Nelson's Pillar on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Nelson's Pillar (also known as the Nelson Pillar or simply the Pillar) was a large granite column capped by a statue of

The redevelopment of

The redevelopment of

On 21 October 1805, a Royal Naval fleet commanded by Vice Admiral Lord Nelson defeated the combined fleets of the French and Spanish navies in the

On 21 October 1805, a Royal Naval fleet commanded by Vice Admiral Lord Nelson defeated the combined fleets of the French and Spanish navies in the

By 1830, rising nationalist sentiment in Ireland made it likely that the Pillar was "the Ascendancy's last hurrah"—Kennedy observes that it probably could not have been built at any later date. Nevertheless, the monument often attracted favourable comment from visitors; in 1842 the writer

By 1830, rising nationalist sentiment in Ireland made it likely that the Pillar was "the Ascendancy's last hurrah"—Kennedy observes that it probably could not have been built at any later date. Nevertheless, the monument often attracted favourable comment from visitors; in 1842 the writer  In 1882 the Moore Street Market and Dublin City Improvement Act was passed by the Westminster parliament, overriding the trust and giving the Corporation authority to resite the Pillar, but subject to a strict timetable, within which the city authorities found it impossible to act. The Act lapsed and the Pillar remained; a similar attempt, with the same result, was made in 1891. Not all Dubliners favoured demolition; some businesses considered the Pillar to be the city's focal point, and the tramway company petitioned for its retention as it marked the central tram terminus. "In many ways", says Fallon, "the pillar had become part of the fabric of the city". Kennedy writes: "A familiar and very large if rather scruffy piece of the city's furniture, it was ''The'' Pillar, Dublin's Pillar rather than Nelson's Pillar ... it was also an outing, an experience". The Dublin sculptor John Hughes invited students at the Metropolitan School of Art to "admire the elegance and dignity" of Kirk's statue, "and the beauty of the silhouette".

In 1894 there were some significant alterations to the Pillar's fabric. The original entry on the west side, whereby visitors entered the pedestal by a flight of steps taking them down below street level, was replaced by a new ground level entrance on the south side, with a grand porch. The whole monument was surrounded by heavy iron railings. In the new century, despite the growing nationalism within Dublin—80 per cent of the Corporation's councillors were nationalists of some description—the pillar was liberally decorated with flags and streamers to mark the 1905 Trafalgar centenary. The changing political atmosphere had long been signalled by the arrival in Sackville Street of further monuments, all celebrating distinctively Irish heroes, in what the historian Yvonne Whelan describes as defiance of the British Government, a "challenge in stone". Between the 1860s and 1911, Nelson was joined by monuments to

In 1882 the Moore Street Market and Dublin City Improvement Act was passed by the Westminster parliament, overriding the trust and giving the Corporation authority to resite the Pillar, but subject to a strict timetable, within which the city authorities found it impossible to act. The Act lapsed and the Pillar remained; a similar attempt, with the same result, was made in 1891. Not all Dubliners favoured demolition; some businesses considered the Pillar to be the city's focal point, and the tramway company petitioned for its retention as it marked the central tram terminus. "In many ways", says Fallon, "the pillar had become part of the fabric of the city". Kennedy writes: "A familiar and very large if rather scruffy piece of the city's furniture, it was ''The'' Pillar, Dublin's Pillar rather than Nelson's Pillar ... it was also an outing, an experience". The Dublin sculptor John Hughes invited students at the Metropolitan School of Art to "admire the elegance and dignity" of Kirk's statue, "and the beauty of the silhouette".

In 1894 there were some significant alterations to the Pillar's fabric. The original entry on the west side, whereby visitors entered the pedestal by a flight of steps taking them down below street level, was replaced by a new ground level entrance on the south side, with a grand porch. The whole monument was surrounded by heavy iron railings. In the new century, despite the growing nationalism within Dublin—80 per cent of the Corporation's councillors were nationalists of some description—the pillar was liberally decorated with flags and streamers to mark the 1905 Trafalgar centenary. The changing political atmosphere had long been signalled by the arrival in Sackville Street of further monuments, all celebrating distinctively Irish heroes, in what the historian Yvonne Whelan describes as defiance of the British Government, a "challenge in stone". Between the 1860s and 1911, Nelson was joined by monuments to

The Pillar's fate was sealed when Dublin Corporation issued a "dangerous building" notice. The trustees agreed that the stump should be removed. A last-minute request by the

The Pillar's fate was sealed when Dublin Corporation issued a "dangerous building" notice. The trustees agreed that the stump should be removed. A last-minute request by the

For more than twenty years the site stood empty, while various campaigns sought to fill the space. In 1970 the Arthur Griffith Society suggested a monument to

For more than twenty years the site stood empty, while various campaigns sought to fill the space. In 1970 the Arthur Griffith Society suggested a monument to

A later writer,

Austin Clarke's 1957 poem "Nelson's Pillar, Dublin" scorns the various schemes to remove the monument and concludes "Let him watch the sky/ With those who rule. Stone eye/ And telescopes can prove/ Our blessings are above". In

Nelson Pillar

50th anniversary commemoration account, including numerous Pillar images taken before and after the bombing (Old Dublin Town)

personal eyewitness account of the students with the head of the Pillar's Nelson statue at Kilkenny Strand (Pól Ó Duibhir)

The night Nelson's Pillar fell and changed Dublin

includes photograph of the controlled demolition (''The Irish Times'')

Nelson Monument Blasted

10 March 1966 news reel report (British Pathé)

Nelson Pillar Remains Demolished

14 March 1966 news reel report (British Pathé) {{Authority control Columns related to the Napoleonic Wars Monumental columns in the Republic of Ireland Demolished buildings and structures in Dublin History of Dublin (city) Improvised explosive device bombings in the Republic of Ireland Buildings and structures completed in 1809 Buildings and structures demolished in 1966 Monuments and memorials to Horatio Nelson Neoclassical architecture in Ireland Outdoor sculptures in Ireland Destroyed sculptures Removed statues

Horatio Nelson

Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson, 1st Viscount Nelson, 1st Duke of Bronte (29 September 1758 – 21 October 1805) was a British flag officer in the Royal Navy. His inspirational leadership, grasp of strategy, and unconventional tactics brought abo ...

, built in the centre of what was then Sackville Street (later renamed O'Connell Street

O'Connell Street () is a street in the centre of Dublin, Ireland, running north from the River Liffey. It connects the O'Connell Bridge to the south with Parnell Street to the north and is roughly split into two sections bisected by Henry S ...

) in Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of the Wicklow Mountains range. At the 2016 ...

, Ireland. Completed in 1809 when Ireland was part of the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and No ...

, it survived until March 1966, when it was severely damaged by explosives planted by Irish republicans

Irish republicanism ( ga, poblachtánachas Éireannach) is the political movement for the unity and independence of Ireland under a republic. Irish republicans view British rule in any part of Ireland as inherently illegitimate.

The develo ...

. Its remnants were later destroyed by the Irish Army

The Irish Army, known simply as the Army ( ga, an tArm), is the land component of the Defence Forces (Ireland), Defence Forces of Republic of Ireland, Ireland.The Defence Forces are made up of the Permanent Defence Forces – the standing bran ...

.

