Nuclear Waste Policy Act on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Nuclear Waste Policy Act of 1982 is a United States federal law which established a comprehensive national program for the safe, permanent disposal of highly radioactive wastes.

* The US Congress amended the act in 1987 to designate Yucca Mountain, Nevada, as the sole repository.

* The act allowed Nevada to override this designation, which it did in April 2002.

* Congress overrode Nevada's veto in July 2002.

* Nevada appealed, and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia sided with Nevada in 2004.

* At least one other jurisdiction (Aiken County, South Carolina in 2011) filed suit to force Yucca Mountain to accept the nuclear waste from the rest of the US.

The Nuclear Waste Policy Act required the Secretary of Energy to issue guidelines for selection of sites for construction of two permanent, underground nuclear waste repositories. DOE was to study five potential sites, and then recommend three to the President by January 1, 1985. Five additional sites were to be studied and three of them recommended to the president by July 1, 1989, as possible locations for a second repository. A full environmental impact statement was required for any site recommended to the President.

Locations considered to be leading contenders for a permanent repository were basalt formations at the government's Hanford Nuclear Reservation in Washington, volcanic tuff formations at its Nevada nuclear test site, and several salt formations in Utah, Texas, Louisiana, and Mississippi. Salt and granite formations in other states from Maine to Georgia had also been surveyed, but not evaluated in great detail.

The President was required to review site recommendations and submit to Congress by March 31, 1987, his recommendation of one site for the first repository, and by March 31, 1990, his recommendation for a second repository. The amount of high-level waste or spent fuel that could be placed in the first repository was limited to the equivalent of 70,000 metric tons of heavy metal until a second repository was built. The Act required the national government to take ownership of all nuclear waste or spent fuel at the reactor site, transport it to the repository, and thereafter be responsible for its containment.

The Nuclear Waste Policy Act required the Secretary of Energy to issue guidelines for selection of sites for construction of two permanent, underground nuclear waste repositories. DOE was to study five potential sites, and then recommend three to the President by January 1, 1985. Five additional sites were to be studied and three of them recommended to the president by July 1, 1989, as possible locations for a second repository. A full environmental impact statement was required for any site recommended to the President.

Locations considered to be leading contenders for a permanent repository were basalt formations at the government's Hanford Nuclear Reservation in Washington, volcanic tuff formations at its Nevada nuclear test site, and several salt formations in Utah, Texas, Louisiana, and Mississippi. Salt and granite formations in other states from Maine to Georgia had also been surveyed, but not evaluated in great detail.

The President was required to review site recommendations and submit to Congress by March 31, 1987, his recommendation of one site for the first repository, and by March 31, 1990, his recommendation for a second repository. The amount of high-level waste or spent fuel that could be placed in the first repository was limited to the equivalent of 70,000 metric tons of heavy metal until a second repository was built. The Act required the national government to take ownership of all nuclear waste or spent fuel at the reactor site, transport it to the repository, and thereafter be responsible for its containment.

In December 1987, Congress amended the Nuclear Waste Policy Act to designate Yucca Mountain, Nevada, as the only site to be characterized as a permanent repository for all of the nation's nuclear waste. The plan was added to the fiscal 1988 budget reconciliation bill signed on December 22, 1987.

Working under the 1982 Act, DOE had narrowed down the search for the first nuclear-waste repository to three Western states: Nevada, Washington, and Texas. The amendment repealed provisions in the 1982 law calling for a second repository in the eastern United States. No one from Nevada participated on the House–Senate conference committee on reconciliation.

The amendment explicitly named Yucca Mountain as the only site that DOE was to consider for a permanent repository for the nation's radioactive waste. Years of study and procedural steps remained. The amendment also authorized a monitored retrievable storage facility, but not until the permanent repository was licensed.

