Ngarrindjeri on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Ngarrindjeri people are the traditional

The Ngarrindjeri people are the traditional

* Ian Abdulla (1947–2011), artist

*

* Ian Abdulla (1947–2011), artist

*

The Ngarrindjeri people are the traditional

The Ngarrindjeri people are the traditional Aboriginal Australian

Aboriginal Australians are the various Indigenous peoples of the Australian mainland and many of its islands, such as Tasmania, Fraser Island, Hinchinbrook Island, the Tiwi Islands, and Groote Eylandt, but excluding the Torres Strait Islands ...

people of the lower Murray River

The Murray River (in South Australia: River Murray) (Ngarrindjeri: ''Millewa'', Yorta Yorta: ''Tongala'') is a river in Southeastern Australia. It is Australia's longest river at extent. Its tributaries include five of the next six longest r ...

, eastern Fleurieu Peninsula

The Fleurieu Peninsula () is a peninsula in the Australian state of South Australia located south of the state capital of Adelaide.

History

Before British colonisation of South Australia, the western side of the peninsula was occupied by the ...

, and the Coorong

Coorong National Park is a protected area located in South Australia about south-east of Adelaide, that predominantly covers a coastal lagoon ecosystem officially known as The Coorong and the Younghusband Peninsula on the Coorong's southern si ...

of the southern-central area of the state of South Australia

South Australia (commonly abbreviated as SA) is a state in the southern central part of Australia. It covers some of the most arid parts of the country. With a total land area of , it is the fourth-largest of Australia's states and territories ...

. The term ''Ngarrindjeri'' means "belonging to men", and refers to a "tribal constellation". The Ngarrindjeri actually comprised several distinct if closely related tribal groups, including the Jarildekald, Tanganekald, Meintangk and Ramindjeri

The Ramindjeri or Raminjeri people were an Aboriginal Australian people forming part of the ''Kukabrak'' grouping now otherwise known as the Ngarrindjeri people. They were the most westerly Ngarrindjeri, living in the area around Encounter Bay an ...

, who began to form a unified cultural bloc after remnants of each separate community congregated at Raukkan, South Australia

Raukkan is an Australian Aboriginal community situated on the south-eastern shore of Lake Alexandrina in the locality of Narrung, southeast of the centre of South Australia's capital, Adelaide. Raukkan is "regarded as the home and heartland o ...

(formerly Point McLeay Mission).

A descendant of these peoples, Irene Watson, has argued that the notion of Ngarrindjeri identity is a cultural construct imposed by settler colonialists, who bundled together and conflated a variety of distinct Aboriginal cultural and kinship groups into one homogenised pattern is now known as Ngarrindjeri.

Historical designation and usage

Sources disagree as to who the Ngarrindjeri were. The missionaryGeorge Taplin

George Taplin (24 August 1831 – 24 June 1879) was a Congregationalist minister who worked in Aboriginal missions in South Australia, and gained a reputation as an anthropologist, writing on Ngarrindjeri lore and customs.

History

Taplin was bo ...

chose it, spelling the term as ''Narrinyeri'', as a generic ethnonym

An ethnonym () is a name applied to a given ethnic group. Ethnonyms can be divided into two categories: exonyms (whose name of the ethnic group has been created by another group of people) and autonyms, or endonyms (whose name is created and used ...

to designate a unified constellation several distinct tribes, and bearing the meaning of "belonging to people", as opposed to ''kringgari'' (whites). Etymologically, it is thought to be an abbreviation of ''kornarinyeri'' ("belonging to men/human beings", formed ''narr'' (linguistically plain or intelligible) and ''inyeri'', a suffix indicating belongingness. It implied that those outside the group were not quite human. Other terms were available, for example, ''Kukabrak'', but Taplin's authority popularised the other term.

Later ethnographer

Ethnography (from Greek ''ethnos'' "folk, people, nation" and ''grapho'' "I write") is a branch of anthropology and the systematic study of individual cultures. Ethnography explores cultural phenomena from the point of view of the subject o ...

s and anthropologist

An anthropologist is a person engaged in the practice of anthropology. Anthropology is the study of aspects of humans within past and present societies. Social anthropology, cultural anthropology and philosophical anthropology study the norms and ...

s have disagreed with Taplin's construction of the tribal federation of 18 ''lakinyeri'' (clan

A clan is a group of people united by actual or perceived kinship

and descent. Even if lineage details are unknown, clans may claim descent from founding member or apical ancestor. Clans, in indigenous societies, tend to be endogamous, meaning ...

s). Ian D. Clark has called it a "reinvention of tradition". Norman Tindale

Norman Barnett Tindale AO (12 October 1900 – 19 November 1993) was an Australian anthropologist, archaeologist, entomologist and ethnologist.

Life

Tindale was born in Perth, Western Australia in 1900. His family moved to Tokyo and lived ther ...

and Ronald Murray Berndt

Ronald Murray Berndt (14 July 1916 – 2 May 1990) was an Australian social anthropologist who, in 1963, became the inaugural professor of anthropology at the University of Western Australia.

He and his wife Catherine Berndt maintained a close ...

in particular were critical both of Taplin and of each other's reevaluation of the evidence. According to Tindale, a close evaluation of his material suggests that his data pertains basically to the Jarildekald/Yaralde culture, and he limited their borders to Cape Jervis

Cape Jervis is a town in the Australian state of South Australia located near the western tip of Fleurieu Peninsula on the southern end of the Main South Road approximately south of the state capital of Adelaide.

It is named after the headla ...

, whereas Berndt and his wife Catherine Berndt

Catherine Helen Berndt, ''née'' Webb (8 May 1918 – 12 May 1994), born in Auckland, was an Australian anthropologist known for her research in Australia and Papua New Guinea. She was awarded in 1950 the Percy Smith Medal from the University o ...

argued that the Ramindjeri component lived in proximity to Adelaide

Adelaide ( ) is the capital city of South Australia, the state's largest city and the fifth-most populous city in Australia. "Adelaide" may refer to either Greater Adelaide (including the Adelaide Hills) or the Adelaide city centre. The dem ...

. The Berndts argued that, despite cultural links, there was no political unity to warrant the "nation" or "confederacy".

