National Women's Rights Convention on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The National Women's Rights Convention was an annual series of meetings that increased the visibility of the early

In April 1850, Ohio women held a convention to begin petitioning their constitutional convention for women's equal legal and political rights.

In April 1850, Ohio women held a convention to begin petitioning their constitutional convention for women's equal legal and political rights.

The meeting was called to order by Sarah H. Earle, a leader in Worcester's antislavery organizations. Paulina Wright Davis was chosen to preside and in her opening address called for "the emancipation of a class, the redemption of half the world, and a conforming re-organization of all social, political, and industrial interests and institutions".

The first resolution from the business committee defined the movement's objective: "to secure for

The meeting was called to order by Sarah H. Earle, a leader in Worcester's antislavery organizations. Paulina Wright Davis was chosen to preside and in her opening address called for "the emancipation of a class, the redemption of half the world, and a conforming re-organization of all social, political, and industrial interests and institutions".

The first resolution from the business committee defined the movement's objective: "to secure for

''More Women's Rights Conventions''.

Retrieved on April 1, 2009. Wendell Phillips made a speech which was so persuasive that it would be sold as a tract until 1920:

Wendell Phillips made a speech which was so persuasive that it would be sold as a tract until 1920:

''Ernestine Rose's speech at the Women's Rights Convention in Worcester, Massachusetts in October 15, 1851''

Retrieved on April 1, 2009.

For the third convention, the city hall in

For the third convention, the city hall in

Earlier in the year, a regional Women's Rights Convention in New York City had been interrupted by unruly men in the audience, with most of the speakers being unheard over shouts and hisses. Organizers of the fourth national convention were concerned that a repetition of that mob scene does not take place. In Cleveland, objections were raised regarding Bible interpretations, and orderly discussion proceeded.

Earlier in the year, a regional Women's Rights Convention in New York City had been interrupted by unruly men in the audience, with most of the speakers being unheard over shouts and hisses. Organizers of the fourth national convention were concerned that a repetition of that mob scene does not take place. In Cleveland, objections were raised regarding Bible interpretations, and orderly discussion proceeded.

At Sansom Street Hall in

At Sansom Street Hall in

''Ernestine Rose: A Troublesome Female''.

Retrieved on April 1, 2009. Rose spoke out to the gathering, saying "Our claims are based on that great and immutable truth, the rights of all humanity. For is woman not included in that phrase, 'all men are created ... equal'?. ... Tell us, ye men of the nation ... whether woman is not included in that great

At Smith & Nixon's Hall in

At Smith & Nixon's Hall in

At the Broadway Tabernacle in New York City on November 25–26, 1856, Lucy Stone served as president, and recounted for the crowd the recent progress in women's property rights laws passing in nine states, as well as a limited ability for widows in Kentucky to vote for school board members. She noted with satisfaction that the new Republican Party was interested in female participation during the 1856 elections. Lucretia Mott encouraged the assembly to use their new rights, saying, "Believe me, sisters, the time is come for you to avail yourselves of all the avenues that are opened to you."

A letter was read aloud from

At the Broadway Tabernacle in New York City on November 25–26, 1856, Lucy Stone served as president, and recounted for the crowd the recent progress in women's property rights laws passing in nine states, as well as a limited ability for widows in Kentucky to vote for school board members. She noted with satisfaction that the new Republican Party was interested in female participation during the 1856 elections. Lucretia Mott encouraged the assembly to use their new rights, saying, "Believe me, sisters, the time is come for you to avail yourselves of all the avenues that are opened to you."

A letter was read aloud from

Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Antoinette Brown Blackwell moved to add a resolution calling for legislation on marriage reform; they wanted laws that would give women the right to separate from or divorce a husband who had demonstrated drunkenness, insanity, desertion or cruelty. Wendell Phillips argued against the resolution, fracturing the executive committee on the matter. Susan B. Anthony also supported the measure, but it was defeated by vote after a heated debate.

Horace Greeley wrote in the ''Tribune'' that there were "One Thousand Persons Present, seven-eighths of them Women, and a fair Proportion Young and Good-looking". Greeley, a foe of marriage reform, continued against Stanton's proposed resolution with a jab at "easy Divorce", writing that the word 'Woman' should be replaced in the convention's title with "Wives Discontented".Stanton et al, 1881, p. 740.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Antoinette Brown Blackwell moved to add a resolution calling for legislation on marriage reform; they wanted laws that would give women the right to separate from or divorce a husband who had demonstrated drunkenness, insanity, desertion or cruelty. Wendell Phillips argued against the resolution, fracturing the executive committee on the matter. Susan B. Anthony also supported the measure, but it was defeated by vote after a heated debate.

Horace Greeley wrote in the ''Tribune'' that there were "One Thousand Persons Present, seven-eighths of them Women, and a fair Proportion Young and Good-looking". Greeley, a foe of marriage reform, continued against Stanton's proposed resolution with a jab at "easy Divorce", writing that the word 'Woman' should be replaced in the convention's title with "Wives Discontented".Stanton et al, 1881, p. 740.

''History of Woman Suffrage, Volume III''

covering 1876–1885. Copyright 1886. * Baker, Jean H.

''Sisters: The Lives of America's Suffragists.''

Hill and Wang, New York, 2005. * Baker, Jean H

''Votes for Women: The Struggle for Suffrage Revisited.''

Oxford University Press, 2002. * Blackwell, Alice Stone

''Lucy Stone: Pioneer of Woman's Rights.''

Charlottesville and London: University Press of Virginia, 2001. * Buhle, Mari Jo; Buhle, Paul

''The concise history of woman suffrage.''

University of Illinois, 1978. * Hays, Elinor Rice

''Morning Star: A Biography of Lucy Stone 1818–1893.''

Harcourt, Brace & World, 1961. * Lasser, Carol and Merrill, Marlene Deahl, editors

''Friends and Sisters: Letters between Lucy Stone and Antoinette Brown Blackwell, 1846–93''

University of Illinois Press, 1987. * Kerr, Andrea Moore

''Lucy Stone: Speaking Out for Equality.''

New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 1992. * Mani, Bonnie G

''Women, Power, and Political Change.''

Lexington Books, 2007. * McMillen, Sally Gregory

''Seneca Falls and the origins of the women's rights movement.''

Oxford University Press, 2008. * Million, Joelle

''Woman's Voice, Woman's Place: Lucy Stone and the Birth of the Women's Rights Movement.''

Praeger, 2003.

''Proceedings of the Eleventh National Woman's Rights Convention, Held at the Church of the Puritans, New York, May 10, 1866. Phonographic Report by H.M. Parkhurst''. New York: Robert J. Johnson, 1866.

''Proceedings of the Seventh National Woman's Rights Convention, Held in New York City at the Broadway Tabernacle, on Tuesday and Wednesday, Nov. 25 & 26, 1856''. New York: Edward O. Jenkins, 1856. *

''Proceedings of the Tenth National Woman's Rights Convention, Held at the Cooper Institute, New York City, May 10th and 11th, 1860''. Boston: Yerrinton and Garrison, 1860

''Proceedings of the Woman's Rights Convention, Held at Syracuse, September 8th, 9th, and 10th, 1852''. Syracuse: J. E. Masters, 1852.

''Proceedings of the Woman's Rights Convention, Held at Worcester, October 15th and 16th,1851''. New York; Fowlers and Wells, 1852. * Schenken, Suzanne O'Dea

''From Suffrage to the Senate.''

Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 1999. pp. 644–646. * Spender, Dale. (1982

''Women of Ideas and what Men Have Done to Them.''

Ark Paperbacks, Routledge & Kegan Paul, London, 1983, pp. 347–357. * Stanton, Elizabeth Cady; Anthony, Susan B.; Gage, Matilda Joslyn

''History of Woman Suffrage, Volume I''

covering 1848–1861. Copyright 1881. * Wheeler, Leslie. "Lucy Stone: Radical beginnings (1818–1893)" in Spender, Dale (ed.

''Feminist theorists: Three centuries of key women thinkers''

Pantheon 1983, pp. 124–136.

1850–1863 * Gutenberg Project

''History of Woman Suffrage, Volume I''

1881, by Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony and Matilda Joslyn Gage. * Worcester Women's History Project

related to 1850 and 1851 conventions {{Portal bar, Feminism History of New York (state) History of Massachusetts History of women's rights in the United States 1850 in American politics 1850 in women's history Women's suffrage advocacy groups in the United States Women in New York (state) Women in Massachusetts National Women’s Rights Convention (1850

women's rights

Women's rights are the rights and entitlements claimed for women and girls worldwide. They formed the basis for the women's rights movement in the 19th century and the feminist movements during the 20th and 21st centuries. In some countries, ...

movement in the United States. First held in 1850 in Worcester, Massachusetts

Worcester ( , ) is a city and county seat of Worcester County, Massachusetts, United States. Named after Worcester, England, the city's population was 206,518 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, making it the second-List of cities i ...

, the National Women's Rights Convention combined both female and male leadership and attracted a wide base of support including temperance advocates and abolitionists

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The Britis ...

. Speeches were given on the subjects of equal wages, expanded education and career opportunities, women's property rights Women's property rights are property and inheritance rights enjoyed by women as a category within a society.

Property rights are claims to property that are legally and socially recognized and enforceable by external legitimized authority. Broadly ...

, marriage reform, and temperance. Chief among the concerns discussed at the convention was the passage of laws that would give women the right to vote.