The decision to build the monument was taken by Dublin Corporation

Dublin Corporation (), known by generations of Dubliners simply as ''The Corpo'', is the former name of the city government and its administrative organisation in Dublin since the 1100s. Significantly re-structured in 1660-1661, even more sign ...

in the euphoria following Nelson's victory at the Battle of Trafalgar

The Battle of Trafalgar (21 October 1805) was a naval engagement between the British Royal Navy and the combined fleets of the French and Spanish Navies during the War of the Third Coalition (August–December 1805) of the Napoleonic Wars (1 ...

in 1805. The original design by William Wilkins was greatly modified by Francis Johnston, on grounds of cost. The statue was sculpted by Thomas Kirk. From its opening on 29 October 1809 the Pillar was a popular tourist attraction, but provoked aesthetic and political controversy from the outset. A prominent city centre monument honouring an Englishman rankled as Irish nationalist

Irish nationalism is a nationalist political movement which, in its broadest sense, asserts that the people of Ireland should govern Ireland as a sovereign state. Since the mid-19th century, Irish nationalism has largely taken the form of cu ...

sentiment grew, and throughout the 19th century there were calls for it to be removed, or replaced with a memorial to an Irish hero.

It remained in the city as most of Ireland became the Irish Free State

The Irish Free State ( ga, Saorstát Éireann, , ; 6 December 192229 December 1937) was a state established in December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921. The treaty ended the three-year Irish War of Independence between the ...

in 1922, and the Republic of Ireland

Ireland ( ga, Éire ), also known as the Republic of Ireland (), is a country in north-western Europe consisting of 26 of the 32 counties of the island of Ireland. The capital and largest city is Dublin, on the eastern side of the island. ...

in 1949. The chief legal barrier to its removal was the trust created at the Pillar's inception, the terms of which gave the trustees a duty in perpetuity to preserve the monument. Successive Irish governments failed to deliver legislation overriding the trust. Although influential literary figures such as W. B. Yeats and Oliver St. John Gogarty

Oliver Joseph St. John Gogarty (17 August 1878 – 22 September 1957) was an Irish poet, author, otolaryngologist, athlete, politician, and well-known conversationalist. He served as the inspiration for Buck Mulligan in James Joyce's novel ...

defended the Pillar on historical and cultural grounds, pressure for its removal intensified in the years preceding the 50th anniversary of the Rising, and its sudden demise was, on the whole, well-received by the public. Although it was widely believed that the action was the work of the Irish Republican Army

The Irish Republican Army (IRA) is a name used by various paramilitary organisations in Ireland throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. Organisations by this name have been dedicated to irredentism through Irish republicanism, the belief that ...

(IRA), the police were unable to identify any of those responsible.

After years of debate and numerous proposals, the site was occupied in 2003 by the Spire of Dublin

The Spire of Dublin, alternatively titled the Monument of Light ( ga, An Túr Solais), is a large, stainless steel, pin-like monument in height, located on the site of the former Nelson's Pillar (and prior to that a statue of William Blakeney) ...

, a slim needle-like structure rising almost three times the height of the Pillar. In 2000, a former republican activist gave a radio interview in which he admitted planting the explosives in 1966, but, after questioning him, the Gardaí decided not to take action. Relics of the Pillar are found in Dublin museums and appear as decorative stonework elsewhere and its memory is preserved in numerous works of Irish literature.

Background

Sackville Street and Blakeney

The redevelopment of

The redevelopment of Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of the Wicklow Mountains range. At the 2016 ...

north of the River Liffey

The River Liffey ( Irish: ''An Life'', historically ''An Ruirthe(a)ch'') is a river in eastern Ireland that ultimately flows through the centre of Dublin to its mouth within Dublin Bay. Its major tributaries include the River Dodder, the Rive ...

began in the early 18th century, largely through the enterprise of the property speculator Luke Gardiner. His best-known work was the transformation in the 1740s of a narrow lane called Drogheda Street, which he demolished and turned into a broad thoroughfare lined with large and imposing town houses. He renamed it Sackville Street, in honour of Lionel Sackville, 1st Duke of Dorset

Lionel Cranfield Sackville, 1st Duke of Dorset (18 January 168810 October 1765) was an English political leader and Lord Lieutenant of Ireland.

Life

He was the son of the 6th Earl of Dorset and 1st Earl of Middlesex, and the former Lady Mary ...

, who served as Lord Lieutenant of Ireland

Lord Lieutenant of Ireland (), or more formally Lieutenant General and General Governor of Ireland, was the title of the chief governor of Ireland from the Williamite Wars of 1690 until the Partition of Ireland in 1922. This spanned the Kin ...

from 1731 to 1737 and from 1751 to 1755. After Gardiner's death in 1755 Dublin's growth continued, with many fine public buildings and grand squares, the city's status magnified by the presence of the Parliament of Ireland

The Parliament of Ireland ( ga, Parlaimint na hÉireann) was the legislature of the Lordship of Ireland, and later the Kingdom of Ireland, from 1297 until 1800. It was modelled on the Parliament of England and from 1537 comprised two chambe ...

for six months of the year. The Acts of Union of 1800, which united Ireland and Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It is ...

under a single Westminster polity, ended the Irish parliament and presaged a period of decline for the city. The historian Tristram Hunt writes: " e capital's dynamism vanished, absenteeism returned and the big houses lost their patrons".

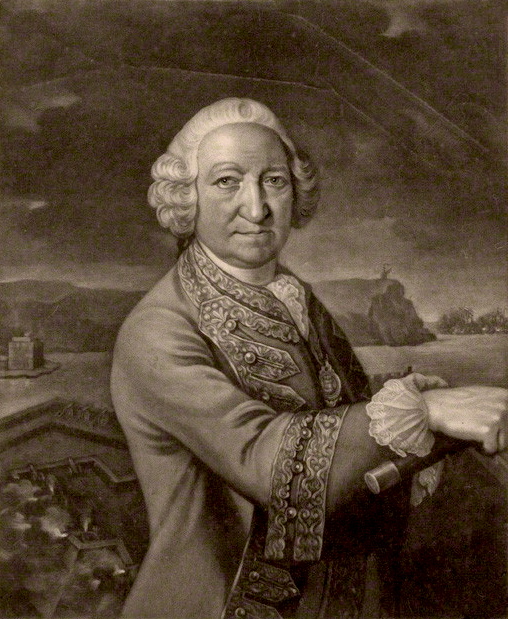

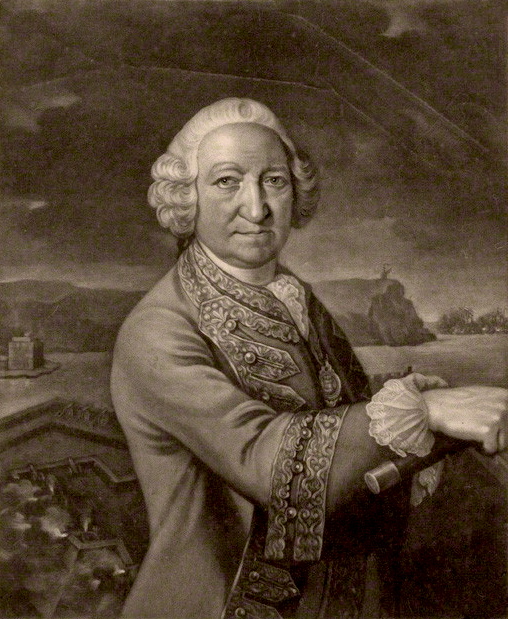

The first monument in Sackville Street was built in 1759 in the location where the Nelson Pillar would eventually stand. The subject was William Blakeney, 1st Baron Blakeney, a Limerick

Limerick ( ; ga, Luimneach ) is a western city in Ireland situated within County Limerick. It is in the province of Munster and is located in the Mid-West which comprises part of the Southern Region. With a population of 94,192 at the 2016 ...

-born army officer whose career extended over more than 60 years and ended with his surrender to the French after the siege of Minorca

The siege of Fort St Philip, also known as the siege of Minorca, took place from 20 April to 29 June 1756 during the Seven Years' War. Ceded to Great Britain in 1714 by Spain following the War of the Spanish Succession, its capture by France thr ...

in 1756. A brass statue sculpted by John van Nost the younger was unveiled on St Patrick's Day

Saint Patrick's Day, or the Feast of Saint Patrick ( ga, Lá Fhéile Pádraig, lit=the Day of the Festival of Patrick), is a cultural and religious celebration held on 17 March, the traditional death date of Saint Patrick (), the foremost patr ...

