Occupied Germany on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Germany was already de facto occupied by the Allies from the real fall of

File:Germany Under Allied Occupation CL3279.jpg, Royal Air Force's Malcolm Club in

The

The

The Soviet occupation zone incorporated

The Soviet occupation zone incorporated

"Vor 50 Jahren: Der 15. April 1950. Vertriebene finden eine neue Heimat in Rheinland-Pfalz"

, on

Rheinland-Pfalz Landesarchivverwaltung

retrieved on 4 March 2013. However, the native population, returning after Nazi-imposed removals (e.g., political and Jewish refugees) and war-related relocations (e.g., evacuation from air raids), were allowed to return home in the areas under French control. The other Allies complained that they had to shoulder the burden to feed, house and clothe the expellees who had to leave their belongings behind. In practice, each of the four occupying powers wielded government authority in their respective zones and carried out different policies toward the population and local and state governments there. A uniform administration of the western zones evolved, known first as the

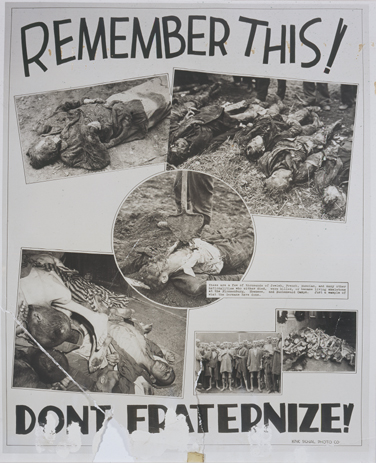

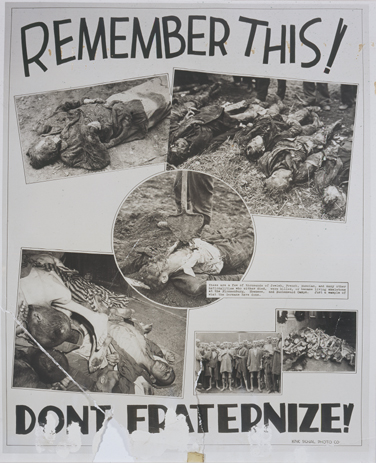

At the end of the war, General Eisenhower issued a non-

At the end of the war, General Eisenhower issued a non-

The Expulsion of the ‘German’ Communities from Eastern Europe at the End of the Second World War

Steffen Prauser and Arfon Rees, European University Institute, Florence, Department of history and civilization Millions of people were expelled from

Transforming Occupation in the Western Zones of Germany: Politics, Everyday Life and Social Interactions, 1945-55

(Bloomsbury, 2018). * Golay, John Ford. ''The Founding of the Federal Republic of Germany'' (University of Chicago Press, 1958) * Jarausch, Konrad H.''After Hitler: Recivilizing Germans, 1945–1995'' (2008) * Junker, Detlef, ed. ''The United States and Germany in the Era of the Cold War'' (2 vol 2004), 150 short essays by scholars covering 1945–199

excerpt and text search vol 1 excerpt and text search vol 2

* Knowles, Christopher. "The British Occupation of Germany, 1945–49: A Case Study in Post-Conflict Reconstruction." ''The RUSI Journal'' (2013) 158#6 pp: 84–91. * Knowles, Christopher. Winning the Peace: the British in Occupied Germany, 1945–1948. (PhD Dissertation King's College London, 2014)

online

later published as ''Winning the Peace: The British in Occupied Germany, 1945-1948'', 2017,

online review

* Schwarz, Hans-Peter. ''Konrad Adenauer: A German Politician and Statesman in a Period of War, Revolution and Reconstruction'' (2 vol 1995

full text vol 1

* Taylor, Frederick. ''Exorcising Hitler: the occupation and denazification of Germany'' (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2011) * Weber, Jurgen. ''Germany, 1945–1990'' (Central European University Press, 2004

online edition

online

* Clay, Lucius D. ''The papers of General Lucius D. Clay: Germany, 1945–1949'' (2 vol. 1974) * Miller, Paul D. "A bibliographic essay on the Allied occupation and reconstruction of West Germany, 1945–1955." ''Small Wars & Insurgencies'' (2013) 24#4 pp: 751–759.

The Struggle for Germany and the Origins of the Cold War

by Melvyn P. Leffler {{DEFAULTSORT:Allied-Occupied Germany British military occupations Dwight D. Eisenhower France–Germany relations French military occupations Germany–Soviet Union relations Germany–United Kingdom relations Germany–United States relations States and territories established in 1945

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

in World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

on 8 May 1945 to the establishment of the East Germany

East Germany, officially the German Democratic Republic (GDR; german: Deutsche Demokratische Republik, , DDR, ), was a country that existed from its creation on 7 October 1949 until its dissolution on 3 October 1990. In these years the state ...

on 7 October 1949. The Allies (United States, United Kingdom, Soviet Union, and France) asserted joint authority and sovereignty at the 1945 Berlin Declaration. At first, defining Allied-occupied Germany as all territories of the former German Reich

German ''Reich'' (lit. German Realm, German Empire, from german: Deutsches Reich, ) was the constitutional name for the German nation state that existed from 1871 to 1945. The ''Reich'' became understood as deriving its authority and sovereignty ...

before Nazi annexing Austria; however later in the 1945 Potsdam Conference

The Potsdam Conference (german: Potsdamer Konferenz) was held at Potsdam in the Soviet occupation zone from July 17 to August 2, 1945, to allow the three leading Allies to plan the postwar peace, while avoiding the mistakes of the Paris Pe ...

of Allies, the Potsdam Agreement

The Potsdam Agreement (german: Potsdamer Abkommen) was the agreement between three of the Allies of World War II: the United Kingdom, the United States, and the Soviet Union on 1 August 1945. A product of the Potsdam Conference, it concerned t ...

decided the new German border as it stands today. Said border gave Poland and the Soviet Union all regions of Germany (eastern parts of Pomerania

Pomerania ( pl, Pomorze; german: Pommern; Kashubian: ''Pòmòrskô''; sv, Pommern) is a historical region on the southern shore of the Baltic Sea in Central Europe, split between Poland and Germany. The western part of Pomerania belongs to t ...

, Neumark

The Neumark (), also known as the New March ( pl, Nowa Marchia) or as East Brandenburg (), was a region of the Margraviate of Brandenburg and its successors located east of the Oder River in territory which became part of Poland in 1945.

Cal ...

, Posen-West Prussia

The Frontier March of Posen-West Prussia (german: Grenzmark Posen-Westpreußen, pl, Marchia Graniczna Poznańsko-Zachodniopruska) was a province of Prussia from 1922 to 1938. Posen-West Prussia was established in 1922 as a province of the Free ...

, Free City of Danzig

The Free City of Danzig (german: Freie Stadt Danzig; pl, Wolne Miasto Gdańsk; csb, Wòlny Gard Gduńsk) was a city-state under the protection of the League of Nations between 1920 and 1939, consisting of the Baltic Sea port of Danzig (now Gda ...

, East-Prussia & Silesia

Silesia (, also , ) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at around 8,000,000. Silesia is spli ...

) east of the Oder–Neisse line

The Oder–Neisse line (german: Oder-Neiße-Grenze, pl, granica na Odrze i Nysie Łużyckiej) is the basis of most of the international border between Germany and Poland from 1990. It runs mainly along the Oder and Lusatian Neisse rivers ...

and divided the remaining "Germany as a whole" into the four occupation zones for administrative purposes under the three Western Allies (the United States, the United Kingdom, and France) and the Soviet Union. Although the three of Allies (United States, United Kingdom, and Soviet Union) agreed about the occupation and division in Germany in the legal protocol in London 1944 before, the four occupied zones with new border of Germany were only agreed by 3 Allies at the February 1945 Yalta Conference

The Yalta Conference (codenamed Argonaut), also known as the Crimea Conference, held 4–11 February 1945, was the World War II meeting of the heads of government of the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union to discuss the post ...

