Nativism (politics) in the United States on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Nativism in United States politics is opposition to an internal minority on the basis of its supposed “un-American” foundation. Historian

Nativism in United States politics is opposition to an internal minority on the basis of its supposed “un-American” foundation. Historian

"The Bennett Law Campaign in Wisconsin,"

''Wisconsin Magazine Of History'', 10: 4 (1926–1927), p. 388 Hoard, a Republican, was defeated by the Democrats. A similar campaign in Illinois regarding the "Edwards Law" led to a Republican defeat there in 1890.

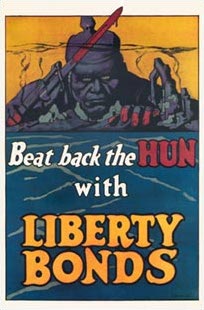

In 1917–1918, after the U.S. declared war on Germany, a wave of nativist sentiment led to the suppression of German cultural activities in the United States. There was little violence, buta few places and many streets had their names changed. Churches switched to English for their services, and German Americans were forced to buy war bonds to show their patriotism.

Former president

In 1917–1918, after the U.S. declared war on Germany, a wave of nativist sentiment led to the suppression of German cultural activities in the United States. There was little violence, buta few places and many streets had their names changed. Churches switched to English for their services, and German Americans were forced to buy war bonds to show their patriotism.

Former president

Many Irish work gangs were hired by contractors to build canals, railroads, city streets and sewers across the country. In the South, they underbid slave labor. One result was that small cities that served as railroad centers came to have large Irish populations.

Many Irish work gangs were hired by contractors to build canals, railroads, city streets and sewers across the country. In the South, they underbid slave labor. One result was that small cities that served as railroad centers came to have large Irish populations.