, 17 March 1759. Donal Fallon, in his history of the Pillar, states that almost from its inception the Blakeney statue was a target for vandalism. Its fate is uncertain; Fallon records that it might have been melted down for cannon, but it had certainly been removed by 1805.

Trafalgar

On 21 October 1805, a Royal Naval fleet commanded by Vice Admiral Lord Nelson defeated the combined fleets of the French and Spanish navies in the

On 21 October 1805, a Royal Naval fleet commanded by Vice Admiral Lord Nelson defeated the combined fleets of the French and Spanish navies in the Battle of Trafalgar

The Battle of Trafalgar (21 October 1805) was a naval engagement between the British Royal Navy and the combined fleets of the French and Spanish Navies during the War of the Third Coalition (August–December 1805) of the Napoleonic Wars (1 ...

. At the height of the battle Nelson was mortally wounded on board his flagship, ; by the time he died later that day, victory was assured.

Nelson had been hailed in Dublin seven years earlier, after the Battle of the Nile

The Battle of the Nile (also known as the Battle of Aboukir Bay; french: Bataille d'Aboukir) was a major naval battle fought between the British Royal Navy and the Navy of the French Republic at Aboukir Bay on the Mediterranean coast off the ...

, as defender of the Harp and Crown, the respective symbols of Ireland and Britain. When news of Trafalgar reached the city on 8 November, there were similar scenes of patriotic celebration, together with a desire that the fallen hero should be commemorated. The mercantile classes had particular reason to be grateful for a victory that restored the freedom of the high seas and removed the threat of a French invasion. Many of the city's population had relatives who had been involved in the battle: up to one-third of the sailors in Nelson's fleet were from Ireland, including around 400 from Dublin itself. In his short account of the Pillar, Dennis Kennedy considers that Nelson would have been regarded in the city as a hero, not just among the Protestant Ascendancy

The ''Protestant Ascendancy'', known simply as the ''Ascendancy'', was the political, economic, and social domination of Ireland between the 17th century and the early 20th century by a minority of landowners, Protestant clergy, and members of th ...

but by many Catholics among the rising middle and professional classes.

The first step towards a permanent memorial to Nelson was taken on 18 November 1805 by the city aldermen

An alderman is a member of a municipal assembly or council in many jurisdictions founded upon English law. The term may be titular, denoting a high-ranking member of a borough or county council, a council member chosen by the elected members the ...

, who after sending a message of congratulation to King George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of the two kingdoms on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Bri ...

, agreed that the erection of a statue would form a suitable tribute to Nelson's memory. On 28 November, after a public meeting had supported this sentiment, a "Nelson committee" was established, chaired by the Lord Mayor. It contained four of the city's Westminster MPs, alongside other city notables including Arthur Guinness

Arthur Guinness ( 172523 January 1803) was an Irish brewer, entrepreneur, and philanthropist. The inventor of Guinness beer, he founded the Guinness Brewery at St. James's Gate in 1759.

Born in Celbridge, County Kildare around 1725, Guinness ...

, the son of the brewery founder. The committee's initial tasks were to decide precisely what form the monument should take and where it should be put. They had also to raise the funds to pay for it.

Inception, design and construction

At its first meeting the Nelson committee established a public subscription, and early in 1806 invited artists and architects to submit design proposals for a monument. No specifications were provided, but the contemporary European vogue in commemorative architecture was for the classical form, typified byTrajan's Column

Trajan's Column ( it, Colonna Traiana, la, Columna Traiani) is a Roman triumphal column in Rome, Italy, that commemorates Roman emperor Trajan's victory in the Dacian Wars. It was probably constructed under the supervision of the architect A ...

in Rome. Monumental columns, or "pillars of victory", were uncommon in Ireland at the time; the Cumberland Column in Birr, County Offaly

Birr (; ga, Biorra, meaning "plain of water") is a town in County Offaly, Ireland. Between 1620 and 1899 it was called Parsonstown, after the Parsons family who were local landowners and hereditary Earls of Rosse. Birr is a designated Irish ...

, erected in 1747, was a rare exception. From the entries submitted, the Nelson committee's choice was that of a young English architect, William Wilkins, then in the early stages of a distinguished career. Wilkins's proposals envisaged a tall Doric column

The Doric order was one of the three orders of ancient Greek and later Roman architecture; the other two canonical orders were the Ionic and the Corinthian. The Doric is most easily recognized by the simple circular capitals at the top of co ...

on a plinth, surmounted by a sculpted Roman galley

A galley is a type of ship that is propelled mainly by oars. The galley is characterized by its long, slender hull, shallow draft, and low freeboard (clearance between sea and gunwale). Virtually all types of galleys had sails that could be u ...

.

The choice of the Sackville Street site was not unanimous. The Wide Streets Commission

The Wide Streets Commission (officially the Commissioners for making Wide and Convenient Ways, Streets and Passages) was established by an Act of Parliament in 1758, at the request of Dublin Corporation, as a body to govern standards on the layou ...

ers were worried about traffic congestion, and argued for a riverside location visible from the sea. Another suggestion was for a seaside position, perhaps Howth Head

Howth Head ( ; ''Ceann Bhinn Éadair'' in Irish) is a peninsula northeast of the city of Dublin in Ireland, within the governance of Fingal County Council. Entry to the headland is at Sutton while the village of Howth and the harbour are on ...

at the entrance to Dublin Bay

Dublin Bay ( ga, Cuan Bhaile Átha Cliath) is a C-shaped inlet of the Irish Sea on the east coast of Ireland. The bay is about 10 kilometres wide along its north–south base, and 7 km in length to its apex at the centre of the city of Dub ...

. The recent presence of the Blakeney statue in Sackville Street, and a desire to arrest the street's decline in the post-parliamentary years, were factors that may have influenced the final selection of that site which, Kennedy says, was the preferred choice of the Lord Lieutenant.

By mid-1807, fundraising was proving difficult; sums raised at that point were well short of the likely cost of erecting Wilkins's column. The committee informed the architect with regret that "means were not placed in their hands to enable them to gratify him, as well as themselves, by executing his design precisely as he had given it". They employed Francis Johnston, architect to the City Board of Works, to make cost-cutting adjustments to Wilkins's scheme. Johnston simplified the design, substituting a large functional block or pedestal for Wilkins's delicate plinth, and replacing the proposed galley with a statue of Nelson. Thomas Kirk, a sculptor from Cork

Cork or CORK may refer to:

Materials

* Cork (material), an impermeable buoyant plant product

** Cork (plug), a cylindrical or conical object used to seal a container

*** Wine cork

Places Ireland

* Cork (city)

** Metropolitan Cork, also known a ...

, was commissioned to provide the statue, to be fashioned from Portland stone

Portland stone is a limestone from the Tithonian stage of the Jurassic period quarried on the Isle of Portland, Dorset. The quarries are cut in beds of white-grey limestone separated by chert beds. It has been used extensively as a building s ...

.

By December 1807 the fund stood at £3,827, far short of the estimated £6,500 required to finance the project. Nevertheless, by the beginning of 1808 the committee felt confident enough to begin the work, and organised the laying of the foundation stone. This ceremony took place on 15 February 1808—the day following the anniversary of Nelson's victory at the Battle of Cape St Vincent in 1797—amid much pomp, in the presence of the new Lord Lieutenant, the Duke of Richmond

Duke of Richmond is a title in the Peerage of England that has been created four times in British history. It has been held by members of the royal Tudor and Stuart families.

