Nuclear Arsenal Of The USA on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The

Arms Control Association (updated: July 2019).

The United States first began developing nuclear weapons during

The United States first began developing nuclear weapons during

In the 2013 book '' Plutopia: Nuclear Families, Atomic Cities, and the Great Soviet and American Plutonium Disasters'' (Oxford),

In the 2013 book '' Plutopia: Nuclear Families, Atomic Cities, and the Great Soviet and American Plutonium Disasters'' (Oxford),

Between 16 July 1945 and 23 September 1992, the United States maintained a program of vigorous

Between 16 July 1945 and 23 September 1992, the United States maintained a program of vigorous

The original Little Boy and Fat Man weapons, developed by the United States during the

The original Little Boy and Fat Man weapons, developed by the United States during the

Development of long-range bombers, such as the

Development of long-range bombers, such as the  The current delivery systems of the U.S. make virtually any part of the Earth's surface within the reach of its nuclear arsenal. Though its land-based missile systems have a maximum range of (less than worldwide), its submarine-based forces extend its reach from a coastline inland. Additionally,

The current delivery systems of the U.S. make virtually any part of the Earth's surface within the reach of its nuclear arsenal. Though its land-based missile systems have a maximum range of (less than worldwide), its submarine-based forces extend its reach from a coastline inland. Additionally,

The United States nuclear program since its inception has experienced accidents of varying forms, ranging from single-casualty research experiments (such as that of

The United States nuclear program since its inception has experienced accidents of varying forms, ranging from single-casualty research experiments (such as that of

After A Nuclear 9/11

''The Washington Post'', 25 March 2008. and there is concern about the possible detonation of a small, crude nuclear weapon by a

Averting Catastrophe: Why the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty is Losing its Deterrence Capacity and How to Restore It

22 May 2007, p. 338.Nicholas D. Kristof

''The New York Times'', 10 March 2004.

The initial U.S. nuclear program was run by the

The initial U.S. nuclear program was run by the

Early on in the development of its nuclear weapons, the United States relied in part on information-sharing with both the United Kingdom and Canada, as codified in the

Early on in the development of its nuclear weapons, the United States relied in part on information-sharing with both the United Kingdom and Canada, as codified in the

In 1958, the United States Air Force had considered a plan to drop nuclear bombs on China during a confrontation over

In 1958, the United States Air Force had considered a plan to drop nuclear bombs on China during a confrontation over

The United States is one of the five recognized nuclear powers by the signatories of the

The United States is one of the five recognized nuclear powers by the signatories of the

In the early 1980s, the revival of the

In the early 1980s, the revival of the

The Spirit of June 12

''The Nation'', 2 July 2007. International Day of Nuclear Disarmament protests were held on 20 June 1983 at 50 sites across the United States.1,400 Anti-nuclear protesters arrested

''Miami Herald'', 21 June 1983. There were many

438 Protesters are Arrested at Nevada Nuclear Test Site

''New York Times'', 6 February 1987.

''New York Times'', 20 April 1992. There have also been protests by anti-nuclear groups at the Y-12 Nuclear Weapons Plant,Stop the Bombs! April 2010 Action Event at Y-12 Nuclear Weapons Complex

the

Keep Yellowstone Nuclear Free

Yucca Mountain nuclear waste repository proposal,Sierra Club. (undated)

Deadly Nuclear Waste Transport

/ref> the

''New York Times'', 10 August 1989. Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory,

''The TriValley Herald'', 11 August 2003. and transportation of nuclear waste from the Los Alamos National Laboratory.Concerned Citizens for Nuclear Safety (undated)

/ref> On 1 May 2005, 40,000 anti-nuclear/anti-war protesters marched past the United Nations in New York, 60 years after the

Pictures: New York MayDay anti-nuke/war march

,

Fox News, 2 May 2005. This was the largest anti-nuclear rally in the U.S. for several decades. In May 2010, some 25,000 people, including members of peace organizations and 1945 atomic bomb survivors, marched from downtown New York to the United Nations headquarters, calling for the elimination of nuclear weapons.A-bomb survivors join 25,000-strong anti-nuclear march through New York

''Mainichi Daily News'', 4 May 2010. Some scientists and engineers have opposed nuclear weapons, including

50 Facts About U.S. Nuclear Weapons , Brookings Institution

* Weart, Spencer R. ''Nuclear Fear: A History of Images.'' Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1985. * Woolf, Amy F

U.S. ''Strategic Nuclear Forces: Background, Developments, and Issues.''

Washington, D.C.:

"Presidency in the Nuclear Age"

conference and forum at the

* Video archive o

* Video archive o

US Nuclear Testing

a

sonicbomb.com

NDRC's data on the US Nuclear Stockpile, 1945–2002

by the

New nuclear warhead design for US

Annotated bibliography of U. S. nuclear weapons programs from the Alsos Digital Library for Nuclear Issues

US Test footage and veteran testimony

{{U.S. anti-nuclear Cold War history of the United States United States Atomic Energy Commission United States Department of Energy

United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

was the first country to manufacture nuclear weapon

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions ( thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bom ...

s and is the only country to have used them in combat

Combat ( French for ''fight'') is a purposeful violent conflict meant to physically harm or kill the opposition. Combat may be armed (using weapons) or unarmed ( not using weapons). Combat is sometimes resorted to as a method of self-defense, or ...

, with the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

The United States detonated two atomic bombs over the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on 6 and 9 August 1945, respectively. The two bombings killed between 129,000 and 226,000 people, most of whom were civilians, and remain the onl ...

in World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

. Before and during the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

, it conducted 1,054 nuclear tests

Nuclear weapons tests are experiments carried out to determine nuclear weapons' effectiveness, yield, and explosive capability. Testing nuclear weapons offers practical information about how the weapons function, how detonations are affected by ...

, and tested many long-range nuclear weapons delivery

Nuclear weapons delivery is the technology and systems used to place a nuclear weapon at the position of detonation, on or near its target. Several methods have been developed to carry out this task.

''Strategic'' nuclear weapons are used primari ...

systems.

Between 1940 and 1996, the U.S. Federal Government

The federal government of the United States (U.S. federal government or U.S. government) is the Federation#Federal governments, national government of the United States, a federal republic located primarily in North America, composed of 50 ...

spent at least US$

The United States dollar (symbol: $; code: USD; also abbreviated US$ or U.S. Dollar, to distinguish it from other dollar-denominated currencies; referred to as the dollar, U.S. dollar, American dollar, or colloquially buck) is the official ...

in present-day terms on nuclear weapons, including platforms development (aircraft, rockets and facilities), command and control, maintenance, waste

Waste (or wastes) are unwanted or unusable materials. Waste is any substance discarded after primary use, or is worthless, defective and of no use. A by-product, by contrast is a joint product of relatively minor economic value. A waste prod ...

management and administrative costs. It is estimated that the United States produced more than 70,000 nuclear warheads since 1945, more than all other nuclear weapon states combined. Until November 1962, the vast majority of U.S. nuclear test

Nuclear weapons tests are experiments carried out to determine nuclear weapons' effectiveness, yield, and explosive capability. Testing nuclear weapons offers practical information about how the weapons function, how detonations are affected by ...

s were above ground. After the acceptance of the Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty

The Partial Test Ban Treaty (PTBT) is the abbreviated name of the 1963 Treaty Banning Nuclear Weapon Tests in the Atmosphere, in Outer Space and Under Water, which prohibited all test detonations of nuclear weapons except for those conducted ...