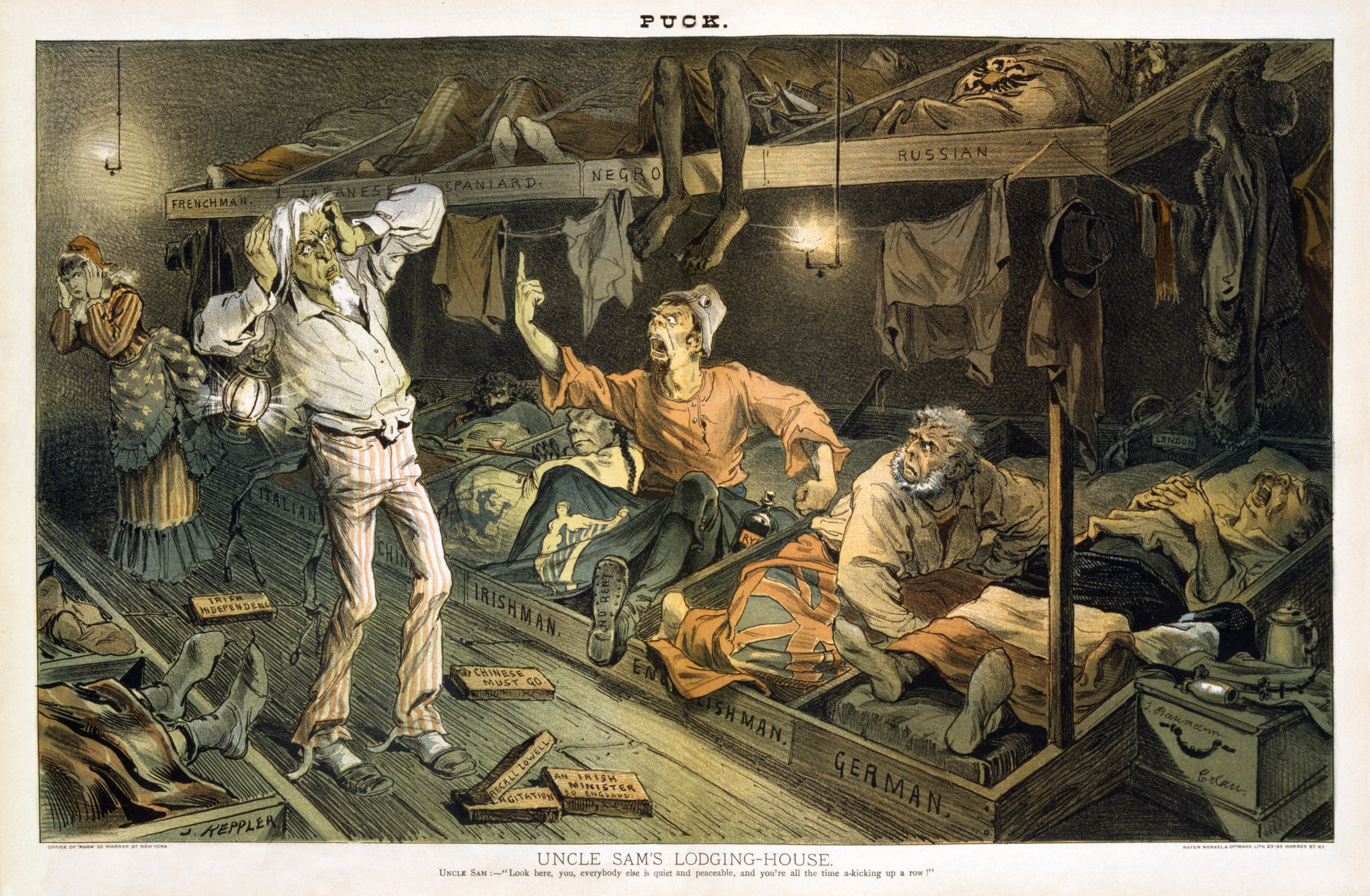

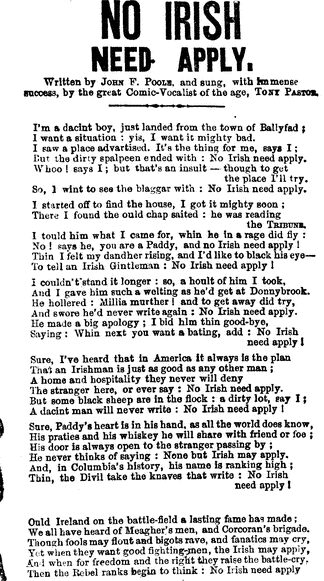

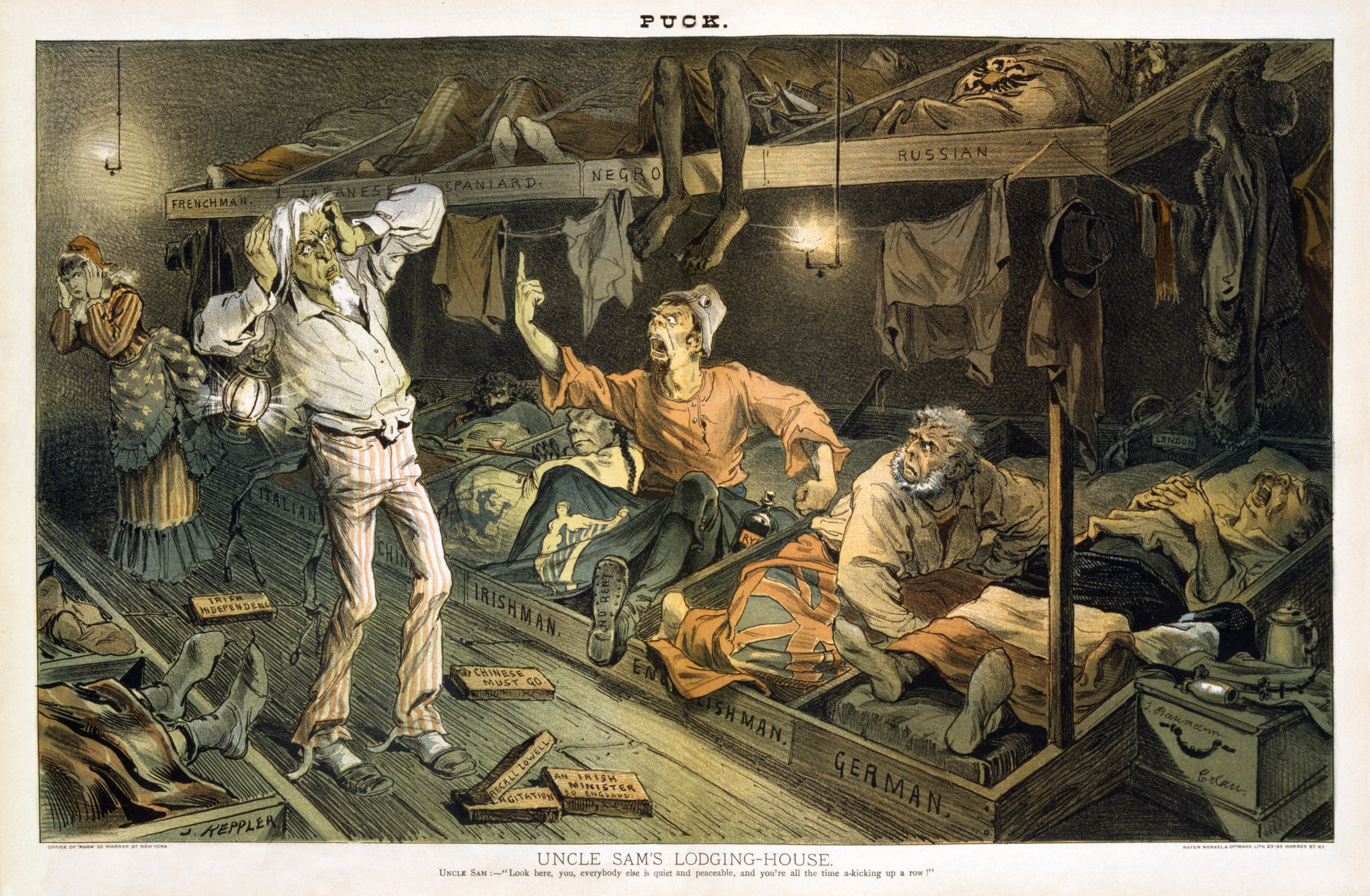

The Irish had many humorists of their own, but were scathingly attacked in political cartoons, especially those in ''Puck'' magazine from the 1870s to 1900; it was edited by secular Germans who opposed the Catholic Irish in politics. In addition, the cartoons of

The Irish had many humorists of their own, but were scathingly attacked in political cartoons, especially those in ''Puck'' magazine from the 1870s to 1900; it was edited by secular Germans who opposed the Catholic Irish in politics. In addition, the cartoons of

One of presidential candidate Donald Trump's central campaign promises in 2016 was to build a 1,000-mile border wall to Mexico and have Mexico pay for it. By the end of his term, the U.S. had built 73 miles of primary and secondary wall in new locations, and 365 miles of fencing replacing outdated barriers. In February 2019, Congress passed and Trump signed a funding bill that included $1.375 billion for 55 miles of bollard border fencing. Trump also declared a

One of presidential candidate Donald Trump's central campaign promises in 2016 was to build a 1,000-mile border wall to Mexico and have Mexico pay for it. By the end of his term, the U.S. had built 73 miles of primary and secondary wall in new locations, and 365 miles of fencing replacing outdated barriers. In February 2019, Congress passed and Trump signed a funding bill that included $1.375 billion for 55 miles of bollard border fencing. Trump also declared a

excerpt

* Anbinder, Tyler. "Nativism and prejudice against immigrants," in ''A companion to American immigration,'' ed. by Reed Ueda (2006) pp. 177–20

excerpt

* Bennett, David H. ''The Party of Fear: From Nativist Movements to the New Right in American History'' (2nd ed. 1995). * Billington, Ray Allen. ''The Protestant Crusade, 1800–1860: A Study of the Origins of American Nativism'' (1938

online

* Boissoneault, Lorraine. "How the 19th-Century Know Nothing Party Reshaped American Politics." ''Smithsonian Magazine'' (2017), heavily illustrated with nativist editorial cartoons

online

* Daniels, Roger. ''Guarding the golden door: American immigration policy and immigrants since 1882'' (Macmillan, 2005). * Davis, David Brion, ed. ''The Fear of Conspiracy: Images of Un-American Subversion from the Revolution to the Present'' (2008) covers rhetoric of nativist countersubversion and the paranoid style

excerpt

* DeConde, Alexander. ''Ethnicity, Race, and American Foreign Policy: A History'' (1992)

online

* Edwards III, George C. "The Bully in the Pulpit." ''Presidential Studies Quarterly'' 50.2 (2020): 286-324; on President Trump's rhetoric

online

* Franchot, Jenny. ''Roads to Rome: The Antebellum Protestant Encounter with Catholicism '' (1994

online

* Haebler, Peter. "Nativist Riots in Manchester: An Episode of Know-Nothingism in New Hampshire." ''Historical New Hampshire'' 39 (1985): 121-37. * Higham, John, ''Strangers in the Land: Patterns of American Nativism, 1860–1925'' (1955), a standard scholarly history

online

* Hopkins, Daniel J., and Samantha Washington. "The rise of Trump, the fall of prejudice? Tracking white Americans’ racial attitudes via a panel survey, 2008–2018." ''Public Opinion Quarterly'' 84.1 (2020): 119-140. * Hueston, Robert Francis. ''The Catholic Press and Nativism, 1840–1860'' (1976) * Jensen, Richard. "Comparative Nativism: The United States, Canada and Australia, 1880s–1910s," ''Canadian Journal for Social Research'' (2010) vol 3#1 pp. 45–55 * Knight, Peter, ed. ''Conspiracy theories in American history: an encyclopedia'' (2 vol. ABC-CLIO, 2003); 300 entries by 123 experts in 925 pp.. * Knobel, Dale T. '' "America for the Americans": The Nativist Movement in the United States'' (Twayne, 1996) covers 1800 to 1930. * Kraut, Alan M. ''Silent Travelers: Germs, Genes, and the "Immigrant Menace."'' (1994). * Lee, Erika. "America first, immigrants last: American xenophobia then and now." ''Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era'' 19.1 (2020): 3–18

online

* Lee, Erika. ''America for Americans: A History of Xenophobia in the United States'' (2019)

excerpt

* Leonard, Ira M. and Robert D. Parmet. ''American Nativism 1830–1860'' (1971) * Obinna, Denise N. "Lessons in Democracy: America's Tenuous History with Immigrants." ''Journal of Historical Sociology'' 31.3 (2018): 238-252

online

* Okrent, Daniel. ''Guarded Gate: Bigotry, Eugenics, and the Law that Kept Two Generations of Jews, Italians, and Other European Immigrants Out of America'' (2019

excerpt

* Oxx, Katie. ''The Nativist Movement in America: Religious Conflict in the 19th Century'' (2013

excerpt

includes some primary sources * Perea, Juan F. ed. ''Immigrants Out!: The New Nativism and the Anti-Immigrant Impulse in the United States'' (New York UP, 1997)

online

* Ritter, Luke. ''Inventing America's First Immigration Crisis: Political Nativism in the Antebellum West'' (Fordham UP, (2021

online

focus on Chicago, Cincinnati, Louisville, and St. Louis * Schrag Peter. ''Not Fit For Our Society: Immigration and Nativism in America'' (U of California Press; 2010) 256 pp

online

* Thernstrom, Stephan, et al. eds. ''Harvard encyclopedia of American ethnic groups'' (Harvard UP, 1980); massive authoritative coverage of all major ethnic groups and smaller ones too

online

* Wright, Matthew, and Morris Levy. "American public opinion on immigration: Nativist, polarized, or ambivalent?" ''International Migration'' 58.6 (2020): 77-95. * Yakushko, Oksana. ''Modern-Day Xenophobia: Critical Historical and Theoretical Perspectives on the Roots of Anti-Immigrant Prejudice'' (Palgrave Macmillan, 2018

excerpt

* Young, Clifford, Katie Ziemer, and Chris Jackson. "Explaining Trump's popular support: Validation of a nativism index." ''Social Science Quarterly'' 100.2 (2019): 412-418

online

excerpt

covers Britain, Belgium, Italy, Russia, Greece, USA, Africa, New Zealand * Stephen, Alexander. ''Americanization and anti-Americanism : the German encounter with American culture after 1945'' (2007

online

* Thompson, Maris R. ''Narratives of Immigration and Language Loss: Lessons from the German American Midwest'' (Lexington Books, 2017). * Tischauser, Leslie V. ''The Burden of Ethnicity: The German Question in Chicago, 1914–1941''. (1990).

