Necking (engineering) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Necking, in

Armand Considère

published the basic criterion for necking in 1885, in the context of the stability of large scale structures such as bridges. Three concepts provide the framework for understanding neck formation. #Before deformation, all real materials have heterogeneities such as flaws or local variations in dimensions or composition that cause local fluctuations in stresses and strains. To determine the location of the incipient neck, these fluctuations need only be

The condition can also be expressed in terms of the nominal strain:

=

= = = (1 + εN)

Therefore, at the instability point:

σT = (1 + εN)

It can therefore also be formulated in terms of a plot of true stress against nominal strain. On such a plot, necking will start where a line from the point εN = -1 forms a tangent to the curve. This is shown in the next figure, which was obtained using the same Ludwik-Hollomon representation of the true stress – true strain relationship as that of the previous figure.

The condition can also be expressed in terms of the nominal strain:

=

= = = (1 + εN)

Therefore, at the instability point:

σT = (1 + εN)

It can therefore also be formulated in terms of a plot of true stress against nominal strain. On such a plot, necking will start where a line from the point εN = -1 forms a tangent to the curve. This is shown in the next figure, which was obtained using the same Ludwik-Hollomon representation of the true stress – true strain relationship as that of the previous figure.

Importantly, the condition also corresponds to a peak (plateau) in the nominal stress – nominal strain plot. This can be seen on obtaining the gradient of such a plot by differentiating the expression for σN with respect to εN.

σN =

∴ = -

Substituting for the true stress – nominal strain gradient (at the onset of necking):

= - = 0

This condition can also be seen in the two figures. Since many stress-strain curves are presented as nominal plots, and this is a simple condition that can be identified by visual inspection, it is in many ways the easiest criterion to use to establish the onset of necking. It also corresponds to the “strength” (

Importantly, the condition also corresponds to a peak (plateau) in the nominal stress – nominal strain plot. This can be seen on obtaining the gradient of such a plot by differentiating the expression for σN with respect to εN.

σN =

∴ = -

Substituting for the true stress – nominal strain gradient (at the onset of necking):

= - = 0

This condition can also be seen in the two figures. Since many stress-strain curves are presented as nominal plots, and this is a simple condition that can be identified by visual inspection, it is in many ways the easiest criterion to use to establish the onset of necking. It also corresponds to the “strength” (

engineering

Engineering is the use of scientific method, scientific principles to design and build machines, structures, and other items, including bridges, tunnels, roads, vehicles, and buildings. The discipline of engineering encompasses a broad rang ...

or materials science, is a mode of tensile deformation

Deformation can refer to:

* Deformation (engineering), changes in an object's shape or form due to the application of a force or forces.

** Deformation (physics), such changes considered and analyzed as displacements of continuum bodies.

* Defor ...

where relatively large amounts of strain

Strain may refer to:

Science and technology

* Strain (biology), variants of plants, viruses or bacteria; or an inbred animal used for experimental purposes

* Strain (chemistry), a chemical stress of a molecule

* Strain (injury), an injury to a mu ...

localize disproportionately in a small region of the material. The resulting prominent decrease in local cross-sectional area provides the basis for the name "neck". Because the local strains in the neck are large, necking is often closely associated with yielding, a form of plastic deformation associated with ductile

Ductility is a mechanical property commonly described as a material's amenability to drawing (e.g. into wire). In materials science, ductility is defined by the degree to which a material can sustain plastic deformation under tensile stres ...

materials, often metals or polymers. Once necking has begun, the neck becomes the exclusive location of yielding in the material, as the reduced area gives the neck the largest local stress

Stress may refer to:

Science and medicine

* Stress (biology), an organism's response to a stressor such as an environmental condition

* Stress (linguistics), relative emphasis or prominence given to a syllable in a word, or to a word in a phrase ...

.

