Nestorian stele on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Xi'an Stele or the Jingjiao Stele ( zh, c=景教碑, p= Jǐngjiào bēi), sometimes translated as the "Nestorian Stele," is a Tang Chinese

The heading on the stone, Chinese for Memorial of the Propagation in China of the Luminous Religion from Daqin (, abbreviated ). An even more abbreviated version of the title, (Jǐngjiào bēi, "The Stele of the Luminous Religion"), in its Wade-Giles form, Ching-chiao-pei or Chingchiaopei, was used by some Western writers to refer to the stele as well.

The name of the stele can also be translated as ''A Monument Commemorating the Propagation of the Ta-Chin Luminous Religion in the Middle Kingdom'' (the church referred to itself as "The Luminous Religion of Daqin", Daqin being the Chinese language term for the

The heading on the stone, Chinese for Memorial of the Propagation in China of the Luminous Religion from Daqin (, abbreviated ). An even more abbreviated version of the title, (Jǐngjiào bēi, "The Stele of the Luminous Religion"), in its Wade-Giles form, Ching-chiao-pei or Chingchiaopei, was used by some Western writers to refer to the stele as well.

The name of the stele can also be translated as ''A Monument Commemorating the Propagation of the Ta-Chin Luminous Religion in the Middle Kingdom'' (the church referred to itself as "The Luminous Religion of Daqin", Daqin being the Chinese language term for the

The Xi'an Stele attracted the attention of some anti-Christian, Protestant anti-Catholic, or Catholic anti-Jesuit groups in the 17th century, who argued that the stone was a fake or that the inscriptions had been modified by the

The Xi'an Stele attracted the attention of some anti-Christian, Protestant anti-Catholic, or Catholic anti-Jesuit groups in the 17th century, who argued that the stone was a fake or that the inscriptions had been modified by the

Numerous Christian gravestones have also been found in China in the

Numerous Christian gravestones have also been found in China in the

Part 1

(1895) *

Part 2

(1897) *

Part 3

(1902) Some of the volumes can also be foun

on archive.org

* * . Originally published by: Hutchinson & Co, London, 1924. *

* ttp://itsee.bham.ac.uk/online/stele/index.htm Large photograph of a rubbing of the stele from University of Birmingham (scroll to bottom of page)br>"The Jesus Messiah of Xi'an"

― translation and exposition of doctrinal passages in the stele text. From B. Vermander (ed.), ''Le Christ Chinois, Héritages et espérance'' (Paris: Desclée de Brouwer, 1998).

Japanese text. * SIR E. A. WALLIS BUDGE, KT.,

(1928) - contains reproductions of early photographs of the stele where it stood in the early 20th century (from Havret etc.)

Nestorian Stele – Inscription: A slice of Christian history from China. Australian Museum

{{coord missing, China 8th-century inscriptions Monuments and memorials in China Church of the East in China Chinese steles Xi'an 8th-century Christian texts Nestorian texts

stele

A stele ( ),Anglicized plural steles ( ); Greek plural stelai ( ), from Greek language, Greek , ''stēlē''. The Greek plural is written , ''stēlai'', but this is only rarely encountered in English. or occasionally stela (plural ''stelas'' or ...

erected in 781 that documents 150 years of early Christianity in China

Christianity in China has been present since at least the 3rd century, and it has gained a significant amount of influence during the last 200 years.

While Christianity may have existed in China before the 3rd century, evidence of its existe ...

. It is a limestone block high with text in both Chinese and Syriac Syriac may refer to:

*Syriac language, an ancient dialect of Middle Aramaic

*Sureth, one of the modern dialects of Syriac spoken in the Nineveh Plains region

* Syriac alphabet

** Syriac (Unicode block)

** Syriac Supplement

* Neo-Aramaic languages a ...

describing the existence of Christian communities in several cities in northern China. It reveals that the initial Church of the East

The Church of the East ( syc, ܥܕܬܐ ܕܡܕܢܚܐ, ''ʿĒḏtā d-Maḏenḥā'') or the East Syriac Church, also called the Church of Seleucia-Ctesiphon, the Persian Church, the Assyrian Church, the Babylonian Church or the Nestorian C ...

had met recognition by the Tang Emperor Taizong, due to efforts of the Christian missionary Alopen

