Nationalism In Pakistan on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Pakistani nationalism refers to the political,

Pakistani nationalism refers to the political,

The roots of Pakistani nationalism lie in the separatist campaign of the Muslim League in

The roots of Pakistani nationalism lie in the separatist campaign of the Muslim League in  The

The

Because of the country's identity with Islam, mosques like

Because of the country's identity with Islam, mosques like

The intense

The intense

cultural

Culture () is an umbrella term which encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and Social norm, norms found in human Society, societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, Social norm, customs, capabilities, and habits of the ...

, linguistic

Linguistics is the scientific study of human language. It is called a scientific study because it entails a comprehensive, systematic, objective, and precise analysis of all aspects of language, particularly its nature and structure. Linguis ...

, historical

History (derived ) is the systematic study and the documentation of the human activity. The time period of event before the invention of writing systems is considered prehistory. "History" is an umbrella term comprising past events as well ...

, ommonlyreligious

Religion is usually defined as a social system, social-cultural system of designated religious behaviour, behaviors and practices, morality, morals, beliefs, worldviews, religious text, texts, sacred site, sanctified places, prophecy, prophecie ...

and geographical

Geography (from Greek: , ''geographia''. Combination of Greek words ‘Geo’ (The Earth) and ‘Graphien’ (to describe), literally "earth description") is a field of science devoted to the study of the lands, features, inhabitants, and ...

expression of patriotism

Patriotism is the feeling of love, devotion, and sense of attachment to one's country. This attachment can be a combination of many different feelings, language relating to one's own homeland, including ethnic, cultural, political or histor ...

by the people of Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 24 ...

, of pride in the history, heritage

Heritage may refer to:

History and society

* A heritage asset is a preexisting thing of value today

** Cultural heritage is created by humans

** Natural heritage is not

* Heritage language

Biology

* Heredity, biological inheritance of physical c ...

and identity

Identity may refer to:

* Identity document

* Identity (philosophy)

* Identity (social science)

* Identity (mathematics)

Arts and entertainment Film and television

* ''Identity'' (1987 film), an Iranian film

* ''Identity'' (2003 film), ...

of Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 24 ...

, and visions for its future.

Unlike the secular

Secularity, also the secular or secularness (from Latin ''saeculum'', "worldly" or "of a generation"), is the state of being unrelated or neutral in regards to religion. Anything that does not have an explicit reference to religion, either negativ ...

nationalism

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a in-group and out-group, group of peo ...

of most other countries, Pakistani nationalism is religious

Religion is usually defined as a social system, social-cultural system of designated religious behaviour, behaviors and practices, morality, morals, beliefs, worldviews, religious text, texts, sacred site, sanctified places, prophecy, prophecie ...

in nature of being the nationalism for the culture, traditions, languages and historical region that makes up Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 24 ...

, inhabited by mostly Muslims. The culture, langauges, literature, history of the region along with influence of Islam was the basis of Pakistani nationalist narrative. (see Secularism in Pakistan

The concept of the Two-Nation Theory on which Pakistan was founded, was largely based on Muslim nationalism. The supporters of Islamisation assert that Pakistan was founded as a Muslim state and that in its status as an Islamic republic, it mus ...

)

From a political point of view and in the years leading up to the independence of Pakistan, the particular political and ideological foundations for the actions of the Muslim League Muslim League may refer to:

Political parties Subcontinent

; British India

*All-India Muslim League, Mohammed Ali Jinah, led the demand for the partition of India resulting in the creation of Pakistan.

**Punjab Muslim League, a branch of the organ ...

can be called a Pakistani nationalist ideology. It is a singular combination of philosophical, nationalistic, cultural and religious elements.

National consciousness in Pakistan

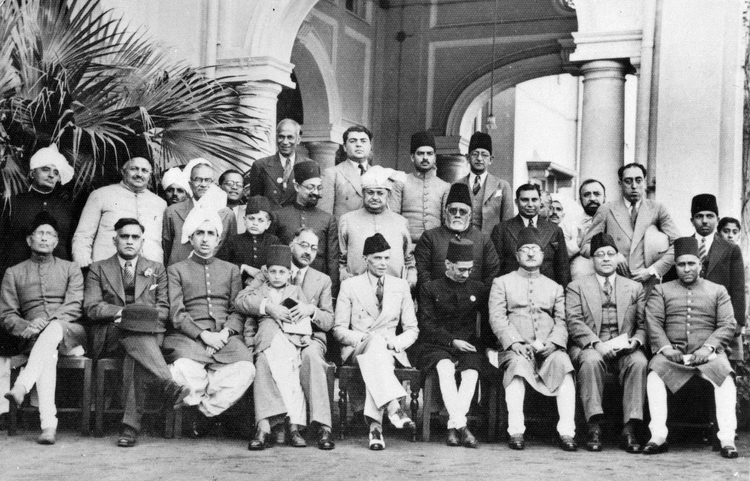

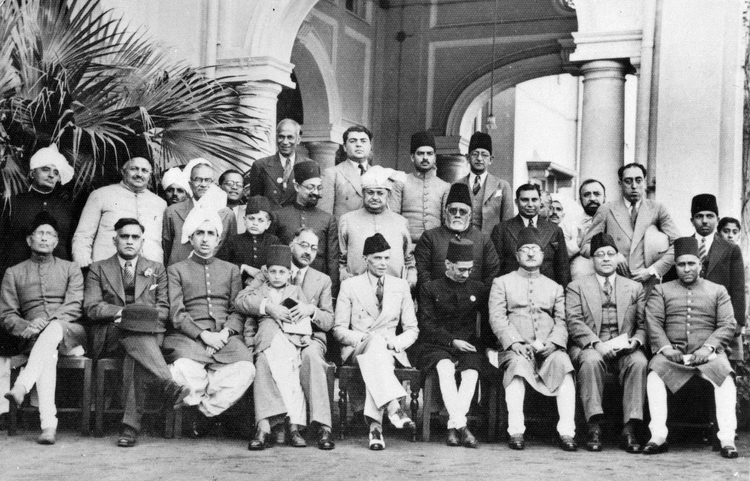

Muslim League separatist campaign in Colonial India

The roots of Pakistani nationalism lie in the separatist campaign of the Muslim League in

The roots of Pakistani nationalism lie in the separatist campaign of the Muslim League in British India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance on the Indian subcontinent. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one ...

