Ngandong on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Solo Man (''Homo erectus soloensis'') is a

Volcaniclastic rock indicates deposition occurred soon after a

Volcaniclastic rock indicates deposition occurred soon after a

The racial classification of

The racial classification of  The claim that Aboriginal Australians were descended from Asian ''H. erectus'' was expanded upon in the 1960s and 1970s as some of the oldest known (modern) human fossils were being recovered from Australia, primarily under the direction of Australian anthropologist

The claim that Aboriginal Australians were descended from Asian ''H. erectus'' was expanded upon in the 1960s and 1970s as some of the oldest known (modern) human fossils were being recovered from Australia, primarily under the direction of Australian anthropologist

The identification as adult or juvenile was based on the closure of the cranial sutures, assuming they closed at a rate similar to modern humans (though they may have closed at earlier ages in ''H. erectus''). Characteristic of ''H. erectus'', the skull is exceedingly thick in Solo Man, ranging from double to triple what would be seen in modern humans. Male and female specimens were distinguished by assuming males were more robust than females, though both males and females are exceptionally robust compared to other Asian ''H. erectus''. The adult skulls average in length times breadth, and are proportionally similar to that of the Peking Man but have a much larger circumference. Skull V is the longest at . For comparison, the dimensions of modern human skulls average for men and for women.

The Solo Man remains are characterised by more derived traits than more archaic Javan ''H. erectus'', most notably a larger brain size, an elevated

The identification as adult or juvenile was based on the closure of the cranial sutures, assuming they closed at a rate similar to modern humans (though they may have closed at earlier ages in ''H. erectus''). Characteristic of ''H. erectus'', the skull is exceedingly thick in Solo Man, ranging from double to triple what would be seen in modern humans. Male and female specimens were distinguished by assuming males were more robust than females, though both males and females are exceptionally robust compared to other Asian ''H. erectus''. The adult skulls average in length times breadth, and are proportionally similar to that of the Peking Man but have a much larger circumference. Skull V is the longest at . For comparison, the dimensions of modern human skulls average for men and for women.

The Solo Man remains are characterised by more derived traits than more archaic Javan ''H. erectus'', most notably a larger brain size, an elevated

In 1936, while studying photos taken by Dutch archaeologist , Oppenoorth made note of several broken animal bone remains, most notably damage to a large tiger skull and some deer

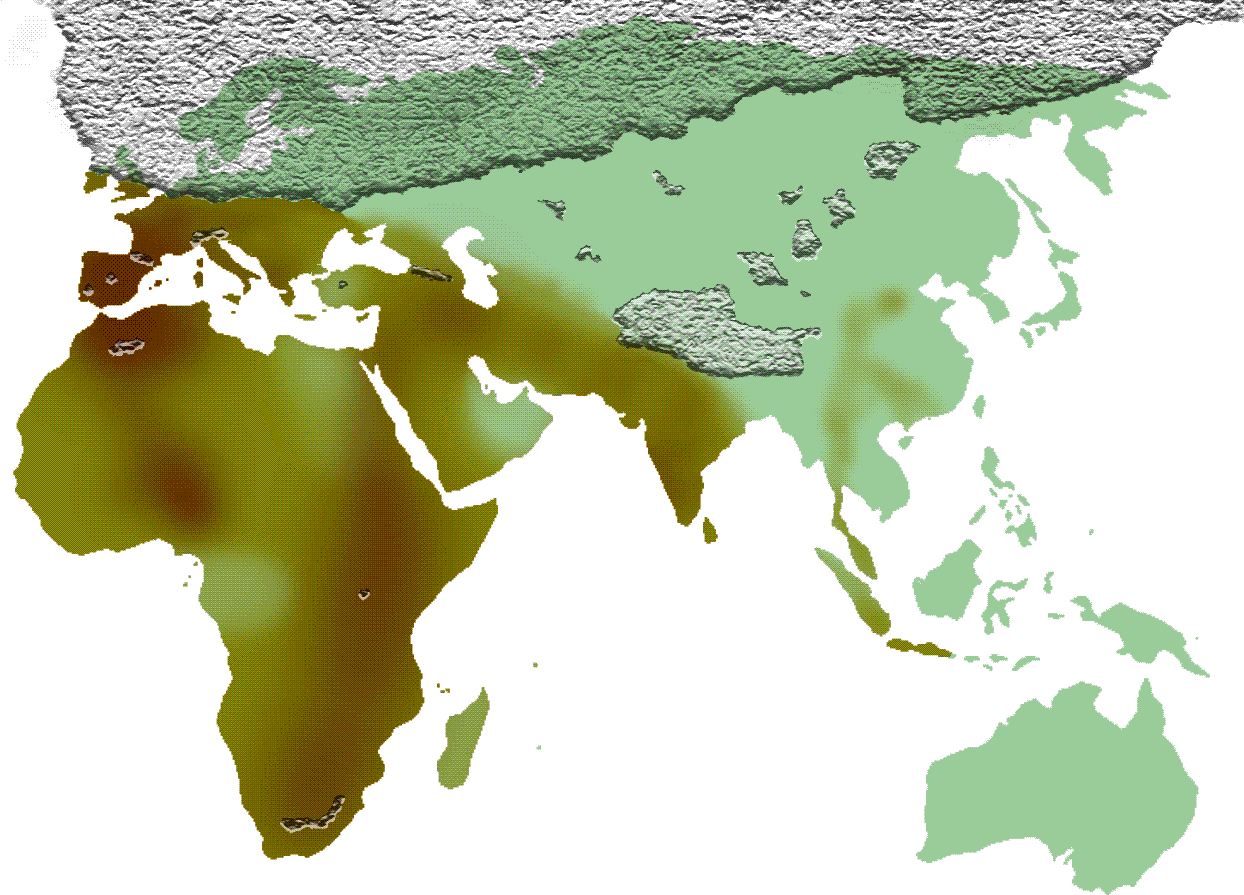

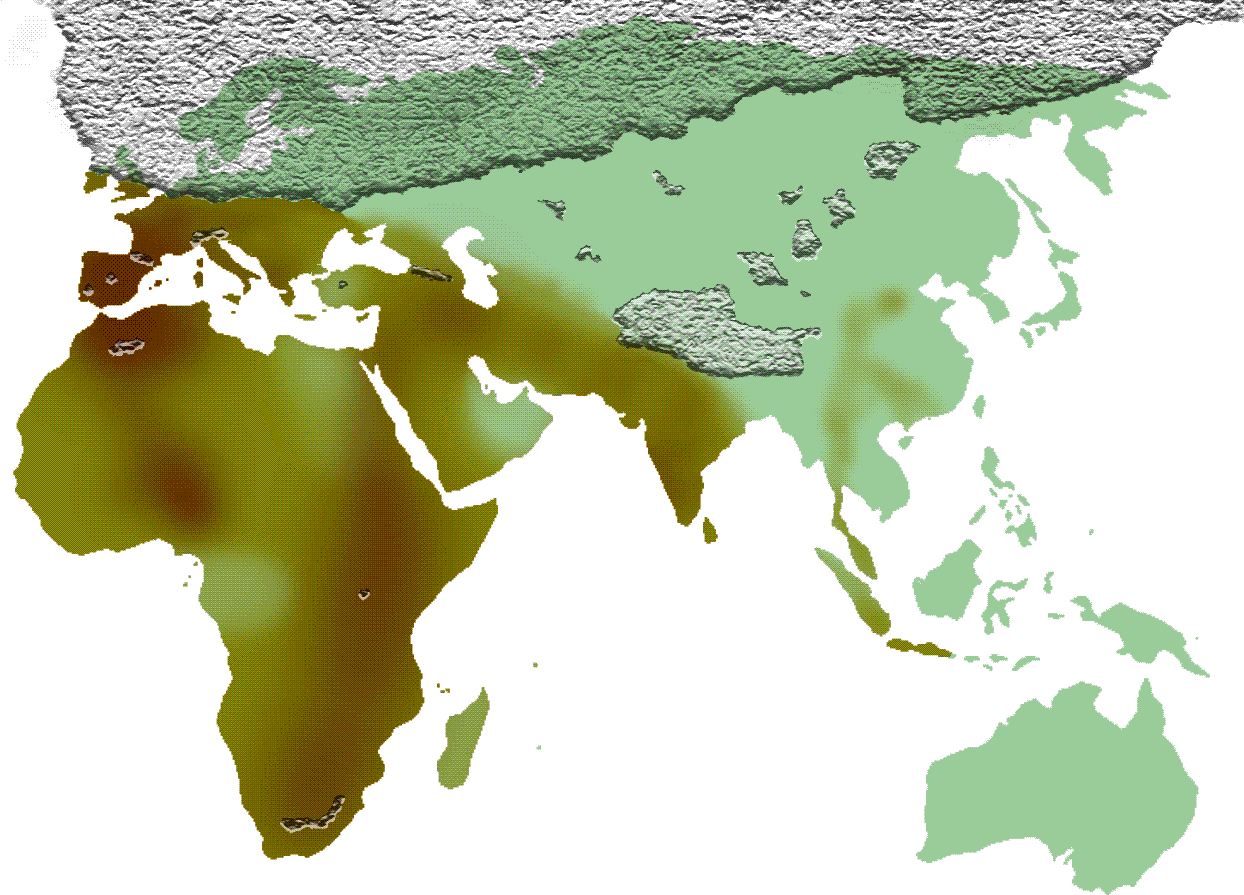

In 1936, while studying photos taken by Dutch archaeologist , Oppenoorth made note of several broken animal bone remains, most notably damage to a large tiger skull and some deer  Though a strict "Movius Line" is not well supported anymore with the discovery of some hand axe technology in Middle Pleistocene East Asia, handaxes are still conspicuously rare and crude in East Asia compared to western contemporaries. This has been explained as: the Acheulean emerged in Africa after human dispersal through East Asia (but this would require that the two populations remained separated for nearly two million years); East Asia had poorer quality raw materials, namely

