese medial , unless the medial was also present.

While all such dentals were palatalized, the conditions for palatalization of velars are only partly understood (see Medials below).

Similarly, it is proposed that the medial could occur after labials and velars, complementing the instances proposed as sources of Middle Chinese retroflex dentals and sibilants, to account for such connections as:

* ''pjet'' (< ) 'writing pencil' and ''ljwet'' (< ) 'law; rule'

* ''kam'' (< ) 'look at' and ''lГўm'' (< ) 'indigo'

Thus the Middle Chinese lateral ''l-'' is believed to reflect Old Chinese .

Old Chinese voiced and voiceless laterals and are proposed to account for a different group of series such as

* ''dwГўt'' (< ) and ''thwГўt'' (< ) 'peel off', ''jwГӨt'' (< ) 'pleased' and ''ЕӣjwГӨt'' (< OC ) 'speak'

This treatment of the Old Chinese liquids is further supported by Tibeto-Burman cognates and by transcription evidence.

For example, the name of a city (

A reconstruction of Old Chinese finals must explain the rhyming practice of the ''

A reconstruction of Old Chinese finals must explain the rhyming practice of the ''

English translation

by Marc Brunelle) *

English translation

by Guillaume Jacques) * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * Reprinted by ''ShДҒngwГ№ YГ¬nshЕ«guЗҺn ChЕ«bЗҺn'', Beijing in 2008, . * *

"Introduction to Chinese Historical Phonology"

Guillaume Jacques, European Association of Chinese Linguistics Spring School in Chinese Linguistics, International Institute for Asian Studies, Leiden, March 2006.

"Summer School on Old Chinese Phonology"

(videos), William Baxter and Laurent Sagart, Гүcole des Hautes Гүtudes en Sciences Sociales, Paris, July 2007. Databases of reconstructions

StarLing database

by Georgiy Starostin.

The Baxter-Sagart reconstruction of Old Chinese

дёҠеҸӨйҹізі»- йҹ»е…ёз¶І

е°Ҹеӯёе ӮдёҠеҸӨйҹі - дёӯеӨ®з ”究йҷў

жқҺж–№жЎӮдёҠеҸӨйҹійҹ»иЎЁ

{{DEFAULTSORT:Old Chinese Phonology

phonology

Phonology is the branch of linguistics that studies how languages or dialects systematically organize their sounds or, for sign languages, their constituent parts of signs. The term can also refer specifically to the sound or sign system of a ...

of Old Chinese

Old Chinese, also called Archaic Chinese in older works, is the oldest attested stage of Chinese, and the ancestor of all modern varieties of Chinese. The earliest examples of Chinese are divinatory inscriptions on oracle bones from around 12 ...

from documentary evidence. Although the writing system does not describe sounds directly, shared phonetic components of the most ancient Chinese characters

Chinese characters () are logograms developed for the writing of Chinese. In addition, they have been adapted to write other East Asian languages, and remain a key component of the Japanese writing system where they are known as '' kan ...

are believed to link words that were pronounced similarly at that time. The oldest surviving Chinese verse, in the ''Classic of Poetry

The ''Classic of Poetry'', also ''Shijing'' or ''Shih-ching'', translated variously as the ''Book of Songs'', ''Book of Odes'', or simply known as the ''Odes'' or ''Poetry'' (; ''ShД«''), is the oldest existing collection of Chinese poetry, co ...

'' (''Shijing''), shows which words rhymed in that period. Scholars have compared these bodies of contemporary evidence with the much later Middle Chinese reading pronunciations listed in the ''Qieyun

The ''Qieyun'' () is a Chinese language, Chinese rhyme dictionary, published in 601 during the Sui dynasty. The book was a guide to proper reading of classical texts, using the ''fanqie'' method to indicate the pronunciation of Chinese characters ...

'' rime dictionary published in 601 AD, though this falls short of a phonemic analysis. Supplementary evidence has been drawn from cognates in other Sino-Tibetan languages

Sino-Tibetan, also cited as Trans-Himalayan in a few sources, is a family of more than 400 languages, second only to Indo-European in number of native speakers. The vast majority of these are the 1.3 billion native speakers of Chinese languages. ...

and in Min Chinese

Min (; BUC: ''Mìng-ngṳ̄'') is a broad group of Sinitic languages spoken by about 30 million people in Fujian province as well as by the descendants of Min speaking colonists on Leizhou peninsula and Hainan, or assimilated natives of Chaosh ...

, which split off before the Middle Chinese period, Chinese transcriptions of foreign names, and early borrowings from and by neighbouring languages such as HmongвҖ“Mien, Tai and Tocharian languages

The Tocharian (sometimes ''Tokharian'') languages ( or ), also known as ''ArЕӣi-KuДҚi'', Agnean-Kuchean or Kuchean-Agnean, are an extinct branch of the Indo-European language family spoken by inhabitants of the Tarim Basin, the Tocharians. The ...

.