Alopen (, ; also "Aleben", "Aluoben", "Olopen," "Olopan," or "Olopuen") is the first recorded Assyrian Christian missionary to have reached China, during the Tang dynasty. He was a missionary from the Church of the East (also known as the "Nestori ...

in 635. According to the Stele, Alopen and his fellow Syriac Syriac may refer to:

*Syriac language, an ancient dialect of Middle Aramaic

*Sureth, one of the modern dialects of Syriac spoken in the Nineveh Plains region

* Syriac alphabet

** Syriac (Unicode block)

** Syriac Supplement

* Neo-Aramaic languages a ...

missionaries came to China from Daqin (the Eastern Roman Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantino ...

) in the ninth year of Emperor Taizong (Tai Tsung) (635), bringing sacred books and images. The Church of the East monk Adam

Adam; el, Ἀδάμ, Adám; la, Adam is the name given in Genesis 1-5 to the first human. Beyond its use as the name of the first man, ''adam'' is also used in the Bible as a pronoun, individually as "a human" and in a collective sense as " ...

(Jingjing in Chinese) composed the text on the stele. Buried in 845, probably during religious suppression

Religious persecution is the systematic mistreatment of an individual or a group of individuals as a response to their religious beliefs or affiliations or their lack thereof. The tendency of societies or groups within societies to alienate o ...

, the stele was not rediscovered until 1625. It is now in the Stele Forest

The Stele Forest or Beilin Museum is a museum for steles and stone sculptures in Beilin District in Xi'an, Northwest China. The museum, which is housed in a former Confucian Temple, has housed a growing collection of Steles since 1087. By 194 ...

in Xi'an

Xi'an ( , ; ; Chinese: ), frequently spelled as Xian and also known by other names, is the capital of Shaanxi Province. A sub-provincial city on the Guanzhong Plain, the city is the third most populous city in Western China, after Chongqi ...

.

Discovery

The stele is thought to have been buried in 845, during a campaign of anti-Buddhist persecution, which also affected these Christians. The stele was unearthed in the lateMing dynasty

The Ming dynasty (), officially the Great Ming, was an Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty of China, ruling from 1368 to 1644 following the collapse of the Mongol Empire, Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Ming dynasty was the last ort ...

(between 1623 and 1625) beside Chongren Temple () outside of Xi'an

Xi'an ( , ; ; Chinese: ), frequently spelled as Xian and also known by other names, is the capital of Shaanxi Province. A sub-provincial city on the Guanzhong Plain, the city is the third most populous city in Western China, after Chongqi ...

.

According to the account by the Jesuit

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders ...

Alvaro Semedo, the workers who found the stele immediately reported the find to the governor, who soon visited the monument, and had it installed on a pedestal, under a protective roof, requesting the nearby Buddhist monastery to care for it.Mungello, p. 168

The newly discovered stele attracted attention of local intellectuals. It was Zhang Gengyou ( Wade-Giles: Chang Keng-yu) who first identified the text as Christian in content. Zhang, who had been aware of Christianity through Matteo Ricci

Matteo Ricci, SJ (; la, Mattheus Riccius; 6 October 1552 – 11 May 1610), was an Italian Jesuit priest and one of the founding figures of the Jesuit China missions. He created the , a 1602 map of the world written in Chinese characters. ...

, and who himself may have been Christian, sent a copy of the stele's Chinese text to his Christian friend, Leon Li Zhizao in Hangzhou

Hangzhou ( or , ; , , Standard Chinese, Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ), also Chinese postal romanization, romanized as Hangchow, is the capital and most populous city of Zhejiang, China. It is located in the northwestern part of the prov ...

, who in his turn published the text and told the locally based Jesuits about it.

Alvaro Semedo was the first European to visit the stele (some time between 1625 and 1628). Nicolas Trigault

Nicolas Trigault (1577–1628) was a Jesuit, and a missionary in China. He was also known by his latinised name Nicolaus Trigautius or Trigaultius, and his Chinese name Jin Nige ().

Life and work

Born in Douai (then part of the County of Flanders ...

