Notes from Underground on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

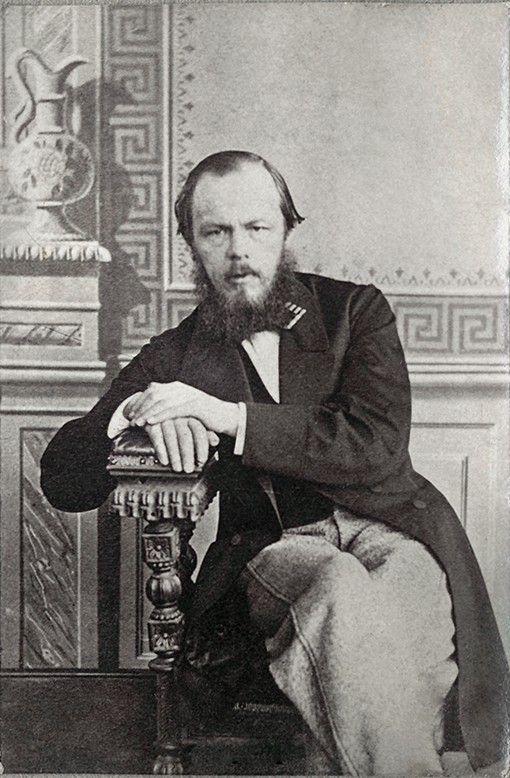

''Notes from Underground'' ( pre-reform Russian: ; post-reform Russian: ; also translated as ''Notes from the Underground'' or ''Letters from the Underworld'') is a novella by Fyodor Dostoevsky, first published in the journal ''Epoch'' in 1864. It is a first-person narrative in the form of a " confession": the work was originally announced by Dostoevsky in ''Epoch'' under the title "A Confession".

The novella presents itself as an excerpt from the memoirs of a bitter, isolated, unnamed narrator (generally referred to by critics as the Underground Man), who is a retired civil servant living in St. Petersburg. Although the first part of the novella has the form of a monologue, the narrator's form of address to his reader is acutely ''dialogized''. According to Mikhail Bakhtin, in the Underground Man's confession "there is literally not a single monologically firm, undissociated word". The Underground Man's every word anticipates the words of an other, with whom he enters into an obsessive internal polemic.

The Underground Man attacks contemporary Russian philosophy, especially Nikolay Chernyshevsky's ''

The narration by the Underground Man is laden with ideological allusions and complex conversations regarding the political climate of the period. Using his fiction as a weapon of

The narration by the Underground Man is laden with ideological allusions and complex conversations regarding the political climate of the period. Using his fiction as a weapon of

Academic journal article on ''Notes from Underground

', Conference, Autumn 1998.

Full text of ''Notes from Underground'' in the original Russian

EDSITEment's Launchpad Dostoevsky's ''Notes from Underground''

{{DEFAULTSORT:Notes From Underground 1864 Russian novels Novellas by Fyodor Dostoevsky Existentialist novels Philosophy books Novels set in Saint Petersburg Novels about Russian prostitution Fiction with unreliable narrators Russian novels adapted into films

What Is to Be Done?

''What Is to Be Done? Burning Questions of Our Movement'' is a political pamphlet written by Russian revolutionary Vladimir Lenin (credited as N. Lenin) in 1901 and published in 1902. Lenin said that the article represented "a skeleton plan ...

'' More generally, the work can be viewed as an attack on and rebellion against ''determinism

Determinism is a philosophical view, where all events are determined completely by previously existing causes. Deterministic theories throughout the history of philosophy have developed from diverse and sometimes overlapping motives and cons ...

'': the idea that everything, including the human personality and will, can be reduced to the laws of nature, science and mathematics.

Plot summary

The novella is divided into two parts. The title of the first part—"Underground"—is itself given a footnoted introduction by Dostoevsky in which the character of the 'author' of the Notes and the nature of the 'excerpts' are discussed.Part 1: "Underground"

The first part of ''Notes from Underground'' has eleven sections: * Section I propounds a number of riddles whose meanings are further developed as the narration continues. * Sections 2, 3, & 4 deal with suffering and the irrational pleasure of suffering. * Sections 5 & 6 discuss the moral and intellectual fluctuation that the narrator feels along with his conscious insecurities regarding "inertia"—inaction. * Sections 7, 8, & 9 cover theories of reason and logic, closing with the last two sections as a summary and transition into Part 2. The narrator observes that utopian society removes suffering and pain, but man desires both things and needs them in order to be happy. He argues that removing pain and suffering in society takes away a man's freedom. He says that the cruelty of society makes human beings moan about pain only to spread their suffering to others. Unlike most people, who typically act out of revenge because they believe justice is the end, the Underground Man is conscious of his problems and feels the desire for revenge, but he does not find it virtuous; the incongruity leads to spite towards the act itself with its concomitant circumstances. He feels that others like him exist, but he continuously concentrates on his spitefulness instead of on actions that would help him avoid the problems that torment him. The main issue for the Underground Man is that he has reached a point of ennui and inactivity. He even admits that he would rather be inactive out of laziness. The first part also gives a harsh criticism ofdeterminism

Determinism is a philosophical view, where all events are determined completely by previously existing causes. Deterministic theories throughout the history of philosophy have developed from diverse and sometimes overlapping motives and cons ...