Though a strict "Movius Line" is not well supported anymore with the discovery of some hand axe technology in Middle Pleistocene East Asia, handaxes are still conspicuously rare and crude in East Asia compared to western contemporaries. This has been explained as: the Acheulean emerged in Africa after human dispersal through East Asia (but this would require that the two populations remained separated for nearly two million years); East Asia had poorer quality raw materials, namely

Human Timeline (Interactive)

– Smithsonian,

subspecies

In biological classification, subspecies is a rank below species, used for populations that live in different areas and vary in size, shape, or other physical characteristics (morphology), but that can successfully interbreed. Not all species ...

of ''H. erectus

''Homo erectus'' (; meaning " upright man") is an extinct species of archaic human from the Pleistocene, with its earliest occurrence about 2 million years ago. Several human species, such as '' H. heidelbergensis'' and '' H. antecesso ...

'' that lived along the Solo River

The Solo River (known in Indonesian as Bengawan Solo, with ''Bengawan'' being an Old Javanese word for '' river'', and ''Solo'' derived from the old name for Surakarta) is the longest river in the Indonesian island of Java, it is approximately 6 ...

in Java

Java (; id, Jawa, ; jv, ꦗꦮ; su, ) is one of the Greater Sunda Islands in Indonesia. It is bordered by the Indian Ocean to the south and the Java Sea to the north. With a population of 151.6 million people, Java is the world's mo ...

, Indonesia, about 117,000 to 108,000 years ago in the Late Pleistocene

The Late Pleistocene is an unofficial age in the international geologic timescale in chronostratigraphy, also known as Upper Pleistocene from a stratigraphic perspective. It is intended to be the fourth division of the Pleistocene Epoch with ...

. This population is the last known record of the species. It is known from 14 skullcaps, two tibia

The tibia (; ), also known as the shinbone or shankbone, is the larger, stronger, and anterior (frontal) of the two bones in the leg below the knee in vertebrates (the other being the fibula, behind and to the outside of the tibia); it connects ...

e, and a piece of the pelvis

The pelvis (plural pelves or pelvises) is the lower part of the trunk, between the abdomen and the thighs (sometimes also called pelvic region), together with its embedded skeleton (sometimes also called bony pelvis, or pelvic skeleton).

The ...

excavated near the village of Ngandong, and possibly three skulls from Sambungmacan and a skull from Ngawi depending on classification. The Ngandong site was first excavated from 1931 to 1933 under the direction of Willem Frederik Florus Oppenoorth, Carel ter Haar, and Gustav Heinrich Ralph von Koenigswald

Gustav Heinrich Ralph (often cited as G. H. R.) von Koenigswald (13 November 1902 – 10 July 1982) was a German-Dutch paleontologist and geologist who conducted research on hominins, including ''Homo erectus''. His discoverie ...

, but further study was set back by the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The Financial contagion, ...

, World War II and the Indonesian War of Independence

The Indonesian National Revolution, or the Indonesian War of Independence, was an armed conflict and diplomatic struggle between the Republic of Indonesia and the Dutch Empire and an internal social revolution during Aftermath of WWII, postw ...

. In accordance with historical race concepts

The concept of race as a categorization of anatomically modern humans (''Homo sapiens'') has an extensive history in Europe and the Americas. The contemporary word ''race'' itself is modern; historically it was used in the sense of "nation, et ...

, Indonesian ''H. erectus'' subspecies were originally classified as the direct ancestors of Aboriginal Australians

Aboriginal Australians are the various Indigenous peoples of the Australian mainland and many of its islands, such as Tasmania, Fraser Island, Hinchinbrook Island, the Tiwi Islands, and Groote Eylandt, but excluding the Torres Strait Is ...

, but Solo Man is now thought to have no living descendants because the remains far predate modern human immigration into the area, which began roughly 55,000 to 50,000 years ago.

The Solo Man skull is oval-shaped in top view, with heavy brows, inflated cheekbones, and a prominent bar of bone wrapping around the back. The brain volume was quite large, ranging from , compared to an average of for present-day modern males and for present-day modern females. One potentially female specimen may have been tall and weighed ; males were probably much bigger than females. Solo Man was in many ways similar to the Java Man

Java Man (''Homo erectus erectus'', formerly also ''Anthropopithecus erectus'', ''Pithecanthropus erectus'') is an early human fossil discovered in 1891 and 1892 on the island of Java ( Dutch East Indies, now part of Indonesia). Estimated to ...

(''H. e. erectus'') that had earlier inhabited Java, but was far less archaic.

Solo Man likely inhabited an open woodland

A woodland () is, in the broad sense, land covered with trees, or in a narrow sense, synonymous with wood (or in the U.S., the ''plurale tantum'' woods), a low-density forest forming open habitats with plenty of sunlight and limited shade (see ...

environment much cooler than present-day Java, along with elephant

Elephants are the largest existing land animals. Three living species are currently recognised: the African bush elephant, the African forest elephant, and the Asian elephant. They are the only surviving members of the family Elephantidae a ...

s, tigers

The tiger (''Panthera tigris'') is the largest living cat species and a member of the genus ''Panthera''. It is most recognisable for its dark vertical stripes on orange fur with a white underside. An apex predator, it primarily preys on un ...

, wild cattle, water buffalo

The water buffalo (''Bubalus bubalis''), also called the domestic water buffalo or Asian water buffalo, is a large bovid originating in the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia. Today, it is also found in Europe, Australia, North America, S ...

, tapirs

Tapirs ( ) are large, herbivorous mammals belonging to the family Tapiridae. They are similar in shape to a pig, with a short, prehensile nose trunk. Tapirs inhabit jungle and forest regions of South and Central America, with one species inha ...

, and hippopotamuses, among other megafauna. They manufactured simple flakes and choppers (hand-held stone tool

A stone tool is, in the most general sense, any tool made either partially or entirely out of stone. Although stone tool-dependent societies and cultures still exist today, most stone tools are associated with prehistoric (particularly Stone Ag ...

s), and possibly spear

A spear is a pole weapon consisting of a shaft, usually of wood, with a pointed head. The head may be simply the sharpened end of the shaft itself, as is the case with fire hardened spears, or it may be made of a more durable material fasten ...

s or harpoon

A harpoon is a long spear-like instrument and tool used in fishing, whaling, sealing, and other marine hunting to catch and injure large fish or marine mammals such as seals and whales. It accomplishes this task by impaling the target animal ...

s from bones, daggers from stingray

Stingrays are a group of sea rays, which are cartilaginous fish related to sharks. They are classified in the suborder Myliobatoidei of the order Myliobatiformes and consist of eight families: Hexatrygonidae (sixgill stingray), Plesiobatidae ...

stingers, as well as bolas

Bolas or bolases (singular bola; from Spanish and Portuguese ''bola'', "ball", also known as a ''boleadora'' or ''boleadeira'') is a type of throwing weapon made of weights on the ends of interconnected cords, used to capture animals by entan ...

or hammerstone

In archaeology, a hammerstone is a hard cobble used to strike off lithic flakes from a lump of tool stone during the process of lithic reduction. The hammerstone is a rather universal stone tool which appeared early in most regions of the wo ...

s from andesite. They may have descended from or were at least closely related to Java Man. The Ngandong specimens likely died during a volcanic eruption. The species probably went extinct with the takeover of tropical rainforest and loss of preferred habitat, beginning by 125,000 years ago. The skulls sustained damage, but it is unclear if it resulted from an assault, cannibalism

Cannibalism is the act of consuming another individual of the same species as food. Cannibalism is a common ecological interaction in the animal kingdom and has been recorded in more than 1,500 species. Human cannibalism is well documented, b ...

, the volcanic eruption, or the fossilisation process.

Research history

Despite what English naturalistCharles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended f ...

had hypothesised in his 1871 book ''Descent of Man

''The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex'' is a book by English naturalist Charles Darwin, first published in 1871, which applies evolutionary theory to human evolution, and details his theory of sexual selection, a form of biolo ...

'', many late-19th century evolutionary naturalists postulated that Asia, not Africa, was the birthplace of humankind as it is midway between Europe and America, providing optimal dispersal routes throughout the world (the Out of Asia theory

Out may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

Films

* ''Out'' (1957 film), a documentary short about the Hungarian Revolution of 1956

* ''Out'' (1982 film), an American film directed by Eli Hollander

* ''Out'' (2002 film), a Japanese film ba ...