Country

According to David Horton's map "Aboriginal Australia", the Ngarrindjeri lands lie along the Coorong coastline, from Victor Harbor on the southernFleurieu Peninsula

The Fleurieu Peninsula () is a peninsula in the Australian state of South Australia located south of the state capital of Adelaide.

History

Before British colonisation of South Australia, the western side of the peninsula was occupied by the ...

in the north, to Cape Jaffa

Cape Jaffa is a headland in the Australian state of South Australia located at the south end of Lacepede Bay on the state's south east coast about south west of the town centre of Kingston SE. The cape is described as being "a low sandy point" ...

in the south. According to the map, the lands extend inland just north of Murray Bridge, receding to a wide coastal strip west of the Murray River

The Murray River (in South Australia: River Murray) (Ngarrindjeri: ''Millewa'', Yorta Yorta: ''Tongala'') is a river in Southeastern Australia. It is Australia's longest river at extent. Its tributaries include five of the next six longest r ...

lower lakes, but extending further inland in the south to a point near the state border at Coonawarra. The lands include both of the Murray lower lakes, Lake Alexandrina and Lake Albert.

History

Pre-contact history

Archaeology, particularly in excavations conducted at Roonka Flat, which affords one of the most outstanding sites for investigating "pre–European contact Aboriginal burial populations in Australia," has revealed that the traditional territory of the Ngarrindjeri has been inhabited since the Holocene period, beginning around 8,000 B.C. down to around 1840 CE.History after contact

Whalers andsealers Sealer may refer either to a person or ship engaged in seal hunting, or to a sealant; associated terms include:

Seal hunting

* Sealer Hill, South Shetland Islands, Antarctica

* Sealers' Oven, bread oven of mud and stone built by sealers around 180 ...

had been visiting the South Australian coast since 1802 and by 1819 there was a permanent camp on Karta, Kangaroo Island

Kangaroo Island, also known as Karta Pintingga (literally 'Island of the Dead' in the language of the Kaurna people), is Australia's third-largest island, after Tasmania and Melville Island. It lies in the state of South Australia, southwest ...

. Many of these men were escaped convicts, sealers, whalers who had brought Tasmanian Aboriginal women with them but they also raided the mainland for women, particularly Ramindjeri

The Ramindjeri or Raminjeri people were an Aboriginal Australian people forming part of the ''Kukabrak'' grouping now otherwise known as the Ngarrindjeri people. They were the most westerly Ngarrindjeri, living in the area around Encounter Bay an ...

. Originally the most heavily populated area in Australia, a smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

epidemic had travelled down the River Murray before colonisation by Britain, possibly killing a majority of the Ngarrindjeri. Funeral rites and cultural practices were disrupted, family groups merged and land use became altered. Songs from the time tell of the smallpox that came out of the Southern Cross

Crux () is a constellation of the southern sky that is centred on four bright stars in a cross-shaped asterism commonly known as the Southern Cross. It lies on the southern end of the Milky Way's visible band. The name ''Crux'' is Latin for ...

in the east with a loud noise like a bright flash. In 1830 the first exploratory expedition reached the Ngarrindjeri lands and Charles Sturt

Charles Napier Sturt (28 April 1795 – 16 June 1869) was a British officer and explorer of Australia, and part of the European exploration of Australia. He led several expeditions into the interior of the continent, starting from Sydney and la ...

noted that the people were already familiar with firearms.

Numbering only 6000 at the time of colonisation in 1836 due to the epidemic, they are the only Aboriginal cultural group in Australia whose land lay within of a capital city to have survived as a distinct people with a population still living on the former mission at Raukkan (formerly Point McLeay). ''Pomberuk'' (Ngarrindjeri for crossing place), on the banks of the Murray in Murray Bridge was the most significant Ngarrindjeri site. All 18 lakinyeri (tribes) would meet there for corroboree

A corroboree is a generic word for a meeting of Australian Aboriginal peoples. It may be a sacred ceremony, a festive celebration, or of a warlike character. A word coined by the first British settlers in the Sydney area from a word in the l ...

s. Around further down the river was ''Tagalang'' (Tailem Bend

Tailem Bend (locally, "Tailem") is a rural town in South Australia, south-east of the state capital of Adelaide. It is located on the lower reaches of the River Murray, near where the river flows into Lake Alexandrina. It is linear in layout s ...

), a traditional trading camp where lakinyeri would gather to trade ochre

Ochre ( ; , ), or ocher in American English, is a natural clay earth pigment, a mixture of ferric oxide and varying amounts of clay and sand. It ranges in colour from yellow to deep orange or brown. It is also the name of the colours produced ...

, weapons and clothing. In the 1900s, Tailem Bend was assigned as a government ration depot supplying the Ngarrindjeri.

European settlement

The Ngarrindjeri were the first South Australian Aboriginal people to work with Europeans in large-scale economic operations, working as farmers, whalers and labourers. As early as 1836 it was reliably reported that Aboriginal crews were working at the whaling station atEncounter Bay

Encounter Bay is a bay in the Australian state of South Australia located on the state's south central coast about south of the state capital of Adelaide. It was named by Matthew Flinders after his encounter on 8 April 1802 with Nicolas Baud ...

, and that some boats were worked by entirely Aboriginal crews, and the Ngarrindjeri were employed in the processing of whale oil in exchange for meat, gin and tobacco, and reportedly treated as equals.

Following the colonisation of South Australia

British colonisation of South Australia describes the planning and establishment of the colony of South Australia by the British government, covering the period from 1829, when the idea was raised by the then-imprisoned Edward Gibbon Wakefield ...

and the encroachment of Europeans into Ngarrindjeri lands, Pomberuk remained until the 1940s, the last traditional campsite with the remaining Aboriginal occupants forced to leave in 1943 by the new land owners, the Hume Pipe Company, and resettled by the local council and South Australian government.