.

All territories annexed by Germany before the war from Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

and Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

were returned to these countries. The Memel Territory, annexed by Germany from Lithuania before the war, was annexed by the Soviet Union in 1945 and transferred to the Lithuanian SSR

The Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic (Lithuanian SSR; lt, Lietuvos Tarybų Socialistinė Respublika; russian: Литовская Советская Социалистическая Республика, Litovskaya Sovetskaya Sotsialistiche ...

. All territories annexed by Germany during the war from Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to ...

, France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan ar ...

, Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

, Luxembourg

Luxembourg ( ; lb, Lëtzebuerg ; french: link=no, Luxembourg; german: link=no, Luxemburg), officially the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, ; french: link=no, Grand-Duché de Luxembourg ; german: link=no, Großherzogtum Luxemburg is a small land ...

, Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, , is a country in Central Europe. Poland is divided into Voivodeships of Poland, sixteen voivodeships and is the fifth most populous member state of the European Union (EU), with over 38 mill ...

and Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia (; sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Jugoslavija, Југославија ; sl, Jugoslavija ; mk, Југославија ;; rup, Iugoslavia; hu, Jugoszlávia; rue, label= Pannonian Rusyn, Югославия, translit=Juhoslavij ...

were returned to their respective countries.

Deviating from the occupation zones planned according to the London Protocol in 1944, at Potsdam, the United States, United Kingdom and the Soviet Union approved the detachment from Germany of the territories east of the Oder–Neisse line

The Oder–Neisse line (german: Oder-Neiße-Grenze, pl, granica na Odrze i Nysie Łużyckiej) is the basis of most of the international border between Germany and Poland from 1990. It runs mainly along the Oder and Lusatian Neisse rivers ...

, with the exact line of the boundary to be determined in a final German peace treaty. This treaty was expected to confirm the shifting westward of Poland's borders, as the United Kingdom and United States committed themselves to support the permanent incorporation of eastern Germany into Poland and the Soviet Union. From March 1945 to July 1945, these former eastern territories of Germany

The former eastern territories of Germany (german: Ehemalige deutsche Ostgebiete) refer in present-day Germany to those territories east of the current eastern border of Germany i.e. Oder–Neisse line which historically had been considered Ger ...

had been administered under Soviet military occupation authorities, but following the Potsdam Conference they were handed over to Soviet and Polish civilian administrations and ceased to constitute part of Allied-occupied Germany.

In the closing weeks of fighting in Europe, United States forces had pushed beyond the agreed boundaries for the future zones of occupation, in some places by as much as . The so-called line of contact

The Line of Contact marked the farthest advance of American, British, French, and Soviet armies into German controlled territory at the end of World War II in Europe. In general a "line of contact" refers to the demarcation between two or mo ...

between Soviet and U.S. forces at the end of hostilities, mostly lying eastward of the July 1945-established inner German border

The inner German border (german: Innerdeutsche Grenze or ; initially also ) was the border between the German Democratic Republic (GDR, East Germany) and the West Germany, Federal Republic of Germany (FRG, West Germany) from 1949 to 1990. Not ...

, was temporary. After two months in which they had held areas that had been assigned to the Soviet zone, U.S. forces withdrew in the first days of July 1945. Some have concluded that this was a crucial move that persuaded the Soviet Union to allow American, British and French forces into their designated sectors in Berlin, which occurred at roughly the same time, although the need for intelligence gathering (Operation Paperclip

Operation Paperclip was a secret United States intelligence program in which more than 1,600 German scientists, engineers, and technicians were taken from the former Nazi Germany to the U.S. for government employment after the end of World War ...

) may also have been a factor. In 1949, two German states of East

East or Orient is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from west and is the direction from which the Sun rises on the Earth.

Etymology

As in other languages, the word is formed from the fa ...

and West Germany

West Germany is the colloquial term used to indicate the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG; german: Bundesrepublik Deutschland , BRD) between its formation on 23 May 1949 and the German reunification through the accession of East Germany on 3 O ...

emerged.

Occupation zones

American Zone

The American zone inSouthern Germany

Southern Germany () is a region of Germany which has no exact boundary, but is generally taken to include the areas in which Upper German dialects are spoken, historically the stem duchies of Bavaria and Swabia or, in a modern context, Bavaria ...

consisted of Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total l ...

(without the Rhine Palatinate Region and the Lindau District, both part of the French zone) and Hesse

Hesse (, , ) or Hessia (, ; german: Hessen ), officially the State of Hessen (german: links=no, Land Hessen), is a state in Germany. Its capital city is Wiesbaden, and the largest urban area is Frankfurt. Two other major historic cities are Da ...

(without Rhenish Hesse

Rhenish Hesse or Rhine HesseDickinson, Robert E (1964). ''Germany: A regional and economic geography'' (2nd ed.). London: Methuen, p. 542. . (german: Rheinhessen) is a region and a former government district () in the German state of Rhineland- ...

and Montabaur Region, both part of the French zone) with a new capital in Wiesbaden

Wiesbaden () is a city in central western Germany and the capital of the state of Hesse. , it had 290,955 inhabitants, plus approximately 21,000 United States citizens (mostly associated with the United States Army). The Wiesbaden urban area ...

, and of northern parts of ''Württemberg'' and ''Baden''. Those formed Württemberg-Baden

Württemberg-Baden was a state of the Federal Republic of Germany. It was created in 1945 by the United States occupation forces, after the previous states of Baden and Württemberg had been split up between the US and French occupation zones. ...

and became northern portions of the present-day German state of Baden-Württemberg

Baden-Württemberg (; ), commonly shortened to BW or BaWü, is a German state () in Southwest Germany, east of the Rhine, which forms the southern part of Germany's western border with France. With more than 11.07 million inhabitants across a ...

founded in 1952.

The ports of Bremen

Bremen (Low German also: ''Breem'' or ''Bräm''), officially the City Municipality of Bremen (german: Stadtgemeinde Bremen, ), is the capital of the Germany, German States of Germany, state Bremen (state), Free Hanseatic City of Bremen (''Freie H ...

(on the lower Weser River

The Weser () is a river of Lower Saxony in north-west Germany. It begins at Hannoversch Münden through the confluence of the Werra and Fulda. It passes through the Hanseatic city of Bremen. Its mouth is further north against the ports of Br ...

) and Bremerhaven

Bremerhaven (, , Low German: ''Bremerhoben'') is a city at the seaport of the Free Hanseatic City of Bremen, a state of the Federal Republic of Germany.

It forms a semi-enclave in the state of Lower Saxony and is located at the mouth of the R ...

(at the Weser estuary of the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian S ...

) were also placed under U.S. control because of the U.S. request to have certain toeholds in Northern Germany

Northern Germany (german: link=no, Norddeutschland) is a linguistic, geographic, socio-cultural and historic region in the northern part of Germany which includes the coastal states of Schleswig-Holstein, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern and Lower Saxony an ...

.

At the end of October 1946, the American Zone had a population of:

* Bavaria 8.7 million

* Hesse 3.97 million

* Württemberg-Baden 3.6 million

* Bremen 0.48 million"I. Gebiet und Bevölkerung"Statistisches Bundesamt

The Federal Statistical Office (german: Statistisches Bundesamt, shortened ''Destatis'') is a federal authority of Germany. It reports to the Federal Ministry of the Interior.