, all testing was relegated underground, in order to prevent the dispersion of nuclear fallout

Nuclear fallout is the residual radioactive material propelled into the upper atmosphere following a nuclear blast, so called because it "falls out" of the sky after the explosion and the shock wave has passed. It commonly refers to the radioac ...

.

By 1998, at least US$759 million had been paid to the Marshall Islanders in compensation for their exposure to U.S. nuclear testing. – updated regularly By March 2021 over US$2.5 billion in compensation had been paid to U.S. citizens exposed to nuclear hazards as a result of the U.S. nuclear weapons program.

In 2019, the U.S. and Russia possessed a comparable number of nuclear warheads; together, these two nations possess more than 90% of the world's nuclear weapons stockpile. As of 2020, the United States had a stockpile of 3,750 active and inactive nuclear warheads plus approximately 2,000 warheads retired and awaiting dismantlement. Of the stockpiled warheads, the U.S. stated in its March 2019 New START

New START (Russian abbrev.: СНВ-III, ''SNV-III'' from ''сокращение стратегических наступательных вооружений'' "reduction of strategic offensive arms") is a nuclear arms reduction treaty between ...

declaration that 1,365 were deployed on 656 ICBM

An intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) is a ballistic missile with a range greater than , primarily designed for nuclear weapons delivery (delivering one or more thermonuclear warheads). Conventional, chemical, and biological weapons c ...

s, SLBM

A submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM) is a ballistic missile capable of being launched from Ballistic missile submarine, submarines. Modern variants usually deliver multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles (MIRVs), each of whic ...

s, and strategic bomber

A strategic bomber is a medium- to long-range penetration bomber aircraft designed to drop large amounts of air-to-ground weaponry onto a distant target for the purposes of debilitating the enemy's capacity to wage war. Unlike tactical bombers, ...

s.Fact Sheet: Nuclear Weapons: Who Has What at a GlanceArms Control Association (updated: July 2019).

Development history

Manhattan Project

The United States first began developing nuclear weapons during

The United States first began developing nuclear weapons during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

under the order of President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

*President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ful ...

Franklin Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

in 1939, motivated by the fear that they were engaged in a race with Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

to develop such a weapon. After a slow start under the direction of the National Bureau of Standards

The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) is an agency of the United States Department of Commerce whose mission is to promote American innovation and industrial competitiveness. NIST's activities are organized into physical sci ...

, at the urging of British scientists and American administrators, the program was put under the Office of Scientific Research and Development

The Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD) was an agency of the United States federal government created to coordinate scientific research for military purposes during World War II. Arrangements were made for its creation during May 1 ...

, and in 1942 it was officially transferred under the auspices of the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cla ...

and became known as the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

, an American, British and Canadian joint venture. Under the direction of General

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of highest military ranks, high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers t ...

Leslie Groves

Lieutenant General Leslie Richard Groves Jr. (17 August 1896 – 13 July 1970) was a United States Army Corps of Engineers officer who oversaw the construction of the Pentagon and directed the Manhattan Project, a top secret research project ...

, over thirty different sites were constructed for the research, production, and testing of components related to bomb-making. These included the Los Alamos National Laboratory

Los Alamos National Laboratory (often shortened as Los Alamos and LANL) is one of the sixteen research and development laboratories of the United States Department of Energy (DOE), located a short distance northwest of Santa Fe, New Mexico, ...

at Los Alamos, New Mexico

Los Alamos is an census-designated place in Los Alamos County, New Mexico, United States, that is recognized as the development and creation place of the atomic bomb—the primary objective of the Manhattan Project by Los Alamos National Labora ...

, under the direction of physicist Robert Oppenheimer

J. Robert Oppenheimer (; April 22, 1904 – February 18, 1967) was an American theoretical physicist. A professor of physics at the University of California, Berkeley, Oppenheimer was the wartime head of the Los Alamos Laboratory and is often ...

, the Hanford plutonium

Plutonium is a radioactive chemical element with the symbol Pu and atomic number 94. It is an actinide metal of silvery-gray appearance that tarnishes when exposed to air, and forms a dull coating when oxidized. The element normally exhibi ...

production facility in Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered on ...

, and the Y-12 National Security Complex

The Y-12 National Security Complex is a United States Department of Energy National Nuclear Security Administration facility located in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, near the Oak Ridge National Laboratory. It was built as part of the Manhattan Proje ...

in Tennessee

Tennessee ( , ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked state in the Southeastern region of the United States. Tennessee is the 36th-largest by area and the 15th-most populous of the 50 states. It is bordered by Kentucky to th ...

.

By investing heavily in breeding plutonium in early nuclear reactor

A nuclear reactor is a device used to initiate and control a fission nuclear chain reaction or nuclear fusion reactions. Nuclear reactors are used at nuclear power plants for electricity generation and in nuclear marine propulsion. Heat from nu ...

s and in the electromagnetic and gaseous diffusion enrichment processes for the production of uranium-235

Uranium-235 (235U or U-235) is an isotope of uranium making up about 0.72% of natural uranium. Unlike the predominant isotope uranium-238, it is fissile, i.e., it can sustain a nuclear chain reaction. It is the only fissile isotope that exis ...

, the United States was able to develop three usable weapons by mid-1945. The Trinity test

Trinity was the code name of the first detonation of a nuclear weapon. It was conducted by the United States Army at 5:29 a.m. on July 16, 1945, as part of the Manhattan Project. The test was conducted in the Jornada del Muerto desert ab ...

was a plutonium implosion-design weapon tested on 16 July 1945, with around a 20 kiloton

TNT equivalent is a convention for expressing energy, typically used to describe the energy released in an explosion. The is a unit of energy defined by that convention to be , which is the approximate energy released in the detonation of a t ...

yield.

Faced with a planned invasion of the Japanese home islands scheduled to begin on 1 November 1945 and with Japan not surrendering, President Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. A leader of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 34th vice president from January to April 1945 under Franklin ...

ordered the atomic raids on Japan. On 6 August 1945, the U.S. detonated a uranium- gun design bomb, Little Boy

"Little Boy" was the type of atomic bomb dropped on the Japanese city of Hiroshima on 6 August 1945 during World War II, making it the first nuclear weapon used in warfare. The bomb was dropped by the Boeing B-29 Superfortress ''Enola Gay'' p ...

, over the Japanese city of Hiroshima

is the capital of Hiroshima Prefecture in Japan. , the city had an estimated population of 1,199,391. The gross domestic product (GDP) in Greater Hiroshima, Hiroshima Urban Employment Area, was US$61.3 billion as of 2010. Kazumi Matsui h ...

with an energy of about 15 kilotons of TNT, killing approximately 70,000 people, among them 20,000 Japanese combatant

Combatant is the legal status of an individual who has the right to engage in hostilities during an armed conflict. The legal definition of "combatant" is found at article 43(2) of Additional Protocol I (AP1) to the Geneva Conventions of 1949. It ...

s and 20,000 Korean slave laborers, and destroying nearly 50,000 buildings (including the 2nd General Army

''Dai-ni Sōgun''

, image =

, caption =

, dates = April 8, 1945-November 30, 1945

, country = Empire of Japan

, allegiance = Empe ...

and Fifth Division headquarters

Headquarters (commonly referred to as HQ) denotes the location where most, if not all, of the important functions of an organization are coordinated. In the United States, the corporate headquarters represents the entity at the center or the to ...