). Among these was German naturalist Ernst Haeckel

Ernst Heinrich Philipp August Haeckel (; 16 February 1834 – 9 August 1919) was a German zoologist, naturalist, eugenicist, philosopher, physician, professor, marine biologist and artist. He discovered, described and named thousands of new ...

who argued that the first human species (which he named "''Homo primigenius''") evolved on the now-disproven hypothetical continent "Lemuria

Lemuria (), or Limuria, was a continent proposed in 1864 by zoologist Philip Sclater, theorized to have sunk beneath the Indian Ocean, later appropriated by occultists in supposed accounts of human origins. The theory was discredited with the dis ...

" in what is now Southeast Asia, from a genus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus comes above species and below family. In binomial no ...

he termed "''Pithecanthropus

The terms ''Anthropopithecus'' ( Blainville, 1839) and ''Pithecanthropus'' ( Haeckel, 1868) are obsolete taxa describing either chimpanzees or archaic humans. Both are derived from Greek ἄνθρωπος (anthropos, "man") and πίθηκος ( ...

''" ("ape-man"). "Lemuria" had supposedly sunk below the Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or ~19.8% of the water on Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia to the east. To the south it is bounded by ...

, so no fossils could be found to prove this. Nevertheless, Haeckel's model inspired Dutch scientist Eugène Dubois

Marie Eugène François Thomas Dubois (; 28 January 1858 – 16 December 1940) was a Dutch paleoanthropologist and geologist. He earned worldwide fame for his discovery of ''Pithecanthropus erectus'' (later redesignated ''Homo erectus''), or "Jav ...

to join the Royal Netherlands East Indies Army

The Royal Netherlands East Indies Army ( nl, Koninklijk Nederlands Indisch Leger; KNIL, ) was the military force maintained by the Kingdom of the Netherlands in its colony of the Dutch East Indies, in areas that are now part of Indonesia. The ...

(KNIL) and search for his " missing link" in the Indonesian Archipelago

The islands of Indonesia, also known as the Indonesian Archipelago ( id, Kepulauan Indonesia) or Nusantara, may refer either to the islands comprising the country of Indonesia or to the geographical groups which include its islands.

History ...

. On Java

Java (; id, Jawa, ; jv, ꦗꦮ; su, ) is one of the Greater Sunda Islands in Indonesia. It is bordered by the Indian Ocean to the south and the Java Sea to the north. With a population of 151.6 million people, Java is the world's mo ...

, he found a skullcap and a femur

The femur (; ), or thigh bone, is the proximal bone of the hindlimb in tetrapod vertebrates. The head of the femur articulates with the acetabulum in the pelvic bone forming the hip joint, while the distal part of the femur articulates wit ...

(Java Man

Java Man (''Homo erectus erectus'', formerly also ''Anthropopithecus erectus'', ''Pithecanthropus erectus'') is an early human fossil discovered in 1891 and 1892 on the island of Java ( Dutch East Indies, now part of Indonesia). Estimated to ...

) dating to the late Pliocene

Late may refer to:

* LATE, an acronym which could stand for:

** Limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy, a proposed form of dementia

** Local-authority trading enterprise, a New Zealand business law

** Local average treatment effe ...

or early Pleistocene

The Early Pleistocene is an unofficial sub-epoch in the international geologic timescale in chronostratigraphy, being the earliest division of the Pleistocene Epoch within the ongoing Quaternary Period. It is currently estimated to span the time ...

at the Trinil

Trinil is a palaeoanthropological site on the banks of the Bengawan Solo River in Ngawi Regency, East Java Province, Indonesia. It was at this site in 1891 that the Dutch anatomist Eugène Dubois discovered the first early hominin remains to ...

site along the Solo River

The Solo River (known in Indonesian as Bengawan Solo, with ''Bengawan'' being an Old Javanese word for '' river'', and ''Solo'' derived from the old name for Surakarta) is the longest river in the Indonesian island of Java, it is approximately 6 ...

, which he named "''P.''" ''erectus'' (using Haeckel's hypothetical genus name) in 1893. He attempted unsuccessfully to convince the European scientific community that he had found an upright-walking ape-man. They largely dismissed his findings as a malformed non-human ape.

The "apeman of Java" nonetheless stirred up academic interest and, to find more remains, the Prussian Academy of Sciences

The Royal Prussian Academy of Sciences (german: Königlich-Preußische Akademie der Wissenschaften) was an academy established in Berlin, Germany on 11 July 1700, four years after the Prussian Academy of Arts, or "Arts Academy," to which "Berlin ...

in Berlin tasked German zoologist Emil Selenka with continuing the excavation of Trinil. Following his death in 1907, excavation was carried out by his wife and fellow zoologist Margarethe Lenore Selenka. Among the members was Dutch geologist Willem Frederik Florus Oppenoorth. The yearlong expedition was unfruitful, but the Geological Survey of Java continued to sponsor the excavation along the Solo River. Some two decades later, the Survey funded several expeditions to update maps of the island. Oppenoorth was made the head of the Java Mapping Program in 1930. One of their missions was to firmly distinguish Tertiary

Tertiary ( ) is a widely used but obsolete term for the geologic period from 66 million to 2.6 million years ago.

The period began with the demise of the non-avian dinosaurs in the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event, at the start ...

and Quaternary

The Quaternary ( ) is the current and most recent of the three periods of the Cenozoic Era in the geologic time scale of the International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS). It follows the Neogene Period and spans from 2.58 million yea ...

deposits, among the relevant sites a bed dating

Dating is a stage of romantic relationships in which two individuals engage in an activity together, most often with the intention of evaluating each other's suitability as a partner in a future intimate relationship. It falls into the catego ...

to the Pleistocene discovered by Dutch geologist Carel ter Haar in 1931, downriver from the Trinil site, near the village of Ngandong.

From 1931 to 1933, 12 skull pieces (including well-preserved skullcaps), as well as two right tibia

The tibia (; ), also known as the shinbone or shankbone, is the larger, stronger, and anterior (frontal) of the two bones in the leg below the knee in vertebrates (the other being the fibula, behind and to the outside of the tibia); it connects ...

e (shinbones), one of which was essentially complete, were recovered under the direction of Oppenoorth, ter Haar, and German-Dutch geologist Gustav Heinrich Ralph von Koenigswald

Gustav Heinrich Ralph (often cited as G. H. R.) von Koenigswald (13 November 1902 – 10 July 1982) was a German-Dutch paleontologist and geologist who conducted research on hominins, including ''Homo erectus''. His discoverie ...

. Midway through excavation, Oppenoorth retired from the Survey and returned to the Netherlands, replaced by Polish geologist in 1933. At the same time, because of the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The Financial contagion, ...

, the Survey's focus shifted to economically relevant geology, namely petroleum

Petroleum, also known as crude oil, or simply oil, is a naturally occurring yellowish-black liquid mixture of mainly hydrocarbons, and is found in geological formations. The name ''petroleum'' covers both naturally occurring unprocessed crude ...

deposits, and the excavation of Ngandong ceased completely. In 1934, ter Haar published important summaries of the Ngandong operations before contracting tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, in w ...

. He returned to the Netherlands and died two years later. Von Koenigswald, who was hired principally to study Javan mammals, was fired in 1934. After much lobbying by Zwierzycki in the Survey, and after receiving funding from the Carnegie Institution for Science

The Carnegie Institution of Washington (the organization's legal name), known also for public purposes as the Carnegie Institution for Science (CIS), is an organization in the United States established to fund and perform scientific research. Th ...

, von Koenigswald regained his position in 1937, but was too preoccupied with the Sangiran

Sangiran is an archaeological excavation site in Java in Indonesia. According to a UNESCO report (1995) "Sangiran is recognized by scientists to be one of the most important sites in the world for studying fossil man, ranking alongside Zhoukoud ...

site to continue research at Ngandong.

In 1935, the Solo Man remains were transported to Batavia (today, Jakarta

Jakarta (; , bew, Jakarte), officially the Special Capital Region of Jakarta ( id, Daerah Khusus Ibukota Jakarta) is the capital city, capital and list of Indonesian cities by population, largest city of Indonesia. Lying on the northwest coa ...

, Java, Indonesia) in the care of local university professor Willem Alphonse Mijsberg, with the hope he would take over study of the specimens. Before he had the opportunity, the fossils were moved to Bandung

Bandung ( su, ᮘᮔ᮪ᮓᮥᮀ, Bandung, ; ) is the capital city of the Indonesian province of West Java. It has a population of 2,452,943 within its city limits according to the official estimates as at mid 2021, making it the fourth most ...

, West Java

West Java ( id, Jawa Barat, su, ᮏᮝ ᮊᮥᮜᮧᮔ᮪, romanized ''Jawa Kulon'') is a province of Indonesia on the western part of the island of Java, with its provincial capital in Bandung. West Java is bordered by the province of Banten ...

in 1942 because of the Japanese occupation of the Dutch East Indies

The Empire of Japan occupied the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia) during World War II from March 1942 until after the end of the war in September 1945. It was one of the most crucial and important periods in modern Indonesian history.

In May ...

