Nuri Es-Said on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Nuri Pasha al-Said CH (December 1888 – 15 July 1958) ( ar, نوري السعيد) was an Iraqi politician during the British mandate in Iraq and the

He was born in

He was born in

Hashemite Kingdom of Iraq

The Hashemite Kingdom of Iraq ( ar, المملكة العراقية الهاشمية, translit=al-Mamlakah al-ʿIrāqiyyah ʾal-Hāshimyyah) was a state located in the Middle East from 1932 to 1958.

It was founded on 23 August 1921 as the Kingdo ...

. He held various key cabinet positions and served eight terms as the prime minister of Iraq

The prime minister of Iraq is the head of government of Iraq. On 27 October 2022, Mohammed Shia' Al Sudani became the incumbent prime minister.

History

The prime minister was originally an appointed office, subsidiary to the head of state, a ...

.

From his first appointment as prime minister under the British mandate in 1930, Nuri was a major political figure in Iraq under the monarchy. During his many terms in office, he was involved in some of the key policy decisions that shaped the modern Iraqi state. In 1930, during his first term, he signed the Anglo-Iraqi Treaty

The Anglo-Iraqi Treaty of October 1922 was an agreement signed between the British and Iraqi governments. The treaty was designed to allow for Iraqi self-government while giving the British control of Iraq's foreign policy. It was intended to co ...

, which, as a step toward greater independence, granted Britain the unlimited right to station its armed forces in and transit military units through Iraq and also gave legitimacy to British control of the country's oil industry.

The treaty nominally reduced British involvement in Iraq's internal affairs but only to the extent that Iraq did not conflict with British economic or military interests. The agreement led the way to nominal independence, as the Mandate ended in 1932. Throughout most of his career, Nuri was a supporter of a continued and extensive British role within Iraq, which was against the popular mood.

Nuri was a controversial figure with many enemies and had to flee Iraq twice after coups. At the overthrow of the monarchy in 1958, he was very unpopular. His policies, regarded as pro-British, were believed to have failed in adapting to the country's changed social circumstances. Poverty and social injustice were widespread, and Nuri had become a symbol of a regime that failed to address the issues, choosing a course of repression instead, to protect the interests of the well off.

On 15 July 1958, the day after the revolution, he attempted to flee the country but was captured and killed.

Biography

Early career

He was born in

He was born in Baghdad

Baghdad (; ar, بَغْدَاد , ) is the capital of Iraq and the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. It is located on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon and the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesiphon ...

to middle class Sunni Muslim

Sunni Islam () is the largest branch of Islam, followed by 85–90% of the world's Muslims. Its name comes from the word ''Sunnah'', referring to the tradition of Muhammad. The differences between Sunni and Shia Muslims arose from a disagree ...

family of North Caucasian origin. His father was a minor government accountant. Nuri graduated from a military college in Istanbul

Istanbul ( , ; tr, İstanbul ), formerly known as Constantinople ( grc-gre, Κωνσταντινούπολις; la, Constantinopolis), is the List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, largest city in Turkey, serving as the country's economic, ...

in 1906, trained at the staff college there in 1911 as an officer in the military of the Ottoman Empire

The military of the Ottoman Empire ( tr, Osmanlı İmparatorluğu'nun silahlı kuvvetleri) was the armed forces of the Ottoman Empire.

Army

The military of the Ottoman Empire can be divided in five main periods. The foundation era covers the ...

and was among the officers dispatched to Ottoman Tripolitania

The coastal region of what is today Libya was ruled by the Ottoman Empire from 1551 to 1912. First, from 1551 to 1864, as the Eyalet of Tripolitania ( ota, ایالت طرابلس غرب ''Eyālet-i Trâblus Gârb'') or ''Bey and Subjects of Tri ...

in 1912 to resist the Italian occupation of that province. He was an elusive guerrilla leader, with Jaafar Al-Askari

Ja'far Pasha al-Askari ( ar, جعفر العسكري; 15 September 1885 – 29 October 1936) served twice as prime minister of Iraq: from 22 November 1923 to 3 August 1924; and from 21 November 1926 to 31 December 1927.

Al-Askari served in th ...

, against the British in Libya in 1915.