Although many details are disputed, most recent reconstructions agree on the basic structure. It is generally agreed that Old Chinese differed from Middle Chinese in lacking retroflex and palatal obstruent

An obstruent () is a speech sound such as , , or that is formed by ''obstructing'' airflow. Obstruents contrast with sonorants, which have no such obstruction and so resonate. All obstruents are consonants, but sonorants include vowels as well a ...

s but having initial consonant clusters of some sort, and in having voiceless sonorant

In phonetics and phonology, a sonorant or resonant is a speech sound that is produced with continuous, non-turbulent airflow in the vocal tract; these are the manners of articulation that are most often voiced in the world's languages. Vowels ar ...

s. Most recent reconstructions also posit consonant clusters at the end of the syllable, developing into tone distinctions in Middle Chinese.

Syllable structure

Although many details are still disputed, recent formulations are in substantial agreement on the core issues. For example, the Old Chinese initial consonants recognized by Li Fang-Kuei and William Baxter are given below, with Baxter's (mostly tentative) additions given in parentheses: Most scholars reconstruct clusters of with other consonants, and possibly other clusters as well, but this area remains unsettled. In recent reconstructions, such as the widely accepted system of , the rest of the Old Chinese syllable consists of * an optional medial , * an optional medial or (in some reconstructions) some other representation of a distinction between "type-A" and "type-B" syllables, * one of sixvowel

A vowel is a syllabic speech sound pronounced without any stricture in the vocal tract. Vowels are one of the two principal classes of speech sounds, the other being the consonant. Vowels vary in quality, in loudness and also in quantity (l ...

s:

* an optional coda, which could be a glide or , a nasal , or , or a stop , , or ,

* an optional post-coda or .

In such systems, Old Chinese has no tones; the rising and departing tones of Middle Chinese are treated as reflexes of the Old Chinese post-codas.

Initials

The primary sources of evidence for the reconstruction of the Old Chinese initials are medieval rhyme dictionaries and phonetic clues in the Chinese script.Middle Chinese initials

The reconstruction of Old Chinese often starts from "Early Middle Chinese", the phonological system of the ''Qieyun

The ''Qieyun'' () is a Chinese language, Chinese rhyme dictionary, published in 601 during the Sui dynasty. The book was a guide to proper reading of classical texts, using the ''fanqie'' method to indicate the pronunciation of Chinese characters ...

'', a rhyme dictionary published in 601, with many revisions and expansions over the following centuries.

According to its preface, the ''Qieyun'' did not record a single contemporary dialect, but set out to codify the pronunciations of characters to be used when reading the classics, incorporating distinctions made in different parts of China at the time (a diasystem).