's Latin translation of the monument's inscription soon made its way in Europe, and was apparently first published in a French translation, in 1628. Portuguese and Italian translations, and a Latin re-translation, were soon published as well. Semedo's account of the monument's discovery was published in 1641, in his ''Imperio de la China''.Mungello, p. 169

Early Jesuits attempted to claim that the stele was erected by a historical community of Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

* Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

* Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a let ...

s in China, called Nestorianism

Nestorianism is a term used in Christian theology and Church history to refer to several mutually related but doctrinarily distinct sets of teachings. The first meaning of the term is related to the original teachings of Christian theologian ...

a heresy

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important relig ...

, and claimed that it was Catholics who first brought Christianity to China. But later historians and writers admitted that it was indeed from the Church of the East

The Church of the East ( syc, ܥܕܬܐ ܕܡܕܢܚܐ, ''ʿĒḏtā d-Maḏenḥā'') or the East Syriac Church, also called the Church of Seleucia-Ctesiphon, the Persian Church, the Assyrian Church, the Babylonian Church or the Nestorian C ...

and not Roman Catholic.

The first publication of the original Chinese and Syriac text of the inscription in Europe is attributed to Athanasius Kircher

Athanasius Kircher (2 May 1602 – 27 November 1680) was a German Jesuit scholar and polymath who published around 40 major works, most notably in the fields of comparative religion, geology, and medicine. Kircher has been compared to fe ...

. ''China Illustrata'' edited by Kircher (1667) included a reproduction of the original inscription in Chinese characters,

Romanization

Romanization or romanisation, in linguistics, is the conversion of text from a different writing system to the Roman (Latin) script, or a system for doing so. Methods of romanization include transliteration, for representing written text, a ...

of the text, and a Latin translation. This was perhaps the first sizeable Chinese text made available in its original form to the European public. A sophisticated Romanization system, reflecting Chinese tones, used to transcribe the text, was the one developed earlier by Matteo Ricci

Matteo Ricci, SJ (; la, Mattheus Riccius; 6 October 1552 – 11 May 1610), was an Italian Jesuit priest and one of the founding figures of the Jesuit China missions. He created the , a 1602 map of the world written in Chinese characters. ...

's collaborator Lazzaro Cattaneo (1560–1640).

The work of the transcription and translation was carried out by Michał Boym and two young Chinese Christians who visited Rome in the 1650s and 1660s: Boym's traveling companion Andreas Zheng () and, later, another person who signed in Latin as "Matthaeus Sina". D.E. Mungello suggests that Matthaeus Sina may have been the person who traveled overland from China to Europe with Johann Grueber.Mungello, p. 167

Content

The heading on the stone, Chinese for Memorial of the Propagation in China of the Luminous Religion from Daqin (, abbreviated ). An even more abbreviated version of the title, (Jǐngjiào bēi, "The Stele of the Luminous Religion"), in its Wade-Giles form, Ching-chiao-pei or Chingchiaopei, was used by some Western writers to refer to the stele as well.

The name of the stele can also be translated as ''A Monument Commemorating the Propagation of the Ta-Chin Luminous Religion in the Middle Kingdom'' (the church referred to itself as "The Luminous Religion of Daqin", Daqin being the Chinese language term for the

The heading on the stone, Chinese for Memorial of the Propagation in China of the Luminous Religion from Daqin (, abbreviated ). An even more abbreviated version of the title, (Jǐngjiào bēi, "The Stele of the Luminous Religion"), in its Wade-Giles form, Ching-chiao-pei or Chingchiaopei, was used by some Western writers to refer to the stele as well.

The name of the stele can also be translated as ''A Monument Commemorating the Propagation of the Ta-Chin Luminous Religion in the Middle Kingdom'' (the church referred to itself as "The Luminous Religion of Daqin", Daqin being the Chinese language term for the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Roman Republic, Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings aro ...

in the 1st and 2nd centuries AD, and in later eras also used to refer to the Syriac Christian churches).

Authorship

The stele was erected on January 7, 781 (" Year of the Greeks 1092" in the inscription), at the imperial capital city ofChang'an

Chang'an (; ) is the traditional name of Xi'an. The site had been settled since Neolithic times, during which the Yangshao culture was established in Banpo, in the city's suburbs. Furthermore, in the northern vicinity of modern Xi'an, Qin ...