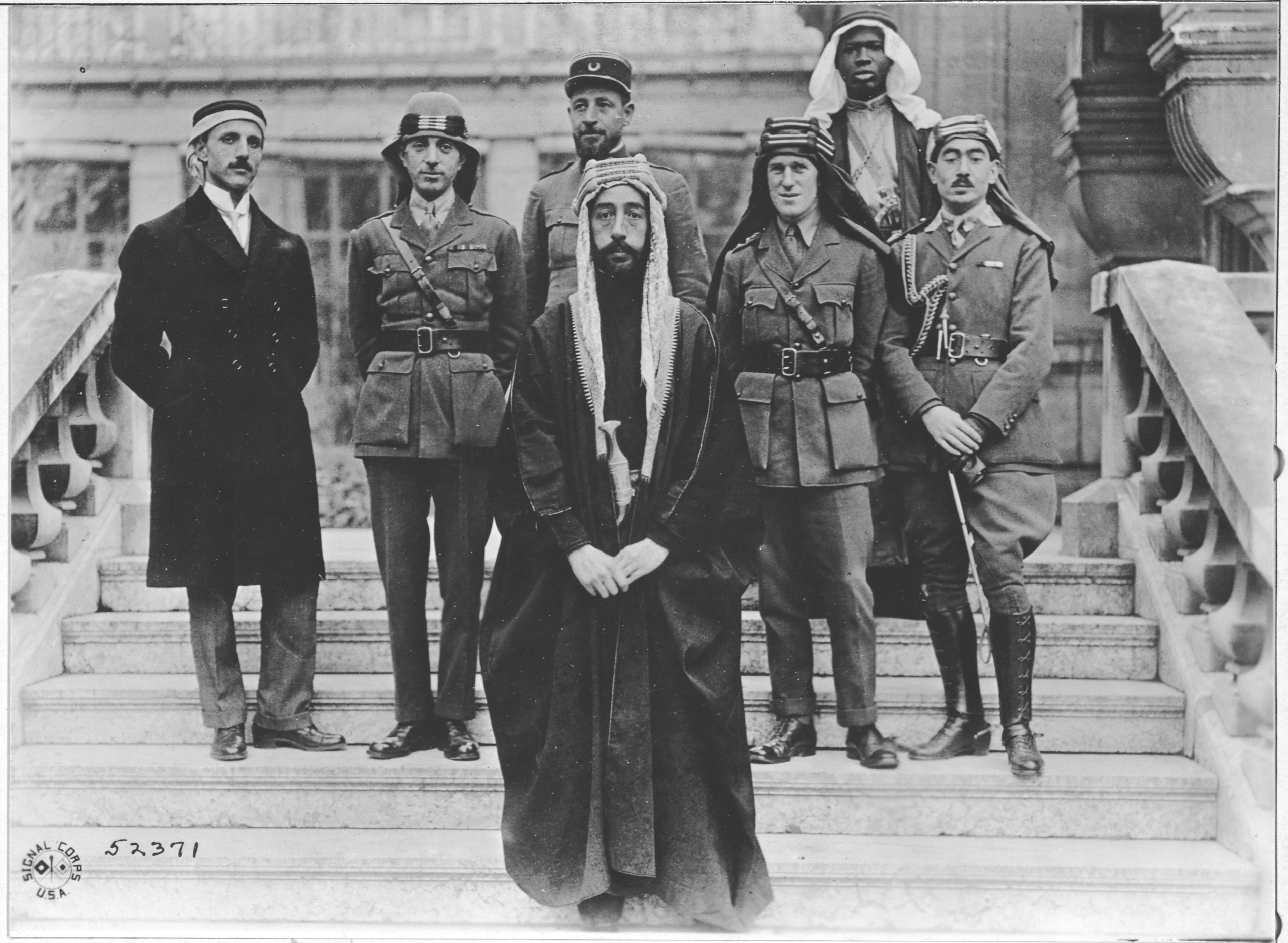

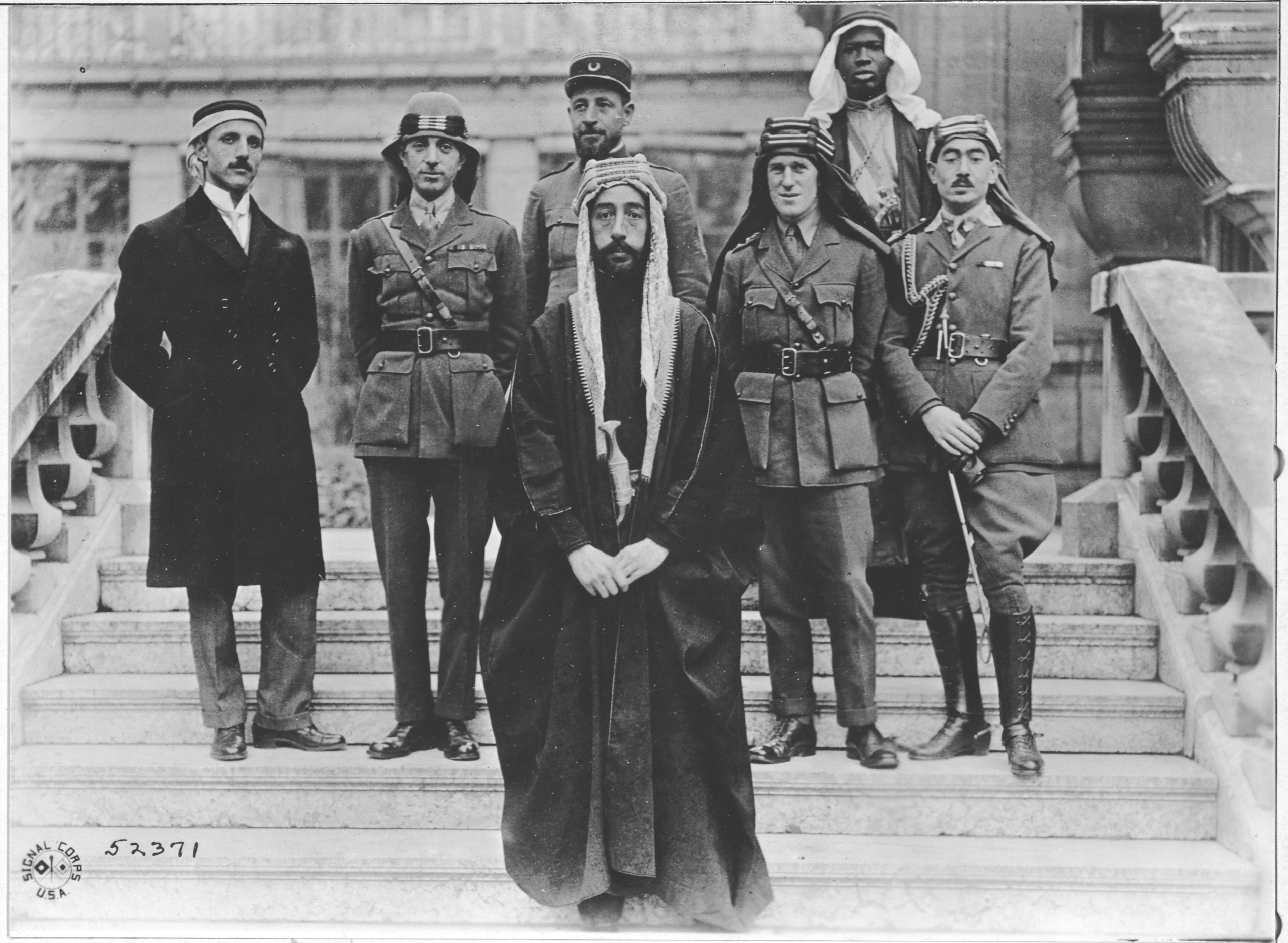

After being captured and held prisoner by the British in Egypt, he and Jaafar were converted to the Arab nationalist

Arab nationalism ( ar, القومية العربية, al-Qawmīya al-ʿArabīya) is a nationalist ideology that asserts the Arabs are a nation and promotes the unity of Arab people, celebrating the glories of Arab civilization, the language an ...

cause and fought in the Arab Revolt

The Arab Revolt ( ar, الثورة العربية, ) or the Great Arab Revolt ( ar, الثورة العربية الكبرى, ) was a military uprising of Arab forces against the Ottoman Empire in the Middle Eastern theatre of World War I. On t ...

under Emir Faisal ibn Hussain of the Hejaz

The Hejaz (, also ; ar, ٱلْحِجَاز, al-Ḥijāz, lit=the Barrier, ) is a region in the west of Saudi Arabia. It includes the cities of Mecca, Medina, Jeddah, Tabuk, Yanbu, Taif, and Baljurashi. It is also known as the "Western Provin ...

, who would later reign briefly as King of Arab Syria before he was installed as King of Iraq

The king of Iraq ( ar, ملك العراق, ''Malik al-‘Irāq'') was Iraq's head of state and monarch from 1921 to 1958. He served as the head of the Iraqi monarchy—the Hashemite dynasty. The king was addressed as His Majesty (صاحب ال� ...

. On one operation Nuri rode with T. E. Lawrence

Thomas Edward Lawrence (16 August 1888 – 19 May 1935) was a British archaeologist, army officer, diplomat, and writer who became renowned for his role in the Arab Revolt (1916–1918) and the Sinai and Palestine Campaign (1915–1918 ...

and his British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

driver as crew of a Rolls-Royce Armoured Car

The Rolls-Royce Armoured Car was a British Armored car (military), armoured car developed in 1914 and used during the World War I, First World War, Irish Civil War, the inter-war period in Imperial Air Control in Transjordan, Palestine and Mesopot ...