Early in 2002, the Secretary of Energy recommended approval of Yucca Mountain for development of a repository based on the multiple factors as required in the Nuclear Waste Policy Act of 1987 and, after review, President George W. Bush submitted the recommendation to Congress for its approval. Nevada exercised its state veto in April 2002, but the veto was overridden by both houses of Congress by mid-July 2002. In 2004, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit upheld a challenge by Nevada, ruling that EPA's 10,000-year compliance period for isolation of radioactive waste was not consistent with National Academy of Sciences (NAS) recommendations and was too short. The NAS report had recommended standards be set for the time of peak risk, which might approach a period of one million years. By limiting the compliance time to 10,000 years, EPA did not respect a statutory requirement that it develop standards consistent with NAS recommendations. The EPA subsequently revised the standards to extend out to 1 million years. A license application was submitted in the summer of 2008 and is presently under review by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission.

The

In December 1987, Congress amended the Nuclear Waste Policy Act to designate Yucca Mountain, Nevada, as the only site to be characterized as a permanent repository for all of the nation's nuclear waste. The plan was added to the fiscal 1988 budget reconciliation bill signed on December 22, 1987.

Working under the 1982 Act, DOE had narrowed down the search for the first nuclear-waste repository to three Western states: Nevada, Washington, and Texas. The amendment repealed provisions in the 1982 law calling for a second repository in the eastern United States. No one from Nevada participated on the House–Senate conference committee on reconciliation.

The amendment explicitly named Yucca Mountain as the only site that DOE was to consider for a permanent repository for the nation's radioactive waste. Years of study and procedural steps remained. The amendment also authorized a monitored retrievable storage facility, but not until the permanent repository was licensed.

Early in 2002, the Secretary of Energy recommended approval of Yucca Mountain for development of a repository based on the multiple factors as required in the Nuclear Waste Policy Act of 1987 and, after review, President George W. Bush submitted the recommendation to Congress for its approval. Nevada exercised its state veto in April 2002, but the veto was overridden by both houses of Congress by mid-July 2002. In 2004, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit upheld a challenge by Nevada, ruling that EPA's 10,000-year compliance period for isolation of radioactive waste was not consistent with National Academy of Sciences (NAS) recommendations and was too short. The NAS report had recommended standards be set for the time of peak risk, which might approach a period of one million years. By limiting the compliance time to 10,000 years, EPA did not respect a statutory requirement that it develop standards consistent with NAS recommendations. The EPA subsequently revised the standards to extend out to 1 million years. A license application was submitted in the summer of 2008 and is presently under review by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission.

The

Historical overview

During the first 40 years that nuclear waste was being created in the United States, no legislation was enacted to manage its disposal. Nuclear waste, some of which remains radioactive with a half-life of more than one million years, was kept in various types of temporary storage. Of particular concern during nuclear waste disposal are two long-lived fission products, Tc-99 (half-life 220,000 years) andI-129 I129 or I-129 may refer to:

*Interstate 129, an auxiliary Interstate Highway which connects South Sioux City, Nebraska to Interstate 29 in Sioux City, Iowa

*Iodine-129 (I-129 or 129I), a radioactive isotope of iodine

*Form I-129 (Petition for a Non ...

(half-life 17 million years), which dominate spent fuel radioactivity after a few thousand years. The most troublesome transuranic elements in spent fuel are Np-237

Neptunium (93Np) is usually considered an artificial element, although trace quantities are found in nature, so a standard atomic weight cannot be given. Like all trace or artificial elements, it has no stable isotopes. The first isotope to be syn ...

(half-life two million years) and Pu-239

Plutonium-239 (239Pu or Pu-239) is an isotope of plutonium. Plutonium-239 is the primary fissile isotope used for the production of nuclear weapons, although uranium-235 is also used for that purpose. Plutonium-239 is also one of the three main ...

(half-life 24,000 years).

Most existing nuclear waste came from production of nuclear weapons

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bomb ...

. About 77 million gallons of military nuclear waste in liquid form was stored in steel tanks, mostly in South Carolina, Washington, and Idaho. In the private sector, 82 nuclear plants operating in 1982 used uranium fuel to produce electricity. Highly radioactive spent fuel rods were stored in pools of water at reactor sites, but many utilities were running out of storage space.Comprehensive nuclear waste plan enacted. ''Congressional Quarterly Almanac'' 1982. Washington, DC: Congressional Quarterly, Inc., 304–310.