The Office is responsible for collecting, processing, presenting and ...

. Wiesbaden.

The headquarters of the American military government was the former IG Farben Building

The IG Farben Building – also known as the Poelzig Building and the Abrams Building, formerly informally called The Pentagon of Europe – is a building complex in Frankfurt, Germany, which currently serves as the main structure of the West ...

in Frankfurt am Main

Frankfurt, officially Frankfurt am Main (; Hessian dialects, Hessian: , "Franks, Frank ford (crossing), ford on the Main (river), Main"), is the most populous city in the States of Germany, German state of Hesse. Its 791,000 inhabitants as o ...

.

Following the complete closure of all Nazi German media, the launch and operation of completely new newspaper titles began by licensing carefully selected Germans as publishers. Licenses were granted to Germans not involved in Nazi propaganda to establish those newspapers, including ''Frankfurter Rundschau

The ''Frankfurter Rundschau'' (FR) is a German daily newspaper, based in Frankfurt am Main. It is published every day but Sunday as a city, two regional and one nationwide issues and offers an online edition (see link below) as well as an e-p ...

'' (August 1945), ''Der Tagesspiegel

''Der Tagesspiegel'' (meaning ''The Daily Mirror'') is a German daily newspaper. It has regional correspondent offices in Washington D.C. and Potsdam. It is the only major newspaper in the capital to have increased its circulation, now 148,000, ...

'' (Berlin; September 1945), and ''Süddeutsche Zeitung

The ''Süddeutsche Zeitung'' (; ), published in Munich, Bavaria, is one of the largest daily newspapers in Germany. The tone of SZ is mainly described as centre-left, liberal, social-liberal, progressive-liberal, and social-democrat.

Histo ...

'' (Munich; October 1945). Radio stations were run by the military government. Later, ''Radio Frankfurt'', ''Radio München'' (Munich) and ''Radio Stuttgart'' gave way for the ''Hessischer Rundfunk

Hessischer Rundfunk (HR; "Hesse Broadcasting") is the German state of Hesse's public broadcasting corporation. Headquartered in Frankfurt, it is a member of the national consortium of German public broadcasting corporations, ARD.

Studios

Do ...

'', ''Bayerischer Rundfunk

Bayerischer Rundfunk (BR; "Bavarian Broadcasting") is a public-service radio and television broadcaster, based in Munich, capital city of the Free State of Bavaria in Germany. BR is a member organization of the ARD consortium of public broadca ...

'', and '' Süddeutscher Rundfunk'', respectively. The RIAS in West-Berlin remained a radio station under U.S. control.

British Zone

By May 1945 the British and Canadian Armies had liberated the Netherlands and had conquered Northern Germany. The Canadian forces went home following the German surrender, leaving Northern Germany to be occupied by the British. TheBritish Army of the Rhine

There have been two formations named British Army of the Rhine (BAOR). Both were originally occupation forces in Germany, one after the First World War and the other after the Second World War. Both formations had areas of responsibility locate ...

was formed on 25 August 1945 from the British Liberation Army.

In July the British withdrew from Mecklenburg

Mecklenburg (; nds, label=Low German, Mękel(n)borg ) is a historical region in northern Germany comprising the western and larger part of the federal-state Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania. The largest cities of the region are Rostock, Schwer ...

's capital Schwerin

Schwerin (; Mecklenburgian Low German: ''Swerin''; Latin: ''Suerina'', ''Suerinum'') is the capital and second-largest city of the northeastern German state of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern as well as of the region of Mecklenburg, after Rostock. ...

which they had taken over from the Americans a few weeks before, as it had previously been agreed to be occupied by the Soviet Army

uk, Радянська армія

, image = File:Communist star with golden border and red rims.svg

, alt =

, caption = Emblem of the Soviet Army

, start_date ...

. The Control Commission for Germany (British Element)

Control may refer to:

Basic meanings Economics and business

* Control (management), an element of management

* Control, an element of management accounting

* Comptroller (or controller), a senior financial officer in an organization

* Controll ...

(CCG/BE) ceded more slices of its area of occupation to the Soviet Union – specifically the Amt Neuhaus

Amt Neuhaus is a municipality in the District of Lüneburg, in Lower Saxony, Germany. ''Amt'' means "municipal office" in German. The original "municipal office of ''Neuhaus''" existed since at least the 17th century until 1885, consecutively as p ...

of Hanover

Hanover (; german: Hannover ; nds, Hannober) is the capital and largest city of the German state of Lower Saxony. Its 535,932 (2021) inhabitants make it the 13th-largest city in Germany as well as the fourth-largest city in Northern Germany ...

and some exclaves and fringes of Brunswick, for example the County of Blankenburg

The County of Blankenburg (german: Grafschaft Blankenburg) was a state of the Holy Roman Empire. Its capital was Blankenburg, it was located in and near the Harz mountains.

History

County of Blankenburg

About 1123 Lothair of Supplinburg, the ...

, and exchanged some villages between British Holstein

Holstein (; nds, label= Northern Low Saxon, Holsteen; da, Holsten; Latin and historical en, Holsatia, italic=yes) is the region between the rivers Elbe and Eider. It is the southern half of Schleswig-Holstein, the northernmost state of Germ ...

and Soviet Mecklenburg under the Barber-Lyashchenko Agreement.

Within the British Zone of Occupation, the CCG/BE re-established the city of Hamburg

Hamburg (, ; nds, label=Hamburg German, Low Saxon, Hamborg ), officially the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg (german: Freie und Hansestadt Hamburg; nds, label=Low Saxon, Friee un Hansestadt Hamborg),. is the List of cities in Germany by popul ...

as a German state, but with borders that had been drawn by the Nazi government in 1937. The British also created the new German states of:

* Schleswig-Holstein

Schleswig-Holstein (; da, Slesvig-Holsten; nds, Sleswig-Holsteen; frr, Slaswik-Holstiinj) is the northernmost of the 16 states of Germany, comprising most of the historical duchy of Holstein and the southern part of the former Duchy of Sc ...

– emerging in 1946 from the Prussian

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an ...

Province of Schleswig-Holstein;

* Lower Saxony

Lower Saxony (german: Niedersachsen ; nds, Neddersassen; stq, Läichsaksen) is a German state (') in northwestern Germany. It is the second-largest state by land area, with , and fourth-largest in population (8 million in 2021) among the 16 ...

– the merger of Brunswick, Oldenburg, and Schaumburg-Lippe

Schaumburg-Lippe, also Lippe-Schaumburg, was created as a county in 1647, became a principality in 1807, a free state in 1918, and was until 1946 a small state in Germany, located in the present day state of Lower Saxony, with its capital at Bück ...

with the state of Hanover

The State of Hanover (german: Land Hannover) was a short-lived state within the British Zone of Allied-occupied Germany. It existed for 92 days in the course of the dissolution of the Free State of Prussia after World War II until the foundatio ...

in 1946; and

* North Rhine-Westphalia

North Rhine-Westphalia (german: Nordrhein-Westfalen, ; li, Noordrien-Wesfale ; nds, Noordrhien-Westfalen; ksh, Noodrhing-Wäßßfaale), commonly shortened to NRW (), is a state (''Land'') in Western Germany. With more than 18 million inhab ...