.

Like other Iraqi officers who had served under Faisal, he went on to emerge as part of a new political elite.

Initial positions under Iraqi monarchy

Nuri headed the Arab troops who tookDamascus

)), is an adjective which means "spacious".

, motto =

, image_flag = Flag of Damascus.svg

, image_seal = Emblem of Damascus.svg

, seal_type = Seal

, map_caption =

, ...

for Faisal in the wake of the retreating Turkish forces in 1918. When Faisal was deposed by the French in 1920, Nuri followed the exiled monarch to Iraq, and in 1922 became first director general of the Iraqi police force. He used the position to fill the force with his placemen, a tactic that he would repeat in subsequent positions; that was a basis of his considerable political clout in later years.

He was a trusted ally of Faisal who, in 1924, appointed him deputy commander in chief of the army so as to ensure the loyalty of the troops to the regime. Once again, Nuri used the position to build up his own power base. During the 1920s, he supported the king's policy to build up the nascent state's armed forces, based on the loyalty of Sharifian officers, the former Ottoman soldiers who formed the backbone of the regime.

Prime Minister for first time

Faisal first proposed Nuri as prime minister in 1929, but it was only in 1930 that the British were persuaded to forgo their objections. As in previous appointments, Nuri was quick to appoint supporters to key government positions, but that only weakened the king's own base among the civil service, and the formerly close relationship between the two men soured. Among Nuri's first acts as prime minister was the signing of theAnglo-Iraqi Treaty of 1930

The Anglo-Iraqi Treaty of 1930 was a treaty of alliance between the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and the British-Mandate-controlled administration of the Hashemite Kingdom of Iraq. The treaty was between the governments ...

, an unpopular move since it essentially confirmed Britain's mandatory powers and gave them permanent military prerogatives in the country even after full independence was achieved. In 1932, he presented the Iraqi case for greater independence to the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

.

In October 1932, Faisal dismissed Nuri as Prime Minister and replaced him with Naji Shawkat

Muhammad Naji Shawkat Bey ( ar, ناجي شوكت) (May 26, 1891 – May 11, 1980) was an Iraqi politician who served as the prime minister of Iraq under King Faisal I.

Early life

Muhammad Naji Shawkat was born to an Arabized family of Georg ...

, which curbed Nuri's influence somewhat; after the death of Faisal the following year and the accession of Ghazi, his access to the palace decreased. Further impeding his influence was the rise of Yasin al-Hashimi

Yasin al-Hashimi, born Yasin Hilmi Salman ( ar, ياسين الهاشمي; 1884 – 21 January 1937), was an Iraqi politician who twice served as the prime minister. Like many of Iraq's early leaders, al-Hashimi served as a military office ...

, who would become prime minister for the first time in 1935. Nevertheless, Nuri continued to hold sway among the military establishment, and his position as a trusted ally of the British meant that he was never far from power. In 1933, the British persuaded Ghazi to appoint him foreign minister, a post he held until the Bakr Sidqi

Bakr Sidqi al-Askari (; 1890 – 11 August 1937) was an Iraqi general of Kurdish origin, born in 1890 in Kirkuk and assassinated on 11 August 1937, at Mosul.

Early life

Bakr Sidqi was born to Kurdish family either in ‘Askar,Edmund Ghareeb, ...

coup in 1936. However, his close ties to the British, which helped him remain in important positions of state, also destroyed any remaining popularity.

Intriguing with army

The Bakr Sidqi coup showed the extent to which Nuri had tied his fate to that of the British in Iraq: he was the only politician of the toppled government to seek refuge in the British Embassy, and his hosts sent him into exile inEgypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

. He returned to Baghdad in August 1937 and began plotting his return to power in collaboration with Colonel Salah al-Din al-Sabbagh

Salah al-Din al-Sabbagh ( ar, صلاح الدين الصباغ; 1899–1945) was an Iraqi Army officer and Arab nationalist that led the Golden Square group which had opposed the government at the time and had highly influenced politics between t ...

. That so perturbed Prime Minister Jamil al-Midfai

Jamil Al Midfai (Arabic: جميل المدفعي; (1958 – 1890)) was an Iraqi politician. He served as the country's prime minister on five separate occasions.

Biography

Born in the town of Mosul, Midfai served in the Ottoman army during Wo ...

that he persuaded the British that Nuri was a disruptive influence who would be better off abroad. They obliged by convincing Nuri to take up residence in London as the Iraqi ambassador. Despairing perhaps of his relationship with Ghazi, he now began to secretly suggest co-operation with the House of Saud

The House of Saud ( ar, آل سُعُود, ʾĀl Suʿūd ) is the ruling royal family of Saudi Arabia. It is composed of the descendants of Muhammad bin Saud, founder of the Emirate of Diriyah, known as the First Saudi state (1727–1818), and ...

