Newark, England on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Newark-on-Trent or Newark () is a

After the break with Rome in the 16th century, the establishment of the

After the break with Rome in the 16th century, the establishment of the

In the English Civil War, Newark was a Royalist stronghold, Charles I having raised his standard in nearby Nottingham. "Newark was besieged on three occasions and finally surrendered only when ordered to do so by the King after his own surrender." It was attacked in February 1643 by two troops of horsemen, but beat them back. The town fielded at times as many as 600 soldiers, and raided Nottingham,

In the English Civil War, Newark was a Royalist stronghold, Charles I having raised his standard in nearby Nottingham. "Newark was besieged on three occasions and finally surrendered only when ordered to do so by the King after his own surrender." It was attacked in February 1643 by two troops of horsemen, but beat them back. The town fielded at times as many as 600 soldiers, and raided Nottingham,

About 1770 the Great North Road around Newark (now the A616) was raised on a long series of arches to ensure it remained clear of the regular floods. A special

About 1770 the Great North Road around Newark (now the A616) was raised on a long series of arches to ensure it remained clear of the regular floods. A special

In the

In the

*The Market Place is the town's focal point. It includes ''The Queen's Head'', one of the town's old pubs.

*The Church of St. Mary Magdalene is a

*The Market Place is the town's focal point. It includes ''The Queen's Head'', one of the town's old pubs.

*The Church of St. Mary Magdalene is a

Newark's churches include the Grade I listed

Newark's churches include the Grade I listed

''Radio Newark''

began broadcasting on 107.8 FM in May 2015, after three successful trials in 2014 and 2015. It replaced a community station, Boundary Sound, which ceased broadcasting in 2011.

Retrieved 3 December 2017

*

Newark Town CouncilNewark Carnival

Community carnival for Newark * {{DEFAULTSORT:Newark-On-Trent Towns in Nottinghamshire Market towns in Nottinghamshire Newark and Sherwood

market town

A market town is a settlement most common in Europe that obtained by custom or royal charter, in the Middle Ages, a market right, which allowed it to host a regular market; this distinguished it from a village or city. In Britain, small rural ...

and civil parish

In England, a civil parish is a type of administrative parish used for local government. It is a territorial designation which is the lowest tier of local government below districts and counties, or their combined form, the unitary authorit ...

in the Newark and Sherwood

Newark and Sherwood is a local government district and is the largest district in Nottinghamshire, England. The district was formed on 1 April 1974, by a merger of the municipal borough of Newark with Newark Rural District and Southwell R ...

district in Nottinghamshire

Nottinghamshire (; abbreviated Notts.) is a landlocked county in the East Midlands region of England, bordering South Yorkshire to the north-west, Lincolnshire to the east, Leicestershire to the south, and Derbyshire to the west. The trad ...

, England. It is on the River Trent

The Trent is the third-longest river in the United Kingdom. Its source is in Staffordshire, on the southern edge of Biddulph Moor. It flows through and drains the North Midlands. The river is known for dramatic flooding after storms and ...

, and was historically a major inland port

An inland port is a port on an inland waterway, such as a river, lake, or canal, which may or may not be connected to the sea. The term "inland port" is also used to refer to a dry port.

Examples

The United States Army Corps of Engineers pub ...

. The A1 road bypasses the town on the line of the ancient Great North Road. The town's origins are likely to be Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

* Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lett ...

, as it lies on a major Roman road, the Fosse Way

The Fosse Way was a Roman road built in Britain during the first and second centuries AD that linked Isca Dumnoniorum (Exeter) in the southwest and Lindum Colonia ( Lincoln) to the northeast, via Lindinis ( Ilchester), Aquae Sulis (Bath), ...

. It grew up round Newark Castle and as a centre for the wool and cloth trades.

In the English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I (" Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of r ...

, it was besieged by Parliamentary forces and relieved by Royalist forces under Prince Rupert

Prince Rupert of the Rhine, Duke of Cumberland, (17 December 1619 (O.S.) / 27 December (N.S.) – 29 November 1682 (O.S.)) was an English army officer, admiral, scientist and colonial governor. He first came to prominence as a Royalist caval ...

. Newark has a market place lined with many historical buildings and one of its most notable landmark is St Mary Magdalene church with its towering spire at high and the highest structure in the town. The church is the tallest church in Nottinghamshire and can be seen when entering Newark or bypassing it.

History

Early history

The place-name Newark is first attested in thecartulary

A cartulary or chartulary (; Latin: ''cartularium'' or ''chartularium''), also called ''pancarta'' or ''codex diplomaticus'', is a medieval manuscript volume or roll ('' rotulus'') containing transcriptions of original documents relating to the f ...

of Eynsham Abbey

Eynsham Abbey was a Benedictine monastery in Eynsham, Oxfordshire, in England between 1005 and 1538. King Æthelred allowed Æthelmær the Stout to found the abbey in 1005. There is some evidence that the abbey was built on the site of an earli ...

in Oxfordshire, where it appears as "Newercha" in about 1054–1057 and "Niweweorche" in about 1075–1092. It appears as "Newerche" in the 1086 Domesday Book

Domesday Book () – the Middle English spelling of "Doomsday Book" – is a manuscript record of the "Great Survey" of much of England and parts of Wales completed in 1086 by order of King William I, known as William the Conqueror. The manusc ...

. The name "New werk" has the apparent meaning of "New fort".

The origins of the town are possibly Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

* Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lett ...

, from its position on an important Roman road, the Fosse Way

The Fosse Way was a Roman road built in Britain during the first and second centuries AD that linked Isca Dumnoniorum (Exeter) in the southwest and Lindum Colonia ( Lincoln) to the northeast, via Lindinis ( Ilchester), Aquae Sulis (Bath), ...

. In a document which purports to be a charter of 664 AD, Newark is mentioned as having been granted to the Abbey of Peterborough by King Wulfhere of Mercia

Wulfhere or Wulfar (died 675) was King of Mercia from 658 until 675 AD. He was the first Christian king of all of Mercia, though it is not known when or how he converted from Anglo-Saxon paganism. His accession marked the end of Oswiu of North ...

. An Anglo-Saxon pagan

Anglo-Saxon paganism, sometimes termed Anglo-Saxon heathenism, Anglo-Saxon pre-Christian religion, or Anglo-Saxon traditional religion, refers to the religious beliefs and practices followed by the Anglo-Saxons between the 5th and 8th centurie ...

cemetery used from the early fifth to early seventh centuries has been found in Millgate, Newark, close to the Fosse Way and the River Trent. There cremated remains were buried in pottery urns.

In the reign of Edward the Confessor

Edward the Confessor ; la, Eduardus Confessor , ; ( 1003 – 5 January 1066) was one of the last Anglo-Saxon English kings. Usually considered the last king of the House of Wessex, he ruled from 1042 to 1066.

Edward was the son of Æt ...

, Newark belonged to Godiva

Lady Godiva (; died between 1066 and 1086), in Old English , was a late Anglo-Saxon noblewoman who is relatively well documented as the wife of Leofric, Earl of Mercia, and a patron of various churches and monasteries. Today, she is mainly reme ...

and her husband Leofric, Earl of Mercia

Leofric (died 31 August or 30 September 1057) was an Earl of Mercia. He founded monasteries at Coventry and Much Wenlock. Leofric is most remembered as the husband of Lady Godiva.

Life

Leofric was the son of Leofwine, Ealdorman of the Hwicce, ...

, who granted it to Stow Minster

The Minster Church of St Mary, Stow in Lindsey, is a major Anglo-Saxon church in Lincolnshire and is one of the largest and oldest parish church buildings in England. It has been claimed that the Minster originally served as the cathedral church ...

in 1055. After the Norman Conquest

The Norman Conquest (or the Conquest) was the 11th-century invasion and occupation of England by an army made up of thousands of Norman, Breton, Flemish, and French troops, all led by the Duke of Normandy, later styled William the Conq ...

, Stow Minster retained the revenues of Newark, but it came under the control of the Norman Bishop Remigius de Fécamp

Remigius de Fécamp (sometimes Remigius; died 7 May 1092) was a Benedictine monk who was a supporter of William the Conqueror.

Early life

Remigius' date of birth is unknown, although he was probably born sometime during the 1030s, as canon la ...

, after whose death control passed to the Bishops of Lincoln from 1092 until the reign of Edward VI

Edward VI (12 October 1537 – 6 July 1553) was King of England and Ireland from 28 January 1547 until his death in 1553. He was crowned on 20 February 1547 at the age of nine. Edward was the son of Henry VIII and Jane Seymour and the first E ...