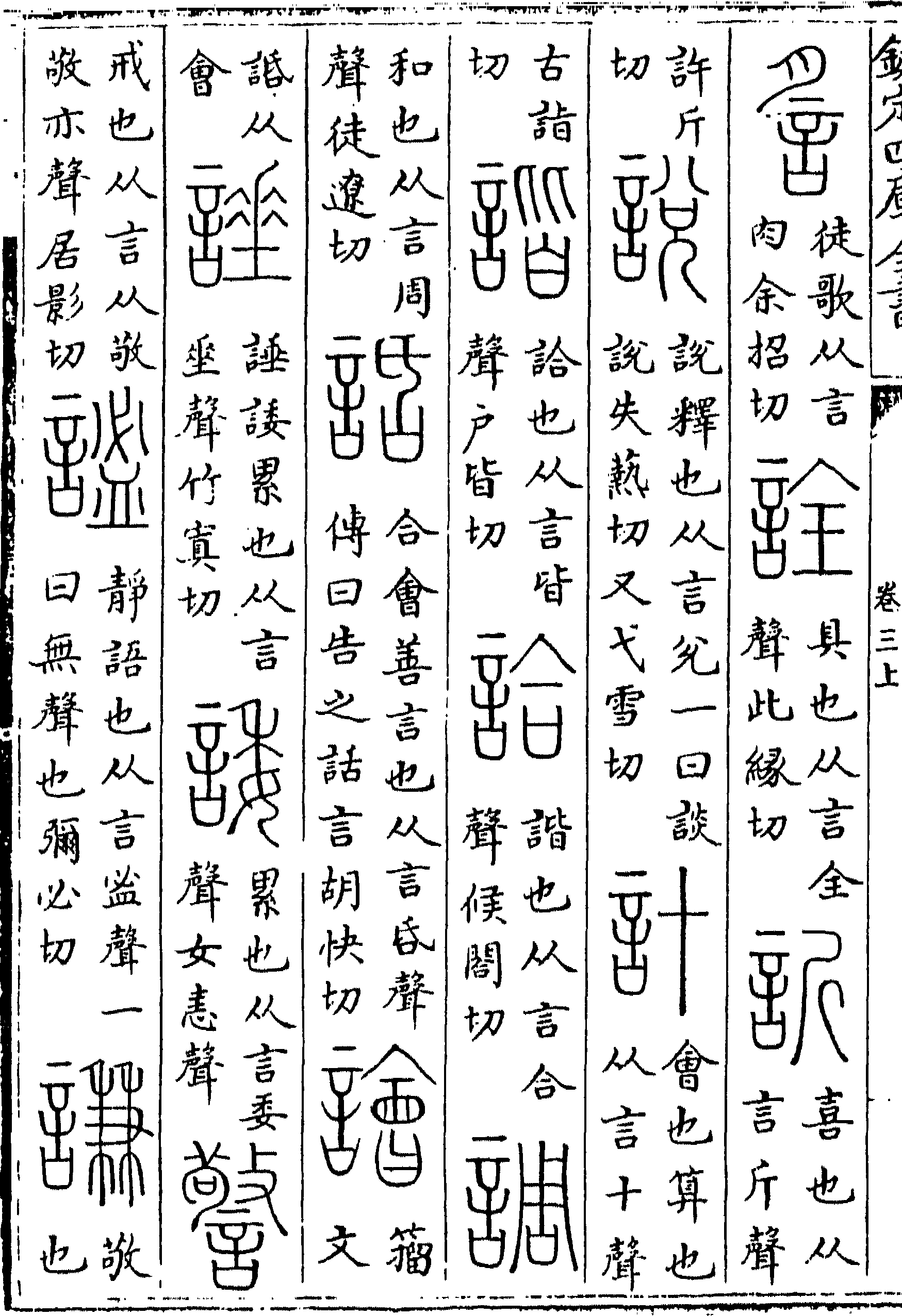

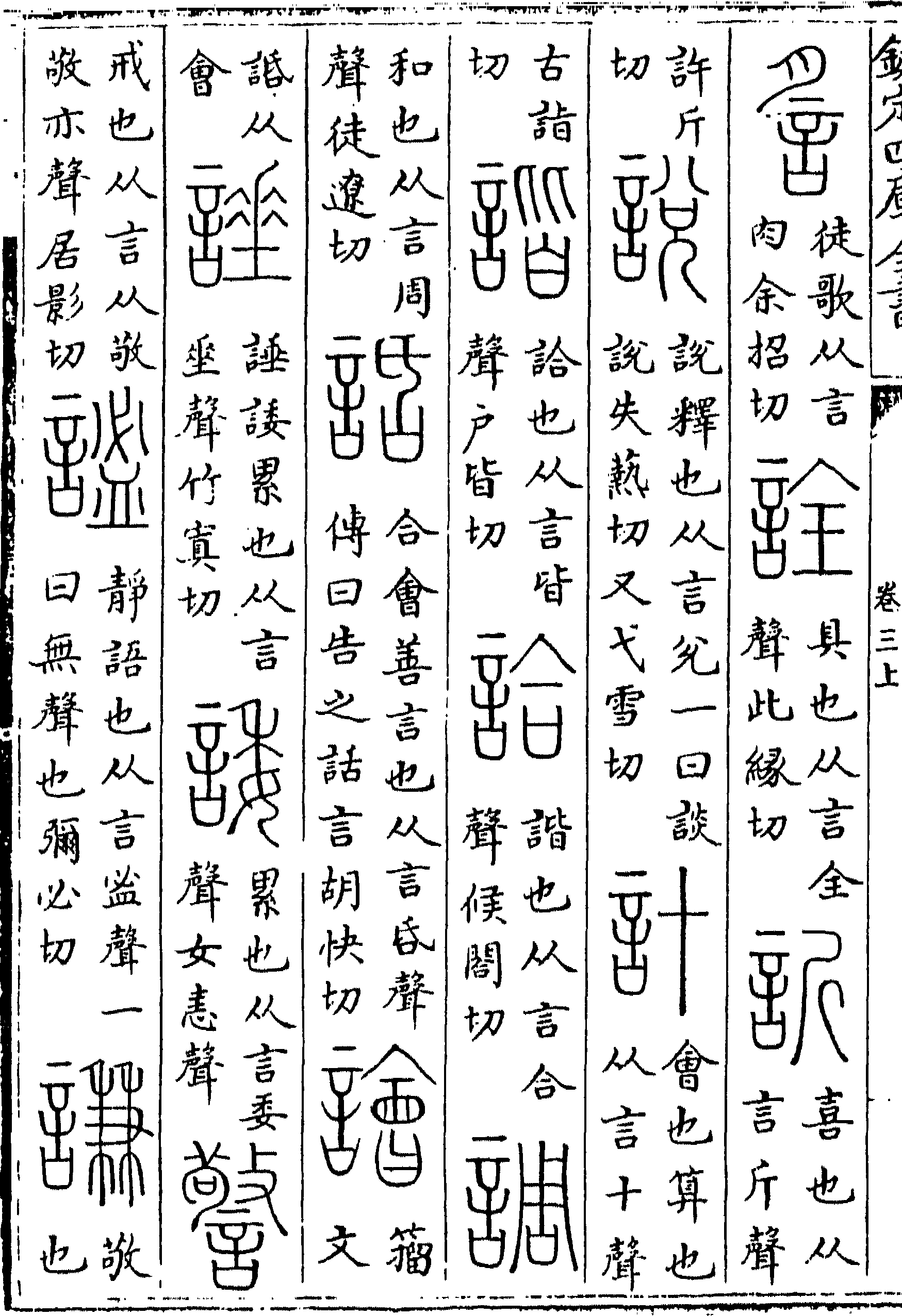

These dictionaries indicated pronunciation using the '' fanqie'' method, dividing a syllable into an initial consonant and the rest, called the final.