The Nuclear Waste Policy Act of 1982 created a timetable and procedure for establishing a permanent, underground repository for high-level radioactive waste by the mid-1990s, and provided for some temporary federal storage of waste, including spent fuel from civilian nuclear reactors

A nuclear reactor is a device used to initiate and control a fission nuclear chain reaction or nuclear fusion reactions. Nuclear reactors are used at nuclear power plants for electricity generation and in nuclear marine propulsion. Heat from nu ...

. State governments were authorized to veto a national government decision to place a waste repository within their borders, and the veto would stand unless both houses of Congress voted to override it. The Act also called for developing plans by 1985 to build monitored retrievable storage (MRS) facilities, where wastes could be kept for 50 to 100 years or more and then be removed for permanent disposal or for reprocessing.

Congress assigned responsibility to the U.S. Department of Energy

The United States Department of Energy (DOE) is an executive department of the U.S. federal government that oversees U.S. national energy policy and manages the research and development of nuclear power and nuclear weapons in the United States. ...

(DOE) to site, construct, operate, and close a repository for the disposal of spent nuclear fuel and high-level radioactive waste. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) was directed to set public health and safety standards for releases of radioactive materials from a repository, and the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission

The Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) is an independent agency of the United States government tasked with protecting public health and safety related to nuclear energy. Established by the Energy Reorganization Act of 1974, the NRC began operat ...

(NRC) was required to promulgate regulations governing construction, operation, and closure of a repository. Generators and owners of spent nuclear fuel and high-level radioactive waste were required to pay the costs of disposal of such radioactive materials. The waste program, which was expected to cost billions of dollars, would be funded through a fee paid by electric utilities on nuclear-generated electricity. An Office of Civilian Radioactive Waste Management was established in the DOE to implement the Act.

Permanent repositories

The Nuclear Waste Policy Act required the Secretary of Energy to issue guidelines for selection of sites for construction of two permanent, underground nuclear waste repositories. DOE was to study five potential sites, and then recommend three to the President by January 1, 1985. Five additional sites were to be studied and three of them recommended to the president by July 1, 1989, as possible locations for a second repository. A full environmental impact statement was required for any site recommended to the President.