– the merger of Lippe

Lippe () is a ''Kreis'' ( district) in the east of North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. Neighboring districts are Herford, Minden-Lübbecke, Höxter, Paderborn, Gütersloh, and district-free Bielefeld, which forms the region Ostwestfalen-Lippe ...

with the Prussian provinces of the Rhineland

The Rhineland (german: Rheinland; french: Rhénanie; nl, Rijnland; ksh, Rhingland; Latinised name: ''Rhenania'') is a loosely defined area of Western Germany along the Rhine, chiefly its middle section.

Term

Historically, the Rhineland ...

(northern part) and Westphalia

Westphalia (; german: Westfalen ; nds, Westfalen ) is a region of northwestern Germany and one of the three historic parts of the state of North Rhine-Westphalia. It has an area of and 7.9 million inhabitants.

The territory of the regi ...

– during 1946–47.

Also in 1947, the American Zone of Occupation being inland had no port facilities – thus the Free Hanseatic City of Bremen and Bremerhaven

Bremerhaven (, , Low German: ''Bremerhoben'') is a city at the seaport of the Free Hanseatic City of Bremen, a state of the Federal Republic of Germany.

It forms a semi-enclave in the state of Lower Saxony and is located at the mouth of the R ...

became exclaves within the British Zone.

At the end of October 1946, the British Zone had a population of:

* North Rhine-Westphalia 11.7 million

* Lower Saxony 6.2 million

* Schleswig-Holstein 2.6 million

* Hamburg 1.4 million

The British headquarters were originally based in Bad Oeynhausen from 1946, but in 1954 it was moved to Mönchengladbach

Mönchengladbach (, li, Jlabbach ) is a city in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. It is located west of the Rhine, halfway between Düsseldorf and the Dutch border.

Geography Municipal subdivisions

Since 2009, the territory of Mönchengladba ...

where it was known as JHQ Rheindahlen.

Another special feature of the British zone was the Enclave of Bonn

The federal city of Bonn ( lat, Bonna) is a city on the banks of the Rhine in the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia, with a population of over 300,000. About south-southeast of Cologne, Bonn is in the southernmost part of the Rhine-Ru ...

. It was created in July 1949 and was not under British or any other allied control. Instead it was under the control of the Allied High Commission. In June 1950, Ivone Kirkpatrick became the British High Commissioner for Germany. Kirkpatrick carried immense responsibility particularly with respect to the negotiation of the Bonn–Paris conventions during 1951–1952, which terminated the occupation and prepared the way for the rearmament of West Germany.

Schleswig

The Duchy of Schleswig ( da, Hertugdømmet Slesvig; german: Herzogtum Schleswig; nds, Hartogdom Sleswig; frr, Härtochduum Slaswik) was a duchy in Southern Jutland () covering the area between about 60 km (35 miles) north and 70 km ...

, formerly the Stadt Hamburg Hotel in late 1945.

File:Bundesarchiv Bild 183-2007-0403-501, Berlin, britischer Panzerwagen,am Brandenburger Tor.jpg, British armoured car, at the Brandenburg Gate in Berlin, 1950

Belgian, Polish and Norwegian Zones

Army units from other countries were stationed within the British occupation zone. The Belgians were allocated a territory which was garrisoned by their troops. The zone formed a strip from the Belgian-German border at the south of the British zone, and included the important cities ofCologne

Cologne ( ; german: Köln ; ksh, Kölle ) is the largest city of the German western state of North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW) and the fourth-most populous city of Germany with 1.1 million inhabitants in the city proper and 3.6 millio ...

and Aachen. The Belgian army of occupation in Germany (known as the Belgian Forces in Germany from 1951) became autonomous in 1946 under the command, initially, of Jean-Baptiste Piron

Lieutenant General Jean-Baptiste Piron (10 April 1896 – 4 September 1974) was a Belgian military officer, best known for his role in the Free Belgian forces during World War II as commander of the 1st Belgian Infantry Brigade, widely kno ...

. Belgian soldiers remained in Germany until 31 December 2005.

Polish units mainly from 1st Armoured Division were stationed in the northern area of the district of Emsland

Landkreis Emsland () is a district in Lower Saxony, Germany named after the river Ems. It is bounded by (from the north and clockwise) the districts of Leer, Cloppenburg and Osnabrück, the state of North Rhine-Westphalia (district of Steinf ...

as well as in the areas of Oldenburg and Leer

Leer may refer to:

* Leer, Lower Saxony, town in Germany

** Leer (district), containing the town in Lower Saxony, Germany

** Leer (Ostfriesland) railway station

* Leer, South Sudan, town in South Sudan

** Leer County, an administrative division of ...

. This region bordered the Netherlands and covered an area of 6,500 km2, and was originally intended to serve as a collection and dispersal territory for the millions of Polish displaced persons in Germany and western Europe after the war. Early British proposals for this to form the basis of a formal Polish Zone of Occupation, were however, soon abandoned due to Soviet opposition. The zone had a large camp constructed largely for displaced persons and was administered by the Polish government in exile

The Polish government-in-exile, officially known as the Government of the Republic of Poland in exile ( pl, Rząd Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej na uchodźstwie), was the government in exile of Poland formed in the aftermath of the Invasion of Pola ...

. The administrative centre of the Polish occupation zone was the city of Haren the German population of which was temporarily removed. The city was renamed ''Maczków'' (after Stanisław Maczek

Lieutenant General Stanisław Maczek (; 31 March 1892 – 11 December 1994) was a Polish tank commander of World War II, whose division was instrumental in the Allied liberation of France, closing the Falaise pocket, resulting in the destructio ...

) from 1945 to 1947. Once the British recognised the pro-Soviet government in Poland, and withdrew recognition from the London-based Polish government in exile, the Emsland zone became more of an embarrassment. Polish units within the British Army were demobilised in June 1947. The expelled German populations were allowed to return and the last Polish residents left in 1948.

In 1946, the Norwegian Brigade Group in Germany had 4,000 soldiers in Hanover; amongst whom was future Chancellor

Chancellor ( la, cancellarius) is a title of various official positions in the governments of many nations. The original chancellors were the of Roman courts of justice—ushers, who sat at the or lattice work screens of a basilica or law cou ...

Willy Brandt

Willy Brandt (; born Herbert Ernst Karl Frahm; 18 December 1913 – 8 October 1992) was a German politician and statesman who was leader of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) from 1964 to 1987 and served as the chancellor of West Ge ...

(then a Norwegian citizen) as press attaché.

French Zone

The

The French Republic

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

was at first not granted an occupation zone in Germany, but the British and American governments later agreed to cede some western parts of their zones of occupation to the French Army

The French Army, officially known as the Land Army (french: Armée de Terre, ), is the land-based and largest component of the French Armed Forces. It is responsible to the Government of France, along with the other components of the Armed Force ...

. In April and May 1945, the French 1st Army

The First Army (french: 1re Armée) was a field army of France that fought during World War I and World War II. It was also active during the Cold War.

First World War

On mobilization in August 1914, General Auguste Dubail was put in the c ...

had captured Karlsruhe

Karlsruhe ( , , ; South Franconian German, South Franconian: ''Kallsruh'') is the List of cities in Baden-Württemberg by population, third-largest city of the German States of Germany, state (''Land'') of Baden-Württemberg after its capital o ...

and Stuttgart, and conquered a territory extending to Hitler's Eagle's Nest and the westernmost part of Austria. In July, the French relinquished Stuttgart to the Americans, and in exchange were given control over cities west of the Rhine such as Mainz

Mainz () is the capital and largest city of Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany.