. There were burgesses in Newark at the time of the Domesday

Domesday Book () – the Middle English spelling of "Doomsday Book" – is a manuscript record of the "Great Survey" of much of England and parts of Wales completed in 1086 by order of King William I, known as William the Conqueror. The manusc ...

survey. The reign of Edward III

Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from January 1327 until his death in 1377. He is noted for his military success and for restoring r ...

shows evidence that it had long been a borough

A borough is an administrative division in various English-speaking countries. In principle, the term ''borough'' designates a self-governing walled town, although in practice, official use of the term varies widely.

History

In the Middle Ag ...

by prescription. The Newark wapentake (hundred) in the east of Nottinghamshire was established in the period of Anglo-Saxon

The Anglo-Saxons were a cultural group who inhabited England in the Early Middle Ages. They traced their origins to settlers who came to Britain from mainland Europe in the 5th century. However, the ethnogenesis of the Anglo-Saxons happened wit ...

rule (10th–11th centuries).

Medieval to Stuart period

Newark Castle was originally a fortifiedmanor house

A manor house was historically the main residence of the lord of the manor. The house formed the administrative centre of a manor in the European feudal system; within its great hall were held the lord's manorial courts, communal meals ...

founded by the Anglo-Saxon King Edward the Elder. In 1073, Remigius de Fécamp

Remigius de Fécamp (sometimes Remigius; died 7 May 1092) was a Benedictine monk who was a supporter of William the Conqueror.

Early life

Remigius' date of birth is unknown, although he was probably born sometime during the 1030s, as canon la ...

, Bishop of Lincoln, put up an earthwork motte-and-bailey

A motte-and-bailey castle is a European fortification with a wooden or stone keep situated on a raised area of ground called a motte, accompanied by a walled courtyard, or bailey, surrounded by a protective ditch and palisade. Relatively easy t ...

fortress on the site. The river bridge was built about this time under a charter from Henry I Henry I may refer to:

876–1366

* Henry I the Fowler, King of Germany (876–936)

* Henry I, Duke of Bavaria (died 955)

* Henry I of Austria, Margrave of Austria (died 1018)

* Henry I of France (1008–1060)

* Henry I the Long, Margrave of the N ...

, as was St Leonard's Hospital. The bishopric also gained from the king a charter to hold a five-day fair at the castle each year, and under King Stephen

Stephen or Steven is a common English first name. It is particularly significant to Christians, as it belonged to Saint Stephen ( grc-gre, Στέφανος ), an early disciple and deacon who, according to the Book of Acts, was stoned to death; ...

to establish a mint. King John died of dysentery

Dysentery (UK pronunciation: , US: ), historically known as the bloody flux, is a type of gastroenteritis that results in bloody diarrhea. Other symptoms may include fever, abdominal pain, and a feeling of incomplete defecation. Complications ...

in Newark Castle in 1216.

The town became a local centre for the wool and cloth trade – by the time of Henry II a major market was held there. Wednesday and Saturday markets in the town were founded in the period 1156–1329, under a series of charters from the Bishop of Lincoln. After his death, Henry III tried to bring order to the country, but the mercenary Robert de Gaugy refused to yield Newark Castle to the Bishop of Lincoln

The Bishop of Lincoln is the ordinary (diocesan bishop) of the Church of England Diocese of Lincoln in the Province of Canterbury.

The present diocese covers the county of Lincolnshire and the unitary authority areas of North Lincolnshire and ...

, its rightful owner. This led to the Dauphin of France

Dauphin of France (, also ; french: Dauphin de France ), originally Dauphin of Viennois (''Dauphin de Viennois''), was the title given to the heir apparent to the throne of France from 1350 to 1791, and from 1824 to 1830. The word ''dauphin' ...

(later King Louis VIII of France

Louis VIII (5 September 1187 – 8 November 1226), nicknamed The Lion (french: Le Lion), was King of France from 1223 to 1226. As prince, he invaded England on 21 May 1216 and was excommunicated by a papal legate on 29 May 1216. On 2 June 1216 ...

) laying an eight-day siege on behalf of the king, ended by an agreement to pay the mercenary to leave. Around the time of Edward III

Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from January 1327 until his death in 1377. He is noted for his military success and for restoring r ...

's death in 1377, "Poll tax

A poll tax, also known as head tax or capitation, is a tax levied as a fixed sum on every liable individual (typically every adult), without reference to income or resources.

Head taxes were important sources of revenue for many governments f ...

records show an adult population of 1,178, excluding beggars and clergy, making Newark one of the biggest 25 or so towns in England."

In 1457 a flood swept away the bridge over the Trent. Although there was no legal requirement to do so, the Bishop of Lincoln, John Chaworth, funded a new bridge of oak with stone defensive towers at either end. In January 1571 or 1572, the composer Robert Parsons fell into the swollen River Trent at Newark and drowned.

Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Brit ...

, and the Dissolution of the Monasteries, Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disa ...

had the Vicar of Newark, Henry Lytherland, executed for refusing to acknowledge the king as head of the Church. The dissolution affected Newark's political landscape. Even more radical changes came in 1547, when the Bishop of Lincoln

The Bishop of Lincoln is the ordinary (diocesan bishop) of the Church of England Diocese of Lincoln in the Province of Canterbury.

The present diocese covers the county of Lincolnshire and the unitary authority areas of North Lincolnshire and ...

exchanged ownership of the town with the Crown. Newark was incorporated under an alderman

An alderman is a member of a municipal assembly or council in many jurisdictions founded upon English law. The term may be titular, denoting a high-ranking member of a borough or county council, a council member chosen by the elected members ...

and twelve assistants in 1549, and the charter was confirmed and extended by Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is sometimes referred to as the "Virgin Queen".

Eli ...

.

Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

reincorporated the town under a mayor

In many countries, a mayor is the highest-ranking official in a municipal government such as that of a city or a town. Worldwide, there is a wide variance in local laws and customs regarding the powers and responsibilities of a mayor as well ...

and aldermen, owing to its increasing commercial prosperity. This charter, except for a temporary surrender under James II, continued to govern the corporation until the Municipal Corporations Act 1835

The Municipal Corporations Act 1835 (5 & 6 Will 4 c 76), sometimes known as the Municipal Reform Act, was an Act of Parliament, Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that reformed local government in the incorporated boroughs of England and ...

.

The Civil War

Grantham

Grantham () is a market and industrial town in the South Kesteven district of Lincolnshire, England, situated on the banks of the River Witham and bounded to the west by the A1 road. It lies some 23 miles (37 km) south of the Lincoln a ...

, Northampton

Northampton () is a market town and civil parish in the East Midlands of England, on the River Nene, north-west of London and south-east of Birmingham. The county town of Northamptonshire, Northampton is one of the largest towns in England ...

, Gainsborough and other places with mixed success, but enough to cause it to rise to national notice. In 1644 Newark was besieged by forces from Nottingham, Lincoln and Derby

Derby ( ) is a city and unitary authority area in Derbyshire, England. It lies on the banks of the River Derwent in the south of Derbyshire, which is in the East Midlands Region. It was traditionally the county town of Derbyshire. Derby g ...

, until relieved in March by Prince Rupert

Prince Rupert of the Rhine, Duke of Cumberland, (17 December 1619 (O.S.) / 27 December (N.S.) – 29 November 1682 (O.S.)) was an English army officer, admiral, scientist and colonial governor. He first came to prominence as a Royalist caval ...

.

Parliament commenced a new siege towards the end of January 1645 after more raiding, but this was relieved about a month later by Sir Marmaduke Langdale

Marmaduke Langdale, 1st Baron Langdale ( – 5 August 1661) was an English landowner and soldier who fought with the Royalists during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms.

An only child who inherited large estates, he served in the 1620 to 1622 Palat ...

. Newark cavalry fought with the king's forces, which were decisively defeated in the Battle of Naseby

The Battle of Naseby took place on 14 June 1645 during the First English Civil War, near the village of Naseby in Northamptonshire. The Parliamentarian New Model Army, commanded by Sir Thomas Fairfax and Oliver Cromwell, destroyed the main ...

, near Leicester

Leicester ( ) is a city status in the United Kingdom, city, Unitary authorities of England, unitary authority and the county town of Leicestershire in the East Midlands of England. It is the largest settlement in the East Midlands.

The city l ...

in June 1645.