Rhyme tables from the Song dynasty

The Song dynasty (; ; 960вҖ“1279) was an imperial dynasty of China that began in 960 and lasted until 1279. The dynasty was founded by Emperor Taizu of Song following his usurpation of the throne of the Later Zhou. The Song conquered the res ...

contain a sophisticated feature analysis of the ''Qieyun'' initials and finals, though not a full phonemic

In phonology and linguistics, a phoneme () is a unit of sound that can distinguish one word from another in a particular language.

For example, in most dialects of English, with the notable exception of the West Midlands and the north-wes ...

analysis.

Moreover, they were influenced by the different pronunciations of that later period.

Scholars have attempted to determine the phonetic content of the various distinctions by examining pronunciations in modern varieties and loans in Japanese, Korean and Vietnamese (the Sinoxenic materials), but many details regarding the finals are still disputed.

The ''Qieyun'' distinguishes the following initials, each traditionally named with an exemplary word and classified according to the rhyme table analysis:

By studying sound glosses given by Eastern Han authors, the Qing philologist Qian Daxin discovered that the Middle Chinese dental and retroflex stop series were not distinguished at that time.

The resulting inventory of 32 initials (omitting the rare initial ) is still used by some scholars within China, such as He Jiuying.

Early in the 20th century, Huang Kan identified 19 Middle Chinese initials that occurred with a wide range of finals, calling them the "original ancient initials", from which the other initials were secondary developments:

Evidence from phonetic series

Although the Chinese writing system is not alphabetic, comparison of words whose characters share a phonetic element (a phonetic series) yields much information about pronunciation.

Often the characters in a phonetic series are still pronounced alike, as in the character (''zhЕҚng'', 'middle'), which was adapted to write the words ''chЕҚng'' ('pour', ) and ''zhЕҚng'' ('loyal', ).

In other cases the words in a phonetic series have very different sounds in any known variety of Chinese, but are assumed to have been similar at the time the characters were chosen.

A key principle, first proposed by the Swedish sinologist Bernhard Karlgren, holds that the initials of words written with the same phonetic component had a common point of articulation in Old Chinese.

For example, since Middle Chinese dentals and retroflex stops occur together in phonetic series, they are traced to a single Old Chinese dental series, with the retroflex stops conditioned by an Old Chinese medial .

The Middle Chinese dental sibilants and retroflex sibilants also occur interchangeably in phonetic series, and are similarly traced to a single Old Chinese sibilant series, with the retroflex sibilants conditioned by the Old Chinese medial .

However, there are several cases where quite different Middle Chinese initials appear together in a phonetic series.

Karlgren and subsequent workers have proposed either additional Old Chinese consonants or initial consonant clusters in such cases.

For example, the Middle Chinese palatal sibilants appear in two distinct kinds of series, with dentals and with velars:

* ''tЕӣjЙҷu'' (< ) 'cycle; Zhou dynasty', ''tieu'' (< ) 'carve' and ''dieu'' (< ) 'adjust'

* ''tЕӣjГӨi-'' (< ) 'cut out' and ''kjГӨi-'' (< ) 'mad dog'

It is believed that the palatals arose from dentals and velars followed by an Old Chinese medial , unless the medial was also present.

While all such dentals were palatalized, the conditions for palatalization of velars are only partly understood (see Medials below).

Similarly, it is proposed that the medial could occur after labials and velars, complementing the instances proposed as sources of Middle Chinese retroflex dentals and sibilants, to account for such connections as:

* ''pjet'' (< ) 'writing pencil' and ''ljwet'' (< ) 'law; rule'

* ''kam'' (< ) 'look at' and ''lГўm'' (< ) 'indigo'

Thus the Middle Chinese lateral ''l-'' is believed to reflect Old Chinese .

Old Chinese voiced and voiceless laterals and are proposed to account for a different group of series such as

* ''dwГўt'' (< ) and ''thwГўt'' (< ) 'peel off', ''jwГӨt'' (< ) 'pleased' and ''ЕӣjwГӨt'' (< OC ) 'speak'

This treatment of the Old Chinese liquids is further supported by Tibeto-Burman cognates and by transcription evidence.

For example, the name of a city (

Although the Chinese writing system is not alphabetic, comparison of words whose characters share a phonetic element (a phonetic series) yields much information about pronunciation.

Often the characters in a phonetic series are still pronounced alike, as in the character (''zhЕҚng'', 'middle'), which was adapted to write the words ''chЕҚng'' ('pour', ) and ''zhЕҚng'' ('loyal', ).

In other cases the words in a phonetic series have very different sounds in any known variety of Chinese, but are assumed to have been similar at the time the characters were chosen.

A key principle, first proposed by the Swedish sinologist Bernhard Karlgren, holds that the initials of words written with the same phonetic component had a common point of articulation in Old Chinese.