). Three days later, on 9 August, the U.S. attacked Nagasaki

is the capital and the largest city of Nagasaki Prefecture on the island of Kyushu in Japan.

It became the sole port used for trade with the Portuguese and Dutch during the 16th through 19th centuries. The Hidden Christian Sites in the ...

using a plutonium implosion-design bomb, Fat Man

"Fat Man" (also known as Mark III) is the codename for the type of nuclear bomb the United States detonated over the Japanese city of Nagasaki on 9 August 1945. It was the second of the only two nuclear weapons ever used in warfare, the fir ...

, with the explosion equivalent to about 20 kilotons of TNT, destroying 60% of the city and killing approximately 35,000 people, among them 23,200–28,200 Japanese munitions workers, 2,000 Korean slave laborers, and 150 Japanese combatants.

On 1 January 1947, the Atomic Energy Act of 1946

The Atomic Energy Act of 1946 (McMahon Act) determined how the United States would control and manage the nuclear technology it had jointly developed with its World War II allies, the United Kingdom and Canada. Most significantly, the Act rule ...

(known as the McMahon Act) took effect, and the Manhattan Project was officially turned over to the United States Atomic Energy Commission

The United States Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) was an agency of the United States government established after World War II by U.S. Congress to foster and control the peacetime development of atomic science and technology. President H ...

(AEC).

On 15 August 1947, the Manhattan Project was abolished.

During the Cold War

The American atomic stockpile was small and grew slowly in the immediate aftermath of World War II, and the size of that stockpile was a closely guarded secret. However, there were forces that pushed the United States towards greatly increasing the size of the stockpile. Some of these were international in origin and focused on the increasing tensions of theCold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

, including the loss of China In American political discourse, the "loss of China" is the unexpected Chinese Communist Party Chinese Communist Revolution, takeover of mainland China from the U.S.-backed Chinese Kuomintang government in 1949 and therefore the "loss of China to co ...

, the Soviet Union becoming an atomic power, and the onset of the Korean War

, date = {{Ubl, 25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953 (''de facto'')({{Age in years, months, weeks and days, month1=6, day1=25, year1=1950, month2=7, day2=27, year2=1953), 25 June 1950 – present (''de jure'')({{Age in years, months, weeks a ...

. And some of the forces were domestic – both the Truman administration

Harry S. Truman's tenure as the 33rd president of the United States began on April 12, 1945, upon the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt, and ended on January 20, 1953. He had been vice president for only days. A Democrat from Missouri, he ran fo ...

and the Eisenhower administration

Dwight D. Eisenhower's tenure as the 34th president of the United States began with his first inauguration on January 20, 1953, and ended on January 20, 1961. Eisenhower, a Republican from Kansas, took office following a landslide victory ov ...

wanted to rein in military spending and avoid budget deficits and inflation. It was the perception that nuclear weapons gave more "bang for the buck

"Bang for the buck" is an idiom meaning the worth of one's money or exertion. The phrase originated from the slang usage of the words "bang" which means "excitement" and "buck" which means "money". Variations of the term include "bang for your buc ...

" and thus were the most cost-efficient way to respond to the security threat the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

represented.

As a result, beginning in 1950 the AEC embarked on a massive expansion of its production facilities, an effort that would eventually be one of the largest U.S. government construction projects ever to take place outside of wartime. And this production would soon include the far more powerful hydrogen bomb

A thermonuclear weapon, fusion weapon or hydrogen bomb (H bomb) is a second-generation nuclear weapon design. Its greater sophistication affords it vastly greater destructive power than first-generation nuclear bombs, a more compact size, a lowe ...

, which the United States had decided to move forward with after an intense debate during 1949–50. as well as much smaller tactical atomic weapons for battlefield use.

By 1990, the United States had produced more than 70,000 nuclear warheads, in over 65 different varieties, ranging in yield from around .01 kilotons (such as the man-portable Davy Crockett shell) to the 25 megaton B41 bomb. Between 1940 and 1996, the U.S. spent at least $ in present-day terms on nuclear weapons development. Over half was spent on building delivery mechanisms for the weapon. $ in present-day terms was spent on nuclear waste

Radioactive waste is a type of hazardous waste that contains radioactive material. Radioactive waste is a result of many activities, including nuclear medicine, nuclear research, nuclear power generation, rare-earth mining, and nuclear weapons r ...

management and environmental remediation.

Richland, Washington

Richland () is a city in Benton County, Washington, United States. It is located in southeastern Washington at the confluence of the Yakima and the Columbia Rivers. As of the 2020 census, the city's population was 60,560. Along with the nearby c ...

was the first city established to support plutonium production at the nearby Hanford nuclear site

The Hanford Site is a decommissioned nuclear production complex operated by the United States federal government on the Columbia River in Benton County, Washington, Benton County in the U.S. state of Washington (state), Washington. The site h ...

, to power the American nuclear weapons arsenals. It produced plutonium

Plutonium is a radioactive chemical element with the symbol Pu and atomic number 94. It is an actinide metal of silvery-gray appearance that tarnishes when exposed to air, and forms a dull coating when oxidized. The element normally exhibi ...

for use in cold war

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

atomic bombs

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions ( thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bomb ...

.

Throughout the Cold War, the U.S. and USSR threatened with all-out nuclear attack in case of war, regardless of whether it was a conventional or a nuclear clash. U.S. nuclear doctrine called for mutually assured destruction

Mutual assured destruction (MAD) is a doctrine of military strategy and national security policy which posits that a full-scale use of nuclear weapons by an attacker on a nuclear-armed defender with second-strike capabilities would cause the ...

(MAD), which entailed a massive nuclear attack against strategic targets and major populations centers of the Soviet Union and its allies. The term "mutual assured destruction" was coined in 1962 by American strategist Donald Brennan. MAD was implemented by deploying nuclear weapons simultaneously on three different types of weapons platforms.

Post–Cold War

After the 1989 end of theCold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

and the 1991 dissolution

Dissolution may refer to:

Arts and entertainment Books

* ''Dissolution'' (''Forgotten Realms'' novel), a 2002 fantasy novel by Richard Lee Byers

* ''Dissolution'' (Sansom novel), a 2003 historical novel by C. J. Sansom Music

* Dissolution, in mu ...

of the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

, the U.S. nuclear program was heavily curtailed, halting its program of nuclear testing, ceasing its production of new nuclear weapons, and reducing its stockpile by half by the mid-1990s under President Bill Clinton

William Jefferson Clinton ( né Blythe III; born August 19, 1946) is an American politician who served as the 42nd president of the United States from 1993 to 2001. He previously served as governor of Arkansas from 1979 to 1981 and agai ...

. Many former nuclear facilities were shut down, and their sites became targets of extensive environmental remediation. Efforts were redirected from weapons production to stockpile stewardship

Stockpile stewardship refers to the United States program of reliability testing and maintenance of its nuclear weapons without the use of nuclear testing.

Because no new nuclear weapons have been developed by the United States since 1992, even i ...