(modern-day Xi'an

Xi'an ( , ; ; Chinese: ), frequently spelled as Xian and also known by other names, is the capital of Shaanxi Province. A sub-provincial city on the Guanzhong Plain, the city is the third most populous city in Western China, after Chongqi ...

), or at nearby Zhouzhi County

Zhouzhi County () is a county under the administration of Xi'an, the capital of Shaanxi province, China. It is the most spacious but least densely populated county-level division of Xi'an, and also contains the city's southernmost and westernmost ...

. The calligraphy

Calligraphy (from el, link=y, καλλιγραφία) is a visual art related to writing. It is the design and execution of lettering with a pen, ink brush, or other writing instrument. Contemporary calligraphic practice can be defined ...

was by Lü Xiuyan (), and the content was composed by the Church of the East monk Jingjing in the four- and six-character

Character or Characters may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Literature

* ''Character'' (novel), a 1936 Dutch novel by Ferdinand Bordewijk

* ''Characters'' (Theophrastus), a classical Greek set of character sketches attributed to The ...

euphemistic style (大秦寺僧㬌淨述, "Related by Jingjing, monk of the Daqin Temple"). A gloss in Syriac identifies Jingjing with "Adam, priest, chorepiscopus and ''papash'' of Sinistan" (ܐܕܡ ܩܫܝܫܐ ܘܟܘܪܐܦܝܣܩܘܦܐ ܘܦܐܦܫܝ ܕܨܝܢܝܣܬܐܢ, ''Adam qshisha w'kurapisqupa w'papash d'Sinistan''). Although the term ''papash'' (literally "pope") is unusual and the normal Syriac name for China is Beth Sinaye, not Sinistan, there is no reason to doubt that Adam was the metropolitan of the Church of the East ecclesiastical province of Beth Sinaye, created a half-century earlier during the reign of Patriarch Sliba-zkha Sliba-zkha (the name means 'the cross has conquered' in Syriac) was patriarch of the Church of the East from 714 to 728.

Sources

Brief accounts of Sliba-zkha's patriarchate are given in the ''Ecclesiastical Chronicle'' of the Jacobite writer Bar ...

(714–28). A Syriac dating formula refers to the Church of the East patriarch Hnanisho II Hnanisho II (born c.715) was patriarch of the Church of the East between 773 and 780. His name, sometimes spelled Ananjesu or Khnanishu, means 'mercy of Jesus'.

Sources

Brief accounts of Hnanisho's patriarchate are given in the ''Ecclesiastical ...

(773–780), news of whose death several months earlier had evidently not yet reached the Church of the East of Chang'an. In fact, the reigning Church of the East patriarch in January 781 was Timothy I Timothy I may refer to:

* Pope Timothy I of Alexandria, Pope of Alexandria & Patriarch of the See of St. Mark in 378–384

* Timothy I of Constantinople

Timothy I or Timotheus I (? – 1 April 518) was a Christian priest who was appointed Patria ...

(780–823), who had been consecrated in Baghdad

Baghdad (; ar, بَغْدَاد , ) is the capital of Iraq and the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. It is located on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon and the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesiphon ...

on 7 May 780. The names of several higher clergy (one bishop, two chorepiscopi and two archdeacons) and around seventy monks or priests are listed. The names of the higher clergy appear on the front of the stone while those of the priests and monks are inscribed in rows along the narrow sides of the stone, in both Syriac and Chinese. In some cases, the Chinese names are phonetically close to the Syriac originals, but in many other cases, they bear little resemblance to them. Some of the Church of the East monks had distinctive Persian names (such as Isadsafas, Gushnasap), suggesting that they might have come from Fars or elsewhere in Persia, but most of them had common Christian names or the kind of compound Syriac name (such as Abdisho, 'servant of Jesus') much in vogue among all Church of the East Christians. In such cases, it is impossible to guess at their place of origin.