The current dukedom of Richmond was created in 1675 for Charles ...

, along with various civic dignitaries and city notables. A memorial plaque eulogising Nelson's Trafalgar victory was attached to the stone. The committee continued to raise money as construction proceeded; when the project was complete in the autumn of 1809, costs totalled £6,856, but contributions had reached £7,138, providing the committee with a surplus of £282.

When finished, the monument complete with its statue rose to a height of . The four sides of the pedestal were engraved with the names and dates of Nelson's greatest victories. A spiral stairway of 168 steps ascended the hollow interior of the column, to a viewing platform immediately beneath the statue. According to the committee's published report, of black limestone

Limestone ( calcium carbonate ) is a type of carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different crystal forms of . Limestone forms wh ...

and of granite

Granite () is a coarse-grained ( phaneritic) intrusive igneous rock composed mostly of quartz, alkali feldspar, and plagioclase. It forms from magma with a high content of silica and alkali metal oxides that slowly cools and solidifies unde ...

had been used to build the column and its pedestal. The Pillar opened to the public on 21 October 1809, on the fourth anniversary of the Battle of Trafalgar; for ten pre-decimal pence, visitors could climb to a viewing platform just below the statue, and enjoy what an early report describes as "a superb panoramic view of the city, the country and the fine bay".

History 1809–1966

1809–1916

The Pillar quickly became a popular tourist attraction; Kennedy writes that "for the next 157 years its ascent was a must on every visitor's list". Yet from the beginning there were criticisms, on both political and aesthetic grounds. The September 1809 issue of the ''Irish Monthly Magazine'', edited by the revolution-minded Walter "Watty" Cox, reported that "our independence has been wrested from us, not by the arms of France but by the gold of England. The statue of Nelson records the glory of a mistress and the transformation of our senate into a discount office". In an early (1818) history of the city of Dublin, the writers express awe at the scale of the monument, but are critical of several of its features: its proportions are described as "ponderous", the pedestal as "unsightly" and the column itself as "clumsy". However, ''Walker's Hibernian Magazine

Walker's ''Hibernian Magazine'', or ''Compendium of Entertaining Knowledge'' was a general-interest magazine published monthly in Dublin, Ireland, from February 1771 to July 1812.Clyde 2003 pp.67–68 Until 1785 it was called ''The Hibernian Mag ...

'' thought the statue was a good likeness of its subject, and that the Pillar's position in the centre of the wide street gave the eye a focal point in what was otherwise "wastes of pavements".

By 1830, rising nationalist sentiment in Ireland made it likely that the Pillar was "the Ascendancy's last hurrah"—Kennedy observes that it probably could not have been built at any later date. Nevertheless, the monument often attracted favourable comment from visitors; in 1842 the writer

By 1830, rising nationalist sentiment in Ireland made it likely that the Pillar was "the Ascendancy's last hurrah"—Kennedy observes that it probably could not have been built at any later date. Nevertheless, the monument often attracted favourable comment from visitors; in 1842 the writer William Makepeace Thackeray

William Makepeace Thackeray (; 18 July 1811 – 24 December 1863) was a British novelist, author and illustrator. He is known for his satirical works, particularly his 1848 novel '' Vanity Fair'', a panoramic portrait of British society, and t ...

noted Nelson "upon a stone-pillar" in the middle of the "exceedingly broad and handsome" Sackville Street: "The Post Office is on his right hand (only it is cut off); and on his left, 'Gresham's' and the 'Imperial Hotel' ". A few years later, the monument was a source of pride to some citizens, who dubbed it "Dublin's Glory" when Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 216 days was longer than that of any previ ...

visited the city in 1849.

Between 1840 and 1843 Nelson's Column

Nelson's Column is a monument in Trafalgar Square in the City of Westminster, Central London, built to commemorate Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson's decisive victory at the Battle of Trafalgar over the combined French and Spanish navies, during whic ...

was erected in London's Trafalgar Square

Trafalgar Square ( ) is a public square in the City of Westminster, Central London, laid out in the early 19th century around the area formerly known as Charing Cross. At its centre is a high column bearing a statue of Admiral Nelson comme ...

. With an overall height of it was taller than its Dublin equivalent and, at £47,000, much more costly to erect. It has no internal staircase or viewing platform. The London column was the subject of an attack during the Fenian dynamite campaign

The Fenian dynamite campaign (or Fenian bombing campaign) was a bombing campaign orchestrated by Irish republicans against the British Empire, between the years 1881 and 1885. The campaign was associated with Fenianism; that is to say the Irish ...

in May 1884, when a quantity of explosives was placed at its base but failed to detonate.

In 1853 the queen attended the Dublin Great Industrial Exhibition, where a city plan was displayed that envisaged the removal of the Pillar. This proved impossible, as since 1811 legal responsibility for the Pillar had been vested in a trust, under the terms of which the trustees were required "to embellish and uphold the monument in perpetuation of the object for which it was subscribed". Any action to remove or resite the Pillar, or replace the statue, required the passage of an Act of Parliament

Acts of Parliament, sometimes referred to as primary legislation, are texts of law passed by the legislative body of a jurisdiction (often a parliament or council). In most countries with a parliamentary system of government, acts of parliamen ...

in London; Dublin Corporation

Dublin Corporation (), known by generations of Dubliners simply as ''The Corpo'', is the former name of the city government and its administrative organisation in Dublin since the 1100s. Significantly re-structured in 1660-1661, even more sign ...

(the city government) had no authority in the matter. No action followed the city plan suggestion, but the following years saw regular attempts to remove the monument. A proposal was made in 1876 by Alderman Peter McSwiney, a former Lord Mayor, to replace the "unsightly structure" with a memorial to the recently deceased Sir John Gray, who had done much to provide Dublin with a clean water supply. The Corporation was unable to advance this idea.

In 1882 the Moore Street Market and Dublin City Improvement Act was passed by the Westminster parliament, overriding the trust and giving the Corporation authority to resite the Pillar, but subject to a strict timetable, within which the city authorities found it impossible to act. The Act lapsed and the Pillar remained; a similar attempt, with the same result, was made in 1891. Not all Dubliners favoured demolition; some businesses considered the Pillar to be the city's focal point, and the tramway company petitioned for its retention as it marked the central tram terminus. "In many ways", says Fallon, "the pillar had become part of the fabric of the city". Kennedy writes: "A familiar and very large if rather scruffy piece of the city's furniture, it was ''The'' Pillar, Dublin's Pillar rather than Nelson's Pillar ... it was also an outing, an experience". The Dublin sculptor John Hughes invited students at the Metropolitan School of Art to "admire the elegance and dignity" of Kirk's statue, "and the beauty of the silhouette".

In 1894 there were some significant alterations to the Pillar's fabric. The original entry on the west side, whereby visitors entered the pedestal by a flight of steps taking them down below street level, was replaced by a new ground level entrance on the south side, with a grand porch. The whole monument was surrounded by heavy iron railings. In the new century, despite the growing nationalism within Dublin—80 per cent of the Corporation's councillors were nationalists of some description—the pillar was liberally decorated with flags and streamers to mark the 1905 Trafalgar centenary. The changing political atmosphere had long been signalled by the arrival in Sackville Street of further monuments, all celebrating distinctively Irish heroes, in what the historian Yvonne Whelan describes as defiance of the British Government, a "challenge in stone". Between the 1860s and 1911, Nelson was joined by monuments to

In 1882 the Moore Street Market and Dublin City Improvement Act was passed by the Westminster parliament, overriding the trust and giving the Corporation authority to resite the Pillar, but subject to a strict timetable, within which the city authorities found it impossible to act. The Act lapsed and the Pillar remained; a similar attempt, with the same result, was made in 1891. Not all Dubliners favoured demolition; some businesses considered the Pillar to be the city's focal point, and the tramway company petitioned for its retention as it marked the central tram terminus. "In many ways", says Fallon, "the pillar had become part of the fabric of the city". Kennedy writes: "A familiar and very large if rather scruffy piece of the city's furniture, it was ''The'' Pillar, Dublin's Pillar rather than Nelson's Pillar ... it was also an outing, an experience". The Dublin sculptor John Hughes invited students at the Metropolitan School of Art to "admire the elegance and dignity" of Kirk's statue, "and the beauty of the silhouette".