The final siege began in November 1645, by which time the town's defences had been much strengthened. Two major forts had been built just outside the town, one called the Queen's Sconce

Sconce and Devon Park is a park in Newark, Nottinghamshire, England. It is the location of Queen's sconce, an earthwork fortification that was built in 1646 during the First English Civil War, to protect the garrison of King Charles I based at ...

to the south-west, and another, the King's Sconce, to the north-east, both close to the river, with defensive walls and a water-filled ditch of 2¼ miles around the town. The King's May 1646 order to surrender was only accepted under protest by the town's garrison. After that, much of the defences was destroyed, including the Castle, which was left in essentially the state it can be seen today. The Queen's Sconce was left largely untouched; its remains are in Sconce and Devon Park

Sconce and Devon Park is a park in Newark, Nottinghamshire, England. It is the location of Queen's sconce, an earthwork fortification that was built in 1646 during the First English Civil War, to protect the garrison of King Charles I based at ...

.

Georgian era and early 19th century

About 1770 the Great North Road around Newark (now the A616) was raised on a long series of arches to ensure it remained clear of the regular floods. A special

About 1770 the Great North Road around Newark (now the A616) was raised on a long series of arches to ensure it remained clear of the regular floods. A special Act of Parliament

Acts of Parliament, sometimes referred to as primary legislation, are texts of law passed by the legislative body of a jurisdiction (often a parliament or council). In most countries with a parliamentary system of government, acts of parliame ...

in 1773 allowed the creation of a town hall next to the Market Place. Designed by John Carr of York

John Carr (1723–1807) was a prolific English architect, best known for Buxton Crescent in Derbyshire and Harewood House in West Yorkshire. Much of his work was in the Palladian style. In his day he was considered to be the leading architect in ...

and completed in 1776, Newark Town Hall is now a Grade I listed building, housing a museum and art gallery. In 1775 the Duke of Newcastle

Duke of Newcastle upon Tyne was a title that was created three times, once in the Peerage of England and twice in the Peerage of Great Britain. The first grant of the title was made in 1665 to William Cavendish, 1st Marquess of Newcastle ...

, at the time the Lord of the Manor and a major landowner in the area, built a new brick bridge with stone facing to replace a dilapidated one next to the Castle. This is still one of the town's major thoroughfares today.

A noted 18th-century advocate of reform in Newark was the printer and newspaper owner Daniel Holt (1766–1799). He was imprisoned for printing a leaflet advocating parliamentary reform and for selling a pamphlet by Thomas Paine

Thomas Paine (born Thomas Pain; – In the contemporary record as noted by Conway, Paine's birth date is given as January 29, 1736–37. Common practice was to use a dash or a slash to separate the old-style year from the new-style year. In th ...

.

In a milieu of parliamentary reform, the Duke of Newcastle evicted over a hundred Newark tenants whom he believed to support directly or indirectly at the 1829 elections the Liberal/Radical candidate (Wilde), rather than his candidate, (Michael Sadler, a progressive Conservative).

J. S. Baxter, a schoolboy in Newark in 1830–1840, contributed to ''The Hungry Forties: Life under the Bread Tax'' (London, 1904), a book about the Corn Laws

The Corn Laws were tariffs and other trade restrictions on imported food and corn enforced in the United Kingdom between 1815 and 1846. The word ''corn'' in British English denotes all cereal grains, including wheat, oats and barley. They wer ...

: "Chartists and rioters came from Nottingham into Newark, parading the streets with penny loaves dripped in blood carried on pikes, crying 'Bread or blood'."

19th–21st centuries

Many buildings and much industry appeared in theVictorian era

In the history of the United Kingdom and the British Empire, the Victorian era was the period of Queen Victoria's reign, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. The era followed the Georgian period and preceded the Edwa ...

. The buildings included the Independent Chapel (1822), Holy Trinity (1836–1837), Christ Church (1837), Castle Railway Station (1846), the Wesleyan Chapel (1846), the Corn Exchange (1848), the Methodist New Connexion Chapel (1848), W. N. Nicholson Trent Ironworks (1840s), Northgate Railway Station (1851), North End Wesleyan Chapel (1868), St Leonard's Anglican Church (1873), the Baptist Chapel (1876), the Primitive Methodist Chapel (1878), Newark Hospital

Newark Hospital is a health facility in Newark-on-Trent, Nottinghamshire, England. It is managed by the Sherwood Forest Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust.

History

The hospital has its origins in a workhouse established in Hawton Road (now Albert S ...

(1881), Ossington Coffee Palace (1882), Gilstrap Free Library (1883), the Market Hall (1884), the Unitarian Chapel (1884), the Fire Station (1889), the Waterworks (1898), and the School of Science and Art (1900).

The Ossington Coffee Palace was built by Lady Charlotte Ossington, daughter of the 4th Duke of Portland and widow of a former Speaker of the House of Commons, Viscount Ossington

A viscount ( , for male) or viscountess (, for female) is a title used in certain European countries for a noble of varying status.

In many countries a viscount, and its historical equivalents, was a non-hereditary, administrative or judicial ...

. It was designed to be a Temperance

Temperance may refer to:

Moderation

*Temperance movement, movement to reduce the amount of alcohol consumed

*Temperance (virtue), habitual moderation in the indulgence of a natural appetite or passion

Culture

* Temperance (group), Canadian dan ...

alternative to pubs and coaching inns.

These changes and industrial growth raised the population from under 7,000 in 1800 to over 15,000 by the end of the century. The Sherwood Avenue Drill Hall opened in 1914 as the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

began.

In the

In the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

there were several RAF stations within a few miles of Newark, many holding squadrons of the Polish Air Force

The Polish Air Force ( pl, Siły Powietrzne, , Air Forces) is the aerial warfare branch of the Polish Armed Forces. Until July 2004 it was officially known as ''Wojska Lotnicze i Obrony Powietrznej'' (). In 2014 it consisted of roughly 16,425 mi ...

. A plot was set aside in Newark Cemetery for RAF burials. This is now the war graves plot, where all but ten of the 90 Commonwealth and all of the 397 Polish burials were made. The cemetery also has 49 scattered burials from the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

. A memorial cross to the Polish airmen buried there was unveiled in 1941 by President Raczkiewicz, ex-President of the Polish Republic and head of the wartime Polish government in London, supported by Władysław Sikorski

Władysław Eugeniusz Sikorski (; 20 May 18814 July 1943) was a Polish military and political leader.

Prior to the First World War, Sikorski established and participated in several underground organizations that promoted the cause for Polish i ...

, head of the Polish Armed Forces in the West

The Polish Armed Forces in the West () refers to the Polish military formations formed to fight alongside the Western Allies against Nazi Germany and its allies during World War II. Polish forces were also raised within Soviet territories; th ...

and Prime Minister of the Polish Government in Exile in 1939–1943. When the two died – Sikorski in 1943 and Raczkiewicz in 1947 – they were buried at the foot of the monument. Sikorski's remains were returned to Poland in 1993, but his former grave in Newark remains as a monument. RAF Winthorpe

Royal Air Force Winthorpe or more simply RAF Winthorpe' is a former Royal Air Force station located north-east of Newark in Nottinghamshire, England. It is now the site of Newark Air Museum and Newark Showground.

It initially opened as a sate ...

was opened in 1940 and declared inactive in 1959. The site is now the location of the Newark Air Museum

Newark Air Museum is an air museum located on a former Royal Air Force station at Winthorpe, near Newark-on-Trent in Nottinghamshire, England. The museum contains a variety of aircraft.

History

The airfield was known as RAF Winthorpe during ...

.

The main industries in Newark in the last hundred years have been clothing, bearings, pumps, agricultural machinery and pine furniture, and the refining of sugar. British Sugar

British Sugar plc is a subsidiary of Associated British Foods and the sole British producer of sugar from sugar beet, as well as medicinal cannabis.

British Sugar processes all sugar beet grown in the United Kingdom, and produces about two-thi ...

still has one of its sugar-beet processing factories to the north of the town near the A616 (Great North Road). There have been several factory closures, especially since the 1950s. The breweries

A brewery or brewing company is a business that makes and sells beer. The place at which beer is commercially made is either called a brewery or a beerhouse, where distinct sets of brewing equipment are called plant. The commercial brewing of beer ...

that closed in the 20th century included James Hole and Warwicks-and-Richardsons.

Population

Newark's population had a population of 27,700 at the 2011 census. The ONS Mid Year Population Estimates for 2007 indicated that the population had risen to some 26,700. Another estimate (2009): "The population of Newark itself was 27,700 and the district of Newark and Sherwood has a population of 75,000al at the 2011 Census. TheOffice for National Statistics

The Office for National Statistics (ONS; cy, Swyddfa Ystadegau Gwladol) is the executive office of the UK Statistics Authority, a non-ministerial department which reports directly to the UK Parliament.