Background

Seneca Falls Convention

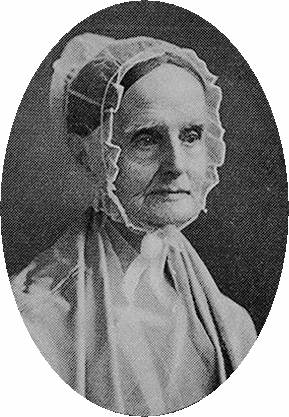

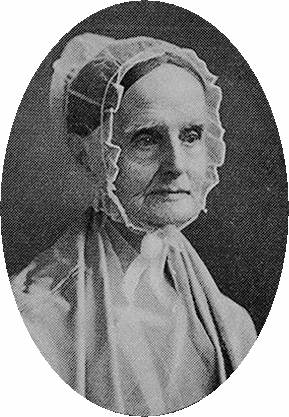

In 1840,Lucretia Mott

Lucretia Mott (''née'' Coffin; January 3, 1793 – November 11, 1880) was an American Quaker, abolitionist, women's rights activist, and social reformer. She had formed the idea of reforming the position of women in society when she was amongs ...

and Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Elizabeth Cady Stanton (November 12, 1815 – October 26, 1902) was an American writer and activist who was a leader of the women's rights movement in the U.S. during the mid- to late-19th century. She was the main force behind the 1848 Seneca ...

traveled with their husbands to London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

for the first World Anti-Slavery Convention

The World Anti-Slavery Convention met for the first time at Exeter Hall in London, on 12–23 June 1840. It was organised by the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society, largely on the initiative of the English Quaker Joseph Sturge. The exclu ...

, but they were not allowed to participate because they were women. Mott and Stanton became friends there and agreed to organize a convention to further the cause of women's rights. It was not until the summer of 1848 that Mott, Stanton, and three other women organized the Seneca Falls Convention

The Seneca Falls Convention was the first women's rights convention. It advertised itself as "a convention to discuss the social, civil, and religious condition and rights of woman".Wellman, 2004, p. 189 Held in the Wesleyan Methodist Church ...

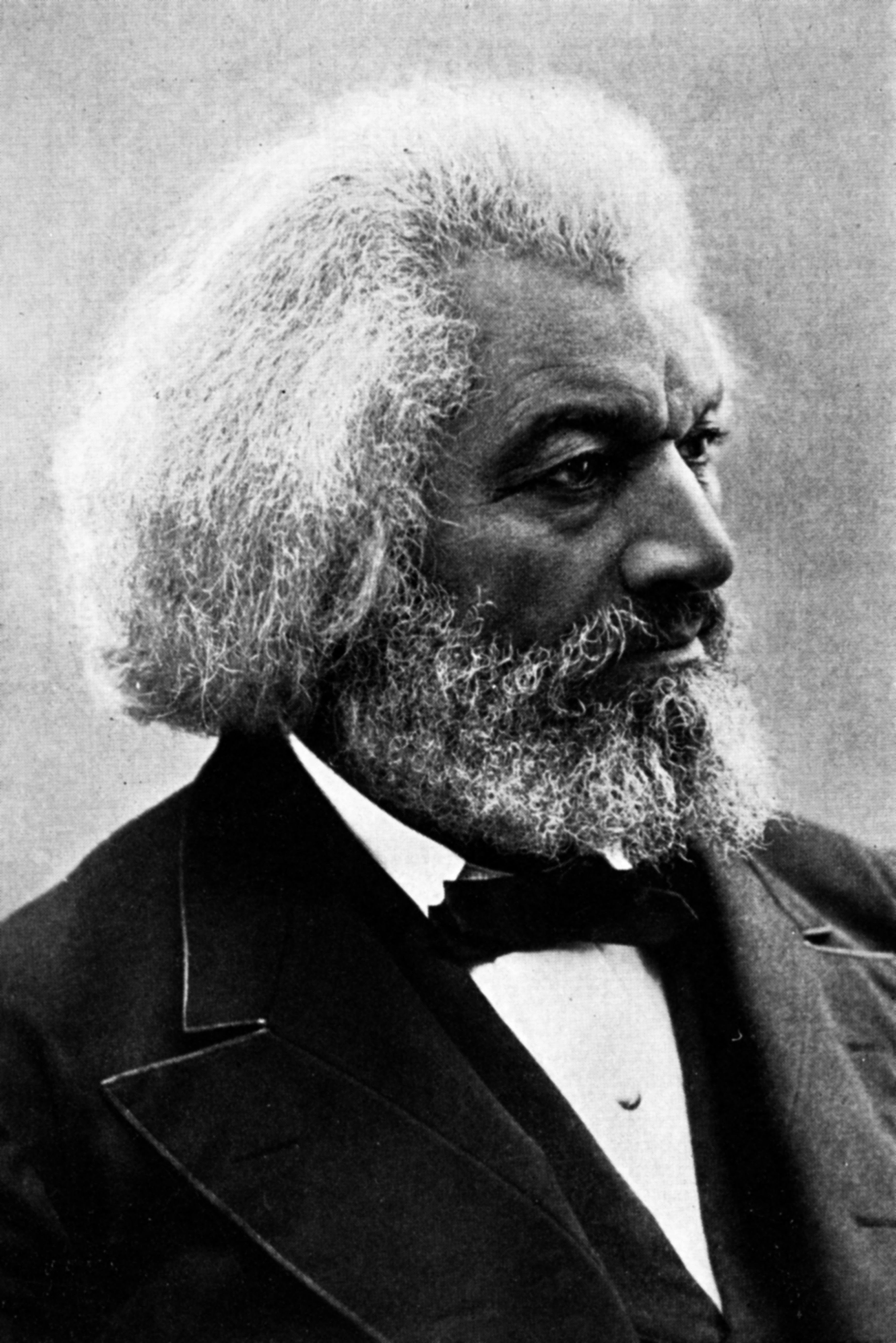

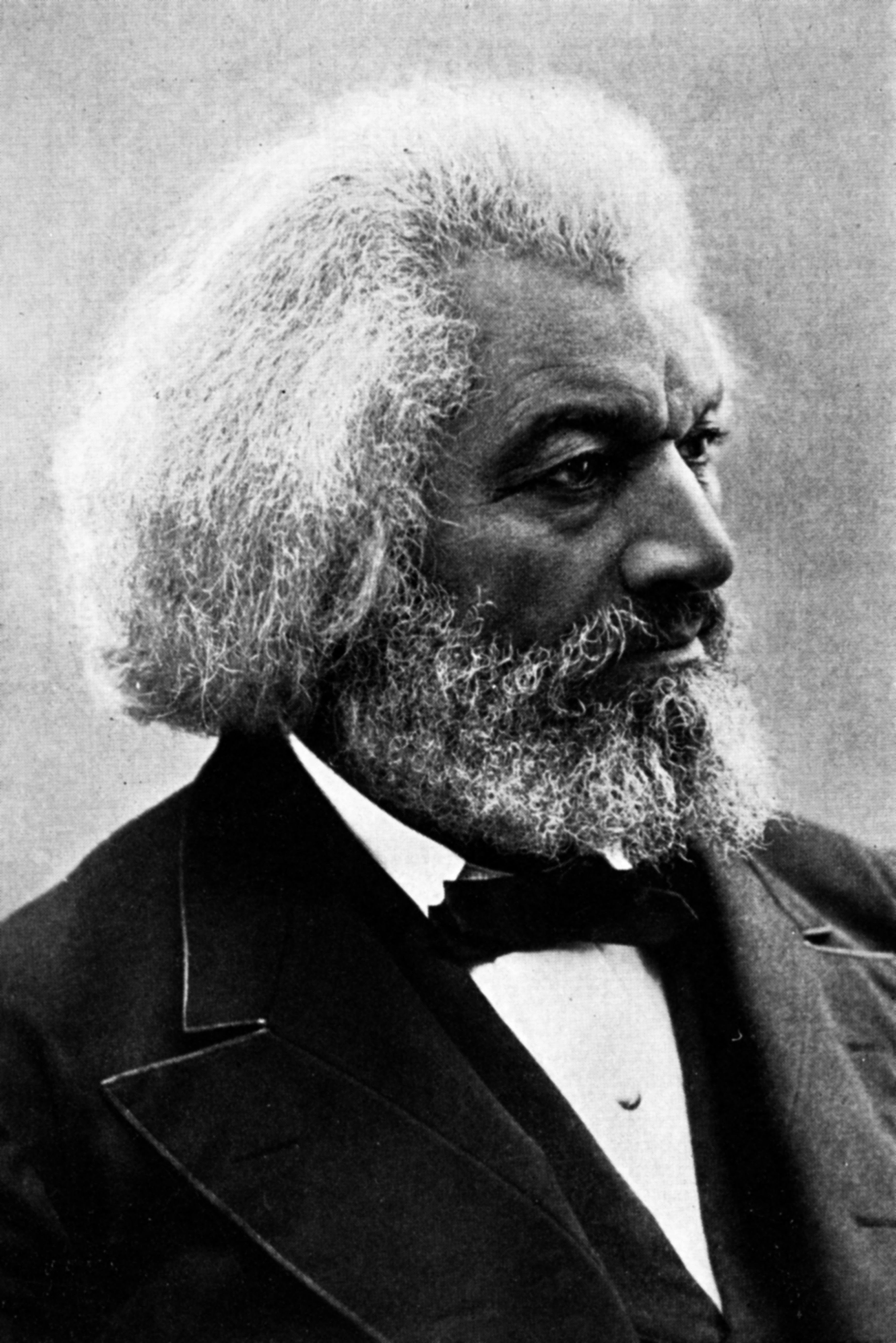

, the first women's rights convention. It was attended by some 300 people over two days, including about 40 men. The resolution on the subject of votes for women caused dissension until Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, February 1817 or 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. After escaping from slavery in Maryland, he became ...

took the platform with a passionate speech in favor of having a suffrage statement within the proposed Declaration of Sentiments

The Declaration of Sentiments, also known as the Declaration of Rights and Sentiments, is a document signed in 1848 by 68 women and 32 men—100 out of some 300 attendees at the first women's rights convention to be organized by women. Held in Sen ...