In 1894 there were some significant alterations to the Pillar's fabric. The original entry on the west side, whereby visitors entered the pedestal by a flight of steps taking them down below street level, was replaced by a new ground level entrance on the south side, with a grand porch. The whole monument was surrounded by heavy iron railings. In the new century, despite the growing nationalism within Dublin—80 per cent of the Corporation's councillors were nationalists of some description—the pillar was liberally decorated with flags and streamers to mark the 1905 Trafalgar centenary. The changing political atmosphere had long been signalled by the arrival in Sackville Street of further monuments, all celebrating distinctively Irish heroes, in what the historian Yvonne Whelan describes as defiance of the British Government, a "challenge in stone". Between the 1860s and 1911, Nelson was joined by monuments to Daniel O'Connell

Daniel O'Connell (I) ( ga, Dónall Ó Conaill; 6 August 1775 – 15 May 1847), hailed in his time as The Liberator, was the acknowledged political leader of Ireland's Roman Catholic majority in the first half of the 19th century. His mobilizat ...

, William Smith O'Brien

William Smith O'Brien ( ga, Liam Mac Gabhann Ó Briain; 17 October 1803 – 18 June 1864) was an Irish nationalist Member of Parliament (MP) and a leader of the Young Ireland movement. He also encouraged the use of the Irish language. He ...

and Charles Stewart Parnell

Charles Stewart Parnell (27 June 1846 – 6 October 1891) was an Irish nationalist politician who served as a Member of Parliament (MP) from 1875 to 1891, also acting as Leader of the Home Rule League from 1880 to 1882 and then Leader of the ...

, as well as Sir John Gray and the temperance campaigner Father Mathew. Meanwhile, in 1861, after decades of construction, the Wellington Monument in Dublin's Phoenix Park

The Phoenix Park ( ga, Páirc an Fhionnuisce) is a large urban park in Dublin, Ireland, lying west of the city centre, north of the River Liffey. Its perimeter wall encloses of recreational space. It includes large areas of grassland and tre ...

was completed, the foundation stone having been laid in 1817. This vast obelisk, high and square at the base, honoured Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington, Dublin-born and a former Chief Secretary for Ireland

The Chief Secretary for Ireland was a key political office in the British administration in Ireland. Nominally subordinate to the Lord Lieutenant, and officially the "Chief Secretary to the Lord Lieutenant", from the early 19th century un ...

. Unlike the Pillar, Wellington's obelisk has attracted little controversy and has not been the subject of physical attacks.

Easter Rising, April 1916

OnEaster Monday

Easter Monday refers to the day after Easter Sunday in either the Eastern or Western Christian traditions. It is a public holiday in some countries. It is the second day of Eastertide. In Western Christianity, it marks the second day of the O ...

, 24 April 1916, units of the Irish Volunteers

The Irish Volunteers ( ga, Óglaigh na hÉireann), sometimes called the Irish Volunteer Force or Irish Volunteer Army, was a military organisation established in 1913 by Irish nationalists and republicans. It was ostensibly formed in respons ...

and the Irish Citizen Army

The Irish Citizen Army (), or ICA, was a small paramilitary group of trained trade union volunteers from the Irish Transport and General Workers' Union (ITGWU) established in Dublin for the defence of workers' demonstrations from the Dublin ...

seized several prominent buildings and streets in central Dublin, including the General Post Office

The General Post Office (GPO) was the state postal system and telecommunications carrier of the United Kingdom until 1969. Before the Acts of Union 1707, it was the postal system of the Kingdom of England, established by Charles II in 1660. ...

(GPO) in Sackville Street, one of the buildings nearest the Pillar. They set up headquarters at the GPO where they declared an Irish Republic under a provisional government. One of the first recorded actions of the Easter Rising

The Easter Rising ( ga, Éirí Amach na Cásca), also known as the Easter Rebellion, was an armed insurrection in Ireland during Easter Week in April 1916. The Rising was launched by Irish republicans against British rule in Ireland with the ...

occurred near the Pillar when lancer

A lancer was a type of cavalryman who fought with a lance. Lances were used for mounted warfare in Assyria as early as and subsequently by Persia, India, Egypt, China, Greece, and Rome. The weapon was widely used throughout Eurasia during the M ...

s from the nearby Marlborough Street barracks, sent to investigate the disturbance, were fired on from the GPO. They withdrew in confusion, leaving four soldiers and two horses dead.

During the days that followed, Sackville Street and particularly the area around the Pillar became a battleground. According to some histories, insurgents attempted to blow up the Pillar. The accounts are unconfirmed and were disputed by many that fought in the Rising, on the grounds that the Pillar's large base provided them with useful cover as they moved to and from other rebel positions. By Thursday night, British artillery fire had set much of Sackville Street ablaze, but according to the writer Peter De Rosa's account: "On his pillar, Nelson surveyed it all serenely, as though he were lit up by a thousand lamps". The statue was visible against the fiery backdrop from as far as Killiney

Killiney () is an affluent seaside resort and suburb in Dún Laoghaire–Rathdown, Ireland. It lies south of neighbouring Dalkey, east of Ballybrack and Sallynoggin and north of Shankill. The place grew around the 11th century Killiney Churc ...

, away.

By Saturday, when the provisional government finally surrendered, many of the Sackville Street buildings between the Pillar and the Liffey had been destroyed or badly damaged, including the Imperial Hotel that Thackeray had admired. Of the GPO, only the façade remained; against the tide of opinion Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw (26 July 1856 – 2 November 1950), known at his insistence simply as Bernard Shaw, was an Irish playwright, critic, polemicist and political activist. His influence on Western theatre, culture and politics extended from ...

said the demolition of the city's classical architecture scarcely mattered: "What does matter is the Liffey slums have not been demolished". An account in a New York newspaper reported that the Pillar had been lost in the destruction of the street, but it had sustained only minor damage, chiefly bullet marks on the column and statue itself—one shot is said to have taken off Nelson's nose.

Post partition

After the Irish war of Independence 1919–21 and thetreaty

A treaty is a formal, legally binding written agreement between actors in international law. It is usually made by and between sovereign states, but can include international organizations, individuals, business entities, and other legal pers ...

that followed, Ireland was partitioned; Dublin became the capital of the Irish Free State

The Irish Free State ( ga, Saorstát Éireann, , ; 6 December 192229 December 1937) was a state established in December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921. The treaty ended the three-year Irish War of Independence between the ...

, a Dominion

The term ''Dominion'' is used to refer to one of several self-governing nations of the British Empire.

"Dominion status" was first accorded to Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Newfoundland, South Africa, and the Irish Free State at the 1926 I ...

within the British Commonwealth of Nations

The Commonwealth of Nations, simply referred to as the Commonwealth, is a political association of 56 member states, the vast majority of which are former territories of the British Empire. The chief institutions of the organisation are the Co ...

. From December 1922, when the Free State was inaugurated, the Pillar became an issue for the Irish rather than the British government. In 1923, when Sackville Street was again in ruins during the Irish Civil War

The Irish Civil War ( ga, Cogadh Cathartha na hÉireann; 28 June 1922 – 24 May 1923) was a conflict that followed the Irish War of Independence and accompanied the establishment of the Irish Free State, an entity independent from the United ...