After hearing that the Aboriginal settlement was to be cleared, Ronald

Ronald is a masculine given name derived from the Old Norse ''Rögnvaldr'',#H2, Hanks; Hardcastle; Hodges (2006) p. 234; #H1, Hanks; Hodges (2003) § Ronald. or possibly from Old English ''Regenweald''. In some cases ''Ronald'' is an Anglicised ...

and his wife Catherine Berndt

Catherine Helen Berndt, ''née'' Webb (8 May 1918 – 12 May 1994), born in Auckland, was an Australian anthropologist known for her research in Australia and Papua New Guinea. She was awarded in 1950 the Percy Smith Medal from the University o ...

, who were researching Aboriginal culture in the area, approached the last Chief Protector of Aborigines

The role of Protector of Aborigines was first established in South Australia in 1836.

The role became established in other parts of Australia pursuant to a recommendation contained in the ''Report of the Parliamentary Select Committee on Abori ...

, William Penhall

William Penhall (27 October 1858 – 3 August 1882) was an English mountaineer.

Life and family

The son of Dr John Penhall MRCS LSA (born 1833 at St Pancras, Middlesex, in 1871 a general practitioner in Hastings, Sussex), Penhall was educated ...

, and obtained a verbal promise that the clearance would not proceed as long as the senior Ngarrindjeri elder, 78-year-old Albert Karloan (Karloan Ponggi), was living. Shortly after the Berndts left to return to Sydney

Sydney ( ) is the capital city of the state of New South Wales, and the most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Located on Australia's east coast, the metropolis surrounds Sydney Harbour and extends about towards the Blue Mountain ...

, Karloan was given an eviction order effective immediately. Adamant that only death would separate him from his land, Karloan travelled to Adelaide

Adelaide ( ) is the capital city of South Australia, the state's largest city and the fifth-most populous city in Australia. "Adelaide" may refer to either Greater Adelaide (including the Adelaide Hills) or the Adelaide city centre. The dem ...

to seek help, but returned to his former home in Pomberuk on 2 February 1943. He died the following morning.

Now known as the Murray Bridge Railway Precinct and Hume Reserve, the Ngarrindjeri Regional Authority seeks the renaming of Hume Reserve to Karloan Ponggi Reserve (after Albert Karloan) in honour of the old people who fought to retain the old ways. They have presented a development and management plan to preserve and develop the site as a memorial and an educational aid to reconciliation.

Hindmarsh Island bridge controversy

The Ngarrindjeri achieved a great deal of publicity in the 1990s due to their opposition to the construction of a bridge from Goolwa toHindmarsh Island

Hindmarsh Island (Ngarrindjeri: Kumerangk) is an inland river island located in the lower Murray River near the town of Goolwa, South Australia, Goolwa, South Australia.

The island is a tourist destination, which has increased in popularity si ...

, which resulted in a Royal Commission and a High Court case in 1996. The Royal Commission found that claims of "secret women's business" on the island had been fabricated. However, in a case brought by the developers seeking damages for their losses, Federal Court judge, Mr John von Doussa took issue with the findings of the Royal Commission and in rejecting the claims stated that he found Doreen Kartinyeri

Doreen Maude Kartinyeri (3 February 1935–2 December 2007) was an Ngarrindjeri elder and historian, born in the Australian state of South Australia. She played a key role in the Hindmarsh Bridge controversy and made many contributions to ...

to be a credible witness. The evidence received by the Court on this topic is significantly different to that which was before the Royal Commission. Upon the evidence before this Court I am not satisfied that the restricted women's knowledge was fabricated or that it was not part of genuine Aboriginal tradition.As a result of the Australia-wide 1995–2009 drought, water levels in Lakes Albert and Alexandrina dropped to the extent that traditional burial grounds, which had been under water, were now exposed.

Language

The first linguistic study of Ngarrindjeri dialects was conducted by the Lutheranmissionary

A missionary is a member of a Religious denomination, religious group which is sent into an area in order to promote its faith or provide services to people, such as education, literacy, social justice, health care, and economic development.Tho ...

H.A.E. Meyer in 1843. He collected 1750 words, mainly from the Ramindjeri dialect at Encounter Bay

Encounter Bay is a bay in the Australian state of South Australia located on the state's south central coast about south of the state capital of Adelaide. It was named by Matthew Flinders after his encounter on 8 April 1802 with Nicolas Baud ...

. Taplin gathered many more words from several dialects, including Yaraldi and Portawalun, from the people who congregated around the Port MacLeay mission on Lake Alexandrina, and his dictionary had 1668 English entries. Other linguistic data gleaned since has enabled the compilation of a modern Ngarrindjeri dictionary containing 3,700 items. It is now classified, together with Yaralde, as one of the five languages of the Lower Murray Areal group.

Culture

The Dreaming

Many sites of Dreaming significance are located along the River Murray. Near the confluence of the Murray River with Lake Alexandrina is ''Murungun'' (Mason's Hill), home to abunyip

The bunyip is a creature from the aboriginal mythology of southeastern Australia, said to lurk in swamps, billabongs, creeks, riverbeds, and waterholes.

Name

The origin of the word ''bunyip'' has been traced to the Wemba-Wemba or Wergaia ...

called Muldjewangk. An ancestral hero named ''Ngurunderi'' chased an enormous Murray cod named ''Pondi'' from a stream in central New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

. In fleeing, Pondi created the River Murray, and contiguous lagoons from its flailing tail. ''Kauwira'' (Mannum

Mannum is a historic town on the west bank of the Murray River in South Australia, east of Adelaide. At the 2016 census, the urban area of Mannum had a population of 2,398. Mannum is the seat of the Mid Murray Council, and is situated in the ...

) is where ''Ngurunderi'' forced ''Pondi'' to turn sharply south. The straight section of river to ''Peindjalong'' (near Tailem Bend) resulted from ''Pondi'' fleeing in fear after being speared in the tail. The twin peaks, large permanent sandhills of Mount Misery on the eastern shore of Lake Alexandrina are known as ''Lalangenggul'' or Lalanganggel (two watercraft) and represent where ''Ngurunderi'' brought his rafts ashore to make camp. ''Ngurunderi'' cut up ''Pondi'' at Raukkan, throwing the pieces into the water, where each piece became a species of fish.

While an established Dreaming existed, the various family groups each had their own variations. For example, some said ''Ngurunderi'' created the fish on the coast, other family groups believe he created them where the river enters Lake Alexandrina and some said that it was where the fresh water meets the salt. They also shared some Dreaming stories with tribes in New South Wales and Victoria.