. One hundred of the attendees subsequently signed the Declaration. no

Other early women's rights conventions

Signers of the Declaration hoped for "a series of Conventions, embracing every part of the country" to follow their own meeting. Because of the fame and drawing power of Lucretia Mott, who would not be visiting theUpstate New York

Upstate New York is a geographic region consisting of the area of New York State that lies north and northwest of the New York City metropolitan area. Although the precise boundary is debated, Upstate New York excludes New York City and Long Is ...

area for much longer, some of the participants at Seneca Falls organized another regional meeting two weeks later, the Rochester Women's Rights Convention of 1848

The Rochester Women's Rights Convention of 1848 met on August 2, 1848 in Rochester, New York. Many of its organizers had participated in the Seneca Falls Convention, the first women's rights convention, two weeks earlier in Seneca Falls, a small ...

, featuring many of the same speakers. The first women's rights convention to be organized on a statewide basis was the Ohio Women's Convention at Salem in 1850 The Ohio Women's Convention at Salem in 1850 met on April 19–20, 1850 in Salem, Ohio, a center for reform activity. It was the third in a series of women's rights conventions that began with the Seneca Falls Convention of 1848. It was the first o ...

.

Planning

In April 1850, Ohio women held a convention to begin petitioning their constitutional convention for women's equal legal and political rights.

In April 1850, Ohio women held a convention to begin petitioning their constitutional convention for women's equal legal and political rights. Lucy Stone

Lucy Stone (August 13, 1818 – October 18, 1893) was an American orator, abolitionist and suffragist who was a vocal advocate for and organizer promoting rights for women. In 1847, Stone became the first woman from Massachusetts to earn a colle ...

, who had agitated for women's rights while a student at Ohio's Oberlin College

Oberlin College is a Private university, private Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college and conservatory of music in Oberlin, Ohio. It is the oldest Mixed-sex education, coeducational liberal arts college in the United S ...

and begun lecturing on women's rights after graduating in 1847, wrote to the Ohio organizers pledging Massachusetts to follow their lead.

At the end of the New England Anti-Slavery Convention on May 30, 1850, an announcement was made that a meeting would be held to consider whether to hold a woman's rights convention. That evening, Paulina Kellogg Wright Davis

Paulina Wright Davis ( Kellogg; August 7, 1813 – August 24, 1876) was an American abolitionist, suffragist, and educator. She was one of the founders of the New England Woman Suffrage Association.

Early life

Davis was born in Bloomfield, N ...

presided over a large meeting in Boston's Melodeon

Melodeon may refer to:

* Melodeon (accordion), a type of button accordion

*Melodeon (organ), a type of 19th-century reed organ

*Melodeon (Boston, Massachusetts), a concert hall in 19th-century Boston

* Melodeon Records, a U.S. record label in the ...

Hall, while Lucy Stone served as secretary. Stone, Henry C. Wright

Henry Clarke Wright (August 29, 1797 – August 16, 1870) was an American abolitionist, pacifist, anarchist and feminist, for over two decades a controversial figure.

Early life

Clarke was born in Sharon, Connecticut, to father Seth Wright, a ...

, William Lloyd Garrison

William Lloyd Garrison (December , 1805 – May 24, 1879) was a prominent American Christian, abolitionist, journalist, suffragist, and social reformer. He is best known for his widely read antislavery newspaper '' The Liberator'', which he found ...

, and Samuel Brooke spoke of the need for such a convention. Garrison, whose name had headed the first woman suffrage petition sent to the Massachusetts legislature the previous year, said, "I conceive that the first thing to be done by the women of this country is to demand their political enfranchisement. Among the 'self-evident truths' announced in the Declaration of Independence is this – 'All government derives its just power from the consent of the governed

In political philosophy, the phrase consent of the governed refers to the idea that a government's legitimacy and moral right to use state power is justified and lawful only when consented to by the people or society over which that political powe ...

.'" The meeting decided to call a convention and set Worcester, Massachusetts, as the place and October 16 and 17, 1850, as the date. It appointed Davis, Stone, Abby Kelley Foster

Abby Kelley Foster (January 15, 1811 – January 14, 1887) was an American abolitionist and radical social reformer active from the 1830s to 1870s. She became a fundraiser, lecturer and committee organizer for the influential American Anti-Sl ...

, Harriot Kezia Hunt

Harriot Kezia Hunt (November 9, 1805January 2, 1875) was an early female physician and women's rights activist. She spoke at the first National Women's Rights Conventions, held in 1850 in Worcester, Massachusetts.

Early life

Hunt was born in ...

, Eliza J. Kenney, Dora Taft, and Eliza H. Taft a committee of arrangements, with Davis and Stone as the committee of correspondence.

Davis and Stone asked William Elder, a retired Philadelphia physician, to draw up the convention callMillion, 2003, p. 105 while they set about securing signatures to it and lining up speakers. "We need all the women who are accustomed to speak in public – every stick of timber that is sound," Stone wrote to Antoinette Brown, a fellow Oberlin student who was preparing for the ministry. On Davis's list to contact was Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who sent her regrets along with a letter of support and a speech to be read in her name. Stanton wished to stay at home because she would be in the late stages of pregnancy.

After completing her part of the correspondence, Stone went to Illinois to visit a brother. Within days of her arrival, he died of cholera and Stone was left to settle his affairs and accompany his pregnant widow back east. Fearing she might not be able to return for three months, she wrote to Davis asking her to take charge of issuing the call. The call began appearing in September, with the convention date pushed back one week and Stone's name heading the list of eighty-nine signatories: thirty-three from Massachusetts, ten from Rhode Island, seventeen from New York, eighteen from Pennsylvania, one from Maryland, and nine from Ohio. While the call began circulating, Stone lay near death in a roadside inn. Having decided not to tarry in the disease-ridden Wabash Valley

The Wabash Valley is a region located in sections of both Illinois and Indiana. It is named for the Wabash River and, as the name is typically used, spans the middle to the middle-lower portion of the river's valley and is centered at Terre Haute ...

, she had begun a stagecoach trek back across Indiana with her sister-in-law, and within days contracted typhoid fever that kept her bed-ridden for three weeks. She arrived back in Massachusetts in October, just two weeks before the convention.

1850 in Worcester

The first National Women's Rights Convention met in Brinley Hall in Worcester, Massachusetts, on October 23–24, 1850. Some 900 people showed up for the first session, men forming the majority, with several newspapers reporting over a thousand attendees by the afternoon of the first day,McMillen, 2008. p. 108. and more turned away outside.Kerr, 1992, p. 59. Delegates came from eleven states, including one delegate from California – a state only a few weeks old. The meeting was called to order by Sarah H. Earle, a leader in Worcester's antislavery organizations. Paulina Wright Davis was chosen to preside and in her opening address called for "the emancipation of a class, the redemption of half the world, and a conforming re-organization of all social, political, and industrial interests and institutions".

The first resolution from the business committee defined the movement's objective: "to secure for

The meeting was called to order by Sarah H. Earle, a leader in Worcester's antislavery organizations. Paulina Wright Davis was chosen to preside and in her opening address called for "the emancipation of a class, the redemption of half the world, and a conforming re-organization of all social, political, and industrial interests and institutions".

The first resolution from the business committee defined the movement's objective: "to secure for oman

Oman ( ; ar, عُمَان ' ), officially the Sultanate of Oman ( ar, سلْطنةُ عُمان ), is an Arabian country located in southwestern Asia. It is situated on the southeastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula, and spans the mouth of t ...

political, legal, and social equality with man until her proper sphere is determined by what alone should determine it, her powers and capacities, strengthened and refined by an education in accordance with her nature". Another set of resolutions put forth women's claim for equal civil and political rights and demanded that the word "male" be stricken from every state constitution. Others addressed specific issues of property rights, access to education, and employment opportunities, while others defined the movement as an effort to secure the "natural and civil rights" of all women, including women held in slavery.