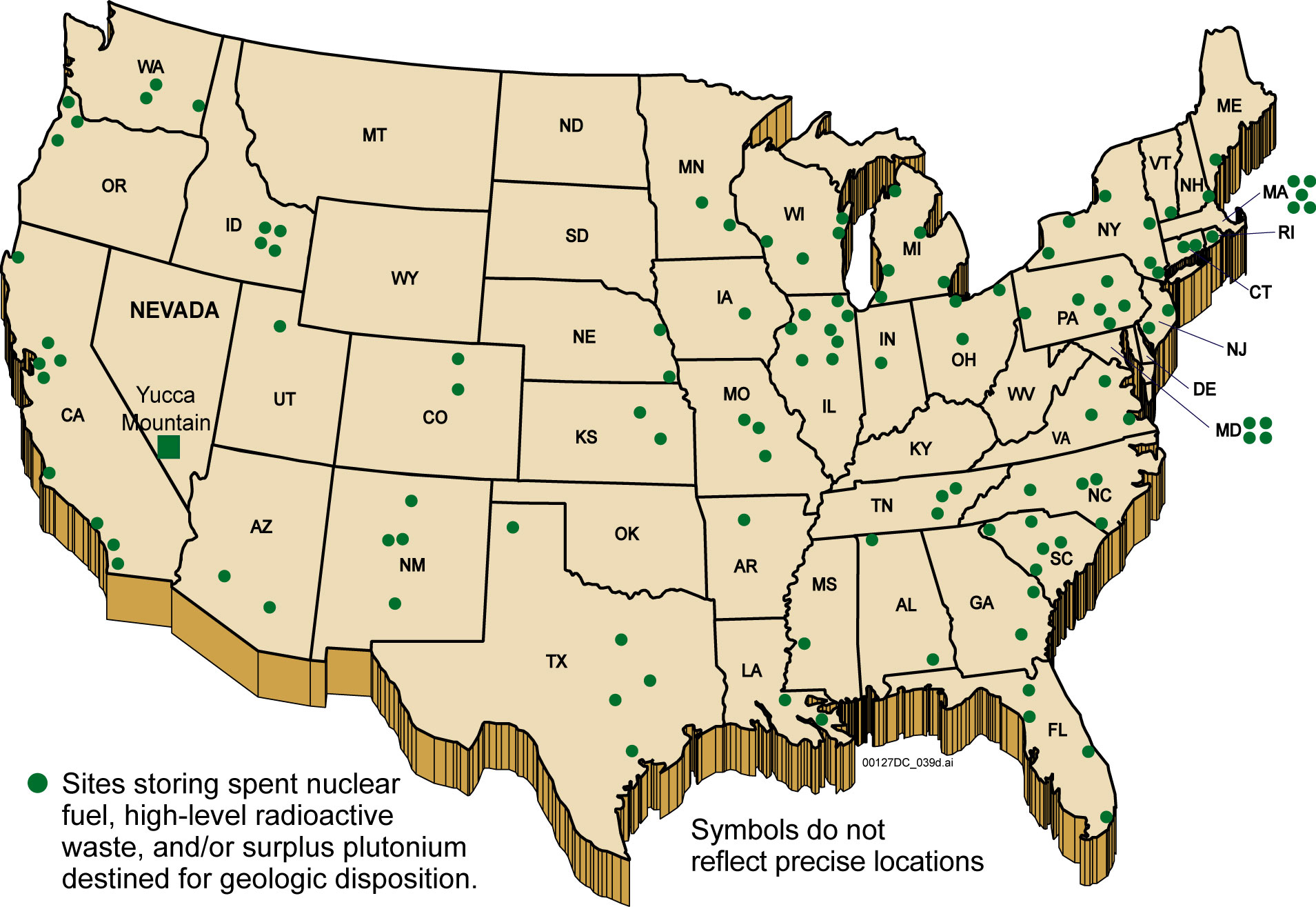

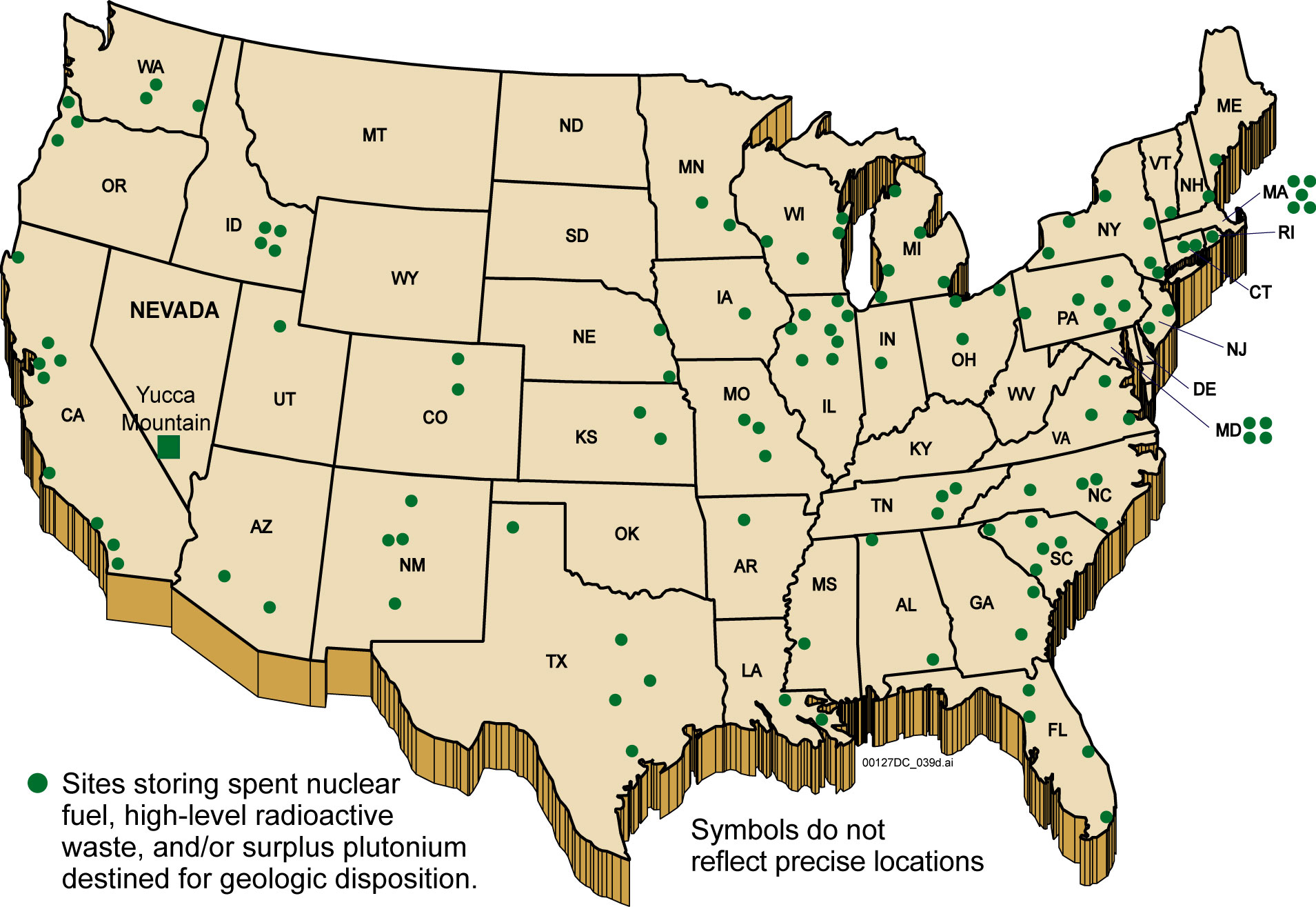

Locations considered to be leading contenders for a permanent repository were basalt formations at the government's Hanford Nuclear Reservation in Washington, volcanic tuff formations at its Nevada nuclear test site, and several salt formations in Utah, Texas, Louisiana, and Mississippi. Salt and granite formations in other states from Maine to Georgia had also been surveyed, but not evaluated in great detail.

The President was required to review site recommendations and submit to Congress by March 31, 1987, his recommendation of one site for the first repository, and by March 31, 1990, his recommendation for a second repository. The amount of high-level waste or spent fuel that could be placed in the first repository was limited to the equivalent of 70,000 metric tons of heavy metal until a second repository was built. The Act required the national government to take ownership of all nuclear waste or spent fuel at the reactor site, transport it to the repository, and thereafter be responsible for its containment.

The Nuclear Waste Policy Act required the Secretary of Energy to issue guidelines for selection of sites for construction of two permanent, underground nuclear waste repositories. DOE was to study five potential sites, and then recommend three to the President by January 1, 1985. Five additional sites were to be studied and three of them recommended to the president by July 1, 1989, as possible locations for a second repository. A full environmental impact statement was required for any site recommended to the President.

Locations considered to be leading contenders for a permanent repository were basalt formations at the government's Hanford Nuclear Reservation in Washington, volcanic tuff formations at its Nevada nuclear test site, and several salt formations in Utah, Texas, Louisiana, and Mississippi. Salt and granite formations in other states from Maine to Georgia had also been surveyed, but not evaluated in great detail.

The President was required to review site recommendations and submit to Congress by March 31, 1987, his recommendation of one site for the first repository, and by March 31, 1990, his recommendation for a second repository. The amount of high-level waste or spent fuel that could be placed in the first repository was limited to the equivalent of 70,000 metric tons of heavy metal until a second repository was built. The Act required the national government to take ownership of all nuclear waste or spent fuel at the reactor site, transport it to the repository, and thereafter be responsible for its containment.