In the late 1980s, the Dreaming stories were collected and one related to a creation story involving ''Thukabi'', a turtle. There was no mention of ''Thukabi'' in the anthropological record and this example was later used as evidence for the survival of Ngarrindjeri stories that were unknown to anthropologists in support of the secret women's business.

The bunyip

The bunyip is a creature from the aboriginal mythology of southeastern Australia, said to lurk in swamps, billabongs, creeks, riverbeds, and waterholes.

Name

The origin of the word ''bunyip'' has been traced to the Wemba-Wemba or Wergaia ...

appears in Ngarrindjeri dreaming as a water spirit called the Mulyawonk, which would get anyone who took more than their fair share of fish from the waterways, or take children if they got too close to the water. The stories conveyed practical messages to ensure long-term survival of the Ngarrindjeri, embodying care for country and its people.

Customs

The Ngarrindjeri have their own language group and, apart from groups living along the river, share no common words with neighbouring peoples. Theirpatrilineal

Patrilineality, also known as the male line, the spear side or agnatic kinship, is a common kinship system in which an individual's family membership derives from and is recorded through their father's lineage. It generally involves the inheritanc ...

culture and ritual practices were also distinct from that of the surrounding people which has been attributed by Aboriginal historian Graham Jenkin to their enmity with the Kaurna

The Kaurna people (, ; also Coorna, Kaura, Gaurna and other variations) are a group of Aboriginal people whose traditional lands include the Adelaide Plains of South Australia. They were known as the Adelaide tribe by the early settlers. Kaurn ...

to the west, who practised circumcision

Circumcision is a surgical procedure, procedure that removes the foreskin from the human penis. In the most common form of the operation, the foreskin is extended with forceps, then a circumcision device may be placed, after which the foreskin ...

and monopolised red ochre

Ochre ( ; , ), or ocher in American English, is a natural clay earth pigment, a mixture of ferric oxide and varying amounts of clay and sand. It ranges in colour from yellow to deep orange or brown. It is also the name of the colours produced ...

, the Merkani (Ngarrindjeri for "enemy") to the east, who stole Ngarrindjeri women and were reputed to be cannibals

and to the north the Ngadjuri

The Ngadjuri people are a group of Aboriginal Australian people whose traditional lands lie in the mid north of South Australia with a territory extending from Gawler in the south to Orroroo in the Flinders Ranges in the north.

Name

Their ethnon ...

who were believed to send ''mulapi'' ("clever men", sorcerers) and, although not sharing a border, the Nukunu

Nukunu are an Aboriginal Australian people of South Australia, living around the Spencer Gulf area. In the years after British colonisation of South Australia, the area was developed to contain the cities of Port Pirie and Port Augusta.

Name

Bot ...

, who were thought to be sorcerers, incestuous and prone to commit rape.

By way of contrast and due to a shared dreaming, the relationship between the Ngarrindjeri and the ''Walkandi-woni'' (the people of the warm north-east wind), their collective name for the various groups living along the River as far as Wentworth Wentworth may refer to:

People

* Wentworth (surname)

* Judith Blunt-Lytton, 16th Baroness Wentworth (1873–1957), Lady Wentworth, notable Arabian horse breeder

* S. Wentworth Horton (1885–1960), New York state senator

* Wentworth Miller (born 1 ...

in New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

, was of significant mutual importance and the groups regularly met at Wellington

Wellington ( mi, Te Whanganui-a-Tara or ) is the capital city of New Zealand. It is located at the south-western tip of the North Island, between Cook Strait and the Remutaka Range. Wellington is the second-largest city in New Zealand by me ...

, Tailem Bend

Tailem Bend (locally, "Tailem") is a rural town in South Australia, south-east of the state capital of Adelaide. It is located on the lower reaches of the River Murray, near where the river flows into Lake Alexandrina. It is linear in layout s ...

, Murray Bridge, Mannum

Mannum is a historic town on the west bank of the Murray River in South Australia, east of Adelaide. At the 2016 census, the urban area of Mannum had a population of 2,398. Mannum is the seat of the Mid Murray Council, and is situated in the ...

or Swan Reach to exchange songs and conduct ceremonies

A ceremony (, ) is a unified ritualistic event with a purpose, usually consisting of a number of artistic components, performed on a special occasion.

The word may be of Etruscan origin, via the Latin '' caerimonia''.

Church and civil (secular) ...

. In 1849 the Rev. George Taplin

George Taplin (24 August 1831 – 24 June 1879) was a Congregationalist minister who worked in Aboriginal missions in South Australia, and gained a reputation as an anthropologist, writing on Ngarrindjeri lore and customs.

History

Taplin was bo ...

observed a mustering of 500 Ngarrindjeri warriors, and was told by another resident that as many as 800 had gathered seven years earlier.

Each of the eighteen lakinyeri had their own specific funeral customs; some smoke dried bodies before being placed in trees, on platforms, in rock shelters or buried depending on local custom. Some placed bodies in trees and collect the fallen bones for burial. Some removed the skull, which was then used for a drinking vessel. Some family groups peeled the skin from their dead to expose the pink flesh. The body was then called ''grinkari'', a term that they used to refer to the Europeans in the first years of settlement.

Lifestyle

Differing from most Australian Aboriginal communities, the fertility of their land allowed the Ngarrindjeri and Merkani to live a semi-sedentary life, moving between permanent summer and winter camps. In fact, one of the major problems encountered by Europeans was the determination of the Ngarrindjeri to rebuild their camps on land claimed for grazing. Unlike the rest of Australia, theLetters Patent establishing the Province of South Australia

The Letters Patent establishing the Province of South Australia, dated 19 February 1836 and formally titled "Letters Patent under the Great Seal of the United Kingdom erecting and establishing the Province of South Australia and fixing the bound ...

of 1936, following the ''South Australia Act 1834

The ''South Australia Act 1834'', or ''Foundation Act 1834'' and also known as the ''South Australian Colonization Act'', was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom which provided for the settlement of a province or multiple province ...