Mainz is on the left bank of the Rhine, opposite to the place that the Main joins the Rhine. Downstream of the confluence, the Rhine flows to the north-west, with Ma ...

and Koblenz

Koblenz (; Moselle Franconian: ''Kowelenz''), spelled Coblenz before 1926, is a German city on the banks of the Rhine and the Moselle, a multi-nation tributary.

Koblenz was established as a Roman military post by Drusus around 8 B.C. Its na ...

. All this resulted in two barely contiguous areas of Germany along the French border which met at just a single point along the River Rhine

The Rhine ; french: Rhin ; nl, Rijn ; wa, Rén ; li, Rien; rm, label=Sursilvan, Rein, rm, label=Sutsilvan and Surmiran, Ragn, rm, label=Rumantsch Grischun, Vallader and Puter, Rain; it, Reno ; gsw, Rhi(n), including in Alsatian dialect, Al ...

. Three German states (''Land

Land, also known as dry land, ground, or earth, is the solid terrestrial surface of the planet Earth that is not submerged by the ocean or other bodies of water. It makes up 29% of Earth's surface and includes the continents and various isl ...

'') were established: Rheinland Pfalz in the North and West and on the other hand Württemberg-Hohenzollern

Württemberg-Hohenzollern (french: Wurtemberg-Hohenzollern ) was a West German state created in 1945 as part of the French post-World War II occupation zone. Its capital was Tübingen. In 1952, it was merged into the newly founded state of Bade ...

and South Baden

South Baden (german: Südbaden; ), formed in December 1945 from the southern half of the former Republic of Baden, was a subdivision of the French occupation zone of post-World War II Germany. The state was later renamed to Baden and became a fo ...

, who later formed Baden-Württemberg

Baden-Württemberg (; ), commonly shortened to BW or BaWü, is a German state () in Southwest Germany, east of the Rhine, which forms the southern part of Germany's western border with France. With more than 11.07 million inhabitants across a ...

together with ''Württemberg-Baden'' of the American Zone.

The French Zone of Occupation included the Saargebiet, which was disentangled from it on 16 February 1946. By 18 December 1946 customs controls were established between the Saar area and Allied-occupied Germany. The French zone ceded further areas adjacent to the Saar (in mid-1946, early 1947, and early 1949). Included in the French zone was the town of Büsingen am Hochrhein, a German exclave separated from the rest of the country by a narrow strip of neutral Swiss

Swiss may refer to:

* the adjectival form of Switzerland

* Swiss people

Places

* Swiss, Missouri

*Swiss, North Carolina

* Swiss, West Virginia

* Swiss, Wisconsin

Other uses

* Swiss-system tournament, in various games and sports

*Swiss Internati ...

territory. The Swiss government agreed to allow limited numbers of French troops to pass through its territory in order to maintain law and order in Büsingen.

At the end of October 1946, the French Zone had a population of:

* Rheinland Pfalz 2.7 million

* Baden (South Baden) 1.2 million

* Württemberg-Hohenzollern 1.05 million

(The Saar Protectorate had a further 0.8 million.)

Luxembourg zone

From November 1945, Luxembourg was allocated a zone within the French sector. The Luxembourg 2nd Infantry Battalion was garrisoned inBitburg

Bitburg (; french: Bitbourg; lb, Béibreg) is a city in Germany, in the state of Rhineland-Palatinate approximately 25 km (16 mi.) northwest of Trier and 50 km (31 mi.) northeast of Luxembourg city. The American Spangdahlem ...

and the 1st Battalion was sent to Saarburg

Saarburg (, ) is a city of the Trier-Saarburg district, in the state of Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany, on the banks of the river Saar in the hilly country a few kilometers upstream from the Saar's junction with the Moselle. Now known as a tourist ...

. The final Luxembourg forces in Germany, in Bitburg, left in 1955.

Soviet Zone

The Soviet occupation zone incorporated

The Soviet occupation zone incorporated Thuringia

Thuringia (; german: Thüringen ), officially the Free State of Thuringia ( ), is a state of central Germany, covering , the sixth smallest of the sixteen German states. It has a population of about 2.1 million.

Erfurt is the capital and lar ...

, Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt

Saxony-Anhalt (german: Sachsen-Anhalt ; nds, Sassen-Anholt) is a state of Germany, bordering the states of Brandenburg, Saxony, Thuringia and Lower Saxony. It covers an area of

and has a population of 2.18 million inhabitants, making it the ...

, Brandenburg and Mecklenburg-Vorpommern

Mecklenburg-Vorpommern (MV; ; nds, Mäkelborg-Vörpommern), also known by its anglicized name Mecklenburg–Western Pomerania, is a state in the north-east of Germany. Of the country's sixteen states, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern ranks 14th in pop ...

. The Soviet Military Administration in Germany

The Soviet Military Administration in Germany (russian: Советская военная администрация в Германии, СВАГ; ''Sovyetskaya Voyennaya Administratsiya v Germanii'', SVAG; german: Sowjetische Militäradministrat ...

was headquartered in Berlin-Karlshorst

Karlshorst (, ; ; literally meaning ''Karl's nest'') is a locality in the borough of Lichtenberg in Berlin. Located there are a harness racing track and the Hochschule für Technik und Wirtschaft Berlin (''HTW''), the largest University of Applied ...

.

At the end of October 1946, the Soviet Zone had a population of:

* Saxony: 5.5 million

* Saxony-Anhalt 4.1 million

* Thuringia 2.9 million

* Brandenburg 2.5 million

* Mecklenburg 2.1 million

Berlin

While located wholly within the Soviet zone, because of its symbolic importance as the nation's capital and seat of the former Nazi government, the city of Berlin was jointly occupied by the Allied powers and subdivided into four sectors. All four occupying powers were entitled to privileges throughout Berlin that were not extended to the rest of Germany – this included the Soviet sector of Berlin, which was legally separate from the rest of the Soviet zone. At the end of October 1946, Berlin had a population of: * Western sectors 2.0 million * Soviet sector 1.1 millionOther German territory

In 1945 Germany east of theOder–Neisse line

The Oder–Neisse line (german: Oder-Neiße-Grenze, pl, granica na Odrze i Nysie Łużyckiej) is the basis of most of the international border between Germany and Poland from 1990. It runs mainly along the Oder and Lusatian Neisse rivers ...

(Farther Pomerania

Farther Pomerania, Hinder Pomerania, Rear Pomerania or Eastern Pomerania (german: Hinterpommern, Ostpommern), is the part of Pomerania which comprised the eastern part of the Duchy and later Province of Pomerania. It stretched roughly from the ...

, the New March

The Neumark (), also known as the New March ( pl, Nowa Marchia) or as East Brandenburg (), was a region of the Margraviate of Brandenburg and its successors located east of the Oder River in territory which became part of Poland in 1945.

Call ...

, Silesia

Silesia (, also , ) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at around 8,000,000. Silesia is spli ...

and southern East Prussia

East Prussia ; german: Ostpreißen, label= Low Prussian; pl, Prusy Wschodnie; lt, Rytų Prūsija was a province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1773 to 1829 and again from 1878 (with the Kingdom itself being part of the German Empire from 1 ...