.

Back in Baghdad in October 1938, Nuri re-established contact with al-Sabbagh, and persuaded him to overthrow the Midfai government. Al-Sabbagh and his cohorts launched their coup on 24 December 1938, and Nuri was reinstated as prime minister. He sought to sideline the king by promoting the position and possible succession of the latter's half-brother Prince Zaid. Simultaneously, the British were irritated by Ghazi's increasingly nationalistic broadcasts on his private radio station. In January 1939, the king further aggrieved Nuri by appointing Rashid Ali al-Gaylani

Rashid Ali al-Gaylaniin Arab standard pronunciation Rashid Aali al-Kaylani; also transliterated as Sayyid Rashid Aali al-Gillani, Sayyid Rashid Ali al-Gailani or sometimes Sayyad Rashid Ali el Keilany (" Sayyad" serves to address higher standing ...

head of the Royal Divan

A divan or diwan ( fa, دیوان, ''dīvān''; from Sumerian ''dub'', clay tablet) was a high government ministry in various Islamic states, or its chief official (see ''dewan'').

Etymology

The word, recorded in English since 1586, meanin ...

. Nuri's campaign against his rivals continued in March that year, when he claimed to have unmasked a plot to murder Ghazi and used it as an excuse to carry out a purge of the army's officer corps.

When Ghazi died in a car crash on 4 April 1939, Nuri was widely suspected of being implicated in his death. At the royal funeral crowds chanted, "You will answer for the blood of Ghazi, Nuri". He supported the accession of 'Abd al-Ilah

'Abd al-Ilah of Hejaz, ( ar, عبد الإله; also written Abdul Ilah or Abdullah; 14 November 1913 – 14 July 1958) was a cousin and brother-in-law of King Ghazi of the Hashemite Kingdom of Iraq and was regent for his first-cousin once re ...

as regent

A regent (from Latin : ruling, governing) is a person appointed to govern a state '' pro tempore'' (Latin: 'for the time being') because the monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge the powers and duties of the monarchy ...

for Ghazi's successor, Faisal II

Faisal II ( ar, الملك فيصل الثاني ''el-Melik Faysal es-Sânî'') (2 May 1935 – 14 July 1958) was the last King of Iraq. He reigned from 4 April 1939 until July 1958, when he was killed during the 14 July Revolution. This regici ...

, who was still a minor. The new regent was initially susceptible to Nuri's influence.

On 1 September 1939, Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

invaded Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populous ...

. Soon, Germany and Britain were at war. In accordance with Article 4 of the Anglo-Iraqi Treaty, Iraq was committed to declaring war on Germany. Instead, in an effort to maintain a neutral position, Nuri announced that Iraqi armed forces would not be employed outside of Iraq. While German officials were deported, Iraq would not declare war.

By then, affairs in Europe had begun to affect Iraq; the Battle of France

The Battle of France (french: bataille de France) (10 May – 25 June 1940), also known as the Western Campaign ('), the French Campaign (german: Frankreichfeldzug, ) and the Fall of France, was the Nazi Germany, German invasion of French Third Rep ...

in June 1940 encouraged some Arab nationalist elements to seek, in the style of the United States and Turkey, to move toward neutrality toward Germany and Italy rather than being part of the British war effort. While Nuri generally was more pro-British, al-Sabbagh moved into the camp more positively oriented toward Germany. The loss of his main military ally meant that Nuri "quickly lost his ability to affect events".

Co-existence with regent in the 1940s

In April 1941, the pro-neutrality elements seized power, installing Rashid Ali al-Kaylani as prime minister. Nuri fled to British-controlledTransjordan Transjordan may refer to:

* Transjordan (region), an area to the east of the Jordan River

* Oultrejordain, a Crusader lordship (1118–1187), also called Transjordan

* Emirate of Transjordan, British protectorate (1921–1946)

* Hashemite Kingdom of ...

; his protectors then sent him to Cairo, but after occupying Baghdad they brought him back, installing him as prime minister under the British occupation. He would retain the post for over two and half years, but from 1943 onward, the regent obtained a greater say in the selection of his ministers and began to assert greater independence. Iraq remained under British military occupation until late 1947. He served as the President of the Senate of Iraq

The Senate of Iraq (''Majlis al-A`yan'') was the unelected upper house of the bicameral parliament established by the Mandatory Iraq's 1925 constitution. There were around twenty Senators, appointed for eight years by the King of Iraq. The Senate r ...

from July 1945 to November 1946, and from 1948 to January 1949.