online

* De León, Arnoldo. ''They Called Them Greasers: Anglo Attitudes toward Mexicans in Texas, 1821–1900'' (U of Texas Press, 1983) * González, Juan. ''Harvest of Empire: A History of Latinos in America'' (2000, 2011, 2022

excerpt

* Gonzales, Phillip B. "La Junta De Indignacion: Hispano Repertoire of Collective Protest in New Mexico, 1884-1933" ''Western Historical Quarterly''. 31#2 (2000, pp 161-186. https://doi.org/10.2307/970061 * Gonzales, Phillip B., Renato Rosaldo, and Mary Louise Pratt, eds. ''Trumpism, Mexican America, and the Struggle for Latinx Citizenship'' (U of New Mexico Press, 2021). * Guglielmo, Thomas A. “Fighting for Caucasian Rights: Mexicans, Mexican Americans, and the Transnational Struggle for Civil Rights in World War II Texas.” ''Journal of American History'' 92#4, 2006, pp. 1212–37

online

* Hartman, Todd K., Benjamin J. Newman, and C. Scott Bell. "Decoding prejudice toward Hispanics: Group cues and public reactions to threatening immigrant behavior." ''Political Behavior'' 36.1 (2014): 143-163

online

also se

abridged version

* Hoffman, Abraham. "Stimulus to repatriation: The 1931 federal deportation drive and the Los Angeles Mexican community." ''Pacific Historical Review'' 42.2 (1973): 205-219

online

* Kang, Yowei, and Kenneth C.C. Yang. "Communicating Racism and Xenophobia in the Era of Donald Trump: A Computational Framing Analysis of the US-Mexico Cross-Border Wall Discourses." ''Howard Journal of Communications'' 33.2 (2022): 140-159. * López, Ian F. Haney. ''Racism on trial: The Chicano fight for justice'' ( Harvard University Press, 2004). * Verea, Mónica. "Anti-immigrant and Anti-Mexican attitudes and policies during the first 18 months of the Trump Administration." ''Norteamérica'' 13.2 (2018): 197-226

online

online

* Gerber, David A., ed. ''Anti-Semitism in American History'' (U of Illinois Press, 1986), scholarly essays. * Jaher, Frederic Cople. ''A Scapegoat in the Wilderness: The Origins and Rise of Anti-Semitism in America'' (Harvard UP, 1994), a standard scholarly history. * Rockaway, Robert. "Henry Ford and the Jews: The Mass Production of Hate." ''American Jewish History'' 89.4 (2001): 467-469

summary

* Stember, Charles, ed. ''Jews in the Mind of America'' (1966)

online

* Tevis, Britt P. "Trends in the Study of Antisemitism in United States History." ''American Jewish History'' 105.1 (2021): 255-284

online

Anti-immigration politics Asian-American issues Asian-American-related controversies Far-right politics Japanese-American history Anti-Japanese sentiment in the United States Racially motivated violence against Asian-Americans White supremacy in the United States Xenophobia

Nativism in United States politics is opposition to an internal minority on the basis of its supposed “un-American” foundation. Historian

Nativism in United States politics is opposition to an internal minority on the basis of its supposed “un-American” foundation. Historian Tyler Anbinder

Tyler Anbinder (born September 26, 1962) is an American historian known for his influential work on the pre-civil war period in U.S. history.

Books

* ''Nativism and Slavery: The Northern Know Nothings and the Politics of the 1850s''. New York: O ...

defines a nativist as:someone who fears and resents immigrants and their impact on the United States, and wants to take some action against them, be it through violence, immigration restriction, or placing limits on the rights of newcomers already in the United States. “Nativism” describes the movement to bring the goals of nativists to fruition.According to the historian John Higham, nativism is:

an intense opposition to an internal minority on the grounds of its foreign (i.e., “un-American”) connections. Specific nativist antagonisms may and do, vary widely in response to the changing character of minority irritants and the shifting conditions of the day; but through each separate hostility runs the connecting, energizing force of modernnationalism Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a in-group and out-group, group of peo .... While drawing on much broader cultural antipathies and ethnocentric judgments, nativism translates them into zeal to destroy the enemies of a distinctively American way of life.

Early republic

Nativism was a political factor in the United States in the 1790s as well as in the 1830s–1850s. There was little nativism in the colonial era, but for a while,Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin ( April 17, 1790) was an American polymath who was active as a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher, and political philosopher. Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the leading int ...

was hostile to German Americans

German Americans (german: Deutschamerikaner, ) are Americans who have full or partial German ancestry. With an estimated size of approximately 43 million in 2019, German Americans are the largest of the self-reported ancestry groups by the Unite ...

in colonial Pennsylvania

The Province of Pennsylvania, also known as the Pennsylvania Colony, was a British North American colony founded by William Penn after receiving a land grant from Charles II of England in 1681. The name Pennsylvania ("Penn's Woods") refers to Wi ...

; he called them "Palatine Boors". However, he reversed his opinion of German Americans and became a supporter of them.

Nativism became a major issue in the late 1790s, when the Federalist Party

The Federalist Party was a conservative political party which was the first political party in the United States. As such, under Alexander Hamilton, it dominated the national government from 1789 to 1801.

Defeated by the Jeffersonian Repu ...

expressed its strong opposition to the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are conside ...

. Federalists were especially troubled by Republican leader Albert Gallatin

Abraham Alfonse Albert Gallatin (January 29, 1761 – August 12, 1849) was a Genevan–American politician, diplomat, ethnologist and linguist. Often described as "America's Swiss Founding Father", he was a leading figure in the early years o ...

, an immigrant from Geneva Switzerland. Fearing that he represented foreign interests, the Federalists had him expelled from the Senate on a technicality in 1794. They then began to build their nativist appeals. They sought to strictly limit immigration, and to stretch the time to 14 years for citizenship. During the 1798 Quasi-War

The Quasi-War (french: Quasi-guerre) was an undeclared naval war fought from 1798 to 1800 between the United States and the French First Republic, primarily in the Caribbean and off the East Coast of the United States. The ability of Congress ...

with France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, the Federalists passed the Alien and Sedition Acts

The Alien and Sedition Acts were a set of four laws enacted in 1798 that applied restrictions to immigration and speech in the United States. The Naturalization Act increased the requirements to seek citizenship, the Alien Friends Act allowed th ...

. They included the Alien Act, the Naturalization Act and the Sedition Act. The movement was led by Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton (January 11, 1755 or 1757July 12, 1804) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first United States secretary of the treasury from 1789 to 1795.

Born out of wedlock in Charle ...

, despite his own status as an immigrant. Phillip Magness argues that "Hamilton's political career might legitimately be characterized as a sustained drift into nationalistic xenophobia." Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

and James Madison

James Madison Jr. (March 16, 1751June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Father. He served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison is hailed as the "Father of the Constitution" for h ...

led the opposition by drafting the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions. The two laws against aliens were motivated by fears of a growing Irish radical presence in Philadelphia, where they supported Jefferson. However, they were not actually enforced. President John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, attorney, diplomat, writer, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Befor ...

annoyed his fellow Federalists by making peace with the Republic of France, and he also annoyed them by splitting his party in 1800. Jefferson was elected president, and he reversed most of the hostile legislation.

1830–1860

The rate of immigration into the new nation was slow until 1840, when it suddenly expanded, with the arrival of a total of over 4 million Irish, English, and German (and other) immigrants, men, women and children, from 1840-1860. Nativist movements immediately emerged. The term "nativism" appeared by 1844: "Thousands were Naturalized expressly to oppose Nativism, and voted the Polk ticket mainly to that end." Nativism gained its name from the "Native American" parties of the 1840s and 1850s. In this context "Native" does not mean Indigenous Americans or American Indians but rather those European descendants of the settlers of the originalThirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies, also known as the Thirteen British Colonies, the Thirteen American Colonies, or later as the United Colonies, were a group of British colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America. Founded in the 17th and 18th centu ...

. Nativists objected primarily to Irish Roman Catholics because of their loyalty to the Pope

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

and also because of their supposed rejection of republicanism

Republicanism is a political ideology centered on citizenship in a state organized as a republic. Historically, it emphasises the idea of self-rule and ranges from the rule of a representative minority or oligarchy to popular sovereignty. ...

as an American ideal.

Nativist movements included the Know Nothing or "American Party" of the 1850s, the Immigration Restriction League

The Immigration Restriction League was an American nativist and anti-immigration organization founded by Charles Warren, Robert DeCourcy Ward, and Prescott F. Hall in 1894. According to Erika Lee, in 1894 the old stock Yankee upper-class found ...

of the 1890s, and the anti-Asian movements in the Western states, resulting in the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882

The Chinese Exclusion Act was a United States federal law signed by President Chester A. Arthur on May 6, 1882, prohibiting all immigration of Chinese laborers for 10 years. The law excluded merchants, teachers, students, travelers, and diplo ...

and the signing of the "Gentlemen's Agreement of 1907

The was an informal agreement between the United States of America and the Empire of Japan whereby Japan would not allow further emigration to the United States and the United States would not impose restrictions on Japanese immigrants alrea ...

", by which the government of Imperial Japan

The also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was a historical nation-state and great power that existed from the Meiji Restoration in 1868 until the enactment of the post-World War II 1947 constitution and subsequent forma ...

prevented Japanese nationals from emigrating

Emigration is the act of leaving a resident country or place of residence with the intent to settle elsewhere (to permanently leave a country). Conversely, immigration describes the movement of people into one country from another (to permanent ...

to the United States. Labor unions

A trade union (labor union in American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers intent on "maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment", ch. I such as attaining better wages and benefits (su ...

were strong supporters of Chinese exclusion and limits on immigration, because they feared that immigrants would lower wages and make it harder for workers to organize themselves into unions.