) was assigned to Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, , is a country in Central Europe. Poland is divided into Voivodeships of Poland, sixteen voivodeships and is the fifth most populous member state of the European Union (EU), with over 38 mill ...

by the Potsdam Conference to be "temporarily administered" pending the Final Peace Treaty on Germany; eventually (under the September 1990 Peace Treaty) the northern portion of East Prussia became the Kaliningrad Oblast

Kaliningrad Oblast (russian: Калинингра́дская о́бласть, translit=Kaliningradskaya oblast') is the westernmost federal subject of Russia. It is a semi-exclave situated on the Baltic Sea. The largest city and admini ...

within the Soviet Union. A small area west of the Oder, near Szczecin

Szczecin (, , german: Stettin ; sv, Stettin ; Latin: ''Sedinum'' or ''Stetinum'') is the capital and largest city of the West Pomeranian Voivodeship in northwestern Poland. Located near the Baltic Sea and the German border, it is a major s ...

, also fell to Poland. Most German citizens residing in these areas were subsequently expropriated and expelled. Returning refugees, who had fled from war hostilities, were denied return.

The Saargebiet, an important area of Germany because of its large deposits of coal, was turned into the Saar protectorate

The Saar Protectorate (german: Saarprotektorat ; french: Protectorat de la Sarre) officially Saarland (french: Sarre) was a French protectorate separated from Germany; which was later opposed by the Soviet Union, one side occupying Germany like ...

. The Saar was disengaged from the French zone on 16 February 1946. In the speech Restatement of Policy on Germany on 6 September 1946, the U.S. Secretary of State James F. Byrnes stated the U.S.' motive in detaching the Saar from Germany as "The United States does not feel that it can deny to France, which has been invaded three times by Germany in 70 years, its claim to the Saar territory."

By 18 December 1946 customs controls were established between the Saar and Allied-occupied Germany. Most German citizens residing in the Saar area were allowed to stay and keep their property. Returning refugees, who had fled from war hostilities, were allowed to return; in particular, refugees who had fled the Nazi dictatorship were invited and welcomed to return to the Saar.

The protectorate was a state nominally independent of Germany and France, but with its economy integrated into that of France. The Saar territory was enlarged at the expense of the French zone in mid-1946, early 1947 (when 61 municipalities were returned to the French zone), and early 1949. On 15 November 1947 the French currency became legal tender in the Saar Protectorate, followed by the full integration of the Saar into the French economy (customs union as of 23 March 1948). In July the Saar population was stripped of its German citizenship and became of Sarrois nationality.

Population

In October 1946, the population of the various zones and sectors was as follows:Governance and the emergence of two German states

The original Allied plan to govern Germany as a single unit through theAllied Control Council

The Allied Control Council or Allied Control Authority (german: Alliierter Kontrollrat) and also referred to as the Four Powers (), was the governing body of the Allied Occupation Zones in Germany and Allied-occupied Austria after the end of ...

broke down in 1946–1947 due to growing tensions between the Allies, with Britain and the US wishing cooperation, France obstructing any collaboration in order to partition Germany into many independent states, and the Soviet Union unilaterally implementing from early on elements of a Marxist political-economic system (enforced redistribution of land, nationalisation of businesses). Another dispute was the absorption of post-war expellees. While the UK, the US and the Soviet Union had agreed to accept, house and feed about six million expelled German citizens from former eastern Germany and four million expelled and denaturalised Czechoslovaks, Poles, Hungarians and Yugoslavs of German ethnicity in their zones, France generally had not agreed to the expulsions approved by the Potsdam agreement (a decision made without input from France). Therefore, France strictly refused to absorb war refugees who were denied return to their homes in seized eastern German territories or destitute post-war expellees who had been expropriated there, into the French zone, let alone into the separated Saar protectorate.Cf. the report of the Central State Archive of Rhineland-Palatinate on the first expellees arriving in that state in 1950 from other German states in the former British or American zone: "Beyond that he fact, that until France took control of her zone west only few eastern war refugees had made it into her zonealready since summer 1945 France refused to absorb expellee transports in her zone. France, who had not participated in the Potsdam Conference, where the expulsions of eastern Germans had been decided, and who therefore did not feel responsible for the ramifications, feared an unbearable burden for its zone anyway strongly smarting from the consequences of the war." N.N."Vor 50 Jahren: Der 15. April 1950. Vertriebene finden eine neue Heimat in Rheinland-Pfalz"

, on

Rheinland-Pfalz Landesarchivverwaltung

retrieved on 4 March 2013. However, the native population, returning after Nazi-imposed removals (e.g., political and Jewish refugees) and war-related relocations (e.g., evacuation from air raids), were allowed to return home in the areas under French control. The other Allies complained that they had to shoulder the burden to feed, house and clothe the expellees who had to leave their belongings behind. In practice, each of the four occupying powers wielded government authority in their respective zones and carried out different policies toward the population and local and state governments there. A uniform administration of the western zones evolved, known first as the

Bizone

The Bizone () or Bizonia was the combination of the American and the British occupation zones on 1 January 1947 during the occupation of Germany after World War II. With the addition of the French occupation zone on 1 August 1948J. Robert W ...

(the American and British zones merged as of 1 January 1947) and later the Trizone (after inclusion of the French zone). The complete breakdown of east–west allied cooperation and joint administration in Germany became clear with the Soviet imposition of the Berlin Blockade

The Berlin Blockade (24 June 1948 – 12 May 1949) was one of the first major international crises of the Cold War. During the multinational occupation of post–World War II Germany, the Soviet Union blocked the Western Allies' railway, ro ...

that was enforced from June 1948 to May 1949. The three western zones were merged to form the Federal Republic of Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG),, is a country in Central Europe. It is the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany lies between the Baltic and North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south ...

in May 1949, and the Soviets followed suit in October 1949 with the establishment of the German Democratic Republic

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ger ...

(GDR).

In the west, the occupation continued until 5 May 1955, when the General Treaty

A general officer is an officer of high rank in the armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colonel."general, adj. and n.". OED O ...

(german: link=no, Deutschlandvertrag) entered into force. However, upon the creation of the Federal Republic in May 1949, the military governors were replaced by civilian high commissioners, whose powers lay somewhere between those of a governor and those of an ambassador. When the ''Deutschlandvertrag'' became law, the occupation ended, the western occupation zones ceased to exist, and the high commissioners were replaced by normal ambassadors. West Germany was also allowed to build a military, and the Bundeswehr

The ''Bundeswehr'' (, meaning literally: ''Federal Defence'') is the armed forces of the Federal Republic of Germany. The ''Bundeswehr'' is divided into a military part (armed forces or ''Streitkräfte'') and a civil part, the military part con ...

, or Federal Defense Force, was established on 12 November 1955.

A similar situation occurred in East Germany. The GDR was founded on 7 October 1949. On 10 October the Soviet Military Administration in Germany

The Soviet Military Administration in Germany (russian: Советская военная администрация в Германии, СВАГ; ''Sovyetskaya Voyennaya Administratsiya v Germanii'', SVAG; german: Sowjetische Militäradministrat ...

was replaced by the Soviet Control Commission, although limited sovereignty was not granted to the GDR government until 11 November 1949. After the death of Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secreta ...

in March 1953, the Soviet Control Commission was replaced with the office of the Soviet High Commissioner on 28 May 1953. This office was abolished (and replaced by an ambassador) and (general) sovereignty was granted to the GDR, when the Soviet Union concluded a state treaty ''(Staatsvertrag)'' with the GDR on 20 September 1955. On 1 March 1956, the GDR established a military, the National People's Army

The National People's Army (german: Nationale Volksarmee, ; NVA ) were the armed forces of the German Democratic Republic (GDR) from 1956 to 1990.

The NVA was organized into four branches: the (Ground Forces), the (Navy), the (Air Force) an ...

(NVA).