The regent's brief flirtation with more liberal policies in 1947 did little to stave off the problems that the established order was facing. The social and economic structures of the country had changed considerably since the establishment of the monarchy, with an increased urban population, a rapidly growing middle class, and increasing political consciousness among the peasants and the working class, in which the Iraqi Communist Party

The Iraqi Communist Party ( ar, الحزب الشيوعي العراقي '; ku, Partiya Komunista Iraqê حزبی شیوعی عێراق) is a communist party and the oldest active party in Iraq. Since its foundation in 1934, it has dominated the ...

was playing a growing role. However, the political elite, with its strong ties and shared interests with the dominant classes, was unable to take the radical steps that might have preserved the monarchy. The attempt by the elite to retain power during the last ten years of the monarchy, Nuri rather than the regent would increasingly play the dominant role, thanks largely to his superior political skills.

Regime resists growing political unrest

In November 1946, an oil workers' strike culminated in a massacre of the strikers by the police, and Nuri was brought back as premier. He briefly brought the Liberals and National Democrats into the cabinet, but soon reverted to the more repressive approach he generally favoured, ordering the arrest of numerous communists in January 1947. Those captured included party secretary Fahd. Meanwhile, Britain attempted to legalise a permanent military presence in Iraq even beyond the terms of the 1930 treaty although it no longer had World War II to justify its continued presence there. Both Nuri and the regent increasingly saw their unpopular links with Great Britain as the best guarantee of their own position, and accordingly set about co-operating in the creation of a new Anglo-Iraqi Treaty. In early January 1948 Nuri himself joined the negotiating delegation in England, and on 15 January the treaty was signed. The response on the streets of Baghdad was immediate and furious. After six years of British occupation, no single act could have been less popular than giving the British an even larger legal role in Iraq's affairs. Demonstrations broke out the following day, with students playing a prominent part and the Communist Party guiding much of the anti-government activity. The protests intensified over the following days, until the police fired on a mass demonstration (20 January), leaving many casualties. On the following days, 'Abd al-Ilah disavowed the new treaty. Nuri returned to Baghdad on 26 January and immediately implemented a harsh policy of repression against the protesters. At mass demonstration the next day, police fired again at the protesters, leaving many more dead. In his struggle to implement the treaty, Nuri had destroyed any credibility that he had left. He retained considerable power throughout the country, but he was generally hated. He was determined to drive the Jews out of his country as quickly as possible, and on 21 August 1950, he threatened to revoke the license of the company transporting the Jewish exodus if it did not fulfill its daily quota of 500 Jews. On 18 September 1950, Nuri summoned a representative of the Jewish community, claimed Israel was behind the emigration delay and threatened to "take them to the borders" and expel the Jews. The next major political demarche with which Nuri's name would be associated was theBaghdad Pact

The Middle East Treaty Organization (METO), also known as the Baghdad Pact and subsequently known as the Central Treaty Organization (CENTO), was a military alliance of the Cold War. It was formed in 24 February 1955 by Iran, Iraq, Pakistan, Turk ...

, a series of agreements concluded between 1954 and 1955, which tied Iraq politically and militarily with the Western powers and their regional allies, notably Turkey. The pact was especially important to Nuri, as it was favoured by the British and Americans. On the other hand, it was also contrary to the political aspirations of most of the country. Taking advantage of the situation, Nuri stepped up his policies of political repression and censorship. Now, however, the reaction was less fierce than it had been in 1948. According to historian Hanna Batatu, that can be attributed to slightly more favourable economic circumstances and the weakness of the Communist Party, damaged by police repression and internal division.

The political situation deteriorated in 1956, when Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

, France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

and Britain colluded in an invasion of Egypt, in response to the nationalisation of the Suez Canal

The Suez Canal ( arz, قَنَاةُ ٱلسُّوَيْسِ, ') is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia. The long canal is a popular ...

by President Gamal Abdel Nasser

Gamal Abdel Nasser Hussein, . (15 January 1918 – 28 September 1970) was an Egyptian politician who served as the second president of Egypt from 1954 until his death in 1970. Nasser led the Egyptian revolution of 1952 and introduced far-re ...

. Nuri was overjoyed with the tripartite move and instructed the radio station to play ''The Postmen Complained about the Abundance of My Letters'' as a way to mock Nasser, whose father was a postal clerk. However, Nuri then publicly condemned the invasion, as the national sentiment was strongly for Egypt. The invasion exacerbated popular mistrust of the Baghdad Pact, and Nuri responded by refusing to sit with British representatives during a meeting of the Pact and cut off diplomatic relations with France. According to historian Adeeb Dawish, "Nuri's circumspect response hardly placated the seething populace."