, as well as of intellectual attempts at dictating human action and behavior by logic, which the Underground Man discusses in terms of the simple math problem: ''two times two makes four'' ( cf. necessitarianism). He argues that despite humanity's attempt to create a utopia where everyone lives in harmony (symbolized by The Crystal Palace

The Crystal Palace was a cast iron and plate glass structure, originally built in Hyde Park, London, Hyde Park, London, to house the Great Exhibition of 1851. The exhibition took place from 1 May to 15 October 1851, and more than 14,000 exhibit ...

in Nikolai Chernyshevsky's ''What Is to Be Done?

''What Is to Be Done? Burning Questions of Our Movement'' is a political pamphlet written by Russian revolutionary Vladimir Lenin (credited as N. Lenin) in 1901 and published in 1902. Lenin said that the article represented "a skeleton plan ...

''), one cannot avoid the simple fact that anyone, at any time, can decide to act in a way that might not be considered to be in their own self-interest; some will do so simply to validate their existence and to protest and confirm that they exist as individuals. The Underground Man ridicules the type of enlightened self-interest that Chernyshevsky proposes as the foundation of Utopian society. The idea of cultural and legislative systems relying on this rational egoism is what the protagonist despises. The Underground Man embraces this ideal in praxis

Praxis may refer to:

Philosophy and religion

* Praxis (process), the process by which a theory, lesson, or skill is enacted, practised, embodied, or realised

* Praxis model, a way of doing theology

* Praxis (Byzantine Rite), the practice of fai ...

, and seems to blame it for his current state of unhappiness.

Part 2: "Apropos of the Wet Snow"

The title of Part 2 is an allusion to the critic Pavel Annenkov's observation that "damp showers and wet snow" were indispensable to writers of the Natural School in Petersburg. Following the title there is an epigraph containing the opening lines from Nekrasov's poem "When from the darkness of delusion..." about a woman driven to prostitution by poverty. The quotation is interrupted by an ellipsis and the words "Etc., etc., etc." Part 2 consists of ten sections covering some events from the narrator's life. While he continues in his self-conscious, polemical style, the themes of his confession are now developed anecdotally. The first section tells of the Underground Man's obsession with an officer who once insulted him in a pub. This officer frequently passes him by on the street, seemingly without noticing his existence. He sees the officer on the street and thinks of ways to take revenge, eventually borrowing money to buy an expensive overcoat and intentionally bumping into the officer to assert his equality. To the Underground Man's surprise, however, the officer does not seem to notice that it even happened. Sections II to V focus on a going-away dinner party with some old school friends to bid farewell to one of these friends—Zverkov—who is being transferred out of the city. The Underground Man hated them when he was younger, but after a random visit to Simonov's, he decides to meet them at the appointed location. They fail to tell him that the time has been changed to six instead of five, so he arrives early. He gets into an argument with the four of them after a short time, declaring to all his hatred of society and using them as the symbol of it. At the end, they go off without him to a secret brothel, and, in his rage, the underground man follows them there to confront Zverkov once and for all, regardless if he is beaten or not. He arrives at the brothel to find Zverkov and the others already retired with prostitutes to other rooms. He then encounters Liza, a young prostitute. The remaining sections deal with his encounter with Liza and its repercussions. The story cuts to Liza and the Underground Man lying silently in the dark together. The Underground Man confronts Liza with an image of her future, by which she is unmoved at first, but after challenging her individual utopian dreams (similar to his ridicule of the Crystal Palace in Part 1), she eventually realizes the plight of her position and how she will slowly become useless and will descend more and more, until she is no longer wanted by anyone. The thought of dying such a terribly disgraceful death brings her to realize her position, and she then finds herself enthralled by the Underground Man's seemingly poignant grasp of the destructive nature of society. He gives her his address and leaves. He is subsequently overcome by the fear of her actually arriving at his dilapidated apartment after appearing such a "hero" to her and, in the middle of an argument with his servant, she arrives. He then curses her and takes back everything he said to her, saying he was, in fact, laughing at her and reiterates the truth of her miserable position. Near the end of his painful rage he wells up in tears after saying that he was only seeking to have power over her and a desire to humiliate her. He begins to criticize himself and states that he is in fact horrified by his own poverty and embarrassed by his situation. Liza realizes how pitiful he is and tenderly embraces him. The Underground Man cries out "They—they won't let me—I—I can't be good!" After all this, he still acts terribly toward her, and, before she leaves, he stuffs a five ruble note into her hand, which she throws onto the table (it is implied that the Underground Man had sex with Liza and that the note is payment). He tries to catch her as she goes out to the street, but he cannot find her and never hears from her again. He tries to stop the pain in his heart by "fantasizing."And isn't it better, won't it be better?… Insult—after all, it's a purification; it's the most caustic, painful consciousness! Only tomorrow I would have defiled her soul and wearied her heart. But now the insult will never ever die within her, and however repulsive the filth that awaits her, the insult will elevate her, it will cleanse her…He recalls this moment as making him unhappy whenever he thinks of it, yet again proving the fact from the first section that his spite for society and his inability to act makes him no better than those he supposedly despises. The concluding sentences recall some of the themes explored in the first part, and he tells the reader directly, "I have merely carried to an extreme in my life what you have not dared to carry even halfway.” At the end of Part 2, a further editorial note is added by Dostoevsky, indicating that the 'author' couldn't help himself and kept writing, but that "it seems to us that we might as well stop here".