Formation

Necking results from aninstability

In numerous fields of study, the component of instability within a system is generally characterized by some of the outputs or internal states growing without bounds. Not all systems that are not stable are unstable; systems can also be mar ...

during tensile deformation when the cross-sectional area of the sample decreases by a greater proportion than the material strain hardens.Armand Considère

published the basic criterion for necking in 1885, in the context of the stability of large scale structures such as bridges. Three concepts provide the framework for understanding neck formation. #Before deformation, all real materials have heterogeneities such as flaws or local variations in dimensions or composition that cause local fluctuations in stresses and strains. To determine the location of the incipient neck, these fluctuations need only be

infinitesimal

In mathematics, an infinitesimal number is a quantity that is closer to zero than any standard real number, but that is not zero. The word ''infinitesimal'' comes from a 17th-century Modern Latin coinage ''infinitesimus'', which originally referr ...

in magnitude.

#During plastic tensile deformation the material decreases in cross-sectional area due to the incompressibility of plastic flow. (Not due to the Poisson effect, which is linked to elastic behaviour.)

#During plastic tensile deformation the material strain hardens. The amount of hardening varies with extent of deformation.

The latter two effects determine the stability while the first effect determines the neck's location.

The Considère treatment

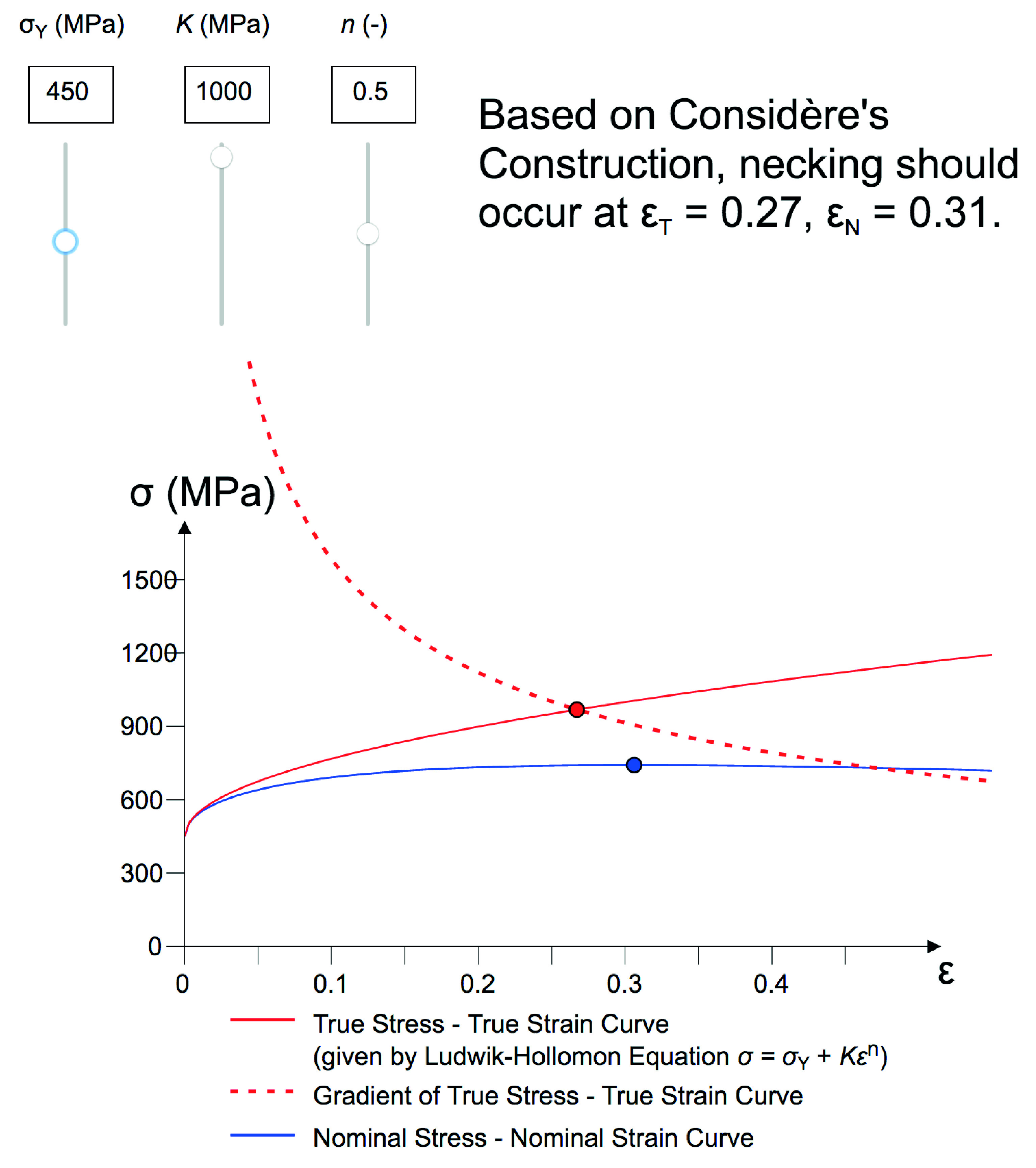

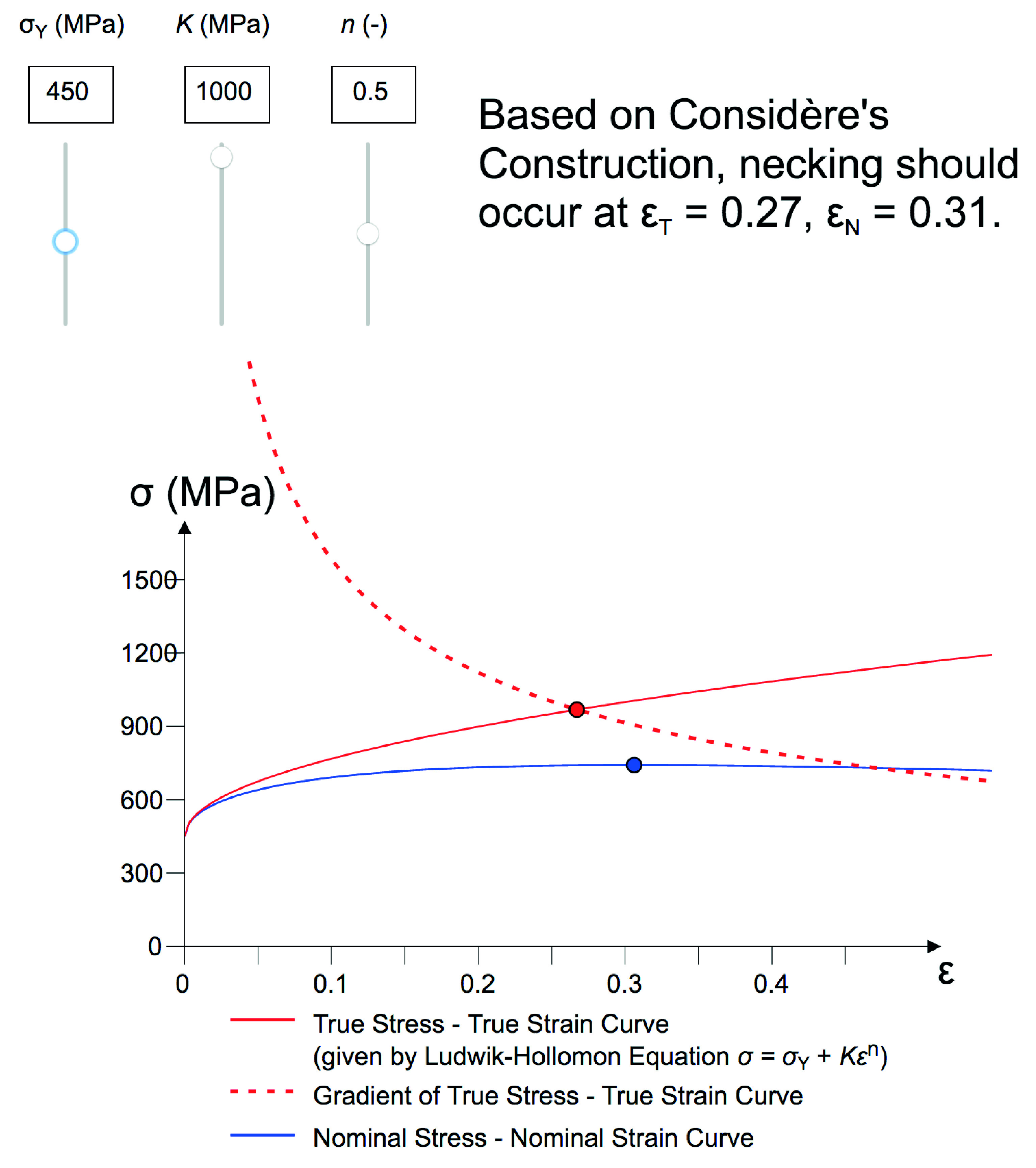

Instability (onset of necking) is expected to occur when an increase in the (local) strain produces no net increase in the load, ''F''. This will happen when △''F'' = 0 This leads to ''F'' = ''A'' σT ∴ d''F'' = ''A'' dσT + σT d''A'' = 0 ∴ = - = = dεT ∴ σT = with the T subscript being used to emphasize that these stresses and strains must be true values. Necking is thus predicted to start when the slope of the true stress / true strain curve falls to a value equal to the true stress at that point.Application to metals

Necking commonly arises in both metals and polymers. However, while the phenomenon is caused by the same basic effect in both materials, they tend to have different types of (true) stress-strain curve, such that they should be considered separately in terms of necking behaviour. For metals, the (true) stress tends to rise monotonically with increasing strain, although the gradient (work hardening

In materials science, work hardening, also known as strain hardening, is the strengthening of a metal or polymer by plastic deformation. Work hardening may be desirable, undesirable, or inconsequential, depending on the context.

This strengt ...

rate) tends to fall off progressively. This is primarily due to a progressive fall in dislocation

In materials science, a dislocation or Taylor's dislocation is a linear crystallographic defect or irregularity within a crystal structure that contains an abrupt change in the arrangement of atoms. The movement of dislocations allow atoms to sl ...