Mass protests and disturbances occurred throughout the country, in Baghdad, Basrah

Basra ( ar, ٱلْبَصْرَة, al-Baṣrah) is an Iraqi city located on the Shatt al-Arab. It had an estimated population of 1.4 million in 2018. Basra is also Iraq's main port, although it does not have deep water access, which is hand ...

, Mosul

Mosul ( ar, الموصل, al-Mawṣil, ku, مووسڵ, translit=Mûsil, Turkish: ''Musul'', syr, ܡܘܨܠ, Māwṣil) is a major city in northern Iraq, serving as the capital of Nineveh Governorate. The city is considered the second large ...

, Kufa

Kufa ( ar, الْكُوفَة ), also spelled Kufah, is a city in Iraq, about south of Baghdad, and northeast of Najaf. It is located on the banks of the Euphrates River. The estimated population in 2003 was 110,000. Currently, Kufa and Najaf ...

, Najaf

Najaf ( ar, ٱلنَّجَف) or An-Najaf al-Ashraf ( ar, ٱلنَّجَف ٱلْأَشْرَف), also known as Baniqia ( ar, بَانِيقِيَا), is a city in central Iraq about 160 km (100 mi) south of Baghdad. Its estimated popula ...

and al-Hillah

Hillah ( ar, ٱلْحِلَّة ''al-Ḥillah''), also spelled Hilla, is a city in central Iraq on the Hilla branch of the Euphrates River, south of Baghdad. The population is estimated at 364,700 in 1998. It is the capital of Babylon Province ...

. In response Nuri decreed martial law

Martial law is the imposition of direct military control of normal civil functions or suspension of civil law by a government, especially in response to an emergency where civil forces are overwhelmed, or in an occupied territory.

Use

Marti ...

and sent in troops to some southern cities to suppress the riots, while in Baghdad, nearly 400 protesters were detained. Nuri's political position was weakened, so much that he became more "discouraged and depressed" than ever before (according to the British ambassador) and was genuinely fearful that he would be unable to restore stability.Dawisha, pp. 182–183. Meanwhile, the opposition began to co-ordinate its activities: in February 1957, a Front of National Union was established, bringing together the National Democrats, the Independents, the Communists, and the Ba'th Party

The Arab Socialist Baʿath Party ( ar, حزب البعث العربي الاشتراكي ' ) was a political party founded in Syria by Mishel ʿAflaq, Ṣalāḥ al-Dīn al-Bītār, and associates of Zaki al-ʾArsūzī. The party espoused B ...

. A similar process within the military officer corps followed, with the formation of the Supreme Committee of Free Officers. However, Nuri's attempts to preserve the loyalty of the military by generous benefits failed.

The Iraqi monarchy and its Hashemite ally in Jordan reacted to the union between Egypt and Syria (February 1958) by forming the Arab Federation of Iraq and Jordan. (Kuwait was asked to enter the union; however, the British opposed this.) Nuri was the first prime minister of the new federation, which was soon ended with the coup that toppled the Iraqi monarchy.

Fall of monarchy and death

As the1958 Lebanon crisis

The 1958 Lebanon crisis (also known as the Lebanese Civil War of 1958) was a political crisis in Lebanon caused by political and religious tensions in the country that included a United States military intervention. The intervention lasted for aro ...

escalated, Jordan

Jordan ( ar, الأردن; tr. ' ), officially the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan,; tr. ' is a country in Western Asia. It is situated at the crossroads of Asia, Africa, and Europe, within the Levant region, on the East Bank of the Jordan Rive ...

requested the help of Iraqi troops, who feigned to be ''en route'' there on 14 July. Instead, they moved on to Baghdad, and on that day, Brigadier Abd al-Karim Qasim

Abd al-Karim Qasim Muhammad Bakr al-Fadhli al-Zubaidi ( ar, عبد الكريم قاسم ' ) (21 November 1914 – 9 February 1963) was an Iraqi Army brigadier and nationalist who came to power when the Iraqi monarchy was overthrown ...

and Colonel Abdul Salam Arif

ʿAbd al-Salam Mohammed ʿArif al-Jumayli ( ar, عبد السلام محمد عارف الجميلي'; 21 March 1921 – 13 April 1966) was the second president of Iraq from 1963 until his death in a plane crash in 1966. He played a leading role ...

seized control of the country and ordered the Royal Family to evacuate the Rihab Palace in Baghdad. They congregated in the courtyard—King Faisal II

Faisal II ( ar, الملك فيصل الثاني ''el-Melik Faysal es-Sânî'') (2 May 1935 – 14 July 1958) was the last King of Iraq. He reigned from 4 April 1939 until July 1958, when he was killed during the 14 July Revolution. This regici ...

