Northern Ireland independence on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Ulster nationalism is a minor school of thought in the politics of Northern Ireland that seeks the independence of Northern Ireland from the United Kingdom without joining the Republic of Ireland, thereby becoming an independent sovereign state separate from both.

Independence has been supported by groups such as Ulster Third Way and some factions of the Ulster Defence Association. However, it is a fringe view in Northern Ireland. It is neither supported by any of the political parties represented in the

Ulster nationalism is a minor school of thought in the politics of Northern Ireland that seeks the independence of Northern Ireland from the United Kingdom without joining the Republic of Ireland, thereby becoming an independent sovereign state separate from both.

Independence has been supported by groups such as Ulster Third Way and some factions of the Ulster Defence Association. However, it is a fringe view in Northern Ireland. It is neither supported by any of the political parties represented in the

Ulster nationalism represents a reaction from within unionism to the perceived uncertainty of the future of the Union by the

Ulster nationalism represents a reaction from within unionism to the perceived uncertainty of the future of the Union by the

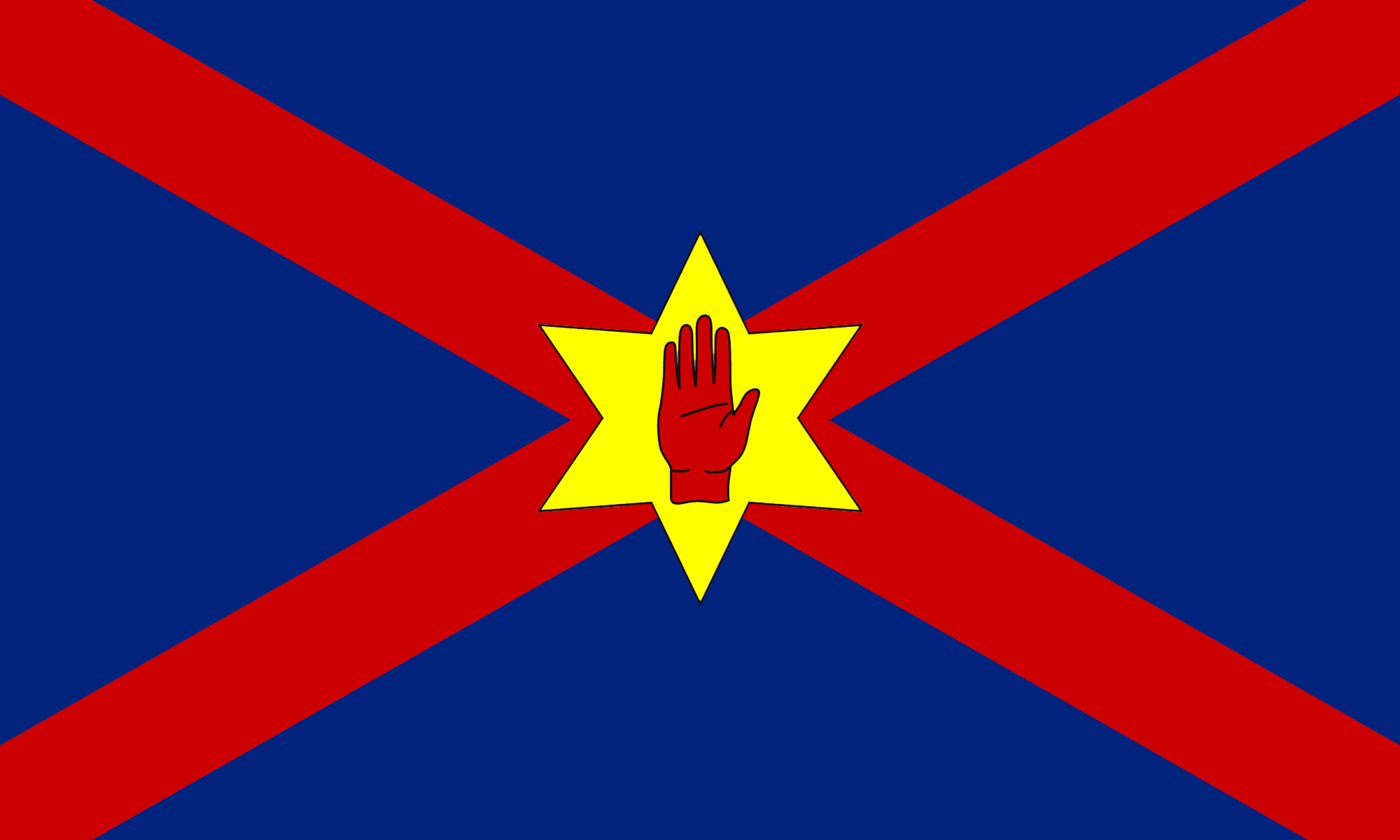

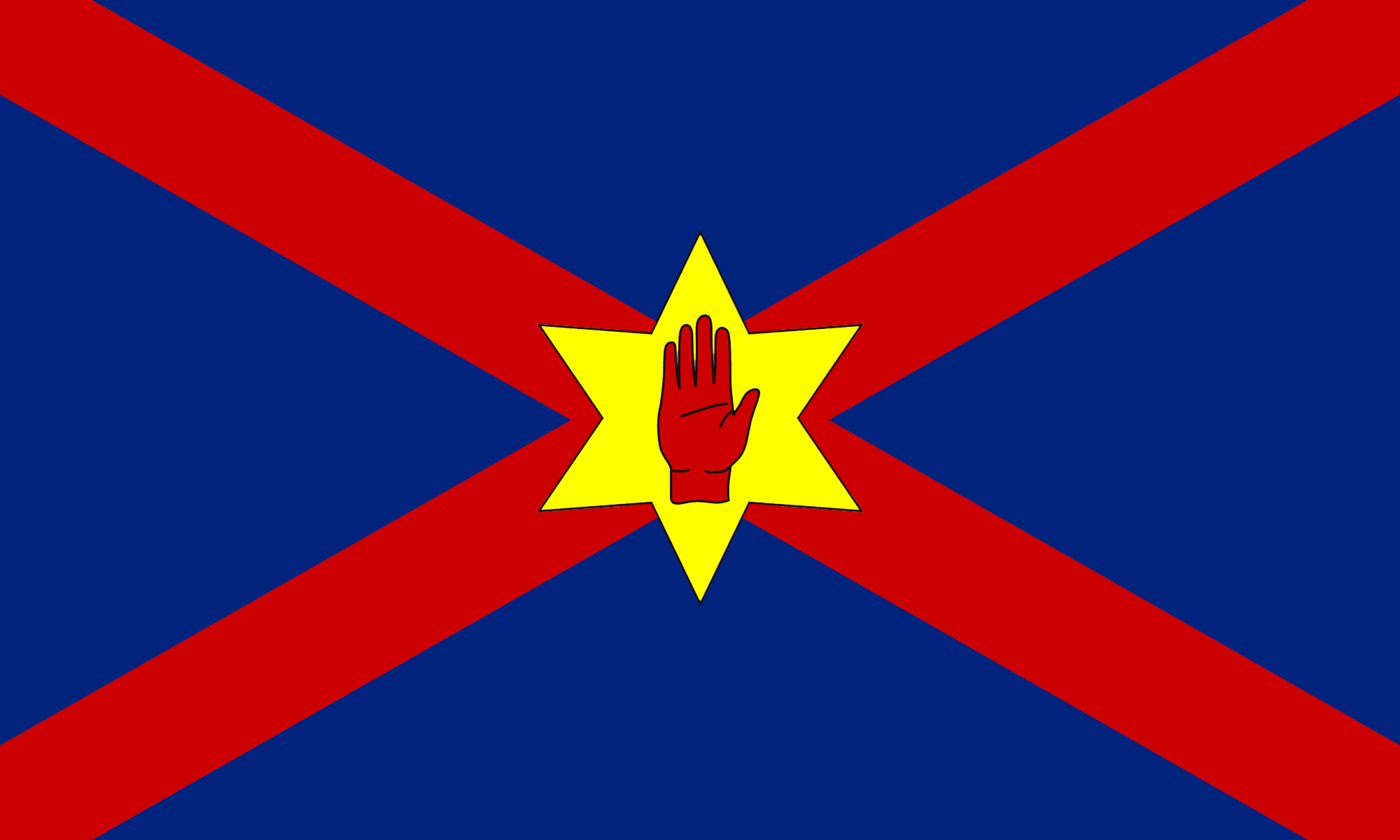

Ulster Nation

{{Ulster Defence Association Separatism in the United Kingdom Independence movements Politics of Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland Assembly

sco-ulster, Norlin Airlan Assemblie

, legislature = 7th Northern Ireland Assembly, Seventh Assembly

, coa_pic = File:NI_Assembly.svg

, coa_res = 250px

, house_type = Unicameralism, Unicameral

, hou ...

nor by the government of the United Kingdom or the government of the Republic of Ireland.