Temporary spent fuel storage

The Act authorized DOE to provide up to 1,900 metric tons of temporary storage capacity for spent fuel from civilian nuclear reactors. It required that spent fuel in temporary storage facilities be moved to permanent storage within three years after a permanent waste repository went into operation. Costs of temporary storage would be paid by fees collected from electric utilities using the storage.Monitored retrievable storage

The Act required the Secretary of Energy to report to Congress by June 1, 1985, on the need for and feasibility of a monitored retrievable storage facility (MRS) and specified that the report was to include five different combinations of proposed sites and facility designs, involving at least three different locations. Environmental assessments were required for the sites. It barred construction of a MRS facility in a state under consideration for a permanent waste repository. The DOE in 1985 recommended an integral MRS facility. Of the eleven sites identified within the preferred geographic region, the DOE selected three sites in Tennessee for further study. In March 1987, after more than a year of legal action in the federal courts, the DOE submitted its final proposal to Congress for the construction of a MRS facility at the Clinch River Breeder Reactor Site in Oak Ridge, Tennessee. Following considerable public pressure and threat of veto by the Governor of Tennessee, the 1987 amendments to the NWPA "annulled and revoked" MRS plans for all of the proposed sites. There are carefully selected geological locations that build places specifically for disposing nuclear waste in a safe location.State veto of site selected

The Act required DOE to consult closely throughout the site selection process with states or Indian tribes that might be affected by the location of a waste facility, and allowed a state (governor or legislature) or Indian tribe to veto a federal decision to place within its borders a waste repository or temporary storage facility holding 300 tons or more of spent fuel, but provided that the veto could be overruled by a vote of both houses of Congress.Payment of costs

The Act established a Nuclear Waste Fund composed of fees levied against electric utilities to pay for the costs of constructing and operating a permanent repository, and set the fee at one mill per kilowatt-hour of nuclear electricity generated. Utilities were charged a one-time fee for storage of spent fuel created before enactment of the law. Nuclear waste from defense activities was exempted from most provisions of the Act, which required that if military waste were put into a civilian repository, the government would pay its pro rata share of the cost of development, construction, and operation of the repository. The Act authorized impact assistance payments to states or Indian tribes to offset any costs resulting from location of a waste facility within their borders.Nuclear Waste Fund

The Nuclear Waste Fund previously received $750 million in fee revenues each year and had an unspent balance of $44.5 billion as of the end of FY2017. However (according to the Draft Report by the Blue Ribbon Commission on America's Nuclear Future), actions by both Congress and the Executive Branch have made the money in the fund effectively inaccessible to serving its original purpose. The commission made several recommendations on how this situation may be corrected. In late 2013, a federal court ruled that the Department of Energy must stop collecting fees for nuclear waste disposal until provisions are made to collect nuclear waste.Yucca Mountain

In December 1987, Congress amended the Nuclear Waste Policy Act to designate Yucca Mountain, Nevada, as the only site to be characterized as a permanent repository for all of the nation's nuclear waste. The plan was added to the fiscal 1988 budget reconciliation bill signed on December 22, 1987.

Working under the 1982 Act, DOE had narrowed down the search for the first nuclear-waste repository to three Western states: Nevada, Washington, and Texas. The amendment repealed provisions in the 1982 law calling for a second repository in the eastern United States. No one from Nevada participated on the House–Senate conference committee on reconciliation.

The amendment explicitly named Yucca Mountain as the only site that DOE was to consider for a permanent repository for the nation's radioactive waste. Years of study and procedural steps remained. The amendment also authorized a monitored retrievable storage facility, but not until the permanent repository was licensed.

Early in 2002, the Secretary of Energy recommended approval of Yucca Mountain for development of a repository based on the multiple factors as required in the Nuclear Waste Policy Act of 1987 and, after review, President George W. Bush submitted the recommendation to Congress for its approval. Nevada exercised its state veto in April 2002, but the veto was overridden by both houses of Congress by mid-July 2002. In 2004, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit upheld a challenge by Nevada, ruling that EPA's 10,000-year compliance period for isolation of radioactive waste was not consistent with National Academy of Sciences (NAS) recommendations and was too short. The NAS report had recommended standards be set for the time of peak risk, which might approach a period of one million years. By limiting the compliance time to 10,000 years, EPA did not respect a statutory requirement that it develop standards consistent with NAS recommendations. The EPA subsequently revised the standards to extend out to 1 million years. A license application was submitted in the summer of 2008 and is presently under review by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission.