, ''The Irish Builder and Engineer'' magazine called the original siting of the Pillar a "blunder" and asked for its removal, a view echoed by the Dublin Citizens Association. The poet William Butler Yeats

William Butler Yeats (13 June 186528 January 1939) was an Irish poet, dramatist, writer and one of the foremost figures of 20th-century literature. He was a driving force behind the Irish Literary Revival and became a pillar of the Irish liter ...

, who had become a member of the Irish Senate, favoured its re-erection elsewhere, but thought it should not, as some wished, be destroyed, because "the life and work of the people who built it are part of our tradition."

Sackville Street was renamed O'Connell Street in 1924. The following year the Dublin Metropolitan Police and the Dublin Civic Survey demanded legislation to allow the Pillar's removal, without success. Pressure continued, and in 1926 ''The Manchester Guardian'' reported that the Pillar was to be taken down, "as it was a hindrance to modern traffic". Requests for action—removal, destruction or the replacement of the statue with that of an Irish hero—continued up to the Second World War and beyond; the main stumbling blocks remained the trustees' strict interpretation of the terms of the trust, and the unwillingness of successive Irish governments to take legislative action. In 1936 the magazine of the ultra-nationalist Blueshirts

The Army Comrades Association (ACA), later the National Guard, then Young Ireland and finally League of Youth, but best known by the nickname the Blueshirts ( ga, Na Léinte Gorma), was a paramilitary organisation in the Irish Free State, founded ...

movement remarked that this inactivity showed a failure in the national spirit: "The conqueror is gone, but the scars which he left remain, and the victim will not even try to remove them".

By 1949 the Irish Free State had evolved into the Republic of Ireland

Ireland ( ga, Éire ), also known as the Republic of Ireland (), is a country in north-western Europe consisting of 26 of the 32 counties of the island of Ireland. The capital and largest city is Dublin, on the eastern side of the island. ...

and left the British Commonwealth, but not all Irish opinion favoured the removal of the Pillar. That year the architectural historian John Harvey called it "a grand work", and argued that without it, "O'Connell Street would lose much of its vitality". Most of the pressure to get rid of it, he said, came from "traffic maniacs who ... fail to visualise the chaos which would result from creating a through current of traffic at this point". In a 1955 radio broadcast Thomas Bodkin, former director of the National Gallery of Ireland

The National Gallery of Ireland ( ga, Gailearaí Náisiúnta na hÉireann) houses the national collection of Irish and European art. It is located in the centre of Dublin with one entrance on Merrion Square, beside Leinster House, and another ...

, praised not only the monument, but Nelson himself: "He was a man of extraordinary gallantry. He lost his eye fighting bravely, and his arm in a similar fashion".

On 29 October 1955, a group of nine students from University College Dublin

University College Dublin (commonly referred to as UCD) ( ga, Coláiste na hOllscoile, Baile Átha Cliath) is a public research university in Dublin, Ireland, and a member institution of the National University of Ireland. With 33,284 students ...

obtained keys from the Pillar's custodian and locked themselves inside, with an assortment of equipment including flame thrower

A flamethrower is a ranged incendiary device designed to project a controllable jet of fire. First deployed by the Byzantine Empire in the 7th century AD, flamethrowers saw use in modern times during World War I, and more widely in Wor ...

s. From the gallery they hung a poster of Kevin Barry

Kevin Gerard Barry (20 January 1902 – 1 November 1920) was an Irish Republican Army (IRA) soldier who was executed by the British Government during the Irish War of Independence. He was sentenced to death for his part in an attack upon a Bri ...

, a Dublin Irish Republican Army

The Irish Republican Army (IRA) is a name used by various paramilitary organisations in Ireland throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. Organisations by this name have been dedicated to irredentism through Irish republicanism, the belief that ...

(IRA) volunteer executed by the British during the War of Independence. A crowd gathered below, and began to sing the Irish rebel song "Kevin Barry

Kevin Gerard Barry (20 January 1902 – 1 November 1920) was an Irish Republican Army (IRA) soldier who was executed by the British Government during the Irish War of Independence. He was sentenced to death for his part in an attack upon a Bri ...

". Eventually members of the Gardaí (Irish police) broke into the Pillar and ended the demonstration. No action was taken against the students, whose principal purpose, the Gardaí claimed, was publicity.

In 1956, members of the Fianna Fáil

Fianna Fáil (, ; meaning 'Soldiers of Destiny' or 'Warriors of Fál'), officially Fianna Fáil – The Republican Party ( ga, audio=ga-Fianna Fáil.ogg, Fianna Fáil – An Páirtí Poblachtánach), is a conservative and Christian ...

party, then in opposition, proposed that the statue be replaced by one of Robert Emmet

Robert Emmet (4 March 177820 September 1803) was an Irish Republican, orator and rebel leader. Following the suppression of the United Irish uprising in 1798, he sought to organise a renewed attempt to overthrow the British Crown and Protesta ...

, Protestant leader of an abortive rebellion in 1803. They thought that such a gesture might inspire Protestants in Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ga, Tuaisceart Éireann ; sco, label=Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots, Norlin Airlann) is a part of the United Kingdom, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, that is #Descriptions, variously described as ...

to fight for a reunited Ireland. In the North the possibility of dismantling and re-erecting the monument in Belfast

Belfast ( , ; from ga, Béal Feirste , meaning 'mouth of the sand-bank ford') is the capital and largest city of Northern Ireland, standing on the banks of the River Lagan on the east coast. It is the 12th-largest city in the United Kingdom ...

was raised in the Stormont parliament

The Parliament of Northern Ireland was the home rule legislature of Northern Ireland, created under the Government of Ireland Act 1920, which sat from 7 June 1921 to 30 March 1972, when it was suspended because of its inability to restore ord ...

, but the initiative failed to gain the support of the Northern Ireland government.

In 1959 a new Fianna Fáil government under Seán Lemass

Seán Francis Lemass (born John Francis Lemass; 15 July 1899 – 11 May 1971) was an Irish Fianna Fáil politician who served as Taoiseach and Leader of Fianna Fáil from 1959 to 1966. He also served as Tánaiste from 1957 to 1959, 1951 to 195 ...

deferred the question of the Pillar's removal on the grounds of cost; five years later Lemass agreed to "look at" the question of replacing Nelson's statue with one of Patrick Pearse

Patrick Henry Pearse (also known as Pádraig or Pádraic Pearse; ga, Pádraig Anraí Mac Piarais; 10 November 1879 – 3 May 1916) was an Irish teacher, barrister, poet, writer, nationalist, republican political activist and revolutionary who ...

, the leader of the Easter Rising, in time for the 50th anniversary of the Rising in 1966. An offer from the Irish-born American trade union leader Mike Quill

Michael Joseph "Red Mike" Quill (September 18, 1905 – January 28, 1966) was one of the founders of the Transport Workers Union of America (TWU), a union founded by subway workers in New York City that expanded to represent employees in ot ...

to finance the removal of the Pillar was not taken up, and as the anniversary approached, Nelson remained in place.

Destruction

On 8 March 1966, a powerful explosion destroyed the upper portion of the Pillar and brought Nelson's statue crashing to the ground amid hundreds of tons of rubble. O'Connell Street was almost deserted at the time, although a dance in the nearby Hotel Metropole's ballroom was about to end and brought crowds on to the street. There were no casualties—a taxi-driver parked close by had a narrow escape—and damage to property was relatively light given the strength of the blast. What was left of the Pillar was a jagged stump, high. In the first government response to the action, theJustice minister

A justice ministry, ministry of justice, or department of justice is a ministry or other government agency in charge of the administration of justice. The ministry or department is often headed by a minister of justice (minister for justice in a ...