mobility, caused by interactions between them. With polymers, on the other hand, the curve can be more complex. For example, the gradient can in some cases rise sharply with increasing strain, due to the polymer chains

A polymer (; Greek '' poly-'', "many" + ''-mer'', "part")

is a substance or material consisting of very large molecules called macromolecules, composed of many repeating subunits. Due to their broad spectrum of properties, both synthetic an ...

becoming aligned as they reorganise during plastic deformation. This can lead to a stable neck. No effect of this type is possible in metals.

The figure shows a screenshot from an interactive simulation available on the DoITPoMS

Dissemination of IT for the Promotion of Materials Science (DoITPoMS) is a web-based educational software resource designed to facilitate the teaching and learning of Materials science, at the tertiary level for free.

History

The DoITPoMS proj ...

educational website. The construction is shown for a (true) stress-strain curve represented by a simple analytical expression (Ludwik-Hollomon).

The condition can also be expressed in terms of the nominal strain:

=

= = = (1 + εN)

Therefore, at the instability point:

σT = (1 + εN)

It can therefore also be formulated in terms of a plot of true stress against nominal strain. On such a plot, necking will start where a line from the point εN = -1 forms a tangent to the curve. This is shown in the next figure, which was obtained using the same Ludwik-Hollomon representation of the true stress – true strain relationship as that of the previous figure.