For example, since Middle Chinese dentals and retroflex stops occur together in phonetic series, they are traced to a single Old Chinese dental series, with the retroflex stops conditioned by an Old Chinese medial .

The Middle Chinese dental sibilants and retroflex sibilants also occur interchangeably in phonetic series, and are similarly traced to a single Old Chinese sibilant series, with the retroflex sibilants conditioned by the Old Chinese medial .

However, there are several cases where quite different Middle Chinese initials appear together in a phonetic series.

Karlgren and subsequent workers have proposed either additional Old Chinese consonants or initial consonant clusters in such cases.

For example, the Middle Chinese palatal sibilants appear in two distinct kinds of series, with dentals and with velars:

* ''tЕӣjЙҷu'' (< ) 'cycle; Zhou dynasty', ''tieu'' (< ) 'carve' and ''dieu'' (< ) 'adjust'

* ''tЕӣjГӨi-'' (< ) 'cut out' and ''kjГӨi-'' (< ) 'mad dog'

It is believed that the palatals arose from dentals and velars followed by an Old Chinese medial , unless the medial was also present.

While all such dentals were palatalized, the conditions for palatalization of velars are only partly understood (see Medials below).

Similarly, it is proposed that the medial could occur after labials and velars, complementing the instances proposed as sources of Middle Chinese retroflex dentals and sibilants, to account for such connections as:

* ''pjet'' (< ) 'writing pencil' and ''ljwet'' (< ) 'law; rule'

* ''kam'' (< ) 'look at' and ''lГўm'' (< ) 'indigo'

Thus the Middle Chinese lateral ''l-'' is believed to reflect Old Chinese .

Old Chinese voiced and voiceless laterals and are proposed to account for a different group of series such as

* ''dwГўt'' (< ) and ''thwГўt'' (< ) 'peel off', ''jwГӨt'' (< ) 'pleased' and ''ЕӣjwГӨt'' (< OC ) 'speak'

This treatment of the Old Chinese liquids is further supported by Tibeto-Burman cognates and by transcription evidence.

For example, the name of a city (Alexandria Ariana

The first of many Alexandrias in the Far East of the Macedonian Empire, Alexandria in Ariana was a city in what is now Afghanistan, one of the twenty-plus cities founded or renamed by Alexander the Great. The third largest Afghan city, Herat, ...

or Alexandria Arachosia) was transcribed in the '' Book of Han'' chapter 96 as вҹЁвҹ©, which is reconstructed as .

Traces of the earlier liquids are also found in the divergent Waxiang dialect of western Hunan

Hunan (, ; ) is a landlocked province of the People's Republic of China, part of the South Central China region. Located in the middle reaches of the Yangtze watershed, it borders the province-level divisions of Hubei to the north, Jiangxi ...

.

Voiceless nasal initials , and are proposed (following Dong Tonghe and Edwin Pulleyblank) in series such as:

* ''mЙҷk'' 'ink' and ''xЙҷk'' (< ) 'black'

* ''nГўn'' 'difficult' and ''thГўn'' (< ) 'foreshore'

* ''ngjak'' 'cruel' and ''xjak'' (< ) 'to ridicule'

Clusters and so on are proposed (following Karlgren) for alternations of Middle Chinese nasals and ''s-'' such as

* ''Е„Еәjwo'' (< ) 'resemble' and ''sjwo-'' (< ) 'raw silk'

Other cluster initials, including with stops or stops with , have been suggested but their existence and nature remains an open question.

Back initials

TheSong dynasty

The Song dynasty (; ; 960вҖ“1279) was an imperial dynasty of China that began in 960 and lasted until 1279. The dynasty was founded by Emperor Taizu of Song following his usurpation of the throne of the Later Zhou. The Song conquered the res ...

rhyme tables classified ''Qieyun'' syllables as either "open" ( ''kДҒi'') or "closed" ( ''hГ©''), with the latter believed to indicate a medial ''-w-'' or lip rounding.

This medial was unevenly distributed, being distinctive only after velar and laryngeal initials or before ''-ai'', ''-an'' or ''-at''.

This is taken (following AndrГ©-Georges Haudricourt and Sergei Yakhontov

Sergey E. Yakhontov (russian: РЎРөСҖРіРөМҒР№ ЕвгРөМҒРҪСҢРөРІРёСҮ РҜМҒС…РҫРҪСӮРҫРІ, ''Sergej Jevgen'eviДҚ Jachontov''; December 13, 1926 in Leningrad вҖ“ 28 January 2018) was a Russian linguist, an expert in Chinese, comparative, and general li ...

) to indicate that Old Chinese had labiovelar and labiolaryngeal initials but no labiovelar medial.

The remaining occurrences of Middle Chinese ''-w-'' are believed to result from breaking of a back vowel before these codas (see Vowels

A vowel is a syllabic speech sound pronounced without any stricture in the vocal tract. Vowels are one of the two principal classes of speech sounds, the other being the consonant. Vowels vary in quality, in loudness and also in quantity (l ...

below).