Content

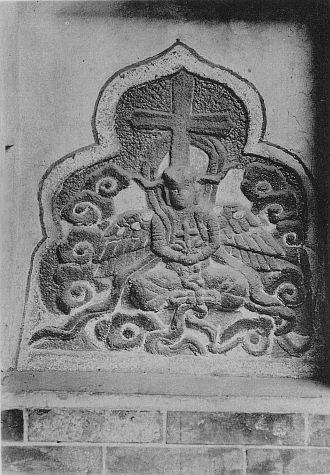

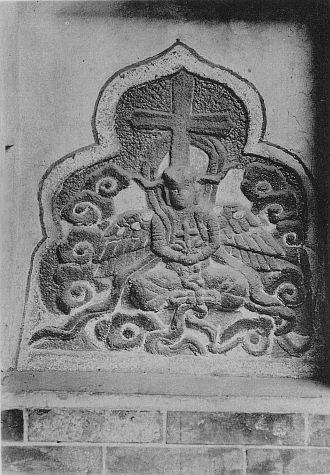

On top of the tablet, there is a cross. Below this headpiece is a long Chinese inscription, consisting of around 1,900 Chinese characters, sometimes glossed in Syriac (several sentences amounting to about 50 Syriac words). CallingGod

In monotheistic thought, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. Swinburne, R.G. "God" in Honderich, Ted. (ed)''The Oxford Companion to Philosophy'', Oxford University Press, 1995. God is typically ...

"Veritable Majesty", the text refers to Genesis

Genesis may refer to:

Bible

* Book of Genesis, the first book of the biblical scriptures of both Judaism and Christianity, describing the creation of the Earth and of mankind

* Genesis creation narrative, the first several chapters of the Book of ...

, the cross

A cross is a geometrical figure consisting of two intersecting lines or bars, usually perpendicular to each other. The lines usually run vertically and horizontally. A cross of oblique lines, in the shape of the Latin letter X, is termed a s ...

, and baptism

Baptism (from grc-x-koine, βάπτισμα, váptisma) is a form of ritual purification—a characteristic of many religions throughout time and geography. In Christianity, it is a Christian sacrament of initiation and adoption, almost ...

. It also pays tribute to missionaries and benefactors of the church, who are known to have arrived in China by 640. The text contains the name of an early missionary, Alopen

Alopen (, ; also "Aleben", "Aluoben", "Olopen," "Olopan," or "Olopuen") is the first recorded Assyrian Christian missionary to have reached China, during the Tang dynasty. He was a missionary from the Church of the East (also known as the "Nestori ...

. The tablet describes the "Illustrious Religion" and emphasizes the Trinity

The Christian doctrine of the Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the central dogma concerning the nature of God in most Christian churches, which defines one God existing in three coequal, coeternal, consubstantial divine persons: God th ...

and the Incarnation

Incarnation literally means ''embodied in flesh'' or ''taking on flesh''. It refers to the conception and the embodiment of a deity or spirit in some earthly form or the appearance of a god as a human. If capitalized, it is the union of divinit ...

, but there is nothing about Christ's crucifixion or resurrection. Other Chinese elements referred to include a wooden bell, beard, tonsure

Tonsure () is the practice of cutting or shaving some or all of the hair on the scalp as a sign of religious devotion or humility. The term originates from the Latin word ' (meaning "clipping" or "shearing") and referred to a specific practice i ...

, and renunciation. The Syriac proper names for God, Christ and Satan (''Allaha'', ''Mshiha'' and ''Satana'') were rendered phonetically into Chinese. Chinese transliterations were also made of one or two words of Sanskrit

Sanskrit (; attributively , ; nominally , , ) is a classical language belonging to the Indo-Aryan languages, Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in South Asia after its predecessor languages had Trans-cultural diffusion ...

origin such as ''Sphatica'' and ''Dasa

''Dasa'' ( sa, दास, Dāsa) is a Sanskrit word found in ancient Indian texts such as the ''Rigveda'' and '' Arthasastra''. It usually means "enemy" or "servant" but ''dasa'', or ''das'', also means a " servant of God", "devotee," " votary" or ...

''. There is also a Persian word denoting Sunday

Sunday is the day of the week between Saturday and Monday. In most Western countries, Sunday is a day of rest and a part of the weekend. It is often considered the first day of the week.

For most observant adherents of Christianity, Sund ...

.