. Japanese forces interned

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simp ...

von Koenigswald for 32 months. At the cessation of the war, he was released, but the Indonesian War of Independence

The Indonesian National Revolution, or the Indonesian War of Independence, was an armed conflict and diplomatic struggle between the Republic of Indonesia and the Dutch Empire and an internal social revolution during Aftermath of WWII, postw ...

erupted. Jewish-German anthropologist Franz Weidenreich

Franz Weidenreich (7 June 1873 – 11 July 1948) was a Jewish German anatomist and physical anthropologist who studied evolution.

Life and career

Weidenreich studied at the Kaiser-Wilhelm-Universität in Strasbourg where he earned a medica ...

(who fled China before the Japanese invasion in 1941) arranged with the Rockefeller Foundation

The Rockefeller Foundation is an American private foundation and philanthropic medical research and arts funding organization based at 420 Fifth Avenue, New York City. The second-oldest major philanthropic institution in America, after the Ca ...

and The Viking Fund for von Koenigswald, his wife Luitgarde, and the Javan human remains (including Solo Man) to come to New York. Von Koenigswald and Weidenreich studied the material at the American Museum of Natural History

The American Museum of Natural History (abbreviated as AMNH) is a natural history museum on the Upper West Side of Manhattan in New York City. In Theodore Roosevelt Park, across the street from Central Park, the museum complex comprises 26 int ...

until Weidenreich's death in 1948 (leaving behind a monograph on Solo Man posthumously published in 1951). In his 1956 book ''Meeting Prehistoric Men'', von Koenigswald included a 14-page account of the Ngandong project with several unpublished results. The Solo Man remains came to be stored at Utrecht University

Utrecht University (UU; nl, Universiteit Utrecht, formerly ''Rijksuniversiteit Utrecht'') is a public research university in Utrecht, Netherlands. Established , it is one of the oldest universities in the Netherlands. In 2018, it had an enrollm ...

, the Netherlands. In 1967, von Koenigswald gave the material to Teuku Jacob for his doctoral research. Jacob oversaw the excavation of Ngandong from 1976 to 1978 and recovered two more skull specimens and a pelvic

The pelvis (plural pelves or pelvises) is the lower part of the trunk, between the abdomen and the thighs (sometimes also called pelvic region), together with its embedded skeleton (sometimes also called bony pelvis, or pelvic skeleton).

The ...

fragment. In 1978, von Koenigswald returned the material to Indonesia, and the Solo Man remains were moved to the Gadjah Mada University

Gadjah Mada University ( jv, ꦈꦤꦶꦥ꦳ꦼꦂꦱꦶꦠꦱ꧀ꦓꦗꦃꦩꦢ; id, Universitas Gadjah Mada, abbreviated as UGM) is a public research university located in Sleman, Special Region of Yogyakarta, Indonesia. Officially founded o ...

, Special Region of Yogyakarta

The Special Region of Yogyakarta (; id, Daerah Istimewa (D.I.) Yogyakarta) is a provincial-level autonomous region of Indonesia in southern Java. It has also been known as the Special Territory of Yogyakarta.

It is bordered by the Indian ...

(south-central Java).

The specimens are:

* Skull I, an almost complete skullcap probably belonging to an elderly female;

* Skull II, a frontal bone

The frontal bone is a bone in the human skull. The bone consists of two portions.''Gray's Anatomy'' (1918) These are the vertically oriented squamous part, and the horizontally oriented orbital part, making up the bony part of the forehead, part ...

probably belonging to a three to seven-year-old child;

* Skull III, a warped skullcap probably belonging to an elderly individual;

* Skull IV, a skullcap probably belonging to a middle-aged female;

* Skull V, a probable male skullcap—indicated by its great length of ;

* Skull VI, an almost complete skullcap probably belonging to an adult female;

* Skull VII, a right parietal bone

The parietal bones () are two bones in the skull which, when joined at a fibrous joint, form the sides and roof of the cranium. In humans, each bone is roughly quadrilateral in form, and has two surfaces, four borders, and four angles. It is named ...

fragment probably belonging to a young, possibly female, individual;

* Skull VIII, both parietal bones (separated) possibly belonging to a young male;

* Skull IX, a skullcap missing the base probably belonging to an elderly individual (the small size is consistent with a female, but the heaviness is consistent with a male);

* Skull X, a shattered skullcap probably belonging to a robust elderly female;

* Skull XI, a nearly complete skullcap;

* Tibia A, a few fragments of the shaft, measuring in diameter at the mid-shaft, probably belonging to an adult male;

* Tibia B, a nearly complete right tibia measuring in length at in diameter at the mid-shaft, probably belonging to an adult female;

* Ngandong 15, a partial skullcap;

* Ngandong 16, a left parietal fragment; and

* Ngandong 17, a left acetabulum

The acetabulum (), also called the cotyloid cavity, is a concave surface of the pelvis. The head of the femur meets with the pelvis at the acetabulum, forming the hip joint.

Structure

There are three bones of the ''os coxae'' (hip bone) that ...

(on the pelvis which forms part of the hip joint

In vertebrate anatomy, hip (or "coxa"Latin ''coxa'' was used by Celsus in the sense "hip", but by Pliny the Elder in the sense "hip bone" (Diab, p 77) in medical terminology) refers to either an anatomical region or a joint.

The hip region is ...

).

Age and taphonomy

The location of these fossils in the Solo terrace at the time of discovery was poorly documented. Oppenoorth, ter Haar, and von Koenigswald were only on site for 24 days of the 27 months of operation as they needed to oversee other Tertiary sites for the Survey. They left their geological assistants — Samsi and Panudju — to oversee the dig; their records are now lost. The Survey's site map remained unpublished until 2010 (over 75 years later) and is of limited use now, so thetaphonomy

Taphonomy is the study of how organisms decay and become fossilized or preserved in the paleontological record. The term ''taphonomy'' (from Greek , 'burial' and , 'law') was introduced to paleontology in 1940 by Soviet scientist Ivan Efremov t ...

and geological age of Solo Man have been contentious matters. All 14 specimens were reported to have been found in the upper section of Layer II (of six layers), which is a -thick stratum

In geology and related fields, a stratum ( : strata) is a layer of rock or sediment characterized by certain lithologic properties or attributes that distinguish it from adjacent layers from which it is separated by visible surfaces known as e ...

with gravelly sand and volcaniclastic

Volcaniclastics are geologic materials composed of broken fragments ( clasts) of volcanic rock. These encompass all clastic volcanic materials, regardless of what process fragmented the rock, how it was subsequently transported, what environment it ...

hypersthene

Hypersthene is a common rock-forming inosilicate mineral belonging to the group of orthorhombic pyroxenes. Its chemical formula is . It is found in igneous and some metamorphic rocks as well as in stony and iron meteorites. Many references ha ...

andesite. They are thought to have been deposited at around the same time, probably in a now-dry arm of the Solo River, about above the modern river. The site is about above sea level

Mean sea level (MSL, often shortened to sea level) is an average surface level of one or more among Earth's coastal bodies of water from which heights such as elevation may be measured. The global MSL is a type of vertical datuma standardised g ...

.

Volcaniclastic rock indicates deposition occurred soon after a

Volcaniclastic rock indicates deposition occurred soon after a volcanic eruption

Several types of volcanic eruptions—during which lava, tephra (ash, lapilli, volcanic bombs and volcanic blocks), and assorted gases are expelled from a volcanic vent or fissure—have been distinguished by volcanologists. These are oft ...

. Because of the sheer volume of fossils, humans and animals may have concentrated in great numbers in the valley upstream from the site due to the eruption or extreme drought. The ash would have poisoned the vegetation, or at least impeded its growth, leading to starvation and death among herbivores and humans, accumulating a mass of carcasses decomposing over several months. A lack of carnivore damage may indicate sufficient feeding was possible without having to resort to crunching through the bone. When the monsoon

A monsoon () is traditionally a seasonal reversing wind accompanied by corresponding changes in precipitation but is now used to describe seasonal changes in atmospheric circulation and precipitation associated with annual latitudinal osci ...

season came, lahars

A lahar (, from jv, ꦮ꧀ꦭꦲꦂ) is a violent type of mudflow or debris flow composed of a slurry of pyroclastic material, rocky debris and water. The material flows down from a volcano, typically along a river valley.

Lahars are extremel ...

streaming from the volcano through the river channels swept the carcasses to the Ngandong site, where they and other debris created a jam because of the channel narrowing there. The ''H. erectus'' fossils from Sambungmacan, also along the Solo River, were possibly deposited in the same event.

The dating attempts are:

* In 1932, based on the site's height above the present-day river, Oppenoorth suggested Solo Man dated to the Eemian

The Eemian (also called the last interglacial, Sangamonian Stage, Ipswichian, Mikulin, Kaydaky, penultimate,NOAA - Penultimate Interglacial Period http://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/global-warming/penultimate-interglacial-period Valdivia or Riss-Würm) wa ...

interglacial, which at the time was roughly constrained to 150 to 100 thousand years ago from the Middle/Late Pleistocene

The Late Pleistocene is an unofficial age in the international geologic timescale in chronostratigraphy, also known as Upper Pleistocene from a stratigraphic perspective. It is intended to be the fourth division of the Pleistocene Epoch with ...

transition. Later biochronological studies (using the animal remains to constrain the age) within the next few years by Oppenoorth in 1932, von Koenigswald in 1934, and ter Haar in 1936 agreed with a Late Pleistocene date.