, attempting to predict the behavior of aging weapons without using full-scale nuclear testing. Increased funding was also put into anti-nuclear proliferation

Nuclear proliferation is the spread of nuclear weapons, fissionable material, and weapons-applicable nuclear technology and information to nations not recognized as " Nuclear Weapon States" by the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Wea ...

programs, such as helping the states of the former Soviet Union to eliminate their former nuclear sites and to assist Russia in their efforts to inventory and secure their inherited nuclear stockpile. By February 2006, over $1.2 billion had been paid under the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act

The United States Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA) is a federal statute providing for the monetary compensation of people, including atomic veterans, who contracted cancer and a number of other specified diseases as a direct result of t ...

of 1990 to U.S. citizens exposed to nuclear hazards as a result of the U.S. nuclear weapons program, and by 1998 at least $759 million had been paid to the Marshall Islanders in compensation for their exposure to U.S. nuclear testing, and over $15 million was paid to the Japanese government

The Government of Japan consists of legislative, executive and judiciary branches and is based on popular sovereignty. The Government runs under the framework established by the Constitution of Japan, adopted in 1947. It is a unitary state, c ...

following the exposure of its citizens and food supply to nuclear fallout

Nuclear fallout is the residual radioactive material propelled into the upper atmosphere following a nuclear blast, so called because it "falls out" of the sky after the explosion and the shock wave has passed. It commonly refers to the radioac ...

from the 1954 "Bravo" test. In 1998, the country spent an estimated total of $35.1 billion on its nuclear weapons and weapons-related programs.

In the 2013 book '' Plutopia: Nuclear Families, Atomic Cities, and the Great Soviet and American Plutonium Disasters'' (Oxford),

In the 2013 book '' Plutopia: Nuclear Families, Atomic Cities, and the Great Soviet and American Plutonium Disasters'' (Oxford), Kate Brown

Katherine Brown (born June 21, 1960) is an American politician and attorney serving as the 38th governor of Oregon since 2015. A member of the Democratic Party, she served three terms as the state representative from the 13th district of the ...

explores the health of affected citizens in the United States, and the "slow-motion disasters" that still threaten the environments where the plants are located. According to Brown, the plants at Hanford, over a period of four decades, released millions of curies of radioactive isotopes into the surrounding environment. Brown says that most of this radioactive contamination

Radioactive contamination, also called radiological pollution, is the deposition of, or presence of radioactive substances on surfaces or within solids, liquids, or gases (including the human body), where their presence is unintended or undesirab ...

over the years at Hanford were part of normal operations, but unforeseen accidents did occur and plant management kept this secret, as the pollution continued unabated. Even today, as pollution threats to health and the environment persist, the government keeps knowledge about the associated risks from the public.

During the presidency of George W. Bush

George Walker Bush (born July 6, 1946) is an American politician who served as the 43rd president of the United States from 2001 to 2009. A member of the Republican Party, Bush family, and son of the 41st president George H. W. Bush, he ...

, and especially after the 11 September terrorist

Terrorism, in its broadest sense, is the use of criminal violence to provoke a state of terror or fear, mostly with the intention to achieve political or religious aims. The term is used in this regard primarily to refer to intentional violen ...

attacks of 2001, rumors circulated in major news sources that the U.S. was considering designing new nuclear weapons ( "bunker-busting nukes") and resuming nuclear testing for reasons of stockpile stewardship. Republicans argued that small nuclear weapons appear more likely to be used than large nuclear weapons, and thus small nuclear weapons pose a more credible threat that has more of a deterrent effect against hostile behavior. Democrats counterargued that allowing the weapons could trigger an arms race. In 2003, the Senate Armed Services Committee voted to repeal the 1993 Spratt- Furse ban on the development of small nuclear weapons. This change was part of the 2004 fiscal year defense authorization. The Bush administration wanted the repeal so that they could develop weapons to address the threat from North Korea. "Low-yield weapons" (those with one-third the force of the bomb that was dropped on Hiroshima in 1945) were permitted to be developed. The Bush Administration was unsuccessful in its goal to develop a guided low-yield nuclear weapon, however, in 2010 proceeding President Barack Obama began funding and development to what would become the B61-12, a smart guided low-yield nuclear bomb developed off of the B61 “dumb bomb”.

Statements by the U.S. government in 2004 indicated that they planned to decrease the arsenal to around 5,500 total warheads by 2012. Much of that reduction was already accomplished by January 2008.

According to the Pentagon's June 2019 Doctrine for Joint Nuclear Operations

The Doctrine for Joint Nuclear Operations was a U.S. Department of Defense document publicly discovered in 2005 on the circumstances under which commanders of U.S. forces could request the use of nuclear weapons. The document was a draft being revi ...

, "Integration of nuclear weapons employment with conventional and special operations forces is essential to the success of any mission or operation."

Nuclear weapons testing

Between 16 July 1945 and 23 September 1992, the United States maintained a program of vigorous

Between 16 July 1945 and 23 September 1992, the United States maintained a program of vigorous nuclear testing

Nuclear weapons tests are experiments carried out to determine nuclear weapons' effectiveness, yield, and explosive capability. Testing nuclear weapons offers practical information about how the weapons function, how detonations are affected by ...

, with the exception of a moratorium between November 1958 and September 1961. By official count, a total of 1,054 nuclear tests and two nuclear attacks were conducted, with over 100 of them taking place at sites in the Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the continen ...

, over 900 of them at the Nevada Test Site

The Nevada National Security Site (N2S2 or NNSS), known as the Nevada Test Site (NTS) until 2010, is a United States Department of Energy (DOE) reservation located in southeastern Nye County, Nevada, about 65 miles (105 km) northwest of th ...

, and ten on miscellaneous sites in the United States (Alaska

Alaska ( ; russian: Аляска, Alyaska; ale, Alax̂sxax̂; ; ems, Alas'kaaq; Yup'ik: ''Alaskaq''; tli, Anáaski) is a state located in the Western United States on the northwest extremity of North America. A semi-exclave of the U.S., ...

, Colorado

Colorado (, other variants) is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It encompasses most of the Southern Rocky Mountains, as well as the northeastern portion of the Colorado Plateau and the western edge of t ...

, Mississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Miss ...

, and New Mexico

)

, population_demonym = New Mexican ( es, Neomexicano, Neomejicano, Nuevo Mexicano)

, seat = Santa Fe

, LargestCity = Albuquerque

, LargestMetro = Tiguex

, OfficialLang = None

, Languages = English, Spanish ( New Mexican), Navajo, Ker ...

). Until November 1962, the vast majority of the U.S. tests were atmospheric (that is, above-ground); after the acceptance of the Partial Test Ban Treaty all testing was relegated underground, in order to prevent the dispersion of nuclear fallout

Nuclear fallout is the residual radioactive material propelled into the upper atmosphere following a nuclear blast, so called because it "falls out" of the sky after the explosion and the shock wave has passed. It commonly refers to the radioac ...

.

The U.S. program of atmospheric nuclear testing exposed a number of the population to the hazards of fallout. Estimating exact numbers, and the exact consequences, of people exposed has been medically very difficult, with the exception of the high exposures of Marshall Islanders and Japanese fishers in the case of the Castle Bravo

Castle Bravo was the first in a series of high-yield thermonuclear weapon design tests conducted by the United States at Bikini Atoll, Marshall Islands, as part of ''Operation Castle''. Detonated on March 1, 1954, the device was the most powerful ...

incident in 1954. A number of groups of U.S. citizens—especially farmers and inhabitants of cities downwind of the Nevada Test Site and U.S. military workers at various tests—have sued for compensation and recognition of their exposure, many successfully. The passage of the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act of 1990 allowed for a systematic filing of compensation claims in relation to testing as well as those employed at nuclear weapons facilities. By June 2009 over $1.4 billion total has been given in compensation, with over $660 million going to "downwinders

Downwinders were individuals and communities in the intermountain area between the Cascade and Rocky Mountain ranges primarily in Arizona, Nevada, New Mexico and Utah but also in Oregon, Washington, and Idaho who were exposed to radioactive contam ...