Themes and context

The narration by the Underground Man is laden with ideological allusions and complex conversations regarding the political climate of the period. Using his fiction as a weapon of

The narration by the Underground Man is laden with ideological allusions and complex conversations regarding the political climate of the period. Using his fiction as a weapon of ideological discourse

An ideology is a set of beliefs or philosophies attributed to a person or group of persons, especially those held for reasons that are not purely epistemic, in which "practical elements are as prominent as theoretical ones." Formerly applied prim ...

, Dostoevsky challenges the ideologies of his time, mainly nihilism and rational egoism.

In Part 2, the rant that the Underground Man directs at Liza as they sit in the dark, and her response to it, is an example of such discourse. Liza believes she can survive and rise up through the ranks of her brothel as a means of achieving her dreams of functioning successfully in society. However, as the Underground Man points out in his rant, such dreams are based on a utopian trust of not only the societal systems in place, but also humanity's ability to avoid corruption and irrationality in general. The points made in Part 1 about the Underground Man's pleasure in being rude and refusing to seek medical help are his examples of how idealised rationality is inherently flawed for not accounting for the darker and more irrational side of humanity.

The Stone Wall is one of the symbols in the novella and represents all the barriers of the laws of nature that stand against man and his freedom. Put simply, the rule that ''two plus two equals four'' angers the Underground Man because he wants the freedom to say ''two plus two equals five'', but that Stone Wall of nature's laws stands in front of him and his free will.

Political climate

In the1860s

The 1860s (pronounced "eighteen-sixties") was a decade of the Gregorian calendar that began on January 1, 1860, and ended on December 31, 1869.

The decade was noted for featuring numerous major societal shifts in the Americas. In the United St ...

, Russia was beginning to absorb the ideas and culture of Western Europe at an accelerated pace, nurturing an unstable local climate. There was especially a growth in revolutionary activity accompanying a general restructuring of tsardom where liberal reforms, enacted by an unwieldy autocracy, only induced a greater sense of tension in both politics and civil society. Many of Russia's intellectuals were engaged in a debate with the Westernizers on one hand, and the Slavophiles

Slavophilia (russian: Славянофильство) was an intellectual movement originating from the 19th century that wanted the Russian Empire to be developed on the basis of values and institutions derived from Russia's early history. Slavop ...

on the other, concerned with favoring importation of Western reforms or promoting pan-Slavic traditions to address Russia's particular social reality. Although Tsar Alexander emancipated the serfs in 1861, Russia was still very much a post-medieval, traditional peasant society.

When ''Notes from Underground'' was written, there was an intellectual ferment on discussions regarding religious philosophy and various 'enlightened' utopian ideas. The work is a challenge to, and a method of understanding, the larger implications of the ideological drive toward a utopian society. Utopianism largely pertains to a society's collective dream, but what troubles the Underground Man is this very idea of collectivism. The point the Underground Man makes is that individuals will ultimately always rebel against a collectively imposed idea of paradise; a utopian image such as The Crystal Palace will always fail because of the underlying irrationality of humanity.