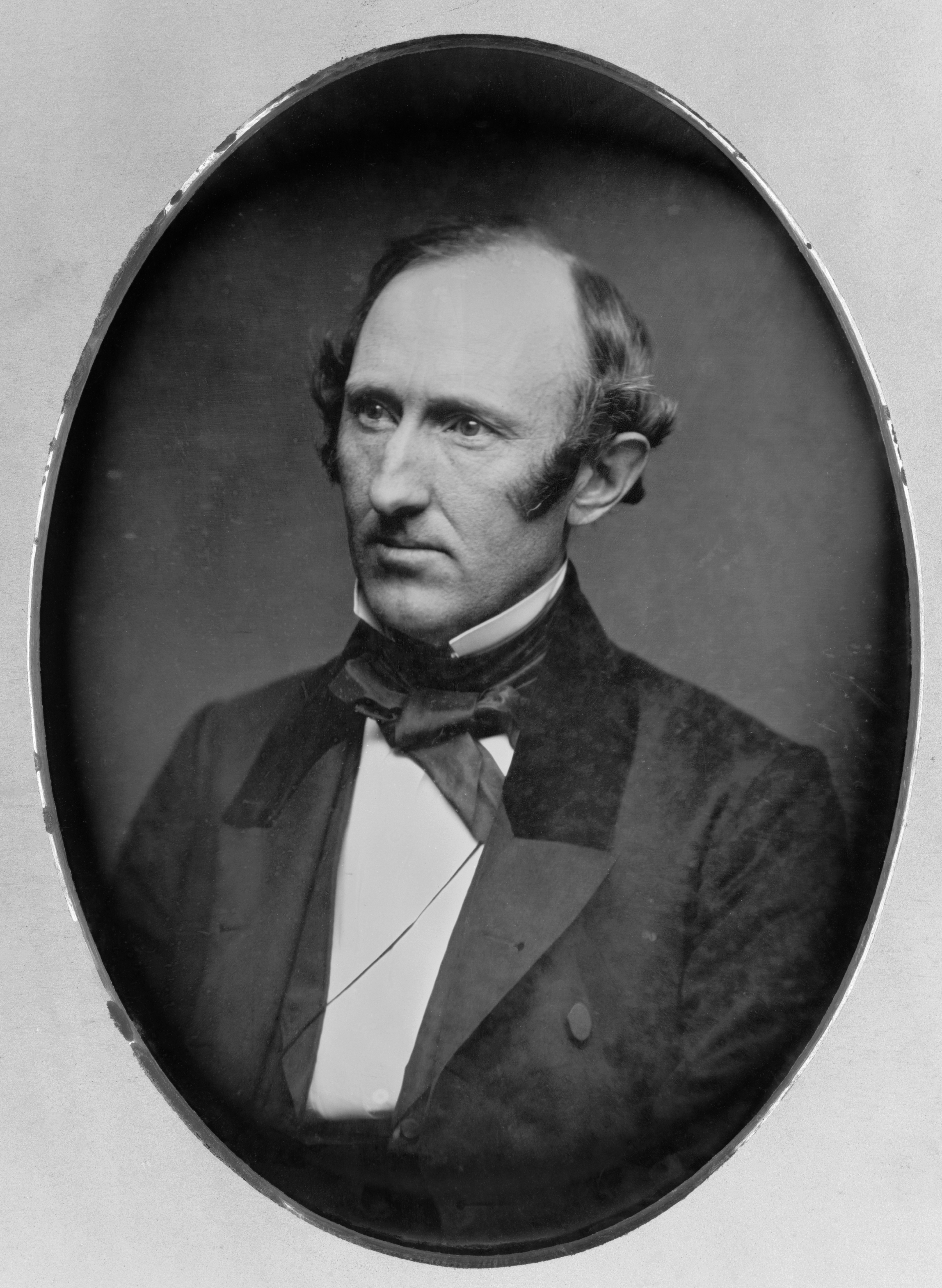

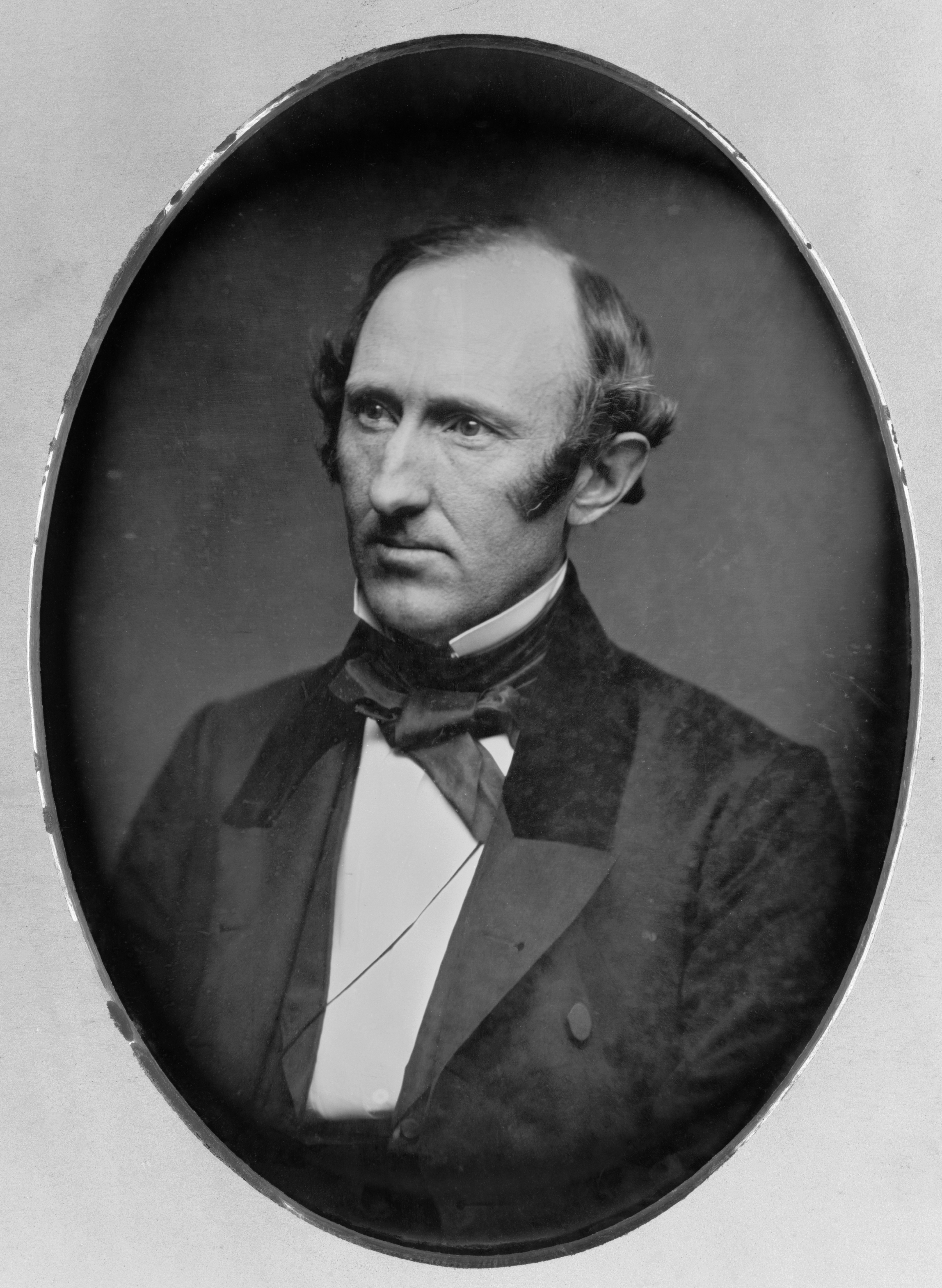

The convention considered how best to organize to promote their goals. Mindful of many members' opposition to organized societies, Wendell Phillips said there was no need for a formal association or founding document: annual conventions and a standing committee to arrange them was organization enough, and resolutions adopted at the conventions could serve as a declaration of principles. Reflecting its egalitarian principles, the business committee appointed a Central Committee of nine women and nine men. It also appointed committees on Education, Industrial Avocations, Civil and Political Functions, and Social Relations to gather and publish information useful for guiding public opinion toward establishing "Woman's co-equal sovereignty with Man".

Convention speakers included William Lloyd Garrison

William Lloyd Garrison (December , 1805 – May 24, 1879) was a prominent American Christian, abolitionist, journalist, suffragist, and social reformer. He is best known for his widely read antislavery newspaper '' The Liberator'', which he found ...

, William Henry Channing

William Henry Channing (May 25, 1810 – December 23, 1884) was an American Unitarian clergyman, writer and philosopher.

Biography

William Henry Channing was born in Boston, Massachusetts. Channing's father, Francis Dana Channing, died when he wa ...

, Wendell Phillips

Wendell Phillips (November 29, 1811 – February 2, 1884) was an American abolitionist, advocate for Native Americans, orator, and attorney.

According to George Lewis Ruffin, a Black attorney, Phillips was seen by many Blacks as "the one whi ...

, Harriot Kezia Hunt

Harriot Kezia Hunt (November 9, 1805January 2, 1875) was an early female physician and women's rights activist. She spoke at the first National Women's Rights Conventions, held in 1850 in Worcester, Massachusetts.

Early life

Hunt was born in ...

, Ernestine Rose

Ernestine Louise Rose (January 13, 1810 – August 4, 1892) was a suffragist, abolitionist, and freethinker who has been called the “first Jewish feminist.” Her career spanned from the 1830s to the 1870s, making her a contemporary to the more ...

, Antoinette Brown, Sojourner Truth

Sojourner Truth (; born Isabella Baumfree; November 26, 1883) was an American abolitionist of New York Dutch heritage and a women's rights activist. Truth was born into slavery in Swartekill, New York, but escaped with her infant daughter to f ...

, Stephen Symonds Foster

Stephen Symonds Foster (November 17, 1809 – September 13, 1881) was a radical American abolitionist known for his dramatic and aggressive style of public speaking, and for his stance against those in the church who failed to fight slavery. His ma ...

, Abby Kelley Foster

Abby Kelley Foster (January 15, 1811 – January 14, 1887) was an American abolitionist and radical social reformer active from the 1830s to 1870s. She became a fundraiser, lecturer and committee organizer for the influential American Anti-Sl ...

, Abby H. Price, Lucretia Mott

Lucretia Mott (''née'' Coffin; January 3, 1793 – November 11, 1880) was an American Quaker, abolitionist, women's rights activist, and social reformer. She had formed the idea of reforming the position of women in society when she was amongs ...

, and Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, February 1817 or 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. After escaping from slavery in Maryland, he became ...