As Middle Chinese ''g-'' occurs only in palatal environments, Li attempted to derive both ''g-'' and ''ЙЈ-'' from Old Chinese , but had to assume irregular developments in some cases. Li Rong showed that several words with Middle Chinese initial ''ЙЈ-'' were distinguished in modern Min dialects. For example, 'thick' and 'after' were both ''ЙЈЙҷu:'' in Middle Chinese, but have velar and zero initials respectively in several Min dialects. Most authors now assume both and , with subsequent lenition of in non-palatal environments. Similarly is assumed as the labialized counterpart of .

Pan Wuyun has proposed a revision of the above scheme to account for the fact that Middle Chinese glottal stop and laryngeal fricatives occurred together in phonetic series, unlike dental stops and fricatives, which were usually separated.

Instead of the glottal stop initial and fricatives and , he proposed uvular stops , and , and similarly labio-uvular stops , and in place of , and .

Evidence from Min Chinese

Modern Min dialects, particularly those of northwestFujian

Fujian (; alternately romanized as Fukien or Hokkien) is a province on the southeastern coast of China. Fujian is bordered by Zhejiang to the north, Jiangxi to the west, Guangdong to the south, and the Taiwan Strait to the east. Its c ...

, show reflexes of distinctions not reflected in Middle Chinese.

For example, the following dental initials have been identified in reconstructed proto-Min:

Other points of articulation show similar distinctions within stops and nasals.

Proto-Min voicing is inferred from the development of Min tones, but the phonetic values of the initials are otherwise uncertain.

The sounds indicated as *''-t'', *''-d'', etc. are known as "softened stops" due to their reflexes in Jianyang and nearby Min varieties in northwestern Fujian

Fujian (; alternately romanized as Fukien or Hokkien) is a province on the southeastern coast of China. Fujian is bordered by Zhejiang to the north, Jiangxi to the west, Guangdong to the south, and the Taiwan Strait to the east. Its c ...

, where they appear as fricatives or approximants (e.g. < ''*-p *-t *-k'' in Jianyang) or are missing entirely, while the non-softened variants appear as stops. Evidence from early loans into Yao languages suggests that the softened stops were prenasalized.

These distinctions are assumed by most workers to date from the Old Chinese period, but they are not reflected in the widely accepted inventory of Old Chinese initials given above.

For example, although Old Chinese is believed to have had both voiced and voiceless nasals, only the voiced ones yield Middle Chinese nasals, corresponding to both sorts of proto-Min nasal.

The Old Chinese antecedents of these distinctions are not yet agreed, with researchers proposing a variety of consonant clusters.

Medials

The most contentious aspect of the rhyme tables is their classification of the ''Qieyun'' finals into four divisions ( ''dДӣng''). Most scholars believe that finals of divisions I and IV contained back and front vowels respectively. Division II is believed to represent retroflexion, and is traced back to the Old Chinese medial discussed above, while division III is usually taken as indicating a ''-j-'' medial. Since Karlgren, many scholars have projected this medial (but not ''-w-'') back onto Old Chinese. The following table shows Baxter's account of the Old Chinese initials and medials leading to the combinations of initial and final types found in Early Middle Chinese. Here , , , and stand for consonant classes in Old Chinese. Columns III-3 and III-4 represent the '' chГіngniЗ”'' distinction among some syllables with division-III finals, which are placed in rows 3 or 4 of the Song dynasty rhyme tables. The two are generally identical in modern Chinese varieties, but Sinoxenic forms often have a palatal element for III-4 but not III-3. Baxter's account departs from the earlier reconstruction of Li Fang-Kuei in its treatment of and after labial and guttural initials. Li proposed as the source of palatal initials occurring in phonetic series with velars or laryngeals, found no evidence for , and attributed the ''chongniu'' distinction to the vowel. Following proposals by Pulleyblank, Baxter explains ''chongniu'' using and postulates that plain velars and laryngeals were palatalized when followed by both (but not ) and a front vowel. However a significant number of palatalizations are not explained by this rule.Type A and B syllables

A fundamental distinction within Middle Chinese is between syllables with division-III finals and the rest, labelled types B and A respectively by Pulleyblank. Most scholars believe that type B syllables were characterized by a palatal medial ''-j-'' in Middle Chinese. Although many authors have projected this medial back to a medial in Old Chinese, others have suggested that the Middle Chinese medial was a secondary development not present in Old Chinese. Evidence includes the use of type B syllables to transcribe foreign words lacking any such medial, the lack of the medial in Tibeto-Burman cognates and modern Min reflexes, and the fact that it is ignored in phonetic series. Nonetheless, scholars agree that the difference reflects a real phonological distinction of some sort, often described noncommittally as a distinction between type A and B syllables using a variety of notations. The distinction has been variously ascribed to: * the presence or absence of a prefix. Jakhontov held that type B reflected a prefix , while Ferlus suggested that type A arose from an unstressed prefix (a minor syllable), which conditioned syllabictenseness

In phonology, tenseness or tensing is, most broadly, the pronunciation of a sound with greater muscular effort or constriction than is typical. More specifically, tenseness is the pronunciation of a vowel with less centralization (i.e. either m ...

contrasting with laxness in type B syllables.