Overview

The ONS is responsible for ...

also identifies a wider "Newark-on-Trent built up area" with a 2011 census population of 43,363 ''Includes map showing area'' and a "Newark-on-Trent built up area subdivision" with a population of 37,084. ''Includes map showing area''

In the 2011 census, 77 per cent of adults in the town are employed, according to the latest ONS data, compared with a national average of 72 per cent. Earnings are 7 per cent above the average in the surrounding East Midlands.

Geography

Newark is fromNottingham

Nottingham ( , locally ) is a city and unitary authority area in Nottinghamshire, East Midlands, England. It is located north-west of London, south-east of Sheffield and north-east of Birmingham. Nottingham has links to the legend of Robi ...

, from Lincoln

Lincoln most commonly refers to:

* Abraham Lincoln (1809–1865), the sixteenth president of the United States

* Lincoln, England, cathedral city and county town of Lincolnshire, England

* Lincoln, Nebraska, the capital of Nebraska, U.S.

* Lincol ...

and from Leicester

Leicester ( ) is a city status in the United Kingdom, city, Unitary authorities of England, unitary authority and the county town of Leicestershire in the East Midlands of England. It is the largest settlement in the East Midlands.

The city l ...

. All are connected to the town by the A46 road

The A46 is a major A road in England. It starts east of Bath, Somerset and ends in Cleethorpes, Lincolnshire, but it does not form a continuous route. Large portions of the old road have been lost, bypassed, or replaced by motorway developmen ...

. The town is also around from Mansfield

Mansfield is a market town and the administrative centre of Mansfield District in Nottinghamshire, England. It is the largest town in the wider Mansfield Urban Area (followed by Sutton-in-Ashfield). It gained the Royal Charter of a market to ...

, from Grantham

Grantham () is a market and industrial town in the South Kesteven district of Lincolnshire, England, situated on the banks of the River Witham and bounded to the west by the A1 road. It lies some 23 miles (37 km) south of the Lincoln a ...

, from Sleaford

Sleaford is a market town and civil parish in the North Kesteven district of Lincolnshire, England. Centred on the former parish of New Sleaford, the modern boundaries and urban area include Quarrington to the south-west, Holdingham to the no ...

, from Southwell and from Bingham.

Newark lies on the bank of the River Trent, with the River Devon running as a tributary through the town. Standing at the intersection of the Great North Road and the Fosse Way

The Fosse Way was a Roman road built in Britain during the first and second centuries AD that linked Isca Dumnoniorum (Exeter) in the southwest and Lindum Colonia ( Lincoln) to the northeast, via Lindinis ( Ilchester), Aquae Sulis (Bath), ...

, Newark originally grew around Newark Castle, now ruined, and a large market place now lined with historic buildings.

Newark forms a single built-up area with the neighbouring parish of Balderton to the south-east. To the south, on the A46 road

The A46 is a major A road in England. It starts east of Bath, Somerset and ends in Cleethorpes, Lincolnshire, but it does not form a continuous route. Large portions of the old road have been lost, bypassed, or replaced by motorway developmen ...

, is Farndon, and to the north Winthorpe.

Newark's growth and development have been enhanced by one of few bridges over the River Trent, by the navigability of the river, by the presence of the Great North Road (the A1, etc.), and later by the advance of the railways, bringing a junction between the East Coast Main Line

The East Coast Main Line (ECML) is a electrified railway between London and Edinburgh via Peterborough, Doncaster, York, Darlington, Durham and Newcastle. The line is a key transport artery on the eastern side of Great Britain running b ...

and the Nottingham to Lincoln route. "Newark became a substantial inland port, particularly for the wool trade," though it industrialised somewhat in the Victorian era and later had an ironworks, engineering, brewing and a sugar refinery.

The A1 bypass was opened in 1964 by the then Minister of Transport, Ernest Marples

Alfred Ernest Marples, Baron Marples, (9 December 1907 – 6 July 1978) was a British Conservative politician who served as Postmaster General (1957–1959) and Minister of Transport (1959–1964).

As Postmaster General, he oversaw the introdu ...

. The single-carriageway, £34 million A46 opened in October 1990.

Governance

The parliamentary borough of Newark returned twoMembers of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members of ...

(MPs) to the Unreformed House of Commons

"Unreformed House of Commons" is a name given to the House of Commons of Great Britain and (after 1800 the House of Commons of the United Kingdom) before it was reformed by the Reform Act 1832, the Irish Reform Act 1832, and the Scottish Reform ...

from 1673. It was the last borough to be created before the Reform Act. William Ewart Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone ( ; 29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British statesman and Liberal politician. In a career lasting over 60 years, he served for 12 years as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, spread over four non-con ...

, later Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is ...

, became its MP in 1832 and was re-elected in 1835, in 1837, and in 1841 twice, but possibly due to his support of the repeal

A repeal (O.F. ''rapel'', modern ''rappel'', from ''rapeler'', ''rappeler'', revoke, ''re'' and ''appeler'', appeal) is the removal or reversal of a law. There are two basic types of repeal; a repeal with a re-enactment is used to replace the law ...

of the Corn Laws

The Corn Laws were tariffs and other trade restrictions on imported food and corn enforced in the United Kingdom between 1815 and 1846. The word ''corn'' in British English denotes all cereal grains, including wheat, oats and barley. They wer ...

and other issues he stood elsewhere after that time.

Newark elections were central to two interesting legal cases. In 1945, a challenge to Harold Laski

Harold Joseph Laski (30 June 1893 – 24 March 1950) was an English political theorist and economist. He was active in politics and served as the chairman of the British Labour Party from 1945 to 1946 and was a professor at the London School o ...

, the Chairman of the National Executive Committee of the Labour Party

The National Executive Committee (NEC) is the governing body of the UK Labour Party, setting the overall strategic direction of the party and policy development. Its composition has changed over the years, and includes representatives of affilia ...

, led Laski to sue the ''Daily Express

The ''Daily Express'' is a national daily United Kingdom middle-market newspaper printed in tabloid format. Published in London, it is the flagship of Express Newspapers, owned by publisher Reach plc. It was first published as a broadsheet ...

'', which had reported him as saying Labour might take power by violence if defeated at the polls. Laski vehemently denied saying this, but lost the action. In the 1997 general election, Newark returned Fiona Jones

Fiona Elizabeth Ann Jones (née Hamilton; 27 February 1957 – 28 January 2007) was a Labour Party politician in the United Kingdom. She was elected as a Member of Parliament (MP) for Newark in Labour's landslide victory in the 1997 general e ...

of the Labour Party. Jones and her election agent Des Whicher were convicted of submitting a fraudulent declaration of expenses, but the conviction was overturned on appeal.

Newark's former MP Patrick Mercer

Patrick John Mercer (born 26 June 1956) is a British author and former politician. He was elected as a Conservative in the 2001 general election, until resigning the party's parliamentary whip in May 2013 following questions surrounding paid ad ...

, Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

held the position of Shadow Minister for Homeland Security from June 2003 until March 2007, when he had to resign after making racially contentious comments to ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper '' The Sunday Times'' ( ...

''.

At a by-election on 5 June 2014 after the resignation of Patrick Mercer

Patrick John Mercer (born 26 June 1956) is a British author and former politician. He was elected as a Conservative in the 2001 general election, until resigning the party's parliamentary whip in May 2013 following questions surrounding paid ad ...

, he was replaced by the Conservative Robert Jenrick, who was re-elected at the general election of 7 May 2015.

Newark has three local-government tiers: Newark Town Council, Newark and Sherwood District Council and Nottinghamshire County Council

Nottinghamshire County Council is the upper-tier local authority for the non-metropolitan county of Nottinghamshire in England. It consists of 66 county councillors, elected from 56 electoral divisions every four years. The most recent electi ...

. The 39 district councillors cover waste, planning, environmental health, licensing, car parks, housing, leisure and culture. It opened a national Civil War Centre and Newark Museum in May 2015. The area elects ten councillors to Nottinghamshire County Council. It provides children's services, adult care, and highways and transport services. The town has an elected council of 18 members from four wards. Newark Town Council has taken on some responsibilities devolved by Newark and Sherwood District Council, including parks, open spaces and Newark Market. It also runs events such as the LocAle and Weinfest, a museum in the Town Hall, and allotments.

A new police station costing £7 million opened in October 2006.

Education

The town has three main mixedsecondary schools

A secondary school describes an institution that provides secondary education and also usually includes the building where this takes place. Some secondary schools provide both '' secondary education, lower secondary education'' (ages 11 to 14) ...