Writing style

Although the novella is written in first-person narrative, the "I" is never really discovered. Thesyntax

In linguistics, syntax () is the study of how words and morphemes combine to form larger units such as phrases and sentences. Central concerns of syntax include word order, grammatical relations, hierarchical sentence structure ( constituenc ...

can at times seem "multi-layered;" the subject and the verb

A verb () is a word ( part of speech) that in syntax generally conveys an action (''bring'', ''read'', ''walk'', ''run'', ''learn''), an occurrence (''happen'', ''become''), or a state of being (''be'', ''exist'', ''stand''). In the usual descr ...

are often at the very beginning of the sentence before the object

Object may refer to:

General meanings

* Object (philosophy), a thing, being, or concept

** Object (abstract), an object which does not exist at any particular time or place

** Physical object, an identifiable collection of matter

* Goal, an ...

goes into the depths of the narrator's thoughts. The narrator repeats many of his concepts.

In chapter 11, the narrator refers to his inferiority to everyone around him and describes listening to people as like "listening through a crack under the floor." The word "underground" actually comes from a bad translation into English. A better translation would be a crawl space: a space under the floor that is not big enough for a human, but where rodents and bugs live. According to Russian folklore, it is also a place where evil spirits live.

Legacy

The challenge posed by the Underground Man towards the idea of an "enlightened" society laid the groundwork for later writing. The work has been described as "probably the most important single source of the modern dystopia." ''Notes from Underground'' has had an impact on various authors and works in the fields of philosophy, literature, and film, including: * the writings ofFriedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (; or ; 15 October 1844 – 25 August 1900) was a German philosopher, prose poet, cultural critic, philologist, and composer whose work has exerted a profound influence on contemporary philosophy. He began his ...

* '' The Metamorphosis'' (1915), a novella by Franz Kafka

Franz Kafka (3 July 1883 – 3 June 1924) was a German-speaking Bohemian novelist and short-story writer, widely regarded as one of the major figures of 20th-century literature. His work fuses elements of realism and the fantastic. It typ ...

* ''Invisible Man

''Invisible Man'' is a novel by Ralph Ellison, published by Random House in 1952. It addresses many of the social and intellectual issues faced by African Americans in the early twentieth century, including black nationalism, the relationship ...

'' (1952), by Ralph Ellison

Ralph Waldo Ellison (March 1, 1913 – April 16, 1994) was an American writer, literary critic, and scholar best known for his novel ''Invisible Man'', which won the National Book Award in 1953. He also wrote '' Shadow and Act'' (1964), a collec ...

* ''Taxi Driver

''Taxi Driver'' is a 1976 American film directed by Martin Scorsese, written by Paul Schrader, and starring Robert De Niro, Jodie Foster, Cybill Shepherd, Harvey Keitel, Peter Boyle, Leonard Harris, and Albert Brooks. Set in a decaying ...

'' (1976), directed by Martin Scorsese

Martin Charles Scorsese ( , ; born November 17, 1942) is an American film director, producer, screenwriter and actor. Scorsese emerged as one of the major figures of the New Hollywood era. He is the recipient of many major accolades, incl ...

* ''Notes from Underground'' (1995), a film adaptation of Dostoevsky's novella, directed by Gary Walkow, with Henry Czerny and Sheryl Lee in the leading roles..

* '' Yeraltı'' (2012), directed by Zeki DemirkubuzEnglish translations

Since ''Notes from Underground'' was first published in Russian, there have been a number of translations into English over the years, including: * 1913. C. J. Hogarth. ''Letters from the Underworld''. * 1918.Constance Garnett

Constance Clara Garnett (; 19 December 1861 – 17 December 1946) was an English translator of nineteenth-century Russian literature. She was the first English translator to render numerous volumes of Anton Chekhov's work into English and the ...

.

** Revised by Ralph E. Matlaw, 1960.

* 1955. David Magarshack. ''Notes from the Underground''.

* 1961. Andrew R. MacAndrew.

* 1969. Serge Shishkoff.

* 1972. Jessie Coulson.

* 1974. Mirra Ginsburg.

* 1989. Michael R. Katz.

* 1991. Jane Kentish. ''Notes from the Underground''.

* 1994. Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky

Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky are literary translators best known for their collaborative English translations of classic Russian literature. Individually, Pevear has also translated into English works from French, Italian, and Greek. The ...

.

* 2009. Ronald Wilks

* 2009. Boris Jakim.

* 2010. Kyril Zinovieff and Jenny Hughes.

* 2014. Kirsten Lodge. ''Notes from the Underground''.

References

External links

* * *Academic journal article on ''Notes from Underground

', Conference, Autumn 1998.

Full text of ''Notes from Underground'' in the original Russian

EDSITEment's Launchpad Dostoevsky's ''Notes from Underground''

{{DEFAULTSORT:Notes From Underground 1864 Russian novels Novellas by Fyodor Dostoevsky Existentialist novels Philosophy books Novels set in Saint Petersburg Novels about Russian prostitution Fiction with unreliable narrators Russian novels adapted into films