Yazedbuzid (Yisi in Chinese) helped the Tang dynasty general Guo Ziyi

Guo Ziyi (Kuo Tzu-i; Traditional Chinese: 郭子儀, Simplified Chinese: 郭子仪, Hanyu Pinyin: Guō Zǐyí, Wade-Giles: Kuo1 Tzu3-i2) (697 – July 9, 781), posthumously Prince Zhōngwǔ of Fényáng (), was a Chinese military general and po ...

militarily crush the Sogdian-Turk led An Lushan rebellion

The An Lushan Rebellion was an uprising against the Tang dynasty of China towards the mid-point of the dynasty (from 755 to 763), with an attempt to replace it with the Yan dynasty. The rebellion was originally led by An Lushan, a general off ...

, with Yisi personally acting as a military commander and Yisi and the Church of the East were rewarded by the Tang dynasty with titles and positions as described in the Xi'an Stele.

Debate

The Xi'an Stele attracted the attention of some anti-Christian, Protestant anti-Catholic, or Catholic anti-Jesuit groups in the 17th century, who argued that the stone was a fake or that the inscriptions had been modified by the

The Xi'an Stele attracted the attention of some anti-Christian, Protestant anti-Catholic, or Catholic anti-Jesuit groups in the 17th century, who argued that the stone was a fake or that the inscriptions had been modified by the Jesuits

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders = ...

who served in the Ming Court. The three most prominent early skeptics were the German-Dutch Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their n ...

scholar Georg Horn (born 1620) (''De originibus Americanis'', 1652), the German historian Gottlieb Spitzel (1639–1691) (''De re literaria Sinensium commentarius'', 1660), and the Dominican missionary Domingo Navarrete (1618–1686) (''Tratados historicos, politicos, ethicos, y religiosos de la monarchia de China'', 1676). Later, Navarrete's point of view was taken up by French Jansenists

Jansenism was an Early modern period, early modern Christian theology, theological movement within Catholicism, primarily active in the Kingdom of France, that emphasized original sin, human Total depravity, depravity, the necessity of divine g ...

and Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778) was a French Enlightenment writer, historian, and philosopher. Known by his '' nom de plume'' M. de Voltaire (; also ; ), he was famous for his wit, and his criticism of Christianity—e ...

.Mungello, p. 170-171

By the 19th century, the debate had become less sectarian and more scholarly. Notable skeptics included Karl Friedrich Neumann

Karl Friedrich Neumann (28 December 1793 – 17 March 1870) was a German orientalist.

Life

Neumann was born, under the name of Bamberger, at Reichsmannsdorf, near Bamberg. He studied philosophy and philology at Heidelberg, Munich and Götting ...

, Stanislas Julien

Stanislas Aignan Julien (13 April 179714 February 1873) was a French sinologist who served as the Chair of Chinese at the Collège de France for over 40 years and was one of the most academically respected sinologists in French scholarship.

J ...

, Edward E. Salisbury and Charles Wall. Ernest Renan

Joseph Ernest Renan (; 27 February 18232 October 1892) was a French Orientalist and Semitic scholar, expert of Semitic languages and civilizations, historian of religion, philologist, philosopher, biblical scholar, and critic. He wrote in ...

initially had "grave doubts", but eventually changed his mind in the light of later scholarship, in favor of the stele's genuineness. The defenders included some non-Jesuit scholars, such as Alexander Wylie, James Legge

James Legge (; 20 December 181529 November 1897) was a Scottish linguist, missionary, sinologist, and translator

who was best known as an early translator of Classical Chinese texts into English. Legge served as a representative of the Londo ...

, and Jean-Pierre-Guillaume Pauthier, although the most substantive work in defense of the stele's authenticity – the three-volume ''La stèle chrétienne de Si-ngan-fou'' (1895 to 1902) was authored by the Jesuit scholar Henri Havret (1848–1902).

Paul Pelliot

Paul Eugène Pelliot (28 May 187826 October 1945) was a French Sinologist and Orientalist best known for his explorations of Central Asia and his discovery of many important Chinese texts such as the Dunhuang manuscripts.

Early life and career ...

(1878–1945) did an extensive amount of research on the stele, which, however, was only published posthumously, in 1984 (a second edition, revised by Forte was then published in 1996). His and Havret's works are still regarded as the two "standard books" on the subject.

Modern location, and replicas

Since the late 19th century a number of European scholars opined in favor of somehow getting the stele out of China and into theBritish Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docum ...

or some other "suitable" location (e.g., Frederic H. Balfour in his letter published in ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper '' The Sunday Times'' ( ...

