Nahda on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Nahda ( ar, النهضة, translit=an-nahḍa, meaning "the Awakening"), also referred to as the Arab Awakening or Enlightenment, was a cultural movement that flourished in Arabic-speaking regions of the

/ref> The renaissance itself started simultaneously in both Egypt and

Ahmad Faris al-Shidyaq (born 1805 or 1806 as Faris ibn Yusuf al-Shidyaq; died 1887) grew up in present-day Lebanon. A Maronite Christian by birth, he later lived in major cities of the Arabic-speaking world, where he had his career. He converted to Protestantism during the nearly two decades that he lived and worked in Cairo, present-day Egypt, from 1825 to 1848. He also spent time on the island of Malta. Participating in an Arabic translation of the Bible in Great Britain that was published in 1857, Faris lived and worked there for 7 years, becoming a British citizen. He next moved to Paris, France, for two years in the early 1850s, where he wrote and published some of his most important work.

Later in the 1850s Faris moved to Tunisia, where in 1860 he converted to Islam, taking the first name Ahmad. Moving to Istanbul later that year to work as a translator at the request of the Ottoman government, Faris also founded an Arabic-language newspaper. It was supported by the Ottomans, Egypt and Tunisia, publishing until the late 1880s.

Faris continued to promote Arabic language and culture, resisting the 19th-century "Turkization" pushed by the Ottomans based in present-day Turkey. Shidyaq is considered to be one of the founding fathers of modern Arabic literature; he wrote most of his fiction in his younger years.

Ahmad Faris al-Shidyaq (born 1805 or 1806 as Faris ibn Yusuf al-Shidyaq; died 1887) grew up in present-day Lebanon. A Maronite Christian by birth, he later lived in major cities of the Arabic-speaking world, where he had his career. He converted to Protestantism during the nearly two decades that he lived and worked in Cairo, present-day Egypt, from 1825 to 1848. He also spent time on the island of Malta. Participating in an Arabic translation of the Bible in Great Britain that was published in 1857, Faris lived and worked there for 7 years, becoming a British citizen. He next moved to Paris, France, for two years in the early 1850s, where he wrote and published some of his most important work.

Later in the 1850s Faris moved to Tunisia, where in 1860 he converted to Islam, taking the first name Ahmad. Moving to Istanbul later that year to work as a translator at the request of the Ottoman government, Faris also founded an Arabic-language newspaper. It was supported by the Ottomans, Egypt and Tunisia, publishing until the late 1880s.

Faris continued to promote Arabic language and culture, resisting the 19th-century "Turkization" pushed by the Ottomans based in present-day Turkey. Shidyaq is considered to be one of the founding fathers of modern Arabic literature; he wrote most of his fiction in his younger years.

Butrus al-Bustani (1819–1893) was born to a Lebanese Maronite Christian family in the village of Dibbiye in the

Butrus al-Bustani (1819–1893) was born to a Lebanese Maronite Christian family in the village of Dibbiye in the

Hayreddin Pasha al-Tunsi (1820–1890) had made his way to Ottoman Tunisia as a slave, where he rose through the ranks of the government of Ahmad Bey, the modernizing ruler of Tunisia. He soon was made responsible for diplomatic missions to the Ottoman Empire and the countries of Europe, bringing him into contact with Western ideals, as well as with the

Hayreddin Pasha al-Tunsi (1820–1890) had made his way to Ottoman Tunisia as a slave, where he rose through the ranks of the government of Ahmad Bey, the modernizing ruler of Tunisia. He soon was made responsible for diplomatic missions to the Ottoman Empire and the countries of Europe, bringing him into contact with Western ideals, as well as with the

Syrian scholar, publicist, writer, poet and physician

Syrian scholar, publicist, writer, poet and physician

In the religious field, Jamal al-Din al-Afghani (1839–1897) gave

In the religious field, Jamal al-Din al-Afghani (1839–1897) gave

A group of young writers formed ''The New School'', and in 1925 began publishing the weekly literary journal ''Al-Fajr'' (''The Dawn''), which would have a great impact on Arabic literature. The group was especially influenced by 19th-century Russian writers such as Dostoyevsky, Tolstoy and

A group of young writers formed ''The New School'', and in 1925 began publishing the weekly literary journal ''Al-Fajr'' (''The Dawn''), which would have a great impact on Arabic literature. The group was especially influenced by 19th-century Russian writers such as Dostoyevsky, Tolstoy and

Plain talk

– by Mursi Saad ed-Din, in ''

Tahtawi in Paris

– by Peter Gran, in ''

France as a Role Model

– by Barbara Winckler {{Syria topics Egyptian culture Islamic culture Islam and politics

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University ...

, notably in Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

, Lebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to the north and east and Israel to the south, while Cyprus lie ...

and Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

, during the second half of the 19th century and the early 20th century.

In traditional scholarship, the Nahda is seen as connected to the cultural shock brought on by Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader wh ...

's invasion of Egypt in 1798, and the reformist drive of subsequent rulers such as Muhammad Ali of Egypt

Muhammad Ali Pasha al-Mas'ud ibn Agha, also known as Muhammad Ali of Egypt and the Sudan ( sq, Mehmet Ali Pasha, ar, محمد علي باشا, ; ota, محمد علی پاشا المسعود بن آغا; ; 4 March 1769 – 2 August 1849), was ...

. However, more recent scholarship has shown the Nahda's cultural reform program to have been as "autogenetic" as it was Western-inspired, having been linked to the Tanzimat

The Tanzimat (; ota, تنظيمات, translit=Tanzimāt, lit=Reorganization, ''see'' nizām) was a period of reform in the Ottoman Empire that began with the Gülhane Hatt-ı Şerif in 1839 and ended with the First Constitutional Era in 187 ...