, which sought to create a new state for Indian Muslims called Pakistan, on the basis of Islam. This concept of a separate state for India's Muslims traces its roots to Allama Iqbal

Sir Muhammad Iqbal ( ur, ; 9 November 187721 April 1938), was a South Asian Muslim writer, philosopher, Quote: "In Persian, ... he published six volumes of mainly long poems between 1915 and 1936, ... more or less complete works on philoso ...

, who has retroactively been dubbed the national poet of Pakistan. Iqbal was elected president of the Muslim League in 1930 at its session in Allahabad

Allahabad (), officially known as Prayagraj, also known as Ilahabad, is a metropolis in the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh.The other five cities were: Agra, Kanpur (Cawnpore), Lucknow, Meerut, and Varanasi (Benares). It is the administrat ...

in the United Provinces, as well as for the session in Lahore in 1932. In his presidential address on 29 December 1930 he outlined a vision of an independent state for Muslim-majority provinces in north-western India:

For a large majority of the Muslim intelligentsia, including Iqbal, Indo-Muslim culture became a rallying ground for making the case for a separate Muslim homeland. The concept of Indo-Muslim culture was based on the development of a separate political and cultural identity during Muslim rule which built upon the merging of Persian and Indic languages, literature and arts. According to Iqbal, the uppermost purpose of establishing a separate country was the preservation of the Muslim "cultural entity", which he believed would not be safe under the rule of the Hindu majority. Syed Ahmed Khan

Sir Syed Ahmad Khan KCSI (17 October 1817 – 27 March 1898; also Sayyid Ahmad Khan) was an Indian Muslim reformer, philosopher, and educationist in nineteenth-century British India. Though initially espousing Hindu-Muslim unity, he ...

, the grandson of the Mughal Vizier

A vizier (; ar, وزير, wazīr; fa, وزیر, vazīr), or wazir, is a high-ranking political advisor or minister in the near east. The Abbasid caliphs gave the title ''wazir'' to a minister formerly called ''katib'' (secretary), who was a ...

, Dabir-ud-Daulah, emphasized that Muslims and Hindus made up two different nations on the basis that Hindus were not ready to accept the contemporary Muslim culture

Islamic culture and Muslim culture refer to cultural practices which are common to historically Islamic people. The early forms of Muslim culture, from the Rashidun Caliphate to the early Umayyad period and the early Abbasid period, were predomi ...

and tradition which was exemplified by Hindu opposition to the Urdu language

Urdu (;"Urdu"

''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. ur, , link=no, ) is an Indo-Aryan languages, In ...

.

The assumption of the Muslims of India of belonging to a separate identity, and therefore, having a right to their own country, also rested on their pre-eminent claim to political power, which flowed from the experience of Muslim dominance in India.

Historians such as ''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. ur, , link=no, ) is an Indo-Aryan languages, In ...

Shashi Tharoor

Shashi Tharoor (; ; born 9 March 1956 in London, England ) is an Indian former international civil servant, diplomat, bureaucrat and politician, writer and public intellectual who has been serving as Member of Parliament for Thiruvananthapuram, ...

maintain that the British government's divide-and-rule policies in India were established after witnessing Hindus and Muslims joining forces together to fight against Company rule in India

Company rule in India (sometimes, Company ''Raj'', from hi, rāj, lit=rule) refers to the rule of the British East India Company on the Indian subcontinent. This is variously taken to have commenced in 1757, after the Battle of Plassey, when ...

during the Indian Rebellion of 1857

The Indian Rebellion of 1857 was a major uprising in India in 1857–58 against the rule of the British East India Company, which functioned as a sovereign power on behalf of the British Crown. The rebellion began on 10 May 1857 in the fo ...

. The demand for the creation of Pakistan as a homeland for Indian Muslims, according to many academics, was orchestrated mainly by the elite class of Muslims in colonial India primarily based in the United Provinces (U.P.) and Bihar

Bihar (; ) is a state in eastern India. It is the 2nd largest state by population in 2019, 12th largest by area of , and 14th largest by GDP in 2021. Bihar borders Uttar Pradesh to its west, Nepal to the north, the northern part of West Be ...

who supported the All India Muslim League

The All-India Muslim League (AIML) was a political party established in Dhaka in 1906 when a group of prominent Muslim politicians met the Viceroy of British India, Lord Minto, with the goal of securing Muslim interests on the Indian subcontin ...

, rather the common Indian Muslim.

In the colonial Indian province of Sind

Sindh (; ; ur, , ; historically romanized as Sind) is one of the four provinces of Pakistan. Located in the southeastern region of the country, Sindh is the third-largest province of Pakistan by land area and the second-largest province ...

, the historian Ayesha Jalal

Ayesha Jalal ( Punjabi, ur, ) is a Pakistani-American historian who serves as the Mary Richardson Professor of History at Tufts University, and was the recipient of the 1998 MacArthur Foundation Fellowship.