* a length distinction of the main vowel. Pulleyblank initially proposed that type B syllables had longer vowels. Later, citing cognates in other Sino-Tibetan languages, Starostin and Zhengzhang independently proposed long vowels for type A and short vowels for type B. The latter proposal might explain the description in some Eastern Han commentaries of type A and B syllables as ''huЗҺnqГ¬'' 'slow breath' and ''jГӯqГ¬'' 'fast breath' respectively.

* a prosodic

In linguistics, prosody () is concerned with elements of speech that are not individual phonetic segments (vowels and consonants) but are properties of syllables and larger units of speech, including linguistic functions such as intonation, s ...

stress-based distinction, as later proposed by Pulleyblank, in which type B syllables were stressed in the first mora, while type A syllables were stressed on the second

* pharyngealization of the initial consonant. Norman suggested that type B syllables (his class C), which comprised over half of the syllables of the ''Qieyun'', were in fact unmarked in Old Chinese. Instead, he proposed that the remaining syllables were marked by retroflexion (the medial) or pharyngealization, either of which prevented palatalization in Middle Chinese. Baxter and Sagart have adopted a variant of this proposal, reconstructing pharyngealized initials in all type A syllables.

Vowels

A reconstruction of Old Chinese finals must explain the rhyming practice of the ''

A reconstruction of Old Chinese finals must explain the rhyming practice of the ''Shijing

The ''Classic of Poetry'', also ''Shijing'' or ''Shih-ching'', translated variously as the ''Book of Songs'', ''Book of Odes'', or simply known as the ''Odes'' or ''Poetry'' (; ''ShД«''), is the oldest existing collection of Chinese poetry, c ...

'', a collection of songs and poetry from the 11th to 7th centuries BC.

Again some of these songs still rhyme in modern varieties of Chinese, but many do not.

This was attributed to lax rhyming practice until the late-Ming dynasty

The Ming dynasty (), officially the Great Ming, was an Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty of China, ruling from 1368 to 1644 following the collapse of the Mongol Empire, Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Ming dynasty was the last ort ...

scholar Chen Di argued that a former consistency had been obscured by sound change.

The systematic study of Old Chinese rhymes began in the 17th century, when Gu Yanwu divided the rhyming words of the ''Shijing'' into ten rhyme groups (''yГ№nbГ№'' ).

These groups were subsequently refined by other scholars, culminating in a standard set of 31 in the 1930s.

One of these scholars, Duan Yucai, stated the important principle that characters in the same phonetic series would be in the same rhyme group, making it possible to assign almost all words to rhyme groups.

Assuming that rhyming syllables had the same main vowel, Li Fang-Kuei proposed a system of four vowels , , and .

He also included three diphthongs , and to account for syllables that were placed in rhyme groups reconstructed with or but were distinguished in Middle Chinese.

In the late 1980s, Zhengzhang Shangfang, Sergei Starostin and William Baxter (following Nicholas Bodman) independently argued that these rhyme groups should be split, refining the 31 traditional rhyme groups into more than 50 groups corresponding to a six-vowel system.

Baxter supported this thesis with a statistical analysis of the rhymes of the ''Shijing'', though there were too few rhymes with codas , and to produce statistically significant results.

The following table illustrates these analyses, listing the names of the 31 traditional rhyme groups with their Middle Chinese reflexes and their postulated Old Chinese vowels in the systems of Li and Baxter.

Following the traditional analysis, the rhyme groups are organized into three parallel sets, depending on the corresponding type of coda in Middle Chinese.

For simplicity, only Middle Chinese finals of divisions I and IV are listed, as the complex vocalism of divisions II and III is believed to reflect the influence of Old Chinese medials and (see previous section).

Tones and final consonants

There has been much controversy over the relationship between final consonants and tones, and indeed whether Old Chinese lacked the tones characteristic of later periods, as first suggested by theMing dynasty

The Ming dynasty (), officially the Great Ming, was an Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty of China, ruling from 1368 to 1644 following the collapse of the Mongol Empire, Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Ming dynasty was the last ort ...

scholar Chen Di.

The four tones of Middle Chinese were first described by Shen Yue around AD 500.

They were the "level" ( ''pГӯng''), "rising" ( ''shЗҺng''), "departing" ( ''qГ№''), and "entering

A checked tone, commonly known by the Chinese calque entering tone, is one of the four syllable types in the phonology of Middle Chinese. Although usually translated as "tone", a checked tone is not a tone in the phonetic sense but rather a syl ...

" ( ''rГ№'') tones, with the last category consisting of the syllables ending in stops (''-p'', ''-t'' or ''-k'').

Although rhymes in the ''Shijing'' usually respect these tone categories, there are many cases of characters that are now pronounced with different tones rhyming together in the songs, mostly between the departing and entering tones.

This led Duan Yucai to suggest that Old Chinese lacked the departing tone.