. The older, Magnus Church of England Academy

Magnus Church of England Academy (formerly Magnus Church of England School and Magnus Grammar School before that) often abbreviated as 'Magnus', is a British secondary school located in the market town of Newark-on-Trent, in Nottinghamshire, Eng ...

, founded in 1531 by the diplomat Thomas Magnus, lies close to the town centre. The Newark Academy

The Newark Academy (formerly The Grove School) is a mixed secondary school in Balderton, Nottinghamshire, England.

Admissions

The Newark Academy offers GCSEs, BTECs and Cambridge Nationals as programmes of study for pupils.

History Former gr ...

is in neighbouring Balderton (previously The Grove School). It underwent a £25 million rebuild in 2016 after a long campaign. In 2020 the Suthers School opened, providing a new Secondary School for Newark

The town's several primary schools include a new school in the Middlebeck development on the town's southern edge, opened in September 2021.

Newark College, part of the Lincoln College, Lincolnshire

Lincoln College is a predominantly further education college based in the City of Lincoln, England.

The college's main site is on Monks Road (B1308), specifically to the north, and to the south of Lindum Hill ( A15). It was formerly known as ...

Group, is situated on Friary Road, Newark, where it is home to the School of Musical Instrument Crafts. The School, which opened in 1972, has courses to train craftspeople to make and repair guitars, violins, and woodwind instruments, and to tune and restore pianos.

Economy

British Sugar PLC runs a mill on the outskirts that opened in 1921. It has 130 permanent employees and processes 1.6 million tonnes of sugar beet produced by about 800 UK growers, at an average distance of 28 miles from the factory. Of the output, 250,000 tonnes are processed and supplied to food and drink manufacturers in the UK and across Europe. At the heart of the Newark factory's operations is a combined heat and power (CHP) plant, with boilers fuelled by natural gas to meet the site's steam and electricity requirements and contribute to the grid enough power for 800 homes. The installation is rated under the government CHP environmental quality-assurance scheme. Other major employers are a bearings factory (part of the NSK group) with some 200 employees, and Laurens Patisseries, part of the food groupBakkavör

Bakkavör is an international food manufacturing company specialising in fresh prepared foods. The group's head office is in London, England. It is listed on the London Stock Exchange, and was part of the FTSE 250 index from early 2018 to 2020.

...

since May 2006, which bought it for £130 million. It employs over 1,000. In 2007, Currys

Currys (branded as Currys PC World between 2010 and 2021) is an electrical retailer and aftercare service provider operating in the United Kingdom and Ireland, specialising in white goods, consumer electronics, computers and mobile phones.

E ...

opened a £30 million national distribution centre next to the A17 near the A46 roundabout, and moved its national distribution centre there in 2005, with over 1,400 staff employed at the site at peak times. Flowserve, formerly Ingersoll Dresser Pumps, has a manufacturing facility in the town. Project Telecom in Brunel Drive was bought by Vodafone

Vodafone Group plc () is a British multinational telecommunications company. Its registered office and global headquarters are in Newbury, Berkshire, England. It predominantly operates services in Asia, Africa, Europe, and Oceania.

, Vod ...

in 2003 for a reported £163 million. Since 1985, Newark has been host to the biggest antiques outlet in Europe, the Newark International Antiques and Collectors Fair, held bi-monthly at Newark Showground. Newark has plentiful antique shops and centres.

Culture

Newark hosts NewarkRugby Union

Rugby union, commonly known simply as rugby, is a close-contact team sport that originated at Rugby School in the first half of the 19th century. One of the two codes of rugby football, it is based on running with the ball in hand. In it ...

Football Club, whose players have included Dusty Hare, John Wells, Greig Tonks

Greig Tonks (born 20 May 1989) is a Scottish former rugby union player who played for London Irish in the position of Fullback, Centre or Fly-half. He is currently a coach at Rams.

Career

Born in Pretoria, South Africa, Tonks moved to Engl ...

and Tom Ryder. The town has a leisure centre in Bowbridge Road, opened in 2016.

Newark and Sherwood Concert Band, with over 50 regular players, has performed at numerous area events in the last few years. Also based in Newark are the Royal Air Force Music Charitable Trust and Lincolnshire Chamber Orchestra.

The Palace Theatre in Appletongate is Newark's main entertainment venue, offering drama, live music, dance and film.

The National Civil War Centre and Newark Museum, next to the Palace Theatre in Appletongate in the town centre, opened in 2015 to interpret Newark's part in the English Civil War in the 17th century and explore its wider implications.

The district was ranked in a survey reported in 2020 as one of the best places to live in the UK.

Landmarks and treasures

Grade I listed

In the United Kingdom, a listed building or listed structure is one that has been placed on one of the four statutory lists maintained by Historic England in England, Historic Environment Scotland in Scotland, in Wales, and the Northern I ...

building notable for its tower and octagonal spire ( high), the tallest in the county for a church. It was heavily restored in the mid-19th century by Sir George Gilbert Scott

Sir George Gilbert Scott (13 July 1811 – 27 March 1878), known as Sir Gilbert Scott, was a prolific English Gothic Revival architect, chiefly associated with the design, building and renovation of churches and cathedrals, although he started ...

. The reredos was added by Sir Ninian Comper

Sir John Ninian Comper (10 June 1864 – 22 December 1960) was a Scottish architect; one of the last of the great Gothic Revival architects.

His work almost entirely focused on the design, restoration and embellishment of churches, and the des ...

.

* Newark Castle was built by the Trent by Alexander of Lincoln

Alexander of Lincoln (died February 1148) was a medieval English Bishop of Lincoln, a member of an important administrative and ecclesiastical family. He was the nephew of Roger of Salisbury, a Bishop of Salisbury and Chancellor of England und ...

, the Bishop of Lincoln

The Bishop of Lincoln is the ordinary (diocesan bishop) of the Church of England Diocese of Lincoln in the Province of Canterbury.

The present diocese covers the county of Lincolnshire and the unitary authority areas of North Lincolnshire and ...

in 1123, who established it as a mint

MiNT is Now TOS (MiNT) is a free software alternative operating system kernel for the Atari ST system and its successors. It is a multi-tasking alternative to TOS and MagiC. Together with the free system components fVDI device drivers, XaAE ...

. Of the original Norman stronghold, the chief remains are the gate-house

A gatehouse is a type of fortified gateway, an entry control point building, enclosing or accompanying a gateway for a town, religious house, castle, manor house, or other fortification building of importance. Gatehouses are typically the mos ...

, a crypt

A crypt (from Latin '' crypta'' " vault") is a stone chamber beneath the floor of a church or other building. It typically contains coffins, sarcophagi, or religious relics.

Originally, crypts were typically found below the main apse of a c ...

and the tower at the south-west angle. King John died there on the night of 18 October 1216. In the reign of Edward III

Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from January 1327 until his death in 1377. He is noted for his military success and for restoring r ...

it was being used as a state prison. In the English Civil War it was garrisoned for Charles I and endured three sieges. Its dismantling was begun in 1646, after the royalist surrender.

*The 16th-century Governor's House, named after Sir Richard Willis, Castle Governor in the English Civil War, is in Stodman Street. Now housing a bread shop and cafe, it is a Grade I listed building.

Newark Torc

The Newark Torc, a silver and goldIron Age

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age ( Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age ( Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostly ...

torc

A torc, also spelled torq or torque, is a large rigid or stiff neck ring in metal, made either as a single piece or from strands twisted together. The great majority are open at the front, although some had hook and ring closures and a few had ...

, was the first found in Nottinghamshire. It resembles that of the Snettisham Hoard

The Snettisham Hoard or ''Snettisham Treasure'' is a series of discoveries of Iron Age precious metal, found in the Snettisham area of the English county of Norfolk between 1948 and 1973.

Iron age hoard

The hoard consists of metal, jet and ...

. Uncovered in 2005, it occupies a field on the town's outskirts, and in 2008 was acquired by Newark and Sherwood District Council. The torc was displayed at the British Museum in London until the opening of the National Civil War Centre and Newark Museum in May 2015. It is now shown in the museum galleries.

Churches and other religious sites

Newark's churches include the Grade I listed

Newark's churches include the Grade I listed parish church

A parish church (or parochial church) in Christianity is the church which acts as the religious centre of a parish. In many parts of the world, especially in rural areas, the parish church may play a significant role in community activities, ...

, St Mary Magdalene

Mary Magdalene (sometimes called Mary of Magdala, or simply the Magdalene or the Madeleine) was a woman who, according to the four canonical gospels, traveled with Jesus as one of his followers and was a witness to his crucifixion and

resurre ...