Family and early life

Ayesha Jala ...

describes the actions that Jinnah's pro-separatist Muslim League used in order to spread communal division and undermine the government of Allah Bakhsh Soomro

Allah Bux Muhammad Umar Soomro ( sd, اللهَ بخشُ سوُمَرو) (1900 – 14 May 1943), ( Khan Bahadur Sir Allah Bux Muhammad Umar Soomro OBE till September 1942) or Allah Baksh Soomro, was a ''zamindar'', government contractor, Ind ...

, which stood for a united India:

The Muslim League, seeking to spread religious strife, "monetarily subsidized" mobs that engaged in communal violence against Hindus and Sikhs in the areas of Multan, Rawalpindi, Campbellpur, Jhelum and Sargodha, as well as in the Hazara District

Hazara District was a district of Peshawar Division in the North-West Frontier Province of Pakistan. It existed until 1976, when it was split into the districts of Abbottabad and Mansehra, with the new district of Haripur subsequently splitting of ...

. Jinnah and the Muslim League's communalistic Direct Action Day

Direct Action Day (16 August 1946), also known as the 1946 Calcutta Killings, was a day of nationwide communal riots. It led to large-scale violence between Muslims and Hindus in the city of Calcutta (now known as Kolkata) in the Bengal prov ...

in Calcutta

Kolkata (, or , ; also known as Calcutta , List of renamed places in India#West Bengal, the official name until 2001) is the Capital city, capital of the Indian States and union territories of India, state of West Bengal, on the eastern ba ...

resulted in 4,000 deaths and 100,000 residents left homeless in just 72 hours, sowing the seeds for riots in other provinces and the eventual partition of the country.

The

The Ahmadiyya Muslim Jama'at

Ahmadiyya (, ), officially the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community or the Ahmadiyya Muslim Jama'at (AMJ, ar, الجماعة الإسلامية الأحمدية, al-Jamāʿah al-Islāmīyah al-Aḥmadīyah; ur, , translit=Jamā'at Aḥmadiyyah Musl ...

staunchly supported Jinnah's separatist demand for Pakistan. Chaudary Zafarullah Khan, an Ahmadi leader, drafted the Lahore Resolution

The Lahore Resolution ( ur, , ''Qarardad-e-Lahore''; Bengali: লাহোর প্রস্তাব, ''Lahor Prostab''), also called Pakistan resolution, was written and prepared by Muhammad Zafarullah Khan and was presented by A. K. Fazlul ...

that separatist leaders interpreted as calling for the creation of Pakistan. Chaudary Zafarullah Khan was asked by Jinnah to represent the Muslim League to the Radcliffe Commission, which was charged with drawing the line between an independent India and newly created Pakistan. Ahmadis argued to try to ensure that the city of Qadian, India

Qadian (; ; ) is a city and a municipal council in Gurdaspur district, north-east of Amritsar, situated north-east of Batala city in the state of Punjab, India.

Qadian is the birthplace of Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, the founder of the Ahmadiyya mov ...

would fall into the newly created state of Pakistan, though they were unsuccessful in doing so. Upon the creation of Pakistan, many Ahmadis held prominent posts in government positions; in the Indo-Pakistani War of 1947–1948

The Indo-Pakistani War of 1947–1948, or the First Kashmir War, was a war fought between India and Pakistan over the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir from 1947 to 1948. It was the first of four Indo-Pakistani wars that was fought between t ...

, in which Pakistan tried to invade and capture the state of Jammu and Kashmir Jammu and Kashmir may refer to:

* Kashmir, the northernmost geographical region of the Indian subcontinent

* Jammu and Kashmir (union territory), a region administered by India as a union territory

* Jammu and Kashmir (state), a region administered ...

, the Ahmadiyya Muslim Jama'at created the Furqan Force

The Furqan Force or Furqan Battalion was a uniformed Battalion force of volunteers of the minority Ahmadiyya Muslim Community in the Dominion of Pakistan. Formed in June 1948 at the direction of Head of the Worldwide Ahmadiyya Muslim Community, ...

to fight Indian troops.

In the first decade after Pakistan gained independence after the partition of India, "Pakistan considered its history to be a part of larger India's, a common history, a joint history, and in fact Indian textbooks were in use in the syllabus in Pakistan." The government under Ayub Khan

Ayub Khan is a compound masculine name; Ayub is the Arabic version of the name of the Biblical figure Job, while Khan or Khaan is taken from the title used first by the Mongol rulers and then, in particular, their Islamic and Persian-influenced s ...

, however, wished to rewrite the history of Pakistan to exclude any reference India and tasked the historians within Pakistan to manufacture a nationalist narrative of a "separate" history that erased the country's Indian past. Elizabeth A. Cole of the George Mason University Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter School for Peace and Conflict Resolution noted that Pakistani textbooks eliminate the country's Hindu and Buddhist past, while referring to Muslims as a monolithic entity and focusing solely on the advent of Islam in the Indian subcontinent

The Indian subcontinent is a list of the physiographic regions of the world, physiographical region in United Nations geoscheme for Asia#Southern Asia, Southern Asia. It is situated on the Indian Plate, projecting southwards into the Indian O ...

. During the rule of General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq

General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq HI, GCSJ, ร.ม.ภ, (Urdu: ; 12 August 1924 – 17 August 1988) was a Pakistani four-star general and politician who became the sixth President of Pakistan following a coup and declaration of martial law in ...

a "program of Islamization

Islamization, Islamicization, or Islamification ( ar, أسلمة, translit=aslamāh), refers to the process through which a society shifts towards the religion of Islam and becomes largely Muslim. Societal Islamization has historically occur ...