Know Nothing Party mid-1850s

The Know Nothing party had a marching song they chanted in 1855: :The Natives are up, d'ye see... :They have seen a foreign band, :By a servile priesthood led, :Polluting this Eden-land, :And the graves of the patriot dead. :The boy and the bearded man, :Have left the sweets of home, :To resist a ruthless clan-- :The knaves of the Church of Rome. :The Natives! The Natives!! The Natives!! Nativist outbursts occurred in theNortheast

The points of the compass are a set of horizontal, radially arrayed compass directions (or azimuths) used in navigation and cartography. A compass rose is primarily composed of four cardinal directions—north, east, south, and west—each sep ...

from the 1830s to the 1850s, primarily in response to a surge of Irish Catholic immigration. The leadership was mostly obscure local men, although 1836 the famous painter and telegraph inventor Samuel Morse

Samuel Finley Breese Morse (April 27, 1791 – April 2, 1872) was an American inventor and painter. After having established his reputation as a portrait painter, in his middle age Morse contributed to the invention of a single-wire telegraph ...

was a leader. In 1844 the Order of United Americans was founded as a nativist fraternity, following the Philadelphia Nativist Riots

The Philadelphia nativist riots (also known as the Philadelphia Prayer Riots, the Bible Riots and the Native American Riots) were a series of riots that took place on May 68 and July 67, 1844, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States and the ...

Billington, ''The Protestant Crusade, 1800–1860'' p 336.

The nativists went public in 1854 when they formed the "American Party", which was especially hostile to the immigration of Irish Catholics, and campaigned for laws to require longer wait time between immigration and naturalization; these laws never passed. Henry Winter Davis, the Know-Nothing Congressman from Maryland, blamed the un-American Catholic immigrants for the election of James Buchanan

James Buchanan Jr. ( ; April 23, 1791June 1, 1868) was an American lawyer, diplomat and politician who served as the 15th president of the United States from 1857 to 1861. He previously served as secretary of state from 1845 to 1849 and repr ...

in 1856, stating:The recent election has developed in an aggravated form every evil against which the American party protested. Foreign allies have decided the government of the country -- men naturalized in thousands on the eve of the election. Again in the fierce struggle for supremacy, men have forgotten the ban which the Republic puts on the intrusion of religious influence on the political arena. These influences have brought vast multitudes of foreign-born citizens to the polls, ignorant of American interests, without American feelings, influenced by foreign sympathies, to vote on American affairs; and those votes have, in point of fact, accomplished the present result.It was at this time that the term "nativist" first appeared, as their opponents denounced them as "bigoted nativists". Former President

Millard Fillmore

Millard Fillmore (January 7, 1800March 8, 1874) was the 13th president of the United States, serving from 1850 to 1853; he was the last to be a member of the Whig Party while in the White House. A former member of the U.S. House of Represen ...

ran on the American Party ticket for the Presidency in 1856, although he gave only weak support to nativism. The American Party also included many former Whigs who ignored nativism, and included (in the South) a few Roman Catholics whose families had long lived in America. Conversely, much of the opposition to Roman Catholics came from Protestant Irish immigrants and German Lutheran immigrants, who were not native at all and can hardly be called "nativists."

This form of American nationalism

American nationalism, is a form of civic, ethnic, cultural or economic influences

*

*

*

*

*

*

* found in the United States. Essentially, it indicates the aspects that characterize and distinguish the United States as an autonomous political ...

is often identified with xenophobia

Xenophobia () is the fear or dislike of anything which is perceived as being foreign or strange. It is an expression of perceived conflict between an in-group and out-group and may manifest in suspicion by the one of the other's activities, a ...

and anti-Catholic sentiment

Anti-Catholicism is hostility towards Catholics or opposition to the Catholic Church, its clergy, and/or its adherents. At various points after the Reformation, some majority Protestant states, including England, Prussia, Scotland, and the Un ...

. In Charlestown, Massachusetts

Charlestown is the oldest neighborhood in Boston, Massachusetts, in the United States. Originally called Mishawum by the Massachusett tribe, it is located on a peninsula north of the Charles River, across from downtown Boston, and also adjoins ...

, a nativist mob attacked and burned down a Catholic convent in 1834 (no one was injured). In the 1840s, small scale riots between Roman Catholics and nativists took place in several cities. In Philadelphia in 1844, a series of nativist assaults on Catholic churches and community centers resulted in the loss of lives on both sides. Local volunteer fire brigades were often responsible. Alarmed community leaders found a partial solution in professionalization of the police forces. In Louisville, Kentucky

Louisville ( , , ) is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Kentucky and the 28th most-populous city in the United States. Louisville is the historical seat and, since 2003, the nominal seat of Jefferson County, on the Indiana border ...

, election-day rioters killed at least 22 people in attacks on German and Irish Catholics on "Bloody Monday

Bloody Monday was a series of riots on August 6, 1855, in Louisville, Kentucky, an election day, when Protestant mobs attacked Irish and German Catholic neighborhoods. These riots grew out of the bitter rivalry between the Democrats and the Nat ...

," 6 August 1855.

The new Republican Party kept its nativist element suppressed during the 1860s, since immigrants were urgently needed for the Union Army. Nativism experienced a short revival in the 1890s, led by Protestant Irish immigrants hostile to the immigration of European Catholics, especially the American Protective Association. Political parties had a strong ethno-cultural base. Protestant immigrants from England, Ireland, Scotland, and Scandinavia favored the Republicans during the Third Party System

In the terminology of historians and political scientists, the Third Party System was a period in the history of political parties in the United States from the 1850s until the 1890s, which featured profound developments in issues of American n ...

(1854–1896), while Irish Catholics, Germans and others were usually Democratic.

Asian targets

Anti-Chinese

In the 1870s and 1880s in the Western states, ethnic White immigrants, especiallyIrish Americans

, image = Irish ancestry in the USA 2018; Where Irish eyes are Smiling.png

, image_caption = Irish Americans, % of population by state

, caption = Notable Irish Americans

, population =

36,115,472 (10.9%) alone ...

targeted violence against Chinese workers, driving them out of smaller towns. Denis Kearney

Denis Kearney (1847–1907) was a California labor leader from Ireland who was active in the late 19th century and was known for his anti-Chinese activism. Called "a demagogue of extraordinary power," he frequently gave long and caustic speeches ...

, an immigrant from Ireland, led a mass movement in San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish for " Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the fourth most populous in California and 17t ...

in the 1870s that incited racist attacks on the Chinese there and threatened public officials and railroad owners. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882

The Chinese Exclusion Act was a United States federal law signed by President Chester A. Arthur on May 6, 1882, prohibiting all immigration of Chinese laborers for 10 years. The law excluded merchants, teachers, students, travelers, and diplo ...

was the first of many nativist acts of Congress which attempted to limit the flow of immigrants into the U.S.. The Chinese responded to it by filing false claims of American birth, enabling thousands of them to immigrate to California. The exclusion of the Chinese caused the western railroads to begin importing Mexican railroad workers in greater numbers ("traquero A traquero is a railroad track worker, or "section hand", especially a Mexican or Mexican American railroad track worker (" gandy dancer" in American English usage). The word derives from "traque", Spanglish for "track". Background

While the U.S. ra ...

s").

Anti-Japanese

Attacks on the Japanese in the Western U.S., echoing the dreadedYellow Peril

The Yellow Peril (also the Yellow Terror and the Yellow Specter) is a racial color metaphor that depicts the peoples of East and Southeast Asia as an existential danger to the Western world. As a psychocultural menace from the Eastern world ...

became increasingly xenophobic after the unexpected Japanese triumph over the supposedly powerful Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War ...

in the Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War ( ja, 日露戦争, Nichiro sensō, Japanese-Russian War; russian: Ру́сско-япóнская войнá, Rússko-yapónskaya voyná) was fought between the Empire of Japan and the Russian Empire during 1904 and 1 ...

of 1904–1905. In October 1906, the San Francisco Board of Education passed a regulation whereby children of Japanese descent would be required to attend racially segregated and separate schools. At the time, Japanese immigrants made up 1% of the state's population; many of them had come under the treaty in 1894 which had assured free immigration from Japan. In 1907, nativists rioted up and down the West Coast demanding exclusion of Japanese immigrants and imposition of segregated schools for Caucasian and Japanese students.

The California Alien Land Law of 1913

The California Alien Land Law of 1913 (also known as the Webb–Haney Act) prohibited "aliens ineligible for citizenship" from owning agricultural land or possessing long-term leases over it, but permitted leases lasting up to three years. It affe ...

was specifically created to prevent land ownership among Japanese citizens who were residing in the state of California. In 1918 courts ruled that American-born children had the right to own land. California proceeded to strengthen its Alien land law in 1920 and 1923 and other states followed.Ferguson, Edwin E. 1947. "The California Alien Land Law and the Fourteenth Amendment." ''California Law Review'' 35 (1): 61.

According to Gary Y. Okihiro, the Japanese government subsidized Japanese writers in America especially Kiyoshi Kawakami was a Japanese Christian journalist who published several books in the United States and the United Kingdom. He was born in Yonezawa, educated in the law in Japan, and was for a short time engaged in newspaper work in that country.