* The Solo Man remains were first radiometrically dated in 1988 and again in 1989, using uranium–thorium dating

Uranium–thorium dating, also called thorium-230 dating, uranium-series disequilibrium dating or uranium-series dating, is a radiometric dating technique established in the 1960s which has been used since the 1970s to determine the age of calciu ...

, to 200 to 30 thousand years ago, a wide error range.

* In 1996, Solo Man teeth were dated, using electron spin resonance dating (ESR) and uranium–thorium isotope-ratio mass spectrometry

Isotope-ratio mass spectrometry (IRMS) is a specialization of mass spectrometry, in which mass spectrometric methods are used to measure the relative abundance of isotopes in a given sample.

This technique has two different applications in the ea ...

, to 53.3 to 27 thousand years ago; this would mean Solo Man outlasted continental ''H. erectus'' by at minimum 250,000 years and was contemporaneous with modern humans in Southeast Asia, who immigrated roughly 55 to 50 thousand years ago.

* In 2008, gamma spectroscopy

Gamma-ray spectroscopy is the quantitative study of the energy spectra of gamma-ray sources, such as in the nuclear industry, geochemical investigation, and astrophysics.

Most radioactive sources produce gamma rays, which are of various energi ...

on three of the skulls showed they experienced uranium leaching, and the Solo Man remains were re-dated to roughly 70 to 40 thousand years ago. This would still make it possible Solo Man was contemporaneous with modern humans.

* In 2011, argon–argon dating

Argon–argon (or 40Ar/39Ar) dating is a radiometric dating method invented to supersede potassiumargon (K/Ar) dating in accuracy. The older method required splitting samples into two for separate potassium and argon measurements, while the newer ...

of pumice

Pumice (), called pumicite in its powdered or dust form, is a volcanic rock that consists of highly vesicular rough-textured volcanic glass, which may or may not contain crystals. It is typically light-colored. Scoria is another vesicular vo ...

hornblende

Hornblende is a complex inosilicate series of minerals. It is not a recognized mineral in its own right, but the name is used as a general or field term, to refer to a dark amphibole. Hornblende minerals are common in igneous and metamorphic roc ...

yielded a maximum age of 546 ± 12 thousand years ago, and ESR and uranium–thorium dating of a mammal bone just downstream at the Jigar I site a minimum age of 143 to 77 thousand years ago. This extended interval would make it possible Solo Man was contemporaneous with continental ''H. erectus'', long before modern humans dispersed across the continent.

* In 2020, the first comprehensive chronology of the Ngandong site was published which found the Solo River was diverted through the site 500,000 years ago; the Solo terrace was deposited over 316 to 31 thousand years ago; the Ngandong terrace 141 to 92 thousand years ago; and the ''H. erectus'' bone bed 117 to 108 thousand years ago. This would mean Solo Man is indeed the last known ''H. erectus'' population and did not interact with modern humans.

Classification

The racial classification of

The racial classification of Aboriginal Australians

Aboriginal Australians are the various Indigenous peoples of the Australian mainland and many of its islands, such as Tasmania, Fraser Island, Hinchinbrook Island, the Tiwi Islands, and Groote Eylandt, but excluding the Torres Strait Is ...

, because of the conspicuous robustness

Robustness is the property of being strong and healthy in constitution. When it is transposed into a system, it refers to the ability of tolerating perturbations that might affect the system’s functional body. In the same line ''robustness'' ca ...

of the skull compared to that of other modern-day populations, has historically been a perplexing question for European science since Johann Friedrich Blumenbach

Johann Friedrich Blumenbach (11 May 1752 – 22 January 1840) was a German physician, naturalist, physiologist, and anthropologist. He is considered to be a main founder of zoology and anthropology as comparative, scientific disciplines. He was ...

(the founder of physical anthropology

Biological anthropology, also known as physical anthropology, is a scientific discipline concerned with the biological and behavioral aspects of human beings, their extinct hominin ancestors, and related non-human primates, particularly from an e ...

) introduced the topic in 1795 in his ''De Generis Humani Varietate Nativa'' ("On the Natural History of Mankind"). Following the conception of evolution

Evolution is change in the heredity, heritable Phenotypic trait, characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the Gene expression, expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to ...

by Darwin, English anthropologist Thomas Henry Huxley

Thomas Henry Huxley (4 May 1825 – 29 June 1895) was an English biologist and anthropologist specialising in comparative anatomy. He has become known as "Darwin's Bulldog" for his advocacy of Charles Darwin's theory of evolution.

The storie ...

suggested an ancestor–descendant relationship between European Neanderthal

Neanderthals (, also ''Homo neanderthalensis'' and erroneously ''Homo sapiens neanderthalensis''), also written as Neandertals, are an extinct species or subspecies of archaic humans who lived in Eurasia until about 40,000 years ago. While the ...

s and Aboriginal Australians in 1863, which was furthered by later racial anthropologists until the discovery of Indonesian archaic humans.

In 1932, Oppenoorth preliminarily drew parallels between the Solo Man skull and that of Rhodesian Man from Africa, Neanderthals, and modern day Aboriginal Australians. At the time, humans were generally believed to have originated in Central Asia, as championed primarily by American palaeontologist Henry Fairfield Osborn

Henry Fairfield Osborn, Sr. (August 8, 1857 – November 6, 1935) was an American paleontologist, geologist and eugenics advocate. He was the president of the American Museum of Natural History for 25 years and a cofounder of the American Eugen ...

and his protégé William Diller Matthew

William Diller Matthew FRS (February 19, 1871 – September 24, 1930) was a vertebrate paleontologist who worked primarily on mammal fossils, although he also published a few early papers on mineralogy, petrological geology, one on botany, one o ...

. They believed Asia was the "mother of continents" and the rising of the Himalayas

The Himalayas, or Himalaya (; ; ), is a mountain range in Asia, separating the plains of the Indian subcontinent from the Tibetan Plateau. The range has some of the planet's highest peaks, including the very highest, Mount Everest. Over list ...

and Tibet

Tibet (; ''Böd''; ) is a region in East Asia, covering much of the Tibetan Plateau and spanning about . It is the traditional homeland of the Tibetan people. Also resident on the plateau are some other ethnic groups such as Monpa, Tama ...

and subsequent drying of the region forced human ancestors to become terrestrial and bipedal

Bipedalism is a form of terrestrial locomotion where an organism moves by means of its two rear limbs or legs. An animal or machine that usually moves in a bipedal manner is known as a biped , meaning 'two feet' (from Latin ''bis'' 'double' ...

. They maintained that populations which retreated to the tropics – namely Dubois's Java Man and the " Negroid race" — substantially regressed (degeneration theory

Social degeneration was a widely influential concept at the interface of the social and biological sciences in the 18th and 19th centuries. During the 18th century, scientific thinkers including Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon, Johann Fr ...

). They also rejected Raymond Dart

Raymond Arthur Dart (4 February 1893 – 22 November 1988) was an Australian anatomist and anthropologist, best known for his involvement in the 1924 discovery of the first fossil ever found of ''Australopithecus africanus'', an extinct homi ...

's South African Taung child

The Taung Child (or Taung Baby) is the fossilised skull of a young ''Australopithecus africanus''. It was discovered in 1924 by quarrymen working for the Northern Lime Company in Taung, South Africa. Raymond Dart described it as a new species ...

(''Australopithecus africanus

''Australopithecus africanus'' is an extinct species of australopithecine which lived between about 3.3 and 2.1 million years ago in the Late Pliocene to Early Pleistocene of South Africa. The species has been recovered from Taung, Sterkfontein, ...

'') as a human ancestor, favouring the hoax Piltdown Man

The Piltdown Man was a paleoanthropological fraud in which bone fragments were presented as the fossilised remains of a previously unknown early human. Although there were doubts about its authenticity virtually from the beginning, the remains ...

from Britain. At first, Oppenoorth believed the Ngandong material represented an Asian type of Neanderthal which was more closely allied with the Rhodesian Man (also considered a Neanderthal type), and gave it a generic distinction as "''Javanthropus soloensis''". Dubois considered Solo Man to be more or less identical to the East Javan Wajak Man

The Wajak crania (also Wadjak, following the Dutch spelling of the toponym) are two fossil human skulls discovered near Wajak, a village in Tulungagung Regency, East Java, Indonesia (then Dutch East Indies) in 1888/90. The first was found on 24 O ...

(now classified as a modern human), so Oppenoorth subsequently began using the name "''Homo (Javanthropus) soloensis''". Oppenoorth hypothesised that the Java Man evolved in Indonesia and was the predecessor of modern day Aboriginal Australians, Solo Man being a transitional fossil

A transitional fossil is any fossilized remains of a life form that exhibits traits common to both an ancestral group and its derived descendant group. This is especially important where the descendant group is sharply differentiated by gross a ...

. He considered Rhodesian Man a member of this same group. As for the Chinese Peking Man

Peking Man (''Homo erectus pekinensis'') is a subspecies of ''H. erectus'' which inhabited the Zhoukoudian Cave of northern China during the Middle Pleistocene. The first fossil, a tooth, was discovered in 1921, and the Zhoukoudian Cave has si ...