'' in early 1886). The Danish scholar and adventurer Frits Holm

Frits Vilhelm Holm (c. 1881

, ''The New York Times'', Ju ...

came to , ''The New York Times'', Ju ...

Xi'an

Xi'an ( , ; ; Chinese: ), frequently spelled as Xian and also known by other names, is the capital of Shaanxi Province. A sub-provincial city on the Guanzhong Plain, the city is the third most populous city in Western China, after Chongqi ...

in 1907 planning to take the monument for himself to Europe.. Holm's original report can be found in , and also in more popular form in Local authorities prevented him and moved the stele, complete with its tortoise

Tortoises () are reptiles of the family Testudinidae of the order Testudines (Latin: ''tortoise''). Like other turtles, tortoises have a shell to protect from predation and other threats. The shell in tortoises is generally hard, and like oth ...

, from its location near Chongren Temple to Xi'an's Beilin Museum (Forest of Steles Museum).

Holm had an exact copy of the stele made for him and had the replica stele shipped to New York, planning to sell it to the Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Metropolitan Museum of Art of New York City, colloquially "the Met", is the largest art museum in the Americas. Its permanent collection contains over two million works, divided among 17 curatorial departments. The main building at 1000 ...

. The museum's director Caspar Purdon Clarke

Sir Caspar Purdon Clarke (21 December 1846 – 29 March 1911) was an English architect and museum director.

Early years

Born in 1846, Clarke was the second son of Edward Marmaduke Clarke and Mary Agnes Close. He was educated at Gaultier's Sch ...

, however, was less than enthusiastic about purchasing "so large a stone ... of no artistic value". Nonetheless, the replica stele was exhibited in the museum ("on loan" from Mr. Holm) for about 10 years. Eventually, in 1917 some Mr. George Leary, a wealthy New Yorker, purchased the replica stele and sent it to Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus ( legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

, as a gift to the Pope. A full-sized replica cast from that replica is on permanent display in the Bunn Intercultural Center on the campus of Georgetown University

Georgetown University is a private research university in the Georgetown neighborhood of Washington, D.C. Founded by Bishop John Carroll in 1789 as Georgetown College, the university has grown to comprise eleven undergraduate and graduate ...

(Washington, D.C.).

The original Xi'an Stele remains in the Forest of Steles. It is now exhibited in the museum's Room Number 2, and is the first stele on the left after the entry. When the official list of Chinese cultural relics forbidden to be exhibited abroad

The list of Chinese cultural relics forbidden to be exhibited abroad (Chinese: 禁止出境展览文物; pinyin: Jìnzhǐ Chūjìng Zhǎnlǎn Wénwù) comprises a list of antiquities and archaeological artifacts held by various museums and other in ...

was promulgated in 2003, the stele was included into this short list of particularly valuable and important items.

Other copies of the stele and its tortoise can be found near Xi'an Daqin Pagoda

The Daqin Pagoda () is a Buddhist pagoda in Zhouzhi County of Xi'an (formerly Chang'an), Shaanxi Province, China, located about two kilometres to the west of Louguantai temple. The pagoda has been claimed as a Church of the East from the Tang Dyna ...

, on Mount Kōya

is a large temple settlement in Wakayama Prefecture, Japan to the south of Osaka. In the strictest sense, ''Mount Kōya'' is the mountain name ( sangō) of Kongōbu-ji Temple, the ecclesiastical headquarters of the Kōyasan sect of Shingon B ...

in Japan, and, in Tianhe Church

Christian Church of Guangzhou Tianhe (), also known as Tianhe Church (), is a Christian TSPM Church in Guangzhou, China. It is located at No. 16-20 Daguan Middle Road, Tianhe District, and hence its name. It is considered the largest church in G ...

, Guangzhou

Guangzhou (, ; ; or ; ), also known as Canton () and Chinese postal romanization, alternatively romanized as Kwongchow or Kwangchow, is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Guangdong Provinces of China, province in South China, sou ...

.