" of the country including the textbooks was started. General Zia's 1979 education policy stated that " hehighest priority would be given to the revision of the curricula with a view to reorganizing the entire content around Islamic thought and giving education an ideological orientation so that Islamic ideology permeates the thinking of the younger generation and helps them with the necessary conviction and ability to refashion society according to Islamic tenets". According to Pakistan Studies curriculum

Pakistan studies curriculum (Urdu: ') is the name of a curriculum of academic research and study that encompasses the culture, demographics, geography, history, International Relations and politics of Pakistan. The subject is widely research ...

, Muhammad bin Qasim

Muḥammad ibn al-Qāsim al-Thaqāfī ( ar, محمد بن القاسم الثقفي; –) was an Arab military commander in service of the Umayyad Caliphate who led the Muslim conquest of Sindh (part of modern Pakistan), inaugurating the Umayya ...

is often referred to as the first Pakistani despite having been alive several centuries before its creation through the partition of India in 1947. Muhammad Ali Jinnah also acclaimed the Pakistan movement

The Pakistan Movement ( ur, , translit=Teḥrīk-e-Pākistān) was a political movement in the first half of the 20th century that aimed for the creation of Pakistan from the Muslim-majority areas of British India. It was connected to the pe ...

to have started when the first Muslim put a foot in the Gateway of Islam

Sindh (; ; ur, , ; historically romanized as Sind) is one of the four provinces of Pakistan. Located in the southeastern region of the country, Sindh is the third-largest province of Pakistan by land area and the second-largest province ...

and that Bin Qasim is actually the founder of Pakistan.

Pakistan as inheritor state to Islamic political powers in medieval India

Some Pakistani nationalists state that Pakistan is the successor state ofIslam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic Monotheism#Islam, monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God in Islam, God (or ...

ic empires and kingdoms that ruled medieval India

Medieval India refers to a long period of Post-classical history of the Indian subcontinent between the "ancient period" and "modern period". It is usually regarded as running approximately from the breakup of the Gupta Empire in the 6th cent ...

for almost a combined period of one millennium, the empires and kingdoms in order are the Abbasid Caliphate

The Abbasid Caliphate ( or ; ar, الْخِلَافَةُ الْعَبَّاسِيَّة, ') was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abdul-Muttalib ...

, Ghaznavid Empire

The Ghaznavid dynasty ( fa, غزنویان ''Ġaznaviyān'') was a culturally Persianate society, Persianate, Sunni Islam, Sunni Muslim dynasty of Turkic peoples, Turkic ''mamluk'' origin, ruling, at its greatest extent, large parts of Persia, ...

, Ghorid Kingdom, Delhi Sultanate

The Delhi Sultanate was an Islamic empire based in Delhi that stretched over large parts of the Indian subcontinent for 320 years (1206–1526).

, Deccan sultanates

The Deccan sultanates were five Islamic late-medieval Indian kingdoms—on the Deccan Plateau between the Krishna River and the Vindhya Range—that were ruled by Muslim dynasties: namely Ahmadnagar, Berar, Bidar, Bijapur, and Golconda. Th ...

and Mughal Empire

The Mughal Empire was an early-modern empire that controlled much of South Asia between the 16th and 19th centuries. Quote: "Although the first two Timurid emperors and many of their noblemen were recent migrants to the subcontinent, the d ...

. This history of Muslim rule in the subcontinent composes possibly the largest segment of Pakistani nationalism.

To this end, many Pakistani nationalists claim monuments like the Taj Mahal

The Taj Mahal (; ) is an Islamic ivory-white marble mausoleum on the right bank of the river Yamuna in the Indian city of Agra. It was commissioned in 1631 by the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan () to house the tomb of his favourite wife, Mu ...

, located in Agra

Agra (, ) is a city on the banks of the Yamuna river in the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh, about south-east of the national capital New Delhi and 330 km west of the state capital Lucknow. With a population of roughly 1.6 million, Agra is ...

, which was built by Ustad Ahmad Lahori

Ustad Ahmad Lahori ( fa, ) was an architect from the South Asia-based Mughal Empire, who is said to have been the chief architect of the Taj Mahal in Agra, built between 1632 and 1648 during the rule of the Emperor Shah Jahan. Its architecture ...

, as being Pakistani and part of Pakistan's history. The Red Fort

The Red Fort or Lal Qila () is a historic fort in Old Delhi, Delhi in India that served as the main residence of the Mughal Emperors. Emperor Shah Jahan commissioned construction of the Red Fort on 12 May 1638, when he decided to shift hi ...

, and the Jama Masjid, Delhi

The Masjid-i-Jehan-Numa (), commonly known as the Jama Masjid of Delhi, is one of the largest mosques in India.

It was built by the Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan between 1650 and 1656, and inaugurated by its first Imam, Syed Abdul Ghafoor Shah Buk ...

are also claimed by Pakistani nationalists as belonging to Pakistanis.

Syed Ahmed Khan and the Indian Rebellion of 1857

See also: ''Syed Ahmed Khan

Sir Syed Ahmad Khan KCSI (17 October 1817 – 27 March 1898; also Sayyid Ahmad Khan) was an Indian Muslim reformer, philosopher, and educationist in nineteenth-century British India. Though initially espousing Hindu-Muslim unity, he ...

, Indian rebellion of 1857

The Indian Rebellion of 1857 was a major uprising in India in 1857–58 against the rule of the British East India Company, which functioned as a sovereign power on behalf of the British Crown. The rebellion began on 10 May 1857 in the fo ...