—the period of reform within the Ottoman Empire which brought a constitutional order to Ottoman politics and engendered a new political class—as well as the later Young Turk Revolution

The Young Turk Revolution (July 1908) was a constitutionalist revolution in the Ottoman Empire. The Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), an organization of the Young Turks movement, forced Sultan Abdul Hamid II to restore the Ottoman Consti ...

, allowing proliferation of the press and other publications and internal changes in political economy and communal reformations in Egypt and Syria and Lebanon. Stephen Sheehi, Foundations of Modern Arab Identity. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 200/ref> The renaissance itself started simultaneously in both Egypt and

Greater Syria

Syria ( Hieroglyphic Luwian: 𔒂𔒠 ''Sura/i''; gr, Συρία) or Sham ( ar, ٱلشَّام, ash-Shām) is the name of a historical region located east of the Mediterranean Sea in Western Asia, broadly synonymous with the Levant. Other ...

. Due to their differing backgrounds, the aspects that they focused on differed as well; with Egypt focused on the political aspects of the Islamic world while Greater Syria focused on the more cultural aspects. The concepts were not exclusive by region however, and this distinction blurred as the renaissance progressed.

Early figures

Rifa'a al-Tahtawi

Egyptian scholar Rifa'a al-Tahtawi (1801–1873) is widely seen as the pioneering figure of the Nahda. He was sent to Paris in 1826 by Muhammad Ali's government to study Western sciences and educational methods, although originally to serve asImam

Imam (; ar, إمام '; plural: ') is an Islamic leadership position. For Sunni Muslims, Imam is most commonly used as the title of a worship leader of a mosque. In this context, imams may lead Islamic worship services, lead prayers, serve ...

for the Egyptian cadets training at the Paris military academy. He came to hold a very positive view of French society, although not without criticisms. Learning French, he began translating important scientific and cultural works into Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walter ...

. He also witnessed the July Revolution

The French Revolution of 1830, also known as the July Revolution (french: révolution de Juillet), Second French Revolution, or ("Three Glorious ays), was a second French Revolution after French Revolution, the first in 1789. It led to ...

of 1830, against Charles X

Charles X (born Charles Philippe, Count of Artois; 9 October 1757 – 6 November 1836) was King of France from 16 September 1824 until 2 August 1830. An uncle of the uncrowned Louis XVII and younger brother to reigning kings Louis XVI and Lou ...

, but was careful in commenting on the matter in his reports to Muhammad Ali. His political views, originally influenced by the conservative Islamic teachings of al-Azhar university, changed on a number of matters, and he came to advocate parliamentarism

A parliamentary system, or parliamentarian democracy, is a system of democratic governance of a state (or subordinate entity) where the executive derives its democratic legitimacy from its ability to command the support ("confidence") of t ...

and women's education.

After five years in France, he then returned to Egypt to implement the philosophy of reform he had developed there, summarizing his views in the book ''Takhlis al-Ibriz fi Talkhis Bariz'' (sometimes translated as ''The Quintessence of Paris''), published in 1834. It is written in rhymed prose, and describes France and Europe from an Egyptian Muslim viewpoint. Tahtawi's suggestion was that the Egypt and the Muslim world

The terms Muslim world and Islamic world commonly refer to the Islamic community, which is also known as the Ummah. This consists of all those who adhere to the religious beliefs and laws of Islam or to societies in which Islam is practiced. I ...

had much to learn from Europe, and he generally embraced Western society, but also held that reforms should be adapted to the values of Islamic culture

Islamic culture and Muslim culture refer to cultural practices which are common to historically Islamic people. The early forms of Muslim culture, from the Rashidun Caliphate to the early Umayyad period and the early Abbasid period, were predom ...

. This brand of self-confident but open-minded modernism came to be the defining creed of the Nahda.

Ahmad Faris al-Shidyaq

Ahmad Faris al-Shidyaq (born 1805 or 1806 as Faris ibn Yusuf al-Shidyaq; died 1887) grew up in present-day Lebanon. A Maronite Christian by birth, he later lived in major cities of the Arabic-speaking world, where he had his career. He converted to Protestantism during the nearly two decades that he lived and worked in Cairo, present-day Egypt, from 1825 to 1848. He also spent time on the island of Malta. Participating in an Arabic translation of the Bible in Great Britain that was published in 1857, Faris lived and worked there for 7 years, becoming a British citizen. He next moved to Paris, France, for two years in the early 1850s, where he wrote and published some of his most important work.

Later in the 1850s Faris moved to Tunisia, where in 1860 he converted to Islam, taking the first name Ahmad. Moving to Istanbul later that year to work as a translator at the request of the Ottoman government, Faris also founded an Arabic-language newspaper. It was supported by the Ottomans, Egypt and Tunisia, publishing until the late 1880s.

Faris continued to promote Arabic language and culture, resisting the 19th-century "Turkization" pushed by the Ottomans based in present-day Turkey. Shidyaq is considered to be one of the founding fathers of modern Arabic literature; he wrote most of his fiction in his younger years.

Ahmad Faris al-Shidyaq (born 1805 or 1806 as Faris ibn Yusuf al-Shidyaq; died 1887) grew up in present-day Lebanon. A Maronite Christian by birth, he later lived in major cities of the Arabic-speaking world, where he had his career. He converted to Protestantism during the nearly two decades that he lived and worked in Cairo, present-day Egypt, from 1825 to 1848. He also spent time on the island of Malta. Participating in an Arabic translation of the Bible in Great Britain that was published in 1857, Faris lived and worked there for 7 years, becoming a British citizen. He next moved to Paris, France, for two years in the early 1850s, where he wrote and published some of his most important work.