Wang Niansun (1744вҖ“1832) and Jiang Yougao

Jiang may refer to:

* ''Jiang'' (rank), rank held by general officers in the military of China

*Jiang (surname)

Jiang / Chiang can be a Mandarin transliteration of one of several Chinese surnames:

#JiЗҺng (surname), JiЗҺng (surname и”Ј) (#и”Ј ...

(d.1851) decided that the language had the same tones as Middle Chinese, but some words had later shifted between tones, a view that is still widely held among linguists in China.

Karlgren also noted many cases where words in the departing and entering tones shared a phonetic element within their respective characters, e.g.

* ''lГўi-'' 'depend on' and ''lГўt'' 'wicked'

* ''khЙҷi-'' 'cough' and ''khЙҷk'' 'cut; engrave' GSR 937s,v.

He suggested that the departing tone words in such pairs had ended with a final voiced stop ( or ) in Old Chinese.

Being unwilling to split rhyme groups, Dong Tonghe and Li Fang-Kuei extended these final voiced stops to whole rhyme groups.

The only exceptions were the and groups (Li's and ), in which the traditional analysis already distinguished the syllables with entering tone contacts.

The resulting scarcity of open syllables has been criticized on typological

Typology is the study of types or the systematic classification of the types of something according to their common characteristics. Typology is the act of finding, counting and classification facts with the help of eyes, other senses and logic. Ty ...

grounds.

Wang Li preferred to reallocate words with connections to the entering tone to the corresponding entering tone group, proposing that the final stop was lost after a long vowel.

Another perspective is provided by Haudricourt's demonstration that the tones of Vietnamese, which have a very similar structure to those of Middle Chinese, were derived from earlier final consonants.

The Vietnamese counterparts of the rising and departing tones derived from a final glottal stop and respectively, the latter developing to a glottal fricative .

These glottal post-codas respectively conditioned rising and falling pitch contours, which became distinctive when the post-codas were lost.

Haudricourt also suggested that the Chinese departing tone reflected an Old Chinese derivational suffix .

The connection with stop finals would then be explained as syllables ending with or , with the stops later disappearing, allowing rhymes with open syllables.

The absence of a corresponding labial final could be attributed to early assimilation

Assimilation may refer to:

Culture

*Cultural assimilation, the process whereby a minority group gradually adapts to the customs and attitudes of the prevailing culture and customs

**Language shift, also known as language assimilation, the progre ...

of to .

Pulleyblank supported the theory with several examples of syllables in the departing tone being used to transcribe foreign words ending in ''-s'' into Chinese.

Pulleyblank took Haudricourt's suggestion to its logical conclusion, proposing that the Chinese rising tone had also arisen from a final glottal stop.

Mei Tsu-lin supported this theory with evidence from early transcriptions of Sanskrit words, and pointed out that rising tone words end in a glottal stop in some modern Chinese dialects, e.g. Wenzhounese and some Min dialects.

In addition, most of the entering tone words that rhyme with rising tone words in the ''Shijing'' end in ''-k''.

Together, these hypotheses lead to the following set of Old Chinese syllable codas:

Baxter also speculated on the possibility of a glottal stop occurring after oral stop finals.

The evidence is limited, and consists mainly of contacts between rising tone syllables and ''-k'' finals, which could alternatively be explained as phonetic similarity.

To account for phonetic series and rhymes in which MC ''-j'' alternates with ''-n'', Sergei Starostin proposed that MC ''-n'' in such cases derived from Old Chinese .

Other scholars have suggested that such contacts are due to dialectal mixture, citing evidence that had disappeared from eastern dialects by the Eastern Han period.

See also

* Historical Chinese phonologyNotes

References

Works cited * * * * * * * *English translation

by Marc Brunelle) *

English translation

by Guillaume Jacques) * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * Reprinted by ''ShДҒngwГ№ YГ¬nshЕ«guЗҺn ChЕ«bЗҺn'', Beijing in 2008, . * *

Further reading

* * * Translation of Chapter 2 (Phonetics) of . *External links

Tutorials"Introduction to Chinese Historical Phonology"

Guillaume Jacques, European Association of Chinese Linguistics Spring School in Chinese Linguistics, International Institute for Asian Studies, Leiden, March 2006.

"Summer School on Old Chinese Phonology"

(videos), William Baxter and Laurent Sagart, Гүcole des Hautes Гүtudes en Sciences Sociales, Paris, July 2007. Databases of reconstructions

StarLing database

by Georgiy Starostin.

The Baxter-Sagart reconstruction of Old Chinese

дёҠеҸӨйҹізі»- йҹ»е…ёз¶І

е°Ҹеӯёе ӮдёҠеҸӨйҹі - дёӯеӨ®з ”究йҷў

жқҺж–№жЎӮдёҠеҸӨйҹійҹ»иЎЁ

{{DEFAULTSORT:Old Chinese Phonology

Phonology

Phonology is the branch of linguistics that studies how languages or dialects systematically organize their sounds or, for sign languages, their constituent parts of signs. The term can also refer specifically to the sound or sign system of a ...

Sino-Tibetan phonologies