''

Syed Ahmed Khan

Sir Syed Ahmad Khan KCSI (17 October 1817 – 27 March 1898; also Sayyid Ahmad Khan) was an Indian Muslim reformer, philosopher, and educationist in nineteenth-century British India. Though initially espousing Hindu-Muslim unity, he ...

, the grandson of the Mughal Vizier, Dabir-ud-Daula, believed that Muslims and Hindus belonged to two separate nations. He promoted Western-style education in Muslim society, seeking to uplift Muslims

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abraha ...

economically and politically in British India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance on the Indian subcontinent. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one ...

. He founded the Aligarh Muslim University

Aligarh Muslim University (abbreviated as AMU) is a Public University, public Central University (India), central university in Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh, India, which was originally established by Sir Syed Ahmad Khan as the Muhammadan Anglo-Orie ...

, then called the ''Anglo-Oriental College''.

In 1835 Lord Macaulay

Thomas Babington Macaulay, 1st Baron Macaulay, (; 25 October 1800 – 28 December 1859) was a British historian and Whig politician, who served as the Secretary at War between 1839 and 1841, and as the Paymaster-General between 1846 and 1 ...

's minute recommending that Western rather than Oriental learning predominate in the East India Company's education policy had led to numerous changes. In place of Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic languages, Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C ...

and Persian

Persian may refer to:

* People and things from Iran, historically called ''Persia'' in the English language

** Persians, the majority ethnic group in Iran, not to be conflated with the Iranic peoples

** Persian language, an Iranian language of the ...

, the Western languages, history and philosophy were taught at state-funded schools and universities whilst religious education was barred. English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

became not only the medium of instruction but also the official language in 1835 in place of Persian, disadvantaging those who had built their careers around the latter language. Traditional Islamic studies were no longer supported by the state, and some ''madrasahs'' lost their ''waqf'' or endowment. The Indian rebellion of 1857

The Indian Rebellion of 1857 was a major uprising in India in 1857–58 against the rule of the British East India Company, which functioned as a sovereign power on behalf of the British Crown. The rebellion began on 10 May 1857 in the fo ...

is held by nationalists to have ended in disaster for the Muslims, as Bahadur Shah Zafar

Bahadur Shah II, usually referred to by his poetic title Bahadur Shah ''Zafar'' (; ''Zafar'' Victory) was born Mirza Abu Zafar Siraj-ud-din Muhammad (24 October 1775 – 7 November 1862) and was the twentieth and last Mughal Emperor as well a ...

, the last Mughal, was deposed. Power over the subcontinent was passed from the East India Company to the British Crown. The removal of the last symbol of continuity with the Mughal period spawned a negative attitude amongst some Muslims towards everything modern and western, and a disinclination to make use of the opportunities available under the new regime. As Muslims were generally agriculturists and soldiers, while Hindus were increasingly seen as successful financiers and businessmen, the historian Spear noted that to the Muslim "an industrialized India meant a Hindu India".

Seeing this atmosphere of despair and despondency, Syed launched his attempts to revive the spirit of progress within the Muslim community of India. He was convinced that the Muslims, in their attempt to regenerate themselves, had failed to realise that mankind had entered a very important phase of its existence, i.e., an era of science and learning. He knew that the realisation of that was the source of progress and prosperity for the British. Therefore, modern education became the pivot of his movement for regeneration of the Indian Muslims. He tried to transform the Muslim outlook from a mediaeval one to a modern one. Syed's first and foremost objective was to acquaint the British with the Indian mind; his next goal was to open the minds of his countrymen to European literature, science and technology. Therefore, in order to attain these goals, Syed launched the Aligarh Movement, of which Aligarh

Aligarh (; formerly known as Allygarh, and Kol) is a city in the state of Uttar Pradesh in India. It is the administrative headquarters of Aligarh district, and lies northwest of state capital Lucknow and approximately southeast of the capita ...

was the center. He had two immediate objectives in mind: to remove the state of misunderstanding and tension between the Muslims and the new British government, and to induce them to go after the opportunities available under the new regime without deviating in any way from the fundamentals of their faith.

Syed Ahmed Khan converted the existing cultural and religious entity among Indian Muslims into a separatist political force, throwing a Western cloak of nationalism over the Islamic concept of culture. The distinct sense of value, culture and tradition among Indian Muslims, which originated from the nature of Islamization of the Indian populace during the Muslim conquests in the Indian subcontinent

The Muslim conquests in the Indian subcontinent mainly took place from the 13th to 17th centuries. Earlier Muslim conquests include the invasions into what is now modern-day Pakistan and the Umayyad campaigns in India in eighth century and res ...

, was used for a separatist identity leading to the Pakistan Movement.

Independence of Pakistan

In theIndian rebellion of 1857

The Indian Rebellion of 1857 was a major uprising in India in 1857–58 against the rule of the British East India Company, which functioned as a sovereign power on behalf of the British Crown. The rebellion began on 10 May 1857 in the fo ...

, both Hindu and Muslims fought the forces allied with the British Empire in different parts of British India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance on the Indian subcontinent. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one ...

. The war's spark arose because the British attacked the "Beastly customs of Indian

Indian or Indians may refer to:

Peoples South Asia

* Indian people, people of Indian nationality, or people who have an Indian ancestor

** Non-resident Indian, a citizen of India who has temporarily emigrated to another country

* South Asia ...

s" by forcing the Indian ''sepoy

''Sepoy'' () was the Persian-derived designation originally given to a professional Indian infantryman, traditionally armed with a musket, in the armies of the Mughal Empire.