Later in the 1850s Faris moved to Tunisia, where in 1860 he converted to Islam, taking the first name Ahmad. Moving to Istanbul later that year to work as a translator at the request of the Ottoman government, Faris also founded an Arabic-language newspaper. It was supported by the Ottomans, Egypt and Tunisia, publishing until the late 1880s.

Faris continued to promote Arabic language and culture, resisting the 19th-century "Turkization" pushed by the Ottomans based in present-day Turkey. Shidyaq is considered to be one of the founding fathers of modern Arabic literature; he wrote most of his fiction in his younger years.

Butrus al-Bustani

Butrus al-Bustani (1819–1893) was born to a Lebanese Maronite Christian family in the village of Dibbiye in the

Butrus al-Bustani (1819–1893) was born to a Lebanese Maronite Christian family in the village of Dibbiye in the Chouf

Chouf (also spelled Shouf, Shuf or Chuf, in ''Jabal ash-Shouf''; french: La Montagne du Chouf) is a historic region of Lebanon, as well as an administrative district in the governorate (muhafazat) of Mount Lebanon.

Geography

Located south-east ...

region, in January 1819. A polyglot, educator, and activist, Al-Bustani was a tour de force in the Nahda centered in mid-nineteenth century Beirut. Having been influenced by American missionaries, he converted to Protestantism, becoming a leader in the native Protestant church. Initially, he taught in the schools of the Protestant missionaries at 'Abey and was a central figure in the missionaries' translation of the Bible into Arabic. Despite his close ties to the Americans, Al-Bustani increasingly became independent, eventually breaking away from them.

After the bloody 1860 Druze–Maronite conflict

The 1860 civil conflict in Mount Lebanon and Damascus (also called the 1860 Syrian Civil War) was a civil conflict in Mount Lebanon during Ottoman rule in 1860–1861 fought mainly between the local Druze and Christians. Following decisive Druze v ...

and the increasing entrenchment of confessionalism, Al-Bustani founded the National School or Al-Madrasa Al-Wataniyya in 1863, on secular principles. This school employed the leading Nahda "pioneers" of Beirut and graduated a generation of Nahda thinkers. At the same time, he compiled and published several school textbooks and dictionaries; leading him to becoming known famously as the Master of the Arabic Renaissance.

In the social, national and political spheres, Al-Bustani founded associations with a view to forming a national elite and launched a series of appeals for unity in his magazine Nafir Suriya.

In the cultural/scientific fields, he published a fortnightly review and two daily newspapers. In addition, he began work, together with Drs. Eli Smith

Eli Smith (born September 13, 1801, in Northford, Connecticut, to Eli and Polly (Whitney) Smith, and died January 11, 1857, in Beirut, Lebanon) was an American Protestant missionary and scholar. He graduated from Yale College in 1821 and from And ...

and Cornelius Van Dyck of the American Mission, on a translation of the Bible into Arabic known as the Smith-Van Dyke translation.

His prolific output and groundbreaking work led to the creation of modern Arabic expository prose. While educated by Westerners, and a strong advocate of Western technology, he was a fierce secularist, playing a decisive role in formulating the principles of Syrian nationalism (not to be confused with Arab nationalism

Arab nationalism ( ar, القومية العربية, al-Qawmīya al-ʿArabīya) is a nationalist ideology that asserts the Arabs are a nation and promotes the unity of Arab people, celebrating the glories of Arab civilization, the language ...

).

Stephen Sheehi states that Al-Bustani's "importance does not lie in his prognosis of Arab culture or his national pride. Nor is his advocacy of discriminatingly adopting Western knowledge and technology to "awaken" the Arabs' inherent ability for cultural success,(najah), unique among his generation. Rather, his contribution lies in the act of elocution. That is, his writing articulates a specific formula for native progress that expresses a synthetic vision of the matrix of modernity within Ottoman Syria." Stephen Sheehi, "Butrus al-Bustani: Syria's Ideologue of the Age," in "The Origins of Syrian Nationhood: Histories, Pioneers, and Identity", edited by Adel Bishara. London: Routledge, 2011, pp. 57–78

Hayreddin Pasha

Hayreddin Pasha al-Tunsi (1820–1890) had made his way to Ottoman Tunisia as a slave, where he rose through the ranks of the government of Ahmad Bey, the modernizing ruler of Tunisia. He soon was made responsible for diplomatic missions to the Ottoman Empire and the countries of Europe, bringing him into contact with Western ideals, as well as with the

Hayreddin Pasha al-Tunsi (1820–1890) had made his way to Ottoman Tunisia as a slave, where he rose through the ranks of the government of Ahmad Bey, the modernizing ruler of Tunisia. He soon was made responsible for diplomatic missions to the Ottoman Empire and the countries of Europe, bringing him into contact with Western ideals, as well as with the Tanzimat

The Tanzimat (; ota, تنظيمات, translit=Tanzimāt, lit=Reorganization, ''see'' nizām) was a period of reform in the Ottoman Empire that began with the Gülhane Hatt-ı Şerif in 1839 and ended with the First Constitutional Era in 187 ...

reforms of the Ottoman Empire. He served as Prime Minister of Tunisia from 1859 until 1882. In this period, he was a major force of modernization in Tunisia.

In numerous writings, he envisioned a seamless blending of Islamic tradition with Western modernization. Basing his beliefs on European Enlightenment writings and Arabic political thought, his main concern was with preserving the autonomy of the Tunisian people in particular, and Muslim peoples in general. In this quest, he ended up bringing forth what amounted to the earliest example of Muslim constitutionalism. His modernizing theories have had an enormous influence on Tunisian and Ottoman thought.