'' (or ''Foundation Act''), which together enabled the province of South Australia to be established, acknowledged Aboriginal ownership and stated that no actions could be undertaken that would "affect the rights of any Aboriginal natives of the said province to the actual occupation and enjoyment in their own persons or in the persons of their descendants of any land therein now actually occupied or enjoyed by such natives". This effectively guaranteed the land rights of Aboriginal people under force of law; however, this was interpreted by the colonists as simply meaning Aboriginal peoples could not be dispossessed of sites they permanently occupied. In May 1839, the Protector of Aborigines

The role of Protector of Aborigines was first established in South Australia in 1836.

The role became established in other parts of Australia pursuant to a recommendation contained in the ''Report of the Parliamentary Select Committee on Abori ...

William Wyatt William Wyatt may refer to:

* William Wyatt (cricketer) (1842–1908), English cricketer

* William Wyatt (scholar) (1616–1685), English scholar

*William Wyatt (settler) (1804–1886), Australian settler

* William Wyatt (weightlifter) (1893–1989 ...

announced publicly, "it appeared that the natives occupy no lands in the especial manner" described in the instructions. Bowing to the interests of prominent colonists and the Resident Commissioner who wanted to survey and sell the land without hindrance, Wyatt never recorded that sites were permanently in his reports on Aboriginal culture and practices.

Crafts and tools

Thebulrush

Bulrush is a vernacular name for several large wetland grass-like plants

*Sedge family (Cyperaceae):

**''Cyperus''

**''Scirpus''

**'' Blysmus''

**''Bolboschoenus''

**''Scirpoides''

**''Isolepis''

**''Schoenoplectus''

**''Trichophorum''

*Typhacea ...

es, reeds and sedge

The Cyperaceae are a family of graminoid (grass-like), monocotyledonous flowering plants known as sedges. The family is large, with some 5,500 known species described in about 90 genera, the largest being the "true sedges" genus ''Carex'' wit ...

s were used for basket-weaving or making rope

A rope is a group of yarns, plies, fibres, or strands that are twisted or braided together into a larger and stronger form. Ropes have tensile strength and so can be used for dragging and lifting. Rope is thicker and stronger than similarly ...

, trees provided wood for spear

A spear is a pole weapon consisting of a shaft, usually of wood, with a pointed head. The head may be simply the sharpened end of the shaft itself, as is the case with fire hardened spears, or it may be made of a more durable material fasten ...

s, and stones were fashioned into tools. The Ngarrindjeri were widely known as "outstanding craftsmen" specialising in basketry

Basket weaving (also basketry or basket making) is the process of weaving or sewing pliable materials into three-dimensional artifacts, such as baskets, mats, mesh bags or even furniture. Craftspeople and artists specialized in making baskets ...

, matting and nets with records indicating that nets of more than long were used to catch emu

The emu () (''Dromaius novaehollandiae'') is the second-tallest living bird after its ratite relative the ostrich. It is endemic to Australia where it is the largest native bird and the only extant member of the genus ''Dromaius''. The emu' ...

s. It was claimed by colonists that the nets they made for fishing were superior to those used by Europeans. The nets, made by chewing the roots of bulrush

Bulrush is a vernacular name for several large wetland grass-like plants

*Sedge family (Cyperaceae):

**''Cyperus''

**''Scirpus''

**'' Blysmus''

**''Bolboschoenus''

**''Scirpoides''

**''Isolepis''

**''Schoenoplectus''

**''Trichophorum''

*Typhacea ...

(''Typha shuttleworthii'') until only the fibre remained which was spun into threads by the women to be then woven into nets by the men, were "considered to be a sort of fortune to its owner".

Nutrition

The people were sustained by theflora and fauna

In biology, an organism () is any living system that functions as an individual entity. All organisms are composed of cells (cell theory). Organisms are classified by taxonomy into groups such as multicellular animals, plants, and fungi; ...

for food

Food is any substance consumed by an organism for nutritional support. Food is usually of plant, animal, or fungal origin, and contains essential nutrients, such as carbohydrates, fats, proteins, vitamins, or minerals. The substance is inge ...

and bush medicine. Before colonisation, there were extensive swamp

A swamp is a forested wetland.Keddy, P.A. 2010. Wetland Ecology: Principles and Conservation (2nd edition). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. 497 p. Swamps are considered to be transition zones because both land and water play a role in ...

s and woodland

A woodland () is, in the broad sense, land covered with trees, or in a narrow sense, synonymous with wood (or in the U.S., the ''plurale tantum'' woods), a low-density forest forming open habitats with plenty of sunlight and limited shade (see ...

s on the Fleurieu Peninsula, which provided habitat and food sources for a range of birds, fish, and other animals, included snake-necked turtles, yabbies, rakali

The rakali (''Hydromys chrysogaster)'', also known as the rabe or water-rat, is an Australian native rodent first described in 1804. Adoption of the Aboriginal name Rakali is intended to foster a positive public attitude by Environment Australia ...

, ducks and black swan

The black swan (''Cygnus atratus'') is a large waterbird, a species of swan which breeds mainly in the southeast and southwest regions of Australia. Within Australia, the black swan is nomadic, with erratic migration patterns dependent upon c ...

s. Flora included the native orchid

Orchids are plants that belong to the family Orchidaceae (), a diverse and widespread group of flowering plants with blooms that are often colourful and fragrant.

Along with the Asteraceae, they are one of the two largest families of flowering ...

( leek orchid), guinea flower and swamp wattle (Wirilda).

The Ngarrindjeri were well known to Europeans for their cooking skills and the efficiency of their camp ovens, the remains of which can still be found throughout the River Murray area. Some species of fish, birds and other animals considered easily caught were reserved by law for the elderly and infirm, an indication of the abundance of food in Ngarrindjeri lands. In the early years of the colony, Ngarrindjeri would volunteer to catch fish for the "white fellow men".

A wide range of foods were subject to ''ngarambi'' (taboo

A taboo or tabu is a social group's ban, prohibition, or avoidance of something (usually an utterance or behavior) based on the group's sense that it is excessively repulsive, sacred, or allowed only for certain persons.''Encyclopædia Britannica ...