The condition can also be expressed in terms of the nominal strain:

=

= = = (1 + εN)

Therefore, at the instability point:

σT = (1 + εN)

It can therefore also be formulated in terms of a plot of true stress against nominal strain. On such a plot, necking will start where a line from the point εN = -1 forms a tangent to the curve. This is shown in the next figure, which was obtained using the same Ludwik-Hollomon representation of the true stress – true strain relationship as that of the previous figure.

Importantly, the condition also corresponds to a peak (plateau) in the nominal stress – nominal strain plot. This can be seen on obtaining the gradient of such a plot by differentiating the expression for σN with respect to εN.

σN =

∴ = -

Substituting for the true stress – nominal strain gradient (at the onset of necking):

= - = 0

This condition can also be seen in the two figures. Since many stress-strain curves are presented as nominal plots, and this is a simple condition that can be identified by visual inspection, it is in many ways the easiest criterion to use to establish the onset of necking. It also corresponds to the “strength” (

Importantly, the condition also corresponds to a peak (plateau) in the nominal stress – nominal strain plot. This can be seen on obtaining the gradient of such a plot by differentiating the expression for σN with respect to εN.

σN =

∴ = -

Substituting for the true stress – nominal strain gradient (at the onset of necking):

= - = 0

This condition can also be seen in the two figures. Since many stress-strain curves are presented as nominal plots, and this is a simple condition that can be identified by visual inspection, it is in many ways the easiest criterion to use to establish the onset of necking. It also corresponds to the “strength” (ultimate tensile stress

Ultimate tensile strength (UTS), often shortened to tensile strength (TS), ultimate strength, or F_\text within equations, is the maximum stress that a material can withstand while being stretched or pulled before breaking. In brittle materials t ...

), at least for metals that do neck (which covers the majority of “engineering” metals). On the other hand, the peak in a nominal stress-strain curve is commonly a fairly flat plateau, rather than a sharp maximum, so accurate assessment of the strain at the onset of necking may be difficult. Nevertheless, this strain is a meaningful indication of the “ductility” of the metal – more so than the commonly-used “nominal strain at fracture”, which depends on the aspect ratio of the gauge length of the tensile test-piece – see the article on ductility

Ductility is a mechanical property commonly described as a material's amenability to drawing (e.g. into wire). In materials science, ductility is defined by the degree to which a material can sustain plastic deformation under tensile stres ...

.

Application to polymers

The tangent construction shown above is rarely used in interpreting the stress-strain curves of metals. However, it is popular for analysis of the tensile drawing of polymers. (since it allows study of the regime of stable necking). It may be noted that, for polymers, the strain is commonly expressed as a “draw ratio”, rather than a strain: in this case, extrapolation of the tangent is carried out to a draw ratio of zero, rather than a strain of -1. The plots relate (top) to a material that forms a stable neck and (bottom) a material that deforms homogeneously at all draw ratios. As deformation proceeds, the geometric instability causes strain to continue concentrating in the neck until the material either ruptures or the necked material hardens enough, as indicated by the second tangent point in the top diagram, to cause other regions of the material to deform instead. The amount of strain in the stable neck is called the ''natural draw ratio'' because it is determined by the material's hardening characteristics, not the amount of drawing imposed on the material. Ductile polymers often exhibit stable necks because molecular orientation provides a mechanism for hardening that predominates at large strains.See also

*Stress–strain curve

In engineering and materials science, a stress–strain curve for a material gives the relationship between stress and strain. It is obtained by gradually applying load to a test coupon and measuring the deformation, from which the stress and ...

*Trace necking

In printed circuit boards, teardrops are typically drop-shaped features at the junction of vias (''teardrop vias'') or contact pads (''teardrop pads'') and traces (''teardrop traces'').

The main purpose of teardrops is to enhance structural ...

*Universal testing machine

A universal testing machine (UTM), also known as a universal tester, materials testing machine or materials test frame, is used to test the tensile strength and compressive strength of materials. An earlier name for a tensile testing machine is ...

References

{{Reflist Materials science