Despite the grants of general sovereignty to both German states in 1955, full and unrestricted sovereignty under international law was not enjoyed by any German government until after the reunification of Germany

German reunification (german: link=no, Deutsche Wiedervereinigung) was the process of re-establishing Germany as a united and fully sovereign state, which took place between 2 May 1989 and 15 March 1991. The day of 3 October 1990 when the Ge ...

in October 1990. Though West Germany was effectively independent, the western Allies maintained limited legal jurisdiction over 'Germany as a whole' in respect of West Germany and Berlin. At the same time, East Germany progressed from being a satellite state

A satellite state or dependent state is a country that is formally independent in the world, but under heavy political, economic, and military influence or control from another country. The term was coined by analogy to planetary objects orbitin ...

of the Soviet Union to increasing independence of action; while still deferring in matters of security to Soviet authority. The provisions of the Treaty on the Final Settlement with Respect to Germany

The Treaty on the Final Settlement with Respect to Germany (german: Vertrag über die abschließende Regelung in Bezug auf Deutschland;

rus, Договор об окончательном урегулировании в отношении Ге� ...

, also known as the "Two-plus-Four Treaty", granting full sovereign powers to Germany did not become law until 15 March 1991, after all of the participating governments had ratified the treaty. As envisaged by the Treaty, the last occupation troops departed from Germany when the Russian presence was terminated in 1994, although the Belgian Forces in Germany stayed in German territory until the end of 2005.

A 1956 plebiscite ended the French administration of the Saar protectorate, and it joined the Federal Republic as ''Saarland

The Saarland (, ; french: Sarre ) is a state of Germany in the south west of the country. With an area of and population of 990,509 in 2018, it is the smallest German state in area apart from the city-states of Berlin, Bremen, and Hamburg, and t ...

'' on 1 January 1957, becoming its tenth state.

The city of Berlin was not part of either state and continued to be under Allied occupation until the reunification of Germany in October 1990. For administrative purposes, the three western sectors of Berlin were merged into the entity of West Berlin

West Berlin (german: Berlin (West) or , ) was a political enclave which comprised the western part of Berlin during the years of the Cold War. Although West Berlin was de jure not part of West Germany, lacked any sovereignty, and was under m ...

. The Soviet sector became known as East Berlin

East Berlin was the ''de facto'' capital city of East Germany from 1949 to 1990. Formally, it was the Soviet sector of Berlin, established in 1945. The American, British, and French sectors were known as West Berlin. From 13 August 1961 u ...

and while not recognised by the Western powers as a part of East Germany, the GDR declared it its capital ''(Hauptstadt der DDR)''.

Occupation policy

At the end of the war, General Eisenhower issued a non-

At the end of the war, General Eisenhower issued a non-fraternization

Fraternization (from Latin ''frater'', brother) is "to become brothers" by conducting social relations with people who are actually unrelated and/or of a different class (especially those with whom one works) as if they were siblings, family mem ...

policy to troops under his command in occupied Germany. This policy was relaxed in stages. By June 1945 the prohibition on speaking with German children was made less strict. In July it became possible to speak to German adults in certain circumstances. In September the policy was completely dropped in Austria and Germany.

Nevertheless, due to the large numbers of Disarmed Enemy Forces

Disarmed Enemy Forces (DEF, less commonly, Surrendered Enemy Forces) was a US designation for soldiers who surrendered to an adversary after hostilities ended, and for those POWs who had already surrendered and were held in camps in occupied Ger ...

being held in '' Rheinwiesenlagers'' throughout western Germany, the Americans and the British – not the Soviets – used armed units of ''Feldgendarmerie

The ''Feldgendarmerie'' (, "field gendarmerie") were a type of military police units of the armies of the Kingdom of Saxony (from 1810), the German Empire and Nazi Germany until the conclusion of World War II in Europe.

Early history

From 1810 ...

'' to maintain control and discipline in the camps. In June 1946, these German military police units became the last ''Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the ''Heer'' (army), the ''Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmacht''" replaced the previou ...

'' troops to surrender their arms to the western powers.

By December 1945, over 100,000 German civilians were interned as security threats and for possible trial and sentencing as members of criminal organisations.

The food situation in occupied Germany was initially very dire. By the spring of 1946 the official ration in the American zone was no more than per day, with some areas probably receiving as little as per day. In the British zone the food situation was dire, as found during a visit by the British (and Jewish) publisher Victor Gollancz

Sir Victor Gollancz (; 9 April 1893 – 8 February 1967) was a British publisher and humanitarian.

Gollancz was known as a supporter of left-wing causes. His loyalties shifted between liberalism and communism, but he defined himself as a Chris ...

in October and November 1946. In Düsseldorf

Düsseldorf ( , , ; often in English sources; Low Franconian and Ripuarian: ''Düsseldörp'' ; archaic nl, Dusseldorp ) is the capital city of North Rhine-Westphalia, the most populous state of Germany. It is the second-largest city in ...

the normal 28-day allocation should have been including of bread, but as there was limited grain the bread ration was only . However, as there was only sufficient bread for about 50% of this "called up" ration, the total deficiency was about 50%, not 15% as stated in a ministerial reply in the British Parliament on 11 December. So only about would have been supplied, and he said the German winter ration would be as the recent increase was "largely mythical". His book includes photos taken on the visit and critical letters and newspaper articles by him published in several British newspapers; ''The Times, the Daily Herald, the Manchester Guardian'', etc.

Some occupation soldiers took advantage of the desperate food situation by exploiting their ample supply of food and cigarettes (the currency of the black market) to get to the local German girls as what became known as ''frau bait'' (''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'', 25 June 1945). Some soldiers still felt the girls were the enemy, but used them for sex nevertheless.

The often destitute mothers of the resulting children usually received no child support

Child support (or child maintenance) is an ongoing, periodic payment made by a parent for the financial benefit of a child (or parent, caregiver, guardian) following the end of a marriage or other similar relationship. Child maintenance is paid d ...

. In the earliest stages of the occupation, U.S. soldiers were not allowed to pay maintenance for a child they admitted having fathered, since to do so was considered "aiding the enemy". Marriages between white U.S. soldiers and Austrian women were not permitted until January 1946, and with German women until December 1946.

The children of African-American soldiers, commonly called ''Negermischlinge'' ("Negro half-breeds"), comprising about three percent of the total number of children fathered by GIs, were particularly disadvantaged because of their inability to conceal the foreign identity of their father. For many white U.S. soldiers of this era, miscegenation

Miscegenation ( ) is the interbreeding of people who are considered to be members of different Race (human categorization), races. The word, now usually considered pejorative, is derived from a combination of the Latin terms ''miscere'' ("to m ...

even with an "enemy" white population was regarded as an intolerable outrage. African-American soldiers were therefore reluctant to admit to fathering such children since this would invite reprisals and even accusations of rape, a crime which was much more aggressively prosecuted by military authorities against African-Americans compared with Caucasian soldiers, much more likely to result in a conviction by court-martial (in part because a German woman was both less likely to acknowledge consensual sexual relations with an African-American and more likely to be believed if she alleged rape against an African-American) and which carried a potential death sentence. Even in the rare cases where an African-American soldier was willing to take responsibility for fathering a child, until 1948 the U.S. Army prohibited interracial marriage

Interracial marriage is a marriage involving spouses who belong to different races or racialized ethnicities.

In the past, such marriages were outlawed in the United States, Nazi Germany and apartheid-era South Africa as miscegenation. In ...

s. The mothers of the children would often face particularly harsh ostracism.

Between 1950 and 1955, the Allied High Commission for Germany prohibited "proceedings to establish paternity or liability for maintenance of children." Even after the lifting of the ban West German courts had little power over American soldiers.