) prohibitions. In regards to ngaitji (family group totems), eating them was not ngarambi but depended on the family groups' own attitude. Some family groups banned eating them, some could eat them only if they had been caught by members of another family group and some had no restrictions. Once dead the animal was no longer considered ngaitji which is Ngarrindjeri for "friend". A ngaitji was not actually sacred in the western sense but considered a "spiritual advisor" to the family group. Other foods were ngarambi but had no supernatural sanctions and these relied on attitudes to the species. Male dogs were friends of the Ngarrindjeri so were not eaten while female dogs were not eaten because they were "unclean". snakes were not eaten because of the "feel of their skin". Some bird species considered to act cruelly to other animals were ngarambi and magpies

Magpies are birds of the Corvidae family. Like other members of their family, they are widely considered to be intelligent creatures. The Eurasian magpie, for instance, is thought to rank among the world's most intelligent creatures, and is one ...

were because they warned other birds to flee if any were killed. Some bird species were ngarambi because they were the spirits of people who had died. Birds became narambi during nesting season and the malleefowl

The malleefowl (''Leipoa ocellata'') is a stocky ground-dwelling Australian bird about the size of a domestic chicken (to which it is distantly related). It is notable for the large nesting mounds constructed by the males and lack of parental ca ...

was ngarambi because its eggs were considered more valuable for food although there were no penalties for violation. Foods with supernatural sanctions were limited to bat

Bats are mammals of the order Chiroptera.''cheir'', "hand" and πτερόν''pteron'', "wing". With their forelimbs adapted as wings, they are the only mammals capable of true and sustained flight. Bats are more agile in flight than most ...

s, white owls and certain foods that were ngarambi only to women or to pregnant women. A separate category of ngarambi was young boys going through initiation. They were themselves considered ngarambi and any food they caught or prepared was ngarambi to all women who were even forbidden to see or smell it. Violation, whether accidental or deliberate, resulted in physical punishments including spearings that applied not only to the woman but to her relatives. Taplin in 1862 noted that ngarambi prohibitions were regularly being broken by children due to European influence and in the 1930s Berndt recorded that most ngarambi had been forgotten and if known, ignored.

Social organisation

According to Taplin, there were eighteen territorial clans or ''lakalinyeri'' that constituted the Ngarrindjeri "confederacy" or "nation", each of which was administered by about a dozen elders (''tendi''). Each clan's ''tendi'' in turn would convene to elect a ''rupulli'', or chieftain of the entire Ngarrindjeri confederacy. Taplin construed this as a centrally administered, hierarchical government representing tribal estates (''ruwe''), and one which was delegated to administer eighteen independent territories.Ngarrindjeri ''lakinyeri''

Taplin's list of 18 ''lakinyeri'' Each lakinyeri had its own ''nga:tji/ngaitji''. was further finessed byAlfred William Howitt

Alfred William Howitt , (17 April 1830 – 7 March 1908), also known by author abbreviation A.W. Howitt, was an Australian anthropologist, explorer and naturalist. He was known for leading the Victorian Relief Expedition, which set out to es ...

, drawing on information he obtained from Taplin, and listing 20. The following reproduces Howitt's version of that list with, where possible, the location and totem

A totem (from oj, ᑑᑌᒼ, italics=no or ''doodem'') is a spirit being, sacred object, or symbol that serves as an emblem of a group of people, such as a family, clan, lineage, or tribe, such as in the Anishinaabe clan system.

While ''the wo ...

.

Every member of a lakinyeri is related by blood and it is forbidden to marry another member of the same ''lakinyeri''. A couple also may not marry a member of another lakinyeri if they have a great-grandparent

Grandparents, individually known as grandmother and grandfather, are the parents of a person's father or mother – paternal or maternal. Every sexually-reproducing living organism who is not a genetic chimera has a maximum of four genetic gra ...

(or closer relation) in common.

Norman Tindale's research in the 1920s and Ronald

Ronald is a masculine given name derived from the Old Norse ''Rögnvaldr'',#H2, Hanks; Hardcastle; Hodges (2006) p. 234; #H1, Hanks; Hodges (2003) § Ronald. or possibly from Old English ''Regenweald''. In some cases ''Ronald'' is an Anglicised ...

and Catherine Berndt

Catherine Helen Berndt, ''née'' Webb (8 May 1918 – 12 May 1994), born in Auckland, was an Australian anthropologist known for her research in Australia and Papua New Guinea. She was awarded in 1950 the Percy Smith Medal from the University o ...

's ethnographic study, which was conducted in the 1930s, established only 10 lakinyerar. Tindale worked with Clarence Long (a Tangani man) while the Berndts worked with Albert Karloan (a Yaraldi man).

* ''Malganduwa'' – No references before Berndt. No family groups identified.

* ''Marunggulindjeri'' – No references before Berndt. Two family groups.

* ''Naberuwolin''. – No references before Berndt. No family groups identified, may be related to Potawolin.