. Stone served on the business committee and did not speak until the final evening. As an appointee to the committee on Civil and Political Functions, she urged the assemblage to petition their state legislatures for the right of suffrage, the right of married women to hold property, and as many other specific rights as they felt practical to seek in their respective states. Then she gave a brief speech, saying, "We want to be something more than the appendages of Society; we want that Woman should be the coequal and help-meet of Man in all the interest and perils and enjoyments of human life. We want that she should attain to the development of her nature and womanhood; we want that when she dies, it may not be written on her gravestone that she was the "relict

A relict is a surviving remnant of a natural phenomenon.

Biology

A relict (or relic) is an organism that at an earlier time was abundant in a large area but now occurs at only one or a few small areas.

Geology and geomorphology

In geology, a r ...

" of somebody."Kerr, 1995, p. 60.

Susan B. Anthony

Susan B. Anthony (born Susan Anthony; February 15, 1820 – March 13, 1906) was an American social reformer and women's rights activist who played a pivotal role in the women's suffrage movement. Born into a Quaker family committed to s ...

, who was not at the convention, later said it was reading this speech that converted her to the cause of women's rights.

Stone paid to have the proceedings of the convention printed as booklets; she would repeat this practice after each of the next six annual conventions. The booklets were sold at her lectures and at subsequent conventions as Woman's Rights Tracts.Blackwell, 1930, p. 100.

The report of the convention in the ''New York Tribune for Europe'' inspired women in Sheffield, England, to draw up a petition for woman suffrage and present it to the House of Lords and Harriet Taylor Mill

Harriet Taylor Mill (née Hardy; 8 October 1807 – 3 November 1858) was a British philosopher and women's rights advocate. Her extant corpus of writing can be found in ''The Complete Works of Harriet Taylor Mill''. Several pieces can also be fo ...

in 1851 to write ''The Enfranchisement of Women.'' Harriet Martineau

Harriet Martineau (; 12 June 1802 – 27 June 1876) was an English social theorist often seen as the first female sociologist, focusing on racism, race relations within much of her published material.Michael R. Hill (2002''Harriet Martineau: Th ...

wrote a letter to Davis in August 1851 to thank her for sending a copy of the proceedings: "I hope you are aware of the interest excited in this country by that Convention, the strongest proof of which is the appearance of an article on the subject in the ''Westminster Review

The ''Westminster Review'' was a quarterly British publication. Established in 1823 as the official organ of the Philosophical Radicals, it was published from 1824 to 1914. James Mill was one of the driving forces behind the liberal journal until ...

'' ... I am not without hope that this article will materially strengthen your hands, and I am sure it can not but cheer your hearts."

1851 in Worcester

A second national convention was held October 15–16, 1851, again in Brinley Hall, with Paulina Kellogg Wright Davis presiding. Harriet Kezia Hunt and Antoinette Brown gave speeches, while a letter from Elizabeth Cady Stanton was read. Lucretia Mott served as an officer of the meeting.National Park Service. Women's Rights''More Women's Rights Conventions''.

Retrieved on April 1, 2009.

Wendell Phillips made a speech which was so persuasive that it would be sold as a tract until 1920:

Wendell Phillips made a speech which was so persuasive that it would be sold as a tract until 1920:

Elizabeth Oakes Smith

Elizabeth Oakes Smith ( Prince; August 12, 1806 – November 16, 1893) was a poet, fiction writer, editor, lecturer, and women's rights activist whose career spanned six decades, from the 1830s to the 1880s. Most well-known at the start of her ...

, journalist, author, and member of New York's literary circle attended the 1850 convention, and in 1851 was asked to take the platform. Afterward, she defended the convention and its leaders in articles she wrote for the ''New York Tribune''.

Abby Kelley Foster gave testimony to the persecution she had suffered as a woman: "My life has been my speech. For fourteen years I have advocated this cause by my daily life. Bloody feet, sisters, have worn smooth the path by which you have come hither."McMillen, 2008, p. 110. Abby H. Price spoke about prostitution, as she had the year before, arguing that too many women fell to prostitution because they did not have the job opportunities or education that men had.

A letter was read from two imprisoned French feminists, Pauline Roland

Pauline Roland (1805, Falaise, Calvados – 15 December 1852) was a French feminist and socialist.

Upon her mother's insistence, Roland received a good education and was introduced to the ideas of Claude Henri de Rouvroy, Comte de Saint-Simon, ...

and Jeanne Deroin

Jeanne Deroin (31 December 1805 – 2 April 1894) was a French socialist feminist. She spent the latter half of her life in exile in London, where she continued her organising activities.

Early life

Born in Paris, Deroin became a seamstress. In ...

, saying "Your courageous declaration of Woman's Rights has resounded even to our prison, and has filled our souls with inexpressible joy."

Ernestine Rose gave a speech about the loss of identity in marriage that Davis later characterized as "unsurpassed". Rose said of woman that "At marriage, she loses her entire identity, and her being is said to have become merged in her husband. Has nature thus merged it? Has she ceased to exist and feel pleasure and pain? When she violates the laws of her being, does her husband pay the penalty? When she breaks the moral law does he suffer the punishment? When he satisfies his wants, is it enough to satisfy her nature? ... What an inconsistency that from the moment she enters the compact in which she assumes the high responsibility of wife and mother, she ceases legally to exist and becomes a purely submissive being. Blind submission in women is considered a virtue, while submission to wrong is itself wrong, and resistance to wrong is virtue alike in women as in man."Brandeis University. Women's Studies Research Center''Ernestine Rose's speech at the Women's Rights Convention in Worcester, Massachusetts in October 15, 1851''

Retrieved on April 1, 2009.

1852 in Syracuse

For the third convention, the city hall in

For the third convention, the city hall in Syracuse, New York

Syracuse ( ) is a City (New York), city in and the county seat of Onondaga County, New York, Onondaga County, New York, United States. It is the fifth-most populous city in the state of New York following New York City, Buffalo, New York, Buffa ...

was selected as the site. Because Syracuse was nearer to Seneca Falls (two days' travel by horse, several hours' journey by rail), more of the original signers of the Declaration of Sentiments were able to attend than the previous two conventions in Massachusetts. Lucretia Mott was named president; at one point she felt it necessary to silence a minister who offended the assembly by using biblical references to keep women subordinate to men. A letter from Elizabeth Cady Stanton was read and its resolutions voted on. At sessions taking place September 8–10, 1852, Susan B. Anthony

Susan B. Anthony (born Susan Anthony; February 15, 1820 – March 13, 1906) was an American social reformer and women's rights activist who played a pivotal role in the women's suffrage movement. Born into a Quaker family committed to s ...

and Matilda Joslyn Gage

Matilda Joslyn Gage (March 24, 1826 – March 18, 1898) was an American writer and activist. She is mainly known for her contributions to women's suffrage in the United States (i.e. the right to vote) but she also campaigned for Native Americ ...

made their first public speeches on women's rights.Blackwell, 1930, p. 101. Ernestine Rose spoke denouncing duties without rights, saying "as a woman has to pay taxes to maintain government, she has a right to participate in the formation and administration of it." Antoinette Brown called for more women to become ministers, claiming that the Bible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts of a ...

did not forbid it. Ernestine Rose stood up in response, saying that the Bible should not be used as the authority for settling a dispute, especially as it contained much contradiction regarding women. Elizabeth Oakes Smith called for women to have their own journal so that they could become independent of the male-owned press, saying "We should have a literature of our own, a printing press and a publishing house, and tract writers and distributors, as well as lectures and conventions; and yet I say this to a race of beggars, for women have no pecuniary resources." Antoinette Brown lectured about how masculine law can never fully represent womankind. Lucy Stone wore a trousered dress often referred to as "bloomers", a more practical style she had picked up during the summer after meeting Amelia Bloomer

Amelia Jenks Bloomer (May 27, 1818 – December 30, 1894) was an American newspaper editor, women's rights and temperance advocate. Even though she did not create the women's clothing reform style known as bloomers, her name became associate ...

. She spoke to say "The woman who first departs from the routine in which society allows her to move must suffer. Let us bravely bear ridicule and persecution for the sake of the good that will result, and when the world sees that we can accomplish what we undertake, it will acknowledge our right." The Syracuse ''Weekly Chronicle'' was impressed less by her costume than by her electrifying address, printing "Well, whether ''we'' like it or not, little woman, ''God'' made you an ORATOR!"

Reverend Lydia Ann Jenkins of Geneva, New York

Geneva is a City (New York), city in Ontario County, New York, Ontario and Seneca County, New York, Seneca counties in the U.S. state of New York (state), New York. It is at the northern end of Seneca Lake (New York), Seneca Lake; all land port ...

spoke at the convention and asked, "Is there any law to prevent women from voting in this State? The Constitution says 'white male citizens' may vote, but does not say that white female citizens may not." The next year, Jenkins was chosen member of the committee tasked with framing the issue of suffrage before the New York Legislature

The New York State Legislature consists of the two houses that act as the state legislature of the U.S. state of New York: The New York State Senate and the New York State Assembly. The Constitution of New York does not designate an official t ...

.

A motion was made to form a national organization for women, but after animated discussion, no consensus was reached. Elizabeth Smith Miller

Elizabeth Smith Miller ( Smith; September 20, 1822 – May 23, 1911), known as "Libby", was an American advocate and financial supporter of the women's rights movement.NY History Net (April 21, 2011).