".

A few notable U.S. nuclear tests include:

* Trinity test

Trinity was the code name of the first detonation of a nuclear weapon. It was conducted by the United States Army at 5:29 a.m. on July 16, 1945, as part of the Manhattan Project. The test was conducted in the Jornada del Muerto desert ab ...

on 16 July 1945, was the world's first test of a nuclear weapon (yield of around 20 kt).

* Operation Crossroads

Operation Crossroads was a pair of nuclear weapon tests conducted by the United States at Bikini Atoll in mid-1946. They were the first nuclear weapon tests since Trinity in July 1945, and the first detonations of nuclear devices since the ...

series in July 1946, was the first postwar test series and one of the largest military operations in U.S. history.

* Operation Greenhouse

Operation Greenhouse was the fifth American nuclear test series, the second conducted in 1951 and the first to test principles that would lead to developing thermonuclear weapons (''hydrogen bombs''). Conducted at the new Pacific Proving Grou ...

shots of May 1951 included the first boosted fission weapon

A boosted fission weapon usually refers to a type of nuclear bomb that uses a small amount of fusion fuel to increase the rate, and thus yield, of a fission reaction. The neutrons released by the fusion reactions add to the neutrons released du ...

test ("Item") and a scientific test that proved the feasibility of thermonuclear weapons ("George").

* Ivy Mike

Ivy Mike was the codename given to the first full-scale test of a thermonuclear device, in which part of the explosive yield comes from nuclear fusion.

Ivy Mike was detonated on November 1, 1952, by the United States on the island of Elugelab in ...

shot of 1 November 1952, was the first full test of a Teller-Ulam design

A thermonuclear weapon, fusion weapon or hydrogen bomb (H bomb) is a second-generation nuclear weapon design. Its greater sophistication affords it vastly greater destructive power than first-generation nuclear bombs, a more compact size, a lowe ...

"staged" hydrogen bomb, with a yield of 10 megatons. It was not a deployable weapon, however—with its full cryogenic

In physics, cryogenics is the production and behaviour of materials at very low temperatures.

The 13th IIR International Congress of Refrigeration (held in Washington DC in 1971) endorsed a universal definition of “cryogenics” and “cr ...

equipment it weighed some 82 tons.

* Castle Bravo

Castle Bravo was the first in a series of high-yield thermonuclear weapon design tests conducted by the United States at Bikini Atoll, Marshall Islands, as part of ''Operation Castle''. Detonated on March 1, 1954, the device was the most powerful ...

shot of 1 March 1954, was the first test of a deployable (solid fuel) thermonuclear weapon, and also (accidentally) the largest weapon ever tested by the United States (15 megatons). It was also the single largest U.S. radiological accident in connection with nuclear testing. The unanticipated yield, and a change in the weather, resulted in nuclear fallout spreading eastward onto the inhabited Rongelap

Rongelap Atoll ( Marshallese: , ) is a coral atoll of 61 islands (or motus) in the Pacific Ocean, and forms a legislative district of the Ralik Chain of the Marshall Islands. Its total land area is . It encloses a lagoon with an area of . ...

and Rongerik

Rongerik Atoll or Rongdrik Atoll ( Marshallese: , ) is a coral atoll of 17 islands in the Pacific Ocean, and is located in the Ralik Chain of the Marshall Islands, approximately east of Bikini Atoll. Its total land area is only , but it encloses ...

atolls, which were soon evacuated. Many of the Marshall Islanders have since suffered from birth defects

A birth defect, also known as a congenital disorder, is an abnormal condition that is present at birth regardless of its cause. Birth defects may result in disabilities that may be physical, intellectual, or developmental. The disabilities can ...

and have received some compensation from the federal government. A Japanese fishing boat, ''Daigo Fukuryū Maru

was a Japanese tuna fishing boat with a crew of 23 men which was contaminated by nuclear fallout from the United States Castle Bravo thermonuclear weapon test at Bikini Atoll on March 1, 1954.

The crew suffered acute radiation syndrome (ARS) ...

'', also came into contact with the fallout, which caused many of the crew to grow ill; one eventually died.

* Shot Argus I of Operation Argus

Operation Argus was a series of United States low-yield, high-altitude nuclear weapons tests and missile tests secretly conducted from 27 August to 9 September 1958 over the South Atlantic Ocean. The tests were performed by the Defense Nucle ...

, on 27 August 1958, was the first detonation of a nuclear weapon in outer space

Outer space, commonly shortened to space, is the expanse that exists beyond Earth and its atmosphere and between celestial bodies. Outer space is not completely empty—it is a near-perfect vacuum containing a low density of particles, pred ...

when a 1.7-kiloton warhead was detonated at an altitude of during a series of high altitude nuclear explosion

High-altitude nuclear explosions are the result of nuclear weapons testing within the upper layers of the Earth's atmosphere and in outer space. Several such tests were performed at high altitudes by the United States and the Soviet Union betwe ...

s.

* Shot Frigate Bird of Operation Dominic I on 6 May 1962, was the only U.S. test of an operational submarine-launched ballistic missile

A submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM) is a ballistic missile capable of being launched from submarines. Modern variants usually deliver multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles (MIRVs), each of which carries a nuclear warhead ...

(SLBM) with a live nuclear warhead (yield of 600 kilotons), at Christmas Island

Christmas Island, officially the Territory of Christmas Island, is an Australian external territory comprising the island of the same name. It is located in the Indian Ocean, around south of Java and Sumatra and around north-west of the ...

. In general, missile systems were tested without live warheads and warheads were tested separately for safety concerns. In the early 1960s, however, there mounted technical questions about how the systems would behave under combat conditions (when they were "mated", in military parlance), and this test was meant to dispel these concerns. However, the warhead had to be somewhat modified before its use, and the missile was a SLBM

A submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM) is a ballistic missile capable of being launched from Ballistic missile submarine, submarines. Modern variants usually deliver multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles (MIRVs), each of whic ...

(and not an ICBM

An intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) is a ballistic missile with a range greater than , primarily designed for nuclear weapons delivery (delivering one or more thermonuclear warheads). Conventional, chemical, and biological weapons c ...

), so by itself it did not satisfy all concerns.

* Shot Sedan of Operation Storax

Operation Storax was a series of 47 nuclear tests conducted by the United States in 1962–1963 at the Nevada Test Site. These tests followed the ''Operation Fishbowl'' series and preceded the ''Operation Roller Coaster'' series.

British test ...

on 6 July 1962 (yield of 104 kilotons), was an attempt to show the feasibility of using nuclear weapons for "civilian" and "peaceful" purposes as part of Operation Plowshare

Project Plowshare was the overall United States program for the development of techniques to use nuclear explosives for peaceful construction purposes. The program was organized in June 1957 as part of the worldwide Atoms for Peace efforts. As ...

. In this instance, a diameter deep crater

Crater may refer to:

Landforms

*Impact crater, a depression caused by two celestial bodies impacting each other, such as a meteorite hitting a planet

*Explosion crater, a hole formed in the ground produced by an explosion near or below the surfac ...

was created at the Nevada Test Site.

A summary table of each of the American operational series may be found at United States' nuclear test series

The nuclear weapons tests of the United States were performed from 1945 to 1992 as part of the nuclear arms race. The United States conducted around 1,054 nuclear tests by official count, including 216 atmospheric, underwater, and space tests.Di ...