In general, the British authorities were less strict than the Americans about fraternisation, whereas the French and Soviet authorities were more strict.

While Allied servicemen were ordered to obey local laws while in Germany, soldiers could not be prosecuted by German courts for crimes committed against German citizens except as authorised by the occupation authorities. Invariably, when a soldier was accused of criminal behaviour the occupation authorities preferred to handle the matter within the military justice system. This sometimes led to harsher punishments than would have been available under German law – in particular, U.S. servicemen could be executed if court-martialed and convicted of rape. See United States v. Private First Class John A. Bennett, 7 C.M.A. 97, 21 C.M.R. 223 (1956).

Insurgency

The last Allied war advances into Germany and Allied occupation plans were affected by rumors of the NaziWerwolf

''Werwolf'' (, German for "werewolf") was a Nazi plan which began development in 1944, to create a resistance force which would operate behind enemy lines as the Allies advanced through Germany, in parallel with the ''Wehrmacht'' fighting in f ...

plan for insurgency, and successful Nazi deception about plans to withdraw forces to the '' Alpenfestung'' redoubt. This base was to be used to conduct guerrilla warfare, but the rumours turned out to be false. No Allied deaths can be reliably attributed to any Nazi insurgency.

Expulsion policy

ThePotsdam conference

The Potsdam Conference (german: Potsdamer Konferenz) was held at Potsdam in the Soviet occupation zone from July 17 to August 2, 1945, to allow the three leading Allies to plan the postwar peace, while avoiding the mistakes of the Paris Pe ...

, where the victorious Allies drew up plans for the future of Germany, noted in article XIII of the Potsdam Agreement

The Potsdam Agreement (german: Potsdamer Abkommen) was the agreement between three of the Allies of World War II: the United Kingdom, the United States, and the Soviet Union on 1 August 1945. A product of the Potsdam Conference, it concerned t ...

on 1 August 1945 that "the transfer to Germany of German populations...in Poland, Czechoslovakia and Hungary will have to be undertaken"; "wild expulsion" was already going on.

Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croa ...

, which had been allied with Germany and whose population was opposed to an expulsion of the German minority, tried to resist the transfer. Hungary had to yield to the pressure exerted mainly by the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

and by the Allied Control Council

The Allied Control Council or Allied Control Authority (german: Alliierter Kontrollrat) and also referred to as the Four Powers (), was the governing body of the Allied Occupation Zones in Germany and Allied-occupied Austria after the end of ...

.Steffen Prauser and Arfon Rees, European University Institute, Florence, Department of history and civilization

former eastern territories of Germany

The former eastern territories of Germany (german: Ehemalige deutsche Ostgebiete) refer in present-day Germany to those territories east of the current eastern border of Germany i.e. Oder–Neisse line which historically had been considered Ger ...

, Poland, Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

, Hungary and elsewhere to the occupation zones of the UK, US, and USSR, which agreed in the Potsdam Agreement to absorb the post-war expellees into their zones. Many remained in refugee camps for a long time. Some Germans remained in the Soviet Union and were used for forced labour for a period of years.

France was not invited to the Potsdam Conference. As a result, it chose to adopt some decisions of the Potsdam Agreements and to dismiss others. France maintained the position that it did not approve post-war expulsions and that therefore it was not responsible to accommodate and nourish the destitute expellees in its zone. While the few war-related refugees who had reached the area to become the French zone before July 1945 were taken care of, the French military government for Germany refused to absorb post-war expellees deported from the East into its zone. In December 1946, the French military government for Germany absorbed into its zone German refugees from Denmark, where 250,000 Germans had found a refuge from the Soviets by sea vessels between February and May 1945. These clearly were war-related refugees from the eastern parts of Germany however, and not post-war expellees.

Military governors and commissioners

See also

* Allied-occupied Austria *German-occupied Europe

German-occupied Europe refers to the sovereign countries of Europe which were wholly or partly occupied and civil-occupied (including puppet governments) by the military forces and the government of Nazi Germany at various times between 19 ...

* History of Germany since 1945

* Interzonal traffic

* US Occupation of Japan

Notes

References

Further reading

* Bark, Dennis L., and David R. Gress. ''A History of West Germany Vol 1: From Shadow to Substance, 1945–1963'' (1992) * Bessel, Richard. ''Germany 1945: from war to peace'' (Simon and Schuster, 2012) * Campion, Corey. "Remembering the" Forgotten Zone": Recasting the Image of the Post-1945 French Occupation of Germany." ''French Politics, Culture & Society'' 37.3 (2019): 79-94. * Erlichman, Camilo, and Knowles, Christopher (eds.)Transforming Occupation in the Western Zones of Germany: Politics, Everyday Life and Social Interactions, 1945-55

(Bloomsbury, 2018). * Golay, John Ford. ''The Founding of the Federal Republic of Germany'' (University of Chicago Press, 1958) * Jarausch, Konrad H.''After Hitler: Recivilizing Germans, 1945–1995'' (2008) * Junker, Detlef, ed. ''The United States and Germany in the Era of the Cold War'' (2 vol 2004), 150 short essays by scholars covering 1945–199

excerpt and text search vol 1

* Knowles, Christopher. "The British Occupation of Germany, 1945–49: A Case Study in Post-Conflict Reconstruction." ''The RUSI Journal'' (2013) 158#6 pp: 84–91. * Knowles, Christopher. Winning the Peace: the British in Occupied Germany, 1945–1948. (PhD Dissertation King's College London, 2014)

online

later published as ''Winning the Peace: The British in Occupied Germany, 1945-1948'', 2017,

Bloomsbury Academic

Bloomsbury Publishing plc is a British worldwide publishing house of fiction and non-fiction. It is a constituent of the FTSE SmallCap Index. Bloomsbury's head office is located in Bloomsbury, an area of the London Borough of Camden. It has a ...

* Main, Steven J. "The Soviet Occupation of Germany. Hunger, Mass Violence and the Struggle for Peace, 1945–1947." ''Europe-Asia Studies'' (2014) 66#8 pp: 1380–1382.

* Phillips, David. ''Educating the Germans: People and Policy in the British Zone of Germany, 1945-1949'' (2018) 392 pp.online review

* Schwarz, Hans-Peter. ''Konrad Adenauer: A German Politician and Statesman in a Period of War, Revolution and Reconstruction'' (2 vol 1995

full text vol 1

* Taylor, Frederick. ''Exorcising Hitler: the occupation and denazification of Germany'' (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2011) * Weber, Jurgen. ''Germany, 1945–1990'' (Central European University Press, 2004

online edition

Primary sources and historiography

* * Beate Ruhm Von Oppen, ed. ''Documents on Germany under Occupation, 1945–1954'' (Oxford University Press, 1955online

* Clay, Lucius D. ''The papers of General Lucius D. Clay: Germany, 1945–1949'' (2 vol. 1974) * Miller, Paul D. "A bibliographic essay on the Allied occupation and reconstruction of West Germany, 1945–1955." ''Small Wars & Insurgencies'' (2013) 24#4 pp: 751–759.

External links

* *The Struggle for Germany and the Origins of the Cold War

by Melvyn P. Leffler {{DEFAULTSORT:Allied-Occupied Germany British military occupations Dwight D. Eisenhower France–Germany relations French military occupations Germany–Soviet Union relations Germany–United Kingdom relations Germany–United States relations States and territories established in 1945

Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG),, is a country in Central Europe. It is the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany lies between the Baltic and North Sea to the north and the Alps to the sou ...

States and territories disestablished in 1949