He sometimes ...

and Yamato Ichihashi

Yamato Ichihashi (April 15, 1878 – April 5, 1963) was one of the first academics from East Asia in the United States. Ichihashi wrote a comprehensive account of his experiences as an internee at the Tule Lake War Relocation Center, where he was ...

to refute the hostile stereotypes and establish a favorable image of Japanese in the American mind. Thus Kawakami's books especially ''Asia at the Door'' (1914) and ''The Real Japanese Question'' (1921) tried to refute the false slanders generated by deceitful agitators and politicians. The publicists confronted the main allegations regarding lack of assimilation, and boasted of the positive Japanese contributions to American economy and society, especially in Hawaii and California.

European targets

Anti-German

From the 1840s to the 1920s,German Americans

German Americans (german: Deutschamerikaner, ) are Americans who have full or partial German ancestry. With an estimated size of approximately 43 million in 2019, German Americans are the largest of the self-reported ancestry groups by the Unite ...

were often distrusted because of their separatist social structure, their German-language schools, their attachment to their native tongue over English, and their neutrality during World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

.

The Bennett Law

The Bennett Law, officially chapter 519 of the 1889 acts of the Wisconsin Legislature, was a controversial state law passed by the Wisconsin Legislature in 1889 dealing with compulsory education. The controversial section of the law was a requi ...

caused a political uproar in Wisconsin

Wisconsin () is a state in the upper Midwestern United States. Wisconsin is the 25th-largest state by total area and the 20th-most populous. It is bordered by Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake M ...

in 1890, as the state government passed a law that threatened to close down hundreds of German-language elementary schools. Catholic and Lutheran Germans rallied to defeat Governor William D. Hoard

William Dempster Hoard (October 10, 1836November 22, 1918) was an American politician, newspaper publisher, and agriculture advocate who served as the 16th governor of Wisconsin from 1889 to 1891.

Hoard is called the "father of modern dairyin ...

. Hoard attacked German American culture and religion:

:"We must fight alienism and selfish ecclesiasticism.... The parents, the pastors and the church have entered into a conspiracy to darken the understanding of the children, who are denied by cupidity and bigotry the privilege of even the free schools of the state."Quoted on p. 388 of William Foote Whyte"The Bennett Law Campaign in Wisconsin,"

''Wisconsin Magazine Of History'', 10: 4 (1926–1927), p. 388 Hoard, a Republican, was defeated by the Democrats. A similar campaign in Illinois regarding the "Edwards Law" led to a Republican defeat there in 1890.

World War I

In 1917–1918, after the U.S. declared war on Germany, a wave of nativist sentiment led to the suppression of German cultural activities in the United States. There was little violence, buta few places and many streets had their names changed. Churches switched to English for their services, and German Americans were forced to buy war bonds to show their patriotism.

Former president

In 1917–1918, after the U.S. declared war on Germany, a wave of nativist sentiment led to the suppression of German cultural activities in the United States. There was little violence, buta few places and many streets had their names changed. Churches switched to English for their services, and German Americans were forced to buy war bonds to show their patriotism.

Former president Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

denounced " hyphenated Americanism", insisting that dual loyalties were impossible in wartime. The Justice Department attempted to prepare a list of all German aliens, counting approximately 480,000 of them, more than 4,000 of whom were imprisoned in 1917–18. The allegations included spying for Germany, or endorsing the German war effort. Thousands were forced to buy war bonds to show their loyalty. The Red Cross

The International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement is a Humanitarianism, humanitarian movement with approximately 97 million Volunteering, volunteers, members and staff worldwide. It was founded to protect human life and health, to ensure re ...

barred individuals with German last names from joining in fear of sabotage. One person was killed by a mob; in Collinsville, Illinois

Collinsville is a city located mainly in Madison County, and partially in St. Clair County, Illinois. As of the 2010 census, the city had a population of 25,579, an increase from 24,707 in 2000. Collinsville is approximately from St. Louis, Mi ...

, German-born Robert Prager

Robert Paul Prager (February 28, 1888 – April 5, 1918) was a German immigrant who was lynched in the United States during World War I as a result of anti-German sentiment. He had worked as a baker in southern Illinois and then as a laborer in ...

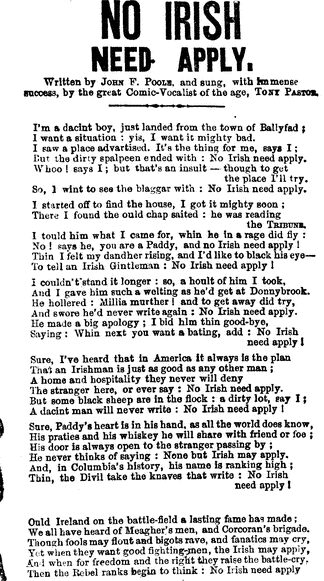

was dragged from jail as a suspected spy and lynched.Anti-Irish Catholic

Anti-Irish sentiment

Anti-Irish sentiment includes oppression, persecution, discrimination, or hatred of Irish people as an ethnic group or a nation. It can be directed against the island of Ireland in general, or directed against Irish emigrants and their descendan ...

was rampant in the United States during the 19th and early 20th Century. Rising Nativist sentiments among Protestant Americans in the 1850s led to increasing discrimination against Irish Americans. Prejudice against Irish Catholics in the U.S. reached a peak in the mid-1850s with the Know Nothing

The Know Nothing party was a nativist political party and movement in the United States in the mid-1850s. The party was officially known as the "Native American Party" prior to 1855 and thereafter, it was simply known as the "American Party". ...

Movement, which tried to oust Catholics from public office. After a year or two of local success, the Know Nothing Party vanished.

Catholics and Protestants kept their distance; intermarriage between Catholics and Protestants was uncommon, and strongly discouraged by both Protestant ministers and Catholic priests. As Dolan notes, "'Mixed marriages', as they were called, were allowed in rare cases, though warned against repeatedly, and were uncommon." Rather, intermarriage was primarily with other ethnic groups who shared their religion. Irish Catholics, for example, would commonly intermarry with German Catholics or Poles in the Midwest and Italians in the Northeast.

Irish-American journalists "scoured the cultural landscape for evidence of insults directed at the Irish in America." Much of what historians know about hostility to the Irish comes from their reports in Irish and in Democratic newspapers.

While the parishes were struggling to build parochial schools, many Catholic children attended public schools. The Protestant King James Version

The King James Version (KJV), also the King James Bible (KJB) and the Authorized Version, is an English translation of the Christian Bible for the Church of England, which was commissioned in 1604 and published in 1611, by sponsorship of K ...

of the Bible was widely used in public schools, but Catholics were forbidden by their church from reading or reciting from it. Many Irish children complained that Catholicism was openly mocked in the classroom. In New York City, the curriculum vividly portrayed Catholics, and specifically the Irish, as villainous.

The Catholic archbishop John Hughes, an immigrant to America from County Tyrone, Ireland, campaigned for public funding of Catholic education Catholic education may refer to:

* Catholic school, primary and secondary education organised by the Catholic Church or organisations affiliated with it

* Catholic university, private university run by the Catholic Church or organisations affili ...

in response to the bigotry. While never successful in obtaining public money for private education, the debate with the city's Protestant elite spurred by Hughes' passionate campaign paved the way for the secularization of public education nationwide. In addition, Catholic higher education

Catholic higher education includes universities, colleges, and other institutions of higher education privately run by the Catholic Church, typically by religious institutes. Those tied to the Holy See are specifically called pontifical univ ...

expanded during this period with colleges that evolved into such institutions as the University of Notre Dame

The University of Notre Dame du Lac, known simply as Notre Dame ( ) or ND, is a private Catholic research university in Notre Dame, Indiana, outside the city of South Bend. French priest Edward Sorin founded the school in 1842. The main c ...

, Fordham University

Fordham University () is a private Jesuit research university in New York City. Established in 1841 and named after the Fordham neighborhood of the Bronx in which its original campus is located, Fordham is the oldest Catholic and Jesuit un ...

and Boston College

Boston College (BC) is a private Jesuit research university in Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts. Founded in 1863, the university has more than 9,300 full-time undergraduates and nearly 5,000 graduate students. Although Boston College is classified ...

providing alternatives to Irish and other Catholics who avoided Protestant schools.