The

In December 1987, Congress amended the Nuclear Waste Policy Act to designate Yucca Mountain, Nevada, as the only site to be characterized as a permanent repository for all of the nation's nuclear waste. The plan was added to the fiscal 1988 budget reconciliation bill signed on December 22, 1987.

Working under the 1982 Act, DOE had narrowed down the search for the first nuclear-waste repository to three Western states: Nevada, Washington, and Texas. The amendment repealed provisions in the 1982 law calling for a second repository in the eastern United States. No one from Nevada participated on the House–Senate conference committee on reconciliation.

The amendment explicitly named Yucca Mountain as the only site that DOE was to consider for a permanent repository for the nation's radioactive waste. Years of study and procedural steps remained. The amendment also authorized a monitored retrievable storage facility, but not until the permanent repository was licensed.

Early in 2002, the Secretary of Energy recommended approval of Yucca Mountain for development of a repository based on the multiple factors as required in the Nuclear Waste Policy Act of 1987 and, after review, President George W. Bush submitted the recommendation to Congress for its approval. Nevada exercised its state veto in April 2002, but the veto was overridden by both houses of Congress by mid-July 2002. In 2004, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit upheld a challenge by Nevada, ruling that EPA's 10,000-year compliance period for isolation of radioactive waste was not consistent with National Academy of Sciences (NAS) recommendations and was too short. The NAS report had recommended standards be set for the time of peak risk, which might approach a period of one million years. By limiting the compliance time to 10,000 years, EPA did not respect a statutory requirement that it develop standards consistent with NAS recommendations. The EPA subsequently revised the standards to extend out to 1 million years. A license application was submitted in the summer of 2008 and is presently under review by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission.

The Obama Administration

Barack Obama's tenure as the 44th president of the United States began with his first inauguration on January 20, 2009, and ended on January 20, 2017. A Democrat from Illinois, Obama took office following a decisive victory over Republican ...

rejected use of the site in the 2010 United States federal budget

The United States Federal Budget for Fiscal Year 2010, titled A New Era of Responsibility: Renewing America's Promise, is a United States federal budget, spending request by President of the United States, President Barack Obama to fund governm ...

, which eliminated all funding except that needed to answer inquiries from the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, "while the Administration devises a new strategy toward nuclear waste disposal." On March 5, 2009, Energy Secretary Steven Chu

Steven ChuHannes Alfvén, Nobel laureate in physics, described the as-yet-unresolved dilemma of permanent

EPA Laws & Regulations

* {{cite web , url=http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/STATUTE-94/pdf/STATUTE-94-Pg3347.pdf , title=Low-Level Radioactive Waste Policy Act – P.L. 96-573 , work=U.S. Senate Bill S. 2189 ~ 94 Stat. 3347 , publisher=U.S. Government Printing Office 1982 in law United States federal energy legislation United States federal environmental legislation 97th United States Congress 1982 in the environment Radioactive waste Acts of the 97th United States Congress

radioactive waste disposal Radioactive waste disposal may refer to:

*High-level radioactive waste management

* Low-level waste disposal

*Ocean disposal of radioactive waste

**Ocean floor disposal

*Deep borehole disposal

*Deep geological repository

See also

* Radioactive wast ...

:

"The problem is how to keep radioactive waste in storage until it decays after hundreds of thousands of years. The eologicdeposit must be absolutely reliable as the quantities of poison are tremendous. It is very difficult to satisfy these requirements for the simple reason that we have had no practical experience with such a long term project. Moreover permanently guarded storage requires a society with unprecedented stability."