(now ''H. e. pekinensis''), he believed it dispersed west and gave rise to the Neanderthals.

Thus, the ancient Java Man, Solo Man, and Rhodesian Man were commonly grouped together in the "Pithecanthropoid-Australoid

Australo-Melanesians (also known as Australasians or the Australomelanesoid, Australoid or Australioid race) is an outdated historical grouping of various people indigenous to Melanesia and Australia. Controversially, groups from Southeast Asia an ...

" lineage. "Australoid" includes Australian Aborigines and Melanesians

Melanesians are the predominant and indigenous inhabitants of Melanesia, in a wide area from Indonesia's New Guinea to as far East as the islands of Vanuatu and Fiji. Most speak either one of the many languages of the Austronesian language fa ...

. This was an extension of the multiregional origin of modern humans The multiregional hypothesis, multiregional evolution (MRE), or polycentric hypothesis is a scientific model that provides an alternative explanation to the more widely accepted "Out of Africa" model of monogenesis for the pattern of human evoluti ...

championed by Weidenreich and American racial anthropologist Carleton S. Coon

Carleton Stevens Coon (June 23, 1904 – June 3, 1981) was an American anthropologist. A professor of anthropology at the University of Pennsylvania, lecturer and professor at Harvard University, he was president of the American Association ...

, who believed that all modern races and ethnicities (which were classified into separate subspecies or even species until the mid-20th century) evolved independently from a local archaic human species (polygenism

Polygenism is a theory of human origins which posits the view that the human races are of different origins (''polygenesis''). This view is opposite to the idea of monogenism, which posits a single origin of humanity. Modern scientific views no ...

). Australian aborigines were considered the most primitive race alive. In the 1950s, German evolutionary biologist Ernst Mayr

Ernst Walter Mayr (; 5 July 1904 – 3 February 2005) was one of the 20th century's leading evolutionary biologists. He was also a renowned taxonomist, tropical explorer, ornithologist, philosopher of biology, and historian of science. His ...

entered the field of palaeoanthropology, and, surveying a "bewildering diversity of names", decided to define only three species of ''Homo'': "''H. transvaalensis''" (the australopithecines

Australopithecina or Hominina is a subtribe in the tribe Hominini. The members of the subtribe are generally ''Australopithecus'' (cladistically including the genera ''Homo'', ''Paranthropus'', and ''Kenyanthropus''), and it typically includes ...

), ''H. erectus'' (including Solo Man and several putative African and Asian taxa), and ''Homo sapiens'' (including anything younger than ''H. erectus'', such as modern humans and Neanderthals). Mayr defined them as a sequential lineage, each species evolving into the next (chronospecies

A chronospecies is a species derived from a sequential development pattern that involves continual and uniform changes from an extinct ancestral form on an evolutionary scale. The sequence of alterations eventually produces a population that is p ...

). Though Mayr later changed his opinion on the australopithecines (recognising ''Australopithecus

''Australopithecus'' (, ; ) is a genus of early hominins that existed in Africa during the Late Pliocene and Early Pleistocene. The genus ''Homo'' (which includes modern humans) emerged within ''Australopithecus'', as sister to e.g. ''Australopi ...

''), and a few species have since been named or regained some acceptance, his more conservative view of archaic human

A number of varieties of ''Homo'' are grouped into the broad category of archaic humans in the period that precedes and is contemporary to the emergence of the earliest early modern humans (''Homo sapiens'') around 300 ka. Omo-Kibish I (Omo I) f ...

diversity became widely adopted in the subsequent decades. Though Mayr did not expand upon the subspecies of ''H. erectus'', subsequent authors began formally sinking species from all parts of the Old World into it. Solo Man was placed into the "Neanderthal/Neanderthalien/Neanderthaloid group" by Weidenreich in the 1940s, which he reserved for specimens apparently transitional between ''H. erectus'' and ''H. sapiens''. The group could also be classified under the now-defunct genus "''Palaeoanthropus''". Solo man was first classified as a subspecies of ''H. erectus'' by American physical anthropologist Carleton Coon in his 1962 book ''The Origin of Races''.

The claim that Aboriginal Australians were descended from Asian ''H. erectus'' was expanded upon in the 1960s and 1970s as some of the oldest known (modern) human fossils were being recovered from Australia, primarily under the direction of Australian anthropologist

The claim that Aboriginal Australians were descended from Asian ''H. erectus'' was expanded upon in the 1960s and 1970s as some of the oldest known (modern) human fossils were being recovered from Australia, primarily under the direction of Australian anthropologist Alan Thorne

Alan Gordon Thorne (1 March 1939 – 21 May 2012) was an Australian born academic who was extensively involved with various anthropological events and is considered an authority on interpretations of Aboriginal Australian origins and the hum ...

. He noted some populations were prominently more robust than others, so he suggested Australia was colonised in two waves ("di-hybrid model"): the first wave being highly robust and descending from nearby ''H. erectus'', and the second wave more gracile (less robust) and descending from anatomically modern East Asians (who, in turn, descended from Chinese ''H. erectus''). It was subsequently discovered that some of the more robust specimens are younger than the gracile ones. In the 1980s, as African species like ''A. africanus'' became widely accepted as human ancestors and race became less salient in anthropology, the Out of Africa

''Out of Africa'' is a memoir by the Danish author Karen Blixen. The book, first published in 1937, recounts events of the seventeen years when Blixen made her home in Kenya, then called British East Africa. The book is a lyrical meditation on ...

theory overturned the Out of Asia and multiregional models. The multiregional model was consequently reworked into local populations of archaic humans having interbred and contributed at least some ancestry to modern populations in their respective regions, otherwise known as the assimilation model. Solo Man fits into this by having hybridised with the fully modern ancestors of Australian Aborigines travelling south through Southeast Asia. The assimilation model was not ubiquitously supported. In 2006, Australian palaeoanthropologist Steve Webb speculated instead that Solo Man was the first human species to reach Australia, and more robust modern Australian specimens represent hybrid populations.

The date of 117 to 108 thousand years ago for Solo Man, predating modern human dispersal through Southeast Asia (and eventually into Australia), is at odds with this conclusion. Such an ancient date leaves Solo Man with no living descendants. Similarly, a 2021 genomic study looking at the genomes of over 400 modern humans (of which 200 came from Island Southeast Asia

Maritime Southeast Asia comprises the countries of Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and East Timor. Maritime Southeast Asia is sometimes also referred to as Island Southeast Asia, Insular Southeast Asia or Oceanic Sout ...

) found no evidence of any "super-archaic" (i. e. ''H. erectus'') introgression. Solo Man has generally been considered to have descended from Java Man (''H. e. erectus'', typified by the Sangiran/Trinil populations), and the three skulls from Sambungmacan and the skull from Ngawi have been assigned to ''H. e. soloensis'' or some intermediary stage between ''H. e. erectus'' and ''H. e. soloensis''. It is largely unclear if there was gene flow from the continent. The alternate hypothesis, first proposed by Jacob in 1973, is that the Sangiran/Trinil and Ngandong/Ngawi/Sambungmacan populations were sister groups that evolved parallel

Parallel is a geometric term of location which may refer to:

Computing

* Parallel algorithm

* Parallel computing

* Parallel metaheuristic

* Parallel (software), a UNIX utility for running programs in parallel

* Parallel Sysplex, a cluster of IB ...

to each other. If the alternate is correct, this could warrant species distinction as "''H. soloensis''", but the definitions of species and subspecies, especially in palaeoanthropology

Paleoanthropology or paleo-anthropology is a branch of paleontology and anthropology which seeks to understand the early development of anatomically modern humans, a process known as hominization, through the reconstruction of evolutionary kinship ...

, are poorly drawn.

Anatomy

The identification as adult or juvenile was based on the closure of the cranial sutures, assuming they closed at a rate similar to modern humans (though they may have closed at earlier ages in ''H. erectus''). Characteristic of ''H. erectus'', the skull is exceedingly thick in Solo Man, ranging from double to triple what would be seen in modern humans. Male and female specimens were distinguished by assuming males were more robust than females, though both males and females are exceptionally robust compared to other Asian ''H. erectus''. The adult skulls average in length times breadth, and are proportionally similar to that of the Peking Man but have a much larger circumference. Skull V is the longest at . For comparison, the dimensions of modern human skulls average for men and for women.

The Solo Man remains are characterised by more derived traits than more archaic Javan ''H. erectus'', most notably a larger brain size, an elevated

The identification as adult or juvenile was based on the closure of the cranial sutures, assuming they closed at a rate similar to modern humans (though they may have closed at earlier ages in ''H. erectus''). Characteristic of ''H. erectus'', the skull is exceedingly thick in Solo Man, ranging from double to triple what would be seen in modern humans. Male and female specimens were distinguished by assuming males were more robust than females, though both males and females are exceptionally robust compared to other Asian ''H. erectus''. The adult skulls average in length times breadth, and are proportionally similar to that of the Peking Man but have a much larger circumference. Skull V is the longest at . For comparison, the dimensions of modern human skulls average for men and for women.

The Solo Man remains are characterised by more derived traits than more archaic Javan ''H. erectus'', most notably a larger brain size, an elevated cranial vault

The cranial vault is the space in the skull within the neurocranium, occupied by the brain.