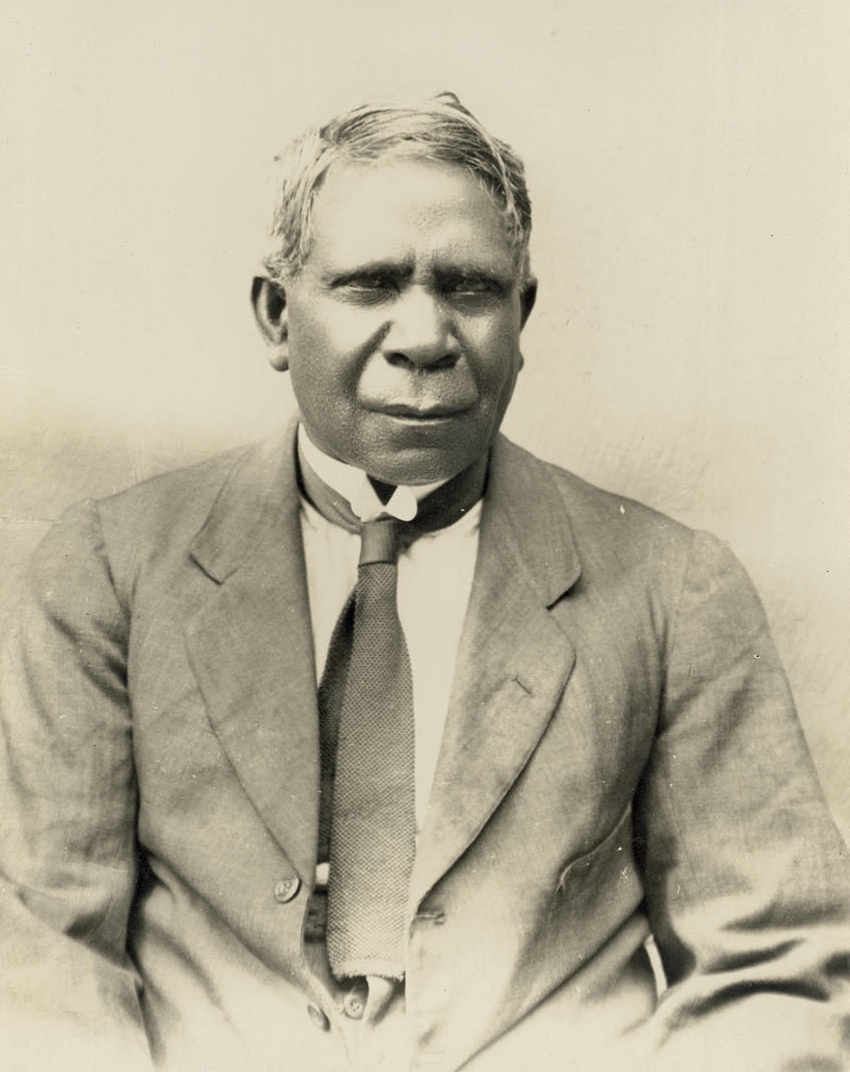

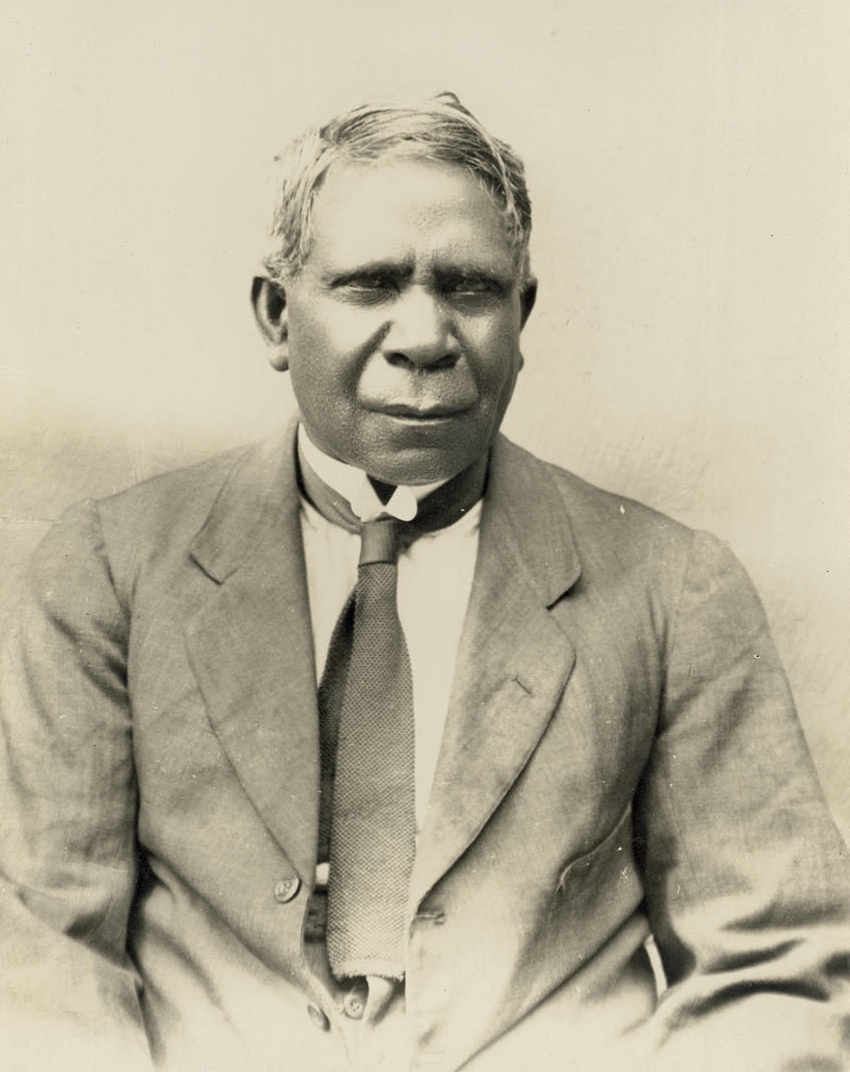

* ''Potawolin'' – Also spelt Porthaulun and Porta'ulan. David Unaipon

David Ngunaitponi (28 September 1872 – 7 February 1967), known as David Unaipon, was an Aboriginal Australian man of the Ngarrindjeri people. He was a preacher, inventor and author. Unaipon's contribution to Australian society helped to bre ...

said this was the language name and that the lakinyeri was called Waruwaldi. No family groups identified but recorded by Radcliffe-Brown (1918: 253)

* ''Ramindjeri''. – Also spelt Raminyeri, Raminjeri, Raminderar or Raminjerar (ar = plural), also known as Ramong and Tarbana-walun. 27 family groups.

* ''Tangani''. – Also spelt Tangane, Tanganarin, Tangalun and Tenggi. 19 family groups confirmed and eight recorded but not located. The Kanmerarorn and Pakindjeri lakinyeri named by Taplin are recorded as Tangani family group.

* ''Wakend''. – Also spelt Warki, Warkend, also known as Korowalle, Korowalde and Koraulun. One family group.

* ''Walerumaldi''. – Also spelt Waruwaldi (see Potawolin) Two family groups.

* ''Wonyakaldi''. – Also spelt Wunyakulde and Wanakalde. One family groups.

* ''Yaraldi''. – Also spelt Yaralde, Jaralde and Yarilde. 14 family groups. In the 1930s, the ''ruwe'' (land) of six of these family groups extended along the coast from Cape Jervis to a few kilometres south of Adelaide, land traditionally believed to be Kaurna

The Kaurna people (, ; also Coorna, Kaura, Gaurna and other variations) are a group of Aboriginal people whose traditional lands include the Adelaide Plains of South Australia. They were known as the Adelaide tribe by the early settlers. Kaurn ...