Thus, Alfvén identified two fundamental prerequisites for effective management of high-level radioactive waste: (1) stable geological formations, and (2) stable human institutions over hundreds of thousands of years. However, no known human civilization has ever endured for so long. Moreover, no geologic formation of adequate size for a permanent radioactive waste repository has yet been discovered that has been stable for so long a period.

Because some radioactive species have half-lives longer than one million years, even very low container leakage and radionuclide migration rates must be taken into account. Moreover, it may require more than one half-life until some nuclear waste loses enough radioactivity so that it is no longer lethal to humans. Waste containers have a modeled lifetime of 12,000 to over 100,000 years and it is assumed they will fail in about two million years. A 1983 review of the Swedish radioactive waste disposal program by the National Academy of Sciences found that country's estimate of about one million years being necessary for waste isolation "fully justified."

The Nuclear Waste Policy Act did not require anything approaching this standard for permanent deep-geologic disposal of high-level radioactive waste in the United States. U.S. Department of Energy

guidelines for selecting locations for permanent deep-geologic high-level radioactive waste repositories required containment of waste within waste packages for only 300 years. A site would be disqualified from further consideration only if groundwater travel time from the "disturbed zone" of the underground facility to the "accessible environment" (atmosphere, land surface, surface water, oceans or lithosphere extending no more than 10 kilometers from the underground facility) was expected to be less than 1,000 years along any pathway of radionuclide travel. Sites with groundwater travel time greater than 1,000 years from the original location to the human environment were considered potentially acceptable, even if the waste would be highly radioactive for 200,000 years or more.

Moreover, the term "disturbed zone" was defined in the regulations to exclude shafts drilled into geologic structures from the surface, so the standard applied to natural geologic pathways was more stringent than the standard applied to artificial pathways of radionuclide travel created during construction of the facility.

Alternative to waste storage

Enrico Fermi described an alternative solution: Consume all actinides in fast neutron reactors, leaving only fission products requiring special custody for less than 300 years. This requires continuous fuel reprocessing. PUREX separates plutonium and uranium, but leaves other actinides with fission products, thereby not addressing the long-term custody problem. Pyroelectric refining, as perfected at EBR-II, separates essentially all actinides from fission products. U.S. DOE Research on pyroelectric refining and fast neutron reactors was stopped in 1994.Repository closure

Current repository closure plans require backfilling of waste disposal rooms, tunnels, and shafts with rubble from initial excavation and sealing openings at the surface, but do not require complete or perpetual isolation of radioactive waste from the human environment. Current policy relinquishes control over radioactive materials to geohydrologic processes at repository closure. Existing models of these processes are empirically underdetermined, meaning there is not much evidence they are accurate. DOE guidelines contain no requirements for permanent offsite or onsite monitoring after closure.Nuclear Waste Policy Act of 1982. 96 ''Statutes at large'' 2201, 42 ''U.S. Code'' 10101 ''et seq''. This may seem imprudent, considering repositories will contain millions of dollars worth of spent reactor fuel that might be reprocessed and used again either in reactors generating electricity, in weapons applications, or possibly in terrorist activities. Technology for permanently sealing large-bore-hole walls against water infiltration or fracture does not currently exist. Previous experiences sealing mine tunnels and shafts have not been entirely successful, especially where there is any hydraulic pressure from groundwater infiltration into disturbed underground geologic structures. Historical attempts to seal smaller bore holes created during exploration for oil, gas, and water are notorious for their high failure rates, often in periods less than 50 years.See also

* Non-Proliferation Trust * Basalt Waste Isolation ProjectReferences

External links

* Summary of Nuclear Waste Policy Act can be found on the EPA siteEPA Laws & Regulations

* {{cite web , url=http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/STATUTE-94/pdf/STATUTE-94-Pg3347.pdf , title=Low-Level Radioactive Waste Policy Act – P.L. 96-573 , work=U.S. Senate Bill S. 2189 ~ 94 Stat. 3347 , publisher=U.S. Government Printing Office 1982 in law United States federal energy legislation United States federal environmental legislation 97th United States Congress 1982 in the environment Radioactive waste Acts of the 97th United States Congress