Development

In humans, the cranial vault is imperfectly composed in newborns, to allow the large human head to pass through the birth canal. During bi ...

, reduced postorbital constriction, and less developed brow ridges. They still closely resemble earlier ''H. erectus''. Like Peking Man, there was a slight sagittal keel

In the human skull, a sagittal keel, or sagittal torus, is a thickening of part or all of the midline of the frontal bone, or parietal bones where they meet along the sagittal suture, or on both bones. Sagittal keels differ from sagittal crests, w ...

running across the midline of the skull. Compared to other Asian ''H. erectus'', the forehead is proportionally low and also has a low angle of inclination. The brow ridges do not form a continuous bar like in Peking Man, but curve downwards at the midpoint, forming a nasal bridge. The brows are quite thick, especially at the lateral ends (nearest the edge of the face). Like Peking Man, the frontal sinus

The frontal sinuses are one of the four pairs of paranasal sinuses that are situated behind the brow ridges. Sinuses are mucosa-lined airspaces within the bones of the face and skull. Each opens into the anterior part of the corresponding middle n ...

es are confined to between the eyes rather than extending into the brow region. Compared to Neanderthals and modern humans, the area the temporal muscle

In anatomy, the temporalis muscle, also known as the temporal muscle, is one of the muscles of mastication (chewing). It is a broad, fan-shaped convergent muscle on each side of the head that fills the temporal fossa, superior to the zygomatic a ...

would have covered is rather flat. The brow ridges merge into markedly thickened cheek bones. The skull is phenozygous, in that the skullcap is proportionally narrow compared to the cheekbones, so that the latter are still visible when looking down at the skull in top-view. The squamous part of the temporal bone

The squamous part of temporal bone, or temporal squama, forms the front and upper part of the temporal bone, and is scale-like, thin, and translucent.

Surfaces

Its outer surface is smooth and convex; it affords attachment to the temporal muscl ...

is triangular like that of Peking Man, and the infratemporal crest is quite sharp. Like earlier Javan ''H. erectus'', the inferior and superior temporal lines (on the parietal bone) diverge towards the back of the skull.

At the back of the skull, there is a sharp, thick occipital torus (a projecting bar of bone) which marks a clear separation between the occipital and nuchal planes. The occipital torus projects the most at the part corresponding to the external occipital protuberance

Near the middle of the squamous part of occipital bone is the external occipital protuberance, the highest point of which is referred to as the inion. The inion is the most prominent projection of the protuberance which is located at the posterioi ...

in modern humans. The base of the temporal bone is consistent with Java Man and Peking Man rather than Neanderthals and modern humans. Unlike Neanderthals and modern humans, there is a defined bony pyramid structure near the root of the pterygoid bone

The pterygoid is a paired bone forming part of the palate of many vertebrates, behind the palatine bone

In anatomy, the palatine bones () are two irregular bones of the facial skeleton in many animal species, located above the uvula in the ...

. The mastoid part of the temporal bone

The mastoid part of the temporal bone is the posterior (back) part of the temporal bone, one of the bones of the skull. Its rough surface gives attachment to various muscles (via tendons) and it has openings for blood vessels. From its borders, t ...

at the base of the skull notably juts out. The occipital condyles

The occipital condyles are undersurface protuberances of the occipital bone in vertebrates, which function in articulation with the superior facets of the atlas vertebra.

The condyles are oval or reniform (kidney-shaped) in shape, and their anter ...

(which connect the skull to the spine) are proportionally small compared to the foramen magnum

The foramen magnum ( la, great hole) is a large, oval-shaped opening in the occipital bone of the skull. It is one of the several oval or circular openings (foramina) in the base of the skull. The spinal cord, an extension of the medulla oblonga ...

(where the spinal cord

The spinal cord is a long, thin, tubular structure made up of nervous tissue, which extends from the medulla oblongata in the brainstem to the lumbar region of the vertebral column (backbone). The backbone encloses the central canal of the spi ...

passes into the skull). Large, irregular bony projections lie directly behind the occipital condyles.

The brain volumes of the six Ngandong specimens for which the metric is calculable range from 1,013 to 1,251 cm3. The Ngawi I skull measures 1,000 cm3; and the three Sambungmacan skulls (respectively) 1,035; 917; and 1,006 cm3. This makes for an average of over 1,000 cm3. For comparison, present-day modern humans average 1,270 cm3 for males and 1,130 cm3 for females, with a standard deviation

In statistics, the standard deviation is a measure of the amount of variation or dispersion of a set of values. A low standard deviation indicates that the values tend to be close to the mean (also called the expected value) of the set, whil ...

of roughly 115 and 100 cm3. Chinese ''H. erectus'' (ranging 780 to 250 thousand years ago) average roughly 1,028 cm3, and Javan ''H. erectus'' (excluding Ngandong) about 933 cm3. Overall, Asian ''H. erectus'' are big-brained, averaging roughly 1,000 cm3. The base of the braincase, and thus the brain, seems to have been flat rather than curved. The sella turcica

The sella turcica (Latin for 'Turkish saddle') is a saddle-shaped depression in the body of the sphenoid bone of the human skull and of the skulls of other hominids including chimpanzees, gorillas and orangutans. It serves as a cephalometric la ...

at the base of the skull, near the pituitary gland

In vertebrate anatomy, the pituitary gland, or hypophysis, is an endocrine gland, about the size of a chickpea and weighing, on average, in humans. It is a protrusion off the bottom of the hypothalamus at the base of the brain. The hypoph ...

, is much larger than that of modern humans, which Weidenreich in 1951 cautiously attributed to an enlarged gland which caused the extraordinary thickening of the bones.

Of the two known tibiae, tibia A is much more robust than Tibia B and is consistent overall with Neanderthal tibiae. Like other ''H. erectus'', the tibiae are thick and heavy. Based on the reconstructed length of , Tibia B may have belonged to a tall, individual. Tibia A is assumed to have belonged to a larger individual. Asian ''H. erectus'', for which height estimates are taken (a rather small sample size), typically range from , with Indonesian ''H. erectus'' in tropical environments typically scoring on the higher end, and continental specimens in colder latitudes on the lower end. The single pelvic fragment from Ngandong has not yet been described formally.

Culture

Palaeohabitat

At the species level, the Ngandong fauna is similar overall to the older Kedung Brubus fauna roughly 800 to 700 thousand years ago, a time of mass immigration of large mammal species to Java, including Asian elephants and ''Stegodon

''Stegodon'' ("roofed tooth" from the Ancient Greek words , , 'to cover', + , , 'tooth' because of the distinctive ridges on the animal's molars) is an extinct genus of proboscidean, related to elephants. It was originally assigned to the famil ...

''. Other Ngandong fauna include the tiger ''Panthera tigris soloensis

''Panthera tigris soloensis'', known as the Ngandong tiger, is an extinct subspecies of the modern tiger species. It inhabited the Sundaland region of Indonesia during the Pleistocene epoch.

Discoveries

Fossils of the Ngandong tiger were exc ...

'', Malayan tapir

The Malayan tapir (''Tapirus indicus''), also called Asian tapir, Asiatic tapir and Indian tapir, is the only tapir species native to Southeast Asia from the Malay Peninsula to Sumatra. It has been listed as Endangered on the IUCN Red List since ...

, the hippo '' Hexaprotodon'', sambar deer

The sambar (''Rusa unicolor'') is a large deer native to the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia that is listed as a vulnerable species on the IUCN Red List since 2008. Populations have declined substantially due to severe hunting, local ins ...

, water buffalo

The water buffalo (''Bubalus bubalis''), also called the domestic water buffalo or Asian water buffalo, is a large bovid originating in the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia. Today, it is also found in Europe, Australia, North America, S ...

, the cow ''Bos palaesondaicus

''Bos palaesondaicus'' occurred on Pleistocene Java (Indonesia) and belongs to the Bovinae subfamily. It has been described by the Dutch paleoanthropologist Eugène Dubois in 1908.Dubois, E. (1908). Das Geologische Alter der Kendengoder Trinil ...

'', pigs

The pig (''Sus domesticus''), often called swine, hog, or domestic pig when distinguishing from other members of the genus '' Sus'', is an omnivorous, domesticated, even-toed, hoofed mammal. It is variously considered a subspecies of ''Sus s ...

, and crab-eating macaque

The crab-eating macaque (''Macaca fascicularis''), also known as the long-tailed macaque and referred to as the cynomolgus monkey in laboratories, is a cercopithecine primate native to Southeast Asia. A species of macaque, the crab-eating macaqu ...