Francis Marrash

Syrian scholar, publicist, writer, poet and physician

Syrian scholar, publicist, writer, poet and physician Francis Marrash

Francis bin Fathallah bin Nasrallah Marrash (Arabic: , ; 1835,. 1836,. or 1837 – 1873 or 1874), also known as Francis al-Marrash or Francis Marrash al-Halabi, was a Syrian scholar, publicist, writer and poet of the Nahda or the Arab Renaissance ...

(born between 1835 and 1837; died 1873 or 1874) had traveled throughout Western Asia and France in his youth. He expressed ideas of political and social reforms in ''Ghabat al-haqq'' (first published 1865), highlighting the need of the Arabs for two things above all: modern schools and patriotism "free from religious considerations". In 1870, when distinguishing the notion of fatherland from that of nation and applying the latter to Greater Syria

Syria ( Hieroglyphic Luwian: 𔒂𔒠 ''Sura/i''; gr, Συρία) or Sham ( ar, ٱلشَّام, ash-Shām) is the name of a historical region located east of the Mediterranean Sea in Western Asia, broadly synonymous with the Levant. Other ...

, Marrash pointed to the role played by language, among other factors, in counterbalancing religious and sectarian differences, and thus, in defining national identity.

Marrash has been considered the first truly cosmopolitan Arab intellectual and writer of modern times, having adhered to and defended the principles of the French Revolution in his own works, implicitly criticizing Ottoman rule in Western Asia and North Africa.

He also tried to introduce "a revolution in diction, themes, metaphor and imagery in modern Arabic poetry". His use of conventional diction for new ideas is considered to have marked the rise of a new stage in Arabic poetry which was carried on by the Mahjar

The Mahjar ( ar, المهجر, translit=al-mahjar, one of its more literal meanings being "the Arab diaspora") was a literary movement started by Arabic-speaking writers who had emigrated to America from Ottoman-ruled Lebanon, Syria and Palestine ...

is.

Politics and society

Proponents of the Nahda typically supported reforms. While al-Bustani and al-Shidyaq "advocated reform without revolution", the "trend of thought advocated by Francis Marrash ..andAdib Ishaq

Adib Ishaq ( ar, اديب اسحق, ; 21 January 1856 – 12 June 1885) was an important Syrian literary figure of nineteenth-century Arab Nahda.

Born in Damascus (then a city of the Ottoman Empire, and the present-day capital of Syria), he was e ...

" (1856–1884) was "radical and revolutionary.

In 1876, the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University ...

promulgated a constitution, as the crowning accomplishment of the Tanzimat

The Tanzimat (; ota, تنظيمات, translit=Tanzimāt, lit=Reorganization, ''see'' nizām) was a period of reform in the Ottoman Empire that began with the Gülhane Hatt-ı Şerif in 1839 and ended with the First Constitutional Era in 187 ...

reforms (1839–1876) and inaugurating the Empire's First Constitutional Era. It was inspired by European methods of government and designed to bring the Empire back on level with the Western powers. The constitution was opposed by the Sultan

Sultan (; ar, سلطان ', ) is a position with several historical meanings. Originally, it was an Arabic abstract noun meaning "strength", "authority", "rulership", derived from the verbal noun ', meaning "authority" or "power". Later, it c ...

, whose powers it checked, but had vast symbolic and political importance.

The introduction of parliamentarism

A parliamentary system, or parliamentarian democracy, is a system of democratic governance of a state (or subordinate entity) where the executive derives its democratic legitimacy from its ability to command the support ("confidence") of t ...

also created a political class in the Ottoman-controlled provinces, from which later emerged a liberal nationalist elite that would spearhead the several nationalist movements, in particular Egyptian nationalism

Egyptian nationalism is based on Egyptians and Egyptian culture. Egyptian nationalism has typically been a civic nationalism that has emphasized the unity of Egyptians regardless of their ethnicity or religion. Egyptian nationalism first manifes ...

. Egyptian nationalism was non-Arab, emphasising ethnic Egyptian identity and history in response to European colonialism and the Turkish occupation of Egypt. This was paralleled by the rise of the Young Turks in the central Ottoman provinces and administration. The resentment towards Turk

Turk or Turks may refer to:

Communities and ethnic groups

* Turkic peoples, a collection of ethnic groups who speak Turkic languages

* Turkish people, or the Turks, a Turkic ethnic group and nation

* Turkish citizen, a citizen of the Republic o ...

ish rule fused with protests against the Sultan's autocracy, and the largely secular concepts of Arab nationalism

Arab nationalism ( ar, القومية العربية, al-Qawmīya al-ʿArabīya) is a nationalist ideology that asserts the Arabs are a nation and promotes the unity of Arab people, celebrating the glories of Arab civilization, the language ...

rose as a cultural response to the Ottoman Caliphate

A caliphate or khilāfah ( ar, خِلَافَة, ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with the title of caliph (; ar, خَلِيفَة , ), a person considered a political-religious successor to th ...

s claims of religious legitimacy. Various Arab nationalist secret societies rose in the years prior to World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, such as Al-fatat and the military based al-Ahd.

This was complemented by the rise of other national movements, including Syrian nationalism, which like Egyptian nationalism was in some of its manifestations essentially non-Arabist and connected to the concept of Greater Syria

Syria ( Hieroglyphic Luwian: 𔒂𔒠 ''Sura/i''; gr, Συρία) or Sham ( ar, ٱلشَّام, ash-Shām) is the name of a historical region located east of the Mediterranean Sea in Western Asia, broadly synonymous with the Levant. Other ...

. The main other example of the late ''al-Nahda'' era is the emerging Palestinian nationalism, which was set apart from Syrian nationalism by Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

immigration to Mandatory Palestine

Mandatory Palestine ( ar, فلسطين الانتدابية '; he, פָּלֶשְׂתִּינָה (א״י) ', where "E.Y." indicates ''’Eretz Yiśrā’ēl'', the Land of Israel) was a geopolitical entity established between 1920 and 1948 ...

and the resulting sense of Palestinian particularism.