. The Rev. George Taplin recorded in 1879 that the Ramindjeri occupied the southern section of the coast from Encounter Bay, some 100 km south of Adelaide, to Cape Jervis but made no mention of any more northerly Ngarrindjeri occupation. Berndt posits that Ngarrindjeri family groups may have expanded along trade routes as the Kaurna were dispossessed by colonists.

Some lakinyeri may have disappeared and others may have merged as a result of population decline following colonisation. Additionally, family groups within the lakinyerar would use the local dialect or their own family groups name for lakinyeri names, also leading to confusion. For example, Jaralde, Jaraldi, Jarildekald and Jarildikald were separate family groups names as were Ramindjari, Ramindjerar, Ramindjeri, Ramingara, Raminjeri, Raminyeri. Several of these are also used as names for the lakinyerar. Family groups could also change their lakinyeri, Berndt found that two Tangani family groups who lived close to a Yaraldi family group had picked up their dialect and were thus now considered to be Yaraldi.

Ngarrindjeri Regional Authority

The Ngarrindjeri Regional Authority (NRA) is the peak representative body of the Ngarrindjeri people. It is made up of representatives from 12 grassroots Ngarrindjeri organisations, plus four additional elected community members. Its purpose is to: * Protect and advance the welfare of the Ngarrindjeri people, * Protect areas of special significance to the Ngarrindjeri people, * Improve the economic opportunities of the Ngarrindjeri people, * Facilitate social welfare programs benefitting aboriginal people, * PursueNative Title

Aboriginal title is a common law doctrine that the land rights of indigenous peoples to customary tenure persist after the assumption of sovereignty under settler colonialism. The requirements of proof for the recognition of aboriginal title, ...

over the traditional lands and waters of the Ngarrindjeri people,

* Enter into agreements of contracts with third parties on behalf of the Ngarrindjeri people,

* Manage land of cultural significance to the Ngarrindjeri people, and to hold any interest in such land as trustee or otherwise on their behalf,

* Act as the trustee under any trust established for the benefit of the Ngarrindjeri people,

* Protect the intellectual property

Intellectual property (IP) is a category of property that includes intangible creations of the human intellect. There are many types of intellectual property, and some countries recognize more than others. The best-known types are patents, cop ...

rights of the Ngarrindjeri people.

Notable people

* Ian Abdulla (1947–2011), artist

*

* Ian Abdulla (1947–2011), artist

* Poltpalingada Booboorowie

Poltpalingada Booboorowie (born – died 4 July 1901) was a prominent Aboriginal man of the Thooree clan of the Ngarrindjeri nation, who lived among the community of fringe dwellers in Adelaide, South Australia during the 1890s. He was a ...

(Tommy Walker), a popular Adelaide personality in the 1890s.

* Harry Hewitt

Harry Hewitt, sometimes spelled "Hewit", "Ewart" or "Hewett", ( – 23 January 1907) was an Indigenous Australian cricketer and Australian rules footballer. In 1889, Hewitt played for the Medindie Football Club, and so is believed to be the f ...

, early Australian rules footballer and cricketer.

* Ruby Hunter

Ruby Charlotte Margaret Hunter (31 October 195517 February 2010), also known as Aunty Ruby, was an Aboriginal Australian singer, songwriter and guitarist, and the life and musical partner of Archie Roach .

Early life

Ruby Hunter was born on 31 ...

, musician.

* Doreen Kartinyeri

Doreen Maude Kartinyeri (3 February 1935–2 December 2007) was an Ngarrindjeri elder and historian, born in the Australian state of South Australia. She played a key role in the Hindmarsh Bridge controversy and made many contributions to ...

(1935–2007), elder and historian

* Natascha McNamara

Natascha Duschene McNamara (born 1935 in Clare, South Australia) is an Ngarrindjeri Australian academic, activist, and researcher.David Unaipon

David Ngunaitponi (28 September 1872 – 7 February 1967), known as David Unaipon, was an Aboriginal Australian man of the Ngarrindjeri people. He was a preacher, inventor and author. Unaipon's contribution to Australian society helped to bre ...

, inventor and author, featured on the Australian $50 note

* James Unaipon

James Unaipon, born James Ngunaitponi, (c. 1835 – 1907) was an Australian Indigenous preacher of the Warrawaldie (also spelt Waruwaldi) Lakalinyeri of the Ngarrindjeri.

Born James Ngunaitponi, he took the name James Reid in honour of the Sc ...

, first Aboriginal deacon

* The Deadly Nannas

Deadly Nannas (Nragi Muthar) is a musical group from Murray Bridge, South Australia, founded around 2016.

The group of singer-songwriters is composed primarily of Ngarrindjeri women (with two ''kringkri ma:dawar'', or white sisters), and perfor ...

, musical group from Murray Bridge area

Some words

* ''kondoli'' (whale) * ''korni/korne'' (man) * ''kringkari, gringari'' (whiteman) * ''muldarpi/mularpi'' (travelling spirit of sorcerers and strangers) * ''yanun'' (speak, talk)Animals extinct since colonisation

* ''maikari''.Eastern hare-wallaby

The eastern hare-wallaby (''Lagorchestes leporides''), once also known as the common hare wallaby, is an extinct species of wallaby that was native to southeastern Australia. It was first described by John Gould in 1841.

Description

The easter ...

* ''rtulatji''. Toolache wallaby

The toolache wallaby or Grey's wallaby (''Notamacropus greyi'') is an extinct species of wallaby from southeastern South Australia and southwestern Victoria.

Taxonomy

A species described by George Waterhouse in 1846. The type specimen was co ...

* ''wi:kwai''. Pig-footed bandicoot

''Chaeropus'', known as the pig-footed bandicoots, is a genus of small mammals that became extinct during the 20th century. They were unique marsupials, of the order Peramelemorphia (bandicoots and bilbies), with unusually thin legs, yet were ab ...

Source:

Notes

Citations

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

*External links

* {{authority control Aboriginal peoples of South Australia