.

Delivery systems

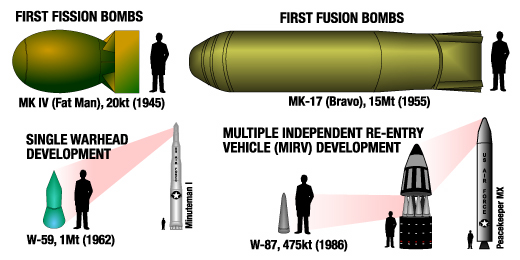

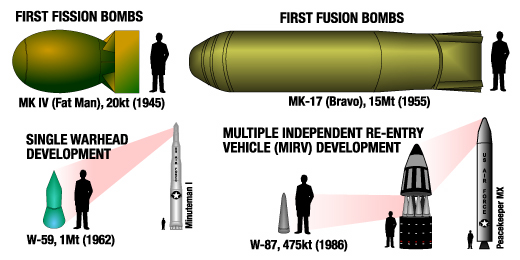

The original Little Boy and Fat Man weapons, developed by the United States during the

The original Little Boy and Fat Man weapons, developed by the United States during the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

, were relatively large (Fat Man had a diameter of ) and heavy (around 5 tons each) and required specially modified bomber planes to be adapted for their bombing missions against Japan. Each modified bomber could only carry one such weapon and only within a limited range. After these initial weapons were developed, a considerable amount of money and research was conducted towards the goal of standardizing nuclear warheads so that they did not require highly specialized experts to assemble them before use, as in the case with the idiosyncratic

An idiosyncrasy is an unusual feature of a person (though there are also other uses, see below). It can also mean an odd habit. The term is often used to express eccentricity or peculiarity. A synonym may be "quirk".

Etymology

The term "idiosyncra ...

wartime devices, and miniaturization of the warheads for use in more variable delivery systems.

Through the aid of brainpower acquired through Operation Paperclip

Operation Paperclip was a secret United States intelligence program in which more than 1,600 German scientists, engineers, and technicians were taken from the former Nazi Germany to the U.S. for government employment after the end of World Wa ...

at the tail end of the European theater of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, the United States was able to embark on an ambitious program in rocket

A rocket (from it, rocchetto, , bobbin/spool) is a vehicle that uses jet propulsion to accelerate without using the surrounding air. A rocket engine produces thrust by reaction to exhaust expelled at high speed. Rocket engines work entirely fr ...

ry. One of the first products of this was the development of rockets capable of holding nuclear warheads. The MGR-1 Honest John

The MGR-1 Honest John rocket was the first nuclear-capable surface-to-surface rocket in the United States arsenal.The first nuclear-authorized ''guided'' missile was the MGM-5 Corporal. Originally designated Artillery Rocket XM31, the first un ...

was the first such weapon, developed in 1953 as a surface-to-surface missile with a maximum range. Because of their limited range, their potential use was heavily constrained (they could not, for example, threaten Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

with an immediate strike).

Development of long-range bombers, such as the

Development of long-range bombers, such as the B-29 Superfortress

The Boeing B-29 Superfortress is an American four-engined propeller-driven heavy bomber, designed by Boeing and flown primarily by the United States during World War II and the Korean War. Named in allusion to its predecessor, the B-17 Fl ...

during World War II, was continued during the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

period. In 1946, the Convair B-36 Peacemaker

The Convair B-36 "Peacemaker" is a strategic bomber that was built by Convair and operated by the United States Air Force (USAF) from 1949 to 1959. The B-36 is the largest mass-produced piston-engined aircraft ever built. It had the longest win ...

became the first purpose-built nuclear bomber; it served with the USAF until 1959. The Boeing B-52 Stratofortress

The Boeing B-52 Stratofortress is an American long-range, subsonic, jet-powered strategic bomber. The B-52 was designed and built by Boeing, which has continued to provide support and upgrades. It has been operated by the United States Air ...

was able by the mid-1950s to carry a wide arsenal of nuclear bombs, each with different capabilities and potential use situations. Starting in 1946, the U.S. based its initial deterrence force on the Strategic Air Command

Strategic Air Command (SAC) was both a United States Department of Defense Specified Command and a United States Air Force (USAF) Major Command responsible for command and control of the strategic bomber and intercontinental ballistic missile ...

, which, by the late 1950s, maintained a number of nuclear-armed bombers in the sky at all times, prepared to receive orders to attack the USSR whenever needed. This system was, however, tremendously expensive, both in terms of natural and human resources, and raised the possibility of an accidental nuclear war.

During the 1950s and 1960s, elaborate computerized early warning systems such as Defense Support Program

The Defense Support Program (DSP) is a program of the United States Space Force that operated the reconnaissance satellites which form the principal component of the ''Satellite Early Warning System'' used by the United States.

DSP satellite ...

were developed to detect incoming Soviet attacks and to coordinate response strategies. During this same period, intercontinental ballistic missile

An intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) is a ballistic missile with a range greater than , primarily designed for nuclear weapons delivery (delivering one or more thermonuclear warheads). Conventional, chemical, and biological weapons c ...

(ICBM) systems were developed that could deliver a nuclear payload across vast distances, allowing the U.S. to house nuclear forces capable of hitting the Soviet Union in the American Midwest

The Midwestern United States, also referred to as the Midwest or the American Midwest, is one of four census regions of the United States Census Bureau (also known as "Region 2"). It occupies the northern central part of the United States. I ...

. Shorter-range weapons, including small tactical weapons, were fielded in Europe as well, including nuclear artillery

Nuclear artillery is a subset of limited- yield tactical nuclear weapons, in particular those weapons that are launched from the ground at battlefield targets. Nuclear artillery is commonly associated with shells delivered by a cannon, but in ...

and man-portable Special Atomic Demolition Munition

The Special Atomic Demolition Munition (SADM), also known as the XM129 and XM159 Atomic Demolition Charges, and the B54 bomb was a nuclear man-portable atomic demolition munition (ADM) system fielded by the US military from the 1960s to 1980s ...

. The development of submarine-launched ballistic missile systems allowed for hidden nuclear submarines

A nuclear submarine is a submarine powered by a nuclear reactor, but not necessarily nuclear-armed. Nuclear submarines have considerable performance advantages over "conventional" (typically diesel-electric) submarines. Nuclear propulsion, ...

to covertly launch missiles at distant targets as well, making it virtually impossible for the Soviet Union to successfully launch a first strike attack against the United States without receiving a deadly response.

Improvements in warhead miniaturization in the 1970s and 1980s allowed for the development of MIRVs—missiles which could carry multiple warheads, each of which could be separately targeted. The question of whether these missiles should be based on constantly rotating train tracks (to avoid being easily targeted by opposing Soviet missiles) or based in heavily fortified silos (to possibly withstand a Soviet attack) was a major political controversy in the 1980s (eventually the silo deployment method was chosen). MIRVed systems enabled the U.S. to render Soviet missile defenses economically unfeasible, as each offensive missile would require between three and ten defensive missiles to counter.

Additional developments in weapons delivery included cruise missile

A cruise missile is a guided missile used against terrestrial or naval targets that remains in the atmosphere and flies the major portion of its flight path at approximately constant speed. Cruise missiles are designed to deliver a large warhe ...

systems, which allowed a plane to fire a long-distance, low-flying nuclear-armed missile towards a target from a relatively comfortable distance.