Women's rights

Al-Shidyaq defendedwomen's rights

Women's rights are the rights and entitlements claimed for women and girls worldwide. They formed the basis for the women's rights movement in the 19th century and the feminist movements during the 20th and 21st centuries. In some countri ...

in ''Leg Over Leg

''Leg Over Leg'' is a book by Ahmad Faris Shidyaq, considered one of the founders of modern Arabic literature. Detailing the life of 'the Fariyaq', the alter ego of the author, offering commentary on intellectual and social issues, it is described ...

'', which was published as early as 1855 in Paris. Esther Moyal, a Lebanese Jewish author, wrote extensively on women's rights in her magazine ''The Family'' throughout the 1890s.

Religion

In the religious field, Jamal al-Din al-Afghani (1839–1897) gave

In the religious field, Jamal al-Din al-Afghani (1839–1897) gave Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God (or '' Allah'') as it was revealed to Muhammad, the ...

a modernist reinterpretation and fused adherence to the faith with an anti-colonial doctrine that preached Pan-Islamic

Pan-Islamism ( ar, الوحدة الإسلامية) is a political movement advocating the unity of Muslims under one Islamic country or state – often a caliphate – or an international organization with Islamic principles. Pan-Islamism was ...

solidarity in the face of European pressures. He also favored the replacement of authoritarian

Authoritarianism is a political system characterized by the rejection of political plurality, the use of strong central power to preserve the political ''status quo'', and reductions in the rule of law, separation of powers, and democratic vot ...

monarchies with representative rule, and denounced what he perceived as the dogmatism, stagnation and corruption of the Islam of his age. He claimed that tradition (''taqlid

''Taqlid'' (Arabic تَقْليد ''taqlīd'') is an Islamic term denoting the conformity of one person to the teaching of another. The person who performs ''taqlid'' is termed ''muqallid''. The definite meaning of the term varies depending on con ...

'', تقليد) had stifled Islamic debate and repressed the correct practices of the faith. Al-Afghani's case for a redefinition of old interpretations of Islam, and his bold attacks on traditional religion, would become vastly influential with the fall of the Caliphate

A caliphate or khilāfah ( ar, خِلَافَة, ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with the title of caliph (; ar, خَلِيفَة , ), a person considered a political-religious successor to th ...

in 1924. This created a void in the religious doctrine and social structure of Islamic communities which had been only temporarily reinstated by Abdul Hamid II

Abdülhamid or Abdul Hamid II ( ota, عبد الحميد ثانی, Abd ül-Hamid-i Sani; tr, II. Abdülhamid; 21 September 1842 10 February 1918) was the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 31 August 1876 to 27 April 1909, and the last sultan to ...

in an effort to bolster universal Muslim support, suddenly vanished. It forced Muslims to look for new interpretations of the faith, and to re-examine widely held dogma; exactly what al-Afghani had urged them to do decades earlier.

Al-Afghani influenced many, but greatest among his followers is undoubtedly his student Muhammad Abduh

; "The Theology of Unity")

, alma_mater = Al-Azhar University

, office1 = Grand Mufti of Egypt

, term1 = 1899 – 1905

, Sufi_order = Shadhiliyya

, disciple_of =

, awards =

, in ...