, Brian Lenihan, condemned what he described as "an outrage which was planned and committed without any regard to the lives of the citizens". This response was considered "tepid" by ''The Irish Times'', whose editorial deemed the attack "a direct blow to the prestige of the state and the authority of the government". Kennedy suggests that government anger was mainly directed at what they considered a distraction from the official 50th anniversary celebrations of the Rising.

The absence of the pillar was regretted by some who felt the city had lost one of its most prominent landmarks. The Irish Literary Association was anxious that, whatever future steps were taken, the lettering on the pedestal should be preserved; the ''Irish Times

''The Irish Times'' is an Irish daily broadsheet newspaper and online digital publication. It launched on 29 March 1859. The editor is Ruadhán Mac Cormaic. It is published every day except Sundays. ''The Irish Times'' is considered a newspaper ...

'' reported that the Royal Irish Academy of Music was considering legal measures to prevent removal of the remaining stump. Reactions among the general public were relatively light-hearted, typified by the numerous songs inspired by the incident. These included the immensely popular " Up Went Nelson", set to the tune of "John Brown's Body

"John Brown's Body" (originally known as "John Brown's Song") is a United States marching song about the abolitionist John Brown. The song was popular in the Union during the American Civil War. The tune arose out of the folk hymn tradition of ...

" and performed by a group of Belfast schoolteachers, which remained at the top of the Irish charts for eight weeks. An American newspaper reported that the mood in the city was one of gaiety, with shouts of "Nelson has lost his last battle!" Some accounts relate that the Irish president, Éamon de Valera

Éamon de Valera (, ; first registered as George de Valero; changed some time before 1901 to Edward de Valera; 14 October 1882 – 29 August 1975) was a prominent Irish statesman and political leader. He served several terms as head of governm ...

, phoned ''The Irish Press

''The Irish Press'' ( Irish: ''Scéala Éireann'') was an Irish national daily newspaper published by Irish Press plc between 5 September 1931 and 25 May 1995.

Foundation

The paper's first issue was published on the eve of the 1931 All-Irelan ...

'' to suggest the headline: "British Admiral Leaves Dublin By Air"—according to the senator and presidential candidate David Norris, "the only recorded instance of humour in that lugubrious figure".

The Pillar's fate was sealed when Dublin Corporation issued a "dangerous building" notice. The trustees agreed that the stump should be removed. A last-minute request by the

The Pillar's fate was sealed when Dublin Corporation issued a "dangerous building" notice. The trustees agreed that the stump should be removed. A last-minute request by the Royal Institute of the Architects of Ireland

The Royal Institute of the Architects of Ireland ( ga, Institiúid Ríoga Ailtirí na hÉireann) founded in 1839, is the "competent authority for architects and professional body for Architecture in the Republic of Ireland."

The RIAI's purpos ...

for an injunction to delay the demolition on planning grounds was rejected by Justice Thomas Teevan. On 14 March, the Army destroyed the stump by a controlled explosion, watched at a safe distance by a crowd who, the press reported, "raised a resounding cheer". There was a scramble for souvenirs, and many parts of the stonework were taken from the scene. Some of these relics, including Nelson's head, eventually found their way into museums; parts of the lettered stonework from the pedestal are displayed in the grounds of the Butler House hotel in Kilkenny

Kilkenny (). is a city in County Kilkenny, Ireland. It is located in the South-East Region and in the province of Leinster. It is built on both banks of the River Nore. The 2016 census gave the total population of Kilkenny as 26,512.

Kilken ...

, while smaller remnants were used to decorate private gardens. Contemporary and subsequent accounts record that the army's explosion caused more damage than the first, but this, Fallon says, is a myth; damage claims arising from the second explosion amounted to less than a quarter of the sum claimed as a result of the original blast.

Aftermath

Investigations

It was initially assumed that the monument was destroyed by the IRA. ''The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'', and changed its name in 1959. Along with its sister papers ''The Observer'' and ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardian'' is part of the Gu ...

'' reported on 9 March that six men had been arrested and questioned, but their identities were not revealed and there were no charges. An IRA spokesman denied involvement, stating that they had no interest in demolishing mere symbols of foreign domination: "We are interested in the destruction of the domination itself". In the absence of any leads, rumours suggested that the Basque separatist movement ETA might be responsible, perhaps as part of a training exercise with an Irish republican splinter group; in the mid-1960s the explosives expertise of ETA was generally acknowledged.

No further information was forthcoming until 2000, when during a Raidió Teilifís Éireann interview a former IRA member, Liam Sutcliffe, claimed he had placed the bomb which detonated in the Pillar. In the 1950s Sutcliffe was associated with a group of dissident volunteers led by Joe Christle (1927–98), who had been expelled from the IRA in 1956 for "recklessness". In early 1966 Sutcliffe learned that Christle's group was planning "Operation Humpty Dumpty", an attack on the Pillar, and offered his services. According to Sutcliffe, on 28 February he placed a bomb within the Pillar, timed to go off in the early hours of the next morning. The explosive was a mixture of gelignite

Gelignite (), also known as blasting gelatin or simply "jelly", is an explosive material consisting of collodion-cotton (a type of nitrocellulose or guncotton) dissolved in either nitroglycerine or nitroglycol and mixed with wood pulp and saltpe ...

and ammonal

Ammonal is an explosive made up of ammonium nitrate and aluminium powder, not to be confused with T-ammonal which contains trinitrotoluene as well to increase properties such as brisance. The mixture is often referred to as Tannerite, which i ...

. It failed to detonate; Sutcliffe says that he returned early the next morning, recovered the device and redesigned its timer. On 7 March, shortly before the Pillar closed for the day, he climbed the inner stairway and placed the refurbished bomb near to the top of the shaft before going home. He learned of the success of his mission the next day, he says, having slept undisturbed through the night. Following his revelations, Sutcliffe was questioned by the Garda Síochána but not charged. He did not name others involved in the action, apart from Christle and his brother, Mick Christle.

Replacements

On 29 April 1969 the Irish parliament passed the Nelson Pillar Act, terminating the Pillar Trust and vesting ownership of the site in Dublin Corporation. The trustees received £21,170 in compensation for the Pillar's destruction, and a further sum for loss of income. In the debate, Senator Owen Sheehy-Skeffington argued that the Pillar had been capable of repair and should have been re-assembled and rebuilt. For more than twenty years the site stood empty, while various campaigns sought to fill the space. In 1970 the Arthur Griffith Society suggested a monument to

For more than twenty years the site stood empty, while various campaigns sought to fill the space. In 1970 the Arthur Griffith Society suggested a monument to Arthur Griffith

Arthur Joseph Griffith ( ga, Art Seosamh Ó Gríobhtha; 31 March 1871 – 12 August 1922) was an Irish writer, newspaper editor and politician who founded the political party Sinn Féin. He led the Irish delegation at the negotiations that prod ...

, founder of Sinn Féin

Sinn Féin ( , ; en, " eOurselves") is an Irish republican and democratic socialist political party active throughout both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland.

The original Sinn Féin organisation was founded in 1905 by Arthur ...

, and Pearse, whose centenary would fall in 1979, was the subject of several proposals. None of these schemes were accepted by the Corporation. A request in 1987 by the Dublin Metropolitan Streets Commission that the Pillar be rebuilt—with a different statue—was likewise rejected. In 1988, as part of the Dublin Millennium celebrations, businessman Michael Smurfit

Sir Michael Smurfit, KBE (born 7 August 1936), is an English-born Irish businessman. In the "2010 Irish Independent Rich List" he was listed at 25th with a €368 million personal fortune.