. Other Anglican parish churches include Christ Church in Boundary Road and St Leonard's in Lincoln Road. The Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

Holy Trinity Church was consecrated in 1979. Other places of worship include three Methodist

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a group of historically related denominations of Protestant Christianity whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John Wesley. George Whitefield and John's ...

churches, the Baptist

Baptists form a major branch of Protestantism distinguished by baptizing professing Christian believers only ( believer's baptism), and doing so by complete immersion. Baptist churches also generally subscribe to the doctrines of soul c ...

Church in Albert Street, and the Church of Promise, founded in 2007.

In 2014 the Newark Odinist Temple, a Grade II listed building

In the United Kingdom, a listed building or listed structure is one that has been placed on one of the four statutory lists maintained by Historic England in England, Historic Environment Scotland in Scotland, in Wales, and the Northern I ...

in Bede House Lane, was consecrated according to the rites of the Odinist Fellowship, making it the first heathen temple operating in England in modern times.

Transport

Newark is acommuter town

A commuter town is a populated area that is primarily residential rather than commercial or industrial. Routine travel from home to work and back is called commuting, which is where the term comes from. A commuter town may be called by many ...

, with many residents travelling to Lincoln and Nottingham and even London.

Newark has two railway stations. The East Coast Main Line

The East Coast Main Line (ECML) is a electrified railway between London and Edinburgh via Peterborough, Doncaster, York, Darlington, Durham and Newcastle. The line is a key transport artery on the eastern side of Great Britain running b ...

serves Newark North Gate railway station with links to in about an hour and a quarter, and north to , Hull

Hull may refer to:

Structures

* Chassis, of an armored fighting vehicle

* Fuselage, of an aircraft

* Hull (botany), the outer covering of seeds

* Hull (watercraft), the body or frame of a ship

* Submarine hull

Mathematics

* Affine hull, in affi ...

, Newcastle upon Tyne

Newcastle upon Tyne ( RP: , ), or simply Newcastle, is a city and metropolitan borough in Tyne and Wear, England. The city is located on the River Tyne's northern bank and forms the largest part of the Tyneside built-up area. Newcastle is ...

and . Newark Castle railway station on the – – line provides cross-country regional links. The two meet at the last flat crossing in Britain. Grade separation

In civil engineering (more specifically highway engineering), grade separation is a method of aligning a junction of two or more surface transport axes at different heights (grades) so that they will not disrupt the traffic flow on other tr ...

has been proposed.

The main roads of Newark include the A1 and A46 as bypasses. The A17 runs east to King's Lynn

King's Lynn, known until 1537 as Bishop's Lynn and colloquially as Lynn, is a port and market town in the borough of King's Lynn and West Norfolk in the county of Norfolk, England. It is located north of London, north-east of Peterborough, nor ...

, Norfolk

Norfolk () is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in East Anglia in England. It borders Lincolnshire to the north-west, Cambridgeshire to the west and south-west, and Suffolk to the south. Its northern and eastern boundaries are the Nor ...

, and the A616 north to Huddersfield

Huddersfield is a market town in the Kirklees district in West Yorkshire, England. It is the administrative centre and largest settlement in the Kirklees district. The town is in the foothills of the Pennines. The River Holme's confluence i ...

, West Yorkshire

West Yorkshire is a metropolitan and ceremonial county in the Yorkshire and Humber Region of England. It is an inland and upland county having eastward-draining valleys while taking in the moors of the Pennines. West Yorkshire came into exi ...

. The bus-service providers include Stagecoach in Lincolnshire

Stagecoach Lincolnshire is a bus company, formerly known as Lincolnshire RoadCar, which runs services throughout Lincolnshire.

Stagecoach in Lincolnshire is the trading name of the Lincolnshire Road Car Company Limited, which is a subsidiary of ...

("Newark busabouttown"), Marshalls and Travel Wright, under Nottinghamshire County Council control,

Media

The town's weekly ''Newark Advertiser

The ''Newark Advertiser'' is a British regional newspaper, owned by Iliffe Media, for the town of Newark-on-Trent and surrounding areas.

History

The Advertiser had its beginnings in 1847, when printer William Tomlinson of Stodman Street is ...

'', founded in 1854, is owned by Newark Advertiser Co Ltd, which also publishes local newspapers in Southwell and Bingham.

The community statio''Radio Newark''

began broadcasting on 107.8 FM in May 2015, after three successful trials in 2014 and 2015. It replaced a community station, Boundary Sound, which ceased broadcasting in 2011.

Notable people

Armed forces

*Gonville Bromhead

Major Gonville Bromhead VC (29 August 1845 – 9 February 1891) was a British Army officer and recipient of the Victoria Cross, the highest award for valour in the face of the enemy that can be awarded to members of the British armed forces. H ...

(1845–1891), army officer and Victoria Cross

The Victoria Cross (VC) is the highest and most prestigious award of the British honours system. It is awarded for valour "in the presence of the enemy" to members of the British Armed Forces and may be awarded posthumously. It was previousl ...

recipient educated at Magnus Grammar School

Magnus, meaning "Great" in Latin, was used as cognomen of Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus in the first century BC. The best-known use of the name during the Roman Empire is for the fourth-century Western Roman Emperor Magnus Maximus. The name gained wi ...

* John Cartwright (1740–1824), naval officer, militia major and political reformer educated in Newark.

Fine arts

* William Caparne (1855–1940) – botanical artist and horticulturalist born in Newark *William Cubley

William Harold Cubley (9 October 1816 – 1896) was an English painter of landscapes and portraits in the tradition of Sir Joshua Reynolds. He studied with Sir William Beechey, and was an important early influence on Sir William Nicholson an ...

(1816–1896) – artist settled in Newark

* William Nicholson (1872–1949) – painter and illustrator born in Newark

Literature

* George Allen (1832–1907) – engraver and publisher born in Newark *John Barnard

John Edward Barnard (born 4 May 1946, Wembley, London) is an English engineer and racing car designer. Barnard is credited with the introduction of two new designs into Formula One: the carbon fibre composite chassis first seen in with McLar ...

(died 1683) – biographer and religious writer, who died in Newark

*Cornelius Brown

Cornelius Brown (5 March 1852 in Lowdham, Nottinghamshire – 4 November 1907) was an English journalist and historian. In 1874, 22-year-old Brown became editor of the Newark Advertiser in nearby Newark-on-Trent. Over the next 33 years, he wr ...

(1852–1907) – journalist and historian, ''Newark Advertiser

The ''Newark Advertiser'' is a British regional newspaper, owned by Iliffe Media, for the town of Newark-on-Trent and surrounding areas.

History

The Advertiser had its beginnings in 1847, when printer William Tomlinson of Stodman Street is ...

''

*Henry Constable

Henry Constable (1562 – 9 October 1613) was an English poet, known particularly for ''Diana'', one of the first English sonnet sequences. In 1591 he converted to Catholicism, and lived in exile on the continent for some years. He returned to E ...

(1562–1613) – poet (early sonnet

A sonnet is a poetic form that originated in the poetry composed at the Court of the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II in the Sicilian city of Palermo. The 13th-century poet and notary Giacomo da Lentini is credited with the sonnet's inventio ...

eer) born in Newark

* Winifred Gales (1761–1839) – novelist and memoirist

* T. W. Robertson (1829–1871) – playwright and innovative stage director

Music

*John Blow

John Blow (baptised 23 February 1649 – 1 October 1708) was an English composer and organist of the Baroque period. Appointed organist of Westminster Abbey in late 1668,Ian Burden

Ian Charles Burden (born 24 December 1957) is an English musician who played keyboards and bass guitar with The Human League, initially as a session musician, and later full-time, between 1981 and 1987.

He attended The King's School in Pe ...

(born 1957) – keyboard player with the Human League

The Human League are an English synth-pop band formed in Sheffield in 1977. Initially an experimental electronic outfit, the group signed to Virgin Records in 1979 and later attained widespread commercial success with their third album ''Dare' ...

*Jay McGuiness

James "Jay" McGuiness (born 24 July 1990) is a British singer, songwriter and actor best known as a vocalist with boy band The Wanted. In 2015, partnered with Aliona Vilani, he won the 13th series of BBC's ''Strictly Come Dancing''.

In recen ...

(born 1990) – band singer with The Wanted

The Wanted are a British-Irish boy band consisting of group members Max George, Siva Kaneswaran, Jay McGuiness and Nathan Sykes and, until his death in 2022, Tom Parker. The group was formed in 2009 and signed a worldwide contract to ...

Politics and government

* Richard Alexander (1934–2008) – Conservative politician * Ted Bishop (1920–1984) – Labour politician, created Baron Bishopston of Newark in the County of Nottinghamshire *William Robert Bousfield

William Robert Bousfield (12 January 1854 – 16 July 1943) was a British lawyer, Conservative politician and scientist.