The current delivery systems of the U.S. make virtually any part of the Earth's surface within the reach of its nuclear arsenal. Though its land-based missile systems have a maximum range of (less than worldwide), its submarine-based forces extend its reach from a coastline inland. Additionally,

The current delivery systems of the U.S. make virtually any part of the Earth's surface within the reach of its nuclear arsenal. Though its land-based missile systems have a maximum range of (less than worldwide), its submarine-based forces extend its reach from a coastline inland. Additionally, in-flight refueling

Aerial refueling, also referred to as air refueling, in-flight refueling (IFR), air-to-air refueling (AAR), and tanking, is the process of transferring aviation fuel from one aircraft (the tanker) to another (the receiver) while both aircraft a ...

of long-range bombers and the use of aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and facilities for carrying, arming, deploying, and recovering aircraft. Typically, it is the capital ship of a fleet, as it allows a ...

s extends the possible range virtually indefinitely.

Command and control

Command and control

Command and control (abbr. C2) is a "set of organizational and technical attributes and processes ... hatemploys human, physical, and information resources to solve problems and accomplish missions" to achieve the goals of an organization or en ...

procedures in case of nuclear war

Nuclear warfare, also known as atomic warfare, is a theoretical military conflict or prepared political strategy that deploys nuclear weaponry. Nuclear weapons are weapons of mass destruction; in contrast to conventional warfare, nuclear w ...

were given by the Single Integrated Operational Plan

The Single Integrated Operational Plan (SIOP) was the United States' general plan for nuclear war from 1961 to 2003. The SIOP gave the President of the United States a range of targeting options, and described launch procedures and target sets a ...

(SIOP) until 2003, when this was superseded by Operations Plan 8044.

Since World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, the President of the United States has had sole authority to launch U.S. nuclear weapons, whether as a first strike or nuclear retaliation. This arrangement was seen as necessary during the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

to present a credible nuclear deterrent

Nuclear strategy involves the development of doctrines and strategies for the production and use of nuclear weapons.

As a sub-branch of military strategy, nuclear strategy attempts to match nuclear weapons as means to political ends. In additi ...

; if an attack was detected, the United States would have only minutes to launch a counterstrike before its nuclear capability was severely damaged, or national leaders killed. If the President has been killed, command authority follows the presidential line of succession. Changes to this policy have been proposed, but currently the only way to countermand such an order before the strike was launched would be for the Vice President and the majority of the Cabinet to relieve the President under Section 4 of the Twenty-fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Twenty-fifth Amendment (Amendment XXV) to the United States Constitution deals with presidential succession and disability.

It clarifies that the vice president becomes president if the president dies, resigns, or is removed from office, a ...

.

Regardless of whether the United States is actually under attack by a nuclear-capable adversary, the President alone has the authority to order nuclear strikes. The President and the Secretary of Defense

A defence minister or minister of defence is a cabinet official position in charge of a ministry of defense, which regulates the armed forces in sovereign states. The role of a defence minister varies considerably from country to country; in som ...

form the National Command Authority, but the Secretary of Defense has no authority to refuse or disobey such an order. The President's decision must be transmitted to the National Military Command Center

The National Military Command Center (NMCC) is a Pentagon command and communications center for the National Command Authority (i.e., the President of the United States and the United States Secretary of Defense). Maintained by the Department o ...

, which will then issue the coded orders to nuclear-capable forces.

The President can give a nuclear launch order using their nuclear briefcase

A nuclear briefcase is a specially outfitted briefcase used to authorize the use of nuclear weapons and is usually kept near the leader of a nuclear weapons state at all times.

France

In France, the nuclear briefcase does not officially exist. A ...

(nicknamed the nuclear football

The nuclear football (also known as the atomic football, the president's emergency satchel, the Presidential Emergency Satchel, the button, the black box, or just the football) is a briefcase, the contents of which are to be used by the preside ...

), or can use command center

A command center (often called a war room) is any place that is used to provide centralized command for some purpose.

While frequently considered to be a military facility, these can be used in many other cases by governments or businesses. ...

s such as the White House Situation Room

The Situation Room, officially known as the John F. Kennedy Conference Room, is a conference room and intelligence management center in the basement of the West Wing of the White House. It is run by the National Security Council staff for the u ...

. The command would be carried out by a Nuclear and Missile Operations Officer (a member of a missile combat crew

A missile combat crew (MCC), is a team of highly trained specialists, often called missileers, staffing Intermediate Range and Intercontinental ballistic missile systems (IRBMs and ICBMs, respectively). In the United States, personnel, officially c ...

, also called a "missileer") at a missile launch control center

A launch control center (LCC), in the United States, is the main control facility for intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs). A launch control center monitors and controls missile launch facilities. From a launch control center, the missi ...

. A two-man rule

The two-man rule is a control mechanism designed to achieve a high level of security for especially critical material or operations. Under this rule, access and actions require the presence of two or more authorized people at all times.

United St ...

applies to the launch of missiles, meaning that two officers must turn keys simultaneously (far enough apart that this cannot be done by one person).

When President Reagan was shot in 1981, there was confusion about where the "nuclear football" was, and who was in charge.

In 1975, a launch crew member, Harold Hering

Harold L. Hering (born 1936) is a former officer of the United States Air Force, who was discharged in 1975 for requesting basic information about checks and balances to prevent an unauthorized order to launch nuclear missiles.Rosenbaum, Ron (Feb ...

, was dismissed from the Air Force for asking how he could know whether the order to launch his missiles came from a sane president. It has been claimed that the system is not foolproof.

Starting with President Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; ; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was an American military officer and statesman who served as the 34th president of the United States from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, ...

, authority to launch a full-scale nuclear attack has been delegated to theater commanders and other specific commanders if they believe it is warranted by circumstances, and are out of communication with the president or the president had been incapacitated.Stone, Oliver and Kuznick, Peter "The Untold History of the United States" (Gallery Books, 2012), pages 286–87 For example, during the Cuban Missile Crisis

The Cuban Missile Crisis, also known as the October Crisis (of 1962) ( es, Crisis de Octubre) in Cuba, the Caribbean Crisis () in Russia, or the Missile Scare, was a 35-day (16 October – 20 November 1962) confrontation between the United S ...

, on 24 October 1962, General Thomas Power, commander of the Strategic Air Command

Strategic Air Command (SAC) was both a United States Department of Defense Specified Command and a United States Air Force (USAF) Major Command responsible for command and control of the strategic bomber and intercontinental ballistic missile ...

(SAC), took the country to DEFCON 2, the very precipice of full-scale nuclear war, launching the SAC bombers of the US with nuclear weapons ready to strike. Moreover, some of these commanders subdelegated to lower commanders the authority to launch nuclear weapons under similar circumstance. In fact, the nuclear weapons were not placed under locks until decades later, so pilots or individual submarine commanders had the power, but not the authority, to launch nuclear weapons entirely on their own.

Accidents

The United States nuclear program since its inception has experienced accidents of varying forms, ranging from single-casualty research experiments (such as that of

The United States nuclear program since its inception has experienced accidents of varying forms, ranging from single-casualty research experiments (such as that of Louis Slotin

Louis Alexander Slotin (1 December 1910 – 30 May 1946) was a Canadian physicist and chemist who took part in the Manhattan Project. Born and raised in the North End of Winnipeg, Manitoba, Slotin earned both his Bachelor of Science and M ...

during the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

), to the nuclear fallout

Nuclear fallout is the residual radioactive material propelled into the upper atmosphere following a nuclear blast, so called because it "falls out" of the sky after the explosion and the shock wave has passed. It commonly refers to the radioac ...

dispersion of the Castle Bravo shot in 1954, to accidents such as crashes of aircraft carrying nuclear weapons, the dropping of nuclear weapons from aircraft, losses of nuclear submarines, and explosions of nuclear-armed missiles ( broken arrows). How close any of these accidents came to being major nuclear disasters is a matter of technical and scholarly debate and interpretation.