Stereotypes

Irish Catholics were popular targets for stereotyping in the 19th century. According to historian George Potter, the media often stereotyped the Irish in America as being boss-controlled, violent (both among themselves and with those of other ethnic groups), voting illegally, prone toalcoholism

Alcoholism is, broadly, any drinking of alcohol that results in significant mental or physical health problems. Because there is disagreement on the definition of the word ''alcoholism'', it is not a recognized diagnostic entity. Predomi ...

and dependent on street gangs that were often violent or criminal. Potter quotes contemporary newspaper images:

You will scarcely ever find an Irishman dabbling in counterfeit money, or breaking into houses, or swindling; but if there is any fighting to be done, he is very apt to have a hand in it." Even though Pat might "'meet with a friend and for love knock him down,'" noted aMontreal Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the second-most populous city in Canada and most populous city in the Canadian province of Quebec. Founded in 1642 as '' Ville-Marie'', or "City of Mary", it is named after Mount Royal, the triple- ...paper, the fighting usually resulted from a sudden excitement, allowing there was "but little 'malice prepense' in his whole composition." The ''Catholic Telegraph'' ofCincinnati Cincinnati ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located at the northern side of the confluence of the Licking and Ohio rivers, the latter of which marks the state line w ...in 1853, saying that the "name of 'Irish' has become identified in the minds of many, with almost every species of outlawry," distinguished the Irish vices as "not of a deep malignant nature," arising rather from the "transient burst of undisciplined passion," like "drunk, disorderly, fighting, etc., not like robbery, cheating, swindling, counterfeiting, slandering, calumniating, blasphemy, using obscene language, &c.

The Irish had many humorists of their own, but were scathingly attacked in political cartoons, especially those in ''Puck'' magazine from the 1870s to 1900; it was edited by secular Germans who opposed the Catholic Irish in politics. In addition, the cartoons of

The Irish had many humorists of their own, but were scathingly attacked in political cartoons, especially those in ''Puck'' magazine from the 1870s to 1900; it was edited by secular Germans who opposed the Catholic Irish in politics. In addition, the cartoons of Thomas Nast

Thomas Nast (; ; September 26, 1840December 7, 1902) was a German-born American caricaturist and editorial cartoonist often considered to be the "Father of the American Cartoon".

He was a critic of Democratic Representative "Boss" Tweed and ...

were especially hostile; for example, he depicted the Irish-dominated Tammany Hall

Tammany Hall, also known as the Society of St. Tammany, the Sons of St. Tammany, or the Columbian Order, was a New York City political organization founded in 1786 and incorporated on May 12, 1789 as the Tammany Society. It became the main loc ...

machine in New York City as a ferocious tiger.

The stereotype of the Irish as violent drunks has lasted well beyond its high point in the mid-19th century. For example, President Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

once told advisor Charles Colson

Charles Wendell Colson (October 16, 1931 – April 21, 2012), generally referred to as Chuck Colson, was an American attorney and political advisor who served as Special Counsel to President Richard Nixon from 1969 to 1970. Once known as P ...

that " e Irish have certain — for example, the Irish can't drink. What you always have to remember with the Irish is they get mean. Virtually every Irish I've known gets mean when he drinks. Particularly the real Irish."

Attitudes regarding Irish Catholics depended on gender. Irish women were sometimes stereotyped as "reckless breeders" because some American Protestants feared high Catholic birth rates would eventually result in a Protestant minority. Many native-born Americans claimed that "their incessant childbearing ouldensure an Irish political takeover of American cities nd thatCatholicism would become the reigning faith of the hitherto Protestant nation." Irish men were also targeted, but in a different way than women were. The difference between the Irish female "Bridget" and the Irish male "Pat" was distinct; while she was impulsive but fairly harmless, he was "always drunk, eternally fighting, lazy, and shiftless". In contrast to the view that Irish women were shiftless, slovenly and stupid (like their male counterparts), girls were said to be "industrious, willing, cheerful, and honest—they work hard, and they are very strictly moral".

The Irish as trouble makers was a belief held by many Americans. This notion was held due to the fact that the Irish topped the charts demographically in terms of arrests and imprisonment. They also had more people confined to insane asylum

The lunatic asylum (or insane asylum) was an early precursor of the modern psychiatric hospital.

The fall of the lunatic asylum and its eventual replacement by modern psychiatric hospitals explains the rise of organized, institutional psychiatry ...

s and poorhouse

A poorhouse or workhouse is a government-run (usually by a county or municipality) facility to support and provide housing for the dependent or needy.

Workhouses

In England, Wales and Ireland (but not in Scotland), ‘workhouse’ has been the ...

s than any other group. From the 1860s onwards, Irish Americans were stereotyped as terrorists and gangsters, although this stereotyping began to diminish by the end of the 19th century.

Anti-Jewish

Steady immigration, especially from Germany, increased the size of the Jewish population from 1500 in the 1770s to 250,000 by the 1860s. According toHasia Diner

Hasia Diner

Hasia R. Diner is an American historian. Diner is the Paul S. and Sylvia Steinberg Professor of American Jewish History; Professor of Hebrew and Judaic Studies, History; Director of the Goldstein-Goren Center for American Jewish Hi ...

: " In large measure due to the fact that itinerant peddlers, young men willing to go anywhere, served as the juggernauts of Jewish migration, Jews penetrated every region for commercial purposes and made possible Jewish life in every large city and in hundreds upon hundreds of small towns." Down to the 1860s, according to Jonathan Sarna

Jonathan D. Sarna (born 10 January 1955) is the Joseph H. and Belle R. Braun Professor of American Jewish History in the department of Near Eastern and Judaic Studies and director othe Schusterman Center for Israel Studies at Brandeis Universit ...

, actual relations with Gentiles were generally positive despite a backdrop of old popular prejudices:From colonial days onward, Jews and Christians cooperated with one another, maintaining close social and economic relations. Intermarriage rates, a reliable if unwelcome sign of religious harmony, periodically rose to high levels. And individual Jews thrived, often rising to positions of wealth and power. Yet popular prejudice based on received wisdom continued nonetheless.... In the Civil War as before, Jews in general suffered because of what the word "Jew" symbolized, while individual Jews won the respect of their fellow citizens and emerged from the fratricidal struggle more self-assured than they had ever been before.In 1862 during the Civil War, General

Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union A ...

issued an order (quickly rescinded by President Abraham Lincoln) of expulsion against Jews from the portions of Tennessee, Kentucky and Mississippi which were under his control. (''See General Order No. 11'') As president in 1869-1877, however, Grant was especially favorable to Jews.

The 1870s marked a turning point as the first of two million Jews from Eastern Europe arrived. They spoke Yiddish (a form of German), were quite poor, and concentrated in New York City where they soon dominated the garment industry. They built a Yiddish theatre system that eventually spun off the Hollywood movie studios. Unlike the politically conservative earlier arrivals, they were radical and often Socialist or even Communist.

Antisemitic discrimination by old American elites emerged in the 1870s. Upper class Jews were no longer allowed to join some social clubs nor stay in some fancy resorts; their enrollment at elite colleges was limited by quotas, and they were also not allowed to buy houses in certain neighborhoods. In response, Jews established their own country clubs

A country club is a privately owned club, often with a membership quota and admittance by invitation or sponsorship, that generally offers both a variety of recreational sports and facilities for dining and entertaining. Typical athletic offe ...

, summer resorts, and universities, such as Brandeis Brandeis is a surname. People

*Antonietta Brandeis (1848–1926), Czech-born Italian painter

*Brandeis Marshall, American data scientist

* Friedl Dicker-Brandeis, Austrian artist and Holocaust victim

* Irma Brandeis, American Dante scholar

*Louis ...

. Antisemitic attitudes in America reached its peak during the interwar period. The sudden rise of the second Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and Cat ...

in the mid 1920s, the antisemitic works of Henry Ford

Henry Ford (July 30, 1863 – April 7, 1947) was an American industrialist, business magnate, founder of the Ford Motor Company, and chief developer of the assembly line technique of mass production. By creating the first automobile that ...

, and the radio attacks of Father Coughlin

Charles Edward Coughlin ( ; October 25, 1891 – October 27, 1979), commonly known as Father Coughlin, was a Canadian-American Catholic priest based in the United States near Detroit. He was the founding priest of the National Shrine of th ...

in the late 1930s generated tensions nationwide.

Actual elite-level discrimination was at a much milder level than Europe. Sarna argues: "American politics resists anti-Semitism....The politics of hatred have thus largely been confined to noisy third parties and single issue fringe groups. When anti-Semitism is introduced into the political arena...major candidates generally repudiate it." Thus no major American party or major national politician was openly antisemitic. Perhaps the most notorious outlier was John E. Rankin

John Elliott Rankin (March 29, 1882 – November 26, 1960) was a Democratic politician from Mississippi who served sixteen terms in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1921 to 1953. He was co-author of the bill for the Tennessee Valley A ...

of Mississippi, an outspoken enemy of all minorities for three decades in Congress, 1921 to 1953.

After 1945 anti-Jewish sentiment among whites steadily declined both at the elite and the popular level. However, some leaders of Black Nationalist

Black nationalism is a type of racial nationalism or pan-nationalism which espouses the belief that black people are a race, and which seeks to develop and maintain a black racial and national identity. Black nationalist activism revolves aro ...

organizations, especially the Nation of Islam

The Nation of Islam (NOI) is a religious and political organization founded in the United States by Wallace Fard Muhammad in 1930.