Although the term Ulster traditionally refers to one of the four traditional provinces of Ireland

There have been four Provinces of Ireland: Connacht (Connaught), Leinster, Munster, and Ulster. The Irish language, Irish word for this territorial division, , meaning "fifth part", suggests that there were once five, and at times Kingdom_of_ ...

which contains Northern Ireland as well as parts of the Republic of Ireland, the term is often used within unionism

Unionism may refer to:

Trades

*Community unionism, the ways trade unions work with community organizations

*Craft unionism, a model of trade unionism in which workers are organised based on a particular craft or trade

* Dual unionism, the develop ...

and Ulster loyalism (from which Ulster nationalism originated) to refer to Northern Ireland.

History

Craig in 1921

In November 1921, during negotiations for the Anglo-Irish Treaty, there was correspondence between David Lloyd George andSir James Craig

James Craig, 1st Viscount Craigavon PC PC (NI) DL (8 January 1871 – 24 November 1940), was a leading Irish unionist and a key architect of Northern Ireland as a devolved region within the United Kingdom. During the Home Rule Crisis of 1912 ...

, respective prime ministers of the UK and Northern Ireland. Lloyd George envisaged a choice for Northern Ireland between, on the one hand, remaining part of the UK under the Government of Ireland Act 1920, while what had been Southern Ireland

Southern Ireland, South Ireland or South of Ireland may refer to:

*The southern part of the island of Ireland

*Southern Ireland (1921–1922), a former constituent part of the United Kingdom

*Republic of Ireland, which is sometimes referred to as ...

became a Dominion; and, on the other hand, becoming part of an all-Ireland Dominion where the Stormont parliament

The Parliament of Northern Ireland was the home rule legislature of Northern Ireland, created under the Government of Ireland Act 1920, which sat from 7 June 1921 to 30 March 1972, when it was suspended because of its inability to restore ord ...

was subordinate to a parliament in Dublin instead of Westminster. Craig responded that a third option would be for Northern Ireland to be a Dominion in parallel with Southern Ireland and the "Overseas Dominions", saying "while Northern Ireland would deplore any loosening of the tie between Great Britain and herself she would regard the loss of representation at Westminster as a less evil than inclusion in an all-Ireland Parliament".

W. F. McCoy and Dominion status

Ulster nationalism has its origins in 1946 whenW. F. McCoy

William Frederick McCoy (19 January 1885 – 4 December 1976) was an Ulster Unionist Party, Ulster Unionist member of the Parliament of Northern Ireland for South Tyrone (Northern Ireland Parliament constituency), South Tyrone who went on to ...

, a former cabinet minister in the government of Northern Ireland, advocated this option. He wanted Northern Ireland to become a dominion with a political system similar to Canada, New Zealand, Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a Sovereign state, sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous List of islands of Australia, sma ...

and the then Union of South Africa, or the Irish Free State prior to 1937. McCoy, a lifelong member of the Ulster Unionist Party, felt that the uncertain constitutional status of Northern Ireland made the Union vulnerable and so saw his own form of limited Ulster nationalism as a way to safeguard Northern Ireland's relationship with the United Kingdom.

Some members of the Ulster Vanguard

The Vanguard Unionist Progressive Party (VUPP), informally known as Ulster Vanguard, was a unionist political party which existed in Northern Ireland between 1972 and 1978. Led by William Craig, the party emerged from a split in the Ulster Unio ...

movement, led by Bill Craig, in the early 1970s published similar arguments, most notably Professor Kennedy Lindsay. In the early 1970s, in the face of the British government prorogation of the government of Northern Ireland, Craig, Lindsay and others argued in favour of a unilateral declaration of independence (UDI) from Great Britain similar to that declared in Rhodesia

Rhodesia (, ), officially from 1970 the Republic of Rhodesia, was an unrecognised state in Southern Africa from 1965 to 1979, equivalent in territory to modern Zimbabwe. Rhodesia was the ''de facto'' successor state to the British colony of S ...

a few years previously. Lindsay later founded the British Ulster Dominion Party

The British Ulster Dominion Party was a minor political party in Northern Ireland during the 1970s.

The party began in 1975 as the Ulster Dominion Group, when Professor Kennedy Lindsay broke from the United Ulster Unionist movement (which would la ...

to this end but it faded into obscurity around 1979.