Weapons accidentally dropped by the United States include incidents off the coast of British Columbia

British Columbia (commonly abbreviated as BC) is the westernmost province of Canada, situated between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains. It has a diverse geography, with rugged landscapes that include rocky coastlines, sandy beaches, ...

(1950) (see 1950 British Columbia B-36 crash

Sometime after midnight on 14 February 1950, a Convair B-36B, United States Air Force Serial Number ''44-92075'' assigned to the US 7th Bombardment Wing, Heavy at Carswell Air Force Base in Texas, crashed in northwestern British Columbia on Mo ...

), near Atlantic City, New Jersey

Atlantic City, often known by its initials A.C., is a coastal resort city in Atlantic County, New Jersey, United States. The city is known for its casinos, boardwalk, and beaches. In 2020, the city had a population of 38,497.

(1957); Savannah, Georgia

Savannah ( ) is the oldest city in the U.S. state of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia and is the county seat of Chatham County, Georgia, Chatham County. Established in 1733 on the Savannah River, the city of Savannah became the Kingdom of Great Br ...

(1958) (see Tybee Bomb

The Tybee Island mid-air collision was an incident on February 5, 1958, in which the United States Air Force lost a Mark 15 nuclear bomb in the waters off Tybee Island near Savannah, Georgia, United States. During a practice exercise, an F-86 f ...

); Goldsboro, North Carolina

Goldsboro, originally Goldsborough, is a city and the county seat of Wayne County, North Carolina, United States. The population was 33,657 at the 2020 census. It is the principal city of and is included in the Goldsboro, North Carolina Metropol ...

(1961) (see 1961 Goldsboro B-52 crash

The 1961 Goldsboro B-52 crash was an accident that occurred near Goldsboro, North Carolina, on 23 January 1961. A Boeing B-52 Stratofortress carrying two 3–4-TNT equivalent#Kiloton and megaton, megaton Mark 39 nuclear bombs broke up in mid-air ...

); off the coast of Okinawa

is a prefecture of Japan. Okinawa Prefecture is the southernmost and westernmost prefecture of Japan, has a population of 1,457,162 (as of 2 February 2020) and a geographic area of 2,281 km2 (880 sq mi).

Naha is the capital and largest city ...

(1965); in the sea near Palomares, Spain (1966, see 1966 Palomares B-52 crash

The 1966 Palomares B-52 crash, also called the Palomares incident, occurred on 17 January 1966, when a B-52G bomber of the United States Air Force's Strategic Air Command collided with a KC-135 tanker during mid-air refueling at over the Me ...

); and near Thule Air Base

Thule Air Base (pronounced or , kl, Qaanaaq Mitarfik, da, Thule Lufthavn), or Thule Air Base/Pituffik Airport , is the United States Space Force's northernmost base, and the northernmost installation of the U.S. Armed Forces, located north o ...

, Greenland

Greenland ( kl, Kalaallit Nunaat, ; da, Grønland, ) is an island country in North America that is part of the Kingdom of Denmark. It is located between the Arctic and Atlantic oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Greenland is t ...

(1968) (see 1968 Thule Air Base B-52 crash

On 21 January 1968, an aircraft accident, sometimes known as the Thule affair or Thule accident (; da, Thuleulykken), involving a United States Air Force (USAF) B-52 bomber occurred near Thule Air Base in the Danish territory of Greenland. The ...

). In some of these cases (such as the 1966 Palomares case), the explosive system of the fission weapon discharged, but did not trigger a nuclear chain reaction

In nuclear physics, a nuclear chain reaction occurs when one single nuclear reaction causes an average of one or more subsequent nuclear reactions, thus leading to the possibility of a self-propagating series of these reactions. The specific nu ...

(safety features prevent this from easily happening), but did disperse hazardous nuclear materials across wide areas, necessitating expensive cleanup endeavors. Several US nuclear weapons, partial weapons, or weapons components are thought to be lost and unrecovered, primarily in aircraft accidents. The 1980 Damascus Titan missile explosion

The Damascus Titan missile explosion (also called the Damascus accident) was a 1980 U.S. nuclear weapons incident involving a Titan II Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM). The incident occurred on September 18–19, 1980, at Missile Comp ...

in Damascus, Arkansas

Damascus is a town in Faulkner and Van Buren counties of central Arkansas, United States. The population of Damascus was 382 at the 2010 census.

History

Damascus is a town located in the Oark foothills on a platea surrounded by clear streams al ...

, threw a warhead from its silo but did not release any radiation.

The nuclear testing program resulted in a number of cases of fallout dispersion onto populated areas. The most significant of these was the Castle Bravo

Castle Bravo was the first in a series of high-yield thermonuclear weapon design tests conducted by the United States at Bikini Atoll, Marshall Islands, as part of ''Operation Castle''. Detonated on March 1, 1954, the device was the most powerful ...

test, which spread radioactive ash over an area of over , including a number of populated islands. The populations of the islands were evacuated but not before suffering radiation burns. They would later suffer long-term effects, such as birth defect

A birth defect, also known as a congenital disorder, is an abnormal condition that is present at birth regardless of its cause. Birth defects may result in disabilities that may be physical, intellectual, or developmental. The disabilities can ...

s and increased cancer risk. There are ongoing concerns around deterioration of the nuclear waste site on Runit Island

Runit Island () is one of 40 islands of the Enewetak Atoll of the Marshall Islands in the Pacific Ocean. The island is the site of a radioactive waste repository left by the United States after it conducted a series of nuclear tests on Enewetak A ...

and a potential radioactive spill. There were also instances during the nuclear testing program in which soldiers were exposed to overly high levels of radiation, which grew into a major scandal in the 1970s and 1980s, as many soldiers later suffered from what were claimed to be diseases caused by their exposures.

Many of the former nuclear facilities produced significant environmental damages during their years of activity, and since the 1990s have been Superfund

Superfund is a United States federal environmental remediation program established by the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act of 1980 (CERCLA). The program is administered by the United States Environmental Pro ...

sites of cleanup and environmental remediation. Hanford is currently the most contaminated

Contamination is the presence of a constituent, impurity, or some other undesirable element that spoils, corrupts, infects, makes unfit, or makes inferior a material, physical body, natural environment, workplace, etc.

Types of contamination

Wi ...

nuclear site in the United States and is the focus of the nation's largest environmental cleanup

Environmental remediation deals with the removal of pollution or contaminants from environmental media such as soil, groundwater, sediment, or surface water. Remedial action is generally subject to an array of regulatory requirements, and may also ...

. Radioactive materials are known to be leaking from Hanford into the environment. The Radiation Exposure Compensation Act

The United States Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA) is a federal statute providing for the monetary compensation of people, including atomic veterans, who contracted cancer and a number of other specified diseases as a direct result of t ...

of 1990 allows for U.S. citizens exposed to radiation or other health risks through the U.S. nuclear program to file for compensation and damages.

Deliberate attacks on weapons facilities

In 1972, three hijackers took control of a domestic passenger flight along the east coast of the U.S. and threatened to crash the plane into a U.S.nuclear weapons