Biography

Elizabeth Smith was born Septembe ...

suggested the women form organizations at the state level, but even this milder suggestion met with opposition. Paulina Kellogg Wright Davis said, "I hate organizations ... they cramp me."McMillen, 2008, p. 113. Lucretia Mott concurred, saying "the seeds of dissolution be less likely to be sown." Angelina Grimké Weld, Thomas M'Clintock

Thomas M'Clintock (March 28, 1792 – March 19, 1876) was an American pharmacist and a leading Quaker organizer for many reforms, including abolishing slavery, achieving women's rights, and modernizing Quakerism.

Life

He was born on Marc ...

and Wendell Phillips agreed, with Phillips saying "you will develop divisions among yourselves." No national organization was to form until after the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

.

1853 in Cleveland

At Melodeon Hall inCleveland, Ohio

Cleveland ( ), officially the City of Cleveland, is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Cuyahoga County. Located in the northeastern part of the state, it is situated along the southern shore of Lake Erie, across the U.S. ...

, on October 6–8, 1853, William Lloyd Garrison spoke to say "...the Declaration of Independence as put forth at Seneca Falls. ... was measuring the people of this country by their own standard. It was taking their own words and applying their own principles to women, as they have been applied to men."

Earlier in the year, a regional Women's Rights Convention in New York City had been interrupted by unruly men in the audience, with most of the speakers being unheard over shouts and hisses. Organizers of the fourth national convention were concerned that a repetition of that mob scene does not take place. In Cleveland, objections were raised regarding Bible interpretations, and orderly discussion proceeded.

Earlier in the year, a regional Women's Rights Convention in New York City had been interrupted by unruly men in the audience, with most of the speakers being unheard over shouts and hisses. Organizers of the fourth national convention were concerned that a repetition of that mob scene does not take place. In Cleveland, objections were raised regarding Bible interpretations, and orderly discussion proceeded.

Frances Dana Barker Gage

Frances Dana Barker Gage (pen name, Aunt Fanny; October 12, 1808November 10, 1884) was a leading American reformer, feminist and abolitionist. She worked closely with Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, along with other leaders of the ...

served as president for the 1,500 participants. Lucretia Mott, Amy Post

Amy Kirby Post (December 20, 1802 – January 29, 1889) was an activist who was central to several important social causes of the 19th century, including the abolition of slavery and women's rights. Post's upbringing in Quakerism shaped her belie ...

, and Martha Coffin Wright

Martha Coffin Wright (December 25, 1806 – 1875) was an American feminist, abolitionist, and signatory of the Declaration of Sentiments who was a close friend and supporter of Harriet Tubman.

Early life

Martha Coffin was born in Boston, Mass ...

served as officers; James Mott

James Mott (20 June 1788 – 26 January 1868) was a Quaker leader, teacher, merchant, and anti-slavery activist. He was married to suffragist leader Lucretia Mott.

Life and work

James was born in Cow Neck in North Hempstead on Long Island, t ...

served on the business committee, and Lucretia Mott called the meeting to order.

In a letter read aloud, William Henry Channing suggested that the convention issue its own Declaration of Women's Rights and petitions to state legislatures seeking woman suffrage, equal inheritance rights, equal guardianship laws, divorce for wives of alcoholics, tax exemptions for women until given the right to vote, and right to trial before a jury of female peers. Lucretia Mott moved the adoption of the Seneca Falls Declaration of Sentiments, which was read to the convention, debated, then referred to a committee to draft a new declaration. Antoinette Brown, William Lloyd Garrison, Lucretia Mott, Ernestine Rose and Lucy Stone worked to shape a new declaration, and the result was read at the end of the meeting, but was never adopted.

''The Plain Dealer

''The Plain Dealer'' is the major newspaper of Cleveland, Ohio, United States. In fall 2019, it ranked 23rd in U.S. newspaper circulation, a significant drop since March 2013, when its circulation ranked 17th daily and 15th on Sunday.

As of Ma ...

'' printed an extensive account of the convention, opining of Ernestine Rose that she "is the master-spirit of the Convention. She is described as a Polish lady of great beauty, being known in this country as an earnest advocate of human liberty."Stanton et al, 1881, p. 145. After commenting on the bloomer costume worn by Lucy Stone, ''The Plain Dealer'' continued: "Miss Stone must be set down as a lady of no common abilities, and of uncommon energy in the pursuit of a cherished idea. She is a marked favorite in the Conventions."

1854 in Philadelphia

At Sansom Street Hall in

At Sansom Street Hall in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

over three days October 18–20, 1854, Ernestine Rose was chosen president in spite of her atheism

Atheism, in the broadest sense, is an absence of belief in the existence of deities. Less broadly, atheism is a rejection of the belief that any deities exist. In an even narrower sense, atheism is specifically the position that there no d ...

. Susan B. Anthony supported her, saying "every religion – or none – should have an equal right on the platform".American Atheists''Ernestine Rose: A Troublesome Female''.

Retrieved on April 1, 2009. Rose spoke out to the gathering, saying "Our claims are based on that great and immutable truth, the rights of all humanity. For is woman not included in that phrase, 'all men are created ... equal'?. ... Tell us, ye men of the nation ... whether woman is not included in that great

Declaration of Independence

A declaration of independence or declaration of statehood or proclamation of independence is an assertion by a polity in a defined territory that it is independent and constitutes a state. Such places are usually declared from part or all of the ...

?" She continued "I will no more promise how we shall use our rights than man has promised before he obtained them, how he would use them."

Susan B. Anthony spoke to urge attendees to petition their state legislatures for laws giving women equal rights. A committee was formed to publish tracts and to place articles in national newspapers. Once again, the convention could not agree on a motion to create a national organization, resolving instead to continue work at the local level with coordination provided by a committee chaired by Paulina Kellogg Wright Davis.

Henry Grew

Henry Grew (1781 – August 8, 1862) was a Christian teacher and writer whose studies of the Bible led him to conclusions which were at odds with doctrines accepted by many of the mainstream churches of his time. Among other things, he rejected th ...

took the speaker's platform to condemn women who demanded equal rights. He described examples from the Bible which assigned to women a subordinate role. Lucretia Mott flared up and debated him, saying that he was selectively using the Bible to put upon women a sense of order that originated in man's mind. She said "The pulpit has been prostituted, the Bible has been ill-used ... Instead of taking the truths of the Bible in corroboration of the right, the practice has been to turn over its pages to find examples and authority for the wrong."McMillen, 2008, p. 113. Mott cited Bible passages that proved Grew wrong. William Lloyd Garrison stood up to halt the debate, saying that nearly everyone present agreed that all were equal in the eyes of God.

1855 in Cincinnati

At Smith & Nixon's Hall in

At Smith & Nixon's Hall in Cincinnati, Ohio

Cincinnati ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located at the northern side of the confluence of the Licking and Ohio rivers, the latter of which marks the state line wit ...

on October 17–18, 1855, Martha Coffin Wright presided over the standing room only

An event is described as standing-room only when it is so well-attended that all of the chairs in the venue are occupied, leaving only flat spaces of pavement or flooring for other attendees to stand, at least those spaces not restricted by occup ...

crowd. Wright, a younger sister of Lucretia Mott and a founding member of the first Seneca Falls Convention, contrasted the large hall packed with supporters to the much smaller gathering in 1848, called "in timidity and doubt of our own strength, our own capacity, our own powers".

Antoinette Brown, Ernestine Rose, Josephine Sophia White Griffing

Josephine Sophia White Griffing (December 18, 1814 – February 18, 1872) was an American reformer who campaigned against slavery and for women's rights. In Litchfield, Ohio their home was a stop on the Underground Railroad and she worked as a l ...

and Frances Dana Barker Gage spoke to the crowd, listing for them the achievements and progress made thus far. Lucy Stone spoke for the right of each person to establish for themselves which sphere, domestic or public, they should be active in.McMillen, 2008, p. 111. A heckler interrupted the proceedings, calling female speakers "a few disappointed women". Stone responded with a retort that became widely quoted, saying that yes, she was indeed a "disappointed woman". "...In education, in marriage, in religion, in everything, disappointment is the lot of woman. It shall be the business of my life to deepen this disappointment in every woman's heart until she bows down to it no longer."

1856 in New York

At the Broadway Tabernacle in New York City on November 25–26, 1856, Lucy Stone served as president, and recounted for the crowd the recent progress in women's property rights laws passing in nine states, as well as a limited ability for widows in Kentucky to vote for school board members. She noted with satisfaction that the new Republican Party was interested in female participation during the 1856 elections. Lucretia Mott encouraged the assembly to use their new rights, saying, "Believe me, sisters, the time is come for you to avail yourselves of all the avenues that are opened to you."

A letter was read aloud from

At the Broadway Tabernacle in New York City on November 25–26, 1856, Lucy Stone served as president, and recounted for the crowd the recent progress in women's property rights laws passing in nine states, as well as a limited ability for widows in Kentucky to vote for school board members. She noted with satisfaction that the new Republican Party was interested in female participation during the 1856 elections. Lucretia Mott encouraged the assembly to use their new rights, saying, "Believe me, sisters, the time is come for you to avail yourselves of all the avenues that are opened to you."

A letter was read aloud from Antoinette Brown Blackwell

Antoinette Louisa Brown, later Antoinette Brown Blackwell (May 20, 1825 – November 5, 1921), was the first woman to be ordained as a mainstream Protestant minister in the United States. She was a well-versed public speaker on the paramount iss ...

: "Would it not be wholly appropriate, then, for this National Convention to demand the right of suffrage for her from the Legislature of each State in the Nation? We can not petition the General Government on this point. Allow me, therefore, respectfully to suggest the propriety of appointing a committee, which shall be instructed to prepare a memorial adapted to the circumstances of each legislative body; and demanding of each, in the name of this Convention, the elective franchise for woman."Stanton et al, 1881, p. 863. A motion was passed approving of the suggestion, and Wendell Phillips recommended that women in each state be contacted and encouraged to take the memorial petition to their respective legislative bodies.