Loyalism and Ulster nationalism

Whilst early versions of Ulster nationalism had been designed to safeguard the status of Northern Ireland, the movement saw something of a rebirth in the 1970s, particularly following the 1972 suspension of the Parliament of Northern Ireland and the resulting political uncertainty in the region.Glenn Barr

Albert Glenn Barr OBE (19 March 1942 – 24 October 2017) was a politician from Derry, Northern Ireland, who was an advocate of Ulster nationalism. For a time during the 1970s he straddled both Unionism and Loyalism due to simultaneously holdi ...

, a Vanguard Unionist Progressive Party Assemblyman and Ulster Defence Association leader, described himself in 1973 as "an Ulster nationalist". The successful Ulster Workers Council Strike

The Ulster Workers' Council (UWC) strike was a general strike that took place in Northern Ireland between 15 May and 28 May 1974, during "the Troubles". The strike was called by unionists who were against the Sunningdale Agreement, which had b ...

in 1974 (which was directed by Barr) was later described by the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland

A secretary, administrative professional, administrative assistant, executive assistant, administrative officer, administrative support specialist, clerk, military assistant, management assistant, office secretary, or personal assistant is a w ...

Merlyn Rees as an "outbreak of Ulster nationalism". Labour Prime Minister Jim Callaghan also thought an independent Northern Ireland might be viable.

After the strike loyalism began to embrace Ulster nationalist ideas, with the UDA, in particular, advocating this position. Firm proposals for an independent Ulster were produced in 1976 by the Ulster Loyalist Central Co-ordinating Committee and in 1977 by the UDA's New Ulster Political Research Group. The NUPRG document, ''Beyond the Religious Divide'', has been recently republished with a new introduction. John McMichael

John McMichael (9 January 1948 – 22 December 1987) was a Northern Irish loyalist who rose to become the most prominent and charismatic figure within the Ulster Defence Association (UDA) as the Deputy Commander and leader of its South Belf ...

, as candidate for the UDA-linked Ulster Loyalist Democratic Party

Ulster (; ga, Ulaidh or ''Cúige Uladh'' ; sco, label=Ulster Scots dialects, Ulster Scots, Ulstèr or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional provinces of Ireland, Irish provinces. It is made up of nine Counties of Ireland, counties: si ...

, campaigned for the 1982 South Belfast by-election on the basis of negotiations towards independence. However, McMichael's poor showing of 576 votes saw the plans largely abandoned by the UDA soon after, although the policy was still considered by the Ulster Democratic Party under Ray Smallwoods

Raymond "Ray" Smallwoods (c. 1949 – 11 July 1994) was a Northern Ireland politician and sometime leader of the Ulster Democratic Party. A leading member of John McMichael's South Belfast Brigade of the Ulster Defence Association (UDA), Smallwo ...

. A short-lived Ulster Independence Party

The Ulster Independence Party was an Ulster nationalist political party.

The group was founded in October 1977 by the supporters of a document issued the previous year, ''Towards an Independent Ulster''. The group initially claimed the support ...

also operated, although the assassination of its leader, John McKeague, in 1982 saw it largely disappear.

Post-Anglo-Irish Agreement

The idea enjoyed something of a renaissance in the aftermath of the Anglo-Irish Agreement, with theUlster Clubs

The Ulster Clubs was the name given to a network of Unionist organisations founded in Northern Ireland in November 1985. Emerging from an earlier group based in Portadown, the Ulster Clubs briefly mobilised wide support across Northern Ireland an ...

amongst those to consider the notion. After a series of public meetings, leading Ulster Clubs member, Reverend Hugh Ross, set up the Ulster Independence Committee in 1988, which soon re-emerged as the Ulster Independence Movement advocating full independence of Northern Ireland from Britain. After a reasonable showing in the 1990 Upper Bann by-election

The 1990 by-election in Upper Bann was caused by the death of the sitting Ulster Unionist Party Member of Parliament Harold McCusker on 2 February 1990.

The by-election was especially notable for three reasons. Firstly, the Sinn Féin candidate ...

, the group stepped up its campaigning in the aftermath of the Downing Street Declaration and enjoyed a period of increased support immediately after the Good Friday Agreement (also absorbing the Ulster Movement for Self-Determination, which desired all of Ulster as the basis for independence, along the way). No tangible electoral success was gained however, and the group was further damaged by allegations against Ross in a Channel 4 documentary on collusion, ''The Committee'', leading to the group reconstituting as a ginger group

The Ginger Group was not a formal political party in Canada, but a faction of radical Progressive and Labour Members of Parliament who advocated socialism. The term ginger group also refers to a small group with new, radical ideas trying to act ...

in 2000.