In the 18th century, the French East India Company and its oth ...

s'' to handle Enfield P-53 gun cartridge

Cartridge may refer to:

Objects

* Cartridge (firearms), a type of modern ammunition

* ROM cartridge, a removable component in an electronic device

* Cartridge (respirator), a type of filter used in respirators

Other uses

* Cartridge (surname) Ca ...

s greased with lard

Lard is a semi-solid white fat product obtained by rendering the fatty tissue of a pig.Lard

entry in the o ...

taken from slaughtered pigs and entry in the o ...

tallow

Tallow is a rendering (industrial), rendered form of beef or mutton fat, primarily made up of triglycerides.

In industry, tallow is not strictly defined as beef or mutton fat. In this context, tallow is animal fat that conforms to certain techn ...

taken from slaughtered cows. The cartridges had to bitten open to use the gunpowder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, carbon (in the form of charcoal) and potassium nitrate (saltpeter). ...

, effectively meaning that sepoys would have to bite the lard and tallow. This was a manifestation of the insenstivity that the British exhibited to Muslim and Hindu religious traditions, such as the rejection of pork consumption in Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic Monotheism#Islam, monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God in Islam, God (or ...

and the rejection of slaughter of cow in Hinduism

Hinduism () is an Indian religion or '' dharma'', a religious and universal order or way of life by which followers abide. As a religion, it is the world's third-largest, with over 1.2–1.35 billion followers, or 15–16% of the global p ...

. There were also some kingdoms and peoples who supported the British. This event laid the foundation not only for a nationwide expression, but also future nationalism and conflict on religious and ethnic terms.

The desire among some for a new state for the Indian Muslims, or ''Azadi'' was born with Kernal Sher Khan, who looked to Muslim history and heritage, and condemned the fact Muslims were ruled by the British Empire and not by Muslim leaders. The idea of complete independence did not catch on until after World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, when the British government reduced civil liberties with the Rowlatt Acts of 1919. When General Reginal Dyer ordered the Jallianwala Bagh Massacre

The Jallianwala Bagh massacre, also known as the Amritsar massacre, took place on 13 April 1919. A large peaceful crowd had gathered at the Jallianwala Bagh in Amritsar, Punjab, to protest against the Rowlatt Act and arrest of pro-independence ...

in Amritsar

Amritsar (), historically also known as Rāmdāspur and colloquially as ''Ambarsar'', is the second largest city in the Indian state of Punjab, after Ludhiana. It is a major cultural, transportation and economic centre, located in the Majha r ...

, Punjab

Punjab (; Punjabi: پنجاب ; ਪੰਜਾਬ ; ; also romanised as ''Panjāb'' or ''Panj-Āb'') is a geopolitical, cultural, and historical region in South Asia, specifically in the northern part of the Indian subcontinent, comprising ...

which took place in the same year, the Muslim public was outraged and most of the Muslim political leaders turned against the British government. Pakistan was finally actualized through the partition of India

The Partition of British India in 1947 was the Partition (politics), change of political borders and the division of other assets that accompanied the dissolution of the British Raj in South Asia and the creation of two independent dominions: ...

in 1947 on the basis of Two Nation Theory

The two-nation theory is an ideology of religious nationalism that influenced the decolonization, decolonisation of the British Raj in South Asia. According to this ideology, Islam in the Indian subcontinent, Indian Muslims and Hinduism in In ...

. Today, Pakistan is divided into 4 provinces. The last census recorded the 1981 population at 84.3 million, nearly double the 1961 figure of 42.9 million. By 1983, the population had tripled to nearly 93 million, making Pakistan the world's 9th most populous country, although in area it ranked 34th.

Pakistani nationalist symbols

Because of the country's identity with Islam, mosques like

Because of the country's identity with Islam, mosques like Badshahi Mosque

The Badshahi Mosque (Urdu, Punjabi: ; literally ''The Royal Mosque'') is a Mughal-era congregational mosque in Lahore, capital of the Pakistani province of Punjab. The mosque is located west of Lahore Fort along the outskirts of the Walled C ...

and Faisal Mosque

The Faisal Mosque ( ur, , faisal masjid) is the national mosque of Pakistan, located in capital Islamabad. It is the fifth-largest mosque in the world and the largest within South Asia, located on the foothills of Margalla Hills in Pakistan's ...

are also used as national symbols either to represent "glorious past" or modernistic future. Pakistan has many shrines, sights, sounds and symbols that have significance to Pakistani nationalists. These include the Shrines of Political leaders of pre-independence and post-independence Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 24 ...

, Shrines of Religious leaders and Saint

In religious belief, a saint is a person who is recognized as having an exceptional degree of Q-D-Š, holiness, likeness, or closeness to God. However, the use of the term ''saint'' depends on the context and Christian denomination, denominat ...

s, The Shrines of Imperial leaders of various Islamic Empires

This article includes a list of successive Islamic states and Muslim dynasties beginning with the time of the Islamic prophet Muhammad (570–632 CE) and the early Muslim conquests that spread Islam outside of the Arabian Peninsula, and continui ...

and Dynasties, as well as national symbols of Pakistan. Some of these shrines, sights and symbols have become a places of Pilgrimage

A pilgrimage is a journey, often into an unknown or foreign place, where a person goes in search of new or expanded meaning about their self, others, nature, or a higher good, through the experience. It can lead to a personal transformation, aft ...

for Pakistani ultra-nationalism

Ultranationalism or extreme nationalism is an extreme form of nationalism in which a country asserts or maintains detrimental hegemony, supremacy, or other forms of control over other nations (usually through violent coercion) to pursue its s ...

and militarism, as well as for obviously religious purposes.