1858 in New York

For the eighth and subsequent national conventions, the meetings were changed from various dates in autumn to a more consistent mid-May schedule. 1857 was skipped – the next meeting was held in 1858. At Mozart Hall in New York City on May 13–14, 1858, Susan B. Anthony held the post of president. William Lloyd Garrison spoke, saying "Those who have inaugurated this movement are worthy to be ranked with the army of martyrs ... in the days of old. Blessings on them! They should triumph, and every opposition be removed, that peace and love, justice and liberty, might prevail throughout the world." Garrison proposed not only that women should serve as elected officials, but that the number of female legislators should equal that of male. Frederick Douglass took the stage to speak after repeated calls from the audience. Lucy Stone, Reverend Antoinette Brown Blackwell (now married toSamuel Charles Blackwell

Samuel Charles Blackwell (1823–1901) was an Anglo-American abolitionist.

Biography

Blackwell was born in England, the son of Bristol sugar refiner Samuel Blackwell (c. 1790–August 7, 1838) and Hannah Lane, who moved their family of eight chil ...

), Reverend Thomas Wentworth Higginson

Thomas Wentworth Higginson (December 22, 1823May 9, 1911) was an American Unitarian minister, author, abolitionist, politician, and soldier. He was active in the American Abolitionism movement during the 1840s and 1850s, identifying himself with ...

and Lucretia Mott were among those that spoke. Stephen Pearl Andrews

Stephen Pearl Andrews (March 22, 1812 – May 21, 1886) was an American libertarian socialist, individualist anarchist, linguist, political philosopher, outspoken Abolitionism in the United States, abolitionist and author of several books on the ...

startled the assemblage by advocating free love

Free love is a social movement that accepts all forms of love. The movement's initial goal was to separate the state from sexual and romantic matters such as marriage, birth control, and adultery. It stated that such issues were the concern ...

and unconventional approaches to marriage. He hinted at birth control

Birth control, also known as contraception, anticonception, and fertility control, is the use of methods or devices to prevent unwanted pregnancy. Birth control has been used since ancient times, but effective and safe methods of birth contr ...

by insisting that women should have the right to put a limit on "the cares and sufferings of maternity". Eliza Farnham

Eliza Farnham (November 17, 1815 – December 15, 1864) was a 19th-century American novelist, feminist, Abolitionism in the United States, abolitionist, and activist for prison reform.

Biography

She was born in Rensselaerville, New York. She mo ...

presented her view that women were superior to men, a concept that was hotly debated. The convention, marred by interruption and rowdyism, "adjourned amid great confusion".

1859 in New York

Held again at Mozart Hall in New York City on May 12, 1859, the ninth national convention opened with Lucretia Mott presiding.Caroline Wells Healey Dall

Caroline Wells Dall ( Healey; June 22, 1822 – December 17, 1912) was an American feminist writer, transcendentalist, and reformer. She was affiliated with the National Women's Rights Convention, the New England Women's Club, and the American S ...

read out the resolutions including one intended to be sent to every state legislature, urging that body to "secure to women all those rights and privileges and immunities which in equity belong to every citizen of a republic".

Another unruly crowd made it difficult to hear the speeches of Antoinette Brown Blackwell, Caroline Dall, Lucretia Mott and Ernestine Rose. Wendell Phillips stood to speak and "held that mocking crowd in the hollow of his hand".

1860 in New York

At theCooper Union

The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art (Cooper Union) is a private college at Cooper Square in New York City. Peter Cooper founded the institution in 1859 after learning about the government-supported École Polytechnique in ...

in New York City on May 10–11, 1860, the tenth national convention of 600–800 attendees was presided over by Martha Coffin Wright. A recent legislative victory in New York was praised, one which gave women joint custody of their children and sole use of their personal property and wages.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Antoinette Brown Blackwell moved to add a resolution calling for legislation on marriage reform; they wanted laws that would give women the right to separate from or divorce a husband who had demonstrated drunkenness, insanity, desertion or cruelty. Wendell Phillips argued against the resolution, fracturing the executive committee on the matter. Susan B. Anthony also supported the measure, but it was defeated by vote after a heated debate.

Horace Greeley wrote in the ''Tribune'' that there were "One Thousand Persons Present, seven-eighths of them Women, and a fair Proportion Young and Good-looking". Greeley, a foe of marriage reform, continued against Stanton's proposed resolution with a jab at "easy Divorce", writing that the word 'Woman' should be replaced in the convention's title with "Wives Discontented".Stanton et al, 1881, p. 740.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Antoinette Brown Blackwell moved to add a resolution calling for legislation on marriage reform; they wanted laws that would give women the right to separate from or divorce a husband who had demonstrated drunkenness, insanity, desertion or cruelty. Wendell Phillips argued against the resolution, fracturing the executive committee on the matter. Susan B. Anthony also supported the measure, but it was defeated by vote after a heated debate.

Horace Greeley wrote in the ''Tribune'' that there were "One Thousand Persons Present, seven-eighths of them Women, and a fair Proportion Young and Good-looking". Greeley, a foe of marriage reform, continued against Stanton's proposed resolution with a jab at "easy Divorce", writing that the word 'Woman' should be replaced in the convention's title with "Wives Discontented".Stanton et al, 1881, p. 740.

Civil War and beyond

The coming of theAmerican Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

ended the annual National Women's Rights Convention and focused women's activism on the issue of emancipation

Emancipation generally means to free a person from a previous restraint or legal disability. More broadly, it is also used for efforts to procure economic and social rights, political rights or equality, often for a specifically disenfranchis ...

for slaves. The New York state legislature repealed in 1862 much of the gain women had made in 1860. Susan B. Anthony was "sick at heart" but could not convince women activists to hold another convention focusing solely on women's rights.

In 1863, Elizabeth Cady Stanton recently moved to New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

to join with Susan B. Anthony to send a call out, via the woman's central committee chaired by Paulina Kellogg Wright Davis, to all the "Loyal Women of the Nation" to meet again in convention in May. Forming the Woman's National Loyal League were Stanton, Anthony, Martha Coffin Wright, Amy Post, Antoinette Brown Blackwell, Ernestine Rose, Angelina Grimké Weld, and Lucy Stone, among others. They organized the First Woman's National Loyal League Convention at the Church of the Puritans in New York City on May 14, 1863, and worked to gain 400,000 signatures by 1864 to petition the United States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is bicameral, composed of a lower body, the House of Representatives, and an upper body, the Senate. It meets in the U.S. Capitol in Washing ...

to pass the Thirteenth Amendment abolishing slavery.

1866 in New York

On May 10th of 1866, the Eleventh National Women's Rights Convention was held at Church of the Puritans in Union Square. Called by Stanton and Anthony, the meeting included Ernestine L. Rose, Wendell Phillips, Reverend John T. Sargent, ReverendOctavius Brooks Frothingham

Octavius Brooks Frothingham (November 26, 1822 – November 27, 1895) was an American clergyman and author.

Biography

He was born in Boston, Massachusetts, the son of Nathaniel Langdon Frothingham (1793–1870), a prominent Unitarian preacher ...

, Frances D. Gage, Elizabeth Brown Blackwell, Theodore Tilton

Theodore Tilton (October 2, 1835 – May 29, 1907) was an American newspaper editor, poet and abolitionist. He was born in New York City to Silas Tilton and Eusebia Tilton (same surname). On his twentieth birthday, October 2, 1855, he married ...

, Lucretia Mott, Martha C. Wright, Stephen Symonds Foster and Abbey Kelley Foster, Margaret Winchester and Parker Pillsbury Parker Pillsbury (September 22, 1809 – July 7, 1898) was an American minister and advocate for abolition and women's rights.

Life

Pillsbury was born in Hamilton, Massachusetts. He moved to Henniker, New Hampshire where he later farmed and w ...

, and was presided over by Stanton.

A stirring speech against racial discrimination was given by African-American activist Frances Ellen Watkins Harper

Frances Ellen Watkins Harper (September 24, 1825 – February 22, 1911) was an American Abolitionism in the United States, abolitionist, suffragist, poet, Temperance movement, temperance activist, teacher, public speaker, and writer. Beginning in 1 ...

, in which she said "You white women speak here of rights. I speak of wrongs. I, as a colored woman, have had in this country an education which has made me feel as if I were in the situation of Ishmael, my hand against every man, and every man's hand against me."

A few weeks later, on May 31, 1866, the first meeting of the American Equal Rights Association

The American Equal Rights Association (AERA) was formed in 1866 in the United States. According to its constitution, its purpose was "to secure Equal Rights to all American citizens, especially the right of suffrage, irrespective of race, color o ...

was held in Boston.

1869 in Washington, D.C.

An event that was reported as "The twelfth regular National Convention of Women's Rights" was held on January 19, 1869. Prominent speakers included Lucretia Mott, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, SenatorSamuel Clarke Pomeroy

Samuel Clarke Pomeroy (January 3, 1816 – August 27, 1891) was a United States senator from Kansas in the mid-19th century. He served in the United States Senate during the American Civil War. Pomeroy also served in the Massachusetts House of ...