Early life

Smurfit, who was born in St Helens, ...

commissioned in memory of his father the Smurfit Millennium Fountain, erected close to the site of the pillar. The fountain included a bronze statue of Anna Livia, a personification of the River Liffey, sculpted by Éamonn O'Doherty. The monument, known colloquially as ''the Floozie in the Jacuzzi'', was not universally appreciated; O'Doherty's fellow-sculptor Edward Delaney

Edward Delaney (1930–2009) was an Irish sculptor born in Claremorris in County Mayo in 1930. His best known works include the 1967 statue of Wolfe Tone and famine memorial at the northeastern corner of St Stephen's Green in Dublin and the ...

called it an "atrocious eyesore".

1988 saw the launch of the Pillar Project, aimed at encouraging artists and architects to bring forward new ideas for an appropriate permanent memorial to replace Nelson. Suggestions included a flagpole, a triumphal arch modelled on the Paris Arc de Triomphe

The Arc de Triomphe de l'Étoile (, , ; ) is one of the most famous monuments in Paris, France, standing at the western end of the Champs-Élysées at the centre of Place Charles de Gaulle, formerly named Place de l'Étoile—the ''étoile'' ...

, and a "Tower of Light" with a platform that would restore Nelson's view over the city. In 1997 Dublin Corporation announced a formal design competition for a monument to mark the new millennium in 2000. The winning entry was Ian Ritchie's Spire of Dublin

The Spire of Dublin, alternatively titled the Monument of Light ( ga, An Túr Solais), is a large, stainless steel, pin-like monument in height, located on the site of the former Nelson's Pillar (and prior to that a statue of William Blakeney) ...

, a plain, needle-like structure rising from the street. The design was approved; on 22 January 2003 it was completed, despite some political and artistic opposition. During the excavations preceding the Spire's construction, the foundation stone of the Nelson Pillar was recovered. Press stories that a time capsule containing valuable coins had also been discovered fascinated the public for a while, but proved illusory.

Cultural references

The destruction of the Pillar brought a temporary glut of popular songs, including " Nelson's Farewell", byThe Dubliners

The Dubliners were an Irish folk band founded in Dublin in 1962 as The Ronnie Drew Ballad Group, named after its founding member; they subsequently renamed themselves The Dubliners. The line-up saw many changes in personnel over their fifty-y ...

, in which Nelson's airborne demise is presented as Ireland's contribution to the space race

The Space Race was a 20th-century competition between two Cold War rivals, the United States and the Soviet Union, to achieve superior spaceflight capability. It had its origins in the ballistic missile-based nuclear arms race between the t ...

. While in New York, Tommy Makem wrote "Lord Nelson" which he performed with the Clancy Brothers. Ironically, he set the words to the tune of "The Sash my Father Wore," a song of the militant Protestant Orange Order.

During its more than 150 years, the Pillar was an integral if controversial part of Dublin life, and was often reflected in Irish literature of the period. James Joyce

James Augustine Aloysius Joyce (2 February 1882 – 13 January 1941) was an Irish novelist, poet, and literary critic. He contributed to the modernist avant-garde movement and is regarded as one of the most influential and important writers of ...

's novel '' Ulysses'' (1922) is a meticulous depiction of the city on a single day, 16 June 1904. At the base of the Pillar trams from all parts of the city come and go; meanwhile the character Stephen Dedalus

Stephen Dedalus is James Joyce's literary alter ego, appearing as the protagonist and antihero of his first, semi-autobiographic novel of artistic existence ''A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man'' (1916) and an important character in Joyce' ...

fantasises a scene involving two elderly spinsters, who climb the steps to the viewing gallery where they eat plums and spit the stones down on those below, while gazing up at "the one-handled adulterer".

Joyce shared Yeats's view that Ireland's association with England was an essential element in a shared history, and asked: "Tell me why you think I ought to change the conditions that gave Ireland and me a shape and a destiny?" Oliver St. John Gogarty

Oliver Joseph St. John Gogarty (17 August 1878 – 22 September 1957) was an Irish poet, author, otolaryngologist, athlete, politician, and well-known conversationalist. He served as the inspiration for Buck Mulligan in James Joyce's novel ...

, in his literary memoir '' As I Was Going Down Sackville Street'', considers the Pillar "the grandest thing we have in Dublin", where "the statue in whiter stone gazed forever south towards Trafalgar and the Nile". That Pillar, says Gogarty, "marks the end of a civilization, the culmination of the great period of eighteenth century Dublin". Yeats's 1927 poem "The Three Monuments" has Parnell, Nelson and O'Connell on their respective monuments, mocking Ireland's post-independence leaders for their rigid morality and lack of courage, the obverse of the qualities of the "three old rascals".A later writer,

Brendan Behan

Brendan Francis Aidan Behan (christened Francis Behan) ( ; ga, Breandán Ó Beacháin; 9 February 1923 – 20 March 1964) was an Irish poet, short story writer, novelist, playwright, and Irish Republican activist who wrote in both English and ...

, in his ''Confessions of an Irish Rebel'' (1965) wrote from a Fenian

The word ''Fenian'' () served as an umbrella term for the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) and their affiliate in the United States, the Fenian Brotherhood, secret political organisations in the late 19th and early 20th centuries dedicated ...

perspective that Ireland owed Nelson nothing and that Dublin's poor regarded the Pillar as "a gibe at their own helplessness in their own country". In his poem "Dublin" (1939), written as the remaining vestiges of British overlordship were being removed from Ireland, Louis MacNeice

Frederick Louis MacNeice (12 September 1907 – 3 September 1963) was an Irish poet and playwright, and a member of the Auden Group, which also included W. H. Auden, Stephen Spender and Cecil Day-Lewis. MacNeice's body of work was widely a ...

envisages "Nelson on his pillar/ Watching his world collapse".Austin Clarke's 1957 poem "Nelson's Pillar, Dublin" scorns the various schemes to remove the monument and concludes "Let him watch the sky/ With those who rule. Stone eye/ And telescopes can prove/ Our blessings are above". In

Roddy Doyle

Roddy Doyle (born 8 May 1958) is an Irish novelist, dramatist and screenwriter. He is the author of eleven novels for adults, eight books for children, seven plays and screenplays, and dozens of short stories. Several of his books have been ma ...

's 1999 novel '' A Star Called Henry'' the title character shoots off Nelson's hand during the 1916 Easter Uprising.

John Boyne

John Boyne (born 30 April 1971) is an Irish novelist. He is the author of eleven novels for adults and six novels for younger readers. His novels are published in over 50 languages. His 2006 novel '' The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas'' was adapt ...

's 2017 novel "The Heart's Invisible Furies" includes a scene in the middle of the book that features the explosion at the pillar.

See also

* Monuments and memorials to Horatio Nelson, 1st Viscount Nelson * List of public art in DublinNotes and references

Notes

Citations

Sources

Books

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Newspapers and journals

* * * * * * * * * * * (This article first appeared in ''The New Statesman'', 6 May 1916)Online

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

Nelson Pillar

50th anniversary commemoration account, including numerous Pillar images taken before and after the bombing (Old Dublin Town)

personal eyewitness account of the students with the head of the Pillar's Nelson statue at Kilkenny Strand (Pól Ó Duibhir)

The night Nelson's Pillar fell and changed Dublin

includes photograph of the controlled demolition (''The Irish Times'')

Nelson Monument Blasted

10 March 1966 news reel report (British Pathé)

Nelson Pillar Remains Demolished

14 March 1966 news reel report (British Pathé) {{Authority control Columns related to the Napoleonic Wars Monumental columns in the Republic of Ireland Demolished buildings and structures in Dublin History of Dublin (city) Improvised explosive device bombings in the Republic of Ireland Buildings and structures completed in 1809 Buildings and structures demolished in 1966 Monuments and memorials to Horatio Nelson Neoclassical architecture in Ireland Outdoor sculptures in Ireland Destroyed sculptures Removed statues