With the UIM defunct, Ulster nationalism was then represented by the Ulster Third Way, which was involved in the publication of the ''Ulster Nation'', a journal of radical Ulster nationalism. Ulster Third Way, which registered as a political party in February 2001, was the Northern Ireland branch of the UK-wide Third Way, albeit with much stronger emphasis on the Northern Ireland question. Ulster Third Way contested the West Belfast parliamentary seat in the 2001 general election, although candidate and party leader David Kerr failed to attract much support.

Northern Irish independence is still seen by some members of society as a way of moving forward in terms of the political crisis that continues to haunt Northern Irish politics even today. Some economists and politicians see an independent state as viable but others believe that Northern Ireland would not survive unless it had the support of the United Kingdom or the Republic of Ireland. Although it is not supported by a political party, around 533,085 declared in the 2011 census to be Northern Irish. This identity does not mean they believe in independence, however in a poll based upon what the future policy for Northern Ireland should be, 15% of the poll voters were in favour of Northern Irish independence.

Relationship to unionism

Ulster nationalism represents a reaction from within unionism to the perceived uncertainty of the future of the Union by the

Ulster nationalism represents a reaction from within unionism to the perceived uncertainty of the future of the Union by the British government

ga, Rialtas a Shoilse gd, Riaghaltas a Mhòrachd

, image = HM Government logo.svg

, image_size = 220px

, image2 = Royal Coat of Arms of the United Kingdom (HM Government).svg

, image_size2 = 180px

, caption = Royal Arms

, date_es ...

. Its leadership and members have all been unionists and have tended to react to what they viewed as crises surrounding the status of Northern Ireland as a part of the United Kingdom, such as the moves towards power-sharing in the 1970s or the Belfast Agreement of 1998, which briefly saw the UIM become a minor force. In such instances it has been considered preferable by the supporters of this ideological movement to remove the British dimension either partially (Commonwealth realm

A Commonwealth realm is a sovereign state in the Commonwealth of Nations whose monarch and head of state is shared among the other realms. Each realm functions as an independent state, equal with the other realms and nations of the Commonwealt ...

status) or fully (independence) to avoid a united Ireland.

However, whilst support for Ulster nationalism has tended to be reactive to political change, the theory also underlines the importance of Ulster cultural nationalism and the separate identity and culture of Ulster. As such, Ulster nationalist movements have been at the forefront of supporting the Orange Order

The Loyal Orange Institution, commonly known as the Orange Order, is an international Protestant fraternal order based in Northern Ireland and primarily associated with Ulster Protestants, particularly those of Ulster Scots heritage. It also ...

and supporting contested 12 July marches as important parts of this cultural heritage, as well as encouraging the retention of the Ulster Scots dialects.

Outside traditional Protestant-focused Ulster nationalism, a non-sectarian independent Northern Ireland has sometimes been advocated as a solution to the conflict. Two notable examples of this are the Scottish Marxist

Marxism is a Left-wing politics, left-wing to Far-left politics, far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a Materialism, materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand S ...

Tom Nairn and the Irish nationalist Liam de Paor

Liam is a short form of the Irish name Uilliam or the old Germanic name William.

Etymology

The original name was a merging of two Old German elements: ''willa'' ("will" or "resolution"); and ''helma'' ("helmet"). The juxtaposition of these ele ...

.

See also

*Cornish nationalism

Cornish nationalism is a cultural, political and social movement that seeks the recognition of Cornwall – the south-westernmost part of the island of Great Britain – as a nation distinct from England. It is usually based on three general ...

*English independence

English independence is a political stance advocating secession of England from the United Kingdom. Support for secession of England (the UK's largest and most populated country) has been influenced by the increasing devolution of political pow ...

*Scottish independence

Scottish independence ( gd, Neo-eisimeileachd na h-Alba; sco, Scots unthirldom) is the idea of Scotland as a sovereign state, independent from the United Kingdom, and refers to the political movement that is campaigning to bring it about.

S ...

* Two nations theory (Ireland)

* Unionism in Ireland

* Welsh independence

References

Sources

*Citations

External links

*Ulster Nation

{{Ulster Defence Association Separatism in the United Kingdom Independence movements Politics of Northern Ireland