, Parker Pillsbury, John Willis Menard

John Willis Menard (April 3, 1838 – October 8, 1893) was a federal government employee, poet, newspaper publisher and politician born in Kaskaskia, Illinois to parents who were Louisiana Creoles from New Orleans. After moving to New Orleans, on ...

and Doctor Sarah H. Hathaway. Doctor Mary Edwards Walker

Mary Edwards Walker, M.D. (November 26, 1832 – February 21, 1919), commonly referred to as Dr. Mary Walker, was an American abolitionist, prohibitionist, prisoner of war and surgeon. She is the only woman to ever receive the Medal of Honor. ...

and a "Mrs. Harman" were seen in "male attire" actively passing back and forth between the audience and the stage.

Stanton spoke heatedly with a prepared speech against those who had established "an aristocracy of sex on this continent". "If serfdom, peasantry, and slavery have shattered kingdoms, deluged continents with blood, scattered republics like dust before the wind, and rent our own Union asunder, what kind of a government, think you, American statesmen, you can build, with the mothers of the race crouching at your feet ... ?" Other speeches were off-the-cuff, and little record is known of them.Buhle, 1978, p. 249

See also

*"Ain't I a Woman?

"Ain't I a Woman?" is a speech, delivered extemporaneously, by Sojourner Truth (1797–1883), born into slavery in New York State. Some time after gaining her freedom in 1827, she became a well known anti-slavery speaker. Her speech was deliver ...

" speech by Sojourner Truth

Sojourner Truth (; born Isabella Baumfree; November 26, 1883) was an American abolitionist of New York Dutch heritage and a women's rights activist. Truth was born into slavery in Swartekill, New York, but escaped with her infant daughter to f ...

, delivered in 1851 at the Ohio Women's Rights Convention in Akron, Ohio

Akron () is the fifth-largest city in the U.S. state of Ohio and is the county seat of Summit County, Ohio, Summit County. It is located on the western edge of the Glaciated Allegheny Plateau, about south of downtown Cleveland. As of the 2020 C ...

*Ohio Women's Convention at Salem in 1850 The Ohio Women's Convention at Salem in 1850 met on April 19–20, 1850 in Salem, Ohio, a center for reform activity. It was the third in a series of women's rights conventions that began with the Seneca Falls Convention of 1848. It was the first o ...

*Pennsylvania Woman's Convention at West Chester in 1852

The Pennsylvania Woman's Convention at West Chester in 1852 was held in West Chester, Pennsylvania on June 2 and 3. The convention attracted many Women's rights, women's rights activists from around the United States. The convention discussed women ...

*Seneca Falls Convention

The Seneca Falls Convention was the first women's rights convention. It advertised itself as "a convention to discuss the social, civil, and religious condition and rights of woman".Wellman, 2004, p. 189 Held in the Wesleyan Methodist Church ...

* Equal Rights Amendment

The Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) is a proposed amendment to the United States Constitution designed to guarantee equal legal rights for all American citizens regardless of sex. Proponents assert it would end legal distinctions between men and ...

(ERA)

* Reproductive rights

Reproductive rights are legal rights and freedoms relating to reproduction and reproductive health that vary amongst countries around the world. The World Health Organization defines reproductive rights as follows:

Reproductive rights rest on t ...

– issues regarding "reproductive freedom"

* Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW)

* Vindication of the Rights of Women

''A Vindication of the Rights of Woman: with Strictures on Political and Moral Subjects'' (1792), written by British philosopher and women's rights advocate Mary Wollstonecraft (1759–1797), is one of the earliest works of feminist philosoph ...

* Women's right to know

* Committee on Women's Rights and Gender Equality The Committee on Women's Rights and Gender Equality (FEMM) is a committee of the European Parliament.

Membership Chair

Vice Chairs

*Eugenia Rodríguez Palop

*Sylwia Spurek

* Elissavet Vozemberg-Vrionidi

*Robert Biedroń

Members

*Regina Bastos ...

* Subjection of women

* League of Women Voters

The League of Women Voters (LWV or the League) is a nonprofit, nonpartisan political organization in the United States. Founded in 1920, its ongoing major activities include registering voters, providing voter information, and advocating for vot ...

* In Defense of Women

''In Defense of Women'' is H. L. Mencken's 1918 book on women and the relationship between the sexes. Some laud the book as progressive while others brand it as reactionary. While Mencken did not champion women's rights, he described women as ...

* Parental leave

Parental leave, or family leave, is an employee benefit available in almost all countries. The term "parental leave" may include maternity, Paternity (law), paternity, and adoption leave; or may be used distinctively from "maternity leave" an ...

* Feminism

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social equality of the sexes. Feminism incorporates the position that society prioritizes the male po ...

* History of feminism

The history of feminism comprises the narratives (chronological or thematic) of the movements and ideologies which have aimed at equal rights for women. While feminists around the world have differed in causes, goals, and intentions depending ...

* First-wave feminism

First-wave feminism was a period of feminist activity and thought that occurred during the 19th and early 20th century throughout the Western world. It focused on legal issues, primarily on securing women's right to vote. The term is often used s ...

* List of suffragists and suffragettes

This list of suffragists and suffragettes includes noted individuals active in the worldwide women's suffrage movement who have campaigned or strongly advocated for women's suffrage, the organisations which they formed or joined, and the public ...

* Timeline of women's suffrage

Women's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the right of women to vote in elections. Beginning in the start of the 18th century, some people sought to change voting laws to allow women to vote. Liberal political parties would go on to grant ...

* Timeline of women's rights (other than voting)

Timeline of women's legal rights (other than voting) represents formal changes and reforms regarding women's rights. The changes include actual law reforms as well as other formal changes, such as reforms through new interpretations of laws by ...

* Women's suffrage in the United States

In the 1700's to early 1800's New Jersey did allow Women the right to vote before the passing of the 19th Amendment, but in 1807 the state restricted the right to vote to "...tax-paying, white male citizens..."

Women's legal right to vote w ...

* Women's suffrage organizations

This list of suffragists and suffragettes includes noted individuals active in the worldwide women's suffrage movement who have campaigned or strongly advocated for women's suffrage, the organisations which they formed or joined, and the #Women ...

References

Notes

Bibliography

* Anthony, Susan B.; Stanton, Elizabeth Cady; Gage, Matilda Joslyn''History of Woman Suffrage, Volume III''

covering 1876–1885. Copyright 1886. * Baker, Jean H.

''Sisters: The Lives of America's Suffragists.''

Hill and Wang, New York, 2005. * Baker, Jean H

''Votes for Women: The Struggle for Suffrage Revisited.''

Oxford University Press, 2002. * Blackwell, Alice Stone

''Lucy Stone: Pioneer of Woman's Rights.''

Charlottesville and London: University Press of Virginia, 2001. * Buhle, Mari Jo; Buhle, Paul

''The concise history of woman suffrage.''

University of Illinois, 1978. * Hays, Elinor Rice

''Morning Star: A Biography of Lucy Stone 1818–1893.''

Harcourt, Brace & World, 1961. * Lasser, Carol and Merrill, Marlene Deahl, editors

''Friends and Sisters: Letters between Lucy Stone and Antoinette Brown Blackwell, 1846–93''

University of Illinois Press, 1987. * Kerr, Andrea Moore

''Lucy Stone: Speaking Out for Equality.''

New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 1992. * Mani, Bonnie G

''Women, Power, and Political Change.''

Lexington Books, 2007. * McMillen, Sally Gregory

''Seneca Falls and the origins of the women's rights movement.''

Oxford University Press, 2008. * Million, Joelle

''Woman's Voice, Woman's Place: Lucy Stone and the Birth of the Women's Rights Movement.''

Praeger, 2003.

''Proceedings of the Eleventh National Woman's Rights Convention, Held at the Church of the Puritans, New York, May 10, 1866. Phonographic Report by H.M. Parkhurst''. New York: Robert J. Johnson, 1866.

''Proceedings of the Seventh National Woman's Rights Convention, Held in New York City at the Broadway Tabernacle, on Tuesday and Wednesday, Nov. 25 & 26, 1856''. New York: Edward O. Jenkins, 1856. *

''Proceedings of the Tenth National Woman's Rights Convention, Held at the Cooper Institute, New York City, May 10th and 11th, 1860''. Boston: Yerrinton and Garrison, 1860

''Proceedings of the Woman's Rights Convention, Held at Syracuse, September 8th, 9th, and 10th, 1852''. Syracuse: J. E. Masters, 1852.

''Proceedings of the Woman's Rights Convention, Held at Worcester, October 15th and 16th,1851''. New York; Fowlers and Wells, 1852. * Schenken, Suzanne O'Dea

''From Suffrage to the Senate.''

Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 1999. pp. 644–646. * Spender, Dale. (1982

''Women of Ideas and what Men Have Done to Them.''

Ark Paperbacks, Routledge & Kegan Paul, London, 1983, pp. 347–357. * Stanton, Elizabeth Cady; Anthony, Susan B.; Gage, Matilda Joslyn

''History of Woman Suffrage, Volume I''

covering 1848–1861. Copyright 1881. * Wheeler, Leslie. "Lucy Stone: Radical beginnings (1818–1893)" in Spender, Dale (ed.

''Feminist theorists: Three centuries of key women thinkers''

Pantheon 1983, pp. 124–136.

External links

* National Park Service. Women's Rights1850–1863 * Gutenberg Project

''History of Woman Suffrage, Volume I''

1881, by Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony and Matilda Joslyn Gage. * Worcester Women's History Project

related to 1850 and 1851 conventions {{Portal bar, Feminism History of New York (state) History of Massachusetts History of women's rights in the United States 1850 in American politics 1850 in women's history Women's suffrage advocacy groups in the United States Women in New York (state) Women in Massachusetts National Women’s Rights Convention (1850