The older ten rupee notes of the Pakistani rupee

The Pakistani rupee ( ur, / ALA-LC: ; sign: Re (singular) and Rs (plural); ISO code: PKR) is the official currency of Pakistan since 1948. The coins and notes are issued and controlled by the central bank, namely State Bank of Pakistan.

In ...

included background images of the remains of Mohenjo-daro

Mohenjo-daro (; sd, موئن جو دڙو'', ''meaning 'Mound of the Dead Men';Harappa

Harappa (; Urdu/ pnb, ) is an archaeological site in Punjab, Pakistan, about west of Sahiwal. The Bronze Age Harappan civilisation, now more often called the Indus Valley Civilisation, is named after the site, which takes its name from a mode ...

. In the 1960s, the imagery of Gandhara

Gandhāra is the name of an ancient region located in the northwestern region of the Indian subcontinent, more precisely in present-day north-west Pakistan and parts of south-east Afghanistan. The region centered around the Peshawar Vall ...

n and Greco-Buddhist

Greco-Buddhism, or Graeco-Buddhism, is the cultural syncretism between Hellenistic culture and Buddhism, which developed between the fourth century BC and the fifth century AD in Gandhara, in present-day north-western Pakistan and parts of nort ...

artefacts were unearthed in Pakistan, and some Pakistani nationalists "creatively imagined" an ancient civilisation which differentiated the provinces now lying in Pakistan from the rest of the Indian subcontinent, which is not accepted by mainstream historians; they tried to emphasize its contacts with the West and framed Gandharan Buddhism as antithetical to 'Brahmin' (Hindu) influence.

Nationalism and politics

The political identity of thePakistani Armed Forces

The Pakistan Armed Forces (; ) are the Military, military forces of Pakistan. It is the List of countries by number of military and paramilitary personnel, world's sixth-largest military measured by Active duty, active military personnel and con ...

, Pakistan's largest institution and one which controlled the government for over half the history of modern-day Pakistan and still does, is reliant on the connection to Pakistan's Imperial past. The Pakistan Muslim League's fortunes up till the 1970s were propelled by its legacy as the flagship of Pakistan's Independence Movement, and the core platform of the party today evokes that past, considering itself to be the guardian of Pakistan's freedom, democracy and unity as well as religion. Other parties have arisen, such as Pakistan Peoples Party

The Pakistan People's Party ( ur, , ; PPP) is a centre-left, social-democratic political party in Pakistan. It is currently the third largest party in the National Assembly and second largest in the Senate of Pakistan. The party was founded ...

, once advocating a leftist program and now more centrist. Nationally, the ruling Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) is weak. In contrast, the Muttahida Majlis-e-Amal

The Muttahida Majlis–e–Amal (MMA; Urdu: , "United Council of Action") is a political alliance consisting of conservative, Islamist, religious, and far-right parties of Pakistan. Naeem Siddiqui (the founder of Tehreek e Islami) proposed suc ...

employs a more aggressively theocratic nationalistic expression. The MMA seeks to defend the culture and heritage of Pakistan and the majority of its people, the Muslim population. It ties theocratic nationalism with the aggressive defence of Pakistan's borders and interests against archrival India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

, with the defence of the majority's right to be a majority.

Ethnic nationalist parties include the Awami National Party

The Awami National Party (ANP; ur, , ps, اولسي ملي ګوند; lit. ''People's National Party'') is a Pashtun nationalist, secular and leftist political party in Pakistan. The party was founded by Abdul Wali Khan in 1986 and its curr ...

, which is closely identified with the creation of a Pashtun

Pashtuns (, , ; ps, پښتانه, ), also known as Pakhtuns or Pathans, are an Iranian ethnic group who are native to the geographic region of Pashtunistan in the present-day countries of Afghanistan and Pakistan. They were historically re ...

-majority state in North-West Frontier Province

The North-West Frontier Province (NWFP; ps, شمال لویدیځ سرحدي ولایت, ) was a Chief Commissioner's Province of British India, established on 9 November 1901 from the north-western districts of the Punjab Province. Followin ...

and the Federally Administered Tribal Areas

, conventional_long_name = Federally Administered Tribal Areas

, nation = Pakistan

, subdivision = Autonomous territory

, image_flag = Flag of FATA.svg

, image_coat = File:Coat of arms ...

includes many Pashtun leaders in its organization. However, the Awami National Party

The Awami National Party (ANP; ur, , ps, اولسي ملي ګوند; lit. ''People's National Party'') is a Pashtun nationalist, secular and leftist political party in Pakistan. The party was founded by Abdul Wali Khan in 1986 and its curr ...

, At the last legislative

A legislature is an assembly with the authority to make laws for a political entity such as a country or city. They are often contrasted with the executive and judicial powers of government.

Laws enacted by legislatures are usually known as p ...

elections

An election is a formal group decision-making process by which a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative democracy has operate ...

, 20 October 2002, won a meagre 1.0% of the popular vote and no seats in the lower house of Parliament. In Balochistan

Balochistan ( ; bal, بلۏچستان; also romanised as Baluchistan and Baluchestan) is a historical region in Western and South Asia, located in the Iranian plateau's far southeast and bordering the Indian Plate and the Arabian Sea coastline. ...

, the Balochistan National Party uses the legacy of the independent Balochistan

Balochistan ( ; bal, بلۏچستان; also romanised as Baluchistan and Baluchestan) is a historical region in Western and South Asia, located in the Iranian plateau's far southeast and bordering the Indian Plate and the Arabian Sea coastline. ...

to stir up support, However at the legislative

A legislature is an assembly with the authority to make laws for a political entity such as a country or city. They are often contrasted with the executive and judicial powers of government.