; Prince 'Abd al-Ilah and his wife Princess Hiyam

Princess Hiyam (1933–1999) was the Iraqi Crown Princess through marriage to Crown Prince 'Abd al-Ilah. She was the aunt by marriage to King Faisal II of Iraq. She survived the massacre of the royal family during the 14 July Revolution.

She was ...

; Princess Nafeesa, Abdul Ilah's mother; Princess Abadiya

Aliya bint Ali (1907 – 14 July 1958) was an Iraqi princess. She was the daughter of Ali, King of Hejaz, and Princess Nafeesa, sister of Crown Prince 'Abd al-Ilah, and the aunt of King Faisal II of Iraq. She was murdered in the massacre of the ...

, the king's aunt; and several servants. The group was ordered to turn facing the wall and were shot down by Captain Abdus Sattar As Sab', a member of the coup. After almost four decades, the monarchy had been toppled.

Nuri went into hiding, but he was captured the next day as he sought to make his escape disguised as a woman. He was shot dead and buried that same day, but an angry mob disinterred his corpse and dragged it through the streets of Baghdad, where it was hung up, burned and mutilated, ultimately being run over repeatedly by municipal buses, until his corpse was unrecognizable.

Personal life and family

Nuri and his wife had one son, Sabah As-Said, who married an Egyptian heiress, Esmat Ali Pasha Fahmi in 1936. They had two sons: Falah (born 1937) andIssam

Issam Harris (born 22 May 1993), known by his stage name Issam ( ar, عصام), is a Moroccan hip hop, Moroccan rapper, songwriter and Trap music, trap artist. He was born in Derb Sultan, Casablanca and became known in 2018 with his song and musi ...

(born 1938). Sabah As-Said is supposed to have taken an Iraqi-Jewish woman as a second wife and had a child with her when Jews accounted for 25-40% of Baghdad's population. After being ousted from Iraq, both his second wife and child fled to Israel.

Falah, who worked as King Hussein's personal pilot, was first married to Nahla El-Askari and had one son, Sabah. He later married Dina Fawaz Maher in 1974, the daughter of a Jordanian army general, Fawaz Pasha Maher, and had two daughters: Sima and Zaina.

Falah died in a car accident in Jordan in 1983. Issam was an artist and architect based in London who died in 1988 from a heart attack.Al-Ali, and Al-Najjar, D., ''We Are Iraqis: Aesthetics and Politics in a Time of War,'' Syracuse University Press, 2013, p. 42

See also

*Kinahan Cornwallis

Sir Kinahan Cornwallis (19 February 1883 – 3 June 1959) was a British administrator and diplomat best known for being an advisor to King Faisal I of Iraq and for being the British Ambassador to the Kingdom of Iraq during the Anglo-Iraqi ...

– British Ambassador to Iraq

* Fritz Grobba

Fritz Konrad Ferdinand Grobba (18 July 1886 – 2 September 1973) was a German diplomat during the interwar period and World War II.

Early life

He was born in Gartz on the Oder in the Province of Brandenburg, Germany. His parents were Rudolf Grob ...

– German Ambassador to Iraq

Notes

Sources

*Batatu, Hanna: ''The Old Social Classes and New Revolutionary Movements of Iraq'', al-Saqi Books, London, 2000, *Gallman, Waldemar J.: ''Iraq under General Nuri: My Recollection of Nuri Al-Said, 1954–1958'', Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 1964, *Lukutz, Liora: ''Iraq: The Search for National Identity'', pp. 256-, Routledge Publishing, 1995, * O'Sullivan, Christopher D. ''FDR and the End of Empire: The Origins of American Power in the Middle East.'' Palgrave Macmillan, 2012, * Simons, Geoff: ''Iraq: From Sumer to Saddam'', Palgrave Macmillan, 2004 (3rd edition), *Tripp, Charles: ''A History of Iraq'', Cambridge University Press, 2002,External links

* * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Said, Nuri al- 1888 births 1958 deaths People from Baghdad Ottoman Military Academy alumni Ottoman Military College alumni Ottoman Army officers Ottoman military personnel of World War I Ottoman prisoners of war World War I prisoners of war held by the United Kingdom Presidents of the Senate of Iraq Prime Ministers of Iraq Leaders ousted by a coup Iraqi Arab nationalists Honorary Members of the Order of the Companions of Honour 20th-century executions by Iraq Arab independence activists Executed prime ministers Lynching deaths Iraqi anti-communists Iraqi exiles