. These are consistent with an open woodland

A woodland () is, in the broad sense, land covered with trees, or in a narrow sense, synonymous with wood (or in the U.S., the ''plurale tantum'' woods), a low-density forest forming open habitats with plenty of sunlight and limited shade (see ...

environment. The presence of the common crane

The common crane (''Grus grus''), also known as the Eurasian crane, is a bird of the family Gruidae, the cranes. A medium-sized species, it is the only crane commonly found in Europe besides the demoiselle crane (''Grus virgo'') and the Siberi ...

in the nearby contemporaneous Watualang site could indicate much cooler conditions than today. The driest conditions probably corresponded to the glacial maximum roughly 135,000 years ago, exposing the Sunda shelf

Geologically, the Sunda Shelf is a south-eastern extension of the continental shelf of Mainland Southeast Asia. Major landmasses on the shelf include the Bali, Borneo, Java, Madura, and Sumatra, as well as their surrounding smaller islands. I ...

and connecting the major Indonesian islands to the continent. By 125,000 years ago, the climate became much wetter, making Java an island, and allowing for the expansion of tropical rainforests. This caused the succession of the Ngandong fauna by the Punung fauna, which represents the modern day animal assemblage of Java, though more typical Punung fauna — namely orangutans

Orangutans are great apes native to the rainforests of Indonesia and Malaysia. They are now found only in parts of Borneo and Sumatra, but during the Pleistocene they ranged throughout Southeast Asia and South China. Classified in the genus ' ...

and gibbon

Gibbons () are apes in the family Hylobatidae (). The family historically contained one genus, but now is split into four extant genera and 20 species. Gibbons live in subtropical and tropical rainforest from eastern Bangladesh to Northeast Indi ...

s — probably could not penetrate the island until it was reconnected to the continent after 80,000 years ago. ''H. erectus'', a specialist in woodland and savannah biomes, likely went extinct with the loss of the last open-habitat refugia.

''H. e. soloensis'' was the last population of a long occupation history of the island of Java by ''H. erectus'', beginning 1.51 to 0.93 million years ago at the Sangiran site, continuing 540 to 430 thousand years ago at the Trinil site, and finally 117 to 108 thousand years ago at Ngandong. If the date is correct for Solo Man, then they would represent a terminal population of ''H. erectus'' which sheltered in the last open-habitat refuges of East Asia before the rainforest takeover. Before the immigration of modern humans, Late Pleistocene Southeast Asia was also home to '' H. floresiensis'' endemic to the island of Flores

Flores is one of the Lesser Sunda Islands, a group of islands in the eastern half of Indonesia. Including the Komodo Islands off its west coast (but excluding the Solor Archipelago to the east of Flores), the land area is 15,530.58 km2, and t ...

, Indonesia, and '' H. luzonensis'' endemic to the island of Luzon

Luzon (; ) is the largest and most populous island in the Philippines. Located in the northern portion of the Philippines archipelago, it is the economic and political center of the nation, being home to the country's capital city, Manila, a ...

, the Philippines. Genetic analysis of present-day Southeast Asian populations indicates the widespread dispersal of the Denisovans

The Denisovans or Denisova hominins ) are an extinct species or subspecies of archaic human that ranged across Asia during the Lower and Middle Paleolithic. Denisovans are known from few physical remains and consequently, most of what is known ...

(a species currently recognisable only by their genetic signature) across Southeast Asia, whereupon they interbred with immigrating modern humans 45.7 and 29.8 thousand years ago. A 2021 genomic study indicates that, aside from the Denisovans, modern humans never interbred with any of these endemic human species, unless the offspring were unviable or the hybrid lineages have since died out.

Judging by the sheer number of specimens deposited at Ngandong at the same time, there may have been a sizeable population of ''H. e soloensis'' before the volcanic eruption which resulted in their interment, but population is difficult to approximate with certainty. The Ngandong site was some distance away from the northern coast of the island, but it is unclear where the southern shoreline and the mouth of the Solo River would have been.

Technology

In 1936, while studying photos taken by Dutch archaeologist , Oppenoorth made note of several broken animal bone remains, most notably damage to a large tiger skull and some deer

In 1936, while studying photos taken by Dutch archaeologist , Oppenoorth made note of several broken animal bone remains, most notably damage to a large tiger skull and some deer antlers

Antlers are extensions of an animal's skull found in members of the Cervidae (deer) family. Antlers are a single structure composed of bone, cartilage, fibrous tissue, skin, nerves, and blood vessels. They are generally found only on ma ...

, which he considered evidence of bone technology. He suggested some deer antlers had a carved bird skull hafted onto the end to be used as axes. In 1951, Weidenreich voiced his scepticism—as the bones were invariably damaged by the river, and perhaps crocodiles

Crocodiles (family Crocodylidae) or true crocodiles are large semiaquatic reptiles that live throughout the tropics in Africa, Asia, the Americas and Australia. The term crocodile is sometimes used even more loosely to include all extant taxo ...

and other natural processes—arguing instead that none of the bones reliably show any evidence of human modification. Oppenoorth further suggested a long piece of bone carved with an undulating pattern on both sides was used as a harpoon

A harpoon is a long spear-like instrument and tool used in fishing, whaling, sealing, and other marine hunting to catch and injure large fish or marine mammals such as seals and whales. It accomplishes this task by impaling the target animal ...

, similar to harpoons manufactured in the Magdalenian

The Magdalenian cultures (also Madelenian; French: ''Magdalénien'') are later cultures of the Upper Paleolithic and Mesolithic in western Europe. They date from around 17,000 to 12,000 years ago. It is named after the type site of La Madele ...

of Europe, but Weidenreich interpreted it as a spearhead. Weidenreich made note of anomalous inland stingray

Stingrays are a group of sea rays, which are cartilaginous fish related to sharks. They are classified in the suborder Myliobatoidei of the order Myliobatiformes and consist of eight families: Hexatrygonidae (sixgill stingray), Plesiobatidae ...

stingers at Ngandong, which he supposed were collected by Solo Man for use as daggers or arrowheads, similar to some recent South Pacific peoples. It is unclear if this apparent bone technology can be associated with Solo Man or later modern human activity, though the Trinil ''H. e. erectus'' population seems to have worked with such material, manufacturing scrapers from '' Pseudodon'' shells and possibly opening them up with shark teeth

Sharks continually shed their teeth; some Carcharhiniformes shed approximately 35,000 teeth in a lifetime, replacing those that fall out. There are four basic types of shark teeth: dense flattened, needle-like, pointed lower with triangular upp ...

.

Oppenoorth also identified a perfectly round andesite stone ball from Ngandong, a common occurrence in the Solo Valley, ranging in diameter from . As well, similar balls have been identified in contemporaneous and younger European Mousterian

The Mousterian (or Mode III) is an archaeological industry of stone tools, associated primarily with the Neanderthals in Europe, and to the earliest anatomically modern humans in North Africa and West Asia. The Mousterian largely defines the l ...

and African Middle Stone Age

The Middle Stone Age (or MSA) was a period of African prehistory between the Early Stone Age and the Late Stone Age. It is generally considered to have begun around 280,000 years ago and ended around 50–25,000 years ago. The beginnings of p ...

sites, as ancient as African Acheulean

Acheulean (; also Acheulian and Mode II), from the French ''acheuléen'' after the type site of Saint-Acheul, is an archaeological industry of stone tool manufacture characterized by the distinctive oval and pear-shaped " hand axes" associate ...

sites (notably Olorgesailie, Kenya). On Java, they have been found at Watualang (contemporaneous with Ngandong) and Sangiran. Traditionally, these have been interpreted as bolas

Bolas or bolases (singular bola; from Spanish and Portuguese ''bola'', "ball", also known as a ''boleadora'' or ''boleadeira'') is a type of throwing weapon made of weights on the ends of interconnected cords, used to capture animals by entan ...

(tied together in twos or threes and flung as a hunting weapon), but also individually thrown projectiles, club heads, or plant-processing or bone-breaking tools. In 1993, American archaeologists Kathy Schick

use both this parameter and , birth_date to display the person's date of birth, date of death, and age at death) -->

, death_place =

, death_cause =

, body_discovered =

, resting_place =

, resting_place_coordinates ...

and Nicholas Toth

Nicholas Patrick Toth (born September 22, 1952) is an American archaeologist and paleoanthropologist. He is a Professor in the Cognitive Science Program at Indiana University and is a founder and co-director of the Stone Age Institute. Toth's a ...

demonstrated the spherical shape could be reproduced simply if the stone is used as a hammer for an extended period.

In 1938, von Koenigswald returned to the Ngandong site along with archaeologists Helmut de Terra, Hallam L. Movius and Pierre Teilhard de Chardin

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin ( (); 1 May 1881 – 10 April 1955) was a French Jesuit priest, scientist, paleontologist, theologian, philosopher and teacher. He was Darwinian in outlook and the author of several influential theological and philos ...

to collect lithic cores and flakes (i.e. stone tools

A stone tool is, in the most general sense, any tool made either partially or entirely out of stone. Although stone tool-dependent societies and cultures still exist today, most stone tools are associated with prehistoric (particularly Stone Ag ...

). Because of wear caused by the river, it is difficult to identify with confidence that some of these rocks are actual tools. They are small and simple, usually smaller than and made most commonly of chalcedony

Chalcedony ( , or ) is a cryptocrystalline form of silica, composed of very fine intergrowths of quartz and moganite. These are both silica minerals, but they differ in that quartz has a trigonal crystal structure, while moganite is monoclinic. ...

(but also chert

Chert () is a hard, fine-grained sedimentary rock composed of microcrystalline or cryptocrystalline quartz, the mineral form of silicon dioxide (SiO2). Chert is characteristically of biological origin, but may also occur inorganically as a c ...

and jasper