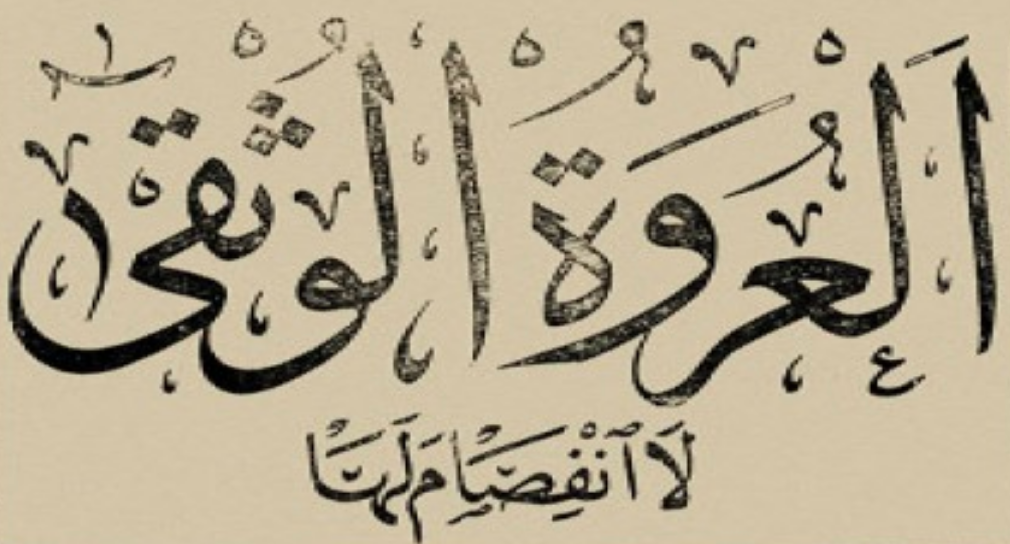

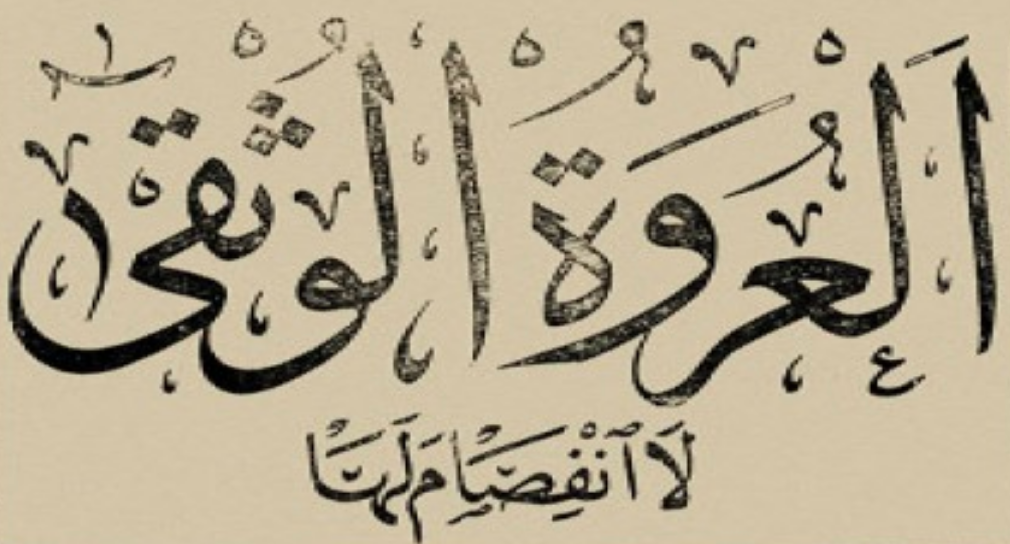

(1849–1905), with whom he started a short-lived Islamic revolutionary journal, ''Al-Urwah al-Wuthqa

''Al-Urwah al-Wuthqa'' (, ) was an Islamic revolutionary journal founded by Muhammad Abduh and Jamāl al-Dīn al-Afghānī. Despite only running from 13 March 1884 to October 1884, it was one of the first and most important publications of the ...

'', and whose teachings would play a similarly important role in the reform of the practice of Islam. Like al-Afghani, Abduh accused traditionalist Islamic authorities of moral and intellectual corruption, and of imposing a doctrinaire form of Islam on the ummah

' (; ar, أمة ) is an Arabic word meaning "community". It is distinguished from ' ( ), which means a nation with common ancestry or geography. Thus, it can be said to be a supra-national community with a common history.

It is a synonym for ' ...

, that had hindered correct applications of the faith. He therefore advocated that Muslims should return to the "true" Islam practiced by the ancient Caliphs, which he held had been both rational and divinely inspired. Applying the original message of the Prophet

In religion, a prophet or prophetess is an individual who is regarded as being in contact with a divine being and is said to speak on behalf of that being, serving as an intermediary with humanity by delivering messages or teachings from the ...

Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the mon ...

with no interference of tradition or the faulty interpretations of his followers, would automatically create the just society ordained by God in the Qur'an

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , si ...

, and so empower the Muslim world to stand against colonization and injustices.

Among the students of Abduh were Syrian Islamic scholar and reformer Rashid Rida

Muḥammad Rashīd ibn ʿAlī Riḍā ibn Muḥammad Shams al-Dīn ibn Muḥammad Bahāʾ al-Dīn ibn Munlā ʿAlī Khalīfa (23 September 1865 or 18 October 1865 – 22 August 1935 CE/ 1282 - 1354 AH), widely known as Sayyid Rashid Rida ( ar, � ...

(1865–1935), who continued his legacy, and expanded on the concept of just Islamic government. His theses on how an Islamic state

An Islamic state is a state that has a form of government based on Islamic law (sharia). As a term, it has been used to describe various historical polities and theories of governance in the Islamic world. As a translation of the Arabic ter ...

should be organized remain influential among modern-day Islamists such as the Muslim Brotherhood

The Society of the Muslim Brothers ( ar, جماعة الإخوان المسلمين'' ''), better known as the Muslim Brotherhood ( '), is a transnational Sunni Islamist organization founded in Egypt by Islamic studies, Islamic scholar and scho ...

.

Shia Islam

Shi'a

Shīʿa Islam or Shīʿīsm is the second-largest Islamic schools and branches, branch of Islam. It holds that the Prophets and messengers in Islam, Islamic prophet Muhammad in Islam, Muhammad designated Ali, ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib as his S ...

scholars contributed to the renaissance movement, such as the linguist shaykh Ahmad Rida, the historian Muhammad Jaber Al Safa and Suleiman Daher. Important political reforms took place simultaneously also in Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

and Shi'a religious beliefs saw important developments with the systematization of a religious hierarchy

A hierarchy (from Greek: , from , 'president of sacred rites') is an arrangement of items (objects, names, values, categories, etc.) that are represented as being "above", "below", or "at the same level as" one another. Hierarchy is an important ...

. A wave of political reform followed, with the constitutional movement in Iran to some extent paralleling the Egyptian Nahda reforms.

Science

Many student missions from Egypt went to Europe in the early 19th century to study arts and sciences at European universities and acquire technical skills. Arabic-language magazines began to publish articles of scientific vulgarization.Modern literature

Through the 19th century and early 20th centuries, a number of new developments in Arabic literature started to emerge, initially sticking closely to the classical forms, but addressing modern themes and the challenges faced by the Arab world in the modern era. Francis Marrash was influential in introducing French romanticism in the Arab world, especially through his use of poetic prose and prose poetry, of which his writings were the first examples in modern Arabic literature, according to Salma Khadra Jayyusi and Shmuel Moreh. In Egypt, Ahmad Shawqi (1868–1932), among others, began to explore the limits of the classical qasida, although he remained a clearly neo-classical poet. After him, others, includingHafez Ibrahim

Hafez Ibrahim ( ar, حافظ إبراهيم, ; 1871–1932) was a well known Egyptian poet of the early 20th century. He was dubbed the "Poet of the Nile", and sometimes the "Poet of the People", for his political commitment to the poor. His p ...