A black nationalist organization, the NOI focuses its attention on the African diaspora, especially on African ...

, accused Jews of exploiting black laborers, profiteering by bringing alcohol and drugs into black communities, and unfairly dominating the local economy. According to annual surveys by the Anti-Defamation League, for each race, there is a strong correlation between level of education and rejection of antisemitic stereotypes

Antisemitic tropes, canards, or myths are "Sensationalism, sensational reports, misrepresentations, or Fabrication (lie), fabrications" that are Defamation, defamatory towards Judaism as a religion or defamatory towards Jews as an Ethnic group, ...

. However, black Americans of all education levels are significantly more likely to be antisemitic than whites who are of the same education level. In the 1998 survey, blacks (34%) were nearly four times more likely (9%) to fall into the most antisemitic category (those who agreed with at least 6 out of 11 statements that were potentially or clearly antisemitic) than whites were. Among blacks with no college education, 43% of them fell into the most antisemitic group (vs. 18% of the general population), which fell to 27% among blacks with some college education, and 18% among blacks with a four-year college degree (vs. 5% of the general population). The most prominent black leader of the 1980s, Jesse Jackson

Jesse Louis Jackson (né Burns; born October 8, 1941) is an American political activist, Baptist minister, and politician. He was a candidate for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1984 and 1988 and served as a shadow U.S. senato ...

, repeatedly denied accusations that he was antisemitic.

The 2005 Anti-Defamation League survey includes data on the attitudes of Hispanics

The term ''Hispanic'' ( es, hispano) refers to people, cultures, or countries related to Spain, the Spanish language, or Hispanidad.

The term commonly applies to countries with a cultural and historical link to Spain and to viceroyalties for ...

, with 29% of Hispanics being the most antisemitic (vs. 9% of whites and 36% of blacks); being born in the United States helped alleviate this attitude: 35% of foreign-born Hispanics were antisemitic, but only 19% of those Hispanics who were born in the U.S. were antisemitic.

A ''Time

Time is the continued sequence of existence and event (philosophy), events that occurs in an apparently irreversible process, irreversible succession from the past, through the present, into the future. It is a component quantity of various me ...

'' poll of 1000 individuals which was conducted in August 2010 indicated that only 13 percent of Americans have unfavorable views of Jews, by contrast, 43 percent have unfavorable views of Muslims; 17 percent have unfavorable views of Catholics; and 29 percent have unfavorable views of Mormons. By contrast, antisemitic attitudes are much higher in Europe and are growing.

In September 2014, the ''New York Post

The ''New York Post'' (''NY Post'') is a conservative daily tabloid newspaper published in New York City. The ''Post'' also operates NYPost.com, the celebrity gossip site PageSix.com, and the entertainment site Decider.com.

It was established ...

'' released the contents of a report which was originally published by the NYPD

The New York City Police Department (NYPD), officially the City of New York Police Department, established on May 23, 1845, is the primary municipal law enforcement agency within the City of New York, the largest and one of the oldest in ...

. The report stated that since 2013, the number of antisemitic incidents in the city had increased by 35%. On the other hand, a report of the Los Angeles County Commission on Human Relations revealed a significant decrease of 48 percent in anti-Jewish crimes in LA compared to 2013.

A 2014 survey of 1,157 Jewish students at 55 campuses nationwide found that 54 percent had been subjected to or had witnessed antisemitism on their campuses. The most significant origin for antisemitism was "from an individual student" (29 percent). Other origins were in clubs or societies, in lectures and classes, and in student unions. The findings of the research were similar to a parallel study conducted in the United Kingdom.

Antisemitism in the United States has rarely erupted into physical violence against Jews. Some of the worst episodes include the attack on the funeral procession of Rabbi Jacob Joseph by Irish workers and police in New York City in 1902; the lynching of Leo Frank

Leo Max Frank (April 17, 1884August 17, 1915) was an American factory superintendent who was convicted in 1913 of the murder of a 13-year-old employee, Mary Phagan, in Atlanta, Georgia. His trial, conviction, and appeals attracted national at ...

in Georgia in 1915; beatings of numerous Jews in Boston and New York by Irish gangs in 1943-1944; the murder of talk radio host Alan Berg

Alan Harrison Berg (January 18, 1934 – June 18, 1984) was an American talk radio show host in Denver, Colorado. Born to a Jewish family, he had outspoken atheistic and liberal views and a confrontational interview style. Berg was murdered b ...

in Denver in 1984; the Crown Heights riot

The Crown Heights riot was a race riot that took place from August 19 to August 21, 1991, in the Crown Heights section of Brooklyn, New York City. Black residents attacked orthodox Jewish residents, damaged their homes, and looted businesses. Th ...

in Brooklyn in 1991; and the murder of 11 congregants in the Pittsburgh synagogue shooting

The Pittsburgh synagogue shooting was an antisemitic terrorist attack which took place at the Tree of Life – Or L'Simcha Congregation synagogue in the Squirrel Hill neighborhood of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, United States. The congregation, al ...

of October 2018.

Hispanic targets

According to Phillip Gonzales, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries Hispanics in New Mexico frequently organized "juntas de indignación", which were protests against discrimination. Hundreds attended meetings that protested housing discrimination; Washington's perception of "backwardness" in the territory that delayed statehood; racist comments by government officials; and admission policies at the University of New Mexico. The protest style ended in the 1930s.Trump's immigration policy

The proposed immigration policies of presidential candidate Donald Trump opened a bitter and contentious debate during the 2016 campaign. He promised to build a wall on the Mexico–United States border to restrict illegal movement and vowed Mexico would pay for it. He pledged to deport millions of illegal immigrants residing in the United States, and criticizedbirthright citizenship

''Jus soli'' ( , , ; meaning "right of soil"), commonly referred to as birthright citizenship, is the right of anyone born in the territory of a state to nationality or citizenship.

''Jus soli'' was part of the English common law, in contras ...

for incentivizing "anchor babies

Anchor baby is a term (regarded by some as a pejorative) used to refer to a child born to a non-citizen mother in a country that has birthright citizenship which will therefore help the mother and other family members gain legal residency. In the ...

". As president, he frequently described illegal immigration as an "invasion" and conflated immigrants with the criminal gang MS-13

Mara Salvatrucha, commonly known as MS-13, is an international criminal gang that originated in Los Angeles, California, in the 1970s and 1980s. Originally, the gang was set up to protect Salvadoran immigrants from other gangs in the Los Ange ...

, though research shows undocumented immigrants

Illegal immigration is the migration of people into a country in violation of the immigration laws of that country or the continued residence without the legal right to live in that country. Illegal immigration tends to be financially upwar ...

have a lower crime rate than native-born Americans.

Trump attempted to drastically escalate immigration enforcement, including implementing harsher immigration enforcement policies against asylum seekers from Central America than any modern U.S. president.

From 2018 onwards, Trump deployed nearly 6,000 troops to the U.S.–Mexico border, to stop most Central American migrants from seeking U.S. asylum, and from 2020 used the public charge rule

Under the public charge rule, immigrants to United States classified as Likely or Liable to become a Public Charge may be denied visas or permission to enter the country due to their disabilities or lack of economic resources. The term was i ...

to restrict immigrants using government benefits from getting permanent residency via green card

A green card, known officially as a permanent resident card, is an identity document which shows that a person has permanent residency in the United States. ("The term 'lawfully admitted for permanent residence' means the status of having been ...

s. Trump has reduced the number of refugees admitted into the U.S. to record lows. When Trump took office, the annual limit was 110,000; Trump set a limit of 18,000 in the 2020 fiscal year and 15,000 in the 2021 fiscal year. Additional restrictions implemented by the Trump administration caused significant bottlenecks in processing refugee applications, resulting in fewer refugees accepted compared to the allowed limits.

Mexican border wall

One of presidential candidate Donald Trump's central campaign promises in 2016 was to build a 1,000-mile border wall to Mexico and have Mexico pay for it. By the end of his term, the U.S. had built 73 miles of primary and secondary wall in new locations, and 365 miles of fencing replacing outdated barriers. In February 2019, Congress passed and Trump signed a funding bill that included $1.375 billion for 55 miles of bollard border fencing. Trump also declared a

One of presidential candidate Donald Trump's central campaign promises in 2016 was to build a 1,000-mile border wall to Mexico and have Mexico pay for it. By the end of his term, the U.S. had built 73 miles of primary and secondary wall in new locations, and 365 miles of fencing replacing outdated barriers. In February 2019, Congress passed and Trump signed a funding bill that included $1.375 billion for 55 miles of bollard border fencing. Trump also declared a National Emergency Concerning the Southern Border of the United States

The National Emergency Concerning the Southern Border of the United States (Proclamation 9844) was declared on February 15, 2019, by President of the United States Donald Trump. Citing the National Emergencies Act, it ordered the diversion of bil ...