Biography

Bousfield was the son of Edward Tenney Bousfield, an engineer, and his wife Charlotte Eliza Collins, who was a n ...

(1854–1943) – Conservative politician, lawyer and psychologist born in Newark

*Sir Bryce Chudleigh Burt

Sir Bryce Chudleigh Burt (29 April 1881 – 2 January 1943) was an administrator in India during the British Raj. He was awarded a knighthood on 1 January 1936, having previously been made a Companion of the Order of the Indian Empire in 1930 an ...

(1881–1943) – administrator in the British Raj

The British Raj (; from Hindi ''rāj'': kingdom, realm, state, or empire) was the rule of the British Crown on the Indian subcontinent;

*

* it is also called Crown rule in India,

*

*

*

*

or Direct rule in India,

* Quote: "Mill, who was him ...

born in Newark

* John Cartwright (1740–1824) – politician and preacher, attended Newark Grammar School.

*Robert Constable

Sir Robert Constable (c. 1478 – 6 July 1537) was a member of the English Tudor gentry. He helped Henry VII to defeat the Cornish rebels at the Battle of Blackheath in 1497. In 1536, when the rising known as the Pilgrimage of Grace broke out ...

(1522–1591) – parliamentarian and soldier

* Robert Heron (1765–1854) – Whig politician

* Robert Jenrick (born 1982) – Conservative politician, MP for Newark since June 2014

*King John of England

King is the title given to a male monarch in a variety of contexts. The female equivalent is queen, which title is also given to the consort of a king.

*In the context of prehistory, antiquity and contemporary indigenous peoples, the t ...

(1166–1216) – died in Newark.

*Fiona Jones

Fiona Elizabeth Ann Jones (née Hamilton; 27 February 1957 – 28 January 2007) was a Labour Party politician in the United Kingdom. She was elected as a Member of Parliament (MP) for Newark in Labour's landslide victory in the 1997 general e ...

(1957–2007) – Labour politician, MP for Newark

*Patrick Mercer

Patrick John Mercer (born 26 June 1956) is a British author and former politician. He was elected as a Conservative in the 2001 general election, until resigning the party's parliamentary whip in May 2013 following questions surrounding paid ad ...

(born 1956) – Conservative politician, MP for Newark 2001–2014

* Arthur Richardson (1860–1936) – Liberal/Labour politician who attended Magnus Grammar School

Religion

*Alexander of Lincoln

Alexander of Lincoln (died February 1148) was a medieval English Bishop of Lincoln, a member of an important administrative and ecclesiastical family. He was the nephew of Roger of Salisbury, a Bishop of Salisbury and Chancellor of England und ...

(died 1148) – Bishop of Lincoln

The Bishop of Lincoln is the ordinary (diocesan bishop) of the Church of England Diocese of Lincoln in the Province of Canterbury.

The present diocese covers the county of Lincolnshire and the unitary authority areas of North Lincolnshire and ...

, founded a hospital for leper

Leprosy, also known as Hansen's disease (HD), is a long-term infection by the bacteria '' Mycobacterium leprae'' or '' Mycobacterium lepromatosis''. Infection can lead to damage of the nerves, respiratory tract, skin, and eyes. This nerve d ...

s in Newark.

* Annette Cooper (born 1953) – Anglican Archdeacon of Colchester

The Archdeacon of Colchester is a senior ecclesiastical officer in the Diocese of Chelmsford – she or he has responsibilities within her archdeaconry (the Archdeaconry of Colchester) including oversight of church buildings and some supervision, d ...

, educated at Lilley and Stone Girls' High School in Newark

* John Burdett Wittenoom (1788–1855) – pioneer cleric and headmaster in Swan River Colony

The Swan River Colony, also known as the Swan River Settlement, or just Swan River, was a British colony established in 1829 on the Swan River, in Western Australia. This initial settlement place on the Swan River was soon named Perth, and it ...

, Australia, born in Newark

Science and technology

* John Arderne (1307–1392) – notable surgeon, lived in Newark in early life. * Basil Baily (1869–1942) – architect * Francis Clater (1756–1823) – farrier and veterinary writer * Godfrey Hounsfield (1919–2004) – electrical engineer, Nobel Laureate in medicine, inventor of the CT scanner *Rupert Sheldrake

Alfred Rupert Sheldrake (born 28 June 1942) is an English author and parapsychology researcher who proposed the concept of morphic resonance, a conjecture which lacks mainstream acceptance and has been criticized as pseudoscience. He has wor ...

(born 1942) – biochemist and parapsychology

Parapsychology is the study of alleged psychic phenomena ( extrasensory perception, telepathy, precognition, clairvoyance, psychokinesis (also called telekinesis), and psychometry) and other paranormal claims, for example, those related t ...

researcher born in Newark

* Giovanni Francisco Vigani (c. 1650–1712) – chemist from Verona

Verona ( , ; vec, Verona or ) is a city on the Adige River in Veneto, Italy, with 258,031 inhabitants. It is one of the seven provincial capitals of the region. It is the largest city municipality in the region and the second largest in nor ...

, who first settled in Newark in 1682

*Frederick Smeeton Williams

Frederick Smeeton Williams (1829 – 26 October 1886) was an English minister in the Congregational church, Congregational Church, best known for his books on the early History of rail transport in Great Britain, history of UK railways.

Bio ...

(1829–1886) – writer on railways

Sports

* David Avanesyan (born 15 August 1988) – professional boxer * Steve Baines (born 1954) – League footballer and referee * Phil Crampton (born 1970) – professional alpinist and high-altitude mountaineer * Craig Dudley (born 1979) – professional association footballer * Harry Hall (born 1893 – death date unknown) – professional association footballer * Willie Hall (1912–1967) – Notts County, Tottenham Hotspur and England footballer * Dusty Hare (born 1952) – rugby union international * Phil Joslin (born 1959) – league football referee * Mary King (born Thomson, 1961) – Olympic equestrian sportswoman *Sam McMahon

Samantha Jane McMahon (born 11 December 1967) is a former Australian politician who was a Senator for the Northern Territory between the 2019 federal election and the 2022 federal election. McMahon is a member of the Liberal Democratic Party ...

(born 1976) – professional association footballer

* Shane Nicholson (born 1970) – league footballer

* Henry Slater (1839–1905) – first-class cricketer born in Newark

* Mark Smalley (born 1965) – professional association footballer born in Newark

* William Streets (born 1772, fl. 1792–1803) – cricketer

* Chad Sugden (born 27 April 1994) – professional boxer born in Newark

Stage and screen

*Arthur Leslie

Arthur Leslie Scottorn Broughton (8 December 1899 – 30 June 1970), better known as Arthur Leslie, was a British actor and playwright, best known for original character of public house landlord Jack Walker in television soap '' Coronation St ...

(1899–1970) – actor and playwright, born in Newark

* Norman Pace (born 1953) – actor and comedian

*Terence Longdon

Terence Longdon (14 May 1922 – 23 April 2011) was an English actor.

Biography

Born Hubert Tuelly Longdon in Newark-on-Trent, Nottinghamshire, England. During World War II, Longdon was a pilot with the Fleet Air Arm, protecting Atlantic conv ...

(1922–2011) – screen actor

*Donald Wolfit

Sir Donald Wolfit, KBE (born Donald Woolfitt; Harwood, Ronald"Wolfit, Sir Donald (1902–1968)" ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', Oxford University Press, September 2004; online edn, January 2008; accessed 14 July 2009 20 April 1902 ...

(1902–1968) – Shakespearean actor

*Toby Kebbell

Tobias Alistair Patrick Kebbell''Births, Marriages & Deaths: Toby is married to Arielle Wyatt. They got married in 2020 and they have one child together. Index of England & Wales, 1916–2005.''; at ancestry.com (born 9 July 1982) is an English ...

(born 1982) – actor educated at the Grove School"Toby Kebbell Drops Out and Tunes InRetrieved 3 December 2017

*

Nathan Foad

Nathan Foad (born December 30, 1992) is an English actor and writer known for ''Newark, Newark'' and ''Our Flag Means Death''.

Career

Foad graduated from Guildford School of Acting. Afterwards, he built his career as a comedy writer, before ...