(1871–1932) began to use poetry to explore themes of anticolonialism

Decolonization or decolonisation is the undoing of colonialism, the latter being the process whereby imperial nations establish and dominate foreign territories, often overseas. Some scholars of decolonization focus especially on independence ...

as well as the classical concepts. In 1914, Muhammad Husayn Haykal (1888–1956) published '' Zaynab'', often considered the first modern Egyptian novel. This novel started a movement of modernizing Arabic fiction.

A group of young writers formed ''The New School'', and in 1925 began publishing the weekly literary journal ''Al-Fajr'' (''The Dawn''), which would have a great impact on Arabic literature. The group was especially influenced by 19th-century Russian writers such as Dostoyevsky, Tolstoy and

A group of young writers formed ''The New School'', and in 1925 began publishing the weekly literary journal ''Al-Fajr'' (''The Dawn''), which would have a great impact on Arabic literature. The group was especially influenced by 19th-century Russian writers such as Dostoyevsky, Tolstoy and Gogol

Nikolai Vasilyevich Gogol; uk, link=no, Мико́ла Васи́льович Го́голь, translit=Mykola Vasyliovych Hohol; (russian: Яновский; uk, Яновський, translit=Yanovskyi) ( – ) was a Russian novelist, ...

. At about the same time, the Mahjar

The Mahjar ( ar, المهجر, translit=al-mahjar, one of its more literal meanings being "the Arab diaspora") was a literary movement started by Arabic-speaking writers who had emigrated to America from Ottoman-ruled Lebanon, Syria and Palestine ...

i poets further contributed from America to the development of the forms available to Arab poets. The most famous of these, Kahlil Gibran (1883–1931), challenged political and religious institutions with his writing, and was an active member of the Pen League in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

from 1920 until his death. Some of the Mahjaris later returned to Lebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to the north and east and Israel to the south, while Cyprus lie ...

, such as Mikhail Naimy (1898–1989).

Jurji Zaydan (1861–1914) developed the genre of the Arabic historical novel. May Ziadeh (1886–1941) was also a key figure in the early 20th century Arabic literary scene.

Aleppine writer Qustaki al-Himsi (1858–1941) is credited with having founded modern Arabic literary criticism

Literary criticism (or literary studies) is the study, evaluation, and interpretation of literature. Modern literary criticism is often influenced by literary theory, which is the philosophical discussion of literature's goals and methods. ...

, with one of his works, ''The researcher's source in the science of criticism''.

Dissemination of ideas

Newspapers and journals

The firstprinting press

A printing press is a mechanical device for applying pressure to an inked surface resting upon a print medium (such as paper or cloth), thereby transferring the ink. It marked a dramatic improvement on earlier printing methods in which the ...

in the Middle East was in the Monastery of Saint Anthony of Qozhaya in Lebanon and dates back to 1610. It printed books in Syriac and Garshuni Garshuni or Karshuni ( Syriac alphabet: , Arabic alphabet: ) are Arabic writings using the Syriac alphabet. The word "Garshuni", derived from the word "grasha" which literally translates as "pulling", was used by George Kiraz to coin the term "gar ...

(Arabic using the Syriac alphabet). The first printing press with Arabic letters was built in St John's monastery in Khinshara, Lebanon by "Al-Shamas Abdullah Zakher" in 1734. The printing press operated from 1734 till 1899.

In 1821, Muhammad Ali of Egypt

Muhammad Ali Pasha al-Mas'ud ibn Agha, also known as Muhammad Ali of Egypt and the Sudan ( sq, Mehmet Ali Pasha, ar, محمد علي باشا, ; ota, محمد علی پاشا المسعود بن آغا; ; 4 March 1769 – 2 August 1849), was ...

brought the first printing press to Egypt. Modern printing techniques spread rapidly and gave birth to a modern Egyptian press, which brought the reformist trends of the Nahda into contact with the emerging Egyptian middle class of clerks and tradesmen.

In 1855, Rizqallah Hassun (1825–1880) founded the first newspaper written solely in Arabic, ''Mir'at al-ahwal''. The Egyptian newspaper ''Al-Ahram

''Al-Ahram'' ( ar, الأهرام; ''The Pyramids''), founded on 5 August 1875, is the most widely circulating Egyptian daily newspaper, and the second oldest after '' al-Waqa'i`al-Masriya'' (''The Egyptian Events'', founded 1828). It is majori ...

'' founded by Saleem Takla

Saleem Takla ( ar, سليم تقلا, also spelled Selim Taqla; 1849 – August 8, 1892) was a Lebanese-Ottoman journalist who founded of ''Al-Ahram'' newspaper with his brother Beshara Takla.

Early life and education

Saleem Takla was born in Kf ...

dates from 1875, and between 1870 and 1900, Beirut alone saw the founding of about 40 new periodicals and 15 newspapers.

Muhammad Abduh

; "The Theology of Unity")

, alma_mater = Al-Azhar University

, office1 = Grand Mufti of Egypt

, term1 = 1899 – 1905

, Sufi_order = Shadhiliyya

, disciple_of =

, awards =

, in ...

and Jamāl al-Dīn al-Afghānī's weekly pan-Islamic

Pan-Islamism ( ar, الوحدة الإسلامية) is a political movement advocating the unity of Muslims under one Islamic country or state – often a caliphate – or an international organization with Islamic principles. Pan-Islamism was ...

anti-colonial revolutionary literary magazine ''Al-Urwah al-Wuthqa

''Al-Urwah al-Wuthqa'' (, ) was an Islamic revolutionary journal founded by Muhammad Abduh and Jamāl al-Dīn al-Afghānī. Despite only running from 13 March 1884 to October 1884, it was one of the first and most important publications of the ...

'' (''The Firmest Bond'')—though it only ran from March to October of 1884 and was banned by British authorities in Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

and India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

—was circulated widely from Morocco to India and it's considered one of the first and most important publications of the Nahda.