Laws enacted by legislatures are usually known as p ...

elections

An election is a formal group decision-making process by which a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative democracy has operate ...

, 20 October 2002, the party won only 0.2% of the popular vote and 1 out of 272 elected members.

Almost every Pakistani state has a regional party devoted solely to the culture of the native people. Unlike the Awami National party and the Balochistan national party, these mostly cannot be called nationalist, as they use regionalism as a strategy to garner votes, building on the frustration of common people with official status and the centralization of government institutions in Pakistan. However, the recent elections as well as history have shown that such ethnic nationalist parties rarely win more than 1% of the popular vote, with the overwhelming majority of votes going to large and established political parties that pursue a national agenda as opposed to regionalism.

Nuclear power

guerrilla war

Guerrilla warfare is a form of irregular warfare in which small groups of combatants, such as paramilitary personnel, armed civilians, or irregulars, use military tactics including ambushes, sabotage, raids, petty warfare, hit-and-run tactic ...

in far Eastern Pakistan

East Pakistan was a Pakistani province established in 1955 by the One Unit Policy, renaming the province as such from East Bengal, which, in modern times, is split between India and Bangladesh. Its land borders were with India and Myanmar, wit ...

, followed by India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

's successful intervention led to the secession

Secession is the withdrawal of a group from a larger entity, especially a political entity, but also from any organization, union or military alliance. Some of the most famous and significant secessions have been: the former Soviet republics le ...

of Eastern contingent as Bangladesh

Bangladesh (}, ), officially the People's Republic of Bangladesh, is a country in South Asia. It is the eighth-most populous country in the world, with a population exceeding 165 million people in an area of . Bangladesh is among the mos ...

. The outcomes of the war played a crucial role in the civil society. In January 1972, a clandestine crash programme and a spin-off to literary

Literature is any collection of Writing, written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially prose fiction, drama, and poetry. In recent centuries, the definition has expanded to ...

and the scientific revolution

The Scientific Revolution was a series of events that marked the emergence of modern science during the early modern period, when developments in mathematics, physics, astronomy, biology (including human anatomy) and chemistry transfo ...

as response to that crash programme led Pakistan becoming the nuclear power.

First public tests were experimented out in 1998 (code names:Chagai-I

Chagai-I is the code name of five simultaneous underground nuclear tests conducted by Pakistan at 15:15 hrs PKT on 28 May 1998. The tests were performed at Ras Koh Hills in the Chagai District of Balochistan Province.

Chagai-I was Pakistan's ...

and Chagai-II

Chagai-II is the codename assigned to the second atomic test conducted by Pakistan, carried out on 30 May 1998 in the Kharan Desert in Balochistan Province of Pakistan. ''Chagai-II'' took place two days after Pakistan's first successful test, ' ...

) in a direct response to India's nuclear explosions

An explosion is a rapid expansion in volume associated with an extreme outward release of energy, usually with the generation of high temperatures and release of high-pressure gases. Supersonic explosions created by high explosives are known ...

in the same year; thus Pakistan became the 7th nation in the world to have successfully developed the programme. It is postulated that Pakistan's crash programme arose in 1970 and mass acceleration

In mechanics, acceleration is the rate of change of the velocity of an object with respect to time. Accelerations are vector quantities (in that they have magnitude and direction). The orientation of an object's acceleration is given by the ...

took place following the India's nuclear test

Nuclear weapons tests are experiments carried out to determine nuclear weapons' effectiveness, yield, and explosive capability. Testing nuclear weapons offers practical information about how the weapons function, how detonations are affected by ...

in 1974. It also resulted in Pakistan pursuing similar ambitions, resulting in the May 1998 testings of five nuclear devices by India and six as a response by Pakistan, opening a new era in their rivalry. Pakistan, along with Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

and India, is three of the original states that have restrained itself from being party of the NPT and CTBT

The Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT) is a multilateral treaty to ban nuclear weapons test explosions and any other nuclear explosions, for both civilian and military purposes, in all environments. It was adopted by the United Nation ...

which it considers an encroachment on its right to defend itself. To date, Pakistan is the only Muslim nuclear state

Eight sovereign states have publicly announced successful detonation of nuclear weapons. Five are considered to be nuclear-weapon states (NWS) under the terms of the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT). In order of acquisi ...

.

See also

*Muslim nationalism in South Asia

From a historical perspective, Professor Ishtiaq Ahmed of the University of Stockholm and Professor Shamsul Islam of the University of Delhi classified the Muslims of South Asia into two categories during the era of the Indian independence moveme ...

* Dil Dil Pakistan

Dil Dil Pakistan ( ur, ) is the most popular patriotic Pakistani song, sung by Junaid Jamshed. It was released in 1987 by the pop band Vital Signs. The song was featured in the band's debut album, ''Vital Signs 1'', in 1987. Dil Dil Pakistan is ...

* Pakistan Zindabad

Pakistan Zindabad ( ur, , ) is a patriotic slogan used by Pakistanis in displays of Pakistani nationalism. The phrase became popular among the Muslims of British India after the 1933 publication of the "Pakistan Declaration" by Choudhry Rahmat ...

* Politics of Pakistan

The Politics of Pakistan () takes place within the framework established by the constitution. The country is a federal parliamentary republic in which provincial governments enjoy a high degree of autonomy and residuary powers. Executive ...

References

Further reading

* * * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Pakistani Nationalism Political movements in Pakistan Islamic nationalism