(born 1992) – actor and writer

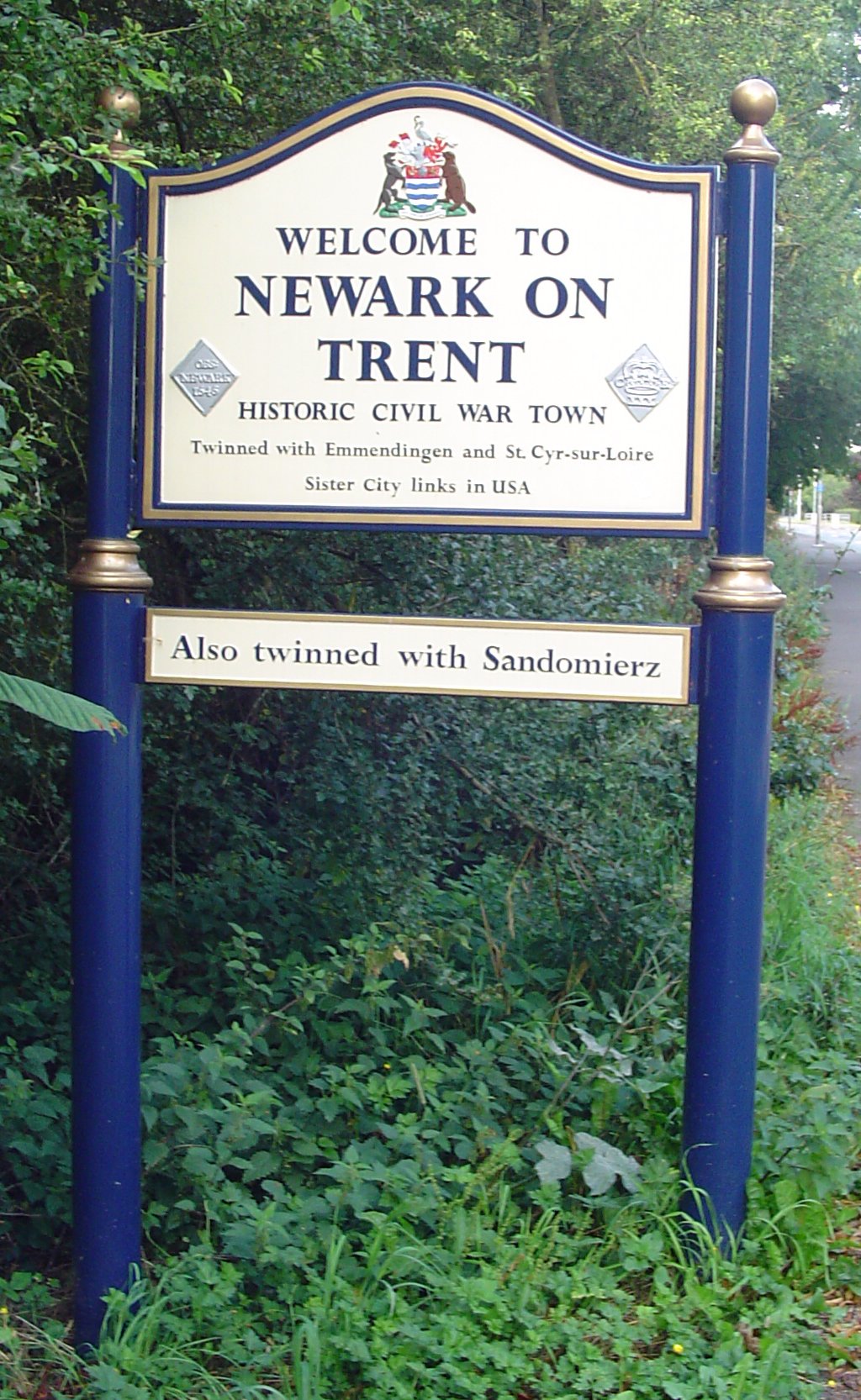

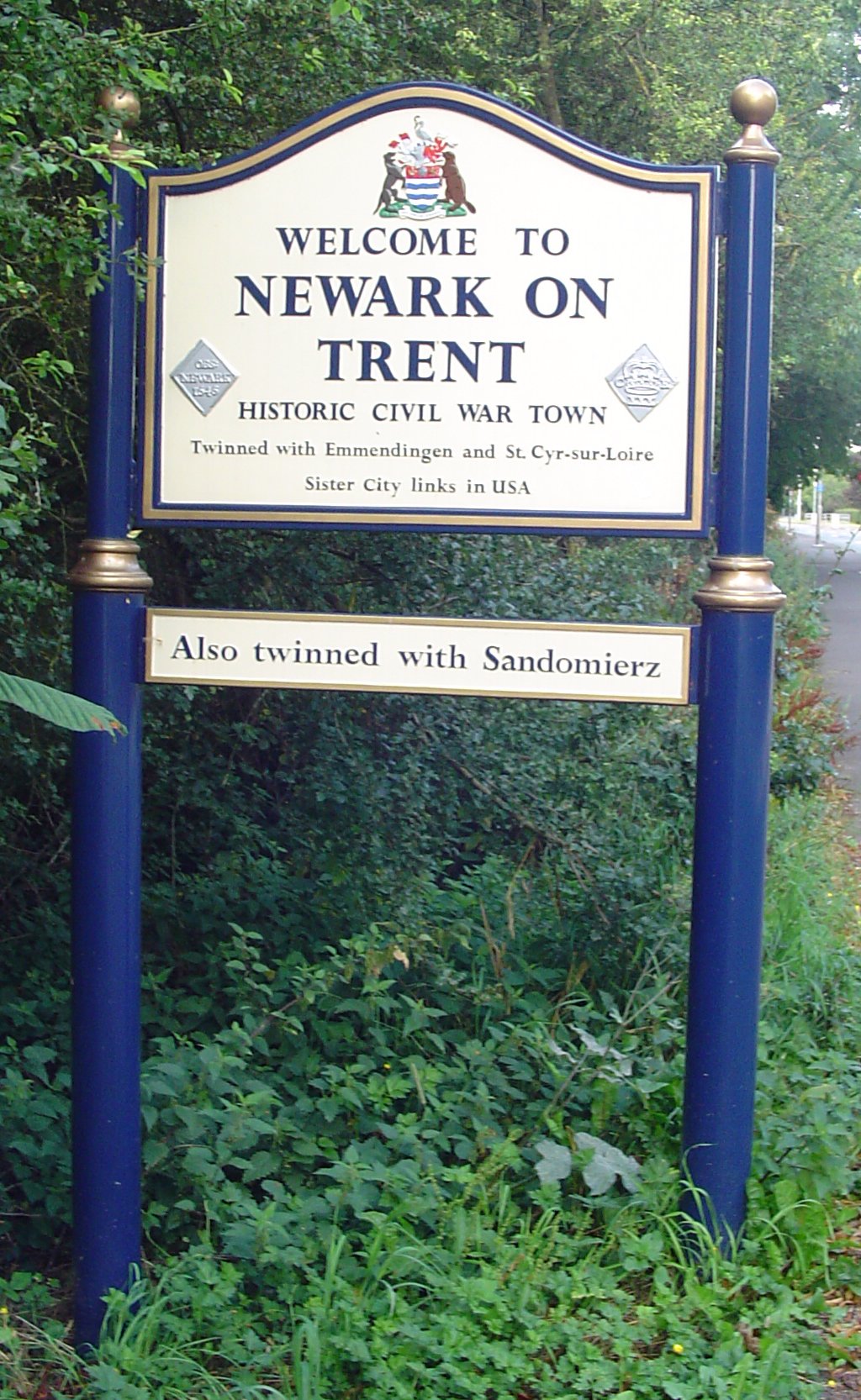

Twin towns

Since 1984 Newark has been twinned with: *Emmendingen

Emmendingen (; Low Alemannic: ''Emmedinge'') is a town in Baden-Württemberg, capital of the district Emmendingen of Germany. It is located at the Elz River, north of Freiburg im Breisgau. The town contains more than 26,000 residents, which ...

, Germany

* Saint-Cyr-sur-Loire

Saint-Cyr-sur-Loire (, literally ''Saint-Cyr on Loire'') is a commune in the department of Indre-et-Loire in central France.

It is located northwest of Tours on the other side of the Loire. It is the third largest city in the Indre-et-Loire depa ...

, France

* Sandomierz

Sandomierz (pronounced: ; la, Sandomiria) is a historic town in south-eastern Poland with 23,863 inhabitants (as of 2017), situated on the Vistula River in the Sandomierz Basin. It has been part of Świętokrzyskie Voivodeship (Holy Cross Prov ...

, Poland

Arms

References

;Bibliography * * *External links

Newark Town Council

Community carnival for Newark * {{DEFAULTSORT:Newark-On-Trent Towns in Nottinghamshire Market towns in Nottinghamshire Newark and Sherwood