Encyclopedias and dictionaries

The efforts at translating European and American literature led to the modernization of theArabic language

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walter ...

. Many scientific and academic terms, as well as words for modern inventions, were incorporated in modern Arabic vocabulary, and new words were coined in accordance with the Arabic root system to cover for others. The development of a modern press ensured that Classical Arabic

Classical Arabic ( ar, links=no, ٱلْعَرَبِيَّةُ ٱلْفُصْحَىٰ, al-ʿarabīyah al-fuṣḥā) or Quranic Arabic is the standardized literary form of Arabic used from the 7th century and throughout the Middle Ages, most notab ...

ceased to be used and was replaced entirely by Modern Standard Arabic

Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) or Modern Written Arabic (MWA), terms used mostly by linguists, is the variety of standardized, literary Arabic that developed in the Arab world in the late 19th and early 20th centuries; occasionally, it also re ...

, which is used still today all over the Arab world

The Arab world ( ar, اَلْعَالَمُ الْعَرَبِيُّ '), formally the Arab homeland ( '), also known as the Arab nation ( '), the Arabsphere, or the Arab states, refers to a vast group of countries, mainly located in Western A ...

.

In the late 19th century, Butrus al-Bustani

Butrus al-Bustani ( ar, بطرس البستاني, ; 1819–1883) was a writer and scholar from present day Lebanon. He was a major figure in the Nahda, which began in Egypt in the late 19th century and spread to the Middle East.

He is cons ...

created the first modern Arabic encyclopedia, drawing both on medieval Arab scholars and Western methods of lexicography

Lexicography is the study of lexicons, and is divided into two separate academic disciplines. It is the art of compiling dictionaries.

* Practical lexicography is the art or craft of compiling, writing and editing dictionaries.

* Theoreti ...

. Ahmad Rida (1872–1953) created the first modern dictionary of Arabic, ''Matn al-Lugha ''Matn al-Lugha'' (; "Corpus of the Language") was one of earliest modern monolingual dictionaries of the Arabic language, written by Lebanese linguist Sheikh Ahmed Rida, an important figure of the Arab literary renaissance. The five-volume dictio ...

''.

Literary salons

Different salons appeared.Maryana Marrash

Maryana bint Fathallah bin Nasrallah Marrash (Arabic: , ; 1848–1919), also known as Maryana al-Marrash or Maryana Marrash al-Halabiyah, was a Syrian writer and poet of the Nahda or the Arab Renaissance. She revived the tradition of liter ...

was the first Arab woman in the nineteenth century to revive the tradition of the literary salon

Salon may refer to:

Common meanings

* Beauty salon, a venue for cosmetic treatments

* French term for a drawing room, an architectural space in a home

* Salon (gathering), a meeting for learning or enjoyment

Arts and entertainment

* Salon ( ...

in the Arab world, with the salon she ran in her family home in Aleppo

)), is an adjective which means "white-colored mixed with black".

, motto =

, image_map =

, mapsize =

, map_caption =

, image_map1 =

...

. The first salon in Cairo was Princess Nazli Fadil's.

See also

*Mahjar

The Mahjar ( ar, المهجر, translit=al-mahjar, one of its more literal meanings being "the Arab diaspora") was a literary movement started by Arabic-speaking writers who had emigrated to America from Ottoman-ruled Lebanon, Syria and Palestine ...

Notes

References

Sources

* * * * * * * *Further reading

* Albert Hourani, ''A History of the Arab Peoples'', New York: Warner Books, 1991. () *Ira M. Lapidus

Ira M. Lapidus is an Emeritus Professor of Middle Eastern and Islamic History at The University of California at Berkeley. He is the author of ''A History of Islamic Societies'', and ''Contemporary Islamic Movements in Historical Perspective'', ...

, ''A History of Islamic Societies'', 2nd Ed. Cambridge University Press

Cambridge University Press is the university press of the University of Cambridge. Granted letters patent by King Henry VIII in 1534, it is the oldest university press in the world. It is also the King's Printer.

Cambridge University Pr ...

, 2002.

* Karen Armstrong, ''The Battle for God

''The Battle for God: Fundamentalism in Judaism, Christianity and Islam'' is a book by author Karen Armstrong published in 2000 by Knopf/HarperCollins which the ''New York Times'' described as "one of the most penetrating, readable, and prescient ...

'', New York City, 2000.

* Samir Kassir, ''Considérations sur le malheur arabe'', Paris, 2004.

* Stephen Sheehi, '' Foundations of Modern Arab Identity'', University Press of Florida, 2004.

* Fruma Zachs and Sharon Halevi, ''From Difa Al-Nisa to Masalat Al-Nisa in greater Syria: Readers and writers debate women and their rights, 1858–1900.'' International Journal of Middle East Studies 41, no. 4 (2009): 615 – 633.

External links

Plain talk

– by Mursi Saad ed-Din, in ''

Al-Ahram

''Al-Ahram'' ( ar, الأهرام; ''The Pyramids''), founded on 5 August 1875, is the most widely circulating Egyptian daily newspaper, and the second oldest after '' al-Waqa'i`al-Masriya'' (''The Egyptian Events'', founded 1828). It is majori ...

'' Weekly.

Tahtawi in Paris

– by Peter Gran, in ''

Al-Ahram

''Al-Ahram'' ( ar, الأهرام; ''The Pyramids''), founded on 5 August 1875, is the most widely circulating Egyptian daily newspaper, and the second oldest after '' al-Waqa'i`al-Masriya'' (''The Egyptian Events'', founded 1828). It is majori ...

'' Weekly.

France as a Role Model

– by Barbara Winckler {{Syria topics Egyptian culture Islamic culture Islam and politics