, intending to divert $6.1 billion of funds Congress had allocated to other purposes. The House and the Senate attempted to block Trump's national emergency declaration, but there were not enough votes for a veto override

A veto is a legal power to unilaterally stop an official action. In the most typical case, a president or monarch vetoes a bill to stop it from becoming law. In many countries, veto powers are established in the country's constitution. Veto po ...

.

20th century

According to Erika Lee, in the 1890s the old stock Yankee upper-class founders of theImmigration Restriction League

The Immigration Restriction League was an American nativist and anti-immigration organization founded by Charles Warren, Robert DeCourcy Ward, and Prescott F. Hall in 1894. According to Erika Lee, in 1894 the old stock Yankee upper-class found ...

were, “convinced that Anglo-Saxon traditions, peoples, and culture were being drowned in a flood of racially inferior foreigners from Southern and Eastern Europe.”

In the 1890s–1920s era, nativists and labor unions campaigned for immigration restriction following the waves of workers and families from Southern and Eastern Europe, including the Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy ( it, Regno d'Italia) was a state that existed from 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Kingdom of Sardinia, Sardinia was proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, proclaimed King of Italy, until 1946, when civil discontent led to ...

, the Balkans

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

, Poland, Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

, and the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War ...

. A favorite plan was the literacy test

A literacy test assesses a person's literacy skills: their ability to read and write have been administered by various governments, particularly to immigrants. In the United States, between the 1850s and 1960s, literacy tests were administered ...

to exclude workers who could not read or write their own foreign language. Congress passed literacy tests, but presidents—responding to business needs for workers—vetoed them. Senator Henry Cabot Lodge

Henry Cabot Lodge (May 12, 1850 November 9, 1924) was an American Republican politician, historian, and statesman from Massachusetts. He served in the United States Senate from 1893 to 1924 and is best known for his positions on foreign polic ...

argued the need for literacy tests, and described its implication on the new immigrants:

Responding to these demands, opponents of the literacy test called for the establishment of an immigration commission to focus on immigration as a whole. The United States Immigration Commission, also known as the Dillingham Commission

The United States Immigration Commission (also known as the Dillingham Commission after its chairman, Republican Senator William P. Dillingham of Vermont) was a bipartisan special committee formed in February 1907 by the United States Congress, P ...

, was created and tasked with studying immigration and its effect on the United States. The findings of the commission further influenced immigration policy and upheld the concerns of the nativist movement. Political forces

The goal of the political forces which existed during the Progressive Era was to create special purpose organizations that would bring activists together and motivate them to achieve specific goals. TheImmigration Restriction League

The Immigration Restriction League was an American nativist and anti-immigration organization founded by Charles Warren, Robert DeCourcy Ward, and Prescott F. Hall in 1894. According to Erika Lee, in 1894 the old stock Yankee upper-class found ...

was especially active in setting up chapters, and it was also active in forming working and cooperative arrangements with a range of good government groups, labor unions, and prohibitionists. On the other side, multiple organizations also existed. The National German-American Alliance, funded by the beer industry, played a leadership role in opposing prohibition and women's suffrage in the Midwest. The Ancient Order of Hibernians

The Ancient Order of Hibernians (AOH; ) is an Irish Catholic fraternal organization. Members must be male, Catholic, and either born in Ireland or of Irish descent. Its largest membership is now in the United States, where it was founded in N ...

had an urban presence among politically active Irish Catholics. The Irish-controlled Democratic machines in big cities represented the new immigrants at the local level and they also opposed prohibition and women's suffrage. The Jewish community also began to lobby against restrictions on immigration, because pogroms in Russia and restricted opportunities in much of Europe made the United States a highly attractive destination for millions of Eastern European Jews. A powerful influence came from big business and heavy industry, such as steel and mining, because they depended on cheap immigrant labor; steamship companies also helped out. As a result, the restrictionists were outnumbered and outmaneuvered until the United States entered the war as an ally of Great Britain, an enemy of Germany. During the war, almost all immigration from Europe was haulted. Additionally, German Americans were considered pariahs; the National German-American Alliance was forced to disband. Furthermore, the anti-British and anti-dry Irish factor was also weakened. The new configuration also allowed the women's movement to gain enough support to put suffrage over the top, and it also succeeded in making the final push towards national prohibition. Immigration restriction now gained the necessary momentum and it continued to build until its final victory in 1924.

1920s

In the early 1920s, the Second Ku Klux Klan, promoted an explicitly nativist,anti-Catholic

Anti-Catholicism is hostility towards Catholics or opposition to the Catholic Church, its clergy, and/or its adherents. At various points after the Reformation, some majority Protestant states, including England, Prussia, Scotland, and the Uni ...

, and anti-Jewish

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

stance. The racial concern of the anti-immigration movement was linked to the eugenics movement that was active during the same period. Led by Madison Grant's book, ''The Passing of the Great Race

''The Passing of the Great Race: Or, The Racial Basis of European History'' is a 1916 racist and pseudoscientific book by American lawyer, self-styled anthropologist, and proponent of eugenics, Madison Grant (1865–1937). Grant expounds a theo ...

'' nativists grew more concerned with the racial purity

The term racial hygiene was used to describe an approach to eugenics in the early 20th century, which found its most extensive implementation in Nazi Germany (Nazi eugenics). It was marked by efforts to avoid miscegenation, analogous to an animal ...

of the United States. In his book, Grant argued that the American racial stock was being diluted by the influx of new immigrants from the Mediterranean, Ireland, the Balkans, and the ghettos. ''The Passing of the Great Race'' reached wide popularity among Americans and influenced immigration policy in the 1920s.

In the 1920s, a wide national consensus sharply restricted the overall inflow of immigrants from southern and eastern Europe. After intense lobbying from the nativist movement, Congress passed the Emergency Quota Act

__NOTOC__

The Emergency Quota Act, also known as the Emergency Immigration Act of 1921, the Immigration Restriction Act of 1921, the Per Centum Law, and the Johnson Quota Act (ch. 8, of May 19, 1921), was formulated mainly in response to the larg ...

in 1921. This bill was the first to place numerical quotas on immigration. It capped the inflow of immigrations to 357,803 for those arriving outside of the western hemisphere. However, this bill was only temporary, as Congress began debating a more permanent bill. The Emergency Quota Act was followed with the Immigration Act of 1924

The Immigration Act of 1924, or Johnson–Reed Act, including the Asian Exclusion Act and National Origins Act (), was a United States federal law that prevented immigration from Asia and set quotas on the number of immigrants from the Eastern ...

, a more permanent resolution. This law reduced the number of immigrants able to arrive from 357,803, the number established in the Emergency Quota Act, to 164,687. Though this bill did not fully restrict immigration, it considerably curbed the flow of immigration from Southern and Eastern Europe.

Late 20th century

Animmigration reduction

Opposition to immigration, also known as anti-immigration, has become a significant political ideology in many countries. In the modern sense, immigration refers to the entry of people from one state or territory into another state or territory ...

ism movement was formed in the 1970s and it continues to exist in the present day. Prominent members of it often press for massive, sometimes total, reductions in immigration levels. American nativist sentiment experienced a resurgence in the late 20th century, this time, it was directed at undocumented workers

Illegal immigration is the migration of people into a country in violation of the immigration laws of that country or the continued residence without the legal right to live in that country. Illegal immigration tends to be financially upwar ...

, mostly Mexicans

Mexicans ( es, mexicanos) are the citizens of the United Mexican States.

The most spoken language by Mexicans is Spanish, but some may also speak languages from 68 different Indigenous linguistic groups and other languages brought to Mexi ...

, resulting in the passage of new penalties against illegal immigration in 1996. Most immigration reductionists see illegal immigration

Illegal immigration is the migration of people into a country in violation of the immigration laws of that country or the continued residence without the legal right to live in that country. Illegal immigration tends to be financially upwar ...

, principally from across the United States–Mexico border

United may refer to:

Places

* United, Pennsylvania, an unincorporated community

* United, West Virginia, an unincorporated community

Arts and entertainment Films

* ''United'' (2003 film), a Norwegian film

* ''United'' (2011 film), a BBC Two fi ...

, as the most pressing concern. Authors such as Samuel Huntington have also portrayed recent Hispanic immigration as causing a national identity crisis and they have also portrayed it as causing insurmountable problems for social institutions in the US.

21st century

By late 2014, the "Tea Party movement

The Tea Party movement was an American fiscally conservative political movement within the Republican Party that began in 2009. Members of the movement called for lower taxes and for a reduction of the national debt and federal budget def ...

" had turned its focus away from economic issues, and towards attacking President Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II ( ; born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who served as the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, Obama was the first Af ...

's immigration policies, which it saw as a threat to transform American society. The Tea Party tries to defeat Republicans who supported immigration programs, especially Senator John McCain