Other early Christian monuments in China

Numerous Christian gravestones have also been found in China in the

Numerous Christian gravestones have also been found in China in the Xinjiang

Xinjiang, SASM/GNC: ''Xinjang''; zh, c=, p=Xīnjiāng; formerly romanized as Sinkiang (, ), officially the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (XUAR), is an autonomous region of the People's Republic of China (PRC), located in the northwes ...

region, Quanzhou

Quanzhou, alternatively known as Chinchew, is a prefecture-level port city on the north bank of the Jin River, beside the Taiwan Strait in southern Fujian, China. It is Fujian's largest metropolitan region, with an area of and a popul ...

and elsewhere from a somewhat later period. There are also two much later stelae (from 960 and 1365) presenting a curious mix of Christian and Buddhist aspects, which are preserved at the site of the former Monastery of the cross in the Fangshan District

Fangshan District () is situated in the southwest of Beijing, away from downtown Beijing. It has an area of and a population of 814,367 (2000 Census). The district is divided into 8 subdistricts, 14 towns, and 6 townships.

The district administ ...

, near Beijing

}

Beijing ( ; ; ), Chinese postal romanization, alternatively romanized as Peking ( ), is the Capital city, capital of the China, People's Republic of China. It is the center of power and development of the country. Beijing is the world's Li ...

.

In 2006, a mortuary stone pillar with Church of the East inscriptions was discovered in Luoyang

Luoyang is a city located in the confluence area of Luo River and Yellow River in the west of Henan province. Governed as a prefecture-level city, it borders the provincial capital of Zhengzhou to the east, Pingdingshan to the southeast, Nanyan ...

, the Nestorian pillar of Luoyang. Erected and engraved in 815, the inscriptions give partial details surrounding the background of a Sogdian Christian community living in Luoyang.

In popular culture

* In the 20th episode of ''The Longest Day in Chang'an

''The Longest Day in Chang'an'' () is a 2019 Chinese historical suspense drama directed by Cao Dun and written by Paw Studio. The series stars Lei Jiayin and Jackson Yee. It is based on the novel of the same name by Ma Boyong. ''The Longest Day i ...

'', the Monk Jingde () hands a missionary

A missionary is a member of a Religious denomination, religious group which is sent into an area in order to promote its faith or provide services to people, such as education, literacy, social justice, health care, and economic development.Tho ...

leaflet to Tan Qi ( Rayzha Alimjan), which contains text taken from the inscription of the Xi'an Stele.

See also

*Church of the East in China

The Church of the East (also known as the Nestorian Church) historically had a presence in China during two periods: first from the 7th through the 10th century in the Tang dynasty, when it was known as ''Jingjiao'' ( zh, t=景教, w=Ching3-chiao4 ...

* Jingjiao Documents

* Adam (Jingjing)

* Nestorian pillar of Luoyang

* Painting of a Christian figure

*Murals from the Christian temple at Qocho

The murals from the Christian temple at Qocho (german: Wandbilder aus einem christlichen Tempel, Chotscho) are three Church of the East mural fragments—''Palm Sunday'', ''Repentance'' and ''Entry into Jerusalem''—discovered by the German Tur ...

* Central Asian objects of Northern Wei tombs

References

Further reading

* Henri Havret sj, ''La stèle chrétienne de Si Ngan-fou'', Parts 1–3. Full text (was) available at Gallica: *Part 1

(1895) *

Part 2

(1897) *

Part 3

(1902) Some of the volumes can also be foun

on archive.org

* * . Originally published by: Hutchinson & Co, London, 1924. *

External links

* ttp://itsee.bham.ac.uk/online/stele/index.htm Large photograph of a rubbing of the stele from University of Birmingham (scroll to bottom of page)br>"The Jesus Messiah of Xi'an"

― translation and exposition of doctrinal passages in the stele text. From B. Vermander (ed.), ''Le Christ Chinois, Héritages et espérance'' (Paris: Desclée de Brouwer, 1998).

Japanese text. * SIR E. A. WALLIS BUDGE, KT.,

(1928) - contains reproductions of early photographs of the stele where it stood in the early 20th century (from Havret etc.)

Nestorian Stele – Inscription: A slice of Christian history from China. Australian Museum

{{coord missing, China 8th-century inscriptions Monuments and memorials in China Church of the East in China Chinese steles Xi'an 8th-century Christian texts Nestorian texts